Operas By Julian Philips on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Opera is a form of

Opera is a form of

The Italian word ''opera'' means "work", both in the sense of the labour done and the result produced. The Italian word derives from the Latin word ''

The Italian word ''opera'' means "work", both in the sense of the labour done and the result produced. The Italian word derives from the Latin word ''

Opera did not remain confined to court audiences for long. In 1637, the idea of a "season" (often during the

Opera did not remain confined to court audiences for long. In 1637, the idea of a "season" (often during the

Opera seria had its weaknesses and critics. The taste for embellishment on behalf of the superbly trained singers, and the use of spectacle as a replacement for dramatic purity and unity drew attacks.

Opera seria had its weaknesses and critics. The taste for embellishment on behalf of the superbly trained singers, and the use of spectacle as a replacement for dramatic purity and unity drew attacks.

The

The

Opera is a form of

Opera is a form of theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perform ...

in which music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and Defi ...

and a librettist and incorporates a number of the performing arts

The performing arts are arts such as music, dance, and drama which are performed for an audience. They are different from the visual arts, which are the use of paint, canvas or various materials to create physical or static art objects. Perform ...

, such as acting

Acting is an activity in which a story is told by means of its enactment by an actor or actress who adopts a character—in theatre, television, film, radio, or any other medium that makes use of the mimetic mode.

Acting involves a broad r ...

, scenery, costume

Costume is the distinctive style of dress or cosmetic of an individual or group that reflects class, gender, profession, ethnicity, nationality, activity or epoch. In short costume is a cultural visual of the people.

The term also was tradition ...

, and sometimes dance

Dance is a performing art form consisting of sequences of movement, either improvised or purposefully selected. This movement has aesthetic and often symbolic value. Dance can be categorized and described by its choreography, by its repertoir ...

or ballet

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form of ...

. The performance is typically given in an opera house

An opera house is a theatre building used for performances of opera. It usually includes a stage, an orchestra pit, audience seating, and backstage facilities for costumes and building sets.

While some venues are constructed specifically for o ...

, accompanied by an orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families.

There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* bowed string instruments, such as the violin, viola, c ...

or smaller musical ensemble

A musical ensemble, also known as a music group or musical group, is a group of people who perform instrumental and/or vocal music, with the ensemble typically known by a distinct name. Some music ensembles consist solely of instrumentalists, ...

, which since the early 19th century has been led by a conductor. Although musical theatre

Musical theatre is a form of theatrical performance that combines songs, spoken dialogue, acting and dance. The story and emotional content of a musical – humor, pathos, love, anger – are communicated through words, music, movemen ...

is closely related to opera, the two are considered to be distinct from one another.

Opera is a key part of the Western classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" also ...

tradition. Originally understood as an entirely sung piece, in contrast to a play with songs, opera has come to include numerous genres, including some that include spoken dialogue such as ''Singspiel

A Singspiel (; plural: ; ) is a form of German-language music drama, now regarded as a genre of opera. It is characterized by spoken dialogue, which is alternated with ensembles, songs, ballads, and arias which were often strophic, or folk-like ...

'' and ''Opéra comique

''Opéra comique'' (; plural: ''opéras comiques'') is a genre of French opera that contains spoken dialogue and arias. It emerged from the popular '' opéras comiques en vaudevilles'' of the Fair Theatres of St Germain and St Laurent (and to a l ...

''. In traditional number opera A number opera (; ) is an opera consisting of individual pieces of music ('numbers') which can be easily extracted from the larger work."Number opera" in ''New Grove''. They may be numbered consecutively in the score, and may be interspersed with r ...

, singers employ two styles of singing: recitative, a speech-inflected style, and self-contained aria

In music, an aria (Italian: ; plural: ''arie'' , or ''arias'' in common usage, diminutive form arietta , plural ariette, or in English simply air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrumental or orchestral accompanime ...

s. The 19th century saw the rise of the continuous music drama.

Opera originated in Italy at the end of the 16th century (with Jacopo Peri

Jacopo Peri (20 August 156112 August 1633), known under the pseudonym Il Zazzerino, was an Italian composer and singer of the transitional period between the Renaissance and Baroque styles, and is often called the inventor of opera. He wrote the ...

's mostly lost

Lost may refer to getting lost, or to:

Geography

*Lost, Aberdeenshire, a hamlet in Scotland

* Lake Okeechobee Scenic Trail, or LOST, a hiking and cycling trail in Florida, US

History

*Abbreviation of lost work, any work which is known to have bee ...

''Dafne

''Dafne'' is the earliest known work that, by modern standards, could be considered an opera. The libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini survives complete; the mostly lost music was completed by Jacopo Peri, but at least two of the six surviving fragment ...

'', produced in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

in 1598) especially from works by Claudio Monteverdi

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string player. A composer of both secular and sacred music, and a pioneer in the development of opera, he is considered ...

, notably '' L'Orfeo'', and soon spread through the rest of Europe: Heinrich Schütz in Germany, Jean-Baptiste Lully

Jean-Baptiste Lully ( , , ; born Giovanni Battista Lulli, ; – 22 March 1687) was an Italian-born French composer, guitarist, violinist, and dancer who is considered a master of the French Baroque music style. Best known for his operas, he ...

in France, and Henry Purcell

Henry Purcell (, rare: September 1659 – 21 November 1695) was an English composer.

Purcell's style of Baroque music was uniquely English, although it incorporated Italian and French elements. Generally considered among the greatest E ...

in England all helped to establish their national traditions in the 17th century. In the 18th century, Italian opera continued to dominate most of Europe (except France), attracting foreign composers such as George Frideric Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque music, Baroque composer well known for his opera#Baroque era, operas, oratorios, anthems, concerto grosso, concerti grossi, ...

. Opera seria

''Opera seria'' (; plural: ''opere serie''; usually called ''dramma per musica'' or ''melodramma serio'') is an Italian musical term which refers to the noble and "serious" style of Italian opera that predominated in Europe from the 1710s to abo ...

was the most prestigious form of Italian opera, until Christoph Willibald Gluck

Christoph Willibald (Ritter von) Gluck (; 2 July 1714 – 15 November 1787) was a composer of Italian and French opera in the early classical period. Born in the Upper Palatinate and raised in Bohemia, both part of the Holy Roman Empire, he g ...

reacted against its artificiality with his "reform" operas in the 1760s. The most renowned figure of late 18th-century opera is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

, who began with opera seria but is most famous for his Italian comic opera

Comic opera, sometimes known as light opera, is a sung dramatic work of a light or comic nature, usually with a happy ending and often including spoken dialogue.

Forms of comic opera first developed in late 17th-century Italy. By the 1730s, a ne ...

s, especially ''The Marriage of Figaro

''The Marriage of Figaro'' ( it, Le nozze di Figaro, links=no, ), K. 492, is a ''commedia per musica'' (opera buffa) in four acts composed in 1786 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, with an Italian libretto written by Lorenzo Da Ponte. It premie ...

'' (''Le nozze di Figaro''), ''Don Giovanni

''Don Giovanni'' (; K. 527; Vienna (1788) title: , literally ''The Rake Punished, or Don Giovanni'') is an opera in two acts with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an Italian libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte. Its subject is a centuries-old Spanis ...

'', and ''Così fan tutte

(''All Women Do It, or The School for Lovers''), K. 588, is an opera buffa in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. It was first performed on 26 January 1790 at the Burgtheater in Vienna, Austria. The libretto was written by Lorenzo Da Ponte w ...

'', as well as '' Die Entführung aus dem Serail'' (''The Abduction from the Seraglio''), and ''The Magic Flute

''The Magic Flute'' (German: , ), K. 620, is an opera in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to a German libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder. The work is in the form of a ''Singspiel'', a popular form during the time it was written that inclu ...

'' (''Die Zauberflöte''), landmarks in the German tradition.

The first third of the 19th century saw the high point of the bel canto

Bel canto (Italian for "beautiful singing" or "beautiful song", )—with several similar constructions (''bellezze del canto'', ''bell'arte del canto'')—is a term with several meanings that relate to Italian singing.

The phrase was not associat ...

style, with Gioachino Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards f ...

, Gaetano Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, he was a leading composer of the '' bel canto'' opera style dur ...

and Vincenzo Bellini

Vincenzo Salvatore Carmelo Francesco Bellini (; 3 November 1801 – 23 September 1835) was a Sicilian opera composer, who was known for his long-flowing melodic lines for which he was named "the Swan of Catania".

Many years later, in 1898, Giu ...

all creating signature works of that style. It also saw the advent of grand opera typified by the works of Daniel Auber and Giacomo Meyerbeer

Giacomo Meyerbeer (born Jakob Liebmann Beer; 5 September 1791 – 2 May 1864) was a German opera composer, "the most frequently performed opera composer during the nineteenth century, linking Mozart and Wagner". With his 1831 opera ''Robert le di ...

as well as Carl Maria von Weber's introduction of German Romantische Oper

''Romantische Oper'' () was a genre of early nineteenth-century German opera, developed not from the German Singspiel of the eighteenth-century but from the opéras comiques of the French Revolution. It offered opportunities for an increasingly i ...

(German Romantic Opera). The mid-to-late 19th century was a golden age of opera, led and dominated by Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the h ...

in Italy and Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

in Germany. The popularity of opera continued through the verismo

In opera, ''verismo'' (, from , meaning "true") was a post-Romantic operatic tradition associated with Italian composers such as Pietro Mascagni, Ruggero Leoncavallo, Umberto Giordano, Francesco Cilea and Giacomo Puccini.

''Verismo'' as an ...

era in Italy and contemporary French opera

French opera is one of Europe's most important operatic traditions, containing works by composers of the stature of Rameau, Berlioz, Gounod, Bizet, Massenet, Debussy, Ravel, Poulenc and Messiaen. Many foreign-born composers have played a part i ...

through to Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini (Lucca, 22 December 1858Bruxelles, 29 November 1924) was an Italian composer known primarily for his operas. Regarded as the greatest and most successful proponent of Italian opera after Verdi, he was descended from a long li ...

and Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wag ...

in the early 20th century. During the 19th century, parallel operatic traditions emerged in central and eastern Europe, particularly in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

and Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

. The 20th century saw many experiments with modern styles, such as atonality

Atonality in its broadest sense is music that lacks a tonal center, or key. ''Atonality'', in this sense, usually describes compositions written from about the early 20th-century to the present day, where a hierarchy of harmonies focusing on a s ...

and serialism

In music, serialism is a method of Musical composition, composition using series of pitches, rhythms, dynamics, timbres or other elements of music, musical elements. Serialism began primarily with Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, thou ...

(Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

and Alban Berg

Alban Maria Johannes Berg ( , ; 9 February 1885 – 24 December 1935) was an Austrian composer of the Second Viennese School. His compositional style combined Romantic lyricism with the twelve-tone technique. Although he left a relatively sma ...

), neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism was ...

(Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

), and minimalism

In visual arts, music and other media, minimalism is an art movement that began in post–World War II in Western art, most strongly with American visual arts in the 1960s and early 1970s. Prominent artists associated with minimalism include Don ...

(Philip Glass

Philip Glass (born January 31, 1937) is an American composer and pianist. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential composers of the late 20th century. Glass's work has been associated with minimal music, minimalism, being built up fr ...

and John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

). With the rise of recording technology

Sound recording and reproduction is the electrical, mechanical, electronic, or digital inscription and re-creation of sound waves, such as spoken voice, singing, instrumental music, or sound effects. The two main classes of sound recording te ...

, singers such as Enrico Caruso

Enrico Caruso (, , ; 25 February 1873 – 2 August 1921) was an Italian operatic first lyrical tenor then dramatic tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and the Americas, appearing in a wide variety of roles (74) ...

and Maria Callas

Maria Callas . (born Sophie Cecilia Kalos; December 2, 1923 – September 16, 1977) was an American-born Greek soprano who was one of the most renowned and influential opera singers of the 20th century. Many critics praised her ''bel cant ...

became known to much wider audiences that went beyond the circle of opera fans. Since the invention of radio and television, operas were also performed on (and written for) these media. Beginning in 2006, a number of major opera houses began to present live high-definition video

High-definition video (HD video) is video of higher resolution and quality than standard-definition. While there is no standardized meaning for ''high-definition'', generally any video image with considerably more than 480 vertical scan lines (No ...

transmissions of their performances in cinemas

A movie theater (American English), cinema (British English), or cinema hall (Indian English), also known as a movie house, picture house, the movies, the pictures, picture theater, the silver screen, the big screen, or simply theater is a ...

all over the world. Since 2009, complete performances can be downloaded and are live streamed

Livestreaming is streaming media simultaneously recorded and broadcast in real-time over the internet. It is often referred to simply as streaming. Non-live media such as video-on-demand, vlogs, and YouTube videos are technically streamed, but ...

.

Operatic terminology

The words of an opera are known as thelibretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the t ...

(meaning "small book"). Some composers, notably Wagner, have written their own libretti; others have worked in close collaboration with their librettists, e.g. Mozart with Lorenzo Da Ponte. Traditional opera, often referred to as "number opera A number opera (; ) is an opera consisting of individual pieces of music ('numbers') which can be easily extracted from the larger work."Number opera" in ''New Grove''. They may be numbered consecutively in the score, and may be interspersed with r ...

", consists of two modes of singing: recitative, the plot-driving passages sung in a style designed to imitate and emphasize the inflections of speech, and aria

In music, an aria (Italian: ; plural: ''arie'' , or ''arias'' in common usage, diminutive form arietta , plural ariette, or in English simply air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrumental or orchestral accompanime ...

(an "air" or formal song) in which the characters express their emotions in a more structured melodic style. Vocal duets, trios and other ensembles often occur, and choruses are used to comment on the action. In some forms of opera, such as singspiel

A Singspiel (; plural: ; ) is a form of German-language music drama, now regarded as a genre of opera. It is characterized by spoken dialogue, which is alternated with ensembles, songs, ballads, and arias which were often strophic, or folk-like ...

, opéra comique

''Opéra comique'' (; plural: ''opéras comiques'') is a genre of French opera that contains spoken dialogue and arias. It emerged from the popular '' opéras comiques en vaudevilles'' of the Fair Theatres of St Germain and St Laurent (and to a l ...

, operetta

Operetta is a form of theatre and a genre of light opera. It includes spoken dialogue, songs, and dances. It is lighter than opera in terms of its music, orchestral size, length of the work, and at face value, subject matter. Apart from its s ...

, and semi-opera, the recitative is mostly replaced by spoken dialogue. Melodic or semi-melodic passages occurring in the midst of, or instead of, recitative, are also referred to as arioso. The terminology of the various kinds of operatic voices is described in detail below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

*Bottom (disambiguation)

Bottom may refer to:

Anatomy and sex

* Bottom (BDSM), the partner in a BDSM who takes the passive, receiving, or obedient role, to that of the top or ...

. During both the Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including t ...

and Classical periods, recitative could appear in two basic forms, each of which was accompanied by a different instrumental ensemble: ''secco'' (dry) recitative, sung with a free rhythm dictated by the accent of the words, accompanied only by ''basso continuo

Basso continuo parts, almost universal in the Baroque era (1600–1750), provided the harmonic structure of the music by supplying a bassline and a chord progression. The phrase is often shortened to continuo, and the instrumentalists playing th ...

'', which was usually a harpsichord

A harpsichord ( it, clavicembalo; french: clavecin; german: Cembalo; es, clavecín; pt, cravo; nl, klavecimbel; pl, klawesyn) is a musical instrument played by means of a keyboard. This activates a row of levers that turn a trigger mechanism ...

and a cello; or ''accompagnato'' (also known as ''strumentato'') in which the orchestra provided accompaniment. Over the 18th century, arias were increasingly accompanied by the orchestra. By the 19th century, ''accompagnato'' had gained the upper hand, the orchestra played a much bigger role, and Wagner revolutionized opera by abolishing almost all distinction between aria and recitative in his quest for what Wagner termed "endless melody". Subsequent composers have tended to follow Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

's example, though some, such as Stravinsky in his '' The Rake's Progress'' have bucked the trend. The changing role of the orchestra in opera is described in more detail below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

*Bottom (disambiguation)

Bottom may refer to:

Anatomy and sex

* Bottom (BDSM), the partner in a BDSM who takes the passive, receiving, or obedient role, to that of the top or ...

.

History

Origins

The Italian word ''opera'' means "work", both in the sense of the labour done and the result produced. The Italian word derives from the Latin word ''

The Italian word ''opera'' means "work", both in the sense of the labour done and the result produced. The Italian word derives from the Latin word ''opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a librett ...

'', a singular noun meaning "work" and also the plural of the noun '' opus''. According to the Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

, the Italian word was first used in the sense "composition in which poetry, dance, and music are combined" in 1639; the first recorded English usage in this sense dates to 1648.

''Dafne

''Dafne'' is the earliest known work that, by modern standards, could be considered an opera. The libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini survives complete; the mostly lost music was completed by Jacopo Peri, but at least two of the six surviving fragment ...

'' by Jacopo Peri

Jacopo Peri (20 August 156112 August 1633), known under the pseudonym Il Zazzerino, was an Italian composer and singer of the transitional period between the Renaissance and Baroque styles, and is often called the inventor of opera. He wrote the ...

was the earliest composition considered opera, as understood today. It was written around 1597, largely under the inspiration of an elite circle of literate Florentine humanists

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanis ...

who gathered as the " Camerata de' Bardi". Significantly, ''Dafne'' was an attempt to revive the classical Greek drama, part of the wider revival of antiquity characteristic of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

. The members of the Camerata considered that the "chorus" parts of Greek dramas were originally sung, and possibly even the entire text of all roles; opera was thus conceived as a way of "restoring" this situation. ''Dafne,'' however, is lost. A later work by Peri, ''Euridice

Eurydice (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρυδίκη 'wide justice') was a character in Greek mythology and the Auloniad wife of Orpheus, who tried to bring her back from the dead with his enchanting music.

Etymology

Several meanings for the name ...

'', dating from 1600, is the first opera score to have survived until the present day. However, the honour of being the first opera still to be regularly performed goes to Claudio Monteverdi

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string player. A composer of both secular and sacred music, and a pioneer in the development of opera, he is considered ...

's '' L'Orfeo'', composed for the court of Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard language, Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and ''comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture ...

in 1607. The Mantua court of the Gonzagas, employers of Monteverdi, played a significant role in the origin of opera employing not only court singers of the concerto delle donne (till 1598), but also one of the first actual "opera singers", Madama Europa

Madama Europa was the nickname of Europa Rossi (fl. 1600), an opera singer, the first Jewish opera singer to achieve widespread fame outside of the Jewish community.

She was the sister of the Jewish violinist and composer Salamone Rossi who is k ...

.

Italian opera

Baroque era

Opera did not remain confined to court audiences for long. In 1637, the idea of a "season" (often during the

Opera did not remain confined to court audiences for long. In 1637, the idea of a "season" (often during the carnival

Carnival is a Catholic Christian festive season that occurs before the liturgical season of Lent. The main events typically occur during February or early March, during the period historically known as Shrovetide (or Pre-Lent). Carnival typi ...

) of publicly attended operas supported by ticket sales emerged in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

. Monteverdi had moved to the city from Mantua and composed his last operas, ''Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria

''Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria'' (Stattkus-Verzeichnis, SV 325, ''The Return of Ulysses to his Homeland'') is an List of operas by Claudio Monteverdi, opera consisting of a prologue and five acts (later revised to three), set by Claudio Montever ...

'' and '' L'incoronazione di Poppea'', for the Venetian theatre in the 1640s. His most important follower Francesco Cavalli

Francesco Cavalli (born Pietro Francesco Caletti-Bruni; 14 February 1602 – 14 January 1676) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian composer, organist and singer of the early Baroque music, Baroque period. He succeeded his teacher Claudio Monteverd ...

helped spread opera throughout Italy. In these early Baroque operas, broad comedy was blended with tragic elements in a mix that jarred some educated sensibilities, sparking the first of opera's many reform movements, sponsored by the Arcadian Academy

The Accademia degli Arcadi or Accademia dell'Arcadia, "Academy of Arcadia" or "Academy of the Arcadians", was an Italian literary academy founded in Rome in 1690. The full Italian official name was Pontificia Accademia degli Arcadi.

History

F ...

, which came to be associated with the poet Metastasio, whose libretti

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the text of major litu ...

helped crystallize the genre of opera seria

''Opera seria'' (; plural: ''opere serie''; usually called ''dramma per musica'' or ''melodramma serio'') is an Italian musical term which refers to the noble and "serious" style of Italian opera that predominated in Europe from the 1710s to abo ...

, which became the leading form of Italian opera until the end of the 18th century. Once the Metastasian ideal had been firmly established, comedy in Baroque-era opera was reserved for what came to be called opera buffa

''Opera buffa'' (; "comic opera", plural: ''opere buffe'') is a genre of opera. It was first used as an informal description of Italian comic operas variously classified by their authors as ''commedia in musica'', ''commedia per musica'', ''dramm ...

. Before such elements were forced out of opera seria, many libretti had featured a separately unfolding comic plot as sort of an "opera-within-an-opera". One reason for this was an attempt to attract members of the growing merchant class, newly wealthy, but still not as cultured as the nobility, to the public opera house

An opera house is a theatre building used for performances of opera. It usually includes a stage, an orchestra pit, audience seating, and backstage facilities for costumes and building sets.

While some venues are constructed specifically for o ...

s. These separate plots were almost immediately resurrected in a separately developing tradition that partly derived from the commedia dell'arte

(; ; ) was an early form of professional theatre, originating from Italian theatre, that was popular throughout Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries. It was formerly called Italian comedy in English and is also known as , , and . Charact ...

, a long-flourishing improvisatory stage tradition of Italy. Just as intermedi had once been performed in between the acts of stage plays, operas in the new comic genre of ''intermezzi'', which developed largely in Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

in the 1710s and 1720s, were initially staged during the intermissions of opera seria. They became so popular, however, that they were soon being offered as separate productions.

Opera seria was elevated in tone and highly stylised in form, usually consisting of ''secco'' recitative interspersed with long ''da capo'' arias. These afforded great opportunity for virtuosic singing and during the golden age of ''opera seria'' the singer really became the star. The role of the hero was usually written for the high-pitched male castrato

A castrato (Italian, plural: ''castrati'') is a type of classical male singing voice equivalent to that of a soprano, mezzo-soprano, or contralto. The voice is produced by castration of the singer before puberty, or it occurs in one who, due to ...

voice, which was produced by castration

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which an individual loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical castration uses pharmaceut ...

of the singer before puberty

Puberty is the process of physical changes through which a child's body matures into an adult body capable of sexual reproduction. It is initiated by hormonal signals from the brain to the gonads: the ovaries in a girl, the testes in a boy. ...

, which prevented a boy's larynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal inlet is about ...

from being transformed at puberty. Castrati such as Farinelli

Farinelli (; 24 January 1705 – 16 September 1782) was the stage name of Carlo Maria Michelangelo Nicola Broschi (), a celebrated Italian castrato singer of the 18th century and one of the greatest singers in the history of opera. Farinelli h ...

and Senesino

Francesco Bernardi (; 31 October 1686 – 27 November 1758), known as Senesino ( or traditionally ), was a celebrated Italian contralto castrato, particularly remembered today for his long collaboration with the composer George Frideric Handel ...

, as well as female soprano

A soprano () is a type of classical female singing voice and has the highest vocal range of all voice types. The soprano's vocal range (using scientific pitch notation) is from approximately middle C (C4) = 261 Hz to "high A" (A5) = 880&n ...

s such as Faustina Bordoni

Faustina Bordoni (30 March 1697 – 4 November 1781) was an Italian mezzo-soprano.

In Hamburg, Germany, the Johann Adolph Hasse Museum is dedicated to her husband and partly to Bordoni.

Early career

She was born in Venice and brought up unde ...

, became in great demand throughout Europe as ''opera seria'' ruled the stage in every country except France. Farinelli was one of the most famous singers of the 18th century. Italian opera set the Baroque standard. Italian libretti were the norm, even when a German composer like Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concertos. Handel received his training i ...

found himself composing the likes of ''Rinaldo

Rinaldo may refer to:

*Renaud de Montauban (also spelled Renaut, Renault, Italian: Rinaldo di Montalbano, Dutch: Reinout van Montalbaen, German: Reinhold von Montalban), a legendary knight in the medieval Matter of France

* Rinaldo (''Jerusalem Lib ...

'' and '' Giulio Cesare'' for London audiences. Italian libretti

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the text of major litu ...

remained dominant in the classical period as well, for example in the operas of Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

, who wrote in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

near the century's close. Leading Italian-born composers of opera seria include Alessandro Scarlatti

Pietro Alessandro Gaspare Scarlatti (2 May 1660 – 22 October 1725) was an Italian Baroque composer, known especially for his operas and chamber cantatas. He is considered the most important representative of the Neapolitan school of opera.

...

, Antonio Vivaldi

Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741) was an Italian composer, virtuoso violinist and impresario of Baroque music. Regarded as one of the greatest Baroque composers, Vivaldi's influence during his lifetime was widespread a ...

and Nicola Porpora

Nicola (or Niccolò) Antonio Porpora (17 August 16863 March 1768) was an Italian composer and teacher of singing of the Baroque era, whose most famous singing students were the castrati Farinelli and Caffarelli. Other students included compose ...

.

Gluck's reforms and Mozart

Opera seria had its weaknesses and critics. The taste for embellishment on behalf of the superbly trained singers, and the use of spectacle as a replacement for dramatic purity and unity drew attacks.

Opera seria had its weaknesses and critics. The taste for embellishment on behalf of the superbly trained singers, and the use of spectacle as a replacement for dramatic purity and unity drew attacks. Francesco Algarotti

Count Francesco Algarotti (11 December 1712 – 3 May 1764) was an Italian polymath, philosopher, poet, essayist, anglophile, art critic and art collector. He was a man of broad knowledge, an expert in Newtonianism, architecture and opera. He wa ...

's ''Essay on the Opera'' (1755) proved to be an inspiration for Christoph Willibald Gluck

Christoph Willibald (Ritter von) Gluck (; 2 July 1714 – 15 November 1787) was a composer of Italian and French opera in the early classical period. Born in the Upper Palatinate and raised in Bohemia, both part of the Holy Roman Empire, he g ...

's reforms. He advocated that ''opera seria'' had to return to basics and that all the various elements—music (both instrumental and vocal), ballet

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form of ...

, and staging—must be subservient to the overriding drama. In 1765 Melchior Grimm published "", an influential article for the Encyclopédie on lyric and opera libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the t ...

s. Several composers of the period, including Niccolò Jommelli

Niccolò Jommelli (; 10 September 1714 – 25 August 1774) was an Italian composer of the Neapolitan School. Along with other composers mainly in the Holy Roman Empire and France, he was responsible for certain operatic reforms including redu ...

and Tommaso Traetta, attempted to put these ideals into practice. The first to succeed however, was Gluck. Gluck

Christoph Willibald (Ritter von) Gluck (; 2 July 1714 – 15 November 1787) was a composer of Italian and French opera in the early classical period (music), classical period. Born in the Upper Palatinate and raised in Bohemia, both part of the ...

strove to achieve a "beautiful simplicity". This is evident in his first reform opera, ''Orfeo ed Euridice

' (; French: '; English: ''Orpheus and Eurydice'') is an opera composed by Christoph Willibald Gluck, based on Orpheus, the myth of Orpheus and set to a libretto by Ranieri de' Calzabigi. It belongs to the genre of the ''azione teatrale'', mea ...

'', where his non-virtuosic vocal melodies are supported by simple harmonies and a richer orchestra presence throughout.

Gluck's reforms have had resonance throughout operatic history. Weber, Mozart, and Wagner, in particular, were influenced by his ideals. Mozart, in many ways Gluck's successor, combined a superb sense of drama, harmony, melody, and counterpoint to write a series of comic operas with libretti by Lorenzo Da Ponte, notably '' Le nozze di Figaro'', ''Don Giovanni

''Don Giovanni'' (; K. 527; Vienna (1788) title: , literally ''The Rake Punished, or Don Giovanni'') is an opera in two acts with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an Italian libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte. Its subject is a centuries-old Spanis ...

'', and ''Così fan tutte

(''All Women Do It, or The School for Lovers''), K. 588, is an opera buffa in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. It was first performed on 26 January 1790 at the Burgtheater in Vienna, Austria. The libretto was written by Lorenzo Da Ponte w ...

'', which remain among the most-loved, popular and well-known operas. But Mozart's contribution to ''opera seria'' was more mixed; by his time it was dying away, and in spite of such fine works as '' Idomeneo'' and '' La clemenza di Tito'', he would not succeed in bringing the art form back to life again.

Bel canto, Verdi and verismo

The

The bel canto

Bel canto (Italian for "beautiful singing" or "beautiful song", )—with several similar constructions (''bellezze del canto'', ''bell'arte del canto'')—is a term with several meanings that relate to Italian singing.

The phrase was not associat ...

opera movement flourished in the early 19th century and is exemplified by the operas of Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards f ...

, Bellini, Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, he was a leading composer of the '' bel canto'' opera style dur ...

, Pacini, Mercadante and many others. Literally "beautiful singing", ''bel canto'' opera derives from the Italian stylistic singing school of the same name. Bel canto lines are typically florid and intricate, requiring supreme agility and pitch control. Examples of famous operas in the bel canto style include Rossini's '' Il barbiere di Siviglia'' and '' La Cenerentola'', as well as Bellini's '' Norma'', '' La sonnambula'' and '' I puritani'' and Donizetti's '' Lucia di Lammermoor'', ''L'elisir d'amore

''L'elisir d'amore'' (''The Elixir of Love'', ) is a ' (opera buffa) in two acts by the Italian composer Gaetano Donizetti. Felice Romani wrote the Italian libretto, after Eugène Scribe's libretto for Daniel Auber's ' (1831). The opera premiere ...

'' and '' Don Pasquale''.

Following the bel canto era, a more direct, forceful style was rapidly popularized by Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the h ...

, beginning with his biblical opera ''Nabucco

''Nabucco'' (, short for Nabucodonosor ; en, " Nebuchadnezzar") is an Italian-language opera in four acts composed in 1841 by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Temistocle Solera. The libretto is based on the biblical books of 2 Kings, ...

''. This opera, and the ones that would follow in Verdi's career, revolutionized Italian opera, changing it from merely a display of vocal fireworks, with Rossini's and Donizetti's works, to dramatic story-telling. Verdi's operas resonated with the growing spirit of Italian nationalism in the post-Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

ic era, and he quickly became an icon of the patriotic movement for a unified Italy. In the early 1850s, Verdi produced his three most popular operas: '' Rigoletto'', '' Il trovatore'' and ''La traviata

''La traviata'' (; ''The Fallen Woman'') is an opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi set to an Italian libretto by Francesco Maria Piave. It is based on ''La Dame aux camélias'' (1852), a play by Alexandre Dumas ''fils'' adapted from his own 18 ...

''. The first of these, ''Rigoletto'', proved the most daring and revolutionary. In it, Verdi blurs the distinction between the aria and recitative as it never before was, leading the opera to be "an unending string of duets". ''La traviata'' was also novel. It tells the story of courtesan, and is often cited as one of the first "realistic" operas, because rather than featuring great kings and figures from literature, it focuses on the tragedies of ordinary life and society. After these, he continued to develop his style, composing perhaps the greatest French grand opera, ''Don Carlos

''Don Carlos'' is a five-act grand opera composed by Giuseppe Verdi to a French-language libretto by Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle, based on the dramatic play '' Don Carlos, Infant von Spanien'' (''Don Carlos, Infante of Spain'') by Friedri ...

'', and ending his career with two Shakespeare-inspired works, ''Otello

''Otello'' () is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on Shakespeare's play ''Othello''. It was Verdi's penultimate opera, first performed at the Teatro alla Scala, Milan, on 5 February 1887.

Th ...

'' and ''Falstaff

Sir John Falstaff is a fictional character who appears in three plays by William Shakespeare and is eulogised in a fourth. His significance as a fully developed character is primarily formed in the plays '' Henry IV, Part 1'' and '' Part 2'', w ...

'', which reveal how far Italian opera had grown in sophistication since the early 19th century. These final two works showed Verdi at his most masterfully orchestrated, and are both incredibly influential, and modern. In ''Falstaff'', Verdi sets the preeminent standard for the form and style that would dominate opera throughout the twentieth century. Rather than long, suspended melodies, ''Falstaff'' contains many little motifs and mottos, that, rather than being expanded upon, are introduced and subsequently dropped, only to be brought up again later. These motifs never are expanded upon, and just as the audience expects a character to launch into a long melody, a new character speaks, introducing a new phrase. This fashion of opera directed opera from Verdi, onward, exercising tremendous influence on his successors Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini (Lucca, 22 December 1858Bruxelles, 29 November 1924) was an Italian composer known primarily for his operas. Regarded as the greatest and most successful proponent of Italian opera after Verdi, he was descended from a long li ...

, Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wag ...

, and Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

.

After Verdi, the sentimental "realistic" melodrama of verismo

In opera, ''verismo'' (, from , meaning "true") was a post-Romantic operatic tradition associated with Italian composers such as Pietro Mascagni, Ruggero Leoncavallo, Umberto Giordano, Francesco Cilea and Giacomo Puccini.

''Verismo'' as an ...

appeared in Italy. This was a style introduced by Pietro Mascagni's '' Cavalleria rusticana'' and Ruggero Leoncavallo

Ruggero (or Ruggiero) Leoncavallo ( , , ; 23 April 18579 August 1919) was an Italian opera composer and librettist. Although he produced numerous operas and other songs throughout his career it is his opera '' Pagliacci'' (1892) that remained hi ...

's ''Pagliacci

''Pagliacci'' (; literal translation, "Clowns") is an Italian opera in a prologue and two acts, with music and libretto by Ruggero Leoncavallo. The opera tells the tale of Canio, actor and leader of a commedia dell'arte theatrical company, who m ...

'' that came to dominate the world's opera stages with such popular works as Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini (Lucca, 22 December 1858Bruxelles, 29 November 1924) was an Italian composer known primarily for his operas. Regarded as the greatest and most successful proponent of Italian opera after Verdi, he was descended from a long li ...

's '' La bohème'', ''Tosca

''Tosca'' is an opera in three acts by Giacomo Puccini to an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. It premiered at the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma, Teatro Costanzi in Rome on 14 January 1900. The work, based on Victorien Sardou's 1 ...

'', and ''Madama Butterfly

''Madama Butterfly'' (; ''Madame Butterfly'') is an opera in three acts (originally two) by Giacomo Puccini, with an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa.

It is based on the short story "Madame Butterfly" (1898) by John Luther ...

''. Later Italian composers, such as Berio and Nono

Nono may refer to:

Places

* Nono, Argentina, a municipality in the Province of Córdoba

* Nono, Ecuador, a parish in the municipality of Quito in the province of Pichincha

* Nono, Illubabor, Oromia (woreda), Ethiopia, or Nono Sele

** Nono, I ...

, have experimented with modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

.

German-language opera

The first German opera was ''Dafne

''Dafne'' is the earliest known work that, by modern standards, could be considered an opera. The libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini survives complete; the mostly lost music was completed by Jacopo Peri, but at least two of the six surviving fragment ...

'', composed by Heinrich Schütz in 1627, but the music score has not survived. Italian opera held a great sway over German-speaking countries until the late 18th century. Nevertheless, native forms would develop in spite of this influence. In 1644, Sigmund Staden produced the first ''Singspiel

A Singspiel (; plural: ; ) is a form of German-language music drama, now regarded as a genre of opera. It is characterized by spoken dialogue, which is alternated with ensembles, songs, ballads, and arias which were often strophic, or folk-like ...

'', ''Seelewig

''Seelewig'' or ''Das geistliche Waldgedicht oder Freudenspiel genant Seelewig'' (''The Sacred Forest Poem or Play of Rejoicing called Seelewig'') is an opera in a prologue, three acts and an epilogue by the German composer Sigmund Theophil Staden ...

'', a popular form of German-language opera in which singing alternates with spoken dialogue. In the late 17th century and early 18th century, the Theater am Gänsemarkt in Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

presented German operas by Keiser, Telemann and Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concertos. Handel received his training i ...

. Yet most of the major German composers of the time, including Handel himself, as well as Graun, Hasse Hasse is both a surname and a given name. Notable people with the name include:

Surname:

* Clara H. Hasse (1880–1926), American botanist

* Helmut Hasse (1898–1979), German mathematician

* Henry Hasse (1913–1977), US writer of science fiction

...

and later Gluck

Christoph Willibald (Ritter von) Gluck (; 2 July 1714 – 15 November 1787) was a composer of Italian and French opera in the early classical period (music), classical period. Born in the Upper Palatinate and raised in Bohemia, both part of the ...

, chose to write most of their operas in foreign languages, especially Italian. In contrast to Italian opera, which was generally composed for the aristocratic class, German opera was generally composed for the masses and tended to feature simple folk-like melodies, and it was not until the arrival of Mozart that German opera was able to match its Italian counterpart in musical sophistication. The theatre company of Abel Seyler

Abel Seyler (23 August 1730, Liestal – 25 April 1800, Rellingen) was a Swiss-born theatre director and former merchant banker, who was regarded as one of the great theatre principals of 18th century Europe. He played a pivotal role in the deve ...

pioneered serious German-language opera in the 1770s, marking a break with the previous simpler musical entertainment.

Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

's ''Singspiele'', '' Die Entführung aus dem Serail'' (1782) and '' Die Zauberflöte'' (1791) were an important breakthrough in achieving international recognition for German opera. The tradition was developed in the 19th century by Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

with his ''Fidelio

''Fidelio'' (; ), originally titled ' (''Leonore, or The Triumph of Marital Love''), Op. 72, is Ludwig van Beethoven's only opera. The German libretto was originally prepared by Joseph Sonnleithner from the French of Jean-Nicolas Bouilly, with ...

'' (1805), inspired by the climate of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

. Carl Maria von Weber established German Romantic opera in opposition to the dominance of Italian bel canto

Bel canto (Italian for "beautiful singing" or "beautiful song", )—with several similar constructions (''bellezze del canto'', ''bell'arte del canto'')—is a term with several meanings that relate to Italian singing.

The phrase was not associat ...

. His ''Der Freischütz

' ( J. 277, Op. 77 ''The Marksman'' or ''The Freeshooter'') is a German opera with spoken dialogue in three acts by Carl Maria von Weber with a libretto by Friedrich Kind, based on a story by Johann August Apel and Friedrich Laun from their 181 ...

'' (1821) shows his genius for creating a supernatural atmosphere. Other opera composers of the time include Marschner

Heinrich August Marschner (16 August 1795 – 14 December 1861) was the most important composer of German opera between Carl Maria von Weber, Weber and Richard Wagner, Wagner.Schubert and  Wagner was one of the most revolutionary and controversial composers in musical history. Starting under the influence of

Wagner was one of the most revolutionary and controversial composers in musical history. Starting under the influence of

In rivalry with imported Italian opera productions, a separate French tradition was founded by the Italian-born French composer

In rivalry with imported Italian opera productions, a separate French tradition was founded by the Italian-born French composer  By the 1820s, Gluckian influence in France had given way to a taste for Italian

By the 1820s, Gluckian influence in France had given way to a taste for Italian

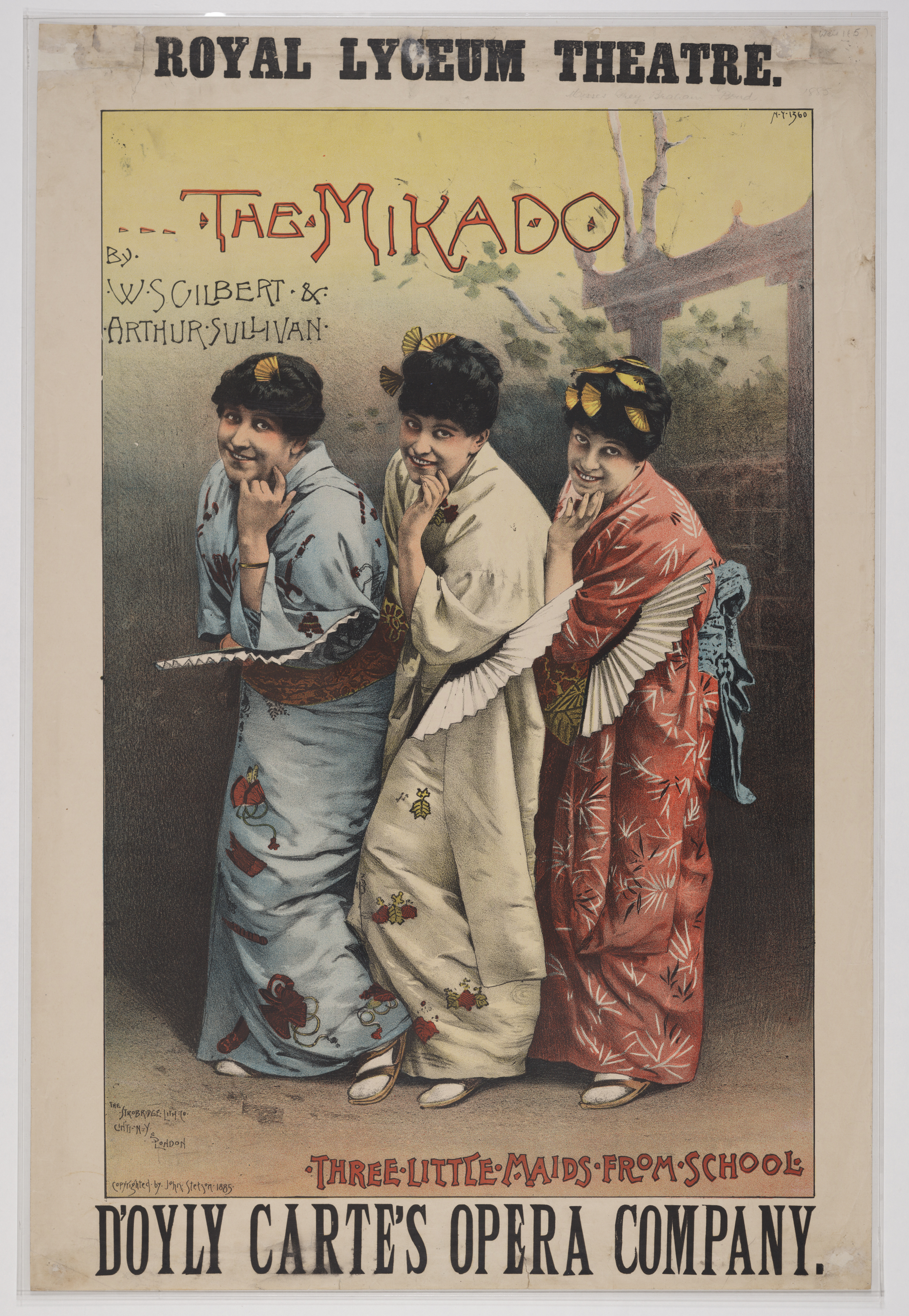

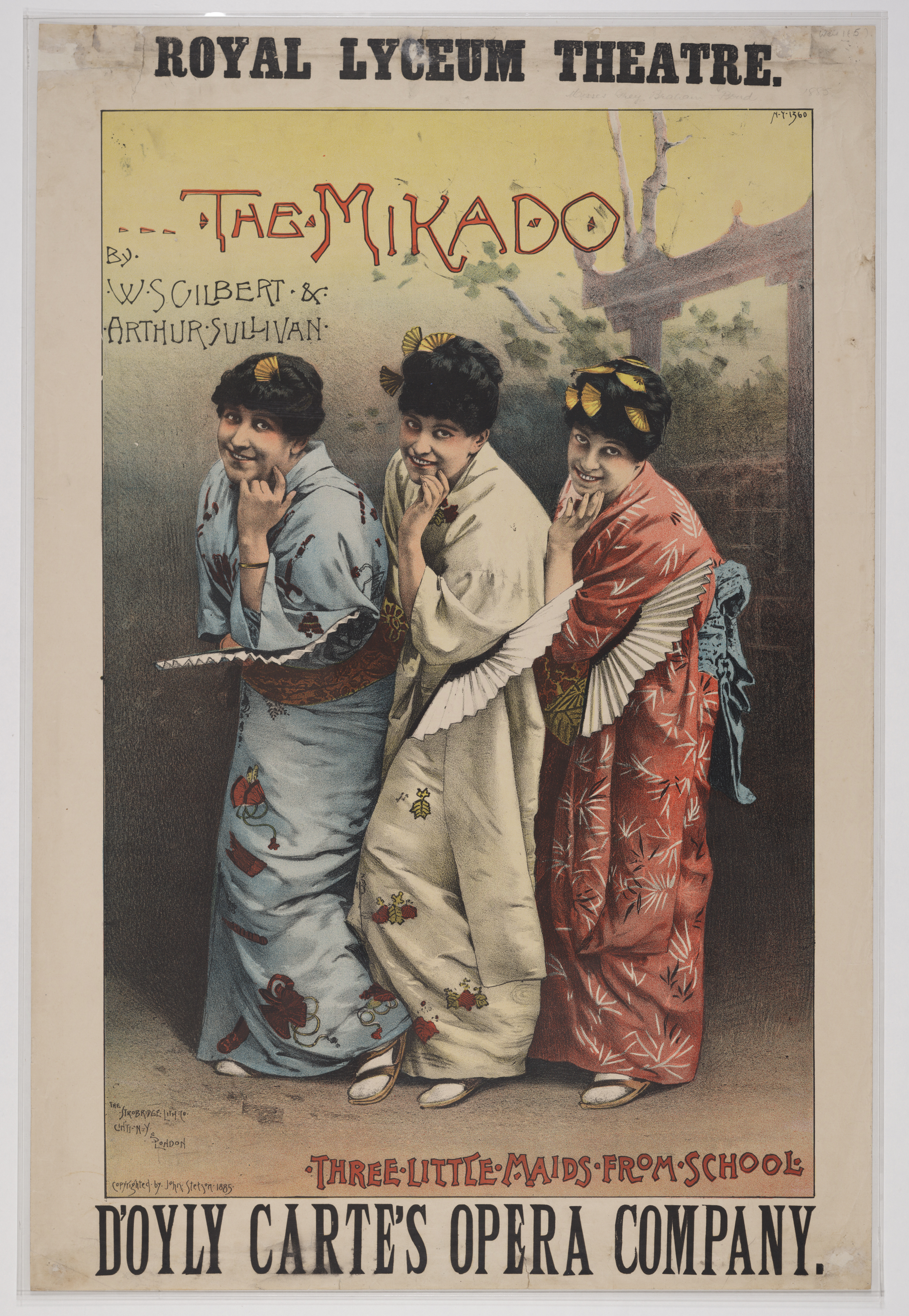

In England, opera's antecedent was the 17th-century ''jig''. This was an afterpiece that came at the end of a play. It was frequently

In England, opera's antecedent was the 17th-century ''jig''. This was an afterpiece that came at the end of a play. It was frequently

'' Following Purcell, the popularity of opera in England dwindled for several decades. A revived interest in opera occurred in the 1730s which is largely attributed to

Following Purcell, the popularity of opera in England dwindled for several decades. A revived interest in opera occurred in the 1730s which is largely attributed to  Besides Arne, the other dominating force in English opera at this time was

Besides Arne, the other dominating force in English opera at this time was

Opera was brought to Russia in the 1730s by the

Opera was brought to Russia in the 1730s by the

Antonín Dvořák's nine operas, except his first, have librettos in Czech and were intended to convey the Czech national spirit, as were some of his choral works. By far the most successful of the operas is ''

Antonín Dvořák's nine operas, except his first, have librettos in Czech and were intended to convey the Czech national spirit, as were some of his choral works. By far the most successful of the operas is ''

The key figure of Hungarian national opera in the 19th century was Ferenc Erkel, whose works mostly dealt with historical themes. Among his most often performed operas are ''

The key figure of Hungarian national opera in the 19th century was Ferenc Erkel, whose works mostly dealt with historical themes. Among his most often performed operas are '' The first years of the

The first years of the

Operatic modernism truly began in the operas of two Viennese composers,

Operatic modernism truly began in the operas of two Viennese composers,  Composers thus influenced include the Englishman

Composers thus influenced include the Englishman

Early performances of opera were too infrequent for singers to make a living exclusively from the style, but with the birth of commercial opera in the mid-17th century, professional performers began to emerge. The role of the male hero was usually entrusted to a

Early performances of opera were too infrequent for singers to make a living exclusively from the style, but with the birth of commercial opera in the mid-17th century, professional performers began to emerge. The role of the male hero was usually entrusted to a

The orchestra has also provided an instrumental

The orchestra has also provided an instrumental

Outside the US, and especially in Europe, most opera houses receive public subsidies from taxpayers. In Milan, Italy, 60% of La Scala's annual budget of €115 million is from ticket sales and private donations, with the remaining 40% coming from public funds. In 2005, La Scala received 25% of Italy's total state subsidy of €464 million for the performing arts. In the UK,

Outside the US, and especially in Europe, most opera houses receive public subsidies from taxpayers. In Milan, Italy, 60% of La Scala's annual budget of €115 million is from ticket sales and private donations, with the remaining 40% coming from public funds. In 2005, La Scala received 25% of Italy's total state subsidy of €464 million for the performing arts. In the UK,

A milestone for opera broadcasting in the U.S. was achieved on 24 December 1951, with the live broadcast of ''

A milestone for opera broadcasting in the U.S. was achieved on 24 December 1951, with the live broadcast of ''

''

"Supporting Collaboration in Changing Cultural Landscapes"

pp. 208–209 in Margaret S Barrett (ed.) ''Collaborative Creative Thought and Practice in Music''. Ashgate Publishing.

partial preview

View

at

"Opera"

Herbert Weinstock and

Comprehensive opera performances database

Operabase

Opera-Inside

opera and aria guides, biographies, history

StageAgent – synopses and character descriptions for most major operas

Vocabulaire de l'Opéra

HistoricOpera – historic operatic images

"America's Opera Boom"

By Jonathan Leaf, '' The American'', July/August 2007 Issue

Opera~Opera article archives

* {{Authority control Musical forms Italian inventions Drama Theatre Vocal music Singing

Lortzing

Gustav Albert Lortzing (23 October 1801 – 21 January 1851) was a German composer, librettist, actor and singer. He is considered to be the main representative of the German ''Spieloper'', a form similar to the French ''opéra comique'', which ...

, but the most significant figure was undoubtedly Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

.

Wagner was one of the most revolutionary and controversial composers in musical history. Starting under the influence of

Wagner was one of the most revolutionary and controversial composers in musical history. Starting under the influence of Weber

Weber (, or ; German: ) is a surname of German origin, derived from the noun meaning " weaver". In some cases, following migration to English-speaking countries, it has been anglicised to the English surname 'Webber' or even 'Weaver'.

Notable pe ...

and Meyerbeer, he gradually evolved a new concept of opera as a '' Gesamtkunstwerk'' (a "complete work of art"), a fusion of music, poetry and painting. He greatly increased the role and power of the orchestra, creating scores with a complex web of leitmotif

A leitmotif or leitmotiv () is a "short, recurring musical phrase" associated with a particular person, place, or idea. It is closely related to the musical concepts of ''idée fixe'' or ''motto-theme''. The spelling ''leitmotif'' is an anglici ...

s, recurring themes often associated with the characters and concepts of the drama, of which prototypes can be heard in his earlier operas such as '' Der fliegende Holländer'', ''Tannhäuser

Tannhäuser (; gmh, Tanhûser), often stylized, "The Tannhäuser," was a German Minnesinger and traveling poet. Historically, his biography, including the dates he lived, is obscure beyond the poetry, which suggests he lived between 1245 and 1 ...

'' and '' Lohengrin''; and he was prepared to violate accepted musical conventions, such as tonality

Tonality is the arrangement of pitches and/or chords of a musical work in a hierarchy of perceived relations, stabilities, attractions and directionality. In this hierarchy, the single pitch or triadic chord with the greatest stability is call ...

, in his quest for greater expressivity. In his mature music dramas, '' Tristan und Isolde'', ''Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

(; "The Master-Singers of Nuremberg"), WWV 96, is a music drama, or opera, in three acts, by Richard Wagner. It is the longest opera commonly performed, taking nearly four and a half hours, not counting two breaks between acts, and is traditio ...

'', '' Der Ring des Nibelungen'' and '' Parsifal'', he abolished the distinction between aria and recitative in favour of a seamless flow of "endless melody". Wagner also brought a new philosophical dimension to opera in his works, which were usually based on stories from Germanic or Arthurian legend. Finally, Wagner built his own opera house at Bayreuth

Bayreuth (, ; bar, Bareid) is a town in northern Bavaria, Germany, on the Red Main river in a valley between the Franconian Jura and the Fichtelgebirge Mountains. The town's roots date back to 1194. In the 21st century, it is the capital of U ...

with part of the patronage from Ludwig II of Bavaria

Ludwig II (Ludwig Otto Friedrich Wilhelm; 25 August 1845 – 13 June 1886) was King of Bavaria from 1864 until his death in 1886. He is sometimes called the Swan King or ('the Fairy Tale King'). He also held the titles of Count Palatine of the ...

, exclusively dedicated to performing his own works in the style he wanted.

Opera would never be the same after Wagner and for many composers his legacy proved a heavy burden. On the other hand, Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wag ...

accepted Wagnerian ideas but took them in wholly new directions, along with incorporating the new form introduced by Verdi. He first won fame with the scandalous ''Salome

Salome (; he, שְלוֹמִית, Shlomit, related to , "peace"; el, Σαλώμη), also known as Salome III, was a Jewish princess, the daughter of Herod II, son of Herod the Great, and princess Herodias, granddaughter of Herod the Great, an ...

'' and the dark tragedy '' Elektra'', in which tonality was pushed to the limits. Then Strauss changed tack in his greatest success, '' Der Rosenkavalier'', where Mozart and Viennese waltz

The waltz ( ), meaning "to roll or revolve") is a ballroom and folk dance, normally in triple ( time), performed primarily in closed position.

History

There are many references to a sliding or gliding dance that would evolve into the wa ...

es became as important an influence as Wagner. Strauss continued to produce a highly varied body of operatic works, often with libretti by the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Other composers who made individual contributions to German opera in the early 20th century include Alexander von Zemlinsky, Erich Korngold, Franz Schreker

Franz Schreker (originally ''Schrecker''; 23 March 1878 – 21 March 1934) was an Austrian composer, conductor, teacher and administrator. Primarily a composer of operas, Schreker developed a style characterized by aesthetic plurality (a mixture ...

, Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith (; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major advocate of the ''Ne ...

, Kurt Weill

Kurt Julian Weill (March 2, 1900April 3, 1950) was a German-born American composer active from the 1920s in his native country, and in his later years in the United States. He was a leading composer for the stage who was best known for his fru ...

and the Italian-born Ferruccio Busoni

Ferruccio Busoni (1 April 1866 – 27 July 1924) was an Italian composer, pianist, conductor, editor, writer, and teacher. His international career and reputation led him to work closely with many of the leading musicians, artists and literary ...

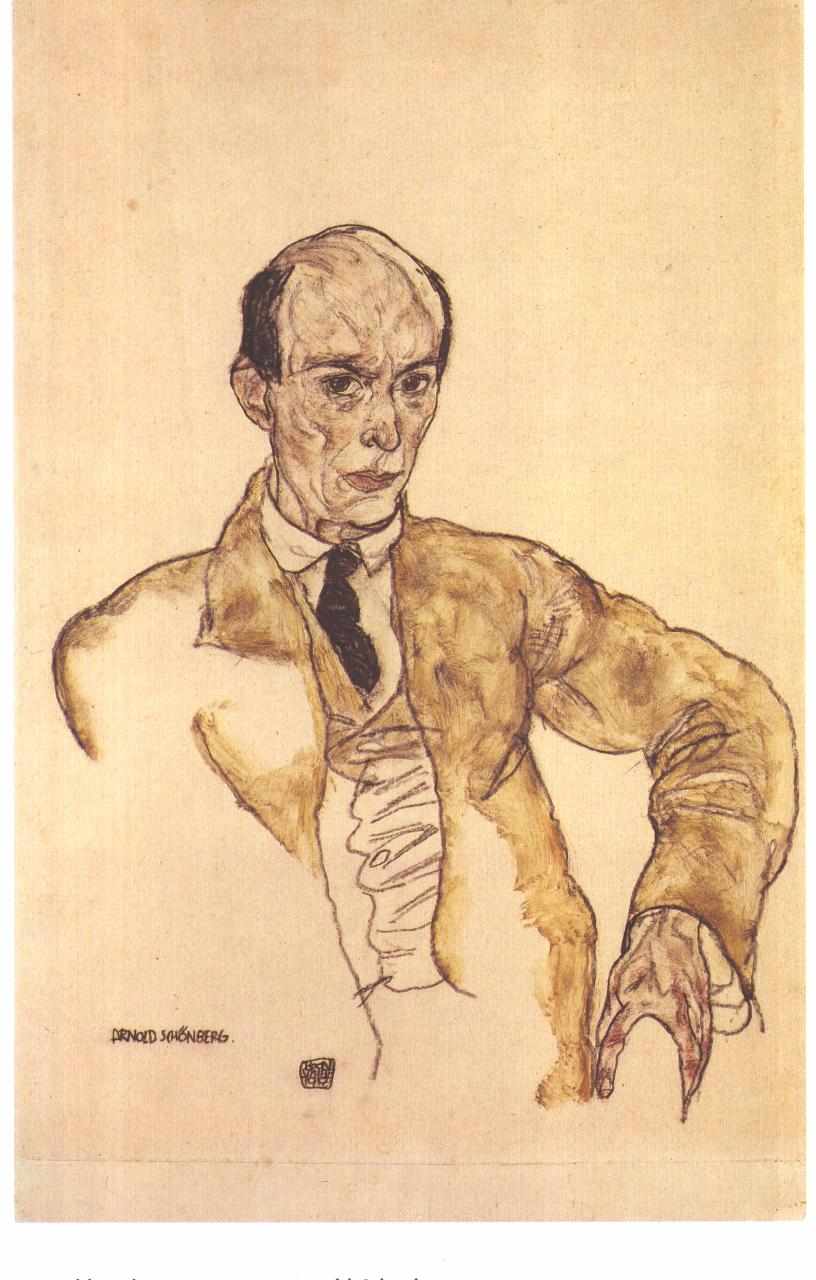

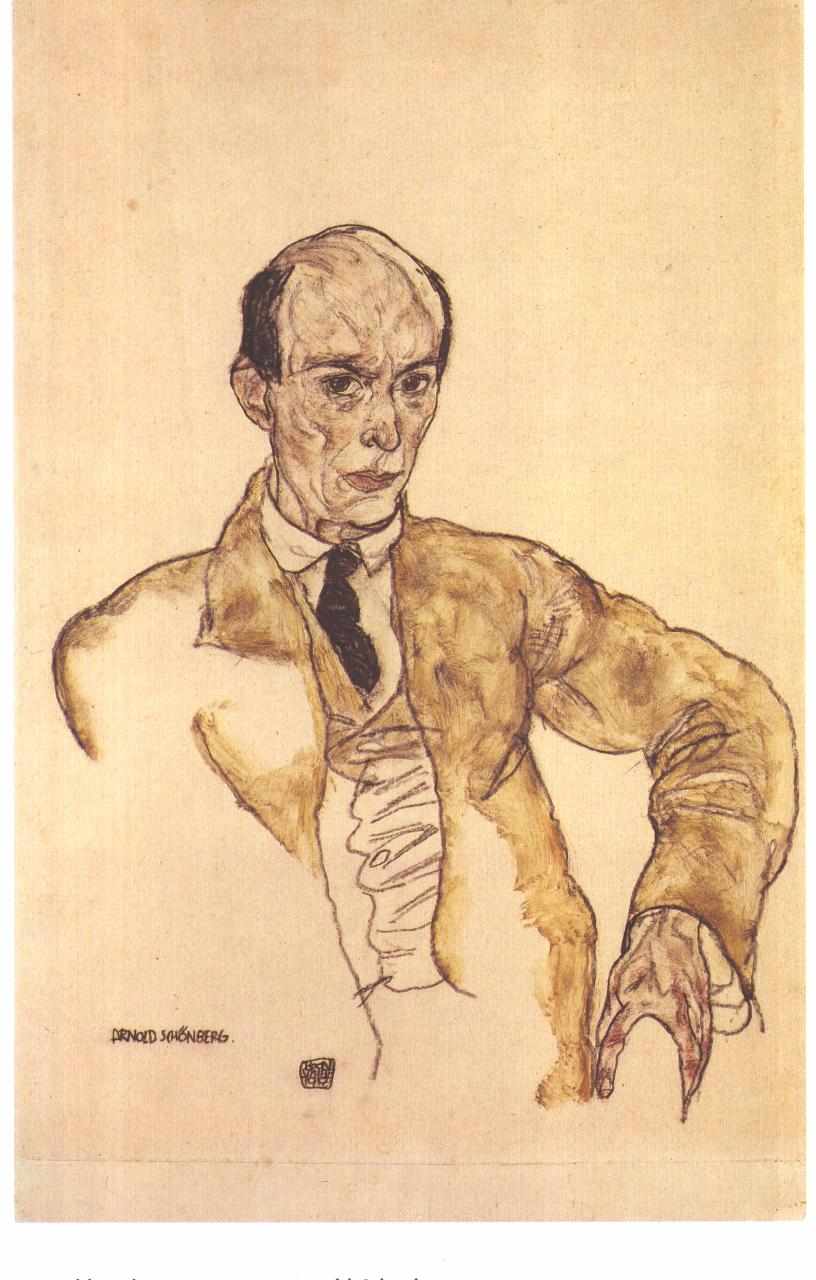

. The operatic innovations of Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

and his successors are discussed in the section on modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

.

During the late 19th century, the Austrian composer Johann Strauss II

Johann Baptist Strauss II (25 October 1825 – 3 June 1899), also known as Johann Strauss Jr., the Younger or the Son (german: links=no, Sohn), was an Austrian composer of light music, particularly dance music and operettas. He composed ov ...

, an admirer of the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

-language operetta

Operetta is a form of theatre and a genre of light opera. It includes spoken dialogue, songs, and dances. It is lighter than opera in terms of its music, orchestral size, length of the work, and at face value, subject matter. Apart from its s ...

s composed by Jacques Offenbach, composed several German-language operettas, the most famous of which was '' Die Fledermaus''. Nevertheless, rather than copying the style of Offenbach, the operettas of Strauss II had distinctly Viennese Viennese may refer to:

* Vienna, the capital of Austria

* Viennese people, List of people from Vienna

* Viennese German, the German dialect spoken in Vienna

* Music of Vienna, musical styles in the city

* Viennese Waltz, genre of ballroom dance

* V ...

flavor to them.

French opera

In rivalry with imported Italian opera productions, a separate French tradition was founded by the Italian-born French composer

In rivalry with imported Italian opera productions, a separate French tradition was founded by the Italian-born French composer Jean-Baptiste Lully

Jean-Baptiste Lully ( , , ; born Giovanni Battista Lulli, ; – 22 March 1687) was an Italian-born French composer, guitarist, violinist, and dancer who is considered a master of the French Baroque music style. Best known for his operas, he ...

at the court of King Louis XIV

Louis XIV (Louis Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was List of French monarchs, King of France from 14 May 1643 until his death in 1715. His reign of 72 years and 110 days is the Li ...

. Despite his foreign birthplace, Lully established an Academy of Music and monopolised French opera from 1672. Starting with '' Cadmus et Hermione'', Lully and his librettist Quinault Quinault may refer to:

* Quinault people, an Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast

**Quinault Indian Nation, a federally recognized tribe

**Quinault language, their language

People

* Quinault family of actors, including

* Jean-Baptis ...

created ''tragédie en musique

Tragédie en musique (, ''musical tragedy''), also known as tragédie lyrique (, ''lyric tragedy''), is a genre of French opera introduced by Jean-Baptiste Lully and used by his followers until the second half of the eighteenth century. Operas in t ...

'', a form in which dance music and choral writing were particularly prominent. Lully's operas also show a concern for expressive recitative which matched the contours of the French language. In the 18th century, Lully's most important successor was Jean-Philippe Rameau

Jean-Philippe Rameau (; – ) was a French composer and music theory, music theorist. Regarded as one of the most important French composers and music theorists of the 18th century, he replaced Jean-Baptiste Lully as the dominant composer of Fr ...

, who composed five ''tragédies en musique'' as well as numerous works in other genres such as '' opéra-ballet'', all notable for their rich orchestration and harmonic daring. Despite the popularity of Italian opera seria

''Opera seria'' (; plural: ''opere serie''; usually called ''dramma per musica'' or ''melodramma serio'') is an Italian musical term which refers to the noble and "serious" style of Italian opera that predominated in Europe from the 1710s to abo ...

throughout much of Europe during the Baroque period, Italian opera never gained much of a foothold in France, where its own national operatic tradition was more popular instead. After Rameau's death, the German Gluck

Christoph Willibald (Ritter von) Gluck (; 2 July 1714 – 15 November 1787) was a composer of Italian and French opera in the early classical period (music), classical period. Born in the Upper Palatinate and raised in Bohemia, both part of the ...

was persuaded to produce six operas for the Parisian stage in the 1770s. They show the influence of Rameau, but simplified and with greater focus on the drama. At the same time, by the middle of the 18th century another genre was gaining popularity in France: ''opéra comique

''Opéra comique'' (; plural: ''opéras comiques'') is a genre of French opera that contains spoken dialogue and arias. It emerged from the popular '' opéras comiques en vaudevilles'' of the Fair Theatres of St Germain and St Laurent (and to a l ...

''. This was the equivalent of the German singspiel

A Singspiel (; plural: ; ) is a form of German-language music drama, now regarded as a genre of opera. It is characterized by spoken dialogue, which is alternated with ensembles, songs, ballads, and arias which were often strophic, or folk-like ...

, where arias alternated with spoken dialogue. Notable examples in this style were produced by Monsigny, Philidor

Philidor (''Filidor'') or Danican Philidor was a family of musicians that served as court musicians to the French kings. The original name of the family was Danican (D'Anican) and was of Scottish origin (Duncan). Philidor was a later addition to t ...

and, above all, Grétry. During the Revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.

...

and Napoleonic

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

period, composers such as Étienne Méhul, Luigi Cherubini

Luigi Cherubini ( ; ; 8 or 14 SeptemberWillis, in Sadie (Ed.), p. 833 1760 – 15 March 1842) was an Italian Classical and Romantic composer. His most significant compositions are operas and sacred music. Beethoven regarded Cherubini as the gre ...

and Gaspare Spontini, who were followers of Gluck, brought a new seriousness to the genre, which had never been wholly "comic" in any case. Another phenomenon of this period was the 'propaganda opera' celebrating revolutionary successes, e.g. Gossec's ''Le triomphe de la République'' (1793).

By the 1820s, Gluckian influence in France had given way to a taste for Italian

By the 1820s, Gluckian influence in France had given way to a taste for Italian bel canto

Bel canto (Italian for "beautiful singing" or "beautiful song", )—with several similar constructions (''bellezze del canto'', ''bell'arte del canto'')—is a term with several meanings that relate to Italian singing.

The phrase was not associat ...

, especially after the arrival of Rossini