Origin of eukaryotes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Eukaryotes () are

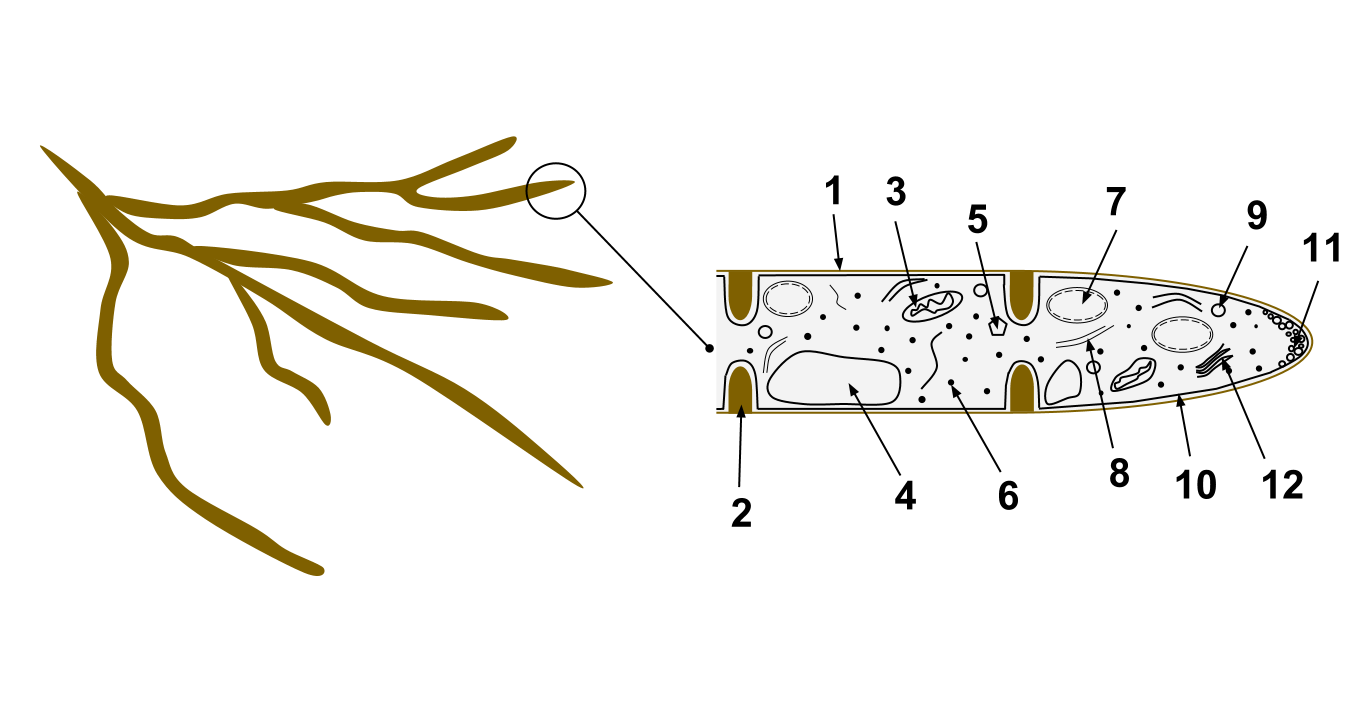

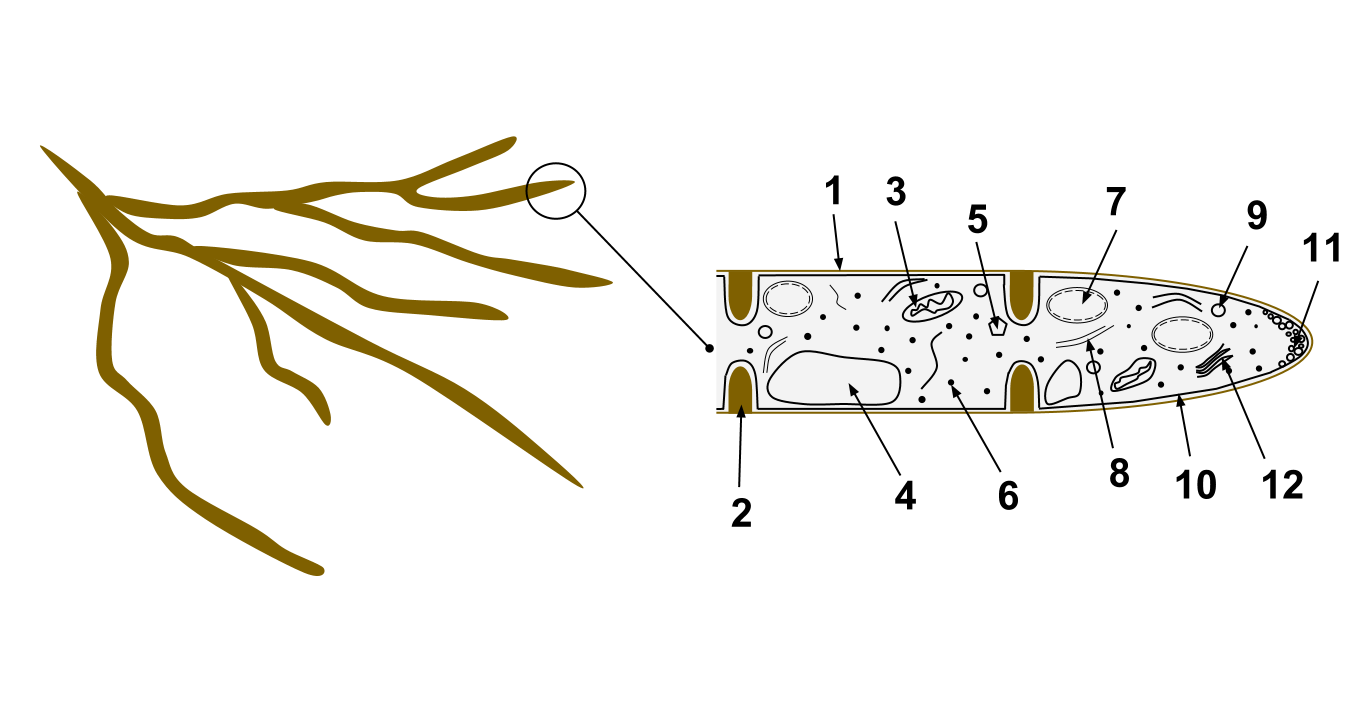

Eukaryote cells include a variety of membrane-bound structures, collectively referred to as the

Eukaryote cells include a variety of membrane-bound structures, collectively referred to as the

Many eukaryotes have long slender motile cytoplasmic projections, called

Many eukaryotes have long slender motile cytoplasmic projections, called

All animals are eukaryotic. Animal cells are distinct from those of other eukaryotes, most notably

All animals are eukaryotic. Animal cells are distinct from those of other eukaryotes, most notably

The cells of

The cells of

In antiquity, the two lineages of

In antiquity, the two lineages of

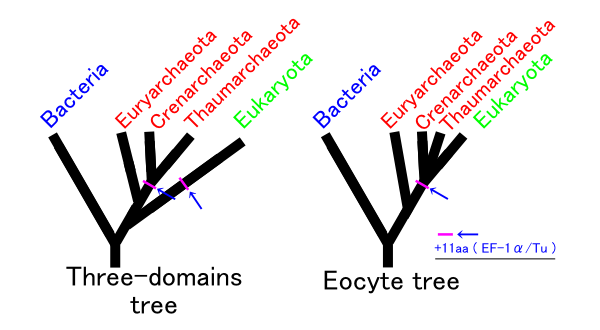

The origin of the eukaryotic cell, also known as eukaryogenesis, is a milestone in the evolution of life, since eukaryotes include all complex cells and almost all multicellular organisms. A number of approaches have been used to find the first eukaryote and their closest relatives. The last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) is the hypothetical

The origin of the eukaryotic cell, also known as eukaryogenesis, is a milestone in the evolution of life, since eukaryotes include all complex cells and almost all multicellular organisms. A number of approaches have been used to find the first eukaryote and their closest relatives. The last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) is the hypothetical

Alternative proposals include:

* The chronocyte hypothesis postulates that a primitive eukaryotic cell was formed by the endosymbiosis of both archaea and bacteria by a third type of cell, termed a chronocyte. This is mainly to account for the fact that eukaryotic signature proteins were not found anywhere else by 2002.

* The universal common ancestor (UCA) of the current tree of life was a complex organism that survived a mass extinction event rather than an early stage in the evolution of life. Eukaryotes and in particular akaryotes (Bacteria and Archaea) evolved through reductive loss, so that similarities result from differential retention of original features.

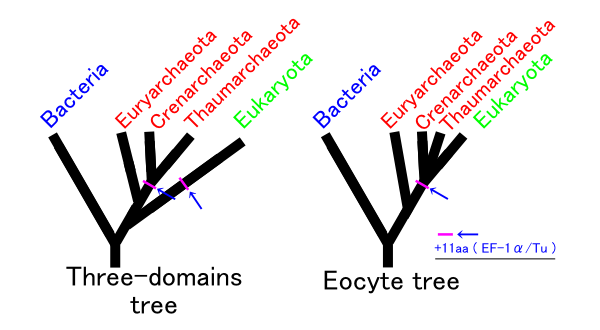

Assuming no other group is involved, there are three possible phylogenies for the Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryota in which each is monophyletic. These are labelled 1 to 3 in the table below, with a modification of hypothesis 2 making the 4th column: The ''eocyte hypothesis'', in which the Archaea are paraphyletic. (The table and the names for the hypotheses are based on Harish & Kurland, 2017.)

In recent years, most researchers have favoured either the three domains (3D) or the

Alternative proposals include:

* The chronocyte hypothesis postulates that a primitive eukaryotic cell was formed by the endosymbiosis of both archaea and bacteria by a third type of cell, termed a chronocyte. This is mainly to account for the fact that eukaryotic signature proteins were not found anywhere else by 2002.

* The universal common ancestor (UCA) of the current tree of life was a complex organism that survived a mass extinction event rather than an early stage in the evolution of life. Eukaryotes and in particular akaryotes (Bacteria and Archaea) evolved through reductive loss, so that similarities result from differential retention of original features.

Assuming no other group is involved, there are three possible phylogenies for the Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryota in which each is monophyletic. These are labelled 1 to 3 in the table below, with a modification of hypothesis 2 making the 4th column: The ''eocyte hypothesis'', in which the Archaea are paraphyletic. (The table and the names for the hypotheses are based on Harish & Kurland, 2017.)

In recent years, most researchers have favoured either the three domains (3D) or the

"Eukaryotes"

(

Attraction and sex among our microbial Last Eukaryotic Common Ancestors

The Atlantic, November 11, 2020 {{Authority control Articles containing video clips

organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

s whose cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

have a nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucle ...

. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

and Archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

(both prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

s) make up the other two domains.

The eukaryotes are usually now regarded as having emerged in the Archaea or as a sister of the Asgard

In Nordic mythology, Asgard (Old Norse: ''Ásgarðr'' ; "enclosure of the Æsir") is a location associated with the gods. It appears in a multitude of Old Norse sagas and mythological texts. It is described as the fortified home of the Æsir ...

archaea. This implies that there are only two domains of life, Bacteria and Archaea, with eukaryotes incorporated among archaea. Eukaryotes represent a small minority of the number of organisms, but, due to their generally much larger size, their collective global biomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms bi ...

is estimated to be about equal to that of prokaryotes. Eukaryotes emerged approximately 2.3–1.8 billion years ago, during the Proterozoic

The Proterozoic () is a geological eon spanning the time interval from 2500 to 538.8million years ago. It is the most recent part of the Precambrian "supereon". It is also the longest eon of the Earth's geologic time scale, and it is subdivided ...

eon, likely as flagellated

A flagellum (; ) is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are termed as flagellates.

A microorganism may have fro ...

phagotroph

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis is ca ...

s. Their name comes from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

εὖ (''eu'', "well" or "good") and κάρυον (''karyon'', "nut" or "kernel").

Eukaryotic cells typically contain other membrane-bound organelles such as mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and Fungus, fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosi ...

and Golgi apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (), also known as the Golgi complex, Golgi body, or simply the Golgi, is an organelle found in most eukaryotic cells. Part of the endomembrane system in the cytoplasm, it packages proteins into membrane-bound vesicles ins ...

. Chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

s can be found in plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

s and algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular mic ...

. Prokaryotic cells may contain primitive organelles. Eukaryotes may be either unicellular

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

or multicellular

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- ...

, and include many cell type

A cell type is a classification used to identify cells that share morphological or phenotypical features. A multicellular organism may contain cells of a number of widely differing and specialized cell types, such as muscle cells and skin cells, ...

s forming different kinds of tissue. In comparison, prokaryotes are typically unicellular. Animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

s, plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

s, and fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

are the most familiar eukaryotes. Other eukaryotes are sometimes called protist

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the exc ...

s.

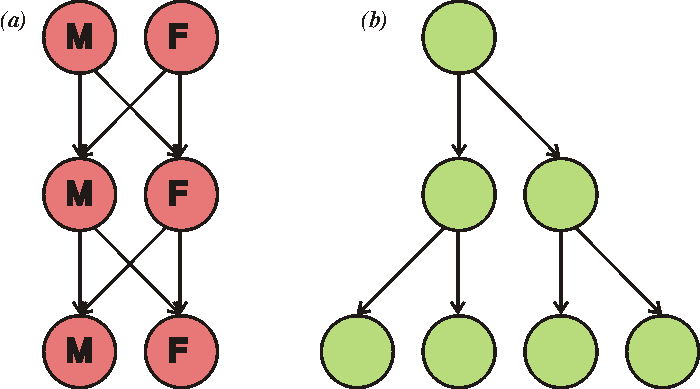

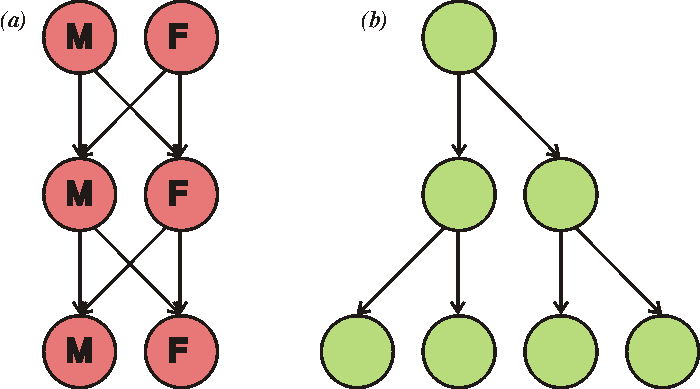

Eukaryotes can reproduce both asexually through mitosis

In cell biology, mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is mainta ...

and sexually through meiosis

Meiosis (; , since it is a reductional division) is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately resu ...

and gamete

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce t ...

fusion. In mitosis, one cell divides to produce two genetically identical cells. In meiosis, DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inheritanc ...

is followed by two rounds of cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell (biology), cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukar ...

to produce four haploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

daughter cells that act as sex cells or gametes. Each gamete has just one set of chromosomes, each a unique mix of the corresponding pair of parental chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

s resulting from genetic recombination

Genetic recombination (also known as genetic reshuffling) is the exchange of genetic material between different organisms which leads to production of offspring with combinations of traits that differ from those found in either parent. In eukaryo ...

during meiosis.

Cell features

Eukaryotic cells

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the ...

are typically much larger than those of prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

s, having a volume of around 10,000 times greater than the prokaryotic cell. They have a variety of internal membrane-bound structures, called organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

s, and a cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compos ...

composed of microtubule

Microtubules are polymers of tubulin that form part of the cytoskeleton and provide structure and shape to eukaryotic cells. Microtubules can be as long as 50 micrometres, as wide as 23 to 27 nm and have an inner diameter between 11 an ...

s, microfilament

Microfilaments, also called actin filaments, are protein filaments in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells that form part of the cytoskeleton. They are primarily composed of polymers of actin, but are modified by and interact with numerous other pr ...

s, and intermediate filament

Intermediate filaments (IFs) are cytoskeletal structural components found in the cells of vertebrates, and many invertebrates. Homologues of the IF protein have been noted in an invertebrate, the cephalochordate ''Branchiostoma''.

Intermedia ...

s, which play an important role in defining the cell's organization and shape. Eukaryotic DNA is divided into several linear bundles called chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

s, which are separated by a microtubular spindle during nuclear division.

Internal membranes

endomembrane system

The endomembrane system is composed of the different membranes (endomembranes) that are suspended in the cytoplasm within a eukaryotic cell. These membranes divide the cell into functional and structural compartments, or organelles. In eukaryotes ...

. Simple compartments, called vesicles

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

; In human embryology

* Vesicle (embryology), bulge-like features o ...

and vacuole

A vacuole () is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in plant and fungal cells and some protist, animal, and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water containing inorganic and organic mo ...

s, can form by budding off other membranes. Many cells ingest food and other materials through a process of endocytosis

Endocytosis is a cellular process in which substances are brought into the cell. The material to be internalized is surrounded by an area of cell membrane, which then buds off inside the cell to form a vesicle containing the ingested material. E ...

, where the outer membrane invaginates and then pinches off to form a vesicle. It is probable that most other membrane-bound organelles are ultimately derived from such vesicles. Alternatively some products produced by the cell can leave in a vesicle through exocytosis

Exocytosis () is a form of active transport and bulk transport in which a cell transports molecules (e.g., neurotransmitters and proteins) out of the cell ('' exo-'' + ''cytosis''). As an active transport mechanism, exocytosis requires the use o ...

.

The nucleus is surrounded by a double membrane known as the nuclear envelope

The nuclear envelope, also known as the nuclear membrane, is made up of two lipid bilayer membranes that in eukaryotic cells surround the nucleus, which encloses the genetic material.

The nuclear envelope consists of two lipid bilayer membrane ...

, with nuclear pore

A nuclear pore is a part of a large complex of proteins, known as a nuclear pore complex that spans the nuclear envelope, which is the double membrane surrounding the eukaryotic cell nucleus. There are approximately 1,000 nuclear pore complexes ...

s that allow material to move in and out. Various tube- and sheet-like extensions of the nuclear membrane form the endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

, which is involved in protein transport and maturation. It includes the rough endoplasmic reticulum where ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

s are attached to synthesize proteins, which enter the interior space or lumen. Subsequently, they generally enter vesicles, which bud off from the smooth endoplasmic reticulum. In most eukaryotes, these protein-carrying vesicles are released and further modified in stacks of flattened vesicles (cisterna

A cisterna (plural cisternae) is a flattened membrane vesicle found in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Cisternae are an integral part of the packaging and modification processes of proteins occurring in the Golgi.

Function

Protein ...

e), the Golgi apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (), also known as the Golgi complex, Golgi body, or simply the Golgi, is an organelle found in most eukaryotic cells. Part of the endomembrane system in the cytoplasm, it packages proteins into membrane-bound vesicles ins ...

.

Vesicles may be specialized for various purposes. For instance, lysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle found in many animal cells. They are spherical vesicles that contain hydrolytic enzymes that can break down many kinds of biomolecules. A lysosome has a specific composition, of both its membrane prot ...

s contain digestive enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s that break down most biomolecule

A biomolecule or biological molecule is a loosely used term for molecules present in organisms that are essential to one or more typically biological processes, such as cell division, morphogenesis, or development. Biomolecules include large ...

s in the cytoplasm. Peroxisome

A peroxisome () is a membrane-bound organelle, a type of microbody, found in the cytoplasm of virtually all eukaryotic cells. Peroxisomes are oxidative organelles. Frequently, molecular oxygen serves as a co-substrate, from which hydrogen pero ...

s are used to break down peroxide

In chemistry, peroxides are a group of compounds with the structure , where R = any element. The group in a peroxide is called the peroxide group or peroxo group. The nomenclature is somewhat variable.

The most common peroxide is hydrogen p ...

, which is otherwise toxic. Many protozoa

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris. Histo ...

ns have contractile vacuoles, which collect and expel excess water, and extrusome Extrusomes are membrane-bound structures in some eukaryotes which, under certain conditions, discharge their contents outside the cell. There are a variety of different types, probably not homologous, and serving various functions.

Notable extru ...

s, which expel material used to deflect predators or capture prey. In higher plants, most of a cell's volume is taken up by a central vacuole, which mostly contains water and primarily maintains its osmotic pressure

Osmotic pressure is the minimum pressure which needs to be applied to a solution to prevent the inward flow of its pure solvent across a semipermeable membrane.

It is also defined as the measure of the tendency of a solution to take in a pure ...

.

Mitochondria

Mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and Fungus, fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosi ...

are organelles found in all but one eukaryote, and are commonly referred to as "the powerhouse of the cell". Mitochondria provide energy to the eukaryote cell by oxidising sugars or fats and releasing energy as ATP. They have two surrounding membranes

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. Bi ...

, each a phospholipid bi-layer; the inner

Interior may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Interior'' (Degas) (also known as ''The Rape''), painting by Edgar Degas

* ''Interior'' (play), 1895 play by Belgian playwright Maurice Maeterlinck

* ''The Interior'' (novel), by Lisa See

* Interior de ...

of which is folded into invaginations called cristae

A crista (; plural cristae) is a fold in the inner membrane of a mitochondrion. The name is from the Latin for ''crest'' or ''plume'', and it gives the inner membrane its characteristic wrinkled shape, providing a large amount of surface area f ...

where aerobic respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be des ...

takes place.

The outer mitochondrial membrane is freely permeable and allows almost anything to enter into the intermembrane space while the inner mitochondrial membrane is semi permeable so allows only some required things into the mitochondrial matrix.

Mitochondria contain their own DNA, which has close structural similarities to bacterial DNA, and which encodes rRNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosoma ...

and tRNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino ac ...

genes that produce RNA which is closer in structure to bacterial RNA than to eukaryote RNA. They are now generally held to have developed from endosymbiotic

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" ...

prokaryotes, probably Alphaproteobacteria

Alphaproteobacteria is a class of bacteria in the phylum Pseudomonadota (formerly Proteobacteria). The Magnetococcales and Mariprofundales are considered basal or sister to the Alphaproteobacteria. The Alphaproteobacteria are highly diverse and p ...

.

Some eukaryotes, such as the metamonad

The metamonads are microscopic eukaryotic organisms, a large group of flagellate amitochondriate Loukozoa. Their composition is not entirely settled, but they include the retortamonads, diplomonads, and possibly the parabasalids and oxymonads a ...

s such as ''Giardia

''Giardia'' ( or ) is a genus of anaerobic flagellated protozoan parasites of the phylum Metamonada that colonise and reproduce in the small intestines of several vertebrates, causing the disease giardiasis. Their life cycle alternates between ...

'' and ''Trichomonas

''Trichomonas'' is a genus of anaerobic excavate parasites of vertebrates. It was first discovered by Alfred François Donné in 1836 when he found these parasites in the pus of a patient suffering from vaginitis, an inflammation of the vagina. ...

'', and the amoebozoan ''Pelomyxa

''Pelomyxa'' is a genus of giant flagellar amoebae, usually 500-800 μm but occasionally up to 5 mm in length, found in anaerobic or microaerobic bottom sediments of stagnant freshwater ponds or slow-moving streams.Chistyakova, L. V., and A. ...

'', appear to lack mitochondria, but all have been found to contain mitochondrion-derived organelles, such as hydrogenosome

A hydrogenosome is a membrane-enclosed organelle found in some anaerobic ciliates, flagellates, and fungi. Hydrogenosomes are highly variable organelles that have presumably evolved from protomitochondria to produce molecular hydrogen and ATP in ...

s and mitosome

A mitosome is an organelle found in some unicellular eukaryotic organisms, like in members of the supergroup Excavata. The mitosome was found and named in 1999, and its function has not yet been well characterized. It was termed a ''crypton'' by ...

s, and thus have lost their mitochondria secondarily. They obtain energy by enzymatic action on nutrients absorbed from the environment. The metamonad ''Monocercomonoides

''Monocercomonoides'' is a genus of flagellate Excavata belonging to the order Oxymonadida. It was established by Bernard V. Travis and was first described as those with "polymastiginid flagellates having three anterior flagella and a trailing o ...

'' has also acquired, by lateral gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring ( reproduction). ...

, a cytosolic sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

mobilisation system which provides the clusters of iron and sulfur required for protein synthesis. The normal mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster pathway has been lost secondarily.

Plastids

Plants and various groups ofalgae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular mic ...

also have plastid

The plastid (Greek: πλαστός; plastós: formed, molded – plural plastids) is a membrane-bound organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of plants, algae, and some other eukaryotic organisms. They are considered to be intracellular endosy ...

s. Plastids also have their own DNA and are developed from endosymbionts

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" ...

, in this case cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, blu ...

. They usually take the form of chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

s which, like cyanobacteria, contain chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to a ...

and produce organic compounds (such as glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using ...

) through photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored i ...

. Others are involved in storing food. Although plastids probably had a single origin, not all plastid-containing groups are closely related. Instead, some eukaryotes have obtained them from others through secondary endosymbiosis

Symbiogenesis (endosymbiotic theory, or serial endosymbiotic theory,) is the leading evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms. The theory holds that mitochondria, plastids such as chloroplasts, and possi ...

or ingestion. The capture and sequestering of photosynthetic cells and chloroplasts occurs in many types of modern eukaryotic organisms and is known as kleptoplasty

Kleptoplasty or kleptoplastidy is a symbiosis, symbiotic phenomenon whereby plastids, notably chloroplasts from algae, are sequestered by host organisms. The word is derived from ''Kleptes'' (κλέπτης) which is Greek language, Greek for thie ...

.

Endosymbiotic origins have also been proposed for the nucleus, and for eukaryotic flagella

A flagellum (; ) is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are termed as flagellates.

A microorganism may have f ...

.

Cytoskeletal structures

Many eukaryotes have long slender motile cytoplasmic projections, called

Many eukaryotes have long slender motile cytoplasmic projections, called flagella

A flagellum (; ) is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are termed as flagellates.

A microorganism may have f ...

, or similar structures called cilia

The cilium, plural cilia (), is a membrane-bound organelle found on most types of eukaryotic cell, and certain microorganisms known as ciliates. Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea. The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike projecti ...

. Flagella and cilia are sometimes referred to as undulipodia

An undulipodium or undulopodium (a Greek word meaning "swinging foot"), or a 9+2 organelle is a motile filamentous extracellular projection of eukaryotic cells. It is basically synonymous to flagella and cilia which are differing terms for simi ...

, and are variously involved in movement, feeding, and sensation. They are composed mainly of tubulin

Tubulin in molecular biology can refer either to the tubulin protein superfamily of globular proteins, or one of the member proteins of that superfamily. α- and β-tubulins polymerize into microtubules, a major component of the eukaryotic cytoske ...

. These are entirely distinct from prokaryotic flagellae. They are supported by a bundle of microtubules arising from a centriole

In cell biology a centriole is a cylindrical organelle composed mainly of a protein called tubulin. Centrioles are found in most eukaryotic cells, but are not present in conifers (Pinophyta), flowering plants (angiosperms) and most fungi, and a ...

, characteristically arranged as nine doublets surrounding two singlets. Flagella also may have hairs, or mastigonemes

Mastigonemes are lateral "hairs" that attach to protistan flagella. Flimsy hairs attach to the flagella of euglenid flagellates, while stiff hairs occur in stramenopile and cryptophyte protists.Hoek, C. van den, Mann, D. G. and Jahns, H. M. (1 ...

, and scales connecting membranes and internal rods. Their interior is continuous with the cell's cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

.

Microfilamental structures composed of actin

Actin is a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells, where it may be present at a concentration of over ...

and actin binding proteins, e.g., α-actinin

Actinin is a microfilament protein. Alpha-actinin-1 is necessary for the attachment of actin myofilaments to the Z-lines in skeletal muscle cells, and to the dense bodies in smooth muscle cells. The functional protein is an anti-parallel dimer, ...

, fimbrin

Fimbrin also known as is plastin 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the PLS1 gene. Fimbrin is an actin cross-linking protein important in the formation of filopodia.

Structure

Fimbrin belongs to the calponin homology (CH) domain supe ...

, filamin Filamins are a class of proteins that hold two actin filaments at large angles. Filamin protein in mammals is made up of an actin-binding domain at its N-terminus that is followed by 24 immunoglobulin-like repeat modules of roughly 95 amino acids. ...

are present in submembranous cortical layers and bundles, as well. Motor protein

Motor proteins are a class of molecular motors that can move along the cytoplasm of cells. They convert chemical energy into mechanical work by the hydrolysis of ATP. Flagellar rotation, however, is powered by a proton pump.

Cellular functions ...

s of microtubules, e.g., dynein

Dyneins are a family of cytoskeletal motor proteins that move along microtubules in cells. They convert the chemical energy stored in ATP to mechanical work. Dynein transports various cellular cargos, provides forces and displacements importa ...

or kinesin

A kinesin is a protein belonging to a class of motor proteins found in eukaryotic cells.

Kinesins move along microtubule (MT) filaments and are powered by the hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (thus kinesins are ATPases, a type of enzy ...

and actin, e.g., myosins

Myosins () are a superfamily of motor proteins best known for their roles in muscle contraction and in a wide range of other motility processes in eukaryotes. They are ATP-dependent and responsible for actin-based motility.

The first myosin (M2 ...

provide dynamic character of the network.

Centrioles

In cell biology a centriole is a cylindrical organelle composed mainly of a protein called tubulin. Centrioles are found in most eukaryotic cells, but are not present in conifers (Pinophyta), flowering plants (angiosperms) and most fungi, and are ...

are often present even in cells and groups that do not have flagella, but conifer

Conifers are a group of conifer cone, cone-bearing Spermatophyte, seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the phylum, division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single ...

s and flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants th ...

s have neither. They generally occur in groups that give rise to various microtubular roots. These form a primary component of the cytoskeletal structure, and are often assembled over the course of several cell divisions, with one flagellum retained from the parent and the other derived from it. Centrioles produce the spindle during nuclear division.

The significance of cytoskeletal structures is underlined in the determination of shape of the cells, as well as their being essential components of migratory responses like chemotaxis

Chemotaxis (from '' chemo-'' + ''taxis'') is the movement of an organism or entity in response to a chemical stimulus. Somatic cells, bacteria, and other single-cell or multicellular organisms direct their movements according to certain chemica ...

and chemokinesis Chemokinesis is chemically prompted kinesis, a motile response of unicellular prokaryotic or eukaryotic organisms to chemicals that cause the cell to make some kind of change in their migratory/swimming behaviour. Changes involve an increase or dec ...

. Some protists

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the excl ...

have various other microtubule-supported organelles. These include the radiolaria

The Radiolaria, also called Radiozoa, are protozoa of diameter 0.1–0.2 mm that produce intricate mineral skeletons, typically with a central capsule dividing the cell (biology), cell into the inner and outer portions of endoplasm and Ecto ...

and heliozoa

Heliozoa, commonly known as sun-animalcules, are microbial eukaryotes (protists) with stiff arms ( axopodia) radiating from their spherical bodies, which are responsible for their common name. The axopodia are microtubule-supported projections fro ...

, which produce axopodia used in flotation or to capture prey, and the haptophyte

The haptophytes, classified either as the Haptophyta, Haptophytina or Prymnesiophyta (named for ''Prymnesium''), are a clade of algae.

The names Haptophyceae or Prymnesiophyceae are sometimes used instead. This ending implies classification at t ...

s, which have a peculiar flagellum-like organelle called the haptonema

The haptophytes, classified either as the Haptophyta, Haptophytina or Prymnesiophyta (named for ''Prymnesium''), are a clade of algae.

The names Haptophyceae or Prymnesiophyceae are sometimes used instead. This ending implies classification at t ...

.

Cell wall

The cells of plants and algae, fungi and most chromalveolates have a cell wall, a layer outside thecell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment ( ...

, providing the cell with structural support, protection, and a filtering mechanism. The cell wall also prevents over-expansion when water enters the cell.

The major polysaccharides

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with w ...

making up the primary cell wall of land plants

The Embryophyta (), or land plants, are the most familiar group of green plants that comprise vegetation on Earth. Embryophytes () have a common ancestor with green algae, having emerged within the Phragmoplastophyta clade of green algae as siste ...

are cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wall ...

, hemicellulose

A hemicellulose (also known as polyose) is one of a number of heteropolymer, heteropolymers (matrix polysaccharides), such as arabinoxylans, present along with cellulose in almost all embryophyte, terrestrial plant cell walls.Scheller HV, Ulvskov H ...

, and pectin

Pectin ( grc, πηκτικός ': "congealed" and "curdled") is a heteropolysaccharide, a structural acid contained in the primary lamella, in the middle lamella, and in the cell walls of terrestrial plants. The principal, chemical component of ...

. The cellulose microfibril A microfibril is a very fine fibril, or fiber-like strand, consisting of glycoproteins and cellulose. It is usually, but not always, used as a general term in describing the structure of protein fiber, e.g. hair and sperm tail. Its most frequently o ...

s are linked via hemicellulosic tethers to form the cellulose-hemicellulose network, which is embedded in the pectin matrix. The most common hemicellulose in the primary cell wall is xyloglucan

Xyloglucan is a hemicellulose that occurs in the primary cell wall of all vascular plants; however, all enzymes responsible for xyloglucan metabolism are found in Charophyceae algae.LEV Del Bem and M Vincentz (2010) Evolution of xyloglucan-related ...

.

Differences among eukaryotic cells

There are many different types of eukaryotic cells, though animals and plants are the most familiar eukaryotes, and thus provide an excellent starting point for understanding eukaryotic structure. Fungi and many protists have some substantial differences, however.Animal cell

plants

Plants are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all curr ...

, as they lack cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mech ...

s and chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

s and have smaller vacuole

A vacuole () is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in plant and fungal cells and some protist, animal, and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water containing inorganic and organic mo ...

s. Due to the lack of a cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mech ...

, animal cells can transform into a variety of shapes. A phagocytic

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis is ...

cell can even engulf other structures.

Plant cell

Plant cell

Plant cells are the cells present in green plants, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Their distinctive features include primary cell walls containing cellulose, hemicelluloses and pectin, the presence of plastids with the capabi ...

s have a number of features that distinguish them from the cells of the other eukaryotic organisms. These include:

* A large central vacuole

A vacuole () is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in plant and fungal cells and some protist, animal, and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water containing inorganic and organic mo ...

(enclosed by a membrane, the tonoplast

A vacuole () is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in plant and fungal cells and some protist, animal, and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water containing inorganic and organic mo ...

), which maintains the cell's turgor

Turgor pressure is the force within the cell that pushes the plasma membrane against the cell wall.

It is also called ''hydrostatic pressure'', and is defined as the pressure in a fluid measured at a certain point within itself when at equilibriu ...

and controls movement of molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioch ...

s between the cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells (intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

and sap

Sap is a fluid transported in xylem cells (vessel elements or tracheids) or phloem sieve tube elements of a plant. These cells transport water and nutrients throughout the plant.

Sap is distinct from latex, resin, or cell sap; it is a separa ...

* A primary cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mech ...

containing cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wall ...

, hemicellulose

A hemicellulose (also known as polyose) is one of a number of heteropolymer, heteropolymers (matrix polysaccharides), such as arabinoxylans, present along with cellulose in almost all embryophyte, terrestrial plant cell walls.Scheller HV, Ulvskov H ...

and pectin

Pectin ( grc, πηκτικός ': "congealed" and "curdled") is a heteropolysaccharide, a structural acid contained in the primary lamella, in the middle lamella, and in the cell walls of terrestrial plants. The principal, chemical component of ...

, deposited by the protoplast

Protoplast (), is a biological term coined by Hanstein in 1880 to refer to the entire cell, excluding the cell wall. Protoplasts can be generated by stripping the cell wall from plant, bacterial, or fungal cells by mechanical, chemical or enzy ...

on the outside of the cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment ( ...

; this contrasts with the cell walls of fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

, which contain chitin

Chitin ( C8 H13 O5 N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is probably the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cellulose); an estimated 1 billion tons of chit ...

, and the cell envelope

The cell envelope comprises the inner cell membrane and the cell wall of a bacterium. In gram-negative bacteria an outer membrane is also included. This envelope is not present in the Mollicutes where the cell wall is absent.

Bacterial cell env ...

s of prokaryotes, in which peptidoglycan

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like peptidoglycan layer outside the plasma membrane, the rigid cell wall (murein sacculus) characteristic of most ...

s are the main structural molecules

* The plasmodesmata

Plasmodesmata (singular: plasmodesma) are microscopic channels which traverse the cell walls of plant cells and some algal cells, enabling transport and communication between them. Plasmodesmata evolved independently in several lineages, and spec ...

, pores in the cell wall that link adjacent cells and allow plant cells to communicate with adjacent cells. Animals have a different but functionally analogous system of gap junction

Gap junctions are specialized intercellular connections between a multitude of animal cell-types. They directly connect the cytoplasm of two cells, which allows various molecules, ions and electrical impulses to directly pass through a regulate ...

s between adjacent cells.

* Plastid

The plastid (Greek: πλαστός; plastós: formed, molded – plural plastids) is a membrane-bound organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of plants, algae, and some other eukaryotic organisms. They are considered to be intracellular endosy ...

s, especially chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

s, organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

s that contain chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to a ...

, the pigment that gives plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

s their green color and allows them to perform photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored i ...

* Bryophyte

The Bryophyta s.l. are a proposed taxonomic division containing three groups of non-vascular land plants (embryophytes): the liverworts, hornworts and mosses. Bryophyta s.s. consists of the mosses only. They are characteristically limited in ...

s and seedless vascular plants only have flagellae and centrioles in the sperm cells. Sperm of cycad

Cycads are seed plants that typically have a stout and woody (ligneous) trunk (botany), trunk with a crown (botany), crown of large, hard, stiff, evergreen and (usually) pinnate leaves. The species are dioecious, that is, individual plants o ...

s and ''Ginkgo

''Ginkgo'' is a genus of non-flowering seed plants. The scientific name is also used as the English name. The order to which it belongs, Ginkgoales, first appeared in the Permian, 270 million years ago, and is now the only living genus within ...

'' are large, complex cells that swim with hundreds to thousands of flagellae.

* Conifers

Conifers are a group of cone-bearing seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single extant class, Pinopsida. All extan ...

(Pinophyta) and flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants th ...

s (Angiospermae) lack the flagellae and centriole

In cell biology a centriole is a cylindrical organelle composed mainly of a protein called tubulin. Centrioles are found in most eukaryotic cells, but are not present in conifers (Pinophyta), flowering plants (angiosperms) and most fungi, and a ...

s that are present in animal cells.

Fungal cell

The cells of

The cells of fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

are similar to animal cells, with the following exceptions:

* A cell wall that contains chitin

Chitin ( C8 H13 O5 N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is probably the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cellulose); an estimated 1 billion tons of chit ...

* Less compartmentation between cells; the hypha

A hypha (; ) is a long, branching, filamentous structure of a fungus, oomycete, or actinobacterium. In most fungi, hyphae are the main mode of vegetative growth, and are collectively called a mycelium.

Structure

A hypha consists of one or ...

e of higher fungi have porous partitions called septa

The Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) is a regional public transportation authority that operates bus, rapid transit, commuter rail, light rail, and electric trolleybus services for nearly 4 million people in five coun ...

, which allow the passage of cytoplasm, organelles, and, sometimes, nuclei; so each organism is essentially a giant multinucleate

Multinucleate cells (also known as multinucleated or polynuclear cells) are eukaryotic cells that have more than one nucleus per cell, i.e., multiple nuclei share one common cytoplasm. Mitosis in multinucleate cells can occur either in a coordinat ...

supercell – these fungi are described as coenocytic

A coenocyte () is a multinucleate cell which can result from multiple nuclear divisions without their accompanying cytokinesis, in contrast to a syncytium, which results from cellular aggregation followed by dissolution of the cell membranes insid ...

. Primitive fungi have few or no septa.

* Only the most primitive fungi, chytrid

Chytridiomycota are a division of zoosporic organisms in the kingdom Fungi, informally known as chytrids. The name is derived from the Ancient Greek ('), meaning "little pot", describing the structure containing unreleased zoöspores. Chytrid ...

s, have flagella.

Other eukaryotic cells

Some groups of eukaryotes have unique organelles, such as the cyanelles (unusual plastids) of theglaucophyte

The glaucophytes, also known as glaucocystophytes or glaucocystids, are a small group of unicellular algae found in freshwater and moist terrestrial environments, less common today than they were during the Proterozoic. The stated number of spe ...

s, the haptonema of the haptophyte

The haptophytes, classified either as the Haptophyta, Haptophytina or Prymnesiophyta (named for ''Prymnesium''), are a clade of algae.

The names Haptophyceae or Prymnesiophyceae are sometimes used instead. This ending implies classification at t ...

s, or the ejectosome An ejectosome is a cellular organelle responsible for ejecting their contents from the cell. Two unrelated types of ejectosomes are described in the literature:

# Cryptomonads have two types of characteristic ejectosomes known as extrusomes.

# Intr ...

s of the cryptomonad

The cryptomonads (or cryptophytes) are a group of algae, most of which have plastids. They are common in freshwater, and also occur in marine and brackish habitats. Each cell is around 10–50 μm in size and flattened in shape, with an anterio ...

s. Other structures, such as pseudopodia

A pseudopod or pseudopodium (plural: pseudopods or pseudopodia) is a temporary arm-like projection of a eukaryotic cell membrane that is emerged in the direction of movement. Filled with cytoplasm, pseudopodia primarily consist of actin filament ...

, are found in various eukaryote groups in different forms, such as the lobose amoebozoa

Amoebozoa is a major taxonomic group containing about 2,400 described species of amoeboid protists, often possessing blunt, fingerlike, lobose pseudopods and tubular mitochondrial cristae. In traditional and currently no longer supported classi ...

ns or the reticulose foraminiferan

Foraminifera (; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly an ...

s. Structures known as cortical alveoli The cortical alveoli (singular: cortical alveolum) are cellular organelles composed of vesicles located under the cytoplasmic membrane, to which they give support. They have been defined as membrane sacs that strengthen the cellular cortex through t ...

are vesicles present under the cell membrane of many protist

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the exc ...

s such as dinoflagellate

The dinoflagellates (Greek δῖνος ''dinos'' "whirling" and Latin ''flagellum'' "whip, scourge") are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered algae. Dinoflagellates are ...

s, ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to flagellum, eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a ...

s and apicomplexan parasites.

Reproduction

Cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell (biology), cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukar ...

generally takes place asexually by mitosis

In cell biology, mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is mainta ...

, a process that allows each daughter nucleus to receive one copy of each chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

. Most eukaryotes also have a life cycle that involves sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote tha ...

, alternating between a haploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

phase, where only one copy of each chromosome is present in each cell and a diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

phase, wherein two copies of each chromosome are present in each cell. The diploid phase is formed by fusion of two haploid gametes to form a zygote, which may divide by mitosis or undergo chromosome reduction by meiosis

Meiosis (; , since it is a reductional division) is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately resu ...

. There is considerable variation in this pattern. Animals have no multicellular haploid phase, but each plant generation can consist of haploid and diploid multicellular phases.

Eukaryotes have a smaller surface area to volume ratio than prokaryotes, and thus have lower metabolic rates and longer generation times.

The evolution of sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is an adaptive feature which is common to almost all multicellular organisms and various unicellular organisms, with some organisms being incapable of asexual reproduction. Currently the adaptive advantage of sexual reprodu ...

may be a primordial and fundamental characteristic of eukaryotes. Based on a phylogenetic analysis, Dacks and Roger

Roger is a given name, usually masculine, and a surname. The given name is derived from the Old French personal names ' and '. These names are of Germanic origin, derived from the elements ', ''χrōþi'' ("fame", "renown", "honour") and ', ' ( ...

proposed that facultative sex was present in the common ancestor of all eukaryotes. A core set of genes that function in meiosis is present in both ''Trichomonas vaginalis

''Trichomonas vaginalis'' is an anaerobic, flagellated protozoan parasite and the causative agent of a sexually transmitted disease called trichomoniasis. It is the most common pathogenic protozoan that infects humans in industrialized countries ...

'' and ''Giardia intestinalis

''Giardia duodenalis'', also known as ''Giardia intestinalis'' and ''Giardia lamblia'', is a flagellated parasitic microorganism of the genus ''Giardia'' that colonizes the small intestine, causing a diarrheal condition known as giardiasis. The ...

'', two organisms previously thought to be asexual. Since these two species are descendants of lineages that diverged early from the eukaryotic evolutionary tree, it was inferred that core meiotic genes, and hence sex, were likely present in a common ancestor of all eukaryotes. Eukaryotic species once thought to be asexual, such as parasitic protozoa of the genus ''Leishmania

''Leishmania'' is a parasitic protozoan, a single-celled organism of the genus '' Leishmania'' that are responsible for the disease leishmaniasis. They are spread by sandflies of the genus ''Phlebotomus'' in the Old World, and of the genus '' ...

'', have been shown to have a sexual cycle. Also, evidence now indicates that amoebae, previously regarded as asexual, are anciently sexual and that the majority of present-day asexual groups likely arose recently and independently.

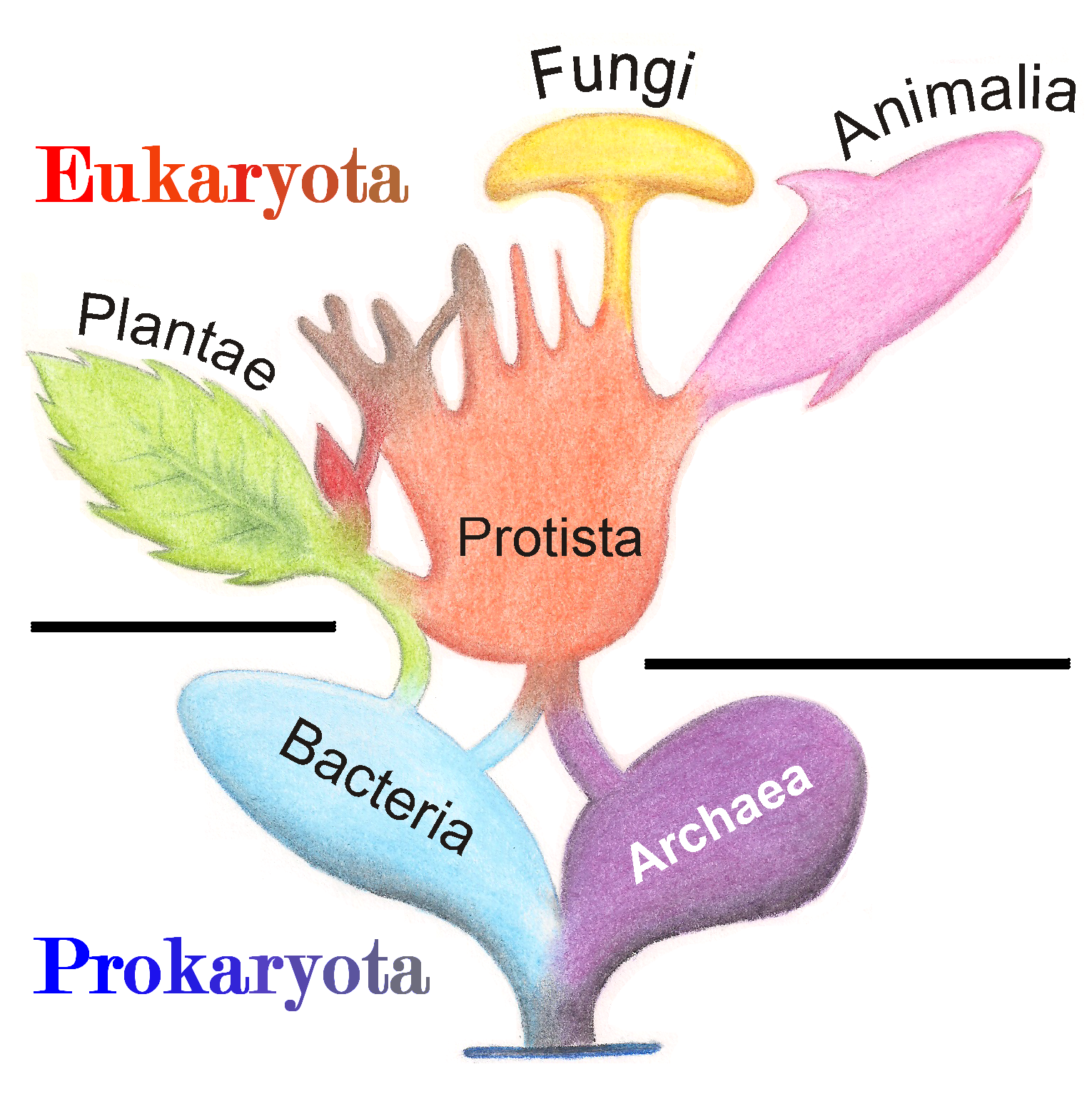

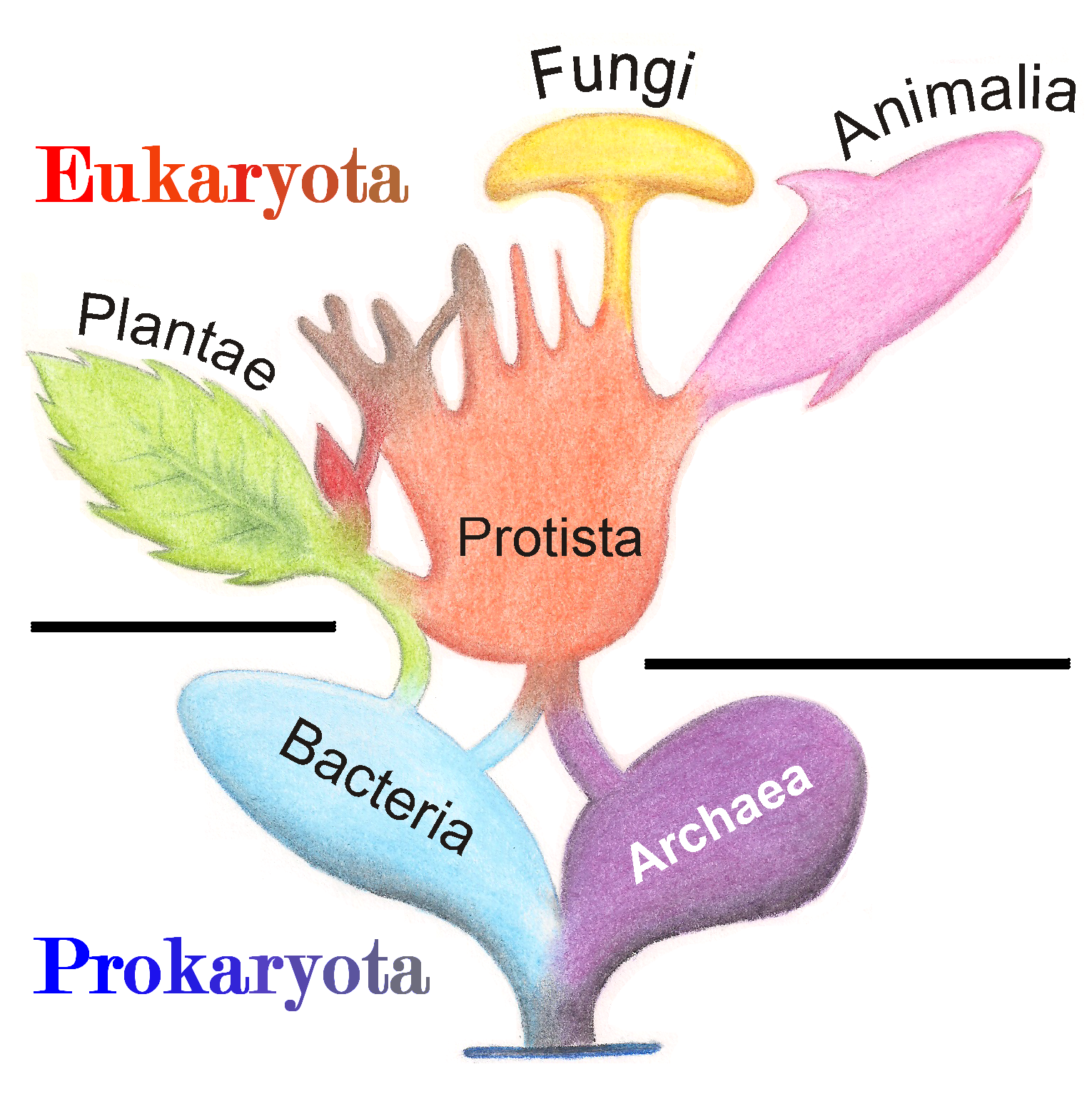

Classification

In antiquity, the two lineages of

In antiquity, the two lineages of animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

s and plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

s were recognized. They were given the taxonomic rank

In biological classification, taxonomic rank is the relative level of a group of organisms (a taxon) in an ancestral or hereditary hierarchy. A common system consists of species, genus, family (biology), family, order (biology), order, class (b ...

of Kingdom

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

by Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

. Though he included the fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

with plants with some reservations, it was later realized that they are quite distinct and warrant a separate kingdom, the composition of which was not entirely clear until the 1980s. The various single-cell eukaryotes were originally placed with plants or animals when they became known. In 1818, the German biologist Georg A. Goldfuss

Georg August Goldfuss (Goldfuß, 18 April 1782 – 2 October 1848) was a German palaeontologist, zoologist and botanist.

Goldfuss was born at Thurnau near Bayreuth. He was educated at Erlangen, where he graduated PhD in 1804 and became pr ...

coined the word ''protozoa

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris. Histo ...

'' to refer to organisms such as ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to flagellum, eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a ...

s, and this group was expanded until it encompassed all single-celled eukaryotes, and given their own kingdom, the Protista

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the excl ...

, by Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new sp ...

in 1866. The eukaryotes thus came to be composed of four kingdoms:

* Kingdom Protista

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the excl ...

* Kingdom Plantae

Plants are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all curr ...

* Kingdom Fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

* Kingdom Animalia

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and go through an ontogenetic stage in ...

The protists were understood to be "primitive forms", and thus an evolutionary grade

A grade is a taxon united by a level of morphological or physiological complexity. The term was coined by British biologist Julian Huxley, to contrast with clade, a strictly phylogenetic unit.

Definition

An evolutionary grade is a group of ...

, united by their primitive unicellular nature. The disentanglement of the deep splits in the tree of life

The tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world's mythological, religious, and philosophical traditions. It is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree.Giovino, Mariana (2007). ''The Assyrian Sacred Tree: A History ...

only really started with DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

, leading to a system of domains rather than kingdoms as top level rank being put forward by Carl Woese

Carl Richard Woese (; July 15, 1928 – December 30, 2012) was an American microbiologist and biophysicist. Woese is famous for defining the Archaea (a new domain of life) in 1977 through a pioneering phylogenetic taxonomy of 16S ribosomal RNA, ...

, uniting all the eukaryote kingdoms under the eukaryote domain. At the same time, work on the protist tree intensified, and is still actively going on today. Several alternative classifications have been forwarded, though there is no consensus in the field.

Eukaryotes are a clade usually assessed to be sister to Heimdallarchaeota

Asgard or Asgardarchaeota is a proposed superphylum consisting of a group of archaea that includes Lokiarchaeota, Thorarchaeota, Odinarchaeota, and Heimdallarchaeota. It appears the eukaryotes emerged within the Asgard, in a branch containing th ...

in the Asgard

In Nordic mythology, Asgard (Old Norse: ''Ásgarðr'' ; "enclosure of the Æsir") is a location associated with the gods. It appears in a multitude of Old Norse sagas and mythological texts. It is described as the fortified home of the Æsir ...

grouping in the Archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

. In one proposed system, the basal groupings are the Opimoda

The Scotokaryotes (Cavalier-Smith) is a proposed basal Neokaryote clade as sister of the Diaphoretickes. Basal Scotokaryote groupings are the Metamonads, the Malawimonas and the Podiata. In this phylogeny the Discoba are sometimes seen as paraph ...

, Diphoda

A bikont ("two flagella") is any of the eukaryotic organisms classified in the group Bikonta. Many single-celled members of the group, and the presumed ancestor, have two flagella.

Enzymes

Another shared trait of bikonts is the fusion of two ge ...

, the Discoba

Excavata is a major supergroup of unicellular organisms belonging to the domain Eukaryota. It was first suggested by Simpson and Patterson in 1999 and introduced by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 2002 as a formal taxon. It contains a variety of fre ...

, and the Loukozoa

Loukozoa (+ Ancyromonads) (From Greek ''loukos'': groove) is a proposed taxon used in some classifications of eukaryotes, consisting of the Metamonada and Malawimonadea. Ancyromonads are closely related to this group, as sister of the entire grou ...

. The Eukaryote root is usually assessed to be near or even in Discoba.

A classification produced in 2005 for the International Society of Protistologists, which reflected the consensus of the time, divided the eukaryotes into six supposedly monophyletic ' supergroups'. However, in the same year (2005), doubts were expressed as to whether some of these supergroups were monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic gro ...

, particularly the Chromalveolata

Chromalveolata was a eukaryote supergroup present in a major classification of 2005, then regarded as one of the six major groups within the eukaryotes.

It was a refinement of the kingdom Chromista, first proposed by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 1 ...

, and a review in 2006 noted the lack of evidence for several of the supposed six supergroups. A revised classification in 2012 recognizes five supergroups.

There are also smaller groups of eukaryotes whose position is uncertain or seems to fall outside the major groups – in particular, Haptophyta

The haptophytes, classified either as the Haptophyta, Haptophytina or Prymnesiophyta (named for ''Prymnesium''), are a clade of algae.

The names Haptophyceae or Prymnesiophyceae are sometimes used instead. This ending implies classification at t ...

, Cryptophyta

The cryptophyceae are a class of algae, most of which have plastids. About 220 species are known, and they are common in freshwater, and also occur in marine and brackish habitats. Each cell is around 10–50 μm in size and flattened in shape, ...

, Centrohelida

The centrohelids or centroheliozoa are a large group of heliozoan protists. They include both mobile and sessile forms, found in freshwater and marine environments, especially at some depth.

Characteristics

Individuals are unicellular and spher ...

, Telonemia

Telonemia is a phylum of microscopic eukaryote, single-celled organisms. They were formerly classified as protists until that kingdom fell out of general use, and are suggested to have evolutionary significance in being a possible transitional fo ...

, Picozoa

Picozoa, Picobiliphyta, Picobiliphytes, or Biliphytes are protists of a phylum of marine unicellular heterotrophic eukaryotes with a size of less than about 3 micrometers. They were formerly treated as eukaryotic algae and the smallest member of ...

, Apusomonadida

The Apusomonadida are a group of protozoan zooflagellates that glide on surfaces, and mostly consume prokaryotes. They are of particular evolutionary interest because they appear to be the sister group to the Opisthokonts, the clade that includ ...

, Ancyromonadida

Ancyromonadida or Planomonadida is a small group of biflagellated protists found in the soil and in aquatic habitats, where they feed on bacteria.Cavalier-Smith, T. (2013)Early evolution of eukaryote feeding modes, cell structural diversity, and ...

, Breviatea

''Breviata anathema'' is a single-celled flagellate amoeboid eukaryote, previously studied under the name ''Mastigamoeba invertens''. The cell lacks mitochondria but has remnant mitochondrial genes, and possesses an organelle believed to be a m ...

, and the genus ''Collodictyon

''Collodictyon'' is a genus of single-celled, omnivorous eukaryotes belonging to the collodictyonids, also known as diphylleids. Due to their mix of cellular components, Collodictyonids do not belong to any well-known kingdom (biology), kingdom-l ...

''. Overall, it seems that, although progress has been made, there are still very significant uncertainties in the evolutionary history and classification of eukaryotes. As Roger