Aesop's Fables on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of

When and how the fables arrived in and travelled from ancient Greece remains uncertain. Some cannot be dated any earlier than

When and how the fables arrived in and travelled from ancient Greece remains uncertain. Some cannot be dated any earlier than

The first extensive translation of Aesop into

The first extensive translation of Aesop into

The main impetus behind the translation of large collections of fables attributed to Aesop and translated into European languages came from an early printed publication in Germany. There had been many small selections in various languages during the Middle Ages but the first attempt at an exhaustive edition was made by Heinrich Steinhőwel in his ''Esopus'', published . This contained both Latin versions and German translations and also included a translation of Rinuccio da Castiglione (or d'Arezzo)'s version from the Greek of a life of Aesop (1448). Some 156 fables appear, collected from Romulus, Avianus and other sources, accompanied by a commentarial preface and moralising conclusion, and 205 woodcuts. Translations or versions based on Steinhöwel's book followed shortly in Italian (1479), French (1480), Czech (1480) and English (the Caxton edition of 1484) and were many times reprinted before the start of the 16th century. The Spanish version of 1489, ''La vida del Ysopet con sus fabulas hystoriadas'' was equally successful and often reprinted in both the Old and New World through three centuries.

Some fables were later treated creatively in collections of their own by authors in such a way that they became associated with their names rather than Aesop's. The most celebrated were

The main impetus behind the translation of large collections of fables attributed to Aesop and translated into European languages came from an early printed publication in Germany. There had been many small selections in various languages during the Middle Ages but the first attempt at an exhaustive edition was made by Heinrich Steinhőwel in his ''Esopus'', published . This contained both Latin versions and German translations and also included a translation of Rinuccio da Castiglione (or d'Arezzo)'s version from the Greek of a life of Aesop (1448). Some 156 fables appear, collected from Romulus, Avianus and other sources, accompanied by a commentarial preface and moralising conclusion, and 205 woodcuts. Translations or versions based on Steinhöwel's book followed shortly in Italian (1479), French (1480), Czech (1480) and English (the Caxton edition of 1484) and were many times reprinted before the start of the 16th century. The Spanish version of 1489, ''La vida del Ysopet con sus fabulas hystoriadas'' was equally successful and often reprinted in both the Old and New World through three centuries.

Some fables were later treated creatively in collections of their own by authors in such a way that they became associated with their names rather than Aesop's. The most celebrated were

Translations into the languages of South Asia began at the very start of the 19th century. ''The Oriental Fabulist'' (1803) contained roman script versions in

Translations into the languages of South Asia began at the very start of the 19th century. ''The Oriental Fabulist'' (1803) contained roman script versions in

Such adaptations to Caribbean

Such adaptations to Caribbean

The first printed version of Aesop's Fables in English was published on 26 March 1484, by

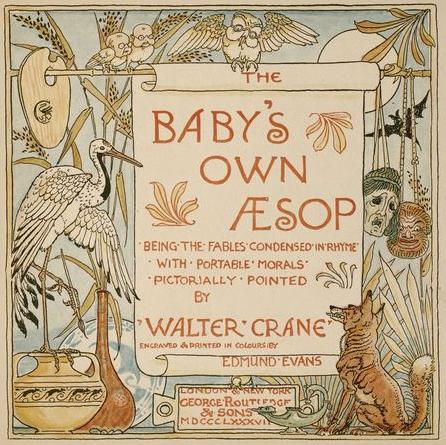

The first printed version of Aesop's Fables in English was published on 26 March 1484, by  Sharpe was also the originator of the limerick, but his versions of Aesop are in popular song measures and it was not until 1887 that the limerick form was ingeniously applied to the fables. This was in a magnificently hand-produced Arts and Crafts Movement edition, ''The Baby's Own Aesop: being the fables condensed in rhyme with portable morals pictorially pointed by

Sharpe was also the originator of the limerick, but his versions of Aesop are in popular song measures and it was not until 1887 that the limerick form was ingeniously applied to the fables. This was in a magnificently hand-produced Arts and Crafts Movement edition, ''The Baby's Own Aesop: being the fables condensed in rhyme with portable morals pictorially pointed by

Some fables may express open scepticism, as in the story of the man marketing a statue of Hermes who boasted of its effectiveness. Asked why he was disposing of such an asset, the huckster explains that the god takes his time in granting favours while he himself needs immediate cash. In another example, a farmer whose mattock has been stolen goes to a temple to see if the culprit can be found by divination. On his arrival he hears an announcement asking for information about a robbery at the temple and concludes that a god who cannot look after his own must be useless. But the contrary position, against reliance on religious ritual, was taken in fables like

Some fables may express open scepticism, as in the story of the man marketing a statue of Hermes who boasted of its effectiveness. Asked why he was disposing of such an asset, the huckster explains that the god takes his time in granting favours while he himself needs immediate cash. In another example, a farmer whose mattock has been stolen goes to a temple to see if the culprit can be found by divination. On his arrival he hears an announcement asking for information about a robbery at the temple and concludes that a god who cannot look after his own must be useless. But the contrary position, against reliance on religious ritual, was taken in fables like

''Esope à la cour'' is more of a moral satire, most scenes being set pieces for the application of fables to moral problems, but to supply romantic interest Aesop's mistress Rhodope is introduced. Among the sixteen fables included, only four derive from La Fontaine – The Heron and the Fish,

''Esope à la cour'' is more of a moral satire, most scenes being set pieces for the application of fables to moral problems, but to supply romantic interest Aesop's mistress Rhodope is introduced. Among the sixteen fables included, only four derive from La Fontaine – The Heron and the Fish,

A different strategy is to adapt the telling to popular musical genres. Australian musician David P Shortland chose ten fables for his recording ''Aesop Go HipHop'' (2012), where the stories are given a hip hop narration and the moral is underlined in a lyrical chorus. The American William Russo's approach to popularising his ''Aesop's Fables'' (1971) was to make of it a rock opera. This incorporates nine, each only introduced by the narrator before the music and characters take over. Instead of following the wording of one of the more standard fable collections, as other composers do, the performer speaks in character. Thus in "The Crow and the Fox" the bird introduces himself with, "Ahm not as pretty as mah friends and I can’t sing so good, but, uh, I can steal food pretty goddam good!" Other composers who have created operas for children have been Martin Kalmanoff in ''Aesop the fabulous fabulist'' (1969), David Ahlstom in his one-act ''Aesop's Fables'' (1986), and David Edgar Walther with his set of four "short operatic dramas", some of which were performed in 2009 and 2010. There have also been local ballet treatments of the fables for children in the US by such companies as Berkshire Ballet and Nashville Ballet.

A musical, ''Aesop's Fables'' by British playwright

A different strategy is to adapt the telling to popular musical genres. Australian musician David P Shortland chose ten fables for his recording ''Aesop Go HipHop'' (2012), where the stories are given a hip hop narration and the moral is underlined in a lyrical chorus. The American William Russo's approach to popularising his ''Aesop's Fables'' (1971) was to make of it a rock opera. This incorporates nine, each only introduced by the narrator before the music and characters take over. Instead of following the wording of one of the more standard fable collections, as other composers do, the performer speaks in character. Thus in "The Crow and the Fox" the bird introduces himself with, "Ahm not as pretty as mah friends and I can’t sing so good, but, uh, I can steal food pretty goddam good!" Other composers who have created operas for children have been Martin Kalmanoff in ''Aesop the fabulous fabulist'' (1969), David Ahlstom in his one-act ''Aesop's Fables'' (1986), and David Edgar Walther with his set of four "short operatic dramas", some of which were performed in 2009 and 2010. There have also been local ballet treatments of the fables for children in the US by such companies as Berkshire Ballet and Nashville Ballet.

A musical, ''Aesop's Fables'' by British playwright

"Aesop, Aristotle, and Animals: The Role of Fables in Human Life"

''Humanitas'', Volume XXI, Nos. 1 and 2, 2008, pp. 179–200. Bowie, Maryland: National Humanities Institute. * Gibbs, Laura (translator), 2002, reissued 2008. ''Aesop's Fables.'' Oxford University Press * Gibbs, Laura

"Aesop Illustrations: Telling the Story in Images"

* Rev.

Aesop's Fables: A New Version, Chiefly from Original Sources

1848. John Murray (includes many pictures by

Poésies en patois limousine

Paris 1866 * Temple, Olivia; Temple, Robert (translators), 1998

''Aesop, The Complete Fables,''

New York: Penguin Classics. ()

over 600 English fables, plus Caxton's Aesop, Latin and Greek texts, Content Index, and Site Search.

Children's Library, a site with many reproductions of illustrated English editions of Aesop

Fables of Aesop

English versions

Carlson Fable Collection at Creighton University

Includes online catalogue of fable-related objects

Vita et Aesopus moralisatus

esop's Fables, Italian and Latin.Naples: ermani fidelissimi forFrancesco del Tuppo, 13 February 1485. From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Esopus [Moralisatus].

Venice, Manfredus de Bonellis, de Monteferrato, 17 August 1493. From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Fabulae.

Naples, Cristannus Preller, . From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Esopo con la uita sua historiale euulgare.

Milan, Guillermi Le Signerre fratres, 15 September 1498. From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Fabule et vita Esopi, cum fabulis Auiani, Alfonsij, Pogij Florentini, et aliorum, cum optimo commento, bene diligenterque correcte et emendate.

Antwerp, Gerardus Leeu, 26 September 1486. From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Esopus constructus moralicatus Uenetijs, Impressum per B. Benalium

1517. From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Esopus cõnstructus moralizat

Taurini, B. Sylva, 1534 From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Aesopi Fabvlae cvm vvlgari interpretatione: Brixiae, Apud Loduicum Britannicum

1537. From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Aesop's fables. Latin. Esopi Appologi siue Mythologi cum quibusdam carminum et fabularum additionibus

1501. From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Aesop's fables. Spanish Libro del sabio [et] clarissimo fabulador Ysopu hystoriado et annotado. Sevilla, J. Cronberger

1521 From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Aesop's fables

German. Vita et Fabulae. Augsburg, Anton Sorg, . From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fable

Fable is a literary genre: a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse (poetry), verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are Anthropomorphism, anthropomorphized, and that illustrat ...

s credited to Aesop

Aesop ( or ; , ; c. 620–564 BCE) was a Greek fabulist and storyteller credited with a number of fables now collectively known as ''Aesop's Fables''. Although his existence remains unclear and no writings by him survive, numerous tales c ...

, a slave and storyteller believed to have lived in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of Classical Antiquity, classical antiquity ( AD 600), th ...

between 620 and 564 BCE. Of diverse origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

The fables originally belonged to oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985) ...

and were not collected for some three centuries after Aesop's death. By that time, a variety of other stories, jokes and proverbs were being ascribed to him, although some of that material was from sources earlier than him or came from beyond the Greek cultural sphere. The process of inclusion has continued until the present, with some of the fables unrecorded before the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Renai ...

and others arriving from outside Europe. The process is continuous and new stories are still being added to the Aesop corpus, even when they are demonstrably more recent work and sometimes from known authors.

Manuscripts in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

were important avenues of transmission, although poetical treatments in European vernaculars eventually formed another. On the arrival of printing, collections of Aesop's fables were among the earliest books in a variety of languages. Through the means of later collections, and translations or adaptations of them, Aesop's reputation as a fabulist was transmitted throughout the world.

Initially the fables were addressed to adults and covered religious, social and political themes. They were also put to use as ethical guides and from the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

onwards were particularly used for the education of children. Their ethical dimension was reinforced in the adult world through depiction in sculpture, painting and other illustrative means, as well as adaptation to drama and song. In addition, there have been reinterpretations of the meaning of fables and changes in emphasis over time.

Fictions that point to the truth

Fable as a genre

Apollonius of Tyana

Apollonius of Tyana ( grc, Ἀπολλώνιος ὁ Τυανεύς; c. 3 BC – c. 97 AD) was a Greek Neopythagorean philosopher from the town of Tyana in the Roman province of Cappadocia in Anatolia. He is the subject of '' ...

, a 1st-century CE philosopher, is recorded as having said about Aesop:

like those who dine well off the plainest dishes, he made use of humble incidents to teach great truths, and after serving up a story he adds to it the advice to do a thing or not to do it. Then, too, he was really more attached to truth than the poets are; for the latter do violence to their own stories in order to make them probable; but he by announcing a story which everyone knows not to be true, told the truth by the very fact that he did not claim to be relating real events.Earlier still, the Greek historian

Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

mentioned in passing that "Aesop the fable writer" was a slave who lived in Ancient Greece during the 5th century BCE. Among references in other writers, Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his for ...

, in his comedy ''The Wasps

''The Wasps'' ( grc-x-classical, Σφῆκες, translit=Sphēkes) is the fourth in chronological order of the eleven surviving plays by Aristophanes. It was produced at the Lenaia festival in 422 BC, during Athens' short-lived respite from the ...

'', represented the protagonist Philocleon as having learnt the "absurdities" of Aesop from conversation at banquets; Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

wrote in ''Phaedo

''Phædo'' or ''Phaedo'' (; el, Φαίδων, ''Phaidōn'' ), also known to ancient readers as ''On The Soul'', is one of the best-known dialogues of Plato's middle period, along with the '' Republic'' and the '' Symposium.'' The philosophica ...

''that Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

whiled away his time in prison turning some of Aesop's fables "which he knew" into verses. Nonetheless, for two main reasons – because numerous morals within Aesop's attributed fables contradict each other, and because ancient accounts of Aesop's life contradict each other – the modern view is that Aesop was not the originator of all those fables attributed to him. Instead, any fable tended to be ascribed to the name of Aesop if there was no known alternative literary source.

In Classical times there were various theorists who tried to differentiate these fables from other kinds of narration. They had to be short and unaffected; in addition, they are fictitious, useful to life and true to nature. In them could be found talking animals and plants, although humans interacting only with humans figure in a few. Typically they might begin with a contextual introduction, followed by the story, often with the moral underlined at the end. Setting the context was often necessary as a guide to the story's interpretation, as in the case of the political meaning of The Frogs Who Desired a King

The Frogs Who Desired a King is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 44 in the Perry Index. Throughout its history, the story has been given a political application.

The fable

According to the earliest source, Phaedrus, the story concerns a gro ...

and The Frogs and the Sun

The Frogs and the Sun is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 314 in the Perry Index. It has been given political applications since Classical times.

The fable

There are both Greek and Latin versions of the fable. Babrius tells it unadorned and ...

.

Sometimes the titles given later to the fables have become proverbial, as in the case of killing the Goose that Laid the Golden Eggs or the Town Mouse and the Country Mouse

"The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse" is one of Aesop's Fables. It is number 352 in the Perry Index and type 112 in Aarne–Thompson's folk tale index. Like several other elements in Aesop's fables, 'town mouse and country mouse' has become a ...

. In fact some fables, such as The Young Man and the Swallow

The young man and the swallow (which also has the Victorian title of "The spendthrift and the swallow") is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 169 in the Perry Index. It is associated with the ancient proverb 'One swallow doesn't make a summer'. ...

, appear to have been invented as illustrations of already existing proverbs. One theorist, indeed, went so far as to define fables as extended proverbs. In this they have an aetiological function, the explaining of origins such as, in another context, why the ant is a mean, thieving creature or how the tortoise got its shell. Other fables, also verging on this function, are outright jokes, as in the case of The Old Woman and the Doctor, aimed at greedy practitioners of medicine.

Origins

The contradictions between fables already mentioned and alternative versions of much the same fable – as in the case ofThe Woodcutter and the Trees

The title of The Woodcutter and the Trees covers a complex of fables that are of West Asian and Greek origins, the latter ascribed to Aesop. All of them concern the need to be wary of harming oneself through misplaced generosity.

The Fables Wester ...

, are best explained by the ascription to Aesop of all examples of the genre. Some are demonstrably of West Asian origin, others have analogues further to the East. Modern scholarship reveals fables and proverbs of Aesopic form existing in both ancient Sumer and Akkad, as early as the third millennium BCE

The 3rd millennium BC spanned the years 3000 through 2001 BC. This period of time corresponds to the Early to Middle Bronze Age, characterized by the early empires in the Ancient Near East. In Ancient Egypt, the Early Dynastic Period is followe ...

.John F. Priest, "The Dog in the Manger: In Quest of a Fable", in ''The Classical Journal'', Vol. 81, No. 1, (October–November 1985), pp. 49–58. Aesop's fables and the Indian tradition, as represented by the Buddhist ''Jataka tales

The Jātakas (meaning "Birth Story", "related to a birth") are a voluminous body of literature native to India which mainly concern the previous births of Gautama Buddha in both human and animal form. According to Peter Skilling, this genre is ...

'' and the Hindu '' Panchatantra'', share about a dozen tales in common, although often widely differing in detail. There is some debate over whether the Greeks learned these fables from Indian storytellers or the other way, or if the influences were mutual.

Loeb editor Ben E. Perry took the extreme position in his book ''Babrius and Phaedrus'' (1965) that

:in the entire Greek tradition there is not, so far as I can see, a single fable that can be said to come either directly or indirectly from an Indian source; but many fables or fable-motifs that first appear in Greek or Near Eastern literature are found later in the Panchatantra and other Indian story-books, including the Buddhist Jatakas.

Although Aesop and the Buddha were near contemporaries, the stories of neither were recorded in writing until some centuries after their death. Few disinterested scholars would now be prepared to make so absolute a stand as Perry about their origin in view of the conflicting and still emerging evidence.

Translation and transmission

Greek versions

When and how the fables arrived in and travelled from ancient Greece remains uncertain. Some cannot be dated any earlier than

When and how the fables arrived in and travelled from ancient Greece remains uncertain. Some cannot be dated any earlier than Babrius

Babrius ( grc-gre, Βάβριος, ''Bábrios''; century),"Babrius" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 21. also known as Babrias () or Gabrias (), was the author of a collection of Greek fables, many of whic ...

and Phaedrus, several centuries after Aesop, and yet others even later. The earliest mentioned collection was by Demetrius of Phalerum

Demetrius of Phalerum (also Demetrius of Phaleron or Demetrius Phalereus; grc-gre, Δημήτριος ὁ Φαληρεύς; c. 350 – c. 280 BC) was an Athenian orator originally from Phalerum, an ancient port of Athens. A student of Theophrast ...

, an Athenian orator and statesman of the 4th century BCE, who compiled the fables into a set of ten books for the use of orators. A follower of Aristotle, he simply catalogued all the fables that earlier Greek writers had used in isolation as exempla, putting them into prose. At least it was evidence of what was attributed to Aesop by others; but this may have included any ascription to him from the oral tradition in the way of animal fables, fictitious anecdotes, etiological or satirical myths, possibly even any proverb or joke, that these writers transmitted. It is more a proof of the power of Aesop's name to attract such stories to it than evidence of his actual authorship. In any case, although the work of Demetrius was mentioned frequently for the next twelve centuries, and was considered the official Aesop, no copy now survives. Present day collections evolved from the later Greek version of Babrius

Babrius ( grc-gre, Βάβριος, ''Bábrios''; century),"Babrius" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 21. also known as Babrias () or Gabrias (), was the author of a collection of Greek fables, many of whic ...

, of which there now exists an incomplete manuscript of some 160 fables in choliamb

Choliambic verse ( grc, χωλίαμβος), also known as limping iambs or scazons or halting iambic,. is a form of meter in poetry. It is found in both Greek and Latin poetry in the classical period. Choliambic verse is sometimes called ''scazo ...

ic verse. Current opinion is that he lived in the 1st century CE. The version of 55 fables in choliambic tetrameter

In poetry, a tetrameter is a line of four metrical feet. The particular foot can vary, as follows:

* '' Anapestic tetrameter:''

** "And the ''sheen'' of their ''spears'' was like ''stars'' on the ''sea''" (Lord Byron, "The Destruction of Sennach ...

s by the 9th century Ignatius the Deacon is also worth mentioning for its early inclusion of tales from Oriental sources.

Further light is thrown on the entry of Oriental stories into the Aesopic canon by their appearance in Jewish sources such as the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

and in Midrash

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

ic literature. There is a comparative list of these on the '' Jewish Encyclopedia'' website of which twelve resemble those that are common to both Greek and Indian sources, six are parallel to those only in Indian sources, and six others in Greek only. Where similar fables exist in Greece, India, and in the Talmud, the Talmudic form approaches more nearly the Indian. Thus, the fable " The Wolf and the Crane" is told in India of a lion and another bird. When Joshua ben Hananiah told that fable to the Jews, to prevent their rebelling against Rome and once more putting their heads into the lion's jaws (Gen. R. lxiv.), he shows familiarity with some form derived from India.

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

Latin versions

The first extensive translation of Aesop into

The first extensive translation of Aesop into Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

iambic trimeter

The Iambic trimeter is a meter of poetry consisting of three iambic units (each of two feet) per line.

In ancient Greek poetry and Latin poetry, an iambic trimeter is a quantitative meter, in which a line consists of three iambic ''metra''. Ea ...

s was performed by Phaedrus, a freedman of Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

in the 1st century CE, although at least one fable had already been translated by the poet Ennius

Quintus Ennius (; c. 239 – c. 169 BC) was a writer and poet who lived during the Roman Republic. He is often considered the father of Roman poetry. He was born in the small town of Rudiae, located near modern Lecce, Apulia, (Ancient Calabria ...

two centuries before, and others are referred to in the work of Horace. The rhetorician Aphthonius of Antioch

Aphthonius of Antioch ( el, Ἀφθόνιος Ἀντιοχεὺς ὁ Σύρος) was a Greek sophist and rhetorician who lived in the second half of the 4th century CE. Life

No information about his personal life is available except for his fri ...

wrote a technical treatise on, and converted into Latin prose, some forty of these fables in 315. It is notable as illustrating contemporary and later usage of fables in rhetorical practice. Teachers of philosophy and rhetoric often set the fables of Aesop as an exercise for their scholars, inviting them not only to discuss the moral of the tale, but also to practise style and the rules of grammar by making new versions of their own. A little later the poet Ausonius

Decimius Magnus Ausonius (; – c. 395) was a Roman poet and teacher of rhetoric from Burdigala in Aquitaine, modern Bordeaux, France. For a time he was tutor to the future emperor Gratian, who afterwards bestowed the consulship on him ...

handed down some of these fables in verse, which the writer Julianus Titianus translated into prose, and in the early 5th century Avianus

Avianus (or possibly Avienus;Alan Cameron, "Avienus or Avienius?", ''ZPE'' 108 (1995), p. 260 c. AD 400) a Latin writer of fables,"Avianus" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 5. identified as a pagan.

The ...

put 42 of these fables into Latin elegiacs The adjective ''elegiac'' has two possible meanings. First, it can refer to something of, relating to, or involving, an elegy or something that expresses similar mournfulness or sorrow. Second, it can refer more specifically to poetry composed in ...

.

The largest, oldest known and most influential of the prose versions of Phaedrus bears the name of an otherwise unknown fabulist named Romulus. It contains 83 fables, dates from the 10th century and seems to have been based on an earlier prose version which, under the name of "Aesop" and addressed to one Rufus, may have been written in the Carolingian period or even earlier. The collection became the source from which, during the second half of the Middle Ages, almost all the collections of Latin fables in prose and verse were wholly or partially drawn. A version of the first three books of Romulus in elegiac verse, possibly made around the 12th century, was one of the most highly influential texts in medieval Europe. Referred to variously (among other titles) as the verse Romulus or elegiac Romulus, and ascribed to Gualterus Anglicus

Gualterus Anglicus (Medieval Latin for Walter the Englishman) was an Anglo-Norman poet and scribe who produced a seminal version of ''Aesop's Fables'' (in distichs) around the year 1175.

Identification of the author

This author was earlier calle ...

, it was a common Latin teaching text and was popular well into the Renaissance. Another version of Romulus in Latin elegiacs was made by Alexander Neckam

Alexander Neckam (8 September 115731 March 1217) was an English magnetician, poet, theologian, and writer. He was an abbot of Cirencester Abbey from 1213 until his death.

Early life

Born on 8 September 1157 in St Albans, Alexander shared his b ...

, born at St Albans in 1157.

Interpretive "translations" of the elegiac Romulus were very common in Europe in the Middle Ages. Among the earliest was one in the 11th century by Ademar of Chabannes

Ademar is a masculine Germanic name, ultimately derived from ''Audamar'', as is the German form Otmar. It was in use in medieval France, Latinized as ''Adamarus'', and in modern times has been popular in French, Spanish and Portuguese-speaking cou ...

, which includes some new material. This was followed by a prose collection of parables by the Cistercian preacher Odo of Cheriton

Odo of Cheriton (1180/1190 – 1246/47) was an English preacher and fabulist who spent a considerable time studying in Paris and then lecturing in the south of France and in northern Spain.

Life and background

Odo belonged to a Norman family whic ...

around 1200 where the fables (many of which are not Aesopic) are given a strong medieval and clerical tinge. This interpretive tendency, and the inclusion of yet more non-Aesopic material, was to grow as versions in the various European vernaculars began to appear in the following centuries.

With the revival of literary Latin during the Renaissance, authors began compiling collections of fables in which those traditionally by Aesop and those from other sources appeared side by side. One of the earliest was by Lorenzo Bevilaqua, also known as Laurentius Abstemius

Laurentius Abstemius (c. 1440–1508) was an Italian writer and professor of philology, born at Macerata in Ancona. His learned name plays on his family name of Bevilaqua (Drinkwater), and he was also known by the Italian name Lorenzo Astemio. A ...

, who wrote 197 fables, the first hundred of which were published as ''Hecatomythium'' in 1495. Little by Aesop was included. At the most, some traditional fables are adapted and reinterpreted: The Lion and the Mouse

The Lion and the Mouse is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 150 in the Perry Index. There are also Eastern variants of the story, all of which demonstrate mutual dependence regardless of size or status. In the Renaissance the fable was provided w ...

is continued and given a new ending (fable 52); The Oak and the Reed becomes "The Elm and the Willow" (53); The Ant and the Grasshopper

The Ant and the Grasshopper, alternatively titled The Grasshopper and the Ant (or Ants), is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 373 in the Perry Index. The fable describes how a hungry grasshopper begs for food from an ant when winter comes and is ...

is adapted as "The Gnat and the Bee" (94) with the difference that the gnat offers to teach music to the bee's children. There are also Mediaeval tales such as The Mice in Council (195) and stories created to support popular proverbs such as 'Still Waters Run Deep

Still waters run deep is a proverb of Latin origin now commonly taken to mean that a placid exterior hides a passionate or subtle nature. Formerly it also carried the warning that silent people are dangerous, as in Suffolk's comment on a fellow lo ...

' (5) and 'A woman, an ass and a walnut tree' (65), where the latter refers back to Aesop's fable of The Walnut Tree

The Walnut Tree is one of Aesop's fables and numbered 250 in the Perry Index. It later served as a base for a misogynistic proverb, which encourages the violence against walnut trees, asses and women.

A fable of ingratitude

There are tw ...

. Most of the fables in ''Hecatomythium'' were later translated in the second half of Roger L'Estrange

Sir Roger L'Estrange (17 December 1616 – 11 December 1704) was an English pamphleteer, author, courtier, and press censor. Throughout his life L'Estrange was frequently mired in controversy and acted as a staunch ideological defender of Kin ...

's ''Fables of Aesop and other eminent mythologists'' (1692); some also appeared among the 102 in H. Clarke's Latin reader, ''Select fables of Aesop: with an English translation'' (1787), of which there were both English and American editions.

There were later three notable collections of fables in verse, among which the most influential was Gabriele Faerno

The humanist scholar Gabriele Faerno, also known by his Latin name of Faernus Cremonensis, was born in Cremona about 1510 and died in Rome on 17 November, 1561. He was a scrupulous textual editor and an elegant Latin poet who is best known now for ...

's ''Centum Fabulae'' (1564). The majority of the hundred fables there are Aesop's but there are also humorous tales such as The drowned woman and her husband (41) and The miller, his son and the donkey (100). In the same year that Faerno was published in Italy, Hieronymus Osius

Hieronymus Osius was a German Neo-Latin poet and academic about whom there are few biographical details. He was born about 1530 in Schlotheim and murdered in 1575 in Graz. After studying first at the university of Erfurt, he gained his master's ...

brought out a collection of 294 fables titled ''Fabulae Aesopi carmine elegiaco redditae'' in Germany. This too contained some from elsewhere, such as The Dog in the Manger

The story and metaphor of The Dog in the Manger derives from an old Greek fable which has been transmitted in several different versions. Interpreted variously over the centuries, the metaphor is now used to speak of one who spitefully prevents o ...

(67). Then in 1604 the Austrian Pantaleon Weiss, known as Pantaleon Candidus Pantaleon Candidus was a theologian of the Reformed Church and a Neo-Latin author. He was born on 7 October 1540 in Ybbs an der Donau and died on 3 February 1608 in Zweibrücken.

Life and works

Pantaleon Weiss was born the 14th child of a landown ...

, published ''Centum et Quinquaginta Fabulae''. The 152 poems there were grouped by subject, with sometimes more than one devoted to the same fable, although presenting alternative versions of it, as in the case of The Hawk and the Nightingale

The Hawk and the Nightingale is one of the earliest fables recorded in Greek and there have been many variations on the story since Classical times. The original version is numbered 4 in the Perry Index and the later Aesop version, sometimes going ...

(133–5). It also includes the earliest instance of The Lion, the Bear and the Fox (60) in a language other than Greek.

Another voluminous collection of fables in Latin verse was Anthony Alsop's ''Fabularum Aesopicarum Delectus'' (Oxford 1698). The bulk of the 237 fables there are prefaced by the text in Greek, while there are also a handful in Hebrew and in Arabic; the final fables, only attested from Latin sources, are without other versions. For the most part the poems are confined to a lean telling of the fable without drawing a moral.

Aesop in other languages

Europe

For many centuries the main transmission of Aesop's fables across Europe remained in Latin or else orally in various vernaculars, where they mixed with folk tales derived from other sources. This mixing is often apparent in early vernacular collections of fables in mediaeval times. * ''Ysopet

''Ysopet'' ("Little Aesop") refers to a medieval collection of fables in French literature, specifically to versions of Aesop's Fables. Alternatively the term Isopet-Avionnet indicates that the fables are drawn from both Aesop and Avianus.

The fa ...

'', an adaptation of some of the fables into Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intellig ...

octosyllabic couplets, was written by Marie de France

Marie de France (fl. 1160 to 1215) was a poet, possibly born in what is now France, who lived in England during the late 12th century. She lived and wrote at an unknown court, but she and her work were almost certainly known at the royal court o ...

in the 12th century. The morals with which she closes each fable reflect the feudal situation of her time.

* In the 13th century the Jewish author Berechiah ha-Nakdan

Berechiah ben Natronai Krespia ha-Nakdan ( he, ברכיה בן נטרונאי הנקדן; ) was a Jewish exegete, ethical writer, grammarian, translator, poet, and philosopher. His best-known works are '' Mishlè Shu'alim'' ("Fox Fables") and ''S ...

wrote ''Mishlei Shualim'', a collection of 103 'Fox Fables' in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

rhymed prose. This included many animal tales passing under the name of Aesop, as well as several more derived from Marie de France and others. Berechiah's work adds a layer of Biblical quotations and allusions to the tales, adapting them as a way to teach Jewish ethics. The first printed edition appeared in Mantua in 1557.

* ''Äsop'', an adaptation into Middle Low German

Middle Low German or Middle Saxon (autonym: ''Sassisch'', i.e. " Saxon", Standard High German: ', Modern Dutch: ') is a developmental stage of Low German. It developed from the Old Saxon language in the Middle Ages and has been documented i ...

verse of 125 Romulus fables, was written by Gerhard von Minden around 1370.

* ''Chwedlau Odo'' ("Odo's Tales") is a 14th-century Welsh version of the animal fables in Odo of Cheriton

Odo of Cheriton (1180/1190 – 1246/47) was an English preacher and fabulist who spent a considerable time studying in Paris and then lecturing in the south of France and in northern Spain.

Life and background

Odo belonged to a Norman family whic ...

's ''Parabolae'', not all of which are of Aesopic origin. Many show sympathy for the poor and oppressed, with often sharp criticisms of high-ranking church officials.

* Eustache Deschamps

Eustache Deschamps (13461406 or 1407) was a French poet, byname Morel, in French "Nightshade".

Life and career

Deschamps was born in Vertus. He received lessons in versification from Guillaume de Machaut and later studied law at Orleans Univers ...

included several of Aesop's fables among his moral ballades, written in Mediaeval French towards the end of the 14th century, in one of which there is mention of what 'Aesop tells in his book' (''Ysoppe dit en son livre et raconte''). In most, the telling of the fable precedes the drawing of a moral in terms of contemporary behaviour, but two comment on this with only contextual reference to fables not recounted in the text.

* ''Isopes Fabules'' was written in Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English ...

rhyme royal

Rhyme royal (or rime royal) is a rhyming stanza form that was introduced to English poetry by Geoffrey Chaucer. The form enjoyed significant success in the fifteenth century and into the sixteenth century. It has had a more subdued but continuing ...

stanzas by the monk John Lydgate

John Lydgate of Bury (c. 1370 – c. 1451) was an English monk and poet, born in Lidgate, near Haverhill, Suffolk, England.

Lydgate's poetic output is prodigious, amounting, at a conservative count, to about 145,000 lines. He explored and estab ...

towards the start of the 15th century. Seven tales are included and heavy emphasis is laid on the moral lessons to be learned from them.

* ''The Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian

''The Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian'' is a work of Northern Renaissance literature composed in Middle Scots by the fifteenth century Scottish makar, Robert Henryson. It is a cycle of thirteen connected narrative poems based on fables fr ...

'' was written in Middle Scots

Middle Scots was the Anglic language of Lowland Scotland in the period from 1450 to 1700. By the end of the 15th century, its phonology, orthography, accidence, syntax and vocabulary had diverged markedly from Early Scots, which was virtually ...

iambic pentameter

Iambic pentameter () is a type of metric line used in traditional English poetry and verse drama. The term describes the rhythm, or meter, established by the words in that line; rhythm is measured in small groups of syllables called " feet". "Iam ...

s by Robert Henryson

Robert Henryson (Middle Scots: Robert Henrysoun) was a poet who flourished in Scotland in the period c. 1460–1500. Counted among the Scots ''makars'', he lived in the royal burgh of Dunfermline and is a distinctive voice in the Northern Renai ...

about 1480. In the accepted text it consists of thirteen versions of fables, seven modelled on stories from "Aesop" expanded from the Latin Romulus manuscripts.

The main impetus behind the translation of large collections of fables attributed to Aesop and translated into European languages came from an early printed publication in Germany. There had been many small selections in various languages during the Middle Ages but the first attempt at an exhaustive edition was made by Heinrich Steinhőwel in his ''Esopus'', published . This contained both Latin versions and German translations and also included a translation of Rinuccio da Castiglione (or d'Arezzo)'s version from the Greek of a life of Aesop (1448). Some 156 fables appear, collected from Romulus, Avianus and other sources, accompanied by a commentarial preface and moralising conclusion, and 205 woodcuts. Translations or versions based on Steinhöwel's book followed shortly in Italian (1479), French (1480), Czech (1480) and English (the Caxton edition of 1484) and were many times reprinted before the start of the 16th century. The Spanish version of 1489, ''La vida del Ysopet con sus fabulas hystoriadas'' was equally successful and often reprinted in both the Old and New World through three centuries.

Some fables were later treated creatively in collections of their own by authors in such a way that they became associated with their names rather than Aesop's. The most celebrated were

The main impetus behind the translation of large collections of fables attributed to Aesop and translated into European languages came from an early printed publication in Germany. There had been many small selections in various languages during the Middle Ages but the first attempt at an exhaustive edition was made by Heinrich Steinhőwel in his ''Esopus'', published . This contained both Latin versions and German translations and also included a translation of Rinuccio da Castiglione (or d'Arezzo)'s version from the Greek of a life of Aesop (1448). Some 156 fables appear, collected from Romulus, Avianus and other sources, accompanied by a commentarial preface and moralising conclusion, and 205 woodcuts. Translations or versions based on Steinhöwel's book followed shortly in Italian (1479), French (1480), Czech (1480) and English (the Caxton edition of 1484) and were many times reprinted before the start of the 16th century. The Spanish version of 1489, ''La vida del Ysopet con sus fabulas hystoriadas'' was equally successful and often reprinted in both the Old and New World through three centuries.

Some fables were later treated creatively in collections of their own by authors in such a way that they became associated with their names rather than Aesop's. The most celebrated were La Fontaine's Fables

Jean de La Fontaine collected fables from a wide variety of sources, both Western and Eastern, and adapted them into French free verse. They were issued under the general title of Fables in several volumes from 1668 to 1694 and are considered cla ...

, published in French during the later 17th century. Inspired by the brevity and simplicity of Aesop's, those in the first six books were heavily dependent on traditional Aesopic material; fables in the next six were more diffuse and diverse in origin.

At the start of the 19th century, some of the fables were adapted into Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

, and often reinterpreted, by the fabulist

Fable is a literary genre: a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are anthropomorphized, and that illustrates or leads to a particular moral ...

Ivan Krylov

Ivan Andreyevich Krylov (russian: Ива́н Андре́евич Крыло́в; 13 February 1769 – 21 November 1844) is Russia's best-known fabulist and probably the most epigrammatic of all Russian authors. Formerly a dramatist and journali ...

. In most cases, but not all, these were dependent on La Fontaine's versions.

Asia and America

Translations into Asian languages at a very early date derive originally from Greek sources. These include the so-called ''Fables ofSyntipas

Syntipas ( el, Συντίπας) is the Greek form of a name also rendered Sindibad ( ar, سندباد), Sandbad ( fa, سندباد), Sendabar ( he, סנדבר), Çendubete (Spanish) and Siddhapati ( sa, सिद्धपति) in other versions ...

'', a compilation of Aesopic fables in Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages a ...

, dating from the 9/11th centuries. Included there were several other tales of possibly West Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

n origin. In Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

there was a 10th-century collection of the fables in Uighur.

After the Middle Ages, fables largely deriving from Latin sources were passed on by Europeans as part of their colonial or missionary enterprises. 47 fables were translated into the Nahuatl language in the late 16th century under the title ''In zazanilli in Esopo''. The work of a native translator, it adapted the stories to fit the Mexican environment, incorporating Aztec concepts and rituals and making them rhetorically more subtle than their Latin source.

Portuguese missionaries arriving in Japan at the end of the 16th century introduced Japan to the fables when a Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

edition was translated into romanized Japanese. The title was ''Esopo no Fabulas'' and dates to 1593. It was soon followed by a fuller translation into a three-volume kanazōshi entitled . This was the sole Western work to survive in later publication after the expulsion of Westerners from Japan, since by that time the figure of Aesop had been acculturated and presented as if he were Japanese. Coloured woodblock editions of individual fables were made by Kawanabe Kyosai in the 19th century.

The first translations of Aesop's Fables into the Chinese languages were made at the start of the 17th century, the first substantial collection being of 38 conveyed orally by a Jesuit missionary named Nicolas Trigault and written down by a Chinese academic named Zhang Geng (Chinese: 張賡; pinyin

Hanyu Pinyin (), often shortened to just pinyin, is the official romanization system for Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin Chinese in China, and to some extent, in Singapore and Malaysia. It is often used to teach Mandarin, normally writte ...

: ''Zhāng Gēng'') in 1625. This was followed two centuries later by ''Yishi Yuyan'' 《意拾喻言》 (''Esop's Fables: written in Chinese by the Learned Mun Mooy Seen-Shang, and compiled in their present form with a free and a literal translation'') in 1840 by Robert Thom and apparently based on the version by Roger L'Estrange

Sir Roger L'Estrange (17 December 1616 – 11 December 1704) was an English pamphleteer, author, courtier, and press censor. Throughout his life L'Estrange was frequently mired in controversy and acted as a staunch ideological defender of Kin ...

. This work was initially very popular until someone realised the fables were anti-authoritarian and the book was banned for a while. A little later, however, in the foreign concession in Shanghai, A.B. Cabaniss brought out a transliterated translation in Shanghai dialect, ''Yisuopu yu yan'' (伊娑菩喻言, 1856). There have also been 20th century translations by Zhou Zuoren

Zhou Zuoren () (16 January 1885 – 6 May 1967) was a Chinese writer, primarily known as an essayist and a translator. He was the younger brother of Lu Xun (Zhou Shuren, 周树人), the second of three brothers.

Biography

Early life

Born in S ...

and others.

Translations into the languages of South Asia began at the very start of the 19th century. ''The Oriental Fabulist'' (1803) contained roman script versions in

Translations into the languages of South Asia began at the very start of the 19th century. ''The Oriental Fabulist'' (1803) contained roman script versions in Bengali

Bengali or Bengalee, or Bengalese may refer to:

*something of, from, or related to Bengal, a large region in South Asia

* Bengalis, an ethnic and linguistic group of the region

* Bengali language, the language they speak

** Bengali alphabet, the w ...

, Hindi

Hindi ( Devanāgarī: or , ), or more precisely Modern Standard Hindi (Devanagari: ), is an Indo-Aryan language spoken chiefly in the Hindi Belt region encompassing parts of northern, central, eastern, and western India. Hindi has been ...

and Urdu

Urdu (;"Urdu"

'' Marathi Marathi may refer to: *Marathi people, an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group of Maharashtra, India *Marathi language, the Indo-Aryan language spoken by the Marathi people *Palaiosouda, also known as Marathi, a small island in Greece See also * * ...

(1806) and Bengali (1816), and then complete collections in Hindi (1837), '' Marathi Marathi may refer to: *Marathi people, an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group of Maharashtra, India *Marathi language, the Indo-Aryan language spoken by the Marathi people *Palaiosouda, also known as Marathi, a small island in Greece See also * * ...

Kannada

Kannada (; ಕನ್ನಡ, ), originally romanised Canarese, is a Dravidian language spoken predominantly by the people of Karnataka in southwestern India, with minorities in all neighbouring states. It has around 47 million native s ...

(1840), Urdu (1850), Tamil

Tamil may refer to:

* Tamils, an ethnic group native to India and some other parts of Asia

**Sri Lankan Tamils, Tamil people native to Sri Lanka also called ilankai tamils

**Tamil Malaysians, Tamil people native to Malaysia

* Tamil language, nativ ...

(1853) and Sindhi (1854).

In Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

, which had its own ethical folk tradition based on the Buddhist Jataka Tales

The Jātakas (meaning "Birth Story", "related to a birth") are a voluminous body of literature native to India which mainly concern the previous births of Gautama Buddha in both human and animal form. According to Peter Skilling, this genre is ...

, the joint Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or '' Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of '' Theravāda'' Buddh ...

and Burmese language

Burmese ( my, မြန်မာဘာသာ, MLCTS: ''mranmabhasa'', IPA: ) is a Sino-Tibetan language spoken in Myanmar (also known as Burma), where it is an official language, lingua franca, and the native language of the Burmans, the coun ...

translation of Aesop's fables was published in 1880 from Rangoon by the American Missionary Press. Outside the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

, Jagat Sundar Malla's translation into the Newar language of Nepal was published in 1915. Further to the west, the Afghani academic Hafiz Sahar

Hafiz Sahar (1928–1982) was an academic scholar, educator, author, Fulbright Scholar, and Professor of Journalism in both Afghanistan and United States Universities. He was Editor-in-Chief of Eslah national newspaper of Afghanistan (1955–195 ...

's translation of some 250 of Aesop's Fables into Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

was first published in 1972 under the name ''Luqman Hakim''.

Versions in regional languages

Minority expression

The 18th to 19th centuries saw a vast quantity of fables in verse being written in all European languages. Regional languages and dialects in the Romance area made use of versions adapted particularly from La Fontaine's recreations of ancient material. One of the earliest publications in France was the anonymous ''Fables Causides en Bers Gascouns'' (Selected fables in Gascon verse, Bayonne, 1776), which contained 106. Also in the vanguard was 's ''Quelques fables choisies de La Fontaine en patois limousin'' (109) in theOccitan Occitan may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Occitania territory in parts of France, Italy, Monaco and Spain.

* Something of, from, or related to the Occitania administrative region of France.

* Occitan language, spoken in parts o ...

Limousin dialect

Limousin (French name, ; oc, lemosin, ) is a dialect of the Occitan language, spoken in the three departments of Limousin, parts of Charente and the Dordogne in the southwest of France.

The first Occitan documents are in an early form of this ...

, originally with 39 fables, and ''Fables et contes en vers patois'' by , also published in the first decade of the 19th century in the neighbouring dialect of Montpellier. The last of these were very free recreations, with the occasional appeal directly to the original ''Maistre Ézôpa''. A later commentator noted that while the author could sometimes embroider his theme, at others he concentrated the sense to an Aesopean brevity.

Many translations were made into languages contiguous to or within the French borders. ''Ipui onak'' (1805) was the first translation of 50 fables of Aesop by the writer Bizenta Mogel Elgezabal into the Basque language spoken on the Spanish side of the Pyrenees. It was followed in mid-century by two translations on the French side: 50 fables in J-B. Archu's ''Choix de Fables de La Fontaine, traduites en vers basques'' (1848) and 150 in ''Fableac edo aleguiac Lafontenetaric berechiz hartuac'' (Bayonne, 1852) by Abbé Martin Goyhetche (1791–1859). Versions in Breton

Breton most often refers to:

*anything associated with Brittany, and generally

** Breton people

** Breton language, a Southwestern Brittonic Celtic language of the Indo-European language family, spoken in Brittany

** Breton (horse), a breed

**Ga ...

were written by Pierre Désiré de Goësbriand (1784–1853) in 1836 and Yves Louis Marie Combeau (1799–1870) between 1836 and 1838. The turn of Provençal came in 1859 with ''Li Boutoun de guèto, poésies patoises'' by Antoine Bigot

Antoine Hippolyte Bigot (February 27, 1825 in Nîmes – January 7, 1897 in Nîmes), was a French writer, poet, and translator in the Nîmes Provençal dialect of Occitan language, Occitan.

Born into a Protestantism, Protestant family, Antoine ...

(1825–1897), followed by several other collections of fables in the Nîmes dialect between 1881 and 1891. Alsatian dialect

Alsatian ( gsw-FR, Elsässisch, links=no or "Alsatian German"; Lorraine Franconian: ''Elsässerdeitsch''; french: Alsacien; german: Elsässisch or ) is the group of Alemannic German dialects spoken in most of Alsace, a formerly disputed region ...

versions of La Fontaine appeared in 1879 after the region was ceded away following the Franco-Prussian War. At the end of the following century, Brother Denis-Joseph Sibler (1920–2002) published a collection of adaptations (first recorded in 1983) that has gone through several impressions since 1995. The use of Corsican came later. Natale Rochicchioli (1911-2002) was particularly well known for his very free adaptations of La Fontaine, of which he made recordings as well as publishing his ''Favule di Natale'' in the 1970s.

During the 19th century renaissance of Belgian dialect literature in Walloon, several authors adapted versions of the fables to the racy speech (and subject matter) of Liège. They included (in 1842); Joseph Lamaye (1845); and the team of and François Bailleux, who between them covered all of La Fontaine’s books I-VI, (''Fåves da Lafontaine mettowes è ligeois'', 1850–56). Adaptations into other regional dialects were made by Charles Letellier (Mons, 1842) and Charles Wérotte (Namur, 1844); much later, Léon Bernus published some hundred imitations of La Fontaine in the dialect of Charleroi (1872); he was followed during the 1880s by , writing in the Borinage dialect under the pen-name Bosquètia. In the 20th century there has been a selection of fifty fables in the Condroz dialect by Joseph Houziaux (1946), to mention only the most prolific in an ongoing surge of adaptation.

The motive behind the later activity across these areas was to assert regional specificity against a growing centralism and the encroachment of the language of the capital on what had until then been predominantly monoglot areas. Surveying its literary manifestations, commentators have noted that the point of departure of the individual tales is not as important as what they become in the process. Even in the hands of less skilled dialect adaptations, La Fontaine's polished versions of the fables are returned to the folkloristic roots by which they often came to him in the first places. But many of the gifted regional authors were well aware of what they were doing in their work. In fitting the narration of the story to their local idiom, in appealing to the folk proverbs derived from such tales, and in adapting the story to local conditions and circumstances, the fables were so transposed as to go beyond bare equivalence, becoming independent works in their own right. Thus Emile Ruben claimed of the linguistic transmutations in Jean Foucaud's collection of fables that, "not content with translating, he has created a new work". In a similar way, the critic Maurice Piron described the Walloon versions of François Bailleux as "masterpieces of original imitation", and this is echoed in the claim that in Natale Rocchiccioli’s free Corsican versions too there is "more creation than adaptation".

In the 20th century there were also translations into regional dialects of English. These include the few examples in Addison Hibbard's ''Aesop in Negro Dialect'' (''American Speech'', 1926) and the 26 in Robert Stephen's ''Fables of Aesop in Scots Verse'' (Peterhead, Scotland, 1987), translated into the Aberdeenshire dialect. Glasgow University has also been responsible for R.W. Smith's modernised dialect translation of Robert Henryson's ''The Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian'' (1999, see above). The University of Illinois likewise included dialect translations by Norman Shapiro in its ''Creole echoes: the francophone poetry of nineteenth-century Louisiana'' (2004, see below).

Creole

Such adaptations to Caribbean

Such adaptations to Caribbean French-based creole languages

A French creole, or French-based creole language, is a creole for which French is the lexifier. Most often this lexifier is not modern French but rather a 17th- or 18th-century koiné of French from Paris, the French Atlantic harbors, and the ...

from the middle of the 19th century onward – initially as part of the colonialist project but later as an assertion of love for and pride in the dialect. A version of La Fontaine's fables in the dialect of Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in ...

was made by François-Achille Marbot (1817–1866) in ''Les Bambous, Fables de la Fontaine travesties en patois'' (Port Royal, 1846) which had lasting success. As well as two later editions in Martinique, there were two more published in France in 1870 and 1885 and others in the 20th century. Later dialect fables by Paul Baudot (1801–1870) from neighbouring Guadeloupe owed nothing to La Fontaine, but in 1869 some translated examples did appear in a grammar of Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

ian French creole written by John Jacob Thomas. Then the start of the new century saw the publication of Georges Sylvain's ''Cric? Crac! Fables de la Fontaine racontées par un montagnard haïtien et transcrites en vers créoles'' (La Fontaine's fables told by a Haiti highlander and written in creole verse, 1901).

On the South American mainland, Alfred de Saint-Quentin published a selection of fables freely adapted from La Fontaine into Guyanese creole in 1872. This was among a collection of poems and stories (with facing translations) in a book that also included a short history of the territory and an essay on creole grammar. On the other side of the Caribbean, Jules Choppin (1830–1914) was adapting La Fontaine to the Louisiana slave creole at the end of the 19th century in versions that are still appreciated. The New Orleans author Edgar Grima (1847–1939) also adapted La Fontaine into both standard French and into dialect.

Versions in the French creole of the islands in the Indian Ocean began somewhat earlier than in the Caribbean. (1801–1856) emigrated from Brittany to Réunion in 1820. Having become a schoolmaster, he adapted some of La Fontaine's fables into the local dialect in ''Fables créoles dédiées aux dames de l'île Bourbon'' (Creole fables for island women). This was published in 1829 and went through three editions. In addition 49 fables of La Fontaine were adapted to the Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, République des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, ...

dialect around 1900 by Rodolphine Young (1860–1932) but these remained unpublished until 1983. Jean-Louis Robert's recent translation of Babrius into Réunion creole

Réunion Creole, or Reunionese Creole ( rcf, kréol rénioné; french: créole réunionnais), is a French-based creole language spoken on Réunion. It is derived mainly from French and includes terms from Malagasy, Hindi, Portuguese, Gujarat ...

(2007) adds a further motive for such adaptation. Fables began as an expression of the slave culture and their background is in the simplicity of agrarian life. Creole transmits this experience with greater purity than the urbane language of the slave-owner.

Slang

Fables belong essentially to the oral tradition; they survive by being remembered and then retold in one's own words. When they are written down, particularly in the dominant language of instruction, they lose something of their essence. A strategy for reclaiming them is therefore to exploit the gap between the written and the spoken language. One of those who did this in English was SirRoger L'Estrange

Sir Roger L'Estrange (17 December 1616 – 11 December 1704) was an English pamphleteer, author, courtier, and press censor. Throughout his life L'Estrange was frequently mired in controversy and acted as a staunch ideological defender of Kin ...

, who translated the fables into the racy urban slang of his day and further underlined their purpose by including in his collection many of the subversive Latin fables of Laurentius Abstemius

Laurentius Abstemius (c. 1440–1508) was an Italian writer and professor of philology, born at Macerata in Ancona. His learned name plays on his family name of Bevilaqua (Drinkwater), and he was also known by the Italian name Lorenzo Astemio. A ...

. In France the fable tradition had already been renewed in the 17th century by La Fontaine's influential reinterpretations of Aesop and others. In the centuries that followed there were further reinterpretations through the medium of regional languages, which to those at the centre were regarded as little better than slang. Eventually, however, the demotic tongue of the cities themselves began to be appreciated as a literary medium.

One of the earliest examples of these urban slang translations was the series of individual fables contained in a single folded sheet, appearing under the title of ''Les Fables de Gibbs'' in 1929. Others written during the period were eventually anthologised as ''Fables de La Fontaine en argot'' (Étoile sur Rhône 1989). This followed the genre's growth in popularity after World War II. Two short selections of fables by Bernard Gelval about 1945 were succeeded by two selections of 15 fables each by 'Marcus' (Paris 1947, reprinted in 1958 and 2006), Api Condret's ''Recueil des fables en argot'' (Paris, 1951) and Géo Sandry (1897–1975) and Jean Kolb's ''Fables en argot'' (Paris 1950/60). The majority of such printings were privately produced leaflets and pamphlets, often sold by entertainers at their performances, and are difficult to date. Some of these poems then entered the repertoire of noted performers such as Boby Forest and Yves Deniaud, of which recordings were made. In the south of France, Georges Goudon published numerous folded sheets of fables in the post-war period. Described as monologues, they use Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, third-largest city and Urban area (France), second-largest metropolitan area of F ...

slang and the Mediterranean Lingua Franca

The Mediterranean Lingua Franca, or Sabir, was a pidgin language that was used as a lingua franca in the Mediterranean Basin from the 11th to the 19th centuries.

Etymology

''Lingua franca'' meant literally "Frankish language" in Late Latin, a ...

known as Sabir.

Slang versions by others continue to be produced in various parts of France, both in printed and recorded form.

Children

The first printed version of Aesop's Fables in English was published on 26 March 1484, by

The first printed version of Aesop's Fables in English was published on 26 March 1484, by William Caxton

William Caxton ( – ) was an English merchant, diplomat and writer. He is thought to be the first person to introduce a printing press into England, in 1476, and as a printer to be the first English retailer of printed books.

His parentage a ...

. Many others, in prose and verse, followed over the centuries. In the 20th century Ben E. Perry edited the Aesopic fables of Babrius and Phaedrus for the Loeb Classical Library and compiled a numbered index by type in 1952. Olivia and Robert Temple's Penguin edition is titled ''The Complete Fables by Aesop'' (1998) but in fact many from Babrius, Phaedrus and other major ancient sources have been omitted. More recently, in 2002 a translation by Laura Gibbs titled ''Aesop's Fables'' was published by Oxford World's Classics. This book includes 359 and has selections from all the major Greek and Latin sources.

Until the 18th century the fables were largely put to adult use by teachers, preachers, speech-makers and moralists. It was the philosopher John Locke who first seems to have advocated targeting children as a special audience in '' Some Thoughts Concerning Education'' (1693). Aesop's fables, in his opinion are

That young people are a special target for the fables was not a particularly new idea and a number of ingenious schemes for catering to that audience had already been put into practice in Europe. The ''Centum Fabulae'' of Gabriele Faerno

The humanist scholar Gabriele Faerno, also known by his Latin name of Faernus Cremonensis, was born in Cremona about 1510 and died in Rome on 17 November, 1561. He was a scrupulous textual editor and an elegant Latin poet who is best known now for ...

was commissioned by Pope Pius IV in the 16th century 'so that children might learn, at the same time and from the same book, both moral and linguistic purity'. When King Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ver ...

of France wanted to instruct his six-year-old son, he incorporated the series of hydraulic statues representing 38 chosen fables in the labyrinth of Versailles

The labyrinth of Versailles was a hedge maze in the Gardens of Versailles with groups of fountains and sculptures depicting Aesop's fables André Le Nôtre initially planned a maze of unadorned paths in 1665, but in 1669, Charles Perrault advi ...

in the 1670s. In this he had been advised by Charles Perrault, who was later to translate Faerno's widely published Latin poems into French verse and so bring them to a wider audience. Then in the 1730s appeared the eight volumes of ''Nouvelles Poésies Spirituelles et Morales sur les plus beaux airs'', the first six of which incorporated a section of fables specifically aimed at children. In this the fables of La Fontaine were rewritten to fit popular airs of the day and arranged for simple performance. The preface to this work comments that 'we consider ourselves happy if, in giving them an attraction to useful lessons which are suited to their age, we have given them an aversion to the profane songs which are often put into their mouths and which only serve to corrupt their innocence.' The work was popular and reprinted into the following century.

In Great Britain various authors began to develop this new market in the 18th century, giving a brief outline of the story and what was usually a longer commentary on its moral and practical meaning. The first of such works is Reverend Samuel Croxall

Samuel Croxall (c. 1690 – 1752) was an Anglican churchman, writer and translator, particularly noted for his edition of Aesop's Fables.

Early career

Samuel Croxall was born in Walton on Thames, where his father (also called Samuel) was vicar ...

's ''Fables of Aesop and Others, newly done into English with an Application to each Fable''. First published in 1722, with engravings for each fable by Elisha Kirkall

Elisha Kirkall (c.1682–1742) was a prolific English engraver, who made many experiments in printmaking techniques. He was noted for engravings on type metal that could be set up with letterpress for book illustrations, and was also known as a m ...

, it was continually reprinted into the second half of the 19th century. Another popular collection was John Newbery

John Newbery (9 July 1713 – 22 December 1767), considered "The Father of Children's Literature", was an English publisher of books who first made children's literature a sustainable and profitable part of the literary market. He also supported ...

's ''Fables in Verse for the Improvement of the Young and the Old'', facetiously attributed to Abraham Aesop Esquire, which was to see ten editions after its first publication in 1757. Robert Dodsley

Robert Dodsley (13 February 1703 – 23 September 1764) was an English bookseller, publisher, poet, playwright, and miscellaneous writer.

Life

Dodsley was born near Mansfield, Nottinghamshire, where his father was master of the free school.

H ...

's three-volume ''Select Fables of Esop and other Fabulists'' is distinguished for several reasons. First that it was printed in Birmingham by John Baskerville in 1761; second that it appealed to children by having the animals speak in character, the Lion in regal style, the Owl with 'pomp of phrase'; thirdly because it gathers into three sections fables from ancient sources, those that are more recent (including some borrowed from Jean de la Fontaine), and new stories of his own invention.

Thomas Bewick