Biology is the

scientific

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

study of

life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energy ...

.

It is a

natural science

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field.

For instance, all

organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells ( cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and fu ...

s are made up of

cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery ...

s that process hereditary information encoded in

gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

s, which can be transmitted to future generations. Another major theme is

evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

, which explains the unity and diversity of life.

is also important to life as it allows organisms to

move

Move may refer to:

People

* Daniil Move (born 1985), a Russian auto racing driver

Brands and enterprises

* Move (company), an online real estate company

* Move (electronics store), a defunct Australian electronics retailer

* Daihatsu Move

Go ...

, grow, and

reproduce.

Finally, all organisms are able to regulate their own

internal environment

The internal environment (or ''milieu intérieur'' in French) was a concept developed by Claude Bernard, a French physiologist in the 19th century, to describe the interstitial fluid and its physiological capacity to ensure protective stability ...

s.

Biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual cell, a multicellular organism, or a community of interacting populations. They usually specialize ...

s are able to study life at multiple

levels of organization

Biological organisation is the hierarchy of complex biological structures and systems that define life using a reductionistic approach. The traditional hierarchy, as detailed below, extends from atoms to biospheres. The higher levels of this ...

,

from the

molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and phys ...

of a cell to the

anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having i ...

and

physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemic ...

of

plants

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclude ...

and

animals

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and go through an ontogenetic stage in ...

, and evolution of

population

Population typically refers to the number of people in a single area, whether it be a city or town, region, country, continent, or the world. Governments typically quantify the size of the resident population within their jurisdiction usi ...

s.

[Based on definition from: ] Hence, there are multiple

subdisciplines within biology, each defined by the nature of their

research question

A research question is "a question that a research project sets out to answer". Choosing a research question is an essential element of both quantitative and qualitative research. Investigation will require data collection and analysis, and the me ...

s and the

tool

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates b ...

s that they use.

Like other

scientist

A scientist is a person who conducts scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosop ...

s, biologists use the

scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientifi ...

to make

observation

Observation is the active acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the perception and recording of data via the use of scientific instruments. The ...

s, pose questions, generate

hypotheses

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obse ...

, perform

experiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs whe ...

s, and form conclusions about the world around them.

Life on

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's sur ...

, which emerged more than 3.7 billion years ago,

is immensely diverse. Biologists have sought to study and classify the various forms of life, from

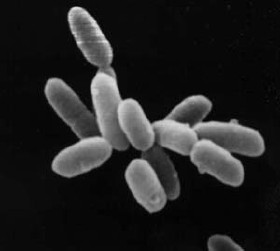

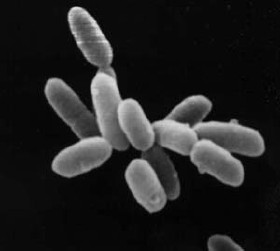

prokaryotic

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

organisms such as

archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaeba ...

and

bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

to

eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

organisms such as

protist

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the e ...

s,

fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately fr ...

, plants, and animals. These various organisms contribute to the

biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic ('' genetic variability''), species ('' species diversity''), and ecosystem ('' ecosystem diversity'') ...

of an

ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syst ...

, where they play specialized roles in the

cycling

Cycling, also, when on a two-wheeled bicycle, called bicycling or biking, is the use of cycles for transport, recreation, exercise or sport. People engaged in cycling are referred to as "cyclists", "bicyclists", or "bikers". Apart from ...

of

nutrient

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow, and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excre ...

s and

energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of ...

through their

biophysical environment

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale ...

.

History

The earliest of roots of

science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

, which included

medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

, can be traced to

ancient Egypt and

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

in around 3000 to 1200

BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

.

Their contributions later entered and shaped Greek

natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancien ...

of

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

.

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

philosophers such as

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

(384–322 BCE) contributed extensively to the development of biological knowledge. His works such as ''

History of Animals

''History of Animals'' ( grc-gre, Τῶν περὶ τὰ ζῷα ἱστοριῶν, ''Ton peri ta zoia historion'', "Inquiries on Animals"; la, Historia Animalium, "History of Animals") is one of the major Aristotle's biology, texts on biolo ...

'' were especially important because they revealed his naturalist leanings, and later more empirical works that focused on biological causation and the diversity of life. Aristotle's successor at the

Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Generally in that type of school the t ...

,

Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

, wrote a series of books on

botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

that survived as the most important contribution of antiquity to the plant sciences, even into the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

.

Scholars of the

medieval Islamic world who wrote on biology included

al-Jahiz

Abū ʿUthman ʿAmr ibn Baḥr al-Kinānī al-Baṣrī ( ar, أبو عثمان عمرو بن بحر الكناني البصري), commonly known as al-Jāḥiẓ ( ar, links=no, الجاحظ, ''The Bug Eyed'', born 776 – died December 868/Jan ...

(781–869),

Al-Dīnawarī (828–896), who wrote on botany,

and

Rhazes

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (full name: ar, أبو بکر محمد بن زکریاء الرازي, translit=Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī, label=none), () rather than ar, زکریاء, label=none (), as for example in , or in . In m ...

(865–925) who wrote on

anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having i ...

and

physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemic ...

.

Medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

was especially well studied by Islamic scholars working in Greek philosopher traditions, while natural history drew heavily on Aristotelian thought, especially in upholding a fixed hierarchy of life.

Biology began to quickly develop and grow with

Anton van Leeuwenhoek

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek ( ; ; 24 October 1632 – 26 August 1723) was a Dutch microbiologist and microscopist in the Golden Age of Dutch science and technology. A largely self-taught man in science, he is commonly known as " the ...

's dramatic improvement of the

microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisi ...

. It was then that scholars discovered

spermatozoa

A spermatozoon (; also spelled spermatozoön; ; ) is a motile sperm cell, or moving form of the haploid cell that is the male gamete. A spermatozoon joins an ovum to form a zygote. (A zygote is a single cell, with a complete set of chromos ...

,

bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

,

infusoria

Infusoria are minute freshwater life forms including ciliates, euglenoids, protozoa, unicellular algae and small invertebrates. Some authors (e.g., Bütschli) used the term as a synonym for Ciliophora. In modern formal classifications, the term ...

and the diversity of microscopic life. Investigations by

Jan Swammerdam

Jan Swammerdam (February 12, 1637 – February 17, 1680) was a Dutch biologist and microscopist. His work on insects demonstrated that the various phases during the life of an insect— egg, larva, pupa, and adult—are different forms of the ...

led to new interest in

entomology

Entomology () is the scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such as ara ...

and helped to develop the basic techniques of microscopic

dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

and

staining

Staining is a technique used to enhance contrast in samples, generally at the microscopic level. Stains and dyes are frequently used in histology (microscopic study of biological tissues), in cytology (microscopic study of cells), and in th ...

.

Advances in

microscopy

Microscopy is the technical field of using microscopes to view objects and areas of objects that cannot be seen with the naked eye (objects that are not within the resolution range of the normal eye). There are three well-known branches of micr ...

also had a profound impact on biological thinking. In the early 19th century, a number of biologists pointed to the central importance of the

cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery ...

. Then, in 1838,

Schleiden

Schleiden is a town in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It lies in the Eifel hills, in the district of Euskirchen, and has 12,998 inhabitants as of 30 June 2017. Schleiden is connected by a tourist railway to Kall, on the Eifel Railway between ...

and

Schwann began promoting the now universal ideas that (1) the basic unit of organisms is the cell and (2) that individual cells have all the characteristics of

life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energy ...

, although they opposed the idea that (3) all cells come from the division of other cells. However,

Robert Remak

Robert Remak (26 July 1815 – 29 August 1865) was a Jewish Polish-German embryologist, physiologist, and neurologist, born in Poznań, Posen, Prussia, who discovered that the origin of cells was by the Cell division, division of pre-existing cel ...

and

Rudolf Virchow

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow (; or ; 13 October 18215 September 1902) was a German physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician. He is known as "the father of modern pathology" and as the founder ...

were able to reify the third tenet, and by the 1860s most biologists accepted all three tenets which consolidated into

cell theory

In biology, cell theory is a scientific theory first formulated in the mid-nineteenth century, that living organisms are made up of cells, that they are the basic structural/organizational unit of all organisms, and that all cells come from pre ...

.

Meanwhile, taxonomy and classification became the focus of natural historians.

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

published a basic

taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

for the natural world in 1735 (variations of which have been in use ever since), and in the 1750s introduced

scientific names

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

for all his species.

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopédiste.

His works influenced the next two generations of naturalists, including two prominent ...

, treated species as artificial categories and living forms as malleable—even suggesting the possibility of

common descent

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. All living beings are in fact descendants of a unique ancestor commonly referred to as the last universal com ...

. Although he was opposed to evolution, Buffon is a key figure in the

history of evolutionary thought

Evolutionary thought, the recognition that species change over time and the perceived understanding of how such processes work, has roots in antiquity—in the ideas of the ancient Greeks, Romans, Chinese, Church Fathers as well as in medie ...

; his work influenced the evolutionary theories of both

Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolo ...

and

Darwin.

Serious evolutionary thinking originated with the works of

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolo ...

, who was the first to present a coherent theory of evolution.

[ Gould, Stephen Jay. ''The Structure of Evolutionary Theory''. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2002. . p. 187.] He posited that evolution was the result of environmental stress on properties of animals, meaning that the more frequently and rigorously an organ was used, the more complex and efficient it would become, thus adapting the animal to its environment. Lamarck believed that these acquired traits could then be passed on to the animal's offspring, who would further develop and perfect them.

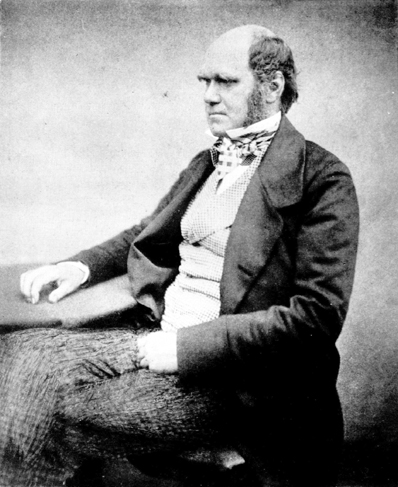

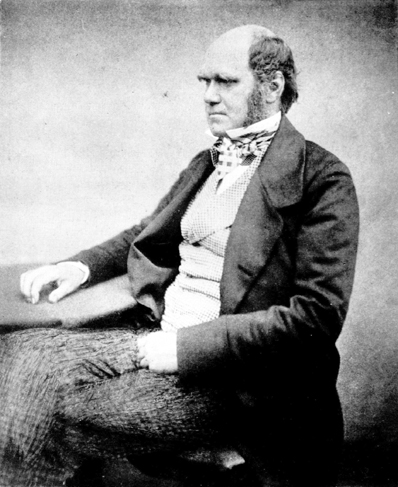

[ Lamarck (1914)] However, it was the British naturalist

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, combining the biogeographical approach of

Humboldt, the uniformitarian geology of

Lyell,

Malthus's writings on population growth, and his own morphological expertise and extensive natural observations, who forged a more successful evolutionary theory based on

natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

; similar reasoning and evidence led

Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British natural history, naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution thro ...

to independently reach the same conclusions. Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection quickly spread through the scientific community and soon became a central axiom of the rapidly developing science of biology.

The basis for modern genetics began with the work of

Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinian friar and abbot of St. Thomas' Abbey in Brünn (''Brno''), Margraviate of Moravia. Mendel was ...

, who presented his paper, "''Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden''" ("

Experiments on Plant Hybridization

"Experiments on Plant Hybridization" (German: "Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden") is a seminal paper written in 1865 and published in 1866 by Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian friar considered to be the founder of modern genetics. The paper was the r ...

"), in 1865, which outlined the principles of biological inheritance, serving as the basis for modern genetics.

However, the significance of his work was not realized until the early 20th century when evolution became a unified theory as the

modern synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and ...

reconciled Darwinian evolution with

classical genetics

Classical genetics is the branch of genetics based solely on visible results of reproductive acts. It is the oldest discipline in the field of genetics, going back to the experiments on Mendelian inheritance by Gregor Mendel who made it possible ...

.

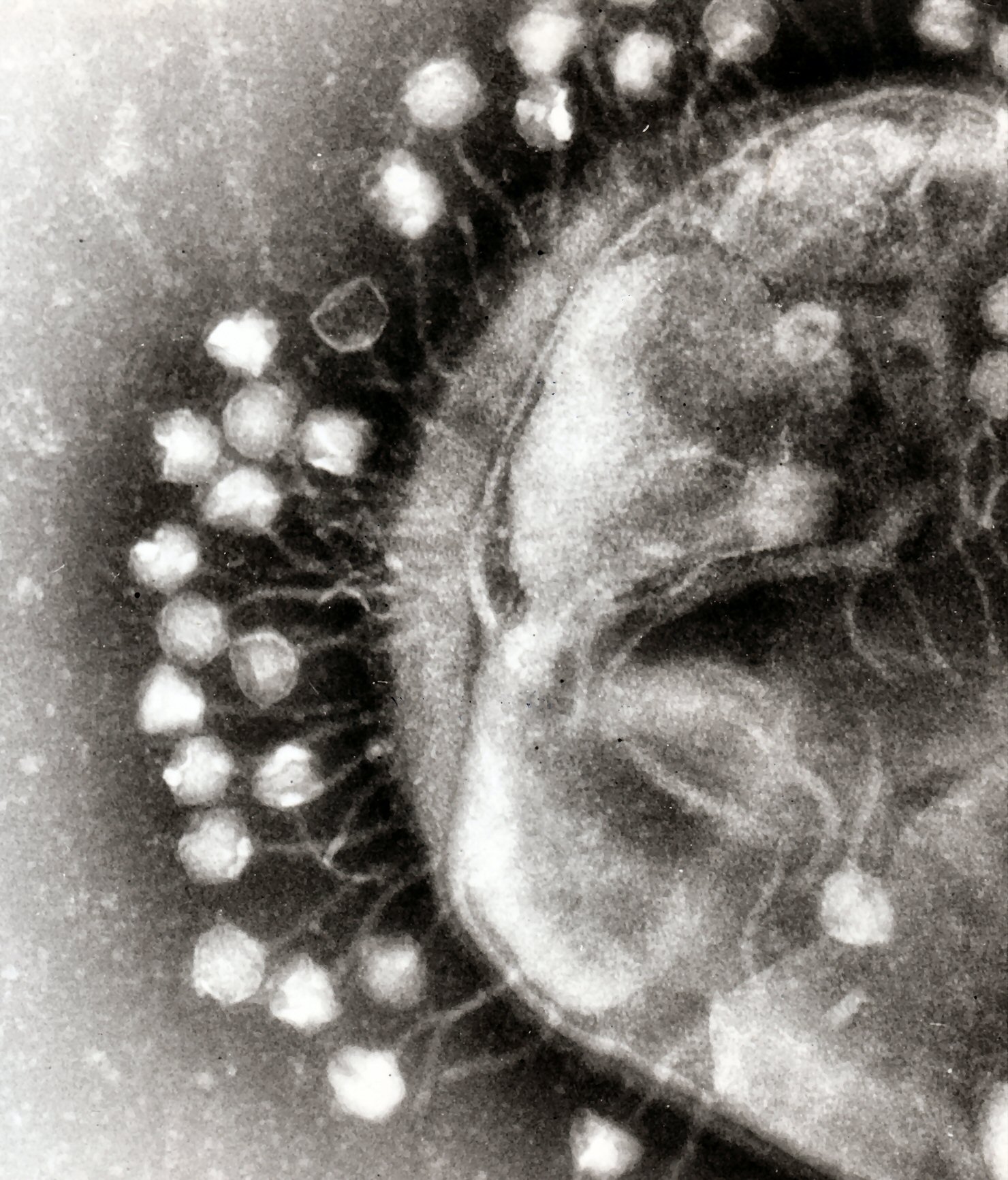

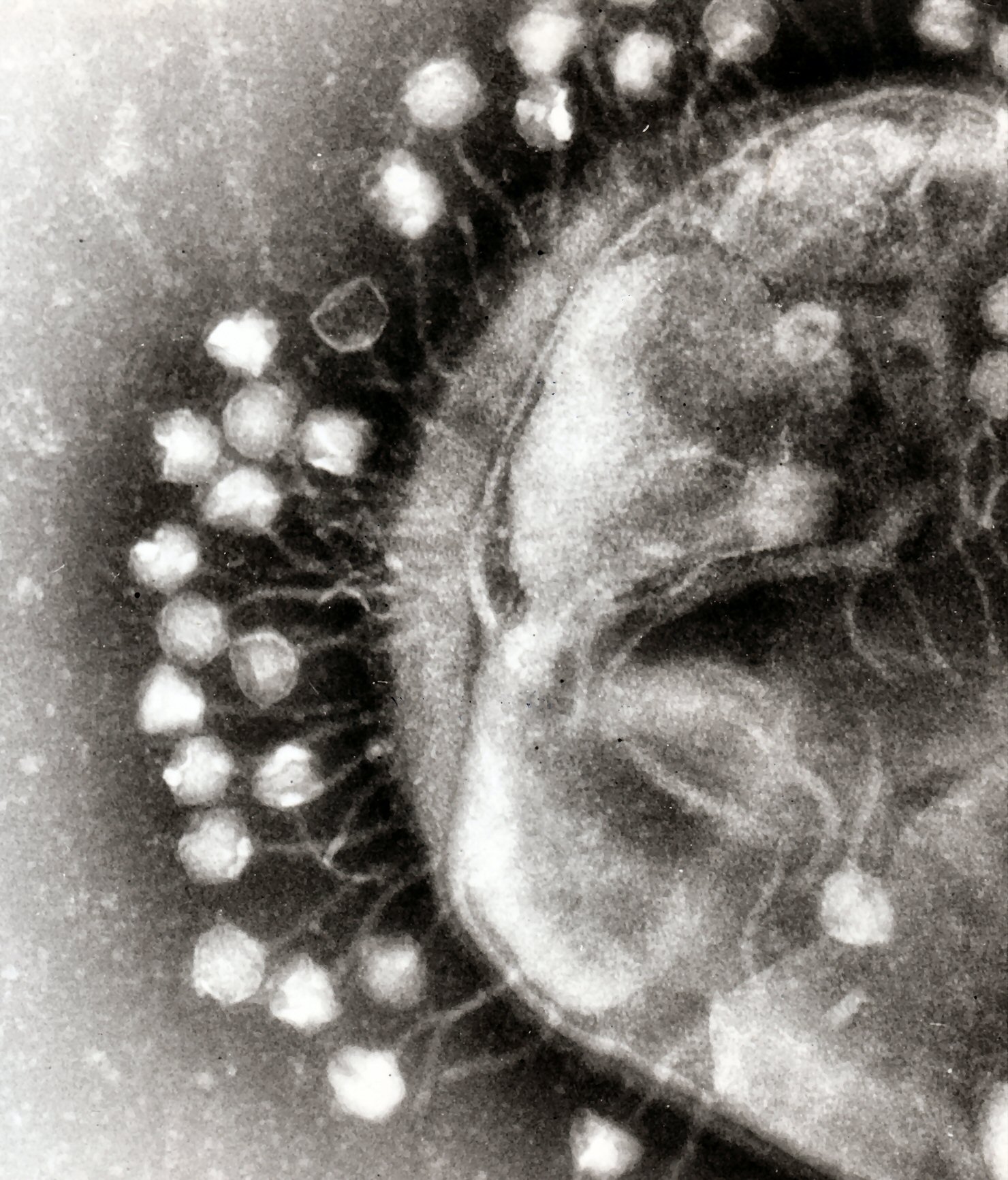

In the 1940s and early 1950s, a

series of experiments by

Alfred Hershey

Alfred Day Hershey (December 4, 1908 – May 22, 1997) was an American Nobel Prize–winning bacteriologist and geneticist.

He was born in Owosso, Michigan and received his B.S. in chemistry at Michigan State University in 1930 and his Ph.D. i ...

and

Martha Chase

Martha Cowles Chase (November 30, 1927 – August 8, 2003), also known as Martha C. Epstein, was an American geneticist who in 1952, with Alfred Hershey, experimentally helped to confirm that DNA rather than protein is the genetic material ...

pointed to

DNA as the component of

chromosomes

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins ar ...

that held the trait-carrying units that had become known as

genes

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

. A focus on new kinds of model organisms such as

viruses

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's ...

and

bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

, along with the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA by

James Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper proposing the double helix structure of the DNA molecule. Watson, Crick a ...

and

Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical stru ...

in 1953, marked the transition to the era of

molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a sub-field of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the ...

. From the 1950s onwards, biology has been vastly extended in the

molecular

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bio ...

domain. The

genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

was cracked by

Har Gobind Khorana

Har Gobind Khorana (9 January 1922 – 9 November 2011) was an Indian American biochemist. While on the faculty of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, he shared the 1968 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with Marshall W. Nirenberg and ...

,

Robert W. Holley and

Marshall Warren Nirenberg after DNA was understood to contain

codons

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

. Finally, the

Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both ...

was launched in 1990 with the goal of mapping the general human

genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

. This project was essentially completed in 2003, with further analysis still being published. The Human Genome Project was the first step in a globalized effort to incorporate accumulated knowledge of biology into a functional, molecular definition of the human body and the bodies of other organisms.

Chemical basis

Atoms and molecules

All organisms are made up of

chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their atomic nucleus, nuclei, including the pure Chemical substance, substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements canno ...

s;

oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

,

carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon ma ...

,

hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

, and

nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

account for 96% of all organisms, with

calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar ...

,

phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ea ...

,

sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formul ...

,

sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable ...

,

chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between them. Chlorine i ...

, and

magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element with the symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 of the periodic ...

constituting essentially all the remainder. Different elements can combine to form

compound

Compound may refer to:

Architecture and built environments

* Compound (enclosure), a cluster of buildings having a shared purpose, usually inside a fence or wall

** Compound (fortification), a version of the above fortified with defensive struc ...

s such as water, which is fundamental to life.

Biochemistry

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology and ...

is the study of

chemical processes

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Some references add that chemical substance cannot be separated into its constituent elements by physical separation methods, i.e., wit ...

within and relating to living

organisms

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells ( cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and fu ...

.

Molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and phys ...

is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including

molecular

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bio ...

synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions.

Water

Life arose from the Earth's first

ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wor ...

, which was formed approximately 3.8 billion years ago.

Since then,

water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as ...

continues to be the most abundant molecule in every organism. Water is important to life because it is an effective

solvent

A solvent (s) (from the Latin '' solvō'', "loosen, untie, solve") is a substance that dissolves a solute, resulting in a solution. A solvent is usually a liquid but can also be a solid, a gas, or a supercritical fluid. Water is a solvent for ...

, capable of dissolving solutes such as

sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable ...

and

chloride

The chloride ion is the anion (negatively charged ion) Cl−. It is formed when the element chlorine (a halogen) gains an electron or when a compound such as hydrogen chloride is dissolved in water or other polar solvents. Chloride s ...

ions or other small molecules to form an

aqueous

An aqueous solution is a solution in which the solvent is water. It is mostly shown in chemical equations by appending (aq) to the relevant chemical formula. For example, a solution of table salt, or sodium chloride (NaCl), in water would be re ...

solution

Solution may refer to:

* Solution (chemistry), a mixture where one substance is dissolved in another

* Solution (equation), in mathematics

** Numerical solution, in numerical analysis, approximate solutions within specified error bounds

* Solutio ...

. Once dissolved in water, these solutes are more likely to come in contact with one another and therefore take part in

chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the positions of electrons in the forming and breaking ...

s that sustain life.

In terms of its

molecular structure, water is a small

polar molecule

In chemistry, polarity is a separation of electric charge leading to a molecule or its chemical groups having an electric dipole moment, with a negatively charged end and a positively charged end.

Polar molecules must contain one or more polar ...

with a bent shape formed by the polar covalent bonds of two hydrogen (H) atoms to one oxygen (O) atom (H

2O).

Because the O–H bonds are polar, the oxygen atom has a slight negative charge and the two hydrogen atoms have a slight positive charge.

This polar

property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

of water allows it to attract other water molecules via hydrogen bonds, which makes water

cohesive.

Surface tension

Surface tension is the tendency of liquid surfaces at rest to shrink into the minimum surface area possible. Surface tension is what allows objects with a higher density than water such as razor blades and insects (e.g. water striders) t ...

results from the cohesive force due to the attraction between molecules at the surface of the liquid.

Water is also

adhesive

Adhesive, also known as glue, cement, mucilage, or paste, is any non-metallic substance applied to one or both surfaces of two separate items that binds them together and resists their separation.

The use of adhesives offers certain advant ...

as it is able to adhere to the surface of any polar or charged non-water molecules.

Water is

denser

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' can also be used. Mathematically ...

as a

liquid

A liquid is a nearly incompressible fluid that conforms to the shape of its container but retains a (nearly) constant volume independent of pressure. As such, it is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, gas, ...

than it is as a solid (or

ice).

This unique property of water allows ice to float above liquid water such as ponds, lakes, and oceans, thereby

insulating the liquid below from the cold air above.

The lower density of ice compared to liquid water is due to the lower number of water molecules that form the

crystal lattice structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of the ordered arrangement of atoms, ions or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from the intrinsic nature of the constituent particles to form symmetric patterns t ...

of ice, which leaves a large amount of space between water molecules.

In contrast, there is no crystal lattice structure in liquid water, which allows more water molecules to occupy the same amount of volume.

Water also has the capacity to absorb energy, giving it a higher

specific heat capacity

In thermodynamics, the specific heat capacity (symbol ) of a substance is the heat capacity of a sample of the substance divided by the mass of the sample, also sometimes referred to as massic heat capacity. Informally, it is the amount of heat t ...

than other solvents such as

ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl group linked to a ...

.

Thus, a large amount of energy is needed to break the hydrogen bonds between water molecules to convert liquid water into

water vapor

(99.9839 °C)

, -

, Boiling point

,

, -

, specific gas constant

, 461.5 J/( kg·K)

, -

, Heat of vaporization

, 2.27 MJ/kg

, -

, Heat capacity

, 1.864 kJ/(kg·K)

Water vapor, water vapour or aqueous vapor is the gaseous p ...

.

As a molecule, water is not completely stable as each water molecule continuously dissociates into

hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

and

hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydrox ...

ions before reforming into a water molecule again.

In

pure water

Purified water is water that has been mechanically filtered or processed to remove impurities and make it suitable for use. Distilled water was, formerly, the most common form of purified water, but, in recent years, water is more frequently puri ...

, the number of hydrogen ions balances (or equals) the number of hydroxyl ions, resulting in a

pH that is neutral.

Organic compounds

Organic compound

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. Th ...

s are molecules that contain carbon bonded to another element such as hydrogen.

With the exception of water, nearly all the molecules that make up each organism contain carbon.

Carbon can form

covalent bond

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between ato ...

s with up to four other atoms, enabling it to form diverse, large, and complex molecules.

For example, a single carbon atom can form four single covalent bonds such as in

methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane ...

, two

double covalent bonds such as in

carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

(), or a

triple covalent bond such as in

carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide ( chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simpl ...

(CO). Moreover, carbon can form very long chains of interconnecting

carbon–carbon bonds such as

octane

Octane is a hydrocarbon and an alkane with the chemical formula , and the condensed structural formula . Octane has many structural isomers that differ by the amount and location of branching in the carbon chain. One of these isomers, 2,2,4-t ...

or ring-like structures such as

glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, u ...

.

The simplest form of an organic molecule is the

hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and hydrophobic, and their odors are usually weak or ...

, which is a large family of organic compounds that are composed of

hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

atoms bonded to a chain of carbon atoms. A hydrocarbon backbone can be substituted by other elements such as

oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

(O),

hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

(H),

phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ea ...

(P), and

sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formul ...

(S), which can change the chemical behavior of that compound.

Groups of atoms that contain these elements (O-, H-, P-, and S-) and are bonded to a central carbon atom or skeleton are called

functional group

In organic chemistry, a functional group is a substituent or moiety in a molecule that causes the molecule's characteristic chemical reactions. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reactions regardless of the r ...

s.

There are six prominent functional groups that can be found in organisms:

amino group

In chemistry, amines (, ) are compounds and functional groups that contain a basic nitrogen atom with a lone pair. Amines are formally derivatives of ammonia (), wherein one or more hydrogen atoms have been replaced by a substituent such ...

,

carboxyl group

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is or , with R referring to the alkyl, alkenyl, aryl, or other group. Carboxylic ...

,

carbonyl group

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom: C=O. It is common to several classes of organic compounds, as part of many larger functional groups. A compound containi ...

,

hydroxyl group

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

,

phosphate group

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from phosph ...

, and

sulfhydryl group

In organic chemistry, a thiol (; ), or thiol derivative, is any organosulfur compound of the form , where R represents an alkyl or other organic substituent. The functional group itself is referred to as either a thiol group or a sulfhydryl grou ...

.

In 1953, the

Miller-Urey experiment showed that organic compounds could be synthesized abiotically within a closed system mimicking the conditions of

early Earth

The early Earth is loosely defined as Earth in its first one billion years, or gigayear (Ga, 109y). The “early Earth” encompasses approximately the first gigayear in the evolution of our planet, from its initial formation in the young Solar ...

, thus suggesting that complex organic molecules could have arisen spontaneously in early Earth (see

abiogenesis

In biology, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothes ...

).

Macromolecules

Macromolecule

A macromolecule is a very large molecule important to biophysical processes, such as a protein or nucleic acid. It is composed of thousands of covalently bonded atoms. Many macromolecules are polymers of smaller molecules called monomers. The ...

s are large molecules made up of smaller molecular subunits that are joined.

Small molecules such as sugars, amino acids, and nucleotides can act as single repeating units called

monomer

In chemistry, a monomer ( ; '' mono-'', "one" + '' -mer'', "part") is a molecule that can react together with other monomer molecules to form a larger polymer chain or three-dimensional network in a process called polymerization.

Classification

...

s to form chain-like molecules called

polymer

A polymer (; Greek '' poly-'', "many" + '' -mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic a ...

s via a chemical process called

condensation

Condensation is the change of the state of matter from the gas phase into the liquid phase, and is the reverse of vaporization. The word most often refers to the water cycle. It can also be defined as the change in the state of water vapo ...

.

For example, amino acids can form

polypeptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

...

s whereas nucleotides can form strands of nucleic acid. Polymers make up three of the four macromolecules (

polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with w ...

s,

lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids in ...

s,

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s, and

nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main ...

s) that are found in all organisms. Each of these macromolecules plays a specialized role within any given cell.

Carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may o ...

s (or

sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or do ...

) are molecules with the molecular formula , with ''n'' being the number of carbon-hydrate groups.

They include monosaccharides (monomer), oligosaccharides (small polymers), and polysaccharides (large polymers). Monosaccharides can be linked together by

glycosidic linkage

A glycosidic bond or glycosidic linkage is a type of covalent bond that joins a carbohydrate (sugar) molecule to another group, which may or may not be another carbohydrate.

A glycosidic bond is formed between the hemiacetal or hemiketal group ...

s, a type of covalent bond.

When two monosaccharides such as

glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, u ...

and

fructose

Fructose, or fruit sugar, is a ketonic simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and galactose, that are absorb ...

are linked together, they can form a

disaccharide

A disaccharide (also called a double sugar or ''biose'') is the sugar formed when two monosaccharides are joined by glycosidic linkage. Like monosaccharides, disaccharides are simple sugars soluble in water. Three common examples are sucrose, la ...

such as

sucrose

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refine ...

.

When many monosaccharides are linked together, they can form an oligosaccharide or a polysaccharide, depending on the number of monosaccharides. Polysaccharides can vary in function. Monosaccharides such as glucose can be a source of energy and some polysaccharides can serve as storage material that can be

hydrolyzed

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water is the nucleophile.

Biological hydrolysis ...

to provide cells with sugar.

Lipids are the only class of macromolecules that are not made up of polymers. The most biologically important lipids are

steroid

A steroid is a biologically active organic compound with four rings arranged in a specific molecular configuration. Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes that alter membrane fluidity; and ...

s,

phospholipid

Phospholipids, are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s, and

fats.

These lipids are organic compounds that are largely nonpolar and hydrophobic.

Steroids are organic compounds that consist of four fused rings.

Phospholipids consist of glycerol that is linked to a phosphate group and two hydrocarbon chains (or

fatty acid

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, f ...

s).

The glycerol and phosphate group together constitute the polar and

hydrophilic

A hydrophile is a molecule or other molecular entity that is attracted to water molecules and tends to be dissolved by water.Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon'' Oxford: Clarendon Press.

In contrast, hydrophobes are n ...

(or head) region of the molecule whereas the fatty acids make up the nonpolar and hydrophobic (or tail) region.

Thus, when in water, phospholipids tend to form a

phospholipid bilayer

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many vir ...

whereby the hydrophobic heads face outwards to interact with water molecules. Conversely, the hydrophobic tails face inwards towards other hydrophobic tails to avoid contact with water.

Proteins are the most diverse of the macromolecules, which include

enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

s,

transport protein

A transport protein (variously referred to as a transmembrane pump, transporter, escort protein, acid transport protein, cation transport protein, or anion transport protein) is a protein that serves the function of moving other materials within ...

s, large

signaling

In signal processing, a signal is a function that conveys information about a phenomenon. Any quantity that can vary over space or time can be used as a signal to share messages between observers. The '' IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing' ...

molecules,

antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of ...

, and

structural proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respond ...

. The basic unit (or monomer) of a protein is an amino acid, which has a central carbon atom that is covalently bonded to a hydrogen atom, an

amino group

In chemistry, amines (, ) are compounds and functional groups that contain a basic nitrogen atom with a lone pair. Amines are formally derivatives of ammonia (), wherein one or more hydrogen atoms have been replaced by a substituent such ...

, a

carboxyl group

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is or , with R referring to the alkyl, alkenyl, aryl, or other group. Carboxylic ...

, and a

side chain

In organic chemistry and biochemistry, a side chain is a chemical group that is attached to a core part of the molecule called the "main chain" or backbone. The side chain is a hydrocarbon branching element of a molecule that is attached to a ...

(or R-group, "R" for residue).

There are twenty amino acids that make up the building blocks of proteins, with each amino acid having its own unique side chain.

The polarity and charge of the side chains affect the solubility of amino acids. An amino acid with a side chain that is polar and electrically charged is soluble as it is hydrophilic whereas an amino acid with a side chain that lacks a charged or an electronegative atom is hydrophobic and therefore tends to coalesce rather than dissolve in water.

Proteins have four distinct levels of organization (

primary

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Works

...

,

secondary

Secondary may refer to: Science and nature

* Secondary emission, of particles

** Secondary electrons, electrons generated as ionization products

* The secondary winding, or the electrical or electronic circuit connected to the secondary winding i ...

,

tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

, and

quartenary). The primary structure consists of a unique sequence of amino acids that are covalently linked together by

peptide bond

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 (carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 (nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein cha ...

s.

The side chains of the individual amino acids can then interact with each other, giving rise to the secondary structure of a protein.

The two common types of secondary structures are

alpha helices

The alpha helix (α-helix) is a common motif in the secondary structure of proteins and is a right hand-helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid located four residues ear ...

and

beta sheet

The beta sheet, (β-sheet) (also β-pleated sheet) is a common motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone hydrogen bonds, forming a ge ...

s.

The folding of alpha helices and beta sheets gives a protein its three-dimensional or tertiary structure. Finally, multiple tertiary structures can combine to form the quaternary structure of a protein.

Nucleic acids are polymers made up of monomers called nucleotides.

Their function is to store, transmit, and express hereditary information.

Nucleotides consist of a phosphate group, a five-carbon sugar, and a nitrogenous base. Ribonucleotides, which contain ribose as the sugar, are the monomers of

ribonucleic acid (RNA). In contrast, deoxyribonucleotides contain deoxyribose as the sugar and are constitute the monomers of

deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). RNA and DNA also differ with respect to one of their bases.

There are two types of bases:

purine

Purine is a heterocyclic aromatic organic compound that consists of two rings ( pyrimidine and imidazole) fused together. It is water-soluble. Purine also gives its name to the wider class of molecules, purines, which include substituted purines ...

s and

pyrimidine

Pyrimidine (; ) is an aromatic, heterocyclic, organic compound similar to pyridine (). One of the three diazines (six-membered heterocyclics with two nitrogen atoms in the ring), it has nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 3 in the ring. The othe ...

s.

The purines include

guanine

Guanine () ( symbol G or Gua) is one of the four main nucleobases found in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA, the others being adenine, cytosine, and thymine ( uracil in RNA). In DNA, guanine is paired with cytosine. The guanine nucleoside is ...

(G) and

adenine

Adenine () ( symbol A or Ade) is a nucleobase (a purine derivative). It is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The three others are guanine, cytosine and thymine. Its deriv ...

(A) whereas the pyrimidines consist of

cytosine

Cytosine () ( symbol C or Cyt) is one of the four nucleobases found in DNA and RNA, along with adenine, guanine, and thymine ( uracil in RNA). It is a pyrimidine derivative, with a heterocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents attached ( ...

(C),

uracil

Uracil () (symbol U or Ura) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid RNA. The others are adenine (A), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). In RNA, uracil binds to adenine via two hydrogen bonds. In DNA, the uracil nucleobase is replaced b ...

(U), and

thymine

Thymine () ( symbol T or Thy) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The others are adenine, guanine, and cytosine. Thymine is also known as 5-methyluracil, a pyrimidin ...

(T). Uracil is used in RNA whereas thymine is used in DNA. Taken together, when the different sugar and bases are take into consideration, there are eight distinct nucleotides that can form two types of nucleic acids: DNA (A, G, C, and T) and RNA (A, G, C, and U).

Cells

Cell theory

In biology, cell theory is a scientific theory first formulated in the mid-nineteenth century, that living organisms are made up of cells, that they are the basic structural/organizational unit of all organisms, and that all cells come from pre ...

states that

cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery ...

s are the fundamental units of life, that all living things are composed of one or more cells, and that all cells arise from preexisting cells through

cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukaryotes, there ...

.

Most cells are very small, with diameters ranging from 1 to 100

micrometer Micrometer can mean:

* Micrometer (device), used for accurate measurements by means of a calibrated screw

* American spelling of micrometre

The micrometre ( international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; ...

s and are therefore only visible under a

light

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm), corresponding to frequencies of 750–420 t ...

or

electron microscope

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

. There are generally two types of cells:

eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

cells, which contain a

nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

* Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucl ...

, and

prokaryotic

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

cells, which do not. Prokaryotes are

single-celled organisms such as

bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

, whereas eukaryotes can be single-celled or

multicellular

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially ...

. In

multicellular organisms

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni ...

, every cell in the organism's body is derived ultimately from a

single cell Single cell and similar can mean:

Biology

* Single-cell organism

*Single-cell protein

* Single-cell recording, a neuro-electric monitoring technique

* Single-cell sequencing

**Single cell epigenomics

*Single-cell transcriptomics

Other

*Single-cell ...

in a fertilized

egg.

Cell structure

Every cell is enclosed within a

cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment (t ...

that separates its

cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. ...

from the

extracellular space

Extracellular space refers to the part of a multicellular organism outside the cells, usually taken to be outside the plasma membranes, and occupied by fluid. This is distinguished from intracellular space, which is inside the cells.

The compos ...

.

A cell membrane consists of a

lipid bilayer

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many vir ...

, including

cholesterol

Cholesterol is any of a class of certain organic molecules called lipids. It is a sterol (or modified steroid), a type of lipid. Cholesterol is biosynthesized by all animal cells and is an essential structural component of animal cell memb ...

s that sit between

phospholipid

Phospholipids, are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s to maintain their

fluidity at various temperatures. Cell membranes are

semipermeable

Semipermeable membrane is a type of biological or synthetic, polymeric membrane that will allow certain molecules or ions to pass through it by osmosis. The rate of passage depends on the pressure, concentration, and temperature of the molecul ...

, allowing small molecules such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, and water to pass through while restricting the movement of larger molecules and charged particles such as

ions.

Cell membranes also contains

membrane protein

Membrane proteins are common proteins that are part of, or interact with, biological membranes. Membrane proteins fall into several broad categories depending on their location. Integral membrane proteins are a permanent part of a cell membrane ...

s, including

integral membrane protein

An integral, or intrinsic, membrane protein (IMP) is a type of membrane protein that is permanently attached to the biological membrane. All ''transmembrane proteins'' are IMPs, but not all IMPs are transmembrane proteins. IMPs comprise a sign ...

s that go across the membrane serving as

membrane transporter

A membrane transport protein (or simply transporter) is a membrane protein involved in the movement of ions, small molecules, and macromolecules, such as another protein, across a biological membrane. Transport proteins are integral transmembran ...

s, and

peripheral proteins that loosely attach to the outer side of the cell membrane, acting as

enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

s shaping the cell.

Cell membranes are involved in various cellular processes such as

cell adhesion

Cell adhesion is the process by which cells interact and attach to neighbouring cells through specialised molecules of the cell surface. This process can occur either through direct contact between cell surfaces such as cell junctions or indire ...

,

storing electrical energy, and

cell signalling

In biology, cell signaling (cell signalling in British English) or cell communication is the ability of a cell to receive, process, and transmit signals with its environment and with itself. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all cellular ...

and serve as the attachment surface for several extracellular structures such as a

cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mec ...

,

glycocalyx