Intermembrane Space Of Mitochondria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A mitochondrion (; ) is an

A mitochondrion (; ) is an

Mitochondria may have a number of different shapes.

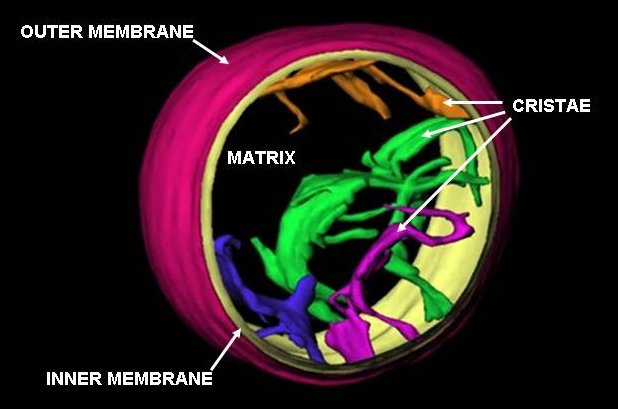

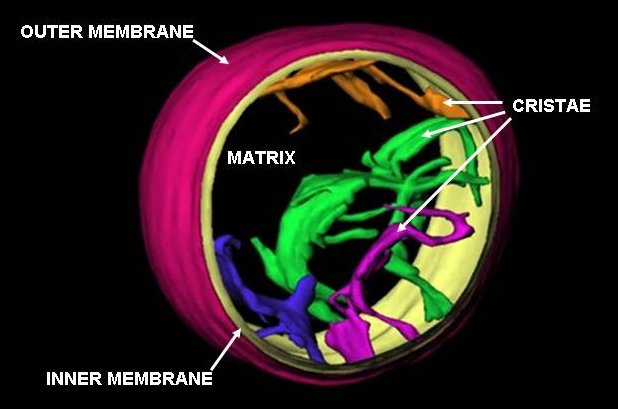

A mitochondrion contains outer and inner membranes composed of

Mitochondria may have a number of different shapes.

A mitochondrion contains outer and inner membranes composed of

The inner mitochondrial membrane is compartmentalized into numerous folds called cristae, which expand the surface area of the inner mitochondrial membrane, enhancing its ability to produce ATP. For typical liver mitochondria, the area of the inner membrane is about five times as large as the outer membrane. This ratio is variable and mitochondria from cells that have a greater demand for ATP, such as muscle cells, contain even more cristae. Mitochondria within the same cell can have substantially different crista-density, with the ones that are required to produce more energy having much more crista-membrane surface. These folds are studded with small round bodies known as F particles or oxysomes.

The inner mitochondrial membrane is compartmentalized into numerous folds called cristae, which expand the surface area of the inner mitochondrial membrane, enhancing its ability to produce ATP. For typical liver mitochondria, the area of the inner membrane is about five times as large as the outer membrane. This ratio is variable and mitochondria from cells that have a greater demand for ATP, such as muscle cells, contain even more cristae. Mitochondria within the same cell can have substantially different crista-density, with the ones that are required to produce more energy having much more crista-membrane surface. These folds are studded with small round bodies known as F particles or oxysomes.

The electrons from NADH and FADH are transferred to oxygen (O) and hydrogen (protons) in several steps via an electron transport chain. NADH and FADH molecules are produced within the matrix via the citric acid cycle and in the cytoplasm by

The electrons from NADH and FADH are transferred to oxygen (O) and hydrogen (protons) in several steps via an electron transport chain. NADH and FADH molecules are produced within the matrix via the citric acid cycle and in the cytoplasm by O2 + 4H+(aq) + 4 Fe^(cyt\,c) -> 2H2O + 4 Fe^(cyt\,c)

releasing a lot of free energy from the reactants without breaking bonds of an organic fuel. The free energy put in to remove an electron from Fe2+ is released at 2 Fe^(cyt\,c) + QH2 -> 2 Fe^(cyt\,c) + Q + 2H+(aq)

The Q + H+(aq) + NADH -> QH2 + NAD+

While the reactions are controlled by an electron transport chain, free electrons are not amongst the reactants or products in the three reactions shown and therefore do not affect the free energy released, which is used to pump

The concentrations of free calcium in the cell can regulate an array of reactions and is important for

The concentrations of free calcium in the cell can regulate an array of reactions and is important for

A few groups of unicellular eukaryotes have only vestigial mitochondria or derived structures: The

A few groups of unicellular eukaryotes have only vestigial mitochondria or derived structures: The

Mitochondria contain their own genome. The human mitochondrial genome is a circular double-stranded DNA molecule of about 16

Mitochondria contain their own genome. The human mitochondrial genome is a circular double-stranded DNA molecule of about 16

While slight variations on the standard genetic code had been predicted earlier, none was discovered until 1979, when researchers studying

Powering the Cell Mitochondria

– XVIVO Scientific Animation

Mitodb.com

– The mitochondrial disease database.

at

Mitochondria Research Portal

at mitochondrial.net

at cytochemistry.net

at

MIP

Mitochondrial Physiology Society

3D structures of proteins from inner mitochondrial membrane

at

3D structures of proteins associated with outer mitochondrial membrane

at

Mitochondrial Protein Partnership

at

MitoMiner – A mitochondrial proteomics database

at

Mitochondrion – Cell Centered Database

at

Video Clip of Rat-liver Mitochondrion from Cryo-electron Tomography

{{Authority control Cellular respiration Endosymbiotic events

A mitochondrion (; ) is an

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

found in the cells of most Eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s, such as animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

s, plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

s and fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

. Mitochondria have a double membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. B ...

structure and use aerobic respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be des ...

to generate adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an organic compound that provides energy to drive many processes in living cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, condensate dissolution, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known forms of ...

(ATP), which is used throughout the cell as a source of chemical energy

Chemical energy is the energy of chemical substances that is released when they undergo a chemical reaction and transform into other substances. Some examples of storage media of chemical energy include batteries, Schmidt-Rohr, K. (2018). "How ...

. They were discovered by Albert von Kölliker in 1857 in the voluntary muscles of insects. The term ''mitochondrion'' was coined by Carl Benda

Carl Benda (30 December 1857 Berlin – 24 May 1932 Turin) was one of the first microbiologists to use a microscope in studying the internal structure of cells. In an 1898 experiment using crystal violet as a specific stain, Benda first beca ...

in 1898. The mitochondrion is popularly nicknamed the "powerhouse of the cell", a phrase coined by Philip Siekevitz

Philip Siekevitz (February 25, 1918 – December 5, 2009) was an American cell biologist who spent most of his career at Rockefeller University. He was involved in early studies of protein synthesis and trafficking, established purification techniq ...

in a 1957 article of the same name.

Some cells in some multicellular organism

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- ...

s lack mitochondria (for example, mature mammalian red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

s). A large number of unicellular organism

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

s, such as microsporidia

Microsporidia are a group of spore-forming unicellular parasites. These spores contain an extrusion apparatus that has a coiled polar tube ending in an anchoring disc at the apical part of the spore. They were once considered protozoans or pr ...

, parabasalid

The parabasalids are a group of flagellated protists within the supergroup Excavata. Most of these eukaryotic organisms form a symbiotic relationship in animals. These include a variety of forms found in the intestines of termites and cockroache ...

s and diplomonad

The diplomonads (Greek for "two units") are a group of flagellates, most of which are parasitic. They include ''Giardia duodenalis'', which causes giardiasis in humans. They are placed among the metamonads, and appear to be particularly close ...

s, have reduced or transformed their mitochondria into other structures. One eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

, ''Monocercomonoides

''Monocercomonoides'' is a genus of flagellate Excavata belonging to the order Oxymonadida. It was established by Bernard V. Travis and was first described as those with "polymastiginid flagellates having three anterior flagella and a trailin ...

'', is known to have completely lost its mitochondria, and one multicellular organism, '' Henneguya salminicola'', is known to have retained mitochondrion-related organelles in association with a complete loss of their mitochondrial genome.

Mitochondria are commonly between 0.75 and 3 μm in crossection, but vary considerably in size and structure. Unless specifically stained, they are not visible. In addition to supplying cellular energy, mitochondria are involved in other tasks, such as signaling

In signal processing, a signal is a function that conveys information about a phenomenon. Any quantity that can vary over space or time can be used as a signal to share messages between observers. The ''IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing'' ...

, cellular differentiation

Cellular differentiation is the process in which a stem cell alters from one type to a differentiated one. Usually, the cell changes to a more specialized type. Differentiation happens multiple times during the development of a multicellular ...

, and cell death

Cell death is the event of a biological cell ceasing to carry out its functions. This may be the result of the natural process of old cells dying and being replaced by new ones, as in programmed cell death, or may result from factors such as dis ...

, as well as maintaining control of the cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and subs ...

and cell growth

Cell growth refers to an increase in the total mass of a cell, including both cytoplasmic, nuclear and organelle volume. Cell growth occurs when the overall rate of cellular biosynthesis (production of biomolecules or anabolism) is greater than ...

. Mitochondrial biogenesis

Mitochondrial biogenesis is the process by which cells increase mitochondrial numbers. It was first described by John Holloszy in the 1960s, when it was discovered that physical endurance training induced higher mitochondrial content levels, leadin ...

is in turn temporally coordinated with these cellular processes. Mitochondria have been implicated in several human disorders and conditions, such as mitochondrial disease

Mitochondrial disease is a group of disorders caused by mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondria are the organelles that generate energy for the cell and are found in every cell of the human body except red blood cells. They convert the energy of ...

s, cardiac dysfunction

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome, a group of signs and symptoms caused by an impairment of the heart's blood pumping function. Symptoms typically include shortness of breath, Fatigue (medical), exc ...

, heart failure and autism

The autism spectrum, often referred to as just autism or in the context of a professional diagnosis autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or autism spectrum condition (ASC), is a neurodevelopmental condition (or conditions) characterized by difficulti ...

.

The number of mitochondria in a cell can vary widely by organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

, tissue, and cell type. A mature red blood cell has no mitochondria, whereas a liver cell can have more than 2000. The mitochondrion is composed of compartments that carry out specialized functions. These compartments or regions include the outer membrane, intermembrane space, inner membrane, cristae, and matrix

Matrix most commonly refers to:

* ''The Matrix'' (franchise), an American media franchise

** ''The Matrix'', a 1999 science-fiction action film

** "The Matrix", a fictional setting, a virtual reality environment, within ''The Matrix'' (franchis ...

.

Although most of a eukaryotic cell's DNA is contained in the cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (pl. nuclei; from Latin or , meaning ''kernel'' or ''seed'') is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryotic cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, h ...

, the mitochondrion has its own genome ("mitogenome") that is substantially similar to bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

l genomes. This finding has led to general acceptance of the endosymbiotic hypothesis - that free-living prokaryotic ancestors of modern mitochondria permanently fused with eukaryotic cells in the distant past, evolving such that modern animals, plants, fungi, and other eukaryotes are able to respire to generate cellular energy.

Structure

phospholipid bilayer

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many vir ...

s and protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s. The two membranes have different properties. Because of this double-membraned organization, there are five distinct parts to a mitochondrion:

# The outer mitochondrial membrane,

# The intermembrane space (the space between the outer and inner membranes),

# The inner mitochondrial membrane,

# The cristae space (formed by infoldings of the inner membrane), and

# The matrix

Matrix most commonly refers to:

* ''The Matrix'' (franchise), an American media franchise

** ''The Matrix'', a 1999 science-fiction action film

** "The Matrix", a fictional setting, a virtual reality environment, within ''The Matrix'' (franchis ...

(space within the inner membrane), which is a fluid.

Mitochondria have folding to increase surface area, which in turn increases ATP (adenosine triphosphate) production.

Mitochondria stripped of their outer membrane are called mitoplast

A mitoplast is a mitochondrion that has been stripped of its outer membrane leaving the inner membrane and matrix intact.

How Mitoplasts Are Most Commonly Created

To begin the process, mitochondria must first be separated from cultured cells ...

s.

Outer membrane

The outer mitochondrial membrane, which encloses the entire organelle, is 60 to 75angstrom

The angstromEntry "angstrom" in the Oxford online dictionary. Retrieved on 2019-03-02 from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/angstrom.Entry "angstrom" in the Merriam-Webster online dictionary. Retrieved on 2019-03-02 from https://www.m ...

s (Å) thick. It has a protein-to-phospholipid ratio similar to that of the cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment ( ...

(about 1:1 by weight). It contains large numbers of integral membrane protein

An integral, or intrinsic, membrane protein (IMP) is a type of membrane protein that is permanently attached to the biological membrane. All ''transmembrane proteins'' are IMPs, but not all IMPs are transmembrane proteins. IMPs comprise a signi ...

s called porins

Porins are beta barrel proteins that cross a cellular membrane and act as a pore, through which molecules can diffuse. Unlike other membrane transport proteins, porins are large enough to allow passive diffusion, i.e., they act as channels tha ...

. A major trafficking protein is the pore-forming voltage-dependent anion channel

Voltage-dependent anion channels, or mitochondrial porins, are a class of porin ion channel located on the outer mitochondrial membrane. There is debate as to whether or not this channel is expressed in the cell surface membrane.

This major pro ...

(VDAC). The VDAC is the primary transporter of nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules wi ...

s, ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conve ...

s and metabolite

In biochemistry, a metabolite is an intermediate or end product of metabolism.

The term is usually used for small molecules. Metabolites have various functions, including fuel, structure, signaling, stimulatory and inhibitory effects on enzymes, c ...

s between the cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells (intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

and the intermembrane space. It is formed as a beta barrel

In protein structures, a beta barrel is a beta sheet composed of tandem repeats that twists and coils to form a closed toroidal structure in which the first strand is bonded to the last strand (hydrogen bond). Beta-strands in many beta-barrels are ...

that spans the outer membrane, similar to that in the gram-negative bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wall ...

l membrane. Larger proteins can enter the mitochondrion if a signaling sequence at their N-terminus

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

binds to a large multisubunit protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

called translocase in the outer membrane, which then actively moves them across the membrane. Mitochondrial pro-proteins

A protein precursor, also called a pro-protein or pro-peptide, is an inactive protein (or peptide) that can be turned into an active form by post-translational modification, such as breaking off a piece of the molecule or adding on another molecule ...

are imported through specialised translocation complexes.

The outer membrane also contains enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s involved in such diverse activities as the elongation of fatty acid

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, fr ...

s, oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

of epinephrine

Adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, is a hormone and medication which is involved in regulating visceral functions (e.g., respiration). It appears as a white microcrystalline granule. Adrenaline is normally produced by the adrenal glands and ...

, and the degradation

Degradation may refer to:

Science

* Degradation (geology), lowering of a fluvial surface by erosion

* Degradation (telecommunications), of an electronic signal

* Biodegradation of organic substances by living organisms

* Environmental degradatio ...

of tryptophan

Tryptophan (symbol Trp or W)

is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Tryptophan contains an α-amino group, an α- carboxylic acid group, and a side chain indole, making it a polar molecule with a non-polar aromatic ...

. These enzymes include monoamine oxidase, rotenone

Rotenone is an odorless, colorless, crystalline isoflavone used as a broad-spectrum insecticide, piscicide, and pesticide. It occurs naturally in the seeds and stems of several plants, such as the jicama vine plant, and the roots of several member ...

-insensitive NADH-cytochrome c-reductase, kynurenine

-Kynurenine is a metabolite of the amino acid -tryptophan used in the production of niacin.

Kynurenine is synthesized by the enzyme tryptophan dioxygenase, which is made primarily but not exclusively in the liver, and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase ...

hydroxylase

In chemistry, hydroxylation can refer to:

*(i) most commonly, hydroxylation describes a chemical process that introduces a hydroxyl group () into an organic compound.

*(ii) the ''degree of hydroxylation'' refers to the number of OH groups in ...

and fatty acid Co-A ligase

In biochemistry, a ligase is an enzyme that can catalyze the joining (ligation) of two large molecules by forming a new chemical bond. This is typically via hydrolysis of a small pendant chemical group on one of the larger molecules or the enzym ...

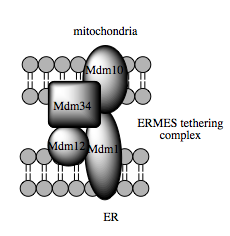

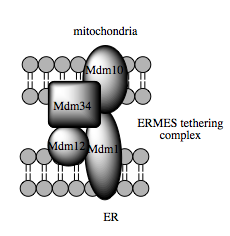

. Disruption of the outer membrane permits proteins in the intermembrane space to leak into the cytosol, leading to cell death. The outer mitochondrial membrane can associate with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, in a structure called MAM (mitochondria-associated ER-membrane). This is important in the ER-mitochondria calcium signaling and is involved in the transfer of lipids between the ER and mitochondria. Outside the outer membrane are small (diameter: 60 Å) particles named sub-units of Parson.

Intermembrane space

The mitochondrial intermembrane space is the space between the outer membrane and the inner membrane. It is also known as perimitochondrial space. Because the outer membrane is freely permeable to small molecules, the concentrations of small molecules, such as ions and sugars, in the intermembrane space is the same as in thecytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells (intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

. However, large proteins must have a specific signaling sequence to be transported across the outer membrane, so the protein composition of this space is different from the protein composition of the cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells (intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

. One protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

that is localized to the intermembrane space in this way is cytochrome c

The cytochrome complex, or cyt ''c'', is a small hemeprotein found loosely associated with the inner membrane of the mitochondrion. It belongs to the cytochrome c family of proteins and plays a major role in cell apoptosis. Cytochrome c is hig ...

.

Inner membrane

The inner mitochondrial membrane contains proteins with three types of functions: # Those that perform theelectron transport chain

An electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and other molecules that transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions (both reduction and oxidation occurring simultaneously) and couples th ...

redox

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate (chemistry), substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of Electron, electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction ...

reactions

# ATP synthase

ATP synthase is a protein that catalyzes the formation of the energy storage molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP) using adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). It is classified under ligases as it changes ADP by the formation ...

, which generates ATP in the matrix

# Specific transport proteins

A transport protein (variously referred to as a transmembrane pump, transporter, escort protein, acid transport protein, cation transport protein, or anion transport protein) is a protein that serves the function of moving other materials within ...

that regulate metabolite

In biochemistry, a metabolite is an intermediate or end product of metabolism.

The term is usually used for small molecules. Metabolites have various functions, including fuel, structure, signaling, stimulatory and inhibitory effects on enzymes, c ...

passage into and out of the mitochondrial matrix

In the mitochondrion, the matrix is the space within the inner membrane. The word "matrix" stems from the fact that this space is viscous, compared to the relatively aqueous cytoplasm. The mitochondrial matrix contains the mitochondrial DNA, ribo ...

It contains more than 151 different polypeptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

A p ...

s, and has a very high protein-to-phospholipid ratio (more than 3:1 by weight, which is about 1 protein for 15 phospholipids). The inner membrane is home to around 1/5 of the total protein in a mitochondrion. Additionally, the inner membrane is rich in an unusual phospholipid, cardiolipin. This phospholipid was originally discovered in cow

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ma ...

hearts in 1942, and is usually characteristic of mitochondrial and bacterial plasma membranes. Cardiolipin contains four fatty acids rather than two, and may help to make the inner membrane impermeable, and its disruption can lead to multiple clinical disorders including neurological disorders and cancer. Unlike the outer membrane, the inner membrane does not contain porins, and is highly impermeable to all molecules. Almost all ions and molecules require special membrane transporters to enter or exit the matrix. Proteins are ferried into the matrix via the translocase of the inner membrane

The translocase of the inner membrane (TIM) is a complex of proteins found in the inner mitochondrial membrane of the mitochondria. Components of the TIM complex facilitate the translocation of proteins across the inner membrane and into the mitoc ...

(TIM) complex or via OXA1L

Mitochondrial inner membrane protein OXA1L is a protein that in humans is encoded by the OXA1L gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''ge ...

. In addition, there is a membrane potential across the inner membrane, formed by the action of the enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s of the electron transport chain

An electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and other molecules that transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions (both reduction and oxidation occurring simultaneously) and couples th ...

. Inner membrane fusion

Fusion, or synthesis, is the process of combining two or more distinct entities into a new whole.

Fusion may also refer to:

Science and technology Physics

*Nuclear fusion, multiple atomic nuclei combining to form one or more different atomic nucl ...

is mediated by the inner membrane protein OPA1

Dynamin-like 120 kDa protein, mitochondrial is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''OPA1'' gene. This protein regulates mitochondrial fusion and cristae structure in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) and contributes to ATP synthesis an ...

.

Cristae

The inner mitochondrial membrane is compartmentalized into numerous folds called cristae, which expand the surface area of the inner mitochondrial membrane, enhancing its ability to produce ATP. For typical liver mitochondria, the area of the inner membrane is about five times as large as the outer membrane. This ratio is variable and mitochondria from cells that have a greater demand for ATP, such as muscle cells, contain even more cristae. Mitochondria within the same cell can have substantially different crista-density, with the ones that are required to produce more energy having much more crista-membrane surface. These folds are studded with small round bodies known as F particles or oxysomes.

The inner mitochondrial membrane is compartmentalized into numerous folds called cristae, which expand the surface area of the inner mitochondrial membrane, enhancing its ability to produce ATP. For typical liver mitochondria, the area of the inner membrane is about five times as large as the outer membrane. This ratio is variable and mitochondria from cells that have a greater demand for ATP, such as muscle cells, contain even more cristae. Mitochondria within the same cell can have substantially different crista-density, with the ones that are required to produce more energy having much more crista-membrane surface. These folds are studded with small round bodies known as F particles or oxysomes.

Matrix

The matrix is the space enclosed by the inner membrane. It contains about 2/3 of the total proteins in a mitochondrion. The matrix is important in the production of ATP with the aid of the ATP synthase contained in the inner membrane. The matrix contains a highly concentrated mixture of hundreds of enzymes, special mitochondrialribosomes

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to f ...

, tRNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino ac ...

, and several copies of the mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

. Of the enzymes, the major functions include oxidation of pyruvate and fatty acids

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, f ...

, and the citric acid cycle

The citric acid cycle (CAC)—also known as the Krebs cycle or the TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of chemical reactions to release stored energy through the oxidation of acetyl-CoA derived from carbohydrates, fats, and proteins ...

. The DNA molecules are packaged into nucleoids by proteins, one of which is TFAM

Mitochondrial transcription factor A, abbreviated as ''TFAM'' or ''mtTFA'', is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''TFAM'' gene.

Function

This gene encodes a mitochondrial transcription factor that is a key activator of mitochondrial ...

.

Function

The most prominent roles of mitochondria are to produce the energy currency of the cell, ATP (i.e., phosphorylation of ADP), through respiration and to regulate cellularmetabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

. The central set of reactions involved in ATP production are collectively known as the citric acid cycle

The citric acid cycle (CAC)—also known as the Krebs cycle or the TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of chemical reactions to release stored energy through the oxidation of acetyl-CoA derived from carbohydrates, fats, and proteins ...

, or the Krebs cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation

Oxidative phosphorylation (UK , US ) or electron transport-linked phosphorylation or terminal oxidation is the metabolic pathway in which cells use enzymes to oxidize nutrients, thereby releasing chemical energy in order to produce adenosine tri ...

. However, the mitochondrion has many other functions in addition to the production of ATP.

Energy conversion

A dominant role for the mitochondria is the production of ATP, as reflected by the large number of proteins in the inner membrane for this task. This is done by oxidizing the major products ofglucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using ...

: pyruvate, and NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a coenzyme central to metabolism. Found in all living cells, NAD is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups. One nucleotide contains an aden ...

, which are produced in the cytosol. This type of cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be des ...

, known as aerobic respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be des ...

, is dependent on the presence of oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

. When oxygen is limited, the glycolytic products will be metabolized by anaerobic fermentation

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food p ...

, a process that is independent of the mitochondria. The production of ATP from glucose and oxygen has an approximately 13-times higher yield during aerobic respiration compared to fermentation. Plant mitochondria can also produce a limited amount of ATP either by breaking the sugar produced during photosynthesis or without oxygen by using the alternate substrate nitrite

The nitrite polyatomic ion, ion has the chemical formula . Nitrite (mostly sodium nitrite) is widely used throughout chemical and pharmaceutical industries. The nitrite anion is a pervasive intermediate in the nitrogen cycle in nature. The name ...

. ATP crosses out through the inner membrane with the help of a specific protein, and across the outer membrane via porins

Porins are beta barrel proteins that cross a cellular membrane and act as a pore, through which molecules can diffuse. Unlike other membrane transport proteins, porins are large enough to allow passive diffusion, i.e., they act as channels tha ...

. ADP returns via the same route.

Pyruvate and the citric acid cycle

Pyruvate molecules produced byglycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvate (). The free energy released in this process is used to form the high-energy molecules adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH ...

are actively transported across the inner mitochondrial membrane, and into the matrix where they can either be oxidized

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a ...

and combined with coenzyme A

Coenzyme A (CoA, SHCoA, CoASH) is a coenzyme, notable for its role in the synthesis and oxidation of fatty acids, and the oxidation of pyruvate in the citric acid cycle. All genomes sequenced to date encode enzymes that use coenzyme A as a subs ...

to form CO, acetyl-CoA

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidized for ...

, and NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a coenzyme central to metabolism. Found in all living cells, NAD is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups. One nucleotide contains an aden ...

, or they can be carboxylated

Carboxylation is a chemical reaction in which a carboxylic acid is produced by treating a substrate with carbon dioxide. The opposite reaction is decarboxylation. In chemistry, the term carbonation is sometimes used synonymously with carboxylat ...

(by pyruvate carboxylase

Pyruvate carboxylase (PC) encoded by the gene PC is an enzyme () of the ligase class that catalyzes (depending on the species) the physiologically irreversible carboxylation of pyruvate to form oxaloacetate (OAA).

Image:Pyruvic-acid-2D-sk ...

) to form oxaloacetate. This latter reaction "fills up" the amount of oxaloacetate in the citric acid cycle and is therefore an anaplerotic reaction, increasing the cycle's capacity to metabolize acetyl-CoA when the tissue's energy needs (e.g., in muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of muscl ...

) are suddenly increased by activity.

In the citric acid cycle, all the intermediates (e.g. citrate

Citric acid is an organic compound with the chemical formula HOC(CO2H)(CH2CO2H)2. It is a colorless weak organic acid. It occurs naturally in citrus fruits. In biochemistry, it is an intermediate in the citric acid cycle, which occurs in t ...

, iso-citrate, alpha-ketoglutarate, succinate, fumarate

Fumaric acid is an organic compound with the formula HO2CCH=CHCO2H. A white solid, fumaric acid occurs widely in nature. It has a fruit-like taste and has been used as a food additive. Its E number is E297.

The salts and esters are known as f ...

, malate

Malic acid is an organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a dicarboxylic acid that is made by all living organisms, contributes to the sour taste of fruits, and is used as a food additive. Malic acid has two stereoisomeric forms (L ...

and oxaloacetate) are regenerated during each turn of the cycle. Adding more of any of these intermediates to the mitochondrion therefore means that the additional amount is retained within the cycle, increasing all the other intermediates as one is converted into the other. Hence, the addition of any one of them to the cycle has an anaplerotic effect, and its removal has a cataplerotic effect. These anaplerotic and cataplerotic reactions will, during the course of the cycle, increase or decrease the amount of oxaloacetate available to combine with acetyl-CoA to form citric acid. This in turn increases or decreases the rate of ATP production by the mitochondrion, and thus the availability of ATP to the cell.

Acetyl-CoA, on the other hand, derived from pyruvate oxidation, or from the beta-oxidation

In biochemistry and metabolism, beta-oxidation is the catabolic process by which fatty acid molecules are broken down in the cytosol in prokaryotes and in the mitochondria in eukaryotes to generate acetyl-CoA, which enters the citric acid cycle, ...

of fatty acids

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, f ...

, is the only fuel to enter the citric acid cycle. With each turn of the cycle one molecule of acetyl-CoA is consumed for every molecule of oxaloacetate present in the mitochondrial matrix, and is never regenerated. It is the oxidation of the acetate portion of acetyl-CoA that produces CO and water, with the energy thus released captured in the form of ATP.

In the liver, the carboxylation

Carboxylation is a chemical reaction in which a carboxylic acid is produced by treating a substrate with carbon dioxide. The opposite reaction is decarboxylation. In chemistry, the term carbonation is sometimes used synonymously with carboxylatio ...

of cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells (intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

ic pyruvate into intra-mitochondrial oxaloacetate is an early step in the gluconeogenic pathway, which converts lactate and de-aminated alanine

Alanine (symbol Ala or A), or α-alanine, is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an amine group and a carboxylic acid group, both attached to the central carbon atom which also carries a methyl group side c ...

into glucose, under the influence of high levels of glucagon

Glucagon is a peptide hormone, produced by alpha cells of the pancreas. It raises concentration of glucose and fatty acids in the bloodstream, and is considered to be the main catabolic hormone of the body. It is also used as a Glucagon (medicati ...

and/or epinephrine

Adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, is a hormone and medication which is involved in regulating visceral functions (e.g., respiration). It appears as a white microcrystalline granule. Adrenaline is normally produced by the adrenal glands and ...

in the blood. Here, the addition of oxaloacetate to the mitochondrion does not have a net anaplerotic effect, as another citric acid cycle intermediate (malate) is immediately removed from the mitochondrion to be converted to cytosolic oxaloacetate, and ultimately to glucose, in a process that is almost the reverse of glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvate (). The free energy released in this process is used to form the high-energy molecules adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH ...

.

The enzymes of the citric acid cycle are located in the mitochondrial matrix, with the exception of succinate dehydrogenase

Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) or succinate-coenzyme Q reductase (SQR) or respiratory complex II is an enzyme complex, found in many bacterial cells and in the inner mitochondrial membrane of eukaryotes. It is the only enzyme that participates i ...

, which is bound to the inner mitochondrial membrane as part of Complex II. The citric acid cycle oxidizes the acetyl-CoA to carbon dioxide, and, in the process, produces reduced cofactors (three molecules of NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a coenzyme central to metabolism. Found in all living cells, NAD is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups. One nucleotide contains an aden ...

and one molecule of FADH) that are a source of electrons for the electron transport chain

An electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and other molecules that transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions (both reduction and oxidation occurring simultaneously) and couples th ...

, and a molecule of GTP (which is readily converted to an ATP).

O and NADH: Energy-releasing reactions

glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvate (). The free energy released in this process is used to form the high-energy molecules adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH ...

. Reducing equivalent

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

s from the cytoplasm can be imported via the malate-aspartate shuttle

The malate-aspartate shuttle (sometimes simply the malate shuttle) is a biochemical system for translocating electrons produced during glycolysis across the semipermeable inner membrane of the mitochondrion for oxidative phosphorylation in eukaryo ...

system of antiporter

An antiporter (also called exchanger or counter-transporter) is a cotransporter and integral membrane protein involved in secondary active transport of two or more different molecules or ions across a phospholipid membrane such as the plasma memb ...

proteins or fed into the electron transport chain using a glycerol phosphate shuttle

The glycerol-3-phosphate shuttle is a mechanism that regenerates NAD+ from NADH, a by-product of glycolysis. The shuttle consists of the sequential activity of two proteins: GPD1 which transfers an electron pair from NADH to dihydroxyacetone phosp ...

.

The major energy-releasing reactions Voet, D.; Voet, J. G. (2004). ''Biochemistry'', 3rd edition, p. 804, Wiley. Atkins, P.; de Paula, J. (2006) "Physical Chemistry", 8th ed.; pp. 225-229, Freeman: New York, 2006. that make the mitochondrion the "powerhouse of the cell" occur at protein complexes I, III and IV in the inner mitochondrial membrane (NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone)

Respiratory complex I, (also known as NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase, Type I NADH dehydrogenase and mitochondrial complex I) is the first large protein complex of the respiratory chains of many organisms from bacteria to humans. It catalyzes the ...

, cytochrome c reductase, and cytochrome c oxidase

The enzyme cytochrome c oxidase or Complex IV, (was , now reclassified as a translocasEC 7.1.1.9 is a large transmembrane protein complex found in bacteria, archaea, and mitochondria of eukaryotes.

It is the last enzyme in the respiratory elect ...

). At complex IV

The enzyme cytochrome c oxidase or Complex IV, (was , now reclassified as a translocasEC 7.1.1.9 is a large transmembrane protein complex found in bacteria, archaea, and mitochondria of eukaryotes.

It is the last enzyme in the respiratory electr ...

, O2 reacts with the reduced form of iron in cytochrome c

The cytochrome complex, or cyt ''c'', is a small hemeprotein found loosely associated with the inner membrane of the mitochondrion. It belongs to the cytochrome c family of proteins and plays a major role in cell apoptosis. Cytochrome c is hig ...

:

complex III

Complex commonly refers to:

* Complexity, the behaviour of a system whose components interact in multiple ways so possible interactions are difficult to describe

** Complex system, a system composed of many components which may interact with each ...

when Fe3+ of cytochrome c reacts to oxidize ubiquinol

A ubiquinol is an electron-rich (reduced) form of coenzyme Q (ubiquinone). The term most often refers to ubiquinol-10, with a 10-unit tail most commonly found in humans.

The natural ubiquinol form of coenzyme Q is 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-poly ...

(QH2):

ubiquinone

Coenzyme Q, also known as ubiquinone and marketed as CoQ10, is a coenzyme family that is ubiquitous in animals and most bacteria (hence the name ubiquinone). In humans, the most common form is coenzyme Q10 or ubiquinone-10.

It is a 1,4-benzoq ...

(Q) generated reacts, in complex I

Respiratory complex I, (also known as NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase, Type I NADH dehydrogenase and mitochondrial complex I) is the first large protein complex of the Electron transport chain, respiratory chains of many organisms from bacteria to ...

, with NADH:

protons

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' elementary charge. Its mass is slightly less than that of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton–electron mass ...

(H) into the intermembrane space. This process is efficient, but a small percentage of electrons may prematurely reduce oxygen, forming reactive oxygen species

In chemistry, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (). Examples of ROS include peroxides, superoxide, hydroxyl radical, singlet oxygen, and alpha-oxygen.

The reduction of molecular oxygen () p ...

such as superoxide

In chemistry, a superoxide is a compound that contains the superoxide ion, which has the chemical formula . The systematic name of the anion is dioxide(1−). The reactive oxygen ion superoxide is particularly important as the product of the ...

. This can cause oxidative stress

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily Detoxification, detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances ...

in the mitochondria and may contribute to the decline in mitochondrial function associated with aging.

As the proton concentration increases in the intermembrane space, a strong electrochemical gradient

An electrochemical gradient is a gradient of electrochemical potential, usually for an ion that can move across a membrane. The gradient consists of two parts, the chemical gradient, or difference in solute concentration across a membrane, and th ...

is established across the inner membrane. The protons can return to the matrix through the ATP synthase

ATP synthase is a protein that catalyzes the formation of the energy storage molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP) using adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). It is classified under ligases as it changes ADP by the formation ...

complex, and their potential energy is used to synthesize ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate (P). This process is called chemiosmosis

Chemiosmosis is the movement of ions across a semipermeable membrane bound structure, down their electrochemical gradient. An important example is the formation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by the movement of hydrogen ions (H+) across a membra ...

, and was first described by Peter Mitchell Peter or Pete Mitchell may refer to:

Media

*Pete Mitchell (broadcaster) (1958–2020), British broadcaster

*Peter Mitchell (newsreader) (born 1960), Australian journalist

*Peter Mitchell (photographer) (born 1943), British documentary photographer

...

, who was awarded the 1978 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

for his work. Later, part of the 1997 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Paul D. Boyer

Paul Delos Boyer (July 31, 1918 – June 2, 2018) was an American biochemist, analytical chemist, and a professor of chemistry at University of California Los Angeles (UCLA). He shared the 1997 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for research on the " enzy ...

and John E. Walker

Sir John Ernest Walker One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from the royalsociety.org website where: (born 7 January 1941) is a British chemist who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1997. Walker is Emeritus Director an ...

for their clarification of the working mechanism of ATP synthase.

Heat production

Under certain conditions, protons can re-enter the mitochondrial matrix without contributing to ATP synthesis. This process is known as ''proton leak'' ormitochondrial uncoupling An uncoupler or uncoupling agent is a molecule that disrupts oxidative phosphorylation in prokaryotes and mitochondria or photophosphorylation in chloroplasts and cyanobacteria by dissociating the reactions of ATP synthesis from the electron tr ...

and is due to the facilitated diffusion

Facilitated diffusion (also known as facilitated transport or passive-mediated transport) is the process of spontaneous passive transport (as opposed to active transport) of molecules or ions across a biological membrane via specific transmembra ...

of protons into the matrix. The process results in the unharnessed potential energy of the proton electrochemical

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between electrical potential difference, as a measurable and quantitative phenomenon, and identifiable chemical change, with the potential difference as an outc ...

gradient being released as heat. The process is mediated by a proton channel called thermogenin

Thermogenin (called uncoupling protein by its discoverers and now known as uncoupling protein 1, or UCP1) is a mitochondrial carrier protein found in brown adipose tissue (BAT). It is used to generate heat by non-shivering thermogenesis, and ma ...

, or UCP1

Thermogenin (called uncoupling protein by its discoverers and now known as uncoupling protein 1, or UCP1) is a mitochondrial carrier protein found in brown adipose tissue (BAT). It is used to generate heat by non-shivering thermogenesis, and mak ...

. Thermogenin is primarily found in brown adipose tissue

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) or brown fat makes up the adipose organ together with white adipose tissue (or white fat). Brown adipose tissue is found in almost all mammals.

Classification of brown fat refers to two distinct cell populations with si ...

, or brown fat, and is responsible for non-shivering thermogenesis. Brown adipose tissue is found in mammals, and is at its highest levels in early life and in hibernating animals. In humans, brown adipose tissue is present at birth and decreases with age.

Storage of calcium ions

The concentrations of free calcium in the cell can regulate an array of reactions and is important for

The concentrations of free calcium in the cell can regulate an array of reactions and is important for signal transduction

Signal transduction is the process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a series of molecular events, most commonly protein phosphorylation catalyzed by protein kinases, which ultimately results in a cellula ...

in the cell. Mitochondria can transiently store calcium, a contributing process for the cell's homeostasis of calcium.

Their ability to rapidly take in calcium for later release makes them good "cytosolic buffers" for calcium. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the most significant storage site of calcium, and there is a significant interplay between the mitochondrion and ER with regard to calcium. The calcium is taken up into the matrix

Matrix most commonly refers to:

* ''The Matrix'' (franchise), an American media franchise

** ''The Matrix'', a 1999 science-fiction action film

** "The Matrix", a fictional setting, a virtual reality environment, within ''The Matrix'' (franchis ...

by the mitochondrial calcium uniporter

The mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) is a transmembrane protein that allows the passage of calcium ions from a cell's cytosol into mitochondria. Its activity is regulated by MICU1 and MICU2, which together with the MCU make up the mitocho ...

on the inner mitochondrial membrane

The inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) is the mitochondrial membrane which separates the mitochondrial matrix from the intermembrane space.

Structure

The structure of the inner mitochondrial membrane is extensively folded and compartmentalized. ...

. It is primarily driven by the mitochondrial membrane potential. Release of this calcium back into the cell's interior can occur via a sodium-calcium exchange protein or via "calcium-induced-calcium-release" pathways. This can initiate calcium spikes or calcium waves with large changes in the membrane potential. These can activate a series of second messenger system

Second messengers are intracellular signaling molecules released by the cell in response to exposure to extracellular signaling molecules—the first messengers. (Intercellular signals, a non-local form or cell signaling, encompassing both first me ...

proteins that can coordinate processes such as neurotransmitter release

Exocytosis () is a form of active transport and bulk transport in which a cell transports molecules (e.g., neurotransmitters and proteins) out of the cell ('' exo-'' + ''cytosis''). As an active transport mechanism, exocytosis requires the use ...

in nerve cells and release of hormone

A hormone (from the Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs by complex biological processes to regulate physiology and behavior. Hormones are required ...

s in endocrine cells.

Ca influx to the mitochondrial matrix has recently been implicated as a mechanism to regulate respiratory bioenergetics

Bioenergetics is a field in biochemistry and cell biology that concerns energy flow through living systems. This is an active area of biological research that includes the study of the transformation of energy in living organisms and the study of ...

by allowing the electrochemical potential across the membrane to transiently "pulse" from ΔΨ-dominated to pH-dominated, facilitating a reduction of oxidative stress

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily Detoxification, detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances ...

. In neurons, concomitant increases in cytosolic and mitochondrial calcium act to synchronize neuronal activity with mitochondrial energy metabolism. Mitochondrial matrix calcium levels can reach the tens of micromolar levels, which is necessary for the activation of isocitrate dehydrogenase

Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) () and () is an enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate, producing alpha-ketoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) and CO2. This is a two-step process, which involves oxidation of isocitrate (a s ...

, one of the key regulatory enzymes of the Krebs cycle

The citric acid cycle (CAC)—also known as the Krebs cycle or the TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of chemical reactions to release stored energy through the oxidation of acetyl-CoA derived from carbohydrates, fats, and protein ...

.

Cellular proliferation regulation

The relationship between cellular proliferation and mitochondria has been investigated. Tumor cells require ample ATP to synthesize bioactive compounds such aslipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include ...

s, protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s, and nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules wi ...

s for rapid proliferation. The majority of ATP in tumor cells is generated via the oxidative phosphorylation

Oxidative phosphorylation (UK , US ) or electron transport-linked phosphorylation or terminal oxidation is the metabolic pathway in which cells use enzymes to oxidize nutrients, thereby releasing chemical energy in order to produce adenosine tri ...

pathway (OxPhos). Interference with OxPhos cause cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and subs ...

arrest suggesting that mitochondria play a role in cell proliferation. Mitochondrial ATP production is also vital for cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell (biology), cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukar ...

and differentiation in infection in addition to basic functions in the cell including the regulation of cell volume, solute concentration

In chemistry, concentration is the abundance of a constituent divided by the total volume of a mixture. Several types of mathematical description can be distinguished: '' mass concentration'', ''molar concentration'', ''number concentration'', an ...

, and cellular architecture. ATP levels differ at various stages of the cell cycle suggesting that there is a relationship between the abundance of ATP and the cell's ability to enter a new cell cycle. ATP's role in the basic functions of the cell make the cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and subs ...

sensitive to changes in the availability of mitochondrial derived ATP. The variation in ATP levels at different stages of the cell cycle support the hypothesis that mitochondria play an important role in cell cycle regulation. Although the specific mechanisms between mitochondria and the cell cycle regulation is not well understood, studies have shown that low energy cell cycle checkpoints monitor the energy capability before committing to another round of cell division.

Additional functions

Mitochondria play a central role in many othermetabolic

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

tasks, such as:

* Signaling through mitochondrial reactive oxygen species

In chemistry, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (). Examples of ROS include peroxides, superoxide, hydroxyl radical, singlet oxygen, and alpha-oxygen.

The reduction of molecular oxygen () p ...

* Regulation of the membrane potential

* Apoptosis

Apoptosis (from grc, ἀπόπτωσις, apóptōsis, 'falling off') is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms. Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (morphology) and death. These changes incl ...

-programmed cell death

* Calcium signaling (including calcium-evoked apoptosis)

* Regulation of cellular metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

* Certain heme

Heme, or haem (pronounced / hi:m/ ), is a precursor to hemoglobin, which is necessary to bind oxygen in the bloodstream. Heme is biosynthesized in both the bone marrow and the liver.

In biochemical terms, heme is a coordination complex "consisti ...

synthesis reactions ''(see also: porphyrin

Porphyrins ( ) are a group of heterocyclic macrocycle organic compounds, composed of four modified pyrrole subunits interconnected at their α carbon atoms via methine bridges (=CH−). The parent of porphyrin is porphine, a rare chemical com ...

)''

* Steroid

A steroid is a biologically active organic compound with four rings arranged in a specific molecular configuration. Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes that alter membrane fluidity; and a ...

synthesis.

* Hormonal signaling Mitochondria are sensitive and responsive to hormones, in part by the action of mitochondrial estrogen receptors (mtERs). These receptors have been found in various tissues and cell types, including brain and heart

* Immune signaling

* Neuronal mitochondria also contribute to cellular quality control by reporting neuronal status towards microglia through specialised somatic-junctions.

* Mitochondria of developing neurons contribute to intercellular signaling towards microglia, which communication is indispensable for proper regulation of brain development.

Some mitochondrial functions are performed only in specific types of cells. For example, mitochondria in liver cells contain enzymes that allow them to detoxify ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous was ...

, a waste product of protein metabolism. A mutation in the genes regulating any of these functions can result in mitochondrial disease

Mitochondrial disease is a group of disorders caused by mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondria are the organelles that generate energy for the cell and are found in every cell of the human body except red blood cells. They convert the energy of ...

s.

Mitochondrial proteins (proteins transcribed from mitochondrial DNA) vary depending on the tissue and the species. In humans, 615 distinct types of proteins have been identified from cardiac

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide to t ...

mitochondria, whereas in rats

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents. Species of rats are found throughout the order Rodentia, but stereotypical rats are found in the genus ''Rattus''. Other rat genera include ''Neotoma'' (pack rats), ''Bandicota'' (bandicoot ...

, 940 proteins have been reported. The mitochondrial proteome

The proteome is the entire set of proteins that is, or can be, expressed by a genome, cell, tissue, or organism at a certain time. It is the set of expressed proteins in a given type of cell or organism, at a given time, under defined conditions. ...

is thought to be dynamically regulated.Organization and distribution

Mitochondria (or related structures) are found in alleukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s (except the Oxymonad

The Oxymonads (or Oxymonadida) are a group of flagellated protozoa found exclusively in the intestines of termites and other wood-eating insects. Along with the similar parabasalid flagellates, they harbor the symbiotic bacteria that are respon ...

''Monocercomonoides

''Monocercomonoides'' is a genus of flagellate Excavata belonging to the order Oxymonadida. It was established by Bernard V. Travis and was first described as those with "polymastiginid flagellates having three anterior flagella and a trailin ...

''). Although commonly depicted as bean-like structures they form a highly dynamic network in the majority of cells where they constantly undergo fission and fusion

Fusion, or synthesis, is the process of combining two or more distinct entities into a new whole.

Fusion may also refer to:

Science and technology Physics

*Nuclear fusion, multiple atomic nuclei combining to form one or more different atomic nucl ...

. The population of all the mitochondria of a given cell constitutes the chondriome. Mitochondria vary in number and location according to cell type. A single mitochondrion is often found in unicellular organisms, while human liver cells have about 1000–2000 mitochondria per cell, making up 1/5 of the cell volume. The mitochondrial content of otherwise similar cells can vary substantially in size and membrane potential, with differences arising from sources including uneven partitioning at cell division, leading to extrinsic differences in ATP levels and downstream cellular processes. The mitochondria can be found nestled between myofibril

A myofibril (also known as a muscle fibril or sarcostyle) is a basic rod-like organelle of a muscle cell. Skeletal muscles are composed of long, tubular cells known as muscle fibers, and these cells contain many chains of myofibrils. Each myofib ...

s of muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of muscl ...

or wrapped around the sperm

Sperm is the male reproductive cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm with a tail known as a flagellum, whi ...

flagellum

A flagellum (; ) is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are termed as flagellates.

A microorganism may have f ...

. Often, they form a complex 3D branching network inside the cell with the cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compos ...

. The association with the cytoskeleton determines mitochondrial shape, which can affect the function as well: different structures of the mitochondrial network may afford the population a variety of physical, chemical, and signalling advantages or disadvantages. Mitochondria in cells are always distributed along microtubules and the distribution of these organelles is also correlated with the endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

. Recent evidence suggests that vimentin

Vimentin is a structural protein that in humans is encoded by the ''VIM'' gene. Its name comes from the Latin ''vimentum'' which refers to an array of flexible rods.

Vimentin is a type III intermediate filament (IF) protein that is expressed ...

, one of the components of the cytoskeleton, is also critical to the association with the cytoskeleton.

Mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM)

The mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM) is another structural element that is increasingly recognized for its critical role in cellular physiology andhomeostasis

In biology, homeostasis (British English, British also homoeostasis) Help:IPA/English, (/hɒmɪə(ʊ)ˈsteɪsɪs/) is the state of steady internal, physics, physical, and chemistry, chemical conditions maintained by organism, living systems. Thi ...

. Once considered a technical snag in cell fractionation techniques, the alleged ER vesicle contaminants that invariably appeared in the mitochondrial fraction have been re-identified as membranous structures derived from the MAM—the interface between mitochondria and the ER. Physical coupling between these two organelles had previously been observed in electron micrographs and has more recently been probed with fluorescence microscopy

A fluorescence microscope is an optical microscope that uses fluorescence instead of, or in addition to, scattering, reflection, and attenuation or absorption, to study the properties of organic or inorganic substances. "Fluorescence microscop ...

. Such studies estimate that at the MAM, which may comprise up to 20% of the mitochondrial outer membrane, the ER and mitochondria are separated by a mere 10–25 nm and held together by protein tethering complexes.

Purified MAM from subcellular fractionation is enriched in enzymes involved in phospholipid exchange, in addition to channels associated with Ca signaling. These hints of a prominent role for the MAM in the regulation of cellular lipid stores and signal transduction have been borne out, with significant implications for mitochondrial-associated cellular phenomena, as discussed below. Not only has the MAM provided insight into the mechanistic basis underlying such physiological processes as intrinsic apoptosis and the propagation of calcium signaling, but it also favors a more refined view of the mitochondria. Though often seen as static, isolated 'powerhouses' hijacked for cellular metabolism through an ancient endosymbiotic event, the evolution of the MAM underscores the extent to which mitochondria have been integrated into overall cellular physiology, with intimate physical and functional coupling to the endomembrane system.

Phospholipid transfer