Electronic music is a

genre

Genre () is any form or type of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially-agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other for ...

of music that employs

electronic musical instruments, digital instruments, or

circuitry-based music technology

Music technology is the study or the use of any device, mechanism, machine or tool by a musician or composer to make or perform music; to compose, notate, playback or record songs or pieces; or to analyze or edit music.

History

The earli ...

in its creation. It includes both music made using electronic and electromechanical means (

electroacoustic music). Pure electronic instruments depended entirely on circuitry-based sound generation, for instance using devices such as an

electronic oscillator,

theremin

The theremin (; originally known as the ætherphone/etherphone, thereminophone or termenvox/thereminvox) is an electronic musical instrument controlled without physical contact by the performer (who is known as a thereminist). It is named afte ...

, or synthesizer. Electromechanical instruments can have mechanical parts such as strings, hammers, and electric elements including

magnetic pickups,

power amplifiers and

loudspeaker

A loudspeaker (commonly referred to as a speaker or speaker driver) is an electroacoustic transducer that converts an electrical audio signal into a corresponding sound. A ''speaker system'', also often simply referred to as a "speaker" or ...

s. Such electromechanical devices include the

telharmonium

The Telharmonium (also known as the Dynamophone) was an early electrical organ, developed by Thaddeus Cahill c. 1896 and patented in 1897.

, filed 1896-02-04.

The electrical signal from the Telharmonium was transmitted over wires; it was hear ...

,

Hammond organ,

electric piano and the electric guitar.

["The stuff of electronic music is electrically produced or modified sounds. ... two basic definitions will help put some of the historical discussion in its place: purely electronic music versus electroacoustic music" ()][Electroacoustic music may also use electronic ]effect unit

An effects unit or effects pedal is an electronic device that alters the sound of a musical instrument or other audio source through audio signal processing.

Common effects include distortion/overdrive, often used with electric guitar in ele ...

s to change sounds from the natural world, such as the sound of waves on a beach or bird calls. All types of sounds can be used as source material for this music. Electroacoustic performers and composers use microphones, tape recorders, and digital samplers to make live or recorded music. During live performances, natural sounds are modified in real-time using electronic effects and audio console

A mixing console or mixing desk is an electronic device for mixing audio signals, used in sound recording and reproduction and sound reinforcement systems. Inputs to the console include microphones, signals from electric or electronic instr ...

s. The source of the sound can be anything from ambient noise (traffic, people talking) and nature sounds to live musicians playing conventional acoustic or electro-acoustic instruments ()

The first electronic musical devices were developed at the end of the 19th century. During the 1920s and 1930s, some electronic instruments were introduced and the first compositions featuring them were written. By the 1940s, magnetic audio tape allowed musicians to tape sounds and then modify them by changing the tape speed or direction, leading to the development of

electroacoustic tape music

Jack Dangers (born John Stephen Corrigan, 11 January 1965) is an English electronic musician, DJ, producer, and remixer best known for his work as the primary member of Meat Beat Manifesto. He lives in San Francisco.

Career

Prior to founding ...

in the 1940s, in Egypt and France.

Musique concrète, created in Paris in 1948, was based on editing together recorded fragments of natural and industrial sounds. Music produced solely from electronic generators was first produced in Germany in 1953. Electronic music was also created in Japan and the United States beginning in the 1950s and

Algorithmic composition

Algorithmic composition is the technique of using algorithms to create music.

Algorithms (or, at the very least, formal sets of rules) have been used to compose music for centuries; the procedures used to plot voice-leading in Western counterpo ...

with computers was first demonstrated in the same decade.

During the 1960s, digital

computer music

Computer music is the application of computing technology in music composition, to help human composers create new music or to have computers independently create music, such as with algorithmic composition programs. It includes the theory and ...

was pioneered, innovation in

live electronics

Live electronic music (also known as live electronics) is a form of music that can include traditional electronic sound-generating devices, modified electric musical instruments, hacked sound generating technologies, and computers. Initially the pr ...

took place, and Japanese electronic musical instruments began to influence the

music industry. In the early 1970s,

Moog synthesizers and Japanese

drum machines helped popularize synthesized electronic music. The 1970s also saw electronic music begin to have a significant influence on

popular music

Popular music is music with wide appeal that is typically distributed to large audiences through the music industry. These forms and styles can be enjoyed and performed by people with little or no musical training.Popular Music. (2015). ''Fu ...

, with the adoption of

polyphonic synthesizer

Polyphony is a property of musical instruments that means that they can play multiple independent melody lines simultaneously. Instruments featuring polyphony are said to be polyphonic. Instruments that are not capable of polyphony are monophoni ...

s,

electronic drums, drum machines, and

turntables

A phonograph, in its later forms also called a gramophone (as a trademark since 1887, as a generic name in the UK since 1910) or since the 1940s called a record player, or more recently a turntable, is a device for the mechanical and analogu ...

, through the emergence of genres such as

disco,

krautrock,

new wave,

synth-pop,

hip hop, and

EDM

EDM or E-DM may refer to:

Music

* Electronic dance music

* Early Day Miners, American band

Science and technology

* Electric dipole moment

* Electrical discharge machining

* Electronic distance measurement

*Entry, Descent, and landing demonstrat ...

. In the early 1980s mass-produced

digital synthesizers, such as the

Yamaha DX7

The Yamaha DX7 is a synthesizer manufactured by the Yamaha Corporation from 1983 to 1989. It was the first successful digital synthesizer and is one of the best-selling synthesizers in history, selling more than 200,000 units.

In the early 1980 ...

, became popular, and

MIDI

MIDI (; Musical Instrument Digital Interface) is a technical standard that describes a communications protocol, digital interface, and electrical connectors that connect a wide variety of electronic musical instruments, computers, and ...

(Musical Instrument Digital Interface) was developed. In the same decade, with a greater reliance on synthesizers and the adoption of programmable drum machines, electronic popular music came to the fore. During the 1990s, with the proliferation of increasingly affordable music technology, electronic music production became an established part of popular culture. In Berlin starting in 1989, the

Love Parade

The Love Parade (german: Loveparade) was a popular electronic dance music festival and technoparade that originated in 1989 in West Berlin, Germany. It was held annually in Berlin from 1989 to 2003 and in 2006, then from 2007 to 2010 in the Ruh ...

became the largest street party with over 1 million visitors, inspiring other such popular celebrations of electronic music.

Contemporary electronic music includes many varieties and ranges from

experimental art music to popular forms such as

electronic dance music. Pop electronic music is most recognizable in its 4/4 form and more connected with the mainstream than preceding forms which were popular in niche markets.

Origins: late 19th century to early 20th century

At the turn of the 20th century, experimentation with

emerging electronics led to the first

electronic musical instruments.

These initial inventions were not sold, but were instead used in demonstrations and public performances. The audiences were presented with reproductions of existing music instead of new compositions for the instruments. While some were considered novelties and produced simple tones, the

Telharmonium

The Telharmonium (also known as the Dynamophone) was an early electrical organ, developed by Thaddeus Cahill c. 1896 and patented in 1897.

, filed 1896-02-04.

The electrical signal from the Telharmonium was transmitted over wires; it was hear ...

synthesized the sound of several orchestral instruments with reasonable precision. It achieved viable public interest and made commercial progress into

streaming music through

telephone network

A telephone network is a telecommunications network that connects telephones, which allows telephone calls between two or more parties, as well as newer features such as fax and internet. The idea was revolutionized in the 1920s, as more and mor ...

s.

Critics of musical conventions at the time saw promise in these developments.

Ferruccio Busoni encouraged the composition of

microtonal music

Microtonal music or microtonality is the use in music of microtones— intervals smaller than a semitone, also called "microintervals". It may also be extended to include any music using intervals not found in the customary Western tuning of ...

allowed for by electronic instruments. He predicted the use of machines in future music, writing the influential ''Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music'' (1907).

Futurists

Futurists (also known as futurologists, prospectivists, foresight practitioners and horizon scanners) are people whose specialty or interest is futurology or the attempt to systematically explore predictions and possibilities abou ...

such as

Francesco Balilla Pratella

Francesco Balilla Pratella (Lugo, Italy February 1, 1880 – Ravenna, Italy May 17, 1955) was an Italian composer, musicologist and essayist. One of the leading advocates of Futurism in Italian music, much of Pratella's own music betrays little o ...

and

Luigi Russolo

Luigi Carlo Filippo Russolo (30 April 1885 – 4 February 1947) was an Italian Futurist painter, composer, builder of experimental musical instruments, and the author of the manifesto ''The Art of Noises'' (1913). He is often regarded as one of ...

began composing

music with acoustic noise to evoke the sound of

machinery. They predicted expansions in

timbre

In music, timbre ( ), also known as tone color or tone quality (from psychoacoustics), is the perceived sound quality of a musical note, sound or tone. Timbre distinguishes different types of sound production, such as choir voices and musica ...

allowed for by electronics in the influential manifesto ''

The Art of Noises

''The Art of Noises'' ( it, L'arte dei Rumori) is a Futurist manifesto written by Luigi Russolo in a 1913 letter to friend and Futurist composer Francesco Balilla Pratella. In it, Russolo argues that the human ear has become accustomed to the ...

'' (1913).

[.]

Early compositions

Developments of the

vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve (British usage), or tube (North America), is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric potential difference has been applied.

The type known as ...

led to electronic instruments that were smaller,

amplified, and more practical for performance.

In particular, the

theremin

The theremin (; originally known as the ætherphone/etherphone, thereminophone or termenvox/thereminvox) is an electronic musical instrument controlled without physical contact by the performer (who is known as a thereminist). It is named afte ...

,

ondes Martenot

The ondes Martenot ( ; , "Martenot waves") or ondes musicales ("musical waves") is an early electronic musical instrument. It is played with a keyboard or by moving a ring along a wire, creating "wavering" sounds similar to a theremin. A player ...

and

trautonium

The Trautonium is an electronic synthesizer invented in 1930 by Friedrich Trautwein in Berlin at the Musikhochschule's music and radio lab, the Rundfunkversuchstelle. Soon afterwards Oskar Sala joined him, continuing development until Sala's de ...

were commercially produced by the early 1930s.

[; ]

From the late 1920s, the increased practicality of electronic instruments influenced composers such as

Joseph Schillinger

Joseph Moiseyevich Schillinger ( Russian: Иосиф Моисеевич Шиллингер, (other sources: ) – 23 March 1943) was a composer, music theorist, and composition teacher who originated the Schillinger System of Musical Compositio ...

to adopt them. They were typically used within orchestras, and most composers wrote parts for the theremin that could otherwise be performed with

string instruments.

Avant-garde composers

Avant-garde music is music that is considered to be at the forefront of innovation in its field, with the term "avant-garde" implying a critique of existing aesthetic conventions, rejection of the status quo in favor of unique or original eleme ...

criticized the predominant use of electronic instruments for conventional purposes.

The instruments offered expansions in pitch resources

that were exploited by advocates of microtonal music such as

Charles Ives,

Dimitrios Levidis Dimitrios Levidis ( el, Δημήτριος Λεβίδης; 8 April 1885 or 1886, Athens - 29 May 1951, Palaio Faliro) was a Greek composer, later naturalized French (1929).

Background

He descended from an aristocratic family with Byzantine root ...

,

Olivier Messiaen and

Edgard Varèse.

Further,

Percy Grainger

Percy Aldridge Grainger (born George Percy Grainger; 8 July 188220 February 1961) was an Australian-born composer, arranger and pianist who lived in the United States from 1914 and became an American citizen in 1918. In the course of a long an ...

used the theremin to abandon fixed tonation entirely,

while Russian composers such as

Gavriil Popov treated it as a source of noise in otherwise-acoustic

noise music.

Recording experiments

Developments in early

recording technology paralleled that of electronic instruments. The first means of recording and reproducing audio was invented in the late 19th century with the mechanical

phonograph.

Record players became a common household item, and by the 1920s composers were using them to play short recordings in performances.

The introduction of

electrical recording

A phonograph record (also known as a gramophone record, especially in British English), or simply a record, is an analog sound storage medium in the form of a flat disc with an inscribed, modulated spiral groove. The groove usually starts near ...

in 1925 was followed by increased experimentation with record players.

Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith (; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major advocate of the ' ...

and

Ernst Toch

Ernst Toch (; 7 December 1887 – 1 October 1964) was an Austrian composer of classical music and film scores. He sought throughout his life to introduce new approaches to music.

Biography

Toch was born in Leopoldstadt, Vienna, into the family ...

composed several pieces in 1930 by layering recordings of instruments and vocals at adjusted speeds. Influenced by these techniques,

John Cage composed ''

Imaginary Landscape No. 1'' in 1939 by adjusting the speeds of recorded tones.

Composers began to experiment with newly developed

sound-on-film

Sound-on-film is a class of sound film processes where the sound accompanying a picture is recorded on photographic film, usually, but not always, the same strip of film carrying the picture. Sound-on-film processes can either record an analog ...

technology. Recordings could be spliced together to create

sound collage

In music, montage (literally "putting together") or sound collage ("gluing together") is a technique where newly branded sound objects or compositions, including songs, are created from collage, also known as montage. This is often done throu ...

s, such as those by

Tristan Tzara

Tristan Tzara (; ; born Samuel or Samy Rosenstock, also known as S. Samyro; – 25 December 1963) was a Romanian and French avant-garde poet, essayist and performance artist. Also active as a journalist, playwright, literary and art critic, comp ...

,

Kurt Schwitters

Kurt Hermann Eduard Karl Julius Schwitters (20 June 1887 – 8 January 1948) was a German artist who was born in Hanover, Germany.

Schwitters worked in several genres and media, including dadaism, Constructivism (art), constructivism, surrealism ...

,

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

Filippo Tommaso Emilio Marinetti (; 22 December 1876 – 2 December 1944) was an Italian poet, editor, art theorist, and founder of the Futurist movement. He was associated with the utopian and Symbolist artistic and literary community Abbaye d ...

,

Walter Ruttmann

Walter Ruttmann (28 December 1887 – 15 July 1941) was a German cinematographer and film director, an important German abstract experimental film maker, along with Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling and Oskar Fischinger. He is best known for dire ...

and

Dziga Vertov

Dziga Vertov (russian: Дзига Вертов, born David Abelevich Kaufman, russian: Дави́д А́белевич Ка́уфман, and also known as Denis Kaufman; – 12 February 1954) was a Soviet pioneer documentary film and newsre ...

. Further, the technology allowed sound to be

graphically created and modified. These techniques were used to compose soundtracks for several films in Germany and Russia, in addition to the popular ''

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' in the United States. Experiments with graphical sound were continued by

Norman McLaren from the late 1930s.

Development: 1940s to 1950s

Electroacoustic tape music

The first practical audio

tape recorder

An audio tape recorder, also known as a tape deck, tape player or tape machine or simply a tape recorder, is a sound recording and reproduction device that records and plays back sounds usually using magnetic tape for storage. In its present ...

was unveiled in 1935. Improvements to the technology were made using the

AC bias

Tape bias is the term for two techniques, AC bias and DC bias, that improve the fidelity of analogue tape recorders. DC bias is the addition of direct current to the audio signal that is being recorded. AC bias is the addition of an inaud ...

ing technique, which significantly improved recording fidelity.

As early as 1942, test recordings were being made in stereo. Although these developments were initially confined to Germany, recorders and tapes were brought to the United States following the end of World War II. These were the basis for the first commercially produced tape recorder in 1948.

In 1944, before the use of magnetic tape for compositional purposes, Egyptian composer

Halim El-Dabh

Halim Abdul Messieh El-Dabh ( ar, حليم عبد المسيح الضبع, ''Ḥalīm ʻAbd al-Masīḥ al-Ḍab''ʻ; March 4, 1921 – September 2, 2017) was an Egyptian-American composer, musician, ethnomusicologist, and educator, who had ...

, while still a student in

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

, used a cumbersome

wire recorder

Wire recording or magnetic wire recording was the first magnetic recording technology, an analog type of audio storage in which a magnetic recording is made on a thin steel wire. The first crude magnetic recorder was invented in 1898 by Valde ...

to record sounds of an ancient ''

zaar'' ceremony. Using facilities at the Middle East Radio studios El-Dabh processed the recorded material using reverberation, echo, voltage controls and re-recording. What resulted is believed to be the earliest tape music composition.

The resulting work was entitled ''The Expression of Zaar'' and it was presented in 1944 at an art gallery event in Cairo. While his initial experiments in tape-based composition were not widely known outside of Egypt at the time, El-Dabh is also known for his later work in electronic music at the

Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center

The Computer Music Center (CMC) at Columbia University is the oldest center for electronic and computer music research in the United States. It was founded in the 1950s as the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center.

Location

The CMC is hou ...

in the late 1950s.

Musique concrète

Following his work with

Studio d'Essai at

Radiodiffusion Française

Radiodiffusion Française (RDF) was a French public institution responsible for public service broadcasting.

Created in 1944 as a state monopoly (replacing Radiodiffusion Nationale), RDF worked to rebuild its extensive network, destroyed during t ...

(RDF), during the early 1940s,

Pierre Schaeffer

Pierre Henri Marie Schaeffer (English pronunciation: , ; 14 August 1910 – 19 August 1995) was a French composer, writer, broadcaster, engineer, musicologist, acoustician and founder of Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète (GRMC). His inno ...

is credited with originating the theory and practice of musique concrète. In the late 1940s, experiments in sound-based composition using

shellac

Shellac () is a resin secreted by the female lac bug on trees in the forests of India and Thailand. It is processed and sold as dry flakes and dissolved in alcohol to make liquid shellac, which is used as a brush-on colorant, food glaze and ...

record players were first conducted by Schaeffer. In 1950, the techniques of musique concrete were expanded when magnetic tape machines were used to explore sound manipulation practices such as speed variation (

pitch shift

Pitch shifting is a sound recording technique in which the original pitch of a sound is raised or lowered. Effects units that raise or lower pitch by a pre-designated musical interval ( transposition) are called pitch shifters.

Pitch and tim ...

) and

tape splicing.

On 5 October 1948, RDF broadcast Schaeffer's ''Etude aux chemins de fer''. This was the first "

movement" of ''Cinq études de bruits'', and marked the beginning of studio realizations and musique concrète (or acousmatic art). Schaeffer employed a

disc cutting lathe

upPresto 8N Disc Cutting Lathe (1950) used by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation to record radio programs

A disc cutting lathe is a device used to transfer an audio signal to the modulated spiral groove of a blank master disc for the productio ...

, four turntables, a four-channel mixer, filters, an echo chamber, and a mobile recording unit. Not long after this,

Pierre Henry began collaborating with Schaeffer, a partnership that would have profound and lasting effects on the direction of electronic music. Another associate of Schaeffer,

Edgard Varèse, began work on ''

Déserts

''Déserts'' (1950–1954) is a piece by Edgard Varèse for 14 winds (brass and woodwinds), 5 percussion players, 1 piano, and electronic tape."Blue" Gene Tyranny (2010). " Déserts for brass, percussion, piano & tape, ''AllMusic.com''. The piece ...

'', a work for chamber orchestra and tape. The tape parts were created at Pierre Schaeffer's studio and were later revised at Columbia University.

In 1950, Schaeffer gave the first public (non-broadcast) concert of musique concrète at the

École Normale de Musique de Paris

The École Normale de Musique de Paris "Alfred Cortot" (ENMP) is a leading conservatoire located in Paris, Île-de-France, France. At the time of the school's foundation in 1919 by Auguste Mangeot, Alfred Cortot. The term ''école normale'' (Eng ...

. "Schaeffer used a

PA system

A public address system (or PA system) is an electronic system comprising microphones, amplifiers, loudspeakers, and related equipment. It increases the apparent volume (loudness) of a human voice, musical instrument, or other acoustic sound sou ...

, several turntables, and mixers. The performance did not go well, as creating live montages with turntables had never been done before." Later that same year, Pierre Henry collaborated with Schaeffer on ''Symphonie pour un homme seul'' (1950) the first major work of musique concrete. In Paris in 1951, in what was to become an important worldwide trend, RTF established the first studio for the production of electronic music. Also in 1951, Schaeffer and Henry produced an opera, ''Orpheus'', for concrete sounds and voices.

By 1951 the work of Schaeffer, composer-percussionist Pierre Henry, and sound engineer Jacques Poullin had received official recognition and

The Groupe de Recherches de Musique Concrète, Club d 'Essai de la

Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française

Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (RTF; ''French Radio and Television Broadcasting'') was the French national public broadcaster television organization established on 9 February 1949 to replace the post-war "''Radiodiffusion Française''" ...

was established at RTF in Paris, the ancestor of the

ORTF.

Elektronische Musik

Karlheinz Stockhausen

Karlheinz Stockhausen (; 22 August 1928 – 5 December 2007) was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important but also controversial composers of the 20th-century classical music, 20th and early 21st-century ...

worked briefly in Schaeffer's studio in 1952, and afterward for many years at the

WDR Cologne's

Studio for Electronic Music.

1954 saw the advent of what would now be considered authentic electric plus acoustic compositions—acoustic instrumentation augmented/accompanied by recordings of manipulated or electronically generated sound. Three major works were premiered that year: Varèse's ''Déserts'', for chamber ensemble and tape sounds, and two works by

Otto Luening

Otto Clarence Luening (June 15, 1900 – September 2, 1996) was a German-American composer and conductor, and an early pioneer of tape music and electronic music.

Luening was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin to German parents, Eugene, a conduct ...

and

Vladimir Ussachevsky

Vladimir Alexeevich Ussachevsky (November 3, 1911 in Hailar, China – January 2, 1990 in New York, New York) was a composer, particularly known for his work in electronic music.

Biography

Vladimir Ussachevsky was born in the Hailar District ...

: ''Rhapsodic Variations for the Louisville Symphony'' and ''A Poem in Cycles and Bells'', both for orchestra and tape. Because he had been working at Schaeffer's studio, the tape part for Varèse's work contains much more concrete sounds than electronic. "A group made up of wind instruments, percussion and piano alternate with the mutated sounds of factory noises and ship sirens and motors, coming from two loudspeakers."

[.]

At the German premiere of ''Déserts'' in Hamburg, which was conducted by

Bruno Maderna

Bruno Maderna (21 April 1920 – 13 November 1973) was an Italian conductor and composer.

Life

Maderna was born Bruno Grossato in Venice but later decided to take the name of his mother, Caterina Carolina Maderna.Interview with Maderna‘s th ...

, the tape controls were operated by Karlheinz Stockhausen.

The title ''Déserts'' suggested to Varèse not only "all physical deserts (of sand, sea, snow, of outer space, of empty streets), but also the deserts in the mind of man; not only those stripped aspects of nature that suggest bareness, aloofness, timelessness, but also that remote inner space no telescope can reach, where man is alone, a world of mystery and essential loneliness."

In Cologne, what would become the most famous electronic music studio in the world, was officially opened at the radio studios of the

NWDR

Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk (NWDR; ''Northwest German Broadcasting'') was the organization responsible for public broadcasting in the German Länder of Hamburg, Lower Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein and North Rhine-Westphalia from 22 September 1945 to ...

in 1953, though it had been in the planning stages as early as 1950 and early compositions were made and broadcast in 1951. The brainchild of

Werner Meyer-Eppler

Werner Meyer-Eppler (30 April 1913 – 8 July 1960), was a Belgian-born German physicist, experimental acoustician, phoneticist and information theorist.

Meyer-Eppler was born in Antwerp. He studied mathematics, physics, and chemistry, ...

, Robert Beyer, and

Herbert Eimert Herbert Eimert (8 April 1897 – 15 December 1972) was a German music theorist, musicologist, journalist, music critic, editor, radio producer, and composer.

Education

Herbert Eimert was born in Bad Kreuznach. He studied music theory and compo ...

(who became its first director), the studio was soon joined by Karlheinz Stockhausen and

. In his 1949 thesis ''Elektronische Klangerzeugung: Elektronische Musik und Synthetische Sprache'', Meyer-Eppler conceived the idea to synthesize music entirely from electronically produced signals; in this way, ''elektronische Musik'' was sharply differentiated from French ''musique concrète'', which used sounds recorded from acoustical sources.

In 1953, Stockhausen composed his ''

Studie I'', followed in 1954 by ''

Elektronische Studie II''—the first electronic piece to be published as a score. In 1955, more experimental and electronic studios began to appear. Notable were the creation of the

Studio di fonologia musicale di Radio Milano, a studio at the

NHK

, also known as NHK, is a Japanese public broadcaster. NHK, which has always been known by this romanized initialism in Japanese, is a statutory corporation funded by viewers' payments of a television license fee.

NHK operates two terrestr ...

in Tokyo founded by

Toshiro Mayuzumi

Toshiro Mayuzumi (黛 敏郎 ''Mayuzumi Toshirō'' ; 20 February 1929 – 10 April 1997) was a Japanese composer known for his implementation of avant-garde instrumentation alongside traditional Japanese musical techniques. His works drew i ...

, and the Philips studio at

Eindhoven, the Netherlands, which moved to the

University of Utrecht

Utrecht University (UU; nl, Universiteit Utrecht, formerly ''Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht'') is a public research university in Utrecht, Netherlands. Established , it is one of the oldest universities in the Netherlands. In 2018, it had an enrollme ...

as the

Institute of Sonology The Institute of Sonology is an education and research center for electronic music and computer music based at the Royal Conservatoire of The Hague in the Netherlands.

Background

The institute was founded at Utrecht University in 1960 under the n ...

in 1960.

"With Stockhausen and

Mauricio Kagel

Mauricio Raúl Kagel (; 24 December 1931 – 18 September 2008) was an Argentine-German composer.

Biography

Kagel was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, into an Ashkenazi Jewish family that had fled from Russia in the 1920s . He studied music, his ...

in residence,

olognebecame a year-round hive of charismatic avante-gardism." on two occasions combining electronically generated sounds with relatively conventional orchestras—in ''

Mixtur

''Mixtur'', for orchestra, 4 sine-wave generators, and 4 ring modulators, is an orchestral composition by the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, written in 1964, and is Nr. 16 in his catalogue of works. It exists in three versions: the ...

'' (1964) and ''

Hymnen, dritte Region mit Orchester'' (1967). Stockhausen stated that his listeners had told him his electronic music gave them an experience of "outer space", sensations of flying, or being in a "fantastic dream world".

Japan

The earliest group of electronic musical instruments in Japan,

Yamaha Magna Organ

This is a list of products made by Yamaha Corporation. This does not include products made by Bösendorfer, which has been a wholly owned subsidiary of Yamaha Corporation since February 1, 2008.

For products made by Yamaha Motor Company, see the ...

was built in 1935.

[Before the Second World War in Japan, several "electrical" instruments seem already to have been developed (''see :ja:電子音楽#黎明期''), and in 1935 a kind of "''electronic''" musical instrument, the ]Yamaha Magna Organ

This is a list of products made by Yamaha Corporation. This does not include products made by Bösendorfer, which has been a wholly owned subsidiary of Yamaha Corporation since February 1, 2008.

For products made by Yamaha Motor Company, see the ...

, was developed. It seems to be a multi-timbral keyboard instrument based on electrically blown free reeds with pickups, possibly similar to the electrostatic reed organ

An electric organ, also known as electronic organ, is an electronic keyboard instrument which was derived from the harmonium, pipe organ and theatre organ. Originally designed to imitate their sound, or orchestral sounds, it has since developed ...

s developed by Frederick Albert Hoschke in 1934 then manufactured by Everett and Wurlitzer

The Rudolph Wurlitzer Company, usually referred to as simply Wurlitzer, is an American company started in Cincinnati in 1853 by German immigrant (Franz) Rudolph Wurlitzer. The company initially imported stringed, woodwind and brass instruments ...

until 1961.

however, after World War II, Japanese composers such as

Minao Shibata

; September 29, 1916, Tokyo – February 2, 1996, Tokyo) was a Japanese composer.

Minao studied botany at Tokyo University, graduating in 1939, and made further studies in the fine arts while studying music privately with Saburo Moroi and playin ...

knew of the development of electronic musical instruments. By the late 1940s, Japanese composers began experimenting with electronic music and institutional sponsorship enabled them to experiment with advanced equipment. Their infusion of

Asian music

Asian music encompasses numerous musical styles originating in many Asian countries.

Musical traditions in Asia

* Music of Central Asia

** Music of Afghanistan (when included in the definition of Central Asia)

** Music of Kazakhstan

** Music ...

into the emerging genre would eventually support Japan's popularity in the development of music technology several decades later.

[.]

Following the foundation of electronics company

Sony

, commonly stylized as SONY, is a Japanese multinational conglomerate corporation headquartered in Minato, Tokyo, Japan. As a major technology company, it operates as one of the world's largest manufacturers of consumer and professiona ...

in 1946, composers

Toru Takemitsu TORU or Toru may refer to:

* TORU, spacecraft system

* Toru (given name), Japanese male given name

* Toru, Pakistan, village in Mardan District of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

*Tõru

Tõru is a village in Saaremaa Parish, Saare County in western ...

and Minao Shibata independently explored possible uses for electronic technology to produce music. Takemitsu had ideas similar to

musique concrète, which he was unaware of, while Shibata foresaw the development of synthesizers and predicted a drastic change in music. Sony began producing popular

magnetic tape recorders for government and public use.

[.]

The avant-garde collective

Jikken Kōbō (Experimental Workshop), founded in 1950, was offered access to emerging audio technology by Sony. The company hired Toru Takemitsu to demonstrate their tape recorders with compositions and performances of electronic tape music. The first electronic tape pieces by the group were "Toraware no Onna" ("Imprisoned Woman") and "Piece B", composed in 1951 by Kuniharu Akiyama.

[.] Many of the

electroacoustic tape pieces they produced were used as incidental music for radio, film, and theatre. They also held concerts employing a

slide show

A slide show (slideshow) is a presentation of a series of still images ( slides) on a projection screen or electronic display device, typically in a prearranged sequence. The changes may be automatic and at regular intervals or they may be manu ...

synchronized with a recorded soundtrack. Composers outside of the Jikken Kōbō, such as

Yasushi Akutagawa

was a Japanese composer and conductor. His father was Ryūnosuke Akutagawa.

Biography

Akutagawa was born and raised in Tabata, Tokyo, the son of writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa.

Akutagawa studied composition with Kunihiko Hashimoto, Kan'ichi S ...

, Saburo Tominaga, and

Shirō Fukai

was a Japanese composer.The Japan biographical encyclopedia & who's who: Issue 3 Rengō Puresu Sha - 1964 "FUKAI Shiro (1907- ) Composer. Musical critic. Born in Akita Prefecture. Graduated from the Science Section of the Seventh Higher School ( ...

, were also experimenting with

radiophonic

The BBC Radiophonic Workshop was one of the sound effects units of the BBC, created in 1958 to produce incidental sounds and new music for radio and, later, television. The unit is known for its experimental and pioneering work in electron ...

tape music between 1952 and 1953.

Musique concrète was introduced to Japan by

Toshiro Mayuzumi

Toshiro Mayuzumi (黛 敏郎 ''Mayuzumi Toshirō'' ; 20 February 1929 – 10 April 1997) was a Japanese composer known for his implementation of avant-garde instrumentation alongside traditional Japanese musical techniques. His works drew i ...

, who was influenced by a Pierre Schaeffer concert. From 1952, he composed tape music pieces for a comedy film, a radio broadcast, and a radio drama.

[.] However, Schaeffer's concept of ''

sound object

In musique concrete and electronic music theory the term sound object (originally ''l'objet sonore'') is used to refer to a primary unit of sonic material and often specifically refers to recorded sound rather than written music using manuscript o ...

'' was not influential among Japanese composers, who were mainly interested in overcoming the restrictions of human performance.

[.] This led to several Japanese

electroacoustic musicians making use of

serialism

In music, serialism is a method of Musical composition, composition using series of pitches, rhythms, dynamics, timbres or other elements of music, musical elements. Serialism began primarily with Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, thou ...

and

twelve-tone technique

The twelve-tone technique—also known as dodecaphony, twelve-tone serialism, and (in British usage) twelve-note composition—is a method of musical composition first devised by Austrian composer Josef Matthias Hauer, who published his "law o ...

s,

evident in

Yoshirō Irino

was a Japanese composer.

Biography

Irino was born in Soviet Vladivostok. He attended high school in Tokyo and went on to study economics at Tokyo Imperial University (now University of Tokyo).

After World War II, Irino, along with colleagues ...

's 1951

dodecaphonic

The twelve-tone technique—also known as dodecaphony, twelve-tone serialism, and (in British usage) twelve-note composition—is a method of musical composition first devised by Austrian composer Josef Matthias Hauer, who published his "law o ...

piece "Concerto da

Camera",

in the organization of electronic sounds in Mayuzumi's "X, Y, Z for Musique Concrète", and later in Shibata's electronic music by 1956.

[.]

Modelling the NWDR studio in Cologne, established an

NHK electronic music studio in Tokyo in 1954, which became one of the world's leading electronic music facilities.The NHK electronic music studio was equipped with technologies such as tone-generating and audio processing equipment, recording and radiophonic equipment, ondes Martenot,

Monochord

A monochord, also known as sonometer (see below), is an ancient musical and scientific laboratory instrument, involving one (mono-) string ( chord). The term ''monochord'' is sometimes used as the class-name for any musical stringed instrument h ...

and

Melochord

Harald Bode (October 19, 1909 – January 15, 1987) was a German engineer and pioneer in the development of electronic musical instruments.

Biography

Harald Bode was born in 1909 in Hamburg, Germany. At the age of 18 he lost his parents an ...

, sine-wave

oscillators, tape recorders,

ring modulator

In electronics, ring modulation is a signal processing function, an implementation of frequency mixing, in which two signals are combined to yield an output signal. One signal, called the carrier, is typically a sine wave or another simple ...

s,

band-pass filter

A band-pass filter or bandpass filter (BPF) is a device that passes frequencies within a certain range and rejects (attenuates) frequencies outside that range.

Description

In electronics and signal processing, a filter is usually a two-port ...

s, and four- and eight-channel

mixers. Musicians associated with the studio included Toshiro Mayuzumi, Minao Shibata, Joji Yuasa,

Toshi Ichiyanagi

was a Japanese avant-garde composer and pianist. One of the leading composers in Japan during the postwar era, Ichiyanagi worked in a range of genres, composing Western-style operas and orchestral and chamber works, as well as compositions usin ...

, and Toru Takemitsu. The studio's first electronic compositions were completed in 1955, including Mayuzumi's five-minute pieces "Studie I: Music for Sine Wave by Proportion of Prime Number", "Music for Modulated Wave by Proportion of Prime Number" and "Invention for Square Wave and Sawtooth Wave" produced using the studio's various tone-generating capabilities, and Shibata's 20-minute stereo piece "Musique Concrète for Stereophonic Broadcast".

United States

In the United States, electronic music was being created as early as 1939, when John Cage published ''

Imaginary Landscape, No. 1

''Imaginary Landscape No. 1'' is a composition for records of constant and variable frequency, large chinese cymbal and string piano by American composer John Cage and the first in the series of Imaginary Landscapes. It was composed in 1939.

C ...

'', using two variable-speed turntables, frequency recordings, muted piano, and cymbal, but no electronic means of production. Cage composed five more "Imaginary Landscapes" between 1942 and 1952 (one withdrawn), mostly for percussion ensemble, though No. 4 is for twelve radios and No. 5, written in 1952, uses 42 recordings and is to be realized as a magnetic tape. According to Otto Luening, Cage also performed ''

Williams Mix

''Williams Mix'' (1951–1953) is a 4'15" musique concrete composition by John Cage for eight simultaneously played independent quarter-inch magnetic tapes. The first octophonic music, the piece was created by Cage with the assistance of Earle B ...

'' at Donaueschingen in 1954, using eight loudspeakers, three years after his alleged collaboration. ''Williams Mix'' was a success at the

Donaueschingen Festival

The Donaueschingen Festival (german: Donaueschinger Musiktage, links=no) is a festival for new music that takes place every October in the small town of Donaueschingen in south-western Germany. Founded in 1921, it is considered the oldest festiva ...

, where it made a "strong impression".

The Music for Magnetic Tape Project was formed by members of the

New York School (

John Cage,

Earle Brown

Earle Brown (December 26, 1926 – July 2, 2002) was an American composer who established his own formal and notational systems. Brown was the creator of "open form," a style of musical construction that has influenced many composers since� ...

,

Christian Wolff,

David Tudor

David Eugene Tudor (January 20, 1926 – August 13, 1996) was an American pianist and composer of experimental music.

Life and career

Tudor was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He studied piano with Irma Wolpe and composition with Stefan W ...

, and

Morton Feldman

Morton Feldman (January 12, 1926 – September 3, 1987) was an American composer. A major figure in 20th-century classical music, Feldman was a pioneer of indeterminate music, a development associated with the experimental New York School ...

),

[.] and lasted three years until 1954. Cage wrote of this collaboration: "In this social darkness, therefore, the work of Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, and Christian Wolff continues to present a brilliant light, for the reason that at the several points of notation, performance, and audition, action is provocative."

[.]

Cage completed ''Williams Mix'' in 1953 while working with the Music for Magnetic Tape Project.

["Carolyn Brown arle Brown's wifewas to dance in Cunningham's company, while Brown himself was to participate in Cage's 'Project for Music for Magnetic Tape.'... funded by Paul Williams (dedicatee of the 1953 ''Williams Mix''), who—like Robert Rauschenberg—was a former student of Black Mountain College, which Cage and Cunnigham had first visited in the summer of 1948" ().] The group had no permanent facility, and had to rely on borrowed time in commercial sound studios, including the studio of

Bebe and Louis Barron.

Columbia-Princeton Center

In the same year

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

purchased its first tape recorder—a professional

Ampex

Ampex is an American electronics company founded in 1944 by Alexander M. Poniatoff as a spin-off of Dalmo-Victor. The name AMPEX is a portmanteau, created by its founder, which stands for Alexander M. Poniatoff Excellence.AbramsoThe History ...

machine—to record concerts. Vladimir Ussachevsky, who was on the music faculty of Columbia University, was placed in charge of the device, and almost immediately began experimenting with it.

Herbert Russcol writes: "Soon he was intrigued with the new sonorities he could achieve by recording musical instruments and then superimposing them on one another."

[.] Ussachevsky said later: "I suddenly realized that the tape recorder could be treated as an instrument of sound transformation."

On Thursday, 8 May 1952, Ussachevsky presented several demonstrations of tape music/effects that he created at his Composers Forum, in the McMillin Theatre at Columbia University. These included ''Transposition, Reverberation, Experiment, Composition'', and ''Underwater Valse''. In an interview, he stated: "I presented a few examples of my discovery in a public concert in New York together with other compositions I had written for conventional instruments."

Otto Luening, who had attended this concert, remarked: "The equipment at his disposal consisted of an Ampex tape recorder . . . and a simple box-like device designed by the brilliant young engineer, Peter Mauzey, to create feedback, a form of mechanical reverberation. Other equipment was borrowed or purchased with personal funds."

[.]

Just three months later, in August 1952, Ussachevsky traveled to Bennington, Vermont, at Luening's invitation to present his experiments. There, the two collaborated on various pieces. Luening described the event: "Equipped with earphones and a flute, I began developing my first tape-recorder composition. Both of us were fluent improvisors and the medium fired our imaginations."

They played some early pieces informally at a party, where "a number of composers almost solemnly congratulated us saying, 'This is it' ('it' meaning the music of the future)."

Word quickly reached New York City. Oliver Daniel telephoned and invited the pair to "produce a group of short compositions for the October concert sponsored by the American Composers Alliance and Broadcast Music, Inc., under the direction of

Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appear ...

at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. After some hesitation, we agreed. . . .

Henry Cowell placed his home and studio in Woodstock, New York, at our disposal. With the borrowed equipment in the back of Ussachevsky's car, we left Bennington for Woodstock and stayed two weeks. . . . In late September 1952, the travelling laboratory reached Ussachevsky's living room in New York, where we eventually completed the compositions."

Two months later, on 28 October, Vladimir Ussachevsky and Otto Luening presented the first Tape Music concert in the United States. The concert included Luening's ''Fantasy in Space'' (1952)—"an impressionistic

virtuoso piece"

using manipulated recordings of flute—and ''Low Speed'' (1952), an "exotic composition that took the flute far below its natural range."

Both pieces were created at the home of Henry Cowell in Woodstock, New York. After several concerts caused a sensation in New York City, Ussachevsky and Luening were invited onto a live broadcast of NBC's Today Show to do an interview demonstration—the first televised electroacoustic performance. Luening described the event: "I improvised some

lutesequences for the tape recorder. Ussachevsky then and there put them through electronic transformations."

The score for ''

Forbidden Planet

''Forbidden Planet'' is a 1956 American science fiction film from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, produced by Nicholas Nayfack, and directed by Fred M. Wilcox from a script by Cyril Hume that was based on an original film story by Allen Adler and Irvi ...

'', by

Louis and Bebe Barron

Bebe Barron ( – ) and Louis Barron ( – ) were two American pioneers in the field of electronic music. They are credited with writing the first electronic music for magnetic tape composed in the United States, and the first entirely ele ...

,

["From at least Louis and Bebbe Barron's soundtrack for ''The Forbidden Planet'' onwards, electronic music—in particular synthetic timbre—has impersonated alien worlds in film" ().] was entirely composed using custom-built electronic circuits and tape recorders in 1956 (but no synthesizers in the modern sense of the word).

Australia

The world's first computer to play music was

CSIRAC

CSIRAC (; ''Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Automatic Computer''), originally known as CSIR Mk 1, was Australia's first digital computer, and the fifth stored program computer in the world. It is the oldest surviving first-gener ...

, which was designed and built by

Trevor Pearcey

Trevor Pearcey (5 March 1919 – 27 January 1998) was a British-born Australian scientist, who created CSIRAC, one of the first stored-program electronic computers in the world.

Born in Woolwich, London, he graduated from Imperial College in 19 ...

and Maston Beard. Mathematician Geoff Hill programmed the CSIRAC to play popular musical melodies from the very early 1950s. In 1951 it publicly played the

Colonel Bogey March

The "Colonel Bogey March" is a British march that was composed in 1914 by Lieutenant F. J. Ricketts (1881–1945) (pen name Kenneth J. Alford), a British Army bandmaster who later became the director of music for the Royal Marines at Plymouth ...

, of which no known recordings exist, only the accurate reconstruction. However,

CSIRAC

CSIRAC (; ''Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Automatic Computer''), originally known as CSIR Mk 1, was Australia's first digital computer, and the fifth stored program computer in the world. It is the oldest surviving first-gener ...

played standard repertoire and was not used to extend musical thinking or composition practice. CSIRAC was never recorded, but the music played was accurately reconstructed. The oldest known recordings of computer-generated music were played by the

Ferranti Mark 1

The Ferranti Mark 1, also known as the Manchester Electronic Computer in its sales literature, and thus sometimes called the Manchester Ferranti, was produced by British electrical engineering firm Ferranti Ltd. It was the world's first commer ...

computer, a commercial version of the

Baby

An infant or baby is the very young offspring of human beings. ''Infant'' (from the Latin word ''infans'', meaning 'unable to speak' or 'speechless') is a formal or specialised synonym for the common term ''baby''. The terms may also be used to ...

Machine from the

University of Manchester

, mottoeng = Knowledge, Wisdom, Humanity

, established = 2004 – University of Manchester Predecessor institutions: 1956 – UMIST (as university college; university 1994) 1904 – Victoria University of Manchester 1880 – Victoria Univer ...

in the autumn of 1951.

The music program was written by

Christopher Strachey

Christopher S. Strachey (; 16 November 1916 – 18 May 1975) was a British computer scientist. He was one of the founders of denotational semantics, and a pioneer in programming language design and computer time-sharing.F. J. Corbató, et al. ...

.

Mid-to-late 1950s

The impact of computers continued in 1956.

Lejaren Hiller

Lejaren Arthur Hiller Jr. (February 23, 1924, New York City – January 26, 1994, Buffalo, New York)[Lejaren Hi ...](_blank)

and

Leonard Isaacson composed ''

Illiac Suite

''Illiac Suite'' (later retitled String Quartet No. 4)Andrew Stiller, "Hiller, Lejaren (Arthur)", ''Grove Music Online'' (reviewed December 3, 2010; accessed December 14, 2014). is a 1957 composition for string quartet which is generally agreed t ...

'' for

string quartet, the first complete work of computer-assisted composition using

algorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm () is a finite sequence of rigorous instructions, typically used to solve a class of specific Computational problem, problems or to perform a computation. Algorithms are used as specificat ...

ic composition. "... Hiller postulated that a computer could be taught the rules of a particular style and then called on to compose accordingly." Later developments included the work of

Max Mathews

Max Vernon Mathews (November 13, 1926 in Columbus, Nebraska, USA – April 21, 2011 in San Francisco, CA, USA) was a pioneer of computer music.

Biography

Mathews studied electrical engineering at the California Institute of Technology and the Ma ...

at

Bell Laboratories

Nokia Bell Labs, originally named Bell Telephone Laboratories (1925–1984),

then AT&T Bell Laboratories (1984–1996)

and Bell Labs Innovations (1996–2007),

is an American industrial research and scientific development company owned by mult ...

, who developed the influential

MUSIC I

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

program in 1957, one of the first computer programs to play electronic music.

Vocoder

A vocoder (, a portmanteau of ''voice'' and ''encoder'') is a category of speech coding that analyzes and synthesizes the human voice signal for audio data compression, multiplexing, voice encryption or voice transformation.

The vocoder was ...

technology was also a major development in this early era. In 1956, Stockhausen composed ''

Gesang der Jünglinge

''Gesang der Jünglinge'' (literally "Song of the Youths") is an electronic music work by Karlheinz Stockhausen. It was realized in 1955–56 at the Westdeutscher Rundfunk studio in Cologne and is Work Number 8 in the composer's catalog. The vo ...

'', the first major work of the Cologne studio, based on a text from the ''

Book of Daniel

The Book of Daniel is a 2nd-century BC biblical apocalypse with a 6th century BC setting. Ostensibly "an account of the activities and visions of Daniel, a noble Jew exiled at Babylon", it combines a prophecy of history with an eschatology ...

''. An important technological development of that year was the invention of the

Clavivox synthesizer by

Raymond Scott

Raymond Scott (born Harry Warnow; September 10, 1908 – February 8, 1994) was an American composer, band leader, pianist, record producer, and inventor of electronic instruments.

Though Scott never scored cartoon soundtracks, his music is ...

with subassembly by

Robert Moog

Robert Arthur Moog ( ; May 23, 1934 – August 21, 2005) was an American engineer and electronic music pioneer. He was the founder of the synthesizer manufacturer Moog Music and the inventor of the first commercial synthesizer, the Moog synthesi ...

.

In 1957, Kid Baltan (

Dick Raaymakers

Dick Raaijmakers (Maastricht, 1 September 1930 – The Hague, 4 September 2013), also known as Dick Raaymakers or Kid Baltan, was a Dutch composer, theater maker and theorist. He is considered a pioneer in the field of electronic music and tape mu ...

) and

Tom Dissevelt

Thomas Dissevelt (4 March 1921, Leiden – 1989) was a Dutch composer and musician. He is known as a pioneer in the merging of electronic music and jazz. He married Rina Reys, sister of Rita Reys, in 1946.

Tom Dissevelt was also known as bass ...

released their debut album, ''Song Of The Second Moon'', recorded at the Philips studio in the Netherlands. The public remained interested in the new sounds being created around the world, as can be deduced by the inclusion of Varèse's ''

Poème électronique

''Poème électronique'' (English Translation: "Electronic Poem") is an 8-minute piece of electronic music by composer Edgard Varèse, written for the Philips Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World's Fair. The Philips corporation commissioned L ...

'', which was played over four hundred loudspeakers at the Philips Pavilion of the 1958

Brussels World Fair

Expo 58, also known as the 1958 Brussels World's Fair (french: Exposition Universelle et Internationale de Bruxelles de 1958, nl, Brusselse Wereldtentoonstelling van 1958), was a world's fair held on the Heysel/Heizel Plateau in Brussels, Bel ...

. That same year,

Mauricio Kagel

Mauricio Raúl Kagel (; 24 December 1931 – 18 September 2008) was an Argentine-German composer.

Biography

Kagel was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, into an Ashkenazi Jewish family that had fled from Russia in the 1920s . He studied music, his ...

, an

Argentine composer, composed ''Transición II''. The work was realized at the WDR studio in Cologne. Two musicians performed on the piano, one in the traditional manner, the other playing on the strings, frame, and case. Two other performers used tape to unite the presentation of live sounds with the future of prerecorded materials from later on and its past of recordings made earlier in the performance.

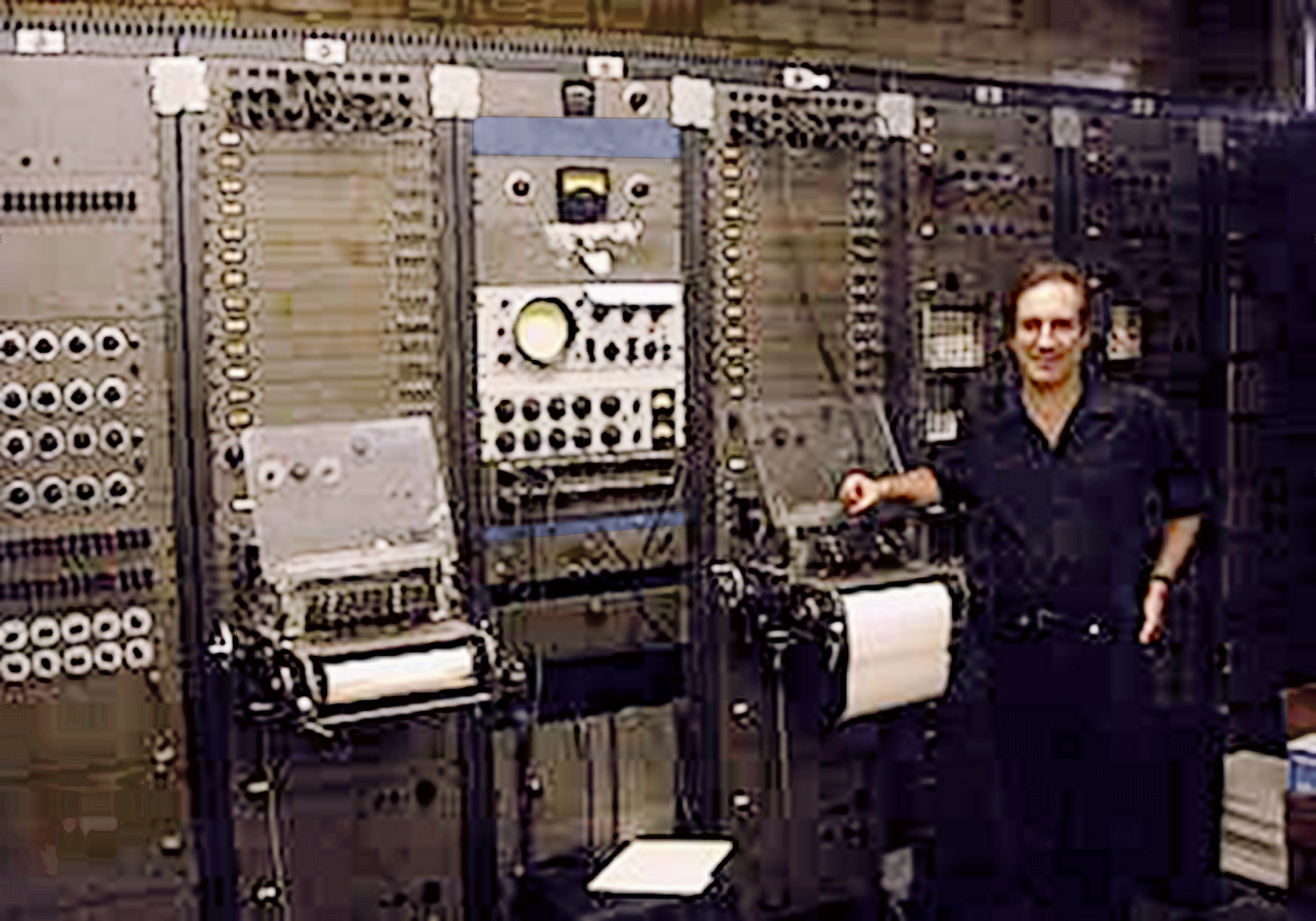

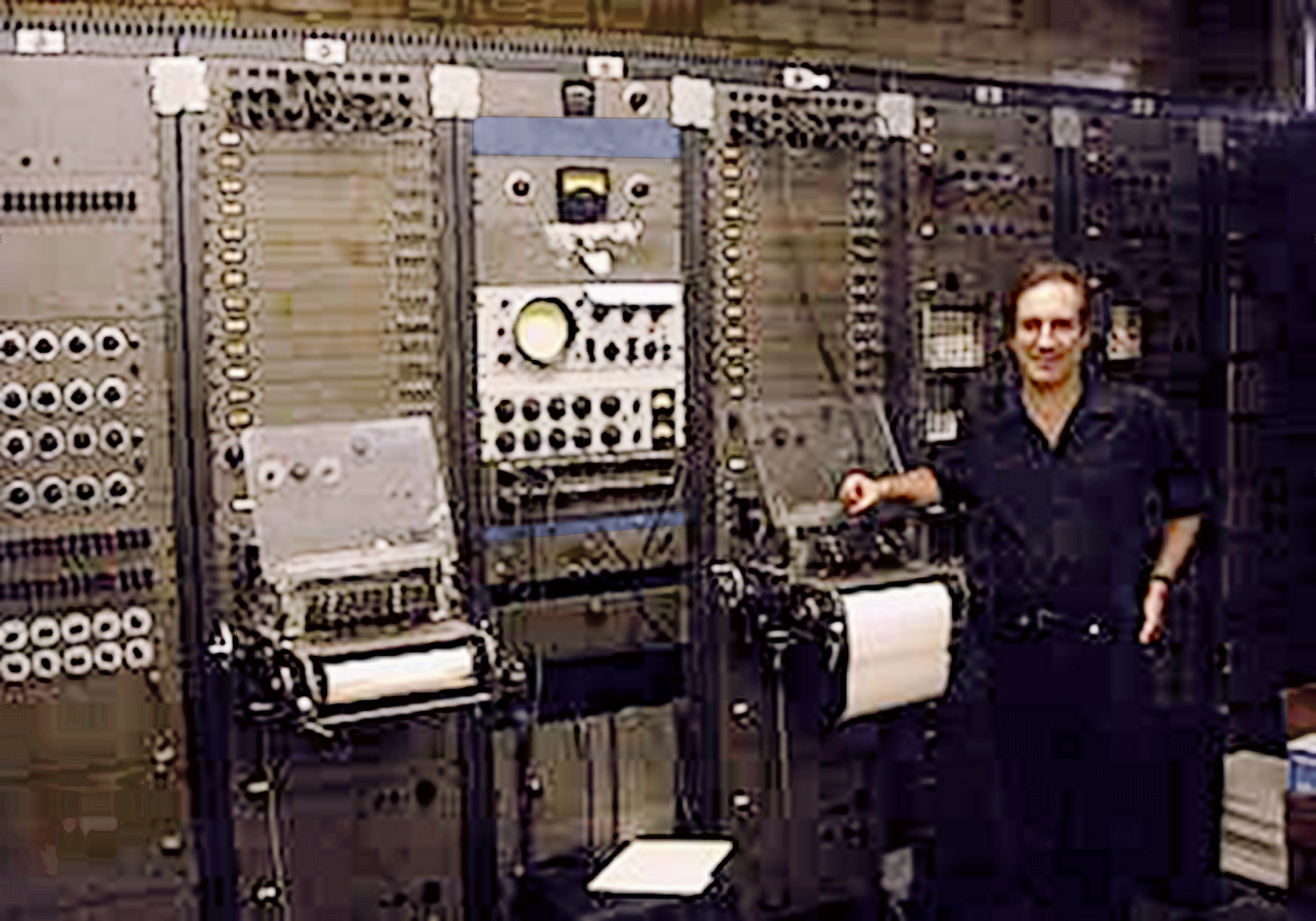

In 1958, Columbia-Princeton developed the

RCA Mark II Sound Synthesizer

The RCA Mark II Sound Synthesizer (nicknamed ''Victor'') was the first programmable electronic synthesizer and the flagship piece of equipment at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. Designed by Herbert Belar and Harry Olson at RCA, w ...

, the first programmable synthesizer. Prominent composers such as Vladimir Ussachevsky, Otto Luening,

Milton Babbitt,

Charles Wuorinen, Halim El-Dabh,

Bülent Arel and

Mario Davidovsky

Mario Davidovsky (March 4, 1934 – August 23, 2019) was an Argentine-American composer. Born in Argentina, he emigrated in 1960 to the United States, where he lived for the remainder of his life. He is best known for his series of compositions ca ...

used the

RCA

The RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded as the Radio Corporation of America in 1919. It was initially a patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse, AT&T Corporation and United Fruit Comp ...

Synthesizer extensively in various compositions. One of the most influential composers associated with the early years of the studio was Egypt's

Halim El-Dabh

Halim Abdul Messieh El-Dabh ( ar, حليم عبد المسيح الضبع, ''Ḥalīm ʻAbd al-Masīḥ al-Ḍab''ʻ; March 4, 1921 – September 2, 2017) was an Egyptian-American composer, musician, ethnomusicologist, and educator, who had ...

who, after having developed the earliest known electronic tape music in 1944,

became more famous for ''Leiyla and the Poet'', a 1959 series of electronic compositions that stood out for its immersion and seamless

fusion

Fusion, or synthesis, is the process of combining two or more distinct entities into a new whole.

Fusion may also refer to:

Science and technology Physics

*Nuclear fusion, multiple atomic nuclei combining to form one or more different atomic nucl ...

of electronic and

folk music

Folk music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be called world music. Traditional folk music has b ...

, in contrast to the more mathematical approach used by

serial composers of the time such as Babbitt. El-Dabh's ''Leiyla and the Poet'', released as part of the album ''

Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center

The Computer Music Center (CMC) at Columbia University is the oldest center for electronic and computer music research in the United States. It was founded in the 1950s as the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center.

Location

The CMC is hou ...

'' in 1961, would be cited as a strong influence by a number of musicians, ranging from

Neil Rolnick,

Charles Amirkhanian

Charles Benjamin Amirkhanian (born January 19, 1945; Fresno, California) is an American composer. He is a percussionist, sound poet, and radio producer of Armenian origin. He is mostly known for his electroacoustic and text-sound music. Perfor ...

and

Alice Shields to rock musicians

Frank Zappa and

The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band

The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band (WCPAEB) was an American psychedelic rock band formed in Los Angeles, California in 1965. The group created music that possessed an eerie, and at times sinister atmosphere, and contained material that was ...

.

Following the emergence of differences within the GRMC (Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète) Pierre Henry, Philippe Arthuys, and several of their colleagues, resigned in April 1958. Schaeffer created a new collective, called

Groupe de Recherches Musicales

A group is a military unit or a military formation that is most often associated with military aviation.

Air and aviation groups

The terms group and wing differ significantly from one country to another, as well as between different branches ...

(GRM) and set about recruiting new members including

Luc Ferrari

Luc Ferrari (February 5, 1929 – August 22, 2005) was a French composer of Italian heritage and a pioneer in musique concrète and electroacoustic music. He was a founding member of RTF's Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRMC), working alongsid ...

,

Beatriz Ferreyra

Beatriz Mercedes Ferreyra (born 21 June 1937) is an Argentine composer. She lives and works in Hameau de Hodeng, France.

Early work and study

Ferreyra was born in Cordoba, Argentina, and studied piano with Celia Bronstein in Buenos Aires. S ...

,

François-Bernard Mâche

François-Bernard Mâche (born 4 April 1935, Clermont-Ferrand) is a French composer of contemporary music.

Biography

Born into a family of musicians, he is a former student of Émile Passani and Olivier Messiaen and has also received a diplom ...

,

Iannis Xenakis

Giannis Klearchou Xenakis (also spelled for professional purposes as Yannis or Iannis Xenakis; el, Γιάννης "Ιωάννης" Κλέαρχου Ξενάκης, ; 29 May 1922 – 4 February 2001) was a Romanian-born Greek-French avant-garde c ...

,

Bernard Parmegiani

Bernard Parmegiani (27 October 1927 − 21 November 2013) was a French composer best known for his electronic or acousmatic music.

Biography

Between 1957 and 1961 he studied mime with Jacques Lecoq, a period he later regarded as important to his ...

, and Mireille Chamass-Kyrou. Later arrivals included

Ivo Malec

Ivo Malec (30 March 1925, in Zagreb – 14 August 2019, in Paris) was a Croatian-born French composer, music educator and conductor. One of the earliest Yugoslav composers to obtain high international regard, his works have been performed by s ...

, Philippe Carson, Romuald Vandelle, Edgardo Canton and

François Bayle

François Bayle (born 27 April 1932, in Toamasina, Madagascar) is a composer of Electronic Music, Musique concrète. He coined the term ''Acousmatic Music''.

Career

In the 1950s he studied with Olivier Messiaen, Pierre Schaeffer and Karlheinz Sto ...

.

Expansion: 1960s

These were fertile years for electronic music—not just for academia, but for independent artists as synthesizer technology became more accessible. By this time, a strong community of composers and musicians working with new sounds and instruments was established and growing. 1960 witnessed the composition of Luening's ''Gargoyles'' for violin and tape as well as the premiere of Stockhausen's ''

Kontakte

''Kontakte'' ("Contacts") is an electronic music work by Karlheinz Stockhausen, realized in 1958–60 at the ''Westdeutscher Rundfunk'' (WDR) electronic-music studio in Cologne with the assistance of Gottfried Michael Koenig. The score is Nr. 12 ...

'' for electronic sounds, piano, and percussion. This piece existed in two versions—one for 4-channel tape, and the other for tape with human performers. "In ''Kontakte'', Stockhausen abandoned traditional musical form based on linear development and dramatic climax. This new approach, which he termed 'moment form', resembles the 'cinematic splice' techniques in early twentieth-century film."

The

theremin

The theremin (; originally known as the ætherphone/etherphone, thereminophone or termenvox/thereminvox) is an electronic musical instrument controlled without physical contact by the performer (who is known as a thereminist). It is named afte ...

had been in use since the 1920s but it attained a degree of popular recognition through its use in science-fiction film soundtrack music in the 1950s (e.g.,

Bernard Herrmann

Bernard Herrmann (born Maximillian Herman; June 29, 1911December 24, 1975) was an American composer and conductor best known for his work in composing for films. As a conductor, he championed the music of lesser-known composers. He is widely r ...

's classic score for ''

The Day the Earth Stood Still

''The Day the Earth Stood Still'' (a.k.a. ''Farewell to the Master'' and ''Journey to the World'') is a 1951 American science fiction film from 20th Century Fox, produced by Julian Blaustein and directed by Robert Wise. It stars Michael Re ...

'').

In the UK in this period, the

BBC Radiophonic Workshop

The BBC Radiophonic Workshop was one of the sound effects units of the BBC, created in 1958 to produce incidental sounds and new music for radio and, later, television. The unit is known for its experimental and pioneering work in electroni ...

(established in 1958) came to prominence, thanks in large measure to their work on the BBC science-fiction series ''

Doctor Who''. One of the most influential British electronic artists in this period was Workshop staffer

Delia Derbyshire

Delia Ann Derbyshire (5 May 1937 – 3 July 2001) was an English musician and composer of electronic music. She carried out notable work with the BBC Radiophonic Workshop during the 1960s, including her electronic arrangement of the theme ...

, who is now famous for her 1963 electronic realisation of the iconic

''Doctor Who'' theme, composed by

Ron Grainer

Ronald Erle Grainer (11 August 1922 – 21 February 1981) was an Australian composer who worked for most of his professional career in the United Kingdom. He is mostly remembered for his television and film score music, especially the theme mus ...

.

During the time of the

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

fellowship for studies in electronic music (1958)

Josef Tal

Josef Tal ( he, יוסף טל; September 18, 1910 – August 25, 2008) was an Israeli composer. He wrote three Hebrew operas; four German operas, dramatic scenes; six symphonies; 13 concerti; chamber music, including three string quartets; ins ...

went on a study tour in the US and Canada. He summarized his conclusions in two articles that he submitted to UNESCO. In 1961, he established the ''Centre for Electronic Music in Israel'' at

The Hebrew University

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI; he, הַאוּנִיבֶרְסִיטָה הַעִבְרִית בִּירוּשָׁלַיִם) is a public university, public research university based in Jerusalem, Israel. Co-founded by Albert Einstein ...

of Jerusalem. In 1962,

Hugh Le Caine

Hugh Le Caine (May 27, 1914 – July 3, 1977) was a Canadian physicist, composer, and instrument builder.

Le Caine was brought up in Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay) in northwestern Ontario. At a young age, he began making musical instruments. In yo ...

arrived in Jerusalem to install his ''Creative Tape Recorder'' in the centre. In the 1990s Tal conducted, together with Dr. Shlomo Markel, in cooperation with the

Technion – Israel Institute of Technology

The Technion – Israel Institute of Technology ( he, הטכניון – מכון טכנולוגי לישראל) is a public research university located in Haifa, Israel. Established in 1912 under the dominion of the Ottoman Empire, the Technion ...

, and the

Volkswagen Foundation

The Volkswagen Foundation (German: ''VolkswagenStiftung'') is the largest German private nonprofit organization involved in the promotion and support of academic research. It is not affiliated to the present company, the Volkswagen Group.

It wa ...

a research project ('Talmark') aimed at the development of a novel musical notation system for electronic music.

Milton Babbitt composed his first electronic work using the synthesizer—his ''Composition for Synthesizer'' (1961)—which he created using the RCA synthesizer at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center.

The collaborations also occurred across oceans and continents. In 1961, Ussachevsky invited Varèse to the Columbia-Princeton Studio (CPEMC). Upon arrival, Varese embarked upon a revision of ''Déserts''. He was assisted by

Mario Davidovsky

Mario Davidovsky (March 4, 1934 – August 23, 2019) was an Argentine-American composer. Born in Argentina, he emigrated in 1960 to the United States, where he lived for the remainder of his life. He is best known for his series of compositions ca ...

and

Bülent Arel.

The intense activity occurring at CPEMC and elsewhere inspired the establishment of the

San Francisco Tape Music Center

The San Francisco Tape Music Center, or SFTMC, was founded in the summer of 1962 by composers Ramon Sender and Morton Subotnick as a collaborative, "non profit corporation developed and maintained" by local composers working with tape recorders a ...

in 1963 by

Morton Subotnick

Morton Subotnick (born April 14, 1933) is an American composer of electronic music, best known for his 1967 composition '' Silver Apples of the Moon'', the first electronic work commissioned by a record company, Nonesuch. He was one of the foun ...

, with additional members

Pauline Oliveros

Pauline Oliveros (May 30, 1932 – November 24, 2016) was an American composer, accordionist and a central figure in the development of post-war experimental and electronic music.

She was a founding member of the San Francisco Tape Music Cente ...

,

Ramon Sender

Ramón Sender Barayón (born October 29, 1934) is a composer, visual artist and writer. He was the co-founder with Morton Subotnick of the San Francisco Tape Music Center in 1962. He is the son of Spanish writer Ramón J. Sender.

Education ...

, Anthony Martin, and

Terry Riley

Terrence Mitchell "Terry" Riley (born June 24, 1935) is an American composer and performing musician best known as a pioneer of the minimalist school of composition. Influenced by jazz and Indian classical music, his music became notable for ...

.

Later, the Center moved to

Mills College

Mills College at Northeastern University is a private college in Oakland, California and part of Northeastern University's global university system. Mills College was founded as the Young Ladies Seminary in 1852 in Benicia, California; it was ...

, directed by

Pauline Oliveros

Pauline Oliveros (May 30, 1932 – November 24, 2016) was an American composer, accordionist and a central figure in the development of post-war experimental and electronic music.

She was a founding member of the San Francisco Tape Music Cente ...

, where it is today known as the Center for Contemporary Music.

["A central figure in post-war electronic art music, ]Pauline Oliveros

Pauline Oliveros (May 30, 1932 – November 24, 2016) was an American composer, accordionist and a central figure in the development of post-war experimental and electronic music.

She was a founding member of the San Francisco Tape Music Cente ...

. 1932is one of the original members of the San Francisco Tape Music Center (along with Morton Subotnick, Ramon Sender, Terry Riley, and Anthony Martin), which was the resource on the U.S. west coast for electronic music during the 1960s. The Center later moved to Mills College, where she was its first director, and is now called the Center for Contemporary Music." from CD liner notes, "Accordion & Voice", Pauline Oliveros, Record Label: Important, Catalog number IMPREC140: 793447514024. Pietro Grossi was an Italian pioneer of computer composition and tape music, who first experimented with electronic techniques in the early sixties. Grossi was a cellist and composer, born in Venice in 1917. He founded the S 2F M (Studio de Fonologia Musicale di Firenze) in 1963 to experiment with electronic sound and composition.

Simultaneously in San Francisco, composer Stan Shaff and equipment designer Doug McEachern, presented the first "Audium" concert at San Francisco State College (1962), followed by work at the

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) is a modern and contemporary art museum located in San Francisco, California. A nonprofit organization, SFMOMA holds an internationally recognized collection of modern and contemporary art, and wa ...

(1963), conceived of as in time, controlled movement of sound in space. Twelve speakers surrounded the audience, four speakers were mounted on a rotating, mobile-like construction above.

[.] In an SFMOMA performance the following year (1964), ''San Francisco Chronicle'' music critic Alfred Frankenstein commented, "the possibilities of the space-sound continuum have seldom been so extensively explored".

In 1967, the first

Audium, a "sound-space continuum" opened, holding weekly performances through 1970. In 1975, enabled by seed money from the

National Endowment for the Arts

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that offers support and funding for projects exhibiting artistic excellence. It was created in 1965 as an independent agency of the federal ...