The heart is a muscular

organ

Organ may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a part of an organism

Musical instruments

* Organ (music), a family of keyboard musical instruments characterized by sustained tone

** Electronic organ, an electronic keyboard instrument

** Hammond ...

in most

animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and go through an ontogenetic stage ...

s. This organ pumps

blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the cir ...

through the

blood vessel

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport blood throughout the human body. These vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to the tissues of the body. They also take waste and carbon dioxide awa ...

s of the

circulatory system

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

.

The pumped blood carries

oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

and

nutrient

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow, and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excre ...

s to the body, while carrying

metabolic waste

Metabolic wastes or excrements are substances left over from metabolic processes (such as cellular respiration) which cannot be used by the organism (they are surplus or toxic), and must therefore be excreted. This includes nitrogen compounds, ...

such as

carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

to the

lung

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of ...

s. In

human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, cultu ...

s, the heart is approximately the size of a closed

fist

A fist is the shape of a hand when the fingers are bent inward against the palm and held there tightly. To make or clench a fist is to fold the fingers tightly into the center of the palm and then to clamp the thumb over the middle phalanges; in ...

and is located between the lungs, in the

middle compartment of the

chest

The thorax or chest is a part of the anatomy of humans, mammals, and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen. In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main divisions of the crea ...

.

In humans, other mammals, and birds, the heart is divided into four chambers: upper left and right

atria and lower left and right

ventricles.

Commonly the right atrium and ventricle are referred together as the

right heart and their left counterparts as the

left heart. Fish, in contrast, have two chambers, an atrium and a ventricle, while most reptiles have three chambers.

[ In a healthy heart blood flows one way through the heart due to ]heart valve

A heart valve is a one-way valve that allows blood to flow in one direction through the chambers of the heart. Four valves are usually present in a mammalian heart and together they determine the pathway of blood flow through the heart. A heart ...

s, which prevent backflow

Backflow is a term in plumbing for an unwanted flow of water in the reverse direction. It can be a serious health risk for the contamination of potable water supplies with foul water. In the most obvious case, a toilet flush cistern and its water ...

.pericardium

The pericardium, also called pericardial sac, is a double-walled sac containing the heart and the roots of the great vessels. It has two layers, an outer layer made of strong connective tissue (fibrous pericardium), and an inner layer made ...

, which also contains a small amount of fluid

In physics, a fluid is a liquid, gas, or other material that continuously deforms (''flows'') under an applied shear stress, or external force. They have zero shear modulus, or, in simpler terms, are substances which cannot resist any shear ...

. The wall of the heart is made up of three layers: epicardium

The pericardium, also called pericardial sac, is a double-walled sac containing the heart and the roots of the great vessels. It has two layers, an outer layer made of strong connective tissue (fibrous pericardium), and an inner layer made o ...

, myocardium

Cardiac muscle (also called heart muscle, myocardium, cardiomyocytes and cardiac myocytes) is one of three types of vertebrate muscle tissues, with the other two being skeletal muscle and smooth muscle. It is an involuntary, striated muscle tha ...

, and endocardium

The endocardium is the innermost layer of tissue that lines the chambers of the heart. Its cells are embryologically and biologically similar to the endothelial cells that line blood vessels. The endocardium also provides protection to the va ...

.pacemaker cells

350px, Image showing the cardiac pacemaker or SA node, the primary pacemaker within the electrical_conduction_system_of_the_heart">SA_node,_the_primary_pacemaker_within_the_electrical_conduction_system_of_the_heart.

The_muscle_contraction.htm ...

in the sinoatrial node. These generate a current that causes the heart to contract, traveling through the atrioventricular node and along the conduction system of the heart. In humans, deoxygenated blood enters the heart through the right atrium from the superior

Superior may refer to:

*Superior (hierarchy), something which is higher in a hierarchical structure of any kind

Places

*Superior (proposed U.S. state), an unsuccessful proposal for the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to form a separate state

*Lake ...

and inferior venae cavae and passes it to the right ventricle. From here it is pumped into pulmonary circulation

The pulmonary circulation is a division of the circulatory system in all vertebrates. The circuit begins with deoxygenated blood returned from the body to the right atrium of the heart where it is pumped out from the right ventricle to the lungs ...

to the lung

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of ...

s, where it receives oxygen and gives off carbon dioxide. Oxygenated blood then returns to the left atrium, passes through the left ventricle and is pumped out through the aorta

The aorta ( ) is the main and largest artery in the human body, originating from the left ventricle of the heart and extending down to the abdomen, where it splits into two smaller arteries (the common iliac arteries). The aorta distributes o ...

into systemic circulation

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, t ...

, traveling through arteries

An artery (plural arteries) () is a blood vessel in humans and most animals that takes blood away from the heart to one or more parts of the body (tissues, lungs, brain etc.). Most arteries carry oxygenated blood; the two exceptions are the pu ...

, arterioles, and capillaries

A capillary is a small blood vessel from 5 to 10 micrometres (μm) in diameter. Capillaries are composed of only the tunica intima, consisting of a thin wall of simple squamous endothelial cells. They are the smallest blood vessels in the body: ...

—where nutrient

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow, and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excre ...

s and other substances are exchanged between blood vessels and cells, losing oxygen and gaining carbon dioxide—before being returned to the heart through venule

A venule is a very small blood vessel in the microcirculation that allows blood to return from the capillary beds to drain into the larger blood vessels, the veins. Venules range from 7μm to 1mm in diameter. Veins contain approximately 70% of ...

s and vein

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated ...

s. The heart beats at a resting rate close to 72 beats per minute. Exercise

Exercise is a body activity that enhances or maintains physical fitness and overall health and wellness.

It is performed for various reasons, to aid growth and improve strength, develop muscles and the cardiovascular system, hone athletic ...

temporarily increases the rate, but lowers resting heart rate

Heart rate (or pulse rate) is the frequency of the heartbeat measured by the number of contractions (beats) of the heart per minute (bpm). The heart rate can vary according to the body's physical needs, including the need to absorb oxygen and excr ...

in the long term, and is good for heart health.

Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels. CVD includes coronary artery diseases (CAD) such as angina and myocardial infarction (commonly known as a heart attack). Other CVDs include stroke, hea ...

s (CVD) are the most common cause of death globally as of 2008, accounting for 30% of deaths.coronary artery disease

Coronary artery disease (CAD), also called coronary heart disease (CHD), ischemic heart disease (IHD), myocardial ischemia, or simply heart disease, involves the reduction of blood flow to the heart muscle due to build-up of atherosclerotic pl ...

and stroke

A stroke is a disease, medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemorr ...

.smoking

Smoking is a practice in which a substance is burned and the resulting smoke is typically breathed in to be tasted and absorbed into the bloodstream. Most commonly, the substance used is the dried leaves of the tobacco plant, which have b ...

, being overweight

Being overweight or fat is having more body fat than is optimally healthy. Being overweight is especially common where food supplies are plentiful and lifestyles are sedentary.

, excess weight reached epidemic proportions globally, with m ...

, little exercise, high cholesterol

Hypercholesterolemia, also called high cholesterol, is the presence of high levels of cholesterol in the blood. It is a form of hyperlipidemia (high levels of lipids in the blood), hyperlipoproteinemia (high levels of lipoproteins in the blood), ...

, high blood pressure

Hypertension (HTN or HT), also known as high blood pressure (HBP), is a long-term medical condition in which the blood pressure in the arteries is persistently elevated. High blood pressure usually does not cause symptoms. Long-term high bl ...

, and poorly controlled diabetes

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

, among others. Cardiovascular diseases frequently do not have symptoms or may cause chest pain

Chest pain is pain or discomfort in the chest, typically the front of the chest. It may be described as sharp, dull, pressure, heaviness or squeezing. Associated symptoms may include pain in the shoulder, arm, upper abdomen, or jaw, along with ...

or shortness of breath

Shortness of breath (SOB), also medically known as dyspnea (in AmE) or dyspnoea (in BrE), is an uncomfortable feeling of not being able to breathe well enough. The American Thoracic Society defines it as "a subjective experience of breathing di ...

. Diagnosis of heart disease is often done by the taking of a medical history

The medical history, case history, or anamnesis (from Greek: ἀνά, ''aná'', "open", and μνήσις, ''mnesis'', "memory") of a patient is information gained by a physician by asking specific questions, either to the patient or to other peo ...

, listening

Listening is giving attention to a sound or action. When listening, a person hears what others are saying and tries to understand what it means. The act of listening involves complex affective, cognitive and behavioral processes. Affective proce ...

to the heart-sounds with a stethoscope

The stethoscope is a medical device for auscultation, or listening to internal sounds of an animal or human body. It typically has a small disc-shaped resonator that is placed against the skin, and one or two tubes connected to two earpieces. ...

, ECG, echocardiogram

An echocardiography, echocardiogram, cardiac echo or simply an echo, is an ultrasound of the heart.

It is a type of medical imaging of the heart, using standard ultrasound or Doppler ultrasound.

Echocardiography has become routinely used in th ...

, and ultrasound

Ultrasound is sound waves with frequencies higher than the upper audible limit of human hearing. Ultrasound is not different from "normal" (audible) sound in its physical properties, except that humans cannot hear it. This limit varies ...

.

Structure

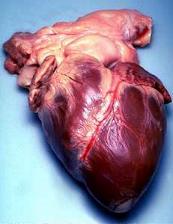

Location and shape

The human heart is situated in the

The human heart is situated in the mediastinum

The mediastinum (from ) is the central compartment of the thoracic cavity. Surrounded by loose connective tissue, it is an undelineated region that contains a group of structures within the thorax, namely the heart and its vessels, the esopha ...

, at the level of thoracic vertebrae

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebrae and they are intermediate in size between the cervical ...

T5- T8. A double-membraned sac called the pericardium

The pericardium, also called pericardial sac, is a double-walled sac containing the heart and the roots of the great vessels. It has two layers, an outer layer made of strong connective tissue (fibrous pericardium), and an inner layer made ...

surrounds the heart and attaches to the mediastinum. The back surface of the heart lies near the vertebral column

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordate ...

, and the front surface known as the sternocostal surface sits behind the sternum

The sternum or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major blood vessels from injury. Sha ...

and rib cartilages.venae cavae

In anatomy, the venae cavae (; singular: vena cava ; ) are two large veins (great vessels) that return deoxygenated blood from the body into the heart. In humans they are the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava, and both empty into th ...

, aorta

The aorta ( ) is the main and largest artery in the human body, originating from the left ventricle of the heart and extending down to the abdomen, where it splits into two smaller arteries (the common iliac arteries). The aorta distributes o ...

and pulmonary trunk

A pulmonary artery is an artery in the pulmonary circulation that carries deoxygenated blood from the right side of the heart to the lungs. The largest pulmonary artery is the ''main pulmonary artery'' or ''pulmonary trunk'' from the heart, and ...

. The upper part of the heart is located at the level of the third costal cartilage.midsternal line

The Midsternal line is used to describe a part of the surface anatomy of the anterior thorax. The midsternal line runs vertical down the middle of the sternum.

It can be interpreted as a component of the median plane.

See also

* Midclavicular l ...

) between the junction of the fourth and fifth ribs near their articulation with the costal cartilages.lungs

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either si ...

, the left lung is smaller than the right lung and has a cardiac notch in its border to accommodate the heart.athlete

An athlete (also sportsman or sportswoman) is a person who competes in one or more sports that involve physical strength, speed, or endurance.

Athletes may be professionals or amateurs. Most professional athletes have particularly well-de ...

s can have much larger hearts due to the effects of exercise on the heart muscle, similar to the response of skeletal muscle.

Chambers

The heart has four chambers, two upper atria, the receiving chambers, and two lower ventricles, the discharging chambers. The atria open into the ventricles via the

The heart has four chambers, two upper atria, the receiving chambers, and two lower ventricles, the discharging chambers. The atria open into the ventricles via the atrioventricular valve

A heart valve is a one-way valve that allows blood to flow in one direction through the chambers of the heart. Four valves are usually present in a mammalian heart and together they determine the pathway of blood flow through the heart. A heart ...

s, present in the atrioventricular septum. This distinction is visible also on the surface of the heart as the coronary sulcus

The coronary sulcus (also called coronary groove, auriculoventricular groove, atrioventricular groove, AV groove) is a groove on the surface of the heart at the base of right auricle that separates the atria from the ventricles. The structure co ...

. There is an ear-shaped structure in the upper right atrium called the right atrial appendage, or auricle, and another in the upper left atrium, the left atrial appendage

The atrium ( la, ātrium, , entry hall) is one of two upper chambers in the heart that receives blood from the circulatory system. The blood in the atria is pumped into the heart ventricles through the atrioventricular valves.

There are two at ...

. The right atrium and the right ventricle together are sometimes referred to as the right heart. Similarly, the left atrium and the left ventricle together are sometimes referred to as the left heart. The ventricles are separated from each other by the interventricular septum

The interventricular septum (IVS, or ventricular septum, or during development septum inferius) is the stout wall separating the ventricles, the lower chambers of the heart, from one another.

The ventricular septum is directed obliquely backwar ...

, visible on the surface of the heart as the anterior longitudinal sulcus

The anterior interventricular sulcus (or anterior longitudinal sulcus) is one of two grooves separating the ventricles of the heart (the other being the posterior interventricular sulcus). It is situated on the sternocostal surface of the heart, ...

and the posterior interventricular sulcus.

The fibrous

Fiber or fibre (from la, fibra, links=no) is a natural or artificial substance that is significantly longer than it is wide. Fibers are often used in the manufacture of other materials. The strongest engineering materials often incorporat ...

cardiac skeleton gives structure to the heart. It forms the atrioventricular septum, which separates the atria from the ventricles, and the fibrous rings, which serve as bases for the four heart valve

A heart valve is a one-way valve that allows blood to flow in one direction through the chambers of the heart. Four valves are usually present in a mammalian heart and together they determine the pathway of blood flow through the heart. A heart ...

s. The cardiac skeleton also provides an important boundary in the heart's electrical conduction system since collagen cannot conduct electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as describe ...

. The interatrial septum separates the atria, and the interventricular septum separates the ventricles.

Valves

The heart has four valves, which separate its chambers. One valve lies between each atrium and ventricle, and one valve rests at the exit of each ventricle.

The heart has four valves, which separate its chambers. One valve lies between each atrium and ventricle, and one valve rests at the exit of each ventricle.[

The valves between the atria and ventricles are called the atrioventricular valves. Between the right atrium and the right ventricle is the ]tricuspid valve

The tricuspid valve, or right atrioventricular valve, is on the right dorsal side of the mammalian heart, at the superior portion of the right ventricle. The function of the valve is to allow blood to flow from the right atrium to the right ven ...

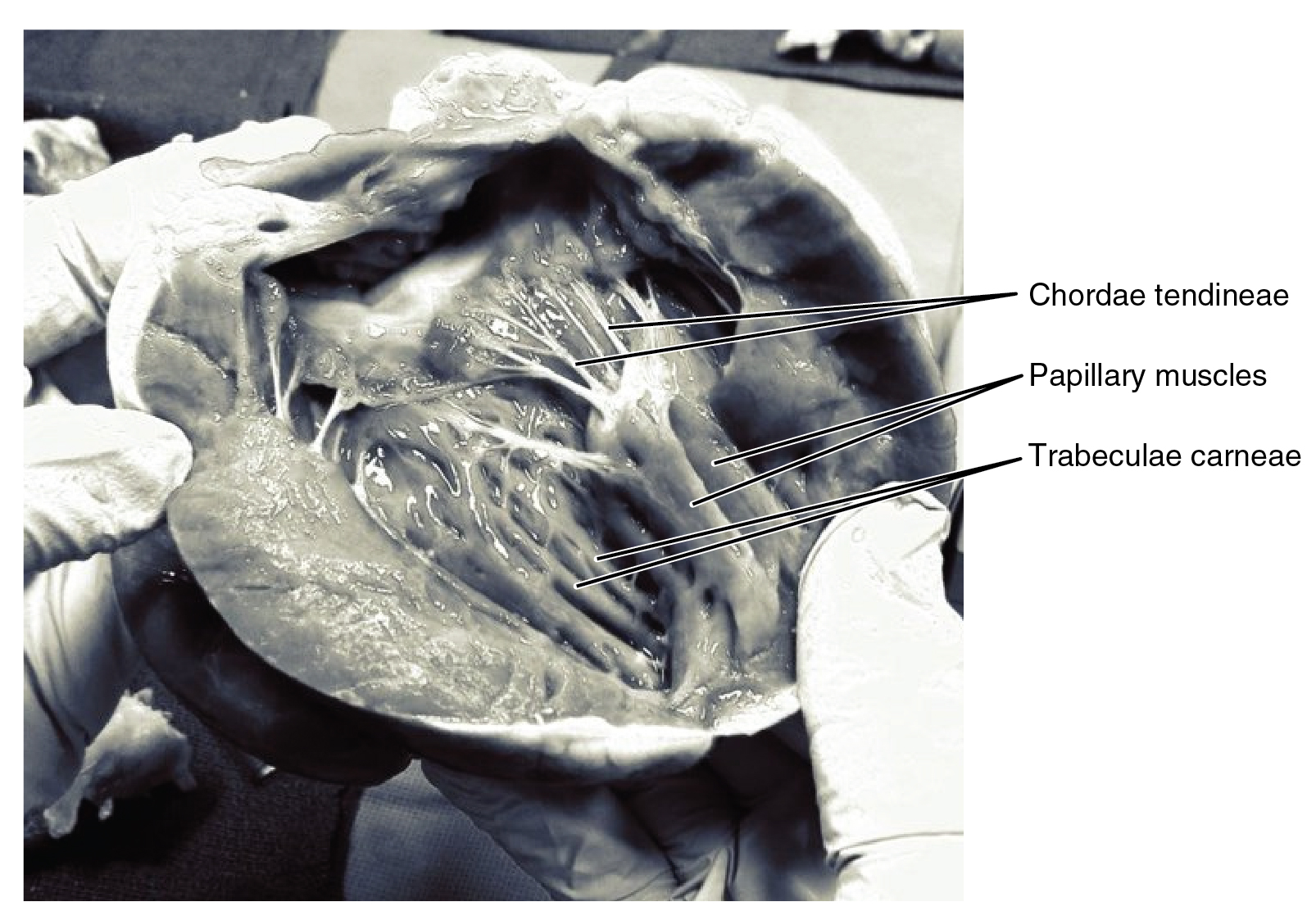

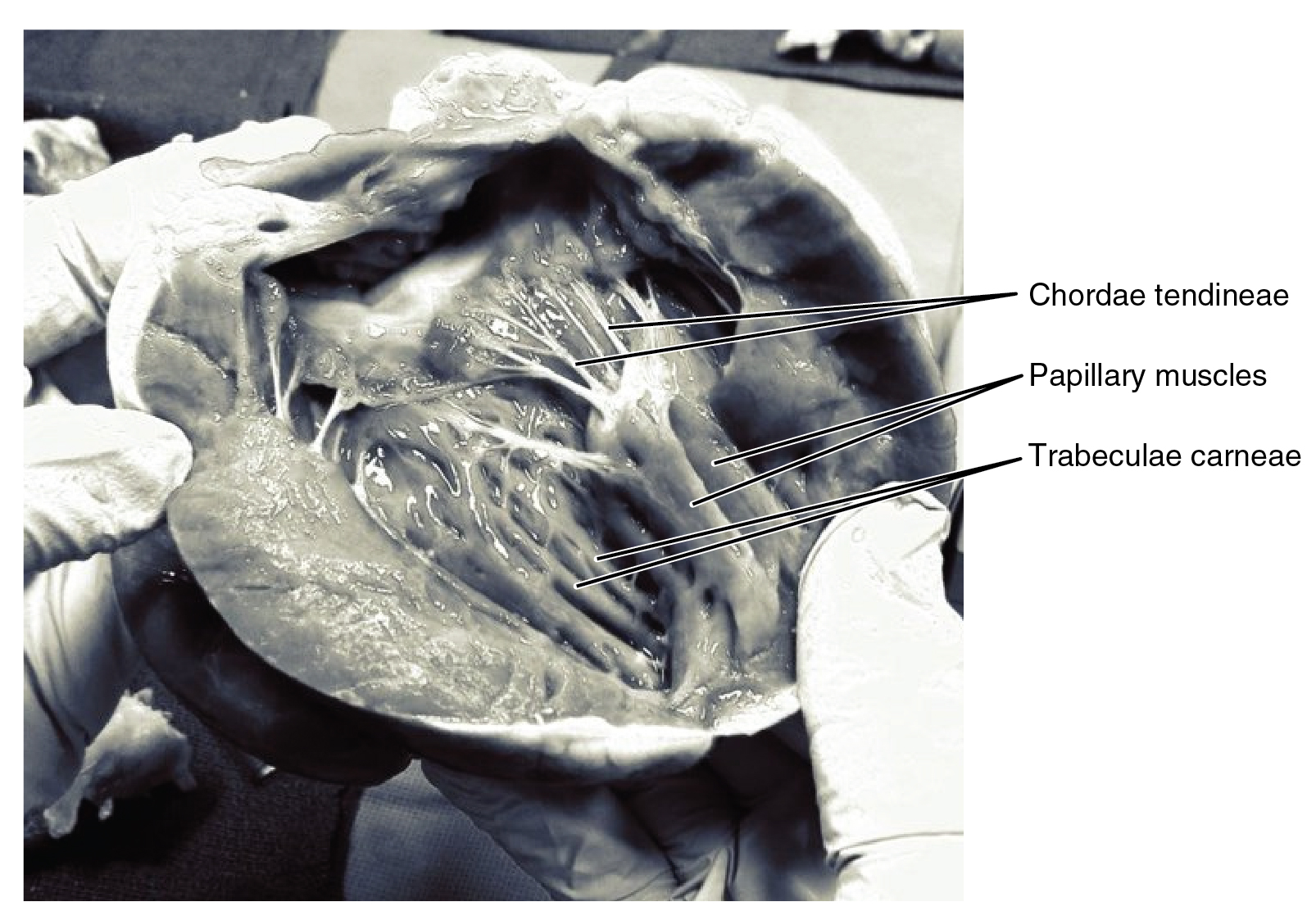

. The tricuspid valve has three cusps, which connect to chordae tendinae and three papillary muscle

The papillary muscles are muscles located in the ventricles of the heart. They attach to the cusps of the atrioventricular valves (also known as the mitral and tricuspid valves) via the chordae tendineae and contract to prevent inversion or pro ...

s named the anterior, posterior, and septal muscles, after their relative positions. The mitral valve

The mitral valve (), also known as the bicuspid valve or left atrioventricular valve, is one of the four heart valves. It has two cusps or flaps and lies between the left atrium and the left ventricle of the heart. The heart valves are all on ...

lies between the left atrium and left ventricle. It is also known as the bicuspid valve due to its having two cusps, an anterior and a posterior cusp. These cusps are also attached via chordae tendinae to two papillary muscles projecting from the ventricular wall.

The papillary muscles extend from the walls of the heart to valves by cartilaginous connections called chordae tendinae. These muscles prevent the valves from falling too far back when they close. During the relaxation phase of the cardiac cycle, the papillary muscles are also relaxed and the tension on the chordae tendineae is slight. As the heart chambers contract, so do the papillary muscles. This creates tension on the chordae tendineae, helping to hold the cusps of the atrioventricular valves in place and preventing them from being blown back into the atria.pulmonary artery

A pulmonary artery is an artery in the pulmonary circulation that carries deoxygenated blood from the right side of the heart to the lungs. The largest pulmonary artery is the ''main pulmonary artery'' or ''pulmonary trunk'' from the heart, and ...

. This has three cusps which are not attached to any papillary muscles. When the ventricle relaxes blood flows back into the ventricle from the artery and this flow of blood fills the pocket-like valve, pressing against the cusps which close to seal the valve. The semilunar aortic valve

The aortic valve is a valve in the heart of humans and most other animals, located between the left ventricle and the aorta. It is one of the four valves of the heart and one of the two semilunar valves, the other being the pulmonary valve. Th ...

is at the base of the aorta

The aorta ( ) is the main and largest artery in the human body, originating from the left ventricle of the heart and extending down to the abdomen, where it splits into two smaller arteries (the common iliac arteries). The aorta distributes o ...

and also is not attached to papillary muscles. This too has three cusps which close with the pressure of the blood flowing back from the aorta.

Right heart

The right heart consists of two chambers, the right atrium and the right ventricle, separated by a valve, the tricuspid valve

The tricuspid valve, or right atrioventricular valve, is on the right dorsal side of the mammalian heart, at the superior portion of the right ventricle. The function of the valve is to allow blood to flow from the right atrium to the right ven ...

.vein

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated ...

s, the superior

Superior may refer to:

*Superior (hierarchy), something which is higher in a hierarchical structure of any kind

Places

*Superior (proposed U.S. state), an unsuccessful proposal for the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to form a separate state

*Lake ...

and inferior venae cavae

In anatomy, the venae cavae (; singular: vena cava ; ) are two large veins (great vessels) that return deoxygenated blood from the body into the heart. In humans they are the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava, and both empty into th ...

. A small amount of blood from the coronary circulation also drains into the right atrium via the coronary sinus

In anatomy, the coronary sinus () is a collection of veins joined together to form a large vessel that collects blood from the heart muscle (myocardium). It delivers deoxygenated blood to the right atrium, as do the superior and inferior vena ...

, which is immediately above and to the middle of the opening of the inferior vena cava.pectinate muscle

The pectinate muscles (musculi pectinati) are parallel muscular ridges in the walls of the atria of the heart.

Structure

Behind the crest (crista terminalis) of the right atrium the internal surface is smooth. Pectinate muscles make up the par ...

s, which are also present in the right atrial appendage.pulmonary trunk

A pulmonary artery is an artery in the pulmonary circulation that carries deoxygenated blood from the right side of the heart to the lungs. The largest pulmonary artery is the ''main pulmonary artery'' or ''pulmonary trunk'' from the heart, and ...

, into which it ejects blood when contracting. The pulmonary trunk branches into the left and right pulmonary arteries that carry the blood to each lung. The pulmonary valve lies between the right heart and the pulmonary trunk.

Left heart

The left heart has two chambers: the left atrium and the left ventricle, separated by the mitral valve

The mitral valve (), also known as the bicuspid valve or left atrioventricular valve, is one of the four heart valves. It has two cusps or flaps and lies between the left atrium and the left ventricle of the heart. The heart valves are all on ...

.pulmonary vein

The pulmonary veins are the veins that transfer oxygenated blood from the lungs to the heart. The largest pulmonary veins are the four ''main pulmonary veins'', two from each lung that drain into the left atrium of the heart. The pulmonary vei ...

s. The left atrium has an outpouching called the left atrial appendage

The atrium ( la, ātrium, , entry hall) is one of two upper chambers in the heart that receives blood from the circulatory system. The blood in the atria is pumped into the heart ventricles through the atrioventricular valves.

There are two at ...

. Like the right atrium, the left atrium is lined by pectinate muscles. The left atrium is connected to the left ventricle by the mitral valve.right coronary artery

In the blood supply of the heart, the right coronary artery (RCA) is an artery originating above the right cusp of the aortic valve, at the right aortic sinus in the heart. It travels down the right coronary sulcus, towards the crux of the hea ...

is above the right cusp.

Wall

The heart wall is made up of three layers: the inner

The heart wall is made up of three layers: the inner endocardium

The endocardium is the innermost layer of tissue that lines the chambers of the heart. Its cells are embryologically and biologically similar to the endothelial cells that line blood vessels. The endocardium also provides protection to the va ...

, middle myocardium

Cardiac muscle (also called heart muscle, myocardium, cardiomyocytes and cardiac myocytes) is one of three types of vertebrate muscle tissues, with the other two being skeletal muscle and smooth muscle. It is an involuntary, striated muscle tha ...

and outer epicardium

The pericardium, also called pericardial sac, is a double-walled sac containing the heart and the roots of the great vessels. It has two layers, an outer layer made of strong connective tissue (fibrous pericardium), and an inner layer made o ...

. These are surrounded by a double-membraned sac called the pericardium.

The innermost layer of the heart is called the endocardium. It is made up of a lining of simple squamous epithelium

A simple squamous epithelium, also known as pavement epithelium, and tessellated epithelium is a single layer of flattened, polygonal cells in contact with the basal lamina (one of the two layers of the basement membrane) of the epithelium. This ...

and covers heart chambers and valves. It is continuous with the endothelium

The endothelium is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the rest of the ve ...

of the veins and arteries of the heart, and is joined to the myocardium with a thin layer of connective tissue.endothelins

Endothelins are peptides with receptors and effects in many body organs. Endothelin constricts blood vessels and raises blood pressure. The endothelins are normally kept in balance by other mechanisms, but when overexpressed, they contribute ...

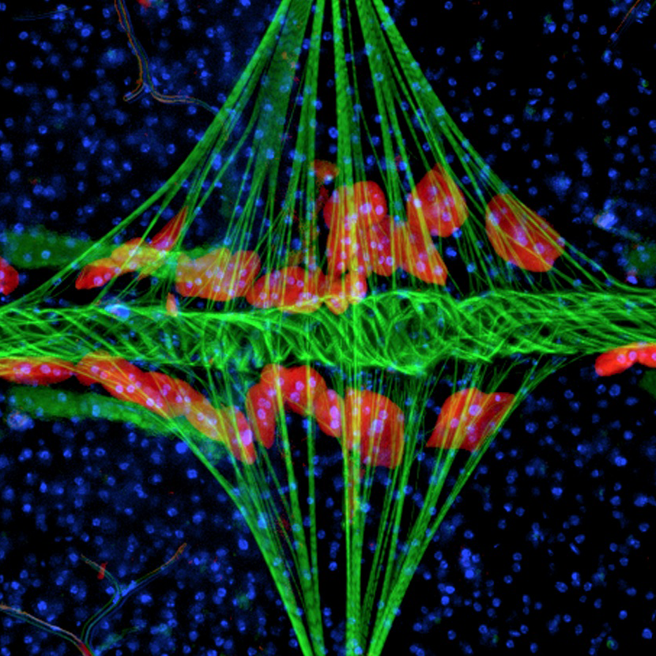

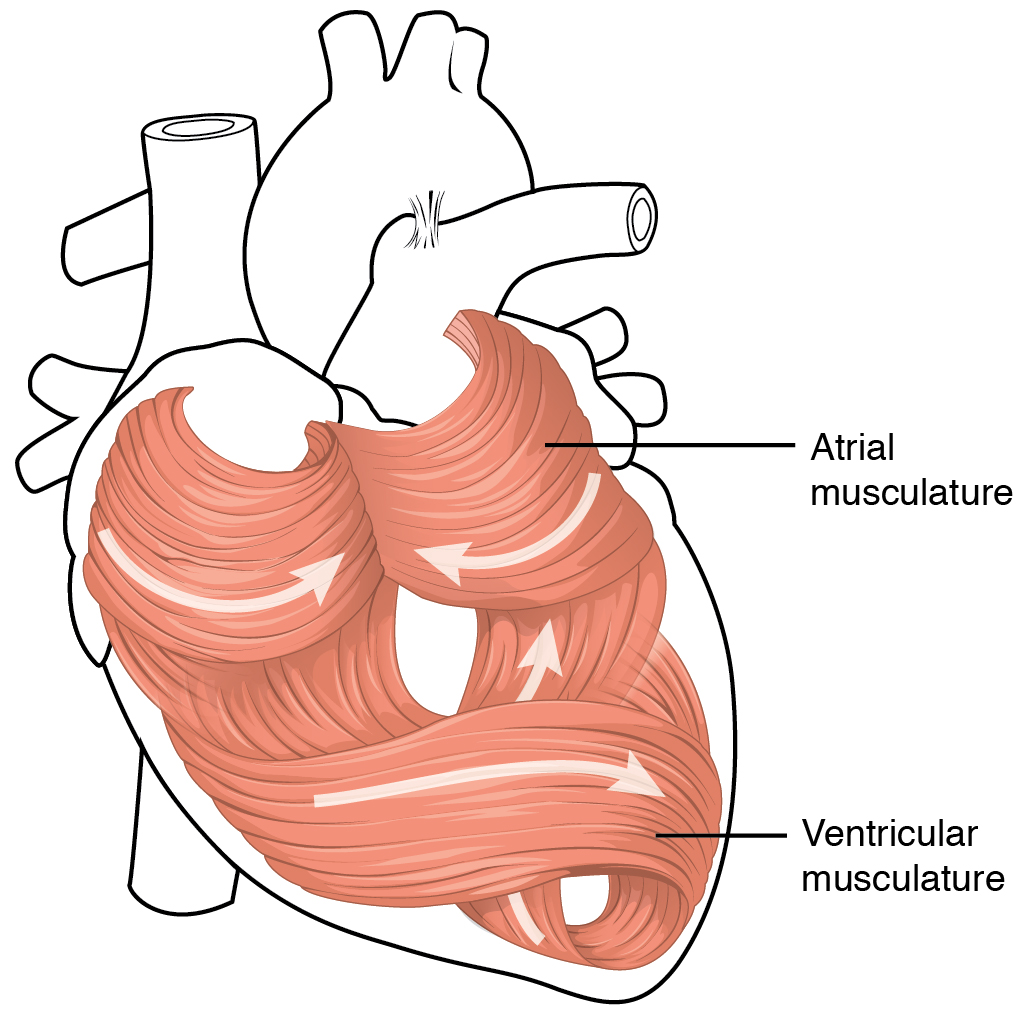

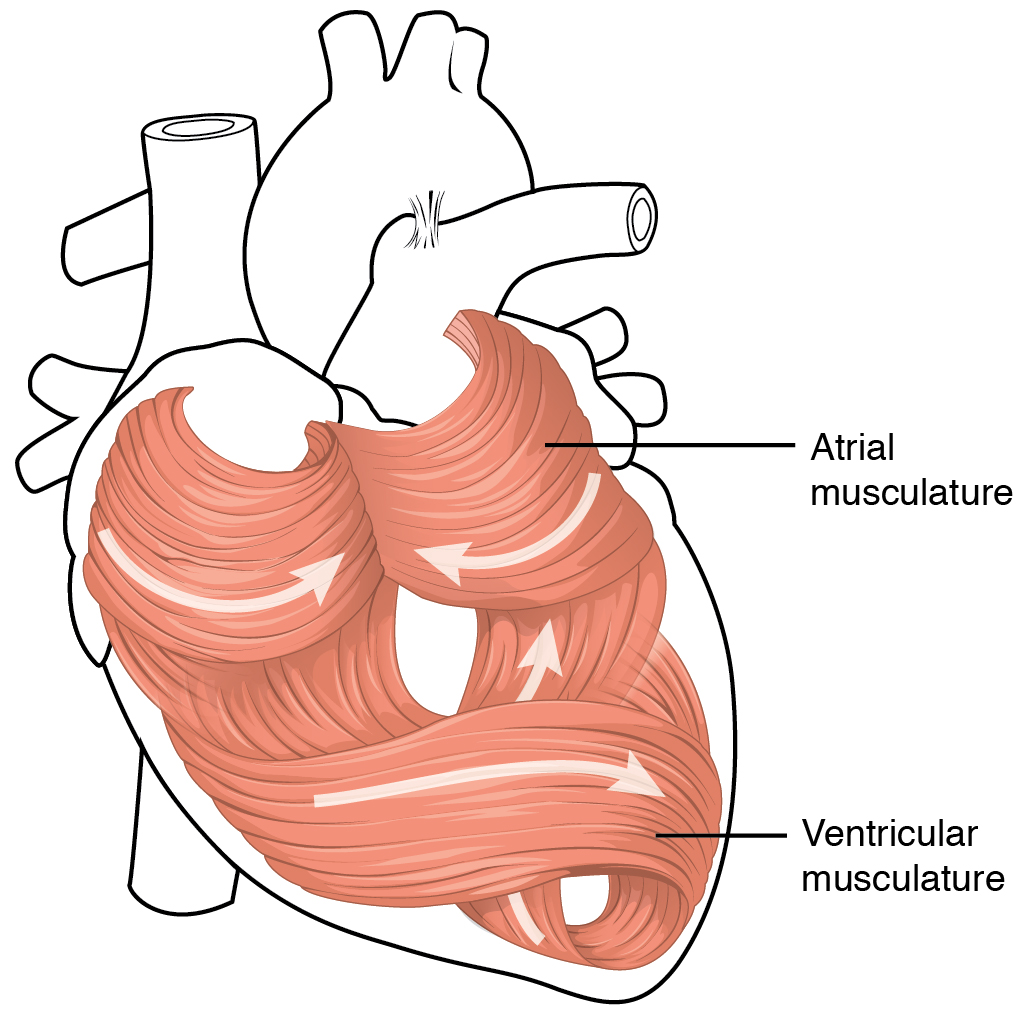

, may also play a role in regulating the contraction of the myocardium. The middle layer of the heart wall is the myocardium, which is the

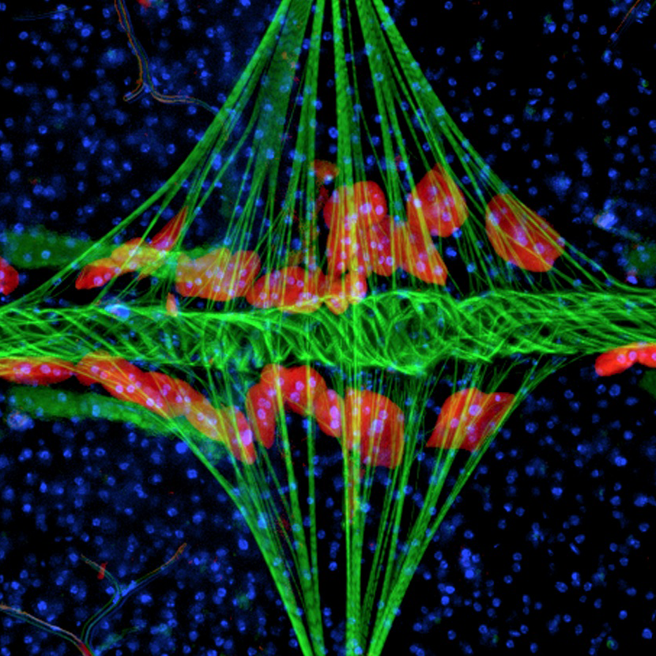

The middle layer of the heart wall is the myocardium, which is the cardiac muscle

Cardiac muscle (also called heart muscle, myocardium, cardiomyocytes and cardiac myocytes) is one of three types of vertebrate muscle tissues, with the other two being skeletal muscle and smooth muscle. It is an involuntary, striated muscle ...

—a layer of involuntary striated muscle tissue surrounded by a framework of collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix found in the body's various connective tissues. As the main component of connective tissue, it is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up from 25% to 35% of the whol ...

. The cardiac muscle pattern is elegant and complex, as the muscle cells swirl and spiral around the chambers of the heart, with the outer muscles forming a figure 8 pattern around the atria and around the bases of the great vessels and the inner muscles, forming a figure 8 around the two ventricles and proceeding toward the apex. This complex swirling pattern allows the heart to pump blood more effectively.pacemaker cells

350px, Image showing the cardiac pacemaker or SA node, the primary pacemaker within the electrical_conduction_system_of_the_heart">SA_node,_the_primary_pacemaker_within_the_electrical_conduction_system_of_the_heart.

The_muscle_contraction.htm ...

of the conducting system. The muscle cells make up the bulk (99%) of cells in the atria and ventricles. These contractile cells are connected by intercalated disc

Intercalated discs or lines of Eberth are microscopic identifying features of cardiac muscle. Cardiac muscle consists of individual heart muscle cells ( cardiomyocytes) connected by intercalated discs to work as a single functional syncytium. By c ...

s which allow a rapid response to impulses of action potential

An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific cell location rapidly rises and falls. This depolarization then causes adjacent locations to similarly depolarize. Action potentials occur in several types of animal cells ...

from the pacemaker cells. The intercalated discs allow the cells to act as a syncytium

A syncytium (; plural syncytia; from Greek: σύν ''syn'' "together" and κύτος ''kytos'' "box, i.e. cell") or symplasm is a multinucleate cell which can result from multiple cell fusions of uninuclear cells (i.e., cells with a single nucleu ...

and enable the contractions that pump blood through the heart and into the major arteries.myofibril

A myofibril (also known as a muscle fibril or sarcostyle) is a basic rod-like organelle of a muscle cell. Skeletal muscles are composed of long, tubular cells known as muscle fibers, and these cells contain many chains of myofibrils. Each myofi ...

s which gives them limited contractibility. Their function is similar in many respects to neuron

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa ...

s.autorhythmicity

The cardiac action potential is a brief change in voltage (membrane potential) across the cell membrane of heart cells. This is caused by the movement of charged atoms (called ions) between the inside and outside of the cell, through proteins ca ...

, the unique ability to initiate a cardiac action potential at a fixed rate—spreading the impulse rapidly from cell to cell to trigger the contraction of the entire heart.actin

Actin is a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells, where it may be present at a concentration of ov ...

, myosin

Myosins () are a superfamily of motor proteins best known for their roles in muscle contraction and in a wide range of other motility processes in eukaryotes. They are ATP-dependent and responsible for actin-based motility.

The first myosin (M ...

, tropomyosin

Tropomyosin is a two-stranded alpha-helical, coiled coil protein found in actin-based cytoskeletons.

Tropomyosin and the actin skeleton

All organisms contain organelles that provide physical integrity to their cells. These type of organelles ...

, and troponin

image:Troponin Ribbon Diagram.png, 400px, Ribbon representation of the human cardiac troponin core complex (52 kDa core) in the calcium-saturated form. Blue = troponin C; green = troponin I; magenta = troponin T.; ; rendered with PyMOL

Troponin, ...

. They include MYH6, ACTC1

ACTC1 encodes cardiac muscle alpha actin. This isoform differs from the alpha actin that is expressed in skeletal muscle, ACTA1. Alpha cardiac actin is the major protein of the thin filament in cardiac sarcomeres, which are responsible for muscle ...

, TNNI3, CDH2

Cadherin-2 also known as Neural cadherin (N-cadherin), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''CDH2'' gene. CDH2 has also been designated as CD325 (cluster of differentiation 325).

Cadherin-2 is a transmembrane protein expressed in multi ...

and PKP2. Other proteins expressed are MYH7 and LDB3

LIM domain binding 3 (LDB3), also known as Z-band alternatively spliced PDZ-motif (ZASP), is a protein which in humans is encoded by the ''LDB3'' gene. ZASP belongs to the Enigma subfamily of proteins and stabilizes the sarcomere (the basic units ...

that are also expressed in skeletal muscle.

Pericardium

The pericardium is the sac that surrounds the heart. The tough outer surface of the pericardium is called the fibrous membrane. This is lined by a double inner membrane called the serous membrane that produces pericardial fluid to lubricate the surface of the heart. The part of the serous membrane attached to the fibrous membrane is called the parietal pericardium, while the part of the serous membrane attached to the heart is known as the visceral pericardium. The pericardium is present in order to lubricate its movement against other structures within the chest, to keep the heart's position stabilised within the chest, and to protect the heart from infection.

Coronary circulation

Heart tissue, like all cells in the body, needs to be supplied with

Heart tissue, like all cells in the body, needs to be supplied with oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

, nutrient

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow, and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excre ...

s and a way of removing metabolic waste

Metabolic wastes or excrements are substances left over from metabolic processes (such as cellular respiration) which cannot be used by the organism (they are surplus or toxic), and must therefore be excreted. This includes nitrogen compounds, ...

s. This is achieved by the coronary circulation, which includes arteries

An artery (plural arteries) () is a blood vessel in humans and most animals that takes blood away from the heart to one or more parts of the body (tissues, lungs, brain etc.). Most arteries carry oxygenated blood; the two exceptions are the pu ...

, vein

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated ...

s, and lymphatic vessels

The lymphatic vessels (or lymph vessels or lymphatics) are thin-walled vessels (tubes), structured like blood vessels, that carry lymph. As part of the lymphatic system, lymph vessels are complementary to the cardiovascular system. Lymph vessel ...

. Blood flow through the coronary vessels occurs in peaks and troughs relating to the heart muscle's relaxation or contraction.left main coronary artery

The left coronary artery (LCA) is a coronary artery that arises from the aorta above the left cusp of the aortic valve, and feeds blood to the left side of the heart muscle. It is also known as the left main coronary artery (LMCA) and the left ma ...

and the right coronary artery

In the blood supply of the heart, the right coronary artery (RCA) is an artery originating above the right cusp of the aortic valve, at the right aortic sinus in the heart. It travels down the right coronary sulcus, towards the crux of the hea ...

. The left main coronary artery splits shortly after leaving the aorta into two vessels, the left anterior descending

The left anterior descending artery (also LAD, anterior interventricular branch of left coronary artery, or anterior descending branch) is a branch of the left coronary artery. Blockage of this artery is often called the ''widow-maker infarction' ...

and the left circumflex artery

The circumflex branch of left coronary artery, or left circumflex artery or circumflex artery, is a branch of the left coronary artery.

Description

The left circumflex artery follows the left part of the coronary sulcus, running first to the ...

. The left anterior descending artery supplies heart tissue and the front, outer side, and septum of the left ventricle. It does this by branching into smaller arteries—diagonal and septal branches. The left circumflex supplies the back and underneath of the left ventricle. The right coronary artery supplies the right atrium, right ventricle, and lower posterior sections of the left ventricle. The right coronary artery also supplies blood to the atrioventricular node (in about 90% of people) and the sinoatrial node (in about 60% of people). The right coronary artery runs in a groove at the back of the heart and the left anterior descending artery runs in a groove at the front. There is significant variation between people in the anatomy of the arteries that supply the heart The arteries divide at their furthest reaches into smaller branches that join at the edges of each arterial distribution.coronary sinus

In anatomy, the coronary sinus () is a collection of veins joined together to form a large vessel that collects blood from the heart muscle (myocardium). It delivers deoxygenated blood to the right atrium, as do the superior and inferior vena ...

is a large vein that drains into the right atrium, and receives most of the venous drainage of the heart. It receives blood from the great cardiac vein (receiving the left atrium and both ventricles), the posterior cardiac vein (draining the back of the left ventricle), the middle cardiac vein (draining the bottom of the left and right ventricles), and small cardiac veins. The anterior cardiac veins drain the front of the right ventricle and drain directly into the right atrium.plexus

In neuroanatomy, a plexus (from the Latin term for "braid") is a branching network of vessels or nerves. The vessels may be blood vessels (veins, capillaries) or lymphatic vessels. The nerves are typically axons outside the central nervous system ...

es exist beneath each of the three layers of the heart. These networks collect into a main left and a main right trunk, which travel up the groove between the ventricles that exists on the heart's surface, receiving smaller vessels as they travel up. These vessels then travel into the atrioventricular groove, and receive a third vessel which drains the section of the left ventricle sitting on the diaphragm. The left vessel joins with this third vessel, and travels along the pulmonary artery and left atrium, ending in the inferior tracheobronchial node. The right vessel travels along the right atrium and the part of the right ventricle sitting on the diaphragm. It usually then travels in front of the ascending aorta and then ends in a brachiocephalic node.

Nerve supply

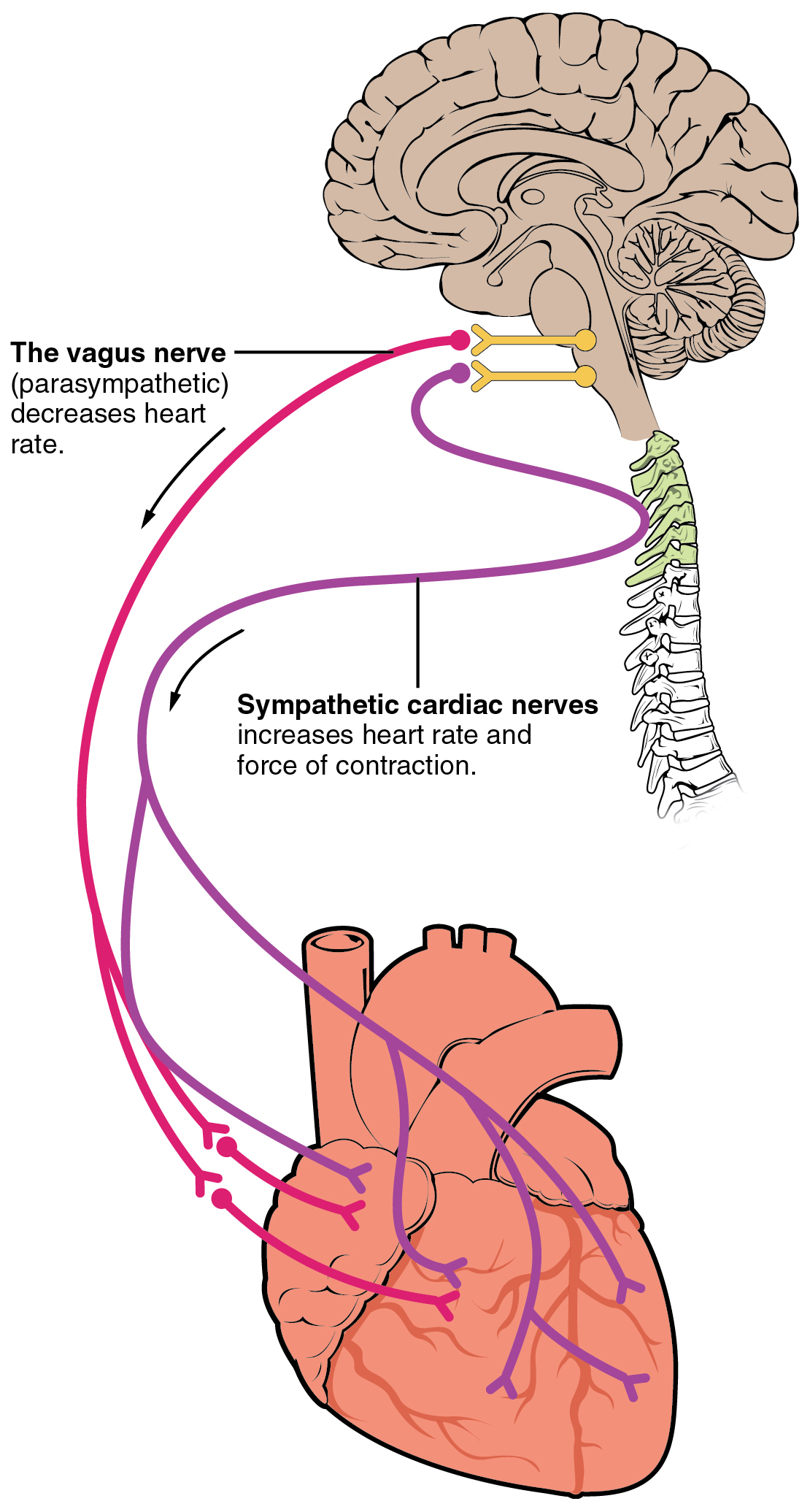

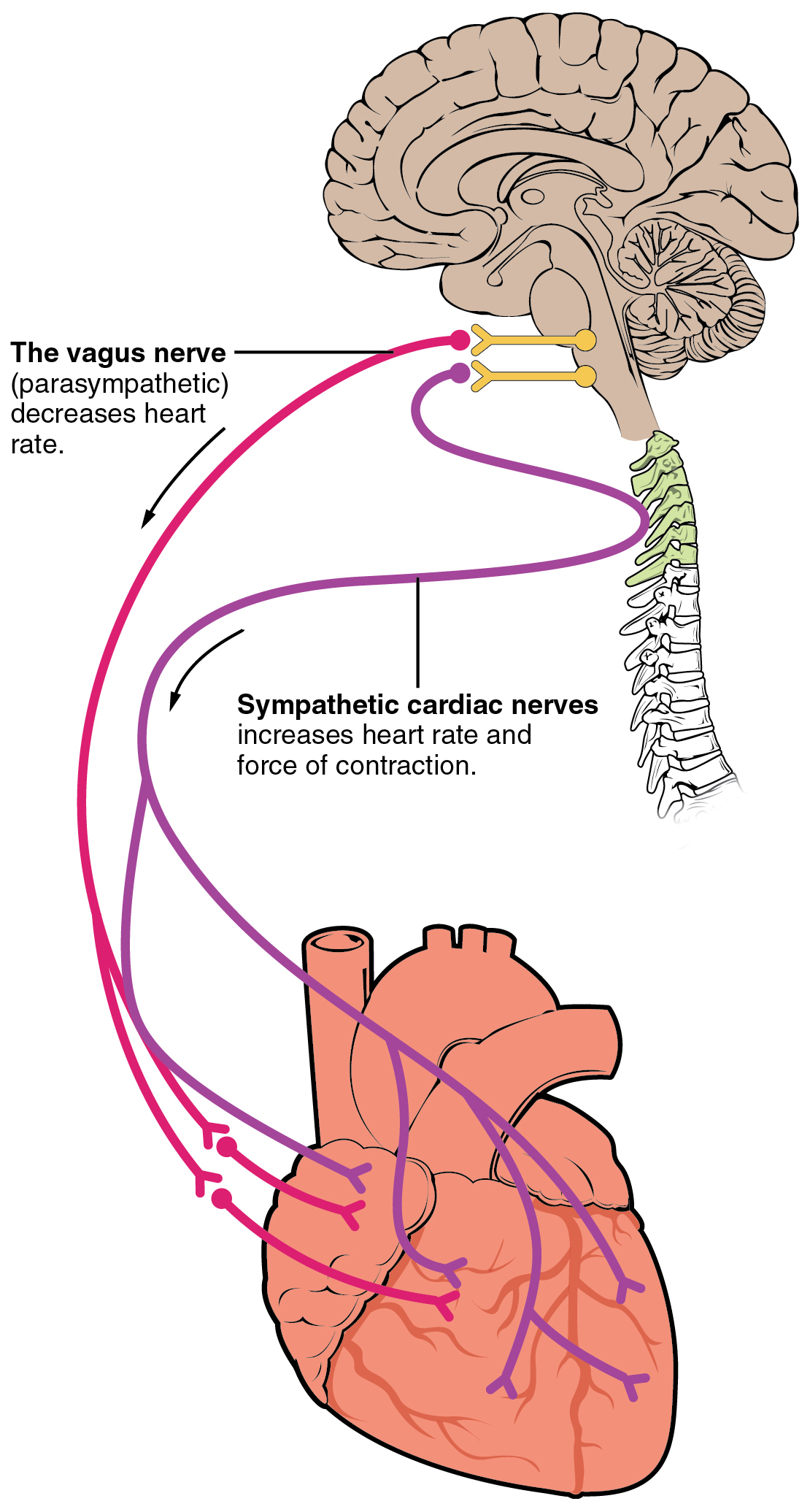

The heart receives nerve signals from the

The heart receives nerve signals from the vagus nerve

The vagus nerve, also known as the tenth cranial nerve, cranial nerve X, or simply CN X, is a cranial nerve that interfaces with the parasympathetic control of the heart, lungs, and digestive tract. It comprises two nerves—the left and righ ...

and from nerves arising from the sympathetic trunk

The sympathetic trunks (sympathetic chain, gangliated cord) are a paired bundle of nerve fibers that run from the base of the skull to the coccyx. They are a major component of the sympathetic nervous system.

Structure

The sympathetic trunk lies j ...

. These nerves act to influence, but not control, the heart rate. Sympathetic nerves

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is one of the three divisions of the autonomic nervous system, the others being the parasympathetic nervous system and the enteric nervous system. The enteric nervous system is sometimes considered part of the ...

also influence the force of heart contraction. Signals that travel along these nerves arise from two paired cardiovascular centre

The cardiovascular centre is a part of the human brain which regulates heart rate through the nervous and endocrine systems. It is considered one of the vital centres of the medulla oblongata.

Structure

The cardiovascular centre, or cardiovasc ...

s in the medulla oblongata

The medulla oblongata or simply medulla is a long stem-like structure which makes up the lower part of the brainstem. It is anterior and partially inferior to the cerebellum. It is a cone-shaped neuronal mass responsible for autonomic (invol ...

. The vagus nerve of the parasympathetic nervous system

The parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) is one of the three divisions of the autonomic nervous system, the others being the sympathetic nervous system and the enteric nervous system. The enteric nervous system is sometimes considered part o ...

acts to decrease the heart rate, and nerves from the sympathetic trunk

The sympathetic trunks (sympathetic chain, gangliated cord) are a paired bundle of nerve fibers that run from the base of the skull to the coccyx. They are a major component of the sympathetic nervous system.

Structure

The sympathetic trunk lies j ...

act to increase the heart rate.brainstem

The brainstem (or brain stem) is the posterior stalk-like part of the brain that connects the cerebrum with the spinal cord. In the human brain the brainstem is composed of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. The midbrain is ...

and provides parasympathetic stimulation to a large number of organs in the thorax and abdomen, including the heart. The nerves from the sympathetic trunk emerge through the T1-T4 thoracic ganglia and travel to both the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes, as well as to the atria and ventricles. The ventricles are more richly innervated by sympathetic fibers than parasympathetic fibers. Sympathetic stimulation causes the release of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine

Norepinephrine (NE), also called noradrenaline (NA) or noradrenalin, is an organic chemical in the catecholamine family that functions in the brain and body as both a hormone and neurotransmitter. The name "noradrenaline" (from Latin '' ad ...

(also known as noradrenaline

Norepinephrine (NE), also called noradrenaline (NA) or noradrenalin, is an organic chemical in the catecholamine family that functions in the brain and body as both a hormone and neurotransmitter. The name "noradrenaline" (from Latin '' ad'', ...

) at the neuromuscular junction

A neuromuscular junction (or myoneural junction) is a chemical synapse between a motor neuron and a muscle fiber.

It allows the motor neuron to transmit a signal to the muscle fiber, causing muscle contraction.

Muscles require innervation ...

of the cardiac nerves. This shortens the repolarization period, thus speeding the rate of depolarization and contraction, which results in an increased heart rate. It opens chemical or ligand-gated sodium and calcium ion channels, allowing an influx of positively charged ions.

Development

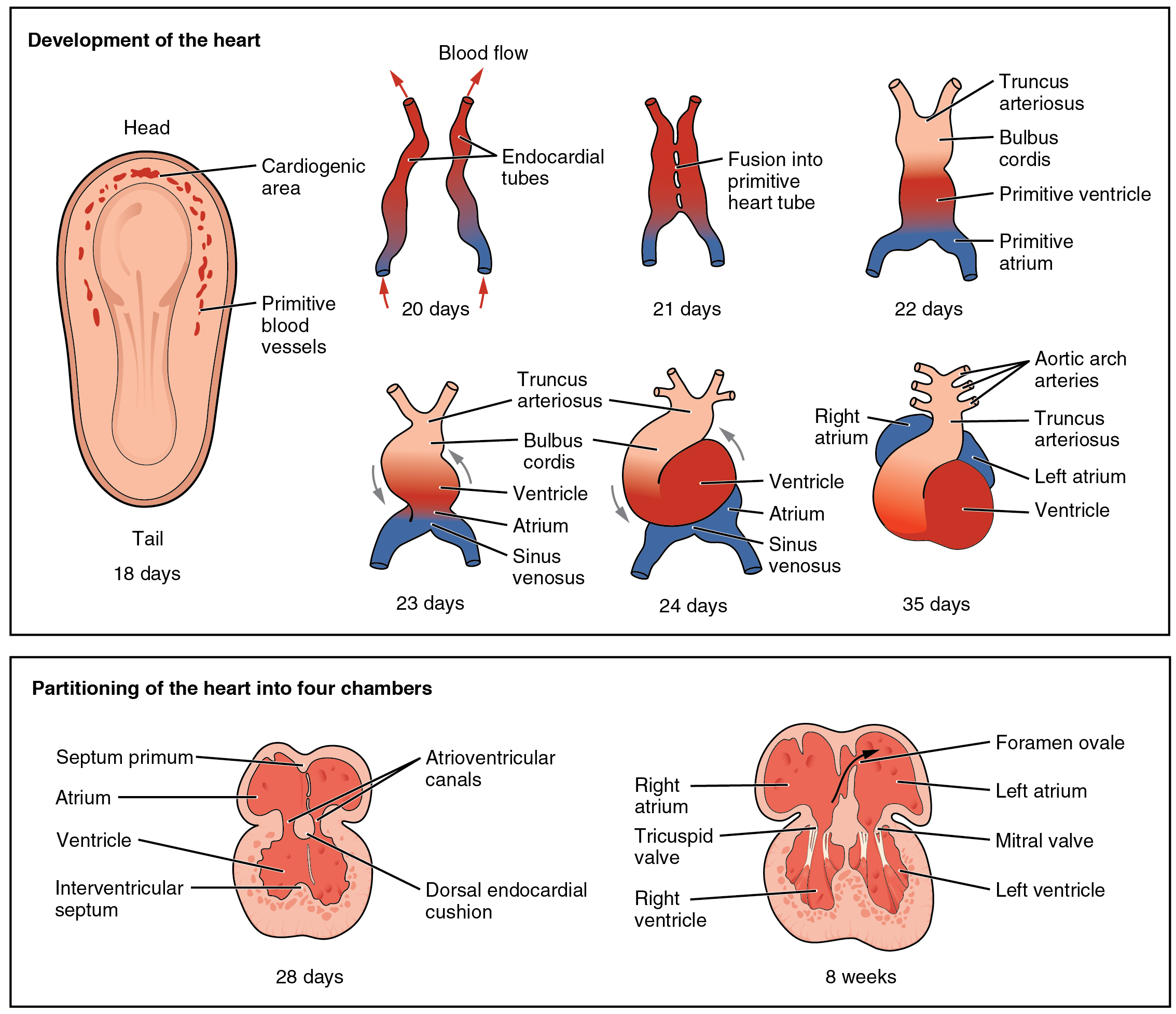

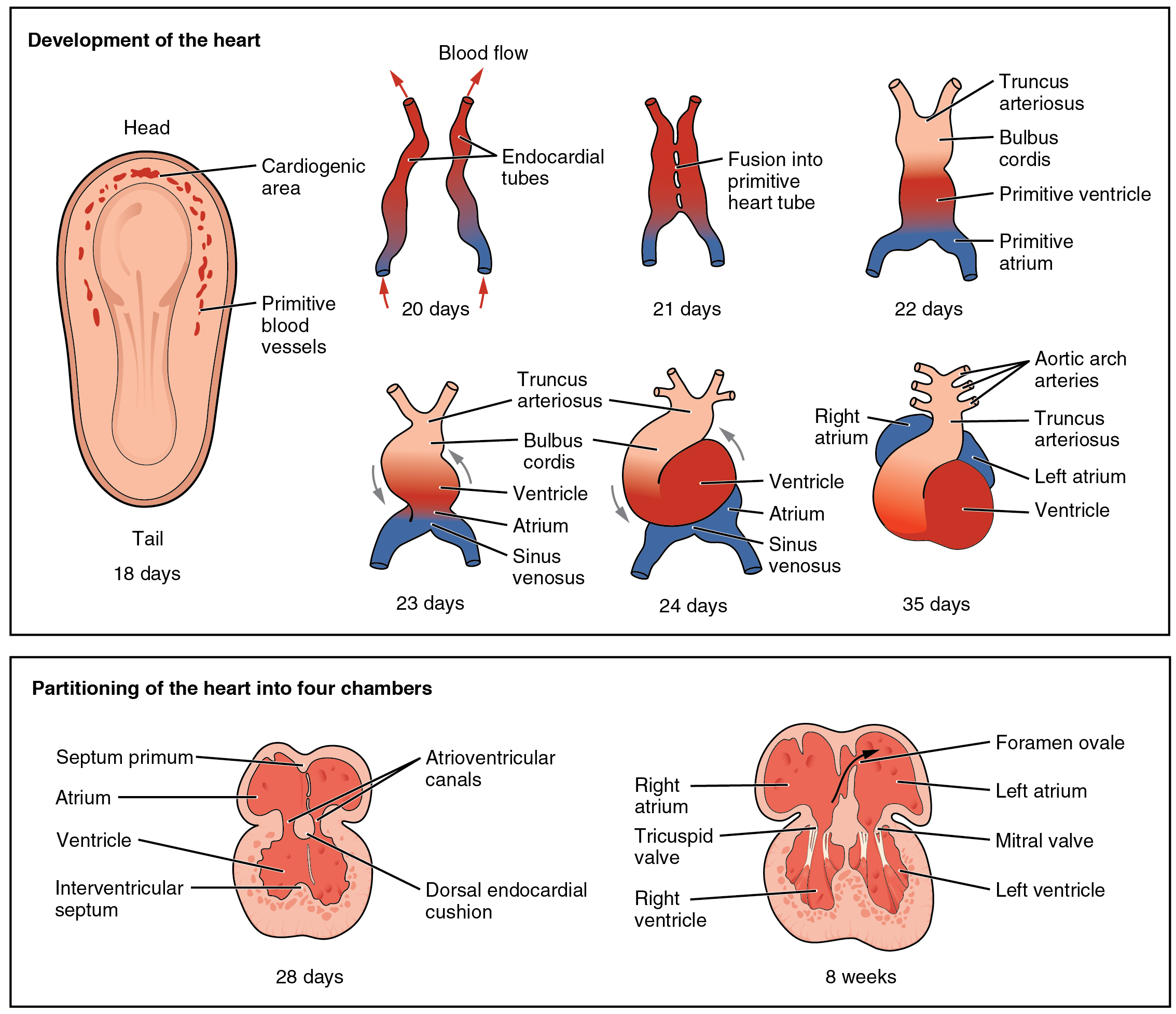

The heart is the first functional organ to develop and starts to beat and pump blood at about three weeks into

The heart is the first functional organ to develop and starts to beat and pump blood at about three weeks into embryogenesis

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

. This early start is crucial for subsequent embryonic and prenatal development

Prenatal development () includes the development of the embryo and of the fetus during a viviparous animal's gestation. Prenatal development starts with fertilization, in the germinal stage of embryonic development, and continues in fetal deve ...

.

The heart derives from splanchnopleuric mesenchyme in the neural plate which forms the cardiogenic region

Heart development, also known as cardiogenesis, refers to the prenatal development of the heart. This begins with the formation of two endocardial tubes which merge to form the tubular heart, also called the primitive heart tube. The heart is t ...

. Two endocardial tubes form here that fuse to form a primitive heart tube known as the tubular heart. Between the third and fourth week, the heart tube lengthens, and begins to fold to form an S-shape within the pericardium. This places the chambers and major vessels into the correct alignment for the developed heart. Further development will include the formation of the septa and the valves and the remodeling of the heart chambers. By the end of the fifth week, the septa are complete, and by the ninth week, the heart valves are complete.embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

nic heart begins beating at around 22 days after conception (5 weeks after the last normal menstrual period, LMP). It starts to beat at a rate near to the mother's which is about 75–80 beats per minute

Beat, beats or beating may refer to:

Common uses

* Patrol, or beat, a group of personnel assigned to monitor a specific area

** Beat (police), the territory that a police officer patrols

** Gay beat, an area frequented by gay men

* Battery ...

(bpm). The embryonic heart rate then accelerates and reaches a peak rate of 165–185 bpm early in the early 7th week (early 9th week after the LMP).[DuBose, TJ (1996) ''Fetal Sonography'', pp. 263–274; Philadelphia: WB Saunders ] After 9 weeks (start of the fetal

A fetus or foetus (; plural fetuses, feti, foetuses, or foeti) is the unborn offspring that develops from an animal embryo. Following embryonic development the fetal stage of development takes place. In human prenatal development, fetal develo ...

stage) it starts to decelerate, slowing to around 145 (±25) bpm at birth. There is no difference in female and male heart rates before birth.

Physiology

Blood flow

The heart functions as a pump in the

The heart functions as a pump in the circulatory system

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

to provide a continuous flow of blood throughout the body. This circulation consists of the systemic circulation

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, t ...

to and from the body and the pulmonary circulation

The pulmonary circulation is a division of the circulatory system in all vertebrates. The circuit begins with deoxygenated blood returned from the body to the right atrium of the heart where it is pumped out from the right ventricle to the lungs ...

to and from the lungs. Blood in the pulmonary circulation exchanges carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

for oxygen in the lungs through the process of respiration. The systemic circulation then transports oxygen to the body and returns carbon dioxide and relatively deoxygenated blood to the heart for transfer to the lungs.superior

Superior may refer to:

*Superior (hierarchy), something which is higher in a hierarchical structure of any kind

Places

*Superior (proposed U.S. state), an unsuccessful proposal for the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to form a separate state

*Lake ...

and inferior venae cavae

In anatomy, the venae cavae (; singular: vena cava ; ) are two large veins (great vessels) that return deoxygenated blood from the body into the heart. In humans they are the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava, and both empty into th ...

. Blood collects in the right and left atrium continuously.diaphragm

Diaphragm may refer to:

Anatomy

* Thoracic diaphragm, a thin sheet of muscle between the thorax and the abdomen

* Pelvic diaphragm or pelvic floor, a pelvic structure

* Urogenital diaphragm or triangular ligament, a pelvic structure

Other

* Diap ...

and empties into the upper back part of the right atrium. The inferior vena cava drains the blood from below the diaphragm and empties into the back part of the atrium below the opening for the superior vena cava. Immediately above and to the middle of the opening of the inferior vena cava is the opening of the thin-walled coronary sinus.coronary sinus

In anatomy, the coronary sinus () is a collection of veins joined together to form a large vessel that collects blood from the heart muscle (myocardium). It delivers deoxygenated blood to the right atrium, as do the superior and inferior vena ...

returns deoxygenated blood from the myocardium to the right atrium. The blood collects in the right atrium. When the right atrium contracts, the blood is pumped through the tricuspid valve

The tricuspid valve, or right atrioventricular valve, is on the right dorsal side of the mammalian heart, at the superior portion of the right ventricle. The function of the valve is to allow blood to flow from the right atrium to the right ven ...

into the right ventricle. As the right ventricle contracts, the tricuspid valve closes and the blood is pumped into the pulmonary trunk through the pulmonary valve. The pulmonary trunk divides into pulmonary arteries and progressively smaller arteries throughout the lungs, until it reaches capillaries

A capillary is a small blood vessel from 5 to 10 micrometres (μm) in diameter. Capillaries are composed of only the tunica intima, consisting of a thin wall of simple squamous endothelial cells. They are the smallest blood vessels in the body: ...

. As these pass by alveoli Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* M ...

carbon dioxide is exchanged for oxygen. This happens through the passive process of diffusion

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemical ...

.

In the left heart, oxygenated blood is returned to the left atrium via the pulmonary veins. It is then pumped into the left ventricle through the mitral valve

The mitral valve (), also known as the bicuspid valve or left atrioventricular valve, is one of the four heart valves. It has two cusps or flaps and lies between the left atrium and the left ventricle of the heart. The heart valves are all on ...

and into the aorta through the aortic valve for systemic circulation. The aorta is a large artery that branches into many smaller arteries, arterioles, and ultimately capillaries. In the capillaries, oxygen and nutrients from blood are supplied to body cells for metabolism, and exchanged for carbon dioxide and waste products.venule

A venule is a very small blood vessel in the microcirculation that allows blood to return from the capillary beds to drain into the larger blood vessels, the veins. Venules range from 7μm to 1mm in diameter. Veins contain approximately 70% of ...

s and veins that ultimately collect in the superior and inferior vena cavae, and into the right heart.

Cardiac cycle

The cardiac cycle is the sequence of events in which the heart contracts and relaxes with every heartbeat. The period of time during which the ventricles contract, forcing blood out into the aorta and main pulmonary artery, is known as

The cardiac cycle is the sequence of events in which the heart contracts and relaxes with every heartbeat. The period of time during which the ventricles contract, forcing blood out into the aorta and main pulmonary artery, is known as systole

Systole ( ) is the part of the cardiac cycle during which some chambers of the heart contract after refilling with blood. The term originates, via New Latin, from Ancient Greek (''sustolē''), from (''sustéllein'' 'to contract'; from ...

, while the period during which the ventricles relax and refill with blood is known as diastole

Diastole ( ) is the relaxed phase of the cardiac cycle when the chambers of the heart are re-filling with blood. The contrasting phase is systole when the heart chambers are contracting. Atrial diastole is the relaxing of the atria, and ventricu ...

. The atria and ventricles work in concert, so in systole when the ventricles are contracting, the atria are relaxed and collecting blood. When the ventricles are relaxed in diastole, the atria contract to pump blood to the ventricles. This coordination ensures blood is pumped efficiently to the body.mitral

The mitral valve (), also known as the bicuspid valve or left atrioventricular valve, is one of the four heart valves. It has two cusps or flaps and lies between the left atrium and the left ventricle of the heart. The heart valves are all o ...

and tricuspid

The tricuspid valve, or right atrioventricular valve, is on the right dorsal side of the mammalian heart, at the superior portion of the right ventricle. The function of the valve is to allow blood to flow from the right atrium to the right ven ...

valves. After the ventricles have completed most of their filling, the atria contract, forcing further blood into the ventricles and priming the pump. Next, the ventricles start to contract. As the pressure rises within the cavities of the ventricles, the mitral and tricuspid valves are forced shut. As the pressure within the ventricles rises further, exceeding the pressure with the aorta and pulmonary arteries, the aortic and pulmonary valves open. Blood is ejected from the heart, causing the pressure within the ventricles to fall. Simultaneously, the atria refill as blood flows into the right atrium through the superior and inferior vena cava

The inferior vena cava is a large vein that carries the deoxygenated blood from the lower and middle body into the right atrium of the heart. It is formed by the joining of the right and the left common iliac veins, usually at the level of th ...

e, and into the left atrium through the pulmonary veins. Finally, when the pressure within the ventricles falls below the pressure within the aorta and pulmonary arteries, the aortic and pulmonary valves close. The ventricles start to relax, the mitral and tricuspid valves open, and the cycle begins again.

Cardiac output

Cardiac output (CO) is a measurement of the amount of blood pumped by each ventricle (stroke volume) in one minute. This is calculated by multiplying the stroke volume (SV) by the beats per minute of the heart rate (HR). So that: CO = SV x HR.

Cardiac output (CO) is a measurement of the amount of blood pumped by each ventricle (stroke volume) in one minute. This is calculated by multiplying the stroke volume (SV) by the beats per minute of the heart rate (HR). So that: CO = SV x HR.body surface area

In physiology and medicine, the body surface area (BSA) is the measured or calculated surface area of a human body. For many clinical purposes, BSA is a better indicator of metabolic mass than body weight because it is less affected by abnormal adi ...

and is called the cardiac index Cardiac index (CI) is a haemodynamic parameter that relates the cardiac output (CO) from left ventricle in one minute to body surface area (BSA), thus relating heart performance to the size of the individual. The unit of measurement is litres per mi ...

.

The average cardiac output, using an average stroke volume of about 70mL, is 5.25 L/min, with a normal range of 4.0–8.0 L/min.echocardiogram

An echocardiography, echocardiogram, cardiac echo or simply an echo, is an ultrasound of the heart.

It is a type of medical imaging of the heart, using standard ultrasound or Doppler ultrasound.

Echocardiography has become routinely used in th ...

and can be influenced by the size of the heart, physical and mental condition of the individual, sex, contractility, duration of contraction, preload and afterload

Afterload is the pressure that the heart must work against to eject blood during systole (ventricular contraction). Afterload is proportional to the average arterial pressure. As aortic and pulmonary pressures increase, the afterload increases on ...

.Afterload

Afterload is the pressure that the heart must work against to eject blood during systole (ventricular contraction). Afterload is proportional to the average arterial pressure. As aortic and pulmonary pressures increase, the afterload increases on ...

, or how much pressure the heart must generate to eject blood at systole, is influenced by vascular resistance. It can be influenced by narrowing of the heart valves (stenosis

A stenosis (from Ancient Greek στενός, "narrow") is an abnormal narrowing in a blood vessel or other tubular organ or structure such as foramina and canals. It is also sometimes called a stricture (as in urethral stricture).

''Stricture'' ...

) or contraction or relaxation of the peripheral blood vessels.life support

Life support comprises the treatments and techniques performed in an emergency in order to support life after the failure of one or more vital organs. Healthcare providers and emergency medical technicians are generally certified to perform basic ...

, particularly in intensive care unit

220px, Intensive care unit

An intensive care unit (ICU), also known as an intensive therapy unit or intensive treatment unit (ITU) or critical care unit (CCU), is a special department of a hospital or health care facility that provides intensi ...

s. Inotropes that increase the force of contraction are "positive" inotropes, and include sympathetic agents such as adrenaline

Adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, is a hormone and medication which is involved in regulating visceral functions (e.g., respiration). It appears as a white microcrystalline granule. Adrenaline is normally produced by the adrenal glands an ...

, noradrenaline

Norepinephrine (NE), also called noradrenaline (NA) or noradrenalin, is an organic chemical in the catecholamine family that functions in the brain and body as both a hormone and neurotransmitter. The name "noradrenaline" (from Latin '' ad'', ...

and dopamine

Dopamine (DA, a contraction of 3,4-dihydroxyphenethylamine) is a neuromodulatory molecule that plays several important roles in cells. It is an organic chemical of the catecholamine and phenethylamine families. Dopamine constitutes about 80% o ...

.calcium channel blocker

Calcium channel blockers (CCB), calcium channel antagonists or calcium antagonists are a group of medications that disrupt the movement of calcium () through calcium channels. Calcium channel blockers are used as antihypertensive drugs, i.e., as ...

s.

Electrical conduction

The normal rhythmical heart beat, called

The normal rhythmical heart beat, called sinus rhythm

A sinus rhythm is any cardiac rhythm in which depolarisation of the cardiac muscle begins at the sinus node. It is characterised by the presence of correctly oriented P waves on the electrocardiogram (ECG). Sinus rhythm is necessary, but not s ...

, is established by the heart's own pacemaker, the sinoatrial node (also known as the sinus node or the SA node). Here an electrical signal is created that travels through the heart, causing the heart muscle to contract. The sinoatrial node is found in the upper part of the right atrium near to the junction with the superior vena cava. The electrical signal generated by the sinoatrial node travels through the right atrium in a radial way that is not completely understood. It travels to the left atrium via Bachmann's bundle

In the heart's conduction system, Bachmann's bundle (also called the Bachmann bundle or the interatrial band) is a branch of the anterior internodal tract that resides on the inner wall of the left atrium. It is a broad band of cardiac muscle t ...

, such that the muscles of the left and right atria contract together. The signal then travels to the atrioventricular node. This is found at the bottom of the right atrium in the atrioventricular septum, the boundary between the right atrium and the left ventricle. The septum is part of the cardiac skeleton, tissue within the heart that the electrical signal cannot pass through, which forces the signal to pass through the atrioventricular node only.bundle branches

The bundle branches, or Tawara branches, are offshoots of the bundle of His in the heart's ventricle. They play an integral role in the electrical conduction system of the heart by transmitting cardiac action potentials from the bundle of His to ...

through to the ventricles of the heart. In the ventricles the signal is carried by specialized tissue called the Purkinje fibers which then transmit the electric charge to the heart muscle.

275px, Conduction system of the heart

Heart rate

The normal

The normal resting heart rate

Heart rate (or pulse rate) is the frequency of the heartbeat measured by the number of contractions (beats) of the heart per minute (bpm). The heart rate can vary according to the body's physical needs, including the need to absorb oxygen and excr ...

is called the sinus rhythm

A sinus rhythm is any cardiac rhythm in which depolarisation of the cardiac muscle begins at the sinus node. It is characterised by the presence of correctly oriented P waves on the electrocardiogram (ECG). Sinus rhythm is necessary, but not s ...

, created and sustained by the sinoatrial node, a group of pacemaking cells found in the wall of the right atrium. Cells in the sinoatrial node do this by creating an action potential

An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific cell location rapidly rises and falls. This depolarization then causes adjacent locations to similarly depolarize. Action potentials occur in several types of animal cells ...

. The cardiac action potential

The cardiac action potential is a brief change in voltage ( membrane potential) across the cell membrane of heart cells. This is caused by the movement of charged atoms (called ions) between the inside and outside of the cell, through proteins ...

is created by the movement of specific electrolyte

An electrolyte is a medium containing ions that is electrically conducting through the movement of those ions, but not conducting electrons. This includes most soluble salts, acids, and bases dissolved in a polar solvent, such as water. Upon ...

s into and out of the pacemaker cells. The action potential then spreads to nearby cells.

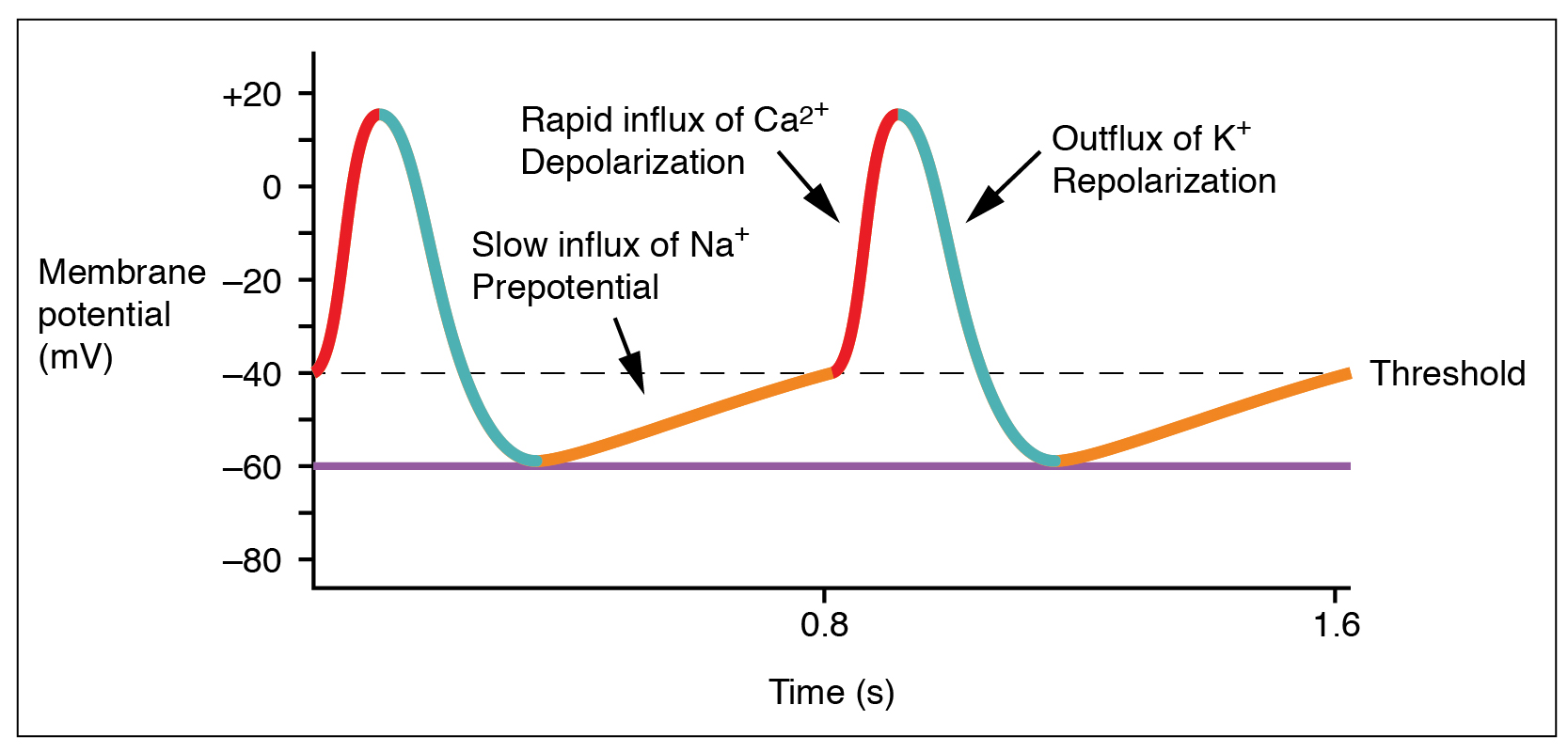

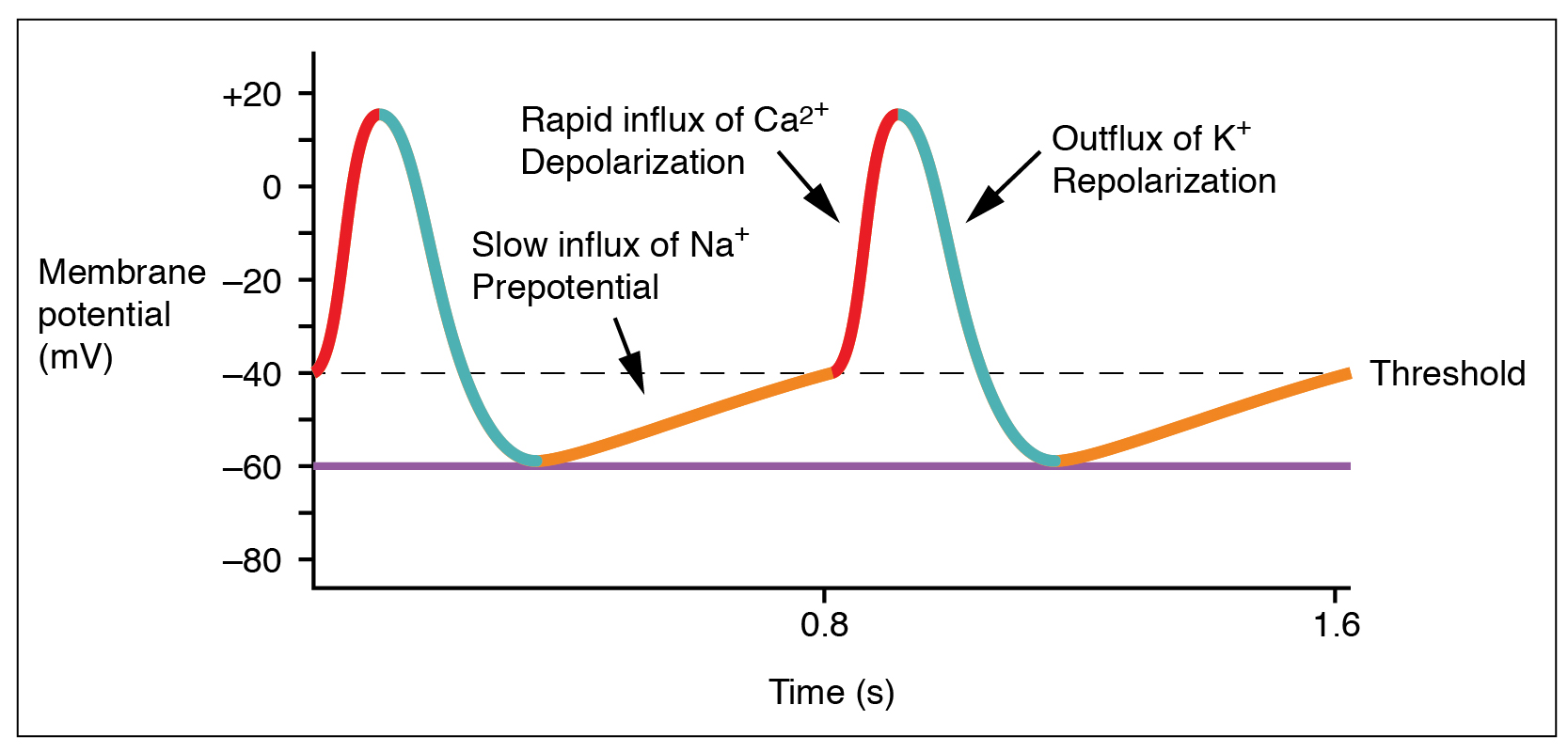

When the sinoatrial cells are resting, they have a negative charge on their membranes. A rapid influx of sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable ...

ions causes the membrane's charge to become positive; this is called depolarisation

In biology, depolarization or hypopolarization is a change within a cell, during which the cell undergoes a shift in electric charge distribution, resulting in less negative charge inside the cell compared to the outside. Depolarization is ess ...

and occurs spontaneously.calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar ...

ions then begin to enter the cell, shortly after which potassium

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin '' kalium'') and atomic number19. Potassium is a silvery-white metal that is soft enough to be cut with a knife with little force. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmos ...

begins to leave it. All the ions travel through ion channels

Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by gating the flow of i ...

in the membrane of the sinoatrial cells. The potassium and calcium start to move out of and into the cell only once it has a sufficiently high charge, and so are called voltage-gated. Shortly after this, the calcium channels close and potassium channels open, allowing potassium to leave the cell. This causes the cell to have a negative resting charge and is called repolarization

In neuroscience, repolarization refers to the change in membrane potential that returns it to a negative value just after the depolarization phase of an action potential which has changed the membrane potential to a positive value. The repolariza ...

. When the membrane potential reaches approximately −60 mV, the potassium channels close and the process may begin again.troponin C

Troponin C is a protein which is part of the troponin complex. It contains four calcium-binding EF hands, although different isoforms may have fewer than four functional calcium-binding subdomains. It is a component of thin filaments, along wi ...

in the troponin complex to enable contraction

Contraction may refer to:

Linguistics

* Contraction (grammar), a shortened word

* Poetic contraction, omission of letters for poetic reasons

* Elision, omission of sounds

** Syncope (phonology), omission of sounds in a word

* Synalepha, merged ...

of the cardiac muscle, and separate from the protein to allow relaxation.

Influences

The normal sinus rhythm

A sinus rhythm is any cardiac rhythm in which depolarisation of the cardiac muscle begins at the sinus node. It is characterised by the presence of correctly oriented P waves on the electrocardiogram (ECG). Sinus rhythm is necessary, but not s ...

of the heart, giving the resting heart rate, is influenced by a number of factors. The cardiovascular centre

The cardiovascular centre is a part of the human brain which regulates heart rate through the nervous and endocrine systems. It is considered one of the vital centres of the medulla oblongata.

Structure

The cardiovascular centre, or cardiovasc ...

s in the brainstem control the sympathetic and parasympathetic influences to the heart through the vagus nerve and sympathetic trunk.baroreceptor

Baroreceptors (or archaically, pressoreceptors) are sensors located in the carotid sinus (at the bifurcation of external and internal carotids) and in the aortic arch. They sense the blood pressure and relay the information to the brain, so that ...

s, sensing the stretching of blood vessels and chemoreceptors, sensing the amount of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood and its pH. Through a series of reflexes these help regulate and sustain blood flow.basal metabolic rate

Basal metabolic rate (BMR) is the rate of energy expenditure per unit time by endothermic animals at rest. It is reported in energy units per unit time ranging from watt (joule/second) to ml O2/min or joule per hour per kg body mass J/(h·kg). P ...

, and even a person's emotional state can all affect the heart rate. High levels of the hormones epinephrine

Adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, is a hormone and medication which is involved in regulating visceral functions (e.g., respiration). It appears as a white microcrystalline granule. Adrenaline is normally produced by the adrenal glands and ...

, norepinephrine, and thyroid hormone

File:Thyroid_system.svg, upright=1.5, The thyroid system of the thyroid hormones T3 and T4

rect 376 268 820 433 Thyroid-stimulating hormone

rect 411 200 849 266 Thyrotropin-releasing hormone

rect 297 168 502 200 Hypothalamus

rect 66 216 386 25 ...

s can increase the heart rate. The levels of electrolytes including calcium, potassium, and sodium can also influence the speed and regularity of the heart rate; low blood oxygen, low blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term "blood pressure ...

and dehydration

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water, with an accompanying disruption of metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds free water intake, usually due to exercise, disease, or high environmental temperature. Mil ...

may increase it.

Clinical significance

Diseases

Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels. CVD includes coronary artery diseases (CAD) such as angina and myocardial infarction (commonly known as a heart attack). Other CVDs include stroke, hea ...

s, which include diseases of the heart, are the leading cause of death worldwide.high-income countries

A high-income economy is defined by the World Bank as a nation with a gross national income per capita of US$12,696 or more in 2020, calculated using the Atlas method. While the term "high-income" is often used interchangeably with "First World" a ...

.cardiologist

Cardiology () is a branch of medicine that deals with disorders of the heart and the cardiovascular system. The field includes medical diagnosis and treatment of congenital heart defects, coronary artery disease, heart failure, valvular ...

s. Many other medical professionals are involved in treating diseases of the heart, including doctors, cardiothoracic surgeon

Cardiothoracic surgery is the field of medicine involved in surgical treatment of organs inside the thoracic cavity — generally treatment of conditions of the heart (heart disease), lungs (lung disease), and other pleural or mediastinal stru ...

s, intensivist

An intensivist is a medical practitioner who specializes in the care of critically ill patients, most often in the intensive care unit (ICU). Intensivists can be internists or internal medicine sub-specialists (most often pulmonologists), anesthes ...

s, and allied health practitioners including physiotherapist

Physical therapy (PT), also known as physiotherapy, is one of the allied health professions. It is provided by physical therapists who promote, maintain, or restore health through physical examination, diagnosis, management, prognosis, patien ...

s and dietician

A dietitian, medical dietitian, or dietician is an expert in identifying and treating disease-related malnutrition and in conducting medical nutrition therapy, for example designing an enteral tube feeding regimen or mitigating the effects of ca ...

s.

Ischemic heart disease

Coronary artery disease, also known as ischemic heart disease, is caused by atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a pattern of the disease arteriosclerosis in which the wall of the artery develops abnormalities, called lesions. These lesions may lead to narrowing due to the buildup of atheromatous plaque. At onset there are usually no s ...

—a build-up of fatty material along the inner walls of the arteries. These fatty deposits known as atherosclerotic plaques narrow the coronary arteries, and if severe may reduce blood flow to the heart.angina

Angina, also known as angina pectoris, is chest pain or pressure, usually caused by insufficient blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium). It is most commonly a symptom of coronary artery disease.

Angina is typically the result of obstr ...

) or breathlessness during exercise or even at rest. The thin covering of an atherosclerotic plaque can rupture, exposing the fatty centre to the circulating blood. In this case a clot or thrombus can form, blocking the artery, and restricting blood flow to an area of heart muscle causing a myocardial infarction (a heart attack) or unstable angina. In the worst case this may cause cardiac arrest, a sudden and utter loss of output from the heart. Obesity

Obesity is a medical condition, sometimes considered a disease, in which excess body fat has accumulated to such an extent that it may negatively affect health. People are classified as obese when their body mass index (BMI)—a person's ...

, high blood pressure