Battle of the Netherlands on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The German invasion of the Netherlands ( nl, Duitse aanval op Nederland), otherwise known as the Battle of the Netherlands ( nl, Slag om Nederland), was a military campaign part of

The

The  International tensions grew in the late 1930s. Crises were caused by the German

International tensions grew in the late 1930s. Crises were caused by the German

In the Netherlands, all the objective conditions were present for a successful defence: a dense population, wealthy, young, disciplined and well-educated; a geography favouring the defender; and a strong technological and industrial base including an armaments industry. However, these had not been exploited: while the

In the Netherlands, all the objective conditions were present for a successful defence: a dense population, wealthy, young, disciplined and well-educated; a geography favouring the defender; and a strong technological and industrial base including an armaments industry. However, these had not been exploited: while the

In the 17th century, the

In the 17th century, the

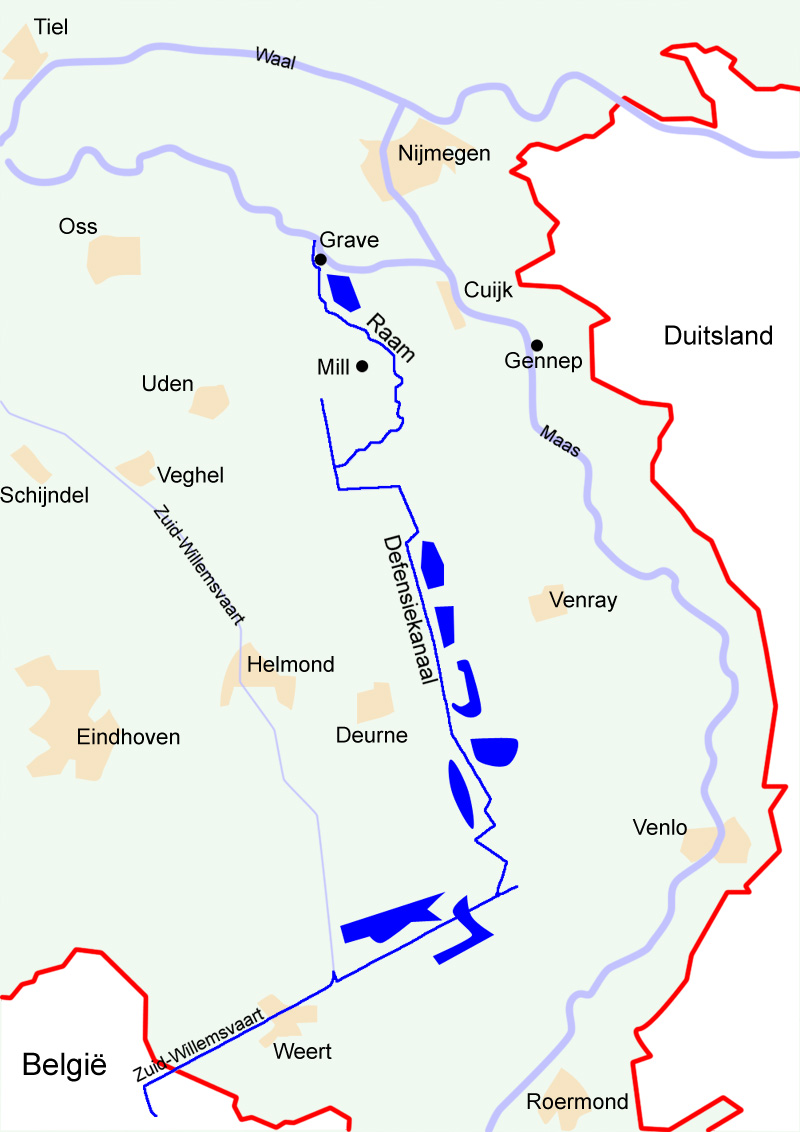

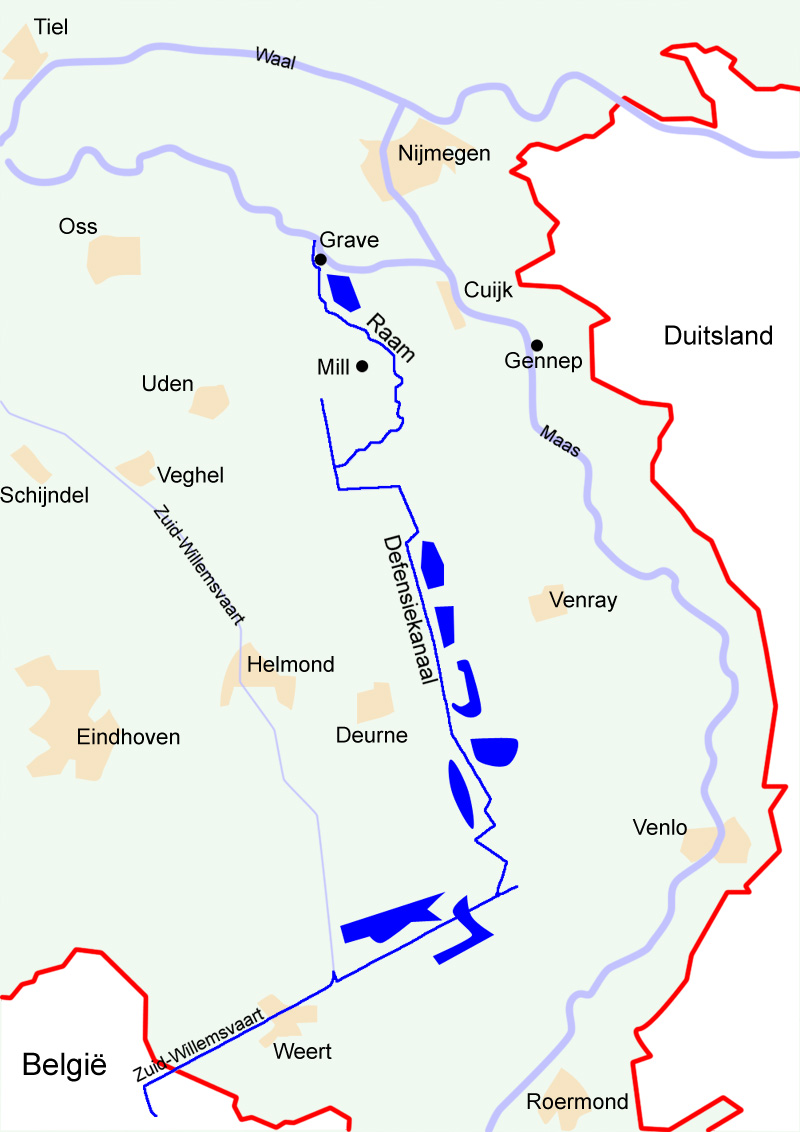

In front of this Main Defence Line was the ''IJssel-Maaslinie'', a covering line along the rivers

In front of this Main Defence Line was the ''IJssel-Maaslinie'', a covering line along the rivers

To ensure a victory the Germans resorted to unconventional means. The Germans had trained two airborne/airlanding assault divisions. The first of these, the '' 7. Flieger-Division'', consisted of paratroopers; the second, the 22nd ''Luftlande-Infanteriedivision'', of airborne infantry. Initially the plan was that the main German assault was to take place in

To ensure a victory the Germans resorted to unconventional means. The Germans had trained two airborne/airlanding assault divisions. The first of these, the '' 7. Flieger-Division'', consisted of paratroopers; the second, the 22nd ''Luftlande-Infanteriedivision'', of airborne infantry. Initially the plan was that the main German assault was to take place in

On the morning of 10 May 1940 the Dutch awoke to the sound of

On the morning of 10 May 1940 the Dutch awoke to the sound of  The attack on The Hague ended in operational failure. The paratroopers were unable to capture the main airfield at

The attack on The Hague ended in operational failure. The paratroopers were unable to capture the main airfield at  The attack on Rotterdam was much more successful. Twelve

The attack on Rotterdam was much more successful. Twelve  The Germans, executing a plan approved by Hitler, tried to capture the IJssel and Maas bridges intact, using commando teams of ''

The Germans, executing a plan approved by Hitler, tried to capture the IJssel and Maas bridges intact, using commando teams of '' Even before the armoured train arrived, the Dutch 3rd Army Corps had already been planned to be withdrawn from behind the Peel-Raam Position, taking with it all the artillery apart from 36 ''8 Staal'' pieces. Each of its six regiments was to leave a battalion behind to serve as a covering force, together with fourteen "border battalions". The group was called the "Peel Division". This withdrawal was originally planned for the first night after the invasion, under cover of darkness, but due to the rapid German advance an immediate retreat was ordered at 06:45, to avoid the 3rd Army Corps becoming entangled with enemy troops. The corps joined "Brigade G", six battalions already occupying the Waal-Linge line, and was thus brought up to strength again. It would see no further fighting.

The Light Division, based at

Even before the armoured train arrived, the Dutch 3rd Army Corps had already been planned to be withdrawn from behind the Peel-Raam Position, taking with it all the artillery apart from 36 ''8 Staal'' pieces. Each of its six regiments was to leave a battalion behind to serve as a covering force, together with fourteen "border battalions". The group was called the "Peel Division". This withdrawal was originally planned for the first night after the invasion, under cover of darkness, but due to the rapid German advance an immediate retreat was ordered at 06:45, to avoid the 3rd Army Corps becoming entangled with enemy troops. The corps joined "Brigade G", six battalions already occupying the Waal-Linge line, and was thus brought up to strength again. It would see no further fighting.

The Light Division, based at

In Rotterdam, though reinforced by an infantry regiment, the Dutch failed to completely dislodge the German airborne troops from their bridgehead on the northern bank of the Maas. Despite permission from General

In Rotterdam, though reinforced by an infantry regiment, the Dutch failed to completely dislodge the German airborne troops from their bridgehead on the northern bank of the Maas. Despite permission from General

While the situation in the south was becoming critical, in the east the Germans made a first successful effort in dislodging the Dutch defenders on the ''Grebbeberg''. After preparatory artillery bombardment in the morning, at around noon a battalion of ''Der Fuehrer'' attacked an eight hundred metres wide sector of the main line, occupied by a Dutch company. Exploiting the many dead angles in the Dutch field of fire, it soon breached the Dutch positions, which had little depth.Amersfoort (2005), p. 282 A second German battalion then expanded the breach to the north. Dutch artillery, though equal in strength to the German, failed to bring sufficient fire on the enemy concentration of infantry, largely limiting itself to interdiction. Eight hundred metres to the west was a Stop Line, a continuous trench system from which the defenders were supposed to wage an active defence, staging local counterattacks. However, due to a lack of numbers, training, and heavy weapons the attacks failed against the well-trained SS troops. By the evening the Germans had brought the heavily forested area between the two lines under their control. Spotting a weak point, one of the SS battalion commanders,

While the situation in the south was becoming critical, in the east the Germans made a first successful effort in dislodging the Dutch defenders on the ''Grebbeberg''. After preparatory artillery bombardment in the morning, at around noon a battalion of ''Der Fuehrer'' attacked an eight hundred metres wide sector of the main line, occupied by a Dutch company. Exploiting the many dead angles in the Dutch field of fire, it soon breached the Dutch positions, which had little depth.Amersfoort (2005), p. 282 A second German battalion then expanded the breach to the north. Dutch artillery, though equal in strength to the German, failed to bring sufficient fire on the enemy concentration of infantry, largely limiting itself to interdiction. Eight hundred metres to the west was a Stop Line, a continuous trench system from which the defenders were supposed to wage an active defence, staging local counterattacks. However, due to a lack of numbers, training, and heavy weapons the attacks failed against the well-trained SS troops. By the evening the Germans had brought the heavily forested area between the two lines under their control. Spotting a weak point, one of the SS battalion commanders,  In the afternoon General Winkelman received information about armoured forces advancing in the Langstraat region, on the road between 's-Hertogenbosch and the Moerdijk bridges. He still fostered hopes that those forces were French, but the announcement by Radio

In the afternoon General Winkelman received information about armoured forces advancing in the Langstraat region, on the road between 's-Hertogenbosch and the Moerdijk bridges. He still fostered hopes that those forces were French, but the announcement by Radio

In the early morning of 13 May General Winkelman advised the Dutch government that he considered the general situation to be critical. On land the Dutch had been cut off from the Allied front and it had become clear no major Allied landings were to be expected to reinforce the Fortress Holland by sea; without such support there was no prospect of a prolonged successful resistance. German tanks might quickly pass through Rotterdam; Winkelman had already ordered all available antitank-guns to be placed in a perimeter around The Hague, to protect the seat of government. However, an immediate collapse of the Dutch defences might still be prevented if the planned counterattacks could seal off the southern front near Dordrecht and restore the eastern line at the Grebbeberg. Therefore, the cabinet decided to continue the fight for the time being, giving the general the mandate to surrender the Army when he saw fit and the instruction to avoid unnecessary sacrifices. Nevertheless, it was also deemed essential that Queen Wilhelmina be brought to safety; she departed around noon from

In the early morning of 13 May General Winkelman advised the Dutch government that he considered the general situation to be critical. On land the Dutch had been cut off from the Allied front and it had become clear no major Allied landings were to be expected to reinforce the Fortress Holland by sea; without such support there was no prospect of a prolonged successful resistance. German tanks might quickly pass through Rotterdam; Winkelman had already ordered all available antitank-guns to be placed in a perimeter around The Hague, to protect the seat of government. However, an immediate collapse of the Dutch defences might still be prevented if the planned counterattacks could seal off the southern front near Dordrecht and restore the eastern line at the Grebbeberg. Therefore, the cabinet decided to continue the fight for the time being, giving the general the mandate to surrender the Army when he saw fit and the instruction to avoid unnecessary sacrifices. Nevertheless, it was also deemed essential that Queen Wilhelmina be brought to safety; she departed around noon from  In Rotterdam a last attempt was made to blow up the Willemsbrug. The commander of the 2nd Battalion Irish Guards in Hook of Holland, to the west, refused to participate in the attempt as being outside the scope of his orders. Two Dutch companies, mainly composed of Dutch marines, stormed the bridgehead. The bridge was reached and the remaining fifty German defenders in the building in front of it were on the point of surrender when after hours of fighting the attack was abandoned because of heavy flanking fire from the other side of the river.

In the North, the commander of ''1. Kavalleriedivision'', Major General

In Rotterdam a last attempt was made to blow up the Willemsbrug. The commander of the 2nd Battalion Irish Guards in Hook of Holland, to the west, refused to participate in the attempt as being outside the scope of his orders. Two Dutch companies, mainly composed of Dutch marines, stormed the bridgehead. The bridge was reached and the remaining fifty German defenders in the building in front of it were on the point of surrender when after hours of fighting the attack was abandoned because of heavy flanking fire from the other side of the river.

In the North, the commander of ''1. Kavalleriedivision'', Major General  On the extreme south of the Grebbe Line, the Grebbeberg, the Germans were now deploying three SS battalions including support troops and three fresh infantry battalions of IR.322; two of IR.374 laid in immediate reserve. During the evening and night of 12–13 May the Dutch had assembled in this sector about a dozen battalions. These forces consisted of the reserve battalions of several army corps, divisions and brigades, and the independent Brigade B, which had been freed when the Main Defence Line in the

On the extreme south of the Grebbe Line, the Grebbeberg, the Germans were now deploying three SS battalions including support troops and three fresh infantry battalions of IR.322; two of IR.374 laid in immediate reserve. During the evening and night of 12–13 May the Dutch had assembled in this sector about a dozen battalions. These forces consisted of the reserve battalions of several army corps, divisions and brigades, and the independent Brigade B, which had been freed when the Main Defence Line in the

Despite his pessimism expressed to the Dutch government and the mandate he had been given to surrender the Army, General Winkelman awaited the outcome of events, avoiding actually capitulating until it was absolutely necessary. In this he was perhaps motivated by a desire to engage the opposing German troops for as long as possible, to assist the Allied war effort. In the early morning of 14 May, though the situation remained critical, a certain calm was evident in the Dutch Headquarters.

In the North, a German artillery bombardment of the Kornwerderzand Position began at 09:00. However, the German batteries were forced to move away after being surprised by counterfire from the 15 cm. aft cannon of , which had sailed into the

Despite his pessimism expressed to the Dutch government and the mandate he had been given to surrender the Army, General Winkelman awaited the outcome of events, avoiding actually capitulating until it was absolutely necessary. In this he was perhaps motivated by a desire to engage the opposing German troops for as long as possible, to assist the Allied war effort. In the early morning of 14 May, though the situation remained critical, a certain calm was evident in the Dutch Headquarters.

In the North, a German artillery bombardment of the Kornwerderzand Position began at 09:00. However, the German batteries were forced to move away after being surprised by counterfire from the 15 cm. aft cannon of , which had sailed into the  Generals Kurt Student and Schmidt desired a limited air attack to temporarily paralyse the defences, allowing the tanks to break out of the bridgehead; severe urban destruction was to be avoided as it would only hamper their advance. However, ''Luftwaffe'' commander

Generals Kurt Student and Schmidt desired a limited air attack to temporarily paralyse the defences, allowing the tanks to break out of the bridgehead; severe urban destruction was to be avoided as it would only hamper their advance. However, ''Luftwaffe'' commander  At 09:00 a German messenger crossed the ''Willemsbrug'' to bring an ultimatum from Schmidt to Colonel

At 09:00 a German messenger crossed the ''Willemsbrug'' to bring an ultimatum from Schmidt to Colonel

Winkelman at first intended to continue the fight, even though Rotterdam had capitulated and German forces from there might now advance into the heart of the Fortress Holland. The possibility of terror bombings was considered before the invasion and had not been seen as grounds for immediate capitulation; provisions had been made for the continuation of effective government even after widespread urban destruction. The perimeter around The Hague might still ward off an armoured attack and the New Holland Water Line had some defensive capability; though it could be attacked from behind, it would take the Germans some time to deploy their forces in the difficult polder landscape.Amersfoort (2005), p. 181

However, he soon received a message from Colonel

Winkelman at first intended to continue the fight, even though Rotterdam had capitulated and German forces from there might now advance into the heart of the Fortress Holland. The possibility of terror bombings was considered before the invasion and had not been seen as grounds for immediate capitulation; provisions had been made for the continuation of effective government even after widespread urban destruction. The perimeter around The Hague might still ward off an armoured attack and the New Holland Water Line had some defensive capability; though it could be attacked from behind, it would take the Germans some time to deploy their forces in the difficult polder landscape.Amersfoort (2005), p. 181

However, he soon received a message from Colonel  Winkelman acted both in his capacity of commander of the Dutch Army and of highest executive power of the homeland. This created a somewhat ambiguous situation. On the morning of 14 May the commander of the

Winkelman acted both in his capacity of commander of the Dutch Army and of highest executive power of the homeland. This created a somewhat ambiguous situation. On the morning of 14 May the commander of the

cbs.nl

History Site "War Over Holland – the Dutch struggle May 1940"

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Netherlands, German invasion of 1940 in the Netherlands Battles and operations of World War II involving the Netherlands Battle of France Battles of World War II involving France Battles of World War II involving Germany

Case Yellow

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

(german: Fall Gelb), the Nazi German

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

invasion of the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

(Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

, and the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

) and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The battle lasted from 10 May 1940 until the surrender of the main Dutch forces on 14 May. Dutch troops in the province of Zeeland

, nl, Ik worstel en kom boven("I struggle and emerge")

, anthem = "Zeeuws volkslied"("Zeelandic Anthem")

, image_map = Zeeland in the Netherlands.svg

, map_alt =

, m ...

continued to resist the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

'' until 17 May when Germany completed its occupation of the whole country.

The invasion of the Netherlands saw some of the earliest mass paratroop

A paratrooper is a military parachutist—someone trained to parachute into a military operation, and usually functioning as part of an airborne force. Military parachutists (troops) and parachutes were first used on a large scale during World ...

drops, to occupy tactical points and assist the advance of ground troops. The German ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' used paratroopers in the capture of several airfields in the vicinity of Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte'') is the second largest city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the province of South Holland, part of the North Sea mouth of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, via the ''"N ...

and The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

, helping to quickly overrun the country and immobilise Dutch forces.

After the devastating Nazi bombing of Rotterdam by the ''Luftwaffe'' on 14 May, the Germans threatened to bomb other Dutch cities if the Dutch forces refused to surrender. The General Staff knew it could not stop the bombers and ordered the Royal Netherlands Army

The Royal Netherlands Army ( nl, Koninklijke Landmacht) is the land branch of the Netherlands Armed Forces. Though the Royal Netherlands Army was raised on 9 January 1814, its origins date back to 1572, when the was raised – making the Dutc ...

to cease hostilities. The last occupied parts of the Netherlands were liberated in 1945.

Background

Prelude

The United Kingdom and France declared war on Germany in 1939, following theGerman invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

, but no major land operations occurred in Western Europe during the period known as the Phoney War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germa ...

in the winter of 1939–1940. During this time, the British and French built up their forces in expectation of a long war, and the Germans together with the Soviets completed their conquest of Poland. On 9 October, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

ordered plans to be made for an invasion of the Low Countries, to use them as a base against Great Britain and to pre-empt a similar attack by the Allied forces, which could threaten the vital Ruhr Area

The Ruhr ( ; german: Ruhrgebiet , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr area, sometimes Ruhr district, Ruhr region, or Ruhr valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 2,800/km ...

. A joint Dutch-Belgian peace offer between the two sides was rejected on 7 November.

The

The Netherlands Armed Forces

The Netherlands Armed Forces ( nl, Nederlandse krijgsmacht) are the military services of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The core of the armed forces consists of the four service branches: the Royal Netherlands Navy (), the Royal Netherlands ...

were ill-prepared to resist such an invasion. When Hitler came to power, the Dutch had begun to re-arm, but more slowly than France or Belgium; only in 1936 did the defence budget start to be gradually increased.Amersfoort (2005), p. 77 Successive Dutch governments tended to avoid openly identifying Germany as an acute military threat. Partly this was caused by a wish not to antagonise a vital trade partner, even to the point of repressing criticism of Nazi policies; partly it was made inevitable by a policy of strict budgetary limits with which the conservative Dutch governments tried in vain to fight the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, which hit Dutch society particularly hard.Amersfoort (2005), p. 67 Hendrikus Colijn

Hendrikus "Hendrik" Colijn (22 June 1869 – 18 September 1944) was a Dutch politician of the Anti-Revolutionary Party (ARP; now defunct and merged into the Christian Democratic Appeal or CDA). He served as Prime Minister of the Netherlands from ...

, prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

between 1933 and 1939, was personally convinced Germany would not violate Dutch neutrality; senior officers made no effort to mobilise public opinion in favour of improving military defence.

International tensions grew in the late 1930s. Crises were caused by the German

International tensions grew in the late 1930s. Crises were caused by the German occupation of the Rhineland

The Occupation of the Rhineland from 1 December 1918 until 30 June 1930 was a consequence of the collapse of the Imperial German Army in 1918, after which Germany's provisional government was obliged to agree to the terms of the 1918 armist ...

in 1936; the ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

'' and Sudeten crisis

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

of 1938; and the German occupation of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German occ ...

and the Italian invasion of Albania

The Italian invasion of Albania (April 7–12, 1939) was a brief military campaign which was launched by the Kingdom of Italy against the Albanian Kingdom in 1939. The conflict was a result of the imperialistic policies of the Italian prime m ...

in the spring of 1939. These events forced the Dutch government to exercise greater vigilance, but they limited their reaction as much as they could. The most important measure was a partial mobilisation of 100,000 men in April 1939.

After the German invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

in September 1939 and the ensuing outbreak of the Second World War, the Netherlands hoped to remain neutral, as they had done during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

25 years earlier. To ensure this neutrality, the Dutch army was mobilised from 24 August and entrenched. Large sums (almost 900 million guilder

Guilder is the English translation of the Dutch and German ''gulden'', originally shortened from Middle High German ''guldin pfenninc'' "gold penny". This was the term that became current in the southern and western parts of the Holy Roman Empir ...

s) were spent on defence. It proved very difficult to obtain new matériel in wartime, however, especially as the Dutch had ordered some of their new equipment from Germany, which deliberately delayed deliveries. Moreover, a considerable part of the funds were intended for the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

(now Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

), much of it related to a plan to build three battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

s.

The strategic position of the Low Countries, located between France and Germany on the uncovered flanks of their fortification lines, made the area a logical route for an offensive by either side. In a 20 January 1940 radio speech, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

tried to convince them not to wait for an inevitable German attack, but to join the Anglo-French Entente. Both the Belgians and Dutch refused, even though the German attack plans had fallen into Belgian hands after a German aircraft crash in January 1940, in what became known as the Mechelen Incident

The Mechelen incident of 10 January 1940, also known as the Mechelen affair, took place in Belgium during the Phoney War in the first stages of World War II. A German aircraft with an officer on board carrying the plans for ''Fall Gelb'' (Case Ye ...

.

The French supreme command considered violating the neutrality of the Low Countries if they had not joined the Anglo-French coalition before the planned large Entente offensive in the summer of 1941, but the French Cabinet, fearing a negative public reaction, vetoed the idea. Kept in consideration was a plan to invade if Germany attacked the Netherlands alone, necessitating an Entente advance through Belgium, or if the Netherlands assisted the enemy by tolerating a German advance into Belgium through the southern part of their territory, both possibilities discussed as part of the ''hypothèse Hollande''.Amersfoort (2005), p. 92 The Dutch government never officially formulated a policy on how to act in case of either contingency; the majority of ministers preferred to resist an attack, while a minority and Queen Wilhelmina refused to become a German ally whatever the circumstances. The Dutch tried on several occasions to act as an intermediary to reach a negotiated peace settlement between the Entente and Germany.

After the German invasion of Norway and Denmark, followed by a warning by the new Japanese naval attaché Captain Tadashi Maeda that a German attack on the Netherlands was certain, it became clear to the Dutch military that staying out of the conflict might prove impossible. They started to fully prepare for war, both mentally and physically. Dutch border troops were put on greater alert. Reports of the presumed actions of a Fifth Column

A fifth column is any group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. According to Harris Mylonas and Scott Radnitz, "fifth columns" are “domestic actors who work to un ...

in Scandinavia caused widespread fears that the Netherlands too had been infiltrated by German agents assisted by traitors. Countermeasures were taken against a possible assault on airfields and ports. On 19 April a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

was declared. However, most civilians still cherished the illusion that their country might be spared, an attitude that has since been described as a state of denial. The Dutch hoped that the restrained policy of the Entente and Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

during the First World War might be repeated and tried to avoid the attention of the Great Powers and a war in which they feared a loss of human life comparable to that of the previous conflict. On 10 April, Britain and France repeated their request that the Dutch enter the war on their side, but were again refused.

Dutch forces

Royal Netherlands Army

In the Netherlands, all the objective conditions were present for a successful defence: a dense population, wealthy, young, disciplined and well-educated; a geography favouring the defender; and a strong technological and industrial base including an armaments industry. However, these had not been exploited: while the

In the Netherlands, all the objective conditions were present for a successful defence: a dense population, wealthy, young, disciplined and well-educated; a geography favouring the defender; and a strong technological and industrial base including an armaments industry. However, these had not been exploited: while the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

at the time still had many shortcomings in equipment and training, the Dutch army, by comparison, was far less prepared for war. The myth of the general German equipment advantage over the opposing armies in the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

was in fact a reality in the case of the Battle of the Netherlands. Germany had a modern army with tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engin ...

s and dive bombers

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact through ...

(such as the Junkers Ju 87

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from ''Sturzkampfflugzeug'', "dive bomber") was a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Con ...

''Stuka''), while the Netherlands had an army whose armoured forces comprised only 39 armoured cars

Armored (or armoured) car or vehicle may refer to:

Wheeled armored vehicles

* Armoured fighting vehicle, any armed combat vehicle protected by armor

** Armored car (military), a military wheeled armored vehicle

* Armored car (valuables), an arm ...

and five tankette

A tankette is a tracked armoured fighting vehicle that resembles a small tank, roughly the size of a car. It is mainly intended for light infantry support and scouting.

s, and an air force in large part consisting of biplanes

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While a ...

. The Dutch government's attitude towards war was reflected in the state of the country's armed forces, which had not significantly expanded their equipment since before the First World War, and were inadequately armed even by the standards of 1918. An economic recession lasting from 1920 until 1927 and the general détente in international relations caused a limitation of the defence budget. In that decade, only 1.5 million guilders per annum was spent on equipment. Both in 1931 and 1933, commissions appointed to economise even further failed, because they concluded that the acceptable minimum had been reached and advised that a spending increase was urgently needed. Only in February 1936 was a bill passed creating a special 53.4 million guilder defence fund.

The lack of a trained manpower base, a large professional organisation, or sufficient matériel reserves precluded a swift expansion of Dutch forces. There was just enough artillery to equip the larger units: eight infantry divisions (combined in four Army Corps), one Light (i.e. motorised) Division and two independent brigades (Brigade A and Brigade B), each with the strength of half a division or five battalions. All other infantry combat unit troops were raised as light infantry battalions that were dispersed all over the territory to delay enemy movement. About two thousand pillboxes had been constructed, but in lines without any depth. Modern large fortresses like the Belgian stronghold of Eben Emael

Fort Eben-Emael (french: Fort d'Ében-Émael, ) is an inactive Belgian fortress located between Liège and Maastricht, on the Belgian-Dutch border, near the Albert Canal, outside the village of Ében-Émael. It was designed to defend Belgi ...

were nonexistent; the only modern fortification complex was that at Kornwerderzand

Kornwerderzand ( West Frisian: Koarnwertersân) is a village on the Afsluitdijk, a major dam in the Netherlands that links Friesland with North Holland.

Overview

Kornwerderzand is located approximately 4 kilometers from the coast of Friesland, on ...

, guarding the Afsluitdijk

The ''Afsluitdijk'' (; fry, Ofslútdyk; nds-nl, Ofsluutdiek; en, "Closure Dyke") is a major dam and causeway in the Netherlands. It was constructed between 1927 and 1932 and runs from Den Oever in North Holland province to the village of ...

. Total Dutch forces equalled 48 regiments of infantry as well as 22 infantry battalions for strategic border defence. In comparison, Belgium, despite a smaller and more aged male population, fielded 22 full divisions and the equivalent of 30 divisions when smaller units were included.

After September 1939, desperate efforts were made to improve the situation, but with very little result. Germany, for obvious reasons, delayed its deliveries; France was hesitant to equip an army that would not unequivocally take its side. The one abundant source of readily available weaponry, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, was inaccessible because the Dutch, contrary to most other nations, did not recognise the communist regime. An attempt in 1940 to procure Soviet armour captured by Finland failed.

On 10 May, the most conspicuous deficiency of the Dutch Army lay in its shortage of armour

Armour (British English) or armor (American English; see spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, especially direct contact weapons or projectiles during combat, or fr ...

.De Jong (1969b), p. 325 Whereas the other major participants all had a considerable armoured force, the Netherlands had not been able to obtain the minimum of 146 modern tanks (110 light, 36 medium) they had already considered necessary in 1937. A single Renault FT

The Renault FT (frequently referred to in post-World War I literature as the FT-17, FT17, or similar) was a French light tank that was among the most revolutionary and influential tank designs in history. The FT was the first production tank to ...

tank, for which just one driver had been trained and which had the sole task of testing antitank obstacles, had remained the only example of its kind and was no longer in service by 1940. There were two squadrons of armoured cars, each with a dozen Landsverk

:''This is about the origin of the family name Landsverk. For the Swedish heavy industry manufacturer, see AB Landsverk.''

Landsverk is the name of two forest farms located in the village of Lisleherad, in the municipality of Notodden, Norway

...

M36 or M38 vehicles. Another dozen DAF M39

The ''Pantserwagen'' M39 or DAF ''Pantrado'' 3 was a Dutch 6×4 armoured car produced in the late thirties for the Royal Dutch Army.

From 1935 the DAF automobile company designed several armoured fighting vehicles based on its innovative '' T ...

cars were in the process of being taken into service, some still having to be fitted with their main armament. A single platoon

A platoon is a military unit typically composed of two or more squads, sections, or patrols. Platoon organization varies depending on the country and the branch, but a platoon can be composed of 50 people, although specific platoons may range ...

of five Carden-Loyd Mark VI tankettes used by the Artillery completed the list of Dutch armour.

The Dutch Artillery had available a total of 676 howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

s and field gun

A field gun is a field artillery piece. Originally the term referred to smaller guns that could accompany a field army on the march, that when in combat could be moved about the battlefield in response to changing circumstances ( field artille ...

s: 310 Krupp

The Krupp family (see pronunciation), a prominent 400-year-old German dynasty from Essen, is notable for its production of steel, artillery, ammunition and other armaments. The family business, known as Friedrich Krupp AG (Friedrich Krup ...

75 mm field guns, partly produced in licence; 52 105 mm Bofors

AB Bofors ( , , ) is a former Swedish arms manufacturer which today is part of the British arms concern BAE Systems. The name has been associated with the iron industry and artillery manufacturing for more than 350 years.

History

Located in ...

howitzers, the only really modern pieces; 144 obsolete Krupp 125 mm guns; 40 150 mm sFH13's; 72 Krupp 150 mm L/24 howitzers and 28 Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public in 18 ...

152 mm L/15 howitzers. As antitank-guns 386 Böhler

Böhler, is an Austrian trader for special steel. Its multinational presence includes locations around the world, including the Americas, Europe, Asia and Africa.

Böhler concentrates in very specific grades of steel, requiring great strength, st ...

47 mm L/39s were available, which were effective weapons but too few in number, being only at a third of the planned strength; another three hundred antiquated ''6 Veld'' (57 mm) and 8 cm staal

The 8 cm staal is a 19th century Dutch field gun. It replaced the 8.4 cm Feldgeschütz Ord 1871, 8 cm A. bronze. The steel barrel and carriage were made by Krupp in Essen, Germany. In turn the 8 cm staal would be replaced by the Krupp 7. ...

(84 mm) field guns performed the same role for the covering forces. Only eight of the 120 modern 105 mm pieces ordered from Germany had been delivered at the time of the invasion

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

. Most artillery was horse-drawn.De Jong (1969b), p. 327

The Dutch Infantry used about 2,200 7.92 mm Schwarzlose M.08 machine guns, partly licence produced, and eight hundred Vickers machine gun

The Vickers machine gun or Vickers gun is a Water cooling, water-cooled .303 British (7.7 mm) machine gun produced by Vickers Limited, originally for the British Army. The gun was operated by a three-man crew but typically required more me ...

s. Many of these were fitted in the pillboxes; each battalion had a heavy machine gun company of twelve. The Dutch infantry squads were equipped with an organic light machine gun, the M.20 Lewis machine gun, of which about eight thousand were available. Most Dutch infantry were equipped with the Geweer M.95 rifle, adopted in 1895.Nederlandse Vuurwapens: Landmacht en Luchtvaartafdeling, drs G. de Vries & drs B.J. Martens, p.40-56 There were but six 80 mm mortars

Mortar may refer to:

* Mortar (weapon), an indirect-fire infantry weapon

* Mortar (masonry), a material used to fill the gaps between blocks and bind them together

* Mortar and pestle, a tool pair used to crush or grind

* Mortar, Bihar, a villag ...

for each regiment. This lack of firepower

Firepower is the military capability to direct force at an enemy. (It is not to be confused with the concept of rate of fire, which describes the cycling of the firing mechanism in a weapon system.) Firepower involves the whole range of potent ...

seriously impaired the fighting performance of the Dutch infantry.

Despite the Netherlands being the seat of Philips

Koninklijke Philips N.V. (), commonly shortened to Philips, is a Dutch multinational conglomerate corporation that was founded in Eindhoven in 1891. Since 1997, it has been mostly headquartered in Amsterdam, though the Benelux headquarters i ...

, one of Europe's largest producers of radio equipment, the Dutch army mostly used telephone connections; only the Artillery had been equipped with the modest number of 225 radio sets.

Dutch Air Forces

TheDutch air force

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march = ''Parade March of the Royal Netherlands Air Force''

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, equipment ...

, which was not an independent arm of the Dutch armed forces, but part of the Army, on 10 May operated a fleet of 155 aircraft: 28 Fokker G.1

The Fokker G.I was a Dutch twin-engined heavy fighter aircraft comparable in size and role to the German Messerschmitt Bf 110. Although in production prior to World War II, its combat introduction came at a time the Netherlands were overrun by t ...

twin-engine destroyers; 31 Fokker D.XXI

The Fokker D.XXI fighter was designed in 1935 by Dutch aircraft manufacturer Fokker in response to requirements laid out by the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army Air Force (''Militaire Luchtvaart van het Koninklijk Nederlands-Indisch Leger'', ML ...

and seven Fokker D.XVII

Fokker D.XVII (sometimes written as Fokker D.17), was a 1930s Dutch sesquiplane developed by Fokker. It was the last fabric-covered biplane fighter they developed in a lineage that extended back to the First World War Fokker D.VII.

Design and d ...

fighters; ten twin-engined Fokker T.V

The Fokker T.V was a twin-engine bomber, described as an "aerial cruiser", built by Fokker for the Netherlands Air Force.

Modern for its time, by the Battle of the Netherlands, German invasion of 1940 it was outclassed by the airplanes of the '' ...

, fifteen Fokker C.X

The Fokker C.X was a Dutch biplane scout and light bomber designed in 1933. It had a crew of two (a pilot and an observer).

Design and development

The Fokker C.X was originally designed for the Royal Dutch East Indies Army, in order to replac ...

and 35 Fokker C.V

The Fokker C.V was a Dutch light reconnaissance and bomber biplane aircraft manufactured by Fokker. It was designed by Anthony Fokker and the series manufacture began in 1924 at Fokker in Amsterdam.

Development

The C.V was constructed in the earl ...

light bombers, twelve Douglas DB-8

Douglas may refer to:

People

* Douglas (given name)

* Douglas (surname)

Animals

*Douglas (parrot), macaw that starred as the parrot ''Rosalinda'' in Pippi Longstocking

*Douglas the camel, a camel in the Confederate Army in the American Civil ...

dive bombers (used as fighters) and seventeen Koolhoven FK-51 reconnaissance aircraft—thus 74 of the 155 aircraft were biplanes. Of these aircraft 125 were operational. Of the remainder the air force school used three Fokker D.XXI, six Fokker D.XVII, a single Fokker G.I

The Fokker G.I was a Dutch twin-engined heavy fighter aircraft comparable in size and role to the German Messerschmitt Bf 110. Although in production prior to World War II, its combat introduction came at a time the Netherlands were overrun by t ...

, a single Fokker T.V and seven Fokker C.V, along with several training aeroplanes. Another forty operational aircraft served with the Marineluchtvaartdienst (naval air service) along with about an equal number of reserve and training craft. The production potential of the Dutch military aircraft industry, consisting of Fokker

Fokker was a Dutch aircraft manufacturer named after its founder, Anthony Fokker. The company operated under several different names. It was founded in 1912 in Berlin, Germany, and became famous for its fighter aircraft in World War I. In 1919 ...

and Koolhoven

N.V. Koolhoven was an aircraft manufacturer based in Rotterdam, Netherlands. From its conception in 1926 to its destruction in the Blitzkrieg in May 1940, the company remained the second major Dutch aircraft manufacturer (after Fokker). Althoug ...

, was not fully exploited due to budget limitations.

Training and readiness

Not only was theRoyal Netherlands Army

The Royal Netherlands Army ( nl, Koninklijke Landmacht) is the land branch of the Netherlands Armed Forces. Though the Royal Netherlands Army was raised on 9 January 1814, its origins date back to 1572, when the was raised – making the Dutc ...

poorly equipped, it was also poorly trained. There had especially been little experience gained in the handling of larger units above the battalion level. From 1932 until 1936, the Dutch Army did not hold summer field manoeuvres in order to conserve military funding. Also, the individual soldier lacked many necessary skills. Before the war only a minority of young men eligible to serve in the military had actually been conscripted. Until 1938, those who were enlisted only served for 24 weeks, just enough to receive basic infantry training. That same year, service time was increased to eleven months. The low quality of conscripts was not compensated by a large body of professional military personnel. In 1940, there were only 1206 professional officers present. It had been hoped that when war threatened, these deficiencies could be quickly remedied but following the mobilisation of all Dutch forces on 28 August 1939 (bringing Army strength to about 280,000 men) readiness only slowly improved: most available time was spent constructing defences. During this period, munition shortages limited live fire training, while unit cohesion remained low. By its own standards the Dutch Army in May 1940 was unfit for battle. It was incapable of staging an offensive, even at division level, while executing manoeuvre warfare was far beyond its capacities.

German generals and tacticians (along with Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

himself) had an equally low opinion of the Dutch military and expected that the core region of Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former province on the western coast of the Netherlands. From the 10th to the 16th c ...

proper could be conquered in about three to five days.Amersfoort (2005), p. 188

Dutch defensive strategy

In the 17th century, the

In the 17th century, the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

had devised a defensive system called the Hollandic Water Line

The Dutch Waterline ( nl, Hollandsche Waterlinie, modern spelling: ''Hollandse Waterlinie'') was a series of water-based defences conceived by Maurice of Nassau in the early 17th century, and realised by his half brother Frederick Henry. Combine ...

, which during the Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War (french: Guerre de Hollande; nl, Hollandse Oorlog), was fought between France and the Dutch Republic, supported by its allies the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-Nor ...

protected all major cities in the west, by flooding part of the countryside. In the early 19th century this line was shifted somewhat to the east, beyond Utrecht

Utrecht ( , , ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city and a List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, capital and most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, pro ...

, and later modernised with fortresses. This new position was called the New Hollandic Water Line. The line was reinforced with new pillboxes in 1940 as the fortifications were outdated. The line was located at the extreme eastern edge of the area lying below sea level. This allowed the ground before the fortifications to be easily inundated with a few feet of water, too shallow for boats, but deep enough to turn the soil into an impassable quagmire. The area west of the New Hollandic Water Line was called Fortress Holland

The German invasion of the Netherlands ( nl, Duitse aanval op Nederland), otherwise known as the Battle of the Netherlands ( nl, Slag om Nederland), was a military campaign part of Case Yellow (german: Fall Gelb), the Nazi German invasion of t ...

(Dutch: ''Vesting Holland''; German: ''Festung Holland''), the eastern flank of which was also covered by Lake IJssel and the southern flank protected by the lower course of three broad parallel rivers: the Meuse

The Meuse ( , , , ; wa, Moûze ) or Maas ( , ; li, Maos or ) is a major European river, rising in France and flowing through Belgium and the Netherlands before draining into the North Sea from the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta. It has a t ...

(''Maas'') and two branches of the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

. It functioned as a National Redoubt, which was expected to hold out a prolonged period of time,Amersfoort (2005), p. 84 in the most optimistic predictions as much as three months without any allied assistance, even though the size of the attacking German force was strongly overestimated. Before the war the intention was to fall back to this position almost immediately, after a concentration phase (the so-called ''Case Blue'') in the Gelderse Vallei, inspired by the hope that Germany would only travel through the southern provinces on its way to Belgium and leave Holland proper untouched. In 1939 it was understood such an attitude posed an invitation to invade and made it impossible to negotiate with the Entente about a common defence. Proposals by German diplomats that the Dutch government would secretly assent to an advance into the country were rejected.

From September 1939 a more easterly Main Defence Line (MDL) was constructed. This second main defensive position had a northern part formed by the ''Grebbelinie'' ( Grebbe line), located at the foothills of the Utrechtse Heuvelrug

Utrechtse Heuvelrug (; en, "Utrecht Hill Ridge") is a municipality in the Netherlands, in the province of Utrecht. It was formed on 1 January 2006 by merging the former municipalities of Amerongen, Doorn, Driebergen-Rijsenburg, Leersum, and Maarn ...

, an Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gree ...

moraine

A moraine is any accumulation of unconsolidated debris (regolith and rock), sometimes referred to as glacial till, that occurs in both currently and formerly glaciated regions, and that has been previously carried along by a glacier or ice shee ...

between Lake IJssel and the Lower Rhine. It was dug on instigation of the commander of the Field Army Lieutenant-General Jan Joseph Godfried baron van Voorst tot Voorst

Jan Joseph Godfried, Baron van Voorst tot Voorst Jr. (29 December 1880 – 11 November 1963) was the second highest officer in command of the Dutch armed forces during World War II and a renowned strategist, who wrote numerous articles an ...

.Amersfoort (2005), p. 87 This line was extended by a southern part: the ''Peel-Raamstelling'' (Peel-Raam Position), located between the Maas and the Belgian border along the Peel Marshes

De Peel is a region in the southeast of the Netherlands that straddles the border between the provinces of North Brabant and Limburg.

The region is best known for the extraction of peat for fuel, which had been going on since the Middle Ages ...

and the Raam River

The Raam is a small river in the eastern part of North Brabant, Netherlands. It flows into the Meuse ( nl, Maas) at the old town Grave

A grave is a location where a dead body (typically that of a human, although sometimes that of an animal ...

, as ordered by the Dutch Commander in Chief, General Izaak H. Reijnders

Izaak Herman Reijnders (27 March 1879 – 31 December 1966) was in charge of the Dutch military high command just prior to World War II. He was replaced by Henri Winkelman after Reijnders had had an argument with Defense Minister Adriaan Di ...

. In the south the intention was to delay the Germans as much as possible to cover a French advance. Fourth and Second Army Corps were positioned at the Grebbe Line; Third Army Corps were stationed at the Peel-Raam Position with the Light Division behind it to cover its southern flank. Brigade A and B were positioned between the Lower Rhine and the Maas. First Army Corps was a strategic reserve in the Fortress Holland, the southern perimeter of which was manned by another ten battalions and the eastern by six battalions. All these lines were reinforced by pillboxes.

Positioning of troops

In front of this Main Defence Line was the ''IJssel-Maaslinie'', a covering line along the rivers

In front of this Main Defence Line was the ''IJssel-Maaslinie'', a covering line along the rivers IJssel

The IJssel (; nds-nl, Iessel(t) ) is a Dutch distributary of the river Rhine that flows northward and ultimately discharges into the IJsselmeer (before the 1932 completion of the Afsluitdijk known as the Zuiderzee), a North Sea natural harbour ...

and Meuse

The Meuse ( , , , ; wa, Moûze ) or Maas ( , ; li, Maos or ) is a major European river, rising in France and flowing through Belgium and the Netherlands before draining into the North Sea from the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta. It has a t ...

(''Maas''), connected by positions in the Betuwe

Batavia (; , ) is a historical and geographical region in the Netherlands, forming large fertile islands in the river delta formed by the waters of the Rhine (Dutch: ''Rijn'') and Meuse (Dutch: ''Maas'') rivers. During the Roman empire, it was an ...

, again with pillboxes and lightly occupied by a screen of fourteen "border battalions". Late in 1939 General Van Voorst tot Voorst, reviving plans he had already worked out in 1937, proposed to make use of the excellent defensive opportunities these rivers offered. He proposed a shift to a more mobile strategy by fighting a delaying battle at the plausible crossing sites near Arnhem

Arnhem ( or ; german: Arnheim; South Guelderish: ''Èrnem'') is a city and municipality situated in the eastern part of the Netherlands about 55 km south east of Utrecht. It is the capital of the province of Gelderland, located on both banks of ...

and Gennep

Gennep () is a municipality and a city in upper southeastern Netherlands. It lies in the very northern part of the province of Limburg, 18 km south of Nijmegen. Furthermore, it lies on the right bank of the Meuse river, and south of the forest ...

to force the German divisions to spend much of their offensive power before they had reached the MDL, and ideally even defeat them. This was deemed too risky by the Dutch government and General Reijnders. The latter wanted the army to first offer heavy resistance at the Grebbe Line and Peel-Raam Position, and then fall back to the Fortress Holland. This also was considered too dangerous by the government, especially in light of German air supremacy, and had the disadvantage of having to fully prepare two lines. Reijnders had already been denied full military authority in the defence zones; the conflict about strategy further undermined his political position. On 5 February 1940 he was forced to offer his resignation because of these disagreements with his superiors. He was replaced by General Henry G. Winkelman who decided that in the north the Grebbe Line would be the main defence line where the decisive battle was to be waged, partly because it would there be easier to break out with a counteroffensive

In the study of military tactics, a counter-offensive is a large-scale strategic offensive military operation, usually by forces that had successfully halted the enemy's offensive, while occupying defensive positions.

The counter-offensive i ...

if the conditions were favourable. However, he took no comparable decision regarding the Peel-Raam Position.

During the Phoney War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germa ...

the Netherlands officially adhered to a policy of strict neutrality. In secret, the Dutch military command, partly acting on its own accord, negotiated with both Belgium and France via the Dutch military attaché in Paris, Lieutenant-Colonel David van Voorst Evekink

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

to co-ordinate a common defence to a German invasion. This failed because of insurmountable differences of opinion about the question of which strategy to follow.

Coordinating with Belgium

Given its obvious strategic importance, Belgium, though in principle neutral, had already made quite detailed arrangements for co-ordination with Entente troops. This made it difficult for the Dutch to have these plans changed again to suit their wishes. The Dutch desired the Belgians to connect their defences to the Peel-Raam Position, that Reijnders refused to abandon without a fight. He did not approve of a plan by Van Voorst tot Voorst to occupy a so-called "Orange Position" on the much shorter line 's-Hertogenbosch –Tilburg

Tilburg () is a city and municipality in the Netherlands, in the southern province of North Brabant. With a population of 222,601 (1 July 2021), it is the second-largest city or municipality in North Brabant after Eindhoven and the seventh-larg ...

, to form a continuous front with the Belgian lines near Turnhout

Turnhout () is a Belgium, Belgian Municipalities in Belgium, municipality and city located in the Flemish Region, Flemish Provinces of Belgium, province of Antwerp (province), Antwerp. The municipality comprises only the city of Turnhout proper. ...

as proposed by Belgian General Raoul Van Overstraeten

Raoul François Casimir Van Overstraeten (Ath, 29 January 1885—Brussels, 30 January 1977) was a Belgian general who fought during the First World War and Second World War and, from 1938 to 1940, military adviser of king Leopold III of Belgium.

...

.

When Winkelman took over command, he intensified the negotiations, proposing on 21 February that Belgium would man a connecting line with the Peel-Raam Position along the Belgian part of the Zuid-Willemsvaart

The Zuid-Willemsvaart (; translated: ''South William's Canal'') is a canal in the south of the Netherlands and the east of Belgium.

Route

The Zuid-Willemsvaart is a canal in the provinces Limburg (Netherlands), Limburg (Belgium) and North Br ...

. The Belgians refused to do this unless the Dutch reinforced their presence in Limburg

Limburg or Limbourg may refer to:

Regions

* Limburg (Belgium), a province since 1839 in the Flanders region of Belgium

* Limburg (Netherlands), a province since 1839 in the south of the Netherlands

* Diocese of Limburg, Roman Catholic Diocese in ...

; the Dutch had no forces available with which to fulfill this request. Repeated Belgian requests to reconsider the Orange Position were refused by Winkelman. Therefore, the Belgians decided to withdraw, in the event of an invasion, all their troops to their main defence line, the Albert Canal

The Albert Canal (, ) is a canal located in northeastern Belgium, which was named for King Albert I of Belgium. The Albert Canal connects Antwerp with Liège, and also the Meuse river with the Scheldt river. It also connects with the Dessel� ...

. This created a dangerous gap forty kilometres wide. The French were invited to fill it. The French Commander in Chief General Maurice Gamelin

Maurice Gustave Gamelin (, 20 September 1872 – 18 April 1958) was an army general in the French Army. Gamelin is remembered for his disastrous command (until 17 May 1940) of the French military during the Battle of France (10 May–22 June 1940 ...

was more than interested in including the Dutch in his continuous front as — like Major-General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and t ...

four years later — he hoped to circle around the ''Westwall

The Siegfried Line, known in German as the ''Westwall'', was a German defensive line built during the 1930s (started 1936) opposite the French Maginot Line. It stretched more than ; from Kleve on the border with the Netherlands, along the wes ...

'' when the Entente launched its planned 1941 offensive. But he did not dare to stretch his supply lines that far unless the Belgians and Dutch would take the allied side before the German attack. When both nations refused, Gamelin made it clear that he would occupy a connecting position near Breda

Breda () is a city and municipality in the southern part of the Netherlands, located in the province of North Brabant. The name derived from ''brede Aa'' ('wide Aa' or 'broad Aa') and refers to the confluence of the rivers Mark and Aa. Breda has ...

. The Dutch did not fortify this area. In secret, Winkelman decided on 30 March to abandon the Peel-Raam Position immediately at the onset of a German attack and withdraw his Third Army Corps to the Linge

The Linge is a river in the Betuwe that is 99.8 km long, which makes it one of the longest rivers that flow entirely within the Netherlands.

It starts near the village Doornenburg near the German border. A legend tells us that if there w ...

to cover the southern flank of the Grebbe Line, leaving only a covering force behind. This Waal-Linge Position was to be reinforced with pillboxes; the budget for such structures was increased with a hundred million guilders.

After the German attack on Denmark and Norway in April 1940, when the Germans used large numbers of airborne troops

Airborne forces, airborne troops, or airborne infantry are ground combat units carried by aircraft and airdropped into battle zones, typically by parachute drop or air assault. Parachute-qualified infantry and support personnel serving in a ...

, the Dutch command became worried about the possibility they too could become the victim of such a strategic assault. To repulse an attack, five infantry battalions were positioned at the main ports and airbases, such as The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

airfield of Ypenburg

Leidschenveen-Ypenburg () is a Vinex-location and district of The Hague, located in the southeast. It is geographically connected to the main body of the city by only a narrow corridor. It consists of four quarters: Hoornwijk and Ypenburg on the ...

and the Rotterdam airfield of Waalhaven

Waalhaven Airport in 1932, with the Graf Zeppelin in the background.

The Waalhaven is a harbour in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. It used to be home to an airport, Vliegveld Waalhaven (Waalhaven Airport). It was the second civilian airport in the ...

. These were reinforced by additional AA-guns, two tankettes and twelve of the 24 operational armoured cars. These specially directed measures were accompanied by more general ones: the Dutch had posted no less than 32 hospital ship

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or near war zones. ...

s throughout the country and fifteen trains to help make troop movements easier.

French strategy

In addition to the Dutch Army and theGerman 18th Army

The 18th Army (German: ''18. Armee'') was a World War II field army in the German ''Wehrmacht''.

Formed in November 1939 in Military Region (''Wehrkreis'') VI, the 18th Army was part of the offensive into the Netherlands (Battle of the Netherlan ...

, a third force, not all that much smaller than either, would operate on Dutch soil: the French 7th Army

The Seventh Army (french: VIIe Armée) was a field army of the French Army during World War I and World War II. World War I

Created on 4 April 1915 to defend the front between the Swiss border and Lorraine, the Seventh Army was the successor of t ...

. It had its own objectives within the larger French strategy, and French planning had long considered the possibility of operations in Dutch territory. The coastal regions of Zealand

Zealand ( da, Sjælland ) at 7,031 km2 is the largest and most populous island in Denmark proper (thus excluding Greenland and Disko Island, which are larger in size). Zealand had a population of 2,319,705 on 1 January 2020.

It is the 1 ...

and Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former province on the western coast of the Netherlands. From the 10th to the 16th c ...

were difficult to negotiate because of their many waterways. However, both the French and the Germans saw the possibility of a surprise flanking attack in this region. For the Germans this would have the advantage of bypassing the Antwerp-Namur

Namur (; ; nl, Namen ; wa, Nameur) is a city and municipality in Wallonia, Belgium. It is both the capital of the province of Namur and of Wallonia, hosting the Parliament of Wallonia, the Government of Wallonia and its administration.

Namu ...

line. The Zealand Isles were considered to be strategically critical, as they are just opposite the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

estuary, so their capture would pose a special menace to the safety of England.

Rapid forces, whether for an offensive or defensive purpose, were needed to deny vital locations to the enemy. Long before the Germans did, the French had contemplated using airborne troops to achieve speedy attacks. As early as 1936 the French had commissioned the design of light airborne tanks, but these plans had been abandoned in 1940, as they possessed no cargo planes large enough to carry them. A naval division and an infantry division were earmarked to depart for Zealand to block the Western Scheldt

The Western Scheldt ( nl, Westerschelde) in the province of Zeeland in the southwestern Netherlands, is the estuary of the Scheldt river. This river once had several estuaries, but the others are now disconnected from the Scheldt, leaving the W ...

against a German crossing. These would send forward forces over the Scheldt estuary into the Isles, supplied by overseas shipping.

French Commander in Chief General Maurice Gamelin feared the Dutch would be tempted into a quick capitulation or even an acceptance of German protection. He therefore reassigned the former French strategic reserve, the 7th Army, to operate in front of Antwerp to cover the river's eastern approaches in order to maintain a connection with the Fortress Holland further to the north and preserve an allied left flank beyond the Rhine. The force assigned to this task consisted of the 16th Army Corps, comprising the 9th Motorised Infantry Division (also possessing some tracked armoured vehicles) and the 4th Infantry Division; and the 1st Army Corps, consisting of the 25th Motorised Infantry Division and the 21st Infantry Division. This army was later reinforced by the 1st Mechanised Light Division, an armoured division of the French Cavalry and a first class powerful unit. Together with the two divisions in Zealand, seven French divisions were dedicated to the operation.Amersfoort (2005), p. 240

Although the French troops would have a higher proportion of motorised units than their German adversaries, in view of the respective distances to be covered, they could not hope to reach their assigned sector advancing in battle deployment before the enemy did. Their only prospect of beating the Germans to it lay in employing rail transport. This implied they would be vulnerable in the concentration phase, building up their forces near Breda. They needed the Dutch troops in the Peel-Raam Position to delay the Germans for a few extra days to allow a French deployment and entrenchment, but French rapid forces also would provide a security screen. These consisted of the reconnaissance units of the armoured and motorised divisions, equipped with the relatively well-armed Panhard 178

The Panhard 178 (officially designated as ''Automitrailleuse de Découverte Panhard modèle 1935'', 178 being the internal project number at Panhard) or "Pan-Pan" was an advanced French reconnaissance 4x4 armoured car that was designed for the ...

armoured car. These would be concentrated into two task forces named after their commander: the ''Groupe Beauchesne'' and the ''Groupe Lestoquoi''.

German strategy and forces

During the many changes in the operational plans for ''Fall Gelb'' the idea of leaving the Fortress Holland alone, just as the Dutch hoped for, was at times considered. The first version of 19 October 1939 suggested the possibility of a full occupation if conditions were favourable. In the version of 29 October it was proposed to limit the transgression to a line south ofVenlo

Venlo () is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the southeastern Netherlands, close to the border with Germany. It is situated in the province of Limburg (Netherland ...

. In the ''Holland-Weisung'' (Holland Directive) of 15 November it was decided to conquer the entire south, but in the north to advance no further than the Grebbe Line, and to occupy the Frisian Isles.Amersfoort (2005), p. 129 Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

insisted on a full conquest as he needed the Dutch airfields against Britain; also he was afraid the Entente might reinforce Fortress Holland after a partial defeat and use the airfields to bomb German cities and troops. Another rationale for complete conquest was that, as the fall of France itself could hardly be taken for granted, it was for political reasons seen as desirable to obtain a Dutch capitulation, because a defeat might well bring less hostile governments to power in Britain and France. A swift defeat would also free troops for other front sectors.Amersfoort (2005), p. 140