Quaternary extinction event on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The timing of extinctions on the Indian subcontinent is uncertain due to a lack of reliable dating. Similar issues have been reported for Chinese sites, though there is no evidence for any of the megafaunal taxa having survived into the Holocene in that region. Extinctions in Southeast Asia and South China have been proposed to be the result of environmental shift from open to closed forested habitats.

*

The timing of extinctions on the Indian subcontinent is uncertain due to a lack of reliable dating. Similar issues have been reported for Chinese sites, though there is no evidence for any of the megafaunal taxa having survived into the Holocene in that region. Extinctions in Southeast Asia and South China have been proposed to be the result of environmental shift from open to closed forested habitats.

*

The

The

North American extinctions (noted as

North American extinctions (noted as

South America suffered among the worst losses of the continents, with around 83% of its megafauna going extinct. These extinctions postdate the arrival of modern humans in South America around 15,000 years ago. Both human and climatic factors have been attributed as factors in the extinctions by various authors. Although some megafauna has been historically suggested to have survived into the early Holocene based on radiocarbon dates this may be the result of dating errors due to contamination. The extinctions are coincident with the end of the Antarctic Cold Reversal (a cooling period earlier and less severe than the Northern Hemisphere Younger Dryas) and the emergence of Fishtail projectile points, which became widespread across South America. Fishtail projectile points are thought to have been used in big game hunting, though direct evidence of exploitation of extinct megafauna by humans is rare, though megafauna exploitation has been documented at a number of sites. Fishtail points rapidly disappeared after the extinction of the megafauna, and were replaced by other styles more suited to hunting smaller prey. Some authors have proposed the "Broken Zig-Zag" model, where human hunting and climate change causing a reduction in open habitats preferred by megafauna were synergistic factors in megafauna extinction in South America.

* Ungulates

** ''Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals''

*** Several Cervidae (deer) spp.

**** '' Morenelaphus''

**** '' Antifer''

**** '' Agalmaceros blicki'' (potentially synonym of modern

South America suffered among the worst losses of the continents, with around 83% of its megafauna going extinct. These extinctions postdate the arrival of modern humans in South America around 15,000 years ago. Both human and climatic factors have been attributed as factors in the extinctions by various authors. Although some megafauna has been historically suggested to have survived into the early Holocene based on radiocarbon dates this may be the result of dating errors due to contamination. The extinctions are coincident with the end of the Antarctic Cold Reversal (a cooling period earlier and less severe than the Northern Hemisphere Younger Dryas) and the emergence of Fishtail projectile points, which became widespread across South America. Fishtail projectile points are thought to have been used in big game hunting, though direct evidence of exploitation of extinct megafauna by humans is rare, though megafauna exploitation has been documented at a number of sites. Fishtail points rapidly disappeared after the extinction of the megafauna, and were replaced by other styles more suited to hunting smaller prey. Some authors have proposed the "Broken Zig-Zag" model, where human hunting and climate change causing a reduction in open habitats preferred by megafauna were synergistic factors in megafauna extinction in South America.

* Ungulates

** ''Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals''

*** Several Cervidae (deer) spp.

**** '' Morenelaphus''

**** '' Antifer''

**** '' Agalmaceros blicki'' (potentially synonym of modern

*

*  *** '' Ikanogavialis'' (the last fully marine crocodilian)

*** '' Paludirex'' (Australian freshwater mekosuchine crocodiian)

*** '' Quinkana'' (Australian terrestrial mekosuchine crocodilian,

*** '' Ikanogavialis'' (the last fully marine crocodilian)

*** '' Paludirex'' (Australian freshwater mekosuchine crocodiian)

*** '' Quinkana'' (Australian terrestrial mekosuchine crocodilian,

A 2020 study published in ''Science Advances'' found that human population size and/or specific human activities, not climate change, caused rapidly rising global mammal extinction rates during the past 126,000 years. Around 96% of all mammalian extinctions over this time period are attributable to human impacts. According to Tobias Andermann, lead author of the study, "these extinctions did not happen continuously and at constant pace. Instead, bursts of extinctions are detected across different continents at times when humans first reached them. More recently, the magnitude of human driven extinctions has picked up the pace again, this time on a global scale." Text and images are available under a creativecommons:by/4.0/, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. On a related note, the population declines of still extant megafauna during the Pleistocene have also been shown to correlate with human expansion rather than climate change.

The extinction's extreme bias towards larger animals further supports a relationship with human activity rather than climate change. There is evidence that the average size of mammalian fauna declined over the course of the Quaternary, a phenomenon that was likely linked to disproportionate hunting of large animals by humans.

Extinction through human hunting has been supported by archaeological finds of mammoths with projectile points embedded in their skeletons, by observations of modern naive animals allowing hunters to approach easily and by computer models by Mosimann and Martin, and Whittington and Dyke, and most recently by Alroy.

A 2020 study published in ''Science Advances'' found that human population size and/or specific human activities, not climate change, caused rapidly rising global mammal extinction rates during the past 126,000 years. Around 96% of all mammalian extinctions over this time period are attributable to human impacts. According to Tobias Andermann, lead author of the study, "these extinctions did not happen continuously and at constant pace. Instead, bursts of extinctions are detected across different continents at times when humans first reached them. More recently, the magnitude of human driven extinctions has picked up the pace again, this time on a global scale." Text and images are available under a creativecommons:by/4.0/, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. On a related note, the population declines of still extant megafauna during the Pleistocene have also been shown to correlate with human expansion rather than climate change.

The extinction's extreme bias towards larger animals further supports a relationship with human activity rather than climate change. There is evidence that the average size of mammalian fauna declined over the course of the Quaternary, a phenomenon that was likely linked to disproportionate hunting of large animals by humans.

Extinction through human hunting has been supported by archaeological finds of mammoths with projectile points embedded in their skeletons, by observations of modern naive animals allowing hunters to approach easily and by computer models by Mosimann and Martin, and Whittington and Dyke, and most recently by Alroy. In 2024 a paper was published in ''Science Advances'' that added additional support to the overkill hypothesis in North America when the skull of an 18 month old child, dated to 12,800 years ago, was analyzed for chemical signatures attributable to both maternal milk and solid food. Specific isotopes of carbon and nitrogen most closely matched those that would have been found in the mammoth genus and secondarily elk or bison.

A number of objections have been raised regarding the hunting hypothesis. Notable among them is the sparsity of evidence of human hunting of megafauna. There is no archeological evidence that in North America megafauna other than mammoths, mastodons, gomphotheres and bison were hunted, despite the fact that, for example, camels and horses are very frequently reported in fossil history. Overkill proponents, however, say this is due to the fast extinction process in North America and the low probability of animals with signs of butchery to be preserved. The majority of North American taxa have too sparse a fossil record to accurately assess the frequency of human hunting of them. A study by Surovell and Grund concluded "archaeological sites dating to the time of the coexistence of humans and extinct fauna are rare. Those that preserve bone are considerably more rare, and of those, only a very few show unambiguous evidence of human hunting of any type of prey whatsoever." Eugene S. Hunn suggests that the birthrate in hunter-gatherer societies is generally too low, that too much effort is involved in the bringing down of a large animal by a hunting party, and that in order for hunter-gatherers to have brought about the extinction of megafauna simply by hunting them to death, an extraordinary amount of meat would have had to have been wasted. Proponents of hunting as a cause of the extinctions argue that statistical modelling validates that relatively low-level hunting can have significant effect on megafauna populations due to their slow life cycles, and that hunting can cause top-down forcing trophic cascade events that destabilize ecosystems.

In 2024 a paper was published in ''Science Advances'' that added additional support to the overkill hypothesis in North America when the skull of an 18 month old child, dated to 12,800 years ago, was analyzed for chemical signatures attributable to both maternal milk and solid food. Specific isotopes of carbon and nitrogen most closely matched those that would have been found in the mammoth genus and secondarily elk or bison.

A number of objections have been raised regarding the hunting hypothesis. Notable among them is the sparsity of evidence of human hunting of megafauna. There is no archeological evidence that in North America megafauna other than mammoths, mastodons, gomphotheres and bison were hunted, despite the fact that, for example, camels and horses are very frequently reported in fossil history. Overkill proponents, however, say this is due to the fast extinction process in North America and the low probability of animals with signs of butchery to be preserved. The majority of North American taxa have too sparse a fossil record to accurately assess the frequency of human hunting of them. A study by Surovell and Grund concluded "archaeological sites dating to the time of the coexistence of humans and extinct fauna are rare. Those that preserve bone are considerably more rare, and of those, only a very few show unambiguous evidence of human hunting of any type of prey whatsoever." Eugene S. Hunn suggests that the birthrate in hunter-gatherer societies is generally too low, that too much effort is involved in the bringing down of a large animal by a hunting party, and that in order for hunter-gatherers to have brought about the extinction of megafauna simply by hunting them to death, an extraordinary amount of meat would have had to have been wasted. Proponents of hunting as a cause of the extinctions argue that statistical modelling validates that relatively low-level hunting can have significant effect on megafauna populations due to their slow life cycles, and that hunting can cause top-down forcing trophic cascade events that destabilize ecosystems.

The Second-Order Predation Hypothesis says that as humans entered the New World they continued their policy of killing predators, which had been successful in the Old World but because they were more efficient and because the fauna, both herbivores and carnivores, were more naive, they killed off enough carnivores to upset the Ecological equilibrium, ecological balance of the continent, causing overpopulation (biology), overpopulation, environmental exhaustion, and environmental collapse. The hypothesis accounts for changes in animal, plant, and human populations.

The scenario is as follows:

* After the arrival of ''H. sapiens'' in the New World, existing predators must share the prey populations with this new predator. Because of this competition, populations of original, or first-order, predators cannot find enough food; they are in direct competition with humans.

* Second-order predation begins as humans begin to kill predators.

* Prey populations are no longer well controlled by predation. Killing of nonhuman predators by ''H. sapiens'' reduces their numbers to a point where these predators no longer regulate the size of the prey populations.

* Lack of regulation by first-order predators triggers boom-and-bust cycles in prey populations. Prey populations expand and consequently overgraze and over-browse the land. Soon the environment is no longer able to support them. As a result, many herbivores starve. Species that rely on the slowest recruiting food become extinct, followed by species that cannot extract the maximum benefit from every bit of their food.

* Boom-bust cycles in herbivore populations change the nature of the vegetative environment, with consequent climatic impacts on relative humidity and continentality. Through overgrazing and overbrowsing, mixed parkland becomes grassland, and climatic continentality increases.

The second-order predation hypothesis has been supported by a computer model, the Pleistocene extinction model (PEM), which, using the same assumptions and values for all variables (herbivore population, herbivore recruitment rates, food needed per human, herbivore hunting rates, etc.) other than those for hunting of predators. It compares the overkill hypothesis (predator hunting = 0) with second-order predation (predator hunting varied between 0.01 and 0.05 for different runs). The findings are that second-order predation is more consistent with extinction than is overkill (results graph at left). The Pleistocene extinction model is the only test of multiple hypotheses and is the only model to specifically test combination hypotheses by artificially introducing sufficient climate change to cause extinction. When overkill and climate change are combined they balance each other out. Climate change reduces the number of plants, overkill removes animals, therefore fewer plants are eaten. Second-order predation combined with climate change exacerbates the effect of climate change. (results graph at right). The second-order predation hypothesis is further supported by the observation above that there was a massive increase in bison populations.

The Second-Order Predation Hypothesis says that as humans entered the New World they continued their policy of killing predators, which had been successful in the Old World but because they were more efficient and because the fauna, both herbivores and carnivores, were more naive, they killed off enough carnivores to upset the Ecological equilibrium, ecological balance of the continent, causing overpopulation (biology), overpopulation, environmental exhaustion, and environmental collapse. The hypothesis accounts for changes in animal, plant, and human populations.

The scenario is as follows:

* After the arrival of ''H. sapiens'' in the New World, existing predators must share the prey populations with this new predator. Because of this competition, populations of original, or first-order, predators cannot find enough food; they are in direct competition with humans.

* Second-order predation begins as humans begin to kill predators.

* Prey populations are no longer well controlled by predation. Killing of nonhuman predators by ''H. sapiens'' reduces their numbers to a point where these predators no longer regulate the size of the prey populations.

* Lack of regulation by first-order predators triggers boom-and-bust cycles in prey populations. Prey populations expand and consequently overgraze and over-browse the land. Soon the environment is no longer able to support them. As a result, many herbivores starve. Species that rely on the slowest recruiting food become extinct, followed by species that cannot extract the maximum benefit from every bit of their food.

* Boom-bust cycles in herbivore populations change the nature of the vegetative environment, with consequent climatic impacts on relative humidity and continentality. Through overgrazing and overbrowsing, mixed parkland becomes grassland, and climatic continentality increases.

The second-order predation hypothesis has been supported by a computer model, the Pleistocene extinction model (PEM), which, using the same assumptions and values for all variables (herbivore population, herbivore recruitment rates, food needed per human, herbivore hunting rates, etc.) other than those for hunting of predators. It compares the overkill hypothesis (predator hunting = 0) with second-order predation (predator hunting varied between 0.01 and 0.05 for different runs). The findings are that second-order predation is more consistent with extinction than is overkill (results graph at left). The Pleistocene extinction model is the only test of multiple hypotheses and is the only model to specifically test combination hypotheses by artificially introducing sufficient climate change to cause extinction. When overkill and climate change are combined they balance each other out. Climate change reduces the number of plants, overkill removes animals, therefore fewer plants are eaten. Second-order predation combined with climate change exacerbates the effect of climate change. (results graph at right). The second-order predation hypothesis is further supported by the observation above that there was a massive increase in bison populations.

However, this hypothesis has been criticised on the grounds that the multispecies model produces a mass extinction through indirect competition between herbivore species: small species with high reproductive rates subsidize predation on large species with low reproductive rates. All prey species are lumped in the Pleistocene extinction model. Also, the control of population sizes by predators is not fully supported by observations of modern ecosystems. The hypothesis further assumes decreases in vegetation due to climate change, but deglaciation doubled the habitable area of North America. Any vegetational changes that did occur failed to cause almost any extinctions of small vertebrates, and they are more narrowly distributed on average, which detractors cite as evidence against the hypothesis.

However, this hypothesis has been criticised on the grounds that the multispecies model produces a mass extinction through indirect competition between herbivore species: small species with high reproductive rates subsidize predation on large species with low reproductive rates. All prey species are lumped in the Pleistocene extinction model. Also, the control of population sizes by predators is not fully supported by observations of modern ecosystems. The hypothesis further assumes decreases in vegetation due to climate change, but deglaciation doubled the habitable area of North America. Any vegetational changes that did occur failed to cause almost any extinctions of small vertebrates, and they are more narrowly distributed on average, which detractors cite as evidence against the hypothesis.

However, more recent authors have viewed it as more likely that the collapse of the mammoth steppe was driven by climatic warming, which in turn impacted the megafauna, rather than the other way around.

Megafauna play a significant role in the lateral transport of mineral nutrients in an ecosystem, tending to translocate them from areas of high to those of lower abundance. They do so by their movement between the time they consume the nutrient and the time they release it through elimination (or, to a much lesser extent, through decomposition after death). In South America's Amazon Basin, it is estimated that such lateral diffusion was reduced over 98% following the megafaunal extinctions that occurred roughly 12,500 years ago. Given that phosphorus availability is thought to limit productivity in much of the region, the decrease in its transport from the western part of the basin and from floodplains (both of which derive their supply from the uplift of the Andes) to other areas is thought to have significantly impacted the region's ecology, and the effects may not yet have reached their limits. The extinction of the mammoths allowed grasslands they had maintained through grazing habits to become birch forests. The new forest and the resulting forest fires may have induced

However, more recent authors have viewed it as more likely that the collapse of the mammoth steppe was driven by climatic warming, which in turn impacted the megafauna, rather than the other way around.

Megafauna play a significant role in the lateral transport of mineral nutrients in an ecosystem, tending to translocate them from areas of high to those of lower abundance. They do so by their movement between the time they consume the nutrient and the time they release it through elimination (or, to a much lesser extent, through decomposition after death). In South America's Amazon Basin, it is estimated that such lateral diffusion was reduced over 98% following the megafaunal extinctions that occurred roughly 12,500 years ago. Given that phosphorus availability is thought to limit productivity in much of the region, the decrease in its transport from the western part of the basin and from floodplains (both of which derive their supply from the uplift of the Andes) to other areas is thought to have significantly impacted the region's ecology, and the effects may not yet have reached their limits. The extinction of the mammoths allowed grasslands they had maintained through grazing habits to become birch forests. The new forest and the resulting forest fires may have induced

Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as the Upper Pleistocene from a Stratigraphy, stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division ...

to the beginning of the Holocene

The Holocene () is the current geologic time scale, geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene to ...

saw the extinction of the majority of the world's megafauna

In zoology, megafauna (from Ancient Greek, Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and Neo-Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") are large animals. The precise definition of the term varies widely, though a common threshold is approximately , this lower en ...

, typically defined as animal species having body masses over , which resulted in a collapse in faunal density and diversity across the globe. The extinctions during the Late Pleistocene are differentiated from previous extinctions by their extreme size bias towards large animals (with small animals being largely unaffected), and widespread absence of ecological succession

Ecological succession is the process of how species compositions change in an Community (ecology), ecological community over time.

The two main categories of ecological succession are primary succession and secondary succession. Primary successi ...

to replace these extinct megafaunal species, and the regime shift of previously established faunal relationships and habitats as a consequence. The timing and severity of the extinctions varied by region and are generally thought to have been driven by humans, climatic change, or a combination of both. Human impact on megafauna populations is thought to have been driven by hunting ("overkill"), as well as possibly environmental alteration. The relative importance of human vs climatic factors in the extinctions has been the subject of long-running controversy, though most scholars support at least a contributory role of humans in the extinctions.

Major extinctions occurred in Australia-New Guinea (Sahul

__NOTOC__

Sahul (), also called Sahul-land, Meganesia, Papualand and Greater Australia, was a paleocontinent that encompassed the modern-day landmasses of mainland Australia, Tasmania, New Guinea, and the Aru Islands.

Sahul was in the south- ...

) beginning around 50,000 years ago and in the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

about 13,000 years ago, coinciding in time with the early human migrations

Early human migrations are the earliest migrations and expansions of archaic and modern humans across continents. They are believed to have begun approximately 2 million years ago with the early expansions out of Africa by ''Homo erectu ...

into these regions. Extinctions in northern Eurasia were staggered over tens of thousands of years between 50,000 and 10,000 years ago, while extinctions in the Americas were virtually simultaneous, spanning only 3000 years at most. Overall, during the Late Pleistocene about 65% of all megafaunal species worldwide became extinct, rising to 72% in North America, 83% in South America and 88% in Australia, with all mammals over becoming extinct in Australia and the Americas, and around 80% globally. Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia experienced more moderate extinctions than other regions.

The Late Pleistocene-early Holocene megafauna extinctions have often been seen as part of a single extinction event with later, widely agreed to be human-caused extinctions in the mid-late Holocene, such as those on Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

, as the Late Quaternary extinction event.

Extinctions by biogeographic realm

Summary

Introduction

The Late Pleistocene saw the extinction of many mammals weighing more than , including around 80% of mammals over 1 tonne. The proportion of megafauna extinctions is progressively larger the further the human migratory distance from Africa, with the highest extinction rates in Australia, and North and South America. The increased extent of extinction mirrors the migration pattern of modern humans: the further away from Africa, the more recently humans inhabited the area, the less time those environments (including its megafauna) had to become accustomed to humans (and vice versa). There are two main hypotheses to explain this extinction: *Climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

associated with the advance and retreat of major ice caps

In glaciology, an ice cap is a mass of ice that covers less than of land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of Earth not submerged by the ocean or another body of water. It makes up 29.2% ...

or ice sheets

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are the Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet. Ice sheets ...

causing reduction in favorable habitat.

* Human hunting causing attrition of megafauna populations, commonly known as "overkill".

There are some inconsistencies between the current available data and the prehistoric overkill hypothesis. For instance, there are ambiguities around the timing of Australian megafauna

The term Australian megafauna refers to the megafauna in Australia (continent), Australia during the Pleistocene, Pleistocene Epoch. Most of these species became extinct during the latter half of the Pleistocene, as part of the broader global L ...

extinctions. Evidence supporting the prehistoric overkill hypothesis includes the persistence of megafauna on some islands for millennia past the disappearance of their continental cousins. For instance, ground sloths survived on the Antilles

The Antilles is an archipelago bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the south and west, the Gulf of Mexico to the northwest, and the Atlantic Ocean to the north and east.

The Antillean islands are divided into two smaller groupings: the Greater An ...

long after North and South American ground sloths were extinct, woolly mammoths died out on remote Wrangel Island

Wrangel Island (, ; , , ) is an island of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. It is the List of islands by area, 92nd-largest island in the world and roughly the size of Crete. Located in the Arctic Ocean between the Chukchi Sea and East Si ...

6,000 years after their extinction on the mainland, and Steller's sea cow

Steller's sea cow (''Hydrodamalis gigas'') is an extinction, extinct sirenian described by Georg Wilhelm Steller in 1741. At that time, it was found only around the Commander Islands in the Bering Sea between Alaska and Russia; its range exte ...

s persisted off the isolated and uninhabited Commander Islands

The Commander Islands, Komandorski Islands, or Komandorskie Islands (, ''Komandorskiye ostrova'') are a series of islands in the Russian Far East, a part of the Aleutian Islands, located about east of the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Bering Sea. ...

for thousands of years after they had vanished from the continental shores of the north Pacific. The later disappearance of these island species correlates with the later colonization of these islands by humans.

Still, there are some arguments that species responded differently to environmental changes, and no one factor by itself explains the large variety of extinctions. The causes may involve the interplay of climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

, competition between species, unstable population dynamics

Population dynamics is the type of mathematics used to model and study the size and age composition of populations as dynamical systems. Population dynamics is a branch of mathematical biology, and uses mathematical techniques such as differenti ...

, and hunting as well as competition by humans.

The original debates as to whether human arrival times or climate change constituted the primary cause of megafaunal extinctions necessarily were based on paleontological evidence coupled with geological dating techniques. Recently, genetic analyses of surviving megafaunal populations have contributed new evidence, leading to the conclusion: "The inability of climate to predict the observed population decline of megafauna, especially during the past 75,000 years, implies that human impact became the main driver of megafauna dynamics around this date."

Africa

Although Africa was one of the least affected regions, the region still suffered extinctions, particularly around the Late Pleistocene-Holocene transition. These extinctions were likely predominantly climatically driven by changes to grassland habitats. *Ungulate

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with Hoof, hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined ...

s

** '' Even-Toed Ungulates''

*** Suidae

Suidae is a family (biology), family of Even-toed ungulate, artiodactyl mammals which are commonly called pigs, hogs, or swine. In addition to numerous fossil species, 18 Extant taxon, extant species are currently recognized (or 19 counting domes ...

(swine)

**** '' Metridiochoerus '' (ssp.)

**** '' Kolpochoerus'' (ssp.)

***Bovidae

The Bovidae comprise the family (biology), biological family of cloven-hoofed, ruminant mammals that includes Bos, cattle, bison, Bubalina, buffalo, antelopes (including Caprinae, goat-antelopes), Ovis, sheep and Capra (genus), goats. A member o ...

(bovines, antelope)

**** Giant buffalo (''Syncerus antiquus'')

**** '' Megalotragus''

**** '' Rusingoryx''

**** Southern springbok (''Antidorcas australis'')

**** Bond's springbok (''Antidorcas bondi'')

**** '' Damaliscus hypsodon''

**** '' Damaliscus niro''

**** Atlantic gazelle (''Gazella atlantica'')

**** '' Gazella tingitana''

**** Caprinae

The subfamily Caprinae, also sometimes referred to as the tribe Caprini, is part of the ruminant family Bovidae, and consists of mostly medium-sized bovids. A member of this subfamily is called a caprine.

Prominent members include sheep and g ...

***** '' Makapania?''

*** Cervidae (deer)

****'' Megaceroides algericus'' (North Africa)

**'' Odd-toed Ungulates''

***Rhinoceros

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

(Rhinocerotidae).

**** Narrow-nosed rhinoceros

The narrow-nosed rhinoceros (''Stephanorhinus hemitoechus''), also known as the steppe rhinoceros is an extinct species of rhinoceros belonging to the genus '' Stephanorhinus'' that lived in western Eurasia, including Europe, and West Asia, as ...

(''Stephanorhinus hemitoechus'', North Africa)

**** '' Ceratotherium mauritanicum''

***Wild ''Equus'' spp.

**** Caballine horses

*****''Equus algericus'' (North Africa)

****Subgenus ''Asinus

''Asinus'' is a subgenus of ''Equus (genus), Equus'' that encompasses several subspecies of the Equidae commonly known as wild asses, characterized by long ears, a lean, straight-backed build, lack of a true withers, a coarse mane and tail, and a ...

'' (asses)

*****''Equus melkiensis'' (North Africa)

**** Zebras

***** Giant zebra (''Equus capensis'')

***** Saharan zebra (''Equus mauritanicus'')

*Proboscidea

Proboscidea (; , ) is a taxonomic order of afrotherian mammals containing one living family (Elephantidae) and several extinct families. First described by J. Illiger in 1811, it encompasses the elephants and their close relatives. Three l ...

**Elephantidae

Elephantidae is a family (biology), family of large, herbivorous proboscidean mammals which includes the living Elephant, elephants (belonging to the genera ''Elephas'' and ''Loxodonta''), as well as a number of extinct genera like ''Mammuthus'' ...

(elephants)

***'' Palaeoloxodon iolensis''? (other authors suggest that this taxon went extinct at the end of the Middle Pleistocene)

* Rodentia

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are na ...

** ''Paraethomys filfilae''?

South Asia and Southeast Asia

The timing of extinctions on the Indian subcontinent is uncertain due to a lack of reliable dating. Similar issues have been reported for Chinese sites, though there is no evidence for any of the megafaunal taxa having survived into the Holocene in that region. Extinctions in Southeast Asia and South China have been proposed to be the result of environmental shift from open to closed forested habitats.

*

The timing of extinctions on the Indian subcontinent is uncertain due to a lack of reliable dating. Similar issues have been reported for Chinese sites, though there is no evidence for any of the megafaunal taxa having survived into the Holocene in that region. Extinctions in Southeast Asia and South China have been proposed to be the result of environmental shift from open to closed forested habitats.

* Ungulate

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with Hoof, hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined ...

s

** '' Even-Toed Ungulates''

*** Several Bovidae

The Bovidae comprise the family (biology), biological family of cloven-hoofed, ruminant mammals that includes Bos, cattle, bison, Bubalina, buffalo, antelopes (including Caprinae, goat-antelopes), Ovis, sheep and Capra (genus), goats. A member o ...

spp.

**** '' Bos palaesondaicus'' (ancestor to the banteng

The banteng (''Bos javanicus''; ), also known as tembadau, is a species of wild Bovinae, bovine found in Southeast Asia.

The head-and-body length is between . Wild banteng are typically larger and heavier than their Bali cattle, domesticated ...

)

**** Cebu tamaraw (''Bubalus cebuensis'')

**** '' Bubalus grovesi''

**** Short-horned water buffalo (''Bubalus mephistopheles'')

**** '' Bubalus palaeokerabau''

*** Hippopotamidae

Hippopotamidae is a family of stout, naked-skinned, and semiaquatic artiodactyl mammals, possessing three-chambered stomachs and walking on four toes on each foot. While they resemble pigs physiologically, their closest living relatives are th ...

**** '' Hexaprotodon'' (Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia)

** '' Odd-toed Ungulates''

***'' Equus'' spp.

**** '' Equus namadicus'' (Indian subcontinent)

**** Yunnan horse (''Equus yunanensis'')

*** Giant tapir (''Tapirus augustus,'' Southeast Asia and Southern China)

*** '' Taprus sinensis''

* Pholidota

Pangolins, sometimes known as scaly anteaters, are mammals of the order Pholidota (). The one Neontology, extant family, the Manidae, has three genera: ''Manis'', ''Phataginus'', and ''Smutsia''. ''Manis'' comprises four species found in Asia, ...

** Giant Asian pangolin ('' Manis palaeojavanica'')

* Carnivora

Carnivora ( ) is an order of placental mammals specialized primarily in eating flesh, whose members are formally referred to as carnivorans. The order Carnivora is the sixth largest order of mammals, comprising at least 279 species. Carnivor ...

** Ursidae

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family (biology), family Ursidae (). They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats ...

(bears)

*** '' Ailuropoda baconi'' (ancestor to the giant panda

The giant panda (''Ailuropoda melanoleuca''), also known as the panda bear or simply panda, is a bear species endemic to China. It is characterised by its white animal coat, coat with black patches around the eyes, ears, legs and shoulders. ...

, which it is often considered a subspecies of distinctiveness from the living species has been disputed)

** Hyaenidae (hyenas)

*** Cave hyena (''Crocuta'' (''Crocuta'') ''ultima'' East Asia and Mainland Southeast Asia)

*Afrotheria

Afrotheria ( from Latin ''Afro-'' "of Africa" + ''theria'' "wild beast") is a superorder of placental mammals, the living members of which belong to groups that are either currently living in Africa or of African origin: golden moles, elephan ...

** Proboscidea

Proboscidea (; , ) is a taxonomic order of afrotherian mammals containing one living family (Elephantidae) and several extinct families. First described by J. Illiger in 1811, it encompasses the elephants and their close relatives. Three l ...

ns

*** Stegodontidae

**** ''Stegodon

''Stegodon'' (from the Ancient Greek στέγω (''stégō''), meaning "to cover", and ὀδούς (''odoús''), meaning "tooth", named for the distinctive ridges on the animal's molars) is an extinct genus of proboscidean, related to elephants ...

'' spp''.'' (including ''Stegodon florensis'' on Flores, ''Stegodon orientalis'' in East and Southeast Asia, and ''Stegodon'' sp. in the Indian subcontinent)

***Elephantidae

Elephantidae is a family (biology), family of large, herbivorous proboscidean mammals which includes the living Elephant, elephants (belonging to the genera ''Elephas'' and ''Loxodonta''), as well as a number of extinct genera like ''Mammuthus'' ...

**** ''Palaeoloxodon

''Palaeoloxodon'' is an extinct genus of elephant. The genus originated in Africa during the Early Pleistocene, and expanded into Eurasia at the beginning of the Middle Pleistocene. The genus contains the largest known species of elephants, with ...

'' spp.

***** '' Palaeoloxodon namadicus'' (Indian subcontinent, possibly also Southeast Asia)

* Birds

** Japanese flightless duck (''Shiriyanetta hasegawai'')

** '' Leptoptilos robustus''

** Ostrich

Ostriches are large flightless birds. Two living species are recognised, the common ostrich, native to large parts of sub-Saharan Africa, and the Somali ostrich, native to the Horn of Africa.

They are the heaviest and largest living birds, w ...

es (''Struthio'') (Indian subcontinent)

*Reptiles

**Crocodilia

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchia ...

***'' Alligator munensis''?

**Testudines

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

(turtles and tortoises)

***'' Manouria oyamai''

* Primates

** Several simian

The simians, anthropoids, or higher primates are an infraorder (Simiiformes ) of primates containing all animals traditionally called monkeys and apes. More precisely, they consist of the parvorders New World monkey, Platyrrhini (New World mon ...

(Simiiformes) spp.

*** ''Pongo'' ( orangutans)

**** ''Pongo weidenreichi

The Chinese orangutan (''Pongo weidenreichi'') is an extinct species of orangutan from the Pleistocene of South China and possibly Southeast Asia. It is known from fossil teeth found in the Sanhe Cave, and Baikong, Juyuan and Queque Caves in Ch ...

'' (South China)

*** Various ''Homo

''Homo'' () is a genus of great ape (family Hominidae) that emerged from the genus ''Australopithecus'' and encompasses only a single extant species, ''Homo sapiens'' (modern humans), along with a number of extinct species (collectively called ...

'' spp. (archaic humans)

**** '' Homo erectus soloensis'' (Java)

**** ''Homo floresiensis

''Homo floresiensis'' , also known as "Flores Man" or "Hobbit" (after Hobbit, the fictional species), is an Extinction, extinct species of small archaic humans that inhabited the island of Flores, Indonesia, until the arrival of Homo sapiens, ...

'' (Flores)

**** '' Homo luzonensis'' (Luzon, Philippines)

**** Denisovans

The Denisovans or Denisova hominins ( ) are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower Paleolithic, Lower and Middle Paleolithic, and lived, based on current evidence, from 285 thousand to 25 thou ...

(''Homo'' sp.)

Europe, Northern and East Asia

The

The Palearctic realm

The Palearctic or Palaearctic is a biogeographic realm of the Earth, the largest of eight. Confined almost entirely to the Eastern Hemisphere, it stretches across Europe and Asia, north of the foothills of the Himalayas, and North Africa.

The ...

spans the entirety of the European continent

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the eas ...

and stretches into northern Asia

North Asia or Northern Asia () is the northern region of Asia, which is defined in geographical terms and consists of three federal districts of Russia: Ural, Siberian, and the Far Eastern. North Asia is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to its n ...

, through the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

and central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

to northern China

Northern China () and Southern China () are two approximate regions that display certain differences in terms of their geography, demographics, economy, and culture.

Extent

The Qinling, Qinling–Daba Mountains serve as the transition zone ...

, Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

and Beringia

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 70th parallel north, 72° north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south ...

. Extinctions were more severe in Northern Eurasia than in Africa or South and Southeast Asia. These extinctions were staggered over tens of thousands of years, spanning from around 50,000 years Before Present

Before Present (BP) or "years before present (YBP)" is a time scale used mainly in archaeology, geology, and other scientific disciplines to specify when events occurred relative to the origin of practical radiocarbon dating in the 1950s. Because ...

(BP) to around 10,000 years BP, with temperate adapted species like the straight-tusked elephant

The straight-tusked elephant (''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'') is an extinct species of elephant that inhabited Europe and Western Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle and Late Pleistocene. One of the largest known elephant species, mature full ...

and the narrow-nosed rhinoceros

The narrow-nosed rhinoceros (''Stephanorhinus hemitoechus''), also known as the steppe rhinoceros is an extinct species of rhinoceros belonging to the genus '' Stephanorhinus'' that lived in western Eurasia, including Europe, and West Asia, as ...

generally going extinct earlier than cold adapted species like the woolly mammoth

The woolly mammoth (''Mammuthus primigenius'') is an extinct species of mammoth that lived from the Middle Pleistocene until its extinction in the Holocene epoch. It was one of the last in a line of mammoth species, beginning with the African ...

and woolly rhinoceros

The woolly rhinoceros (''Coelodonta antiquitatis'') is an extinct species of rhinoceros that inhabited northern Eurasia during the Pleistocene epoch. The woolly rhinoceros was a member of the Pleistocene megafauna. The woolly rhinoceros was larg ...

. Climate change has been considered a probable major factor in the extinctions, possibly in combination with human hunting.

* Ungulates

** ''Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals''

*** Various Bovidae

The Bovidae comprise the family (biology), biological family of cloven-hoofed, ruminant mammals that includes Bos, cattle, bison, Bubalina, buffalo, antelopes (including Caprinae, goat-antelopes), Ovis, sheep and Capra (genus), goats. A member o ...

spp.

**** Steppe bison

The steppe bison (''Bison'' ''priscus'', also less commonly known as the steppe wisent and the primeval bison) is an extinct species of bison which lived from the Middle Pleistocene to the Holocene. During the Late Pleistocene, it was widely dist ...

(''Bison priscus'')

**** Baikal yak (''Bos baikalensis'')

**** European water buffalo (''Bubalus murrensis'')

**** '' Bubalus wansijocki'' (extinct buffalo native to North China)

**** '' Bubalus teilhardi''

**** European tahr (''Hemitragus cedrensis'')

**** Giant muskox (''Praeovibos priscus'')

**** Northern saiga antelope (''Saiga borealis'')

**** Twisted-horned antelope ('' Spirocerus kiakhtensis'')

**** Goat-horned antelope ('' Parabubalis capricornis'')

*** Various deer

A deer (: deer) or true deer is a hoofed ruminant ungulate of the family Cervidae (informally the deer family). Cervidae is divided into subfamilies Cervinae (which includes, among others, muntjac, elk (wapiti), red deer, and fallow deer) ...

(Cervidae) spp.

**** Giant deer/Irish elk (''Megaloceros giganteus'')

**** Cretan deer (''Candiacervus'' spp.)

**** '' Haploidoceros mediterraneus''

**** ''Sinomegaceros

''Sinomegaceros'' is an extinct genus of deer known from the Late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene to Late Pleistocene of Central and East Asia. It is considered to be part of the group of "giant deer" (often referred to collectively as members of the ...

'' spp. (including ''Sinomegaceros yabei'' in Japan, and ''Sinomegaceros ordosianus'' and possibly ''Sinomegaceros pachyosteus'' in China).

**** Dwarf Ryukyu deer (''Cervus astylodon'')

*** All native ''Hippopotamus

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Sahar ...

'' spp.

**** '' Hippopotamus amphibius'' (European range, still extant in Africa)

**** Maltese dwarf hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus melitensis'')

**** Cyprus dwarf hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus minor'')

**** Sicilian dwarf hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus pentlandi'')

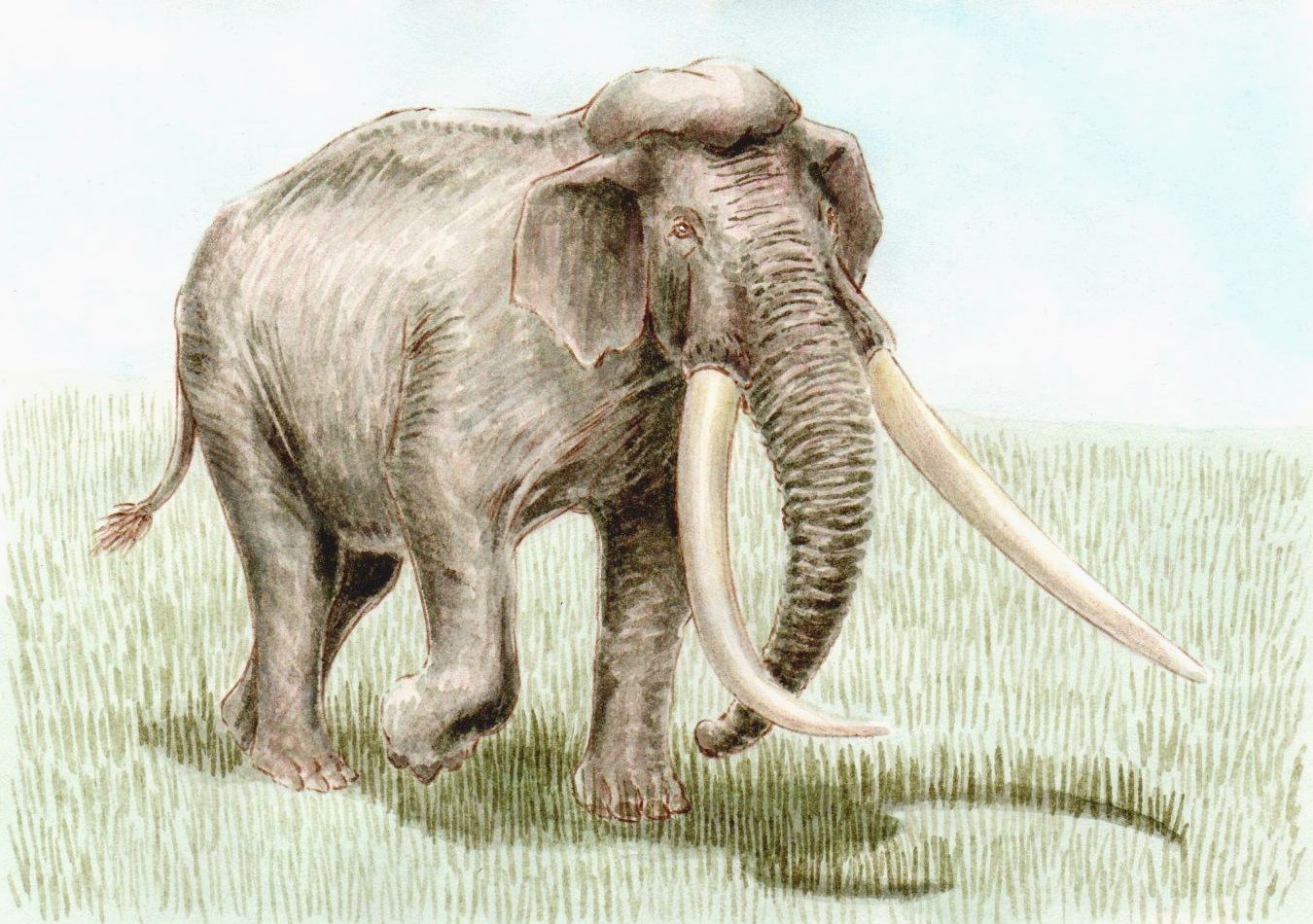

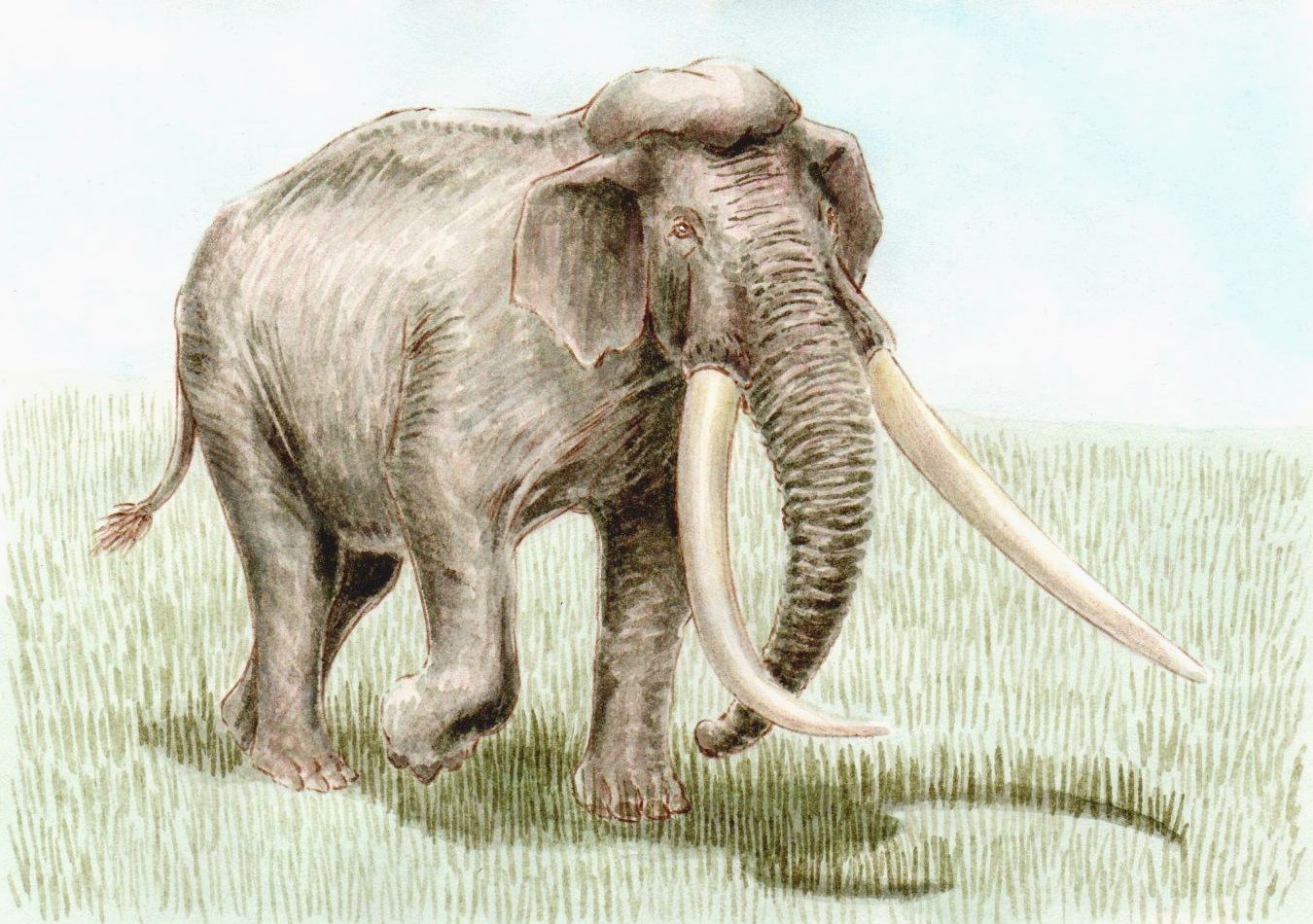

*** ''Camelus knoblochi

''Camelus knoblochi'' is an extinct species of camel that inhabited Eurasia during the Pleistocene epoch. One of the largest known camel species, its range spanned from Eastern Europe to Northern China.

History of discovery

The earliest remain ...

'' and other ''Camel

A camel (from and () from Ancient Semitic: ''gāmāl'') is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. Camels have long been domesticated and, as livestock, they provid ...

us'' spp.

** ''Odd-Toed Hoofed Mammals''

*** Various ''Equus'' spp. e.g.

**** Various wild horse

The wild horse (''Equus ferus'') is a species of the genus Equus (genus), ''Equus'', which includes as subspecies the modern domestication of the horse, domesticated horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') as well as the Endangered species, endangered ...

subspecies (e.g. ''Equus c.'' ''gallicus'', ''Equus'' ''c.'' ''latipes'', ''Equus c.'' ''uralensis'')

**** '' Equus dalianensis'' (wild horse species known from North China)

**** European wild ass (''Equus hydruntinus'') (survived in refugia in Anatolia until late Holocene)

**** '' Equus ovodovi'' (survived in refugia in North China until late Holocene)

*** All native Rhinoceros

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

(Rhinocerotidae) spp.

**** '' Elasmotherium''

**** Woolly rhinoceros

The woolly rhinoceros (''Coelodonta antiquitatis'') is an extinct species of rhinoceros that inhabited northern Eurasia during the Pleistocene epoch. The woolly rhinoceros was a member of the Pleistocene megafauna. The woolly rhinoceros was larg ...

(''Coelodonta antiquitatis'')

**** ''Stephanorhinus

''Stephanorhinus'' is an extinct genus of two-horned rhinoceros native to Eurasia and North Africa that lived during the Late Pliocene to Late Pleistocene. Species of ''Stephanorhinus'' were the predominant and often only species of rhinoceros in ...

'' spp.

***** Merck's rhinoceros

''Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis'', also known as Merck's rhinoceros (or the less commonly, the forest rhinoceros) is an extinct species of rhinoceros belonging to the genus ''Stephanorhinus'' that lived from the end of the Early Pleistocene (arou ...

(''Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis'')

***** Narrow-nosed rhinoceros

The narrow-nosed rhinoceros (''Stephanorhinus hemitoechus''), also known as the steppe rhinoceros is an extinct species of rhinoceros belonging to the genus '' Stephanorhinus'' that lived in western Eurasia, including Europe, and West Asia, as ...

(''Stephanorhinus hemiotoechus'')

* Carnivora

** ''Caniformia

Caniformia is a suborder within the order Carnivora consisting of "dog-like" carnivorans. They include Canidae, dogs (Wolf, wolves, foxes, etc.), bears, raccoons, and Mustelidae, mustelids. The Pinnipedia (pinniped, seals, walruses and sea lions) ...

''

*** ''Canidae

Canidae (; from Latin, ''canis'', "dog") is a family (biology), biological family of caniform carnivorans, constituting a clade. A member of this family is also called a canid (). The family includes three subfamily, subfamilies: the Caninae, a ...

''

**** Caninae

Caninae (whose members are known as canines () is the only living subfamily within Canidae, alongside the extinct Borophaginae and Hesperocyoninae. They first appeared in North America, during the Oligocene around 35 million years ago, subsequent ...

***** Wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the grey wolf or gray wolf, is a canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, including the dog and dingo, though gr ...

****** Cave wolf (''Canis lupus spelaeus'')

****** Dire wolf

The dire wolf (''Aenocyon dirus'' ) is an Extinction, extinct species of Caninae, canine which was native to the Americas during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene epochs (125,000–10,000 years ago). The species was named in 1858, four y ...

(''Aenocyon dirus'')

***** Dhole

The dhole ( ; ''Cuon alpinus'') is a canid native to South, East and Southeast Asia. It is anatomically distinguished from members of the genus ''Canis'' in several aspects: its skull is convex rather than concave in profile, it lacks a third ...

s

****** European dhole (''Cuon alpinus europaeus'')

***** Sardinian dhole (''Cynotherium sardous'')

*** Arctoidea

Arctoidea is an Order (biology), infraorder of mostly Carnivore, carnivorous mammals which include the extinct Hemicyoninae, Hemicyonidae (dog-bears), and the extant Musteloidea (weasels, raccoons, skunks, red pandas), Pinniped, Pinnipedia (seals ...

**** Various ''Ursus'' spp.

***** Steppe brown bear (''Ursus arctos'' "''priscus''")

***** Gamssulzen cave bear (''Ursus ingressus'')

***** Pleistocene small cave bear (''Ursus rossicus'')

***** Cave bear

The cave bear (''Ursus spelaeus'') is a prehistoric species of bear that lived in Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene and became extinct about 24,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum.

Both the word ''cave'' and the scientific name '' ...

(''Ursus spelaeus'')

***** Giant polar bear (''Ursus maritimus tyrannus'')

**** Musteloidea

Musteloidea is a superfamily (taxonomy), superfamily of carnivoran mammals united by shared characteristics of the skull and teeth. Musteloids are the sister group of pinnipeds, the group which includes seals.

Musteloidea comprises the following ...

***** Mustelidae

The Mustelidae (; from Latin , weasel) are a diverse family of carnivora, carnivoran mammals, including weasels, badgers, otters, polecats, martens, grisons, and wolverines. Otherwise known as mustelids (), they form the largest family in the s ...

****** Several otter

Otters are carnivorous mammals in the subfamily Lutrinae. The 13 extant otter species are all semiaquatic, aquatic, or marine. Lutrinae is a branch of the Mustelidae family, which includes weasels, badgers, mink, and wolverines, among ...

(Lutrinae) spp.

******* Robust Pleistocene European otter (''Cyrnaonyx'')

******* '' Algarolutra''

******* Sardinian giant otter (''Megalenhydris barbaricina'')

******* Sardinian dwarf otter (''Sardolutra'')

******* Cretan otter (''Lutrogale cretensis'')

** ''Feliformia

Feliformia is a suborder within the order Carnivora consisting of "cat-like" carnivorans, including Felidae, cats (large and small), hyenas, mongooses, viverrids, and related taxa. Feliformia stands in contrast to the other suborder of Carnivora, ...

''

*** Various Felidae

Felidae ( ) is the Family (biology), family of mammals in the Order (biology), order Carnivora colloquially referred to as cats. A member of this family is also called a felid ( ).

The 41 extant taxon, extant Felidae species exhibit the gre ...

(cats) spp.

**** '' Homotherium latidens'' (sometimes called the scimitar-toothed cat)

**** Cave lynx (''Lynx pardinus spelaeus'')

**** Issoire lynx (''Lynx issiodorensis'')

**** ''Panthera

''Panthera'' is a genus within the family (biology), family Felidae, and one of two extant genera in the subfamily Pantherinae. It contains the largest living members of the cat family. There are five living species: the jaguar, leopard, lion, ...

'' spp.

***** Cave lion (''Panthera spelaea'')

***** European ice age leopard Leopards have a long history in Europe, spanning from the Early-Middle Pleistocene transition, around 1.2-0.6 million years ago, until the end of the Late Pleistocene, around 12,000 years ago, and possibly later into the early Holocene. Remains of ...

(''Panthera pardus spelaea'')

*** Hyaenidae (hyenas)

**** Cave hyena (''Crocuta crocuta spelaea'' and ''Crocuta crocuta ultima'')

****'' "Hyaena" prisca''

* All native Elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

(Elephantidae) spp.

** ''Mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

s''

*** Woolly mammoth

The woolly mammoth (''Mammuthus primigenius'') is an extinct species of mammoth that lived from the Middle Pleistocene until its extinction in the Holocene epoch. It was one of the last in a line of mammoth species, beginning with the African ...

(''Mammuthus primigenius'')

*** Dwarf Sardinian mammoth (''Mammuthus lamarmorai'')

** Straight-tusked elephant

The straight-tusked elephant (''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'') is an extinct species of elephant that inhabited Europe and Western Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle and Late Pleistocene. One of the largest known elephant species, mature full ...

(''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'') (Europe)

** '' Palaeoloxodon naumanni'' (Japan, possibly also Korea and northern China)

** '' Palaeoloxodon huaihoensis'' (China)

** Dwarf elephant

Dwarf elephants are prehistoric members of the order Proboscidea which, through the process of allopatric speciation on islands, evolved much smaller body sizes (around shoulder height) in comparison with their immediate ancestors. Dwarf elephant ...

*** '' Palaeoloxodon creutzburgi'' (Crete)

*** Cyprus dwarf elephant (''Palaeoloxodon cypriotes'')

*** '' Palaeoloxodon mnaidriensis'' (Sicily)

* Rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and Mandible, lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal specie ...

s

** ''Allocricetus bursae''

** '' Cricetus major'' (alternatively ''Cricetus cricetus major'')

** '' Dicrostonyx gulielmi'' (ancestor to the Arctic lemming

The Arctic lemming (''Dicrostonyx torquatus'') is a species of rodent in the family Cricetidae.

Although generally classified as a "least concern" species, the Novaya Zemlya subspecies ''(Dicrostonyx torquatus ungulatus)'' is considered a vulne ...

)

** Giant Eurasian porcupine (''Hystrix refossa'')

** ''Leithia

''Leithia'' is an extinct genus of giant dormice from the Pleistocene of the Mediterranean islands of Malta and Sicily. It is considered an example of island gigantism. ''Leithia melitensis'' is the largest known species of dormouse, living or e ...

'' spp. (Maltese and Sicilian giant dormouse)

** '' Marmota paleocaucasica''

** '' Microtus grafi''

** ''Mimomys

''Mimomys'' is an extinct genus of voles that lived in Eurasia and North America during the Plio-Pleistocene. It is believed that one of the many species belonging to this genus gave rise to the modern water voles ''(Arvicola)''. Several other pr ...

'' spp.

*** ''M. pyrenaicus''

*** ''M. chandolensis''

** '' Pliomys lenki''

** '' Spermophilus citelloides''

** '' Spermophilus severskensis''

** '' Spermophilus superciliosus''

** '' Trogontherium cuvieri'' (large beaver)

** ''Lagomorpha

The lagomorphs () are the members of the taxonomic order Lagomorpha, of which there are two living families: the Leporidae (rabbits and hares) and the Ochotonidae ( pikas). There are 110 recent species of lagomorph, of which 109 species in t ...

''

*** '' Lepus tanaiticus'' (alternatively ''Lepus timidus tanaiticus'')

*** Pika

A pika ( , or ) is a small, mountain-dwelling mammal native to Asia and North America. With short limbs, a very round body, an even coat of fur, and no external tail, they resemble their close relative the rabbit, but with short, rounded ears. ...

(''Ochotona'') spp. e.g.

**** Giant pika (''Ochotona whartoni'')

*** ''Tonomochota'' spp.

**** ''T. khasanensis''

**** ''T. sikhotana''

**** ''T. major''

* Birds

** Yakutian goose (''Anser djuktaiensis'')

** East Asian Ostrich ('' Struthio anderssoni'')

** Various European crane spp. (Genus '' Grus'')

*** ''Grus primigenia''

*** ''Grus melitensis''

** Cretan owl (''Athene cretensis'')

*Primates

** ''Homo

''Homo'' () is a genus of great ape (family Hominidae) that emerged from the genus ''Australopithecus'' and encompasses only a single extant species, ''Homo sapiens'' (modern humans), along with a number of extinct species (collectively called ...

''

*** Denisovan

The Denisovans or Denisova hominins ( ) are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic, and lived, based on current evidence, from 285 thousand to 25 thousand years ago. D ...

s (''Homo'' sp.)

*** Neanderthals

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinction, extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle to Late Plei ...

(''Homo'' (''sapiens'') ''neanderthalensis''; survived until about 40,000 years ago on the Iberian peninsula)

* Reptiles

** '' Solitudo sicula''; survived in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

until about 12,500 years ago.

** '' Lacerta siculimelitensis''; from Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

.

Extinctions in North America were concentrated at the end of the Late Pleistocene, around 13,800–11,400 years Before Present, which were coincident with the onset of the

Younger Dryas

The Younger Dryas (YD, Greenland Stadial GS-1) was a period in Earth's geologic history that occurred circa 12,900 to 11,700 years Before Present (BP). It is primarily known for the sudden or "abrupt" cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, when the ...

cooling period, as well as the emergence of the hunter-gatherer Clovis culture

The Clovis culture is an archaeological culture from the Paleoindian period of North America, spanning around 13,050 to 12,750 years Before Present (BP). The type site is Blackwater Draw locality No. 1 near Clovis, New Mexico, where stone too ...

. The relative importance of human and climactic factors in the North American extinctions has been the subject of significant controversy. Extinctions totalled around 35 genera. The radiocarbon record for North America south of the Alaska-Yukon region has been described as "inadequate" to construct a reliable chronology.

North American extinctions (noted as

North American extinctions (noted as herbivores

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically evolved to feed on plants, especially upon vascular tissues such as foliage, fruits or seeds, as the main component of its diet. These more broadly also encompass animals that eat ...

(H) or carnivores

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose nutrition and energy requirements are met by consumption of animal tissues (mainly mu ...

(C)) included:

* Ungulates

** ''Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals''

*** Various Bovidae

The Bovidae comprise the family (biology), biological family of cloven-hoofed, ruminant mammals that includes Bos, cattle, bison, Bubalina, buffalo, antelopes (including Caprinae, goat-antelopes), Ovis, sheep and Capra (genus), goats. A member o ...

spp.

**** Most forms of Pleistocene bison

A bison (: bison) is a large bovine in the genus ''Bison'' (from Greek, meaning 'wild ox') within the tribe Bovini. Two extant taxon, extant and numerous extinction, extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American ...

(only ''Bison bison'' in North America, and ''Bison bonasus'' in Eurasia, survived)

***** Ancient bison (''Bison antiquus'') (H)

***** Long-horned/Giant bison (''Bison latifrons'') (H)

***** Steppe bison

The steppe bison (''Bison'' ''priscus'', also less commonly known as the steppe wisent and the primeval bison) is an extinct species of bison which lived from the Middle Pleistocene to the Holocene. During the Late Pleistocene, it was widely dist ...

(''Bison priscus'') (H)

***** ''Bison occidentalis

''Bison occidentalis'' is an extinct species of bison that lived in North America, from about 11,700 to 5,000 years ago, spanning the end of the Pleistocene to the mid-Holocene.

Evolution

Some authors consider ''Bison occidentalis'' to be an i ...

'' (H)

**** Several members of ''Caprinae

The subfamily Caprinae, also sometimes referred to as the tribe Caprini, is part of the ruminant family Bovidae, and consists of mostly medium-sized bovids. A member of this subfamily is called a caprine.

Prominent members include sheep and g ...

'' (the muskox

The muskox (''Ovibos moschatus'') is a hoofed mammal of the family Bovidae. Native to the Arctic, it is noted for its thick coat and for the strong odor emitted by males during the seasonal rut, from which its name derives. This musky odor ha ...

survived)

***** Giant muskox (''Praeovibos priscus'') (H)

***** Shrub-ox (''Euceratherium collinum'') (H)

***** Harlan's muskox (''Bootherium bombifrons'') (H)

***** Soergel's ox (''Soergelia mayfieldi'') (H)

***** Harrington's mountain goat (''Oreamnos harringtoni''; smaller and more southern distribution than its surviving relative) (H)

**** Saiga antelope (''Saiga tatarica''; extirpated) (H)

*** Deer

**** Stag-moose (''Cervalces scotti'') (H)

**** American mountain deer (''Odocoileus lucasi'') (H)

**** '' Torontoceros hypnogeos'' (H)

*** Various Antilocapridae

The Antilocapridae are a family of ruminant artiodactyls endemic to North America. Their closest extant relatives are the giraffids. Only one species, the pronghorn (''Antilocapra americana''), is living today; all other members of the family ...

genera (pronghorn

The pronghorn (, ) (''Antilocapra americana'') is a species of artiodactyl (even-toed, hoofed) mammal indigenous to interior western and central North America. Though not an antelope, it is known colloquially in North America as the American ante ...

s survived)

**** ''Capromeryx'' (H)

**** ''Stockoceros

''Stockoceros'' is an extinct genus of the North American artiodactyl family Antilocapridae (pronghorns), known from what is now Mexico and the southwestern United States. The genus survived until about 12,000 years ago, and was present when Pale ...

'' (H)

**** ''Tetrameryx

''Tetrameryx'' is an extinct genus of the North American artiodactyl family Antilocapridae, known from Mexico, the western United States, and Saskatchewan in Canada.

Taxonomy

The name means "four ornedruminant", referring to the division of e ...

'' (H)

**** Pacific pronghorn (''Antilocapra pacifica'') (H)

*** Several peccary

Peccaries (also javelinas or skunk pigs) are pig-like ungulates of the family Tayassuidae (New World pigs). They are found throughout Central and South America, Trinidad in the Caribbean, and in the southwestern area of North America. Peccari ...

(Tayassuidae) spp.

**** Flat-headed peccary (''Platygonus'') (H)

**** Long-nosed peccary (''Mylohyus'') (H)

**** Collared peccary

The collared peccary (''Dicotyles tajacu'') is a peccary, a species of artiodactyl (even-toed) mammal in the family Peccary, Tayassuidae found in North America, North, Central America, Central, and South America. It is the only member of the gen ...

(''Dicotyles tajacu''; extirpated, range semi-recolonised) (H) (''Muknalia minimus'' is a junior synonym)

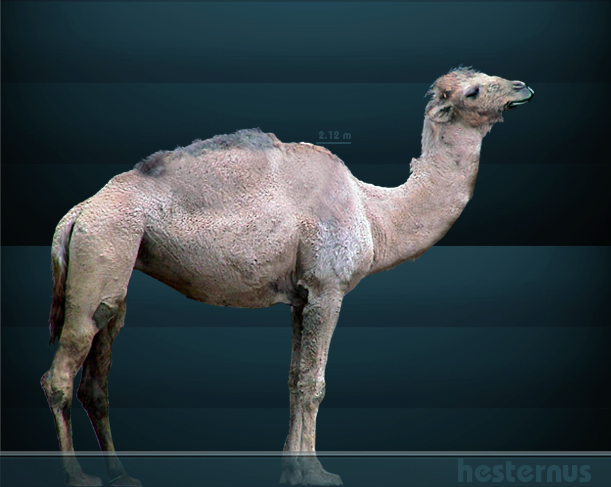

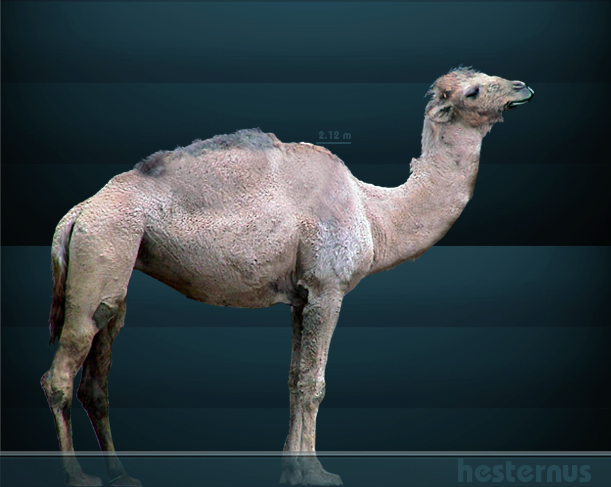

*** Various members of Camelidae

Camelids are members of the biological family Camelidae, the only currently living family in the suborder Tylopoda. The seven extant members of this group are: dromedary camels, Bactrian camels, wild Bactrian camels, llamas, alpacas, vicuñas ...

**** Western camel (''Camelops hesternus'') (H)

**** Stilt legged llamas (''Hemiauchenia'' ssp.) (H)

**** Stout legged llamas (''Palaeolama'' ssp.) (H)

** ''Odd-Toed Hoofed Mammals''

*** All native forms of Equidae

Equidae (commonly known as the horse family) is the Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic Family (biology), family of Wild horse, horses and related animals, including Asinus, asses, zebra, zebras, and many extinct species known only from fossils. The fa ...

**** Caballine true horses (''Equus cf. ferus'') from the Late Pleistocene of North America have historically been assigned to many different species, including '' Equus fraternus'', '' Equus scotti'' and '' Equus lambei,'' but the taxonomy of these horses is unclear, and many of these species may be synonymous with each other, perhaps only representing a single species.

**** Stilt-legged horse (''Haringtonhippus francisci'' / ''Equus francisci''; (H)

*** Tapirs (''Tapirus

''Tapirus'' is a genus of tapir which contains the living tapir species. The Malayan tapir is usually included in ''Tapirus'' as well, although some authorities have moved it into its own genus, ''Acrocodia''.

Extant species

The Kabomani tapir ...

''; three species)

**** California tapir

''Tapirus californicus'', the California tapir, is an extinct species of tapir that inhabited North America during the Pleistocene. It became extinct about 13,000 years ago.

Like other Perissodactyla, perissodactyls, tapirs originated in North A ...

(''Tapirus californicus'') (H)

**** Merriam's tapir (''Tapirus merriami'') (H)

**** Vero tapir (''Tapirus veroensis'') (H)

**Order Notoungulata

Notoungulata is an extinct order of ungulates that inhabited South America from the early Paleocene to the end of the Pleistocene, living from approximately 61 million to 11,000 years ago. Notoungulates were morphologically diverse, with forms re ...

*** '' Mixotoxodon'' (H)

* Carnivora

** ''Feliformia''

*** Several Felidae

Felidae ( ) is the Family (biology), family of mammals in the Order (biology), order Carnivora colloquially referred to as cats. A member of this family is also called a felid ( ).

The 41 extant taxon, extant Felidae species exhibit the gre ...

spp.

**** Sabertooths (Machairodontinae

Machairodontinae (from Ancient Greek μάχαιρα ''Makhaira, machaira,'' a type of Ancient Greek sword and ὀδόντος ''odontos'' meaning tooth) is an extinct subfamily of carnivoran mammals of the cat family Felidae, representing the ...

)

***** ''Smilodon fatalis

''Smilodon'' is an extinct genus of felids. It is one of the best known saber-toothed predators and prehistoric mammals. Although commonly known as the saber-toothed tiger, it was not closely related to the tiger or other modern cats, belon ...

'' (sabertooth cat) (C)

***** '' Homotherium serum'' scimitar-toothed cat (C)

**** American cheetah (''Miracinonyx trumani''; not true cheetah)

**** Cougar

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') (, ''Help:Pronunciation respelling key, KOO-gər''), also called puma, mountain lion, catamount and panther is a large small cat native to the Americas. It inhabits North America, North, Central America, Cent ...

(''Puma concolor''; megafaunal ecomorph

Ecomorphology or ecological morphology is the study of the relationship between the ecological role of an individual and its morphological adaptations. The term "morphological" here is in the anatomical context. Both the morphology and ecology ex ...

extirpated from North America, South American populations recolonised former range) (C)

**** Jaguarundi

The jaguarundi (''Herpailurus yagouaroundi''; or ) is a wild felidae, cat native to the Americas. Its range extends from central Argentina in the south to northern Mexico, through Central America, Central and South America east of the Andes. T ...

(''Herpailurus yagouaroundi''; extirpated, range semi-recolonised) (C)

**** Margay

The margay (''Leopardus wiedii'') is a small wild cat native to Mexico, Central and South America. A solitary and nocturnal felid, it lives mainly in primary evergreen and deciduous forest.

Until the 1990s, margays were hunted for the wildl ...

(''Leopardus weidii''; extirpated) (C)

**** Ocelot

The ocelot (''Leopardus pardalis'') is a medium-sized spotted Felidae, wild cat that reaches at the shoulders and weighs between on average. It is native to the southwestern United States, Mexico, Central America, Central and South America, ...

(''Leopardus pardalis''; extirpated, range marginally recolonised) (C)

**** Jaguar

The jaguar (''Panthera onca'') is a large felidae, cat species and the only extant taxon, living member of the genus ''Panthera'' that is native to the Americas. With a body length of up to and a weight of up to , it is the biggest cat spe ...

s

***** Pleistocene North American jaguar (''Panthera onca augusta''; range semi-recolonised by other subspecies) (C)

***** '' North America Jaguar''

***** '' Panthera balamoides'' (dubious, suggested to be a junior synonym of the short faced bear ''Arctotherium

''Arctotherium'' ("bear beast") is an extinct genus of the Pleistocene Tremarctinae, short-faced bears endemic to Central America, Central and South America. ''Arctotherium'' migrated from North America to South America during the Great American In ...

'')

**** Lion

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large Felidae, cat of the genus ''Panthera'', native to Sub-Saharan Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body (biology), body; a short, rounded head; round ears; and a dark, hairy tuft at the ...

s

***** American lion

The American lion (''Panthera atrox'' (), with the species name meaning "savage" or "cruel", also called the North American lion) is an extinct pantherine cat native to North America during the Late Pleistocene from around 129,000 to 12,800 y ...

(''Panthera atrox'') (C)

***** Cave lion (''Panthera spelaea''; present only in Alaska and Yukon) (C)

** ''Caniformia''

*** Canidae

**** Dire wolf