The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an

imperial realm that controlled much of

Southeast Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe is a geographical sub-region of Europe, consisting primarily of the region of the Balkans, as well as adjacent regions and Archipelago, archipelagos. There are overlapping and conflicting definitions of t ...

,

West Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

, and

North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern

Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

, between the early 16th and early 18th centuries.

The empire emerged from a

''beylik'', or

principality

A principality (or sometimes princedom) is a type of monarchy, monarchical state or feudalism, feudal territory ruled by a prince or princess. It can be either a sovereign state or a constituent part of a larger political entity. The term "prin ...

, founded in northwestern

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

in by the

Turkoman tribal leader

Osman I

Osman I or Osman Ghazi (; or ''Osman Gazi''; died 1323/4) was the eponymous founder of the Ottoman Empire (first known as a bey, beylik or emirate). While initially a small Turkoman (ethnonym), Turkoman principality during Osman's lifetime, h ...

. His successors

conquered

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or legal prohibitions against conquest ...

much of Anatolia and expanded into the

Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

by the mid-14th century, transforming their

petty kingdom

A petty kingdom is a kingdom described as minor or "petty" (from the French 'petit' meaning small) by contrast to an empire or unified kingdom that either preceded or succeeded it (e.g. the numerous kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England unified into t ...

into a transcontinental empire. The Ottomans ended the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

with the

conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by

Mehmed II

Mehmed II (; , ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror (; ), was twice the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from August 1444 to September 1446 and then later from February 1451 to May 1481.

In Mehmed II's first reign, ...

. With its capital at

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

(modern-day

Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

) and control over a significant portion of the

Mediterranean Basin, the Ottoman Empire was at the centre of interactions between the

Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

and Europe for six centuries. Ruling over so many peoples, the empire granted varying levels of autonomy to its many confessional communities, or ''

millets

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most millets belong to the tribe Paniceae.

Millets are important crops in the semiarid tropics ...

'', to manage their own affairs per

Islamic law

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' refers to immutable, intan ...

. During the reigns of

Selim I

Selim I (; ; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute (), was the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite lasting only eight years, his reign is ...

and

Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I (; , ; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the Western world and as Suleiman the Lawgiver () in his own realm, was the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman sultan between 1520 a ...

, the Ottoman Empire became a

global power.

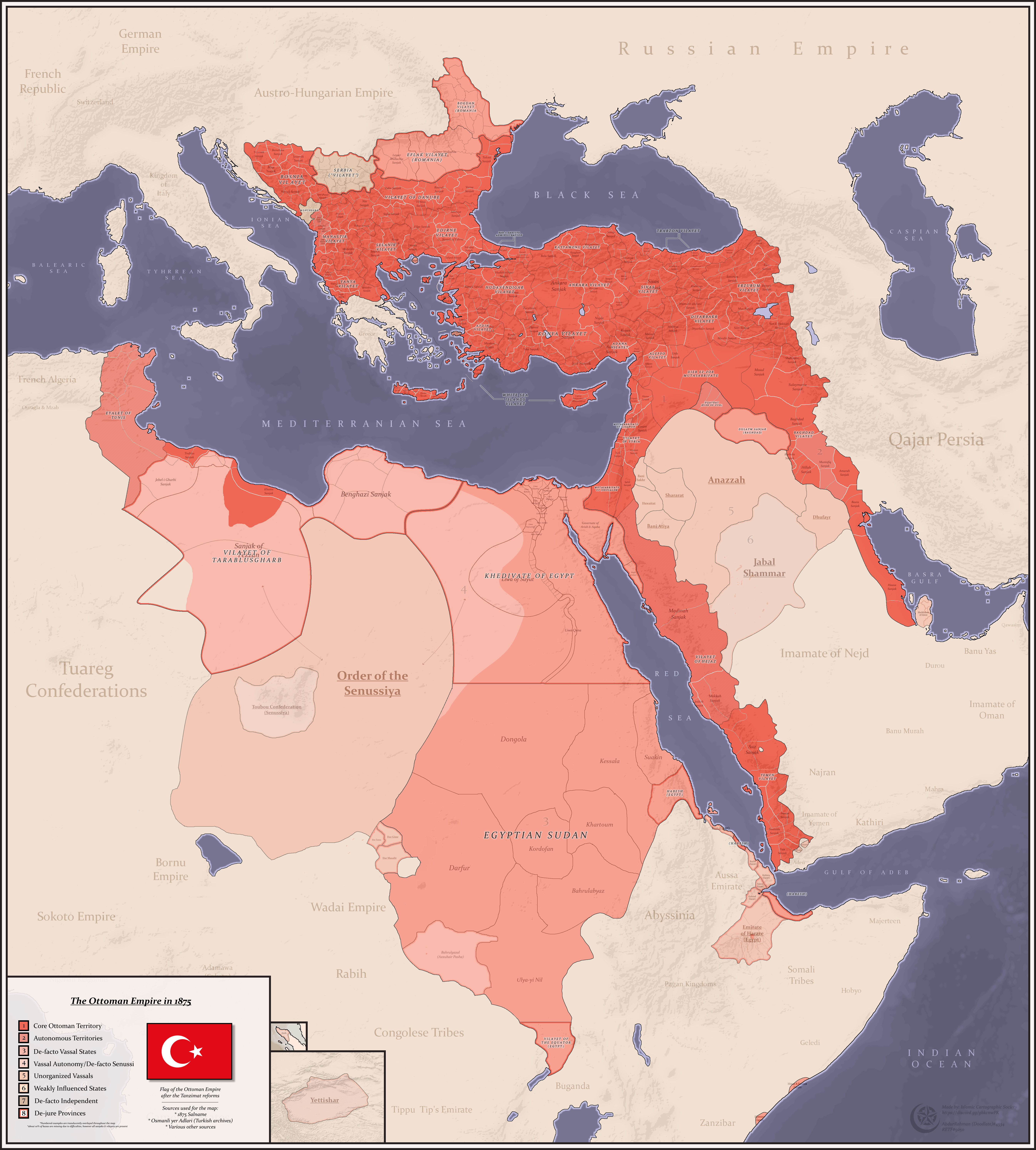

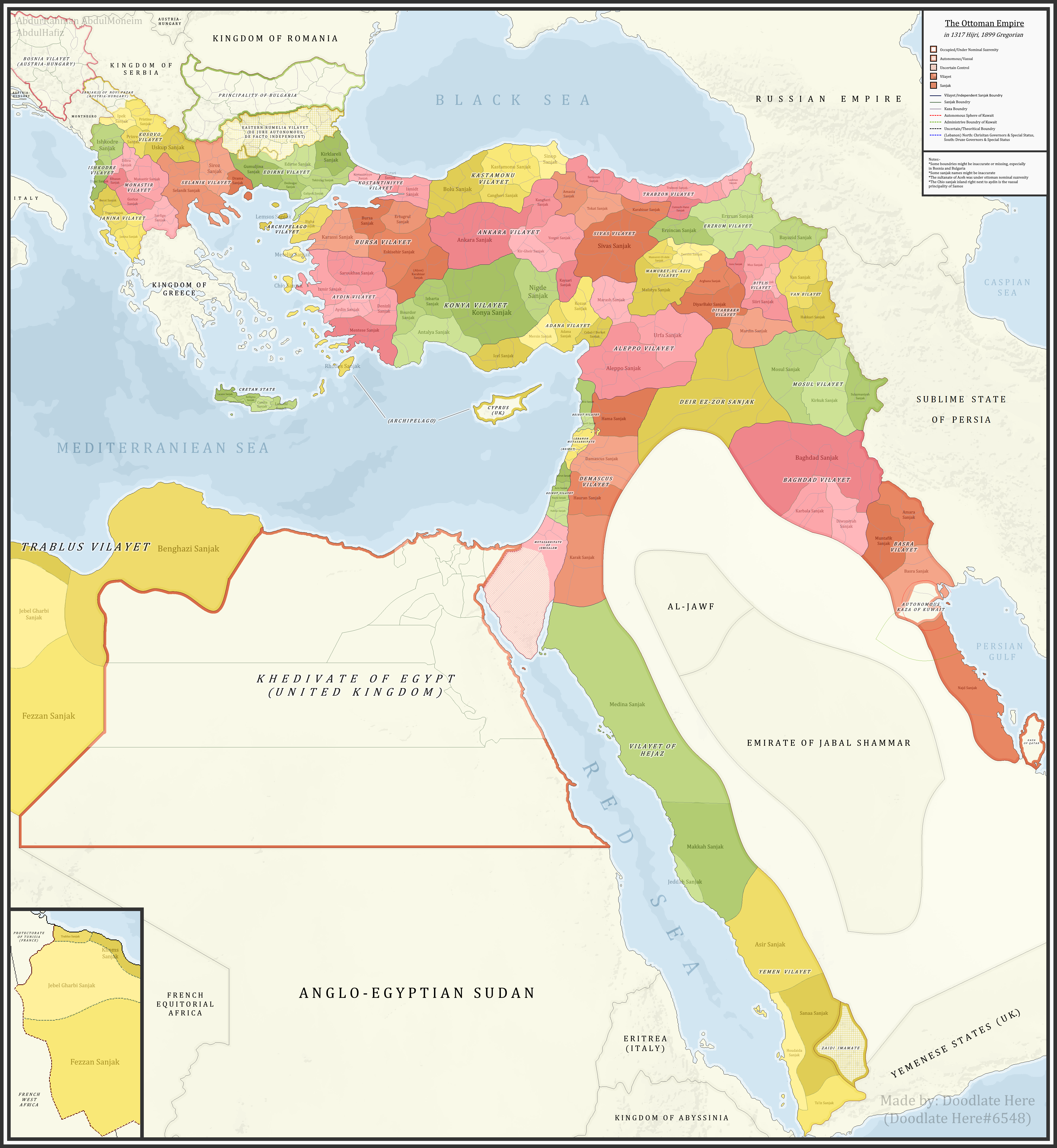

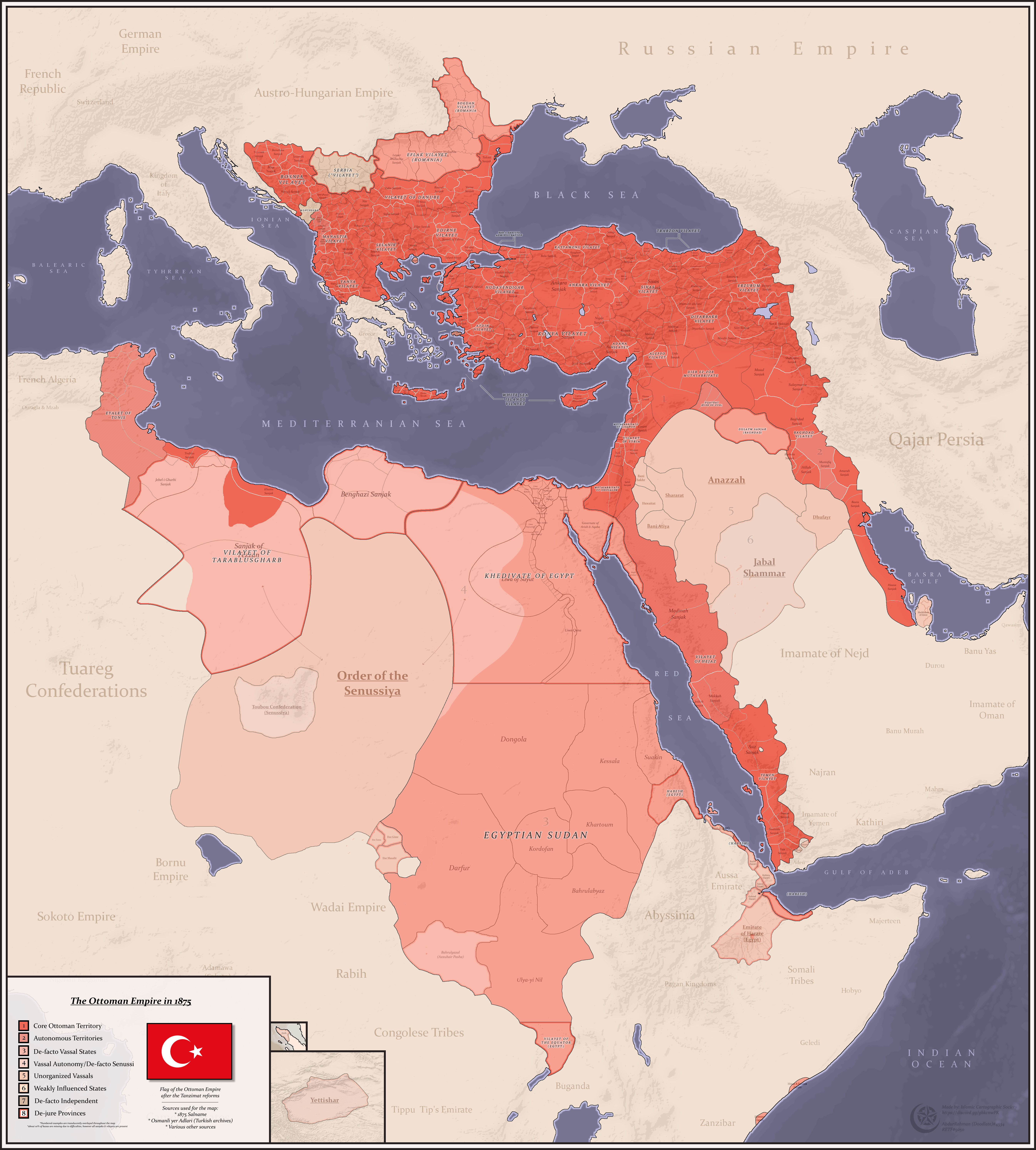

While the Ottoman Empire was once thought to have entered a

period of decline after the death of Suleiman the Magnificent, modern academic consensus posits that the empire continued to maintain a flexible and strong economy, society and military into much of the 18th century. The Ottomans suffered military defeats in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, culminating in the

loss of territory. With

rising nationalism, a number of new states emerged in the Balkans. Following reforms over the course of the 19th century, the Ottoman state became more powerful and organized internally. In the

1876 revolution, the Ottoman Empire attempted

constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

, before reverting to a royalist dictatorship under

Abdul Hamid II

Abdulhamid II or Abdul Hamid II (; ; 21 September 184210 February 1918) was the 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1876 to 1909, and the last sultan to exert effective control over the fracturing state. He oversaw a Decline and modernizati ...

, following the

Great Eastern Crisis

The Great Eastern Crisis of 1875–1878 began in the Ottoman Empire's Rumelia, administrative territories in the Balkan Peninsula in 1875, with the outbreak of several uprisings and wars that resulted in the intervention of international powers, ...

.

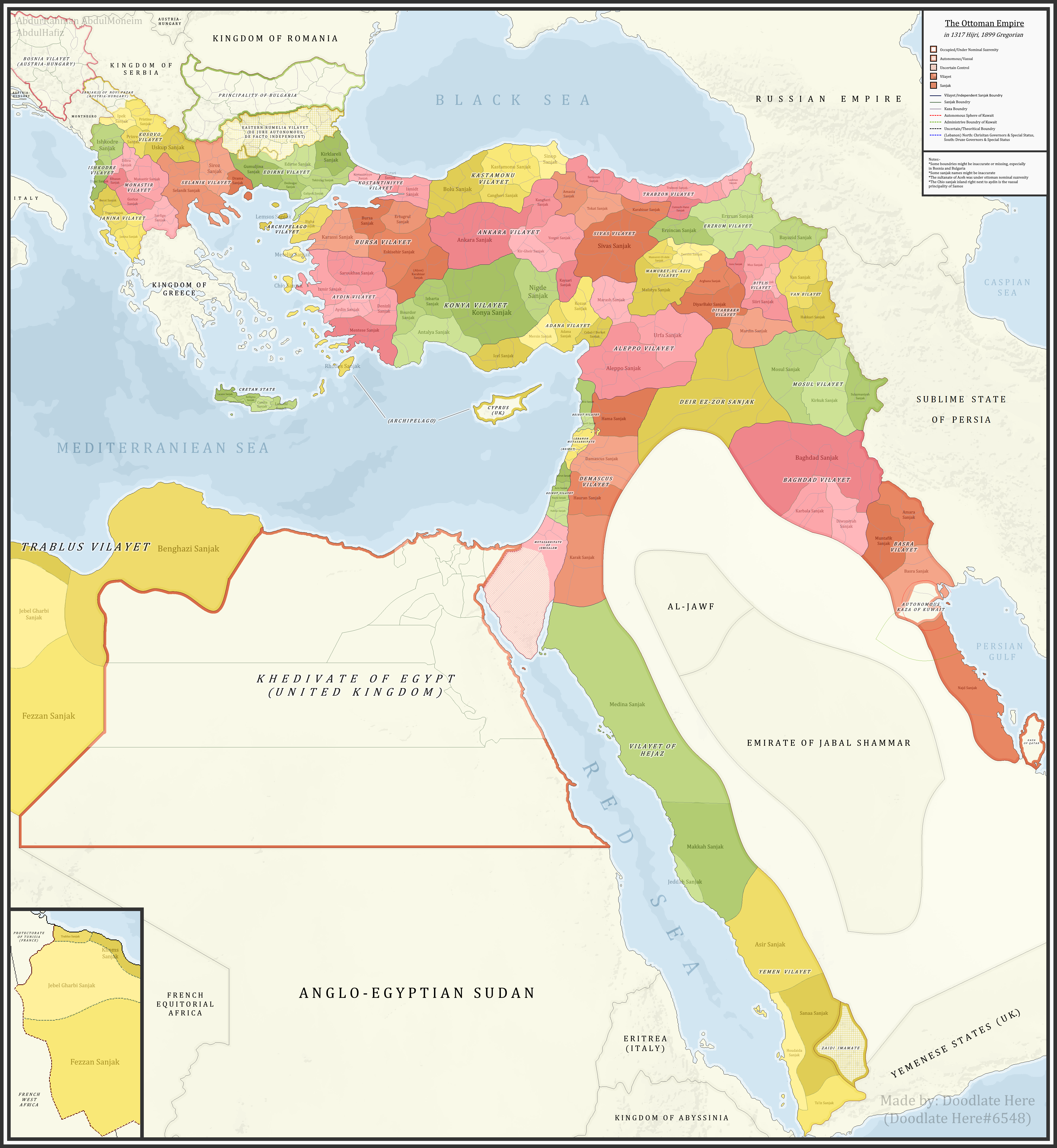

Over the course of the late 19th century, Ottoman intellectuals known as

Young Turks

The Young Turks (, also ''Genç Türkler'') formed as a constitutionalist broad opposition-movement in the late Ottoman Empire against the absolutist régime of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (). The most powerful organization of the movement, ...

sought to liberalize and rationalize society and politics along Western lines, culminating in the

Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908; ) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. Revolutionaries belonging to the Internal Committee of Union and Progress, an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II ...

of 1908 led by the

Committee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

(CUP), which reestablished

a constitutional monarchy. However, following the disastrous

Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

, the CUP became increasingly radicalized and nationalistic,

leading a coup d'état in 1913 that established a dictatorship.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries,

persecution of Muslims during the Ottoman contraction and

in the Russian Empire resulted in large-scale loss of life and

mass migration into modern-day Turkey from the

Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

,

Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

, and

Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

. The CUP joined

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

on the side of the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

. It struggled with internal dissent, especially the

Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ), also known as the Great Arab Revolt ( ), was an armed uprising by the Hashemite-led Arabs of the Hejaz against the Ottoman Empire amidst the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I.

On the basis of the McMahon–Hussein Co ...

, and engaged in

genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

against

Armenians

Armenians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the Armenian highlands of West Asia.Robert Hewsen, Hewsen, Robert H. "The Geography of Armenia" in ''The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiq ...

,

Assyrians

Assyrians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to Mesopotamia, a geographical region in West Asia. Modern Assyrians share descent directly from the ancient Assyrians, one of the key civilizations of Mesopotamia. While they are distinct from ot ...

, and

Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

. In the

aftermath of World War I

The aftermath of World War I saw far-reaching and wide-ranging cultural, economic, and social change across Europe, Asia, Africa, and in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were a ...

, the victorious

Allied Powers occupied and

partitioned the Ottoman Empire, which lost its southern territories to the

United Kingdom and France. The successful

Turkish War of Independence

, strength1 = May 1919: 35,000November 1920: 86,000Turkish General Staff, ''Türk İstiklal Harbinde Batı Cephesi'', Edition II, Part 2, Ankara 1999, p. 225August 1922: 271,000Celâl Erikan, Rıdvan Akın: ''Kurtuluş Savaşı tarih ...

, led by

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish field marshal and revolutionary statesman who was the founding father of the Republic of Turkey, serving as its first President of Turkey, president from 1923 until Death an ...

against the occupying Allies, led to the emergence of the

Republic of Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

and the

abolition of the sultanate in 1922.

Etymology

The word ''Ottoman'' is a historical

anglicisation

Anglicisation or anglicization is a form of cultural assimilation whereby something non-English becomes assimilated into or influenced by the culture of England. It can be sociocultural, in which a non-English place adopts the English language ...

of the name of

Osman I

Osman I or Osman Ghazi (; or ''Osman Gazi''; died 1323/4) was the eponymous founder of the Ottoman Empire (first known as a bey, beylik or emirate). While initially a small Turkoman (ethnonym), Turkoman principality during Osman's lifetime, h ...

, the founder of the Empire and of the ruling

House of Osman (also known as the Ottoman dynasty). Osman's name in turn was the Turkish form of the Arabic name (). In

Ottoman Turkish

Ottoman Turkish (, ; ) was the standardized register of the Turkish language in the Ottoman Empire (14th to 20th centuries CE). It borrowed extensively, in all aspects, from Arabic and Persian. It was written in the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. ...

, the empire was referred to as (), , or simply (), .

The Turkish word for "Ottoman" () originally referred to the tribal followers of Osman in the fourteenth century. The word subsequently came to be used to refer to the empire's military-administrative elite. In contrast, the term "Turk" () was used to refer to the Anatolian peasant and tribal population and was seen as a disparaging term when applied to urban, educated individuals. In the

early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

, an educated, urban-dwelling Turkish speaker who was not a member of the military-administrative class typically referred to themselves neither as an nor as a , but rather as a (), or "Roman", meaning an inhabitant of the territory of the former

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

in the Balkans and Anatolia. The term was also used to refer to Turkish speakers by the other Muslim peoples of the empire and beyond.

In Western Europe, the names Ottoman Empire, Turkish Empire and Turkey were often used interchangeably, with Turkey being increasingly favoured both in formal and informal situations. This dichotomy was officially ended in 1920–1923, when the newly established

Ankara

Ankara is the capital city of Turkey and List of national capitals by area, the largest capital by area in the world. Located in the Central Anatolia Region, central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5,290,822 in its urban center ( ...

-based

Turkish government chose Turkey as the sole official name. At present, most scholarly historians avoid the terms "Turkey", "Turks", and "Turkish" when referring to the Ottomans, due to the empire's multinational character.

History

Rise (c. 1299–1453)

As the

Rum Sultanate declined in the 13th century,

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

was divided into a patchwork of independent Turkish principalities known as the

Anatolian Beyliks

Anatolian beyliks (, Ottoman Turkish: ''Tavâif-i mülûk'', ''Beylik''; ) were Turkish principalities (or petty kingdoms) in Anatolia governed by ''beys'', the first of which were founded at the end of the 11th century. A second and more exte ...

. One of these, in the region of

Bithynia

Bithynia (; ) was an ancient region, kingdom and Roman province in the northwest of Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), adjoining the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus, and the Black Sea. It bordered Mysia to the southwest, Paphlagonia to the northeast a ...

on the frontier of the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

, was led by the Turkish tribal leader

Osman I

Osman I or Osman Ghazi (; or ''Osman Gazi''; died 1323/4) was the eponymous founder of the Ottoman Empire (first known as a bey, beylik or emirate). While initially a small Turkoman (ethnonym), Turkoman principality during Osman's lifetime, h ...

( 1323/4), a figure of obscure origins from whom the name Ottoman is derived. Osman's early followers consisted of Turkish tribal groups and Byzantine renegades, with many but not all converts to Islam. Osman extended control of his principality by conquering Byzantine towns along the

Sakarya River

The Sakarya (; ; ; ) is the third longest river in Turkey. It runs through the region known in ancient times as Phrygia. It was considered one of the principal rivers of Asia Minor (Anatolia) in Greek classical antiquity, and is mentioned in th ...

. A Byzantine defeat at the

Battle of Bapheus in 1302 contributed to Osman's rise. It is not well understood how the early Ottomans came to dominate their neighbors, due to the lack of sources surviving. The

Ghaza thesis

The Ghaza or Ghazi thesis (from , ''ġazā'', "holy war", or simply "raid") is a since disputed historical paradigm first formulated by Paul Wittek which has been used to interpret the nature of the Ottoman Empire during the earliest period of ...

popular during the 20th century credited their success to rallying religious warriors to fight for them in the name of

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

, but it is no longer generally accepted. No other hypothesis has attracted broad acceptance.

In the century after Osman I, Ottoman rule had begun to extend over Anatolia and the

Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

. The earliest conflicts began during the

Byzantine–Ottoman wars

The Byzantine–Ottoman wars were a series of decisive conflicts between the Byzantine Greeks and Ottoman Turks and their allies that led to the final destruction of the Byzantine Empire and the rise of the Ottoman Empire. The Byzantines, alrea ...

, waged in Anatolia in the late 13th century before entering Europe in the mid-14th century, followed by the

Bulgarian–Ottoman wars

The Bulgarian–Ottoman wars were fought between the kingdoms remaining from the disintegrating Second Bulgarian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire, in the second half of the 14th century. The wars resulted in the collapse and subordination of the ...

and the

Serbian–Ottoman wars in the mid-14th century. Much of this period was characterised by

Ottoman expansion into the Balkans. Osman's son,

Orhan

Orhan Ghazi (; , also spelled Orkhan; died 1362) was the second sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1323/4 to 1362. He was born in Söğüt, as the son of Osman I.

In the early stages of his reign, Orhan focused his energies on conquering mos ...

, captured the northwestern Anatolian city of

Bursa

Bursa () is a city in northwestern Turkey and the administrative center of Bursa Province. The fourth-most populous city in Turkey and second-most populous in the Marmara Region, Bursa is one of the industrial centers of the country. Most of ...

in 1326, making it the new capital and supplanting Byzantine control in the region. The important port of

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

was captured from the

Venetians in 1387 and sacked. The Ottoman victory in

Kosovo in 1389 effectively marked the

end of Serbian power in the region, paving the way for Ottoman expansion into Europe. The

Battle of Nicopolis

The Battle of Nicopolis took place on 25 September 1396 and resulted in the rout of an allied Crusader army (assisted by the Venetian navy) at the hands of an Ottoman force, raising the siege of the Danubian fortress of Nicopolis and le ...

for the

Bulgarian Tsardom of Vidin in 1396, regarded as the last large-scale

crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

of the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, failed to stop the advance of the victorious Ottomans.

As the Turks expanded into the Balkans, the

conquest of Constantinople became a crucial objective. The Ottomans had already wrested control of nearly all former Byzantine lands surrounding the city, but the strong defense of Constantinople's strategic position on the

Bosporus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

Strait made it difficult to conquer. In 1402, the Byzantines were temporarily relieved when the

Turco-Mongol

The Turco-Mongol or Turko-Mongol tradition was an ethnocultural synthesis that arose in Asia during the 14th century among the ruling elites of the Golden Horde and the Chagatai Khanate. The ruling Mongol elites of these khanates eventually ass ...

leader

Timur

Timur, also known as Tamerlane (1320s17/18 February 1405), was a Turco-Mongol conqueror who founded the Timurid Empire in and around modern-day Afghanistan, Iran, and Central Asia, becoming the first ruler of the Timurid dynasty. An undefeat ...

, founder of the

Timurid Empire

The Timurid Empire was a late medieval, culturally Persianate, Turco-Mongol empire that dominated Greater Iran in the early 15th century, comprising modern-day Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, much of Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and parts of co ...

, invaded Ottoman Anatolia from the east. In the

Battle of Ankara in 1402, Timur defeated Ottoman forces and took Sultan

Bayezid I

Bayezid I (; ), also known as Bayezid the Thunderbolt (; ; – 8 March 1403), was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1389 to 1402. He adopted the title of ''Sultan-i Rûm'', ''Rûm'' being the Arabic name for the Eastern Roman Empire. In 139 ...

as prisoner, throwing the empire into disorder. The

ensuing civil war lasted from 1402 to 1413 as Bayezid's sons fought over succession. It ended when

Mehmed I

Mehmed I (; – 26 May 1421), also known as Mehmed Çelebi (, "the noble-born") or ''Kirişçi'' (, "lord's son"), was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1413 to 1421. Son of Sultan Bayezid I and his concubine Devlet Hatun, he fought with hi ...

emerged as the sultan and restored Ottoman power.

The Balkan territories lost by the Ottomans after 1402, including Thessaloniki, Macedonia, and Kosovo, were later recovered by

Murad II

Murad II (, ; June 1404 – 3 February 1451) was twice the sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1421 to 1444 and from 1446 to 1451.

Early life

Murad was born in June 1404 to Mehmed I, while the identity of his mother is disputed according to v ...

between the 1430s and 1450s. On 10 November 1444, Murad repelled the

Crusade of Varna

The Crusade of Varna was an unsuccessful military campaign mounted by several European leaders to check the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Central Europe, specifically the Balkans between 1443 and 1444. It was called by Pope Eugene IV ...

by defeating the Hungarian, Polish, and

Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ; : , : ) is a historical and geographical region of modern-day Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians. Wallachia was traditionally divided into two sections, Munteni ...

n armies under

Władysław III of Poland

Władysław III of Poland (31 October 1424 – 10 November 1444), also known as Ladislaus of Varna, was King of Poland and Union of Horodło, Supreme Duke of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from 1434 as well as King of Hungary and List of duk ...

and

John Hunyadi

John Hunyadi (; ; ; ; ; – 11 August 1456) was a leading Kingdom of Hungary, Hungarian military and political figure during the 15th century, who served as Regent of Hungary, regent of the Kingdom of Hungary (1301–1526), Kingdom of Hungary ...

at the

Battle of Varna, although Albanians under

Skanderbeg

Gjergj Kastrioti (17 January 1468), commonly known as Skanderbeg, was an Albanians, Albanian Albanian nobility, feudal lord and military commander who led Skanderbeg's rebellion, a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire in what is today Albania, ...

continued to resist. Four years later, John Hunyadi prepared another army of Hungarian and Wallachian forces to attack the Turks, but was again defeated at the

Second Battle of Kosovo in 1448.

According to modern historiography, there is a direct connection between the rapid Ottoman military advance and the consequences of the

Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

from the mid-fourteenth century onwards. Byzantine territories, where the initial Ottoman conquests were carried out, were exhausted demographically and militarily due to the plague, which facilitated Ottoman expansion. In addition, slave hunting was the main economic driving force behind Ottoman conquest. Some 21st-century authors re-periodize conquest of the Balkans into the ''akıncı phase'', which spanned 8 to 13 decades, characterized by continuous slave hunting and destruction, followed by administrative integration into the Empire.

Expansion and peak (1453–1566)

The son of Murad II,

Mehmed the Conqueror

Mehmed II (; , ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror (; ), was twice the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from August 1444 to September 1446 and then later from February 1451 to May 1481.

In Mehmed II's first reign, ...

, reorganized both state and military, and on 29 May 1453 conquered

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, ending the Byzantine Empire.

Mehmed allowed the

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, and also called the Greek Orthodox Church or simply the Orthodox Church, is List of Christian denominations by number of members, one of the three major doctrinal and ...

to maintain its autonomy and land in exchange for accepting Ottoman authority.

Due to tension between the states of western Europe and the later Byzantine Empire, most of the Orthodox population accepted Ottoman rule, as preferable to Venetian rule.

was a major obstacle to Ottoman expansion on the Italian peninsula.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ottoman Empire entered a

period of expansion. The Empire prospered under the rule of a line of committed and effective

Sultans

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

. It flourished economically due to its control of the major overland trade routes between Europe and Asia.

Sultan

Selim I

Selim I (; ; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute (), was the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite lasting only eight years, his reign is ...

(1512–1520) dramatically expanded the eastern and southern frontiers by defeating

Shah Ismail of

Safavid Iran

The Guarded Domains of Iran, commonly called Safavid Iran, Safavid Persia or the Safavid Empire, was one of the largest and longest-lasting Iranian empires. It was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often considered the begi ...

, in the

Battle of Chaldiran

The Battle of Chaldiran (; ) took place on 23 August 1514 and ended with a decisive victory for the Ottoman Empire over the Safavid Empire. As a result, the Ottomans annexed Eastern Anatolia and Upper Mesopotamia from Safavid Iran. It marked ...

. Selim I established

Ottoman rule in Egypt by defeating and annexing the

Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt and created a naval presence on the

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

. After this Ottoman expansion, competition began between the

Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire was a colonial empire that existed between 1415 and 1999. In conjunction with the Spanish Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It achieved a global scale, controlling vast portions of the Americas, Africa ...

and the Ottomans to become the dominant power in the region.

Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I (; , ; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the Western world and as Suleiman the Lawgiver () in his own realm, was the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman sultan between 1520 a ...

(1520–1566) captured

Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

in 1521, conquered the southern and central parts of the

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

as part of the

Ottoman–Hungarian Wars, and, after his historic victory in the

Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; , ) took place on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, in the Kingdom of Hungary. It was fought between the forces of Hungary, led by King Louis II of Hungary, Louis II, and the invading Ottoman Empire, commanded by Suleima ...

in 1526, he established Ottoman rule in the territory of present-day Hungary and other Central European territories. He then laid

siege to Vienna in 1529, but failed to take the city. In 1532, he made another

attack on Vienna, but was repulsed in the

siege of Güns.

Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

, Wallachia and, intermittently,

Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

, became tributary principalities of the Empire. In the east, the Ottoman Turks took

Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

from the Persians in 1535, gaining control of

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

and naval access to the

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

. After the end of the

Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–1555), the

Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

became partitioned for the first time between the Safavids and the Ottomans, a ''

status quo

is a Latin phrase meaning the existing state of affairs, particularly with regard to social, economic, legal, environmental, political, religious, scientific or military issues. In the sociological sense, the ''status quo'' refers to the curren ...

'' that persisted until the

Russian conquest of the Caucasus

The Russian conquest of the Caucasus mainly occurred between 1800 and 1864. The Russian Empire sought to control the region between the Black Sea and Caspian Sea. South of the mountains was the territory that is modern Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georg ...

in the 19th century. By this partitioning as signed in the

Peace of Amasya

The Peace of Amasya (; ) was a treaty agreed to on May 29, 1555, between Shah Tahmasp I of Safavid Iran and Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent of the Ottoman Empire at the city of Amasya, following the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–1555), Ottoman� ...

,

Western Armenia

Western Armenia (Western Armenian: Արեւմտեան Հայաստան, ''Arevmdian Hayasdan'') is a term to refer to the western parts of the Armenian highlands located within Turkey (formerly the Ottoman Empire) that comprise the historic ...

, western

Kurdistan

Kurdistan (, ; ), or Greater Kurdistan, is a roughly defined geo- cultural region in West Asia wherein the Kurds form a prominent majority population and the Kurdish culture, languages, and national identity have historically been based. G ...

, and

Western Georgia fell into Ottoman hands, while southern

Dagestan

Dagestan ( ; ; ), officially the Republic of Dagestan, is a republic of Russia situated in the North Caucasus of Eastern Europe, along the Caspian Sea. It is located north of the Greater Caucasus, and is a part of the North Caucasian Fede ...

,

Eastern Armenia,

Eastern Georgia, and

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan, officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, is a Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental and landlocked country at the boundary of West Asia and Eastern Europe. It is a part of the South Caucasus region and is bounded by ...

remained Persian.

In 1539, a 60,000-strong Ottoman army besieged the

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

garrison of

Castelnuovo on the

Adriatic coast

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to ...

; the successful siege cost the Ottomans 8,000 casualties, but

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

agreed to terms in 1540, surrendering most of its empire in the

Aegean and the

Morea

Morea ( or ) was the name of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The name was used by the Principality of Achaea, the Byzantine province known as the Despotate of the Morea, by the O ...

.

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and the Ottoman Empire, united by mutual opposition to

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

rule,

became allies. The French conquests of

Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one million[Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...]

(1553) occurred as a joint venture between French king

Francis I and Suleiman, and were commanded by the Ottoman admirals

Hayreddin Barbarossa

Hayreddin Barbarossa (, original name: Khiḍr; ), also known as Hayreddin Pasha, Hızır Hayrettin Pasha, and simply Hızır Reis (c. 1466/1483 – 4 July 1546), was an Ottoman corsair and later admiral of the Ottoman Navy. Barbarossa's ...

and

Dragut

Dragut (; 1485 – 23 June 1565) was an Ottoman corsair, naval commander, governor, and noble. Under his command, the Ottoman Empire's maritime power was extended across North Africa. Recognized for his military genius, and as being among "the ...

. France supported the Ottomans with an artillery unit during the 1543 Ottoman

conquest of Esztergom in northern Hungary. After further advances by the Turks, the Habsburg ruler

Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "courage" or "ready, prepared" related to Old High German "to risk, ventu ...

officially recognized Ottoman ascendancy in Hungary in 1547. Suleiman died of natural causes during the

siege of Szigetvár

The siege of Szigetvár or the Battle of Szigeth (pronunciation: �siɡɛtvaːr ; ; ) was an Ottoman siege of the fortress of Szigetvár in the Kingdom of Hungary. The fort had blocked Sultan Suleiman's line of advance towards Vienna in 156 ...

in 1566. Following his death, the Ottomans were said to be declining, although this has been rejected by many scholars.

[; ; ] By the end of Suleiman's reign, the Empire spanned approximately , extending over three continents.

The Empire became a dominant naval force, controlling much of the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

. The Empire was now a major part of European politics. The Ottomans became involved in multi-continental religious wars when Spain and Portugal were united under the

Iberian Union

The Iberian Union is a historiographical term used to describe the period in which the Habsburg Spain, Monarchy of Spain under Habsburg dynasty, until then the personal union of the crowns of Crown of Castile, Castile and Crown of Aragon, Aragon ...

. The Ottomans were holders of the Caliph title, meaning they were the leaders of Muslims worldwide. The Iberians were leaders of the Christian crusaders, and so the two fought in a worldwide conflict. There were zones of operations in the Mediterranean and

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

, where Iberians circumnavigated Africa to reach India and, on their way, wage war upon the Ottomans and their local Muslim allies. Likewise, the Iberians passed through newly-Christianized

Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

and

had sent expeditions that traversed the Pacific to Christianize the formerly Muslim Philippines and use it as a base to attack the Muslims in the

Far East

The Far East is the geographical region that encompasses the easternmost portion of the Asian continent, including North Asia, North, East Asia, East and Southeast Asia. South Asia is sometimes also included in the definition of the term. In mod ...

. In this case, the Ottomans

sent armies to aid its easternmost vassal and territory, the

Sultanate of Aceh

The Sultanate of Aceh, officially the Kingdom of Aceh Darussalam (; Jawoë: ), was a sultanate centered in the modern-day Indonesian province of Aceh. It was a major regional power in the 16th and 17th centuries, before experiencing a long per ...

in Southeast Asia.

The

Spanish–Ottoman wars

The Spanish–Ottoman wars were a series of wars fought between the Ottoman Empire and the Spanish Empire for Mediterranean and overseas sphere of influence, influence, and specially for global religious dominance between the Catholic Church and ...

took place primarily in the Mediterranean.

Barbary corsairs

The Barbary corsairs, Barbary pirates, Ottoman corsairs, or naval mujahideen (in Muslim sources) were mainly Muslim corsairs and privateers who operated from the largely independent Barbary states. This area was known in Europe as the Barba ...

from the North African cities of Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, which were nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, captured thousands of merchant ships and raided coastal towns in Europe,

enslaving the people they captured.

[Review of ''Pirates of Barbary'']

by Ian W. Toll, ''The New York Times,'' 12 December 2010

During the 1600s, the world conflict between the Ottoman Caliphate and Iberian Union was a stalemate since

both were at similar population, technology and economic levels. Nevertheless, the success of the Ottoman political and military establishment was compared to the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, despite the difference in size, by the likes of contemporary Italian scholar

Francesco Sansovino and French political philosopher

Jean Bodin

Jean Bodin (; ; – 1596) was a French jurist and political philosopher, member of the Parlement of Paris and professor of law in Toulouse. Bodin lived during the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation and wrote against the background of reli ...

.

Stagnation and reform (1566–1827)

Revolts, reversals, and revivals (1566–1683)

In the second half of the sixteenth century, the Ottoman Empire came under increasing strain from inflation and the rapidly rising costs of warfare that were impacting both Europe and the Middle East. These pressures led to a series of crises around the year 1600, placing great strain upon the Ottoman system of government. The empire underwent a series of transformations of its political and military institutions in response to these challenges, enabling it to successfully adapt to the new conditions of the seventeenth century and remain powerful, both militarily and economically.

[ Historians of the mid-twentieth century once characterised this period as one of stagnation and decline, but this view is now rejected by the majority of academics.][

The discovery of new maritime trade routes by Western European states allowed them to avoid the Ottoman trade monopoly. The Portuguese discovery of the ]Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

in 1488 initiated a series of Ottoman-Portuguese naval wars in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

throughout the 16th century. Despite the growing European presence in the Indian Ocean, Ottoman trade with the east continued to flourish. Cairo, in particular, benefitted from the rise of Yemeni coffee as a popular consumer commodity. As coffeehouses appeared in cities and towns across the empire, Cairo developed into a major center for its trade, contributing to its continued prosperity throughout the seventeenth and much of the eighteenth century.

Under Ivan IV (1533–1584), the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia, also known as the Tsardom of Moscow, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of tsar by Ivan the Terrible, Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter the Great in 1721.

...

expanded into the Volga and Caspian regions at the expense of the Tatar khanate

A khanate ( ) or khaganate refers to historic polity, polities ruled by a Khan (title), khan, khagan, khatun, or khanum. Khanates were typically nomadic Mongol and Turkic peoples, Turkic or Tatars, Tatar societies located on the Eurasian Steppe, ...

s. In 1571, the Crimean khan Devlet I Giray, commanded by the Ottomans, invaded Russia and burned Moscow.slave raids

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

,Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, and Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

.

The Ottomans decided to conquer Venetian Cyprus and on 22 July 1570, Nicosia was besieged; 50,000 Christians died, and 180,000 were enslaved. On 15 September 1570, the Ottoman cavalry appeared before the last Venetian stronghold in Cyprus, Famagusta. The Venetian defenders held out for 11 months against a force that at its peak numbered 200,000 men with 145 cannons; 163,000 cannonballs struck the walls of Famagusta before it fell to the Ottomans in August 1571. The Siege of Famagusta claimed 50,000 Ottoman casualties. Meanwhile, the Holy League consisting of mostly Spanish and Venetian fleets won a victory over the Ottoman fleet at the

The Ottomans decided to conquer Venetian Cyprus and on 22 July 1570, Nicosia was besieged; 50,000 Christians died, and 180,000 were enslaved. On 15 September 1570, the Ottoman cavalry appeared before the last Venetian stronghold in Cyprus, Famagusta. The Venetian defenders held out for 11 months against a force that at its peak numbered 200,000 men with 145 cannons; 163,000 cannonballs struck the walls of Famagusta before it fell to the Ottomans in August 1571. The Siege of Famagusta claimed 50,000 Ottoman casualties. Meanwhile, the Holy League consisting of mostly Spanish and Venetian fleets won a victory over the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval warfare, naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League (1571), Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states arranged by Pope Pius V, inflicted a major defeat on the fleet of t ...

(1571), off southwestern Greece; Catholic forces killed over 30,000 Turks and destroyed 200 of their ships. It was a startling, if mostly symbolic, blow to the image of Ottoman invincibility, an image which the victory of the Knights of Malta

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), officially the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta, and commonly known as the Order of Malta or the Knights of Malta, is a Catholic Church, Cathol ...

over the Ottoman invaders in the 1565 siege of Malta had recently set about eroding. The battle was far more damaging to the Ottoman navy in sapping experienced manpower than the loss of ships, which were rapidly replaced. The Ottoman navy recovered quickly, persuading Venice to sign a peace treaty in 1573, allowing the Ottomans to expand and consolidate their position in North Africa.

By contrast, the Habsburg frontier had settled somewhat, a stalemate caused by a stiffening of the Habsburg defenses. The Long Turkish War

The Long Turkish War (, ), Long War (; , ), or Thirteen Years' War was an indecisive land war between the Holy Roman Empire (primarily the Habsburg monarchy) and the Ottoman Empire, primarily over the principalities of Wallachia, Transylvania, ...

against Habsburg Austria (1593–1606) created the need for greater numbers of Ottoman infantry equipped with firearms, resulting in a relaxation of recruitment policy. This contributed to problems of indiscipline and outright rebelliousness within the corps, which were never fully solved. Irregular sharpshooters ( Sekban) were also recruited, and on demobilisation turned to brigandage

Brigandage is the life and practice of highway robbery and plunder. It is practiced by a brigand, a person who is typically part of a gang and lives by pillage and robbery.Oxford English Dictionary second edition, 1989. "Brigand.2" first recorded ...

in the Celali rebellions (1590–1610), which engendered widespread anarchy in Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. With the Empire's population reaching 30 million people by 1600, the shortage of land placed further pressure on the government. In spite of these problems, the Ottoman state remained strong, and its army did not collapse or suffer crushing defeats. The only exceptions were campaigns against the Safavid dynasty

The Safavid dynasty (; , ) was one of Iran's most significant ruling dynasties reigning from Safavid Iran, 1501 to 1736. Their rule is often considered the beginning of History of Iran, modern Iranian history, as well as one of the gunpowder em ...

of Persia, where many of the Ottoman eastern provinces were lost, some permanently. This 1603–1618 war eventually resulted in the Treaty of Nasuh Pasha, which ceded the entire Caucasus, except westernmost Georgia, back into the possession of Safavid Iran

The Guarded Domains of Iran, commonly called Safavid Iran, Safavid Persia or the Safavid Empire, was one of the largest and longest-lasting Iranian empires. It was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often considered the begi ...

. The treaty ending the Cretan War cost Venice much of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

, its Aegean island possessions, and Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

.

During his brief majority reign, Murad IV

Murad IV (, ''Murād-ı Rābiʿ''; , 27 July 1612 – 8 February 1640) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1623 to 1640, known both for restoring the authority of the state and for the brutality of his methods. Murad I ...

(1623–1640) reasserted central authority and recaptured Iraq (1639) from the Safavids. The resulting Treaty of Zuhab

The Treaty of Zuhab (, ''Ahadnāmah Zuhab''), also called Treaty of Qasr-e Shirin (), signed on May 17, 1639, ended the Ottoman-Safavid War of 1623–1639. It confirmed territorial divisions in West Asia, shaping the borders between the Safavid an ...

of that same year decisively divided the Caucasus and adjacent regions between the two neighbouring empires as it had already been defined in the 1555 Peace of Amasya.

The Sultanate of Women (1533–1656) was a period in which the mothers of young sultans exercised power on behalf of their sons. The most prominent women of this period were Kösem Sultan

Kösem Sultan (; 1589 – 2 September 1651), also known as Mahpeyker Sultan (;), was the Haseki sultan, Haseki Sultan as the chief consort and legal wife of the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Sultan Ahmed I, Valide sultan, Vali ...

and her daughter-in-law Turhan Hatice, whose political rivalry culminated in Kösem's murder in 1651. During the Köprülü era

The Köprülü era () (c. 1656–1703) was a period in which the Ottoman Empire's politics were frequently dominated by a series of grand viziers from the Köprülü family. The Köprülü era is sometimes more narrowly defined as the period fr ...

(1656–1703), effective control of the Empire was exercised by a sequence of grand vizier

Grand vizier (; ; ) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. It was first held by officials in the later Abbasid Caliphate. It was then held in the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Soko ...

s from the Köprülü family. The Köprülü Vizierate saw renewed military success with authority restored in Transylvania, the conquest of Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

completed in 1669, and expansion into Polish southern Ukraine, with the strongholds of Khotyn

Khotyn (, ; , ; see #Name, other names) is a List of cities in Ukraine, city in Dnistrovskyi Raion, Chernivtsi Oblast of western Ukraine, located south-west of Kamianets-Podilskyi. It hosts the administration of Khotyn urban hromada, one of th ...

, and Kamianets-Podilskyi

Kamianets-Podilskyi (, ; ) is a city on the Smotrych River in western Ukraine, western Ukraine, to the north-east of Chernivtsi. Formerly the administrative center of Khmelnytskyi Oblast, the city is now the administrative center of Kamianets ...

and the territory of Podolia

Podolia or Podillia is a historic region in Eastern Europe located in the west-central and southwestern parts of Ukraine and northeastern Moldova (i.e. northern Transnistria).

Podolia is bordered by the Dniester River and Boh River. It features ...

ceding to Ottoman control in 1676.

This period of renewed assertiveness came to a calamitous end in 1683 when Grand Vizier

This period of renewed assertiveness came to a calamitous end in 1683 when Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha

Kara Mustafa Pasha (; ; "Mustafa Pasha the Courageous"; 1634/1635 – 25 December 1683) was an Ottoman nobleman, military figure and Grand Vizier, who was a central character in the Ottoman Empire's last attempts at expansion into both Centr ...

led a huge army to attempt a second Ottoman siege of Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

in the Great Turkish War

The Great Turkish War () or The Last Crusade, also called in Ottoman sources The Disaster Years (), was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League (1684), Holy League consisting of the Holy Roman Empire, Polish–Lith ...

of 1683–1699. The final assault being fatally delayed, the Ottoman forces were swept away by allied Habsburg, German, and Polish forces spearheaded by the Polish king John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( (); (); () 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobieski was educated at the Jagiellonian University and toured Eur ...

at the Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mountain near Vienna on 1683 after the city had been besieged by the Ottoman Empire for two months. The battle was fought by the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarchy) and the Polish–Li ...

. The alliance of the Holy League pressed home the advantage of the defeat at Vienna, culminating in the Treaty of Karlowitz

The Treaty of Karlowitz, concluding the Great Turkish War of 1683–1699, in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated by the Holy League at the Battle of Zenta, was signed in Karlowitz, in the Military Frontier of the Habsburg Monarchy (present-day ...

(26 January 1699), which ended the Great Turkish War. The Ottomans surrendered control of significant territories, many permanently. Mustafa II

Mustafa II (; ''Muṣṭafā-yi sānī''; 6 February 1664 – 29 December 1703) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1695 to 1703.

Early life

He was born at Edirne Palace on 6 February 1664. He was the son of Sultan Mehmed IV (1648–87 ...

(1695–1703) led the counterattack of 1695–1696 against the Habsburgs in Hungary, but was undone at the disastrous defeat at Zenta (in modern Serbia), 11 September 1697.

Military defeats

Aside from the loss of the Banat

Banat ( , ; ; ; ) is a geographical and Historical regions of Central Europe, historical region located in the Pannonian Basin that straddles Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. It is divided among three countries: the eastern part lie ...

and the temporary loss of Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

(1717–1739), the Ottoman border on the Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

and Sava

The Sava, is a river in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, a right-bank and the longest tributary of the Danube. From its source in Slovenia it flows through Croatia and along its border with Bosnia and Herzegovina, and finally reac ...

remained stable during the eighteenth century. Russian expansion, however, presented a large and growing threat. Accordingly, King Charles XII of Sweden

Charles XII, sometimes Carl XII () or Carolus Rex (17 June 1682 – 30 November 1718 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.), was King of Sweden from 1697 to 1718. He belonged to the House of Palatinate-Zweibrücken, a branch line of the House of ...

was welcomed as an ally in the Ottoman Empire following his defeat by the Russians at the Battle of Poltava

The Battle of Poltava took place 8 July 1709, was the decisive and largest battle of the Great Northern War. The Russian army under the command of Tsar Peter I defeated the Swedish army commanded by Carl Gustaf Rehnskiöld. The battle would l ...

of 1709 in central Ukraine (part of the Great Northern War

In the Great Northern War (1700–1721) a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern Europe, Northern, Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the ant ...

of 1700–1721). Charles XII persuaded the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed III to declare war on Russia, which resulted in an Ottoman victory in the Pruth River Campaign of 1710–1711, in Moldavia.

After the Austro-Turkish War, the

After the Austro-Turkish War, the Treaty of Passarowitz

The Treaty of Passarowitz, or Treaty of Požarevac, was the peace treaty signed in Požarevac ( sr-cyr, Пожаревац, , ), a town that was in the Ottoman Empire but is now in Serbia, on 21 July 1718 between the Ottoman Empire and its ad ...

confirmed the loss of the Banat, Serbia, and "Little Walachia" (Oltenia) to Austria. The Treaty also revealed that the Ottoman Empire was on the defensive and unlikely to present any further aggression in Europe. The Austro-Russian–Turkish War (1735–1739), which was ended by the Treaty of Belgrade in 1739, resulted in the Ottoman recovery of northern Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

, Habsburg Serbia (including Belgrade), Oltenia

Oltenia (), also called Lesser Wallachia in antiquated versions – with the alternative Latin names , , and between 1718 and 1739 – is a historical province and geographical region of Romania in western Wallachia. It is situated between the Da ...

and the southern parts of the Banat of Temeswar

The Banat of Temeswar or Banat of Temes was a Habsburg province that existed between 1718 and 1778. It was located in the present day region of Banat, which was named after this province. The province was abolished in 1778 and the following ...

; but the Empire lost the port of Azov

Azov (, ), previously known as Azak ( Turki/ Kypchak: ),

is a town in Rostov Oblast, Russia, situated on the Don River just from the Sea of Azov, which derives its name from the town. The population is

History

Early settlements in the vici ...

, north of the Crimean Peninsula, to the Russians. After this treaty the Ottoman Empire was able to enjoy a generation of peace in Europe, as Austria and Russia were forced to deal with the rise of Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

.

Educational and technological reforms came about, including the establishment of higher education institutions such as the Istanbul Technical University

Istanbul Technical University, also known as Technical University of Istanbul (, commonly referred to as İTÜ), is an public university, public technical university located in Istanbul, Turkey. It is the world's third-oldest technical university ...

. In 1734 an artillery school was established to impart Western-style artillery methods, but the Islamic clergy successfully objected under the grounds of theodicy

In the philosophy of religion, a theodicy (; meaning 'vindication of God', from Ancient Greek θεός ''theos'', "god" and δίκη ''dikē'', "justice") is an argument that attempts to resolve the problem of evil that arises when all powe ...

.Nevşehirli Damat Ibrahim Pasha

Nevşehirli Damat Ibrahim Pasha ( 1662 – 1 October 1730) served as Grand Vizier for Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Sultan Ahmed III of the Ottoman Empire during the Tulip period. He was also the head of a ruling family which had great influence ...

, the Grand Mufti

A Grand Mufti (also called Chief Mufti, State Mufti and Supreme Mufti) is a title for the leading Faqīh, Islamic jurist of a country, typically Sunni, who may oversee other muftis. Not all countries with large Sunni Muslim populations have Gra ...

, and the clergy on the efficiency of the printing press, and Muteferrika was later granted by Sultan Ahmed III permission to publish non-religious books (despite opposition from some calligraphers and religious leaders).Oran

Oran () is a major coastal city located in the northwest of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria, after the capital, Algiers, because of its population and commercial, industrial and cultural importance. It is w ...

; the siege caused the deaths of 1,500 Spaniards, and even more Algerians. The Spanish also massacred many Muslim soldiers. In 1792, Spain abandoned Oran, selling it to the Deylik of Algiers.

In 1768 Russian-backed Ukrainian Haidamakas, pursuing Polish confederates, entered Balta, an Ottoman-controlled town on the border of Bessarabia in Ukraine, massacred its citizens, and burned the town to the ground. This action provoked the Ottoman Empire into the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774. The

In 1768 Russian-backed Ukrainian Haidamakas, pursuing Polish confederates, entered Balta, an Ottoman-controlled town on the border of Bessarabia in Ukraine, massacred its citizens, and burned the town to the ground. This action provoked the Ottoman Empire into the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774. The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (; ), formerly often written Kuchuk-Kainarji, was a peace treaty signed on , in Küçük Kaynarca (today Kaynardzha, Bulgaria and Cuiugiuc, Romania) between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire, ending the R ...

of 1774 ended the war and provided freedom of worship for the Christian citizens of the Ottoman-controlled provinces of Wallachia and Moldavia. By the late 18th century, after a number of defeats in the wars with Russia, some people in the Ottoman Empire began to conclude that the reforms of Peter the Great

Peter I (, ;

– ), better known as Peter the Great, was the Sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia, Tsar of all Russia from 1682 and the first Emperor of Russia, Emperor of all Russia from 1721 until his death in 1725. He reigned j ...

had given the Russians an edge, and the Ottomans would have to keep up with Western technology in order to avoid further defeats.Selim III

Selim III (; ; was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1789 to 1807. Regarded as an enlightened ruler, he was eventually deposed and imprisoned by the Janissaries, who placed his cousin Mustafa on the throne as Mustafa IV (). A group of a ...

(1789–1807) made the first major attempts to modernise the army, but his reforms were hampered by the religious leadership and the Janissary

A janissary (, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan's household troops. They were the first modern standing army, and perhaps the first infantry force in the world to be equipped with firearms, adopted dur ...

corps. Jealous of their privileges and firmly opposed to change, the Janissary revolted. Selim's efforts cost him his throne and his life, but were resolved in spectacular and bloody fashion by his successor, the dynamic Mahmud II

Mahmud II (, ; 20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839. Often described as the "Peter the Great of Turkey", Mahmud instituted extensive administrative, military, and fiscal reforms ...

, who eliminated the Janissary corps in 1826.

The Serbian revolution

The Serbian Revolution ( / ') was a national uprising and constitutional change in Serbia that took place between 1804 and 1835, during which this territory evolved from an Sanjak of Smederevo, Ottoman province into a Revolutionary Serbia, reb ...

(1804–1815) marked the beginning of an era of national awakening in the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

during the Eastern Question. In 1811, the fundamentalist Wahhabis of Arabia, led by the al-Saud family, revolted against the Ottomans. Unable to defeat the Wahhabi rebels, the Sublime Porte had Muhammad Ali Pasha of Kavala

Kavala (, ''Kavála'' ) is a city in northern Greece, the principal seaport of eastern Macedonia and the capital of Kavala regional unit.

It is situated on the Bay of Kavala, across from the island of Thasos and on the A2 motorway, a one-and ...

, the '' vali'' (governor) of the Eyalet of Egypt

Ottoman Egypt was an administrative division of the Ottoman Empire after the conquest of Mamluk Egypt by the Ottomans in 1517. The Ottomans administered Egypt as a province (''eyalet'') of their empire (). It remained formally an Ottoman pro ...

, tasked with retaking Arabia, which ended with the destruction of the Emirate of Diriyah

The first Saudi state (), officially the Emirate of Diriyah (), was established in 1744, when the emir of a Najdi town called Diriyah, Muhammad I, and the religious leader Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab signed a pact to found a socio-religious ...

in 1818. The suzerainty

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy">polity.html" ;"title="state (polity)">state or polity">state (polity)">st ...

of Serbia as a hereditary monarchy under its own dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family, usually in the context of a monarchy, monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A dynasty may also be referred to as a "house", "family" or "clan", among others.

H ...

was acknowledged ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

'' in 1830.Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

declared war on the Sultan. A rebellion that originated in Moldavia as a diversion was followed by the main revolution in the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

, which, along with the northern part of the Gulf of Corinth, became the first parts of the Ottoman Empire to achieve independence (in 1829). In 1830, the French invaded the Deylik of Algiers. Invasion of Algiers in 1830, The campaign took 21 days, and resulted in over 5,000 Algerian military casualties,[De Quatrebarbes, Théodore (1831). ''Souvenirs de la campagne d'Afrique''. Dentu. p. 35.] and about 2,600 French ones.Mahmud II

Mahmud II (, ; 20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839. Often described as the "Peter the Great of Turkey", Mahmud instituted extensive administrative, military, and fiscal reforms ...

due to the latter's refusal to grant him the governorships of Syria (region), Greater Syria and Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, which the Sultan had promised him in exchange for sending military assistance to put down the Greek War of Independence, Greek revolt (1821–1829) that ultimately ended with the formal London Protocol (1830), independence of Greece in 1830. It was a costly enterprise for Muhammad Ali, who had lost his fleet at the Battle of Navarino in 1827. Thus began the first Egyptian–Ottoman War (1831–1833), during which the French-trained army of Muhammad Ali, under the command of his son Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt, Ibrahim Pasha, defeated the Ottoman Army as it marched into Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, reaching the city of Kütahya within of the capital, Constantinople.Mahmud II

Mahmud II (, ; 20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839. Often described as the "Peter the Great of Turkey", Mahmud instituted extensive administrative, military, and fiscal reforms ...

appealed to the empire's traditional arch-rival Russia for help, asking Emperor Nicholas I of Russia, Nicholas I to send an expeditionary force to assist him.Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, Aleppo, Tripoli, Lebanon, Tripoli, Damascus and Sidon (the latter four comprising modern Syria and Lebanon), and given the right to collect taxes in Adana.Mahmud II

Mahmud II (, ; 20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839. Often described as the "Peter the Great of Turkey", Mahmud instituted extensive administrative, military, and fiscal reforms ...

could have faced the risk of being overthrown and Muhammad Ali could have even become the new Sultan. These events marked the beginning of a recurring pattern where the Sublime Porte needed the help of foreign powers to protect itself.de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

'' still Ottoman Eyalet of Egypt