Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ;

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of

Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

in the

Greater Antilles

The Greater Antilles ( es, Grandes Antillas or Antillas Mayores; french: Grandes Antilles; ht, Gwo Zantiy; jam, Grieta hAntiliiz) is a grouping of the larger islands in the Caribbean Sea, including Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and ...

archipelago of the

Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

, east of

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

and

Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

, and south of

The Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

and the

Turks and Caicos Islands

The Turks and Caicos Islands (abbreviated TCI; and ) are a British Overseas Territory consisting of the larger Caicos Islands and smaller Turks Islands, two groups of tropical islands in the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean and n ...

. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island which it shares with the

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

.

To its south-west lies the small

Navassa Island

Navassa Island (; ht, Lanavaz; french: l'île de la Navasse, sometimes ) is a small uninhabited island in the Caribbean Sea. Located northeast of Jamaica, south of Cuba, and west of Jérémie on the Tiburon Peninsula of Haiti, it is subject to ...

, which is claimed by Haiti but is disputed as a

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

territory

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

under federal administration.

["Haiti"](_blank)

''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Haiti is in size, the third largest country in the

Caribbean

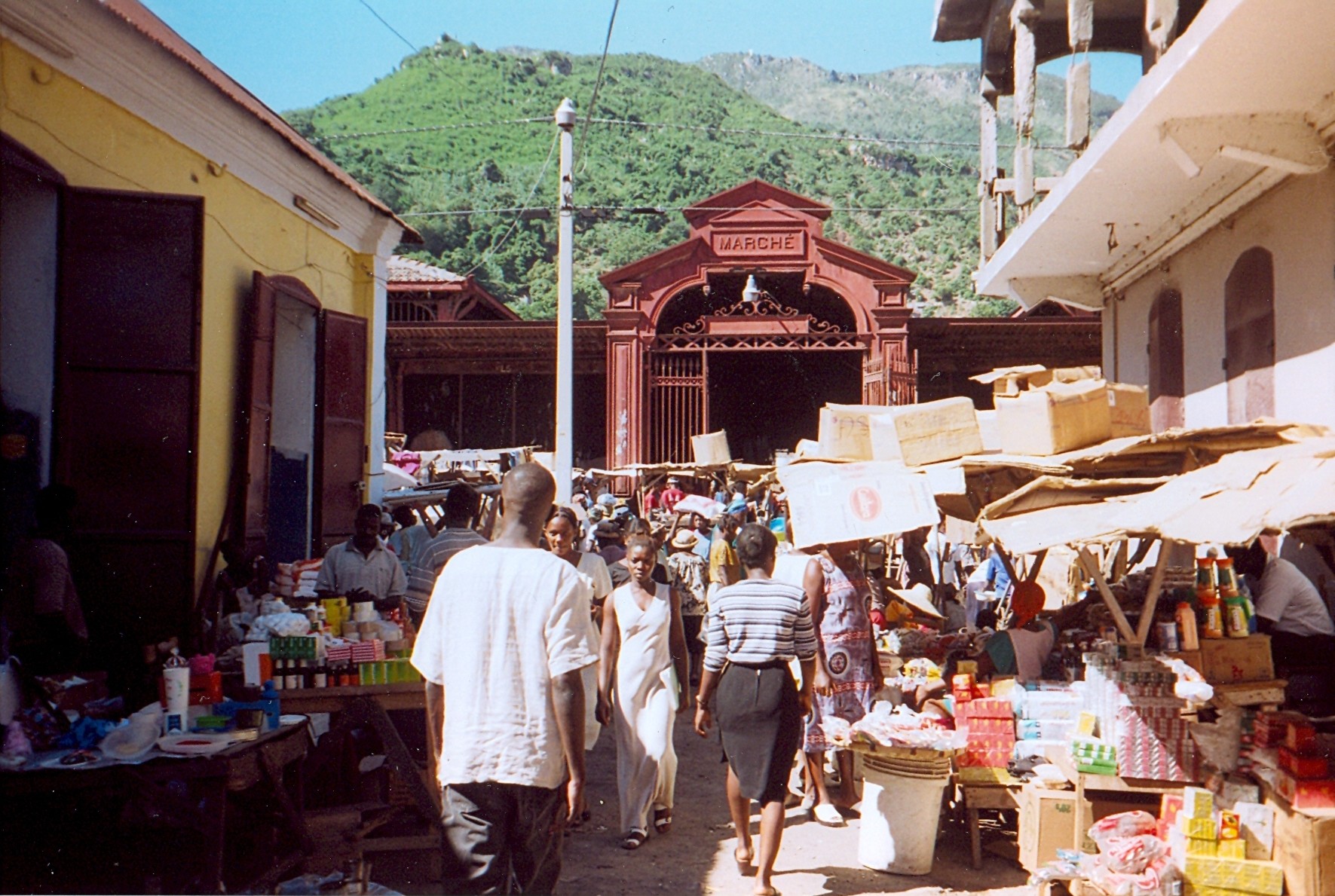

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

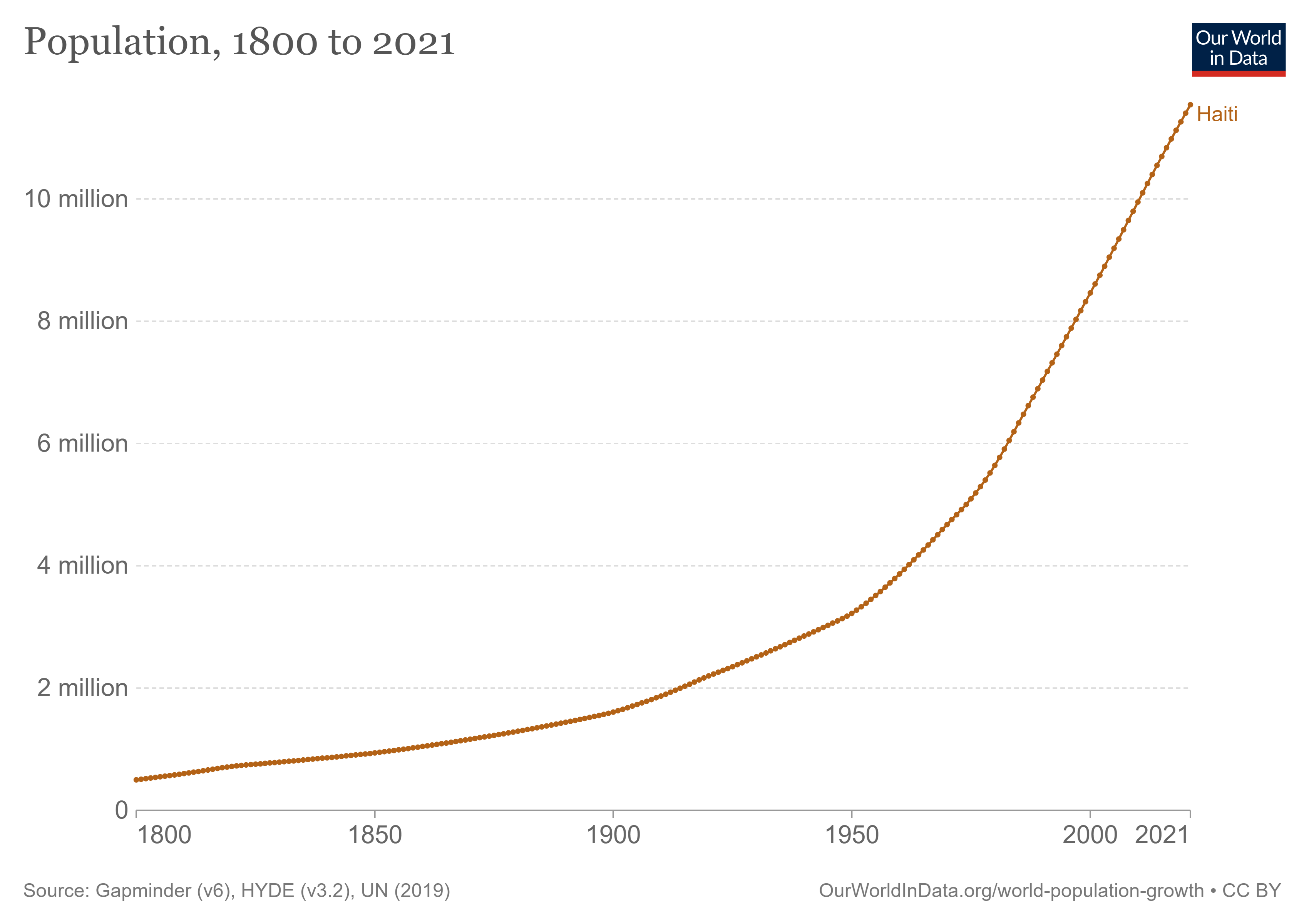

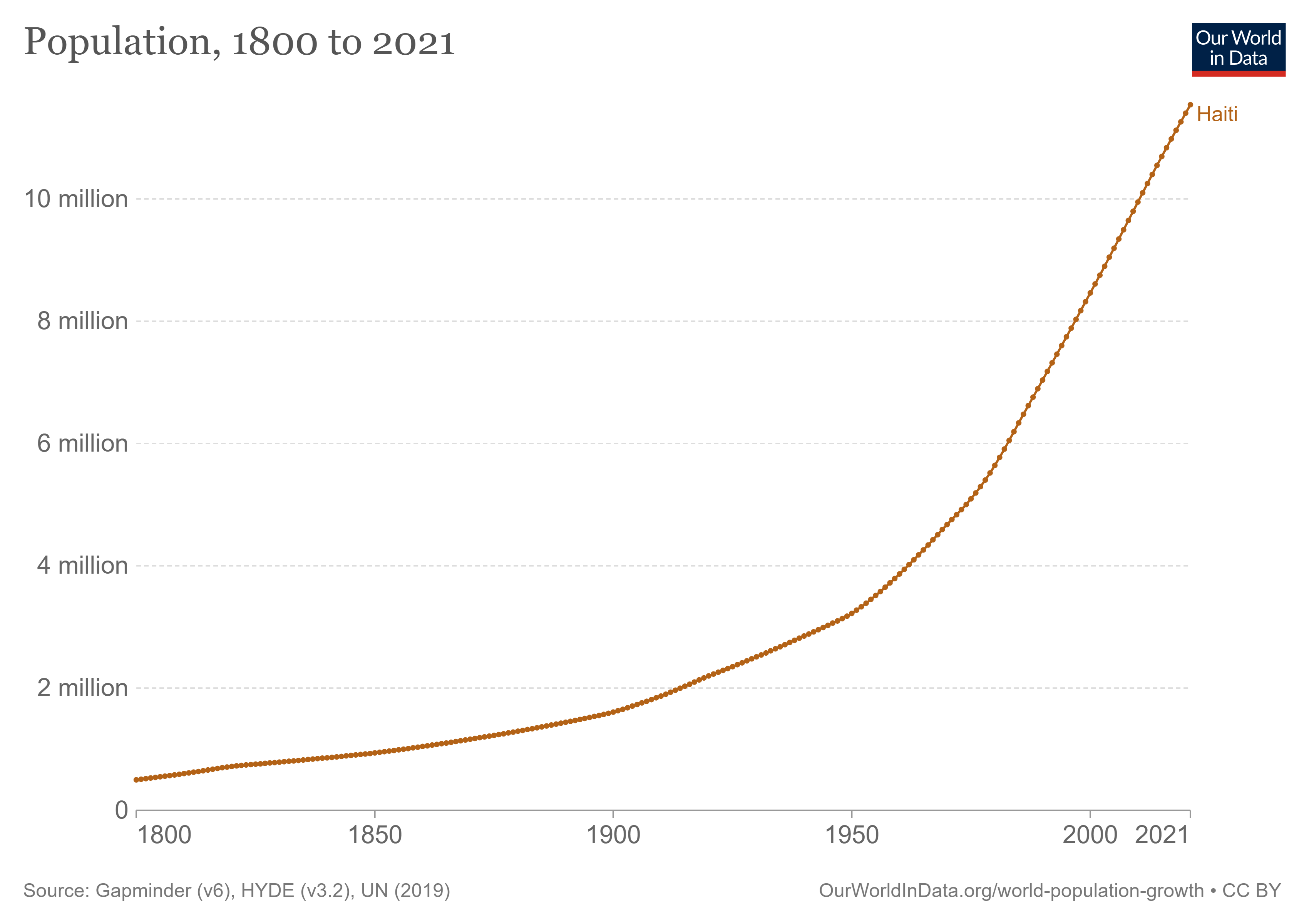

by area, and has an estimated population of 11.4 million, making it the most populous country in the Caribbean. The capital is

Port-au-Prince

Port-au-Prince ( , ; ht, Pòtoprens ) is the capital and most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 987,311 in 2015 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618,894. The metropolitan area is define ...

.

The island was originally inhabited by the indigenous

Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

people, who originated in South America.

The first Europeans arrived on 5 December 1492 during the

first voyage of

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

, who initially believed he had found

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

or

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

.

Columbus subsequently founded the first European settlement in the Americas,

La Navidad

La Navidad ("The Nativity", i.e. Christmas) was a settlement that Christopher Columbus and his men established on the northeast coast of Haiti (near what is now Caracol, Nord-Est Department, Haiti) in 1492 from the remains of the Spanish ship th ...

, on what is now the northeastern coast of Haiti.

The island was claimed by

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and named , forming part of the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

until the early 17th century. However, competing claims and settlements by the French led to the western portion of the island being

ceded to France in 1697, which was subsequently named . French colonists established lucrative

sugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, Perennial plant, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar Sugar industry, production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with ...

plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

, worked by vast numbers of slaves brought from Africa, which made the colony one of the richest in the world.

In the midst of the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

(1789–99), slaves, maroons, and

free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

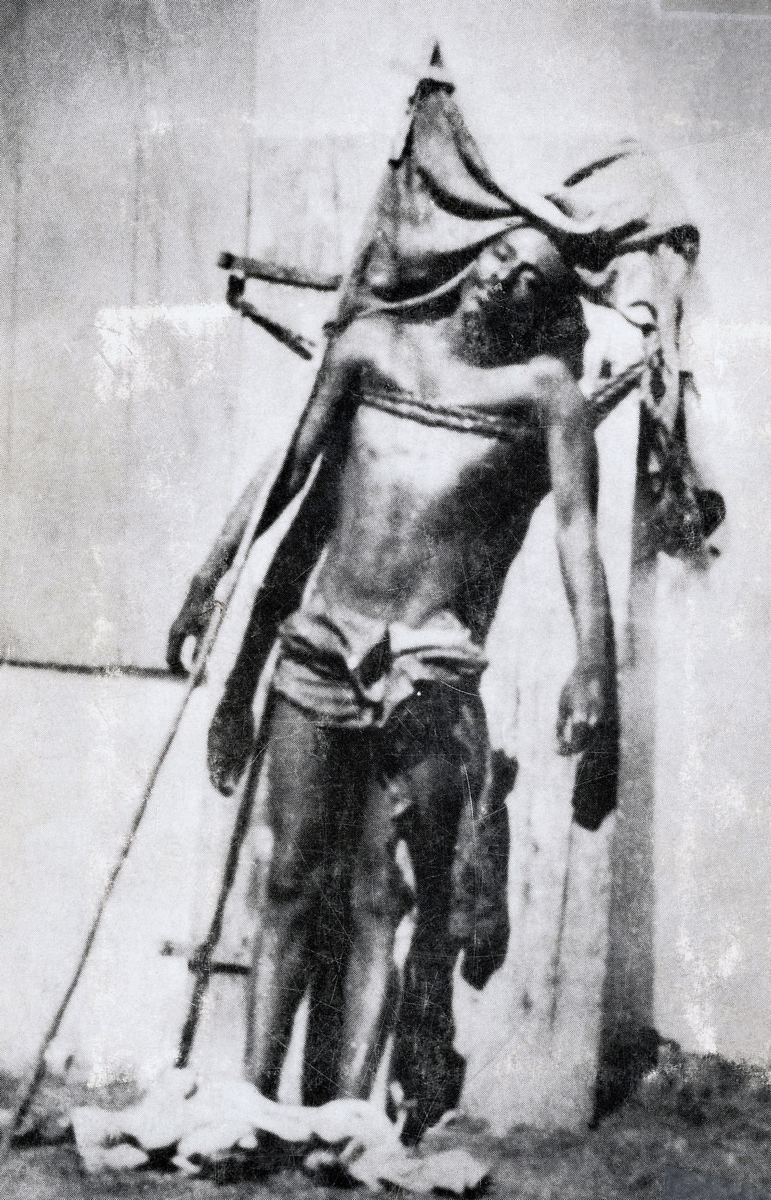

launched the

Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt ...

(1791–1804), led by a former slave and the first black general of the

French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed For ...

,

Toussaint Louverture

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture (; also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda; 20 May 1743 – 7 April 1803) was a Haitian general and the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life, Louverture ...

. After 12 years of conflict,

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's forces were defeated by Louverture's successor,

Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Haitian Creole: ''Jan-Jak Desalin''; ; 20 September 1758 – 17 October 1806) was a leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first ruler of an independent First Empire of Haiti, Haiti under the Constitution of Haiti, 1 ...

(later Emperor Jacques I), who declared Haiti's sovereignty on 1 January 1804—the first independent

nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by those ...

of

Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

and the

Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

, the second

republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

in the Americas, the first country in the Americas to abolish slavery, and the only state in history established by a successful

slave revolt

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by enslaved people, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of enslaved people have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire for freed ...

. Apart from

Alexandre Pétion

Alexandre Sabès Pétion (; April 2, 1770 – March 29, 1818) was the first president of the Republic of Haiti from 1807 until his death in 1818. He is acknowledged as one of Haiti's founding fathers; a member of the revolutionary quartet that ...

, the first President of the Republic, all of Haiti's first leaders were former slaves. After a brief period in which the country was split in two, President

Jean-Pierre Boyer

Jean-Pierre Boyer (15 February 1776 – 9 July 1850) was one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, and President of Haiti from 1818 to 1843. He reunited the north and south of the country into the Republic of Haiti in 1820 and also annex ...

united the country and then attempted to bring the whole of Hispaniola under Haitian control, precipitating a long series of wars that ended in the 1870s when Haiti formally recognized the independence of the Dominican Republic.

Haiti's first century of independence was characterized by political instability, ostracism by the international community, and the payment of a

crippling debt to France. Political volatility and foreign economic influence in the country prompted the

U.S.

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

to

occupy the country from 1915 to 1934. Following a series of short-lived presidencies,

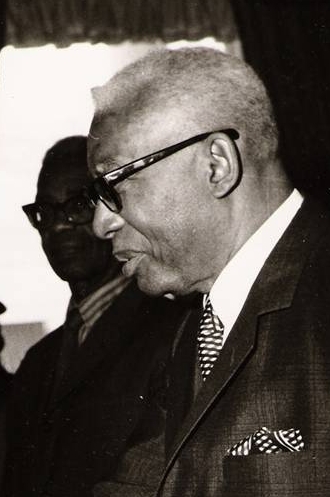

François 'Papa Doc' Duvalier took power in 1956, ushering in a long period of autocratic rule continued by his son,

Jean-Claude 'Baby Doc' Duvalier, that lasted until 1986; the period was characterized by state-sanctioned violence against the opposition and civilians, corruption, and economic stagnation. After 1986, Haiti began attempting to establish a more democratic political system.

Haiti is a founding member of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

,

Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS; es, Organización de los Estados Americanos, pt, Organização dos Estados Americanos, french: Organisation des États américains; ''OEA'') is an international organization that was founded on 30 April ...

(OAS),

Association of Caribbean States

The Association of Caribbean States (ACS; es, Asociación de Estados del Caribe; french: Association des États de la Caraïbe) is an advisory association of nations centered on the Caribbean Basin. It was formed with the aim of promoting cons ...

, and the

Organisation internationale de la Francophonie

The (OIF; sometimes shortened to the Francophonie, french: La Francophonie , but also called International Organisation of in English-language context) is an international organization representing countries and regions where French is a ...

. In addition to

CARICOM, it is a member of the

International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster globa ...

,

World Trade Organization

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an intergovernmental organization that regulates and facilitates international trade. With effective cooperation

in the United Nations System, governments use the organization to establish, revise, and e ...

, and the

Community of Latin American and Caribbean States

A community is a social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as place, norms, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given geographical area (e.g. a country, village, town ...

. Historically poor and politically unstable, Haiti has the lowest

Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistic composite index of life expectancy, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income indicators, whi ...

in the Americas, as well as

widespread slavery. Since the turn of the 21st century, the country has endured a

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

, which prompted

U.N. intervention, as well as

a catastrophic earthquake that killed over 250,000 people. With its deteriorating economic situation, as well as recent calls by the

IMF to cut fuel subsidies, Haiti has been experiencing

a socioeconomic and political crisis marked by riots and protests, widespread hunger, and increased gang activity.

Etymology

''Haiti'' (also earlier ''Hayti'') comes from the indigenous

Taíno language

Taíno is an extinct Arawakan language that was spoken by the Taíno people of the Caribbean. At the time of Spanish contact, it was the most common language throughout the Caribbean. Classic Taíno (Taíno proper) was the native language of th ...

, in which it means "land of high mountains" and named the entire island of

Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

. The name was restored by Haitian revolutionary Jean-Jacques Dessalines as the official name of independent Saint-Domingue, as a tribute to the Amerindian predecessors.

In French, the ''

ï'' in ''Haïti'' has a

diacritical mark

A diacritic (also diacritical mark, diacritical point, diacritical sign, or accent) is a glyph added to a letter or to a basic glyph. The term derives from the Ancient Greek (, "distinguishing"), from (, "to distinguish"). The word ''diacritic ...

(used to show that the second vowel is pronounced separately, as in the word ''naïve''), while the ''H'' is silent. (In English, this rule for the pronunciation is often disregarded, thus the spelling ''Haiti'' is used.) There are different anglicizations for its pronunciation such as ''HIGH-ti'', ''high-EE-ti'' and ''haa-EE-ti'', which are still in use, but ''HAY-ti'' is the most widespread and best-established. In French, Haiti's nickname means the "Pearl of the Antilles" (''La Perle des Antilles'') because of both its natural beauty and the amount of wealth it accumulated for the

Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

. During the 18th century, the colony was the world's leading producer of sugar and coffee.

In

Haitian Creole

Haitian Creole (; ht, kreyòl ayisyen, links=no, ; french: créole haïtien, links=no, ), commonly referred to as simply ''Creole'', or ''Kreyòl'' in the Creole language, is a French-based creole language spoken by 10–12million people wor ...

, it is spelled and pronounced with a ''y'' but no ''H'': ht, Ayiti, label=none''.''

Another theory on the name Haiti is its origin in African tradition, in Fon language one of the most spoken by the bossales (Haitians born in Africa to differentiate from the creoles or Haitians born in Haiti (St-Domingue) in early Haiti

Ayiti-Tomèmeans: From nowadays this land is our land.

In the Haitian community the country has multiple nicknames: Ayiti-Toma (as its origin in Ayiti Tomè), Ayiti-Cheri (Ayiti my Darling), Tè-Desalin (Dessalines' Land) or Lakay (Home).

History

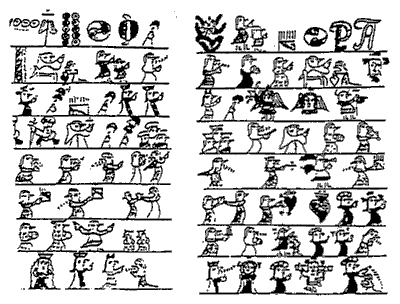

Taino history

The island of

Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

, of which Haiti occupies the western three-eighths,

has been inhabited since about 5000 BC by groups of Native Americans thought to have arrived from Central or South America.

Genetic studies show that some of these groups were related to the

Yanomami

The Yanomami, also spelled Yąnomamö or Yanomama, are a group of approximately 35,000 indigenous people who live in some 200–250 villages in the Amazon rainforest on the border between Venezuela and Brazil.

Etymology

The ethnonym ''Yanomami ...

of the

Amazon Basin

The Amazon basin is the part of South America drained by the Amazon River and its tributaries. The Amazon drainage basin covers an area of about , or about 35.5 percent of the South American continent. It is located in the countries of Bolivi ...

.

Amongst these early settlers were the

Ciboney

The Ciboney, or Siboney, were a Taíno people of western Cuba, Jamaica, and the Tiburon Peninsula of Haiti. A Western Taíno group living in central Cuba during the 15th and 16th centuries, they had a dialect and culture distinct from the Classic ...

peoples, followed by the

Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

, speakers of an

Arawakan

Arawakan (''Arahuacan, Maipuran Arawakan, "mainstream" Arawakan, Arawakan proper''), also known as Maipurean (also ''Maipuran, Maipureano, Maipúre''), is a language family that developed among ancient indigenous peoples in South America. Branch ...

language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of met ...

, elements of which have been preserved in

Haitian Creole

Haitian Creole (; ht, kreyòl ayisyen, links=no, ; french: créole haïtien, links=no, ), commonly referred to as simply ''Creole'', or ''Kreyòl'' in the Creole language, is a French-based creole language spoken by 10–12million people wor ...

. The Taíno name for the entire island was ''Haiti'', or alternatively ''Quisqeya''.

[Clammer, Paul (2016), ''Bradt Travel Guide – Haiti'', p. 9.]In Taíno society the largest unit of political organization was led by a ''

cacique

A ''cacique'' (Latin American ; ; feminine form: ''cacica'') was a tribal chieftain of the Taíno people, the indigenous inhabitants at European contact of the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles, and the northern Lesser Antilles. The term is a Spa ...

,'' or chief, as the Europeans understood them. The island of Hispaniola was divided among five 'caciquedoms': the Magua in the north east, the Marien in the north west, the Jaragua in the south west, the Maguana in the central regions of Cibao, and the Higüey in the south east.

Historical Taíno names for areas include:

*Guarico, now

Limonade-Cap-Haitien

*Bayaha, now

Fort-Liberté

Fort-Liberté ( ht, Fòlibète) is a commune and administrative capital of the Nord-Est department of Haiti. It is close to the border of the Dominican Republic and is one of the oldest cities in the country. Haiti's independence was proclaimed ...

*Xarama, now

Port-de-Paix

Port-de-Paix (; ht, Pòdepè or ; meaning "Port of Peace") is a List of communes of Haiti, commune and the capital of the Nord-Ouest (department), Nord-Ouest Departments of Haiti, department of Haiti on the Atlantic coast. It has a population of ...

*Gonayibo, now

Gonaives

*Amani-y, now

Saint-Marc

Saint-Marc ( ht, Sen Mak) is a commune in western Haiti in Artibonite departement. Its geographic coordinates are . At the 2003 Census the commune had 160,181 inhabitants. It is one of the biggest cities, second to Gonaïves, between Port-au-P ...

*Yaguana, now

Léoganes

*Mamey, now

Abricot

*Yakimèl, now

Jacmel

Jacmel (; ht, Jakmèl) is a commune in southern Haiti founded by the Spanish in 1504 and repopulated by the French in 1698. It is the capital of the department of Sud-Est, 24 miles (39 km) southwest of Port-au-Prince across the Tiburon Peninsula ...

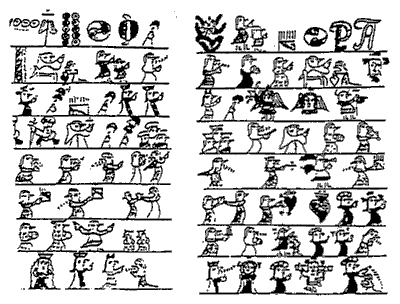

Taíno cultural artifacts include

cave paintings

In archaeology, Cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric art, prehistoric origin, and the oldest known are mor ...

in several locations in the country. These have become national symbols of Haiti and tourist attractions. Modern-day

Léogâne

Léogâne ( ht, Leyogàn) is one of the List of communes of Haiti, coastal communes in Haiti. It is located in the eponymous Léogâne Arrondissement, which is part of the Ouest (department), Ouest Department. The port town is located about we ...

, started as a French colonial town in the southwest, is beside the former capital of the caciquedom of ''Xaragua.''

Colonial era

Spanish rule (1492–1625)

Navigator

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

landed in Haiti on 6 December 1492, in an area that he named ''

Môle-Saint-Nicolas

Môle-Saint-Nicolas (; ht, Mòlsennikola or ) is a commune in the north-western coast of Haiti. It is the chief town of the Môle-Saint-Nicolas Arrondissement in the department of Nord-Ouest.

History

Christopher Columbus' first voyage to th ...

,'' and claimed the island for the

Crown of Castile

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accessi ...

. Nineteen days later, his ship the ''

Santa María'' ran aground near the present site of

Cap-Haïtien

Cap-Haïtien (; ht, Kap Ayisyen; "Haitian Cape"), typically spelled Cape Haitien in English and often locally referred to as or , is a commune of about 190,000 people on the north coast of Haiti and capital of the department of Nord. Previousl ...

. Columbus left 39 men on the island, who founded the settlement of

La Navidad

La Navidad ("The Nativity", i.e. Christmas) was a settlement that Christopher Columbus and his men established on the northeast coast of Haiti (near what is now Caracol, Nord-Est Department, Haiti) in 1492 from the remains of the Spanish ship th ...

on 25 December 1492.

Relations with the native peoples, initially good, broke down and the settlers were later killed by the Taíno.

[Clammer, Paul (2016), ''Bradt Travel Guide – Haiti'', p. 10.]

The sailors carried endemic Eurasian

infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

s to which the native peoples lacked

immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

, causing them to die in great numbers in

epidemic

An epidemic (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics ...

s. The first recorded

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

epidemic in the Americas erupted on Hispaniola in 1507. Their numbers were further reduced by the harshness of the ' system, in which the Spanish forced natives to work in gold mines and plantations.

The Spanish passed the

Laws of Burgos

The Laws of Burgos ( es, Leyes de Burgos), promulgated on 27 December 1512 in Burgos, Crown of Castile (Spain), was the first codified set of laws governing the behavior of Spaniards in the Americas, particularly with regard to the Indigenous pe ...

(1512–1513), which forbade the maltreatment of natives, endorsed their

conversion

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* "Conversion" (''Stargate Atlantis''), an episode of the television series

* "The Conversion" ...

to Catholicism, and gave legal framework to ''.'' The natives were brought to these sites to work in specific plantations or industries.

As the Spanish re-focused their colonization efforts on the greater riches of mainland Central and South America, Hispaniola became reduced largely to a trading and refueling post. As a result

piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

became widespread, encouraged by European powers hostile to Spain such as France (based on

Île de la Tortue) and England.

The Spanish largely abandoned the western third of the island, focusing their colonization effort on the eastern two-thirds.

The western part of the island was thus gradually settled by French

buccaneer

Buccaneers were a kind of privateers or free sailors particular to the Caribbean Sea during the 17th and 18th centuries. First established on northern Hispaniola as early as 1625, their heyday was from Stuart Restoration, the Restoration in 16 ...

s; among them was Bertrand d'Ogeron, who succeeded in growing

tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

and recruited many French colonial families from

Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

and

Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and the ...

. In 1697

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

settled their hostilities on the island by way of the

Treaty of Ryswick

The Peace of Ryswick, or Rijswijk, was a series of treaties signed in the Dutch city of Rijswijk between 20 September and 30 October 1697. They ended the 1688 to 1697 Nine Years' War between France and the Grand Alliance, which included England, ...

of 1697, which divided Hispaniola between them.

[Clammer, Paul (2016), ''Bradt Travel Guide – Haiti'', p. 11.]

French rule (1625–1804)

France received the western third and subsequently named it

Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer ...

, the French equivalent of ''

Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

'', the Spanish colony on

Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

.

The French set about creating sugar and coffee plantations, worked by vast numbers of slaves imported from

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, and Saint-Domingue grew to become their richest colonial possession.

The French settlers were outnumbered by slaves by almost 10 to 1.

According to the 1788 Census, Haiti's population consisted of nearly 25,000 Europeans, 22,000 free coloreds and 700,000 African slaves. In contrast, by 1763 the white population of

French Canada

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fre ...

, a far larger territory, had numbered only 65,000. In the north of the island, slaves were able to retain many ties to African cultures, religion and language; these ties were continually being renewed by newly imported Africans. Some West African slaves held on to their traditional

Vodou beliefs by secretly syncretizing it with Catholicism.

The French enacted the ''

Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by the French King Louis XIV in 1685 defining the conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire. The decree restricted the activities of free people of color, mandated the conversion of all e ...

'' ("Black Code"), prepared by

Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (; 29 August 1619 – 6 September 1683) was a French statesman who served as First Minister of State from 1661 until his death in 1683 under the rule of King Louis XIV. His lasting impact on the organization of the countr ...

and ratified by

Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

, which established rules on slave treatment and permissible freedoms.

[Clammer, Paul (2016), ''Bradt Travel Guide – Haiti'', p. 12.] Saint-Domingue has been described as one of the most brutally efficient slave colonies; one-third of newly imported Africans died within a few years.

Many slaves died from diseases such as

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and

typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

. They had low

birth rate

The birth rate for a given period is the total number of live human births per 1,000 population divided by the length of the period in years. The number of live births is normally taken from a universal registration system for births; populati ...

s, and there is evidence that some women

aborted

Aborted is a Belgian death metal band formed in 1995 in Waregem. The group currently consists of vocalist, founder and only constant member Sven de Caluwé, guitarist Ian Jekelis, bassist Stefano Franceschini and drummer Ken Bedene. Although th ...

fetuses rather than give birth to children within the bonds of

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. The colony's environment also suffered, as forests were cleared to make way for plantations and the land was overworked so as to extract maximum profit for French plantation owners.

As in its

Louisiana colony, the

French colonial

French colonial architecture includes several styles of architecture used by the French during colonization. Many former French colonies, especially those in Southeast Asia, have previously been reluctant to promote their colonial architecture ...

government allowed some rights to

free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

(), the

mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-ethn ...

descendants of European male colonists and African female slaves (and later, mixed-race women).

Over time, many were released from slavery and they established a separate

social class

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the Upper class, upper, Middle class, middle and Working class, lower classes. Membership in a social class can for ...

. White French

Creole fathers frequently sent their mixed-race sons to

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

for their education. Some men of color were admitted into the military. More of the free people of color lived in the south of the island, near

Port-au-Prince

Port-au-Prince ( , ; ht, Pòtoprens ) is the capital and most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 987,311 in 2015 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618,894. The metropolitan area is define ...

, and many intermarried within their community.

They frequently worked as artisans and tradesmen, and began to own some property, including slaves of their own.

The free people of color petitioned the

colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

government to expand their rights.

The brutality of slave life led many slaves to escape to mountainous regions, where they set up their own autonomous communities and became known as

Maroons

Maroons are descendants of African diaspora in the Americas, Africans in the Americas who escaped from slavery and formed their own settlements. They often mixed with indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous peoples, eventually ethnogenesi ...

.

One Maroon leader,

François Mackandal

François Mackandal (c.1730-c.1758) was a Haitian Maroon leader in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti). He is sometimes described as a Haitian vodou priest, or houngan. For joining Maroons to kill slave owners in Saint-Dom ...

, led a rebellion in the 1750s, however he was later captured and executed by the French.

Haitian Revolution (1791–1804)

Inspired by the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

of 1789 and principles of the

rights of man

''Rights of Man'' (1791), a book by Thomas Paine, including 31 articles, posits that popular political revolution is permissible when a government does not safeguard the natural rights of its people. Using these points as a base it defends the ...

, the French settlers and free people of color pressed for greater political freedom and more

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

.

Tensions between these two groups led to conflict, as a militia of free-coloreds was set up in 1790 by

Vincent Ogé

Vincent Ogé ( – 6 February 1791) was a Dominican Creole revolutionary, merchant, military officer and goldsmith best known for his role in leading a failed uprising against French colonial rule in the colony of Saint-Domingue in 1790. A mixed ...

, resulting in his capture, torture and execution.

Sensing an opportunity, in August 1791 the first slave armies were established in northern Haiti under the leadership of

Toussaint Louverture

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture (; also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda; 20 May 1743 – 7 April 1803) was a Haitian general and the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life, Louverture ...

inspired by the Vodou ''houngan'' (priest) Boukman, and backed by the Spanish in Santo Domingo – soon a full-blown slave rebellion had broken out across the entire colony.

In 1792, the

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

government sent three commissioners with troops to re-establish control; to build an alliance with the ''

gens de couleur

In ancient Rome, a gens ( or , ; plural: ''gentes'' ) was a family consisting of individuals who shared the same Roman naming conventions#Nomen, nomen and who claimed descent from a common ancestor. A branch of a gens was called a ''stirps'' (p ...

'' and slaves commissioners

Léger-Félicité Sonthonax

Léger-Félicité Sonthonax (7 March 1763 – 23 July 1813) was a French abolitionist and Jacobin before joining the Girondist party, which emerged in 1791. During the French Revolution, he controlled 7,000 French troops in Saint-Domingue during pa ...

and

Étienne Polverel

Étienne Polverel (1740–1795) was a French lawyer, aristocrat, and revolutionary. He was a member of the Jacobin club.

In 1792, he and Léger Félicité Sonthonax were sent to Saint-Domingue to suppress the slave revolt and to implement the de ...

abolished slavery in the colony.

Six months later, the

National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

, led by

Maximilien de Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

and the

Jacobins

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = Pa ...

, endorsed

abolition

Abolition refers to the act of putting an end to something by law, and may refer to:

* Abolitionism, abolition of slavery

* Abolition of the death penalty, also called capital punishment

* Abolition of monarchy

*Abolition of nuclear weapons

*Abol ...

and extended it to all the French colonies.

The

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, which was a new republic itself, oscillated between supporting or not supporting

Toussaint Louverture

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture (; also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda; 20 May 1743 – 7 April 1803) was a Haitian general and the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life, Louverture ...

and the emerging country of Haiti, depending on who was President of the US. Washington, who was a slave holder and isolationist, kept the United States neutral, although private US citizens at times provided aid to French

planters

Planters Nut & Chocolate Company is an American snack food company now owned by Hormel Foods. Planters is best known for its processed nuts and for the Mr. Peanut icon that symbolizes them. Mr. Peanut was created by grade schooler Antonio Gentil ...

trying to put down the revolt. John Adams, a vocal opponent of slavery, fully supported the slave revolt by providing diplomatic recognition, financial support, munitions and warships (including the

USS Constitution

USS ''Constitution'', also known as ''Old Ironsides'', is a three-masted wooden-hulled heavy frigate of the United States Navy. She is the world's oldest ship still afloat. She was launched in 1797, one of six original frigates authorized ...

) beginning in 1798. This support ended in 1801 when Jefferson, another slave-holding president, took office and recalled the US Navy.

With slavery abolished, Toussaint Louverture pledged allegiance to France, and he fought off the British and Spanish forces who had taken advantage of the situation and invaded Saint-Domingue.

The Spanish were later forced to cede their part of the island to France under the terms of the

Peace of Basel

The Peace of Basel of 1795 consists of three peace treaties involving France during the French Revolution (represented by François de Barthélemy).

*The first was with Prussia (represented by Karl August von Hardenberg) on 5 April;

*The seco ...

in 1795, uniting the island under one government. However an insurgency against French rule broke out in the east, and in the west there was fighting between Louverture's forces and the free people of color led by

André Rigaud

Benoit Joseph André Rigaud (17 January 1761 – 18 September 1811) was the leading mulatto military leader during the Haitian Revolution. Among his protégés were Alexandre Pétion and Jean-Pierre Boyer, both future presidents of Haïti.

Ea ...

in the

War of the Knives

The War of Knives (French: ''Guerre des couteaux''), also known as the War of the South, was a civil war from June 1799 to July 1800 between the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture, a black ex-slave who controlled the north of Saint-Domi ...

(1799–1800). More than 25,000 surviving free people of color left the island as refugees.

After Louverture created a separatist constitution and proclaimed himself governor-general for life,

Napoléon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in 1802 sent an expedition of 20,000 soldiers and as many sailors under the command of his brother-in-law,

Charles Leclerc

Charles Marc Hervé Perceval Leclerc (; born 16 October 1997) is a Monégasque racing driver, currently racing in Formula One for Scuderia Ferrari. He won the GP3 Series championship in 2016 and the FIA Formula 2 Championship in .

Leclerc ma ...

, to reassert French control. The French achieved some victories, but within a few months most of their

army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

had died from

yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

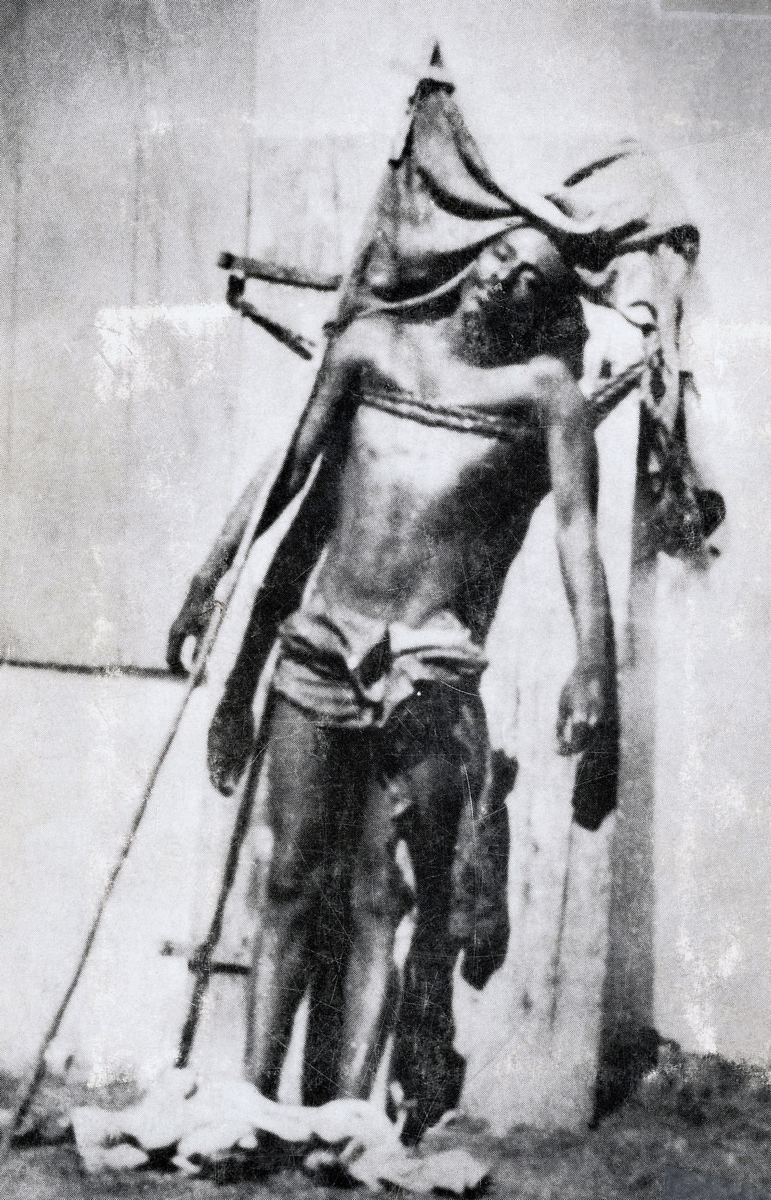

. Ultimately more than 50,000 French troops died in an attempt to retake the colony, including 18 generals. The French managed to capture Louverture, transporting him to France for trial. He was imprisoned at

Fort de Joux

The Fort de Joux or Château de Joux is a castle, later transformed into a fort, located in La Cluse-et-Mijoux in the Doubs department in the Jura mountains of France. It commands the mountain pass ''Cluse de Pontarlier''.

History

The Château ...

, where he died in 1803 of exposure and possibly

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

.

[Clammer, Paul (2016), ''Bradt Travel Guide – Haiti'', p. 13.]

The slaves, along with free and allies, continued their fight for independence, led by generals

Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Haitian Creole: ''Jan-Jak Desalin''; ; 20 September 1758 – 17 October 1806) was a leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first ruler of an independent First Empire of Haiti, Haiti under the Constitution of Haiti, 1 ...

,

Alexandre Pétion

Alexandre Sabès Pétion (; April 2, 1770 – March 29, 1818) was the first president of the Republic of Haiti from 1807 until his death in 1818. He is acknowledged as one of Haiti's founding fathers; a member of the revolutionary quartet that ...

and

Henry Christophe

Henri Christophe (; 6 October 1767 – 8 October 1820) was a key leader in the Haitian Revolution and the only monarch of the Kingdom of Haiti.

Christophe was of Bambara ethnicity in West Africa, and perhaps of Igbo descent. Beginning with t ...

.

The rebels finally managed to decisively defeat the French troops at the

Battle of Vertières

The Battle of Vertières ( ht, Batay Vètyè) was the last major battle of the Haitian Revolution, and the final part of the Revolution under Jean Jacques Dessalines. It was fought on 18 November 1803 between the indigenous Haitian army and Nap ...

on 18 November 1803, establishing the first nation ever to successfully gain independence through a slave revolt. Under the overall command of Dessalines, the Haitian armies avoided open battle, and instead conducted a successful guerrilla campaign against the Napoleonic forces, working with diseases such as yellow fever to reduce the numbers of French soldiers. Later that year France withdrew its remaining 7,000 troops from the island and Napoleon gave up his idea of re-establishing a

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

n empire, selling

Louisiana (New France)

Louisiana (french: La Louisiane; ''La Louisiane Française'') or French Louisiana was an administrative district of New France. Under French control from 1682 to 1769 and 1801 (nominally) to 1803, the area was named in honor of King Louis XIV, ...

to the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, in the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

.

It has been estimated that between 24,000 and 100,000 Europeans, and between 100,000 and 350,000 Haitian ex-slaves, died in the revolution. In the process, Dessalines became arguably the most successful military commander in the struggle against Napoleonic France.

Independent Haiti

First Empire (1804–1806)

The independence of Saint-Domingue was proclaimed under the native name 'Haiti' by

Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Haitian Creole: ''Jan-Jak Desalin''; ; 20 September 1758 – 17 October 1806) was a leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first ruler of an independent First Empire of Haiti, Haiti under the Constitution of Haiti, 1 ...

on 1 January 1804 in

Gonaïves

Gonaïves (; ht, Gonayiv, ) is a commune in northern Haiti, and the capital of the Artibonite department of Haiti. It has a population of about 300,000 people, but current statistics are unclear, as there has been no census since 2003.

History ...

[Clammer, Paul (2016), ''Bradt Travel Guide – Haiti'', p. 209.] and he was proclaimed "Emperor for Life" as Emperor Jacques I by his troops. Dessalines at first offered protection to the white planters and others. However, once in power, he ordered the

massacre

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

of nearly all the remaining white men, women, children; between January and April 1804, 3,000 to 5,000 whites were killed, including those who had been friendly and sympathetic to the black population.

Only

three categories of white people were selected out as exceptions and spared:

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

soldiers, the majority of whom had deserted from the French army and fought alongside the Haitian rebels; the small group of

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

colonists invited to the

north-west region; and a group of

medical doctors

Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated M.D., from the Latin ''Medicinae Doctor'') is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the M.D. denotes a professional degree. T ...

and professionals. Reportedly, people with connections to officers in the Haitian army were also spared, as well as the women who agreed to marry non-white men.

Fearful of the potential impact the slave rebellion could have in the

slave states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

, U.S. President

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

refused to recognize the new republic. The Southern politicians who were a powerful voting bloc in the American Congress prevented U.S. recognition for decades until they withdrew in 1861 to form the

Confederacy.

The revolution led to a wave of emigration. In 1809, 9,000 refugees from Saint-Domingue, both white planters and people of color, settled ''en masse'' in

, doubling the city's population, having been expelled from their initial refuge in Cuba by Spanish authorities. In addition, the newly arrived slaves added to the city's African population.

The plantation system was reestablished in Haiti, albeit for wages, however many Haitians were marginalized and resented the heavy-handed manner in which this was enforced in the new nation's politics.

The rebel movement splintered, and Dessalines was assassinated by rivals on 17 October 1806.

State of Haiti, Kingdom of Haiti and the Republic (1806–1820)

After Dessalines' death Haiti became split into two, with the

Kingdom of Haiti

The Kingdom of Haiti (french: Royaume d'Haïti; ht, Wayòm an Ayiti) was the state established by Henri Christophe on 28 March 1811 when he proclaimed himself King Henri I after having previously ruled as president of the State of Haiti, in the ...

in the north directed by Henri Christophe, later declaring himself

Henri I, and a republic in the south centered on Port-au-Prince, directed by

Alexandre Pétion

Alexandre Sabès Pétion (; April 2, 1770 – March 29, 1818) was the first president of the Republic of Haiti from 1807 until his death in 1818. He is acknowledged as one of Haiti's founding fathers; a member of the revolutionary quartet that ...

, an ''homme de couleur''.

Christophe established a semi-feudal

corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid, forced labour, that is intermittent in nature lasting for limited periods of time: typically for only a certain number of days' work each year.

Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state for the purposes of ...

system, with a rigid education and economic code. Pétion's republic was less absolutist, and he initiated a series of land reforms which benefited the peasant class.

President Pétion also gave military and financial assistance to the revolutionary leader

Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24 July 1783 – 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama and B ...

, which were critical in enabling him to liberate the

Viceroyalty of New Granada

The Viceroyalty of New Granada ( es, Virreinato de Nueva Granada, links=no ) also called Viceroyalty of the New Kingdom of Granada or Viceroyalty of Santafé was the name given on 27 May 1717, to the jurisdiction of the Spanish Empire in norther ...

. Meanwhile, the French, who had managed to maintain a precarious control of eastern Hispaniola, were

defeated

Defeated may refer to:

*Defeated (Breaking Benjamin song), "Defeated" (Breaking Benjamin song)

*Defeated (Anastacia song), "Defeated" (Anastacia song)

*"Defeated", a song by Snoop Dogg from the album ''Bible of Love''

*Defeated, Tennessee, an unin ...

by insurgents led by

Juan Sánchez Ramírez

Juan Sánchez Ramírez (1762–1811) was a Dominican soldier who served as the Captain general of the modern Dominican Republic between 1808 and 1811. He also commanded the troops that fought against the French rule of Santo Domingo´s colony be ...

, with the area returning to Spanish rule in 1809 following the

Battle of Palo Hincado

The Battle of Palo Hincado (''Palo Hincado'' Stands for "Kneeling Stick") was the first major battle of the Spanish reconquest of Santo Domingo of the Spanish colonial Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, that was occupied by the French in the Sp ...

.

Unification of Hispaniola (1821–1844)

Beginning in 1821, President

Jean-Pierre Boyer

Jean-Pierre Boyer (15 February 1776 – 9 July 1850) was one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, and President of Haiti from 1818 to 1843. He reunited the north and south of the country into the Republic of Haiti in 1820 and also annex ...

, also an ''homme de couleur'' and successor to Pétion, reunified the island following the suicide of Henry Christophe.

After

Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

declared its independence from Spain on 30 November 1821, Boyer invaded, seeking to

unite the entire island by force and ending slavery in Santo Domingo.

Struggling to revive the agricultural economy to produce

commodity crops

A cash crop or profit crop is an agricultural crop which is grown to sell for profit. It is typically purchased by parties separate from a farm. The term is used to differentiate marketed crops from staple crop (or "subsistence crop") in subsist ...

, Boyer passed the Code Rural, which denied peasant laborers the right to leave the land, enter the towns, or start farms or shops of their own, causing much resentment as most peasants wished to have their own farms rather than work on plantations.

Starting in September 1824, more than 6,000

African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

migrated to Haiti, with transportation paid by an American philanthropic group similar in function to the

American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America until 1837, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the migration of freebor ...

and its efforts in

Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

. Many found the conditions too harsh and returned to the United States.

In July 1825,

King Charles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and Loui ...

of

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, during a period of restoration of the

French monarchy

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I () as the first ...

, sent a

fleet

Fleet may refer to:

Vehicles

*Fishing fleet

*Naval fleet

*Fleet vehicles, a pool of motor vehicles

*Fleet Aircraft, the aircraft manufacturing company

Places

Canada

*Fleet, Alberta, Canada, a hamlet

England

* The Fleet Lagoon, at Chesil Beach, ...

to reconquer Haiti. Under pressure, President Boyer agreed to a treaty by which France formally recognized the independence of the nation in exchange for

a payment of 150 million

francs

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

.

By an order of 17 April 1826, the King of France renounced his rights of sovereignty and formally recognized the independence of Haiti.

The enforced payments to France hampered Haiti's economic growth for years, exacerbated by the fact that many Western nations continued to refuse formal

diplomatic

Diplomatics (in American English, and in most anglophone countries), or diplomatic (in British English), is a scholarly discipline centred on the critical analysis of documents: especially, historical documents. It focuses on the conventions, p ...

recognition to Haiti; Britain recognized Haitian independence in 1833, and the United States not until 1862.

Haiti borrowed heavily from Western banks at extremely high interest rates to repay the debt. Although the amount of the reparations was reduced to 90 million in 1838, by 1900 80% of Haiti's government spending was debt repayment and the country did not finish repaying it until 1947.

Loss of the Spanish portion of the island

After losing the support of Haiti's elite, Boyer was ousted in 1843, with

Charles Rivière-Hérard

Charles Rivière-Hérard also known as Charles Hérard aîné (16 February 1789 – 31 August 1850) was an officer in the Haitian Army under Alexandre Pétion during his struggles against Henri Christophe. He was declared President of Haiti on ...

replacing him as president.

Nationalist Dominican forces in eastern Hispaniola led by

Juan Pablo Duarte

Juan Pablo Duarte y Díez (January 26, 1813 – July 15, 1876) was a Dominican military leader, writer, activist, and nationalist politician who was the foremost of the founding fathers of the Dominican Republic and bears the title of Father of ...

seized control of Santo Domingo on 27 February 1844.

The Haitian forces, unprepared for a significant uprising, capitulated to the rebels, effectively ending Haitian rule of eastern Hispaniola. In March Rivière-Hérard attempted to reimpose his authority, but the

Dominicans put up stiff opposition and inflicted heavy losses.

Rivière-Hérard was removed from office by the mulatto hierarchy and replaced with the aged general

Philippe Guerrier

Jean-Jacques Louis Philippe Guerrier, Duke of L'Avance, Count of Mirebalais (December 19, 1757 – April 15, 1845) was a career officer and general in the Haitian Army who became President of Haïti on May 3, 1844. He died in office on Apri ...

, who assumed the presidency on 3 May 1844.

Guerrier died in April 1845, and was succeeded by General

Jean-Louis Pierrot

Prince Jean-Louis Michel Paul Pierrot, Baron of Haïti (19 December 1761 - 18 February 1857) was a career officer general in the Haitian Army who also served as President of Haiti from 16 April 1845 to 1 March 1846.

Revolution

During the Haiti ...

.

Pierrot's most pressing duty as the new president was to check the incursions of the Dominicans, who were harassing the Haitian troops.

Dominican gunboats were also making depredations on Haiti's coasts.

President Pierrot decided to open a campaign against the Dominicans, whom he considered merely as insurgents, however the Haitian offensive of 1845 was stopped on the frontier.

On 1 January 1846 Pierrot announced a fresh campaign to reimpose Haitian suzerainty over eastern Hispaniola, but his officers and men greeted this fresh summons with contempt.

Thus, a month later – February 1846 – when Pierrot ordered his troops to march against the Dominicans, the Haitian army mutinied, and its soldiers proclaimed his overthrow as president of the republic.

With the war against the Dominicans having become very unpopular in Haiti, it was beyond the power of the new president, General

Jean-Baptiste Riché

Jean-Baptiste Riché, Count of Grande-Riviere-du-Nord (1780 – February 27, 1847) was a career officer and general in the Haitian Army. He was made President of Haiti on March 1, 1846.

Life

Riché was born free, the son of a prominent free ...

, to stage another invasion.

Second Empire (1849–1859)

On 27 February 1847, President Riché died after only a year in power and was replaced by an obscure officer, General

Faustin Soulouque

Faustin-Élie Soulouque (15 August 1782 – 3 August 1867) was a Haitian politician and military commander who served as President of Haiti from 1847 to 1849 and Emperor of Haiti from 1849 to 1859.

Soulouque was a general in the Haitian Army w ...

.

During the first two years of Soulouque's administration the conspiracies and opposition he faced in retaining power were so manifold that the Dominicans were given a further breathing space in which to consolidate their independence.

But, when in 1848 France finally recognized the Dominican Republic as a free and independent state and provisionally signed a treaty of peace, friendship, commerce and navigation, Haiti immediately protested, claiming the treaty was an attack upon their own security.

Soulouque decided to invade the new Republic before the French Government could ratify the treaty.

On 21 March 1849, Haitian soldiers attacked the Dominican garrison at

Las Matas. The demoralized defenders offered almost no resistance before abandoning their weapons. Soulouque pressed on, capturing

San Juan San Juan, Spanish for Saint John, may refer to:

Places Argentina

* San Juan Province, Argentina

* San Juan, Argentina, the capital of that province

* San Juan, Salta, a village in Iruya, Salta Province

* San Juan (Buenos Aires Underground), ...

. This left only the town of

Azua as the remaining Dominican stronghold between the Haitian army and the capital. On 6 April, Azua fell to the 18,000-strong Haitian army, with a 5,000-man Dominican counterattack failing to oust them.

The way to

Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

was now clear. But the news of discontent existing at Port-au-Prince, which reached Soulouque, arrested his further progress and caused him to return with the army to his capital.

Emboldened by the sudden retreat of the Haitian army, the Dominicans counter-attacked. Their flotilla went as far as

Dame-Marie, which they plundered and set on fire.

Soulouque, now self-proclaimed as Emperor Faustin I, decided to start a new campaign against them. In 1855, he again invaded the territory of the Dominican Republic. But owing to insufficient preparation, the army was soon in want of victuals and ammunition.

In spite of the bravery of the soldiers, the Emperor had once more to give up the idea of a unified island under Haitian control.

After this campaign, Britain and France intervened and obtained an armistice on behalf of the Dominicans, who declared independence as the Dominican Republic.

The sufferings endured by the soldiers during the campaign of 1855, and the losses and sacrifices inflicted on the country without yielding any compensation or any practical results provoked great discontent.

In 1858 a revolution began, led by General

Fabre Geffrard

Guillaume Fabre Nicolas Geffrard (19 September 1806 – 31 December 1878) was a Mulatto Haitians, mulatto general in the Haitian Military of Haiti, army and President of Haiti from 1859 until his deposition in 1867. On 18 April 1852, Fausti ...

, Duke of Tabara. In December of that year, Geffrard defeated the Imperial Army and seized control of most of the country.

As a result, the Emperor abdicated his throne on 15 January 1859. Refused aid by the French Legation, Faustin was taken into exile aboard a British warship on 22 January 1859, and General Geffrard succeeded him as president.

Late 19th century–early 20th century

The period following Soulouque's overthrow down to the turn of the century was a turbulent one for Haiti, with repeated bouts of political instability. President Geffrard was overthrown in a coup in 1867, as was his successor,

Sylvain Salnave

Sylvain Salnave (February 6, 1827 – January 15, 1870) was a Haitian general who served as the President of Haïti from 1867 to 1869. He was elected president after he led the overthrow of President Fabre Geffrard. During his term there were cons ...

, in 1869. Under the Presidency of

Michel Domingue

Michel Domingue served as the President of Haiti from 14 June 1874 to 15 April 1876.

Biography

Michel Domingue was born in Les Cayes in 1813. He graduated from military training and became commander of army units in Sud.

From 8 May 1868 to ...

(1874–76) relations with the Dominican Republic were dramatically improved by the signing of a treaty, in which both parties acknowledged the independence of the other, bringing an end to Haitian dreams of bringing the entirety of Hispaniola under their control. Some modernisation of the economy and infrastructure also occurred in this period, especially under the Presidencies of

Lysius Salomon

Louis Étienne Félicité Lysius Salomon (June 30, 1815 – October 19, 1888) was the President of Haiti from 1879 to 1888. Salomon is best remembered for instituting Haiti's first postal system and for his lively enthusiasm for Haiti's moderniz ...

(1879–1888) and

Florvil Hyppolite

Louis Mondestin Florvil Hyppolite (26 May 1828 – 24 March 1896) was a Haitian general and politician who served as the President of Haiti from 17 October 1889 to 24 March 1896.

Early life and career

Hyppolite was born in 1827 at Cap-Haïtien ...

(1889–1896).

Haiti's relations with outside powers were often strained. In 1889 the United States attempted to

force Haiti to permit the building of a naval base at

Môle Saint-Nicolas, which was firmly resisted by President Hyppolite.

In 1892 the

German government

The Federal Cabinet or Federal Government (german: link=no, Bundeskabinett or ') is the chief executive body of the Federal Republic of Germany. It consists of the Federal Chancellor and cabinet ministers. The fundamentals of the cabinet's or ...

supported suppression of the reform movement of

Anténor Firmin

Joseph Auguste Anténor Firmin (18 October 1850 – 19 September 1911), better known as Anténor Firmin, was a Haitian barrister and philosopher, pioneering anthropologist, journalist, and politician. Firmin is best known for his book ''De l'ég ...

, and in 1897, the Germans used

gunboat diplomacy

In international politics, the term gunboat diplomacy refers to the pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of conspicuous displays of naval power, implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare should terms not be agreeable to th ...

to intimidate and then humiliate the Haitian government of President

Tirésias Simon Sam

Paul Tirésias Augustin Simon Sam (May 15, 1835 – May 11, 1916) was the President of Haiti from 31 March 1896 to 12 May 1902. He resigned the presidency just before completing his six-year term.

Biography

Born in the year 1835, Tirésias Sim ...

(1896–1902) during the

Lüders Affair

The Lüders affair was a legal and diplomatic embarrassment to the Haitian government in 1897.

On September 21, 1897, Haitian police were looking for one Dorléus Présumé, who was accused of theft. They found him washing a coach in front of the ...

.

In the first decades of the 20th century, Haiti experienced great political instability and was heavily in debt to France, Germany and the United States. A series of short lived presidencies came and went: President

Pierre Nord Alexis

Pierre Nord Alexis (2 August 1820 – 1 May 1910) was President of Haiti from 17 December 1902 to 2 December 1908.

Early life

He was the son of a high-ranking official in the regime of Henri Christophe, and Blézine Georges, Christophe's illeg ...

was forced from power in 1908, as was his successor

François C. Antoine Simon

François C. Antoine Simon (a.k.a. Antoine Simon) (October 10, 1843 – March 10, 1923) was President of Haiti from 6 December 1908 to 3 August 1911.John Carlos Rowe, ''Literary culture and U.S. imperialism: from the Revolution to World War II'' ...

in 1911; President

Cincinnatus Leconte

Jean Jacques Dessalines Michel Cincinnatus Leconte (September 29, 1854 – August 8, 1912) was President of Haiti from August 15, 1911 until his death on August 8, 1912. He was the great-grandson of Jean-Jacques Dessalines—a leader of the Hait ...

(1911–12) was killed in a (possibly deliberate) explosion at the National Palace;

Michel Oreste

Michel Oreste Lafontant (April 8, 1859 – October 29, 1918) served as president of Haiti