Proteasome on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Proteasomes are

Proteasomes are

The proteasome subcomponents are often referred to by their

The proteasome subcomponents are often referred to by their

In 2012, two independent efforts have elucidated the molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome by single particle electron microscopy. In 2016, three independent efforts have determined the first near-atomic resolution structure of the human 26S proteasome in the absence of substrates by cryo-EM. In 2018, a major effort has elucidated the detailed mechanisms of deubiquitylation, initiation of translocation and processive unfolding of substrates by determining seven atomic structures of substrate-engaged 26S proteasome simultaneously. In the heart of the 19S, directly adjacent to the 20S, are the AAA-ATPases (

In 2012, two independent efforts have elucidated the molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome by single particle electron microscopy. In 2016, three independent efforts have determined the first near-atomic resolution structure of the human 26S proteasome in the absence of substrates by cryo-EM. In 2018, a major effort has elucidated the detailed mechanisms of deubiquitylation, initiation of translocation and processive unfolding of substrates by determining seven atomic structures of substrate-engaged 26S proteasome simultaneously. In the heart of the 19S, directly adjacent to the 20S, are the AAA-ATPases (

The 20S proteasome is both ubiquitous and essential in eukaryotes and archaea. The

The 20S proteasome is both ubiquitous and essential in eukaryotes and archaea. The

13 May 2003. Access date 29 December 2006. See als

FDA Velcade information page

Bortezomib is used in the treatment of

The Yeast 26S Proteasome with list of subunits and pictures

* * * *

Proteasome subunit nomenclature guide3D proteasome structures in the EM Data Bank(EMDB)

*Key points o

proteasome

function {{Authority control Proteins Protein complexes Organelles Apoptosis

Proteasomes are

Proteasomes are protein complex

A protein complex or multiprotein complex is a group of two or more associated polypeptide chains. Protein complexes are distinct from multienzyme complexes, in which multiple catalytic domains are found in a single polypeptide chain.

Protein c ...

es which degrade unneeded or damaged protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s by proteolysis

Proteolysis is the breakdown of proteins into smaller polypeptides or amino acids. Uncatalysed, the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is extremely slow, taking hundreds of years. Proteolysis is typically catalysed by cellular enzymes called protease ...

, a chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the IUPAC nomenclature for organic transformations, chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the pos ...

that breaks peptide bond

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 (carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 (nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein cha ...

s. Enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s that help such reactions are called protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the ...

s.

Proteasomes are part of a major mechanism by which cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

regulate the concentration

In chemistry, concentration is the abundance of a constituent divided by the total volume of a mixture. Several types of mathematical description can be distinguished: '' mass concentration'', ''molar concentration'', ''number concentration'', an ...

of particular proteins and degrade misfolded proteins

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein chain is translated to its native three-dimensional structure, typically a "folded" conformation by which the protein becomes biologically functional. Via an expeditious and reproduci ...

. Proteins are tagged for degradation with a small protein called ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 1980s. Fo ...

. The tagging reaction is catalyzed by enzymes called ubiquitin ligase

A ubiquitin ligase (also called an E3 ubiquitin ligase) is a protein that recruits an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that has been loaded with ubiquitin, recognizes a protein substrate, and assists or directly catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin ...

s. Once a protein is tagged with a single ubiquitin molecule, this is a signal to other ligases to attach additional ubiquitin molecules. The result is a ''polyubiquitin chain'' that is bound by the proteasome, allowing it to degrade the tagged protein. The degradation process yields peptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

A ...

s of about seven to eight amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s long, which can then be further degraded into shorter amino acid sequences and used in synthesizing new proteins.

Proteasomes are found inside all eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s and archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

, and in some bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

.

In eukaryotes, proteasomes are located both in the nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucle ...

and in the cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

.

In structure

A structure is an arrangement and organization of interrelated elements in a material object or system, or the object or system so organized. Material structures include man-made objects such as buildings and machines and natural objects such as ...

, the proteasome is a cylindrical complex containing a "core" of four stacked rings forming a central pore. Each ring is composed of seven individual proteins. The inner two rings are made of seven ''β subunits'' that contain three to seven protease active site

In biology and biochemistry, the active site is the region of an enzyme where substrate molecules bind and undergo a chemical reaction. The active site consists of amino acid residues that form temporary bonds with the substrate (binding site) a ...

s. These sites are located on the interior surface of the rings, so that the target protein must enter the central pore before it is degraded. The outer two rings each contain seven ''α subunits'' whose function is to maintain a "gate" through which proteins enter the barrel. These α subunits are controlled by binding to "cap" structures or ''regulatory particles'' that recognize polyubiquitin tags attached to protein substrates and initiate the degradation process. The overall system of ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation is known as the ubiquitin–proteasome system.

The proteasomal degradation pathway is essential for many cellular processes, including the cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and subs ...

, the regulation of gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. The ...

, and responses to oxidative stress

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily Detoxification, detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances ...

. The importance of proteolytic degradation inside cells and the role of ubiquitin in proteolytic pathways was acknowledged in the award of the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

to Aaron Ciechanover

Aaron Ciechanover ( ; he, אהרן צ'חנובר; born October 1, 1947) is an Israeli biologist who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for characterizing the method that cells use to degrade and recycle proteins using ubiquitin.

Biography

Early ...

, Avram Hershko

Avram Hershko ( he, אברהם הרשקו, Avraham Hershko, hu, Herskó Ferenc Ábrahám; born December 31, 1937) is a Hungarian-Israeli biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004.

Biography

He was born Herskó Ferenc in Karc ...

and Irwin Rose

Irwin Allan Rose (July 16, 1926 – June 2, 2015) was an American biologist. Along with Aaron Ciechanover and Avram Hershko, he was awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation.

Education ...

.

Discovery

Before the discovery of the ubiquitin–proteasome system, protein degradation in cells was thought to rely mainly onlysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle found in many animal cells. They are spherical vesicles that contain hydrolytic enzymes that can break down many kinds of biomolecules. A lysosome has a specific composition, of both its membrane prot ...

s, membrane-bound organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

s with acid

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a sequ ...

ic and protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the ...

-filled interiors that can degrade and then recycle exogenous proteins and aged or damaged organelles. However, work by Joseph Etlinger and Alfred L. Goldberg in 1977 on ATP-dependent protein degradation in reticulocyte

Reticulocytes are immature red blood cells (RBCs). In the process of erythropoiesis (red blood cell formation), reticulocytes develop and mature in the bone marrow and then circulatory system, circulate for about a day in the blood stream before ...

s, which lack lysosomes, suggested the presence of a second intracellular degradation mechanism. This was shown in 1978 to be composed of several distinct protein chains, a novelty among proteases at the time. Later work on modification of histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in turn are wr ...

s led to the identification of an unexpected covalent

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms ...

modification of the histone protein by a bond between a lysine

Lysine (symbol Lys or K) is an α-amino acid that is a precursor to many proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprotonated −C ...

side chain of the histone and the C-terminal

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When the protein is ...

glycine

Glycine (symbol Gly or G; ) is an amino acid that has a single hydrogen atom as its side chain. It is the simplest stable amino acid (carbamic acid is unstable), with the chemical formula NH2‐ CH2‐ COOH. Glycine is one of the proteinogeni ...

residue of ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 1980s. Fo ...

, a protein that had no known function. It was then discovered that a previously identified protein associated with proteolytic degradation, known as ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1), was the same protein as ubiquitin. The proteolytic activities of this system were isolated as a multi-protein complex originally called the multi-catalytic proteinase complex by Sherwin Wilk and Marion Orlowski. Later, the ATP-dependent proteolytic complex that was responsible for ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation was discovered and was called the 26S proteasome.

Much of the early work leading up to the discovery of the ubiquitin proteasome system occurred in the late 1970s and early 1980s at the Technion in the laboratory of Avram Hershko

Avram Hershko ( he, אברהם הרשקו, Avraham Hershko, hu, Herskó Ferenc Ábrahám; born December 31, 1937) is a Hungarian-Israeli biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004.

Biography

He was born Herskó Ferenc in Karc ...

, where Aaron Ciechanover

Aaron Ciechanover ( ; he, אהרן צ'חנובר; born October 1, 1947) is an Israeli biologist who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for characterizing the method that cells use to degrade and recycle proteins using ubiquitin.

Biography

Early ...

worked as a graduate student. Hershko's year-long sabbatical in the laboratory of Irwin Rose

Irwin Allan Rose (July 16, 1926 – June 2, 2015) was an American biologist. Along with Aaron Ciechanover and Avram Hershko, he was awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation.

Education ...

at the Fox Chase Cancer Center

Fox Chase Cancer Center is a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center research facility and hospital located in the Fox Chase section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. The main facilities of the center are loca ...

provided key conceptual insights, though Rose later downplayed his role in the discovery. The three shared the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

for their work in discovering this system.

Although electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

data revealing the stacked-ring structure of the proteasome became available in the mid-1980s, the first structure of the proteasome core particle was not solved by X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

until 1994. In 2018, the first atomic structures of the human 26S proteasome holoenzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as product (ch ...

in complex with a polyubiquitylated protein substrate were solved by cryogenic electron microscopy

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a cryomicroscopy technique applied on samples cooled to cryogenic temperatures. For biological specimens, the structure is preserved by embedding in an environment of vitreous ice. An aqueous sample so ...

, revealing mechanisms by which the substrate is recognized, deubiquitylated, unfolded and degraded by the human 26S proteasome.

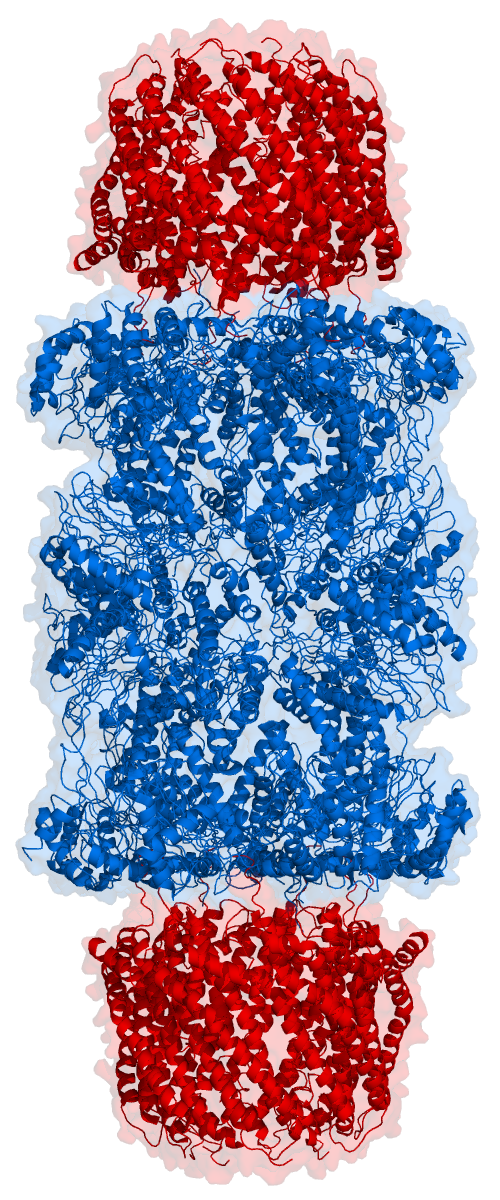

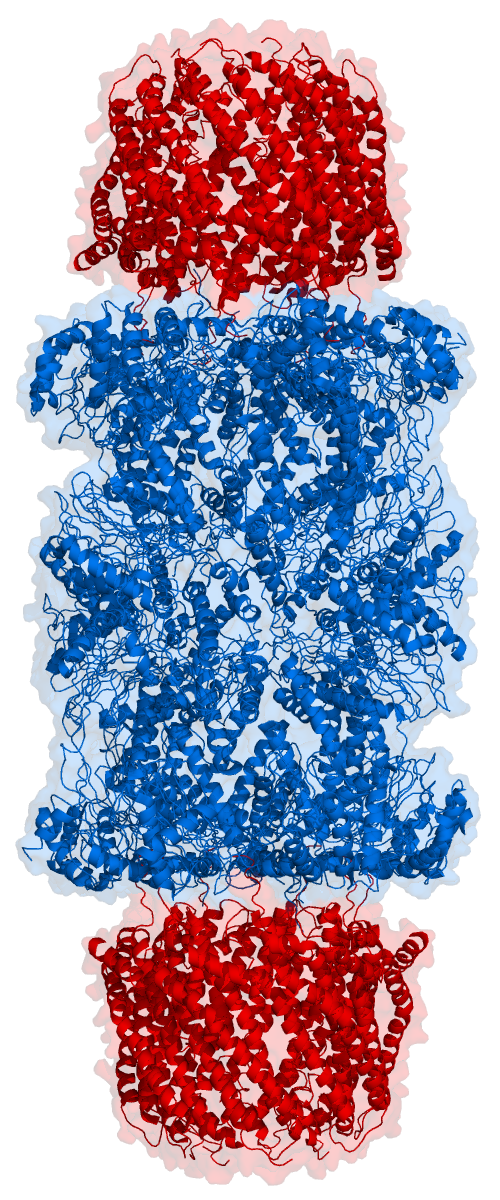

Structure and organization

The proteasome subcomponents are often referred to by their

The proteasome subcomponents are often referred to by their Svedberg

A Svedberg unit or svedberg (symbol S, sometimes Sv) is a non- SI metric unit for sedimentation coefficients. The Svedberg unit offers a measure of a particle's size indirectly based on its sedimentation rate under acceleration (i.e. how fast a p ...

sedimentation coefficient (denoted ''S''). The proteasome most exclusively used in mammals is the cytosolic 26S proteasome, which is about 2000 kilodaltons (kDa) in molecular mass

The molecular mass (''m'') is the mass of a given molecule: it is measured in daltons (Da or u). Different molecules of the same compound may have different molecular masses because they contain different isotopes of an element. The related quanti ...

containing one 20S protein subunit and two 19S regulatory cap subunits. The core is hollow and provides an enclosed cavity in which proteins are degraded; openings at the two ends of the core allow the target protein to enter. Each end of the core particle associates with a 19S regulatory subunit that contains multiple ATPase

ATPases (, Adenosine 5'-TriPhosphatase, adenylpyrophosphatase, ATP monophosphatase, triphosphatase, SV40 T-antigen, ATP hydrolase, complex V (mitochondrial electron transport), (Ca2+ + Mg2+)-ATPase, HCO3−-ATPase, adenosine triphosphatase) are ...

active site

In biology and biochemistry, the active site is the region of an enzyme where substrate molecules bind and undergo a chemical reaction. The active site consists of amino acid residues that form temporary bonds with the substrate (binding site) a ...

s and ubiquitin binding sites; it is this structure that recognizes polyubiquitinated proteins and transfers them to the catalytic core. An alternative form of regulatory subunit called the 11S particle can associate with the core in essentially the same manner as the 19S particle; the 11S may play a role in degradation of foreign peptides such as those produced after infection by a virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

.

20S core particle

The number and diversity of subunits contained in the 20S core particle depends on the organism; the number of distinct and specialized subunits is larger in multicellular than unicellular organisms and larger in eukaryotes than in prokaryotes. All 20S particles consist of four stacked heptameric ring structures that are themselves composed of two different types of subunits; α subunits are structural in nature, whereas β subunits are predominantlycatalytic

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

. The α subunits are pseudoenzyme

Pseudoenzymes are variants of enzymes (usually proteins) that are catalytically-deficient (usually inactive), meaning that they perform little or no enzyme catalysis. They are believed to be represented in all major enzyme families in the kingdo ...

s homologous to β subunits. They are assembled with their N-termini adjacent to that of the β subunits. The outer two rings in the stack consist of seven α subunits each, which serve as docking domains for the regulatory particles and the alpha subunits N-termini () form a gate that blocks unregulated access of substrates to the interior cavity. The inner two rings each consist of seven β subunits and in their N-termini contain the protease active sites that perform the proteolysis reactions. Three distinct catalytic activities were identified in the purified complex: chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like and peptidylglutamyl-peptide hydrolyzing. The size of the proteasome is relatively conserved and is about 150 angstrom

The angstromEntry "angstrom" in the Oxford online dictionary. Retrieved on 2019-03-02 from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/angstrom.Entry "angstrom" in the Merriam-Webster online dictionary. Retrieved on 2019-03-02 from https://www.m ...

s (Å) by 115 Å. The interior chamber is at most 53 Å wide, though the entrance can be as narrow as 13 Å, suggesting that substrate proteins must be at least partially unfolded to enter.

In archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

such as ''Thermoplasma acidophilum

''Thermoplasma acidophilum'' is an archaeon, the type species of its genus. ''T. acidophilum'' was originally isolated from a self-heating coal refuse pile, at pH 2 and 59 °C. Its genome has been sequenced.

It is highly flagellated and gr ...

'', all the α and all the β subunits are identical, whereas eukaryotic proteasomes such as those in yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are estimated to constitut ...

contain seven distinct types of each subunit. In mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s, the β1, β2, and β5 subunits are catalytic; although they share a common mechanism, they have three distinct substrate specificities considered chymotrypsin

Chymotrypsin (, chymotrypsins A and B, alpha-chymar ophth, avazyme, chymar, chymotest, enzeon, quimar, quimotrase, alpha-chymar, alpha-chymotrypsin A, alpha-chymotrypsin) is a digestive enzyme component of pancreatic juice acting in the duodenu ...

-like, trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting these long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the dig ...

-like, and peptidyl-glutamyl peptide-hydrolyzing (PHGH). Alternative β forms denoted β1i, β2i, and β5i can be expressed in hematopoietic

Haematopoiesis (, from Greek , 'blood' and 'to make'; also hematopoiesis in American English; sometimes also h(a)emopoiesis) is the formation of blood cellular components. All cellular blood components are derived from haematopoietic stem cells. ...

cells in response to exposure to pro- inflammatory signal

In signal processing, a signal is a function that conveys information about a phenomenon. Any quantity that can vary over space or time can be used as a signal to share messages between observers. The ''IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing'' ...

s such as cytokine

Cytokines are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling. Cytokines are peptides and cannot cross the lipid bilayer of cells to enter the cytoplasm. Cytokines have been shown to be involved in autocrin ...

s, in particular, interferon gamma

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) is a dimerized soluble cytokine that is the only member of the type II class of interferons. The existence of this interferon, which early in its history was known as immune interferon, was described by E. F. Wheelock ...

. The proteasome assembled with these alternative subunits is known as the '' immunoproteasome'', whose substrate specificity is altered relative to the normal proteasome.

Recently an alternative proteasome was identified in human cells that lack the α3 core subunit. These proteasomes (known as the α4-α4 proteasomes) instead form 20S core particles containing an additional α4 subunit in place of the missing α3 subunit. These alternative 'α4-α4' proteasomes have been known previously to exist in yeast. Although the precise function of these proteasome isoforms is still largely unknown, cells expressing these proteasomes show enhanced resistance to toxicity induced by metallic ions such as cadmium.

19S regulatory particle

The 19S particle in eukaryotes consists of 19 individual proteins and is divisible into two subassemblies, a 9-subunit base that binds directly to the α ring of the 20S core particle, and a 10-subunit lid. Six of the nine base proteins are ATPase subunits from the AAA Family, and an evolutionary homolog of these ATPases exists in archaea, called PAN (proteasome-activating nucleotidase). The association of the 19S and 20S particles requires the binding of ATP to the 19S ATPase subunits, and ATP hydrolysis is required for the assembled complex to degrade folded and ubiquitinated proteins. Note that only the step of substrate unfolding requires energy from ATP hydrolysis, while ATP-binding alone can support all the other steps required for protein degradation (e.g., complex assembly, gate opening, translocation, and proteolysis). In fact, ATP binding to the ATPases by itself supports the rapid degradation of unfolded proteins. However, while ATP hydrolysis is required for unfolding only, it is not yet clear whether this energy may be used in the coupling of some of these steps. In 2012, two independent efforts have elucidated the molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome by single particle electron microscopy. In 2016, three independent efforts have determined the first near-atomic resolution structure of the human 26S proteasome in the absence of substrates by cryo-EM. In 2018, a major effort has elucidated the detailed mechanisms of deubiquitylation, initiation of translocation and processive unfolding of substrates by determining seven atomic structures of substrate-engaged 26S proteasome simultaneously. In the heart of the 19S, directly adjacent to the 20S, are the AAA-ATPases (

In 2012, two independent efforts have elucidated the molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome by single particle electron microscopy. In 2016, three independent efforts have determined the first near-atomic resolution structure of the human 26S proteasome in the absence of substrates by cryo-EM. In 2018, a major effort has elucidated the detailed mechanisms of deubiquitylation, initiation of translocation and processive unfolding of substrates by determining seven atomic structures of substrate-engaged 26S proteasome simultaneously. In the heart of the 19S, directly adjacent to the 20S, are the AAA-ATPases (AAA proteins

AAA, Triple A, or Triple-A is a three-letter initialism or abbreviation which may refer to:

Airports

* Anaa Airport in French Polynesia (IATA airport code AAA)

* Logan County Airport (Illinois) (FAA airport code AAA)

Arts, entertainment, and me ...

) that assemble to a heterohexameric ring of the order Rpt1/Rpt2/Rpt6/Rpt3/Rpt4/Rpt5. This ring is a trimer of dimers: Rpt1/Rpt2, Rpt6/Rpt3, and Rpt4/Rpt5 dimerize via their N-terminal coiled-coils. These coiled-coils protrude from the hexameric ring. The largest regulatory particle non-ATPases Rpn1 and Rpn2 bind to the tips of Rpt1/2 and Rpt6/3, respectively. The ubiquitin receptor Rpn13 binds to Rpn2 and completes the base sub-complex. The lid covers one half of the AAA-ATPase hexamer (Rpt6/Rpt3/Rpt4) and, unexpectedly, directly contacts the 20S via Rpn6 and to lesser extent Rpn5. The subunits Rpn9, Rpn5, Rpn6, Rpn7, Rpn3, and Rpn12, which are structurally related among themselves and to subunits of the COP9 complex and eIF3

Eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3) is a multiprotein complex that functions during the initiation phase of eukaryotic translation. It is essential for most forms of Eukaryotic translation#Cap-dependent initiation, cap-dependent and Eukaryotic t ...

(hence called PCI subunits) assemble to a horseshoe-like structure enclosing the Rpn8/Rpn11 heterodimer. Rpn11, the deubiquitinating enzyme

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), also known as deubiquitinating peptidases, deubiquitinating isopeptidases, deubiquitinases, ubiquitin proteases, ubiquitin hydrolases, ubiquitin isopeptidases, are a large group of proteases that cleave ubiquitin f ...

, is placed at the mouth of the AAA-ATPase hexamer, ideally positioned to remove ubiquitin moieties immediately before translocation of substrates into the 20S. The second ubiquitin receptor identified to date, Rpn10, is positioned at the periphery of the lid, near subunits Rpn8 and Rpn9.

Conformational changes of 19S

The 19S regulatory particle within the 26S proteasome holoenzyme has been observed in six strongly differing conformational states in the absence of substrates to date. A hallmark of the AAA-ATPase configuration in this predominant low-energy state is a staircase- or lockwasher-like arrangement of the AAA-domains. In the presence of ATP but absence of substrate three alternative, less abundant conformations of the 19S are adopted primarily differing in the positioning of the lid with respect to the AAA-ATPase module. In the presence of ATP-γS or a substrate, considerably more conformations have been observed displaying dramatic structural changes of the AAA-ATPase module. Some of the substrate-bound conformations bear high similarity to the substrate-free ones, but they are not entirely identical, particularly in the AAA-ATPase module. Prior to the 26S assembly, the 19S regulatory particle in a free form has also been observed in seven conformational states. Notably, all these conformers are somewhat different and present distinct features. Thus, the 19S regulatory particle can sample at least 20 conformational states under different physiological conditions.

Regulation of the 20S by the 19S

The 19S regulatory particle is responsible for stimulating the 20S to degrade proteins. A primary function of the 19S regulatory ATPases is to open the gate in the 20S that blocks the entry of substrates into the degradation chamber. The mechanism by which the proteasomal ATPase open this gate has been recently elucidated. 20S gate opening, and thus substrate degradation, requires the C-termini of the proteasomal ATPases, which contains a specific motif (i.e., HbYX motif). The ATPases C-termini bind into pockets in the top of the 20S, and tether the ATPase complex to the 20S proteolytic complex, thus joining the substrate unfolding equipment with the 20S degradation machinery. Binding of these C-termini into these 20S pockets by themselves stimulates opening of the gate in the 20S in much the same way that a "key-in-a-lock" opens a door. The precise mechanism by which this "key-in-a-lock" mechanism functions has been structurally elucidated in the context of human 26S proteasome at near-atomic resolution, suggesting that the insertion of five C-termini of ATPase subunits Rpt1/2/3/5/6 into the 20S surface pockets are required to fully open the 20S gate.Other regulatory particles

20S proteasomes can also associate with a second type of regulatory particle, the 11S regulatory particle, a heptameric structure that does not contain any ATPases and can promote the degradation of shortpeptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

A ...

s but not of complete proteins. It is presumed that this is because the complex cannot unfold larger substrates. This structure is also known as PA28, REG, or PA26. The mechanisms by which it binds to the core particle through the C-terminal tails of its subunits and induces α-ring conformational change

In biochemistry, a conformational change is a change in the shape of a macromolecule, often induced by environmental factors.

A macromolecule is usually flexible and dynamic. Its shape can change in response to changes in its environment or oth ...

s to open the 20S gate suggest a similar mechanism for the 19S particle. The expression of the 11S particle is induced by interferon gamma and is responsible, in conjunction with the immunoproteasome β subunits, for the generation of peptides that bind to the major histocompatibility complex

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a large locus on vertebrate DNA containing a set of closely linked polymorphic genes that code for cell surface proteins essential for the adaptive immune system. These cell surface proteins are calle ...

.

Yet another type of non-ATPase regulatory particle is the Blm10 (yeast) or PA200/PSME4

Proteasome activator complex subunit 4 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''PSME4'' gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''g ...

(human). It opens only one α subunit in the 20S gate and itself folds into a dome with a very small pore over it.

Assembly

The assembly of the proteasome is a complex process due to the number of subunits that must associate to form an active complex. The β subunits are synthesized withN-terminal

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

"propeptides" that are post-translationally modified

Post-translational modification (PTM) is the covalent and generally enzyme, enzymatic modification of proteins following protein biosynthesis. This process occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and the golgi apparatus. Proteins are synthesized by r ...

during the assembly of the 20S particle to expose the proteolytic active site. The 20S particle is assembled from two half-proteasomes, each of which consists of a seven-membered pro-β ring attached to a seven-membered α ring. The association of the β rings of the two half-proteasomes triggers threonine

Threonine (symbol Thr or T) is an amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form under biological conditions), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated −COO� ...

-dependent autolysis of the propeptides to expose the active site. These β interactions are mediated mainly by salt bridge

In electrochemistry, a salt bridge or ion bridge is a laboratory device used to connect the oxidation and reduction half-cells of a galvanic cell (voltaic cell), a type of electrochemical cell. It maintains electrical neutrality within the int ...

s and hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the physical property of a molecule that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water (known as a hydrophobe). In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, th ...

interactions between conserved alpha helices

The alpha helix (α-helix) is a common motif in the secondary structure of proteins and is a right hand-helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid located four residues ear ...

whose disruption by mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

damages the proteasome's ability to assemble. The assembly of the half-proteasomes, in turn, is initiated by the assembly of the α subunits into their heptameric ring, forming a template for the association of the corresponding pro-β ring. The assembly of α subunits has not been characterized.

Only recently, the assembly process of the 19S regulatory particle has been elucidated to considerable extent. The 19S regulatory particle assembles as two distinct subcomponents, the base and the lid. Assembly of the base complex is facilitated by four assembly chaperones, Hsm3/S5b, Nas2/p27, Rpn14/PAAF1, and Nas6/ gankyrin (names for yeast/mammals). These assembly chaperones bind to the AAA-ATPase

ATPases (, Adenosine 5'-TriPhosphatase, adenylpyrophosphatase, ATP monophosphatase, triphosphatase, SV40 T-antigen, ATP hydrolase, complex V (mitochondrial electron transport), (Ca2+ + Mg2+)-ATPase, HCO3−-ATPase, adenosine triphosphatase) are ...

subunits and their main function seems to be to ensure proper assembly of the heterohexameric AAA-ATPase

ATPases (, Adenosine 5'-TriPhosphatase, adenylpyrophosphatase, ATP monophosphatase, triphosphatase, SV40 T-antigen, ATP hydrolase, complex V (mitochondrial electron transport), (Ca2+ + Mg2+)-ATPase, HCO3−-ATPase, adenosine triphosphatase) are ...

ring. To date it is still under debate whether the base complex assembles separately, whether the assembly is templated by the 20S core particle, or whether alternative assembly pathways exist. In addition to the four assembly chaperones, the deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp6/Usp14

Ubiquitin-specific protease 14 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''USP14'' gene.

This gene encodes a member of the ubiquitin-specific processing (UBP) family of proteases that is a deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) with His and Cys domains ...

also promotes base assembly, but it is not essential. The lid assembles separately in a specific order and does not require assembly chaperones.

Protein degradation process

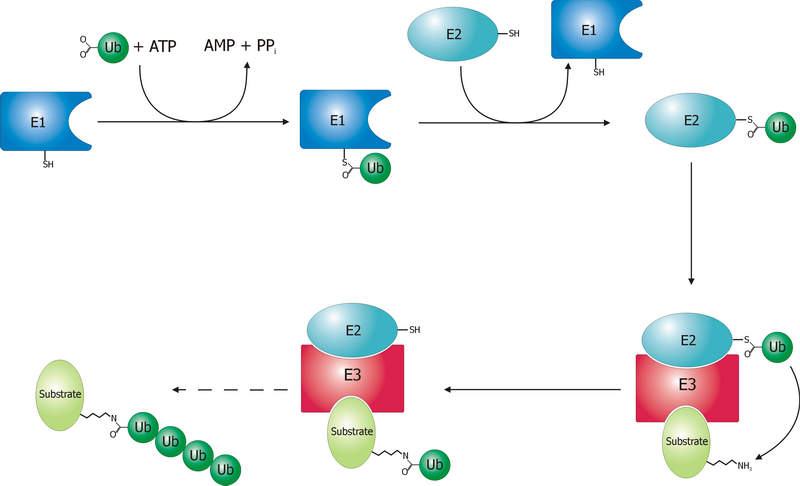

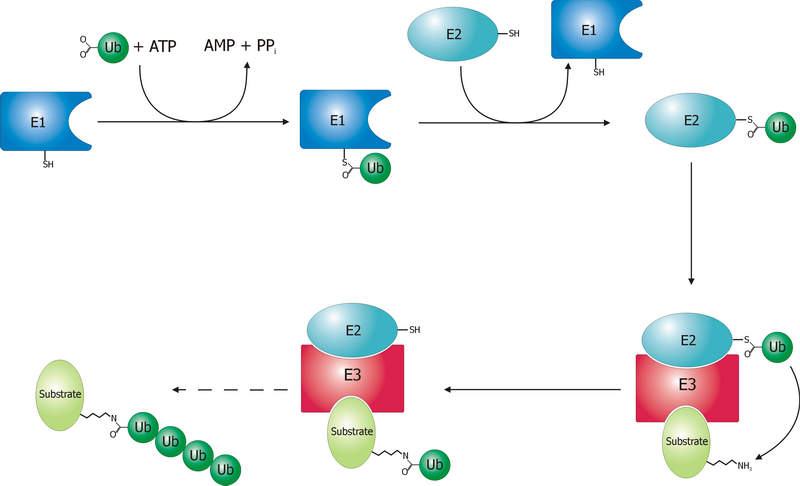

Ubiquitination and targeting

Proteins are targeted for degradation by the proteasome with covalent modification of a lysine residue that requires the coordinated reactions of threeenzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s. In the first step, a ubiquitin-activating enzyme

Ubiquitin-activating enzymes, also known as E1 enzymes, catalyze the first step in the ubiquitination reaction, which (among other things) can target a protein for degradation via a proteasome. This covalent bond of ubiquitin or ubiquitin-like pro ...

(known as E1) hydrolyzes ATP and adenylylates a ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 1980s. Fo ...

molecule. This is then transferred to E1's active-site cysteine

Cysteine (symbol Cys or C; ) is a semiessential proteinogenic amino acid with the formula . The thiol side chain in cysteine often participates in enzymatic reactions as a nucleophile.

When present as a deprotonated catalytic residue, sometime ...

residue in concert with the adenylylation of a second ubiquitin. This adenylylated ubiquitin is then transferred to a cysteine of a second enzyme, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, also known as E2 enzymes and more rarely as ''ubiquitin-carrier enzymes'', perform the second step in the ubiquitination reaction that targets a protein for degradation via the proteasome. The ubiquitination process ...

(E2). In the last step, a member of a highly diverse class of enzymes known as ubiquitin ligase

A ubiquitin ligase (also called an E3 ubiquitin ligase) is a protein that recruits an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that has been loaded with ubiquitin, recognizes a protein substrate, and assists or directly catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin ...

s (E3) recognizes the specific protein to be ubiquitinated and catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to this target protein. A target protein must be labeled with at least four ubiquitin monomers (in the form of a polyubiquitin chain) before it is recognized by the proteasome lid. It is therefore the E3 that confers substrate specificity to this system. The number of E1, E2, and E3 proteins expressed depends on the organism and cell type, but there are many different E3 enzymes present in humans, indicating that there is a huge number of targets for the ubiquitin proteasome system.

The mechanism by which a polyubiquitinated protein is targeted to the proteasome is not fully understood. A few high-resolution snapshots of the proteasome bound to a polyubiquitinated protein suggest that ubiquitin receptors might be coordinated with deubiquitinase Rpn11 for initial substrate targeting and engagement. Ubiquitin-receptor proteins have an N-terminal

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

ubiquitin-like (UBL) domain and one or more ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains. The UBL domains are recognized by the 19S proteasome caps and the UBA domains bind ubiquitin via three-helix bundles. These receptor proteins may escort polyubiquitinated proteins to the proteasome, though the specifics of this interaction and its regulation are unclear.

The ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 1980s. Fo ...

protein itself is 76 amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s long and was named due to its ubiquitous nature, as it has a highly conserved sequence and is found in all known eukaryotic organisms. The genes encoding ubiquitin in eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s are arranged in tandem repeat

Tandem repeats occur in DNA when a pattern of one or more nucleotides is repeated and the repetitions are directly adjacent to each other. Several protein domains also form tandem repeats within their amino acid primary structure, such as armadil ...

s, possibly due to the heavy transcription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

demands on these genes to produce enough ubiquitin for the cell. It has been proposed that ubiquitin is the slowest-evolving

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation t ...

protein identified to date. Ubiquitin contains seven lysine residues to which another ubiquitin can be ligated, resulting in different types of polyubiquitin chains. Chains in which each additional ubiquitin is linked to lysine 48 of the previous ubiquitin have a role in proteasome targeting, while other types of chains may be involved in other processes.

Deubiquitylation

Ubiquitin chains conjugated to a protein targeted for proteasomal degradation are normally removed by any one of the three proteasome-associated deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs), which are Rpn11, Ubp6/USP14 and UCH37. This process recycles ubiquitin and is essential to maintain the ubiquitin reservoir in cells. Rpn11 is an intrinsic, stoichiometric subunit of the 19S regulatory particle and is essential for the function of 26S proteasome. The DUB activity of Rpn11 is enhanced in the proteasome as compared to its monomeric form. How Rpn11 removes a ubiquitin chain en bloc from a protein substrate was captured by an atomic structure of the substrate-engaged human proteasome in a conformation named EB. Interestingly, this structure also shows how the DUB activity is coupled to the substrate recognition by the proteasomal AAA-ATPase. In contrast to Rpn11, USP14 and UCH37 are the DUBs that do not always associated with the proteasome. In cells, about 10-40% of the proteasomes were found to have USP14 associated. Both Ubp6/USP14 and UCH37 are largely activated by the proteasome and exhibit a very low DUB activity alone. Once activated, USP14 was found to suppress proteasome function by its DUB activity and by inducing parallel pathways of proteasome conformational transitions, one of which turned out to directly prohibit substrate insertion into the AAA-ATPase, as intuitively observed by time-resolved cryogenic electron microscopy. It appears that USP14 regulates proteasome function at multiple checkpoints by both catalytically competing with Rpn11 and allosterically reprogramming the AAA-ATPase states, which is rather unexpected for a DUB. These observations imply that the proteasome regulation may depend on its dynamic transitions of conformational states.Unfolding and translocation

After a protein has been ubiquitinated, it is recognized by the 19S regulatory particle in an ATP-dependent binding step. The substrate protein must then enter the interior of the 20S subunit to come in contact with the proteolytic active sites. Because the 20S particle's central channel is narrow and gated by the N-terminal tails of the α ring subunits, the substrates must be at least partially unfolded before they enter the core. The passage of the unfolded substrate into the core is called ''translocation'' and necessarily occurs after deubiquitination. However, the order in which substrates are deubiquitinated and unfolded is not yet clear. Which of these processes is therate-limiting step

In chemical kinetics, the overall rate of a reaction is often approximately determined by the slowest step, known as the rate-determining step (RDS or RD-step or r/d step) or rate-limiting step. For a given reaction mechanism, the prediction of the ...

in the overall proteolysis reaction depends on the specific substrate; for some proteins, the unfolding process is rate-limiting, while deubiquitination is the slowest step for other proteins. The extent to which substrates must be unfolded before translocation is suggested to be around 20 amino acid residues by the atomic structure of the substrate-engaged 26S proteasome in the deubiquitylation-compatible state, but substantial tertiary structure

Protein tertiary structure is the three dimensional shape of a protein. The tertiary structure will have a single polypeptide chain "backbone" with one or more protein secondary structures, the protein domains. Amino acid side chains may int ...

, and in particular nonlocal interactions such as disulfide bond

In biochemistry, a disulfide (or disulphide in British English) refers to a functional group with the structure . The linkage is also called an SS-bond or sometimes a disulfide bridge and is usually derived by the coupling of two thiol groups. In ...

s, are sufficient to inhibit degradation. The presence of intrinsically disordered protein

In molecular biology, an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) is a protein that lacks a fixed or ordered three-dimensional structure, typically in the absence of its macromolecular interaction partners, such as other proteins or RNA. IDPs rang ...

segments of sufficient size, either at the protein terminus or internally, has also been proposed to facilitate efficient initiation of degradation.

The gate formed by the α subunits prevents peptides longer than about four residues from entering the interior of the 20S particle. The ATP molecules bound before the initial recognition step are hydrolyzed

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water is the nucleophile.

Biological hydrolysis ...

before translocation. While energy is needed for substrate unfolding, it is not required for translocation. The assembled 26S proteasome can degrade unfolded proteins in the presence of a non-hydrolyzable ATP analog, but cannot degrade folded proteins, indicating that energy from ATP hydrolysis is used for substrate unfolding. Passage of the unfolded substrate through the opened gate occurs via facilitated diffusion

Facilitated diffusion (also known as facilitated transport or passive-mediated transport) is the process of spontaneous passive transport (as opposed to active transport) of molecules or ions across a biological membrane via specific transmembra ...

if the 19S cap is in the ATP-bound state.

The mechanism for unfolding of globular protein

In biochemistry, globular proteins or spheroproteins are spherical ("globe-like") proteins and are one of the common protein types (the others being fibrous, disordered and membrane proteins). Globular proteins are somewhat water-soluble (formi ...

s is necessarily general, but somewhat dependent on the amino acid sequence

Protein primary structure is the linear sequence of amino acids in a peptide or protein. By convention, the primary structure of a protein is reported starting from the amino-terminal (N) end to the carboxyl-terminal (C) end. Protein biosynthes ...

. Long sequences of alternating glycine and alanine

Alanine (symbol Ala or A), or α-alanine, is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an amine group and a carboxylic acid group, both attached to the central carbon atom which also carries a methyl group side c ...

have been shown to inhibit substrate unfolding, decreasing the efficiency of proteasomal degradation; this results in the release of partially degraded byproducts, possibly due to the decoupling of the ATP hydrolysis and unfolding steps. Such glycine-alanine repeats are also found in nature, for example in silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

fibroin

Fibroin is an insoluble protein present in silk produced by numerous insects, such as the larvae of ''Bombyx mori'', and other moth genera such as '' Antheraea'', '' Cricula'', '' Samia'' and '' Gonometa''. Silk in its raw state consists of tw ...

; in particular, certain Epstein–Barr virus

The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), formally called ''Human gammaherpesvirus 4'', is one of the nine known human herpesvirus types in the herpes family, and is one of the most common viruses in humans. EBV is a double-stranded DNA virus.

It is b ...

gene products bearing this sequence can stall the proteasome, helping the virus propagate by preventing antigen presentation

Antigen presentation is a vital immune process that is essential for T cell immune response triggering. Because T cells recognize only fragmented antigens displayed on cell surfaces, antigen processing must occur before the antigen fragment, now ...

on the major histocompatibility complex.

Proteolysis

The proteasome functions as anendoprotease

Endopeptidase or endoproteinase are proteolytic peptidases that break peptide bonds of nonterminal amino acids (i.e. within the molecule), in contrast to exopeptidases, which break peptide bonds from end-pieces of terminal amino acids. For this re ...

. The mechanism of proteolysis by the β subunits of the 20S core particle is through a threonine-dependent nucleophilic attack

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

. This mechanism may depend on an associated water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a ...

molecule for deprotonation of the reactive threonine hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

. Degradation occurs within the central chamber formed by the association of the two β rings and normally does not release partially degraded products, instead reducing the substrate to short polypeptides typically 7–9 residues long, though they can range from 4 to 25 residues, depending on the organism and substrate. The biochemical mechanism that determines product length is not fully characterized. Although the three catalytic β subunits have a common mechanism, they have slightly different substrate specificities, which are considered chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like, and peptidyl-glutamyl peptide-hydrolyzing (PHGH)-like. These variations in specificity are the result of interatomic contacts with local residues near the active sites of each subunit. Each catalytic β subunit also possesses a conserved lysine residue required for proteolysis.

Although the proteasome normally produces very short peptide fragments, in some cases these products are themselves biologically active and functional molecules. Certain transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The fu ...

s regulating the expression of specific genes, including one component of the mammalian complex NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) is a protein complex that controls transcription of DNA, cytokine production and cell survival. NF-κB is found in almost all animal cell types and is involved in cellular ...

, are synthesized as inactive precursors whose ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation converts them to an active form. Such activity requires the proteasome to cleave the substrate protein internally, rather than processively degrading it from one terminus. It has been suggested that long loops on these proteins' surfaces serve as the proteasomal substrates and enter the central cavity, while the majority of the protein remains outside. Similar effects have been observed in yeast proteins; this mechanism of selective degradation is known as ''regulated ubiquitin/proteasome dependent processing'' (RUP).

Ubiquitin-independent degradation

Although most proteasomal substrates must be ubiquitinated before being degraded, there are some exceptions to this general rule, especially when the proteasome plays a normal role in the post- translational processing of the protein. The proteasomal activation of NF-κB by processing p105 into p50 via internal proteolysis is one major example. Some proteins that are hypothesized to be unstable due to intrinsically unstructured regions, are degraded in a ubiquitin-independent manner. The most well-known example of a ubiquitin-independent proteasome substrate is the enzymeornithine decarboxylase

The enzyme ornithine decarboxylase (, ODC) catalyzes the decarboxylation of ornithine (a product of the urea cycle) to form putrescine. This reaction is the committed step in polyamine synthesis. In humans, this protein has 461 amino acids and fo ...

. Ubiquitin-independent mechanisms targeting key cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and subs ...

regulators such as p53

p53, also known as Tumor protein P53, cellular tumor antigen p53 (UniProt name), or transformation-related protein 53 (TRP53) is a regulatory protein that is often mutated in human cancers. The p53 proteins (originally thought to be, and often s ...

have also been reported, although p53 is also subject to ubiquitin-dependent degradation. Finally, structurally abnormal, misfolded, or highly oxidized proteins are also subject to ubiquitin-independent and 19S-independent degradation under conditions of cellular stress.

Evolution

The 20S proteasome is both ubiquitous and essential in eukaryotes and archaea. The

The 20S proteasome is both ubiquitous and essential in eukaryotes and archaea. The bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

l order Actinomycetales

The Actinomycetales is an order of Actinomycetota. A member of the order is often called an actinomycete. Actinomycetales are generally gram-positive and anaerobic and have mycelia in a filamentous and branching growth pattern. Some actinomycete ...

, also share homologs of the 20S proteasome, whereas most bacteria possess heat shock

The heat shock response (HSR) is a cell stress response that increases the number of molecular chaperones to combat the negative effects on proteins caused by stressors such as increased temperatures, oxidative stress, and heavy metals. In a normal ...

genes hslV

The heat shock proteins HslV and HslU (HslVU complex; also known as ClpQ and ClpY respectively, or ClpQY) are expressed in many bacteria such as ''E. coli'' in response to cell stress.Ramachandran R, Hartmann C, Song HK, Huber R, Bochtler M. (20 ...

and hslU, whose gene products are a multimeric protease arranged in a two-layered ring and an ATPase. The hslV protein has been hypothesized to resemble the likely ancestor of the 20S proteasome. In general, HslV is not essential in bacteria, and not all bacteria possess it, whereas some protist

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the exc ...

s possess both the 20S and the hslV systems. Many bacteria also possess other homologs of the proteasome and an associated ATPase, most notably ClpP and ClpX. This redundancy explains why the HslUV system is not essential.

Sequence analysis suggests that the catalytic β subunits diverged earlier in evolution than the predominantly structural α subunits. In bacteria that express a 20S proteasome, the β subunits have high sequence identity

In bioinformatics, a sequence alignment is a way of arranging the sequences of DNA, RNA, or protein to identify regions of similarity that may be a consequence of functional, structural, or evolutionary relationships between the sequences. Ali ...

to archaeal and eukaryotic β subunits, whereas the α sequence identity is much lower. The presence of 20S proteasomes in bacteria may result from lateral gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring ( reproduction). ...

, while the diversification of subunits among eukaryotes is ascribed to multiple gene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene. ...

events.

Cell cycle control

Cell cycle progression is controlled by ordered action ofcyclin-dependent kinase

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are the families of protein kinases first discovered for their role in regulating the cell cycle. They are also involved in regulating transcription, mRNA processing, and the differentiation of nerve cells. They a ...

s (CDKs), activated by specific cyclin

Cyclin is a family of proteins that controls the progression of a cell through the cell cycle by activating cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) enzymes or group of enzymes required for synthesis of cell cycle.

Etymology

Cyclins were originally disco ...

s that demarcate phases of the cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and subs ...

. Mitotic cyclins, which persist in the cell for only a few minutes, have one of the shortest life spans of all intracellular proteins. After a CDK-cyclin complex has performed its function, the associated cyclin is polyubiquitinated and destroyed by the proteasome, which provides directionality for the cell cycle. In particular, exit from mitosis

In cell biology, mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is mainta ...

requires the proteasome-dependent dissociation of the regulatory component cyclin B

Cyclin B is a member of the cyclin family. Cyclin B is a mitotic cyclin. The amount of cyclin B (which binds to Cdk1) and the activity of the cyclin B-Cdk complex rise through the cell cycle until mitosis, where they fall abruptly due to degr ...

from the mitosis promoting factor

Maturation-promoting factor (abbreviated MPF, also called mitosis-promoting factor or M-Phase-promoting factor) is the cyclin-Cdk complex that was discovered first in frog eggs. It stimulates the mitotic and meiotic phases of the cell cycle. MPF ...

complex. In vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

cells, "slippage" through the mitotic checkpoint leading to premature M phase

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and subse ...

exit can occur despite the delay of this exit by the spindle checkpoint

The spindle checkpoint, also known as the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), the metaphase checkpoint, or the mitotic checkpoint, is a cell cycle checkpoint during mitosis or meiosis that prevents the separa ...

.

Earlier cell cycle checkpoints such as post-restriction point

The restriction point (R), also known as the Start or G1/S checkpoint, is a cell cycle checkpoint in the G1 phase of the animal cell cycle at which the cell becomes "committed" to the cell cycle, and after which extracellular signals are no long ...

check between G1 phase and S phase

S phase (Synthesis Phase) is the phase of the cell cycle in which DNA is replicated, occurring between G1 phase and G2 phase. Since accurate duplication of the genome is critical to successful cell division, the processes that occur during ...

similarly involve proteasomal degradation of cyclin A

Cyclin A is a member of the cyclin family, a group of proteins that function in regulating progression through the cell cycle. The stages that a cell passes through that culminate in its division and replication are collectively known as the cel ...

, whose ubiquitination is promoted by the anaphase promoting complex

Anaphase-promoting complex (also called the cyclosome or APC/C) is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that marks target cell cycle proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome. The APC/C is a large complex of 11–13 subunit proteins, including a cullin ...

(APC), an E3 ubiquitin ligase

A ubiquitin ligase (also called an E3 ubiquitin ligase) is a protein that recruits an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that has been loaded with ubiquitin, recognizes a protein substrate, and assists or directly catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin ...

. The APC and the Skp1/Cul1/F-box protein complex (SCF complex

Skp, Cullin, F-box containing complex (or SCF complex) is a multi-protein E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that catalyzes the ubiquitination of proteins destined for 26S proteasomal degradation. Along with the anaphase-promoting complex, SCF has impo ...

) are the two key regulators of cyclin degradation and checkpoint control; the SCF itself is regulated by the APC via ubiquitination of the adaptor protein, Skp2, which prevents SCF activity before the G1-S transition.

Individual components of the 19S particle have their own regulatory roles. Gankyrin, a recently identified oncoprotein

An oncogene is a gene that has the potential to cause cancer. In tumor cells, these genes are often mutated, or expressed at high levels.

, is one of the 19S subcomponents that also tightly binds the cyclin-dependent kinase

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are the families of protein kinases first discovered for their role in regulating the cell cycle. They are also involved in regulating transcription, mRNA processing, and the differentiation of nerve cells. They a ...

CDK4 and plays a key role in recognizing ubiquitinated p53

p53, also known as Tumor protein P53, cellular tumor antigen p53 (UniProt name), or transformation-related protein 53 (TRP53) is a regulatory protein that is often mutated in human cancers. The p53 proteins (originally thought to be, and often s ...

, via its affinity for the ubiquitin ligase MDM2. Gankyrin is anti-apoptotic

Apoptosis (from grc, ἀπόπτωσις, apóptōsis, 'falling off') is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms. Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (morphology) and death. These changes includ ...

and has been shown to be overexpressed in some tumor

A neoplasm () is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of tissue. The process that occurs to form or produce a neoplasm is called neoplasia. The growth of a neoplasm is uncoordinated with that of the normal surrounding tissue, and persists ...

cell types such as hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer in adults and is currently the most common cause of death in people with cirrhosis. HCC is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.

It occurs in t ...

.

Like eukaryotes, some archaea also use the proteasome to control cell cycle, specifically by controlling ESCRT The endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) machinery is made up of cytosolic protein complexes, known as ESCRT-0, ESCRT-I, ESCRT-II, and ESCRT-III. Together with a number of accessory proteins, these ESCRT complexes enable a un ...

-III-mediated cell division.

Regulation of plant growth

Inplant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

s, signaling by auxin

Auxins (plural of auxin ) are a class of plant hormones (or plant-growth regulators) with some morphogen-like characteristics. Auxins play a cardinal role in coordination of many growth and behavioral processes in plant life cycles and are essenti ...

s, or phytohormone

Plant hormone (or phytohormones) are signal molecules, produced within plants, that occur in extremely low concentrations. Plant hormones control all aspects of plant growth and development, from embryogenesis, the regulation of organ size, pat ...

s that order the direction and tropism

A tropism is a biological phenomenon, indicating growth or turning movement of a biological organism, usually a plant, in response to an environmental stimulus. In tropisms, this response is dependent on the direction of the stimulus (as oppose ...

of plant growth, induces the targeting of a class of transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The fu ...

repressors known as Aux/IAA proteins for proteasomal degradation. These proteins are ubiquitinated by SCFTIR1, or SCF in complex with the auxin receptor TIR1. Degradation of Aux/IAA proteins derepresses transcription factors in the auxin-response factor (ARF) family and induces ARF-directed gene expression. The cellular consequences of ARF activation depend on the plant type and developmental stage, but are involved in directing growth in roots and leaf veins. The specific response to ARF derepression is thought to be mediated by specificity in the pairing of individual ARF and Aux/IAA proteins.

Apoptosis

Both internal and externalsignals

In signal processing, a signal is a function that conveys information about a phenomenon. Any quantity that can vary over space or time can be used as a signal to share messages between observers. The ''IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing'' ...

can lead to the induction of apoptosis

Apoptosis (from grc, ἀπόπτωσις, apóptōsis, 'falling off') is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms. Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (morphology) and death. These changes incl ...

, or programmed cell death. The resulting deconstruction of cellular components is primarily carried out by specialized proteases known as caspase

Caspases (cysteine-aspartic proteases, cysteine aspartases or cysteine-dependent aspartate-directed proteases) are a family of protease enzymes playing essential roles in programmed cell death. They are named caspases due to their specific cystei ...

s, but the proteasome also plays important and diverse roles in the apoptotic process. The involvement of the proteasome in this process is indicated by both the increase in protein ubiquitination, and of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes that is observed well in advance of apoptosis. During apoptosis, proteasomes localized to the nucleus have also been observed to translocate to outer membrane blebs characteristic of apoptosis.

Proteasome inhibition has different effects on apoptosis induction in different cell types. In general, the proteasome is not required for apoptosis, although inhibiting it is pro-apoptotic in most cell types that have been studied. Apoptosis is mediated through disrupting the regulated degradation of pro-growth cell cycle proteins. However, some cell lines — in particular, primary cultures of quiescent

Quiescence (/kwiˈɛsəns/) is a state of quietness or inactivity. It may refer to:

* Quiescence search, in game tree searching (adversarial search) in artificial intelligence, a quiescent state is one in which a game is considered stable and unl ...

and differentiated cells such as thymocyte

A Thymocyte is an immune cell present in the thymus, before it undergoes transformation into a T cell. Thymocytes are produced as stem cells in the bone marrow and reach the thymus via the blood. Thymopoiesis describes the process which turns thymo ...

s and neuron

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa. N ...

s — are prevented from undergoing apoptosis on exposure to proteasome inhibitors. The mechanism for this effect is not clear, but is hypothesized to be specific to cells in quiescent states, or to result from the differential activity of the pro-apoptotic kinase

In biochemistry, a kinase () is an enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of phosphate groups from high-energy, phosphate-donating molecules to specific substrates. This process is known as phosphorylation, where the high-energy ATP molecule don ...

JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), were originally identified as kinases that bind and phosphorylate c-Jun on Ser-63 and Ser-73 within its transcriptional activation domain. They belong to the mitogen-activated protein kinase family, and ar ...

. The ability of proteasome inhibitors to induce apoptosis in rapidly dividing cells has been exploited in several recently developed chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (often abbreviated to chemo and sometimes CTX or CTx) is a type of cancer treatment that uses one or more anti-cancer drugs (chemotherapeutic agents or alkylating agents) as part of a standardized chemotherapy regimen. Chemotherap ...

agents such as bortezomib

Bortezomib, sold under the brand name Velcade among others, is an anti-cancer medication used to treat multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma. This includes multiple myeloma in those who have and have not previously received treatment. It is ...

and .

Response to cellular stress

In response to cellular stresses – such asinfection

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

, heat shock

The heat shock response (HSR) is a cell stress response that increases the number of molecular chaperones to combat the negative effects on proteins caused by stressors such as increased temperatures, oxidative stress, and heavy metals. In a normal ...

, or oxidative damage

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal r ...

– heat shock protein

Heat shock proteins (HSP) are a family of proteins produced by cells in response to exposure to stressful conditions. They were first described in relation to heat shock, but are now known to also be expressed during other stresses including expo ...

s that identify misfolded or unfolded proteins and target them for proteasomal degradation are expressed. Both Hsp27

Heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27) also known as heat shock protein beta-1 (HSPB1) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''HSPB1'' gene.