The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied

Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

and

Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and S ...

during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and early medieval

Germanic language

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, E ...

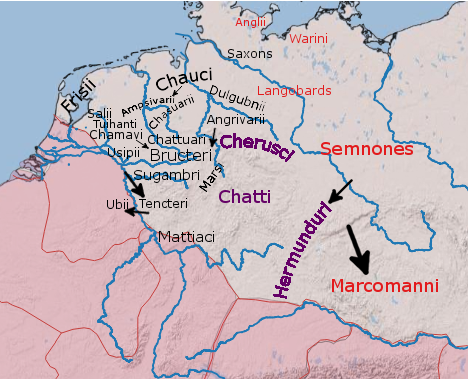

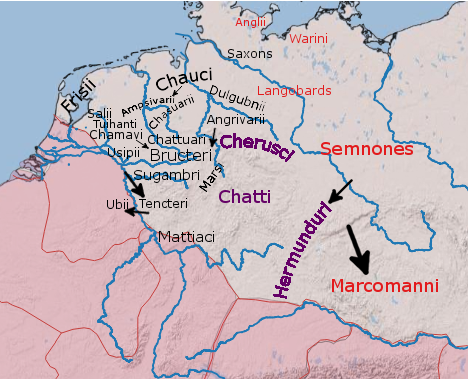

s and are thus equated at least approximately with Germanic-speaking peoples, although different academic disciplines have their own definitions of what makes someone or something "Germanic". The Romans named the area belonging to North-Central Europe in which Germanic peoples lived ''

Germania

Germania ( ; ), also called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a large historical region in north-c ...

'', stretching East to West between the

Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

and

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

rivers and north to south from Southern Scandinavia to the upper

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

. In discussions of the Roman period, the Germanic peoples are sometimes referred to as ''Germani'' or ancient Germans, although many scholars consider the second term problematic since it suggests identity with present-day

Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

. The very concept of "Germanic peoples" has become the subject of controversy among contemporary scholars. Some scholars call for its total abandonment as a modern construct since lumping "Germanic peoples" together implies a common group identity for which there is little evidence. Other scholars have defended the term's continued use and argue that a common Germanic language allows one to speak of "Germanic peoples", regardless of whether these ancient and medieval peoples saw themselves as having a common identity.

Scholars generally agree that it is possible to speak of Germanic peoples after 500 BCE. Archaeologists usually connect the early Germanic peoples with the

Jastorf culture

The Jastorf culture was an Iron Age material culture in what is now northern Germany and southern Scandinavia spanning the 6th to 1st centuries BC, forming part of the Pre-Roman Iron Age and associating with Germanic peoples. The culture evo ...

of the

Pre-Roman Iron Age

The archaeology of Northern Europe studies the prehistory of Scandinavia and the adjacent North European Plain,

roughly corresponding to the territories of modern Sweden, Norway, Denmark, northern Germany, Poland and the Netherlands.

The regio ...

, which is found in Denmark (southern Scandinavia) and northern Germany from the 6th to 1st centuries BCE, around the same time that the

first Germanic consonant shift is theorized to have occurred; this sound change lead to recognizably Germanic languages. From northern Germany and southern Scandinavia, the Germanic peoples expanded south, east, and west, coming into contact with the

Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

ic,

Iranic

The Iranian peoples or Iranic peoples are a diverse grouping of Indo-European peoples who are identified by their usage of the Iranian languages and other cultural similarities.

The Proto-Iranians are believed to have emerged as a separate ...

,

Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originatin ...

, and

Slavic peoples. Roman authors first described Germanic peoples near the Rhine in the 1st century BCE, while the Roman Empire was establishing its dominance in that region. Under Emperor

Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

(63 BCE–14CE), the Romans attempted to conquer a large area of Germania, but they withdrew after a major Roman defeat at the

Battle of the Teutoburg Forest

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, described as the Varian Disaster () by Roman historians, took place at modern Kalkriese in AD 9, when an alliance of Germanic peoples ambushed Roman legions and their auxiliaries, led by Publius Quinctilius ...

in 9 CE. The Romans continued to control the Germanic frontier closely by meddling in its politics, and they constructed a long fortified border, the

Limes Germanicus

The (Latin for ''Germanic frontier'') is the name given in modern times to a line of frontier () fortifications that bounded the ancient Roman provinces of Germania Inferior, Germania Superior and Raetia, dividing the Roman Empire and the unsubd ...

. From 166 to 180 CE, Rome was embroiled in a conflict against the Germanic

Marcomanni

The Marcomanni were a Germanic people

*

*

*

that established a powerful kingdom north of the Danube, somewhere near modern Bohemia, during the peak of power of the nearby Roman Empire. According to Tacitus and Strabo, they were Suebian.

O ...

,

Quadi

The Quadi were a Germanic

*

*

*

people who lived approximately in the area of modern Moravia in the time of the Roman Empire. The only surviving contemporary reports about the Germanic tribe are those of the Romans, whose empire had its bord ...

, and many other peoples known as the

Marcomannic Wars

The Marcomannic Wars (Latin: ''bellum Germanicum et Sarmaticum'', "German and Sarmatian War") were a series of wars lasting from about 166 until 180 AD. These wars pitted the Roman Empire against, principally, the Germanic Marcomanni and Quad ...

. The wars reordered the Germanic frontier, and afterwards, new Germanic peoples appear for the first time in the historical record, such as the

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools ...

,

Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Euro ...

,

Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

, and

Alemanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni, were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Caracalla of 213, the Alemanni captured the in 260, and later expanded into pres ...

. During the

Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roma ...

(375–568), various Germanic peoples entered the Roman Empire and eventually took control of parts of it and established their own

independent kingdoms after the collapse of Western Roman rule. The most powerful of them were the Franks, who conquered many of the others. Eventually, the Frankish king

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first E ...

claimed the title of

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

for himself in 800.

Archaeological finds suggest that Roman-era sources portrayed the Germanic way of life as more primitive than it actually was. Instead, archaeologists have unveiled evidence of a complex society and economy throughout Germania. Germanic-speaking peoples originally shared similar religious practices. Denoted by the term

Germanic paganism

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germ ...

, they varied throughout the territory occupied by Germanic-speaking peoples. Over the course of

Late Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English h ...

, most continental Germanic peoples and the

Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened ...

of Britain converted to Christianity, but the Saxons and

Scandinavians

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and ...

converted only much later. The Germanic peoples shared a native script from around the first century or before, the

runes

Runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write various Germanic languages (with some exceptions) before they adopted the Latin alphabet, and for specialised ...

, which was gradually replaced with the

Latin script

The Latin script, also known as Roman script, is an alphabetic writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae, in southern ...

, although runes continued to be used for specialized purposes thereafter.

Traditionally, the Germanic peoples have been seen as possessing a law dominated by the concepts of

feud

A feud , referred to in more extreme cases as a blood feud, vendetta, faida, clan war, gang war, or private war, is a long-running argument or fight, often between social groups of people, especially families or clans. Feuds begin because one par ...

ing and

blood compensation. The precise details, nature and origin of what is still normally called "Germanic law" are now controversial. Roman sources state that the Germanic peoples made decisions in a popular assembly (the

thing

Thing or The Thing may refer to:

Philosophy

* An object

* Broadly, an entity

* Thing-in-itself (or ''noumenon''), the reality that underlies perceptions, a term coined by Immanuel Kant

* Thing theory, a branch of critical theory that focuse ...

) but that they also had kings and war leaders. The ancient Germanic-speaking peoples probably shared a common poetic tradition,

alliterative verse

In prosody, alliterative verse is a form of verse that uses alliteration as the principal ornamental device to help indicate the underlying metrical structure, as opposed to other devices such as rhyme. The most commonly studied traditions of ...

, and later Germanic peoples also

shared legends originating in the Migration Period.

The publishing of

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

's ''Germania'' by

humanist scholars in the 1400s greatly influenced the emerging idea of "Germanic peoples". Later scholars of the

Romantic period

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

, such as

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm

The Brothers Grimm ( or ), Jacob (1785–1863) and Wilhelm (1786–1859), were a brother duo of German academics, philologists, cultural researchers, lexicographers, and authors who together collected and published folklore. They are among th ...

, developed several theories about the nature of the Germanic peoples that were highly influenced by

romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

. For those scholars, the "Germanic" and modern "German" were identical. Ideas about the early Germans were also highly influential among and were influenced and co-opted by the nationalist and racist

völkisch movement and later by the

Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

, which led in the second half of the 20th century to a backlash against many aspects of earlier scholarship.

Terminology

Etymology

The etymology of the Latin word , from which Latin and English Germanic are derived, is unknown, although several different proposals have been made for the origin of the name. Even the language from which it derives is a subject of dispute, with proposals of Germanic,

Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foo ...

, and Latin, and

Illyrian origins.

Herwig Wolfram

Herwig Wolfram (born 14 February 1934) is an Austrian historian who is Professor Emeritus of Medieval History and Auxiliary Sciences of History at the University of Vienna and the former Director of the . He is a leading member of the Vienna Sc ...

, for example, thinks must be

Gaulish

Gaulish was an ancient Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium, most of Switze ...

. The historian

Wolfgang Pfeifer more or less concurs with Wolfram and surmises that the name is likely of Celtic etymology and is related to the

Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic ( sga, Goídelc, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ga, Sean-Ghaeilge; gd, Seann-Ghàidhlig; gv, Shenn Yernish or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive writte ...

word ('neighbours') or could be tied to the Celtic word for their war cries, , which simplifies into 'the neighbours' or 'the screamers'. Regardless of its language of origin, the name was transmitted to the Romans via Celtic speakers.

It is unclear that any people group ever referred to themselves as ''Germani''. By

late antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English h ...

, only peoples near the Rhine, especially the

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools ...

and sometimes the Alemanni, were called ''Germani'' by Latin or Greek writers. ''Germani'' subsequently ceased to be used as a name for any group of people and was revived as such only by the

humanists

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

in the 16th century. Previously, scholars during the

Carolingian period

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippi ...

(8th–11th centuries) had already begun using ''Germania'' and ''Germanicus'' in a territorial sense to refer to

East Francia

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided the former empire int ...

.

In modern English, the adjective ''Germanic'' is distinct from ''German'', which is generally used when referring to modern Germans only. ''Germanic'' relates to the ancient ''Germani'' or the broader Germanic group. In modern German, the ancient ''Germani'' are referred to as and ''Germania'' as , as distinct from modern Germans () and modern Germany (). The direct equivalents in English are, however, ''Germans'' for ''Germani'' and ''Germany'' for ''Germania'' although the Latin is also used. To avoid ambiguity, the ''Germani'' may instead be called "ancient Germans" or ''Germani'' by using the Latin term in English.

Modern definitions and controversies

The modern definition of Germanic peoples developed in the 19th century, when the term ''Germanic'' was linked to the newly identified

Germanic language family

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, Engl ...

. Linguistics provided a new way of defining the Germanic peoples, which came to be used in historiography and archaeology. While Roman authors did not consistently exclude

Celtic-speaking people or have a term corresponding to Germanic-speaking peoples, this new definition—which used the Germanic language as the main criterion—presented the ''Germani'' as a people or nation () with a stable group identity linked to language. As a result, some scholars treat the (Latin) or (Greek) of Roman-era sources as non-Germanic if they seemingly spoke non-Germanic languages. For clarity, Germanic peoples, when defined as "speakers of a Germanic language", are sometimes referred to as "Germanic-speaking peoples". Today, the term "Germanic" is widely applied to "phenomena including identities, social, cultural or political groups, to material cultural artefacts, languages and texts, and even specific chemical sequences found in human DNA".

Apart from the designation of a language family (i.e., "Germanic languages"), the application of the term "Germanic" has become controversial in scholarship since 1990, especially among archaeologists and historians. Scholars have increasingly questioned the notion of ethnically defined people groups () as stable basic actors of history. The connection of archaeological assemblages to ethnicity has also been increasingly questioned. This has resulted in different disciplines developing different definitions of "Germanic". Beginning with the work of the "Toronto School" around

Walter Goffart

Walter Goffart (born February 22, 1934) is a German-born American historian who specializes in Late Antiquity and the European Middle Ages. He taught for many years in the History Department and Centre for Medieval Studies of the University of Tor ...

, various scholars have denied that anything such as a common Germanic ethnic identity ever existed. Such scholars argue that most ideas about Germanic culture are taken from far later epochs and projected backwards to antiquity. Historians of the Vienna School, such as

Walter Pohl, have also called for the term to be avoided or used with careful explanation, and argued that there is little evidence for a common Germanic identity. The Anglo-Saxonist

Leonard Neidorf writes that historians of the continental-European Germanic peoples of the 5th and 6th centuries are "in agreement" that there was no pan-Germanic identity or solidarity. Whether a scholar favors the existence of a common Germanic identity or not is often related to their position on the nature of the

end of the Roman Empire.

Defenders of continued use of the term ''Germanic'' argue that the speakers of Germanic languages can be identified as Germanic people by language regardless of how they saw themselves. Linguists and philologists have generally reacted skeptically to claims that there was no Germanic identity or cultural unity, and they may view ''Germanic'' simply as a long-established and convenient term. Some archaeologists have also argued in favor of retaining the term ''Germanic'' due to its broad recognizability. Archaeologist

Heiko Steuer

Heiko Steuer (born 30 October 1939) is a German archaeologist, notable for his research into social and economic history in early Europe. He serves as co-editor of Germanische Altertumskunde Online.

Career

Heiko Steuer was born on 30 October, 1 ...

defines his own work on the ''Germani'' in geographical terms (covering ''Germania''), rather than in ethnic terms. He nevertheless argues for some sense of shared identity between the ''Germani'', noting the use of a common language, a common

runic script

Runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write various Germanic languages (with some exceptions) before they adopted the Latin alphabet, and for specialised ...

, various common objects of material culture such as

bracteates

A bracteate (from the Latin ''bractea'', a thin piece of metal) is a flat, thin, single-sided gold medal worn as jewelry that was produced in Northern Europe predominantly during the Migration Period of the Germanic Iron Age (including the Vende ...

and

gullgubber

Gullgubber (Norwegian, ) or guldgubber ( Danish, ), guldgubbar (Swedish, ), are art-objects, amulets, or offerings found in Scandinavia and dating to the Nordic Iron Age. They consist of thin pieces of beaten gold (occasionally silver), usually ...

(small gold objects) and the confrontation with Rome as things that could cause a sense of shared "Germanic" culture. Despite being cautious of the use of ''Germanic'' to refer to peoples,

Sebastian Brather

Sebastian Brather (born 28 June 1964) is a German medieval archaeologist and co-editor of '' Germanische Altertumskunde Online''.

Career

Brather received his PhD in archaeology from the Humboldt University of Berlin in 1995 with a thesis '' Fe ...

,

Wilhelm Heizmann

Wilhelm Heizmann (born 5 September 1953) is a German philologist who is Professor and Chair of the Institute for Nordic Philology at the University of Munich. Heizmann specializes in Germanic studies, and is a co-editor of the ''Germanische Alte ...

and

Steffen Patzold

Steffen Patzold (born 1 September 1972) is a German historian. Patzold is Professor of Medieval History at the University of Tübingen and specializes in the study of the study of political and religious history of the Carolingian Empire.

Biograp ...

nevertheless refer to further commonalities such as the widely attested worship of deities such as

Odin

Odin (; from non, Óðinn, ) is a widely revered god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victory, ...

,

Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, ...

and

Frigg

Frigg (; Old Norse: ) is a goddess, one of the Æsir, in Germanic mythology. In Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about her, she is associated with marriage, prophecy, clairvoyance and motherhood, and dwells in the wet ...

, and a

shared legendary tradition.

Classical terminology

The first author to describe the ''Germani'' as a large category of peoples distinct from the

Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They sp ...

and

Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

was

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

, writing around 55 BCE during his governorship of Gaul. In Caesar's account, the clearest defining characteristic of the ''Germani'' people was that they lived east of the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

, opposite

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

on the west side. Caesar sought to explain both why his legions stopped at the Rhine and also why the ''Germani'' were more dangerous than the Gauls and a constant threat to the empire. He also classified the

Cimbri

The Cimbri (Greek Κίμβροι, ''Kímbroi''; Latin ''Cimbri'') were an ancient tribe in Europe. Ancient authors described them variously as a Celtic people (or Gaulish), Germanic people, or even Cimmerian. Several ancient sources indicate ...

and

Teutons

The Teutons ( la, Teutones, , grc, Τεύτονες) were an ancient northern European tribe mentioned by Roman authors. The Teutons are best known for their participation, together with the Cimbri and other groups, in the Cimbrian War with th ...

, peoples who had previously invaded Italy, as ''Germani'', and examples of this threat to Rome. Although Caesar described the Rhine as the border between ''Germani'' and Celts, he also describes a group of people he identifies as ''Germani'' who live on the west bank of the Rhine in the northeast of Gall, the

Germani cisrhenani

The ''Germani cisrhenani'' (Latin '' cis- rhenanus'' "on this side of the Rhine", referring to the Roman or western side), or "Left bank ''Germani''", were a group of Germanic peoples who lived west of the Lower Rhine at the time of the Gallic W ...

. It is unclear if these ''Germani'' spoke a Germanic language. According to the Roman historian

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

in his ''Germania'' (c. 98 CE), it was among this group, specifically the

Tungri

The Tungri (or Tongri, or Tungrians) were a tribe, or group of tribes, who lived in the Belgic part of Gaul, during the times of the Roman Empire. Within the Roman Empire, their territory was called the ''Civitas Tungrorum''. They were described b ...

, that the name ''Germani'' first arose, and was spread to further groups. Tacitus continues to mention Germanic tribes on the west bank of the Rhine in the period of the early Empire. Caesar's division of the ''Germani'' from the Celts was not taken up by most writers in Greek.

Caesar and authors following him regarded Germania as stretching east of the Rhine for an indeterminate distance, bounded by the Baltic Sea and the

Hercynian Forest.

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

and Tacitus placed the eastern border at the

Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

. The Upper Danube served as a southern border. Between there and the Vistula Tacitus sketched an unclear boundary, describing Germania as separated in the south and east from the Dacians and the Sarmatians by mutual fear or mountains. This undefined eastern border is related to a lack of stable frontiers in this area such as were maintained by Roman armies along the Rhine and Danube. The geographer

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

(2nd century CE) applied the name

Germania magna

Germania ( ; ), also called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a large historical region in north- ...

("Greater Germania", gr, Γερμανία Μεγάλη) to this area, contrasting it with the Roman provinces of

Germania Prima and

Germania Secunda

Germania Inferior ("Lower Germania") was a Roman province from AD 85 until the province was renamed Germania Secunda in the fourth century, on the west bank of the Rhine bordering the North Sea. The capital of the province was Colonia Agrippin ...

(on the west bank of the Rhine). In modern scholarship, Germania magna is sometimes also called ("free Germania"), a name that became popular among German nationalists in the 19th century.

Caesar and, following him, Tacitus, depicted the ''Germani'' as sharing elements of a common culture. A small number of passages by Tacitus and other Roman authors (Caesar, Suetonius) mention Germanic tribes or individuals speaking a language distinct from Gaulish. For Tacitus (''Germania'' 43, 45, 46), language was a characteristic, but not defining feature of the Germanic peoples. Many of the ascribed ethnic characteristics of the ''Germani'' represented them as typically "barbarian", including the possession of stereotypical vices such as "wildness" and of virtues such as chastity. Tacitus was at times unsure whether a people were Germanic or not, expressing his uncertainty about the

Bastarnae

The Bastarnae ( Latin variants: ''Bastarni'', or ''Basternae''; grc, Βαστάρναι or Βαστέρναι) and Peucini ( grc, Πευκῖνοι) were two ancient peoples who between 200 BC and 300 AD inhabited areas north of the Roman front ...

, who he says looked like Sarmatians but spoke like the ''Germani'', about the

Osi and the

Cotini The Gotini (in Tacitus), who are generally equated to the Cotini in other sources, were a Gaulish tribe living during Roman times in the mountains approximately near the modern borders of the Czech Republic, Poland,

and Slovakia.

The spelling " ...

, and about the

Aesti

The Aesti (also Aestii, Astui or Aests) were an ancient people first described by the Roman historian Tacitus in his treatise ''Germania'' (circa 98 AD). According to Tacitus, the land of ''Aesti'' was located somewhere east of the ''Suiones'' (p ...

, who were like Suebi but spoke a different language. When defining the ''Germani'' ancient authors did not differentiate consistently between a territorial definition ("those living in ''Germania''") and an ethnic definition ("having Germanic ethnic characteristics"), although the two definitions did not always align.

The Romans did not regard the eastern Germanic speakers such as Goths, Gepids, and Vandals as ''Germani'', but rather connected them with other non-Germanic-speaking peoples such as the

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

,

Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

, and

Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the A ...

. Romans described these peoples, including those who did not speak a Germanic language, as "Gothic people" () and most often classified them as "Scythians". The writer

Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

, describing the Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Vandals, Alans, and Gepids, derived the Gothic peoples from the ancient

Getae

The Getae ( ) or Gets ( ; grc, Γέται, singular ) were a Thracian-related tribe that once inhabited the regions to either side of the Lower Danube, in what is today northern Bulgaria and southern Romania. Both the singular form ''Get'' an ...

and described them as sharing similar customs, beliefs, and a common language.

Subdivisions

Several ancient sources list subdivisions of the Germanic tribes. Writing in the first century CE,

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

lists five Germanic subgroups: the Vandili, the Inguaeones, the Istuaeones (living near the Rhine), the Hermiones (in the Germanic interior), and the Peucini Basternae (living on the lower Danube near the Dacians). In chapter 2 of the ''Germania'', written about a half-century later, Tacitus lists only three subgroups: the Ingvaeones (near the sea), the Hermiones (in the interior of Germania), and the Istvaeones (the remainder of the tribes); Tacitus says these groups each claimed descent from the god

Mannus

Mannus, according to the Roman writer Tacitus, was a figure in the creation myths of the Germanic tribes. Tacitus is the only source of these myths.

Tacitus wrote that Mannus was the son of Tuisto and the progenitor of the three Germanic tribe ...

, son of

Tuisto

According to Tacitus's '' Germania'' (AD 98), Tuisto (or Tuisco) is the legendary divine ancestor of the Germanic peoples. The figure remains the subject of some scholarly discussion, largely focused upon etymological connections and compariso ...

. Tacitus also mentions a second tradition that there were four sons of either Mannus or Tuisto from whom the groups of the Marsi, Gambrivi, Suebi, and Vandili claim descent. The Hermiones are also mentioned by

Pomponius Mela

Pomponius Mela, who wrote around AD 43, was the earliest Roman geographer. He was born in Tingentera (now Algeciras) and died AD 45.

His short work (''De situ orbis libri III.'') remained in use nearly to the year 1500. It occupies less ...

, but otherwise, these divisions do not appear in other ancient works on the ''Germani''.

There are a number of inconsistencies in the listing of Germanic subgroups by Tacitus and Pliny. While both Tacitus and Pliny mention some Scandinavian tribes, they are not integrated into the subdivisions. While Pliny lists the

Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own name ...

as part of the Hermiones, Tacitus treats them as a separate group. Additionally, Tacitus's description of a group of tribes as united by the cult of

Nerthus

In Germanic paganism, Nerthus is a goddess associated with a ceremonial wagon procession. Nerthus is attested by first century AD Roman historian Tacitus in his ethnographic work ''Germania''.

In ''Germania'', Tacitus records that a group of Germ ...

(''Germania'' 40) as well as the cult of the

Alcis controlled by the

Nahanarvali The Nahanarvali, also known as the Nahavali, Naha-Narvali, and Nahanavali, were a Germanic tribe mentioned by the Roman scholar Tacitus in his ''Germania''.

According to Tacitus, the Nahanarvali were one of the five most powerful tribes of the Lugi ...

(''Germania'' 43) and Tacitus's account of the origin myth of the

Semnones

The Semnones were a Germanic and specifically a Suevian people, who were settled between the Elbe and the Oder in the 1st century when they were described by Tacitus in ''Germania'':

"The Semnones give themselves out to be the most ancient and r ...

(''Germania'' 39) all suggest different subdivisions than the three mentioned in ''Germania'' chapter 2.

The subdivisions found in Pliny and Tacitus have been very influential for scholarship on Germanic history and language up until recent times. However, outside of Tacitus and Pliny there are no other textual indications that these groups were important. The subgroups mentioned by Tacitus are not used by him elsewhere in his work, contradict other parts of his work, and cannot be reconciled with Pliny, who is equally inconsistent. Additionally, there is no linguistic or archaeological evidence for these subgroups. New archaeological finds have tended to show that the boundaries between Germanic peoples were very permeable, and scholars now assume that migration and the collapse and formation of cultural units were constant occurrences within Germania. Nevertheless, various aspects such as the alliteration of many of the tribal names in Tacitus's account and the name of Mannus himself suggest that the descent from Mannus was an authentic Germanic tradition.

Languages

Proto-Germanic

All

Germanic languages

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, ...

derive from the

Proto-Indo-European language

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo-E ...

(PIE), which is generally thought to have been spoken between 4500 and 2500 BCE. The ancestor of Germanic languages is referred to as

Proto- or Common Germanic, and likely represented a group of mutually intelligible

dialect

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety of a language that is ...

s. They share distinctive characteristics which set them apart from other Indo-European sub-families of languages, such as

Grimm's and

Verner's law

Verner's law describes a historical sound change in the Proto-Germanic language whereby consonants that would usually have been the voiceless fricatives , , , , , following an unstressed syllable, became the voiced fricatives , , , , . The law w ...

, the conservation of the PIE

ablaut

In linguistics, the Indo-European ablaut (, from German '' Ablaut'' ) is a system of apophony (regular vowel variations) in the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE).

An example of ablaut in English is the strong verb ''sing, sang, sung'' and its ...

system in the

Germanic verb system (notably in

strong verbs), or the merger of the vowels ''a'' and ''o'' qualities (''ə'', ''a'', ''o'' > ''a;'' ''ā'', ''ō'' > ''ō''). During the

Pre-Germanic linguistic period (2500–500 BCE), the

proto-language

In the tree model of historical linguistics, a proto-language is a postulated ancestral language from which a number of attested languages are believed to have descended by evolution, forming a language family. Proto-languages are usually unattes ...

has almost certainly been influenced by

an unknown non-Indo-European language, still noticeable in the Germanic

phonology

Phonology is the branch of linguistics that studies how languages or dialects systematically organize their sounds or, for sign languages, their constituent parts of signs. The term can also refer specifically to the sound or sign system of a ...

and

lexicon

A lexicon is the vocabulary of a language or branch of knowledge (such as nautical or medical). In linguistics, a lexicon is a language's inventory of lexemes. The word ''lexicon'' derives from Greek word (), neuter of () meaning 'of or fo ...

.

Although Proto-Germanic is reconstructed without dialects via the

comparative method

In linguistics, the comparative method is a technique for studying the development of languages by performing a feature-by-feature comparison of two or more languages with common descent from a shared ancestor and then extrapolating backwards t ...

, it is almost certain that it never was a uniform proto-language. The late Jastorf culture occupied so much territory that it is unlikely that Germanic populations spoke a single dialect, and traces of early linguistic varieties have been highlighted by scholars. Sister dialects of Proto-Germanic itself certainly existed, as evidenced by the absence of the First Germanic Sound Shift (Grimm's law) in some "Para-Germanic" recorded proper names, and the reconstructed Proto-Germanic language was only one among several dialects spoken at that time by peoples identified as "Germanic" by Roman sources or archeological data. Although Roman sources name various Germanic tribes such as Suevi, Alemanni,

Bauivari, etc., it is unlikely that the members of these tribes all spoke the same dialect.

Early attestations

Definite and comprehensive evidence of Germanic lexical units only occurred after

Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

's conquest of

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

in the 1st century BCE, after which contacts with Proto-Germanic speakers began to intensify. The ''

Alcis'', a pair of brother gods worshipped by the

Nahanarvali The Nahanarvali, also known as the Nahavali, Naha-Narvali, and Nahanavali, were a Germanic tribe mentioned by the Roman scholar Tacitus in his ''Germania''.

According to Tacitus, the Nahanarvali were one of the five most powerful tribes of the Lugi ...

, are given by Tacitus as a Latinized form of (a kind of '

stag'), and the word ('hair dye') is certainly borrowed from Proto-Germanic (English ''

soap

Soap is a salt of a fatty acid used in a variety of cleansing and lubricating products. In a domestic setting, soaps are surfactants usually used for washing, bathing, and other types of housekeeping. In industrial settings, soaps are us ...

)'', as evidenced by the parallel Finnish loanword ''.'' The name of the ''

framea'', described by Tacitus as a short spear carried by Germanic warriors, most likely derives from the

compound

Compound may refer to:

Architecture and built environments

* Compound (enclosure), a cluster of buildings having a shared purpose, usually inside a fence or wall

** Compound (fortification), a version of the above fortified with defensive struc ...

('forward-going one'), as suggested by comparable semantical structures found in early

runes

Runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write various Germanic languages (with some exceptions) before they adopted the Latin alphabet, and for specialised ...

(e.g., ''raun-ij-az'' 'tester', on a lancehead) and

linguistic cognates attested in the later

Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlement ...

,

Old Saxon

Old Saxon, also known as Old Low German, was a Germanic language and the earliest recorded form of Low German (spoken nowadays in Northern Germany, the northeastern Netherlands, southern Denmark, the Americas and parts of Eastern Europe). I ...

and

Old High German

Old High German (OHG; german: Althochdeutsch (Ahd.)) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally covering the period from around 750 to 1050.

There is no standardised or supra-regional form of German at this period, and Old Hig ...

languages: '','' and all mean 'to carry out'.

In the absence of earlier evidence, it must be assumed that Proto-Germanic speakers living in ''Germania'' were members of preliterate societies. The only pre-Roman inscriptions that could be interpreted as Proto-Germanic, written in the

Etruscan alphabet

The Etruscan alphabet was the alphabet used by the Etruscans, an ancient civilization of central and northern Italy, to write their language, from about 700 BC to sometime around 100 AD.

The Etruscan alphabet derives from the Euboean alphab ...

, have not been found in ''Germania'' but rather in the Venetic region. The inscription ''harikastiteiva

\\\ip'', engraved on the

Negau helmet

The Negau helmets are 26 bronze helmets (23 of which are preserved) dating to c. 450 BC–350 BC, found in 1812 in a cache in Ženjak, near Negau, Duchy of Styria (now Negova, Slovenia). The helmets are of typical Etruscan ' vetulonic' shape, ...

in the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE, possibly by a Germanic-speaking warrior involved in combat in northern Italy, has been interpreted by some scholars as ''Harigasti Teiwǣ'' ( 'army-guest' + 'god, deity'), which could be an invocation to a war-god or a mark of ownership engraved by its possessor.

The inscription ''Fariarix'' ( 'ferry' + 'ruler') carved on

tetradrachm

The tetradrachm ( grc-gre, τετράδραχμον, tetrádrachmon) was a large silver coin that originated in Ancient Greece. It was nominally equivalent to four drachmae. Over time the tetradrachm effectively became the standard coin of the An ...

s found in

Bratislava

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approximately 140% of ...

(mid-1st c. BCE) may indicate the Germanic name of a Celtic ruler.

Linguistic disintegration

By the time Germanic speakers entered written history, their linguistic territory had stretched farther south, since a Germanic

dialect continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulate over distance so that widely separated vari ...

(where neighbouring language varieties diverged only slightly between each other, but remote dialects were not necessarily

mutually intelligible

In linguistics, mutual intelligibility is a relationship between languages or dialects in which speakers of different but related varieties can readily understand each other without prior familiarity or special effort. It is sometimes used as a ...

due to accumulated differences over the distance) covered a region roughly located between the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

, the

Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

, the

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

, and southern

Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and S ...

during the first two centuries of the

Common Era

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

. East Germanic speakers dwelled on the Baltic sea coasts and islands, while speakers of the Northwestern dialects occupied territories in present-day Denmark and bordering parts of Germany at the earliest date when they can be identified.

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, migrations of East Germanic ''gentes'' from the Baltic Sea coast southeastwards into the hinterland led to their separation from the dialect continuum.

[; ; ; .] By the late 3rd century CE, linguistic divergences like the West Germanic loss of the final consonant ''-z'' had already occurred within the "residual" Northwest dialect continuum. The latter definitely ended after the 5th- and 6th-century migrations of

Angles

The Angles ( ang, Ængle, ; la, Angli) were one of the main Germanic peoples who settled in Great Britain in the post-Roman period. They founded several kingdoms of the Heptarchy in Anglo-Saxon England. Their name is the root of the name ...

,

Jutes

The Jutes (), Iuti, or Iutæ ( da, Jyder, non, Jótar, ang, Ēotas) were one of the Germanic tribes who settled in Great Britain after the departure of the Romans. According to Bede, they were one of the three most powerful Germanic nation ...

and part of the

Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

tribes towards modern-day England.

Classification

The Germanic languages are traditionally divided between

East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fac ...

,

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

and

West Germanic

The West Germanic languages constitute the largest of the three branches of the Germanic family of languages (the others being the North Germanic and the extinct East Germanic languages). The West Germanic branch is classically subdivided into ...

branches. The modern prevailing view is that North and West Germanic were also encompassed in a larger subgroup called Northwest Germanic.

*

Northwest Germanic

Northwest Germanic is a proposed grouping of the Germanic languages, representing the current consensus among Germanic historical linguists. It does not challenge the late 19th-century tri-partite division of the Germanic dialects into North Germ ...

: mainly characterized by the

''i''-umlaut, and the shift of the long vowel ''*ē'' towards a long ''*ā'' in accented syllables; it remained a

dialect continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulate over distance so that widely separated vari ...

following the migration of East Germanic speakers in the 2nd–3rd century CE;

**

North Germanic

The North Germanic languages make up one of the three branches of the Germanic languages—a sub-family of the Indo-European languages—along with the West Germanic languages and the extinct East Germanic languages. The language group is also r ...

or

Primitive Norse: initially characterized by the

monophthongization

Monophthongization is a sound change by which a diphthong becomes a monophthong, a type of vowel shift. It is also known as ungliding, as diphthongs are also known as gliding vowels. In languages that have undergone monophthongization, digraphs ...

of the sound ''ai'' to ''ā'' (attested from ca. 400 BCE); a uniform northern dialect or ''koiné'' attested in runic inscriptions from the 2nd century CE onward, it remained practically unchanged until a transitional period that started in the late 5th century; and

Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlement ...

, a language attested by runic inscriptions written in the

Younger Fuþark from the beginning of the

Viking Age

The Viking Age () was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonizing, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. It followed the Migration Period and the Germ ...

(8th–9th centuries CE);

**

West Germanic

The West Germanic languages constitute the largest of the three branches of the Germanic family of languages (the others being the North Germanic and the extinct East Germanic languages). The West Germanic branch is classically subdivided into ...

: including

Old Saxon

Old Saxon, also known as Old Low German, was a Germanic language and the earliest recorded form of Low German (spoken nowadays in Northern Germany, the northeastern Netherlands, southern Denmark, the Americas and parts of Eastern Europe). I ...

(attested from the 5th c. CE),

Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

(late 5th c.),

Old Frisian

Old Frisian was a West Germanic language spoken between the 8th and 16th centuries along the North Sea coast, roughly between the mouths of the Rhine and Weser rivers. The Frisian settlers on the coast of South Jutland (today's Northern Fries ...

(6th c.),

Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

(6th c.),

Old High German

Old High German (OHG; german: Althochdeutsch (Ahd.)) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally covering the period from around 750 to 1050.

There is no standardised or supra-regional form of German at this period, and Old Hig ...

(6th c.), and possibly

Langobardic

Lombardic or Langobardic is an extinct West Germanic language that was spoken by the Lombards (), the Germanic people who settled in Italy in the sixth century. It was already declining by the seventh century because the invaders quickly adopt ...

(6th c.), which is only scarcely attested;

[; ] they are mainly characterized by the loss of the final consonant -''z'' (attested from the late 3rd century), and by the

''j''-consonant gemination (attested from ca. 400 BCE); early inscriptions from the West Germanic areas found on altars where votive offerings were made to the ''Matronae Vacallinehae'' (Matrons of Vacallina) in the

Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

dated to ca. 160–260 CE; West Germanic remained a "residual" dialect continuum until the

Anglo-Saxon migrations in the 5th–6th centuries CE;

*

East Germanic

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the ...

, of which only

Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

is attested by both

runic inscriptions

A runic inscription is an inscription made in one of the various runic alphabets. They generally contained practical information or memorials instead of magic or mythic stories. The body of runic inscriptions falls into the three categories of ...

(from the 3rd c. CE) and textual evidence (principally

Wulfila's Bible; ca. 350–380). It became extinct after the fall of the

Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to ...

in the early 8th century. The inclusion of the

Burgundian and

Vandalic language

Vandalic was the Germanic language spoken by the Vandals during roughly the 3rd to 6th centuries. It was probably closely related to Gothic, and, as such, is traditionally classified as an East Germanic language. Its attestation is very frag ...

s within the East Germanic group, while plausible, is still uncertain due to their scarce attestation. The latest attested East Germanic language,

Crimean Gothic

Crimean Gothic was an East Germanic language spoken by the Crimean Goths in some isolated locations in Crimea until the late 18th century.

Attestation

The existence of a Germanic dialect in Crimea is noted in a number of sources from the 9th ce ...

, has been partially recorded in the 16th century.

Further internal classifications are still debated among scholars, as it is unclear whether the internal features shared by several branches are due to early common innovations or to the later diffusion of local dialectal innovations.

History

Prehistory

The Germanic-speaking peoples speak an

Indo-European language

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Du ...

. The leading theory for the origin of Germanic languages, suggested by archaeological, linguistic and genetic evidence, postulates a diffusion of Indo-European languages from the

Pontic–Caspian steppe

The Pontic–Caspian steppe, formed by the Caspian steppe and the Pontic steppe, is the steppeland stretching from the northern shores of the Black Sea (the Pontus Euxinus of antiquity) to the northern area around the Caspian Sea. It extend ...

towards Northern Europe during the third millennium BCE, via linguistic contacts and migrations from the

Corded Ware culture

The Corded Ware culture comprises a broad archaeological horizon of Europe between ca. 3000 BC – 2350 BC, thus from the late Neolithic, through the Copper Age, and ending in the early Bronze Age. Corded Ware culture encompassed a v ...

towards modern-day Denmark, resulting in cultural mixing with the earlier

Funnelbeaker culture

The Funnel(-neck-)beaker culture, in short TRB or TBK (german: Trichter(-rand-)becherkultur, nl, Trechterbekercultuur; da, Tragtbægerkultur; ) was an archaeological culture in north-central Europe.

It developed as a technological merger of lo ...

. The subsequent culture of the

Nordic Bronze Age

The Nordic Bronze Age (also Northern Bronze Age, or Scandinavian Bronze Age) is a period of Scandinavian prehistory from c. 2000/1750–500 BC.

The Nordic Bronze Age culture emerged about 1750 BC as a continuation of the Battle Axe culture (th ...

(c. 2000/1750-c. 500 BCE) shows definite cultural and population continuities with later Germanic peoples, and is often supposed to have been the culture in which the

Germanic Parent Language

In historical linguistics, the Germanic parent language (GPL) includes the reconstructed languages in the Germanic group referred to as Pre-Germanic Indo-European (PreGmc), Early Proto-Germanic (EPGmc), and Late Proto-Germanic (LPGmc), spoken in t ...

, the predecessor of the Proto-Germanic language, developed. However, it is unclear whether these earlier peoples possessed any ethnic continuity with the later Germanic peoples.

Generally, scholars agree that it is possible to speak of Germanic-speaking peoples after 500 BCE, although the first attestation of the name ''Germani'' is not until much later. Between around 500 BCE and the beginning of the

Common Era

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

, archeological and linguistic evidence suggest that the ''

Urheimat

In historical linguistics, the homeland or ''Urheimat'' (, from German '' ur-'' "original" and ''Heimat'', home) of a proto-language is the region in which it was spoken before splitting into different daughter languages. A proto-language is the r ...

'' ('original homeland') of the

Proto-Germanic language

Proto-Germanic (abbreviated PGmc; also called Common Germanic) is the reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Germanic eventually developed from pre-Proto-Germanic into three Germanic br ...

, the ancestral idiom of all attested Germanic dialects, was primarily situated in the southern

Jutland peninsula

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

, from which Proto-Germanic speakers migrated towards bordering parts of Germany and along the sea-shores of the Baltic and the North Sea, an area corresponding to the extent of the

late Jastorf culture. If the Jastorf Culture is the origin of the Germanic peoples, then the Scandinavian peninsula would have become Germanic either via migration or assimilation over the course of the same period. Alternatively, has stressed that two other archaeological groups must have belonged to the ''Germani'', one on either side of the

Lower Rhine

The Lower Rhine (german: Niederrhein; kilometres 660 to 1,033 of the river Rhine) flows from Bonn, Germany, to the North Sea at Hook of Holland, Netherlands (including the Nederrijn or "Nether Rhine" within the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta); ...

and reaching to the

Weser

The Weser () is a river of Lower Saxony in north-west Germany. It begins at Hannoversch Münden through the confluence of the Werra and Fulda. It passes through the Hanseatic city of Bremen. Its mouth is further north against the ports o ...

, and another in Jutland and southern Scandinavia. These groups would thus show a "polycentric origin" for the Germanic peoples. The neighboring

Przeworsk culture

The Przeworsk culture () was an Iron Age material culture in the region of what is now Poland, that dates from the 3rd century BC to the 5th century AD. It takes its name from the town Przeworsk, near the village where the first artifacts w ...

in modern Poland is thought to possibly reflect a Germanic and

Slavic component. The identification of the Jastorf culture with the ''Germani'' has been criticized by

Sebastian Brather

Sebastian Brather (born 28 June 1964) is a German medieval archaeologist and co-editor of '' Germanische Altertumskunde Online''.

Career

Brather received his PhD in archaeology from the Humboldt University of Berlin in 1995 with a thesis '' Fe ...

, who notes that it seems to be missing areas such as southern Scandinavia and the Rhine-Weser area, which linguists argue to have been Germanic, while also not according with the Roman era definition of ''Germani'', which included Celtic-speaking peoples further south and west.

A category of evidence used to locate the Proto-Germanic homeland is founded on traces of early linguistic contacts with neighbouring languages. Germanic loanwords in the

Finnic and

Sámi languages

Sámi languages ( ), in English also rendered as Sami and Saami, are a group of Uralic languages spoken by the Sámi people in Northern Europe (in parts of northern Finland, Norway, Sweden, and extreme northwestern Russia). There are, dependin ...

have preserved archaic forms (e.g. Finnic ''kuningas'', from Proto-Germanic 'king'; ''rengas'', from 'ring'; etc.), with the older loan layers possibly dating back to an earlier period of intense contacts between pre-Germanic and

Finno-Permic (i.e.

Finno-Samic) speakers. Shared lexical innovations between

Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foo ...

and Germanic languages, concentrated in certain semantic domains such as religion and warfare, indicates intensive contacts between the ''Germani'' and

Celtic peoples

The Celts (, see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-Europea ...

, usually identified with the archaeological

La Tène culture

The La Tène culture (; ) was a European Iron Age culture. It developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from about 450 BC to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC), succeeding the early Iron Age Hallstatt culture without any defi ...

, found in southern Germany and the modern Czech Republic. Early contacts probably occurred during the Pre-Germanic and Pre-Celtic periods, dated to the 2nd millennium BCE, and the Celts appear to have had a large amount of influence on Germanic culture from up until the first century CE, which led to a high degree of Celtic-Germanic shared material culture and social organization. Some evidence of linguistic convergence between Germanic and

Italic languages

The Italic languages form a branch of the Indo-European language family, whose earliest known members were spoken on the Italian Peninsula in the first millennium BC. The most important of the ancient languages was Latin, the official languag ...

, whose ''Urheimat'' is supposed to have been situated north of the Alps before the 1st millennium BCE, have also been highlighted by scholars. Shared changes in their grammars also suggest early contacts between Germanic and

Balto-Slavic languages

The Balto-Slavic languages form a branch of the Indo-European family of languages, traditionally comprising the Baltic and Slavic languages. Baltic and Slavic languages share several linguistic traits not found in any other Indo-European branc ...

; however, some of these innovations are shared with Baltic only, which may point to linguistic contacts during a relatively late period, at any rate after the initial breakup of Balto-Slavic into

Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originatin ...

and

Slavic languages

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic, spoken during the ...

, with the similarities to Slavic being seen as remnants of Indo-European archaisms or the result of secondary contacts.

Earliest recorded history

According to some authors the

Bastarnae

The Bastarnae ( Latin variants: ''Bastarni'', or ''Basternae''; grc, Βαστάρναι or Βαστέρναι) and Peucini ( grc, Πευκῖνοι) were two ancient peoples who between 200 BC and 300 AD inhabited areas north of the Roman front ...

or

Peucini

The Bastarnae (Latin variants: ''Bastarni'', or ''Basternae''; grc, Βαστάρναι or Βαστέρναι) and Peucini ( grc, Πευκῖνοι) were two ancient peoples who between 200 BC and 300 AD inhabited areas north of the Roman fronti ...

were the first ''Germani'' to be encountered by the

Greco-Roman world

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were dir ...

and thus to be mentioned in historical records. They appear in historical sources going back as far as the 3rd century BCE through the 4th century CE. Another eastern people known from about 200 BCE, and sometimes believed to be Germanic-speaking, are the

Sciri

The Sciri, or Scirians, were a Germanic people. They are believed to have spoken an East Germanic language. Their name probably means "the pure ones".

The Sciri were mentioned already in the late 3rd century BC as participants in a raid on th ...

(Greek: ), who are recorded threatening the city of

Olbia

Olbia (, ; sc, Terranoa; sdn, Tarranoa) is a city and commune of 60,346 inhabitants (May 2018) in the Italian insular province of Sassari in northeastern Sardinia, Italy, in the historical region of Gallura. Called ''Olbia'' in the Roman age ...

on the Black Sea. Late in the 2nd century BCE, Roman and Greek sources recount the migrations of the Cimbri, Teutones and

Ambrones

The Ambrones ( grc, Ἄμβρωνες) were an ancient tribe mentioned by Roman authors. They are generally believed to have been a Germanic tribe from Jutland.

In the late 2nd century BC, along with the fellow Cimbri and Teutons, the Ambrone ...

whom Caesar later classified as Germanic. The movements of these groups through parts of

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

,

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and

Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hi ...

resulted in the

Cimbrian War

The Cimbrian or Cimbric War (113–101 BC) was fought between the Roman Republic and the Germanic and Celtic tribes of the Cimbri and the Teutons, Ambrones and Tigurini, who migrated from the Jutland peninsula into Roman controlled territory, ...

(113–101 BCE) against the Romans, in which the Teutons and Cimbri were victorious over several Roman armies but were ultimately defeated.

The first century BCE was a time of the expansion of Germanic-speaking peoples at the expense of Celtic-speaking polities in modern southern Germany and the Czech Republic. In 63 BCE,

Ariovistus

Ariovistus was a leader of the Suebi and other allied Germanic peoples in the second quarter of the 1st century BC. He and his followers took part in a war in Gaul, assisting the Arverni and Sequani in defeating their rivals, the Aedui. They the ...

, king of the

Suevi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own names ...

and a host of other peoples, led a force across the Rhine into Gaul to aid the

Sequani

The Sequani were a Gallic tribe dwelling in the upper river basin of the Arar river (Saône), the valley of the Doubs and the Jura Mountains during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Name

They are mentioned as ''Sequanos'' by Caesar (mi ...

against their enemies the

Aedui

The Aedui or Haedui (Gaulish: *''Aiduoi'', 'the Ardent'; grc, Aἴδουοι) were a Gallic tribe dwelling in the modern Burgundy region during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

The Aedui had an ambiguous relationship with the Roman Republic a ...

. The Suevi were victorious at the