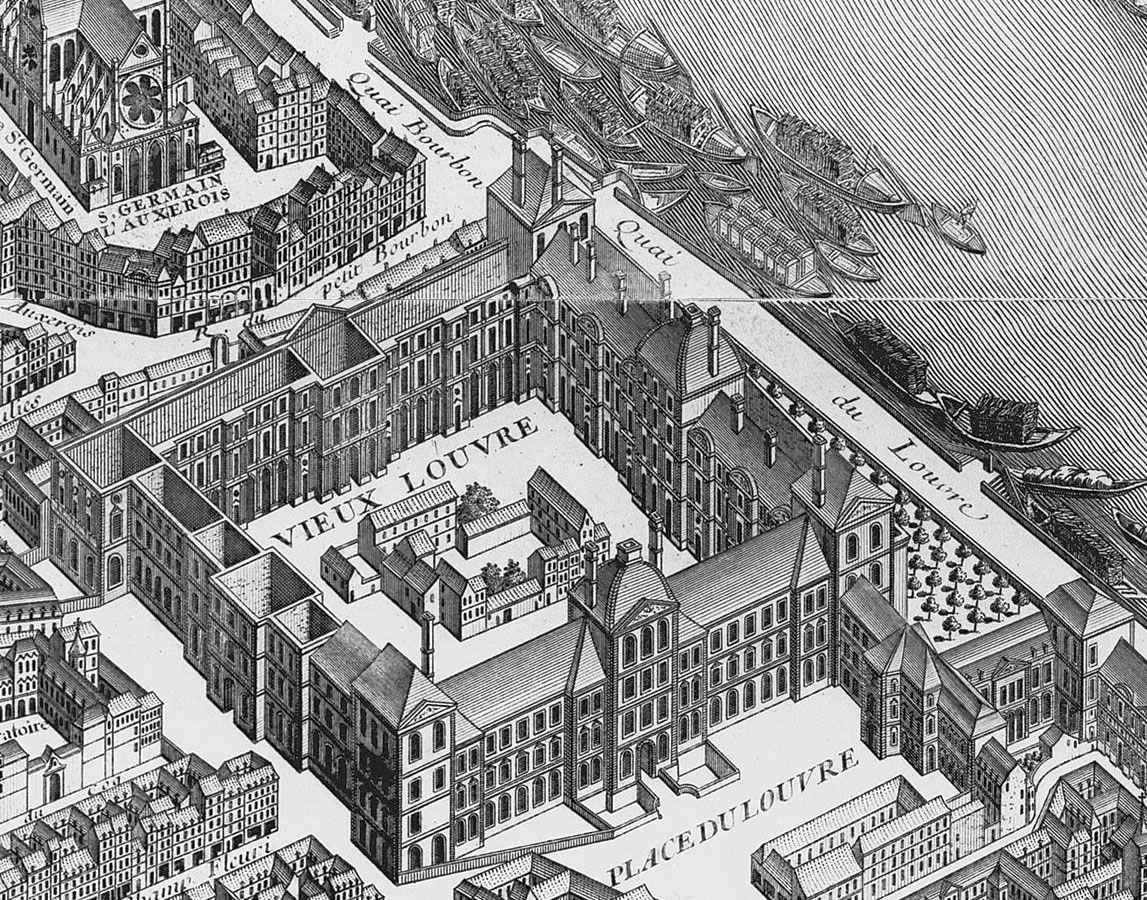

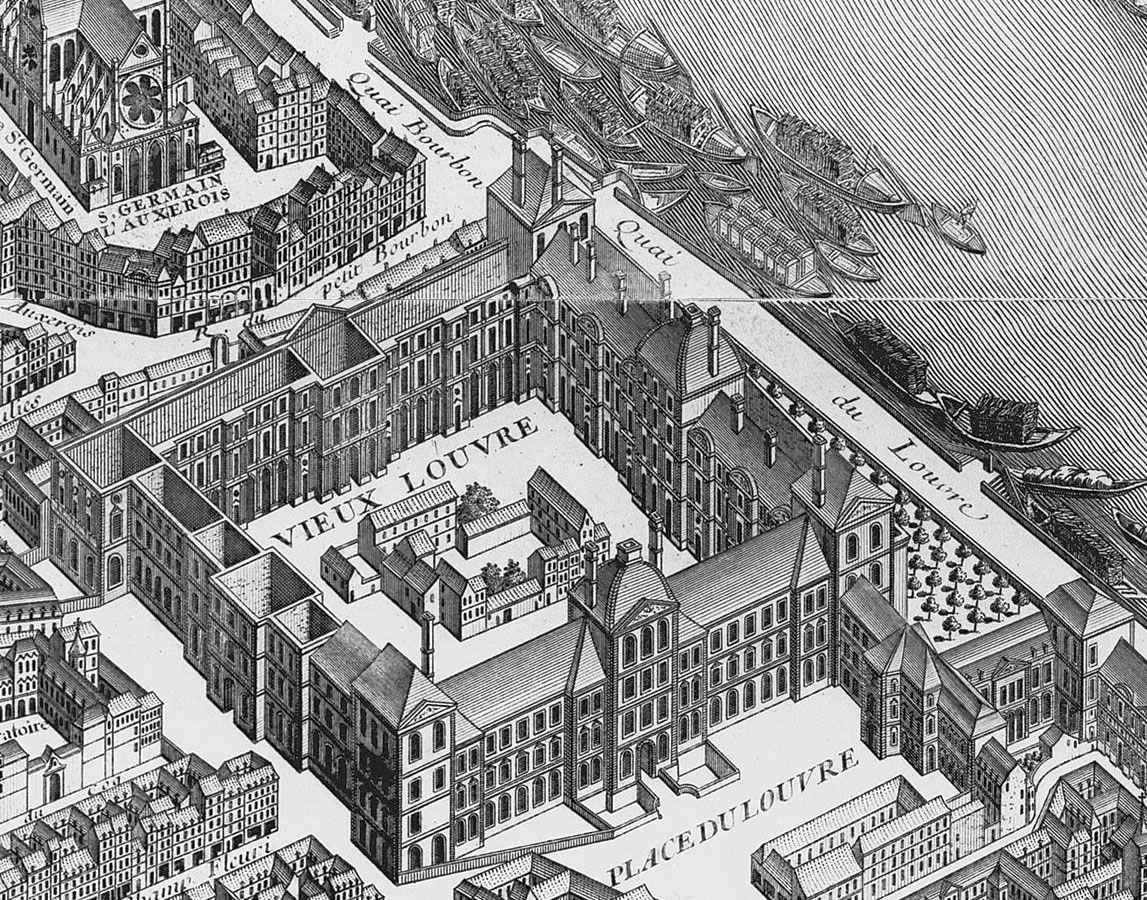

Raguenet showing the south wing with its new facade. The new rows of rooms added behind the new facade in front of Le Vau's older facade remained unroofed, and the topmost stories and steep-pitched roofs of the old pavilions had not yet been removed.

File:3888ParigiLouvre.JPG,

East wing of the Louvre

The Louvre Colonnade is the easternmost façade of the Palais du Louvre in Paris.

It has been celebrated as the foremost masterpiece of French Baroque and Classicism, French Architectural Classicism since its construction, mostly between 1667 and ...

(constructed 1667–1674), one of the most influential classical facades ever built in Europe, as it appeared in 2009

18th century

After the definitive departure of the royal court for Versailles in 1682, the Louvre became occupied by multiple individuals and organizations, either by royal favor or simply

squatting

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building, usually residential, that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there ...

. Its tenants included the infant

Mariana Victoria of Spain

Mariana Victoria of Spain ( pt, Mariana Vitória; 31 March 1718 – 15 January 1781) was an '' Infanta of Spain'' by birth and was later the Queen of Portugal as wife of King Joseph I. She acted as regent of Portugal in 1776–1777, during the l ...

during her stay in Paris in the early 1720s, artists, craftsmen, the Academies, and various royal officers. For example, in 1743 courtier and author

Michel de Bonneval was granted the right to refurbish much of the wing between the and the into his own house on his own expense, including 28 rooms on the ground floor and two mezzanine levels, and an own entrance on the

Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

. After Bonneval's death in 1766 his family was able to keep the house for a few more years. Some new houses were even erected in the middle of the

Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

, but were eventually torn down on the initiative of the

Marquis de Marigny

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman wi ...

in early 1756. A follow-up 1758 decision led to the clearance of buildings on most of what is now the

Place du Louvre in front of the Colonnade, except for the remaining parts of the

Hôtel du Petit-Bourbon

The Hôtel du Petit-Bourbon, a former Parisian town house of the royal family of Bourbon, was located on the right bank of the Seine on the rue d'Autriche, between the Louvre to the west and the Church of Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois to the east ...

which were preserved for a few more years.

Marigny had ambitious plans for the completion of the

Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

, but their execution was cut short in the late 1750s by the adverse developments of the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

.

Jacques-Germain Soufflot

Jacques-Germain Soufflot (, 22 July 1713 – 29 August 1780) was a French architect in the international circle that introduced neoclassicism. His most famous work is the Panthéon in Paris, built from 1755 onwards, originally as a church de ...

in 1759 led the demolition of the upper structures of Le Vau's dome above the Pavillon des Arts, whose chimneys were in poor condition, and designed the northern and eastern passageways () of the Cour Carrée in the late 1750s. The southern was designed by in 1779 and completed in 1780. Three arched were also opened in 1760 under the

Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

, through the and immediately to its west.

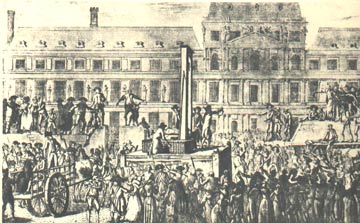

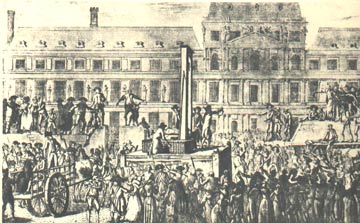

The 1790s were a time of turmoil for the Louvre as for the rest of France. On 5 October 1789, the king and court were forced to return from Versailles and settled in the

Tuileries Palace

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from ...

; many courtiers moved into the Louvre. Many of these in turn emigrated during the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, and more artists swiftly moved into their vacated Louvre apartments.

File:Louvre - Plan du premier étage - Architecture françoise Tome4 Livre6 Pl6.jpg, Plan of the Louvre's first floor in 1756, by Jacques-François Blondel

Jacques-François Blondel (8 January 1705 – 9 January 1774) was an 18th-century French architect and teacher. After running his own highly successful school of architecture for many years, he was appointed Professor of Architecture at the Acad ...

, showing uninhabitable and generally unroofed areas shaded (marked "A")

File:Pierre-Antoine Demachy - Clearing the Area in front of the Louvre Colonnade - Paris Museum Collections.jpg, Demolition of the remaining buildings of the Hôtel du Petit-Bourbon

The Hôtel du Petit-Bourbon, a former Parisian town house of the royal family of Bourbon, was located on the right bank of the Seine on the rue d'Autriche, between the Louvre to the west and the Church of Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois to the east ...

in front of the Louvre, c.1760, by Pierre-Antoine Demachy

Pierre-Antoine Demachy (17 September 1723 – 10 September 1807) was a French artist who specialized in painting ruins, Trompe-l'œil architectural decorations and imaginative scenes of Paris.

Biography

Demachy was born in Paris as the son of a ...

, Musée Carnavalet

The Musée Carnavalet in Paris is dedicated to the history of the city. The museum occupies two neighboring mansions: the Hôtel Carnavalet and the former Hôtel Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau. On the advice of Baron Haussmann, the civil servant wh ...

File:Pierre-Antoine Demachy - Dégagement de la colonnade du Louvre - P88 - Musée Carnavalet.jpg, Another view of the demolitions in front of the Colonnade, by Pierre-Antoine Demachy

Pierre-Antoine Demachy (17 September 1723 – 10 September 1807) was a French artist who specialized in painting ruins, Trompe-l'œil architectural decorations and imaginative scenes of Paris.

Biography

Demachy was born in Paris as the son of a ...

, 1764

19th century

In December 1804,

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

appointed

Pierre Fontaine as architect of the Tuileries and the Louvre. Fontaine had forged a strong professional bond with his slightly younger colleague

Charles Percier

Charles Percier (; 22 August 1764 – 5 September 1838) was a neoclassical French architect, interior decorator and designer, who worked in a close partnership with Pierre François Léonard Fontaine, originally his friend from student days. For ...

.

Between 1805 and 1810

Percier and Fontaine

Percier and Fontaine was a noted partnership between French architects Charles Percier and Pierre François Léonard Fontaine.

History

Together, Percier and Fontaine were inventors and major proponents of the rich and grand, consciously archaeol ...

completed the works of the Cour Carrée that had been left unfinished since the 1670s, despite Marigny's repairs around 1760. They opted to equalize its northern and southern wing with an

attic

An attic (sometimes referred to as a '' loft'') is a space found directly below the pitched roof of a house or other building; an attic may also be called a ''sky parlor'' or a garret. Because attics fill the space between the ceiling of the ...

modeled on the architecture of the

Colonnade wing, thus removing the existing second-floor ornamentation and sculptures, of which some were by

Jean Goujon

Jean Goujon (c. 1510 – c. 1565)Thirion, Jacques (1996). "Goujon, Jean" in ''The Dictionary of Art'', edited by Jane Turner; vol. 13, pp. 225–227. London: Macmillan. Reprinted 1998 with minor corrections: . was a French Renaissance sculpt ...

and his workshop. The Cour Carrée and Colonnade wing were completed in 1808–1809, and Percier and Fontaine created the monumental staircase on the latter's southern and northern ends between 1807 and 1811. Percier and Fontaine also created the monumental decoration of most of the ground-floor rooms around the Cour Carrée, most of which still retain it, including their renovation of Jean Goujon's . On the first floor, they recreated the former of the

Lescot Wing, which had been partitioned in the 18th century, and gave it double height by creating a visitors' gallery in what had formerly been the Lescot Wing's attic.

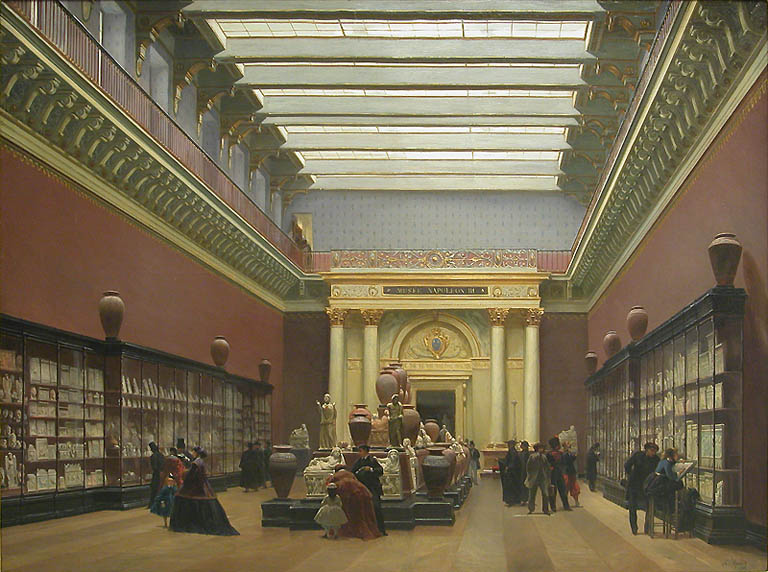

Further west, Percier and Fontaine created the monumental entrance for the Louvre Museum (called since 1804). This opened from what was at the time called the , abutting the Lescot Wing to the west, into the , the monumental room at the northern end of the . The entrance door was dominated by a colossal bronze head of the emperor by

Lorenzo Bartolini

Lorenzo Bartolini (Prato, 7 January 1777 Florence, 20 January 1850) was an Italian sculptor who infused his neoclassicism with a strain of sentimental piety and naturalistic detail, while he drew inspiration from the sculpture of the Florentine ...

, installed in 1805. Visitors could either visit the classical antiquities collection () in Anne of Austria's rooms or in the redecorated ground floor of the Cour Carrée's southern wing to the left, or they could turn right and access Percier and Fontaine's new monumental staircase, leading to both the

Salon Carré

The Salon Carré is an iconic room of the Louvre Palace, created in its current dimensions during a reconstruction of that part of the palace following a fire in February 1661. It gave its name to the longstanding tradition of exhibitions of cont ...

and the (formerly ) on the first floor (replaced in the 1850s by the

Escalier Daru

The Escalier Daru (Daru Staircase), also referred to as Escalier de la Victoire de Samothrace, is one of the largest and most iconic interior spaces of the Louvre Palace in Paris, and of the Louvre Museum within it. Named after Pierre, Count D ...

). The two architects also remade the interior design of the

Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

, in which they created nine sections separated by groups of monumental columns, and a system of roof lighting with lateral

skylight

A skylight (sometimes called a rooflight) is a light-permitting structure or window, usually made of transparent or translucent glass, that forms all or part of the roof space of a building for daylighting and ventilation purposes.

History

Open ...

s.

On the eastern front of the

Tuileries Palace

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from ...

, Percier and Fontaine had the existing buildings cleared away to create a vast open space, the

Cour du Carrousel

The Tuileries Garden (french: Jardin des Tuileries, ) is a public garden located between the Louvre and the Place de la Concorde in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. Created by Catherine de' Medici as the garden of the Tuileries Palace i ...

, which they had closed with an iron fence in 1801. Somewhat ironically, the clearance effort was facilitated by the

Plot of the rue Saint-Nicaise

The Plot of the rue Saint-Nicaise, also known as the plot, was an assassination attempt on the First Consul of France, Napoleon Bonaparte, in Paris on 24 December 1800. It followed the of 10 October 1800, and was one of many Royalist and Cat ...

, a failed bomb attack on Napoleon on 24 December 1800, which damaged many of the neighborhood's building that were later demolished without compensation. In the middle of the Cour du Carrousel, the

Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel

The Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel () ( en, Triumphal Arch of the Carousel) is a triumphal arch in Paris, located in the Place du Carrousel. It is an example of Neoclassical architecture in the Corinthian order. It was built between 1806 and 1808 t ...

was erected in 1806–1808 to commemorate

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's military victories. On 10 April 1810, Percier and Fontaine's plan for the completion of the of uniting the Louvre and the Tuileries was approved, following a design competition among forty-seven participants. Works started immediately afterwards to build an entirely new wing starting from the

Pavillon de Marsan

The Pavillon de Marsan or Marsan Pavilion was built in the 1660s as the northern end of the Tuileries Palace in Paris, and reconstructed in the 1870s after the Tuileries burned down at the end of the Paris Commune. Following the completion of th ...

, with the intent to expand it all the way to the Pavillon de Beauvais on the northwestern corner of the Cour Carrée. By the end of Napoleon's rule the works had progressed up to the . The architectural design of the southern façade of that wing replicated that attributed to

Jacques II Androuet du Cerceau

Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, the younger (1550 – 16 September 1614),Miller 1996, p. 353. was a French architect.

Life and career

He was born in Paris, the son of the eminent French architect and engraver, Jacques I Androuet du Cerceau, and ...

for the western section of the

Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

.

File:Percier Fontaine Louvre Tuileries 1831.jpg, One version of Percier and Fontaine's plan for uniting the Louvre and Tuileries

File:Louvre et Tuileries Percier et Fontaine 1.jpg, Percier and Fontaine's perspective of the completed Louvre viewed from the west

File:Louvre et Tuileries Percier et Fontaine 2.jpg, Percier and Fontaine's perspective of the completed Louvre viewed from the east

Percier and Fontaine

Percier and Fontaine was a noted partnership between French architects Charles Percier and Pierre François Léonard Fontaine.

History

Together, Percier and Fontaine were inventors and major proponents of the rich and grand, consciously archaeol ...

were retained by

Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. He spent twenty-three years in ...

at the beginning of the

Bourbon Restoration, and kept working on the decoration projects they had started under Napoleon. The was opened to the public on 25 August 1819. But there were no further budget allocations for the completion of the Louvre Palace during the reigns of Louis XVIII,

Charles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and Loui ...

and

Louis-Philippe I

Louis Philippe (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850) was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, and the penultimate monarch of France.

As Louis Philippe, Duke of Chartres, he distinguished himself commanding troops during the Revolutionary War ...

, while the kings resided in the

Tuileries

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from ...

. By 1825, Percier and Fontaine's northern wing had only been built up to the , and made no progress in the following 25 years. Further attempts at budget appropriations to complete the Louvre, led by

Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( , ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian. He was the second elected President of France and first President of the French Third Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Rev ...

in 1833 and again in 1840, were rejected by the .

From the early days of the

Second Republic, a greater level of ambition for the Louvre was again signaled. On 24 March 1848, the provisional government published an order that renamed the louvre as the ("People's Palace") and heralded the project to complete it and dedicate it to the exhibition of art and industry as well as the National Library. In a February 1849 speech at the National Assembly,

Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

described the project as making the Louvre into a focal point for world culture, which he referred to a "Mecca of intelligence".

During the Republic's brief existence, the palace was extensively restored by Louvre architect

Félix Duban

Jacques Félix Duban () (14 October 1798, Paris – 8 October 1870, Bordeaux) was a French architect, the contemporary of Jacques Ignace Hittorff and Henri Labrouste.

Life and career

Duban won the Prix de Rome in 1823, the most prestigious aw ...

, especially the exterior façades of the

Petite Galerie and

Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

, on which Duban designed the ornate portal now known as . Meanwhile, Duban restored or completed several of the Louvre's main interior spaces, especially the ,

Galerie d'Apollon

The Galerie d'Apollon is a large and iconic room of the Louvre Palace, on the first (upper) floor of a wing known as the Petite Galerie. Its current setup was first designed in the 1660s. It has been part of the Louvre Museum since the 1790s, was ...

and

Salon Carré

The Salon Carré is an iconic room of the Louvre Palace, created in its current dimensions during a reconstruction of that part of the palace following a fire in February 1661. It gave its name to the longstanding tradition of exhibitions of cont ...

, which

Prince-President Louis Napoleon inaugurated on 5 June 1851 Expropriation arrangements were made for the completion of the Louvre and the

rue de Rivoli

Rue de Rivoli (; English: "Rivoli Street") is a street in central Paris, France. It is a commercial street whose shops include leading fashionable brands. It bears the name of Napoleon's early victory against the Austrian army, at the Battle of Ri ...

, and the remaining buildings that cluttered the space that is now the

Cour Napoléon were cleared away.. No new buildings had been started, however, by the time of the

December 1851 coup d'état.

On this basis,

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

was able to finally unite the Louvre with the Tuileries in a single, coherent building complex.

The plan of the Louvre's expansion were made by

Louis Visconti

Louis Tullius Joachim Visconti (Rome February 11, 1791 – December 29, 1853) was an Italian-born French architect and designer.

Life

Son of the Italian archaeologist and art historian Ennio Quirino Visconti, Visconti designed many Pari ...

, a disciple of Percier, who died suddenly in December 1853 and was succeeded in early 1854 by

Hector Lefuel

Hector-Martin Lefuel (14 November 1810 – 31 December 1880) was a French architect, best known for his work on the Palais du Louvre, including Napoleon III's Louvre expansion and the reconstruction of the Pavillon de Flore.

Biography

He was ...

. Lefuel developed Visconti's plan into a higher and more ornate building concept, and executed it at record speed so that the "" was inaugurated by the emperor on 14 August 1857. The new buildings were arranged around the space then called , later and, since the 20th century,

Cour Napoléon. Before his death, Visconti also had time to rearrange the Louvre's gardens outside the

Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

, namely the to the south, the to the east and the to the north, and also designed the

Orangerie

An orangery or orangerie was a room or a dedicated building on the grounds of fashionable residences of Northern Europe from the 17th to the 19th centuries where orange and other fruit trees were protected during the winter, as a very large ...

and

Jeu de Paume

''Jeu de paume'' (, ; originally spelled ; ), nowadays known as real tennis, (US) court tennis or (in France) ''courte paume'', is a ball-and-court game that originated in France. It was an indoor precursor of tennis played without racquets, a ...

on the western end of the

Tuileries Garden

The Tuileries Garden (french: Jardin des Tuileries, ) is a public garden located between the Louvre and the Place de la Concorde in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. Created by Catherine de' Medici as the garden of the Tuileries Palace in ...

. In the 1860s, Lefuel also demolished the

Pavillon de Flore

The Pavillon de Flore, part of the Palais du Louvre in Paris, France, stands at the southwest end of the Louvre, near the Pont Royal. It was originally constructed in 1607–1610, during the reign of Henry IV, as the corner pavilion between ...

and nearly half of the

Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

, and reconstructed them on a modified design that included the passageway known as the (later , now Porte des Lions), a new for state functions, and the monumental replacing those created in 1760 near the .

At the end of the

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

on 23 May 1871, the

Tuileries Palace

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from ...

was burned down, as also was the Louvre Imperial Library in what is now the Richelieu Wing. The rest of palace, including the museum, was saved by the efforts of troopers, firemen and museum curators.

In the 1870s, the ever-resourceful Lefuel led the repairs to the

Pavillon de Flore

The Pavillon de Flore, part of the Palais du Louvre in Paris, France, stands at the southwest end of the Louvre, near the Pont Royal. It was originally constructed in 1607–1610, during the reign of Henry IV, as the corner pavilion between ...

between 1874 and 1879, reconstructed the wing that had hosted the Louvre Library between 1873 and 1875, and the

Pavillon de Marsan

The Pavillon de Marsan or Marsan Pavilion was built in the 1660s as the northern end of the Tuileries Palace in Paris, and reconstructed in the 1870s after the Tuileries burned down at the end of the Paris Commune. Following the completion of th ...

between 1874 and 1879.

In 1877, a bronze ''Genius of Arts'' by

Antonin Mercié was installed in the place of

Antoine-Louis Barye

Antoine-Louis Barye (24 September 179525 June 1875) was a Romantic French sculptor most famous for his work as an ''animalier'', a sculptor of animals. His son and student was the known sculptor Alfred Barye.

Biography

Born in Paris, France, Ba ...

's equestrian statue of

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

, which had been toppled in September 1870.

Meanwhile, the fate of the Tuileries' ruins kept being debated. Both Lefuel and influential architect

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (; 27 January 181417 September 1879) was a French architect and author who restored many prominent medieval landmarks in France, including those which had been damaged or abandoned during the French Revolution. H ...

advocated their preservation and the building reconstruction, but after the latter died in 1879 and Lefuel in 1880, the

Third Republic opted to erase that memory of the former monarchy. The final decision was made in 1882 and executed in 1883, thus forever changing the Louvre's layout. Later projects to rebuild the Tuileries have resurfaced intermittently but never went very far.

File:The Medusa shown at the Louvre, in color.jpg, The held in 1831 in the eponymous Salon Carré

The Salon Carré is an iconic room of the Louvre Palace, created in its current dimensions during a reconstruction of that part of the palace following a fire in February 1661. It gave its name to the longstanding tradition of exhibitions of cont ...

, painted by and showing Géricault's ''The Raft of the Medusa

''The Raft of the Medusa'' (french: Le Radeau de la Méduse ) – originally titled ''Scène de Naufrage'' (''Shipwreck Scene'') – is an oil painting of 1818–19 by the French Romantic painter and lithographer Théodore Géricault (1791� ...

'' in the middle

File:Petite Galerie, Louvre Museum, Paris February 2016.jpg, The eastern façade of the Petite Galerie following its extensive exterior restoration by Félix Duban

Jacques Félix Duban () (14 October 1798, Paris – 8 October 1870, Bordeaux) was a French architect, the contemporary of Jacques Ignace Hittorff and Henri Labrouste.

Life and career

Duban won the Prix de Rome in 1823, the most prestigious aw ...

File:Demolition of houses for the Place du Carrousel in 1852 – Christ 1949 Fig134.jpg, Demolition of the last buildings on the Place du Carrousel in 1852, with the Tuileries Palace

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from ...

and the Pavillon de Marsan

The Pavillon de Marsan or Marsan Pavilion was built in the 1660s as the northern end of the Tuileries Palace in Paris, and reconstructed in the 1870s after the Tuileries burned down at the end of the Paris Commune. Following the completion of th ...

in the background

File:État actuel de la place du Carrousel.jpg, The North (Richelieu) Wing under construction, with the Pavillon de Flore

The Pavillon de Flore, part of the Palais du Louvre in Paris, France, stands at the southwest end of the Louvre, near the Pont Royal. It was originally constructed in 1607–1610, during the reign of Henry IV, as the corner pavilion between ...

and the Tuileries

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from ...

in the background

File:Pavillon Richelieu, the Louvre, 1850s.jpg, The brand-new photographed in the late 1850s

File:Tuileries Palace in 1871 after the burning during the fights of the Commune de Paris.jpg, The Tuileries Palace was set afire by the Communards during the suppression of the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

in May 1871

File:Tuileries Palace; Pavillon de Flore WDL1252.png, The Tuileries (left) and Pavillon de Flore (right) damaged after the 1871 fire, showing the greater damage to the former than to the latter

A tall was planned in 1884 and erected in 1888 in front of the two gardens on what is now the ''Cour Napoléon''. That initiative carried heavy political symbolism, since

Gambetta was widely viewed as the founder of the

Third Republic, and his outsized celebration in the middle of Napoleon III's landmark thus affirmed the final victory of

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

over

monarchism

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. ...

nearly a century after the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

. Most of the monument's sculptures were in bronze and in 1941 were melted for military use by

German occupying forces. What remained of the Gambetta Monument was dismantled in 1954.

20th century

Some long unfinished parts of Lefuel's expansion were only completed in the early 20th century, such as the Decorative Arts Museum in the Marsan Wing, by

Gaston Redon

Gaston Redon (28 October 1853 – 20 November 1921) was a French architect, teacher, and graphic artist.

Biography

Redon was born in Bordeaux, Aquitaine to a prosperous family, the younger brother of Odilon Redon. Gaston attended the Éco ...

, and the arch between the and , designed by and built in 1910–1914.

Aside from the interior refurbishment of the

Pavillon de Flore

The Pavillon de Flore, part of the Palais du Louvre in Paris, France, stands at the southwest end of the Louvre, near the Pont Royal. It was originally constructed in 1607–1610, during the reign of Henry IV, as the corner pavilion between ...

in the 1960s, there was little change to the Louvre's architecture during most of the 20th century. The most notable was the initiative taken in 1964 by minister

André Malraux

Georges André Malraux ( , ; 3 November 1901 – 23 November 1976) was a French novelist, art theorist, and minister of cultural affairs. Malraux's novel ''La Condition Humaine'' (Man's Fate) (1933) won the Prix Goncourt. He was appointed by P ...

to excavate and reveal the basement level of the

Louvre Colonnade

The Louvre Colonnade is the easternmost façade of the Palais du Louvre in Paris.

It has been celebrated as the foremost masterpiece of French Architectural Classicism since its construction, mostly between 1667 and 1674. The design, dominated by ...

, thus removing the and giving the

Place du Louvre its current shape.

In September 1981, newly elected French President

François Mitterrand

François Marie Adrien Maurice Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was President of France, serving under that position from 1981 to 1995, the longest time in office in the history of France. As First Secretary of the Socialist Party, he ...

proposed the

Grand Louvre

The Grand Louvre refers to the decade-long project initiated by French President François Mitterrand in 1981 of expanding and remodeling the Louvre – both the building and the museum – by moving the French Finance Ministry, which had been ...

plan to move the Finance Ministry out of the Richelieu Wing, allowing the museum to expand dramatically. American architect

I. M. Pei

Ieoh Ming Pei

– website of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners

was awarded the project and in late 1983 proposed a modernist glass pyramid for the central courtyard. The

Louvre Pyramid

The Louvre Pyramid (Pyramide du Louvre) is a large glass and metal structure designed by the Chinese-American architect I. M. Pei. The pyramid is in the main courtyard ( Cour Napoléon) of the Louvre Palace in Paris, surrounded by three smalle ...

and its underground lobby, the , opened to the public on 29 March 1989. A second phase of the Grand Louvre project, completed in 1993, created underground space below the

Place du Carrousel

The Place du Carrousel () is a public square in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, located at the open end of the courtyard of the Louvre Palace, a space occupied, prior to 1883, by the Tuileries Palace. Sitting directly between the museum and the T ...

to accommodate car parks, multi-purpose exhibition halls and a shopping mall named

Carrousel du Louvre. Daylight is provided at the intersection of its axes by the

Louvre Inverted Pyramid (), "a humorous reference to its bigger, right-side-up sister upstairs." The Louvre's new spaces in the reconstructed Richelieu Wing were near-simultaneously inaugurated in November 1993. The third phase of the Grand Louvre, mostly executed by the late 1990s, involved the refurbishment of the museum's galleries in the Sully and Denon Wings where much exhibition space had been freed during the project second phase. The renovation of the

Carrousel Garden

The Tuileries Garden (french: Jardin des Tuileries, ) is a public garden located between the Louvre and the Place de la Concorde in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. Created by Catherine de' Medici as the garden of the Tuileries Palace i ...

was also completed in 2001

21st century

The renovation of the Carrousel Garden was also completed in 2001

Uses

Whereas the name "Louvre Palace" refers to its intermittent role as a monarchical residence, this is neither its original nor its present function. The Louvre has always been associated with French state power and representation, under many modalities that have varied within the vast building and across its long history.

Percier and Fontaine

Percier and Fontaine was a noted partnership between French architects Charles Percier and Pierre François Léonard Fontaine.

History

Together, Percier and Fontaine were inventors and major proponents of the rich and grand, consciously archaeol ...

thus captured something of the long-term identity of the Louvre when they described it in 1833 as "viewed as the shrine of

rench

The Rench is a right-hand tributary of the Rhine in the Ortenau (Baden (Land), Central Baden, Germany). It rises on the southern edge of the Northern Black Forest at Kniebis near Bad Griesbach im Schwarzwald. The source farthest from the mouth is ...

monarchy, now much less devoted to the usual residence of the sovereign than to the great state functions, pomp, festivities, solennities and public ceremonies." Except at the very beginning of its existence, as a fortress, and at the very end (nearly exclusively) as a museum building, the Louvre Palace has continuously hosted a variety of different activities.

Military facility

The Louvre started as a military facility and retained military uses during most of its history. The initial rationale in 1190 for building a reinforced fortress on the western end of the new fortifications of Paris was the lingering threat of English-held

Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

. After the construction of the

Wall of Charles V

The wall of Charles V, built from 1356 to 1383 is one of the city walls of Paris. It was built on the right bank of the river Seine outside the wall of Philippe Auguste. In the 1640s, the western part of the wall of Charles V was demolished and r ...

, the Louvre was still part of the defensive arrangements for the city, as the wall continued along the Seine between it and the farther west, but it was no longer on the frontline. In the next centuries, there was no rationale for specific defenses of the Louvre against foreign invasion, but the palace long retained defensive features such as moats to guard against the political troubles that regularly engulfed Paris. The Louvre hosted a significant

arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostly ...

in the 15th and most of the 16th centuries, until its transfer in 1572 to the facility that is now the

Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal

The Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal (''Library of the Arsenal'', founded 1757) in Paris has been part of the Bibliothèque nationale de France since 1934.

History

The collections of the library originated with the private library of Marc-René, 3rd ...

.

From 1697 on, the French state's collection of

plans-reliefs was stored in the Grande Galerie, of which it occupied all the space by 1754 with about 120 items placed on wooden tables. The plans-reliefs were used to study and prepare defensive and offensive siege operations of the fortified cities and strongholds they represented. In 1777, as plans started being made to create a museum in the Grande Galerie, the plans-reliefs were removed to the

Hôtel des Invalides

The Hôtel des Invalides ( en, "house of invalids"), commonly called Les Invalides (), is a complex of buildings in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, France, containing museums and monuments, all relating to the military history of France, as ...

, where most of them are still displayed in the

Musée des Plans-Reliefs. Meanwhile, a collection of models of ships and navy yards, initially started by naval engineer

Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau

Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau (20 July 1700, Paris13 August 1782, Paris), was a French physician, naval engineer and botanist.

Biography

Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau was born in Paris in 1700, the son of Alexandre Duhamel, lord of Denai ...

, was displayed between 1752 and 1793 in a next to the

Académie des Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at the ...

's rooms on the first floor of the

Lescot Wing. That collection later formed the core of the maritime museum created in 1827, which remained at the Louvre until 1943 and is now the

Musée national de la Marine

The Musée national de la Marine (National Navy Museum) is a maritime museum located in the Palais de Chaillot, Trocadéro, in the 16th arrondissement of Paris. It has annexes at Brest, Port-Louis, Rochefort ( Musée National de la Marine de Roc ...

.

During

Napoleon III's Louvre expansion

The expansion of the Louvre under Napoleon III in the 1850s, known at the time and until the 1980s as the Nouveau Louvre or Louvre de Napoléon III, was an iconic project of the Second French Empire and a centerpiece of its ambitious transforma ...

, the new building program included barracks for the

Imperial Guard

An imperial guard or palace guard is a special group of troops (or a member thereof) of an empire, typically closely associated directly with the Emperor or Empress. Usually these troops embody a more elite status than other imperial forces, in ...

in the new North (Richelieu) Wing, and for the

Cent-gardes Squadron

The Cent-gardes Squadron, ( French: L'Escadron des Cent-gardes), also called ''Cent Gardes à Cheval'' (Hundred Guardsmen on Horseback), was an elite cavalry squadron of the Second French Empire primarily responsible for protecting the person of t ...

in the South (Denon) Wing.

Feudal apex

The round keep of

Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

's Louvre Castle became the symbolic location from which all the king's

fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an Lord, overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a for ...

s depended. The traditional formula for these, that they "depended on the king for his great keep of the Louvre" () remained in use until the 18th century, long after the keep itself had been demolished in the 1520s.

Archive

Philip II also created a permanent repository for the royal archive at the Louvre, following the loss of the French kings' previously itinerant records at the

Battle of Fréteval

The Battle of Fréteval, which took place on 3 July 1194, was a medieval battle, part of the ongoing fighting between Richard the Lionheart and Philip II of France that lasted from 1193 to Richard's death in April 1199. During the battle, the Angl ...

(1194). That archive, known as the

Trésor des Chartes

The ''Trésor des chartes'' ("Charters treasury", la, Thesaurus chartarum et privilegiorum domini regis) are the ancient archives of the French crown. They were spared during the French Revolution and are today stored at the Archives Nationales (F ...

, was relocated under

Louis IX

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the d ...

to the

Palais de la Cité

The Palais de la Cité (), located on the Île de la Cité in the Seine River in the centre of Paris, is a major historic building that was the residence of the Kings of France from the sixth century until the 14th century, and has been the center ...

in 1231.

A number of state archives were again lodged in the Louvre's vacant spaces in the 18th century, e.g. the minutes of the in the attic of the

Lescot Wing, and the archives of the

Conseil du Roi in several ground-floor rooms in the late 1720s. The kingdom's diplomatic archives were kept in the

Pavillon de l'Horloge

The Pavillon de l’Horloge ("Clock Pavilion"), also known as the Pavillon Sully, is a prominent architectural structure located in the center of the western wing of the Cour Carrée of the Palais du Louvre in Paris. Since the late 19th century ...

until their transfer to Versailles in 1763, after which the archives of the

Maison du Roi

The Maison du Roi (, "King's Household") was the royal household of the King of France. It comprised the military, domestic, and religious entourage of the French royal family during the Ancien Régime and Bourbon Restoration.

Organisation ...

and of the soon took their place. In 1770, the archives of the

Chambre des Comptes

Under the French monarchy, the Courts of Accounts (in French ''Chambres des comptes'') were sovereign courts specialising in financial affairs. The Court of Accounts in Paris was the oldest and the forerunner of today's French Court of Audit. ...

were placed in the Louvre's attic, followed by the archives of the

Marshals of France

Marshal of France (french: Maréchal de France, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished (1 ...

in 1778 and those of the

Order of Saint Michael

, status = Abolished by decree of Louis XVI on 20 June 1790Reestablished by Louis XVIII on 16 November 1816Abolished in 1830 after the July RevolutionRecognised as a dynastic order of chivalry by the ICOC

, founder = Louis XI of France

, hig ...

in 1780. In 1825, after the

Conseil d'État had been relocated to the Lemercier Wing, its archives were moved to the entresol below the

Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

, near the .

Prison

The Louvre became a high-profile prison in the immediate aftermath of the

Battle of Bouvines

The Battle of Bouvines was fought on 27 July 1214 near the town of Bouvines in the County of Flanders. It was the concluding battle of the Anglo-French War of 1213–1214. Although estimates on the number of troops vary considerably among mo ...

in July 1214, as

Ferdinand, Count of Flanders

Ferdinand (Portuguese: ''Fernando'', French and Dutch: ''Ferrand''; 24 March 1188 – 27 July 1233) reigned as '' jure uxoris'' Count of Flanders and Hainaut from his marriage to Countess Joan, celebrated in Paris in 1212, until his death. He w ...

was taken into captivity by

Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

. Ferdinand stayed there for 12 years. Other celebrity inmates included

Enguerrand IV de Coucy in the 1250s,

Guy of Flanders

Guy of Dampierre (french: Gui de Dampierre; nl, Gwijde van Dampierre) ( – 7 March 1305, Compiègne) was the Count of Flanders (1251–1305) and Marquis of Namur (1264–1305). He was a prisoner of the French when his Flemings defeated th ...

in 1304, Bishop in 1308–1313,

Louis de Dampierre in 1310,

Enguerrand de Marigny

Enguerrand de Marigny, Baron Le Portier (126030 April 1315) was a French chamberlain and minister of Philip IV.

Early life

He was born at Lyons-la-Forêt in Normandy, of an old Norman family of the smaller baronage called Le Portier, which to ...

in 1314,

John of Montfort

John of Montfort ( xbm, Yann Moñforzh, french: Jean de Montfort) (1295 – 26 September 1345,Etienne de Jouy. Œuvres complètes d'Etienne Jouy'. J. Didot Ainé. p. 373. Château d'Hennebont), sometimes known as John IV of Brittany, and 6th E ...

in 1341–1345,

Charles II of Navarre

Charles II (10 October 1332 – 1 January 1387), called Charles the Bad, was King of Navarre 1349–1387 and Count of Évreux 1343–1387.

Besides the Pyrenean Kingdom of Navarre, Charles had extensive lands in Normandy, inherited from his father ...

in 1356, and

Jean III de Grailly

Jean III de Grailly (aka. John De Grailly, died 7 September 1376), Captal de Buch, , was a Gascon nobleman and a military leader in the Hundred Years' War, who was praised by the chronicler Jean Froissart as an ideal of chivalry.

Biography

...

from 1372 to his death there in 1375. The Louvre was reserved for high-ranking prisoners, while other state captives were held in the

Grand Châtelet The Grand Châtelet was a stronghold in Ancien Régime Paris, on the right bank of the Seine, on the site of what is now the Place du Châtelet; it contained a court and police headquarters and a number of prisons.

The original building on the s ...

. Its use as a prison declined after the completion of the

Bastille

The Bastille (, ) was a fortress in Paris, known formally as the Bastille Saint-Antoine. It played an important role in the internal conflicts of France and for most of its history was used as a state prison by the kings of France. It was sto ...

in the 1370s, but was not ended: for example,

Antoine de Chabannes

Antoine is a French given name (from the Latin ''Antonius'' meaning 'highly praise-worthy') that is a variant of Danton, Titouan, D'Anton and Antonin.

The name is used in France, Switzerland, Belgium, Canada, West Greenland, Haiti, French Guian ...

was held at the Louvre in 1462–1463,

John II, Duke of Alençon

John II of Alençon (Jean II d’Alençon) (2 March 1409 – 8 September 1476) was a French nobleman. He succeeded his father as Duke of Alençon and Count of Perche as a minor in 1415, after the latter's death at the Battle of Agincourt. He ...

in 1474–1476, and

Leonora Dori in 1617 upon the assassination of her husband

Concino Concini

Concino Concini, 1st Marquis d'Ancre (23 November 1569 – 24 April 1617), was an Italian politician, best known for being a minister of Louis XIII of France, as the favourite of Louis's mother, Marie de Medici, Queen of France. In 1617 he was ki ...

at the Louvre's entrance following

Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

's orders.

Treasury

Under Philip II and his immediate successors, the royal treasure was kept in the Paris precinct of the

Knights Templar

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

, located at the present-day

Square du Temple

The Square du Temple is a garden in Paris, France in the 3rd arrondissement, established in 1857. It is one of 24 city squares planned and created by Georges-Eugène Haussmann and Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand. The Square occupies the site o ...

.

King Philip IV created a second treasury at the Louvre, whose first documented evidence dates from 1296. Following the

suppression of the Templars' Order by the same Philip IV in the early 14th century, the Louvre became the sole location of the king's treasury in Paris, which remained there in various forms until the late 17th century. In the 16th century, following the reorganization into the in 1523, it was kept in one of the remaining medieval towers of the Louvre Castle, with a dedicated guard.

Place of worship

By contrast to the

Palais de la Cité

The Palais de la Cité (), located on the Île de la Cité in the Seine River in the centre of Paris, is a major historic building that was the residence of the Kings of France from the sixth century until the 14th century, and has been the center ...

with its soaring

Sainte-Chapelle

The Sainte-Chapelle (; en, Holy Chapel) is a royal chapel in the Gothic style, within the medieval Palais de la Cité, the residence of the Kings of France until the 14th century, on the Île de la Cité in the River Seine in Paris, France.

Co ...

, the religious function was never particularly prominent at the Louvre. The royal household used the nearby

Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois as their

parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

.

[ A chapel of modest size was built by ]Louis IX

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the d ...

in the 1230s in the western wing, whose footprint remains in the southern portion of the Lescot Wing's lower main room. In the 1580s, King Henry III projected to build a large chapel and then a convent in the space between the Louvre and the Seine, but only managed to demolish some of the existing structures on that spot.Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

resided at the Louvre, a new chapel was established on the first floor of the Pavillon de l'Horloge

The Pavillon de l’Horloge ("Clock Pavilion"), also known as the Pavillon Sully, is a prominent architectural structure located in the center of the western wing of the Cour Carrée of the Palais du Louvre in Paris. Since the late 19th century ...

and consecrated on 18 February 1659 as Our Lady of Peace and of Saint Louis, the reference to peace being made in the context of negotiation with Spain that resulted later that year in the Treaty of the Pyrenees

The Treaty of the Pyrenees (french: Traité des Pyrénées; es, Tratado de los Pirineos; ca, Tractat dels Pirineus) was signed on 7 November 1659 on Pheasant Island, and ended the Franco-Spanish War that had begun in 1635.

Negotiations were ...

. This room was of double height, including what is now the pavilion's second floor (or attic). In 1915, the Louvre's architect considered restoring that volume to its original height of more than 12 meters, but did not complete that plan.Percier and Fontaine

Percier and Fontaine was a noted partnership between French architects Charles Percier and Pierre François Léonard Fontaine.

History

Together, Percier and Fontaine were inventors and major proponents of the rich and grand, consciously archaeol ...

had the Salon Carré

The Salon Carré is an iconic room of the Louvre Palace, created in its current dimensions during a reconstruction of that part of the palace following a fire in February 1661. It gave its name to the longstanding tradition of exhibitions of cont ...

temporarily redecorated and converted into a chapel for the wedding of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

and Marie Louise of Austria

french: Marie-Louise-Léopoldine-Françoise-Thérèse-Josèphe-Lucie it, Maria Luigia Leopoldina Francesca Teresa Giuseppa Lucia

, house = Habsburg-Lorraine

, father = Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor

, mother = Maria Theresa of ...

. Meanwhile, in planning the Louvre's expansion and reunion with the Tuileries, Napoleon insisted that a major church should be part of the complex. In 1810 Percier and Fontaine

Percier and Fontaine was a noted partnership between French architects Charles Percier and Pierre François Léonard Fontaine.

History

Together, Percier and Fontaine were inventors and major proponents of the rich and grand, consciously archaeol ...

made plans to build it on the northern side of the present-day Cour Napoléon. Its entrance would have been through a new protruding structure now known as the , facing the symmetrical entrance of the Louvre museum on the southern side in the . The church was to be dedicated to Saint Napoleon, a hitherto obscure figure promoted by Napoleon as patron saint of his incipient dynasty (Napoleon also instituted a national holiday on his birthday on 15 August and called it the ). It was intended to "equal in greatness and magnificence that of the Château de Versailles" (i.e. the Palace Chapel). Percier and Fontaine initiated work on the Rotonde de Beauvais, which was completed during Napoleon III's Louvre expansion

The expansion of the Louvre under Napoleon III in the 1850s, known at the time and until the 1980s as the Nouveau Louvre or Louvre de Napoléon III, was an iconic project of the Second French Empire and a centerpiece of its ambitious transforma ...

, but the construction of the main church building was never started.

Home of national representation

In 1303, the Louvre was the venue of the second-ever meeting of France's Estates General, in the wake of the first meeting held the previous year at Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris (; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris. The cathedral, dedicated to the ...

. The meeting was held in the on the ground floor of the castle's western wing.Hôtel du Petit-Bourbon

The Hôtel du Petit-Bourbon, a former Parisian town house of the royal family of Bourbon, was located on the right bank of the Seine on the rue d'Autriche, between the Louvre to the west and the Church of Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois to the east ...

, in effect a contiguous dependency of the Louvre at that time.

During the Bourbon Restoration, the same first-floor room that had been used for the 1593 meeting, recreated by Percier and Fontaine

Percier and Fontaine was a noted partnership between French architects Charles Percier and Pierre François Léonard Fontaine.

History

Together, Percier and Fontaine were inventors and major proponents of the rich and grand, consciously archaeol ...

as the , was used for the yearly ceremonial opening of the legislative session, which was attended by the king in person – even though ordinary sessions were held in other buildings, namely the Palais Bourbon

The Palais Bourbon () is the meeting place of the National Assembly, the lower legislative chamber of the French Parliament. It is located in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, on the ''Rive Gauche'' of the Seine, across from the Place de la Concor ...

for the Lower Chamber and the Luxembourg Palace

The Luxembourg Palace (french: Palais du Luxembourg, ) is at 15 Rue de Vaugirard in the 6th arrondissement of Paris. It was originally built (1615–1645) to the designs of the French architect Salomon de Brosse to be the royal residence of the ...

for the Chamber of Peers. During the July Monarchy

The July Monarchy (french: Monarchie de Juillet), officially the Kingdom of France (french: Royaume de France), was a liberal constitutional monarchy in France under , starting on 26 July 1830, with the July Revolution of 1830, and ending 23 F ...

, the yearly opening session was located at the Palais Bourbon, but it was brought back to the Louvre under the Second Empire Second Empire may refer to:

* Second British Empire, used by some historians to describe the British Empire after 1783

* Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1396)

* Second French Empire (1852–1870)

** Second Empire architecture, an architectural styl ...

. From 1857 onwards, the new in the South (Denon) Wing of Napoleon III's Louvre expansion

The expansion of the Louvre under Napoleon III in the 1850s, known at the time and until the 1980s as the Nouveau Louvre or Louvre de Napoléon III, was an iconic project of the Second French Empire and a centerpiece of its ambitious transforma ...

was used for that purpose. In the 1860s Napoleon III and Lefuel planned a new venue to replace the in the newly purpose-built , but it was not yet ready for use at the time of the Empire's fall in September 1870.

That role of the Louvre disappeared following the end of the French monarchy in 1870. As a legacy of the temporary relocation of both assemblies in the Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 19 ...

in the 1870s, their joint sessions have been held there ever since, in a room that was purpose-built for that use () and completed in 1875 in the Versailles palace's South Wing.

Royal residence

For centuries, the seat of executive power in Paris had been established at the Palais de la Cité

The Palais de la Cité (), located on the Île de la Cité in the Seine River in the centre of Paris, is a major historic building that was the residence of the Kings of France from the sixth century until the 14th century, and has been the center ...

, at or near the spot where Julian had been proclaimed Roman Emperor back in 360 CE. The political turmoil that followed the death of Philip IV, however, led to the emergence of rival centers of power in and around Paris, of which the Louvre was one. In 1316 Clementia of Hungary

Clementia of Hungary (french: Clémence; 1293–13 October 1328) was Queen of France and Navarre as the second wife of King Louis X.

Life

Clementia was the daughter of Charles Martel of Anjou, the titular King of Hungary, and Clemence of Austri ...

, the widow of recently deceased king Louis X Louis X may refer to:

* Louis X of France, "the Quarreller" (1289–1316).

* Louis X, Duke of Bavaria (1495–1545)

* Louis I, Grand Duke of Hesse (1753–1830).

* Louis Farrakhan (formerly Louis X), head of the Nation of Islam

{{hndis ...

, spent much of her pregnancy at the Château de Vincennes

The Château de Vincennes () is a former fortress and royal residence next to the town of Vincennes, on the eastern edge of Paris, alongside the Bois de Vincennes. It was largely built between 1361 and 1369, and was a preferred residence, after ...

but resided at the Louvre when she gave birth to baby king John I John I may refer to:

People

* John I (bishop of Jerusalem)

* John Chrysostom (349 – c. 407), Patriarch of Constantinople

* John of Antioch (died 441)

* Pope John I, Pope from 523 to 526

* John I (exarch) (died 615), Exarch of Ravenna

* John I o ...

on 15 November 1316, who died five days later. John was thus both the only king of France born at the Louvre, and almost certainly the only one who died there ( Henry IV is now generally believed to have died before his carriage arrived at the Louvre following his fatal stabbing in the rue de la Ferronnerie

The Rue de la Ferronnerie is a street in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, in the Les Halles area.

History

* Before 1229 the name of the street was ''rue de la Charronnerie (ou des Charrons)''. The street had its current name in 1229.

* Henry ...

on 14 May 1610). Philip VI occasionally resided at the Louvre, as documented by some of his letters in mid-1328. King John II is also likely to have resided at the Louvre in 1347, since his daughter Joan of Valois was betrothed there to Henry of Brabant on 21 June 1347, and his short-lived daughter Marguerite was born at the Louvre on 20 September 1347.Charles V of France

Charles V (21 January 1338 – 16 September 1380), called the Wise (french: le Sage; la, Sapiens), was King of France from 1364 to his death in 1380. His reign marked an early high point for France during the Hundred Years' War, with his armi ...

, who had survived the invasion of the Cité by Étienne Marcel

Étienne Marcel (between 1302 and 131031 July 1358) was provost of the merchants of Paris under King John II of France, called John the Good (Jean le Bon). He distinguished himself in the defence of the small craftsmen and guildsmen who made u ...

's partisans in 1358, decided that a less central location would be preferable for his safety. In 1360 he initiated the construction of the Hôtel Saint-Pol

The Hôtel Saint-Pol was a royal residence begun in 1360 by Charles V of France on the ruins of a building constructed by Louis IX. It was used by Charles V and Charles VI. Located on the Right Bank, to the northwest of the Quartier de l'Arsenal ...

, which became his main place of residence in Paris. Upon becoming king in 1364, he started transforming the Louvre into a permanent and more majestic royal residence, even though he stayed there less often than at the Hôtel Saint-Pol. After Charles V's death, his successor Charles VI also mainly stayed at the Hôtel Saint-Pol, but as he was incapacitated by mental illness, his wife Isabeau of Bavaria

Isabeau of Bavaria (or Isabelle; also Elisabeth of Bavaria-Ingolstadt; c. 1370 – September 1435) was Queen of France from 1385 to 1422. She was born into the House of Wittelsbach as the only daughter of Duke Stephen III of Bavaria-Ingol ...

resided in the Louvre and ruled from there.

Later 15th-century kings did not reside in the Louvre, nor did either Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe-Lau ...

or Henry II even as they partly converted the Louvre as a Renaissance palace. The royal family only came back to reside in the newly rebuilt complex following Catherine de' Medici

Catherine de' Medici ( it, Caterina de' Medici, ; french: Catherine de Médicis, ; 13 April 1519 – 5 January 1589) was an Florentine noblewoman born into the Medici family. She was Queen of France from 1547 to 1559 by marriage to King ...

's abandonment of the Hôtel des Tournelles

The hôtel des Tournelles () is a now-demolished collection of buildings in Paris built from the 14th century onwards north of place des Vosges. It was named after its many 'tournelles' or little towers.

It was owned by the kings of France for ...

after her husband Henry II's traumatic death there in July 1559. From then, the king and court would stay mainly in the Louvre between 1559 and 1588 when Henry III escaped Paris, then between 1594 and 1610 under Henry IV. Beyond his minority, Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

did not much reside in the Louvre and preferred the suburban residences of Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Saint-Germain-en-Laye () is a commune in the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France in north-central France. It is located in the western suburbs of Paris, from the centre of Paris.

Inhabitants are called ''Saint-Germanois'' or ''Saint-Ge ...

(where Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

was born on 5 September 1638, and where Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

himself died on 14 May 1643) and Fontainebleau

Fontainebleau (; ) is a commune in the metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is located south-southeast of the centre of Paris. Fontainebleau is a sub-prefecture of the Seine-et-Marne department, and it is the seat of the ''arrondissement ...

(where Louis XIII had been born on 27 September 1601).Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

stayed away from the Louvre during the Fronde

The Fronde () was a series of civil wars in France between 1648 and 1653, occurring in the midst of the Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659), Franco-Spanish War, which had begun in 1635. King Louis XIV confronted the combined opposition of the pr ...

between 1643 and 1652, and departed from there following the death of his mother in 1666. Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

only briefly resided in the Louvre's in 1719, as the Tuileries

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from ...

were undergoing refurbishment.

Both Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

in the 1660s and Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in the 1810s made plans to establish their main residence in the Colonnade Wing, but none of these respective projects came to fruition. Napoleon's attempt led to Percier and Fontaine

Percier and Fontaine was a noted partnership between French architects Charles Percier and Pierre François Léonard Fontaine.

History

Together, Percier and Fontaine were inventors and major proponents of the rich and grand, consciously archaeol ...

's creation of the two monumental staircase on both ends of the wing, but was abandoned in February 1812.

Library

Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infan ...

was renowned for his interest in books (thus his moniker "" which translates as "learned" as well as "wise"), and in 1368 established a library of about 900 volumes on three levels inside the northwestern tower of the Louvre, then renamed from to . The next year he appointed , one of his officials, as the librarian. This action has been widely viewed as foundational, transitioning from the kings' prior practice of keeping books as individual objects to organizing a collection with proper cataloguing; as such, Charles V's library is generally considered a precursor to the French National Library

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

, even though it was dismantled in the 15th century.[

In 1767, a project to relocate the Royal Library from its site on ]rue de Richelieu

The Rue de Richelieu is a long street of Paris, starting in the south of the 1st arrondissement at the Comédie-Française and ending in the north of the 2nd arrondissement. For the first half of the 19th century, before Georges-Eugène Haussman ...

into the Louvre was presented by Jacques-Germain Soufflot

Jacques-Germain Soufflot (, 22 July 1713 – 29 August 1780) was a French architect in the international circle that introduced neoclassicism. His most famous work is the Panthéon in Paris, built from 1755 onwards, originally as a church de ...

, endorsed by Superintendent de Marigny and approved by Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

, but remained stillborn for lack of funds. A similar project was endorsed by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

from February 1805, for which Percier and Fontaine

Percier and Fontaine was a noted partnership between French architects Charles Percier and Pierre François Léonard Fontaine.

History

Together, Percier and Fontaine were inventors and major proponents of the rich and grand, consciously archaeol ...

planned a new Library wing as the centerpiece of their program to fill the space between Louvre and Tuileries, but it was not implemented either.

A separate and smaller was formed from book collections seized during the Revolution and grew during the 19th century's successive regimes. Initially located in the Tuileries in 1800, it was moved to the Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

's entresol in 1805. In 1860 it was moved to a new space created by Lefuel on the second floor of the new North (Richelieu) Wing of Napoleon III's Louvre expansion

The expansion of the Louvre under Napoleon III in the 1850s, known at the time and until the 1980s as the Nouveau Louvre or Louvre de Napoléon III, was an iconic project of the Second French Empire and a centerpiece of its ambitious transforma ...

, whose main pavilion on the rue de Rivoli

Rue de Rivoli (; English: "Rivoli Street") is a street in central Paris, France. It is a commercial street whose shops include leading fashionable brands. It bears the name of Napoleon's early victory against the Austrian army, at the Battle of Ri ...

was accordingly named . The new library was served by an elegant staircase, now , and was decorated by and Alexandre-Dominique Denuelle

Alexandre-Dominique Denuelle, a French decorative painter and architect, was born in Paris in 1818. He studied under Delaroche, and afterwards served on the Commission for Historical Monuments. He died at Florence in 1879. He was largely engaged ...

. It was destroyed by arson in May 1871 at the same time as the Tuileries, and only a few of its precious holdings could be saved.[ and executed in early 2016 after much delay. Several smaller libraries remain in the Louvre: a in the BCMN's former spaces, open to the public; a specialized scholarly library on art of the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East, located on the and thus known as the ; and two other specialized libraries, respectively on painting in the and decorative arts in the .

]

Ceremonial venue

On the occasion of Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV

Charles IV ( cs, Karel IV.; german: Karl IV.; la, Carolus IV; 14 May 1316 – 29 November 1378''Karl IV''. In: (1960): ''Geschichte in Gestalten'' (''History in figures''), vol. 2: ''F–K''. 38, Frankfurt 1963, p. 294), also known as Charle ...

's visit to Paris in 1377–1378, the main banquet was held at the Palais de la Cité