Mendelssohn on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include

Felix Mendelssohn was born on 3 February 1809, in

Felix Mendelssohn was born on 3 February 1809, in

Mendelssohn probably made his first public concert appearance at the age of nine, when he participated in a

Mendelssohn probably made his first public concert appearance at the age of nine, when he participated in a

In Leipzig, Mendelssohn concentrated on developing the town's musical life by working with the orchestra, the opera house, the

In Leipzig, Mendelssohn concentrated on developing the town's musical life by working with the orchestra, the opera house, the

On his last visit to Britain in 1847, Mendelssohn was the soloist in

On his last visit to Britain in 1847, Mendelssohn was the soloist in

While Mendelssohn was often presented as equable, happy, and placid in temperament, particularly in the detailed family memoirs published by his nephew Sebastian Hensel after the composer's death, this was misleading. The music historian R. Larry Todd notes "the remarkable process of idealization" of Mendelssohn's character "that crystallized in the memoirs of the composer's circle", including Hensel's. The nickname "discontented Polish count" was given to Mendelssohn on account of his aloofness, and he referred to the epithet in his letters. He was frequently given to fits of temper which occasionally led to collapse. Devrient mentions that on one occasion in the 1830s, when his wishes had been crossed, "his excitement was increased so fearfully ... that when the family was assembled ... he began to talk incoherently in English. The stern voice of his father at last checked the wild torrent of words; they took him to bed, and a profound sleep of twelve hours restored him to his normal state". Such fits may be related to his early death.

Mendelssohn was an enthusiastic visual artist who worked in pencil and

While Mendelssohn was often presented as equable, happy, and placid in temperament, particularly in the detailed family memoirs published by his nephew Sebastian Hensel after the composer's death, this was misleading. The music historian R. Larry Todd notes "the remarkable process of idealization" of Mendelssohn's character "that crystallized in the memoirs of the composer's circle", including Hensel's. The nickname "discontented Polish count" was given to Mendelssohn on account of his aloofness, and he referred to the epithet in his letters. He was frequently given to fits of temper which occasionally led to collapse. Devrient mentions that on one occasion in the 1830s, when his wishes had been crossed, "his excitement was increased so fearfully ... that when the family was assembled ... he began to talk incoherently in English. The stern voice of his father at last checked the wild torrent of words; they took him to bed, and a profound sleep of twelve hours restored him to his normal state". Such fits may be related to his early death.

Mendelssohn was an enthusiastic visual artist who worked in pencil and

Throughout his life Mendelssohn was wary of the more radical musical developments undertaken by some of his contemporaries. He was generally on friendly, if sometimes somewhat cool, terms with

Throughout his life Mendelssohn was wary of the more radical musical developments undertaken by some of his contemporaries. He was generally on friendly, if sometimes somewhat cool, terms with

Mendelssohn married Cécile Charlotte Sophie Jeanrenaud (10 October 1817 – 25 September 1853), the daughter of a French Reformed Church clergyman, on 28 March 1837. The couple had five children: Carl, Marie, Paul, Lili and Felix August. The second youngest child, Felix August, contracted

Mendelssohn married Cécile Charlotte Sophie Jeanrenaud (10 October 1817 – 25 September 1853), the daughter of a French Reformed Church clergyman, on 28 March 1837. The couple had five children: Carl, Marie, Paul, Lili and Felix August. The second youngest child, Felix August, contracted

"Conspiracy of Silence: Could the Release of Secret Documents Shatter Felix Mendelssohn's Reputation?"

''

Something of Mendelssohn's intense attachment to his personal vision of music is conveyed in his comments to a correspondent who suggested converting some of the ''

Something of Mendelssohn's intense attachment to his personal vision of music is conveyed in his comments to a correspondent who suggested converting some of the ''

Mendelssohn's mature symphonies are numbered approximately in the order of publication, rather than the order in which they were composed. The order of composition is: 1, 5, 4, 2, 3. The placement of No. 3 in this sequence is problematic because he worked on it for over a decade, starting the sketches soon after he began work on No. 5 but completing it after both Nos. 5 and 4.

The Symphony No. 1 in C minor for full orchestra was written in 1824, when Mendelssohn was aged 15. This work is experimental, showing the influences of Beethoven and

Mendelssohn's mature symphonies are numbered approximately in the order of publication, rather than the order in which they were composed. The order of composition is: 1, 5, 4, 2, 3. The placement of No. 3 in this sequence is problematic because he worked on it for over a decade, starting the sketches soon after he began work on No. 5 but completing it after both Nos. 5 and 4.

The Symphony No. 1 in C minor for full orchestra was written in 1824, when Mendelssohn was aged 15. This work is experimental, showing the influences of Beethoven and

Mendelssohn wrote the

Mendelssohn wrote the

The Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 (1844), was written for

The Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 (1844), was written for

The musicologist Glenn Stanley observes that " like

The musicologist Glenn Stanley observes that " like

Mendelssohn's two large biblical oratorios, ''

Mendelssohn's two large biblical oratorios, ''

In the immediate wake of Mendelssohn's death, he was mourned both in Germany and England. However, the conservative strain in Mendelssohn, which set him apart from some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, bred a corollary condescension amongst some of them toward his music. Mendelssohn's relations with Berlioz, Liszt and others had been uneasy and equivocal. Listeners who had raised questions about Mendelssohn's talent included

In the immediate wake of Mendelssohn's death, he was mourned both in Germany and England. However, the conservative strain in Mendelssohn, which set him apart from some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, bred a corollary condescension amongst some of them toward his music. Mendelssohn's relations with Berlioz, Liszt and others had been uneasy and equivocal. Listeners who had raised questions about Mendelssohn's talent included

Appreciation of Mendelssohn's work has developed since the mid-20th century, together with the publication of a number of biographies placing his achievements in context. Mercer-Taylor comments on the irony that "this broad-based reevaluation of Mendelssohn's music is made possible, in part, by a general disintegration of the idea of a musical canon", an idea which Mendelssohn "as a conductor, pianist and scholar" had done so much to establish. The critic

Appreciation of Mendelssohn's work has developed since the mid-20th century, together with the publication of a number of biographies placing his achievements in context. Mercer-Taylor comments on the irony that "this broad-based reevaluation of Mendelssohn's music is made possible, in part, by a general disintegration of the idea of a musical canon", an idea which Mendelssohn "as a conductor, pianist and scholar" had done so much to establish. The critic

top 300

Retrieved 16 December 2017. R. Larry Todd noted in 2007, in the context of the impending bicentenary of Mendelssohn's birth, "the intensifying revival of the composer's music over the past few decades", and that "his image has been largely rehabilitated, as musicians and scholars have returned to this paradoxically familiar but unfamiliar European classical composer, and have begun viewing him from new perspectives."

letters to Moscheles

are in Special Collections at

''Leipzig Edition of the Works by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy''

edited by the Sächsische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig Information about the ongoing complete edition.

at ttp://www.lieder.net The LiederNet Archive

Complete Edition: Leipzig Edition of the Letters of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Information about the ongoing complete edition.

The Mendelssohn Project

A project with the objective of "recording of the complete published and unpublished works of Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn"

A virtual exhibit of Mendelssohn manuscripts and early editions held at the Irving S. Gilmore Music Library, Yale University *

Mendelssohn in Scotland

Full text of ''Charles Auchester'' by Elizabeth Sheppard (1891 edition)

(her novel with a hero based on Mendelssohn) * Archival material a

Leeds University Library

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include symphonies

A symphony is an extended musical composition in Western classical music, most often for orchestra. Although the term has had many meanings from its origins in the ancient Greek era, by the late 18th century the word had taken on the meaning com ...

, concerto

A concerto (; plural ''concertos'', or ''concerti'' from the Italian plural) is, from the late Baroque era, mostly understood as an instrumental composition, written for one or more soloists accompanied by an orchestra or other ensemble. The typi ...

s, piano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keyboa ...

music, organ

Organ may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a part of an organism

Musical instruments

* Organ (music), a family of keyboard musical instruments characterized by sustained tone

** Electronic organ, an electronic keyboard instrument

** Hammond ...

music and chamber music

Chamber music is a form of classical music that is composed for a small group of instruments—traditionally a group that could fit in a palace chamber or a large room. Most broadly, it includes any art music that is performed by a small numb ...

. His best-known works include the overture

Overture (from French ''ouverture'', "opening") in music was originally the instrumental introduction to a ballet, opera, or oratorio in the 17th century. During the early Romantic era, composers such as Beethoven and Mendelssohn composed overt ...

and incidental music

Incidental music is music in a play, television program, radio program, video game, or some other presentation form that is not primarily musical. The term is less frequently applied to film music, with such music being referred to instead as t ...

for ''A Midsummer Night's Dream

''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' is a comedy written by William Shakespeare 1595 or 1596. The play is set in Athens, and consists of several subplots that revolve around the marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta. One subplot involves a conflict amon ...

'' (which includes his "Wedding March

Music is often played at wedding celebrations, including during the ceremony and at festivities before or after the event. The music can be performed live by instrumentalists or vocalists or may use pre-recorded songs, depending on the format o ...

"), the '' Italian Symphony'', the '' Scottish Symphony'', the oratorio

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is mus ...

''St. Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

'', the oratorio ''Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My God is Yahweh/YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) was, according to the Books of ...

'', the overture ''The Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebride ...

'', the mature Violin Concerto

A violin concerto is a concerto for solo violin (occasionally, two or more violins) and instrumental ensemble (customarily orchestra). Such works have been written since the Baroque period, when the solo concerto form was first developed, up thro ...

and the String Octet

A string octet is a piece of music written for eight string instruments, or sometimes the group of eight players. It usually consists of four violins, two violas and two cellos, or four violins, two violas, a cello and a double bass.

Notable s ...

. The melody for the Christmas carol "Hark! The Herald Angels Sing

"Hark! The Herald Angels Sing" is an English Christmas carol that first appeared in 1739 in the collection ''Hymns and Sacred Poems''. The carol, based on , tells of an angelic chorus singing praises to God. As it is known in the modern era, it f ...

" is also his. Mendelssohn's ''Songs Without Words

''Songs Without Words'' (') is a series of short lyrical piano works by the Romantic composer Felix Mendelssohn written between 1829 and 1845. His sister, Fanny Mendelssohn, and other composers also wrote pieces in the same genre.

Music

The ...

'' are his most famous solo piano compositions.

Mendelssohn's grandfather was the renowned Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

philosopher Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn (6 September 1729 – 4 January 1786) was a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian. His writings and ideas on Jews and the Jewish religion and identity were a central element in the development of the ''Haskalah'', or 'Je ...

, but Felix was initially raised without religion. He was baptised at the age of seven, becoming a Reformed Christian

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Calv ...

. He was recognised early as a musical prodigy

A child prodigy is defined in psychology research literature as a person under the age of ten who produces meaningful output in some domain to the level of an adult expert performer. This is a list of young children (under age 10) who displayed a ...

, but his parents were cautious and did not seek to capitalise on his talent. His sister Fanny Mendelssohn

Fanny Mendelssohn (14 November 1805 – 14 May 1847) was a German composer and pianist of the early Romantic era who was also known as Fanny (Cäcilie) Mendelssohn Bartholdy and, after her marriage, Fanny Hensel (as well as Fanny Mendelssohn He ...

received a similar musical education and was a talented composer and pianist in her own right; some of her early songs were published under her brother's name and her ''Easter Sonata

The ''Easter Sonata'' () is a piano sonata in the key of A major, composed by Fanny Mendelssohn. It was lost for 150 years and when found attributed to her brother Felix, before finally being recognized as hers. It premiered in her name on 7 Sept ...

'' was for a time mistakenly attributed to him after being lost and rediscovered in the 1970s.

Mendelssohn enjoyed early success in Germany, and revived interest in the music of Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

, notably with his performance of the ''St Matthew Passion

The ''St Matthew Passion'' (german: Matthäus-Passion, links=-no), BWV 244, is a '' Passion'', a sacred oratorio written by Johann Sebastian Bach in 1727 for solo voices, double choir and double orchestra, with libretto by Picander. It sets ...

'' in 1829. He became well received in his travels throughout Europe as a composer, conductor and soloist; his ten visits to Britain – during which many of his major works were premiered – form an important part of his adult career. His essentially conservative musical tastes set him apart from more adventurous musical contemporaries such as Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

, Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

, Charles-Valentin Alkan

Charles-Valentin Alkan (; 30 November 1813 – 29 March 1888) was a French Jewish composer and virtuoso pianist. At the height of his fame in the 1830s and 1840s he was, alongside his friends and colleagues Frédéric Chopin and Franz Lisz ...

and Hector Berlioz

In Greek mythology, Hector (; grc, Ἕκτωρ, Hektōr, label=none, ) is a character in Homer's Iliad. He was a Trojan prince and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. Hector led the Trojans and their allies in the defense o ...

. The Leipzig Conservatory

The University of Music and Theatre "Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy" Leipzig (german: Hochschule für Musik und Theater "Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy" Leipzig) is a public university in Leipzig (Saxony, Germany). Founded in 1843 by Felix Mendelssohn ...

, which he founded, became a bastion of this anti-radical outlook. After a long period of relative denigration due to changing musical tastes and antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, his creative originality has been re-evaluated. He is now among the most popular composers of the Romantic era.

Life

Childhood

Felix Mendelssohn was born on 3 February 1809, in

Felix Mendelssohn was born on 3 February 1809, in Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, at the time an independent city-state, in the same house where, a year later, the dedicatee and first performer of his Violin Concerto, Ferdinand David

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

, would be born. Mendelssohn's father, the banker Abraham Mendelssohn

Abraham Ernst Mendelssohn Bartholdy (born Abraham Mendelssohn; 10 December 1776 – 19 November 1835) was a German banker and philanthropist. He was the father of Fanny Mendelssohn, Felix Mendelssohn, Rebecka Mendelssohn, and Paul Mendelssohn.

E ...

, was the son of the German Jewish

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (''circa'' 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish ...

philosopher Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn (6 September 1729 – 4 January 1786) was a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian. His writings and ideas on Jews and the Jewish religion and identity were a central element in the development of the ''Haskalah'', or 'Je ...

, whose family was prominent in the German Jewish community. Until his baptism at age seven, Mendelssohn was brought up largely without religion. His mother, Lea Salomon, was a member of the Itzig family

Many of the thirteen children of Daniel Itzig and Miriam Wulff, and their descendants and spouses, had significant impact on both Jewish and German social and cultural (especially musical) history. Notable ones are set out below.

Daniel Itzig (172 ...

and a sister of Jakob Salomon Bartholdy __NOTOC__

Jakob Ludwig Salomon Bartholdy (13 May 1779 – 27 July 1825) was a Prussian diplomat and art patron.

Life

He was born Jakob Salomon in Berlin of Jewish parentage. His father was Levin Jakob Salomon and his mother was Bella Salomon, né ...

. Mendelssohn was the second of four children; his older sister Fanny also displayed exceptional and precocious musical talent.

The family moved to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

in 1811, leaving Hamburg in disguise in fear of French reprisal for the Mendelssohn bank's role in breaking Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's Continental System

The Continental Blockade (), or Continental System, was a large-scale embargo against British trade by Napoleon Bonaparte against the British Empire from 21 November 1806 until 11 April 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon issued the Berlin ...

blockade. Abraham and Lea Mendelssohn sought to give their children – Fanny, Felix, Paul and Rebecka – the best education possible. Fanny became a pianist well known in Berlin musical circles as a composer; originally Abraham had thought that she, rather than Felix, would be the more musical. But it was not considered proper, by either Abraham or Felix, for a woman to pursue a career in music, so she remained an active but non-professional musician. Abraham was initially disinclined to allow Felix to follow a musical career until it became clear that he was seriously dedicated.

Mendelssohn grew up in an intellectual environment. Frequent visitors to the salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon (P ...

organised by his parents at their home in Berlin included artists, musicians and scientists, among them Wilhelm

Wilhelm may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* William Charles John Pitcher, costume designer known professionally as "Wilhelm"

* Wilhelm (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

Other uses

* Mount ...

and Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, p ...

, and the mathematician Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet

Johann Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet (; 13 February 1805 – 5 May 1859) was a German mathematician who made deep contributions to number theory (including creating the field of analytic number theory), and to the theory of Fourier series and ...

(whom Mendelssohn's sister Rebecka would later marry). The musician Sarah Rothenburg has written of the household that "Europe came to their living room".

Surname

Abraham Mendelssohn renounced the Jewish religion prior to Felix's birth; he and his wife decided not to have Felixcircumcised

Circumcision is a surgical procedure, procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin ...

, in contravention of the Jewish tradition. Felix and his siblings were at first brought up without religious education; on 21 March 1816, they were baptized in a private ceremony in the family's Berlin apartment by the Reformed Protestant minister of the Jerusalem Church, at which time Felix was given the additional names Jakob Ludwig. Abraham and his wife Lea were baptised in 1822, and formally adopted the surname Mendelssohn Bartholdy (which they had used since 1812) for themselves and for their children.

The name Bartholdy was added at the suggestion of Lea's brother, Jakob Salomon Bartholdy, who had inherited a property of this name in Luisenstadt

Luisenstadt () is a former quarter (''Stadtteil'') of central Berlin, now divided between the present localities of Mitte and Kreuzberg. It gave its name to the Luisenstadt Canal and the Luisenstädtische Kirche.

History

The area of the neighb ...

and adopted it as his own surname. In an 1829 letter to Felix, Abraham explained that adopting the Bartholdy name was meant to demonstrate a decisive break with the traditions of his father Moses: "There can no more be a Christian Mendelssohn than there can be a Jewish Confucius

Confucius ( ; zh, s=, p=Kǒng Fūzǐ, "Master Kǒng"; or commonly zh, s=, p=Kǒngzǐ, labels=no; – ) was a Chinese philosopher and politician of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. C ...

". (Letter to Felix of 8 July 1829). On embarking on his musical career, Felix did not entirely drop the name Mendelssohn as Abraham had requested, but in deference to his father signed his letters and had his visiting cards printed using the form 'Mendelssohn Bartholdy'. In 1829, his sister Fanny wrote to him of "Bartholdy ..this name that we all dislike".

Career

Musical education

Mendelssohn began taking piano lessons from his mother when he was six, and at seven was tutored byMarie Bigot

Marie Kiéné Bigot de Morogues (3 March 1786 – 16 September 1820) was a French pianist and composer. She is best known for her sonatas and études.

Career

Marie Kiéné was born in Colmar in Alsace. After marrying M. Bigot, she moved to Vienn ...

in Paris. Later in Berlin, all four Mendelssohn children studied piano with Ludwig Berger Ludwig Berger may refer to:

* Ludwig Berger (composer) (1777–1839), German composer

* Ludwig Berger (director)

Ludwig Berger (born Ludwig Bamberger; 6 January 1892 – 18 May 1969) was a German-Jewish film director, screenwriter and theat ...

, who was himself a former student of Muzio Clementi

Muzio Filippo Vincenzo Francesco Saverio Clementi (23 January 1752 – 10 March 1832) was an Italian composer, virtuoso pianist, pedagogue, conductor, music publisher, editor, and piano manufacturer, who was mostly active in England.

Encourag ...

. From at least May 1819 Mendelssohn (initially with his sister Fanny) studied counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

and composition with Carl Friedrich Zelter

Carl Friedrich Zelter (11 December 1758 15 May 1832)Grove/Fuller-Datei:Carl-Friedrich-Zelter.jpegMaitland, 1910. The Zelter entry takes up parts of pages 593-595 of Volume V. was a German composer, conductor and teacher of music. Working in his ...

in Berlin. This was an important influence on his future career. Zelter had almost certainly been recommended as a teacher by his aunt Sarah Levy

Sarah Levy (born September 10, 1986) is a Canadian actress best known for her role of Twyla Sands in ''Schitt's Creek''.

Early life

Levy is the daughter of actor Eugene Levy and Deborah Divine, and the sister of actor Dan Levy. She graduated ...

, who had been a pupil of W. F. Bach

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (22 November 17101 July 1784), the second child and eldest son of Johann Sebastian Bach and Maria Barbara Bach, was a German composer and performer. Despite his acknowledged genius as an organist, improviser and composer ...

and a patron of C. P. E. Bach

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (8 March 1714 – 14 December 1788), also formerly spelled Karl Philipp Emmanuel Bach, and commonly abbreviated C. P. E. Bach, was a German Classical period musician and composer, the fifth child and sec ...

. Sarah Levy displayed some talent as a keyboard player, and often played with Zelter's orchestra at the Berliner Singakademie; she and the Mendelssohn family were among its leading patrons. Sarah had formed an important collection of Bach family manuscripts which she bequeathed to the Singakademie; Zelter, whose tastes in music were conservative, was also an admirer of the Bach tradition. This undoubtedly played a significant part in forming Felix Mendelssohn's musical tastes, as his works reflect this study of Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including t ...

and early classical music. His fugue

In music, a fugue () is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the c ...

s and chorale

Chorale is the name of several related musical forms originating in the music genre of the Lutheran chorale:

* Hymn tune of a Lutheran hymn (e.g. the melody of "Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme"), or a tune in a similar format (e.g. one of the t ...

s especially reflect a tonal clarity and use of counterpoint reminiscent of Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

, whose music influenced him deeply.

Early maturity

Mendelssohn probably made his first public concert appearance at the age of nine, when he participated in a

Mendelssohn probably made his first public concert appearance at the age of nine, when he participated in a chamber music

Chamber music is a form of classical music that is composed for a small group of instruments—traditionally a group that could fit in a palace chamber or a large room. Most broadly, it includes any art music that is performed by a small numb ...

concert accompanying a horn

Horn most often refers to:

*Horn (acoustic), a conical or bell shaped aperture used to guide sound

** Horn (instrument), collective name for tube-shaped wind musical instruments

*Horn (anatomy), a pointed, bony projection on the head of various ...

duo. He was a prolific composer from an early age. As an adolescent, his works were often performed at home with a private orchestra for the associates of his wealthy parents amongst the intellectual elite of Berlin. Between the ages of 12 and 14, Mendelssohn wrote 13 string symphonies for such concerts, and a number of chamber works. His first work, a piano quartet, was published when he was 13. It was probably Abraham Mendelssohn who procured the publication of this quartet by the house of Schlesinger Schlesinger is a German surname (in part also Jewish) meaning "Silesian" from the older regional term ''Schlesinger''; someone from ''Schlesing'' (Silesia); in modern Standard German (or Hochdeutsch) a '' Schlesier'' is someone from ''Schlesien'' a ...

. In 1824 the 15-year-old wrote his first symphony for full orchestra (in C minor, Op. 11).

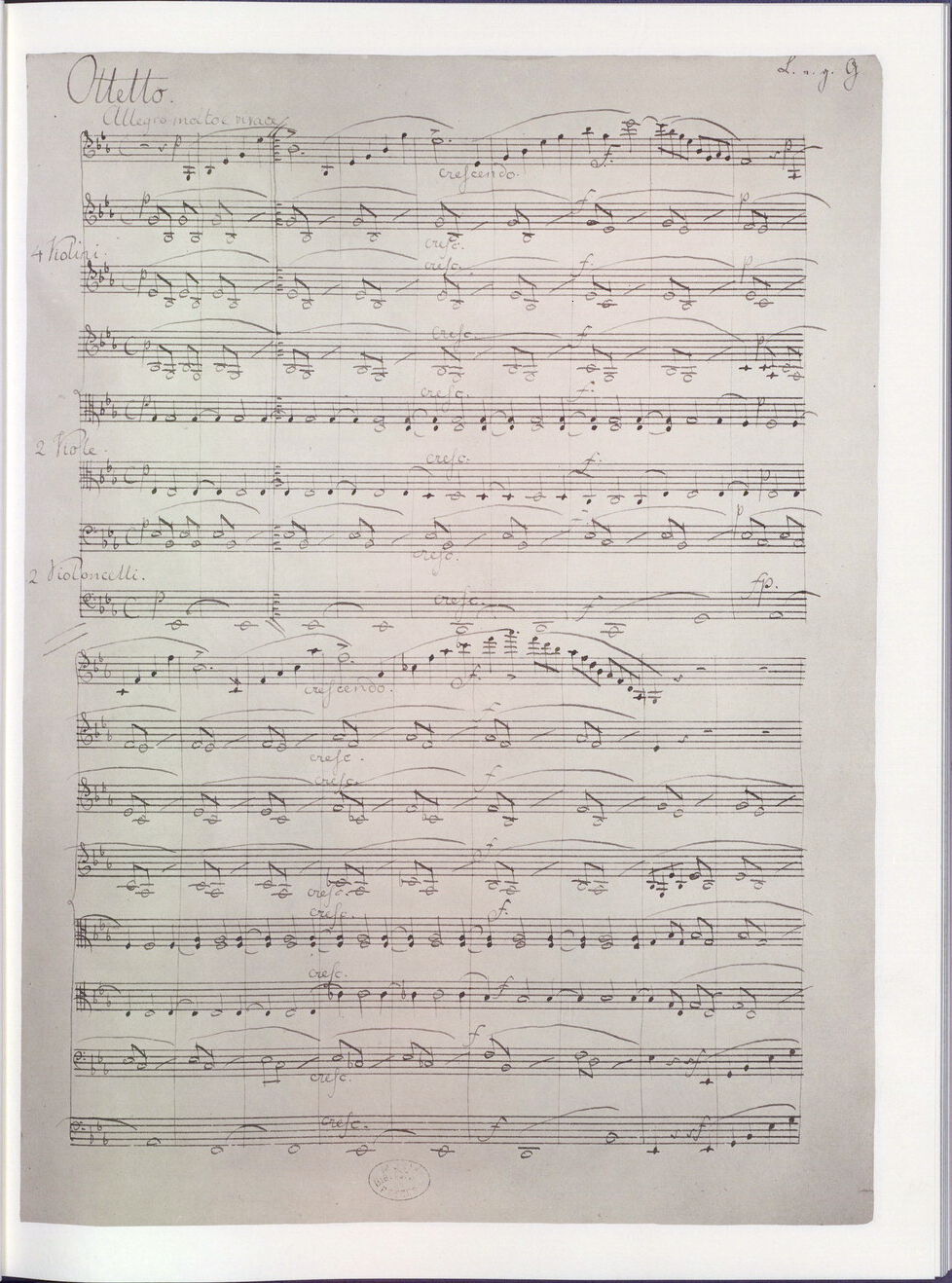

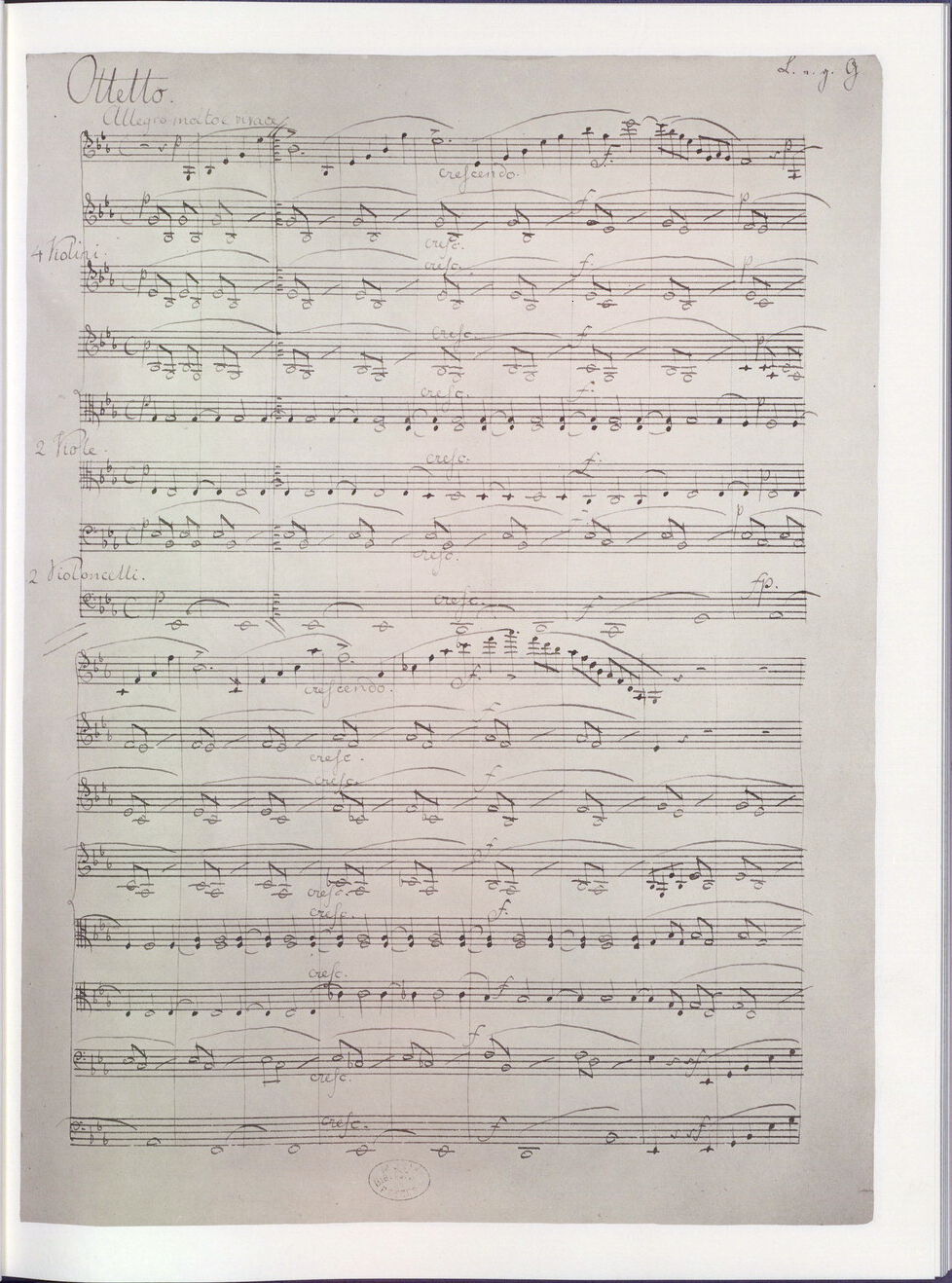

At age 16 Mendelssohn wrote his String Octet in E-flat major, a work which has been regarded as "mark ngthe beginning of his maturity as a composer." This Octet and his Overture

Overture (from French ''ouverture'', "opening") in music was originally the instrumental introduction to a ballet, opera, or oratorio in the 17th century. During the early Romantic era, composers such as Beethoven and Mendelssohn composed overt ...

to Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''A Midsummer Night's Dream

''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' is a comedy written by William Shakespeare 1595 or 1596. The play is set in Athens, and consists of several subplots that revolve around the marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta. One subplot involves a conflict amon ...

'', which he wrote a year later in 1826, are the best-known of his early works. (Later, in 1843, he also wrote incidental music

Incidental music is music in a play, television program, radio program, video game, or some other presentation form that is not primarily musical. The term is less frequently applied to film music, with such music being referred to instead as t ...

for the play, including the famous "Wedding March

Music is often played at wedding celebrations, including during the ceremony and at festivities before or after the event. The music can be performed live by instrumentalists or vocalists or may use pre-recorded songs, depending on the format o ...

".) The Overture is perhaps the earliest example of a concert overture

Overture (from French ''ouverture'', "opening") in music was originally the instrumental introduction to a ballet, opera, or oratorio in the 17th century. During the early Romantic era, composers such as Beethoven and Mendelssohn composed overt ...

– that is, a piece not written deliberately to accompany a staged performance but to evoke a literary theme in performance on a concert platform; this was a genre which became a popular form in musical Romanticism.

In 1824 Mendelssohn studied under the composer and piano virtuoso Ignaz Moscheles

Isaac Ignaz Moscheles (; 23 May 179410 March 1870) was a Bohemian piano virtuoso and composer. He was based initially in London and later at Leipzig, where he joined his friend and sometime pupil Felix Mendelssohn as professor of piano at the ...

, who confessed in his diaries that he had little to teach him. Moscheles and Mendelssohn became close colleagues and lifelong friends. The year 1827 saw the premiere – and sole performance in his lifetime – of Mendelssohn's opera ''Die Hochzeit des Camacho

''Die Hochzeit des Camacho'' (''Camacho's Wedding'') is a Singspiel in two acts by Felix Mendelssohn, to a libretto probably written largely by , based on an episode in ''Don Quixote'' by Cervantes. The opera is listed as Mendelssohn's op. 10. ...

''. The failure of this production left him disinclined to venture into the genre again.

Besides music, Mendelssohn's education included art, literature, languages, and philosophy. He had a particular interest in classical literature

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

and translated Terence

Publius Terentius Afer (; – ), better known in English as Terence (), was a Roman African playwright during the Roman Republic. His comedies were performed for the first time around 166–160 BC. Terentius Lucanus, a Roman senator, brought ...

's ''Andria

Andria (; Barese: ) is a city and ''comune'' in Apulia ( southern Italy). It is an agricultural and service center, producing wine, olives and almonds. It is the fourth-largest municipality in the Apulia region (behind Bari, Taranto, and Fogg ...

'' for his tutor Heyse in 1825; Heyse was impressed and had it published in 1826 as a work of "his pupil, F****" .e. "Felix" (asterisks as provided in original text) This translation also qualified Mendelssohn to study at the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

, where from 1826 to 1829 he attended lectures on aesthetics by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends ...

, on history by Eduard Gans

Eduard Gans (March 22, 1797 – May 5, 1839) was a German jurist.

Biography

Gans was born in Berlin to prosperous Jewish parents. He studied law first at the Friedrich Wilhelm University, Berlin, then at Göttingen, and finally at Heidelberg, w ...

, and on geography by Carl Ritter

Carl Ritter (August 7, 1779September 28, 1859) was a German geographer. Along with Alexander von Humboldt, he is considered one of the founders of modern geography. From 1825 until his death, he occupied the first chair in geography at the Univer ...

.

Meeting Goethe and conducting Bach

In 1821 Zelter introduced Mendelssohn to his friend and correspondent, the writerJohann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as trea ...

(then in his seventies), who was greatly impressed by the child, leading to perhaps the earliest confirmed comparison with Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

in the following conversation between Goethe and Zelter:

Mendelssohn was invited to meet Goethe on several later occasions, and set a number of Goethe's poems to music. His other compositions inspired by Goethe include the overture '' Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage'' (Op. 27, 1828), and the cantata ''Die erste Walpurgisnacht

''Die erste Walpurgisnacht'' (''The First Walpurgis Night'') is a poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, telling of the attempts of Druids in the Harz mountains to practice their pagan rituals in the face of new and dominating Christian forces.

It wa ...

'' (''The First Walpurgis Night'', Op. 60, 1832).

In 1829, with the backing of Zelter and the assistance of the actor Eduard Devrient

(Philipp) Eduard Devrient (11 August 18014 October 1877) was a German baritone, librettist, playwright, actor, theatre director, and theatre reformer and historian.

Devrient came from a theatrical family. His uncle was Ludwig Devrient and his b ...

, Mendelssohn arranged and conducted a performance in Berlin of Bach's ''St Matthew Passion

The ''St Matthew Passion'' (german: Matthäus-Passion, links=-no), BWV 244, is a '' Passion'', a sacred oratorio written by Johann Sebastian Bach in 1727 for solo voices, double choir and double orchestra, with libretto by Picander. It sets ...

''. Four years previously his grandmother, Bella Salomon, had given him a copy of the manuscript of this (by then all-but-forgotten) masterpiece. The orchestra and choir for the performance were provided by the Berlin Singakademie. The success of this performance, one of the very few since Bach's death and the first ever outside of Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

, was the central event in the revival of Bach's music in Germany and, eventually, throughout Europe. It earned Mendelssohn widespread acclaim at the age of 20. It also led to one of the few explicit references which Mendelssohn made to his origins: "To think that it took an actor and a Jew's son to revive the greatest Christian music for the world!"

Over the next few years Mendelssohn travelled widely. His first visit to England was in 1829; other places visited during the 1830s included Vienna, Florence, Milan, Rome and Naples, in all of which he met with local and visiting musicians and artists. These years proved to be the germination for some of his most famous works, including the ''Hebrides Overture

''The Hebrides'' (; german: Die Hebriden) is a concert overture that was composed by Felix Mendelssohn in 1830, revised in 1832, and published the next year as Mendelssohn's Op. 26. Some consider it an early tone poem.

It was inspired by one of ...

'' and the '' Scottish'' and ''Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

'' symphonies.

Düsseldorf

On Zelter's death in 1832, Mendelssohn had hopes of succeeding him as conductor of the Singakademie; but at a vote in January 1833 he was defeated for the post byCarl Friedrich Rungenhagen

Carl Friedrich Rungenhagen (first name also sometimes given as Karl;Eitner (1889) 27 September 1778 – 21 December 1851) was a German composer and music teacher.

Life

Rungenhagen abandoned early study of art under Daniel Chodowiecki and jo ...

. This may have been because of Mendelssohn's youth, and fear of possible innovations; it was also suspected by some to be attributable to his Jewish ancestry. Following this rebuff, Mendelssohn divided most of his professional time over the next few years between Britain and Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in th ...

, where he was appointed musical director (his first paid post as a musician) in 1833.

In the spring of that year Mendelssohn directed the Lower Rhenish Music Festival

The Lower Rhenish Music Festival (German: Das Niederrheinische Musikfest) was one of the most important festivals of classical music, which happened every year between 1818 and 1958, with few exceptions, at Pentecost for 112 times.

History

In t ...

in Düsseldorf, beginning with a performance of George Frideric Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque music, Baroque composer well known for his opera#Baroque era, operas, oratorios, anthems, concerto grosso, concerti grossi, ...

's oratorio ''Israel in Egypt

''Israel in Egypt'', HWV 54, is a biblical oratorio by the composer George Frideric Handel. Most scholars believe the libretto was prepared by Charles Jennens, who also compiled the biblical texts for Handel's ''Messiah''. It is composed ent ...

'' prepared from the original score, which he had found in London. This precipitated a Handel revival in Germany, similar to the reawakened interest in J. S. Bach following his performance of the ''St. Matthew Passion''. Mendelssohn worked with the dramatist Karl Immermann

Karl Leberecht Immermann (24 April 1796 – 25 August 1840) was a German dramatist, novelist and a poet.

Biography

He was born at Magdeburg, the son of a government official. In 1813 he went to study law at Halle, where he remained, after t ...

to improve local theatre standards, and made his first appearance as an opera conductor in Immermann's production of Mozart's ''Don Giovanni

''Don Giovanni'' (; K. 527; Vienna (1788) title: , literally ''The Rake Punished, or Don Giovanni'') is an opera in two acts with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an Italian libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte. Its subject is a centuries-old Spanis ...

'' at the end of 1833, where he took umbrage at the audience's protests about the cost of tickets. His frustration at his everyday duties in Düsseldorf, and the city's provincialism, led him to resign his position at the end of 1834. He had offers from both Munich and Leipzig for important musical posts, namely, direction of the Munich Opera

The Bayerische Staatsoper is a German opera company based in Munich. Its main venue is the Nationaltheater München, and its orchestra the Bayerische Staatsorchester.

History

The parent ensemble of the company was founded in 1653, under Prince ...

, the editorship of the prestigious Leipzig music journal the ''Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung

The ''Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung'' (''General music newspaper'') was a German-language periodical published in the 19th century. Comini (2008) has called it "the foremost German-language musical periodical of its time". It reviewed musical e ...

'', and direction of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra

The Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra (Gewandhausorchester; also previously known in German as the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig) is a German symphony orchestra based in Leipzig, Germany. The orchestra is named after the concert hall in which it is bas ...

; he accepted the latter in 1835.

Leipzig and Berlin

In Leipzig, Mendelssohn concentrated on developing the town's musical life by working with the orchestra, the opera house, the

In Leipzig, Mendelssohn concentrated on developing the town's musical life by working with the orchestra, the opera house, the Thomanerchor

The Thomanerchor (English: St. Thomas Choir of Leipzig) is a boys' choir in Leipzig, Germany. The choir was founded in 1212. The choir comprises about 90 boys from 9 to 18 years of age. The members, called ''Thomaner'', reside in a boarding scho ...

(of which Bach had been a director), and the city's other choral and musical institutions. Mendelssohn's concerts included, in addition to many of his own works, three series of "historical concerts" featuring music of the eighteenth century, and a number of works by his contemporaries. He was deluged by offers of music from rising and would-be composers; among these was Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

, who submitted his early Symphony, the score of which, to Wagner's disgust, Mendelssohn lost or mislaid. Mendelssohn also revived interest in the music of Franz Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. Despite his short lifetime, Schubert left behind a vast ''oeuvre'', including more than 600 secular vocal wor ...

. Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann (; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career a ...

discovered the manuscript of Schubert's Ninth Symphony and sent it to Mendelssohn, who promptly premiered it in Leipzig on 21 March 1839, more than a decade after Schubert's death.

A landmark event during Mendelssohn's Leipzig years was the premiere of his oratorio '' Paulus'', (the English version of this is known as ''St. Paul''), given at the Lower Rhenish Festival in Düsseldorf in 1836, shortly after the death of the composer's father, which affected him greatly; Felix wrote that he would "never cease to endeavour to gain his approval ... although I can no longer enjoy it". ''St. Paul'' seemed to many of Mendelssohn's contemporaries to be his finest work, and sealed his European reputation.

When Friedrich Wilhelm IV

Frederick William IV (german: Friedrich Wilhelm IV.; 15 October 17952 January 1861), the eldest son and successor of Frederick William III of Prussia, reigned as King of Prussia from 7 June 1840 to his death on 2 January 1861. Also referred to ...

came to the Prussian throne in 1840 with ambitions to develop Berlin as a cultural centre (including the establishment of a music school, and reform of music for the church), the obvious choice to head these reforms was Mendelssohn. He was reluctant to undertake the task, especially in the light of his existing strong position in Leipzig. Mendelssohn nonetheless spent some time in Berlin, writing some church music such as ''Die Deutsche Liturgie

, MWV B 57, is a collection of musical settings of the ten sung elements in the Protestant liturgy, composed by Felix Mendelssohn for double choir a cappella. He wrote it in 1846 for the Berlin Cathedral, on a request by the emperor, Friedrich ...

'', and, at the King's request, music for productions of Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or co ...

's ''Antigone

In Greek mythology, Antigone ( ; Ancient Greek: Ἀντιγόνη) is the daughter of Oedipus and either his mother Jocasta or, in another variation of the myth, Euryganeia. She is a sister of Polynices, Eteocles, and Ismene.Roman, L., & Roma ...

'' (1841 – an overture and seven pieces) and ''Oedipus at Colonus'' (1845), ''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' (1843) and Racine

Jean-Baptiste Racine ( , ) (; 22 December 163921 April 1699) was a French dramatist, one of the three great playwrights of 17th-century France, along with Molière and Corneille as well as an important literary figure in the Western traditio ...

's ''Athalie

''Athalie'' (, sometimes translated ''Athalia'') is a 1691 play, the final tragedy of Jean Racine, and has been described as the masterpiece of "one of the greatest literary artists known" and the "ripest work" of Racine's genius. Charles August ...

'' (1845). But the funds for the school never materialised, and many of the court's promises to Mendelssohn regarding finances, title, and concert programming were broken. He was therefore not displeased to have the excuse to return to Leipzig.

In 1843 Mendelssohn founded a major music school – the Leipzig Conservatory, now the Hochschule für Musik und Theater "Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy". where he persuaded Ignaz Moscheles and Robert Schumann to join him. Other prominent musicians, including the string players Ferdinand David and Joseph Joachim

Joseph Joachim (28 June 1831 – 15 August 1907) was a Hungarian violinist, conductor, composer and teacher who made an international career, based in Hanover and Berlin. A close collaborator of Johannes Brahms, he is widely regarded as one of ...

and the music theorist Moritz Hauptmann

Moritz Hauptmann (13 October 1792, Dresden – 3 January 1868, Leipzig), was a German music theorist, teacher and composer. His principal theoretical work is the 1853 ''Die Natur der Harmonie und der Metrik'' explores numerous topics, particular ...

, also became staff members. After Mendelssohn's death in 1847, his musically conservative tradition was carried on when Moscheles succeeded him as head of the Conservatory.

Mendelssohn in Britain

Mendelssohn first visited Britain in 1829, where Moscheles, who had already settled in London, introduced him to influential musical circles. In the summer he visitedEdinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, where he met among others the composer John Thomson, whom he later recommended for the post of Professor of Music at Edinburgh University

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 1582 ...

. He made ten visits to Britain, lasting about 20 months; he won a strong following, which enabled him to make a good impression on British musical life. He composed and performed, and also edited for British publishers the first critical editions of oratorio

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is mus ...

s of Handel and of the organ music of J. S. Bach. Scotland inspired two of his most famous works: the overture ''The Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebride ...

'' (also known as ''Fingal's Cave''); and the ''Scottish Symphony'' (Symphony No. 3). An English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

commemorating Mendelssohn's residence in London was placed at 4 Hobart Place in Belgravia

Belgravia () is a Districts of London, district in Central London, covering parts of the areas of both the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

Belgravia was known as the 'Five Fields' Tudor Period, during the ...

, London, in 2013.

His protégé, the British composer and pianist William Sterndale Bennett

Sir William Sterndale Bennett (13 April 18161 February 1875) was an English composer, pianist, conductor and music educator. At the age of ten Bennett was admitted to the London Royal Academy of Music (RAM), where he remained for ten years. B ...

, worked closely with Mendelssohn during this period, both in London and Leipzig. He first heard Bennett perform in London in 1833 aged 17. Bennett appeared with Mendelssohn in concerts in Leipzig throughout the 1836/1837 season.

On Mendelssohn's eighth British visit in the summer of 1844, he conducted five of the Philharmonic concerts in London, and wrote: " ver before was anything like this season – we never went to bed before half-past one, every hour of every day was filled with engagements three weeks beforehand, and I got through more music in two months than in all the rest of the year." (Letter to Rebecka Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Soden, 22 July 1844). On subsequent visits Mendelssohn met Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

and her husband Prince Albert, himself a composer, who both greatly admired his music.

Mendelssohn's oratorio ''Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My God is Yahweh/YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) was, according to the Books of ...

'' was commissioned by the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival

The Birmingham Triennial Musical Festival, in Birmingham, England, founded in 1784, was the longest-running classical music festival of its kind. It last took place in 1912.

History

The first music festival, over three days in September 1768 ...

and premiered on 26 August 1846, at the Town Hall, Birmingham. It was composed to a German text translated into English by William Bartholomew, who authored and translated many of Mendelssohn's works during his time in England.

On his last visit to Britain in 1847, Mendelssohn was the soloist in

On his last visit to Britain in 1847, Mendelssohn was the soloist in Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

's Piano Concerto No. 4 and conducted his own ''Scottish Symphony'' with the Philharmonic Orchestra before the Queen and Prince Albert.

Death

Mendelssohn suffered from poor health in the final years of his life, probably aggravated by nervous problems and overwork. A final tour of England left him exhausted and ill, and the death of his sister, Fanny, on 14 May 1847, caused him further distress. Less than six months later, on 4 November, aged 38, Mendelssohn died in Leipzig after a series of strokes. His grandfather Moses, Fanny, and both his parents had all died from similar apoplexies. Although he had been generally meticulous in the management of his affairs, he diedintestate

Intestacy is the condition of the estate of a person who dies without having in force a valid will or other binding declaration. Alternatively this may also apply where a will or declaration has been made, but only applies to part of the estat ...

.

Mendelssohn's funeral was held at the Paulinerkirche, Leipzig, and he was buried at the Dreifaltigkeitsfriedhof I in Berlin-Kreuzberg

Kreuzberg () is a district of Berlin, Germany. It is part of the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg borough located south of Mitte. During the Cold War era, it was one of the poorest areas of West Berlin, but since German reunification in 1990 it ha ...

. The pallbearer

A pallbearer is one of several participants who help carry the casket at a funeral. They may wear white gloves in order to prevent damaging the casket and to show respect to the deceased person.

Some traditions distinguish between the roles of ...

s included Moscheles, Schumann and Niels Gade

Niels Wilhelm Gade (22 February 1817 – 21 December 1890) was a Danish composer, conductor, violinist, organist and teacher. Together with Johan Peter Emilius Hartmann, he was the leading Danish musician of his day.

Biography

Gade was born ...

. Mendelssohn had once described death, in a letter to a stranger, as a place "where it is to be hoped there is still music, but no more sorrow or partings."

Personal life

Personality

While Mendelssohn was often presented as equable, happy, and placid in temperament, particularly in the detailed family memoirs published by his nephew Sebastian Hensel after the composer's death, this was misleading. The music historian R. Larry Todd notes "the remarkable process of idealization" of Mendelssohn's character "that crystallized in the memoirs of the composer's circle", including Hensel's. The nickname "discontented Polish count" was given to Mendelssohn on account of his aloofness, and he referred to the epithet in his letters. He was frequently given to fits of temper which occasionally led to collapse. Devrient mentions that on one occasion in the 1830s, when his wishes had been crossed, "his excitement was increased so fearfully ... that when the family was assembled ... he began to talk incoherently in English. The stern voice of his father at last checked the wild torrent of words; they took him to bed, and a profound sleep of twelve hours restored him to his normal state". Such fits may be related to his early death.

Mendelssohn was an enthusiastic visual artist who worked in pencil and

While Mendelssohn was often presented as equable, happy, and placid in temperament, particularly in the detailed family memoirs published by his nephew Sebastian Hensel after the composer's death, this was misleading. The music historian R. Larry Todd notes "the remarkable process of idealization" of Mendelssohn's character "that crystallized in the memoirs of the composer's circle", including Hensel's. The nickname "discontented Polish count" was given to Mendelssohn on account of his aloofness, and he referred to the epithet in his letters. He was frequently given to fits of temper which occasionally led to collapse. Devrient mentions that on one occasion in the 1830s, when his wishes had been crossed, "his excitement was increased so fearfully ... that when the family was assembled ... he began to talk incoherently in English. The stern voice of his father at last checked the wild torrent of words; they took him to bed, and a profound sleep of twelve hours restored him to his normal state". Such fits may be related to his early death.

Mendelssohn was an enthusiastic visual artist who worked in pencil and watercolour

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour (British English; see spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin ''aqua'' "water"), is a painting method”Watercolor may be as old as art itself, going back to t ...

, a skill which he enjoyed throughout his life. His correspondences indicate that he could write with considerable wit in German and English – these letters are sometimes accompanied by humorous sketches and cartoons.

Religion

On 21 March 1816, at the age of seven years, Mendelssohn was baptised with his brother and sisters in a home ceremony by Johann Jakob Stegemann, minister of theEvangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide Interdenominationalism, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "bor ...

congregation of Berlin's Jerusalem Church and New Church. Although Mendelssohn was a conforming Christian as a member of the Reformed Church, he was both conscious and proud of his Jewish ancestry and notably of his connection with his grandfather, Moses Mendelssohn. He was the prime mover in proposing to the publisher Heinrich Brockhaus a complete edition of Moses's works, which continued with the support of his uncle, Joseph Mendelssohn

Joseph Mendelssohn (11 August 1770 – 24 November 1848) was a German Jewish banker.

He was the oldest son of the influential philosopher Moses Mendelssohn. In 1795, he founded his own banking house. In 1804, his younger brother, Abraham Mendel ...

. Felix was notably reluctant, either in his letters or conversation, to comment on his innermost beliefs; his friend Devrient wrote that " isdeep convictions were never uttered in intercourse with the world; only in rare and intimate moments did they ever appear, and then only in the slightest and most humorous allusions". Thus for example in a letter to his sister Rebecka, Mendelssohn rebukes her complaint about an unpleasant relative: "What do you mean by saying you are not hostile to Jews? I hope this was a joke ..It is really sweet of you that you do not despise your family, isn't it?" Some modern scholars have devoted considerable energy to demonstrate either that Mendelssohn was deeply sympathetic to his ancestors' Jewish beliefs, or that he was hostile to this and sincere in his Christian beliefs.

Mendelssohn and his contemporaries

Throughout his life Mendelssohn was wary of the more radical musical developments undertaken by some of his contemporaries. He was generally on friendly, if sometimes somewhat cool, terms with

Throughout his life Mendelssohn was wary of the more radical musical developments undertaken by some of his contemporaries. He was generally on friendly, if sometimes somewhat cool, terms with Hector Berlioz

In Greek mythology, Hector (; grc, Ἕκτωρ, Hektōr, label=none, ) is a character in Homer's Iliad. He was a Trojan prince and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. Hector led the Trojans and their allies in the defense o ...

, Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

, and Giacomo Meyerbeer

Giacomo Meyerbeer (born Jakob Liebmann Beer; 5 September 1791 – 2 May 1864) was a German opera composer, "the most frequently performed opera composer during the nineteenth century, linking Mozart and Wagner". With his 1831 opera ''Robert le di ...

, but in his letters expresses his frank disapproval of their works, for example writing of Liszt that his compositions were "inferior to his playing, and ��only calculated for virtuosos"; of Berlioz's overture ''Les francs-juges

''Les francs-juges'' (translated as "The Free Judges" or "The Judges of the Secret Court") is the title of an unfinished opera by the French composer Hector Berlioz written to a libretto by his friend Humbert Ferrand in 1826. Berlioz abandoned the ...

'' " e orchestration is such a frightful muddle ..that one ought to wash one's hands after handling one of his scores"; and of Meyerbeer's opera ''Robert le diable

''Robert le diable'' (''Robert the Devil'') is an opera in five acts composed by Giacomo Meyerbeer between 1827 and 1831, to a libretto written by Eugène Scribe and Germain Delavigne. ''Robert le diable'' is regarded as one of the first grand o ...

'' "I consider it ignoble", calling its villain Bertram "a poor devil". When his friend the composer Ferdinand Hiller

Ferdinand (von) Hiller (24 October 1811 – 11 May 1885) was a German composer, Conductor (music), conductor, pianist, writer and music director.

Biography

Ferdinand Hiller was born to a wealthy Jewish family in Frankfurt am Main, where his fat ...

suggested in conversation to Mendelssohn that he looked rather like Meyerbeer – they were actually distant cousins, both descendants of Rabbi Moses Isserles

). He is not to be confused with Meir Abulafia, known as "Ramah" ( he, רמ״ה, italic=no, links=no), nor with Menahem Azariah da Fano, known as "Rema MiPano" ( he, רמ״ע מפאנו, italic=no, links=no).

Rabbi Moses Isserles ( he, משה � ...

– Mendelssohn was so upset that he immediately went to get a haircut to differentiate himself.

In particular, Mendelssohn seems to have regarded Paris and its music with the greatest of suspicion and an almost puritanical distaste. Attempts made during his visit there to interest him in Saint-Simonianism

Saint-Simonianism was a French political, religious and social movement of the first half of the 19th century, inspired by the ideas of Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825).

Saint-Simon's ideas, expressed largely through a ...

ended in embarrassing scenes. It is significant that the only musician with whom Mendelssohn remained a close personal friend, Ignaz Moscheles, was of an older generation and equally conservative in outlook. Moscheles preserved this conservative attitude at the Leipzig Conservatory until his own death in 1870.

Marriage and children

Mendelssohn married Cécile Charlotte Sophie Jeanrenaud (10 October 1817 – 25 September 1853), the daughter of a French Reformed Church clergyman, on 28 March 1837. The couple had five children: Carl, Marie, Paul, Lili and Felix August. The second youngest child, Felix August, contracted

Mendelssohn married Cécile Charlotte Sophie Jeanrenaud (10 October 1817 – 25 September 1853), the daughter of a French Reformed Church clergyman, on 28 March 1837. The couple had five children: Carl, Marie, Paul, Lili and Felix August. The second youngest child, Felix August, contracted measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

in 1844 and was left with impaired health; he died in 1851. The eldest, Carl Mendelssohn Bartholdy (7 February 1838 – 23 February 1897), became a historian, and Professor of History at Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: ''Heidlberg'') is a city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914 ...

and Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau (; abbreviated as Freiburg i. Br. or Freiburg i. B.; Low Alemannic: ''Friburg im Brisgau''), commonly referred to as Freiburg, is an independent city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With a population of about 230,000 (as o ...

universities; he died in a psychiatric institution in Freiburg aged 59. Paul Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Paul Mendelssohn Bartholdy (born Paul Felix Abraham Mendelssohn Bartholdy; 18 January 1841, Leipzig – 17 February 1880, Berlin) was a German chemist and a pioneer in the manufacture of aniline dye. He co-founded the Aktien-Gesellschaft für Ani ...

(1841–1880) was a noted chemist and pioneered the manufacture of aniline

Aniline is an organic compound with the formula C6 H5 NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is the simplest aromatic amine

In organic chemistry, an aromatic amine is an organic compound consisting of an aroma ...

dye. Marie married Victor Benecke and lived in London. Lili married Adolf Wach

Eduard Gustav Ludwig Adolph Wach, known as Adolf Wach (11 September 1843 – 4 April 1926) was a German jurist, a professor in Königsberg, Rostock, Tübingen, Bonn and Leipzig.

Biography

Wach was born in Chełmno, Kulm, West Prussia, Kingdom of ...

, later Professor of Law at Leipzig University

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December ...

.

The family papers inherited by Marie's and Lili's children form the basis of the extensive collection of Mendelssohn manuscripts, including the so-called "Green Books" of his correspondence, now in the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second- ...

at Oxford University. Cécile Mendelssohn Bartholdy died less than six years after her husband, on 25 September 1853.

Jenny Lind

Mendelssohn became close to the Swedish sopranoJenny Lind

Johanna Maria "Jenny" Lind (6 October 18202 November 1887) was a Swedish opera singer, often called the "Swedish Nightingale". One of the most highly regarded singers of the 19th century, she performed in soprano roles in opera in Sweden and a ...

, whom he met in October 1844. Papers confirming their relationship had not been made public.Duchen, Jessica"Conspiracy of Silence: Could the Release of Secret Documents Shatter Felix Mendelssohn's Reputation?"

''

The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publis ...

'', 12 January 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2014 In 2013, George Biddlecombe confirmed in the ''Journal of the Royal Musical Association

''Journal of the Royal Musical Association'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal covering fields ranging from historical and critical musicology to theory and analysis, ethnomusicology, and popular music studies. The journal is published by Routl ...

'' that "The Committee of the Mendelssohn Scholarship

The Mendelssohn Scholarship (german: Mendelssohn-Stipendium) refers to two scholarships awarded in Germany and in the United Kingdom. Both commemorate the composer Felix Mendelssohn, and are awarded to promising young musicians to enable them to co ...

Foundation possesses material indicating that Mendelssohn wrote passionate love letters to Jenny Lind entreating her to join him in an adulterous relationship and threatening suicide as a means of exerting pressure upon her, and that these letters were destroyed on being discovered after her death."

Mendelssohn met and worked with Lind many times, and started an opera, ''Lorelei'', for her, based on the legend of the Lorelei

The Lorelei ( ; ), spelled Loreley in German, is a , steep slate rock on the right bank of the River Rhine in the Rhine Gorge (or Middle Rhine) at Sankt Goarshausen in Germany, part of the Upper Middle Rhine Valley UNESCO World Heritage Site. Th ...

Rhine maidens; the opera was unfinished at his death. He is said to have tailored the aria "Hear Ye Israel", in his oratorio ''Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My God is Yahweh/YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) was, according to the Books of ...

'', to Lind's voice, although she did not sing the part until after his death, at a concert in December 1848. In 1847, Mendelssohn attended a London performance of Meyerbeer's ''Robert le diable'' – an opera that musically he despised – in order to hear Lind's British debut, in the role of Alice. The music critic Henry Chorley

Henry Fothergill Chorley (15 December 1808 – 16 February 1872) was an English literary, art and music critic, writer and editor. He was also an author of novels, drama, poetry and lyrics.

Chorley was a prolific and important music and litera ...

, who was with him, wrote: "I see as I write the smile with which Mendelssohn, whose enjoyment of Mdlle. Lind's talent was unlimited, turned round and looked at me, as if a load of anxiety had been taken off his mind. His attachment to Mdlle. Lind's genius as a singer was unbounded, as was his desire for her success."

Upon Mendelssohn's death, Lind wrote: "e was

E, or e, is the fifth letter and the second vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''e'' (pronounced ); plu ...

the only person who brought fulfillment to my spirit, and almost as soon as I found him I lost him again." In 1849, she established the Mendelssohn Scholarship Foundation, which makes an award to a young resident British composer every two years in Mendelssohn's memory. The first winner of the scholarship, in 1856, was Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 comic opera, operatic Gilbert and Sullivan, collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinaf ...

, then aged 14. In 1869, Lind erected a plaque in Mendelssohn's memory at his birthplace in Hamburg.

Music

Composer

Style

Something of Mendelssohn's intense attachment to his personal vision of music is conveyed in his comments to a correspondent who suggested converting some of the ''

Something of Mendelssohn's intense attachment to his personal vision of music is conveyed in his comments to a correspondent who suggested converting some of the ''Songs Without Words

''Songs Without Words'' (') is a series of short lyrical piano works by the Romantic composer Felix Mendelssohn written between 1829 and 1845. His sister, Fanny Mendelssohn, and other composers also wrote pieces in the same genre.

Music

The ...

'' into lied

In Western classical music tradition, (, plural ; , plural , ) is a term for setting poetry to classical music to create a piece of polyphonic music. The term is used for any kind of song in contemporary German, but among English and French s ...

er by adding texts: "What hemusic I love expresses to me, are not thoughts that are too ''indefinite'' for me to put into words, but on the contrary, too ''definite''."