Noise in music on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

Many

Many

And now I hear the turban-wearing women,

Votaries of th' Asiatic Cybele,

The wealthy Phrygians' daughters, loudly sounding

With drums, and rhombs, and brazen-clashing cymbals,

Their hands in concert striking on each other,

Pour forth a wise and healing hymn to the gods.

An altogether darker picture of the function of this noise music is painted by

South Asian music places a special emphasis on drumming, which is freed from the primary time-keeping function of drumming found in other part of the world. In North India, secular processional bands play an important role in civic festival parades and the ''bārāt'' processions leading a groom's wedding party to the bride's home or the hall where a wedding is held. These bands vary in makeup, depending on the means of the families employing them and according to changing fashions over time, but the core instrumentation is a small group of percussionists, usually playing a frame drum (''ḍaphalā''), a gong, and a pair of kettledrums (''nagāṛā''). Better-off families will add shawms (

South Asian music places a special emphasis on drumming, which is freed from the primary time-keeping function of drumming found in other part of the world. In North India, secular processional bands play an important role in civic festival parades and the ''bārāt'' processions leading a groom's wedding party to the bride's home or the hall where a wedding is held. These bands vary in makeup, depending on the means of the families employing them and according to changing fashions over time, but the core instrumentation is a small group of percussionists, usually playing a frame drum (''ḍaphalā''), a gong, and a pair of kettledrums (''nagāṛā''). Better-off families will add shawms (

The Turkish

The Turkish

At about the same time that "Turkish music" was coming into vogue in Europe, a fashion for programmatic keyboard music opened the way for the introduction of another kind of noise in the form of the keyboard

At about the same time that "Turkish music" was coming into vogue in Europe, a fashion for programmatic keyboard music opened the way for the introduction of another kind of noise in the form of the keyboard

Percussive effects in imitation of drumming had been introduced to bowed-string instruments by early in the 17th century. The earliest known use of ''

Percussive effects in imitation of drumming had been introduced to bowed-string instruments by early in the 17th century. The earliest known use of ''

In the 1920s a fashion emerged for composing what was called "machine music"—the depiction in music of the sounds of factories, locomotives, steamships, dynamos, and other aspects of recent technology that both reflected modern, urban life and appealed to the then-prevalent spirit of objectivity, detachment, and directness. Representative works in this style, which features motoric and insistent rhythms, a high level of dissonance, and often large percussion batteries, are

In the 1920s a fashion emerged for composing what was called "machine music"—the depiction in music of the sounds of factories, locomotives, steamships, dynamos, and other aspects of recent technology that both reflected modern, urban life and appealed to the then-prevalent spirit of objectivity, detachment, and directness. Representative works in this style, which features motoric and insistent rhythms, a high level of dissonance, and often large percussion batteries, are

Use of noise was central to the development of

Use of noise was central to the development of

Noise is used as basic tonal material in

Noise is used as basic tonal material in

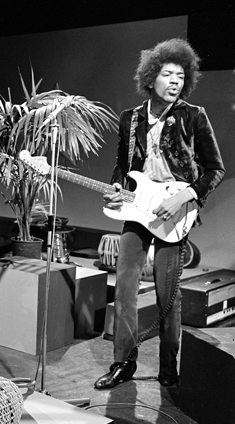

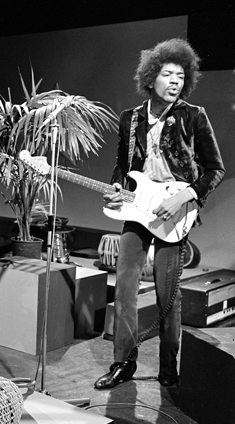

While the electric guitar was originally designed to be simply amplified in order to reproduce its sound at a higher volume, guitarists quickly discovered the creative possibilities of using the amplifier to modify the sound, particularly by extreme settings of tone and volume controls.Bacon 1981, 119

Distortion was at first produced by simply overloading the amplifier to induce

While the electric guitar was originally designed to be simply amplified in order to reproduce its sound at a higher volume, guitarists quickly discovered the creative possibilities of using the amplifier to modify the sound, particularly by extreme settings of tone and volume controls.Bacon 1981, 119

Distortion was at first produced by simply overloading the amplifier to induce

Since its origins in

Since its origins in

Noise music (also referred to simply as noise) has been represented by many genres during the 20th century and subsequently. Some of its proponents reject the attempt to classify it as a single overall

Noise music (also referred to simply as noise) has been represented by many genres during the 20th century and subsequently. Some of its proponents reject the attempt to classify it as a single overall

Most often, musicians are concerned not to produce noise, but to minimise it.

Most often, musicians are concerned not to produce noise, but to minimise it.

The World of Physics

' Cheltenham:

Live Report: Krakow's Unsound Festival

. ''

Guitar Facts

'. Milwaukee:

100 Entertainers Who Changed America: An Encyclopedia of Pop Culture Luminaries [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Pop Culture Luminaries

', edited by Robert C. Sickels. 115-121. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. . *Bush, André. 2005.

Modern Jazz Guitar Styles

'. Pacific:

American Music: A Panorama

'. Stamford:

To the Break of Dawn: A Freestyle on the Hip Hop Aesthetic

'. New York: New York University Press. . *Coelho, Victor (ed.). 2003.

The Cambridge Companion to the Guitar

'. Cambridge:

Motorhead is the Loudest Band on Earth

. '' Spin'' 1, no. 10 (February): 36. (Accessed 21 April 2012) . *Connolly, Kate. 2008.

New Work Too Loud for Orchestra

. ''

Gallows Become the World's Loudest Band!

, ''

the original

on 26 June 2007. *De la Parra, Fito, with T. W. McGarry, and Marlane McGarry. 2000.

Living the Blues: Canned Heat's Story of Music, Drugs, Death, Sex and Survival

'. .l. RUF; London: Turnaround; Nipomo, Calif: Canned Heat Music. . eBookIt.com (9 June 2011). . * Dicaire, David. 2006.'' Jazz Musicians, 1945 to the Present''. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. . *

Dealing with a Noise Nuisance

.

Dolby B, C, and S Noise Reduction Systems: Making Cassettes Sound Better

. *Dunscomb, J. Richard, and Willie L. Hill. 2002.

Jazz Pedagogy: The Jazz Educator's Handbook and Resource Guide

'. Los Angeles:

Reflecting Black: African-American Cultural Criticism

'. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. . *Economy, Jeff. 2004.

Proud Sunn O))) Fills the Air

, ''

Employment for Individuals with Asperger Syndrome or Non-Verbal Learning Disability: Stories and Strategies

'. London:

Japanese Cybercultures

'. London and New York:

Exploring the World of Music: An Introduction to Music from a World Music Perspective

'. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt. (Accessed 19 April 2012). * Hegarty, Paul. 2008.

Come on, feel the noise

. ''

Too Loud, Too Bright, Too Fast, Too Tight: What to Do If You Are Sensory Defensive in an Overstimulating World

'. New York:

Planning and Designing Research Animal Facilities

'. Amsterdam, London, Boston: Elsevier/

Electronic and Experimental Music: Technology, Music, and Culture

', third edition. New York:

Musical Instrument Design: Practical Information for Instrument Making

'. Tucson:

My Bloody Valentine Will Hand Out Free Earplugs Tonight: Use Them

, ''

An American Band: The Story of Grand Funk Railroad

'. London: SAF Publishing. . *Jansson, E., and K. Karlsson. 1983.

Sound Levels Recorded Within the Symphony Orchestra and Risk Criteria for Hearing Loss

. ''Scandinavian Audiology'' 12, no. 3 (1 January): 215–221. (Accessed 19 April 2012). *Jones, Stephen. 2001. "China: §IV: Living Traditions, 4: Instrumental Music, (i) Ensemble Traditions, (b) Shawm-and-Percussion Bands". ''

Groove Music: The Art and Culture of the Hip-Hop DJ

'. New York: Oxford University Press. . * Kennedy, Michael. 2006. "Sprechgesang, Sprechstimme". ''The Oxford Dictionary of Music'', second edition, revised, Joyce Bourne, associate editor. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. . *Kimbell, David. 1991. ''Italian Opera''. Cambridge, New York, and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. . *Kirchner, Bill (ed.). 2005.

The Oxford Companion To Jazz

'. New York:

Adaptive Stochastic Resonance

'' Proceedings of the IEEE'' 86, no. 11 (November): 2152-2183. *Kosko, Bart. 2006.

Noise

'.

In

In music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

, noise is variously described as unpitched

An unpitched percussion instrument is a percussion instrument played in such a way as to produce sounds of indeterminate pitch, or an instrument normally played in this fashion.

Unpitched percussion is typically used to maintain a rhythm or to ...

, indeterminate, uncontrolled, loud, unmusical, or unwanted sound. Noise is an important component of the sound of the human voice

The human voice consists of sound made by a human being using the vocal tract, including talking, singing, laughing, crying, screaming, shouting, humming or yelling. The human voice frequency is specifically a part of human sound production ...

and all musical instrument

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who pl ...

s, particularly in unpitched percussion instrument

An unpitched percussion instrument is a percussion instrument played in such a way as to produce sounds of indeterminate pitch, or an instrument normally played in this fashion.

Unpitched percussion is typically used to maintain a rhythm or to ...

s and electric guitars (using distortion

In signal processing, distortion is the alteration of the original shape (or other characteristic) of a signal. In communications and electronics it means the alteration of the waveform of an information-bearing signal, such as an audio signal ...

). Electronic instruments

An electronic musical instrument or electrophone is a musical instrument that produces sound using electronic circuitry. Such an instrument sounds by outputting an electrical, electronic or digital audio signal that ultimately is plugged into a ...

create various colours of noise. Traditional uses of noise are unrestricted, using all the frequencies associated with pitch and timbre

In music, timbre ( ), also known as tone color or tone quality (from psychoacoustics), is the perceived sound quality of a musical note, sound or musical tone, tone. Timbre distinguishes different types of sound production, such as choir voice ...

, such as the white noise

In signal processing, white noise is a random signal having equal intensity at different frequencies, giving it a constant power spectral density. The term is used, with this or similar meanings, in many scientific and technical disciplines, ...

component of a drum roll

A drum roll (or roll for short) is a technique used by percussionists to produce a sustained sound for the duration of a written note.Cirone, Anthony J. (1991). Simple Steps to Snare Drum', p.30-31. Alfred. . "The purpose of the roll is t ...

on a snare drum

The snare (or side drum) is a percussion instrument that produces a sharp staccato sound when the head is struck with a drum stick, due to the use of a series of stiff wires held under tension against the lower skin. Snare drums are often used ...

, or the transients present in the prefix

A prefix is an affix which is placed before the Word stem, stem of a word. Adding it to the beginning of one word changes it into another word. For example, when the prefix ''un-'' is added to the word ''happy'', it creates the word ''unhappy'' ...

of the sounds of some organ pipe

An organ pipe is a sound-producing element of the pipe organ that resonates at a specific pitch when pressurized air (commonly referred to as ''wind'') is driven through it. Each pipe is tuned to a specific note of the musical scale. A set of ...

s.

The influence of modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

in the early 20th century lead composers such as Edgard Varèse

Edgard Victor Achille Charles Varèse (; also spelled Edgar; December 22, 1883 – November 6, 1965) was a French-born composer who spent the greater part of his career in the United States. Varèse's music emphasizes timbre and rhythm; he coined ...

to explore the use of noise-based sonorities in an orchestral setting. In the same period the Italian Futurist

Futurists (also known as futurologists, prospectivists, foresight practitioners and horizon scanners) are people whose specialty or interest is futurology or the attempt to systematically explore predictions and possibilities abou ...

Luigi Russolo

Luigi Carlo Filippo Russolo (30 April 1885 – 4 February 1947) was an Italian Futurist painter, composer, builder of experimental musical instruments, and the author of the manifesto ''The Art of Noises'' (1913). He is often regarded as one of ...

created a "noise orchestra" using instruments he called intonarumori

Intonarumori are experimental musical instruments invented and built by the Italian futurist Luigi Russolo between roughly 1910 and 1930. There were 27 varieties of intonarumori built in total, with different names.

Background

Russolo built ...

. Later in the 20th century the term noise music

Noise music is a genre of music that is characterised by the expressive use of noise within a musical context. This type of music tends to challenge the distinction that is made in conventional musical practices between musical and non-musical ...

came to refer to works consisting primarily of noise-based sound.

In more general usage, noise

Noise is unwanted sound considered unpleasant, loud or disruptive to hearing. From a physics standpoint, there is no distinction between noise and desired sound, as both are vibrations through a medium, such as air or water. The difference arise ...

is any unwanted sound

In physics, sound is a vibration that propagates as an acoustic wave, through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid.

In human physiology and psychology, sound is the ''reception'' of such waves and their ''perception'' by the ...

or signal

In signal processing, a signal is a function that conveys information about a phenomenon. Any quantity that can vary over space or time can be used as a signal to share messages between observers. The '' IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing' ...

. In this sense, even sounds that would be perceived as musically ordinary in another context become noise if they interfere with the reception of a message desired by the receiver. Prevention and reduction of unwanted sound, from tape hiss

Tape or Tapes may refer to:

Material

A long, narrow, thin strip of material (see also Ribbon (disambiguation):

Adhesive tapes

* Adhesive tape, any of many varieties of backing materials coated with an adhesive

*Athletic tape, pressure-sensitiv ...

to squeaking bass drum pedal

The bass drum is a large drum that produces a note of low definite or indefinite pitch. The instrument is typically cylindrical, with the drum's diameter much greater than the drum's depth, with a struck head at both ends of the cylinder. Th ...

s, is important in many musical pursuits, but noise is also used creatively in many ways, and in some way in nearly all genre

Genre () is any form or type of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially-agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other for ...

s.

Definition of noise

In conventional musical practices sounds that are considered ''unmusical'' tend to be treated as noise. ''Oscillations and Waves'' defines noise as irregular vibrations of an object, in contrast to the periodical, patterned structure of music. More broadly, electrical engineering professorBart Kosko

Bart Andrew Kosko (born February 7, 1960) is a writer and professor of electrical engineering and law at the University of Southern California (USC). He is a researcher and popularizer of fuzzy logic, neural networks, and noise, and author of sev ...

in the introductory chapter of his book ''Noise'' defines noise as a "signal we don't like." Paul Hegarty

Paul Anthony Hegarty (born 25 July 1954 in Edinburgh) is a Scottish football player and manager. He was captain of Dundee United during their most successful era in the 1970s and 1980s, winning the Scottish league championship in 1983 and th ...

, a lecturer and noise musician, likewise assigns a subjective value to noise, writing that "noise is a judgment, a social one, based on unacceptability, the breaking of norms and a fear of violence." Composer and music educator R. Murray Schafer

Raymond Murray Schafer (18 July 1933 – 14 August 2021) was a Canadian composer, writer, music educator, and environmentalist perhaps best known for his World Soundscape Project, concern for acoustic ecology, and his book ''The Tuning of th ...

divided noise into four categories: Unwanted noise, unmusical sound, any loud system, and a disturbance in any signaling system.

In regard to what is noise as opposed to music, Robert Fink in ''The Origin of Music: A Theory of the Universal Development of Music'' claims that while cultural theories view the difference between noise and music as purely the result of social forces, habit, and custom, "everywhere in history we see man making some selections of some sounds as noise, certain other sounds as music, and in the ''overall development'' of all cultures, this distinction is made around the ''same'' sounds." However, musicologist Jean-Jacques Nattiez

Jean-Jacques Nattiez (; born December 30, 1945 in Amiens, France) is a musical semiologist or semiotics, semiotician and professor of musicology at the Université de Montréal. He studied semiology with Georges Mounin and Jean Molino and music ...

considers the difference between noise and music nebulous, explaining that "The border between music and noise is always culturally defined—which implies that, even within a single society, this border does not always pass through the same place; in short, there is rarely a consensus ... By all accounts there is no ''single'' and ''intercultural'' universal concept defining what music might be."

Noise as a feature of music

Musical tones produced by the human voice and all acoustical musical instruments incorporate noises in varying degrees. Most consonants in human speech (e.g., the sounds of ''f'', ''v'', ''s'', ''z'', both voiced and unvoiced ''th'', Scottish and German ''ch'') are characterised by distinctive noises, and even vowels are not entirely noise free. Wind instruments include the whizzing or hissing sounds of air breaking against the edges of the mouthpiece, while bowed instruments produce audible rubbing noises that contribute, when the instrument is poor or the player unskilful, to what is perceived as a poor tone. When they are not excessive, listeners "make themselves deaf" to these noises by ignoring them.Unpitched percussion

unpitched percussion instrument

An unpitched percussion instrument is a percussion instrument played in such a way as to produce sounds of indeterminate pitch, or an instrument normally played in this fashion.

Unpitched percussion is typically used to maintain a rhythm or to ...

s, such as the snare drum

The snare (or side drum) is a percussion instrument that produces a sharp staccato sound when the head is struck with a drum stick, due to the use of a series of stiff wires held under tension against the lower skin. Snare drums are often used ...

or maraca

A maraca (), sometimes called shaker or chac-chac, is a rattle which appears in many genres of Caribbean and Latin music. It is shaken by a handle and usually played as part of a pair.

Maracas (from Guaraní ), also known as tamaracas, were r ...

s, make use of the presence of random sounds or ''noise'' to produce a sound without any perceived pitch. See timbre

In music, timbre ( ), also known as tone color or tone quality (from psychoacoustics), is the perceived sound quality of a musical note, sound or musical tone, tone. Timbre distinguishes different types of sound production, such as choir voice ...

. Unpitched percussion is typically used to maintain a rhythm

Rhythm (from Greek , ''rhythmos'', "any regular recurring motion, symmetry") generally means a " movement marked by the regulated succession of strong and weak elements, or of opposite or different conditions". This general meaning of regular recu ...

or to provide accents, and its sounds are unrelated to the melody

A melody (from Greek language, Greek μελῳδία, ''melōidía'', "singing, chanting"), also tune, voice or line, is a Linearity#Music, linear succession of musical tones that the listener perceives as a single entity. In its most liter ...

and harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. However ...

of the music. Within the orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families.

There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* bowed string instruments, such as the violin, viola, c ...

unpitched percussion is termed auxiliary percussion

The percussion section is one of the main divisions of the orchestra and the concert band. It includes most percussion instruments and all unpitched instruments.

The percussion section is itself divided into three subsections:

* Pitched percus ...

, and this subsection of the percussion section

The percussion section is one of the main divisions of the orchestra and the concert band. It includes most percussion instruments and all unpitched instruments.

The percussion section is itself divided into three subsections:

* Pitched percuss ...

includes all unpitched instruments of the orchestra no matter how they are played, for example the pea whistle

A whistle is an instrument which produces sound from a stream of gas, most commonly air. It may be mouth-operated, or powered by air pressure, steam, or other means. Whistles vary in size from a small slide whistle or nose flute type to a larg ...

and siren

Siren or sirens may refer to:

Common meanings

* Siren (alarm), a loud acoustic alarm used to alert people to emergencies

* Siren (mythology), an enchanting but dangerous monster in Greek mythology

Places

* Siren (town), Wisconsin

* Siren, Wisc ...

.

Traditional music

Antiquity

Although percussion instruments were generally rather unimportant inancient Greek music

Music was almost universally present in ancient Greek society, from marriages, funerals, and religious ceremonies to theatre, folk music, and the ballad-like reciting of epic poetry. It thus played an integral role in the lives of ancient Greek ...

, two exceptions were in dance music and ritual music of orgiastic cults. The former required instruments providing a sharply defined rhythm, particularly '' krotala'' (clappers with a dry, nonresonant sound) and ''kymbala'' (similar to finger-cymbals). The cult rituals required more exciting noises, such as those produced by drums, cymbals, jingles, and the ''rhombos'' ( bull-roarer), which produced a demonic roaring noise particularly important to the ceremonies of the priests of Cybele

Cybele ( ; Phrygian: ''Matar Kubileya/Kubeleya'' "Kubileya/Kubeleya Mother", perhaps "Mountain Mother"; Lydian ''Kuvava''; el, Κυβέλη ''Kybele'', ''Kybebe'', ''Kybelis'') is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible forer ...

. Athenaeus

Athenaeus of Naucratis (; grc, Ἀθήναιος ὁ Nαυκρατίτης or Nαυκράτιος, ''Athēnaios Naukratitēs'' or ''Naukratios''; la, Athenaeus Naucratita) was a Greek rhetorician and grammarian, flourishing about the end of th ...

(''The Deipnosophists

The ''Deipnosophistae'' is an early 3rd-century AD Greek work ( grc, Δειπνοσοφισταί, ''Deipnosophistaí'', lit. "The Dinner Sophists/Philosophers/Experts") by the Greek author Athenaeus of Naucratis. It is a long work of liter ...

'' xiv.38) quotes a passage from a now-lost play, ''Semele'', by Diogenes the Tragedian, describing an all-percussion accompaniment to some of these rites:

Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Ancient Rome, Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditiona ...

in ''Ab urbe condita

''Ab urbe condita'' ( 'from the founding of the City'), or ''anno urbis conditae'' (; 'in the year since the city's founding'), abbreviated as AUC or AVC, expresses a date in years since 753 BC, the traditional founding of Rome. It is an exp ...

'' xxxix.8–10, written in the late first century BC. He describes "a Greek of mean condition ... a low operator in sacrifices, and a soothsayer ... a teacher of secret mysteries" who imported to Etruria

Etruria () was a region of Central Italy, located in an area that covered part of what are now most of Tuscany, northern Lazio, and northern and western Umbria.

Etruscan Etruria

The ancient people of Etruria

are identified as Etruscan civiliza ...

and then to Rome a Dionysian cult which attracted a large following. All manner of debaucheries were practised by this cult, including rape and

Polynesia

A Tahitian traditional dance genre dating back to before the first contact with European explorers is '' ʻōteʻa'', danced by a group of men accompanied solely by a drum ensemble. The drums consist of a slit-log drum called ''tō‘ere'' (which provides the main rhythmic pattern), a single-headed upright drum called ''fa‘atete'', a single-headed hand drum called ''pahu tupa‘i rima'', and a double-headed bass drum called ''tariparau''.Asia

InShaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see #Name, § Name) is a landlocked Provinces of China, province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichu ...

in the north of China, drum ensembles accompany ''yangge

Yangge () is a form of Chinese folk dance developed from a dance known in the Song dynasty as Village Music (). It is very popular in northern China and is one of the most representative form of folk arts. It is popular in both the countryside and ...

'' dance, and in the Tianjin

Tianjin (; ; Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Tientsin (), is a municipality and a coastal metropolis in Northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities in Mainland China, with a total popul ...

area there are ritual percussion ensembles such as the ''Fagu hui'' Dharma-drumming associations, often consisting of dozens of musicians. In Korea, a style of folk music called ''Nongak'' (farmers' music) or ''pungmul

''Pungmul'' (; ) is a Korean folk music tradition that includes drumming, dancing, and singing. Most performances are outside, with dozens of players all in constant motion. ''Pungmul'' is rooted in the ''dure'' (collective labor) farming cultur ...

'' has been performed for many hundred years, both by local players and by professional touring bands at concerts and festivals. It is loud music meant for outdoor performance, played on percussion instruments such as the drums called ''janggu'' and ''puk'', and the gongs ''ching'' and ''kkwaenggwari

The ''kkwaenggwari'' () is a small flat gong used primarily in the folk music of Korea. It is made of brass and is played with a hard stick. It produces a distinctively high-pitched, metallic tone that breaks into a cymbal-like crashing timbr ...

''. It originated in simple work rhythms to assist repetitive tasks carried out by field workers.

South Asian music places a special emphasis on drumming, which is freed from the primary time-keeping function of drumming found in other part of the world. In North India, secular processional bands play an important role in civic festival parades and the ''bārāt'' processions leading a groom's wedding party to the bride's home or the hall where a wedding is held. These bands vary in makeup, depending on the means of the families employing them and according to changing fashions over time, but the core instrumentation is a small group of percussionists, usually playing a frame drum (''ḍaphalā''), a gong, and a pair of kettledrums (''nagāṛā''). Better-off families will add shawms (

South Asian music places a special emphasis on drumming, which is freed from the primary time-keeping function of drumming found in other part of the world. In North India, secular processional bands play an important role in civic festival parades and the ''bārāt'' processions leading a groom's wedding party to the bride's home or the hall where a wedding is held. These bands vary in makeup, depending on the means of the families employing them and according to changing fashions over time, but the core instrumentation is a small group of percussionists, usually playing a frame drum (''ḍaphalā''), a gong, and a pair of kettledrums (''nagāṛā''). Better-off families will add shawms (shehnai

The ''shehnai'' is a musical instrument, originating from the Indian subcontinent. It is made of wood, with a double reed at one end and a metal or wooden flared bell at the other end.Kerala

Kerala ( ; ) is a state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile regions of Cochin, Malabar, South ...

, called ''kṣētram vādyam''. It includes three main genres, all focussed on rhythm and featuring unpitched percussion. ''Thayambaka

Thayambaka or tayambaka is a type of solo chenda performance that developed in the south Indian state of Kerala, in which the main player at the centre improvises rhythmically on the beats of half-a-dozen or a few more chenda and ilathalam pla ...

'' in particular is a virtuoso genre for unpitched percussion only: a solo double-headed cylindrical drum called chenda

The Chenda ( ml, ചെണ്ട, ) is a cylindrical percussion instrument originating in the state of Kerala and widely used in Tulu Nadu of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu in India. In Tulu Nadu (Coastal Karnataka), it is known as ''chende''. ...

, played with a pair of sticks, and accompanied by other ''chenda'' and elathalam

Elathalam, or Ilathalam, is a metallic musical instrument which resembles a miniature pair of cymbals. This instrument from Kerala in southern India is completely made out of bronze and has two pieces in it.

Elathalam is played by keeping one ...

(pairs of cymbals). The other two genres, panchavadyam

Panchavadyam (Malayalam: പഞ്ചവാദ്യം), literally meaning an orchestra of five instruments, is basically a temple art form that has evolved in Kerala. Of the five instruments, four — timila, maddalam, ilathalam and idakka ...

and pandi melam

Pandi melam is a classical percussion concert or melam (ensemble) led by the ethnic Kerala instrument called the chenda and accompanied by ilathalam (cymbals), kuzhal and Kombu.

A full-length Pandi, a melam based on a thaalam ( taal) with se ...

add wind instruments to the ensemble, but only as accompaniment to the primary drums and cymbals. A ''panchavadyam'' piece typically lasts about an hour, while a ''pandi melam'' performance may be as long as four hours.

Turkey

The Turkish

The Turkish janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ( ...

military corps had included since the 14th century bands called ''mehter'' or '' mehterân'' which, like many other earlier military bands in Asia featured a high proportion of drums, cymbals, and gongs, along with trumpets and shawms. The high level of noise was pertinent to their function of playing on the battlefield to inspire the soldiers. The focus in these bands was on percussion. A full ''mehterân'' could include several bass drums, multiple pairs of cymbals, small kettledrums, triangles, tambourines, and one or more Turkish crescent

A Turkish crescent, (a smaller version is called a çevgen or ''çağana'' (Tr.), Turkish jingle, Jingling Johnny, ' (Ger.), ' or ''pavillon chinois'' (Fr.)), is a percussion instrument traditionally used by military bands internationally. In some ...

s.

Europe

Through Turkish ambassadorial visits and other contacts, Europeans gained a fascination with the "barbarous", noisy sound of these bands, and a number of European courts established "Turkish" military ensembles in the late-17th and early 18th centuries. The music played by these ensembles, however, were not authentically Turkish music, but rather compositions in the prevalent European manner. The general enthusiasm quickly spread to opera and concert orchestras, where the combination of bass drum, cymbals, tambourines, and triangles were collectively referred to as "Turkish music". The best-known examples include Haydn's Symphony No. 100, which acquired its nickname, "The Military", from its use of these instruments, and three of Beethoven's works: the "alla marcia" section from the finale of his Symphony No. 9 (an early sketch reads: "end of the Symphony with Turkish music"), his "Wellington's Victory

''Wellington's Victory'', or the ''Battle of Vitoria'' (also called the ''Battle Symphony''; in German: ''Wellingtons Sieg oder die Schlacht bei Vittoria''), Op. 91, is a 15-minute-long orchestral work composed by Ludwig van Beethoven to comm ...

"—or ''Battle'' Symphony—with picturesque sound effects (the bass drums are designated as "cannons", side drums represent opposing troops of soldiers, and ratchets the sound of rifle fire), and the "Turkish March" (with the expected bass drum, cymbals, and triangle) and the "Chorus of Dervishes" from his incidental music to ''The Ruins of Athens

''The Ruins of Athens'' (''Die Ruinen von Athen''), Op. 113, is a set of incidental music pieces written in 1811 by Ludwig van Beethoven. The music was written to accompany the play of the same name by August von Kotzebue, for the dedication of ...

'', where he calls for the use of every available noisy instrument: castanets, cymbals, and so forth. By the end of the 18th century, the ''batterie turque'' had become so fashionable that keyboard instruments were fitted with devices to simulate the bass drum (a mallet with a padded head hitting the back of the sounding board), cymbals (strips of brass striking the lower strings), and the triangle and bells (small metal objects struck by rods). Even when percussion instruments were not actually employed, certain ''alla turca'' "tricks" were used to imitate these percussive effects. Examples include the "Rondo alla turca" from Mozart's Piano Sonata, K. 331, and part of the finale of his Violin Concerto, K. 219.

=Harpsichord, piano, and organ

= At about the same time that "Turkish music" was coming into vogue in Europe, a fashion for programmatic keyboard music opened the way for the introduction of another kind of noise in the form of the keyboard

At about the same time that "Turkish music" was coming into vogue in Europe, a fashion for programmatic keyboard music opened the way for the introduction of another kind of noise in the form of the keyboard cluster

may refer to:

Science and technology Astronomy

* Cluster (spacecraft), constellation of four European Space Agency spacecraft

* Asteroid cluster, a small asteroid family

* Cluster II (spacecraft), a European Space Agency mission to study t ...

, played with the fist, flat of the hand, forearm, or even an auxiliary object placed on the keyboard. On the harpsichord and piano, this device was found mainly in "battle" pieces, where it was used to represent cannon fire. The earliest instance was by Jean-François Dandrieu

Jean-François Dandrieu, also spelled D'Andrieu (c. 168217 January 1738) was a French Baroque composer, harpsichordist and organist.

Biography

He was born in Paris into a family of artists and musicians. A gifted and precocious child, he gave hi ...

, in ''Les Caractères de la guerre'' (1724), and for the next hundred years it remained predominantly a French feature, with examples by Michel Corrette

Michel Corrette (10 April 1707 – 21 January 1795) was a French composer, organist and author of musical method books.

Life

Corrette was born in Rouen, Normandy. His father, Gaspard Corrette, was an organist and composer. Little is known of ...

(''La Victoire d'un combat naval, remportée par une frégate contre plusieurs corsaires réunis'', 1780), Claude-Bénigne Balbastre

Claude Balbastre (8 December 1724 – 9 May 1799) was a French composer, organist, harpsichordist and fortepianist. He was one of the most famous musicians of his time.

Life

Claude Balbastre was born in Dijon in 1724. Although his exact birthdat ...

(''March des Marseillois'', 1793), Pierre Antoine César (''La Battaille de Gemmap, ou la prise de Mons'', ca. 1794), and Jacques-Marie Beauvarlet-Charpentier

Jacques-Marie Beauvarlet-Charpentier (31 July 1766 – 7 September 1834) was a French organist and composer..

Biography

Born in Lyon, Jacques-Marie Beauvarlet-Charpentier succeeded his father Jean-Jacques Beauvarlet Charpentier at the pipe orga ...

(''Bataille d'Austerlitz'', 1805). In 1800, Bernard Viguerie introduced the sound to chamber music, in the keyboard part of a piano trio

A piano trio is a group of piano and two other instruments, usually a violin and a cello, or a piece of music written for such a group. It is one of the most common forms found in classical chamber music. The term can also refer to a group of musi ...

titled ''La Bataille de Maringo, pièce militaire et historique''. The last time this pianistic "cannon" effect was used before the 20th century was in 1861, in a depiction of the then-recent The Battle of Manassas in a piece by the black American piano virtuoso "Blind Tom" Bethune, a piece that also feature vocalised sound-effect noises.

Clusters were also used on the organ, where they proved more versatile (or their composers more imaginative). Their most frequent use on this instrument was to evoke the sound of thunder, but also to portray sounds of battle, storms at sea, earthquakes, and Biblical scenes such as the fall of the walls of Jericho and visions of the apocalypse. The noisy sound nevertheless remained a special sound effect, and was not integrated into the general texture of the music. The earliest examples of "organ thunder" are from descriptions of improvisations by Abbé Vogler in the last quarter of the 18th century. His example was soon imitated by Justin Heinrich Knecht

Justinus or Justin Heinrich Knecht (30 September 1752 – 1 December 1817) was a German composer, organist, and music theorist.

Biography

He was born in Biberach an der Riss, where he learnt to play the organ, keyboard, violin, and singing. He a ...

(''Die durch ein Donerwetter'' ''unterbrochne Hirtenwonne'', 1794), Michel Corrette (who employed a length of wood on the pedal board and his elbow on the lowest notes of the keyboard during some improvisations), and also in composed works by Guillaume Lasceux (''Te Deum'': "Judex crederis", 1786), Sigismond Neukomm (''A Concert on a Lake, Interrupted by a Thunderstorm''), Louis James Alfred Lefébure-Wély Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis ...

(''Scène pastorale'', 1867), Jacques Vogt (''Fantaisie pastorale et orage dans les Alpes'', ca. 1830), and Jules Blanc (''La procession'', 1859). The most notable 19th-composer to use such organ clusters was Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the h ...

. The storm music which opens his opera ''Otello

''Otello'' () is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on Shakespeare's play ''Othello''. It was Verdi's penultimate opera, first performed at the Teatro alla Scala, Milan, on 5 February 1887.

Th ...

'' (1887) includes an organ cluster (C, C, D) that is also the longest notated duration of any scored musical texture.

=Bowed strings

= Percussive effects in imitation of drumming had been introduced to bowed-string instruments by early in the 17th century. The earliest known use of ''

Percussive effects in imitation of drumming had been introduced to bowed-string instruments by early in the 17th century. The earliest known use of ''col legno

In music for bowed string instrument

Bowed string instruments are a subcategory of string instruments that are played by a bow rubbing the strings. The bow rubbing the string causes vibration which the instrument emits as sound.

Despite th ...

'' (tapping on the strings with the back of the bow) is found in Tobias Hume

Tobias Hume (possibly 1579 – 16 April 1645) was a Scottish composer, viol player and soldier.

Little is known of his life. Some have suggested that he was born in 1579 because he was admitted to the London Charterhouse in 1629, a prerequisit ...

's ''First Part of Ayres'' for unaccompanied viola da gamba

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitc ...

(1605), in a piece titled ''Harke, Harke''. Carlo Farina

Carlo Farina (ca. 1600 – July 1639) was an Italian composer, conductor and violinist of the Early Baroque era.

Life

Farina was born at Mantua. He presumably received his first lessons from his father, who was '' sonatore di viola'' at ...

, an Italian violinist active in Germany, also used ''col legno'' to mimic the sound of a drum in his ''Capriccio stravagante'' for four stringed instruments (1627), where he also used devices such as ''glissando

In music, a glissando (; plural: ''glissandi'', abbreviated ''gliss.'') is a glide from one pitch to another (). It is an Italianized musical term derived from the French ''glisser'', "to glide". In some contexts, it is distinguished from the co ...

'', tremolo

In music, ''tremolo'' (), or ''tremolando'' (), is a trembling effect. There are two types of tremolo.

The first is a rapid reiteration:

* Of a single Musical note, note, particularly used on String instrument#Bowing, bowed string instrument ...

, pizzicato

Pizzicato (, ; translated as "pinched", and sometimes roughly as "plucked") is a playing technique that involves plucking the strings of a string instrument. The exact technique varies somewhat depending on the type of instrument :

* On bowed ...

, and ''sul ponticello

A variety of musical terms are likely to be encountered in Sheet music, printed scores, music reviews, and program notes. Most of the terms Italian musical terms used in English, are Italian, in accordance with the Italian origins of many Europea ...

'' to imitate the noises of barnyard animals (cat, dog, chicken). Later in the century, Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber ( bapt. 12 August 1644, Stráž pod Ralskem – 3 May 1704, Salzburg) was a Bohemian-Austrian composer and violinist. Biber worked in Graz and Kroměříž before he illegally left his employer, Prince-Bishop Karl L ...

, in certain movements of ''Battalia'' (1673), added to these effects the device of placing a sheet of paper under the A string of the double bass, in order to imitate the dry rattle of a snare drum, and in "Die liederliche Gesellschaft von allerley Humor" from the same programmatic battle piece, superimposed eight different melodies in different keys, producing in places dense orchestral clusters. He also uses the percussive snap of fortissimo ''pizzicato'' to represent gunshots.

An important aspect of all of these examples of noise in European keyboard and string music before the 19th century is that they are used as sound effects

A sound effect (or audio effect) is an artificially created or enhanced sound, or sound process used to emphasize artistic or other content of films, television shows, live performance, animation, video games, music, or other media. Traditi ...

in programme music. Sounds that would likely cause offense in other musical contexts are made acceptable by their illustrative function. Over time, their evocative effect was weakened as at the same time they became incorporated more generally into abstract musical contexts.

=Orchestras

=Orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families.

There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* bowed string instruments, such as the violin, viola, c ...

s continued to use noise in the form of a percussion section

The percussion section is one of the main divisions of the orchestra and the concert band. It includes most percussion instruments and all unpitched instruments.

The percussion section is itself divided into three subsections:

* Pitched percuss ...

, which expanded though the 19th century: Berlioz was perhaps the first composer to thoroughly investigate the effects of different mallets on the tone color of timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionall ...

.Hast, Cowdery, and Scott 1999, 149. However, before the 20th century, percussion instruments played a very small role in orchestral music and mostly served for punctuation, to highlight passages, or for novelty. But by the 1940s, some composers were influenced by non-Western music as well as jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a major ...

and popular music

Popular music is music with wide appeal that is typically distributed to large audiences through the music industry. These forms and styles can be enjoyed and performed by people with little or no musical training.Popular Music. (2015). ''Fun ...

, and began incorporating marimba

The marimba () is a musical instrument in the percussion family that consists of wooden bars that are struck by mallets. Below each bar is a resonator pipe that amplifies particular harmonics of its sound. Compared to the xylophone, the timbre ...

s, vibraphone

The vibraphone is a percussion instrument in the metallophone family. It consists of tuned metal bars and is typically played by using mallets to strike the bars. A person who plays the vibraphone is called a ''vibraphonist,'' ''vibraharpist,' ...

s, xylophone

The xylophone (; ) is a musical instrument in the percussion family that consists of wooden bars struck by mallets. Like the glockenspiel (which uses metal bars), the xylophone essentially consists of a set of tuned wooden keys arranged in the ...

s, bells, gong

A gongFrom Indonesian and ms, gong; jv, ꦒꦺꦴꦁ ; zh, c=鑼, p=luó; ja, , dora; km, គង ; th, ฆ้อง ; vi, cồng chiêng; as, কাঁহ is a percussion instrument originating in East Asia and Southeast Asia. Gongs ...

s, cymbal

A cymbal is a common percussion instrument. Often used in pairs, cymbals consist of thin, normally round plates of various alloys. The majority of cymbals are of indefinite pitch, although small disc-shaped cymbals based on ancient designs soun ...

s, and drums.

=Vocal music

= In vocal music, noisy nonsense syllables were used to imitate battle drums and cannon fire long beforeClément Janequin

Clément Janequin (c. 1485 – 1558) was a French composer of the Renaissance. He was one of the most famous composers of popular chansons of the entire Renaissance, and along with Claudin de Sermisy, was hugely influential in the development o ...

made these devices famous in his programmatic chanson ''La bataille'' (The Battle) in 1528. Unpitched or semi-pitched performance was introduced to formal composition in 1897 by Engelbert Humperdinck, in the first version of his melodrama

A modern melodrama is a dramatic work in which the plot, typically sensationalized and for a strong emotional appeal, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodramas typically concentrate on dialogue that is often bombastic or exces ...

, ''Königskinder

' (German for ''King's Children'' or “Royal Children”) is a stage work by Engelbert Humperdinck that exists in two versions: as a melodrama and as an opera or more precisely a '' Märchenoper''. The libretto was written by Ernst Rosmer (pen ...

''. This style of performance is believed to have been used previously by singers of lieder

In Western classical music tradition, (, plural ; , plural , ) is a term for setting poetry to classical music to create a piece of polyphonic music. The term is used for any kind of song in contemporary German, but among English and French sp ...

and popular songs. The technique is best known, however, from somewhat later compositions by Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

, who introduced it for solo voices in his ''Gurrelieder

' is a large cantata for five vocal soloists, narrator, chorus and large orchestra, composed by Arnold Schoenberg, on poems by the Danish novelist Jens Peter Jacobsen (translated from Danish to German by ). The title means "songs of Gurre", re ...

'' (1900–1911), ''Pierrot Lunaire

''Dreimal sieben Gedichte aus Albert Girauds "Pierrot lunaire"'' ("Three times Seven Poems from Albert Giraud's 'Pierrot lunaire), commonly known simply as ''Pierrot lunaire'', Op. 21 ("Moonstruck Pierrot" or "Pierrot in the Moonlight"), is a m ...

'' (1913), and the opera ''Moses und Aron

''Moses und Aron'' (English: ''Moses and Aaron'') is a three-act opera by Arnold Schoenberg with the third act unfinished. The German libretto is by the composer after the Book of Exodus. Hungarian composer Zoltán Kocsis completed the last act w ...

'' (1930–1932), and for chorus in ''Die Glückliche Hand'' (1910–1913). Later composers who have made prominent use of the device include Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mont ...

, Luciano Berio

Luciano Berio (24 October 1925 – 27 May 2003) was an Italian composer noted for his experimental work (in particular his 1968 composition ''Sinfonia'' and his series of virtuosic solo pieces titled ''Sequenza''), and for his pioneering work ...

, Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

(in ''Death in Venice

''Death in Venice ''(German: ''Der Tod in Venedig'') is a novella by German author Thomas Mann, published in 1912. It presents an ennobled writer who visits Venice and is liberated, uplifted, and then increasingly obsessed by the sight of a Poli ...

'', 1973), Mauricio Kagel

Mauricio Raúl Kagel (; 24 December 1931 – 18 September 2008) was an Argentine-German composer.

Biography

Kagel was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, into an Ashkenazi Jewish family that had fled from Russia in the 1920s . He studied music, his ...

, and Wolfgang Rihm

Wolfgang Rihm (born 13 March 1952) is a German composer and academic teacher. He is musical director of the Institute of New Music and Media at the University of Music Karlsruhe and has been composer in residence at the Lucerne Festival and the Sa ...

(in his opera ''Jakob Lenz

Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz (23 January 1751, or 12 January in the Julian calendar – 4 June 1792, or 24 May in the Julian calendar) was a Baltic German writer of the ''Sturm und Drang'' movement.

Life

Lenz was born in Sesswegen (Cesvaine), ...

'', 1977–1978, amongst other works). A well-known example of this style of performance in popular music was Rex Harrison

Sir Reginald Carey "Rex" Harrison (5 March 1908 – 2 June 1990) was an English actor. Harrison began his career on the stage in 1924. He made his West End debut in 1936 appearing in the Terence Rattigan play ''French Without Tears'', in what ...

's portrayal of Professor Henry Higgins in ''My Fair Lady

''My Fair Lady'' is a musical based on George Bernard Shaw's 1913 play ''Pygmalion'', with a book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe. The story concerns Eliza Doolittle, a Cockney flower girl who takes speech lessons f ...

''. Another form of unpitched vocal music is the speaking chorus, prominently represented by Ernst Toch

Ernst Toch (; 7 December 1887 – 1 October 1964) was an Austrian composer of classical music and film scores. He sought throughout his life to introduce new approaches to music.

Biography

Toch was born in Leopoldstadt, Vienna, into the family ...

's 1930 ''Geographical Fugue

The ''Geographical Fugue'' or ''Fuge aus der Geographie'' is the most famous piece for spoken chorus by Ernst Toch.

Toch was a prominent composer in 1920s Berlin, and singlehandedly invented the idiom of the "Spoken Chorus".

The work was compo ...

'', an example of the Gebrauchsmusik

() is a German term, meaning "utility music", for music that exists not only for its own sake, but which was composed for some specific, identifiable purpose. This purpose can be a particular historical event, like a political rally or a militar ...

fashionable in Germany at that time.

=Machine music

= In the 1920s a fashion emerged for composing what was called "machine music"—the depiction in music of the sounds of factories, locomotives, steamships, dynamos, and other aspects of recent technology that both reflected modern, urban life and appealed to the then-prevalent spirit of objectivity, detachment, and directness. Representative works in this style, which features motoric and insistent rhythms, a high level of dissonance, and often large percussion batteries, are

In the 1920s a fashion emerged for composing what was called "machine music"—the depiction in music of the sounds of factories, locomotives, steamships, dynamos, and other aspects of recent technology that both reflected modern, urban life and appealed to the then-prevalent spirit of objectivity, detachment, and directness. Representative works in this style, which features motoric and insistent rhythms, a high level of dissonance, and often large percussion batteries, are George Antheil

George Johann Carl Antheil (; July 8, 1900 – February 12, 1959) was an American avant-garde composer, pianist, author, and inventor whose modernist musical compositions explored the modern sounds – musical, industrial, and mechanical – of t ...

's ''Ballet mécanique

''Ballet Mécanique'' (1923–24) is a Dadaist post-Cubist art film conceived, written, and co-directed by the artist Fernand Léger in collaboration with the filmmaker Dudley Murphy (with cinematographic input from Man Ray).Chilvers, Ian & Gl ...

'' (1923–1925), Arthur Honegger

Arthur Honegger (; 10 March 1892 – 27 November 1955) was a Swiss composer who was born in France and lived a large part of his life in Paris. A member of Les Six, his best known work is probably ''Antigone'', composed between 1924 and 1927 to ...

's ''Pacific 231

''Pacific 231'' is an orchestral work by Arthur Honegger, written in 1923.

It is one of his most frequently performed works.

Description

The popular interpretation of the piece is that it depicts a steam locomotive, one that is supported by th ...

'' (1923), Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev; alternative transliterations of his name include ''Sergey'' or ''Serge'', and ''Prokofief'', ''Prokofieff'', or ''Prokofyev''., group=n (27 April .S. 15 April1891 – 5 March 1953) was a Russian composer, p ...

's ballet '' Le pas d'acier'' (The Steel Leap, 1925–1926), Alexander Mosolov

Alexander Vasilyevich MosolovMosolov's name is transliterated variously and inconsistently between sources. Alternative spellings of Alexander include Alexandr, Aleksandr, Aleksander, and Alexandre; variations on Mosolov include Mossolov and Mossol ...

's ''Iron Foundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

'' (an orchestral episode from his ballet ''Steel'', 1926–1927), and Carlos Chávez

Carlos Antonio de Padua Chávez y Ramírez (13 June 1899 – 2 August 1978) was a Mexican composer, conductor, music theorist, educator, journalist, and founder and director of the Mexican Symphonic Orchestra. He was influenced by nativ ...

's ballet '' Caballos de vapor'', also titled ''HP'' (Horsepower, 1926–1932). This trend reached its apex in the music of Edgard Varèse

Edgard Victor Achille Charles Varèse (; also spelled Edgar; December 22, 1883 – November 6, 1965) was a French-born composer who spent the greater part of his career in the United States. Varèse's music emphasizes timbre and rhythm; he coined ...

, who composed ''Ionisation

Ionization, or Ionisation is the process by which an atom or a molecule acquires a negative or positive charge by gaining or losing electrons, often in conjunction with other chemical changes. The resulting electrically charged atom or molecu ...

'' in 1931, a "study in pure sonority and rhythm" for an ensemble of thirty-five unpitched percussion instruments.

=Percussion ensembles

= Following Varèse's example, a number of other important works forpercussion ensemble

A percussion ensemble is a musical ensemble consisting of only percussion instruments. Although the term can be used to describe any such group, it commonly refers to groups of classically trained percussionists performing primarily classical m ...

were composed in the 1930s and 40s: Henry Cowell

Henry Dixon Cowell (; March 11, 1897 – December 10, 1965) was an American composer, writer, pianist, publisher and teacher. Marchioni, Tonimarie (2012)"Henry Cowell: A Life Stranger Than Fiction" ''The Juilliard Journal''. Retrieved 19 June 202 ...

's ''Ostinato Pianissimo'' (1934) combines Latin American, European, and Asian percussion instruments; John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading fi ...

's '' First Construction (in Metal)'' (1939) employs differently pitched thunder sheets, brake drums, gongs, and a water gong; Carlos Chávez's Toccata

Toccata (from Italian ''toccare'', literally, "to touch", with "toccata" being the action of touching) is a virtuoso piece of music typically for a keyboard or plucked string instrument featuring fast-moving, lightly fingered or otherwise virtuo ...

for percussion instruments (1942) requires six performers to play a large number of European and Latin-American drums and other unpitched percussion together with a few tuned instruments such as xylophone, tubular chimes, and glockenspiel; Lou Harrison

Lou Silver Harrison (May 14, 1917 – February 2, 2003) was an American composer, music critic, music theorist, painter, and creator of unique musical instruments. Harrison initially wrote in a dissonant, ultramodernist style similar to his for ...

, in works such as the ''Canticles'' nos. 1 and 3 (1940 and 1942), ''Song of Queztalcoatl'' (1941), Suite for Percussion (1942), and—in collaboration with John Cage—''Double Music'' (1941) explored the use of "found" instruments, such as brake drums, flowerpots, and metal pipes. In all of these works, elements such as timbre, texture, and rhythm take precedence over the usual Western concepts of harmony and melody.

Experimental and avant-garde music

Use of noise was central to the development of

Use of noise was central to the development of experimental music

Experimental music is a general label for any music or music genre that pushes existing boundaries and genre definitions. Experimental compositional practice is defined broadly by exploratory sensibilities radically opposed to, and questioning of, ...

and avant-garde music

Avant-garde music is music that is considered to be at the forefront of innovation in its field, with the term "avant-garde" implying a critique of existing aesthetic conventions, rejection of the status quo in favor of unique or original elemen ...

in the mid 20th century. Noise was used in important, new ways.

Edgard Varèse challenged traditional conceptions of musical and non-musical sound and instead incorporated noise based sonorities into his compositional work, what he referred to as "organised sound." Varèse stated that "to stubbornly conditioned ears, anything new in music has always been called noise", and he posed the question, "what is music but organized noises?".

In the years immediately following the First World War, Henry Cowell

Henry Dixon Cowell (; March 11, 1897 – December 10, 1965) was an American composer, writer, pianist, publisher and teacher. Marchioni, Tonimarie (2012)"Henry Cowell: A Life Stranger Than Fiction" ''The Juilliard Journal''. Retrieved 19 June 202 ...

composed a number of piano pieces featuring tone clusters and direct manipulation of the piano's strings. One of these, titled ''The Banshee'' (1925), features sliding and shrieking sounds suggesting the terrifying cry of the banshee

A banshee ( ; Modern Irish , from sga, ben síde , "woman of the fairy mound" or "fairy woman") is a female spirit in Irish folklore who heralds the death of a family member, usually by screaming, wailing, shrieking, or keening. Her name is c ...

from Irish folklore.Simms 1986, 317.

In 1938 for a dance composition titled ''Bacchanale'', John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading fi ...

invented the prepared piano

A prepared piano is a piano that has had its sounds temporarily altered by placing bolts, screws, mutes, rubber erasers, and/or other objects on or between the strings. Its invention is usually traced to John Cage's dance music for ''Bacchanale' ...

, producing both transformed pitches and colorful unpitched

An unpitched percussion instrument is a percussion instrument played in such a way as to produce sounds of indeterminate pitch, or an instrument normally played in this fashion.

Unpitched percussion is typically used to maintain a rhythm or to ...

sounds from the piano.Simms 1986, 319–320. Many variations, such as prepared guitar

A prepared guitar is a guitar that has had its timbre altered by placing various objects on or between the instrument's strings, including other extended techniques. This practice is sometimes called tabletop guitar, because many prepared guitar ...

, have followed. In 1952, Cage wrote '' 4′33″'', in which there is no deliberate sound at all, but only whatever background noise occurs during the performance.

Karlheinz Stockhausen

Karlheinz Stockhausen (; 22 August 1928 – 5 December 2007) was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important but also controversial composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. He is known for his groun ...

employed noise in vocal compositions, such as ''Momente

''Momente'' (Moments) is a work by the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, written between 1962 and 1969, scored for solo soprano, four mixed choirs, and thirteen instrumentalists (four trumpets, four trombones, three percussionists, and two e ...

'' (1962–1964/69), in which the four choirs clap their hands, talk, and shuffle their feet, in order to mediate between instrumental and vocal sounds as well as to incorporate sounds normally made by audiences into those produced by the performers.Simms 1986, 374.

Robert Ashley

Robert Reynolds Ashley (March 28, 1930 – March 3, 2014) was an American composer, who was best known for his television operas and other theatrical works, many of which incorporate electronics and extended techniques. His works often involve ...

used audio feedback

Audio feedback (also known as acoustic feedback, simply as feedback) is a positive feedback situation which may occur when an acoustic path exists between an audio input (for example, a microphone or guitar pickup) and an audio output (for examp ...

in his avant-garde piece ''The Wolfman'' (1964) by setting up a howl between the microphone and loudspeaker and then singing into the microphone in way that modulated the feedback with his voice.

Electronic music

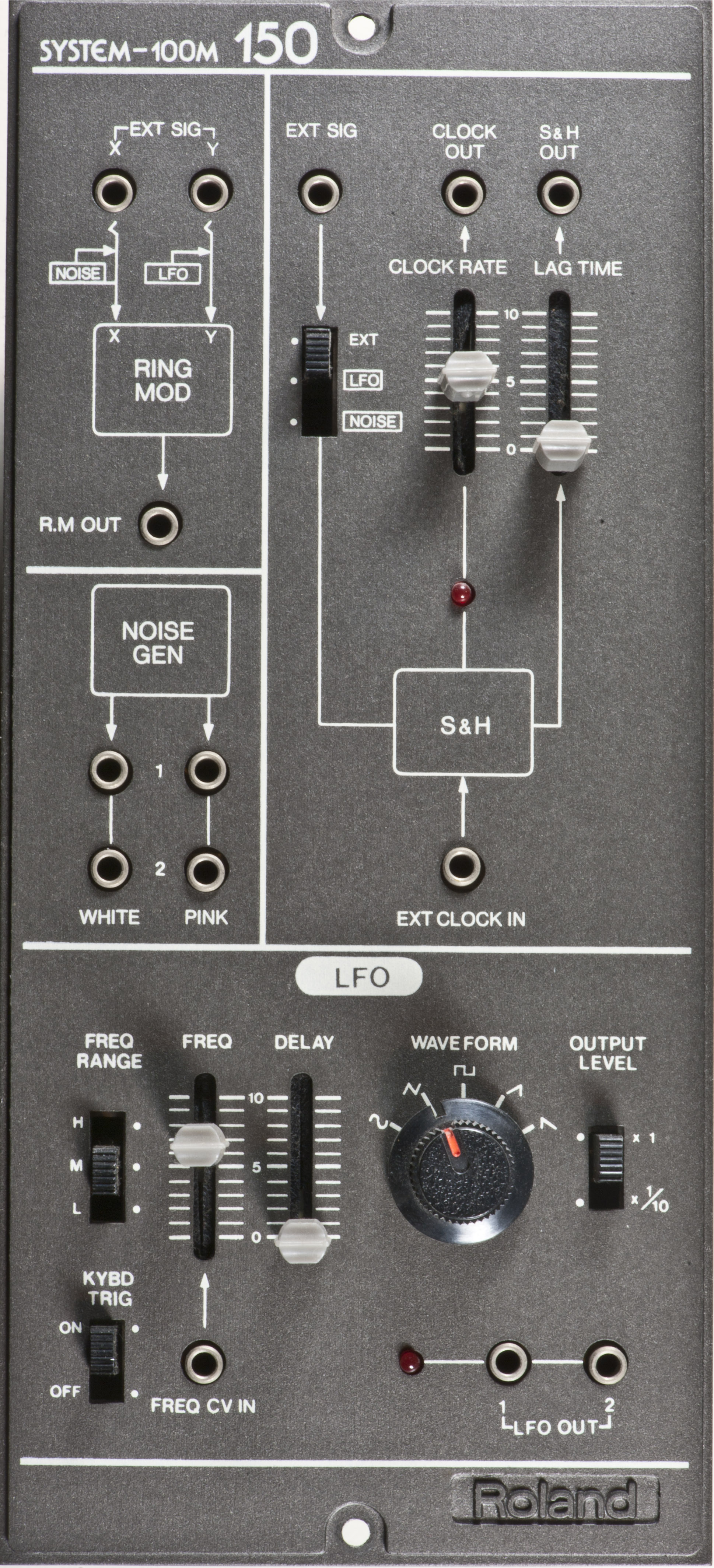

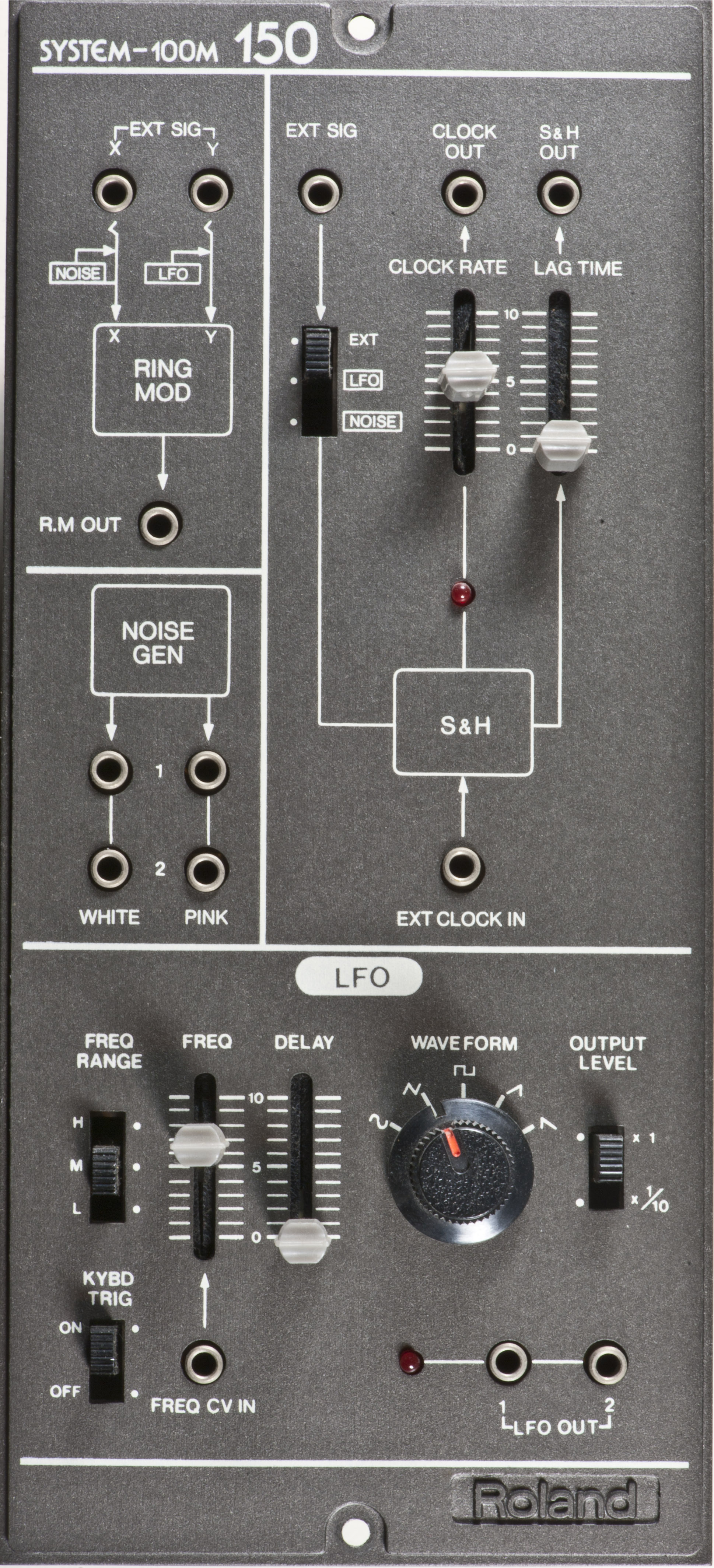

Noise is used as basic tonal material in

Noise is used as basic tonal material in electronic music

Electronic music is a genre of music that employs electronic musical instruments, digital instruments, or circuitry-based music technology in its creation. It includes both music made using electronic and electromechanical means ( electroac ...

.

When pure-frequency sine tones

A sine wave, sinusoidal wave, or just sinusoid is a mathematical curve defined in terms of the '' sine'' trigonometric function, of which it is the graph. It is a type of continuous wave and also a smooth periodic function. It occurs often in ...

were first synthesised into complex timbre

In music, timbre ( ), also known as tone color or tone quality (from psychoacoustics), is the perceived sound quality of a musical note, sound or musical tone, tone. Timbre distinguishes different types of sound production, such as choir voice ...

s, starting in 1953, combinations using inharmonic

In music, inharmonicity is the degree to which the frequencies of overtones (also known as partials or partial tones) depart from whole multiples of the fundamental frequency ( harmonic series).

Acoustically, a note perceived to have a singl ...

relationships (noises) were used far more often than harmonic

A harmonic is a wave with a frequency that is a positive integer multiple of the ''fundamental frequency'', the frequency of the original periodic signal, such as a sinusoidal wave. The original signal is also called the ''1st harmonic'', the ...

ones (tones). Tones were seen as analogous to vowel

A vowel is a syllabic speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness and also in quantity (leng ...

s, and noises to consonant

In articulatory phonetics, a consonant is a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial closure of the vocal tract. Examples are and pronounced with the lips; and pronounced with the front of the tongue; and pronounced wit ...

s in human speech, and because traditional music had emphasised tones almost exclusively, composers of electronic music saw scope for exploration along the continuum stretching from single, pure (sine) tones to white noise

In signal processing, white noise is a random signal having equal intensity at different frequencies, giving it a constant power spectral density. The term is used, with this or similar meanings, in many scientific and technical disciplines, ...

(the densest superimposition of all audible frequencies)—that is, from entirely periodic to entirely aperiodic sound phenomena. In a process opposite to the building up of sine tones into complexes, white noise could be filtered

Filtration is a physical separation process that separates solid matter and fluid from a mixture using a ''filter medium'' that has a complex structure through which only the fluid can pass. Solid particles that cannot pass through the filter m ...

to produce sounds with different bandwidths, called " coloured noises", such as the speech sounds represented in English by ''sh'', ''f'', ''s'', or ''ch''. An early example of an electronic composition composed entirely by filtering white noise in this way is Henri Pousseur

Henri Léon Marie-Thérèse Pousseur (23 June 1929 – 6 March 2009) was a Belgian classical composer, teacher, and music theorist.

Biography

Pousseur was born in Malmedy and studied at the Academies of Music in Liège and in Brussels from 1947 to ...

's ''Scambi

''Scambi'' (Exchanges) is an electronic music composition by the Belgian composer Henri Pousseur, realized in 1957 at the Studio di fonologia musicale di Radio Milano.

History

''Scambi'' is Pousseur's second electronic-music work, following ''Seis ...

'' (Exchanges), realised at the Studio di Fonologia in Milan in 1957.

In the 1980s, electronic white noise machines became commercially available. These are used alone to provide a pleasant background noise and to mask unpleasant noise, a similar role to conventional background music

Background music (British English: piped music) is a mode of musical performance in which the music is not intended to be a primary focus of potential listeners, but its content, character, and volume level are deliberately chosen to affect behav ...

.Heller 2003, 197. This usage can have health applications in the case of individuals struggling with over-stimulation or sensory processing disorder

Sensory processing disorder (SPD, formerly known as sensory integration dysfunction) is a condition in which multisensory input is not adequately processed in order to provide appropriate responses to the demands of the environment. Sensory proces ...

. Also, white noise is sometimes used to mask sudden noise in facilities with research animals.

Rock music

While the electric guitar was originally designed to be simply amplified in order to reproduce its sound at a higher volume, guitarists quickly discovered the creative possibilities of using the amplifier to modify the sound, particularly by extreme settings of tone and volume controls.Bacon 1981, 119

Distortion was at first produced by simply overloading the amplifier to induce

While the electric guitar was originally designed to be simply amplified in order to reproduce its sound at a higher volume, guitarists quickly discovered the creative possibilities of using the amplifier to modify the sound, particularly by extreme settings of tone and volume controls.Bacon 1981, 119

Distortion was at first produced by simply overloading the amplifier to induce clipping

Clipping may refer to:

Words

* Clipping (morphology), the formation of a new word by shortening it, e.g. "ad" from "advertisement"

* Clipping (phonetics), shortening the articulation of a speech sound, usually a vowel

* Clipping (publications) ...

, resulting in a tone rich in harmonics and also in noise, and also producing dynamic range compression

Dynamic range compression (DRC) or simply compression is an audio signal processing operation that reduces the volume of loud sounds or amplifies quiet sounds, thus reducing or ''compressing'' an audio signal's dynamic range. Compression is ...

and therefore sustain (and sometimes destroying the amplifier). Dave Davies

David Russell Gordon Davies (born 3 February 1947) is an English guitarist, singer and songwriter. He was the lead guitarist and backing vocalist for the English rock band the Kinks, which also featured his elder brother Ray Davies. He was in ...

of The Kinks

The Kinks were an English rock band formed in Muswell Hill, north London, in 1963 by brothers Ray and Dave Davies. They are regarded as one of the most influential rock bands of the 1960s. The band emerged during the height of British rhythm ...

took this technique to its logical conclusion by feeding the output from a 60 watt guitar amplifier directly into the guitar input of a second amplifier. The popularity of these techniques quickly resulted in the development of electronic devices such as the fuzz box

Distortion and overdrive are forms of audio signal processing used to alter the sound of amplified electric musical instruments, usually by increasing their gain, producing a "fuzzy", "growling", or "gritty" tone. Distortion is most commonly ...

to produce similar but more controlled effects and in greater variety. Distortion devices also developed into vocal enhancers, effects unit

An effects unit or effects pedal is an electronic device that alters the sound of a musical instrument or other audio source through audio signal processing.

Common effects include distortion/overdrive, often used with electric guitar in el ...

s that electronically enhance a vocal

The human voice consists of sound made by a human being using the vocal tract, including talking, singing, laughing, crying, screaming, shouting, humming or yelling. The human voice frequency is specifically a part of human sound production i ...

performance, including adding ''air'' (noise or distortion, or both). Guitar distortion is often accomplished through use of feedback, overdrive, fuzz, and distortion pedal

Distortion and overdrive are forms of audio signal processing used to alter the sound of amplified electric musical instruments, usually by increasing their gain, producing a "fuzzy", "growling", or "gritty" tone. Distortion is most commonly ...

s.Bennett 2002, 43. Distortion pedals produce a crunchier and grittier tone than an overdrive pedal.

As well as distortion, rock musicians have used audio feedback

Audio feedback (also known as acoustic feedback, simply as feedback) is a positive feedback situation which may occur when an acoustic path exists between an audio input (for example, a microphone or guitar pickup) and an audio output (for examp ...

, which is normally undesirable.Madden 1999, 92. The use of feedback was pioneered by musicians such as John Lennon

John Winston Ono Lennon (born John Winston Lennon; 9 October 19408 December 1980) was an English singer, songwriter, musician and peace activist who achieved worldwide fame as founder, co-songwriter, co-lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist of ...

of The Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatles, most influential band of al ...

, Jeff Beck

Geoffrey Arnold Beck (born 24 June 1944) is an English rock guitarist. He rose to prominence with the Yardbirds and after fronted the Jeff Beck Group and Beck, Bogert & Appice. In 1975, he switched to a mainly instrumental style, with a focus ...

of The Yardbirds

The Yardbirds are an English rock band, formed in London in 1963. The band's core lineup featured vocalist and harmonica player Keith Relf, drummer Jim McCarty, rhythm guitarist and later bassist Chris Dreja and bassist/producer Paul Samwell ...

, Pete Townshend

Peter Dennis Blandford Townshend (; born 19 May 1945) is an English musician. He is co-founder, leader, guitarist, second lead vocalist and principal songwriter of the Who, one of the most influential rock bands of the 1960s and 1970s.

Townsh ...

of The Who