Iron () is a

chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

with

symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

Fe (from la,

ferrum) and

atomic number

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol ''Z'') of a chemical element is the charge number of an atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei, this is equal to the proton number (''n''p) or the number of protons found in the nucleus of every ...

26. It is a

metal

A metal (from Greek μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. Metals are typi ...

that belongs to the

first transition series and

group 8 of the

periodic table

The periodic table, also known as the periodic table of the (chemical) elements, is a rows and columns arrangement of the chemical elements. It is widely used in chemistry, physics, and other sciences, and is generally seen as an icon of ...

. It is,

by mass, the most common element on

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surf ...

, right in front of

oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as we ...

(32.1% and 30.1%, respectively), forming much of Earth's

outer and

inner core

Earth's inner core is the innermost geologic layer of planet Earth. It is primarily a solid ball with a radius of about , which is about 20% of Earth's radius or 70% of the Moon's radius.

There are no samples of Earth's core accessible for ...

. It is the fourth most common

element in the Earth's crust.

In its metallic state, iron is rare in the

Earth's crust

Earth's crust is Earth's thin outer shell of rock, referring to less than 1% of Earth's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a division of Earth's layers that includes the crust and the upper part of the mantle. The ...

, limited mainly to deposition by

meteorites

A meteorite is a solid piece of debris from an object, such as a comet, asteroid, or meteoroid, that originates in outer space and survives its passage through the atmosphere to reach the surface of a planet or moon. When the original object e ...

.

Iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the ...

s, by contrast, are among the most abundant in the Earth's crust, although extracting usable metal from them requires

kiln

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, a type of oven, that produces temperatures sufficient to complete some process, such as hardening, drying, or chemical changes. Kilns have been used for millennia to turn objects made from clay int ...

s or

furnaces capable of reaching or higher, about higher than that required to

smelt copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish ...

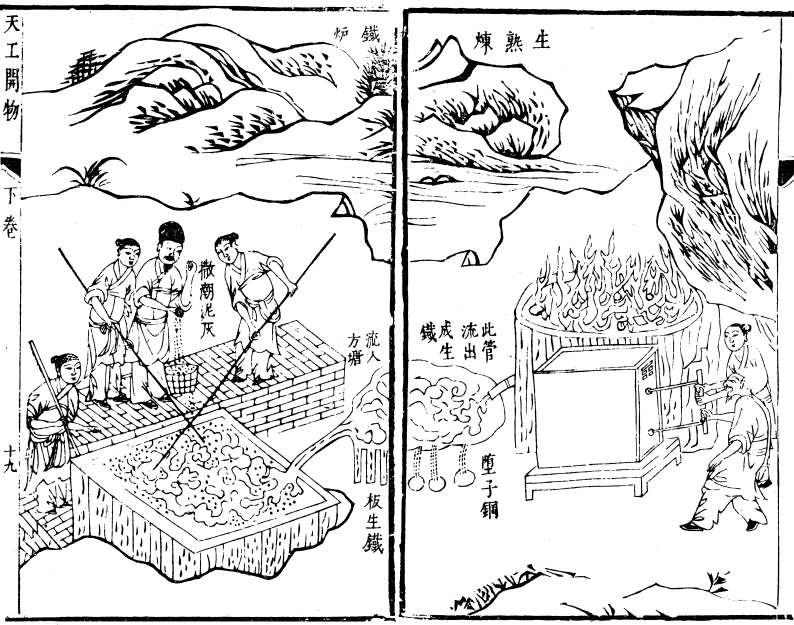

. Humans started to master that process in

Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

during the

2nd millennium BCE

The 2nd millennium BC spanned the years 2000 BC to 1001 BC.

In the Ancient Near East, it marks the transition from the Middle to the Late Bronze Age.

The Ancient Near Eastern cultures are well within the historical era:

The first half of the mil ...

and the use of iron

tool

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates ba ...

s and

weapon

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, ...

s began to displace

copper alloys, in some regions, only around 1200 BCE. That event is considered the transition from the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

to the

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

. In the

modern world, iron alloys, such as

steel,

stainless steel,

cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impu ...

and

special steels, are by far the most common industrial metals, because of their mechanical properties and low cost. The

iron and steel industry is thus very important economically, and iron is the cheapest metal, with a price of a few dollars per kilogram or per pound (see

Metal#uses).

Pristine and smooth pure iron surfaces are mirror-like silvery-gray. However, iron reacts readily with

oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as we ...

and

water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as ...

to give brown to black

hydrated

iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of w ...

s, commonly known as

rust

Rust is an iron oxide, a usually reddish-brown oxide formed by the reaction of iron and oxygen in the catalytic presence of water or air moisture. Rust consists of hydrous iron(III) oxides (Fe2O3·nH2O) and iron(III) oxide-hydroxide (FeO(OH), ...

. Unlike the oxides of some other metals that form

passivating layers, rust occupies more volume than the metal and thus flakes off, exposing more fresh surfaces for corrosion. Although iron readily reacts, high purity iron, called

electrolytic iron, has better corrosion resistance.

The body of an adult human contains about 4 grams (0.005% body weight) of iron, mostly in

hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

and

myoglobin

Myoglobin (symbol Mb or MB) is an iron- and oxygen-binding protein found in the cardiac and skeletal muscle tissue of vertebrates in general and in almost all mammals. Myoglobin is distantly related to hemoglobin. Compared to hemoglobin, myoglobi ...

. These two

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respon ...

s play essential roles in

vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxon, taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () (chordates with vertebral column, backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the ...

metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run c ...

, respectively

oxygen transport

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the ci ...

by

blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in th ...

and oxygen storage in

muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are Organ (biology), organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other ...

s. To maintain the necessary levels,

human iron metabolism requires a minimum of iron in the diet. Iron is also the metal at the active site of many important

redox

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate (chemistry), substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of Electron, electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction ...

enzymes dealing with

cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be des ...

and

oxidation and reduction in plants and animals.

Chemically, the most common oxidation states of iron are

iron(II) and

iron(III). Iron shares many properties of other

transition metal

In chemistry, a transition metal (or transition element) is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table (groups 3 to 12), though the elements of group 12 (and less often group 3) are sometimes excluded. They are the elements that c ...

s, including the other

group 8 elements,

ruthenium

Ruthenium is a chemical element with the symbol Ru and atomic number 44. It is a rare transition metal belonging to the platinum group of the periodic table. Like the other metals of the platinum group, ruthenium is inert to most other chemic ...

and

osmium

Osmium (from Greek grc, ὀσμή, osme, smell, label=none) is a chemical element with the symbol Os and atomic number 76. It is a hard, brittle, bluish-white transition metal in the platinum group that is found as a trace element in alloys, mos ...

. Iron forms compounds in a wide range of

oxidation state

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical charge of an atom if all of its bonds to different atoms were fully ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons) of an atom in a chemical compound. ...

s, −2 to +7. Iron also forms many

coordination compound

A coordination complex consists of a central atom or ion, which is usually metallic and is called the ''coordination centre'', and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions, that are in turn known as ''ligands'' or complexing agents. Many ...

s; some of them, such as

ferrocene

Ferrocene is an organometallic compound with the formula . The molecule is a complex consisting of two cyclopentadienyl rings bound to a central iron atom. It is an orange solid with a camphor-like odor, that sublimes above room temperature, ...

,

ferrioxalate, and

Prussian blue

Prussian blue (also known as Berlin blue, Brandenburg blue or, in painting, Parisian or Paris blue) is a dark blue pigment produced by oxidation of ferrous ferrocyanide salts. It has the chemical formula Fe Cyanide.html" ;"title="e(Cyanide">CN ...

, have substantial industrial, medical, or research applications.

Characteristics

Allotropes

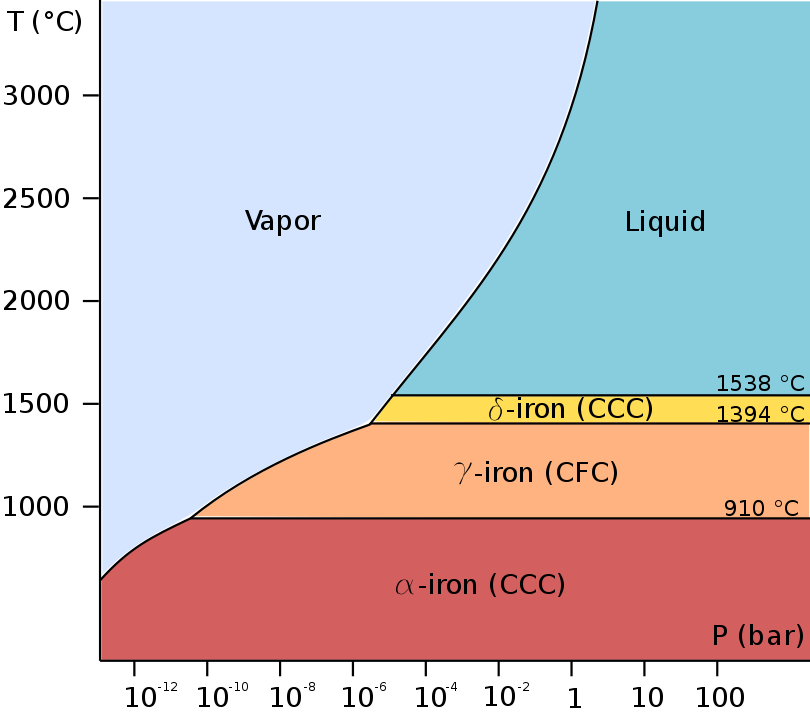

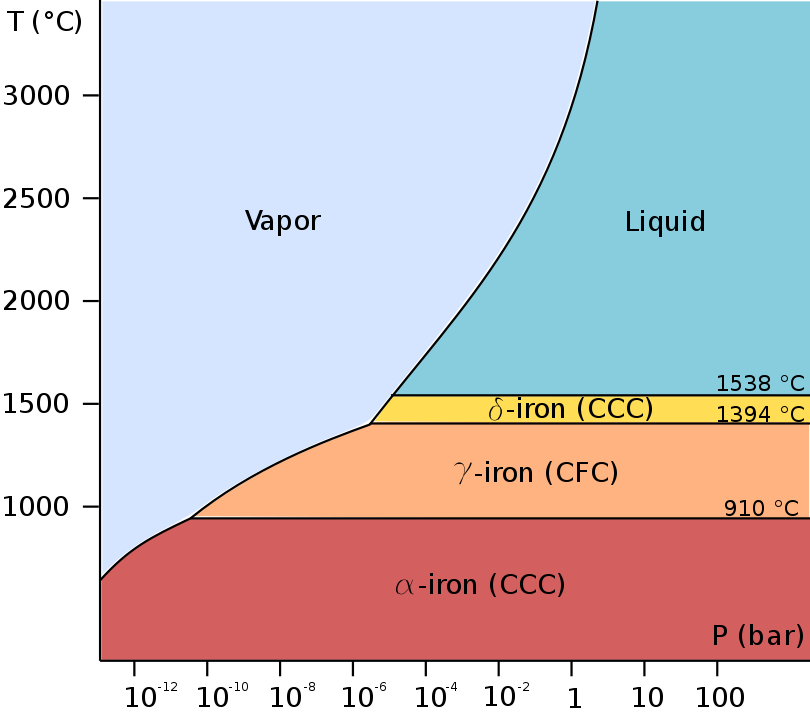

At least four allotropes of iron (differing atom arrangements in the solid) are known, conventionally denoted

α,

γ,

δ, and

ε.

The first three forms are observed at ordinary pressures. As molten iron cools past its freezing point of 1538 °C, it crystallizes into its δ allotrope, which has a

body-centered cubic (bcc)

crystal structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of the ordered arrangement of atoms, ions or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from the intrinsic nature of the constituent particles to form symmetric patterns t ...

. As it cools further to 1394 °C, it changes to its γ-iron allotrope, a

face-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties o ...

(fcc) crystal structure, or

austenite. At 912 °C and below, the crystal structure again becomes the bcc α-iron allotrope.

The physical properties of iron at very high pressures and temperatures have also been studied extensively,

because of their relevance to theories about the cores of the Earth and other planets. Above approximately 10 GPa and temperatures of a few hundred kelvin or less, α-iron changes into another

hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure, which is also known as

ε-iron. The higher-temperature γ-phase also changes into ε-iron, but does so at higher pressure.

Some controversial experimental evidence exists for a stable

β phase at pressures above 50 GPa and temperatures of at least 1500 K. It is supposed to have an

orthorhombic

In crystallography, the orthorhombic crystal system is one of the 7 crystal systems. Orthorhombic lattices result from stretching a cubic lattice along two of its orthogonal pairs by two different factors, resulting in a rectangular prism with ...

or a double hcp structure.

(Confusingly, the term "β-iron" is sometimes also used to refer to α-iron above its Curie point, when it changes from being ferromagnetic to paramagnetic, even though its crystal structure has not changed.

)

The

inner core

Earth's inner core is the innermost geologic layer of planet Earth. It is primarily a solid ball with a radius of about , which is about 20% of Earth's radius or 70% of the Moon's radius.

There are no samples of Earth's core accessible for ...

of the

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surf ...

is generally presumed to consist of an iron-

nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an alloy will retain all the properties of a metal in the resulting material, such as electrical conductivity, ductilit ...

with ε (or β) structure.

Melting and boiling points

The melting and boiling points of iron, along with its

enthalpy of atomization, are lower than those of the earlier 3d elements from

scandium

Scandium is a chemical element with the symbol Sc and atomic number 21. It is a silvery-white metallic d-block element. Historically, it has been classified as a rare-earth element, together with yttrium and the Lanthanides. It was discovere ...

to

chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and h ...

, showing the lessened contribution of the 3d electrons to metallic bonding as they are attracted more and more into the inert core by the nucleus;

[Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1116] however, they are higher than the values for the previous element

manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy u ...

because that element has a half-filled 3d sub-shell and consequently its d-electrons are not easily delocalized. This same trend appears for ruthenium but not osmium.

The melting point of iron is experimentally well defined for pressures less than 50 GPa. For greater pressures, published data (as of 2007) still varies by tens of gigapascals and over a thousand kelvin.

Magnetic properties

Below its

Curie point of , α-iron changes from

paramagnetic to

ferromagnetic

Ferromagnetism is a property of certain materials (such as iron) which results in a large observed magnetic permeability, and in many cases a large magnetic coercivity allowing the material to form a permanent magnet. Ferromagnetic materials ...

: the

spins of the two unpaired electrons in each atom generally align with the spins of its neighbors, creating an overall

magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and t ...

.

This happens because the orbitals of those two electrons (d

''z''2 and d

''x''2 − ''y''2) do not point toward neighboring atoms in the lattice, and therefore are not involved in metallic bonding.

In the absence of an external source of magnetic field, the atoms get spontaneously partitioned into

magnetic domains, about 10 micrometers across,

such that the atoms in each domain have parallel spins, but some domains have other orientations. Thus a macroscopic piece of iron will have a nearly zero overall magnetic field.

Application of an external magnetic field causes the domains that are magnetized in the same general direction to grow at the expense of adjacent ones that point in other directions, reinforcing the external field. This effect is exploited in devices that need to channel magnetic fields to fulfill design function, such as

electrical transformers,

magnetic recording heads, and

electric motor

An electric motor is an electrical machine that converts electrical energy into mechanical energy. Most electric motors operate through the interaction between the motor's magnetic field and electric current in a wire winding to generate forc ...

s. Impurities,

lattice defects, or grain and particle boundaries can "pin" the domains in the new positions, so that the effect persists even after the external field is removed – thus turning the iron object into a (permanent)

magnet

A magnet is a material or object that produces a magnetic field. This magnetic field is invisible but is responsible for the most notable property of a magnet: a force that pulls on other ferromagnetic materials, such as iron, steel, nic ...

.

Similar behavior is exhibited by some iron compounds, such as the

ferrites including the mineral

magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With ...

, a crystalline form of the mixed iron(II,III) oxide (although the atomic-scale mechanism,

ferrimagnetism, is somewhat different). Pieces of magnetite with natural permanent magnetization (

lodestone

Lodestones are naturally magnetized pieces of the mineral magnetite. They are naturally occurring magnets, which can attract iron. The property of magnetism was first discovered in antiquity through lodestones. Pieces of lodestone, suspen ...

s) provided the earliest

compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with ...

es for navigation. Particles of magnetite were extensively used in magnetic recording media such as

core memories

Magnetic-core memory was the predominant form of random-access computer memory for 20 years between about 1955 and 1975.

Such memory is often just called core memory, or, informally, core.

Core memory uses toroids (rings) of a hard magnetic ...

,

magnetic tape

Magnetic tape is a medium for magnetic storage made of a thin, magnetizable coating on a long, narrow strip of plastic film. It was developed in Germany in 1928, based on the earlier magnetic wire recording from Denmark. Devices that use mag ...

s,

floppies, and

disks, until they were replaced by

cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, ...

-based materials.

Isotopes

Iron has four stable

isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers ( mass number ...

s:

54Fe (5.845% of natural iron),

56Fe (91.754%),

57Fe (2.119%) and

58Fe (0.282%). 20-30 artificial isotopes have also been created. Of these stable isotopes, only

57Fe has a

nuclear spin (−). The

nuclide 54Fe theoretically can undergo

double electron capture to

54Cr, but the process has never been observed and only a lower limit on the half-life of 3.1×10

22 years has been established.

Fe is an

extinct radionuclide of long

half-life

Half-life (symbol ) is the time required for a quantity (of substance) to reduce to half of its initial value. The term is commonly used in nuclear physics to describe how quickly unstable atoms undergo radioactive decay or how long stable at ...

(2.6 million years).

It is not found on Earth, but its ultimate decay product is its granddaughter, the stable nuclide

60Ni.

Much of the past work on isotopic composition of iron has focused on the

nucleosynthesis

Nucleosynthesis is the process that creates new atomic nuclei from pre-existing nucleons (protons and neutrons) and nuclei. According to current theories, the first nuclei were formed a few minutes after the Big Bang, through nuclear reactions in ...

of

60Fe through studies of

meteorite

A meteorite is a solid piece of debris from an object, such as a comet, asteroid, or meteoroid, that originates in outer space and survives its passage through the atmosphere to reach the surface of a planet or moon. When the original object en ...

s and ore formation. In the last decade, advances in

mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a '' mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is u ...

have allowed the detection and quantification of minute, naturally occurring variations in the ratios of the

stable isotope

The term stable isotope has a meaning similar to stable nuclide, but is preferably used when speaking of nuclides of a specific element. Hence, the plural form stable isotopes usually refers to isotopes of the same element. The relative abundanc ...

s of iron. Much of this work is driven by the

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surf ...

and

planetary science

Planetary science (or more rarely, planetology) is the scientific study of planets (including Earth), celestial bodies (such as moons, asteroids, comets) and planetary systems (in particular those of the Solar System) and the processes of the ...

communities, although applications to biological and industrial systems are emerging.

In phases of the meteorites ''Semarkona'' and ''Chervony Kut,'' a correlation between the concentration of

60Ni, the

granddaughter of

60Fe, and the abundance of the stable iron isotopes provided evidence for the existence of

60Fe at the time of

formation of the Solar System. Possibly the energy released by the decay of

60Fe, along with that released by

26Al, contributed to the remelting and

differentiation of

asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet of the Solar System#Inner solar system, inner Solar System. Sizes and shapes of asteroids vary significantly, ranging from 1-meter rocks to a dwarf planet almost 1000 km in diameter; they are rocky, metallic o ...

s after their formation 4.6 billion years ago. The abundance of

60Ni present in

extraterrestrial

Extraterrestrial refers to any object or being beyond ( extra-) the planet Earth ( terrestrial). It is derived from the Latin words ''extra'' ("outside", "outwards") and ''terrestris'' ("earthly", "of or relating to the Earth"). It may be abbrevia ...

material may bring further insight into the origin and early history of the

Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

.

The most abundant iron isotope

56Fe is of particular interest to nuclear scientists because it represents the most common endpoint of

nucleosynthesis

Nucleosynthesis is the process that creates new atomic nuclei from pre-existing nucleons (protons and neutrons) and nuclei. According to current theories, the first nuclei were formed a few minutes after the Big Bang, through nuclear reactions in ...

. Since

56Ni (14

alpha particle

Alpha particles, also called alpha rays or alpha radiation, consist of two protons and two neutrons bound together into a particle identical to a helium-4 nucleus. They are generally produced in the process of alpha decay, but may also be pro ...

s) is easily produced from lighter nuclei in the

alpha process in

nuclear reaction

In nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry, a nuclear reaction is a process in which two nuclei, or a nucleus and an external subatomic particle, collide to produce one or more new nuclides. Thus, a nuclear reaction must cause a transformatio ...

s in supernovae (see

silicon burning process), it is the endpoint of fusion chains inside

extremely massive stars, since addition of another alpha particle, resulting in

60Zn, requires a great deal more energy. This

56Ni, which has a half-life of about 6 days, is created in quantity in these stars, but soon decays by two successive positron emissions within supernova decay products in the

supernova remnant gas cloud, first to radioactive

56Co, and then to stable

56Fe. As such, iron is the most abundant element in the core of

red giant

A red giant is a luminous giant star of low or intermediate mass (roughly 0.3–8 solar masses ()) in a late phase of stellar evolution. The outer atmosphere is inflated and tenuous, making the radius large and the surface temperature around or ...

s, and is the most abundant metal in

iron meteorite

Iron meteorites, also known as siderites, or ferrous meteorites, are a type of meteorite that consist overwhelmingly of an iron–nickel alloy known as meteoric iron that usually consists of two mineral phases: kamacite and taenite. Most i ...

s and in the dense metal

cores of planets such as

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surf ...

.

[Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 12] It is also very common in the universe, relative to other stable

metals of approximately the same

atomic weight

Relative atomic mass (symbol: ''A''; sometimes abbreviated RAM or r.a.m.), also known by the deprecated synonym atomic weight, is a dimensionless physical quantity defined as the ratio of the average mass of atoms of a chemical element in a give ...

.

Iron is the sixth most

abundant element in the

universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. A ...

, and the most common

refractory

In materials science, a refractory material or refractory is a material that is resistant to decomposition by heat, pressure, or chemical attack, and retains strength and form at high temperatures. Refractories are polycrystalline, polyphase ...

element.

Although a further tiny energy gain could be extracted by synthesizing

62Ni, which has a marginally higher binding energy than

56Fe, conditions in stars are unsuitable for this process. Element production in supernovas and distribution on Earth greatly favor iron over nickel, and in any case,

56Fe still has a lower mass per nucleon than

62Ni due to its higher fraction of lighter protons. Hence, elements heavier than iron require a

supernova for their formation, involving

rapid neutron capture by starting

56Fe nuclei.

In the

far future of the universe, assuming that

proton decay

In particle physics, proton decay is a hypothetical form of particle decay in which the proton decays into lighter subatomic particles, such as a neutral pion and a positron. The proton decay hypothesis was first formulated by Andrei Sakha ...

does not occur, cold

fusion occurring via

quantum tunnelling

Quantum tunnelling, also known as tunneling ( US) is a quantum mechanical phenomenon whereby a wavefunction can propagate through a potential barrier.

The transmission through the barrier can be finite and depends exponentially on the barrier ...

would cause the light nuclei in ordinary matter to fuse into

56Fe nuclei. Fission and

alpha-particle emission would then make heavy nuclei decay into iron, converting all stellar-mass objects to cold spheres of pure iron.

Origin and occurrence in nature

Cosmogenesis

Iron's abundance in

rocky planets

A terrestrial planet, telluric planet, or rocky planet, is a planet that is composed primarily of silicate rocks or metals. Within the Solar System, the terrestrial planets accepted by the IAU are the inner planets closest to the Sun: Mercury, Ven ...

like Earth is due to its abundant production during the runaway fusion and explosion of type

Ia supernovae, which scatters the iron into space.

Metallic iron

Metallic or

native iron is rarely found on the surface of the Earth because it tends to oxidize. However, both the Earth's

inner and

outer core

Earth's outer core is a fluid layer about thick, composed of mostly iron and nickel that lies above Earth's solid inner core and below its mantle. The outer core begins approximately beneath Earth's surface at the core-mantle boundary and en ...

, that account for 35% of the mass of the whole Earth, are believed to consist largely of an iron alloy, possibly with

nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

. Electric currents in the liquid outer core are believed to be the origin of the

Earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magneti ...

. The other

terrestrial planet

A terrestrial planet, telluric planet, or rocky planet, is a planet that is composed primarily of silicate rocks or metals. Within the Solar System, the terrestrial planets accepted by the IAU are the inner planets closest to the Sun: Mercury, ...

s (

Mercury,

Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

, and

Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin atmos ...

) as well as the

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width ...

are believed to have a metallic core consisting mostly of iron. The

M-type asteroids are also believed to be partly or mostly made of metallic iron alloy.

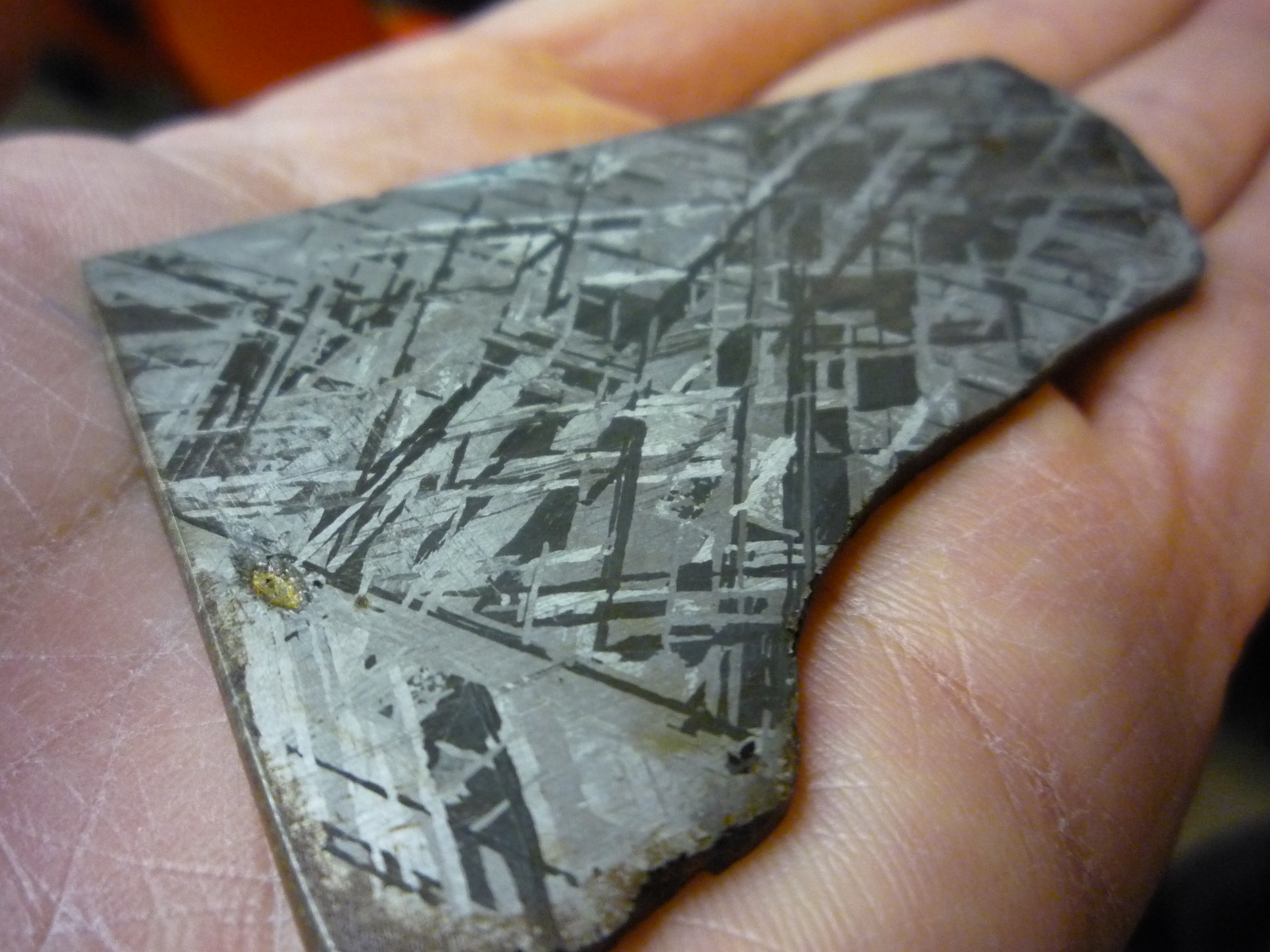

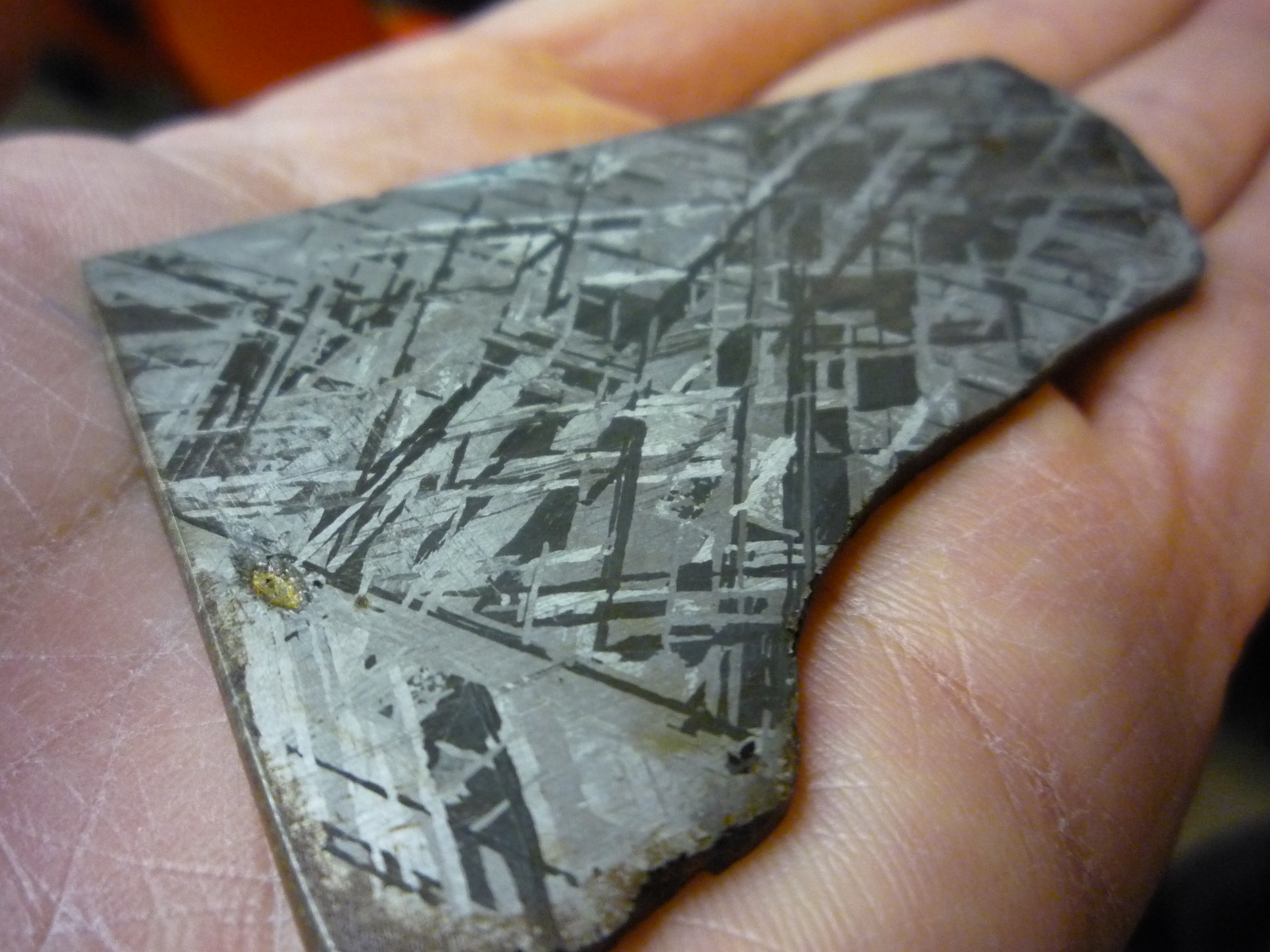

The rare

iron meteorite

Iron meteorites, also known as siderites, or ferrous meteorites, are a type of meteorite that consist overwhelmingly of an iron–nickel alloy known as meteoric iron that usually consists of two mineral phases: kamacite and taenite. Most i ...

s are the main form of natural metallic iron on the Earth's surface. Items made of

cold-worked meteoritic iron have been found in various archaeological sites dating from a time when iron smelting had not yet been developed; and the

Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, ...

in

Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is ...

have been reported to use iron from the

Cape York meteorite for tools and hunting weapons. About 1 in 20

meteorite

A meteorite is a solid piece of debris from an object, such as a comet, asteroid, or meteoroid, that originates in outer space and survives its passage through the atmosphere to reach the surface of a planet or moon. When the original object en ...

s consist of the unique iron-nickel minerals

taenite (35–80% iron) and

kamacite

Kamacite is an alloy of iron and nickel, which is found on Earth only in meteorites. According to the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) it is considered a proper nickel-rich variety of the mineral native iron. The proportion iron:ni ...

(90–95% iron). Native iron is also rarely found in basalts that have formed from magmas that have come into contact with carbon-rich sedimentary rocks, which have reduced the oxygen

fugacity

In chemical thermodynamics, the fugacity of a real gas is an effective partial pressure which replaces the mechanical partial pressure in an accurate computation of the chemical equilibrium constant. It is equal to the pressure of an ideal gas ...

sufficiently for iron to crystallize. This is known as

Telluric iron and is described from a few localities, such as

Disko Island

Disko Island ( kl, Qeqertarsuaq, da, Diskoøen) is a large island in Baffin Bay, off the west coast of Greenland. It has an area of ,[Yakutia

Sakha, officially the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia),, is the largest republic of Russia, located in the Russian Far East, along the Arctic Ocean, with a population of roughly 1 million. Sakha comprises half of the area of its governing Far ...](_blank ...<br></span></div> in West Greenland, <div class=)

in Russia and Bühl in Germany.

Mantle minerals

Ferropericlase , a solid solution of

periclase (MgO) and

wüstite (FeO), makes up about 20% of the volume of the

lower mantle

The lower mantle, historically also known as the mesosphere, represents approximately 56% of Earth's total volume, and is the region from 660 to 2900 km below Earth's surface; between the transition zone and the outer core. The preliminary ...

of the Earth, which makes it the second most abundant mineral phase in that region after

silicate perovskite

Silicate perovskite is either (the magnesium end-member is called bridgmanite) or (calcium silicate known as davemaoite) when arranged in a perovskite structure. Silicate perovskites are not stable at Earth's surface, and mainly exist in the l ...

; it also is the major host for iron in the lower mantle. At the bottom of the

transition zone of the mantle, the reaction γ- transforms

γ-olivine into a mixture of silicate perovskite and ferropericlase and vice versa. In the literature, this mineral phase of the lower mantle is also often called magnesiowüstite.

[Ferropericlase](_blank)

Mindat.org Silicate perovskite

Silicate perovskite is either (the magnesium end-member is called bridgmanite) or (calcium silicate known as davemaoite) when arranged in a perovskite structure. Silicate perovskites are not stable at Earth's surface, and mainly exist in the l ...

may form up to 93% of the lower mantle,

and the magnesium iron form, , is considered to be the most abundant

mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. ...

in the Earth, making up 38% of its volume.

Earth's crust

While iron is the most abundant element on Earth, most of this iron is concentrated in the

inner and

outer cores. The fraction of iron that is in

Earth's crust

Earth's crust is Earth's thin outer shell of rock, referring to less than 1% of Earth's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a division of Earth's layers that includes the crust and the upper part of the mantle. The ...

only amounts to about 5% of the overall mass of the crust and is thus only the fourth most abundant element in that layer (after

oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as we ...

,

silicon

Silicon is a chemical element with the symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic luster, and is a tetravalent metalloid and semiconductor. It is a member of group 14 in the periodic ...

, and

aluminium

Aluminium (aluminum in AmE, American and CanE, Canadian English) is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately o ...

).

Most of the iron in the crust is combined with various other elements to form many

iron minerals. An important class is the

iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of w ...

minerals such as

hematite

Hematite (), also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of ...

(Fe

2O

3),

magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With ...

(Fe

3O

4), and

siderite

Siderite is a mineral composed of iron(II) carbonate (FeCO3). It takes its name from the Greek word σίδηρος ''sideros,'' "iron". It is a valuable iron mineral, since it is 48% iron and contains no sulfur or phosphorus. Zinc, magnesium an ...

(FeCO

3), which are the major

ores of iron. Many

igneous rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or l ...

s also contain the sulfide minerals

pyrrhotite

Pyrrhotite is an iron sulfide mineral with the formula Fe(1-x)S (x = 0 to 0.2). It is a nonstoichiometric variant of FeS, the mineral known as troilite.

Pyrrhotite is also called magnetic pyrite, because the color is similar to pyrite and it ...

and

pentlandite

Pentlandite is an iron–nickel sulfide with the chemical formula . Pentlandite has a narrow variation range in Ni:Fe but it is usually described as having a Ni:Fe of 1:1. It also contains minor cobalt, usually at low levels as a fraction of wei ...

.

[Klein, Cornelis and Cornelius S. Hurlbut, Jr. (1985) ''Manual of Mineralogy,'' Wiley, 20th ed, pp. 278–79 ] During

weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with water, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs '' in situ'' (on site, with little or no movemen ...

, iron tends to leach from sulfide deposits as the sulfate and from silicate deposits as the bicarbonate. Both of these are oxidized in aqueous solution and precipitate in even mildly elevated pH as

iron(III) oxide.

[Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1071]

Large deposits of iron are

banded iron formations, a type of rock consisting of repeated thin layers of iron oxides alternating with bands of iron-poor

shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especia ...

and

chert

Chert () is a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, the mineral form of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Chert is characteristically of biological origin, but may also occur inorganically as a ...

. The banded iron formations were laid down in the time between and .

Materials containing finely ground iron(III) oxides or oxide-hydroxides, such as

ochre

Ochre ( ; , ), or ocher in American English, is a natural clay earth pigment, a mixture of ferric oxide and varying amounts of clay and sand. It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the colours produce ...

, have been used as yellow, red, and brown

pigment

A pigment is a colored material that is completely or nearly insoluble in water. In contrast, dyes are typically soluble, at least at some stage in their use. Generally dyes are often organic compounds whereas pigments are often inorganic comp ...

s since pre-historical times. They contribute as well to the color of various rocks and

clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay part ...

s, including entire geological formations like the

Painted Hills in

Oregon

Oregon () is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of its eastern boundary with Idah ...

and the

Buntsandstein ("colored sandstone", British

Bunter). Through ''Eisensandstein'' (a

jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

'iron sandstone', e.g. from

Donzdorf in Germany) and

Bath stone

Bath Stone is an oolitic limestone comprising granular fragments of calcium carbonate. Originally obtained from the Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines under Combe Down, Somerset, England. Its honey colouring gives the World Heritage City o ...

in the UK, iron compounds are responsible for the yellowish color of many historical buildings and sculptures. The proverbial

red color of the surface of Mars is derived from an iron oxide-rich

regolith

Regolith () is a blanket of unconsolidated, loose, heterogeneous superficial deposits covering solid rock. It includes dust, broken rocks, and other related materials and is present on Earth, the Moon, Mars, some asteroids, and other terrestri ...

.

Significant amounts of iron occur in the iron sulfide mineral

pyrite

The mineral pyrite (), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue giv ...

(FeS

2), but it is difficult to extract iron from it and it is therefore not exploited. In fact, iron is so common that production generally focuses only on ores with very high quantities of it.

According to the

International Resource Panel's

Metal Stocks in Society report

The report Metal Stocks in Society: Scientific Synthesis was the first of six scientific assessments on global metals to be published by the International Resource Panel (IRP) of the United Nations Environment Programme. The IRP provides independe ...

, the global stock of iron in use in society is 2,200 kg per capita. More-developed countries differ in this respect from less-developed countries (7,000–14,000 vs 2,000 kg per capita).

Oceans

Ocean science demonstrated the role of the iron in the ancient seas in both marine biota and climate.

Chemistry and compounds

Iron shows the characteristic chemical properties of the

transition metal

In chemistry, a transition metal (or transition element) is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table (groups 3 to 12), though the elements of group 12 (and less often group 3) are sometimes excluded. They are the elements that c ...

s, namely the ability to form variable oxidation states differing by steps of one and a very large coordination and organometallic chemistry: indeed, it was the discovery of an iron compound,

ferrocene

Ferrocene is an organometallic compound with the formula . The molecule is a complex consisting of two cyclopentadienyl rings bound to a central iron atom. It is an orange solid with a camphor-like odor, that sublimes above room temperature, ...

, that revolutionalized the latter field in the 1950s.

[Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 905] Iron is sometimes considered as a prototype for the entire block of transition metals, due to its abundance and the immense role it has played in the technological progress of humanity.

Its 26 electrons are arranged in the

configuration

Configuration or configurations may refer to:

Computing

* Computer configuration or system configuration

* Configuration file, a software file used to configure the initial settings for a computer program

* Configurator, also known as choice boar ...

rd

64s

2, of which the 3d and 4s electrons are relatively close in energy, and thus it can lose a variable number of electrons and there is no clear point where further ionization becomes unprofitable.

Iron forms compounds mainly in the

oxidation state

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical charge of an atom if all of its bonds to different atoms were fully ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons) of an atom in a chemical compound. ...

s +2 (

iron(II), "ferrous") and +3 (

iron(III), "ferric"). Iron also occurs in

higher oxidation states, e.g. the purple

potassium ferrate (K

2FeO

4), which contains iron in its +6 oxidation state. Although iron(VIII) oxide (FeO

4) has been claimed, the report could not be reproduced and such a species from the removal of all electrons of the element beyond the preceding inert gas configuration (at least with iron in its +8 oxidation state) has been found to be improbable computationally. However, one form of anionic

eO4sup>– with iron in its +7 oxidation state, along with an iron(V)-peroxo isomer, has been detected by infrared spectroscopy at 4 K after cocondensation of laser-ablated Fe atoms with a mixture of O

2/Ar. Iron(IV) is a common intermediate in many biochemical oxidation reactions.

Numerous

organoiron

Organoiron chemistry is the chemistry of iron compounds containing a carbon-to- iron chemical bond. Organoiron compounds are relevant in organic synthesis as reagents such as iron pentacarbonyl, diiron nonacarbonyl and disodium tetracarbonylfe ...

compounds contain formal oxidation states of +1, 0, −1, or even −2. The oxidation states and other bonding properties are often assessed using the technique of

Mössbauer spectroscopy

Mössbauer spectroscopy is a spectroscopic technique based on the Mössbauer effect. This effect, discovered by Rudolf Mössbauer (sometimes written "Moessbauer", German: "Mößbauer") in 1958, consists of the nearly recoil-free emission and abs ...

. Many

mixed valence compounds contain both iron(II) and iron(III) centers, such as

magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With ...

and

Prussian blue

Prussian blue (also known as Berlin blue, Brandenburg blue or, in painting, Parisian or Paris blue) is a dark blue pigment produced by oxidation of ferrous ferrocyanide salts. It has the chemical formula Fe Cyanide.html" ;"title="e(Cyanide">CN ...

().

The latter is used as the traditional "blue" in

blueprint

A blueprint is a reproduction of a technical drawing or engineering drawing using a contact print process on light-sensitive sheets. Introduced by Sir John Herschel in 1842, the process allowed rapid and accurate production of an unlimited numbe ...

s.

Iron is the first of the transition metals that cannot reach its group oxidation state of +8, although its heavier congeners ruthenium and osmium can, with ruthenium having more difficulty than osmium.

Ruthenium exhibits an aqueous cationic chemistry in its low oxidation states similar to that of iron, but osmium does not, favoring high oxidation states in which it forms anionic complexes.

In the second half of the 3d transition series, vertical similarities down the groups compete with the horizontal similarities of iron with its neighbors

cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, ...

and

nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

in the periodic table, which are also ferromagnetic at

room temperature

Colloquially, "room temperature" is a range of air temperatures that most people prefer for indoor settings. It feels comfortable to a person when they are wearing typical indoor clothing. Human comfort can extend beyond this range depending on ...

and share similar chemistry. As such, iron, cobalt, and nickel are sometimes grouped together as the

iron triad.

[Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1070]

Unlike many other metals, iron does not form amalgams with

mercury. As a result, mercury is traded in standardized 76 pound flasks (34 kg) made of iron.

Iron is by far the most reactive element in its group; it is

pyrophoric

A substance is pyrophoric (from grc-gre, πυροφόρος, , 'fire-bearing') if it ignites spontaneously in air at or below (for gases) or within 5 minutes after coming into contact with air (for liquids and solids). Examples are organolith ...

when finely divided and dissolves easily in dilute acids, giving Fe

2+. However, it does not react with concentrated

nitric acid

Nitric acid is the inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but older samples tend to be yellow cast due to decomposition into oxides of nitrogen. Most commercially available ni ...

and other oxidizing acids due to the formation of an impervious oxide layer, which can nevertheless react with

hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid. It is a component of the gastric acid in the dig ...

.

High purity iron, called

electrolytic iron, is considered to be resistant to rust, due to its oxide layer.

Binary compounds

Oxides and hydroxides

Iron forms various

oxide and hydroxide compounds; the most common are

iron(II,III) oxide (Fe

3O

4), and

iron(III) oxide (Fe

2O

3).

Iron(II) oxide

Iron(II) oxide or ferrous oxide is the inorganic compound with the formula FeO. Its mineral form is known as wüstite. One of several iron oxides, it is a black-colored powder that is sometimes confused with rust, the latter of which consists ...

also exists, though it is unstable at room temperature. Despite their names, they are actually all

non-stoichiometric compounds whose compositions may vary.

These oxides are the principal ores for the production of iron (see

bloomery

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called a ''bloom'' ...

and blast furnace). They are also used in the production of

ferrites, useful

magnetic storage media in computers, and pigments. The best known sulfide is

iron pyrite (FeS

2), also known as fool's gold owing to its golden luster.

It is not an iron(IV) compound, but is actually an iron(II)

polysulfide

Polysulfides are a class of chemical compounds containing chains of sulfur atoms. There are two main classes of polysulfides: inorganic and organic. Among the inorganic polysulfides, there are ones which contain anions, which have the general formu ...

containing Fe

2+ and ions in a distorted

sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as salt (although sea salt also contains other chemical salts), is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. With molar masses of 22.99 and 35 ...

structure.

[Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1079]

Halides

The binary ferrous and ferric

halide

In chemistry, a halide (rarely halogenide) is a binary chemical compound, of which one part is a halogen atom and the other part is an element or radical that is less electronegative (or more electropositive) than the halogen, to make a f ...

s are well-known. The ferrous halides typically arise from treating iron metal with the corresponding

hydrohalic acid to give the corresponding hydrated salts.

:Fe + 2 HX → FeX

2 + H

2 (X = F, Cl, Br, I)

Iron reacts with fluorine, chlorine, and bromine to give the corresponding ferric halides,

ferric chloride being the most common.

:2 Fe + 3 X

2 → 2 FeX

3 (X = F, Cl, Br)

Ferric iodide is an exception, being thermodynamically unstable due to the oxidizing power of Fe

3+ and the high reducing power of I

−:

:2 I

− + 2 Fe

3+ → I

2 + 2 Fe

2+ (E

0 = +0.23 V)

Ferric iodide, a black solid, is not stable in ordinary conditions, but can be prepared through the reaction of

iron pentacarbonyl

Iron pentacarbonyl, also known as iron carbonyl, is the compound with formula . Under standard conditions Fe( CO)5 is a free-flowing, straw-colored liquid with a pungent odour. Older samples appear darker. This compound is a common precursor ...

with

iodine

Iodine is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol I and atomic number 53. The heaviest of the stable halogens, it exists as a semi-lustrous, non-metallic solid at standard conditions that melts to form a deep violet liquid at , ...

and

carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide ( chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

in the presence of

hexane and light at the temperature of −20 °C, with oxygen and water excluded.

Complexes of ferric iodide with some soft bases are known to be stable compounds.

Solution chemistry

The

standard reduction potential

Redox potential (also known as oxidation / reduction potential, ''ORP'', ''pe'', ''E_'', or E_) is a measure of the tendency of a chemical species to acquire electrons from or lose electrons to an electrode and thereby be reduced or oxidised respe ...

s in acidic aqueous solution for some common iron ions are given below:

[Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1075–79]

The red-purple tetrahedral

ferrate(VI) anion is such a strong oxidizing agent that it oxidizes nitrogen and ammonia at room temperature, and even water itself in acidic or neutral solutions:

[Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1082–84]

:4 + 10 → 4 + 20 + 3 O

2

The Fe

3+ ion has a large simple cationic chemistry, although the pale-violet hexaquo ion is very readily hydrolyzed when pH increases above 0 as follows:

[Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1088–91]

As pH rises above 0 the above yellow hydrolyzed species form and as it rises above 2–3, reddish-brown hydrous

iron(III) oxide precipitates out of solution. Although Fe

3+ has a d

5 configuration, its absorption spectrum is not like that of Mn

2+ with its weak, spin-forbidden d–d bands, because Fe

3+ has higher positive charge and is more polarizing, lowering the energy of its ligand-to-metal

charge transfer absorptions. Thus, all the above complexes are rather strongly colored, with the single exception of the hexaquo ion – and even that has a spectrum dominated by charge transfer in the near ultraviolet region.

On the other hand, the pale green iron(II) hexaquo ion does not undergo appreciable hydrolysis. Carbon dioxide is not evolved when

carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonat ...

anions are added, which instead results in white

iron(II) carbonate being precipitated out. In excess carbon dioxide this forms the slightly soluble bicarbonate, which occurs commonly in groundwater, but it oxidises quickly in air to form

iron(III) oxide that accounts for the brown deposits present in a sizeable number of streams.

[Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1091–97]

Coordination compounds

Due to its electronic structure, iron has a very large coordination and organometallic chemistry.

Many coordination compounds of iron are known. A typical six-coordinate anion is hexachloroferrate(III),

eCl6sup>3−, found in the mixed

salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quanti ...

tetrakis(methylammonium) hexachloroferrate(III) chloride. Complexes with multiple bidentate ligands have

geometric isomers. For example, the ''trans''-

chlorohydridobis(bis-1,2-(diphenylphosphino)ethane)iron(II) complex is used as a starting material for compounds with the

moiety

Moiety may refer to:

Chemistry

* Moiety (chemistry), a part or functional group of a molecule

** Moiety conservation, conservation of a subgroup in a chemical species

Anthropology

* Moiety (kinship), either of two groups into which a society is ...

. The ferrioxalate ion with three

oxalate ligands (shown at right) displays

helical chirality with its two non-superposable geometries labelled ''Λ'' (lambda) for the left-handed screw axis and ''Δ'' (delta) for the right-handed screw axis, in line with IUPAC conventions.

is used in chemical

actinometry and along with its

sodium salt undergoes

photoreduction applied in old-style photographic processes. The

dihydrate of

iron(II) oxalate has a

polymer

A polymer (; Greek ''poly-'', "many" + '' -mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic and ...

ic structure with co-planar oxalate ions bridging between iron centres with the water of crystallisation located forming the caps of each octahedron, as illustrated below.

Iron(III) complexes are quite similar to those of

chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and h ...

(III) with the exception of iron(III)'s preference for ''O''-donor instead of ''N''-donor ligands. The latter tend to be rather more unstable than iron(II) complexes and often dissociate in water. Many Fe–O complexes show intense colors and are used as tests for

phenol

Phenol (also called carbolic acid) is an aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatile. The molecule consists of a phenyl group () bonded to a hydroxy group (). Mildly acidic, it ...

s or

enol

In organic chemistry, alkenols (shortened to enols) are a type of reactive structure or intermediate in organic chemistry that is represented as an alkene (olefin) with a hydroxyl group attached to one end of the alkene double bond (). The te ...

s. For example, in the

ferric chloride test, used to determine the presence of phenols,

iron(III) chloride reacts with a phenol to form a deep violet complex:

:3 ArOH + FeCl

3 → Fe(OAr)

3 + 3 HCl (Ar =

aryl

In organic chemistry, an aryl is any functional group or substituent derived from an aromatic ring, usually an aromatic hydrocarbon, such as phenyl and naphthyl. "Aryl" is used for the sake of abbreviation or generalization, and "Ar" is used as ...

)

Among the halide and pseudohalide complexes, fluoro complexes of iron(III) are the most stable, with the colorless

eF5(H2O)sup>2− being the most stable in aqueous solution. Chloro complexes are less stable and favor tetrahedral coordination as in

eCl4sup>−;

eBr4sup>− and

eI4sup>− are reduced easily to iron(II).

Thiocyanate is a common test for the presence of iron(III) as it forms the blood-red

e(SCN)(H2O)5sup>2+. Like manganese(II), most iron(III) complexes are high-spin, the exceptions being those with ligands that are high in the

spectrochemical series

A spectrochemical series is a list of ligands ordered by ligand "strength", and a list of metal ions based on oxidation number, group and element. For a metal ion, the ligands modify the difference in energy Δ between the d orbitals, called the ...

such as

cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of ...

. An example of a low-spin iron(III) complex is

e(CN)6sup>3−. The cyanide ligands may easily be detached in

e(CN)6sup>3−, and hence this complex is poisonous, unlike the iron(II) complex

e(CN)6sup>4− found in Prussian blue,

which does not release

hydrogen cyanide

Hydrogen cyanide, sometimes called prussic acid, is a chemical compound with the formula HCN and structure . It is a colorless, extremely poisonous, and flammable liquid that boils slightly above room temperature, at . HCN is produced on a ...

except when dilute acids are added.

Iron shows a great variety of electronic

spin states, including every possible spin quantum number value for a d-block element from 0 (diamagnetic) to (5 unpaired electrons). This value is always half the number of unpaired electrons. Complexes with zero to two unpaired electrons are considered low-spin and those with four or five are considered high-spin.

Iron(II) complexes are less stable than iron(III) complexes but the preference for ''O''-donor ligands is less marked, so that for example is known while is not. They have a tendency to be oxidized to iron(III) but this can be moderated by low pH and the specific ligands used.

Organometallic compounds

Organoiron chemistry

Organoiron chemistry is the chemistry of iron compounds containing a carbon-to-iron chemical bond. Organoiron compounds are relevant in organic synthesis as reagents such as iron pentacarbonyl, diiron nonacarbonyl and disodium tetracarbonylferrate. ...

is the study of

organometallic compounds of iron, where carbon atoms are covalently bound to the metal atom. They are many and varied, including

cyanide complexes,

carbonyl complex

Metal carbonyls are coordination complexes of transition metals with carbon monoxide ligands. Metal carbonyls are useful in organic synthesis and as catalysts or catalyst precursors in homogeneous catalysis, such as hydroformylation and Reppe ch ...

es,

sandwich

A sandwich is a food typically consisting of vegetables, sliced cheese or meat, placed on or between slices of bread, or more generally any dish wherein bread serves as a container or wrapper for another food type. The sandwich began as a po ...

and

half-sandwich compounds.

Prussian blue

Prussian blue (also known as Berlin blue, Brandenburg blue or, in painting, Parisian or Paris blue) is a dark blue pigment produced by oxidation of ferrous ferrocyanide salts. It has the chemical formula Fe Cyanide.html" ;"title="e(Cyanide">CN ...

or "ferric ferrocyanide", Fe

4 e(CN)6sub>3, is an old and well-known iron-cyanide complex, extensively used as pigment and in several other applications. Its formation can be used as a simple wet chemistry test to distinguish between aqueous solutions of Fe

2+ and Fe

3+ as they react (respectively) with

potassium ferricyanide and

potassium ferrocyanide to form Prussian blue.

Another old example of an organoiron compound is

iron pentacarbonyl

Iron pentacarbonyl, also known as iron carbonyl, is the compound with formula . Under standard conditions Fe( CO)5 is a free-flowing, straw-colored liquid with a pungent odour. Older samples appear darker. This compound is a common precursor ...

, Fe(CO)

5, in which a neutral iron atom is bound to the carbon atoms of five

carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide ( chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

molecules. The compound can be used to make

carbonyl iron powder, a highly reactive form of metallic iron.

Thermolysis of iron pentacarbonyl gives

triiron dodecacarbonyl, , a complex with a cluster of three iron atoms at its core. Collman's reagent,

disodium tetracarbonylferrate, is a useful reagent for organic chemistry; it contains iron in the −2 oxidation state.

Cyclopentadienyliron dicarbonyl dimer

Cyclopentadienyliron dicarbonyl dimer is an organometallic compound with the formula ''η''5-C5H5)Fe(CO)2sub>2, often abbreviated to Cp2Fe2(CO)4, pFe(CO)2sub>2 or even Fp2, with the colloquial name "fip dimer". It is a dark reddish-purple crysta ...

contains iron in the rare +1 oxidation state.

A landmark in this field was the discovery in 1951 of the remarkably stable

sandwich compound ferrocene

Ferrocene is an organometallic compound with the formula . The molecule is a complex consisting of two cyclopentadienyl rings bound to a central iron atom. It is an orange solid with a camphor-like odor, that sublimes above room temperature, ...

, by Pauson and Kealy and independently by Miller and colleagues,

whose surprising molecular structure was determined only a year later by

Woodward

A woodward is a warden of a wood. Woodward may also refer to:

Places

;United States

* Woodward, Iowa

* Woodward, Oklahoma

* Woodward, Pennsylvania, a census-designated place

* Woodward Avenue, a street in Tallahassee, Florida, which bisects the ca ...

and

Wilkinson and

Fischer

Fischer is a German occupational surname, meaning fisherman. The name Fischer is the fourth most common German surname. The English version is Fisher.

People with the surname A

* Abraham Fischer (1850–1913) South African public official

* ...

.

Ferrocene is still one of the most important tools and models in this class.

[Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1104]

Iron-centered organometallic species are used as

catalyst

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

s. The

Knölker complex, for example, is a

transfer hydrogenation

In chemistry, transfer hydrogenation is a chemical reaction involving the addition of hydrogen to a compound from a source other than molecular . It is applied in laboratory and industrial organic synthesis to saturate organic compounds and r ...

catalyst for

ketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is a functional group with the structure R–C(=O)–R', where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group –C(=O)– (which contains a carbon-oxygen double bon ...

s.

Industrial uses

The iron compounds produced on the largest scale in industry are

iron(II) sulfate

Iron(II) sulfate (British English: iron(II) sulphate) or ferrous sulfate denotes a range of salts with the formula Fe SO4·''x''H2O. These compounds exist most commonly as the hepta hydrate (''x'' = 7) but several values for x are kno ...

(FeSO

4·7

H2O) and

iron(III) chloride (FeCl

3). The former is one of the most readily available sources of iron(II), but is less stable to aerial oxidation than

Mohr's salt (). Iron(II) compounds tend to be oxidized to iron(III) compounds in the air.

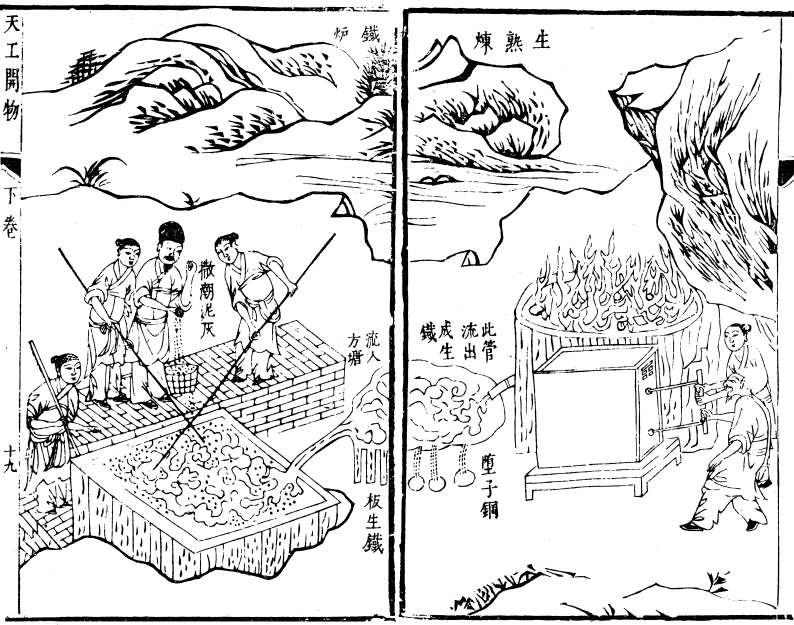

History

Development of iron metallurgy

Iron is one of the elements undoubtedly known to the ancient world. It has been worked, or

wrought, for millennia. However, iron artefacts of great age are much rarer than objects made of gold or silver due to the ease with which iron corrodes. The technology developed slowly, and even after the discovery of smelting it took many centuries for iron to replace bronze as the metal of choice for tools and weapons.

Meteoritic iron

Beads made from

meteoric iron

Meteoric iron, sometimes meteoritic iron, is a native metal and early-universe protoplanetary-disk remnant found in meteorites and made from the elements iron and nickel, mainly in the form of the mineral phases kamacite and taenite. Meteoric i ...

in 3500 BC or earlier were found in

Gerzeh, Egypt by G.A. Wainwright. The beads contain 7.5% nickel, which is a signature of meteoric origin since iron found in the Earth's crust generally has only minuscule nickel impurities.

Meteoric iron was highly regarded due to its origin in the heavens and was often used to forge weapons and tools. For example, a

dagger

A dagger is a fighting knife with a very sharp point and usually two sharp edges, typically designed or capable of being used as a thrusting or stabbing weapon.State v. Martin, 633 S.W.2d 80 (Mo. 1982): This is the dictionary or popular-use de ...

made of meteoric iron was found in the tomb of

Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun (, egy, twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn), Egyptological pronunciation Tutankhamen () (), sometimes referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh who was the last of his royal family to rule during the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty (ruled ...

, containing similar proportions of iron, cobalt, and nickel to a meteorite discovered in the area, deposited by an ancient meteor shower.

Items that were likely made of iron by Egyptians date from 3000 to 2500 BC.

Meteoritic iron is comparably soft and ductile and easily

cold forged but may get brittle when heated because of the

nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

content.

Wrought iron

The first iron production started in the

Middle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, but it took several centuries before iron displaced bronze. Samples of

smelted iron from

Asmar

Asmar ( ps, اسمار) is one of the major cities in northeastern of Kunar province of Afghanistan and is the district center of Bar Kunar district, which is located in the most southern part of the district in a river valley.

History

The nam ...

, Mesopotamia and Tall Chagar Bazaar in northern Syria were made sometime between 3000 and 2700 BC. The

Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-cent ...

established an empire in north-central

Anatolia