Eukaryotic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Eukaryotes () are

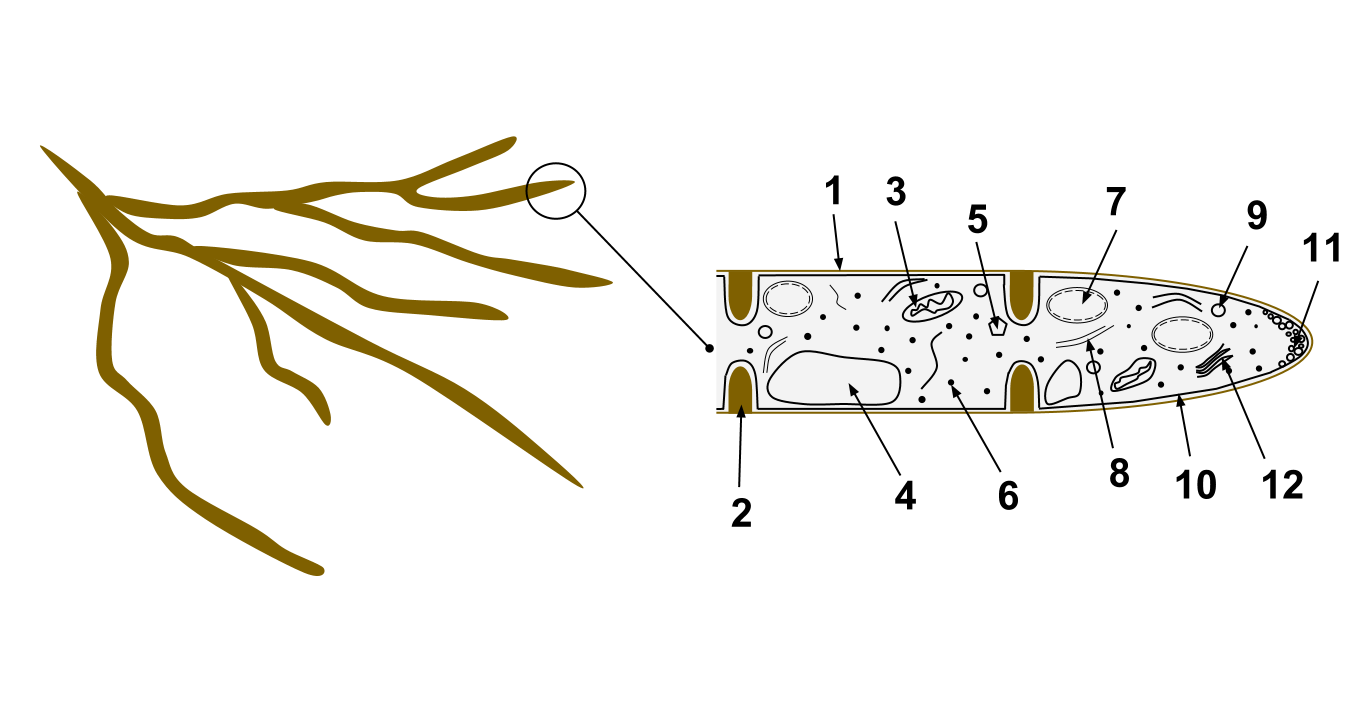

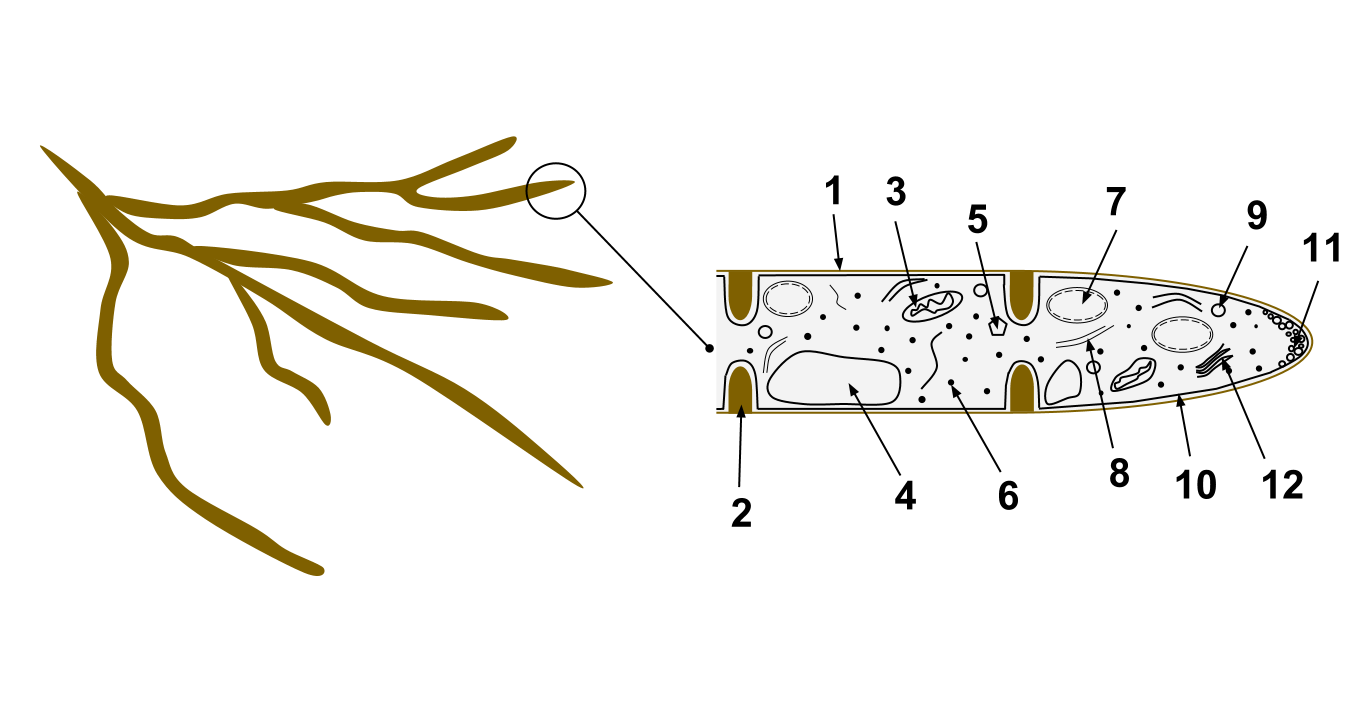

Eukaryote cells include a variety of membrane-bound structures, collectively referred to as the endomembrane system. Simple compartments, called vesicles and vacuoles, can form by budding off other membranes. Many cells ingest food and other materials through a process of endocytosis, where the outer membrane invaginates and then pinches off to form a vesicle. It is probable that most other membrane-bound organelles are ultimately derived from such vesicles. Alternatively some products produced by the cell can leave in a vesicle through exocytosis.

The nucleus is surrounded by a double membrane known as the nuclear envelope, with

Eukaryote cells include a variety of membrane-bound structures, collectively referred to as the endomembrane system. Simple compartments, called vesicles and vacuoles, can form by budding off other membranes. Many cells ingest food and other materials through a process of endocytosis, where the outer membrane invaginates and then pinches off to form a vesicle. It is probable that most other membrane-bound organelles are ultimately derived from such vesicles. Alternatively some products produced by the cell can leave in a vesicle through exocytosis.

The nucleus is surrounded by a double membrane known as the nuclear envelope, with

Mitochondria are organelles found in all but one eukaryote, and are commonly referred to as "the powerhouse of the cell". Mitochondria provide energy to the eukaryote cell by oxidising sugars or fats and releasing energy as

Mitochondria are organelles found in all but one eukaryote, and are commonly referred to as "the powerhouse of the cell". Mitochondria provide energy to the eukaryote cell by oxidising sugars or fats and releasing energy as

Many eukaryotes have long slender motile cytoplasmic projections, called flagella, or similar structures called cilia. Flagella and cilia are sometimes referred to as undulipodia, and are variously involved in movement, feeding, and sensation. They are composed mainly of tubulin. These are entirely distinct from prokaryotic flagellae. They are supported by a bundle of microtubules arising from a centriole, characteristically arranged as nine doublets surrounding two singlets. Flagella also may have hairs, or mastigonemes, and scales connecting membranes and internal rods. Their interior is continuous with the cell's

Many eukaryotes have long slender motile cytoplasmic projections, called flagella, or similar structures called cilia. Flagella and cilia are sometimes referred to as undulipodia, and are variously involved in movement, feeding, and sensation. They are composed mainly of tubulin. These are entirely distinct from prokaryotic flagellae. They are supported by a bundle of microtubules arising from a centriole, characteristically arranged as nine doublets surrounding two singlets. Flagella also may have hairs, or mastigonemes, and scales connecting membranes and internal rods. Their interior is continuous with the cell's

All animals are eukaryotic. Animal cells are distinct from those of other eukaryotes, most notably plants, as they lack

All animals are eukaryotic. Animal cells are distinct from those of other eukaryotes, most notably plants, as they lack

The cells of

The cells of

In

In

The origin of the eukaryotic cell, also known as eukaryogenesis, is a milestone in the evolution of life, since eukaryotes include all complex cells and almost all multicellular organisms. A number of approaches have been used to find the first eukaryote and their closest relatives. The last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) is the hypothetical

The origin of the eukaryotic cell, also known as eukaryogenesis, is a milestone in the evolution of life, since eukaryotes include all complex cells and almost all multicellular organisms. A number of approaches have been used to find the first eukaryote and their closest relatives. The last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) is the hypothetical

Alternative proposals include:

* The chronocyte hypothesis postulates that a primitive eukaryotic cell was formed by the endosymbiosis of both archaea and bacteria by a third type of cell, termed a chronocyte. This is mainly to account for the fact that eukaryotic signature proteins were not found anywhere else by 2002.

* The universal common ancestor (UCA) of the current tree of life was a complex organism that survived a mass extinction event rather than an early stage in the evolution of life. Eukaryotes and in particular akaryotes (Bacteria and Archaea) evolved through reductive loss, so that similarities result from differential retention of original features.

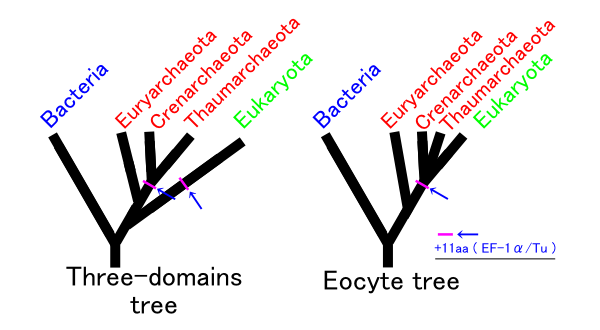

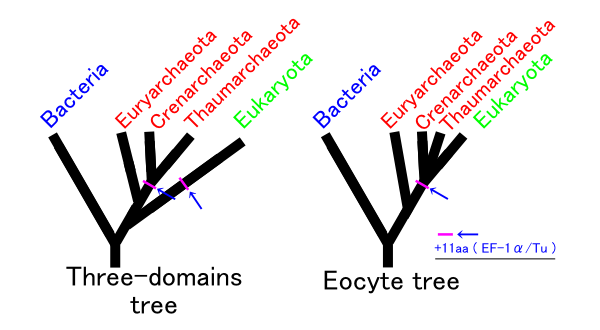

Assuming no other group is involved, there are three possible phylogenies for the Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryota in which each is monophyletic. These are labelled 1 to 3 in the table below, with a modification of hypothesis 2 making the 4th column: The ''eocyte hypothesis'', in which the Archaea are paraphyletic. (The table and the names for the hypotheses are based on Harish & Kurland, 2017.)

In recent years, most researchers have favoured either the three domains (3D) or the eocyte hypothesis. An

Alternative proposals include:

* The chronocyte hypothesis postulates that a primitive eukaryotic cell was formed by the endosymbiosis of both archaea and bacteria by a third type of cell, termed a chronocyte. This is mainly to account for the fact that eukaryotic signature proteins were not found anywhere else by 2002.

* The universal common ancestor (UCA) of the current tree of life was a complex organism that survived a mass extinction event rather than an early stage in the evolution of life. Eukaryotes and in particular akaryotes (Bacteria and Archaea) evolved through reductive loss, so that similarities result from differential retention of original features.

Assuming no other group is involved, there are three possible phylogenies for the Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryota in which each is monophyletic. These are labelled 1 to 3 in the table below, with a modification of hypothesis 2 making the 4th column: The ''eocyte hypothesis'', in which the Archaea are paraphyletic. (The table and the names for the hypotheses are based on Harish & Kurland, 2017.)

In recent years, most researchers have favoured either the three domains (3D) or the eocyte hypothesis. An

"Eukaryotes"

( Tree of Life Web Project) *

Attraction and sex among our microbial Last Eukaryotic Common Ancestors

The Atlantic, November 11, 2020 {{Authority control Articles containing video clips

organism

In biology, an organism () is any life, living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy (biology), taxonomy into groups such as Multicellular o ...

s whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

and Archaea (both prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Con ...

s) make up the other two domains.

The eukaryotes are usually now regarded as having emerged in the Archaea or as a sister of the Asgard archaea. This implies that there are only two domains of life, Bacteria and Archaea, with eukaryotes incorporated among archaea. Eukaryotes represent a small minority of the number of organisms, but, due to their generally much larger size, their collective global biomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms biom ...

is estimated to be about equal to that of prokaryotes. Eukaryotes emerged approximately 2.3–1.8 billion years ago, during the Proterozoic

The Proterozoic () is a geological eon spanning the time interval from 2500 to 538.8million years ago. It is the most recent part of the Precambrian "supereon". It is also the longest eon of the Earth's geologic time scale, and it is subdivided ...

eon, likely as flagellated phagotrophs. Their name comes from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

εὖ (''eu'', "well" or "good") and κάρυον (''karyon'', "nut" or "kernel").

Eukaryotic cells typically contain other membrane-bound organelles such as mitochondria and Golgi apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (), also known as the Golgi complex, Golgi body, or simply the Golgi, is an organelle found in most eukaryotic cells. Part of the endomembrane system in the cytoplasm, it packages proteins into membrane-bound vesicles ...

. Chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it ...

s can be found in plant

Plants are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all curr ...

s and algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) are any of a large and diverse group of photosynthetic, eukaryotic organisms. The name is an informal term for a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from ...

. Prokaryotic cells may contain primitive organelles. Eukaryotes may be either unicellular or multicellular, and include many cell types forming different kinds of tissue. In comparison, prokaryotes are typically unicellular. Animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

s, plant

Plants are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all curr ...

s, and fungi

A fungus (plural, : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of Eukaryote, eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and Mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified ...

are the most familiar eukaryotes. Other eukaryotes are sometimes called protists.

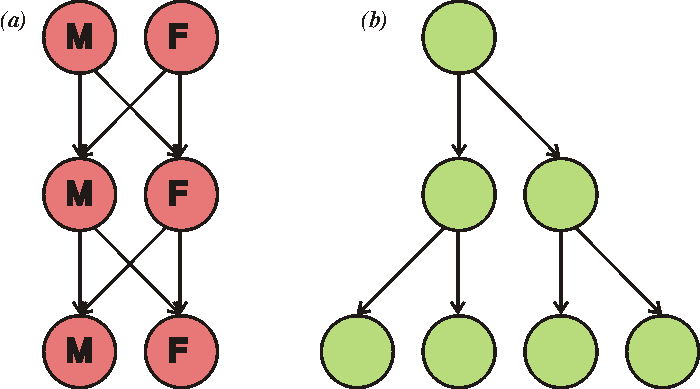

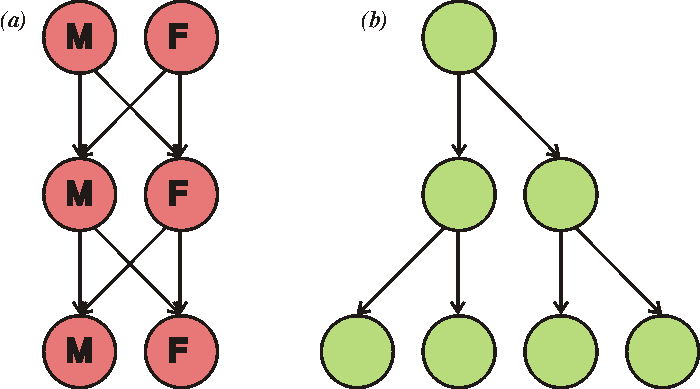

Eukaryotes can reproduce both asexually through mitosis and sexually through meiosis

Meiosis (; , since it is a reductional division) is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately ...

and gamete

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce ...

fusion. In mitosis, one cell divides to produce two genetically identical cells. In meiosis, DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inherita ...

is followed by two rounds of cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukaryotes, there ar ...

to produce four haploid daughter cells that act as sex cells or gametes. Each gamete has just one set of chromosomes, each a unique mix of the corresponding pair of parental chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins ar ...

s resulting from genetic recombination

Genetic recombination (also known as genetic reshuffling) is the exchange of genetic material between different organisms which leads to production of offspring with combinations of traits that differ from those found in either parent. In eukary ...

during meiosis.

Cell features

Eukaryotic cells are typically much larger than those ofprokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Con ...

s, having a volume of around 10,000 times greater than the prokaryotic cell. They have a variety of internal membrane-bound structures, called organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' t ...

s, and a cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is comp ...

composed of microtubules, microfilaments, and intermediate filaments, which play an important role in defining the cell's organization and shape. Eukaryotic DNA is divided into several linear bundles called chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins ar ...

s, which are separated by a microtubular spindle during nuclear division.

Internal membranes

nuclear pore

A nuclear pore is a part of a large complex of proteins, known as a nuclear pore complex that spans the nuclear envelope, which is the double membrane surrounding the eukaryotic cell nucleus. There are approximately 1,000 nuclear pore complex ...

s that allow material to move in and out. Various tube- and sheet-like extensions of the nuclear membrane form the endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

, which is involved in protein transport and maturation. It includes the rough endoplasmic reticulum where ribosomes are attached to synthesize proteins, which enter the interior space or lumen. Subsequently, they generally enter vesicles, which bud off from the smooth endoplasmic reticulum. In most eukaryotes, these protein-carrying vesicles are released and further modified in stacks of flattened vesicles ( cisternae), the Golgi apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (), also known as the Golgi complex, Golgi body, or simply the Golgi, is an organelle found in most eukaryotic cells. Part of the endomembrane system in the cytoplasm, it packages proteins into membrane-bound vesicles ...

.

Vesicles may be specialized for various purposes. For instance, lysosomes contain digestive enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecule ...

s that break down most biomolecules in the cytoplasm. Peroxisome

A peroxisome () is a membrane-bound organelle, a type of microbody, found in the cytoplasm of virtually all eukaryotic cells. Peroxisomes are oxidative organelles. Frequently, molecular oxygen serves as a co-substrate, from which hydrogen ...

s are used to break down peroxide, which is otherwise toxic. Many protozoans have contractile vacuoles, which collect and expel excess water, and extrusomes, which expel material used to deflect predators or capture prey. In higher plants, most of a cell's volume is taken up by a central vacuole, which mostly contains water and primarily maintains its osmotic pressure.

Mitochondria

ATP

ATP may refer to:

Companies and organizations

* Association of Tennis Professionals, men's professional tennis governing body

* American Technical Publishers, employee-owned publishing company

* ', a Danish pension

* Armenia Tree Project, non ...

. They have two surrounding membranes, each a phospholipid bi-layer; the inner of which is folded into invaginations called cristae where aerobic respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be des ...

takes place.

The outer mitochondrial membrane is freely permeable and allows almost anything to enter into the intermembrane space while the inner mitochondrial membrane is semi permeable so allows only some required things into the mitochondrial matrix.

Mitochondria contain their own DNA, which has close structural similarities to bacterial DNA, and which encodes rRNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from riboso ...

and tRNA genes that produce RNA which is closer in structure to bacterial RNA than to eukaryote RNA. They are now generally held to have developed from endosymbiotic prokaryotes, probably Alphaproteobacteria.

Some eukaryotes, such as the metamonads such as '' Giardia'' and '' Trichomonas'', and the amoebozoan '' Pelomyxa'', appear to lack mitochondria, but all have been found to contain mitochondrion-derived organelles, such as hydrogenosomes and mitosome

A mitosome is an organelle found in some unicellular eukaryotic organisms, like in members of the supergroup Excavata. The mitosome was found and named in 1999, and its function has not yet been well characterized. It was termed a ''crypton'' by ...

s, and thus have lost their mitochondria secondarily. They obtain energy by enzymatic action on nutrients absorbed from the environment. The metamonad ''Monocercomonoides

''Monocercomonoides'' is a genus of flagellate Excavata belonging to the order Oxymonadida. It was established by Bernard V. Travis and was first described as those with "polymastiginid flagellates having three anterior flagella and a traili ...

'' has also acquired, by lateral gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). H ...

, a cytosolic sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formul ...

mobilisation system which provides the clusters of iron and sulfur required for protein synthesis. The normal mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster pathway has been lost secondarily.

Plastids

Plants and various groups ofalgae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) are any of a large and diverse group of photosynthetic, eukaryotic organisms. The name is an informal term for a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from ...

also have plastids. Plastids also have their own DNA and are developed from endosymbionts

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" ...

, in this case cyanobacteria. They usually take the form of chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it ...

s which, like cyanobacteria, contain chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to ...

and produce organic compounds (such as glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, usi ...

) through photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored i ...

. Others are involved in storing food. Although plastids probably had a single origin, not all plastid-containing groups are closely related. Instead, some eukaryotes have obtained them from others through secondary endosymbiosis or ingestion. The capture and sequestering of photosynthetic cells and chloroplasts occurs in many types of modern eukaryotic organisms and is known as kleptoplasty.

Endosymbiotic origins have also been proposed for the nucleus, and for eukaryotic flagella.

Cytoskeletal structures

Many eukaryotes have long slender motile cytoplasmic projections, called flagella, or similar structures called cilia. Flagella and cilia are sometimes referred to as undulipodia, and are variously involved in movement, feeding, and sensation. They are composed mainly of tubulin. These are entirely distinct from prokaryotic flagellae. They are supported by a bundle of microtubules arising from a centriole, characteristically arranged as nine doublets surrounding two singlets. Flagella also may have hairs, or mastigonemes, and scales connecting membranes and internal rods. Their interior is continuous with the cell's

Many eukaryotes have long slender motile cytoplasmic projections, called flagella, or similar structures called cilia. Flagella and cilia are sometimes referred to as undulipodia, and are variously involved in movement, feeding, and sensation. They are composed mainly of tubulin. These are entirely distinct from prokaryotic flagellae. They are supported by a bundle of microtubules arising from a centriole, characteristically arranged as nine doublets surrounding two singlets. Flagella also may have hairs, or mastigonemes, and scales connecting membranes and internal rods. Their interior is continuous with the cell's cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. ...

.

Microfilamental structures composed of actin

Actin is a protein family, family of Globular protein, globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in myofibril, muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all Eukaryote, eukaryotic cel ...

and actin binding proteins, e.g., α- actinin, fimbrin, filamin are present in submembranous cortical layers and bundles, as well. Motor proteins of microtubules, e.g., dynein or kinesin and actin, e.g., myosins provide dynamic character of the network.

Centrioles are often present even in cells and groups that do not have flagella, but conifer

Conifers are a group of cone-bearing seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single extant class, Pinopsida. All ex ...

s and flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. They include all forbs (flowering plants without a woody stem), grasses and grass-like plants, a vast majority of ...

s have neither. They generally occur in groups that give rise to various microtubular roots. These form a primary component of the cytoskeletal structure, and are often assembled over the course of several cell divisions, with one flagellum retained from the parent and the other derived from it. Centrioles produce the spindle during nuclear division.

The significance of cytoskeletal structures is underlined in the determination of shape of the cells, as well as their being essential components of migratory responses like chemotaxis and chemokinesis. Some protists have various other microtubule-supported organelles. These include the radiolaria and heliozoa, which produce axopodia

A pseudopod or pseudopodium (plural: pseudopods or pseudopodia) is a temporary arm-like projection of a eukaryotic cell membrane that is emerged in the direction of movement. Filled with cytoplasm, pseudopodia primarily consist of actin filament ...

used in flotation or to capture prey, and the haptophytes, which have a peculiar flagellum-like organelle called the haptonema.

Cell wall

The cells of plants and algae, fungi and mostchromalveolates

Chromista is a biological kingdom consisting of single-celled and multicellular eukaryotic species that share similar features in their photosynthetic organelles (plastids). It includes all protists whose plastids contain chlorophyll ''c'', such ...

have a cell wall, a layer outside the cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment (the ...

, providing the cell with structural support, protection, and a filtering mechanism. The cell wall also prevents over-expansion when water enters the cell.

The major polysaccharides

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with w ...

making up the primary cell wall of land plants are cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wall ...

, hemicellulose, and pectin

Pectin ( grc, πηκτικός ': "congealed" and "curdled") is a heteropolysaccharide, a structural acid contained in the primary lamella, in the middle lamella, and in the cell walls of terrestrial plants. The principal, chemical component o ...

. The cellulose microfibrils are linked via hemicellulosic tethers to form the cellulose-hemicellulose network, which is embedded in the pectin matrix. The most common hemicellulose in the primary cell wall is xyloglucan.

Differences among eukaryotic cells

There are many different types of eukaryotic cells, though animals and plants are the most familiar eukaryotes, and thus provide an excellent starting point for understanding eukaryotic structure. Fungi and many protists have some substantial differences, however.Animal cell

cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mec ...

s and chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it ...

s and have smaller vacuoles. Due to the lack of a cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mec ...

, animal cells can transform into a variety of shapes. A phagocytic cell can even engulf other structures.

Plant cell

Plant cells have a number of features that distinguish them from the cells of the other eukaryotic organisms. These include: * A large central vacuole (enclosed by a membrane, the tonoplast), which maintains the cell's turgor and controls movement ofmolecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bio ...

s between the cytosol and sap

* A primary cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mec ...

containing cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wall ...

, hemicellulose and pectin

Pectin ( grc, πηκτικός ': "congealed" and "curdled") is a heteropolysaccharide, a structural acid contained in the primary lamella, in the middle lamella, and in the cell walls of terrestrial plants. The principal, chemical component o ...

, deposited by the protoplast on the outside of the cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment (the ...

; this contrasts with the cell walls of fungi

A fungus (plural, : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of Eukaryote, eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and Mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified ...

, which contain chitin

Chitin ( C8 H13 O5 N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is probably the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cellulose); an estimated 1 billion tons of chit ...

, and the cell envelopes of prokaryotes, in which peptidoglycans are the main structural molecules

* The plasmodesmata, pores in the cell wall that link adjacent cells and allow plant cells to communicate with adjacent cells. Animals have a different but functionally analogous system of gap junctions between adjacent cells.

* Plastids, especially chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it ...

s, organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' t ...

s that contain chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to ...

, the pigment that gives plant

Plants are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all curr ...

s their green color and allows them to perform photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored i ...

* Bryophyte

The Bryophyta s.l. are a proposed taxonomic division containing three groups of non-vascular land plants ( embryophytes): the liverworts, hornworts and mosses. Bryophyta s.s. consists of the mosses only. They are characteristically limited ...

s and seedless vascular plants only have flagellae and centrioles in the sperm cells. Sperm of cycads and '' Ginkgo'' are large, complex cells that swim with hundreds to thousands of flagellae.

* Conifers (Pinophyta) and flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. They include all forbs (flowering plants without a woody stem), grasses and grass-like plants, a vast majority of ...

s (Angiospermae) lack the flagellae and centrioles that are present in animal cells.

Fungal cell

The cells of

The cells of fungi

A fungus (plural, : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of Eukaryote, eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and Mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified ...

are similar to animal cells, with the following exceptions:

* A cell wall that contains chitin

Chitin ( C8 H13 O5 N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is probably the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cellulose); an estimated 1 billion tons of chit ...

* Less compartmentation between cells; the hypha

A hypha (; ) is a long, branching, filamentous structure of a fungus, oomycete, or actinobacterium. In most fungi, hyphae are the main mode of vegetative growth, and are collectively called a mycelium.

Structure

A hypha consists of one o ...

e of higher fungi have porous partitions called septa, which allow the passage of cytoplasm, organelles, and, sometimes, nuclei; so each organism is essentially a giant multinucleate

Multinucleate cells (also known as multinucleated or polynuclear cells) are eukaryotic cells that have more than one nucleus per cell, i.e., multiple nuclei share one common cytoplasm. Mitosis in multinucleate cells can occur either in a coord ...

supercell – these fungi are described as coenocytic

A coenocyte () is a multinucleate cell which can result from multiple nuclear divisions without their accompanying cytokinesis, in contrast to a syncytium, which results from cellular aggregation followed by dissolution of the cell membranes insid ...

. Primitive fungi have few or no septa.

* Only the most primitive fungi, chytrid

Chytridiomycota are a division of zoosporic organisms in the kingdom Fungi, informally known as chytrids. The name is derived from the Ancient Greek ('), meaning "little pot", describing the structure containing unreleased zoöspores. Chytri ...

s, have flagella.

Other eukaryotic cells

Some groups of eukaryotes have unique organelles, such as the cyanelles (unusual plastids) of the glaucophytes, the haptonema of the haptophytes, or the ejectosomes of the cryptomonads. Other structures, such as pseudopodia, are found in various eukaryote groups in different forms, such as the lobose amoebozoans or the reticulose foraminiferans. Structures known as cortical alveoli are vesicles present under the cell membrane of many protists such asdinoflagellate

The dinoflagellates (Greek δῖνος ''dinos'' "whirling" and Latin ''flagellum'' "whip, scourge") are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered algae. Dinoflagellates are ...

s, ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a differen ...

s and apicomplexan

The Apicomplexa (also called Apicomplexia) are a large phylum of parasitic alveolates. Most of them possess a unique form of organelle that comprises a type of non-photosynthetic plastid called an apicoplast, and an apical complex structure. The ...

parasites.

Reproduction

Cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukaryotes, there ar ...

generally takes place asexually by mitosis, a process that allows each daughter nucleus to receive one copy of each chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins ar ...

. Most eukaryotes also have a life cycle that involves sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote th ...

, alternating

Alternating may refer to:

Mathematics

* Alternating algebra, an algebra in which odd-grade elements square to zero

* Alternating form, a function formula in algebra

* Alternating group, the group of even permutations of a finite set

* Alter ...

between a haploid phase, where only one copy of each chromosome is present in each cell and a diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respecti ...

phase, wherein two copies of each chromosome are present in each cell. The diploid phase is formed by fusion of two haploid gametes to form a zygote, which may divide by mitosis or undergo chromosome reduction by meiosis

Meiosis (; , since it is a reductional division) is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately ...

. There is considerable variation in this pattern. Animals have no multicellular haploid phase, but each plant generation can consist of haploid and diploid multicellular phases.

Eukaryotes have a smaller surface area to volume ratio than prokaryotes, and thus have lower metabolic rates and longer generation times.

The evolution of sexual reproduction may be a primordial and fundamental characteristic of eukaryotes. Based on a phylogenetic analysis, Dacks and Roger

Roger is a given name, usually masculine, and a surname. The given name is derived from the Old French personal names ' and '. These names are of Germanic origin, derived from the elements ', ''χrōþi'' ("fame", "renown", "honour") and ', ' ...

proposed that facultative sex was present in the common ancestor of all eukaryotes. A core set of genes that function in meiosis is present in both '' Trichomonas vaginalis'' and '' Giardia intestinalis'', two organisms previously thought to be asexual. Since these two species are descendants of lineages that diverged early from the eukaryotic evolutionary tree, it was inferred that core meiotic genes, and hence sex, were likely present in a common ancestor of all eukaryotes. Eukaryotic species once thought to be asexual, such as parasitic protozoa of the genus '' Leishmania'', have been shown to have a sexual cycle. Also, evidence now indicates that amoebae, previously regarded as asexual, are anciently sexual and that the majority of present-day asexual groups likely arose recently and independently.

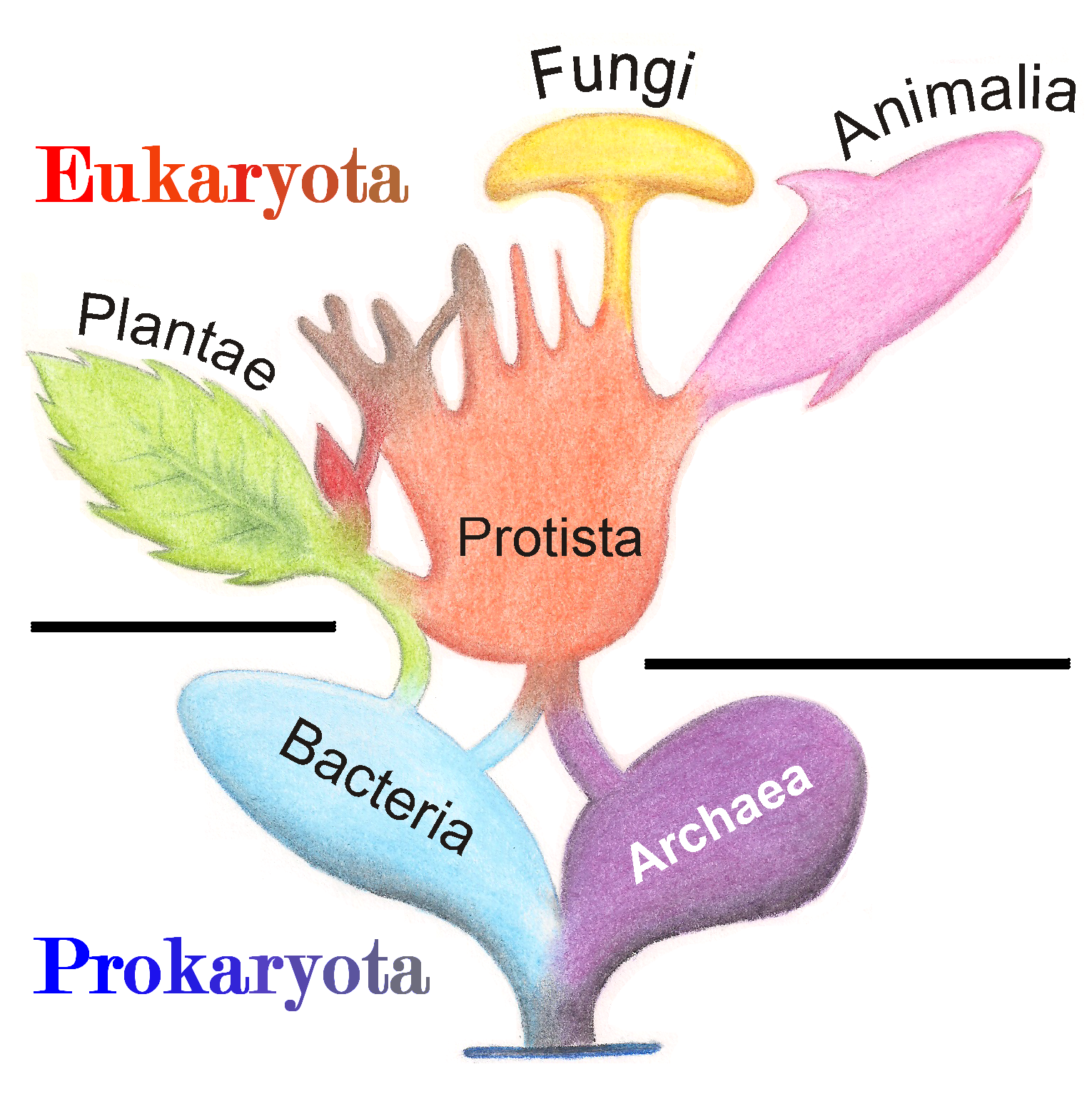

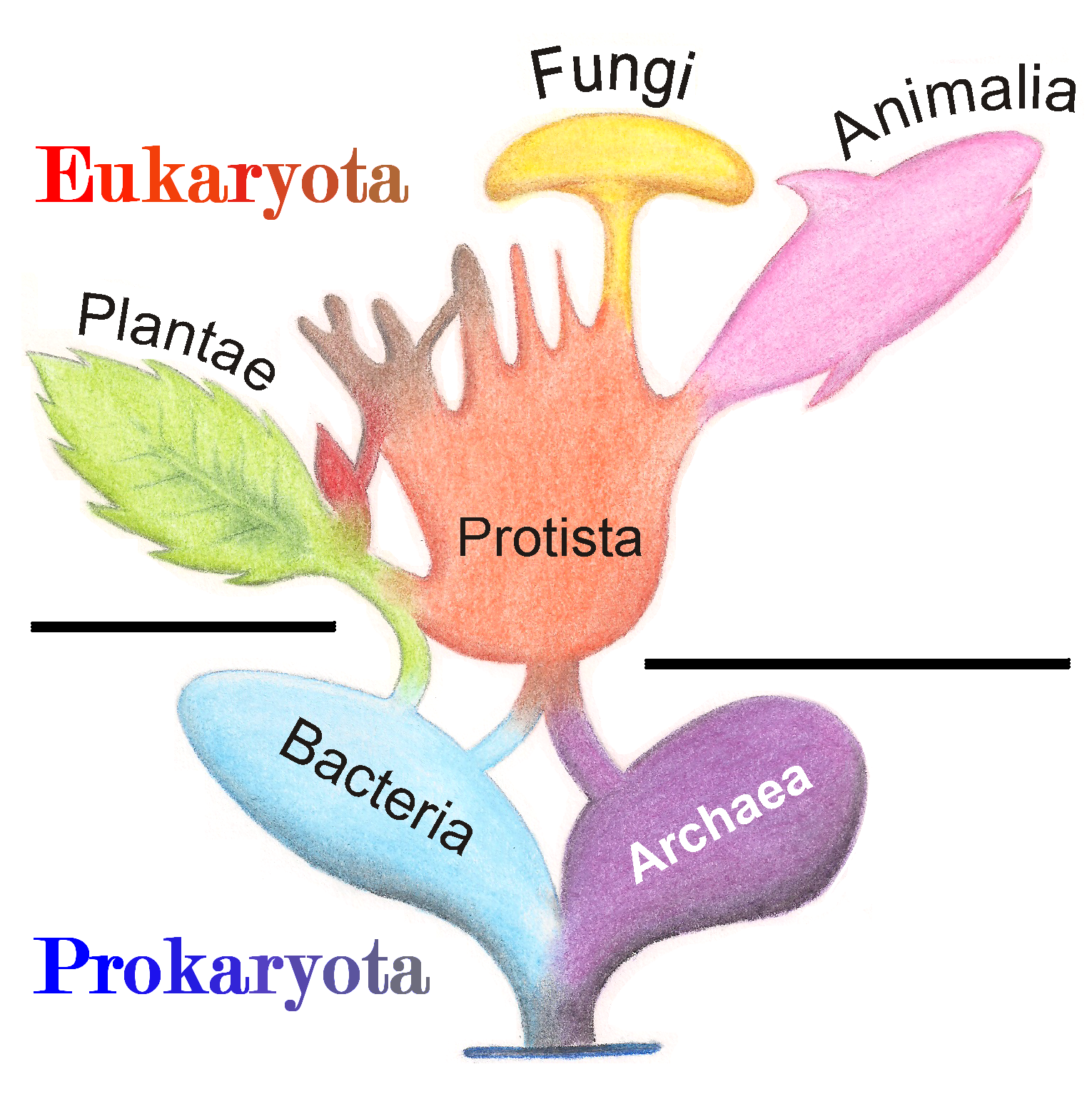

Classification

In

In antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

, the two lineages of animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

s and plant

Plants are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all curr ...

s were recognized. They were given the taxonomic rank of Kingdom by Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, t ...

. Though he included the fungi

A fungus (plural, : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of Eukaryote, eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and Mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified ...

with plants with some reservations, it was later realized that they are quite distinct and warrant a separate kingdom, the composition of which was not entirely clear until the 1980s. The various single-cell eukaryotes were originally placed with plants or animals when they became known. In 1818, the German biologist Georg A. Goldfuss coined the word '' protozoa'' to refer to organisms such as ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a differen ...

s, and this group was expanded until it encompassed all single-celled eukaryotes, and given their own kingdom, the Protista, by Ernst Haeckel in 1866. The eukaryotes thus came to be composed of four kingdoms:

* Kingdom Protista

* Kingdom Plantae

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

* Kingdom Fungi

A fungus (plural, : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of Eukaryote, eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and Mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified ...

* Kingdom Animalia

The protists were understood to be "primitive forms", and thus an evolutionary grade, united by their primitive unicellular nature. The disentanglement of the deep splits in the tree of life

The tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world's mythological, religious, and philosophical traditions. It is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree.Giovino, Mariana (2007). ''The Assyrian Sacred Tree: A Histo ...

only really started with DNA sequencing, leading to a system of domains rather than kingdoms as top level rank being put forward by Carl Woese, uniting all the eukaryote kingdoms under the eukaryote domain. At the same time, work on the protist tree intensified, and is still actively going on today. Several alternative classifications have been forwarded, though there is no consensus in the field.

Eukaryotes are a clade usually assessed to be sister to Heimdallarchaeota in the Asgard grouping in the Archaea. In one proposed system, the basal groupings are the Opimoda, Diphoda, the Discoba, and the Loukozoa. The Eukaryote root is usually assessed to be near or even in Discoba.

A classification produced in 2005 for the International Society of Protistologists, which reflected the consensus of the time, divided the eukaryotes into six supposedly monophyletic ' supergroups'. However, in the same year (2005), doubts were expressed as to whether some of these supergroups were monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic ...

, particularly the Chromalveolata, and a review in 2006 noted the lack of evidence for several of the supposed six supergroups. A revised classification in 2012 recognizes five supergroups.

There are also smaller groups of eukaryotes whose position is uncertain or seems to fall outside the major groups – in particular, Haptophyta, Cryptophyta, Centrohelida, Telonemia, Picozoa, Apusomonadida

The Apusomonadida are a group of protozoan zooflagellates that glide on surfaces, and mostly consume prokaryotes. They are of particular evolutionary interest because they appear to be the sister group to the Opisthokonts, the clade that includ ...

, Ancyromonadida, Breviatea, and the genus '' Collodictyon''. Overall, it seems that, although progress has been made, there are still very significant uncertainties in the evolutionary history and classification of eukaryotes. As Roger

Roger is a given name, usually masculine, and a surname. The given name is derived from the Old French personal names ' and '. These names are of Germanic origin, derived from the elements ', ''χrōþi'' ("fame", "renown", "honour") and ', ' ...

& Simpson said in 2009 "with the current pace of change in our understanding of the eukaryote tree of life, we should proceed with caution." Newly identified protists, purported to represent novel, deep-branching lineages, continue to be described well into the 21st century; recent examples including '' Rhodelphis'', putative sister group to Rhodophyta, and '' Anaeramoeba'', anaerobic amoebaflagellates of uncertain placement.

Phylogeny

TherRNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from riboso ...

trees constructed during the 1980s and 1990s left most eukaryotes in an unresolved "crown" group (not technically a true crown), which was usually divided by the form of the mitochondrial cristae; see crown eukaryotes. The few groups that lack mitochondria branched separately, and so the absence was believed to be primitive; but this is now considered an artifact of long-branch attraction, and they are known to have lost them secondarily.

It has been estimated that there may be 75 distinct lineages of eukaryotes. Most of these lineages are protists.

The known eukaryote genome sizes vary from 8.2 megabases (Mb) in '' Babesia bovis'' to 112,000–220,050 Mb in the dinoflagellate '' Prorocentrum micans'', showing that the genome of the ancestral eukaryote has undergone considerable variation during its evolution. The last common ancestor of all eukaryotes is believed to have been a phagotrophic protist with a nucleus, at least one centriole and cilium, facultatively aerobic mitochondria, sex (meiosis

Meiosis (; , since it is a reductional division) is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately ...

and syngamy), a dormant cyst with a cell wall of chitin

Chitin ( C8 H13 O5 N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is probably the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cellulose); an estimated 1 billion tons of chit ...

and/or cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wall ...

and peroxisome

A peroxisome () is a membrane-bound organelle, a type of microbody, found in the cytoplasm of virtually all eukaryotic cells. Peroxisomes are oxidative organelles. Frequently, molecular oxygen serves as a co-substrate, from which hydrogen ...

s. Later endosymbiosis led to the spread of plastids in some lineages.

Although there is still considerable uncertainty in global eukaryote phylogeny, particularly regarding the position of the root, a rough consensus has started to emerge from the phylogenomic studies of the past two decades. The majority of eukaryotes can be placed in one of two large clades dubbed Amorphea

Amorphea are members of a taxonomic supergroup that includes the basal Amoebozoa and Obazoa. That latter contains the Opisthokonta, which includes the Fungi, Animals and the Choanomonada, or Choanoflagellates. The taxonomic affinities of the me ...

(similar in composition to the unikont hypothesis) and the Diaphoretickes, which includes plants and most algal lineages. A third major grouping, the Excavata, has been abandoned as a formal group in the most recent classification of the International Society of Protistologists due to growing uncertainty as to whether its constituent groups belong together. The proposed phylogeny below includes only one group of excavates ( Discoba), and incorporates the recent proposal that picozoans are close relatives of rhodophytes.

In some analyses, the Hacrobia group ( Haptophyta + Cryptophyta) is placed next to Archaeplastida, but in others it is nested inside the Archaeplastida. However, several recent studies have concluded that Haptophyta and Cryptophyta do not form a monophyletic group. The former could be a sister group to the SAR group, the latter cluster with the Archaeplastida (plants in the broad sense).

The division of the eukaryotes into two primary clades, bikonts ( Archaeplastida + SAR + Excavata) and unikonts ( Amoebozoa + Opisthokonta), derived from an ancestral biflagellar organism and an ancestral uniflagellar organism, respectively, had been suggested earlier. A 2012 study produced a somewhat similar division, although noting that the terms "unikonts" and "bikonts" were not used in the original sense.

A highly converged and congruent set of trees appears in Derelle et al. (2015), Ren et al. (2016), Yang et al. (2017) and Cavalier-Smith (2015) including the supplementary information, resulting in a more conservative and consolidated tree. It is combined with some results from Cavalier-Smith for the basal Opimoda. The main remaining controversies are the root, and the exact positioning of the Rhodophyta and the bikonts Rhizaria, Haptista, Cryptista, Picozoa and Telonemia, many of which may be endosymbiotic eukaryote-eukaryote hybrids. Archaeplastida acquired chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it ...

s probably by endosymbiosis of a prokaryotic ancestor related to a currently extant cyanobacterium, '' Gloeomargarita lithophora''.

Cavalier-Smith's tree

Thomas Cavalier-Smith 2010, 2013, 2014, 2017 and 2018 places the eukaryotic tree's root between Excavata (with ventral feeding groove supported by a microtubular root) and the grooveless Euglenozoa, and monophyletic Chromista, correlated to a single endosymbiotic event of capturing a red-algae. He et al. specifically supports rooting the eukaryotic tree between a monophyletic Discoba ( Discicristata + Jakobida) and anAmorphea

Amorphea are members of a taxonomic supergroup that includes the basal Amoebozoa and Obazoa. That latter contains the Opisthokonta, which includes the Fungi, Animals and the Choanomonada, or Choanoflagellates. The taxonomic affinities of the me ...

- Diaphoretickes clade.

Evolutionary history

Origin of eukaryotes

The origin of the eukaryotic cell, also known as eukaryogenesis, is a milestone in the evolution of life, since eukaryotes include all complex cells and almost all multicellular organisms. A number of approaches have been used to find the first eukaryote and their closest relatives. The last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) is the hypothetical

The origin of the eukaryotic cell, also known as eukaryogenesis, is a milestone in the evolution of life, since eukaryotes include all complex cells and almost all multicellular organisms. A number of approaches have been used to find the first eukaryote and their closest relatives. The last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) is the hypothetical last common ancestor

In biology and genetic genealogy, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as the last common ancestor (LCA) or concestor, of a set of organisms is the most recent individual from which all the organisms of the set are descended. The ...

of all living eukaryotes, and was most likely a biological population.

Eukaryotes have a number of features that differentiate them from prokaryotes, including an endomembrane system, and unique biochemical pathways such as sterane synthesis. A set of proteins called eukaryotic signature proteins (ESPs) was proposed to identify eukaryotic relatives in 2002: They have no homology to proteins known in other domains of life by then, but they appear to be universal among eukaryotes. They include proteins that make up the cytoskeleton, the complex transcription machinery, membrane-sorting systems, the nuclear pore, as well as some enzymes in the biochemical pathways.

Fossils

The timing of this series of events is hard to determine; Knoll (2006) suggests they developed approximately 1.6–2.1 billion years ago. Some acritarchs are known from at least 1.65 billion years ago, and the possible alga '' Grypania'' has been found as far back as 2.1 billion years ago. The '' Geosiphon''-like fossilfungus

A fungus (plural, : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of Eukaryote, eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and Mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified ...

'' Diskagma'' has been found in paleosols 2.2 billion years old.

Organized living structures have been found in the black shales of the Palaeoproterozoic Francevillian B Formation in Gabon, dated at 2.1 billion years old. Eukaryotic life could have evolved at that time. Fossils that are clearly related to modern groups start appearing an estimated 1.2 billion years ago, in the form of a red algae, though recent work suggests the existence of fossilized filamentous algae in the Vindhya basin dating back perhaps to 1.6 to 1.7 billion years ago.

The presence of eukaryotic-specific biomarkers ( steranes) in Australian shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especia ...

s previously indicated that eukaryotes were present in these rocks dated at 2.7 billion years old, which was even 300 million years older than the first geological records of the appreciable amount of molecular oxygen during the Great Oxidation Event. However, these Archaean biomarkers were eventually rebutted as later contaminants. Currently, putatively the oldest biomarker records are only ~800 million years old. In contrast, a molecular clock analysis suggests the emergence of sterol biosynthesis as early as 2.3 billion years ago, and thus there is a huge gap between molecular data and geological data, which hinders a reasonable inference of the eukaryotic evolution through biomarker records before 800 million years ago. The nature of steranes as eukaryotic biomarkers is further complicated by the production of sterols by some bacteria.

Whenever their origins, eukaryotes may not have become ecologically dominant until much later; a massive uptick in the zinc composition of marine sediments has been attributed to the rise of substantial populations of eukaryotes, which preferentially consume and incorporate zinc relative to prokaryotes, approximately a billion years after their origin (at the latest).

In April 2019, biologists reported that the very large medusavirus, or a relative, may have been responsible, at least in part, for the evolutionary emergence of complex eukaryotic cells from simpler prokaryotic cells.

*

Relationship to Archaea

The nuclear DNA and genetic machinery of eukaryotes is more similar to Archaea thanBacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

, leading to a controversial suggestion that eukaryotes should be grouped with Archaea in the clade Neomura. In other respects, such as membrane composition, eukaryotes are similar to Bacteria. Three main explanations for this have been proposed:

* Eukaryotes resulted from the complete fusion of two or more cells, wherein the cytoplasm formed from a bacterium

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were a ...

, and the nucleus from an archaeon, from a virus, or from a pre-cell.

* Eukaryotes developed from Archaea, and acquired their bacterial characteristics through the endosymbiosis

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "withi ...

of a proto-mitochondrion of bacterial origin.

* Eukaryotes and Archaea developed separately from a modified bacterium.

rRNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from riboso ...

analysis supports the eocyte scenario, apparently with the Eukaryote root in Excavata. A cladogram supporting the eocyte hypothesis, positioning eukaryotes within Archaea, based on phylogenomic analyses of the Asgard archaea, is:

In this scenario, the Asgard group is seen as a sister taxon of the TACK group, which comprises Thermoproteota (formerly named eocytes

The Thermoproteota (also known as crenarchaea) are archaea that have been classified as a phylum of the Archaea domain. Initially, the Thermoproteota were thought to be sulfur-dependent extremophiles but recent studies have identified characteris ...

or Crenarchaeota), Nitrososphaerota (formerly Thaumarchaeota), and others. This group is reported contain many of the eukaryotic signature proteins and produce vesicles.

In 2017, there was significant pushback against this scenario, arguing that the eukaryotes did not emerge within the Archaea. Cunha ''et al.'' produced analyses supporting the three domains (3D) or Woese hypothesis (2 in the table above) and rejecting the eocyte hypothesis (4 above). Harish and Kurland found strong support for the earlier two empires (2D) or Mayr hypothesis (1 in the table above), based on analyses of the coding sequences of protein domains. They rejected the eocyte hypothesis as the least likely. A possible interpretation of their analysis is that the universal common ancestor (UCA) of the current tree of life was a complex organism that survived an evolutionary bottleneck, rather than a simpler organism arising early in the history of life. On the other hand, the researchers who came up with Asgard re-affirmed their hypothesis with additional Asgard samples. Since then, the publication of additional Asgard archaeal genomes and the independent reconstruction of phylogenomic trees by multiple independent laboratories have provided additional support for an Asgard archaeal origin of eukaryotes.

Details of the relation of Asgard archaea members and eukaryotes are still under consideration, although, in January 2020, scientists reported that '' Candidatus Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum'', a type of cultured Asgard archaea, may be a possible link between simple prokaryotic and complex eukaryotic microorganisms about two billion years ago.

Endomembrane system and mitochondria

The origins of the endomembrane system and mitochondria are also unclear. The phagotrophic hypothesis proposes that eukaryotic-type membranes lacking a cell wall originated first, with the development of endocytosis, whereas mitochondria were acquired by ingestion as endosymbionts. The syntrophic hypothesis proposes that the proto-eukaryote relied on the proto-mitochondrion for food, and so ultimately grew to surround it. Here the membranes originated after the engulfment of the mitochondrion, in part thanks to mitochondrial genes (the hydrogen hypothesis is one particular version). In a study using genomes to constructsupertree A supertree is a single phylogenetic tree assembled from a combination of smaller phylogenetic trees, which may have been assembled using different datasets (e.g. morphological and molecular) or a different selection of taxa. Supertree algorithms ...

s, Pisani ''et al.'' (2007) suggest that, along with evidence that there was never a mitochondrion-less eukaryote, eukaryotes evolved from a syntrophy between an archaea closely related to Thermoplasmatales and an alphaproteobacterium, likely a symbiosis driven by sulfur or hydrogen. The mitochondrion and its genome is a remnant of the alphaproteobacterial endosymbiont. The majority of the genes from the symbiont have been transferred to the nucleus. They make up most of the metabolic and energy-related pathways of the eukaryotic cell, while the information system (DNA polymerase, transcription, translation) is retained from archaea.

Hypotheses

Different hypotheses have been proposed as to how eukaryotic cells came into existence. These hypotheses can be classified into two distinct classes – autogenous models and chimeric models.=Autogenous models

= Autogenous models propose that a proto-eukaryotic cell containing a nucleus existed first, and later acquired mitochondria. According to this model, a largeprokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Con ...

developed invaginations in its plasma membrane in order to obtain enough surface area

The surface area of a solid object is a measure of the total area that the surface of the object occupies. The mathematical definition of surface area in the presence of curved surfaces is considerably more involved than the definition of ...

to service its cytoplasmic volume. As the invaginations differentiated in function, some became separate compartments – giving rise to the endomembrane system, including the endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

, golgi apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (), also known as the Golgi complex, Golgi body, or simply the Golgi, is an organelle found in most eukaryotic cells. Part of the endomembrane system in the cytoplasm, it packages proteins into membrane-bound vesicles ...

, nuclear membrane, and single membrane structures such as lysosomes.

Mitochondria are proposed to come from the endosymbiosis

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "withi ...

of an aerobic proteobacterium after an eukaryote with a nucleus has evolved. This theory is less held onto because it requires extra assumptions to explain current conditions. For example, as every known eukaryote has a mitochondrion (or at least show signs of having an ancestor that had), one must assumed that all the eukaryotic lineages that did not acquire mitochondria became extinct. The theory also doesn’t explain why anaerobic variants of mitochondria have evolved.

=Chimeric models

= Chimeric models claim that two prokaryotic cells existed initially – an archaeon and abacterium

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were a ...

. The closest living relatives of these appears to be Asgardarchaeota

Asgard or Asgardarchaeota is a proposed superphylum consisting of a group of archaea that includes Lokiarchaeota, Thorarchaeota, Odinarchaeota, and Heimdallarchaeota. It appears the eukaryotes emerged within the Asgard, in a branch containing the ...

and (distantly related) the alphaproteobacteria called the proto-mitochondrion.

* These cells underwent a merging process, either by a physical fusion or by endosymbiosis

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "withi ...

, thereby leading to the formation of a eukaryotic cell. Within these chimeric models, some studies further claim that mitochondria originated from a bacterial ancestor while others emphasize the role of endosymbiotic processes behind the origin of mitochondria.

=The inside-out hypothesis

= The inside-out hypothesis suggests that the fusion between free-living mitochondria-like bacteria, and an archaeon into a eukaryotic cell happened gradually over a long period of time, instead of in a single phagocytotic event. In this scenario, an archaeon would trap aerobic bacteria with cell protrusions, and then keep them alive to draw energy from them instead of digesting them. During the early stages the bacteria would still be partly in direct contact with the environment, and the archaeon would not have to provide them with all the required nutrients. But eventually the archaeon would engulf the bacteria completely, creating the internal membrane structures and nucleus membrane in the process. * It is assumed the archaean group called halophiles went through a similar procedure, where they acquired as much as a thousand genes from a bacterium, way more than through the conventionalhorizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring ( reproduction). ...

that often occurs in the microbial world, but that the two microbes separated again before they had fused into a single eukaryote-like cell.

An expanded version of the inside-out hypothesis proposes that the eukaryotic cell was created by physical interactions between two prokaryotic organisms and that the last common ancestor of eukaryotes got its genome from a whole population or community of microbes participating in cooperative relationships to thrive and survive in their environment. The genome from the various types of microbes would complement each other, and occasional horizontal gene transfer between them would be largely to their own benefit. This accumulation of beneficial genes gave rise to the genome of the eukaryotic cell, which contained all the genes required for independence.

=The serial endosymbiotic hypothesis

= According to serial endosymbiotic theory (championed by Lynn Margulis), a union between a motileanaerobic

Anaerobic means "living, active, occurring, or existing in the absence of free oxygen", as opposed to aerobic which means "living, active, or occurring only in the presence of oxygen." Anaerobic may also refer to:

*Adhesive#Anaerobic, Anaerobic ad ...

bacterium (like ''Spirochaeta'') and a thermoacidophilic crenarchaeon (like ''Thermoplasma'' which is sulfidogenic in nature) gave rise to the present day eukaryotes. This union established a motile organism capable of living in the already existing acidic and sulfurous waters. Oxygen is known to cause toxicity to organisms that lack the required metabolic

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cel ...

machinery. Thus, the archaeon provided the bacterium with a highly beneficial reduced environment (sulfur and sulfate were reduced to sulfide). In microaerophilic conditions, oxygen was reduced to water thereby creating a mutual benefit platform. The bacterium on the other hand, contributed the necessary fermentation products and electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary partic ...

acceptors along with its motility feature to the archaeon thereby gaining a swimming motility

Motility is the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy.

Definitions

Motility, the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy, can be contrasted with sessility, the state of organisms th ...

for the organism.

From a consortium of bacterial and archaeal DNA originated the nuclear genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

of eukaryotic cells. Spirochetes gave rise to the motile features of eukaryotic cells. Endosymbiotic unifications of the ancestors of alphaproteobacteria and cyanobacteria, led to the origin of mitochondria and plastids respectively. For example, ''Thiodendron'' has been known to have originated via an ectosymbiotic process based on a similar syntrophy of sulfur existing between the two types of bacteria – '' Desulfobacter'' and ''Spirochaeta''.

However, such an association based on motile symbiosis has never been observed practically. Also there is no evidence of archaeans and spirochetes adapting to intense acid-based environments. In addition, the theory posits that mitochondrion-less eukaryotes have existed, tying back to the problem in the autogenous model.

=The hydrogen hypothesis

= In the hydrogen hypothesis, the symbiotic linkage of an anaerobic andautotroph

An autotroph or primary producer is an organism that produces complex organic compounds (such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) using carbon from simple substances such as carbon dioxide,Morris, J. et al. (2019). "Biology: How Life Works", ...

ic methanogen

Methanogens are microorganisms that produce methane as a metabolic byproduct in hypoxic conditions. They are prokaryotic and belong to the domain Archaea. All known methanogens are members of the archaeal phylum Euryarchaeota. Methanogens ar ...

ic archaeon (host) with an alphaproteobacterium (the symbiont) gave rise to the eukaryotes. The host used hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

(H2) and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

() to produce methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane on Ear ...

while the symbiont, capable of aerobic respiration, expelled H2 and as byproducts of anaerobic fermentation process. The host's methanogenic environment worked as a sink for H2, which resulted in heightened bacterial fermentation.

Endosymbiotic gene transfer acted as a catalyst for the host to acquire the symbionts' carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may or ...

metabolism and turn heterotrophic in nature. Subsequently, the host's methane forming capability was lost. Thus, the origins of the heterotrophic organelle (symbiont) are identical to the origins of the eukaryotic lineage. In this hypothesis, the presence of H2 represents the selective force that forged eukaryotes out of prokaryotes.

=The syntrophy hypothesis

= The syntrophy hypothesis was developed in contrast to the hydrogen hypothesis and proposes the existence of two symbiotic events. According to this model, the origin of eukaryotic cells was based on metabolic symbiosis (syntrophy) between a methanogenic archaeon and a deltaproteobacterium. This syntrophic symbiosis was initially facilitated by H2 transfer between different species under anaerobic environments. In earlier stages, an alphaproteobacterium became a member of this integration, and later developed into the mitochondrion.Gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

transfer from a deltaproteobacterium to an archaeon led to the methanogenic archaeon developing into a nucleus. The archaeon constituted the genetic apparatus, while the deltaproteobacterium contributed towards the cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. ...

ic features.

This theory incorporates two selective forces at the time of nucleus evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

* presence of metabolic partitioning to avoid the harmful effects of the co-existence of anabolic and catabolic

Catabolism () is the set of metabolic pathways that breaks down molecules into smaller units that are either oxidized to release energy or used in other anabolic reactions. Catabolism breaks down large molecules (such as polysaccharides, lipids ...

cellular pathways, and

* prevention of abnormal protein biosynthesis

Protein biosynthesis (or protein synthesis) is a core biological process, occurring inside cells, balancing the loss of cellular proteins (via degradation or export) through the production of new proteins. Proteins perform a number of critical ...

due to a vast spread of intron

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e. a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gene ...

s in the archaeal genes after acquiring the mitochondrion and losing methanogenesis.

=6+ serial endosymbiosis scenario

= A complex scenario of 6+ serial endosymbiotic events of archaea and bacteria has been proposed in which mitochondria and an asgard related archaeota were acquired at a late stage of eukaryogenesis, possibly in combination, as a secondary endosymbiont. The findings have been rebuked as an artifact.See also