Cyprus (island) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an

The earliest attested reference to ''Cyprus'' is the 15th century BC

The earliest attested reference to ''Cyprus'' is the 15th century BC

Cyprus is at a strategic location in the Middle East. It was ruled by the

Cyprus is at a strategic location in the Middle East. It was ruled by the

/ref> The Kingdoms of Cyprus enjoyed special privileges and a semi-autonomous status, but they were still considered vassal subjects of the Great King. The island was conquered by

When the

When the

In 1570, a full-scale Ottoman assault with 60,000 troops brought the island under Ottoman control, despite stiff resistance by the inhabitants of Nicosia and Famagusta. Ottoman forces capturing Cyprus massacred many Greek and Armenian Christian inhabitants. The previous Latin elite were destroyed and the first significant demographic change since antiquity took place with the formation of a Muslim community. Soldiers who fought in the conquest settled on the island and Turkish peasants and craftsmen were brought to the island from

In 1570, a full-scale Ottoman assault with 60,000 troops brought the island under Ottoman control, despite stiff resistance by the inhabitants of Nicosia and Famagusta. Ottoman forces capturing Cyprus massacred many Greek and Armenian Christian inhabitants. The previous Latin elite were destroyed and the first significant demographic change since antiquity took place with the formation of a Muslim community. Soldiers who fought in the conquest settled on the island and Turkish peasants and craftsmen were brought to the island from  The Ottomans abolished the

The Ottomans abolished the

, ''U.S. Library of Congress'' The ratio of Muslims to Christians fluctuated throughout the period of Ottoman domination. In 1777–78, 47,000 Muslims constituted a majority over the island's 37,000 Christians. By 1872, the population of the island had risen to 144,000, comprising 44,000 Muslims and 100,000 Christians. The Muslim population included numerous

In the aftermath of the

In the aftermath of the  The island would serve Britain as a key military base for its colonial routes. By 1906, when the Famagusta harbour was completed, Cyprus was a strategic naval outpost overlooking the

The island would serve Britain as a key military base for its colonial routes. By 1906, when the Famagusta harbour was completed, Cyprus was a strategic naval outpost overlooking the  Initially, the Turkish Cypriots favoured the continuation of the British rule. However, they were alarmed by the Greek Cypriot calls for ''enosis'', as they saw the union of

Initially, the Turkish Cypriots favoured the continuation of the British rule. However, they were alarmed by the Greek Cypriot calls for ''enosis'', as they saw the union of

On 16 August 1960, Cyprus attained independence after the

On 16 August 1960, Cyprus attained independence after the

, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1991. The UK retained the two

, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1991. Tensions were heightened when Cypriot President Archbishop Makarios III called for constitutional changes, which were rejected by Turkey and opposed by Turkish Cypriots. Intercommunal violence erupted on 21 December 1963, when two Turkish Cypriots were killed at an incident involving the Greek Cypriot police. The violence resulted in the death of 364 Turkish and 174 Greek Cypriots,Oberling, Pierre. ''The road to Bellapais'' (1982), Social Science Monographs

p. 120

"According to official records, 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots were killed during the 1963–1964 crisis." destruction of 109 Turkish Cypriot or mixed villages and displacement of 25,000–30,000 Turkish Cypriots. The crisis resulted in the end of the Turkish Cypriot involvement in the administration and their claiming that it had lost its legitimacy; the nature of this event is still controversial. In some areas, Greek Cypriots prevented Turkish Cypriots from travelling and entering government buildings, while some Turkish Cypriots willingly withdrew due to the calls of the Turkish Cypriot administration. Turkish Cypriots started living in

(click on Historical review) The crisis of 1963–64 brought further intercommunal violence between the two communities, displaced more than 25,000 Turkish Cypriots into

On 15 July 1974, the Greek military junta under

On 15 July 1974, the Greek military junta under

After the restoration of constitutional order and the return of Archbishop Makarios III to Cyprus in December 1974, Turkish troops remained, occupying the northeastern portion of the island. In 1983, the Turkish Cypriot parliament, led by the Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktaş, proclaimed the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which is recognised only by Turkey.

The events of the summer of 1974 dominate the

After the restoration of constitutional order and the return of Archbishop Makarios III to Cyprus in December 1974, Turkish troops remained, occupying the northeastern portion of the island. In 1983, the Turkish Cypriot parliament, led by the Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktaş, proclaimed the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which is recognised only by Turkey.

The events of the summer of 1974 dominate the

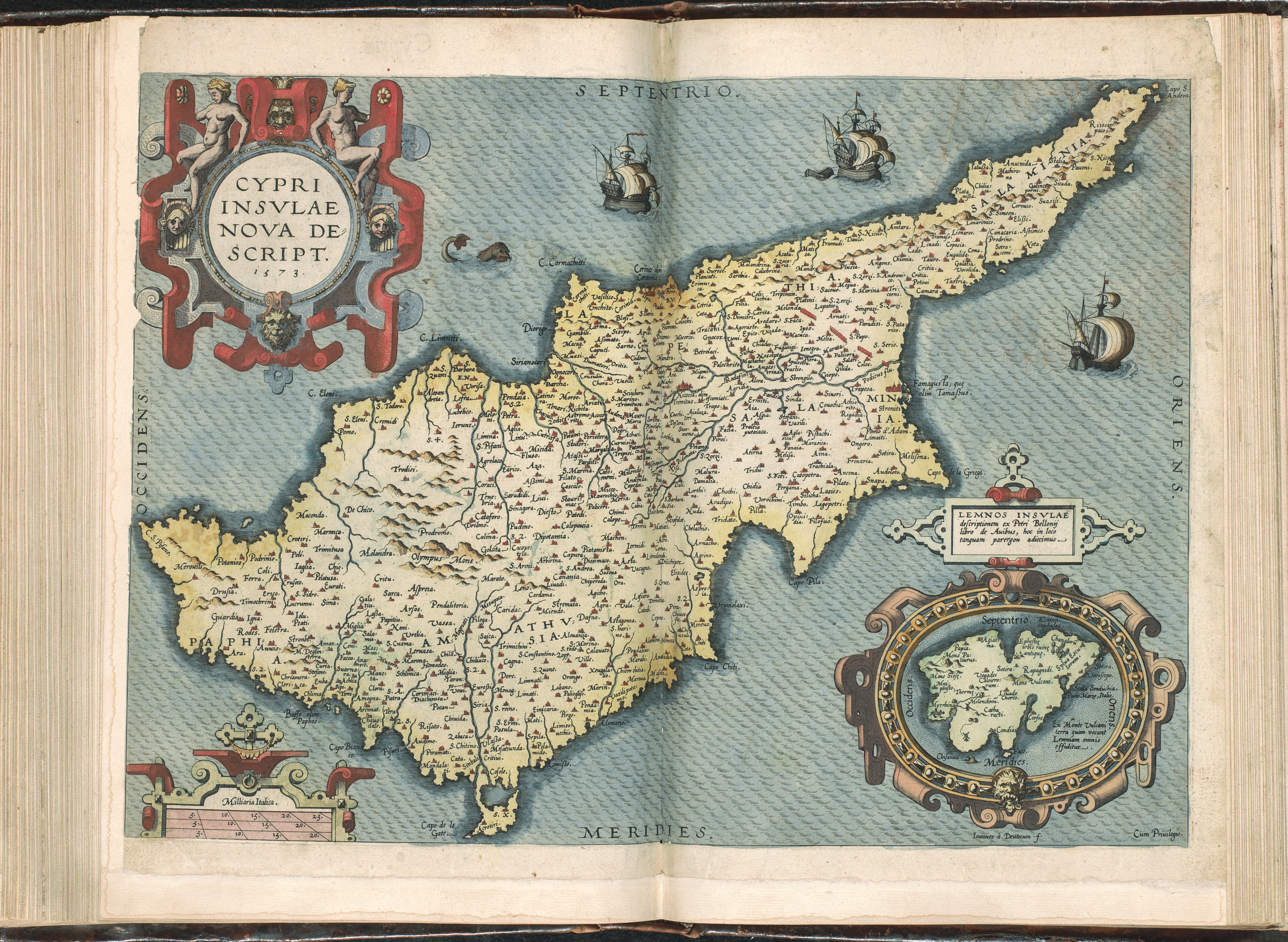

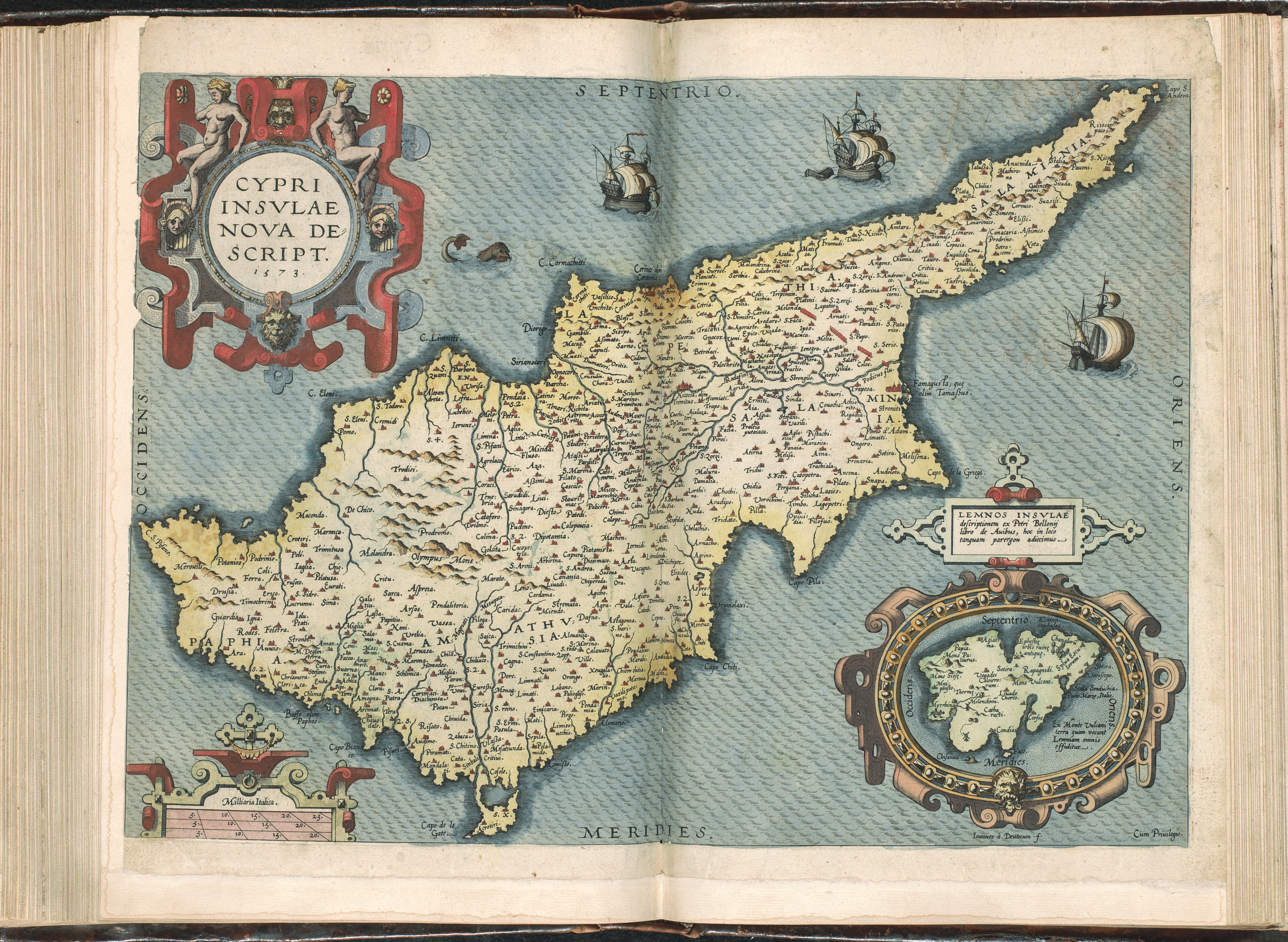

Cyprus is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after the Italian islands of

Cyprus is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after the Italian islands of

Cyprus has a

Cyprus has a

Cyprus suffers from a chronic shortage of water. The country relies heavily on rain to provide household water, but in the past 30 years average yearly precipitation has decreased. Between 2001 and 2004, exceptionally heavy annual rainfall pushed water reserves up, with supply exceeding demand, allowing total storage in the island's reservoirs to rise to an all-time high by the start of 2005.

However, since then demand has increased annually – a result of local population growth, foreigners moving to Cyprus and the number of visiting tourists – while supply has fallen as a result of more frequent droughts.

Dams remain the principal source of water both for domestic and agricultural use; Cyprus has a total of 107 dams (plus one currently under construction) and reservoirs, with a total water storage capacity of about . Water

Cyprus suffers from a chronic shortage of water. The country relies heavily on rain to provide household water, but in the past 30 years average yearly precipitation has decreased. Between 2001 and 2004, exceptionally heavy annual rainfall pushed water reserves up, with supply exceeding demand, allowing total storage in the island's reservoirs to rise to an all-time high by the start of 2005.

However, since then demand has increased annually – a result of local population growth, foreigners moving to Cyprus and the number of visiting tourists – while supply has fallen as a result of more frequent droughts.

Dams remain the principal source of water both for domestic and agricultural use; Cyprus has a total of 107 dams (plus one currently under construction) and reservoirs, with a total water storage capacity of about . Water

Cyprus is a presidential republic. The head of state and of the government is elected by a process of

Cyprus is a presidential republic. The head of state and of the government is elected by a process of  Since 1965, following clashes between the two communities, the Turkish Cypriot seats in the House remain vacant. In 1974 Cyprus was divided de facto when the Turkish army occupied the northern third of the island. The Turkish Cypriots subsequently declared independence in 1983 as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus but were recognised only by Turkey. In 1985 the TRNC adopted a constitution and held its first elections. The United Nations recognises the sovereignty of the Republic of Cyprus over the entire island of Cyprus.

The House of Representatives currently has 59 members elected for a five-year term, 56 members by

Since 1965, following clashes between the two communities, the Turkish Cypriot seats in the House remain vacant. In 1974 Cyprus was divided de facto when the Turkish army occupied the northern third of the island. The Turkish Cypriots subsequently declared independence in 1983 as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus but were recognised only by Turkey. In 1985 the TRNC adopted a constitution and held its first elections. The United Nations recognises the sovereignty of the Republic of Cyprus over the entire island of Cyprus.

The House of Representatives currently has 59 members elected for a five-year term, 56 members by

Cyprus has four

Cyprus has four

The Cypriot National Guard is the main military institution of the Republic of Cyprus. It is a

The Cypriot National Guard is the main military institution of the Republic of Cyprus. It is a

The

The

In the early 21st century the Cypriot economy has diversified and become prosperous. However, in 2012 it became affected by the Eurozone financial and banking crisis. In June 2012, the Cypriot government announced it would need € in foreign aid to support the

In the early 21st century the Cypriot economy has diversified and become prosperous. However, in 2012 it became affected by the Eurozone financial and banking crisis. In June 2012, the Cypriot government announced it would need € in foreign aid to support the  The 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis led to an agreement with the Eurogroup in March 2013 to split the country's second largest bank, the Cyprus Popular Bank (also known as Laiki Bank), into a "bad" bank which would be wound down over time and a "good" bank which would be absorbed by the Bank of Cyprus. In return for a €10 billion

The 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis led to an agreement with the Eurogroup in March 2013 to split the country's second largest bank, the Cyprus Popular Bank (also known as Laiki Bank), into a "bad" bank which would be wound down over time and a "good" bank which would be absorbed by the Bank of Cyprus. In return for a €10 billion  According to the 2017 International Monetary Fund estimates, its per capita GDP (adjusted for purchasing power) at $36,442 is below the average of the European Union. Cyprus has been sought as a base for several offshore businesses for its low tax rates. Tourism, financial services and shipping are significant parts of the economy. Economic policy of the Cyprus government has focused on meeting the criteria for admission to the European Union. The Cypriot government adopted the euro as the national currency on 1 January 2008.

Cyprus is the last EU member fully isolated from energy interconnections and it is expected that it will be connected to European network via

According to the 2017 International Monetary Fund estimates, its per capita GDP (adjusted for purchasing power) at $36,442 is below the average of the European Union. Cyprus has been sought as a base for several offshore businesses for its low tax rates. Tourism, financial services and shipping are significant parts of the economy. Economic policy of the Cyprus government has focused on meeting the criteria for admission to the European Union. The Cypriot government adopted the euro as the national currency on 1 January 2008.

Cyprus is the last EU member fully isolated from energy interconnections and it is expected that it will be connected to European network via

Available

Available

According to the CIA World Factbook, in 2001

According to the CIA World Factbook, in 2001

Main Results of the 2001 Census. Retrieved 29 February 2009. 94.8% of the population were

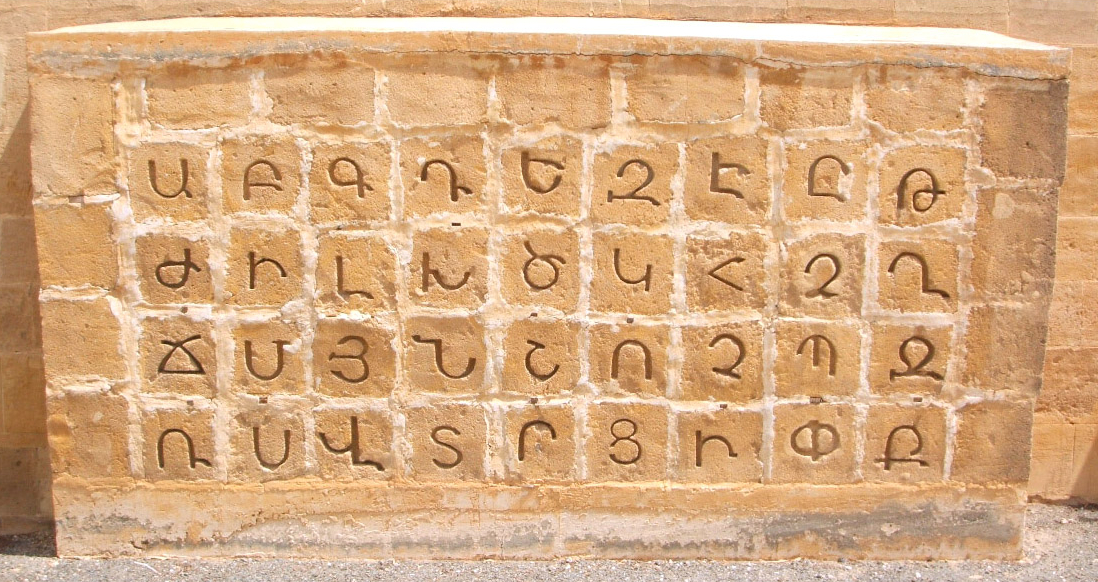

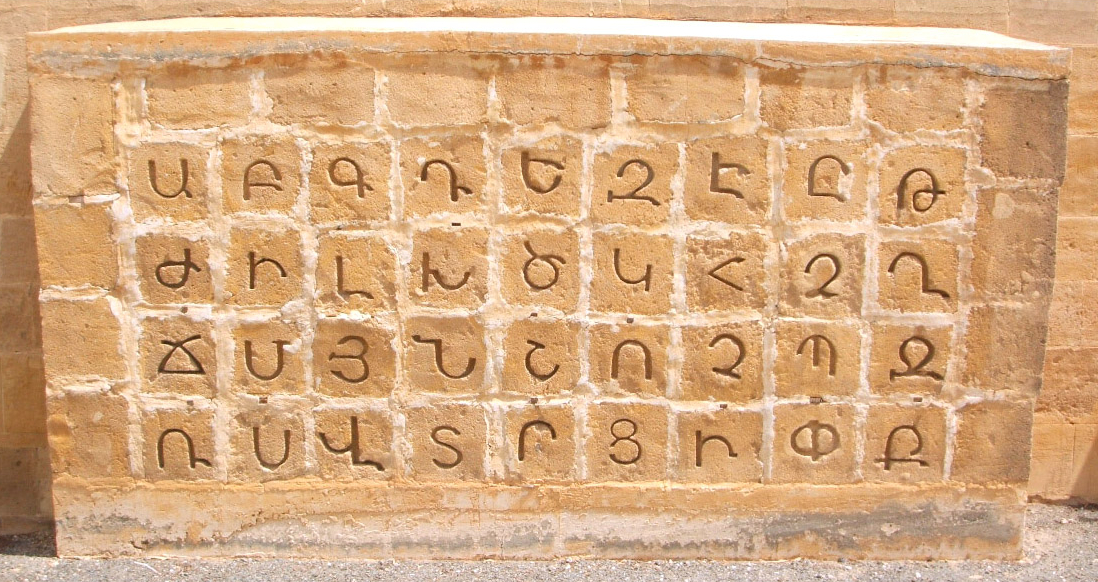

Cyprus has two official languages, Greek and Turkish. Armenian and

Cyprus has two official languages, Greek and Turkish. Armenian and

, Eurobarometer, European Commission, 2006. The everyday spoken language of Greek Cypriots is Cypriot Greek and that of Turkish Cypriots is

Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots share a lot in common in their culture due to cultural exchanges but also have differences. Several traditional food (such as

Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots share a lot in common in their culture due to cultural exchanges but also have differences. Several traditional food (such as

The art history of Cyprus can be said to stretch back up to 10,000 years, following the discovery of a series of

The art history of Cyprus can be said to stretch back up to 10,000 years, following the discovery of a series of

Glyn HUGHES

1931–2014. In many ways these two artists set the template for subsequent Cypriot art and both their artistic styles and the patterns of their education remain influential to this day. In particular the majority of Cypriot artists still train in England while others train at art schools in Greece and local art institutions such as the

The traditional

The traditional

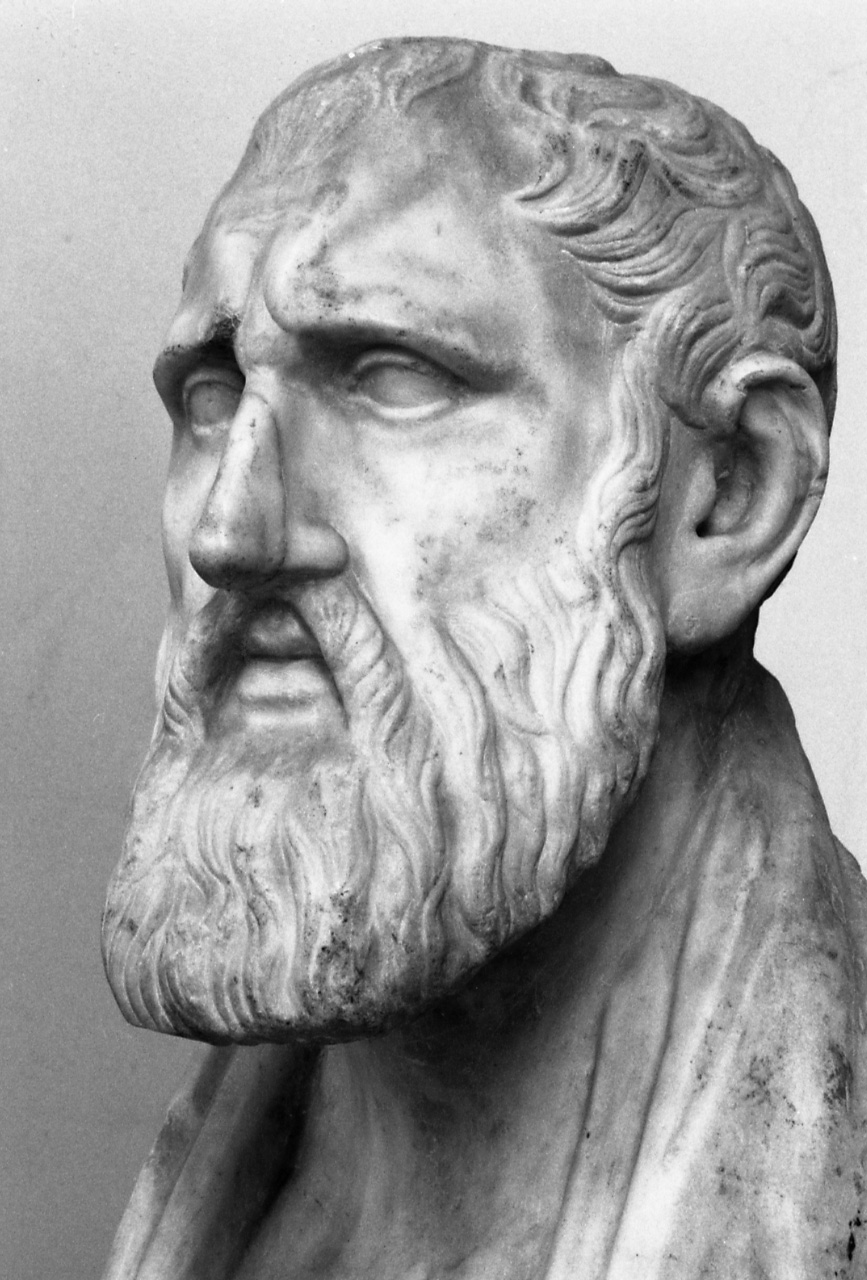

Literary production of the antiquity includes the '' Cypria'', an epic poem, probably composed in the late 7th century BC and attributed to

Literary production of the antiquity includes the '' Cypria'', an epic poem, probably composed in the late 7th century BC and attributed to  Hasan Hilmi Efendi, a Turkish Cypriot poet, was rewarded by the Ottoman sultan

Hasan Hilmi Efendi, a Turkish Cypriot poet, was rewarded by the Ottoman sultan

''Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2012'', Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, U.S. Department of State, 22 March 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2014. Local television companies in Cyprus include the state owned Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation which runs two television channels. In addition on the Greek side of the island there are the private channels ANT1 Cyprus, Plus TV, Mega Channel, Sigma TV, Nimonia TV (NTV) and New Extra. In Northern Cyprus, the local channels are BRT, the Turkish Cypriot equivalent to the Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation, and a number of private channels. The majority of local arts and cultural programming is produced by the Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation and BRT, with local arts documentaries, review programmes and filmed drama series.

During the medieval period, under the French Lusignan monarchs of Cyprus an elaborate form of courtly cuisine developed, fusing French, Byzantine and Middle Eastern forms. The Lusignan kings were known for importing Syrian cooks to Cyprus, and it has been suggested that one of the key routes for the importation of Middle Eastern recipes into France and other Western European countries, such as blancmange, was via the Lusignan Kingdom of Cyprus. These recipes became known in the West as ''vyands de Chypre'', or foods of Cyprus, and the food historian William Woys Weaver has identified over one hundred of them in English, French, Italian and German recipe books of the Middle Ages. One that became particularly popular across Europe in the medieval and early modern periods was a stew made with chicken or fish called ''malmonia'', which in English became mawmeny.

Another example of a Cypriot food ingredient entering the Western European canon is the cauliflower, still popular and used in a variety of ways on the island today, which was associated with Cyprus from the early Middle Ages. Writing in the 12th and 13th centuries the Arab botanists Ibn al-'Awwam and Ibn al-Baitar claimed the vegetable had its origins in Cyprus, and this association with the island was echoed in Western Europe, where cauliflowers were originally known as Cyprus cabbage or ''Cyprus colewart''. There was also a long and extensive trade in cauliflower seeds from Cyprus, until well into the sixteenth century.

Although much of the Lusignan food culture was lost after the fall of Cyprus to the Ottomans in 1571, a number of dishes that would have been familiar to the Lusignans survive today, including various forms of tahini and houmous, zalatina, skordalia and pickled wild song birds called ambelopoulia.

During the medieval period, under the French Lusignan monarchs of Cyprus an elaborate form of courtly cuisine developed, fusing French, Byzantine and Middle Eastern forms. The Lusignan kings were known for importing Syrian cooks to Cyprus, and it has been suggested that one of the key routes for the importation of Middle Eastern recipes into France and other Western European countries, such as blancmange, was via the Lusignan Kingdom of Cyprus. These recipes became known in the West as ''vyands de Chypre'', or foods of Cyprus, and the food historian William Woys Weaver has identified over one hundred of them in English, French, Italian and German recipe books of the Middle Ages. One that became particularly popular across Europe in the medieval and early modern periods was a stew made with chicken or fish called ''malmonia'', which in English became mawmeny.

Another example of a Cypriot food ingredient entering the Western European canon is the cauliflower, still popular and used in a variety of ways on the island today, which was associated with Cyprus from the early Middle Ages. Writing in the 12th and 13th centuries the Arab botanists Ibn al-'Awwam and Ibn al-Baitar claimed the vegetable had its origins in Cyprus, and this association with the island was echoed in Western Europe, where cauliflowers were originally known as Cyprus cabbage or ''Cyprus colewart''. There was also a long and extensive trade in cauliflower seeds from Cyprus, until well into the sixteenth century.

Although much of the Lusignan food culture was lost after the fall of Cyprus to the Ottomans in 1571, a number of dishes that would have been familiar to the Lusignans survive today, including various forms of tahini and houmous, zalatina, skordalia and pickled wild song birds called ambelopoulia.

Seafood and fish dishes include squid, octopus, red mullet, and

Seafood and fish dishes include squid, octopus, red mullet, and

, ''BBC News'', 18 October 2004 This island has protected geographical indication (PGI) for its ''lokum'' produced in the village of

Sport governing bodies include the Cyprus Football Association,

Sport governing bodies include the Cyprus Football Association,

excerpt

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Sacopoulo, Marina (1966). ''Chypre d'aujourd'hui''. Paris: G.-P. Maisonneuve et Larose. 406 p., ill. with b&w photos. and fold. maps. * *

Cyprus

''

Timeline of Cyprus by BBC

from ''UCB Libraries GovPubs''

Cyprus

information from the

Cyprus profile

from the

The UN in Cyprus

Cypriot Pottery, Bryn Mawr College Art and Artifact Collections

''The Cesnola collection of Cypriot art : stone sculpture''

a fully digitised text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art libraries * http://cypernochkreta.dinstudio.se Government

Cyprus High Commission Trade Centre – London

Republic of Cyprus – English Language

Press and Information Office – Ministry of Interior

Annan Plan

Tourism

Read about Cyprus on visitcyprus.com

– the official travel portal for Cyprus

Cyprus informational portal and open platform for contribution of Cyprus-related content

– www.Cyprus.com * Official publications

* [http://www.moi.gov.cy/moi/pio/pio.nsf/All/BD477C55623013C5C2256D740027CF98?OpenDocument Legal Issues arising from certain population transfers and displacements on the territory of the Republic of Cyprus in the period since 20 July 1974]

Address to Cypriots by President Papadopoulos (FULL TEXT)

Official Cyprus Government Web Site

Embassy of Greece, USA – Cyprus: Geographical and Historical Background

{{coord, 35, N, 33, E, type:country_region:CY_scale:2500000_source:GNS , display=title Republics in the Commonwealth of Nations Eastern Mediterranean International islands Island countries Islands of Asia Islands of Europe Mediterranean islands Member states of the Commonwealth of Nations Member states of the European Union Member states of the Union for the Mediterranean Member states of the United Nations Middle Eastern countries Near Eastern countries Southeastern European countries Southern European countries Western Asian countries States and territories established in 1960 Countries in Asia Countries in Europe Greek-speaking countries and territories Turkish-speaking countries and territories Countries of Europe with multiple official languages

island country

An island country, island state or an island nation is a country whose primary territory consists of one or more islands or parts of islands. Approximately 25% of all independent countries are island countries. Island countries are historically ...

located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geographically in Western Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes A ...

, its cultural ties and geopolitics are overwhelmingly Southern Europe

Southern Europe is the southern region of Europe. It is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is essentially marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of Southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Alb ...

an. Cyprus is the third-largest and third-most populous island in the Mediterranean. It is located north of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, east of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

, south of Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

, and west of Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

. Its capital and largest city is Nicosia

Nicosia ( ; el, Λευκωσία, Lefkosía ; tr, Lefkoşa ; hy, Նիկոսիա, romanized: ''Nikosia''; Cypriot Arabic: Nikusiya) is the largest city, capital, and seat of government of Cyprus. It is located near the centre of the Mesaori ...

. The northeast portion of the island is ''de facto'' governed by the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

Northern Cyprus ( tr, Kuzey Kıbrıs), officially the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC; tr, Kuzey Kıbrıs Türk Cumhuriyeti, ''KKTC''), is a ''de facto'' state that comprises the northeastern portion of the island of Cyprus. Reco ...

, which was established after the 1974 invasion and which is recognised as a country only by Turkey.

The earliest known human activity on the island dates to around the 10th millennium BC

The 10th millennium BC spanned the years 10,000 BC to 9001 BC (c. 12 ka to c. 11 ka). It marks the beginning of the transition from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic via the interim Mesolithic ( Northern Europe and Western Europe) and Ep ...

. Archaeological remains include the well-preserved ruins from the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

such as Salamis and Kourion, and Cyprus is home to some of the oldest water wells in the world. Cyprus was settled by Mycenaean Greeks in two waves in the 2nd millennium BC. As a strategic location in the Eastern Mediterranean

Eastern Mediterranean is a loose definition of the eastern approximate half, or third, of the Mediterranean Sea, often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea.

It typically embraces all of that sea's coastal zones, referring to commun ...

, it was subsequently occupied by several major powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

, including the empires of the Assyrians, Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

and Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian. ...

, from whom the island was seized in 333 BC by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

. Subsequent rule by Ptolemaic Egypt, the Classical and Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantino ...

, Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

s for a short period, the French Lusignan dynasty and the Venetians was followed by over three centuries of Ottoman rule between 1571 and 1878 (''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legall ...

'' until 1914).

Cyprus was placed under the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

's administration based on the Cyprus Convention in 1878 and was formally annexed by the UK in 1914. The future of the island became a matter of disagreement between the two prominent ethnic communities, Greek Cypriots

Greek Cypriots or Cypriot Greeks ( el, Ελληνοκύπριοι, Ellinokýprioi, tr, Kıbrıs Rumları) are the ethnic Greek population of Cyprus, forming the island's largest ethnolinguistic community. According to the 2011 census, 659,115 ...

, who made up 77% of the population in 1960, and Turkish Cypriots, who made up 18% of the population. From the 19th century onwards, the Greek Cypriot population pursued ''enosis

''Enosis'' ( el, Ένωσις, , "union") is the movement of various Greek communities that live outside Greece for incorporation of the regions that they inhabit into the Greek state. The idea is related to the Megali Idea, an irredentist conc ...

'', union with Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

, which became a Greek national policy in the 1950s. The Turkish Cypriot population initially advocated the continuation of the British rule, then demanded the annexation of the island to Turkey, and in the 1950s, together with Turkey, established a policy of '' taksim'', the partition of Cyprus and the creation of a Turkish polity in the north.

Following nationalist violence in the 1950s, Cyprus was granted independence in 1960. The crisis of 1963–64 brought further intercommunal violence between the two communities, displaced more than 25,000 Turkish Cypriots into enclaves

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

and brought the end of Turkish Cypriot representation in the republic. On 15 July 1974, a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

was staged by Greek Cypriot nationalists and elements of the Greek military junta in an attempt at ''enosis''. This action precipitated the Turkish invasion of Cyprus

The Turkish invasion of Cyprus began on 20 July 1974 and progressed in two phases over the following month. Taking place upon a background of intercommunal violence between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, and in response to a Greek junta-s ...

on 20 July, which led to the capture of the present-day territory of Northern Cyprus

Northern Cyprus ( tr, Kuzey Kıbrıs), officially the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC; tr, Kuzey Kıbrıs Türk Cumhuriyeti, ''KKTC''), is a '' de facto'' state that comprises the northeastern portion of the island of Cyprus. Rec ...

and the displacement of over 150,000 Greek Cypriots and 50,000 Turkish Cypriots. A separate Turkish Cypriot state in the north was established by unilateral declaration in 1983; the move was widely condemned by the international community

The international community is an imprecise phrase used in geopolitics and international relations to refer to a broad group of people and governments of the world.

As a rhetorical term

Aside from its use as a general descriptor, the term is t ...

, with Turkey alone recognising the new state. These events and the resulting political situation are matters of a continuing dispute.

Cyprus is a major tourist destination in the Mediterranean. With an advanced, high-income economy and a very high Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistic composite index of life expectancy, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income indicators, w ...

, the Republic of Cyprus has been a member of the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

since 1961 and was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath ...

until it joined the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

on 1 May 2004. On 1 January 2008, the Republic of Cyprus joined the eurozone

The euro area, commonly called eurozone (EZ), is a currency union of 19 member states of the European Union (EU) that have adopted the euro (€) as their primary currency and sole legal tender, and have thus fully implemented EMU pol ...

.

Etymology

The earliest attested reference to ''Cyprus'' is the 15th century BC

The earliest attested reference to ''Cyprus'' is the 15th century BC Mycenaean Greek

Mycenaean Greek is the most ancient attested form of the Greek language, on the Greek mainland and Crete in Mycenaean Greece (16th to 12th centuries BC), before the hypothesised Dorian invasion, often cited as the '' terminus ad quem'' for th ...

, ''ku-pi-ri-jo'', meaning "Cypriot" (Greek: ), written in Linear B

Linear B was a syllabic script used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest attested form of Greek. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries. The oldest Mycenaean writing dates to about 1400 BC. It is descended from ...

syllabic script.

The classical Greek form of the name is (''Kýpros'').

The etymology of the name is unknown.

Suggestions include:

* the Greek word for the Mediterranean cypress tree (''Cupressus sempervirens

''Cupressus sempervirens'', the Mediterranean cypress (also known as Italian cypress, Tuscan cypress, Persian cypress, or pencil pine), is a species of cypress native to the eastern Mediterranean region, in northeast Libya, southern Albania, so ...

''), κυπάρισσος (''kypárissos'')

* the Greek name of the henna tree (''Lawsonia alba''), κύπρος (''kýpros'')

* an Eteocypriot word for copper. It has been suggested, for example, that it has roots in the Sumerian word for copper (''zubar'') or for bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids suc ...

(''kubar''), from the large deposits of copper ore found on the island.

Through overseas trade, the island has given its name to the Classical Latin

Classical Latin is the form of Literary Latin recognized as a literary standard by writers of the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. It was used from 75 BC to the 3rd century AD, when it developed into Late Latin. In some later period ...

word for copper through the phrase ''aes Cyprium'', "metal of Cyprus", later shortened to ''Cuprum''. R. S. P. Beekes, ''Etymological Dictionary of Greek'', Brill, 2009, p. 805 (''s.v.'' "Κύπρος").

The standard demonym

A demonym (; ) or gentilic () is a word that identifies a group of people (inhabitants, residents, natives) in relation to a particular place. Demonyms are usually derived from the name of the place (hamlet, village, town, city, region, province, ...

relating to Cyprus or its people or culture is '' Cypriot''. The terms ''Cypriote'' and ''Cyprian'' (later a personal name) are also used, though less frequently.

The state's official name in Greek literally translates to "Cypriot Republic" in English, but this translation is not used officially; "Republic of Cyprus" is used instead.

History

Prehistoric and Ancient Cyprus

The earliest confirmed site of human activity on Cyprus isAetokremnos

Aetokremnos is a rock shelter near Limassol on the southern coast of Cyprus. It is situated on a steep cliff site c. above the Mediterranean sea. The name means ''"Cliff of the eagles"'' in Greek. Around have been excavated and out of the four ...

, situated on the south coast, indicating that hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fung ...

s were active on the island from around 10,000 BC, with settled village communities

The study of village communities has become one of the fundamental methods of discussing the ancient history of institutions.

Wales

Frederic Seebohm has called our attention to the interesting surveys of Welsh tracts of country made in the 1 ...

dating from 8200 BC. The arrival of the first humans correlates with the extinction of the 75 cm high Cyprus dwarf hippopotamus and 1 metre tall Cyprus dwarf elephant

''Palaeoloxodon cypriotes'', the Cyprus dwarf elephant, is an extinct species that inhabited the island of Cyprus during the Late Pleistocene. Remains comprise 44 molars, found in the north of the island, seven molars discovered in the south-eas ...

, the only large mammals native to the island. Water well

A well is an excavation or structure created in the ground by digging, driving, or drilling to access liquid resources, usually water. The oldest and most common kind of well is a water well, to access groundwater in underground aquifers. T ...

s discovered by archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

s in western Cyprus are believed to be among the oldest in the world, dated at 9,000 to 10,500 years old.

Remains of an 8-month-old cat were discovered buried with a human body at a separate Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

site in Cyprus. The grave is estimated to be 9,500 years old (7500 BC), predating ancient Egyptian civilisation and pushing back the earliest known feline-human association significantly. The remarkably well-preserved Neolithic village of Khirokitia is a UNESCO World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

, dating to approximately 6800 BC.

During the Late Bronze Age, the island experienced two waves of Greek settlement.Thomas, Carol G. and Conant, Craig: ''The Trojan War'', pp. 121–122. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005. , 9780313325267. The first wave consisted of Mycenaean Greek

Mycenaean Greek is the most ancient attested form of the Greek language, on the Greek mainland and Crete in Mycenaean Greece (16th to 12th centuries BC), before the hypothesised Dorian invasion, often cited as the '' terminus ad quem'' for th ...

traders, who started visiting Cyprus around 1400 BC. A major wave of Greek settlement is believed to have taken place following the Late Bronze Age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a time of widespread societal collapse during the 12th century BC, between c. 1200 and 1150. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean (North Africa and Southeast Europe) and the Near ...

of Mycenaean Greece from 1100 to 1050 BC, with the island's predominantly Greek character dating from this period. The first recorded name of a Cypriot king is ''Kushmeshusha'', as appears on letters sent to Ugarit in the 13th century BCE. Cyprus occupies an important role in Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities o ...

, being the birthplace of Aphrodite

Aphrodite ( ; grc-gre, Ἀφροδίτη, Aphrodítē; , , ) is an ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, and procreation. She was syncretized with the Roman goddess . Aphrodite's major symbols incl ...

and Adonis

In Greek mythology, Adonis, ; derived from the Canaanite word ''ʼadōn'', meaning "lord". R. S. P. Beekes, ''Etymological Dictionary of Greek'', Brill, 2009, p. 23. was the mortal lover of the goddess Aphrodite.

One day, Adonis was gored by ...

, and home to King Cinyras, Teucer and Pygmalion. Literary evidence suggests an early Phoenician presence at Kition

Kition ( Egyptian: ; Phoenician: , , or , ; Ancient Greek: , ; Latin: ) was a city-kingdom on the southern coast of Cyprus (in present-day Larnaca). According to the text on the plaque closest to the excavation pit of the Kathari site (as of ...

, which was under Tyrian rule at the beginning of the 10th century BC. Some Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

n merchants who were believed to come from Tyre colonised the area and expanded the political influence of Kition. After c. 850 BC, the sanctuaries t the Kathari site

T, or t, is the twentieth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''tee'' (pronounced ), plural ''tees''. It is deri ...

were rebuilt and reused by the Phoenicians. Cyprus is at a strategic location in the Middle East. It was ruled by the

Cyprus is at a strategic location in the Middle East. It was ruled by the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew ...

for a century starting in 708 BC, before a brief spell under Egyptian rule and eventually Achaemenid

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, wikt:𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎶, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an History of Iran#Classical antiquity, ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Bas ...

rule in 545 BC. The Cypriots, led by Onesilus

Onesilus or Onesilos ( el, Ὀνήσιλος, "useful one"; died 497 BC) was the brother of king Gorgos (Gorgus) of the Greek city-state of Salamis on the island of Cyprus. He is known only through the work of Herodotus (''Histories'', V.104–11 ...

, king of Salamis, joined their fellow Greeks in the Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionia ...

n cities during the unsuccessful Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisf ...

in 499 BC against the Achaemenids. The revolt was suppressed, but Cyprus managed to maintain a high degree of autonomy and remained inclined towards the Greek world.

During the whole period of the Persian rule, there is a continuity in the reign of the Cypriot kings and during their rebellions they were crushed by Persian rulers from Asia Minor, which is an indication that the Cypriots were ruling the island with directly regulated relations with the Great King and there wasn't a Persian satrap.ALEXANDER_THE_GREAT_AND_THE_KINGDOMS_OF_CYPRUS_A_RECONSIDERATION ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND THE KINGDOMS OF CYPRUS -- A RECONSIDERATION/ref> The Kingdoms of Cyprus enjoyed special privileges and a semi-autonomous status, but they were still considered vassal subjects of the Great King. The island was conquered by

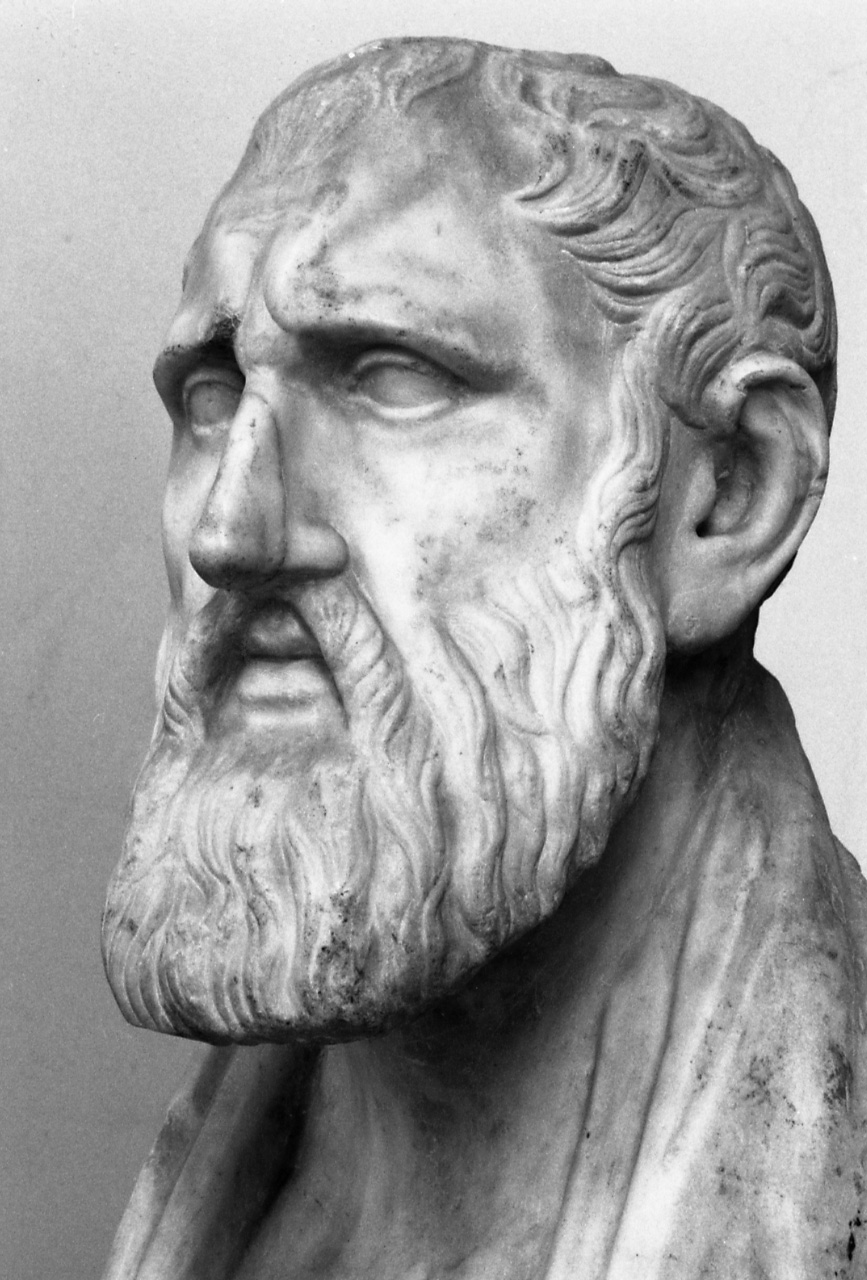

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

in 333 BC and Cypriot navy helped Alexander during the Siege of Tyre (332 BC). Cypriot fleet were also sent to help Amphoterus (admiral)

Amphoterus (Greek: ) the brother of Craterus, was appointed by Alexander the Great commander of the fleet in the Hellespont in 333 BC. Amphoterus' appointment recognized his successful attempts to subdue the islands between Greece and Asia which ha ...

. In addition, Alexander had two Cypriot generals Stasander Stasander ( grc, Στάσανδρος; lived 4th century B.C.) was a Soloian general in the service of Alexander the Great. Upon Alexander's death he became the satrap of Aria and Drangiana. He lost control of his satrapies after being defeated by ...

and Stasanor both from the Soli and later both became satraps in Alexander's empire.

Following Alexander's death, the division of his empire, and the subsequent Wars of the Diadochi

The Wars of the Diadochi ( grc, Πόλεμοι τῶν Διαδόχων, '), or Wars of Alexander's Successors, were a series of conflicts that were fought between the generals of Alexander the Great, known as the Diadochi, over who would rule ...

, Cyprus became part of the Hellenistic empire of Ptolemaic Egypt. It was during this period that the island was fully Hellenized

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in th ...

. In 58 BC Cyprus was acquired by the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

.

Roman Cyprus

Middle Ages

When the

When the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

was divided into Eastern and Western parts in 286, Cyprus became part of the East Roman Empire (also called the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

), and would remain so for some 900 years. Under Byzantine rule, the Greek orientation that had been prominent since antiquity developed the strong Hellenistic-Christian character that continues to be a hallmark of the Greek Cypriot community.

Beginning in 649, Cyprus endured several attacks launched by raiders from the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

, which continued for the next 300 years. Many were quick piratical raids, but others were large-scale attacks in which many Cypriots were slaughtered and great wealth carried off or destroyed. There are no Byzantine churches which survive from this period; thousands of people were killed, and many cities – such as Salamis – were destroyed and never rebuilt. Byzantine rule was restored in 965, when Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas scored decisive victories on land and sea.

In 1156 Raynald of Châtillon and Thoros II of Armenia brutally sacked Cyprus over a period of three weeks, stealing so much plunder and capturing so many of the leading citizens and their families for ransom, that the island took generations to recover. Several Greek priests were mutilated and sent away to Constantinople.

In 1185 Isaac Komnenos, a member of the Byzantine imperial family, took over Cyprus and declared it independent of the Empire. In 1191, during the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity ( Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

, Richard I of England

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Aquitaine and Duchy of Gascony, Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Co ...

captured the island from Isaac. He used it as a major supply base that was relatively safe from the Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia ...

s. A year later Richard sold the island to the Knights Templar

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

, who, following a bloody revolt, in turn sold it to Guy of Lusignan. His brother and successor Aimery was recognised as King of Cyprus by Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor

Henry VI (German: ''Heinrich VI.''; November 1165 – 28 September 1197), a member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, was King of Germany ( King of the Romans) from 1169 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1191 until his death. From 1194 he was also King of ...

.

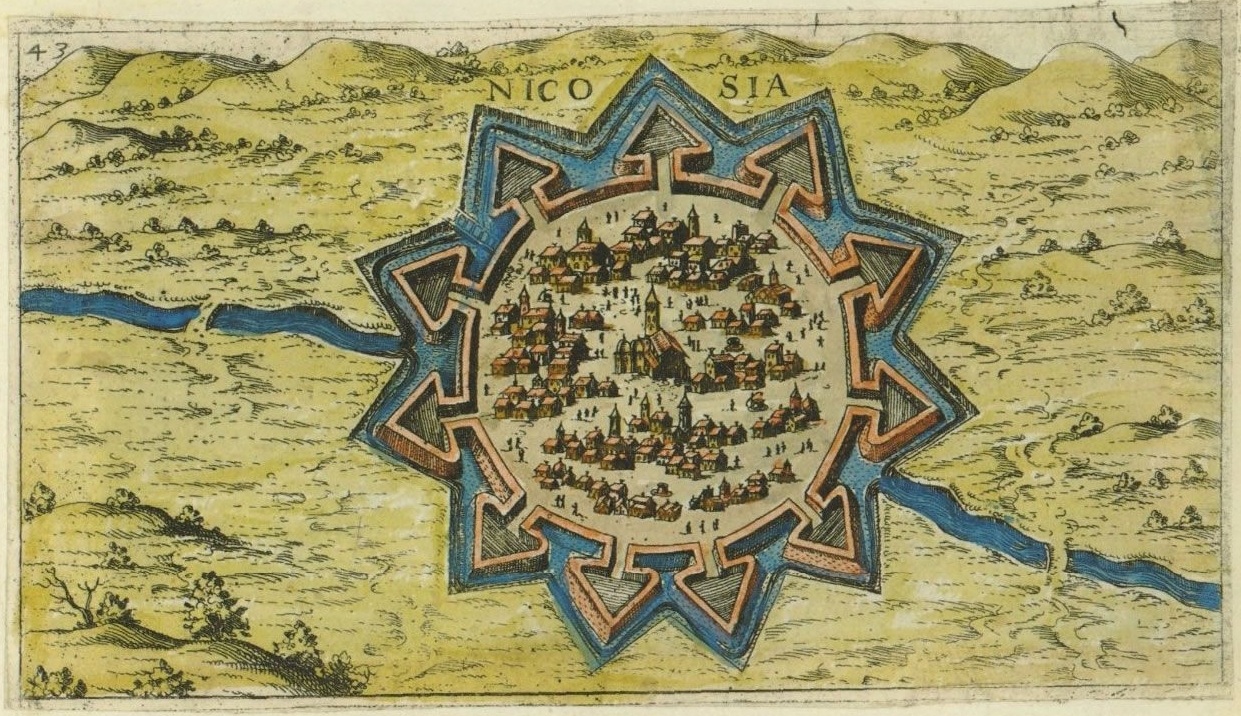

Following the death in 1473 of James II, the last Lusignan king, the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

assumed control of the island, while the late king's Venetian widow, Queen Catherine Cornaro, reigned as figurehead. Venice formally annexed the Kingdom of Cyprus

The Kingdom of Cyprus (french: Royaume de Chypre, la, Regnum Cypri) was a state that existed between 1192 and 1489. It was ruled by the French House of Lusignan. It comprised not only the island of Cyprus, but it also had a foothold on the Ana ...

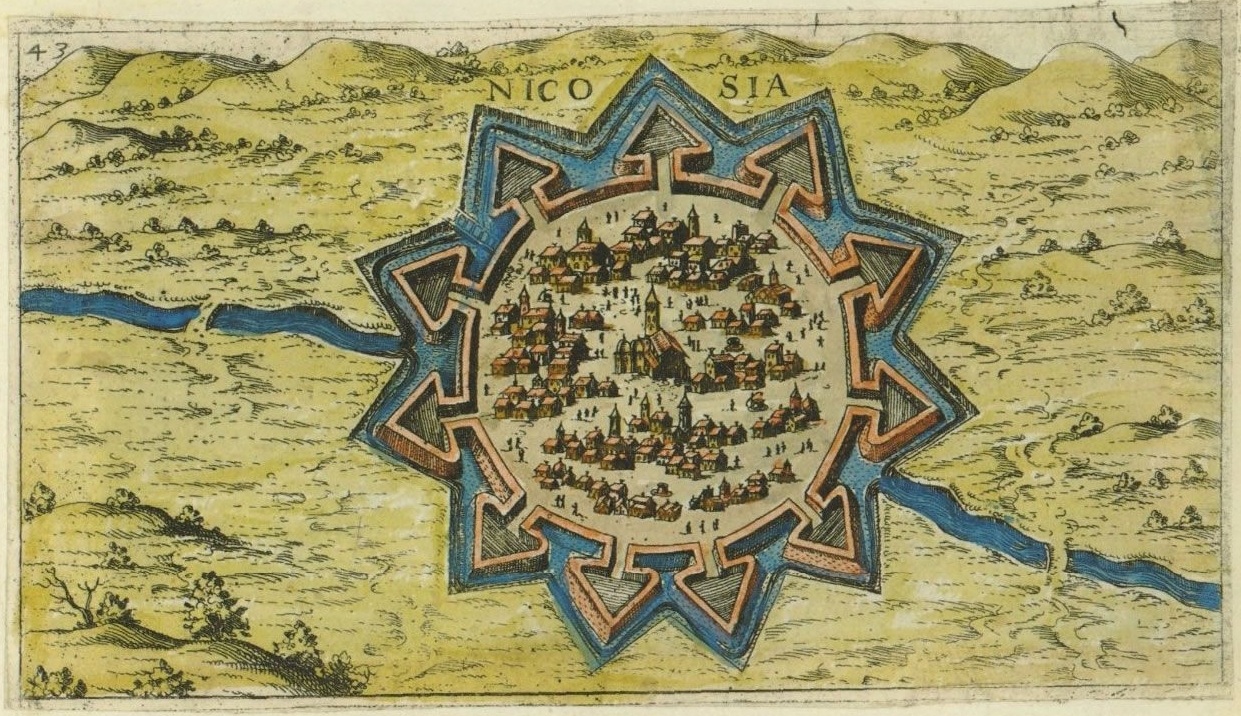

in 1489, following the abdication of Catherine. The Venetians fortified Nicosia

Nicosia ( ; el, Λευκωσία, Lefkosía ; tr, Lefkoşa ; hy, Նիկոսիա, romanized: ''Nikosia''; Cypriot Arabic: Nikusiya) is the largest city, capital, and seat of government of Cyprus. It is located near the centre of the Mesaori ...

by building the Walls of Nicosia

The Walls of Nicosia, also known as the Venetian Walls, are a series of defensive walls which surround Nicosia the capital city of Cyprus. The first city walls were built in the Middle Ages, but they were completely rebuilt in the mid-16th centur ...

, and used it as an important commercial hub. Throughout Venetian rule, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

frequently raided Cyprus. In 1539 the Ottomans destroyed Limassol

Limassol (; el, Λεμεσός, Lemesós ; tr, Limasol or ) is a city on the southern coast of Cyprus and capital of the district with the same name. Limassol is the second largest urban area in Cyprus after Nicosia, with an urban populatio ...

and so fearing the worst, the Venetians also fortified Famagusta

Famagusta ( , ; el, Αμμόχωστος, Ammóchostos, ; tr, Gazimağusa or ) is a city on the east coast of Cyprus. It is located east of Nicosia and possesses the deepest harbour of the island. During the Middle Ages (especially under t ...

and Kyrenia

Kyrenia ( el, Κερύνεια ; tr, Girne ) is a city on the northern coast of Cyprus, noted for its historic harbour and castle. It is under the ''de facto'' control of Northern Cyprus.

While there is evidence showing that the wider region ...

.

Although the Lusignan French aristocracy remained the dominant social class in Cyprus throughout the medieval period, the former assumption that Greeks were treated only as serfs on the island is no longer considered by academics to be accurate. It is now accepted that the medieval period saw increasing numbers of Greek Cypriots elevated to the upper classes, a growing Greek middle ranks, and the Lusignan royal household even marrying Greeks. This included King John II of Cyprus who married Helena Palaiologina.

Cyprus under the Ottoman Empire

In 1570, a full-scale Ottoman assault with 60,000 troops brought the island under Ottoman control, despite stiff resistance by the inhabitants of Nicosia and Famagusta. Ottoman forces capturing Cyprus massacred many Greek and Armenian Christian inhabitants. The previous Latin elite were destroyed and the first significant demographic change since antiquity took place with the formation of a Muslim community. Soldiers who fought in the conquest settled on the island and Turkish peasants and craftsmen were brought to the island from

In 1570, a full-scale Ottoman assault with 60,000 troops brought the island under Ottoman control, despite stiff resistance by the inhabitants of Nicosia and Famagusta. Ottoman forces capturing Cyprus massacred many Greek and Armenian Christian inhabitants. The previous Latin elite were destroyed and the first significant demographic change since antiquity took place with the formation of a Muslim community. Soldiers who fought in the conquest settled on the island and Turkish peasants and craftsmen were brought to the island from Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. This new community also included banished Anatolian tribes, "undesirable" persons and members of various "troublesome" Muslim sects, as well as a number of new converts on the island.

The Ottomans abolished the

The Ottomans abolished the feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

system previously in place and applied the millet system to Cyprus, under which non-Muslim peoples were governed by their own religious authorities. In a reversal from the days of Latin rule, the head of the Church of Cyprus

The Church of Cyprus ( el, Ἐκκλησία τῆς Κύπρου, translit=Ekklisia tis Kyprou; tr, Kıbrıs Kilisesi) is one of the autocephalous Greek Orthodox churches that together with other Eastern Orthodox churches form the communion ...

was invested as leader of the Greek Cypriot population and acted as mediator between Christian Greek Cypriots and the Ottoman authorities. This status ensured that the Church of Cyprus was in a position to end the constant encroachments of the Roman Catholic Church. Ottoman rule of Cyprus was at times indifferent, at times oppressive, depending on the temperaments of the sultans and local officials, and the island began over 250 years of economic decline.Cyprus – Ottoman Rule, ''U.S. Library of Congress'' The ratio of Muslims to Christians fluctuated throughout the period of Ottoman domination. In 1777–78, 47,000 Muslims constituted a majority over the island's 37,000 Christians. By 1872, the population of the island had risen to 144,000, comprising 44,000 Muslims and 100,000 Christians. The Muslim population included numerous

crypto-Christians

Crypto-Christianity is the secret practice of Christianity, usually while attempting to camouflage it as another faith or observing the rituals of another religion publicly. In places and time periods where Christians were persecuted or Christiani ...

, including the Linobambaki

The Linobambaki or Linovamvaki were a Crypto-Christian community in Cyprus, predominantly of Catholic and Greek-Orthodox descent who were persecuted for their religion during Ottoman rule. They assimilated into the Turkish Cypriot community duri ...

, a crypto-Catholic community that arose due to religious persecution of the Catholic community by the Ottoman authorities; this community would assimilate into the Turkish Cypriot community during British rule.

As soon as the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

broke out in 1821, several Greek Cypriots left for Greece to join the Greek forces. In response, the Ottoman governor of Cyprus arrested and executed 486 prominent Greek Cypriots, including the Archbishop of Cyprus, Kyprianos, and four other bishops. In 1828, modern Greece's first president Ioannis Kapodistrias called for union of Cyprus with Greece, and numerous minor uprisings took place. Reaction to Ottoman misrule led to uprisings by both Greek and Turkish Cypriots, although none were successful. After centuries of neglect by the Ottoman Empire, the poverty of most of the people and the ever-present tax collectors fuelled Greek nationalism, and by the 20th century the idea of ''enosis

''Enosis'' ( el, Ένωσις, , "union") is the movement of various Greek communities that live outside Greece for incorporation of the regions that they inhabit into the Greek state. The idea is related to the Megali Idea, an irredentist conc ...

'', or union, with newly independent Greece was firmly rooted among Greek Cypriots.

Under Ottoman rule, numeracy, school enrolment and literacy rates were all low. They persisted some time after Ottoman rule ended, and then increased rapidly during the twentieth century.

Cyprus under the British Empire

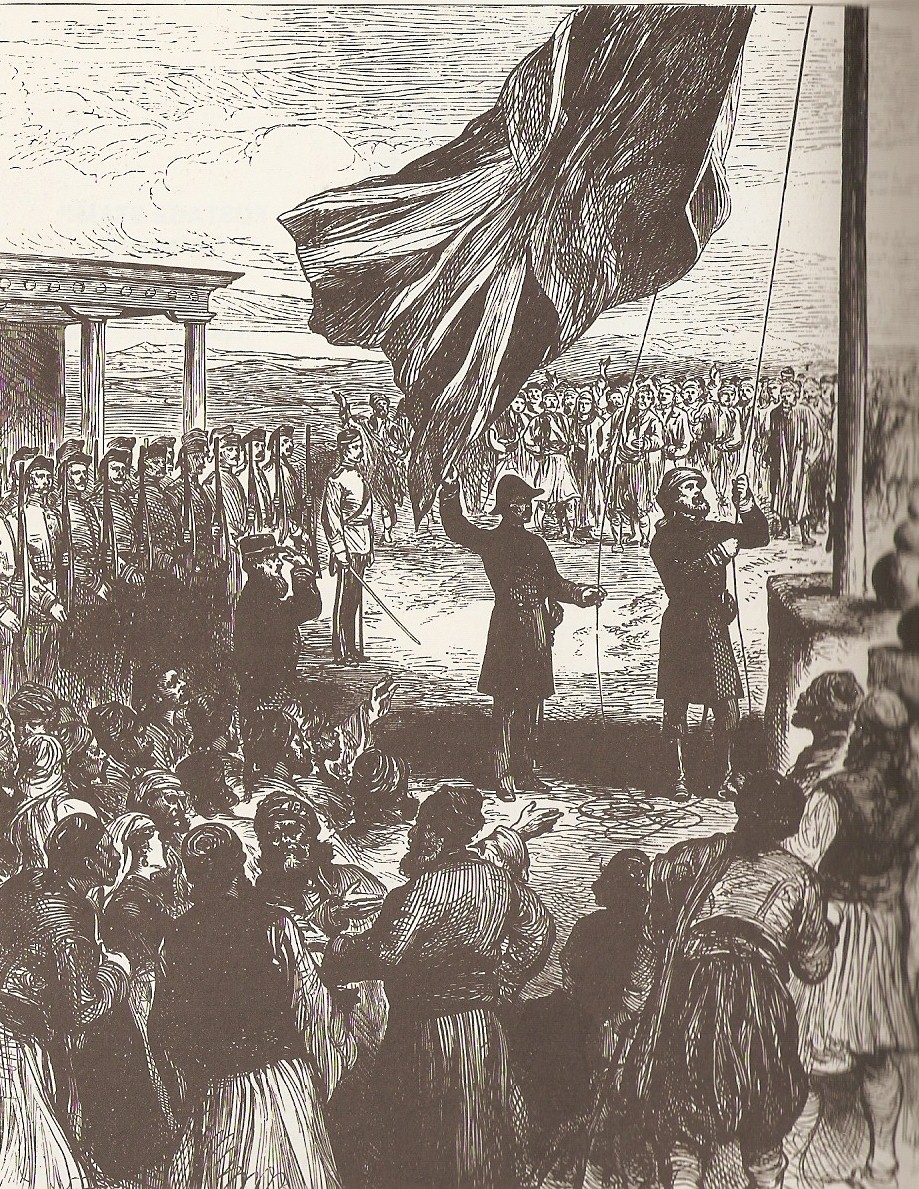

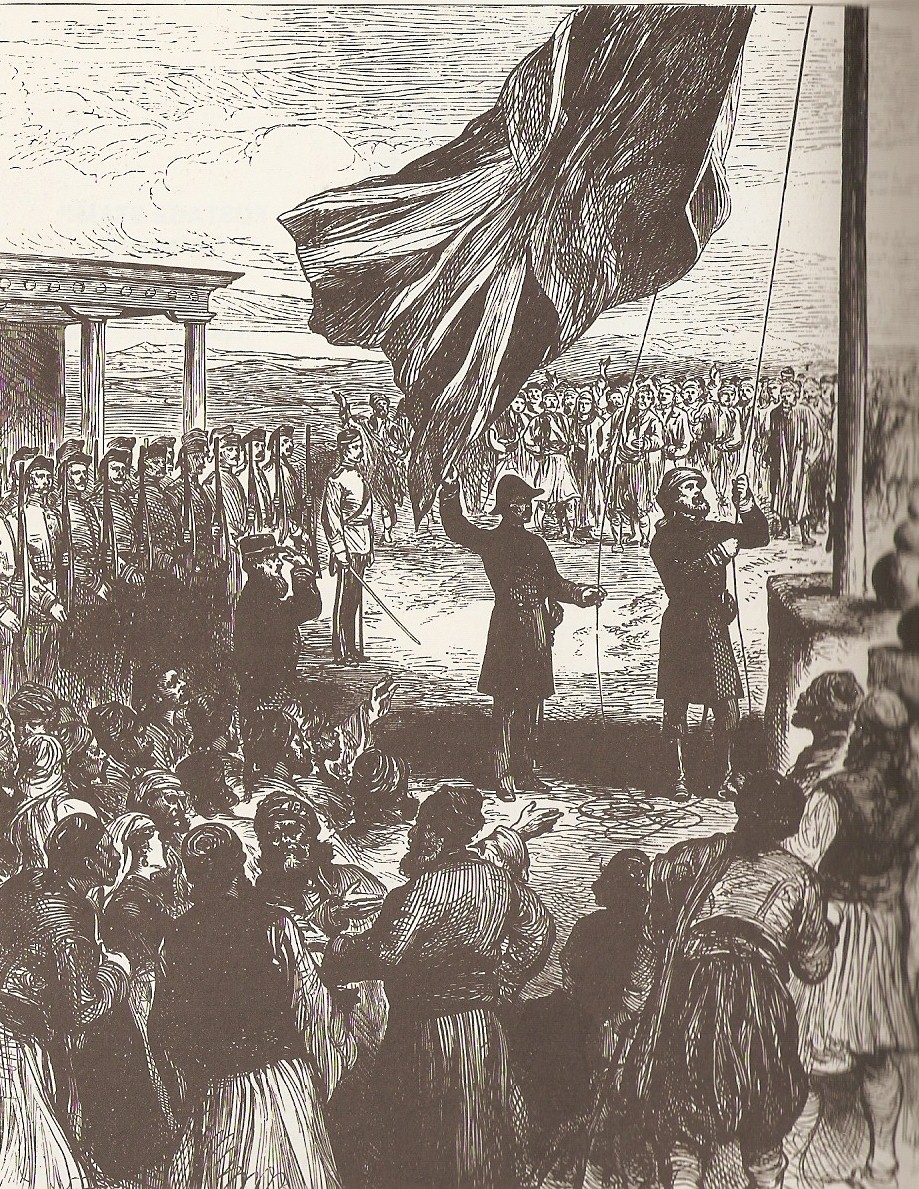

In the aftermath of the

In the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 ( tr, 93 Harbi, lit=War of ’93, named for the year 1293 in the Islamic calendar; russian: Русско-турецкая война, Russko-turetskaya voyna, "Russian–Turkish war") was a conflict between th ...

and the Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

, Cyprus was leased

A lease is a contractual arrangement calling for the user (referred to as the ''lessee'') to pay the owner (referred to as the ''lessor'') for the use of an asset. Property, buildings and vehicles are common assets that are leased. Industri ...

to the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

which de facto took over its administration in 1878 (though, in terms of sovereignty, Cyprus remained a ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legall ...

'' Ottoman territory until 5 November 1914, together with Egypt and Sudan) in exchange for guarantees that Britain would use the island as a base to protect the Ottoman Empire against possible Russian aggression.

The island would serve Britain as a key military base for its colonial routes. By 1906, when the Famagusta harbour was completed, Cyprus was a strategic naval outpost overlooking the

The island would serve Britain as a key military base for its colonial routes. By 1906, when the Famagusta harbour was completed, Cyprus was a strategic naval outpost overlooking the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popula ...

, the crucial main route to India which was then Britain's most important overseas possession. Following the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and the decision of the Ottoman Empire to join the war on the side of the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

, on 5 November 1914 the British Empire formally annexed Cyprus and declared the Ottoman ''Khedivate

The Khedivate of Egypt ( or , ; ota, خدیویت مصر ') was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which brou ...

'' of Egypt and Sudan a ''Sultanate'' and British protectorate.

In 1915, Britain offered Cyprus to Greece, ruled by King Constantine I of Greece

Constantine I ( el, Κωνσταντίνος Αʹ, ''Konstantínos I''; – 11 January 1923) was King of Greece from 18 March 1913 to 11 June 1917 and from 19 December 1920 to 27 September 1922. He was commander-in-chief of the Hellenic Army ...

, on condition that Greece join the war on the side of the British. The offer was declined. In 1923, under the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the confl ...

, the nascent Turkish republic relinquished any claim to Cyprus, and in 1925 it was declared a British crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Council ...

. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, many Greek and Turkish Cypriots enlisted in the Cyprus Regiment

The Cyprus Regiment was a military unit of the British Army. Created by the British Government during World War II, it was made up of volunteers from the Greek Cypriot, Turkish Cypriot, Armenian, Maronite and Latin inhabitants of Cyprus, but ...

.

The Greek Cypriot population, meanwhile, had become hopeful that the British administration would lead to ''enosis''. The idea of ''enosis'' was historically part of the '' Megali Idea'', a greater political ambition of a Greek state encompassing the territories with Greek inhabitants in the former Ottoman Empire, including Cyprus and Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

with a capital in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, and was actively pursued by the Cypriot Orthodox Church

The Church of Cyprus ( el, Ἐκκλησία τῆς Κύπρου, translit=Ekklisia tis Kyprou; tr, Kıbrıs Kilisesi) is one of the autocephalous Greek Orthodox churches that together with other Eastern Orthodox churches form the communion ...

, which had its members educated in Greece. These religious officials, together with Greek military officers and professionals, some of whom still pursued the '' Megali Idea'', would later found the guerrilla organisation ''Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston'' or National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA

The Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston (EOKA; ; el, Εθνική Οργάνωσις Κυπρίων Αγωνιστών, lit=National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters) was a Greek Cypriot nationalist paramilitary organisation that fought a cam ...

). The Greek Cypriots viewed the island as historically Greek and believed that union with Greece was a natural right. In the 1950s, the pursuit of ''enosis'' became a part of the Greek national policy.

Initially, the Turkish Cypriots favoured the continuation of the British rule. However, they were alarmed by the Greek Cypriot calls for ''enosis'', as they saw the union of

Initially, the Turkish Cypriots favoured the continuation of the British rule. However, they were alarmed by the Greek Cypriot calls for ''enosis'', as they saw the union of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

with Greece, which led to the exodus of Cretan Turks

The Cretan Muslims ( el, Τουρκοκρητικοί or , or ; tr, Giritli, , or ; ar, أتراك كريت) or Cretan Turks were the Muslim inhabitants of the island of Crete. Their descendants settled principally in Turkey, the Dodecanese ...

, as a precedent to be avoided, and they took a pro-partition stance in response to the militant activity of EOKA. The Turkish Cypriots also viewed themselves as a distinct ethnic group of the island and believed in their having a separate right to self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a '' jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It sta ...

from Greek Cypriots. Meanwhile, in the 1950s, Turkish leader Menderes considered Cyprus an "extension of Anatolia", rejected the partition of Cyprus along ethnic lines and favoured the annexation of the whole island to Turkey. Nationalistic slogans centred on the idea that "Cyprus is Turkish" and the ruling party declared Cyprus to be a part of the Turkish homeland that was vital to its security. Upon realising that the fact that the Turkish Cypriot population was only 20% of the islanders made annexation unfeasible, the national policy was changed to favour partition. The slogan "Partition or Death" was frequently used in Turkish Cypriot and Turkish protests starting in the late 1950s and continuing throughout the 1960s. Although after the Zürich and London conferences Turkey seemed to accept the existence of the Cypriot state and to distance itself from its policy of favouring the partition of the island, the goal of the Turkish and Turkish Cypriot leaders remained that of creating an independent Turkish state in the northern part of the island.

In January 1950, the Church of Cyprus organised a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

under the supervision of clerics and with no Turkish Cypriot participation, where 96% of the participating Greek Cypriots voted in favour of ''enosis'', The Greeks were 80.2% of the total island' s population at the time ( census 1946). Restricted autonomy under a constitution was proposed by the British administration but eventually rejected. In 1955 the EOKA organisation was founded, seeking union with Greece through armed struggle. At the same time the Turkish Resistance Organisation (TMT), calling for Taksim, or partition, was established by the Turkish Cypriots as a counterweight. British officials also tolerated the creation of the Turkish underground organisation T.M.T. The Secretary of State for the Colonies in a letter dated 15 July 1958 had advised the Governor of Cyprus not to act against T.M.T despite its illegal actions so as not to harm British relations with the Turkish government.

Independence and inter-communal violence

When Cyprus was placed under theUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

's administration based on the Cyprus Convention in 1878 and was formally annexed by the UK in 1914. The future of the island became a matter of disagreement between the two prominent ethnic communities, Greek Cypriots

Greek Cypriots or Cypriot Greeks ( el, Ελληνοκύπριοι, Ellinokýprioi, tr, Kıbrıs Rumları) are the ethnic Greek population of Cyprus, forming the island's largest ethnolinguistic community. According to the 2011 census, 659,115 ...

, who made up 77% of the population in 1960, and Turkish Cypriots, who made up 18% of the population. From the 19th century onwards, the Greek Cypriot population pursued ''enosis

''Enosis'' ( el, Ένωσις, , "union") is the movement of various Greek communities that live outside Greece for incorporation of the regions that they inhabit into the Greek state. The idea is related to the Megali Idea, an irredentist conc ...

'', union with Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

, which became a Greek national policy in the 1950s. The Turkish Cypriot population initially advocated the continuation of the British rule, then demanded the annexation of the island to Turkey, and in the 1950s, together with Turkey, established a policy of '' taksim'', the partition of Cyprus and the creation of a Turkish polity in the north. On 16 August 1960, Cyprus attained independence after the

On 16 August 1960, Cyprus attained independence after the Zürich and London Agreement

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Zür ...

between the United Kingdom, Greece and Turkey. Cyprus had a total population of 573,566; of whom 442,138 (77.1%) were Greeks, 104,320 (18.2%) Turks, and 27,108 (4.7%) others.Eric Solsten, ed. ''Cyprus: A Country Study'', Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1991. The UK retained the two

Sovereign Base Areas

Akrotiri and Dhekelia, officially the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia (SBA),, ''Periochés Kyríarchon Váseon Akrotiríou ke Dekélias''; tr, Ağrotur ve Dikelya İngiliz Egemen Üs Bölgeleri is a British Overseas Territory o ...

of Akrotiri and Dhekelia

Akrotiri and Dhekelia, officially the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia (SBA),, ''Periochés Kyríarchon Váseon Akrotiríou ke Dekélias''; tr, Ağrotur ve Dikelya İngiliz Egemen Üs Bölgeleri is a British Overseas Territory o ...

, while government posts and public offices were allocated by ethnic quotas, giving the minority Turkish Cypriots a permanent veto, 30% in parliament and administration, and granting the three mother-states guarantor rights.

However, the division of power as foreseen by the constitution soon resulted in legal impasses and discontent on both sides, and nationalist militants started training again, with the military support of Greece and Turkey respectively. The Greek Cypriot leadership believed that the rights given to Turkish Cypriots under the 1960 constitution were too extensive and designed the Akritas plan

The Akritas plan ( el, Σχέδιο Ακρίτας), was an inside document of the Greek Cypriot secret organisation of EOK (mostly known as Akritas organisation) that was authored in 1963 and was revealed to the public in 1966. It entailed the we ...

, which was aimed at reforming the constitution in favour of Greek Cypriots, persuading the international community about the correctness of the changes and violently subjugating Turkish Cypriots in a few days should they not accept the plan.Eric Solsten, ed. ''Cyprus: A Country Study'', Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1991. Tensions were heightened when Cypriot President Archbishop Makarios III called for constitutional changes, which were rejected by Turkey and opposed by Turkish Cypriots. Intercommunal violence erupted on 21 December 1963, when two Turkish Cypriots were killed at an incident involving the Greek Cypriot police. The violence resulted in the death of 364 Turkish and 174 Greek Cypriots,Oberling, Pierre. ''The road to Bellapais'' (1982), Social Science Monographs

p. 120

"According to official records, 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots were killed during the 1963–1964 crisis." destruction of 109 Turkish Cypriot or mixed villages and displacement of 25,000–30,000 Turkish Cypriots. The crisis resulted in the end of the Turkish Cypriot involvement in the administration and their claiming that it had lost its legitimacy; the nature of this event is still controversial. In some areas, Greek Cypriots prevented Turkish Cypriots from travelling and entering government buildings, while some Turkish Cypriots willingly withdrew due to the calls of the Turkish Cypriot administration. Turkish Cypriots started living in

enclaves

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

. The republic's structure was changed, unilaterally, by Makarios, and Nicosia was divided by the Green Line, with the deployment of UNFICYP

The United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) is a United Nations peacekeeping force that was established under United Nations Security Council Resolution 186 in 1964 to prevent a recurrence of fighting following intercommunal violen ...

troops.

In 1964, Turkey threatened to invade Cyprus in response to the continuing Cypriot intercommunal violence, but this was stopped by a strongly worded telegram from the US President Lyndon B. Johnson on 5 June, warning that the US would not stand beside Turkey in case of a consequential Soviet invasion of Turkish territory. Meanwhile, by 1964, ''enosis'' was a Greek policy and would not be abandoned; Makarios and the Greek prime minister Georgios Papandreou agreed that ''enosis'' should be the ultimate aim and King Constantine wished Cyprus "a speedy union with the mother country". Greece dispatched 10,000 troops to Cyprus to counter a possible Turkish invasion.

Following nationalist violence in the 1950s, Cyprus was granted independence in 1960.Cyprus date of independence(click on Historical review) The crisis of 1963–64 brought further intercommunal violence between the two communities, displaced more than 25,000 Turkish Cypriots into

enclaves

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

and brought the end of Turkish Cypriot representation in the republic. On 15 July 1974, a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

was staged by Greek Cypriot nationalists and elements of the Greek military junta in an attempt at ''enosis''. This action precipitated the Turkish invasion of Cyprus

The Turkish invasion of Cyprus began on 20 July 1974 and progressed in two phases over the following month. Taking place upon a background of intercommunal violence between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, and in response to a Greek junta-s ...

on 20 July, which led to the capture of the present-day territory of Northern Cyprus

Northern Cyprus ( tr, Kuzey Kıbrıs), officially the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC; tr, Kuzey Kıbrıs Türk Cumhuriyeti, ''KKTC''), is a '' de facto'' state that comprises the northeastern portion of the island of Cyprus. Rec ...

and the displacement of over 150,000 Greek Cypriots and 50,000 Turkish Cypriots. A separate Turkish Cypriot state in the north was established by unilateral declaration in 1983; the move was widely condemned by the international community

The international community is an imprecise phrase used in geopolitics and international relations to refer to a broad group of people and governments of the world.

As a rhetorical term

Aside from its use as a general descriptor, the term is t ...