The history of Christianity concerns the

Christian religion,

Christian countries, and the

Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

with their various

denominations, from the

1st century

The 1st century was the century spanning AD 1 ( I) through AD 100 ( C) according to the Julian calendar. It is often written as the or to distinguish it from the 1st century BC (or BCE) which preceded it. The 1st century is considered part of ...

to the

present

The present (or here'' and ''now) is the time that is associated with the events perceived directly and in the first time, not as a recollection (perceived more than once) or a speculation (predicted, hypothesis, uncertain). It is a period of ...

. Christianity originated with the

ministry of

Jesus, a Jewish teacher and healer who proclaimed the imminent

Kingdom of God and was

crucified

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagin ...

in

Jerusalem in the

Roman province of

Judea. His followers believe that, according to the

Gospels, he was the Son of God and that he died for the forgiveness of sins and was

raised from the dead and exalted by God, and will return soon at the inception of God's kingdom.

The earliest followers of Jesus were

apocalyptic Jewish Christians. The inclusion of

Gentiles in the developing early Christian Church caused the

separation of early Christianity from Judaism during the first two centuries of the

Christian era

The terms (AD) and before Christ (BC) are used to label or number years in the Julian and Gregorian calendars. The term is Medieval Latin and means 'in the year of the Lord', but is often presented using "our Lord" instead of "the Lord", ...

. In 313, the Roman Emperor

Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterrane ...

issued the

Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

legalizing Christian worship. In 380, with the

Edict of Thessalonica put forth under

Theodosius I, the Roman Empire officially adopted

Trinitarian Christianity as its state religion, and Christianity established itself as a predominantly Roman religion in the

state church of the Roman Empire. Various

Christological debates about the human and divine nature of Jesus consumed the Christian Church for three centuries, and

seven ecumenical councils were called to resolve these debates.

Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

was condemned at the

First Council of Nicea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

(325), which supported the Trinitarian doctrine as expounded in the

Nicene Creed.

In the

Early Middle Ages, missionary activities spread Christianity towards the west and the north among

Germanic peoples; towards the east among

Armenians,

Georgians, and

Slavic peoples; in the

Middle East among

Syrians

Syrians ( ar, سُورِيُّون, ''Sūriyyīn'') are an Eastern Mediterranean ethnic group indigenous to the Levant. They share common Levantine Semitic roots. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend of both indi ...

and

Egyptians; in

Eastern Africa among the

Ethiopians

Ethiopians are the native inhabitants of Ethiopia, as well as the global diaspora of Ethiopia. Ethiopians constitute several component ethnic groups, many of which are closely related to ethnic groups in neighboring Eritrea and other parts o ...

; and further into

Central Asia,

China, and

India. During the

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 1500 ...

, Eastern and Western Christianity grew apart, leading to the

East–West Schism of 1054. Growing

criticism

Criticism is the construction of a judgement about the negative qualities of someone or something. Criticism can range from impromptu comments to a written detailed response. , ''"the act of giving your opinion or judgment about the good or bad q ...

of the

Roman Catholic ecclesiastical structure and its corruption led to the

Protestant Reformation and its related

reform movements in the 15th and 16th centuries, which concluded with the

European wars of religion that set off the split of Western Christianity. Since the

Renaissance era, with the

European colonization of

the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with ...

and other continents

actively instigated by the Christian churches,

Christianity has expanded throughout the world. Today, there are

more than two billion Christians worldwide and

Christianity has become the world's largest religion. Within the last century, as

the influence of Christianity has progressively waned in the Western world, Christianity continues to be the predominant religion in

Europe (including

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eight ...

) and

the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with ...

, and

has rapidly grown in

Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

as well as in the

Global South

The concept of Global North and Global South (or North–South divide in a global context) is used to describe a grouping of countries along socio-economic and political characteristics. The Global South is a term often used to identify region ...

and

Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the "First W ...

countries, most notably in

Latin America,

China,

South Korea, and much of

Sub-Saharan Africa.

Origins

Jewish-Hellenistic background

The

religious,

social, and

political climate of 1st-century

Roman Judea

Judaea ( la, Iudaea ; grc, Ἰουδαία, translit=Ioudaíā ) was a Roman province which incorporated the regions of Judea, Samaria, and Idumea from 6 CE, extending over parts of the former regions of the Hasmonean and Herodian kingdom ...

and its neighbouring

provinces

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outsi ...

was extremely diverse and constantly characterized by socio-political turmoil,

with numerous Judaic movements that were both religious and political. The ancient Roman-Jewish historian

Josephus described the four most prominent sects within Second Temple Judaism:

Pharisees,

Sadducees,

Essenes, and an unnamed "fourth philosophy", which modern historians recognize to be the

Zealots

The Zealots were a political movement in 1st-century Second Temple Judaism which sought to incite the people of Judea Province to rebel against the Roman Empire and expel it from the Holy Land by force of arms, most notably during the First Jew ...

and

Sicarii

The Sicarii (Modern Hebrew: סיקריים ''siqariyim'') were a splinter group of the Jewish Zealots who, in the decades preceding Jerusalem's destruction in 70 CE, strongly opposed the Roman occupation of Judea and attempted to expel them and th ...

.

The 1st century BC and 1st century AD had numerous charismatic religious leaders contributing to what would become the ''

Mishnah'' of

Rabbinic Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism ( he, יהדות רבנית, Yahadut Rabanit), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, or Judaism espoused by the Rabbanites, has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Babylonian ...

, including the Jewish sages

Yohanan ben Zakkai and

Hanina ben Dosa

Hanina ben Dosa ( he, ) was a first-century Jewish scholar and miracle-worker and the pupil of Johanan ben Zakai. He is buried in the town of Arraba in northern Israel.Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p206/ref>

Biography

Hanina lived in the ...

.

Jewish messianism, and the Jewish Messiah concept, has its

roots

A root is the part of a plant, generally underground, that anchors the plant body, and absorbs and stores water and nutrients.

Root or roots may also refer to:

Art, entertainment, and media

* ''The Root'' (magazine), an online magazine focusing ...

in the

apocalyptic literature

Apocalyptic literature is a genre of prophetical writing that developed in post- Exilic Jewish culture and was popular among millennialist early Christians. ''Apocalypse'' ( grc, , }) is a Greek word meaning "revelation", "an unveiling or unfol ...

produced between the 2nd century BC and the 1st century BC,

promising a future "anointed" leader (messiah or king) from the

Davidic line to resurrect the

Israelite Kingdom of God, in place of the foreign rulers of the time.

Ministry of Jesus

The main sources of information regarding

Jesus' life and

teachings are the four

canonical gospels

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

, and to a lesser extent the

Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its message ...

and the

Pauline epistles

The Pauline epistles, also known as Epistles of Paul or Letters of Paul, are the thirteen books of the New Testament attributed to Paul the Apostle, although the authorship of some is in dispute. Among these epistles are some of the earliest extan ...

. According to the Gospels, Jesus is the

Son of God, who was

crucified

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagin ...

in

Jerusalem. His followers believed that he was

raised from the dead and exalted by God, heralding the coming

Kingdom of God.

Early Christianity (c. 31/33–324)

Early Christianity is generally reckoned by

church historians to begin with the ministry of Jesus ( 27–30) and end with the

First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

(325). It is typically divided into two periods: the ''Apostolic Age'' ( 30–100, when the first apostles were still alive) and the ''Ante-Nicene Period'' ( 100–325).

Apostolic Age

The Apostolic Age is named after the

Apostles

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary, from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to send off". The purpose of such sending ...

and their missionary activities. It holds special significance in Christian tradition as the age of the direct apostles of Jesus. A

primary source for the Apostolic Age is the

Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its message ...

, but

its historical accuracy has been debated and its coverage is partial, focusing especially from Acts 15 onwards on the ministry of

Paul

Paul may refer to:

* Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chr ...

, and ending around 62 AD with Paul preaching in

Rome under

house arrest.

The earliest followers of

Jesus were a sect of

apocalyptic Jewish Christian

Jewish Christians ( he, יהודים נוצרים, yehudim notzrim) were the followers of a Jewish religious sect that emerged in Judea during the late Second Temple period (first century AD). The Nazarene Jews integrated the belief of Jesus a ...

s within the realm of

Second Temple Judaism

Second Temple Judaism refers to the Jewish religion as it developed during the Second Temple period, which began with the construction of the Second Temple around 516 BCE and ended with the Roman siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE.

The Second Temple p ...

.

The early Christian groups were strictly Jewish, such as the

Ebionites,

and the early Christian community in

Jerusalem, led by

James the Just, brother of Jesus. According to Acts 9, they described themselves as "disciples of the Lord" and

ollowers"of the Way", and according to Acts 11, a settled community of disciples at

Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

were the first to be called "Christians". Some of the early Christian communities attracted

God-fearers, i.e. Greco-Roman sympathizers which made an allegiance to Judaism but refused to convert and therefore retained their Gentile (non-Jewish) status, who already visited Jewish synagogues.

The inclusion of Gentiles posed a problem, as they could not fully observe the

Halakha. Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as

Paul the Apostle

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

, persecuted the early Jewish Christians, then

converted and started his mission among the Gentiles.

The main concern of

Paul's letters is the inclusion of Gentiles into God's

New Covenant

The New Covenant (Hebrew '; Greek ''diatheke kaine'') is a biblical interpretation which was originally derived from a phrase which is contained in the Book of Jeremiah ( Jeremiah 31:31-34), in the Hebrew Bible (or the Old Testament of the Ch ...

, sending the message that

faith in Christ is sufficient for

salvation.

Because of this inclusion of Gentiles, early Christianity changed its character and gradually

grew apart from Judaism during the first two centuries of the Christian Era.

The fourth-century church fathers Eusebius and Epiphanius of Salamis cite a tradition that before the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 the Jerusalem Christians had been warned to

flee to Pella in the region of the Decapolis across the Jordan River.

The Gospels and

New Testament epistles contain early

creeds and

hymns, as well as accounts of the

Passion, the empty tomb, and Resurrection appearances. Early Christianity spread to pockets of believers among

Aramaic-speaking peoples along the

Mediterranean coast and also to the inland parts of the Roman Empire and beyond, into the

Parthian Empire and the later

Sasanian Empire, including

Mesopotamia, which was dominated at different times and to varying extent by these empires.

Ante-Nicene period

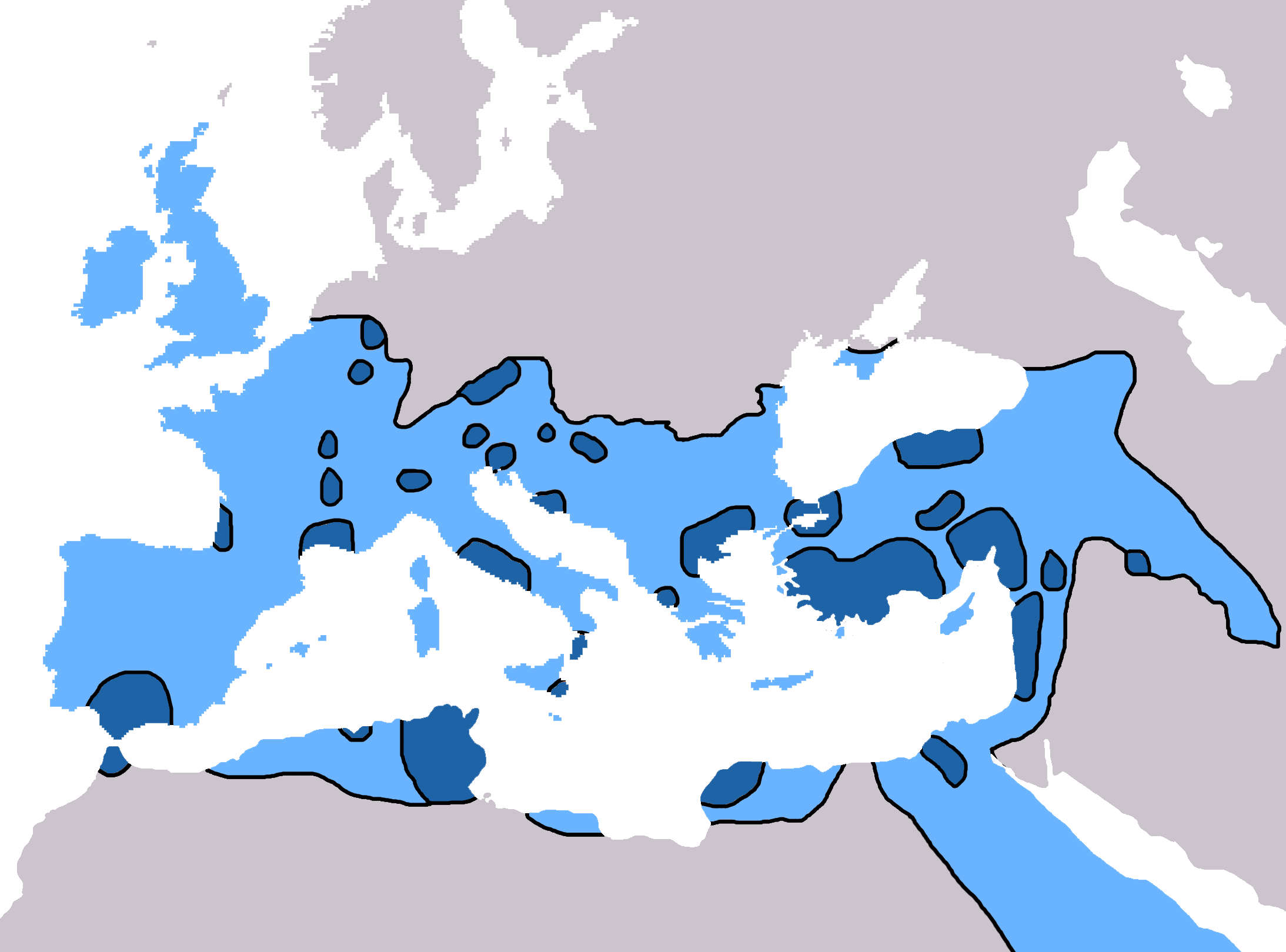

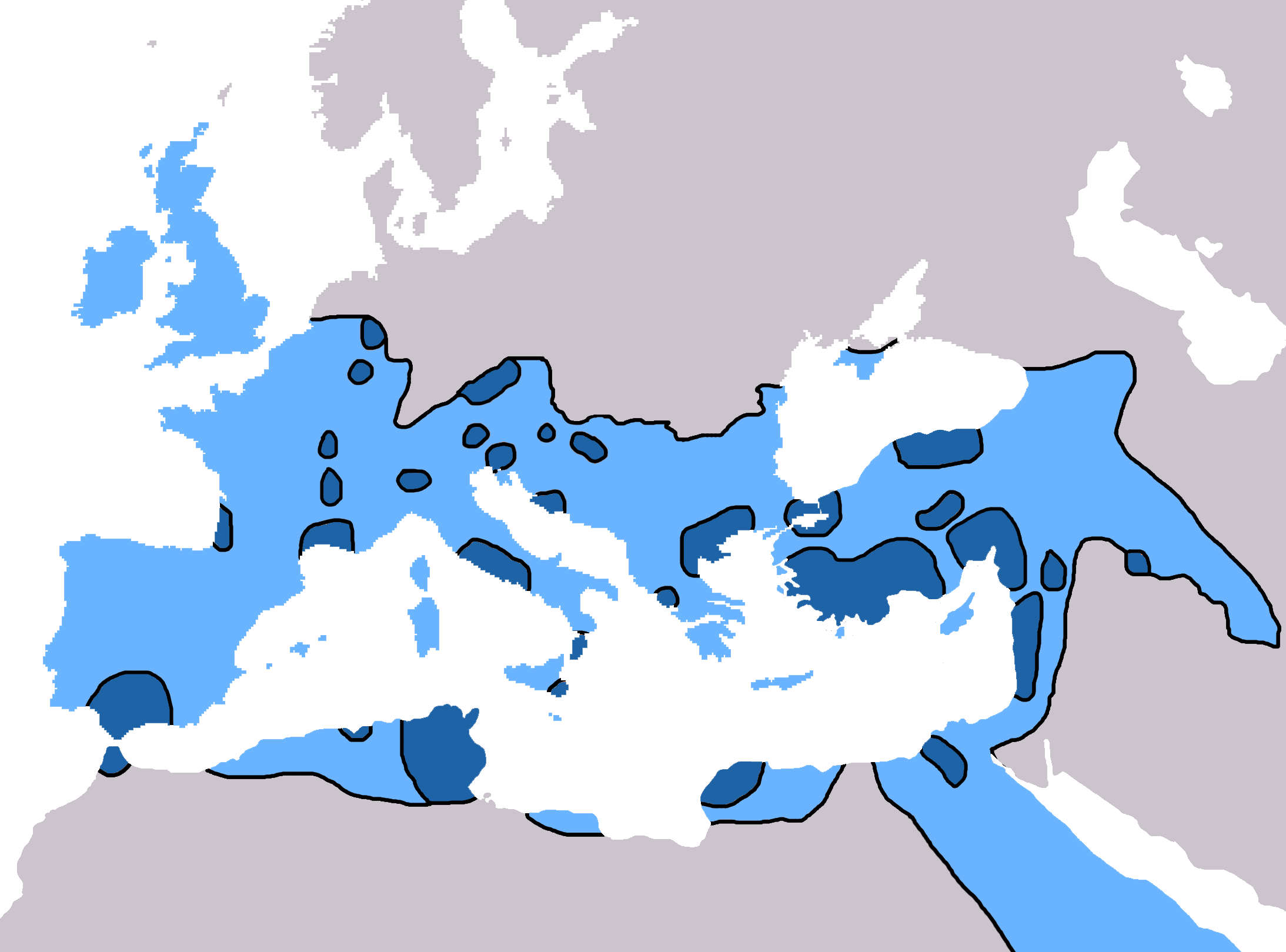

The ante-Nicene period (literally meaning "before Nicaea") was the period following the Apostolic Age down to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. By the beginning of the Nicene period, the Christian faith had spread throughout

Western Europe and the

Mediterranean Basin, and to

North Africa and the East. A more formal Church structure grew out of the early communities, and various Christian doctrines developed. Christianity grew apart from Judaism, creating its own identity by an increasingly harsh

rejection of Judaism and of

Jewish practices.

Developing church structure

The number of Christians grew by approximately 40% per decade during the first and second centuries.

In the post-Apostolic church a hierarchy of clergy gradually emerged as overseers of urban Christian populations took on the form of ''

episkopoi'' (overseers, the origin of the terms bishop and episcopal) and ''

presbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros,'' which means elder or senior, although many in the Christian antiquity would understand ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning as ...

s'' (

elders; the origin of the term

priest) and then ''

deacons

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Churc ...

'' (servants). But this emerged slowly and at different times in different locations.

Clement, a 1st-century bishop of Rome, refers to the leaders of the Corinthian church in

his epistle to Corinthians as bishops and presbyters interchangeably. The New Testament writers also use the terms overseer and elders interchangeably and as synonyms.

Variant Christianities

The Ante-Nicene period saw the rise of a great number of Christian

sects,

cult

In modern English, ''cult'' is usually a pejorative term for a social group that is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or its common interest in a particular personality, object, or goal. Thi ...

s, and

movements

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

with strong unifying characteristics which were lacking in the apostolic period. They had different interpretations of the

Bible, particularly regarding

theological doctrines such as the

divinity of Jesus

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

and the nature of the

Trinity. Many of the variations which existed during this time defy neat categorizations, because various forms of Christianity interacted in a complex fashion in order to form the dynamic character of Christianity which existed during this era. The Post-Apostolic period was diverse both in terms of beliefs and practices. In addition to the broad spectrum of general branches of Christianity, there was constant change and diversity that variably resulted in both internecine conflicts and syncretic adoption.

Development of the biblical canon

The

letters of the Apostle Paul sent to the

early Christian communities in

Rome,

Greece, and

Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

were circulating in collected form by the end of the 1st century. By the early 3rd century, there existed

a set of early Christian writings similar to the current

New Testament,

though there were still disputes over the canonicity of texts such as the

Epistle to the Hebrews

The Epistle to the Hebrews ( grc, Πρὸς Ἑβραίους, Pros Hebraious, to the Hebrews) is one of the books of the New Testament.

The text does not mention the name of its author, but was traditionally attributed to Paul the Apostle. Most ...

, the

Epistle of James, the

First and

Second Epistle of Peter, the

First Epistle of John, and the

Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament (and consequently the final book of the Christian Bible). Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: , meaning "unveiling" or "revelation". The Book of ...

. By the 4th century, there existed unanimity in the

Latin Church

, native_name_lang = la

, image = San Giovanni in Laterano - Rome.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, alt = Façade of the Archbasilica of St. John in Lateran

, caption = Archbasilica of Saint Joh ...

concerning the canonical texts included in the New Testament canon, and by the 5th century the

Eastern Churches, with a few exceptions, had come to accept the Book of Revelation and thus had come into harmony on the matter of the canon.

Proto-Orthodox writings

As

Christianity spread throughout the

provinces of the Roman Empire and beyond its borders, it acquired certain members from high-ranking social classes and well-educated circles of the

Hellenistic world; they sometimes became bishops. They produced two sorts of works, theological and

apologetic

Apologetics (from Greek , "speaking in defense") is the religious discipline of defending religious doctrines through systematic argumentation and discourse. Early Christian writers (c. 120–220) who defended their beliefs against critics and ...

, the latter being works aimed at defending the Christian faith by using reason,

philosophy, and

sacred scriptures to refute arguments against the veracity of Christianity. These authors are known as the

Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical p ...

, and the study of their lives and writings is called "

patristics". Notable early Church Fathers include

Ignatius of Antioch,

Polycarp,

Justin Martyr,

Irenaeus

Irenaeus (; grc-gre, Εἰρηναῖος ''Eirēnaios''; c. 130 – c. 202 AD) was a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the dev ...

,

Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria ( grc , Κλήμης ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; – ), was a Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen an ...

,

Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of La ...

, and

Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an early Christian scholar, ascetic, and theolo ...

.

Early Christian art

Early Christian art and architecture

Early Christian art and architecture or Paleochristian art is the art produced by Christians or under Christian patronage from the earliest period of Christianity to, depending on the definition used, sometime between 260 and 525. In practice, i ...

emerged relatively late and the first known Christian images emerge from about 200 AD, although there is some literary evidence that small domestic images were used earlier. The oldest known Christian paintings are from the Roman

catacombs

Catacombs are man-made subterranean passageways for religious practice. Any chamber used as a burial place is a catacomb, although the word is most commonly associated with the Roman Empire.

Etymology and history

The first place to be referred ...

, dated to about 200, and the oldest Christian sculptures are from

sarcophagi, dating to the beginning of the 3rd century.

The early rejection of images, and the necessity to hide Christian practice from persecution, left behind few written records regarding early Christianity and its evolution.

[Andre Grabar, p. 7]

Persecutions and legalization

There was no empire-wide

persecution of Christians until the reign of

Decius in the 3rd century.

[Martin, D. 2010]

"The "Afterlife" of the New Testament and Postmodern Interpretation

lecture transcript

). Yale University. The last and most severe persecution organised by the imperial Roman authorities was the

Diocletianic Persecution

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rights ...

, 303–311.

The

Edict of Serdica was issued in 311 by the Roman Emperor

Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across the D ...

, officially ending the persecution of Christians in the East. With the promulgation of the

Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

(313), in which the Roman Emperors

Constantine the Great and

Licinius

Valerius Licinianus Licinius (c. 265 – 325) was Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan, AD 313, that granted official toleration to ...

legalized the Christian religion, persecution of Christians by the Roman state ceased.

The

Kingdom of Armenia became

the first country in the world to establish Christianity as its

state religion when, in an event traditionally dated to the year 301,

Gregory the Illuminator

Gregory the Illuminator ( Classical hy, Գրիգոր Լուսաւորիչ, reformed: Գրիգոր Լուսավորիչ, ''Grigor Lusavorich'';, ''Gregorios Phoster'' or , ''Gregorios Photistes''; la, Gregorius Armeniae Illuminator, cu, Svyas ...

convinced

Tiridates III, the King of Armenia, to convert to Christianity.

Late antiquity (325–476)

Influence of Constantine

How much Christianity the Roman Emperor

Constantine adopted at this point is difficult to discern,

[R. Gerberding and J. H. Moran Cruz, ''Medieval Worlds'' (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004) p. 55] but his accession was a turning point for the Christian Church. He supported the Church financially, built various

basilicas

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica is a large public building with multiple functions, typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building gave its nam ...

, granted privileges (e.g., exemption from certain taxes) to clergy, promoted Christians to some high offices, and returned confiscated property. Constantine played an active role in the leadership of the Church. In 316, he acted as a judge in a North African dispute concerning the

Donatist controversy. More significantly, in 325 he summoned the Council of Nicaea, the first

ecumenical council. He thus established a precedent for the emperor as responsible to

God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

for the spiritual health of his subjects, and thus with a duty to maintain

orthodoxy. He was to enforce doctrine, root out

heresy, and uphold ecclesiastical unity.

The successor of Constantine's son, his nephew

Julian, under the influence of his adviser

Mardonius,

renounced Christianity and embraced a

Neoplatonic and mystical form of

Greco-Roman Paganism, shocking the Christian establishment.

He attempted to

revive Greco-Roman Paganism in the Roman Empire and began by reopening the Pagan temples, modifying them to resemble Christian traditions, such as the episcopal structure and public charity (previously unknown in the Greco-Roman religion). Julian's short reign ended when he was wounded in the

Battle of Samarra

The Battle of Samarra took place in June 363, during the invasion of the Sasanian Empire by the Roman Emperor Julian. After marching his army to the gates of Ctesiphon and failing to take the city, Julian, realizing his army was low on provisio ...

and died days later during the

expedition against the Sasanian Empire (363).

Arianism and the first ecumenical councils

An increasingly popular

Nontrinitarian Christological doctrine that spread throughout the Roman Empire from the 4th century onwards was

Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

,

founded by the Christian presbyter

Arius

Arius (; grc-koi, Ἄρειος, ; 250 or 256 – 336) was a Cyrenaic presbyter, ascetic, and priest best known for the doctrine of Arianism. His teachings about the nature of the Godhead in Christianity, which emphasized God the Father's un ...

from

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

,

Egypt, which taught that Jesus Christ is a creature distinct from and subordinate to

God the Father.

Although the Arian doctrine was condemned as

heresy and eventually eliminated by the State church of the Roman Empire, it remained popular underground for some time. In the late 4th century,

Ulfilas

Ulfilas (–383), also spelled Ulphilas and Orphila, all Latinized forms of the unattested Gothic form *𐍅𐌿𐌻𐍆𐌹𐌻𐌰 Wulfila, literally "Little Wolf", was a Goth of Cappadocian Greek descent who served as a bishop and missio ...

, a Roman Arian bishop, was appointed as the first Christian missionary to the

Goths, the Germanic peoples in much of Europe at the borders of and within the Roman Empire.

, firmly establishing the faith among many of the Germanic tribes, thus helping to keep them culturally and religiously distinct from

Chalcedonian Christians.

[Padberg 1998, 26]

During this age, the

first ecumenical councils were convened. They were mostly concerned with Christological and theological disputes. The First Council of Nicaea (325) and the

First Council of Constantinople (381) resulted in condemnation of Arian teachings as heresy and produced the Nicene Creed.

Christianity as Roman state religion

On 27 February 380, with the

Edict of Thessalonica put forth under

Theodosius I,

Gratian, and

Valentinian II, the Roman Empire officially adopted Trinitarian Christianity as its state religion. Prior to this date,

Constantius II and

Valens had personally favoured Arian or

Semi-Arian

Semi-Arianism was a position regarding the relationship between God the Father and the Son of God, adopted by some 4th-century Christians. Though the doctrine modified the teachings of Arianism, it still rejected the doctrine that Father, Son, ...

forms of Christianity, but Valens' successor Theodosius I supported the Trinitarian doctrine as expounded in the Nicene Creed.

After its establishment, the Church adopted the same organisational boundaries as the Empire: geographical provinces, called

dioceses, corresponding to imperial government territorial divisions. The bishops, who were located in major urban centres as in pre-legalisation tradition, thus oversaw each diocese. The bishop's location was his "seat", or "

see". Among the sees,

five

5 is a number, numeral, and glyph.

5, five or number 5 may also refer to:

* AD 5, the fifth year of the AD era

* 5 BC, the fifth year before the AD era

Literature

* ''5'' (visual novel), a 2008 visual novel by Ram

* ''5'' (comics), an awa ...

came to hold special eminence:

Rome,

Constantinople,

Jerusalem,

Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

, and

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

. The prestige of most of these sees depended in part on their apostolic founders, from whom the bishops were therefore the spiritual successors. Though the bishop of Rome was still held to be the

First among equals, Constantinople was second in precedence as the new capital of the empire.

Theodosius I decreed that others not believing in the preserved "faithful tradition", such as the Trinity, were to be considered to be practitioners of illegal heresy, and in 385, this resulted in the first case of the state, not Church, infliction of capital punishment on a heretic, namely

Priscillian

Priscillian (in Latin: ''Priscillianus''; Gallaecia, - Augusta Treverorum, Gallia Belgica, ) was a wealthy nobleman of Roman Hispania who promoted a strict form of Christian asceticism. He became bishop of Ávila in 380. Certain practices of his ...

.

[ Review of Church policies towards heresy, including capital punishment (see Synod at Saragossa).]

Church of the East and the Sasanian Empire

During the early 5th century, the

School of Edessa

The School of Edessa ( syr, ܐܣܟܘܠܐ ܕܐܘܪܗܝ) was a Christian theological school of great importance to the Syriac-speaking world. It had been founded as long ago as the 2nd century by the kings of the Abgar dynasty. In 363, Nisibis fell ...

had taught a Christological perspective stating that Christ's divine and human nature were distinct persons. A particular consequence of this perspective was that

Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also call ...

could not be properly called the mother of God but could only be considered the mother of Christ. The most widely known proponent of this viewpoint was the Patriarch of Constantinople

Nestorius. Since referring to Mary as the mother of God had become popular in many parts of the Church this became a divisive issue.

The Roman Emperor

Theodosius II called for the

Council of Ephesus (431), with the intention of settling the issue. The council ultimately rejected Nestorius' view. Many churches who followed the Nestorian viewpoint broke away from the Roman Church, causing a major schism. The Nestorian churches were persecuted, and many followers fled to the

Sasanian Empire where they were accepted. The Sasanian (Persian) Empire had many Christian converts early in its history, tied closely to the

Syriac branch of Christianity. The Sasanian Empire was officially

Zoroastrian and maintained a strict adherence to this faith, in part to distinguish itself from the religion of the Roman Empire (originally the Greco-Roman Paganism and then Christianity). Christianity became tolerated in the Sasanian Empire, and as the Roman Empire increasingly exiled heretics during the 4th and 6th centuries, the Sasanian Christian community grew rapidly.

[''Culture and customs of Iran'', p. 61] By the end of the 5th century, the Persian Church was firmly established and had become independent of the Roman Church. This church evolved into what is today known as the

Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

.

In 451, the

Council of Chalcedon was held to further clarify the Christological issues surrounding Nestorianism. The council ultimately stated that Christ's divine and human nature were separate but both part of a single entity, a viewpoint rejected by many churches who called themselves

miaphysites

Miaphysitism is the Christological doctrine that holds Jesus, the "Incarnate Word, is fully divine and fully human, in one 'nature' (''physis'')." It is a position held by the Oriental Orthodox Churches and differs from the Chalcedonian positio ...

. The resulting schism created a communion of churches, including the Armenian, Syrian, and Egyptian churches. Though efforts were made at reconciliation in the next few centuries, the schism remained permanent, resulting in what is today known as

Oriental Orthodoxy.

Monasticism

Monasticism is a form of

asceticism

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

whereby one renounces worldly pursuits and goes off alone as a

hermit or joins a tightly organized community. It began early in the Christian Church as a family of similar traditions, modelled upon Scriptural examples and ideals, and with roots in certain strands of Judaism.

John the Baptist is seen as an archetypical monk, and monasticism was inspired by the organisation of the Apostolic community as recorded in

Acts 2:42–47.

Notable Christian authors of

Late Antiquity such as

Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an early Christian scholar, ascetic, and theolo ...

,

St Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian priest, confessor, theologian, and historian; he is com ...

,

John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of ab ...

, and

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

, interpreted meanings of the

Biblical texts within a highly asceticized religious environment.

Scriptural examples of asceticism could be found in the lives of

John the Baptist,

Jesus Christ, the

twelve apostles, and

Paul the Apostle

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

.

The

Dead Sea Scrolls revealed ascetic practices of the ancient Jewish sect of

Essenes who took vows of abstinence to prepare for a holy war. An emphasis on an ascetic religious life was evident in both

early Christian writings (''see'':

Philokalia

The ''Philokalia'' ( grc, φιλοκαλία, lit=love of the beautiful, from ''philia'' "love" and ''kallos'' "beauty") is "a collection of texts written between the 4th and 15th centuries by spiritual masters" of the mystical hesychast trad ...

) and practices (''see'':

Hesychasm). Other Christian practitioners of asceticism include saints such as

Paul the Hermit

Paul of Thebes (; , ''Paûlos ho Thēbaîos''; ; c. 227 – c. 341), commonly known as Paul the First Hermit or Paul the Anchorite, was an Egyptian saint regarded as the first Christian hermit, who was claimed to have lived alone in the deser ...

,

Simeon Stylites

Simeon Stylites or Symeon the Stylite syc, ܫܡܥܘܢ ܕܐܣܛܘܢܐ ', Koine Greek ', ar, سمعان العمودي ' (c. 390 – 2 September 459) was a Syrian Christian ascetic, who achieved notability by living 37 years on a smal ...

,

David of Wales,

John of Damascus, and

Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, better known as Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Francesco d'Assisi; – 3 October 1226), was a mystic Italian Catholic friar, founder of the Franciscans, and one of the most venerated figures in Christian ...

.

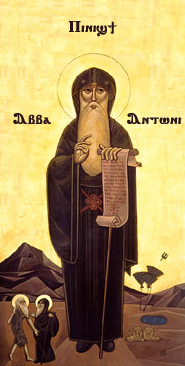

The deserts of the

Middle East were at one time inhabited by thousands of male and female Christian ascetics, hermits and

anchorite

In Christianity, an anchorite or anchoret (female: anchoress) is someone who, for religious reasons, withdraws from secular society so as to be able to lead an intensely prayer-oriented, ascetic, or Eucharist-focused life. While anchorites a ...

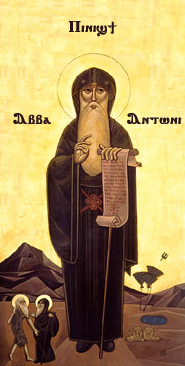

s, including St.

Anthony the Great

Anthony the Great ( grc-gre, Ἀντώνιος ''Antṓnios''; ar, القديس أنطونيوس الكبير; la, Antonius; ; c. 12 January 251 – 17 January 356), was a Christian monk from Egypt, revered since his death as a saint. He is d ...

(otherwise known as St. Anthony of the Desert), St.

Mary of Egypt, and St.

Simeon Stylites

Simeon Stylites or Symeon the Stylite syc, ܫܡܥܘܢ ܕܐܣܛܘܢܐ ', Koine Greek ', ar, سمعان العمودي ' (c. 390 – 2 September 459) was a Syrian Christian ascetic, who achieved notability by living 37 years on a smal ...

, collectively known as the

Desert Fathers and

Desert Mothers

Desert Mothers is a neologism, coined in feminist theology in analogy to Desert Fathers, for the ''ammas'' or female Christian ascetics living in the desert of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria in the 4th and 5th centuries AD. They typically lived in t ...

. In 963 an association of monasteries called ''Lavra'' was formed on

Mount Athos, in

Eastern Orthodox tradition.

This became the most important center of orthodox Christian ascetic groups in the centuries that followed.

In the modern era, Mount Athos and

Meteora

The Meteora (; el, Μετέωρα, ) is a rock formation in central Greece hosting one of the largest and most precipitously built complexes of Eastern Orthodox monasteries, second in importance only to Mount Athos.Sofianos, D.Z.: "Metéora". ...

have remained a significant center.

Eremitic monks, or hermits, live in solitude, whereas

cenobitic

Cenobitic (or coenobitic) monasticism is a monastic tradition that stresses community life. Often in the West the community belongs to a religious order, and the life of the cenobitic monk is regulated by a religious rule, a collection of prece ...

s live in communities, generally in a

monastery, under a rule (or code of practice) and are governed by an

abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The fe ...

. Originally, all Christian monks were hermits, following the example of

Anthony the Great

Anthony the Great ( grc-gre, Ἀντώνιος ''Antṓnios''; ar, القديس أنطونيوس الكبير; la, Antonius; ; c. 12 January 251 – 17 January 356), was a Christian monk from Egypt, revered since his death as a saint. He is d ...

. However, the need for some form of organised spiritual guidance lead

Pachomius

Pachomius (; el, Παχώμιος ''Pakhomios''; ; c. 292 – 9 May 348 AD), also known as Saint Pachomius the Great, is generally recognized as the founder of Christian cenobitic monasticism. Coptic churches celebrate his feast day on 9 May, ...

in 318 to organise his many followers in what was to become the first monastery. Soon, similar institutions were established throughout the Egyptian desert as well as the rest of the eastern half of the Roman Empire. Women were especially attracted to the movement. Central figures in the development of monasticism were

Basil the Great

Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great ( grc, Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας, ''Hágios Basíleios ho Mégas''; cop, Ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲃⲁⲥⲓⲗⲓⲟⲥ; 330 – January 1 or 2, 379), was a bishop of Cae ...

in the East and, in the West,

Benedict

Benedict may refer to:

People Names

*Benedict (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Benedict (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Religious figures

* Pope Benedict I (died 579), head of the Catholic Ch ...

, who created the

Rule of Saint Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Ru ...

, which would become the most common rule throughout the Middle Ages and the starting point for other monastic rules.

Early Middle Ages (476–842)

The transition into the

Early Middle Ages was a gradual and localised process. Rural areas rose as power centres whilst urban areas declined. Although a greater number of Christians remained in the

East (Greek areas), important developments were underway in the

West (Latin areas), and each took on distinctive shapes. The

bishops of Rome, the popes, were forced to adapt to drastically changing circumstances. Maintaining only nominal allegiance to the emperor, they were forced to negotiate balances with the "barbarian rulers" of the former Roman provinces. In the East, the Church maintained its structure and character and evolved more slowly.

Western missionary expansion

The stepwise loss of

Western Roman Empire dominance, replaced with

foederati and

Germanic kingdoms, coincided with early missionary efforts into areas not controlled by the

collapsing empire. As early as in the 5th century, missionary activities from

Roman Britain into the Celtic areas (

Scotland,

Ireland, and

Wales) produced competing early traditions of

Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity ( kw, Kristoneth; cy, Cristnogaeth; gd, Crìosdaidheachd; gv, Credjue Creestee/Creestiaght; ga, Críostaíocht/Críostúlacht; br, Kristeniezh; gl, Cristianismo celta) is a form of Christianity that was common, or held ...

, that was later reintegrated under the Church in Rome. Prominent missionaries in Northwestern Europe of the time were the Christian saints

Patrick,

Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is tod ...

, and

Columbanus

Columbanus ( ga, Columbán; 543 – 21 November 615) was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries after 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil Abbey in present-day France and Bobbio Abbey in p ...

. The

Anglo-Saxon tribes that invaded Southern Britain some time after the Roman abandonment were initially Pagans but were converted to Christianity by

Augustine of Canterbury

Augustine of Canterbury (early 6th century – probably 26 May 604) was a monk who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English" and a founder of the English Church.Delaney '' ...

on the mission of

Pope Gregory the Great

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregoria ...

. Soon becoming a missionary centre, missionaries such as

Wilfrid,

Willibrord

Willibrord (; 658 – 7 November AD 739) was an Anglo-Saxon missionary and saint, known as the "Apostle to the Frisians" in the modern Netherlands. He became the first bishop of Utrecht and died at Echternach, Luxembourg.

Early life

His fathe ...

,

Lullus

Saint Lullus (Lull or Lul) (born about 710 AD in Wessex, died 16 October 786 in Hersfeld) was the first permanent archbishop of Mainz, succeeding Saint Boniface, and first abbot of the Benedictine Hersfeld Abbey. He is historiographically conside ...

, and

Boniface

Boniface, OSB ( la, Bonifatius; 675 – 5 June 754) was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations of ...

converted their

Saxon relatives in

Germania.

The largely Christian

Gallo-Roman inhabitants of

Gaul (modern France and Belgium) were overrun by the

Franks in the early 5th century. The native inhabitants were persecuted until the Frankish King

Clovis I

Clovis ( la, Chlodovechus; reconstructed Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first king of the Franks to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a single k ...

converted from Paganism to

Roman Catholicism in 496. Clovis insisted that his fellow nobles follow suit, strengthening his newly established kingdom by uniting the faith of the rulers with that of the ruled.

[Janet L. Nelson, ''The Frankish world, 750–900'' (1996)] After the rise of the

Frankish Kingdom and the stabilizing political conditions, the Western part of the Church increased the missionary activities, supported by the

Merovingian dynasty as a means to pacify troublesome neighbour peoples. After the foundation of a church in

Utrecht by

Willibrord

Willibrord (; 658 – 7 November AD 739) was an Anglo-Saxon missionary and saint, known as the "Apostle to the Frisians" in the modern Netherlands. He became the first bishop of Utrecht and died at Echternach, Luxembourg.

Early life

His fathe ...

, backlashes occurred when the Pagan

Frisian King Radbod destroyed many Christian centres between 716 and 719. In 717, the English missionary

Boniface

Boniface, OSB ( la, Bonifatius; 675 – 5 June 754) was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations of ...

was sent to aid Willibrord, re-establishing churches in Frisia and continuing missions in Germany.

During the late 8th century,

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Em ...

used mass killings in order to subjugate the Pagan Saxons and

forcibly compel them to accept Christianity.

Rashidun Caliphate

Since they are considered "

People of the Book" in the

Islamic religion, Christians under Muslim rule were subjected to the status of ''

dhimmi

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligati ...

'' (along with

Jews,

Samaritans,

Gnostics,

Mandeans, and

Zoroastrians), which was inferior to the status of Muslims.

Christians and other religious minorities thus faced

religious discrimination and

persecution in that they were banned from

proselytising (for Christians, it was forbidden to

evangelize or spread Christianity) in the

lands invaded by the Arab Muslims on pain of death, they were banned from bearing arms, undertaking certain professions, and were obligated to dress differently in order to distinguish themselves from Arabs.

Under the

Islamic law (''sharīʿa''), Non-Muslims were obligated to pay the ''

jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in Isl ...

'' and ''

kharaj'' taxes,

together with periodic heavy

ransom

Ransom is the practice of holding a prisoner or item to extort money or property to secure their release, or the sum of money involved in such a practice.

When ransom means "payment", the word comes via Old French ''rançon'' from Latin ''re ...

levied upon Christian communities by Muslim rulers in order to fund military campaigns, all of which contributed a significant proportion of income to the Islamic states while conversely reducing many Christians to poverty, and these financial and social hardships

forced many Christians to convert to Islam.

Christians unable to pay these taxes were forced to surrender their children to the Muslim rulers as payment who would

sell them as slaves to Muslim households where they

were forced to convert to Islam.

According to the tradition of the

Syriac Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = syc

, image = St_George_Syriac_orthodox_church_in_Damascus.jpg

, imagewidth = 250

, alt = Cathedral of Saint George

, caption = Cathedral of Saint George, Damascu ...

, the

Muslim conquest of the Levant was a relief for Christians oppressed by the Western Roman Empire.

Michael the Syrian

Michael the Syrian ( ar, ميخائيل السرياني, Mīkhaʾēl el Sūryani:),( syc, ܡܺܝܟ݂ܳܐܝܶܠ ܣܽܘܪܝܳܝܳܐ, Mīkhoʾēl Sūryoyo), died 1199 AD, also known as Michael the Great ( syr, ܡܺܝܟ݂ܳܐܝܶܠ ܪܰܒ݁ܳܐ, ...

,

patriarch of Antioch

Patriarch of Antioch is a traditional title held by the bishop of Antioch (modern-day Antakya, Turkey). As the traditional "overseer" (ἐπίσκοπος, ''episkopos'', from which the word ''bishop'' is derived) of the first gentile Christian c ...

, wrote later that the Christian God had "raised from the south the

children of Ishmael to deliver us by them from the hands of the Romans".

Various Christian communities in the regions of

Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East J ...

,

Syria,

Lebanon, and

Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

resented either towards the governance of the Western Roman Empire or that of the Byzantine Empire, and therefore preferred to live under more favourable economic and political conditions as ''dhimmi'' under the Muslim rulers.

However, modern historians also recognize that the Christian populations living in the

lands invaded by the Arab Muslim armies between the 7th and 10th centuries AD suffered

religious persecution,

religious violence, and

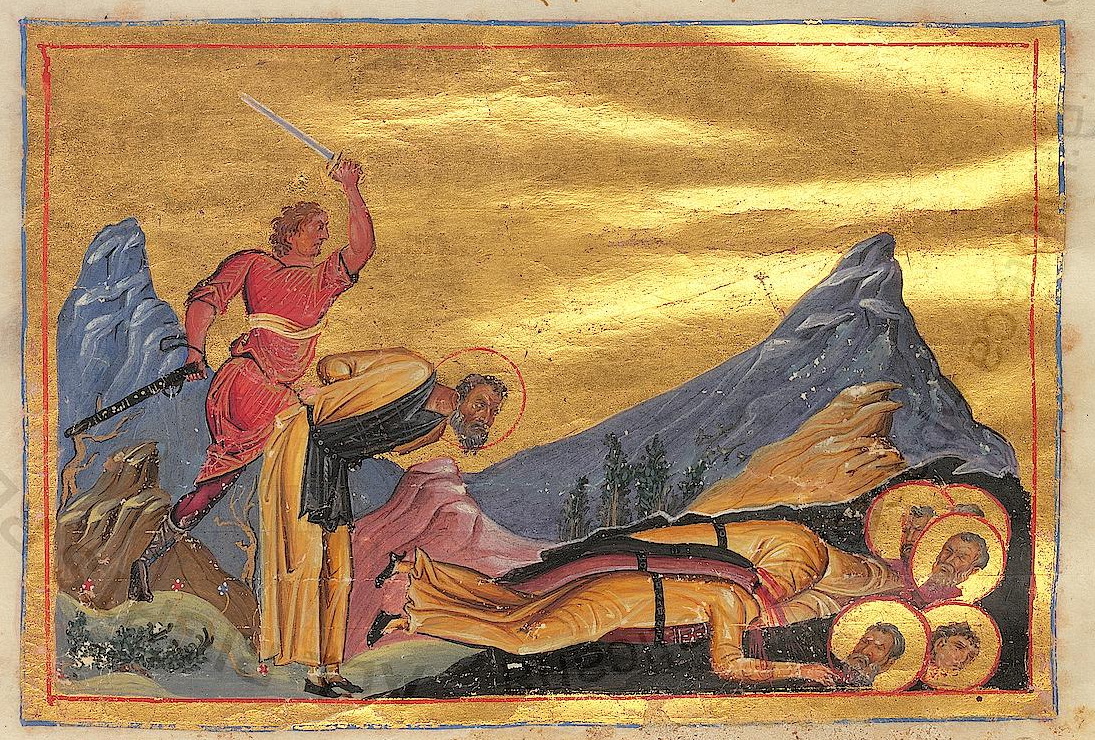

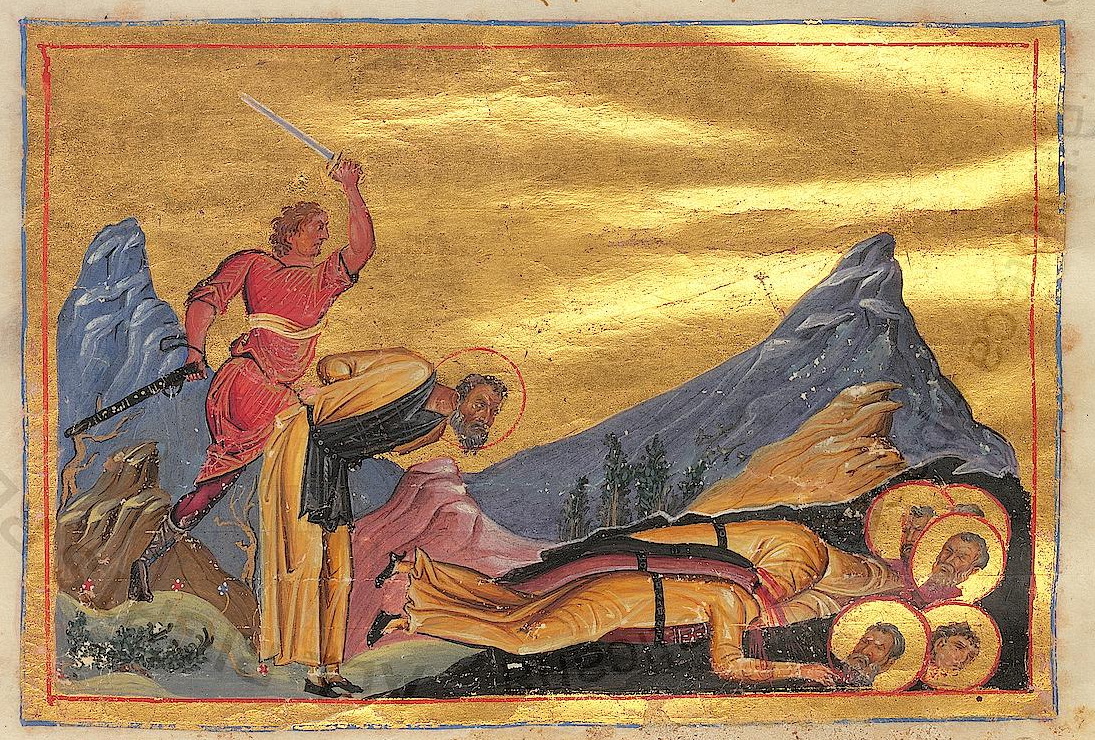

martyrdom

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external ...

multiple times at the hands of Arab Muslim officials and rulers;

many

were executed under the Islamic death penalty for defending their Christian faith through dramatic acts of resistance such as refusing to convert to Islam,

repudiation of the Islamic religion and subsequent

reconversion to Christianity, and

blasphemy towards Muslim beliefs.

Umayyad Caliphate

According to the

Ḥanafī

The Hanafi school ( ar, حَنَفِية, translit=Ḥanafiyah; also called Hanafite in English), Hanafism, or the Hanafi fiqh, is the oldest and one of the four traditional major Sunni schools (maddhab) of Islamic Law (Fiqh). It is named afte ...

school of

Islamic law (''sharīʿa''), the testimony of a Non-Muslim (such as a Christian or a Jew) was not considered valid against the testimony of a Muslim in legal or civil matters. Historically, in

Islamic culture

Islamic culture and Muslim culture refer to cultural practices which are common to historically Islamic people. The early forms of Muslim culture, from the Rashidun Caliphate to the early Umayyad period and the early Abbasid period, were predom ...

and traditional Islamic law

Muslim women have been forbidden from marrying Christian or Jewish men, whereas Muslim men have been permitted to marry Christian or Jewish women (''see'':

Interfaith marriage in Islam

Interfaith marriages are recognized between Muslims and Non-Muslim "People of the Book" (usually enumerated as Jews, Christians, and Sabians). According to the traditional interpretation of Islamic law (''sharīʿa''), a Muslim man is allowed to m ...

). Christians under Islamic rule had the right to convert to Islam or any other religion, while conversely a ''

murtad

Apostasy in Islam ( ar, ردة, or , ) is commonly defined as the abandonment of Islam by a Muslim, in thought, word, or through deed. An apostate from Islam is referred to by using the Arabic and Islamic term ''murtād'' (). It includes no ...

'', or an

apostate from Islam, faced severe penalties or even ''

hadd'', which could include the

Islamic death penalty.

In general, Christians subject to Islamic rule were allowed to practice their religion with some notable limitations stemming from the apocryphal ''

Pact of Umar

The Pact of Umar (also known as the Covenant of Umar, Treaty of Umar or Laws of Umar; ar, شروط عمر or or ), is a treaty between the Muslims and the non-Muslim inhabitants of either Syria, Mesopotamia, or Jerusalem that later gained a c ...

''. This treaty, supposedly enacted in 717 AD, forbade Christians from publicly displaying the cross on church buildings, from summoning congregants to prayer with a bell, from re-building or repairing churches and monasteries after they had been destroyed or damaged, and imposed other restrictions relating to occupations, clothing, and weapons. The Umayyad Caliphate persecuted many

Berber Christians

The name Early African Church is given to the Christian communities inhabiting the region known politically as Roman Africa, and comprised geographically somewhat around the area of the Roman Diocese of Africa, namely: the Mediterranean littoral be ...

in the 7th and 8th centuries AD, who slowly converted to Islam.

In

Umayyad al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the Mu ...

(the

Iberian Peninsula), the

Mālikī

The ( ar, مَالِكِي) school is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as primary s ...

school of Islamic law was the most prevalent.

The martyrdoms of forty-eight Christian martyrs that took place in the

Emirate of Córdoba

The Emirate of Córdoba ( ar, إمارة قرطبة, ) was a medieval Islamic kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula. Its founding in the mid-eighth century would mark the beginning of seven hundred years of Muslim rule in what is now Spain and Po ...

between 850 and 859 AD

are recorded in the

hagiographical treatise written by the Iberian Christian and Latinist scholar

Eulogius of Córdoba

Saint Eulogius of Córdoba ( es, San Eulogio de Córdoba (died 11 March 857) was one of the Martyrs of Córdoba. He flourished during the reigns of the Cordovan emirs Abd-er-Rahman II and Muhammad I (mid-9th century).

Background

In the ninth ...

.

The

Martyrs of Córdoba

The Martyrs of Córdoba were forty-eight Christian martyrs who were executed under the rule of Muslim administration in Al-Andalus (name of the Iberian Peninsula under the Islamic rule). The hagiographical treatise written by the Iberian Christ ...

were executed under the rule of

Abd al-Rahman II

Abd ar-Rahman II () (792–852) was the fourth ''Umayyad'' Emir of Córdoba in al-Andalus from 822 until his death. A vigorous and effective frontier warrior, he was also well known as a patron of the arts.

Abd ar-Rahman was born in Toledo, the ...

and

Muhammad I, and Eulogius' hagiography describes in detail the executions of the martyrs for capital violations of Islamic law, including

apostasy

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that i ...

and

blasphemy

Blasphemy is a speech crime and religious crime usually defined as an utterance that shows contempt, disrespects or insults a deity, an object considered sacred or something considered inviolable. Some religions regard blasphemy as a religio ...

.

Abbasid Caliphate

Eastern Christian scientists and scholars of the medieval Islamic world (particularly

Jacobite and

Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian N ...

Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

) contributed to the Arab

Islamic civilization during the reign of the

Umayyad and the

Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

, by translating works of

Greek philosophers

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

to

Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages ...

and afterwards, to

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

. They also excelled in philosophy, science, theology, and medicine. And the personal

physicians

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

of the Abbasid Caliphs were often

Assyrian

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyri ...

Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

such as the long serving

Bukhtishu

The Bukhtīshūʿ (or Boḵtīšūʿ) were a family of either Persian or Nestorian Christian physicians from the 7th, 8th, and 9th centuries, spanning six generations and 250 years. The Middle Persian-Syriac name which can be found as early as at ...

dynast

The

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

was less tolerant of Christianity than had been the

Umayyad caliphs.

Nonetheless, Christian officials continued to be employed in the government, and the Christians of the

Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

were often tasked with the translation of

Ancient Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

and

Greek mathematics

Greek mathematics refers to mathematics texts and ideas stemming from the Archaic through the Hellenistic and Roman periods, mostly extant from the 7th century BC to the 4th century AD, around the shores of the Eastern Mediterranean. Greek mathe ...

.

The writings of

al-Jahiz

Abū ʿUthman ʿAmr ibn Baḥr al-Kinānī al-Baṣrī ( ar, أبو عثمان عمرو بن بحر الكناني البصري), commonly known as al-Jāḥiẓ ( ar, links=no, الجاحظ, ''The Bug Eyed'', born 776 – died December 868/Jan ...

attacked Christians for being too prosperous, and indicates they were able to ignore even those restrictions placed on them by the state.

In the late 9th century, the

patriarch of Jerusalem,

Theodosius Theodosius ( Latinized from the Greek "Θεοδόσιος", Theodosios, "given by god") is a given name. It may take the form Teodósio, Teodosie, Teodosije etc. Theodosia is a feminine version of the name.

Emperors of ancient Rome and Byzantium

...

, wrote to his colleague the

patriarch of Constantinople Ignatios that "they are just and do us no wrong nor show us any violence".

Elias of Heliopolis

Elias of Heliopolis (759–779), also called Elias of Damascus, was a Syrian carpenter and Christian martyr revered as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox and Syriac Orthodox churches. He is known from a Greek hagiography.

Dates

The '' Prosopographie ...

, having moved to Damascus from Heliopolis (

Ba'albek), was accused of apostasy from Christianity after attending a party held by a Muslim Arab, and was forced to flee Damascus for his hometown, returning eight years later, where he was recognized and imprisoned by the "''

eparch

Eparchy ( gr, ἐπαρχία, la, eparchía / ''overlordship'') is an ecclesiastical unit in Eastern Christianity, that is equivalent to a diocese in Western Christianity. Eparchy is governed by an ''eparch'', who is a bishop. Depending on the ...

''", probably the jurist

al-Layth ibn Sa'd

Al-Layth ibn Saʿd ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Fahmī al-Qalqashandī ( ar, الليث بن سعد بن عبد الرحمن الفهمي القلقشندي) was the chief representative, imam, and eponym of the Laythi school of Islamic Jurisprude ...

.

After refusing to convert to Islam under torture, he was brought before the Damascene ''emir'' and relative of the caliph

al-Mahdi

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Manṣūr ( ar, أبو عبد الله محمد بن عبد الله المنصور; 744 or 745 – 785), better known by his regnal name Al-Mahdī (, "He who is guided by God"), was the third Abba ...

(),

Muhammad ibn-Ibrahim, who promised good treatment if Elias would convert.

On his repeated refusal, Elias was tortured and beheaded and his body burnt, cut up, and thrown into the river Chrysorrhoes (the

Barada

, name_etymology = From ''barid'', meaning 'cold' in Semitic languages

, image = Barada river in Damascus (April 2009).jpg

, image_size = 300

, image_caption = Barada river in Damascus near the Four Seasons Hote ...

) in 779 AD.

According to the ''Synaxarion of Constantinople'', the ''hegumenos''

Michael of Zobe and thirty-six of his monks at the Monastery of Zobe near Sebasteia (

Sivas) were killed by a raid on the community.

The perpetrator was the "''emir'' of the

Hagarenes

Hagarenes ( grc, Ἀγαρηνοί , syc, ܗܓܪܝܐ or , arm, Հագարացի), is a term widely used by early Syriac, Greek, Coptic and Armenian sources to describe the early Arab conquerors of Mesopotamia, Syria and Egypt.

The name was us ...

", "Alim", probably

Ali ibn-Sulayman, an Abbasid governor who raided Roman territory in 785 AD.

Bacchus the Younger was beheaded in Jerusalem in 786–787 AD. Bacchus was Palestinian, whose family, having been Christian, had been converted to Islam by their father.

Bacchus however, remained crypto-Christian and undertook a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, upon which he was baptized and entered the monastery of

Mar Saba.

Reunion with his family prompted their reconversion to Christianity and Bacchus's trial and execution for apostasy under the governing ''emir''

Harthama ibn A'yan.

After the 838

Sack of Amorium

The Sack of Amorium by the Abbasid Caliphate in mid-August 838 was one of the major events in the long history of the Arab–Byzantine Wars. The Abbasid campaign was led personally by the Caliph al-Mu'tasim (), in retaliation to a virtually unop ...

, the hometown of the emperor

Theophilos () and his

Amorian dynasty

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by the Amorian or Phrygian dynasty from 820 to 867. The Amorian dynasty continued the policy of restored iconoclasm (the "Second Iconoclasm") started by the previous non-dynastic emperor Leo V in 813, until its abol ...

, the caliph

al-Mu'tasim

Abū Isḥāq Muḥammad ibn Hārūn al-Rashīd ( ar, أبو إسحاق محمد بن هارون الرشيد; October 796 – 5 January 842), better known by his regnal name al-Muʿtaṣim biʾllāh (, ), was the eighth Abbasid caliph, ruling f ...

() took more than forty Roman prisoners.

These were taken to the capital,

Samarra

Samarra ( ar, سَامَرَّاء, ') is a city in Iraq. It stands on the east bank of the Tigris in the Saladin Governorate, north of Baghdad. The city of Samarra was founded by Abbasid Caliph Al-Mutasim for his Turkish professional ar ...

, where after seven years of theological debates and repeated refusals to convert to Islam, they were put to death in March 845 under the caliph

al-Wathiq

Abū Jaʿfar Hārūn ibn Muḥammad ( ar, أبو جعفر هارون بن محمد المعتصم; 17 April 812 – 10 August 847), better known by his regnal name al-Wāthiq bi’llāh (, ), was an Abbasid caliph who reigned from 842 until 847 ...

().

Within a generation they were venerated as the

42 Martyrs of Amorium. According to their hagiographer Euodius, probably writing within a generation of the events, the defeat at Amorium was to be blamed on Theophilos and his iconoclasm.

According to some later hagiographies, including one by one of several Middle Byzantine writers known as Michael the Synkellos, among the forty-two were Kallistos, the

''doux'' of the

Koloneian ''thema'', and the heroic martyr Theodore Karteros.

During the

10th-century phase of the

Arab–Byzantine wars

The Arab–Byzantine wars were a series of wars between a number of Muslim Arab dynasties and the Byzantine Empire between the 7th and 11th centuries AD. Conflict started during the initial Muslim conquests, under the expansionist Rashidun and ...

, the victories of the Romans over the Arabs resulted in mob attacks on Christians, who were believed to sympathize with the Roman state.

According to

Bar Hebraeus

Gregory Bar Hebraeus ( syc, ܓܪܝܓܘܪܝܘܣ ܒܪ ܥܒܪܝܐ, b. 1226 - d. 30 July 1286), known by his Syriac ancestral surname as Bar Ebraya or Bar Ebroyo, and also by a Latinized name Abulpharagius, was an Aramean Maphrian (regional prim ...

, the ''

catholicus'' of the Church of the East,

Abraham III (), wrote to the

grand vizier that "we Nestorians are the friends of the Arabs and pray for their victories".

The attitude of the Nestorians "who have no other king but the Arabs", he contrasted with the Greek Orthodox Church, whose emperors he said "had never cease to make war against the Arabs.

Between 923 and 924 AD, several Orthodox churches were destroyed in mob violence in

Ramla,

Ashkelon

Ashkelon or Ashqelon (; Hebrew: , , ; Philistine: ), also known as Ascalon (; Ancient Greek: , ; Arabic: , ), is a coastal city in the Southern District of Israel on the Mediterranean coast, south of Tel Aviv, and north of the border with ...

,

Caesarea Maritima

Caesarea Maritima (; Greek: ''Parálios Kaisáreia''), formerly Strato's Tower, also known as Caesarea Palestinae, was an ancient city in the Sharon plain on the coast of the Mediterranean, now in ruins and included in an Israeli national park ...

, and

Damascus.

In each instance, according to the Arab

Melkite Christian chronicler

Eutychius of Alexandria

Eutychius of Alexandria (Arabic: ''Sa'id ibn Batriq'' or ''Bitriq''; 10 September 877 – 12 May 940) was the Melkite Patriarch of Alexandria. He is known for being one of the first Christian Egyptian writers to use the Arabic language. H ...

, the caliph

al-Muqtadir

Abu’l-Faḍl Jaʿfar ibn Ahmad al-Muʿtaḍid ( ar, أبو الفضل جعفر بن أحمد المعتضد) (895 – 31 October 932 AD), better known by his regnal name Al-Muqtadir bi-llāh ( ar, المقتدر بالله, "Mighty in God"), wa ...

() contributed to the rebuilding of ecclesiastical property.

Byzantine Iconoclasm

Following a series of heavy military reverses against the Muslims, Iconoclasm emerged within the

provinces of the Byzantine Empire Subdivisions of the Byzantine Empire were administrative units of the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire (330–1453). The Empire had a developed administrative system, which can be divided into three major periods: the late Roman/early Byzantine, w ...

in the early 8th century. In the years 720s, the Byzantine Emperor

Leo III the Isaurian