Naples ( ; ; ) is the

regional

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as areas, zones, lands or territories, are portions of the Earth's surface that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and ...

capital of

Campania

Campania is an administrative Regions of Italy, region of Italy located in Southern Italy; most of it is in the south-western portion of the Italian Peninsula (with the Tyrrhenian Sea to its west), but it also includes the small Phlegraean Islan ...

and the third-largest city of

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, after

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

and

Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its

province-level municipality is the third most populous

metropolitan city in Italy with a population of 2,958,410 residents,

and the

eighth most populous in the European Union.

Its metropolitan area stretches beyond the boundaries of the city wall for approximately . Naples also plays a key role in international diplomacy, since it is home to

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

's

Allied Joint Force Command Naples

The Joint Force Command Naples (JFC Naples) is a NATO military command based in Lago Patria, in the Metropolitan City of Naples, Italy. It was activated on 15 March 2004, after effectively redesigning its predecessor command, Allied Forces Southe ...

and the

Parliamentary Assembly of the Mediterranean

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Mediterranean (PAM) is an international organization established in 2005 by the national parliaments of the countries of the Euro-Mediterranean region. It is the legal successor of the Conference on Security and ...

.

Founded by Greeks in the

first millennium

File:1st millennium montage.png, From top left, clockwise: Depiction of Jesus, the central figure in Christianity; The Colosseum, a landmark of the once-mighty Roman Empire; Kaaba, the Great Mosque of Mecca, the holiest site of Islam; Chess, a ne ...

BC, Naples is one of the oldest continuously inhabited urban areas in the world. In the eighth century BC, a colony known as Parthenope () was established on the Pizzofalcone hill. In the sixth century BC, it was refounded as Neápolis. The city was an important part of

Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

, played a major role in the merging of Greek and

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

society, and was a significant cultural centre under the Romans.

Naples served as the capital of the

Duchy of Naples

The Duchy of Naples (, ) began as a Byzantine province that was constituted in the seventh century, in the lands roughly corresponding to the current province of Naples that the Lombards had not conquered during their invasion of Italy in the si ...

(661–1139), subsequently as the capital of the

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

(1282–1816), and finally as the capital of the

Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies () was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1861 under the control of the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, a cadet branch of the House of Bourbon, Bourbons. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by popula ...

— until the

unification of Italy

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century Political movement, political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, annexation of List of historic states of ...

in 1861. Naples is also considered a capital of the

Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

, beginning with the artist

Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (also Michele Angelo Merigi or Amerighi da Caravaggio; 29 September 1571 – 18 July 1610), known mononymously as Caravaggio, was an Italian painter active in Rome for most of his artistic life. During the fina ...

's career in the 17th century and the artistic revolution he inspired. It was also an important centre of

humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

and

Enlightenment. The city has long been a global point of reference for classical music and opera through the

Neapolitan School. Between 1925 and 1936, Naples was expanded and upgraded by the

Fascist regime. During the later years of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, it sustained

severe damage from Allied bombing as they invaded the peninsula. The city underwent extensive reconstruction work after the war.

Since the late 20th century, Naples has had significant economic growth, helped by the construction of the

Centro Direzionale business district and an advanced transportation network, which includes the

Alta Velocità high-speed rail link to Rome and

Salerno

Salerno (, ; ; ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Campania, southwestern Italy, and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after Naples. It is located ...

and an expanded

subway network. Naples is the third-largest urban economy in Italy by GDP, after Milan and Rome. The

Port of Naples

The Port of Naples, a port located on the Western coast of Italy, is the 11th largest seaport in Italy having an annual traffic capacity of around 25 million tons of cargo and 500,000 Twenty-foot equivalent unit, TEU's. It is also serves as a tour ...

is one of the most important in Europe.

Naples' historic city centre has been designated as a UNESCO

World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

. A wide range of culturally and historically significant sites are nearby, including the

Palace of Caserta

The Royal Palace of Caserta ( ; ) is a former royal residence in Caserta, Campania, north of Naples in southern Italy, constructed by the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies as their main residence as Kingdom of Naples, kings of Naples. The complex ...

and the Roman ruins of

Pompeii

Pompeii ( ; ) was a city in what is now the municipality of Pompei, near Naples, in the Campania region of Italy. Along with Herculaneum, Stabiae, and Villa Boscoreale, many surrounding villas, the city was buried under of volcanic ash and p ...

and

Herculaneum

Herculaneum is an ancient Rome, ancient Roman town located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under a massive pyroclastic flow in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Like the nearby city of ...

. Naples is undoubtedly one of the world's cities with the highest density of cultural, artistic, and monumental resources, described by the BBC as "the Italian city with too much history to handle."

History

Greek birth and Roman acquisition

Naples has been inhabited since the

Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

period. In the second millennium BC, a first

Mycenaean settlement arose not far from the geographical position of the future city of Parthenope.

Sailors from the Greek island of

Rhodes

Rhodes (; ) is the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece and is their historical capital; it is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, ninth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Administratively, the island forms a separ ...

established probably a small commercial port called

Parthenope (, meaning "Pure Eyes", a Siren in

Greek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of ancient Greek folklore, today absorbed alongside Roman mythology into the broader designation of classical mythology. These stories conc ...

) on the

island of Megaride in the ninth century BC. By the eighth century BC, the settlement was expanded by

Cumaeans, as evidenced by the archaeological findings, to include Monte Echia. In the sixth century BC the city was refounded as Neápolis (), eventually becoming one of the foremost cities of

Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

.

The city grew rapidly due to the influence of the powerful Greek

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

of

Syracuse,

and became an ally of the

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

against

Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

. During the

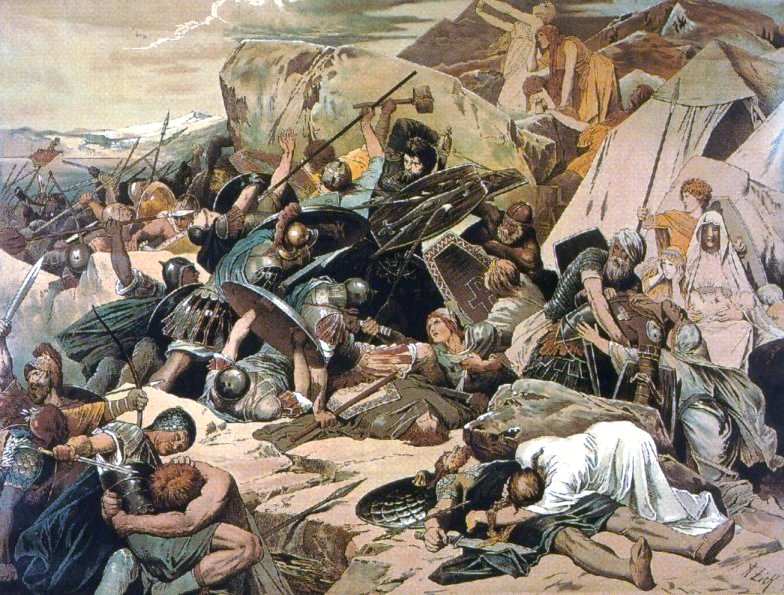

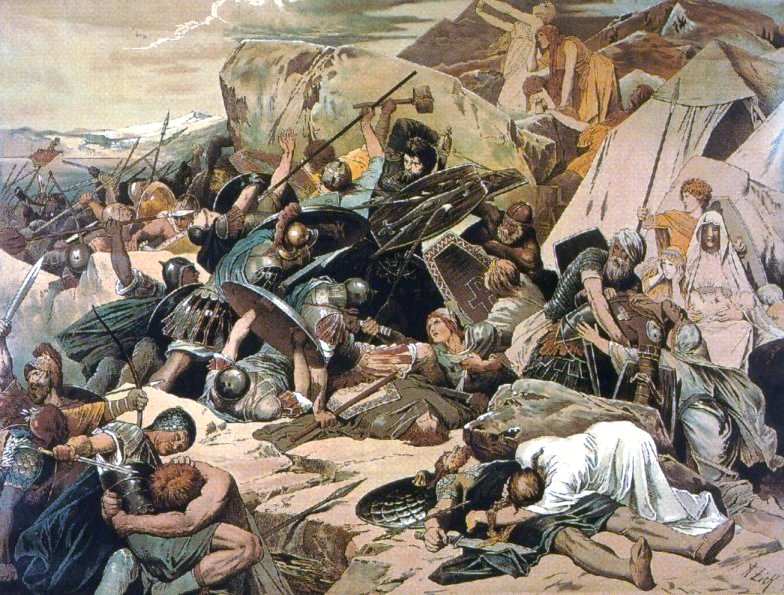

Samnite Wars

The First, Second, and Third Samnite Wars (343–341 BC, 326–304 BC, and 298–290 BC) were fought between the Roman Republic and the Samnites, who lived on a stretch of the Apennine Mountains south of Rome and north of the Lucanian tribe.

...

, the city, now a bustling centre of trade, was

captured by the

Samnites

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic peoples, Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan language, Oscan-speaking Osci, people, who originated as an offsh ...

; however, the Romans soon captured the city from them and made it a

Roman colony

A Roman (: ) was originally a settlement of Roman citizens, establishing a Roman outpost in federated or conquered territory, for the purpose of securing it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It ...

.

During the

Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Ancient Carthage, Carthaginian Empire during the period 264 to 146BC. Three such wars took place, involving a total of forty-three years of warfare on both land and ...

, the strong walls surrounding Neápolis repelled the invading forces of the Carthaginian general

Hannibal

Hannibal (; ; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Punic people, Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Ancient Carthage, Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Punic War.

Hannibal's fat ...

.

The Romans greatly respected Naples as a paragon of

Hellenistic culture

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the Ro ...

. During the Roman era, the people of Naples maintained their

Greek language

Greek (, ; , ) is an Indo-European languages, Indo-European language, constituting an independent Hellenic languages, Hellenic branch within the Indo-European language family. It is native to Greece, Cyprus, Italy (in Calabria and Salento), south ...

and customs. At the same time, the city was expanded with elegant Roman

villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house that provided an escape from urban life. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the f ...

s,

aqueducts, and

public baths

Public baths originated when most people in population centers did not have access to private bathing facilities. Though termed "public", they have often been restricted according to gender, religious affiliation, personal membership, and other cr ...

. Landmarks such as the

Temple of Dioscures were built, and many emperors chose to holiday in the city, including

Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; ; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54), or Claudius, was a Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusus and Ant ...

and

Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus ( ; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was Roman emperor from AD 14 until 37. He succeeded his stepfather Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC to Roman politician Tiberius Cl ...

.

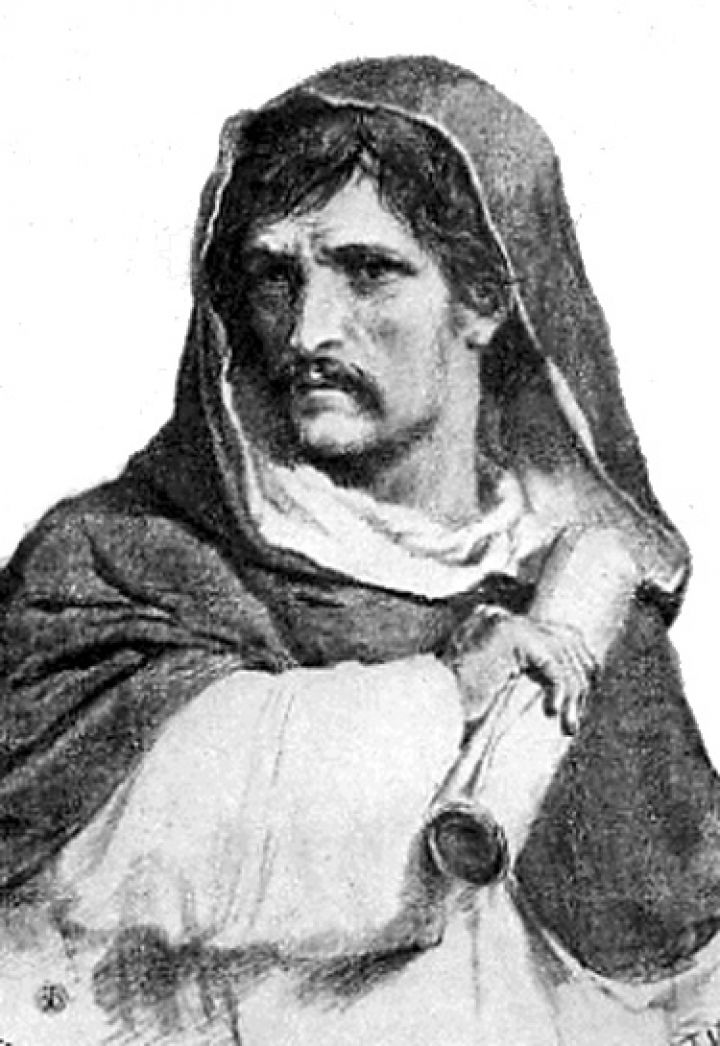

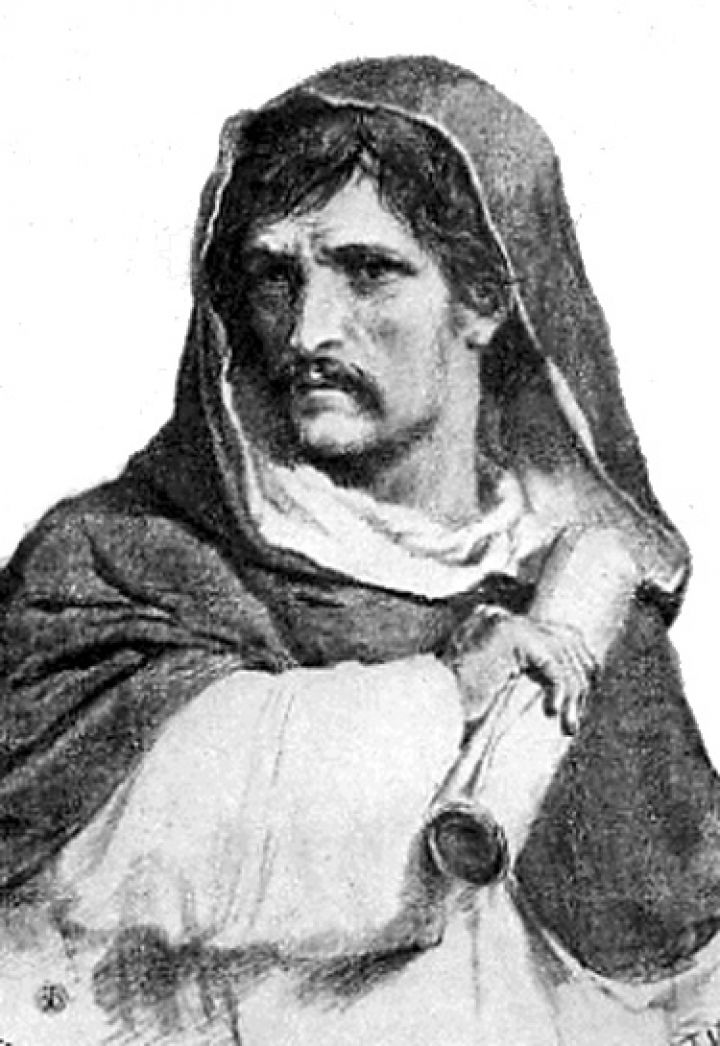

Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

, the author of Rome's

national epic

A national epic is an epic poem or a literary work of epic scope which seeks to or is believed to capture and express the essence or spirit of a particular nation—not necessarily a nation state, but at least an ethnic or linguistic group wi ...

, the ''

Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

'', received part of his education in the city, and later resided in its environs.

It was during this period that Christianity first arrived in Naples; the

apostles Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a su ...

and

Paul

Paul may refer to:

People

* Paul (given name), a given name, including a list of people

* Paul (surname), a list of people

* Paul the Apostle, an apostle who wrote many of the books of the New Testament

* Ray Hildebrand, half of the singing duo ...

are said to have preached in the city.

Januarius

Januarius ( ; ; Neapolitan and ), also known as , was Bishop of Benevento and is a martyr and saint of the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, and Armenian Apostolic Church. While no contemporary sources on his life are preserved, later ...

, who would become Naples'

patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy or Oriental Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, fa ...

, was

martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

ed there in the fourth century AD.

The last emperor of the

Western Roman Empire

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

,

Romulus Augustulus

Romulus Augustus (after 511), nicknamed Augustulus, was Roman emperor of the Western Roman Empire, West from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. Romulus was placed on the imperial throne while still a minor by his father Orestes (father of Ro ...

, was exiled to Naples by the Germanic king

Odoacer

Odoacer ( – 15 March 493 AD), also spelled Odovacer or Odovacar, was a barbarian soldier and statesman from the Middle Danube who deposed the Western Roman child emperor Romulus Augustulus and became the ruler of Italy (476–493). Odoacer' ...

in the fifth century AD.

Duchy of Naples

Following the decline of the

Western Roman Empire

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

, Naples was captured by the

Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths () were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Western Roman Empire, drawing upon the large Gothic populatio ...

, a

Germanic people

The Germanic peoples were tribal groups who lived in Northern Europe in Classical antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. In modern scholarship, they typically include not only the Roman-era ''Germani'' who lived in both ''Germania'' and parts of ...

, and incorporated into the

Ostrogothic Kingdom

The Ostrogothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of Italy (), was a barbarian kingdom established by the Germanic Ostrogoths that controlled Italian peninsula, Italy and neighbouring areas between 493 and 553. Led by Theodoric the Great, the Ost ...

.

However,

Belisarius

BelisariusSometimes called Flavia gens#Later use, Flavius Belisarius. The name became a courtesy title by the late 4th century, see (; ; The exact date of his birth is unknown. March 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under ...

of the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

recaptured Naples in 536, after entering the city via an aqueduct.

In 543, during the

Gothic Wars,

Totila

Totila, original name Baduila (died 1 July 552), was the penultimate King of the Ostrogoths, reigning from 541 to 552 AD. A skilled military and political leader, Totila reversed the tide of the Gothic War (535–554), Gothic War, recovering b ...

briefly took the city for the Ostrogoths, but the Byzantines seized control of the area following the

Battle of Mons Lactarius on the slopes of

Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ) is a Somma volcano, somma–stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of several volcanoes forming the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuv ...

.

Naples was expected to keep in contact with the

Exarchate of Ravenna

The Exarchate of Ravenna (; ), also known as the Exarchate of Italy, was an administrative district of the Byzantine Empire comprising, between the 6th and 8th centuries, the territories under the jurisdiction of the exarch of Italy (''exarchus ...

, which was the centre of Byzantine power on the

Italian Peninsula.

After the

exarch

An exarch (;

from Ancient Greek ἔξαρχος ''exarchos'') was the holder of any of various historical offices, some of them being political or military and others being ecclesiastical.

In the late Roman Empire and early Byzantine Empire, ...

ate fell, a

Duchy of Naples

The Duchy of Naples (, ) began as a Byzantine province that was constituted in the seventh century, in the lands roughly corresponding to the current province of Naples that the Lombards had not conquered during their invasion of Italy in the si ...

was created. Although Naples'

Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman world , also Greco-Roman civilization, Greco-Roman culture or Greco-Latin culture (spelled Græco-Roman or Graeco-Roman in British English), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and co ...

culture endured, it eventually switched allegiance from

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

to Rome under Duke

Stephen II, putting it under

papal

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the pope was the sovereign or head of sta ...

suzerainty

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy">polity.html" ;"title="state (polity)">state or polity">state (polity)">st ...

by 763.

The years between 818 and 832 saw tumultuous relations with the

Byzantine Emperor

The foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, which Fall of Constantinople, fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as legitimate rulers and exercised s ...

, with numerous local pretenders feuding for possession of the ducal throne.

was appointed without imperial approval; his appointment was later revoked and

Theodore II took his place. However, the disgruntled general populace chased him from the city and elected

Stephen III instead, a man who minted coins with his initials rather than those of the Byzantine Emperor. Naples gained complete independence by the early ninth century.

Naples allied with the Muslim

Saracens

file:Erhard Reuwich Sarazenen 1486.png, upright 1.5, Late 15th-century History of Germany, German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek language, Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to ...

in 836 and asked for their support to repel the siege of

Lombard troops coming from the neighbouring

Duchy of Benevento

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a country, territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important difference between "sovereign ...

. However, during the 850s, Muslim general

Muhammad I Abu 'l-Abbas

Abu'l-Abbas Muhammad I ibn al-Aghlab () (died 856) was the fifth emir of the Aghlabids, Aghlabid dynasty, who ruled over Ifriqiya, Islam in Malta, Malta, and most of Sicily from 841 until his death. He also led the Arab raid against Rome, raid of ...

sacked

Miseno, but only for

Khums purposes (Islamic booty), without conquering the territories of

Campania

Campania is an administrative Regions of Italy, region of Italy located in Southern Italy; most of it is in the south-western portion of the Italian Peninsula (with the Tyrrhenian Sea to its west), but it also includes the small Phlegraean Islan ...

.

The duchy was under the direct control of the

Lombards

The Lombards () or Longobards () were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written betwee ...

for a brief period after the capture by

Pandulf IV of the

Principality of Capua

The Principality of Capua ( or ''Capue'', Modern ) was a Lombards, Lombard state centred on Capua in Southern Italy. Towards the end of the 10th century the Principality reached its apogee, occupying most of the Terra di Lavoro area. It was ori ...

, a long-term rival of Naples; however, this regime lasted only three years before the Greco-Roman-influenced dukes were reinstated.

By the 11th century, Naples had begun to employ

Norman mercenaries

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an War, armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rath ...

to battle their rivals; Duke

Sergius IV hired

Rainulf Drengot to wage war on Capua for him.

By 1137, the Normans had attained great influence in Italy, controlling previously independent principalities and duchies such as

Capua

Capua ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Caserta, in the region of Campania, southern Italy, located on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain.

History Ancient era

The name of Capua comes from the Etruscan ''Capeva''. The ...

,

Benevento

Benevento ( ; , ; ) is a city and (municipality) of Campania, Italy, capital of the province of Benevento, northeast of Naples. It is situated on a hill above sea level at the confluence of the Calore Irpino (or Beneventano) and the Sabato (r ...

,

Salerno

Salerno (, ; ; ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Campania, southwestern Italy, and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after Naples. It is located ...

,

Amalfi

Amalfi (, , ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Salerno, in the region of Campania, Italy, on the Gulf of Salerno. It lies at the mouth of a deep ravine, at the foot of Monte Cerreto (1,315 metres, 4,314 feet), surrounded by dramatic c ...

,

Sorrento

Sorrento ( , ; ; ) is a City status in Italy, city and overlooking the Gulf of Naples, Bay of Naples in Southern Italy. A popular tourist destination, Sorrento is located on the Sorrentine Peninsula at the southern terminus of a main branch o ...

and

Gaeta

Gaeta (; ; Southern Latian dialect, Southern Laziale: ''Gaieta'') is a seaside resort in the province of Latina in Lazio, Italy. Set on a promontory stretching towards the Gulf of Gaeta, it is from Rome and from Naples.

The city has played ...

; it was in this year that Naples, the last independent duchy in the southern part of the peninsula, came under Norman control. The last ruling duke of the duchy,

Sergius VII, was forced to surrender to

Roger II

Roger II or Roger the Great (, , Greek: Ρογέριος; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Sicily and Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily and successor to his brother Simon. He began his rule as Count of Sicily in 1105, became ...

, who had been proclaimed

King of Sicily

The monarchs of Sicily ruled from the establishment of the Kingdom of Sicily in 1130 until the "perfect fusion" in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1816.

The origins of the Sicilian monarchy lie in the Norman conquest of southern Italy which oc ...

by

Antipope Anacletus II

Anacletus II (died January 25, 1138), born Pietro Pierleoni, was an antipope who ruled in opposition to Pope Innocent II from 1130 until his death in 1138. After the death of Pope Honorius II, the college of Cardinal (Catholic Church), cardinals ...

seven years earlier. Naples thus joined the

Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

, with

Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

as the capital.

As part of the Kingdom of Sicily

After a period of

Norman rule, in 1189, the

Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

was in a succession dispute between

Tancred, King of Sicily

Tancred (; 113820 February 1194) was King of Sicily from 1189 to 1194. He was born in Lecce, an illegitimate son of Roger III, Duke of Apulia (the eldest son of King Roger II) by his mistress Emma, a daughter of Achard II, Count of Lecce. ...

of an illegitimate birth and the

Hohenstaufens, a Germanic

royal house

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family, usually in the context of a monarchy, monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A dynasty may also be referred to as a "house", "family" or "clan", among others.

H ...

, as its Prince Henry had married

Princess Constance the last legitimate heir to the Sicilian throne. In 1191 Henry invaded Sicily after being crowned as

Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor

Henry VI (German language, German: ''Heinrich VI.''; November 1165 – 28 September 1197), a member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, was King of Germany (King of the Romans) from 1169 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1191 until his death. From 1194 he was ...

, and many cities surrendered. Still, Naples resisted him from May to August under the leadership of

Richard, Count of Acerra

Richard, count of Acerra (died 30 November 1196) was an Italo-Norman nobleman, grandson of Robert of Medania, a Frenchman of County of Anjou, Anjou. Brother of Sibylla of Acerra, Sibylla, queen of Tancred of Sicily, Richard was the chief peninsular ...

,

Nicholas of Ajello,

Aligerno Cottone and

Margaritus of Brindisi

Margaritus of Brindisi (also Margarito; Italian language, Italian: ''Margaritone'', Greek language, Greek: ''Megareites'' or ''Margaritoni'' �αργαριτώνη c. 1149 – 1197), called "the new Neptune", was the last great ''ammiratus ...

before the Germans suffered from disease and were forced to retreat.

Conrad II, Duke of Bohemia and

Philip I, Archbishop of Cologne

Philip I () (c. 1130 – 13 August 1191) was Archbishop of Cologne and Archchancellor of Italy from 1167 to 1191.

He was the son of Count Goswin II of Heinsberg and Adelaide of Sommerschenburg. He received his ecclesiastical training in Cologne an ...

died of disease during

the siege. During his counterattack,

Tancred captured Constance, now empress. He had the empress imprisoned at

Castel dell'Ovo at Naples before her release on May 1192 under the pressure of

Pope Celestine III

Pope Celestine III (; c. 1105 – 8 January 1198), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 March or 10 April 1191 to his death in 1198. He had a tense relationship with several monarchs, including Emperor ...

. In 1194 Henry started his second campaign upon the death of Tancred, but this time Aligerno surrendered without resistance, and finally, Henry conquered Sicily, putting it under the rule of Hohenstaufens.

The

University of Naples

The University of Naples Federico II (; , ) is a public university, public research university in Naples, Campania, Italy. Established in 1224 and named after its founder, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, it is the oldest public, s ...

, the first university in Europe dedicated to training secular administrators, was founded by

Frederick II, making Naples the intellectual centre of the kingdom. Conflict between the Hohenstaufens and the

Papacy

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

led in 1266 to

Pope Innocent IV

Pope Innocent IV (; – 7 December 1254), born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 June 1243 to his death in 1254.

Fieschi was born in Genoa and studied at the universities of Parma and Bolo ...

crowning the

Angevin duke

Charles I King of Sicily:

Charles officially moved the capital from Palermo to Naples, where he resided at the

Castel Nuovo. Having a great interest in architecture, Charles I imported French architects and workmen and was personally involved in several building projects in the city. Many examples of

Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High Middle Ages, High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It evolved f ...

sprang up around Naples, including the

Naples Cathedral

The Naples Cathedral (; ), or the Cathedral of the Assumption of Mary (), is a Roman Catholic cathedral, the main church of Naples, southern Italy, and the seat of the Archbishop of Naples. It is widely known as the Cathedral of Saint Januarius ...

, which remains the city's main church.

Kingdom of Naples

In 1282, after the

Sicilian Vespers

The Sicilian Vespers (; ) was a successful rebellion on the island of Sicily that broke out at Easter 1282 against the rule of the French-born king Charles I of Anjou. Since taking control of the Kingdom of Sicily in 1266, the Capetian House ...

, the Kingdom of Sicily was divided into two. The Angevin

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

included the southern part of the Italian peninsula, while the island of

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

became the

Aragonese Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

.

Wars between the competing dynasties continued until the

Peace of Caltabellotta

The Peace of Caltabellotta, signed on 31 August 1302, was the last of a series of treaties, including those of Treaty of Tarascon, Tarascon and Treaty of Anagni, Anagni, designed to end the War of the Sicilian Vespers between the Houses of Capetia ...

in 1302, which saw

Frederick III recognised as king of Sicily, while

Charles II was recognised as king of Naples by

Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII (; born Benedetto Caetani; – 11 October 1303) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 until his death in 1303. The Caetani, Caetani family was of baronial origin with connections t ...

.

Despite the split, Naples grew in importance, attracting

Pisan

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning To ...

and

Genoese merchants,

Tuscan bankers, and some of the most prominent

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

artists of the time, such as

Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio ( , ; ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was s ...

,

Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

and

Giotto

Giotto di Bondone (; – January 8, 1337), known mononymously as Giotto, was an List of Italian painters, Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages. He worked during the International Gothic, Gothic and Italian Ren ...

. During the 14th century, the Hungarian Angevin king

Louis the Great captured the city several times. In 1442,

Alfonso I conquered Naples after his victory against the last

Angevin king,

René, and Naples was unified with Sicily again for a brief period.

Aragonese and Spanish

Sicily and Naples were separated since 1282, but remained dependencies of

Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and ; ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces of Spain, ...

under

Ferdinand I. The new dynasty enhanced Naples' commercial standing by establishing relations with the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

. Naples also became a centre of the Renaissance, with artists such as

Laurana,

da Messina,

Sannazzaro and

Poliziano

Agnolo (or Angelo) Ambrogini (; 14 July 1454 – 24 September 1494), commonly known as Angelo Poliziano () or simply Poliziano, anglicized as Politian, was an Italian classical scholar and poet of the Florentine Renaissance. His scholars ...

arriving in the city. In 1501, Naples came under direct rule from

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

under

Louis XII

Louis XII (27 June 14621 January 1515), also known as Louis of Orléans was King of France from 1498 to 1515 and King of Naples (as Louis III) from 1501 to 1504. The son of Charles, Duke of Orléans, and Marie of Cleves, he succeeded his second ...

, with the Neapolitan king

Frederick Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Given name

Nobility

= Anhalt-Harzgerode =

* Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

= Austria =

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria fro ...

being taken as a prisoner to France; however, this state of affairs did not last long, as Spain won Naples from the French at the

Battle of Garigliano in 1503.

Following the Spanish victory, Naples became part of the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

, and remained so throughout the

Spanish Habsburg

Habsburg Spain refers to Spain and the Hispanic Monarchy, also known as the Catholic Monarchy, in the period from 1516 to 1700 when it was ruled by kings from the House of Habsburg. In this period the Spanish Empire was at the zenith of its in ...

period.

The Spanish sent

viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory.

The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the Anglo-Norman ''roy'' (Old Frenc ...

s

to Naples to directly deal with local issues: the most important of these viceroys was

Pedro Álvarez de Toledo, who was responsible for considerable social, economic and urban reforms in the city; he also tried to introduce the

Inquisition

The Inquisition was a Catholic Inquisitorial system#History, judicial procedure where the Ecclesiastical court, ecclesiastical judges could initiate, investigate and try cases in their jurisdiction. Popularly it became the name for various med ...

. In 1544, around 7,000 people were taken as

slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

by

Barbary pirates

The Barbary corsairs, Barbary pirates, Ottoman corsairs, or naval mujahideen (in Muslim sources) were mainly Muslim corsairs and privateers who operated from the largely independent Barbary states. This area was known in Europe as the Barba ...

and brought to the

Barbary Coast

The Barbary Coast (also Barbary, Berbery, or Berber Coast) were the coastal regions of central and western North Africa, more specifically, the Maghreb and the Ottoman borderlands consisting of the regencies in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, a ...

of North Africa (see

Sack of Naples

The sack of Naples occurred in 1544 when Algerians captured the Bay of Naples and enslaved 7,000 Neapolitans.

In 1544 Algerian corsairs sailed into the Bay of Naples and captured it. They then took an estimated 7,000 Neapolitan slaves. ).

By the 17th century, Naples had become Europe's second-largest city – second only to Paris – and the largest European Mediterranean city, with around 250,000 inhabitants. The city was a major cultural centre during the

Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

era, being home to artists such as

Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (also Michele Angelo Merigi or Amerighi da Caravaggio; 29 September 1571 – 18 July 1610), known mononymously as Caravaggio, was an Italian painter active in Rome for most of his artistic life. During the fina ...

,

Salvator Rosa and

Bernini

Gian Lorenzo (or Gianlorenzo) Bernini (, ; ; Italian Giovanni Lorenzo; 7 December 1598 – 28 November 1680) was an Italian sculptor and architect. While a major figure in the world of architecture, he was more prominently the leading sculptor ...

, philosophers such as

Bernardino Telesio

Bernardino Telesio (; 7 November 1509 – 2 October 1588) was an Italian philosopher and natural scientist. While his natural theories were later disproven, his emphasis on observation made him the "first of the moderns" who eventually deve ...

,

Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno ( , ; ; born Filippo Bruno; January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, poet, alchemist, astrologer, cosmological theorist, and esotericist. He is known for his cosmological theories, which concep ...

,

Tommaso Campanella

Tommaso Campanella (; 5 September 1568 – 21 May 1639), baptized Giovanni Domenico Campanella, was an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, theologian, astrologer, and poet.

Campanella was prosecuted by the Roman Inquisition for he ...

and

Giambattista Vico

Giambattista Vico (born Giovan Battista Vico ; ; 23 June 1668 – 23 January 1744) was an Italian philosopher, rhetorician, historian, and jurist during the Italian Enlightenment. He criticized the expansion and development of modern rationali ...

, and writers such as

Giambattista Marino

Giambattista Marino (also Giovan Battista Marini) (14 October 1569 – 26 March 1625) was a Neapolitan poet who was born in Naples. He is most famous for his epic '.

The ''Cambridge History of Italian Literature'' thought him to be "one of ...

. A revolution led by the local fisherman

Masaniello

Tommaso Aniello (29 June 1620 – 16 July 1647), popularly known by the contracted name Masaniello (, ), was an Italian fisherman who became leader of the 1647 revolt against the rule of Habsburg Spain in the Kingdom of Naples.

Name and place ...

saw the creation of a brief independent

Neapolitan Republic in 1647. However, this lasted only a few months before Spanish rule was reasserted.

In 1656, an outbreak of

bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of Plague (disease), plague caused by the Bacteria, bacterium ''Yersinia pestis''. One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and ...

killed about half of Naples' 300,000 inhabitants.

In 1714, Spanish rule over Naples came to an end as a result of the

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

; the Austrian

Charles VI ruled the city from

Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

through viceroys of his own. However, the

War of the Polish Succession

The War of the Polish Succession (; 1733–35) was a major European conflict sparked by a civil war in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth over the succession to Augustus II the Strong, which the other European powers widened in pursuit of ...

saw the Spanish regain Sicily and Naples as part of a

personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

, with the 1738

Treaty of Vienna recognising the two polities as independent under a cadet branch of the Spanish

Bourbons

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a dynasty that originated in the Kingdom of France as a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. A branch descended from ...

.

In 1755, the Duke of Noja commissioned an accurate topographic map of Naples, later known as the

Map of the Duke of Noja, employing rigorous surveying accuracy and becoming an essential urban planning tool for Naples.

During the time of

Ferdinand IV, the effects of the

French Revolution were felt in Naples:

Horatio Nelson

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte ( – 21 October 1805) was a Royal Navy officer whose leadership, grasp of strategy and unconventional tactics brought about a number of decisive British naval victories during the French ...

, an ally of the Bourbons, arrived in the city in 1798 to warn against the French republicans. Ferdinand was forced to retreat and fled to

Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

, where he was protected by a

British fleet

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from th ...

.

However, Naples'

lower class ''

lazzaroni'' were strongly pious and royalist, favouring the Bourbons; in the that followed, they fought the Neapolitan pro-Republican aristocracy, causing a civil war.

Eventually, the Republicans conquered

Castel Sant'Elmo and proclaimed a

Parthenopaean Republic, secured by the

French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

.

A

counter-revolutionary

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution has occurred, in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "c ...

religious army of ''lazzaroni'' known as the ''

sanfedisti'' under Cardinal

Fabrizio Ruffo was raised; they met with great success, and the French were forced to surrender the Neapolitan castles, with their fleet sailing back to

Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

.

Ferdinand IV was restored as king; however, after only seven years,

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

conquered the kingdom and installed

Bonapartist

Bonapartism () is the political ideology supervening from Napoleon Bonaparte and his followers and successors. The term was used in the narrow sense to refer to people who hoped to restore the House of Bonaparte and its style of government. In ...

kings, including installing his brother

Joseph Bonaparte

Joseph Bonaparte (born Giuseppe di Buonaparte, ; ; ; 7 January 176828 July 1844) was a French statesman, lawyer, diplomat and older brother of Napoleon Bonaparte. During the Napoleonic Wars, the latter made him King of Naples (1806–1808), an ...

.

With the help of the

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

and its allies, the Bonapartists were defeated in the

Neapolitan War

The Neapolitan War, also known as the Austro-Neapolitan War, was a conflict between the Napoleonic Kingdom of Naples (Napoleonic), Kingdom of Naples and the Austrian Empire. It started on 15 March 1815, when King Joachim Murat declared war on ...

. Ferdinand IV once again regained the throne and the kingdom.

Independent Two Sicilies

The

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

in 1815 saw the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily combine to form the

Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies () was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1861 under the control of the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, a cadet branch of the House of Bourbon, Bourbons. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by popula ...

,

with Naples as the capital city. In 1839, Naples became the first city on the Italian Peninsula to have a railway, with the construction of the

Naples–Portici railway.

Italian unification to the present day

After the

Expedition of the Thousand

The Expedition of the Thousand () was an event of the unification of Italy that took place in 1860. A corps of volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi sailed from Quarto al Mare near Genoa and landed in Marsala, Sicily, in order to conquer the Ki ...

led by

Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as (). In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as () or (). 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, revolutionary and republican. H ...

, which culminated in the controversial

siege of Gaeta, Naples became part of the

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

in 1861 as part of the

Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

, ending the era of Bourbon rule. The economy of the area formerly known as the Two Sicilies as dependant on agriculture suffered the international pressure on prices of wheat, and together with lower sea fares prices lead to an unprecedented

wave of emigration,

with an estimated 4 million people emigrating from the Naples area between 1876 and 1913. In the forty years following unification, the population of Naples grew by only 26%, vs. 63% for Turin and 103% for Milan; however, by 1884, Naples was still the largest city in Italy with 496,499 inhabitants, or roughly 64,000 per square kilometre (more than twice the population density of Paris).

Public health conditions in certain areas of the city were poor, with twelve epidemics of

cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

and

typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

claiming some 48,000 people between 1834 and 1884. A

death rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of d ...

31.84 per thousand, high even for the time, insisted in the absence of epidemics between 1878 and 1883. Then in 1884, Naples fell victim to a major

cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

epidemic, caused largely by the city's poor

sewerage

Sewerage (or sewage system) is the infrastructure that conveys sewage or surface runoff ( stormwater, meltwater, rainwater) using sewers. It encompasses components such as receiving drains, manholes, pumping stations, storm overflows, and scr ...

infrastructure. In response to these problems, in 1885, the government prompted a radical transformation of the city called ''

risanamento'' to improve the sewerage infrastructure and replace the most clustered areas, considered the main cause of

insalubrity, with large and airy avenues. The project proved difficult to accomplish politically and economically due to corruption, as shown in the

Saredo Inquiry, land speculation and extremely long bureaucracy. This led to the project to massive delays with contrasting results. The most notable transformations made were the construction of Via Caracciolo in place of the beach along the promenade, the creation of

Galleria Umberto I and

Galleria Principe and the construction of Corso Umberto.

Naples was the

most-bombed Italian city during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Though Neapolitans did not rebel under

Italian Fascism

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

, Naples was the first Italian city to

rise up against German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

military occupation

Military occupation, also called belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is temporary hostile control exerted by a ruling power's military apparatus over a sovereign territory that is outside of the legal boundaries of that ruling pow ...

; for the first time in Europe, the Nazis, whose leader in this case was Colonel Scholl, negotiated a surrender in the face of insurgents. The city was already completely freed by 1 October 1943, when British and American forces entered the city. Departing Germans

burned the library of

the university, as well as the Italian Royal Society. They also destroyed the city archives. Time bombs planted throughout the city continued to explode into November. Departing Germans also "looted all the food and fuel. They blew up the city's gas, water and sewage piping. They destroyed its port facilities ... and scuttled more than 300 ships in the harbor. They destroyed 75% of the major bridges, stole nearly 90% of the city's trucks, buses and trams, demolished railroad tracks and tunnels...."

The symbol of the rebirth of Naples was the rebuilding of the church of

Santa Chiara, which had been destroyed in a

United States Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical ri ...

bombing raid.

Special funding from the Italian government's

Fund for the South was provided from 1950 to 1984, helping the Neapolitan economy to improve somewhat, with city landmarks such as the

Piazza del Plebiscito being renovated. However, high unemployment continues to affect Naples.

Italian media attributed the city's recent

illegal waste disposal issues to the

, the

organized crime

Organized crime is a category of transnational organized crime, transnational, national, or local group of centralized enterprises run to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally thought of as a f ...

network centered in Campania. Due to illegal waste dumping, as exposed by

Roberto Saviano in his book ''

Gomorrah'', severe environmental contamination and increased health risks remain prevalent.

In 2007,

Silvio Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; 29 September 193612 June 2023) was an Italian Media proprietor, media tycoon and politician who served as the prime minister of Italy in three governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a mem ...

's government held senior meetings in Naples to demonstrate their intention to solve these problems. However, the

late-2000s recession

The Great Recession was a period of market decline in economies around the world that occurred from late 2007 to mid-2009. had a severe impact on the city, intensifying its waste-management and unemployment problems. By August 2011, the number of unemployed in the Naples area had risen to 250,000, sparking public protests against the economic situation. In June 2012, allegations of blackmail, extortion, and illicit contract tendering emerged concerning the city's waste management issues.

["Cricca veneta sui rifiuti di Napoli: arrestati i fratelli Gavioli" (in Italian)]

. ''Il Mattino''. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

. ''Il Mattino di Padova''. 21 June 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

Naples hosted the sixth

World Urban Forum in September 2012 and the 63rd

International Astronautical Congress

The International Astronautical Congress (IAC) is an annual meeting of the actors in the discipline of space science.

It is hosted by one of the national society members of the International Astronautical Federation (IAF), with the support of ...

in October 2012. In 2013, it was the host of the

Universal Forum of Cultures and the host for the

2019 Summer Universiade

The 2019 Summer Universiade (), officially known as the XXX Summer Universiade () and also known as Naples 2019, or Napoli 2019, was held in Naples, Italy, between 3 and 14 July 2019.

It was initially scheduled for Brasília, Brazil in July 201 ...

.

Architecture

UNESCO World Heritage Site

Naples' 2,800-year history has left it with a wealth of historical buildings and monuments, from medieval castles to classical ruins, and a wide range of culturally and historically significant sites nearby, including the

Palace of Caserta

The Royal Palace of Caserta ( ; ) is a former royal residence in Caserta, Campania, north of Naples in southern Italy, constructed by the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies as their main residence as Kingdom of Naples, kings of Naples. The complex ...

and the Roman ruins of

Pompeii

Pompeii ( ; ) was a city in what is now the municipality of Pompei, near Naples, in the Campania region of Italy. Along with Herculaneum, Stabiae, and Villa Boscoreale, many surrounding villas, the city was buried under of volcanic ash and p ...

and

Herculaneum

Herculaneum is an ancient Rome, ancient Roman town located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under a massive pyroclastic flow in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Like the nearby city of ...

. In 2017 the

BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

defined Naples as "the Italian city with too much history to handle".

The most prominent forms of architecture visible in present-day Naples are the

Medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

,

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

and

Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

styles. Naples has a total of 448 historical churches (1000 in total), making it one of the most Catholic cities in the world in terms of the number of places of worship.

In 1995, the

historic centre of Naples

The historic center (''Centro Storico'') of Naples, Italy, is the oldest part of the city, with a history that spans over 2,700 years.

Almost the entirety of the historic center, approximately 1021 hectares, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage ...

was listed by

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

as a

World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

, a United Nations programme which aims to catalogue and conserve sites of outstanding cultural or natural importance to the

common heritage of mankind

Common heritage of humanity (also termed the common heritage of mankind, common heritage of humankind or common heritage principle) is a principle of international law that holds the defined territorial areas and elements of humanity's common heri ...

.

Piazzas, palaces and castles

The main city square or ''

piazza

A town square (or public square, urban square, city square or simply square), also called a plaza or piazza, is an open public space commonly found in the heart of a traditional town or city, and which is used for community gatherings. Rela ...

'' of the city is the

Piazza del Plebiscito. Its construction was begun by the

Bonapartist

Bonapartism () is the political ideology supervening from Napoleon Bonaparte and his followers and successors. The term was used in the narrow sense to refer to people who hoped to restore the House of Bonaparte and its style of government. In ...

king

Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also ; ; ; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French Army officer and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the military titles of Marshal of the ...

and finished by the Bourbon king

Ferdinand IV. The piazza is bounded on the east by the

Royal Palace and on the west by the church of

San Francesco di Paola, with the colonnades extending on both sides. Nearby is the

Teatro di San Carlo

The Real Teatro di San Carlo ("Royal Theatre of Saint Charles"), as originally named by the Bourbon monarchy but today known simply as the Teatro (di) San Carlo, is a historic opera house in Naples, Italy, connected to the Royal Palace and ...

, which is the oldest

opera house

An opera house is a theater building used for performances of opera. Like many theaters, it usually includes a stage, an orchestra pit, audience seating, backstage facilities for costumes and building sets, as well as offices for the institut ...

in Italy. Directly across San Carlo is

Galleria Umberto.

Naples is well known for its castles: The most ancient is

Castel dell'Ovo ("Egg Castle"), which was built on the tiny

islet

An islet ( ) is generally a small island. Definitions vary, and are not precise, but some suggest that an islet is a very small, often unnamed, island with little or no vegetation to support human habitation. It may be made of rock, sand and/ ...

of Megarides, where the original

Cumae

Cumae ( or or ; ) was the first ancient Greek colony of Magna Graecia on the mainland of Italy and was founded by settlers from Euboea in the 8th century BCE. It became a rich Roman city, the remains of which lie near the modern village of ...

an colonists had founded the city. In Roman times the islet became part of

Lucullus

Lucius Licinius Lucullus (; 118–57/56 BC) was a Ancient Romans, Roman List of Roman generals, general and Politician, statesman, closely connected with Lucius Cornelius Sulla. In culmination of over 20 years of almost continuous military and ...

's villa, later hosting

Romulus Augustulus

Romulus Augustus (after 511), nicknamed Augustulus, was Roman emperor of the Western Roman Empire, West from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. Romulus was placed on the imperial throne while still a minor by his father Orestes (father of Ro ...

, the exiled last western Roman emperor. It had also been the prison for

Empress Constance between 1191 and 1192 after her being captured by Sicilians, and

Conradin

Conrad III (25 March 1252 – 29 October 1268), called ''the Younger'' or ''the Boy'', but usually known by the diminutive Conradin (, ), was the last direct heir of the House of Hohenstaufen. He was Duke of Swabia (1254–1268) and nominal King ...

and

Giovanna I of Naples

Joanna I, also known as Johanna I (; December 1325 – 27 July 1382), was List of monarchs of Naples, Queen of Naples, and List of rulers of Provence, Countess of Provence and County of Forcalquier, Forcalquier from 1343 to 1381; she was also ...

before their executions.

Castel Nuovo, also known as ''Maschio

Angioino'', is one of the city's top landmarks; it was built during the time of

Charles I, the first

king of Naples

The following is a list of rulers of the Kingdom of Naples, from its first Sicilian Vespers, separation from the Kingdom of Sicily to its merger with the same into the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Kingdom of Naples (1282–1501)

House of Anjou

...

. Castel Nuovo has seen many notable historical events: for example, in 1294,

Pope Celestine V

Pope Celestine V (; 1209/1210 or 1215 – 19 May 1296), born Pietro Angelerio (according to some sources ''Angelario'', ''Angelieri'', ''Angelliero'', or ''Angeleri''), also known as Pietro da Morrone, Peter of Morrone, and Peter Celestine, was ...

resigned as pope in a hall of the castle, and following this

Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII (; born Benedetto Caetani; – 11 October 1303) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 until his death in 1303. The Caetani, Caetani family was of baronial origin with connections t ...

was elected pope by the cardinal

collegium

A (: ) or college was any association in ancient Rome that Corporation, acted as a Legal person, legal entity. Such associations could be civil or religious.

The word literally means "society", from ("colleague"). They functioned as social cl ...

, before moving to Rome.

Castel Capuano was built in the 12th century by

William I William I may refer to:

Kings

* William the Conqueror (–1087), also known as William I, King of England

* William I of Sicily (died 1166)

* William I of Scotland (died 1214), known as William the Lion

* William I of the Netherlands and Luxembour ...

, the son of

Roger II of Sicily

Roger II or Roger the Great (, , Greek language, Greek: Ρογέριος; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Kingdom of Sicily, Sicily and Kingdom of Africa, Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily and successor to his brother Simon, C ...

, the first monarch of the

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

. It was expanded by

Frederick II and became one of his royal palaces. The castle was the residence of many kings and queens throughout its history. In the 16th century, it became the Hall of Justice.

Another Neapolitan castle is

Castel Sant'Elmo, which was completed in 1329 and is built in the shape of a

star

A star is a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by Self-gravitation, self-gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night sk ...

. Its strategic position overlooking the entire city made it a target of various invaders. During the uprising of

Masaniello

Tommaso Aniello (29 June 1620 – 16 July 1647), popularly known by the contracted name Masaniello (, ), was an Italian fisherman who became leader of the 1647 revolt against the rule of Habsburg Spain in the Kingdom of Naples.

Name and place ...

in 1647, the Spanish took refuge in Sant'Elmo to escape the revolutionaries.

The

Carmine Castle

The Carmine Castle () was a castle in Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative lim ...

, built in 1392 and highly modified in the 16th century by the Spanish, was demolished in 1906 to make room for the Via Marina, although two of the castle's towers remain as a monument. The Vigliena Fort, built in 1702, was destroyed in 1799 during the royalist war against the Parthenopean Republic and is now abandoned and in ruin.

Museums

Naples is widely known for its wealth of historical museums. The

Naples National Archaeological Museum

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples (, ) is an important Italian archaeological museum. Its collection includes works from Greek, Roman and Renaissance times, and especially Roman artifacts from the nearby Pompeii, Stabiae and Hercu ...

is one of the city's main museums, with one of the most extensive collections of

artefacts of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

in the world.

It also houses many of the antiques unearthed at

Pompeii

Pompeii ( ; ) was a city in what is now the municipality of Pompei, near Naples, in the Campania region of Italy. Along with Herculaneum, Stabiae, and Villa Boscoreale, many surrounding villas, the city was buried under of volcanic ash and p ...

and

Herculaneum

Herculaneum is an ancient Rome, ancient Roman town located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under a massive pyroclastic flow in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Like the nearby city of ...

, as well as some artefacts from the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

periods.