, also known as the Tendai Dharma Flower School (天台法華宗, ''Tendai hokke shū,'' sometimes just ''Hokkeshū''), is a

Mahāyāna Buddhist tradition with significant

esoteric

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas and currents are united since they are largely distinct both from orthod ...

elements that was officially established in

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

in 806 by the Japanese monk

Saichō.

The Tendai school, which has been based on

Mount Hiei since its inception, rose to prominence during the

Heian period

The is the last division of classical Japanese history, running from 794 to 1185. It followed the Nara period, beginning when the 50th emperor, Emperor Kammu, moved the capital of Japan to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto). means in Japanese. It is a ...

(794–1185). It gradually eclipsed the powerful

Hossō school and competed with the rival

Shingon school to become the most influential sect at the

Imperial court.

By the

Kamakura period

The is a period of History of Japan, Japanese history that marks the governance by the Kamakura shogunate, officially established in 1192 in Kamakura, Kanagawa, Kamakura by the first ''shōgun'' Minamoto no Yoritomo after the conclusion of the G ...

(1185–1333), Tendai had become one of the dominant forms of

Japanese Buddhism, with numerous temples and vast landholdings. During the Kamakura period, various

monks left Tendai to found new Buddhist schools such as

Jōdo-shū,

Jōdo Shinshū

, also known as Shin Buddhism or True Pure Land Buddhism, is a school of Pure Land Buddhism founded by the former Tendai Japanese monk Shinran.

Shin Buddhism is the most widely practiced branch of Buddhism in Japan.

History

Shinran (founder)

S ...

,

Nichiren-shū

is a combination of several schools ranging from four of the original Nichiren Buddhism, Nichiren Buddhist schools that date back to Nichiren's original disciples, and part of the fifth:

Overview

The school is often referred to as the Minob ...

and

Sōtō Zen

Zen (; from Chinese: ''Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka phil ...

.

The destruction of the head temple of

Enryaku-ji by

Oda Nobunaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods. He was the and regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan. He is sometimes referred as the "Demon Daimyō" and "Demo ...

in 1571, as well as the geographic shift of the capital away from

Kyoto

Kyoto ( or ; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in the Kansai region of Japan's largest and most populous island of Honshu. , the city had a population of 1.46 million, making it t ...

to

Edo, ended Tendai's dominance, though it remained influential.

In

Chinese and

Japanese, its name is identical to

Tiantai (meaning "Celestial Platform"), its parent

Chinese Buddhist tradition. Both traditions emphasize the importance of the ''

Lotus Sutra'' and revere the teachings of the Tiantai patriarchs, especially

Zhiyi. In English, the

Japanese romanization ''Tendai'' is used to refer specifically to the Japanese school. According to

Hazama Jikō, the main characteristic of Tendai is its comprehensive and universalist spirit, which is based on the "One Great Perfect Teaching," the idea that "all the teachings of the Buddha are ultimately without contradiction and can be unified in one comprehensive and perfect system."

[Hazama Jikō. ]

The Characteristics of Japanese Tendai.

' Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1987 14/2-3

Other unique elements include an exclusive use of the

bodhisattva precepts for ordination (without the

Pratimokṣa), a practice tradition based on the "Four Integrated Schools" (

Shikan,

Pure Land

Pure Land is a Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhist concept referring to a transcendent realm emanated by a buddhahood, buddha or bodhisattva which has been purified by their activity and Other power, sustaining power. Pure lands are said to be places ...

,

Mitsu and Precepts), and an emphasis on the study of

Chinese Esoteric Buddhist sources.

sees Tendai as "the most comprehensive and diversified" Buddhist tradition which provides a religious framework that is "suited to adapt to other cultures, to evolve new practices, and to universalize

Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

."

[Chappell, David W. (1987). 'Is Tendai Buddhism Relevant to the Modern World?' in ''Japanese Journal of Religious Studies'' 1987 14/2-3. Source]

Nanzan Univ.

accessed: Saturday August 16, 2008. p.247

History

Foundation by Saichō

The teachings of the Chinese Tiantai school founded by

Zhiyi (538–597 CE) had been had brought to Japan as early as 754 by

Jianzhen (Jp. ''Ganjin'').

However, Tiantai teachings did not take root until generations later when the monk

Saichō 最澄 (767–822) joined the

Japanese missions to Imperial China in 804 and founded

Enryaku-ji on

Mount Hiei. The future founder of

Shingon

is one of the major schools of Buddhism in Japan and one of the few surviving Vajrayana lineages in East Asian Buddhism. It is a form of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism and is sometimes called "Tōmitsu" (東密 lit. "Esoteric uddhismof Tō- ...

Buddhism,

Kūkai

, born posthumously called , was a Japanese Buddhist monk, calligrapher, and poet who founded the Vajrayana, esoteric Shingon Buddhism, Shingon school of Buddhism. He travelled to China, where he studied Tangmi (Chinese Vajrayana Buddhism) und ...

, also traveled on the same mission; however, the two were on separate ships and there is no evidence of their meeting during this period.

From the city of

Ningbo (then called Míngzhōu 明州), Saichō was introduced by the governor to

Dàosuì (道邃), who was the seventh Tiantai patriarch, and later he journeyed to

Tiantai Mountain for further study.

After receiving teachings and initiations on

Chan, Precepts and

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism, Saichō devoted much of his time to making accurate copies of Tiantai texts and studying under Dàosuì. By the sixth month of 805, Saichō had returned to Japan along with the official mission to China.

[Hazama Jik�]

“Dengyo Daishi’s Life and Teachings”

in “The Characteristics of Japanese Tendai.” ''Japanese Journal of Religious Studies'' 14/2-3 (1987): 101-112. Saichō was also influenced by his study of

Huayan (Jp. Kegon) philosophy under Gyōhyō 行表 (720–797) and this was his initial training before going to China.

[Forte, Victor. ''Saichō: Founding Patriarch of Japanese Buddhism'' In Gereon Kopf (ed.), ''The Dao Companion to Japanese Buddhist Philosophy''. Springer. pp. 307–335 (2019)]

Because of the Imperial Court's interest in Tiantai as well as esoteric Buddhism, Saichō quickly rose in prominence upon his return. He was asked by

Emperor Kanmu (735–806) to perform various esoteric rituals, and Saichō also sought recognition from the Emperor for a new, independent Tendai school in Japan.

Because the emperor sought to reduce the power of the

Hossō school, he granted this request, but with the stipulation that the new "Tendai" school would have two programs: one for esoteric Buddhism and one for exoteric Buddhist practice.

The new Tendai school was therefore based on a combination of the doctrinal and meditative system of Zhiyi with esoteric Buddhist practice and texts. Tendai learning at Mount Hiei traditionally followed two curriculums:

* ''Shikan-gō'' 止觀業: Exoteric practice, mainly based on Zhiyi's ''

Mohezhiguan''

* ''Shana-gō'' 遮那業: Esoteric Buddhism, focused on the ''

Mahāvairocana-sūtra'' and other tantric works

However, Emperor Kanmu died shortly thereafter, and Saichō was not allocated any ordinands until 809 with the reign of

Emperor Saga

was the 52nd emperor of Japan, Emperor Saga, Saganoyamanoe Imperial Mausoleum, Imperial Household Agency according to the traditional order of succession. Saga's reign lasted from 809 to 823.

Traditional narrative

Saga was the second son of ...

. Saichō's choice of establishing his community at Mount Hiei also proved fortuitous because it was located at the northeast of the new capital of

Kyoto

Kyoto ( or ; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in the Kansai region of Japan's largest and most populous island of Honshu. , the city had a population of 1.46 million, making it t ...

and thus was auspicious in terms of

Chinese geomancy as the city's protector.

Disagreements with other schools

The remainder of Saichō's life was spent in heated debates with notable Hossō figures, particularly

Tokuitsu, and maintaining an increasingly strained relationship with Kūkai (from whom he received esoteric initiations) to broaden his understanding of esoteric Buddhism. The debates with the Hossō school was primarily centered on the doctrine of the One Vehicle (''

ekayana'') found in the ''

Lotus Sutra'' which the Hossō school saw as not being an ultimate teaching. This was known as the ''San-Itsu Gon-Jitsu Ronsō'' (the debate over whether the One-vehicle or Three-vehicles, were the provisional or the real teaching) and it had a great influence on Japanese Buddhism.

Saichō also studied esoteric Buddhism under Kūkai, the founder of the

Shingon

is one of the major schools of Buddhism in Japan and one of the few surviving Vajrayana lineages in East Asian Buddhism. It is a form of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism and is sometimes called "Tōmitsu" (東密 lit. "Esoteric uddhismof Tō- ...

school. Saichō borrowed esoteric texts from Kūkai for copying and they also exchanged letters for some time. However, they eventually had a falling out (in around 816) over their understanding of Buddhist esotericism.

This was because Saichō attempted to integrate esoteric Buddhism (''mikkyo'') into his broader Tendai schema, seeing esoteric Buddhism as equal to the Tendai Lotus Sutra teaching. Saichō would write that Tendai and Mikkyo "interfuse with one another" and that "there should be no such thing as preferring one to the other."

Meanwhile, Kūkai saw mikkyo as different from and fully superior to ''kengyo'' (exoteric Buddhism) and was also concerned that Saichō had not finished his esoteric studies personally under him.

[Ryuichi Abe]

''Saichō and Kūkai: A Conflict of Interpretations Ryuichi Abe.''

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1995 22/1-2

Saichō's efforts were also devoted to developing a Mahāyāna ordination platform that required the

Bodhisattva Precepts of the ''Brahmajala Sutra'' only, and not the

pratimokṣa code of the

Dharmaguptaka

The Dharmaguptaka (Sanskrit: धर्मगुप्तक; ; ) are one of the eighteen or twenty early Buddhist schools from the ancient region of Gandhara, now Pakistan. They are said to have originated from another sect, the Mahīśāsakas f ...

''

vinaya

The Vinaya (Pali and Sanskrit: विनय) refers to numerous monastic rules and ethical precepts for fully ordained monks and nuns of Buddhist Sanghas (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). These sets of ethical rules and guidelines devel ...

'', which was traditionally used in East Asian Buddhist monasticism. Saichō saw the precepts of the small vehicle (''

hinayana'') as no longer being necessary.

His ideas were attacked by the more traditional Nara schools as well as the Sōgō (the Office of Monastic Affairs) and they were not initially approved by the imperial court. Saichō wrote the ''Kenkairon'' to respond to their criticisms. By the time that Saichō died in 822, his yearly petition was finally granted and the traditional "Four Part Vinaya" () was replaced by the Tendai Bodhisattva Precepts.

Development after Saichō

Seven days after Saichō died, the Imperial Court granted permission for the new Tendai Bodhisattva Precept ordination process which allowed Tendai to use an ordination platform separate from the powerful schools in

Nara

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an independent agency of the United States government within the executive branch, charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It is also task ...

. Gishin, Saichō's disciple and the first "''zasu''" , presided over the first allotted ordinands in 827. The appointments of the ''zasu'' typically only lasted a few years, and therefore among the same generation of disciples, a number could be appointed zasu in one's lifetime. After Gishin, the next zasu of the Tendai school were: Enchō (円澄),

Ennin 慈覺大師圓仁 (794–864), An'e (安慧),

Enchin 智證大師圓珍 (814–891), Yuishu (惟首), Yūken (猷憲) and Kōsai (康済).

By 864, Tendai monks were now appointed to the powerful

''sōgō'' with the naming of An'e (安慧) as the provisional vinaya master. Other examples include Enchin's appointment to the Office of Monastic Affairs in 883. While Saichō had opposed the Office during his lifetime, within a few generations disciples were now gifted with positions in the Office by the

Imperial Family

A royal family is the immediate family of monarch, monarchs and sometimes their extended family.

The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or emperor, empress, and the term papal family describes the family of ...

. By this time, Japanese Buddhism was dominated by the Tendai school to a much greater degree than Chinese Buddhism was by its forebear, the Tiantai.

Development of Tendai practice traditions

Philosophically, the Tendai school did not deviate substantially from the beliefs that had been created by the Tiantai school in China. However, Saichō had also transmitted numerous teachings from China was not exclusively Tiantai, but also included

Zen

Zen (; from Chinese: ''Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka phil ...

(禪), Pure Land, the esoteric

Mikkyō (密教), and

Vinaya School (戒律) elements. The tendency to include a range of teachings became more marked in the doctrines of Saichō's successors, such as

Ennin,

Enchin and Annen (安然, 841–?).

After Saichō, the Tendai order underwent efforts to deepen its understanding of teachings collected by the founder, particularly esoteric Buddhism. Saichō had only received initiation in the

Diamond Realm Mandala, and since the rival Shingon school under Kūkai had received deeper training, early Tendai monks felt it necessary to return to China for further initiation and instruction. Saichō's disciple

Ennin went to China in 838 and returned ten years later with a more thorough understanding of esoteric,

Pure Land

Pure Land is a Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhist concept referring to a transcendent realm emanated by a buddhahood, buddha or bodhisattva which has been purified by their activity and Other power, sustaining power. Pure lands are said to be places ...

, and Tiantai teachings.

Ennin brought important esoteric texts and initiation lineages, such as the ''

Susiddhikāra-sūtra,'' the ''

Mahāvairocana-sūtra'' and ''

Vajraśekhara-sūtra.''

However, in later years, this range of teachings began to form sub-schools within Tendai Buddhism. By the time of

Ryōgen, there were two distinct groups on Mt. Hiei, the

Jimon and Sanmon: the Sammon-ha "Mountain Group" (山門派) followed

Ennin and the Jimon-ha "Temple Group" (寺門派) followed

Enchin.

Konryū Daishi Sōō (831–918), a student of Ennin, is another influential Tendai figure. He is known for developing the ascetic practice circumambulating Mt. Hiei, living and practicing in the remote wilderness. This practice, which became associated with

Fudō Myōō (Acala) and Sōō's hermitage at Mudō- ji, became quite influential in Tendai. A more elaborate and systematized practice based on Sōō's simple mountain asceticism developed over time, and came to be called ''

kaihōgyō'' (回峰行). This remains an important part of Tendai Buddhism today.

Akaku Daishi

Annen (841–902?) is one of the most important post-Saichō Tendai thinkers. He wrote around a hundred works on Tendai doctrine and practice. According to Annen's theory of the "four ones" (''shiichi kyōhan'' 四一教判), all Buddhas are ultimately a single Buddha, all temporal moments are one moment, all Pure Lands are also just one Pure Land, and all teachings are interfused into one teaching.

According to Lucia Dolce, Annen "systematized earlier and contemporary doctrines elaborated in both streams of Japanese esoteric Buddhism, Tōmitsu (i.e., Shingon) and Taimitsu (Tendai)," "critically reinterpreted Kūkai's thought, offering new understandings of crucial esoteric concepts and rituals," and he also "elaborated theories that were to become emblematic of Japanese Buddhism, such as the realization of buddhahood by grasses and trees (''sōmoku jōbutsu'')" as well as ''hongaku shisō'' thought.

These various post-Saichō Tendai figures also developed the Tendai doctrine of "the identity of the purport of Perfect and Esoteric teachings" (''enmitsu itchi'' 円密一致) which according to Ōkubo Ryōshun "refers to the harmony and agreement between the Perfect teachings of the Lotus Sutra and Esoteric Buddhism."

[Ōkubo Ryōshun 大久保良峻]

“The Identity between the Purport of the Perfect and Esoteric Teachings.”

''Japanese Journal of Religious Studies'' 41/1 (2014): 83–102.

Later Heian

During the later

Heian period

The is the last division of classical Japanese history, running from 794 to 1185. It followed the Nara period, beginning when the 50th emperor, Emperor Kammu, moved the capital of Japan to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto). means in Japanese. It is a ...

,

Ryōgen 良源 (912–985) was an influential figure. He was the 18th abbot of Enryakuji, the Tendai head temple on Mount Hiei, and was an influential politician closely tied to the

Fujiwara clan

The was a powerful family of imperial regents in Japan, descending from the Nakatomi clan and, as legend held, through them their ancestral god Ame-no-Koyane. The Fujiwara prospered since ancient times and dominated the imperial court until th ...

, as well as a learned scholar. Due to his influence, the Tendai school became the dominant Buddhist tradition in Japanese intellectual life and at the

imperial court in Kyoto. Due to Ryōgen's influence, Fujiwara family members also came to occupy important positions at Tendai temples. Ryōgen is also said to have hired an army to protect Mt. Hiei, and some scholars see him as contributing the development of the warrior monk phenomenon (

sōhei). However, other scholars argue that warrior monks developed due to various other social and political pressures, such as the decline of the imperial bureaucratic state, the rise of temple estates, and the rise of noblemen joining the clergy.

[Adolphson, Mikael S. 2007. ''The Teeth and Claws of the Buddha: Monastic Warriors and Sōhei in Japanese History'', pp. 7-12. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.] Whatever the case, the late

Heian age also saw increased violence among Buddhist schools and temples (and sub-schools within Tendai as well), with armed groups resorting to violence to resolve disputes between Buddhist temples.

During this period, the main Tendai temples of

Enryakuji and

Onjōji resorted to armed violence against each other on more than one occasion.

Ryōgen's most influential disciples where

Genshin

, also known as , was a prominent Japanese monk of the Tendai school, recognized for his significant contributions to both Tendai and Pure Land Buddhism. Genshin studied under Ryōgen, a key reformer of the Tendai tradition, and became well kn ...

(''Eshin sōzu'' 942-1017) and Kakuun (''Dannasōzu'' 957-1007).

The lineages of these two figures developed into two main sects within Tendai, the Eshin school and the Danna school respectively. According to Shōshin Ichishima "Genshin's Eshin school espoused the doctrine of the original enlightenment, while Kakuun's Danna school espoused that of acquired enlightenment. The Eshinryū school used the

ninth consciousness as the basis of meditation, whereas the Dannaryū used the

sixth consciousness in the

yogācāra

Yogachara (, IAST: ') is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through the interior lens of meditation, as well as philosophical reasoning (hetuvidyā). ...

consciousness

ystem The Eshinryū school valued oral transmission of doctrine and meditative insight, while Dannaryū emphasized doctrine and texts. The Eshinryū school favored the "origin teaching" (''honmon''), and the latter fourteen chapters of the ''Lotus Sūtra'' over the "trace teaching" (''shakumon''), the first fourteen chapters, while the Dannaryū school regarded both sections as equally important. These differences distinguish the two schools."

Tendai Pure Land

During the Heian period, Tendai

Pure Land practice also developed into a significant and influential tradition. Early Pure Land Buddhism emphasized spiritual cultivation aimed at achieving birth in Amida Buddha’s Pure Land at the time of death as well as the constantly walking samadhi, a ''

Pratyutpanna Samādhi'' derived practice taught in Zhiyi's ''

Mohe Zhiguan'' in which one would circumambulate a Buddha statue while meditating on the features of the Buddha

Amitabha''.''

[Rhodes, Robert F. ''Genshin’s Ōjōyōshū and the Construction of Pure Land Discourse in Heian Japan'' p. 103. (2017, University of Hawaii Press)] Chinese Pure Land chanting methods, such as

Fazhao's five tone nembutsu (go-e nembutsu, 五会念仏) were also adopted into the Tendai tradition by figures like

Ennin. In early Japanese Tendai Pure Land discourse, monks such as Zenyu and

Senkan (918–984) embraced this practice and focused their teaching on Pure Land elements, seeing it as the most viable kind of practice for the age of

mappo (Dharma Decline). For them, adopting Pure Land practices did not signify abandoning the traditional Tendai path, rather the Pure Land path was seen as a practical and accessible method for entering the path, especially for those who felt incapable of advanced spiritual cultivation in their present lives. This interpretation allowed Pure Land devotion to align with the broader Tendai tradition, reinforcing the belief that all beings possess the potential for buddhahood.

Genshin

, also known as , was a prominent Japanese monk of the Tendai school, recognized for his significant contributions to both Tendai and Pure Land Buddhism. Genshin studied under Ryōgen, a key reformer of the Tendai tradition, and became well kn ...

(942–1017), an influential student of Ryōgen, wrote the famous ''Ōjōyōshū'' 往生要集 ("Essentials of Birth in the Pure Land"), a treatise on Pure Land practice which influenced later Pure Land Japanese figures. His work built upon the foundational ideas established by earlier monks like Senkan, emphasizing Pure Land practice as a viable and effective path toward enlightenment. Genshin’s approach integrated these earlier teachings, presenting Pure Land birth as a powerful tool for advancing along the bodhisattva path in the quest for buddhahood.

Genshin would later become a key figure for Japanese Pure Land teachers like

Hōnen.

Kamakura Period (1185–1333)

Although the Tendai sect flourished under the patronage of the

Imperial House of Japan and the noble classes, by the end of the

Heian period

The is the last division of classical Japanese history, running from 794 to 1185. It followed the Nara period, beginning when the 50th emperor, Emperor Kammu, moved the capital of Japan to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto). means in Japanese. It is a ...

, it experienced an increasing breakdown in monastic discipline. This was partly caused by political entanglements with rival factions of the

Genpei War

The was a national civil war between the Taira clan, Taira and Minamoto clan, Minamoto clans during the late Heian period of Japan. It resulted in the downfall of the Taira and the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate under Minamoto no Yori ...

, namely the

Taira and

Minamoto clans. Due to its patronage and growing popularity among the upper classes, the Tendai sect became not only respected, but also politically and even militarily powerful, with major temples having vast landholdings and fielding their own monastic armies of

sōhei (warrior-monks).

This was not unusual for major temples at the time, as major Buddhist temples (such as

Kōfuku-ji) fielded armies to protect their estates from

samurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

armies and bandits. With the outbreak of the

Genpei War

The was a national civil war between the Taira clan, Taira and Minamoto clan, Minamoto clans during the late Heian period of Japan. It resulted in the downfall of the Taira and the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate under Minamoto no Yori ...

(1180–1185), major Tendai temples armed themselves and sometimes joined the war.

In response to the perceived

worldliness

The world is the totality of entities, the whole of reality, or everything that exists. The nature of the world has been conceptualized differently in different fields. Some conceptions see the world as unique, while others talk of a "plu ...

and

elitism of the powerful Tendai school, a number of low-ranking Tendai monks became dissatisfied and began to teach radical new doctrines which focused on simpler and more popular practices. The major figures of "New

Kamakura

, officially , is a city of Kanagawa Prefecture in Japan. It is located in the Kanto region on the island of Honshu. The city has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 people per km2 over the tota ...

Buddhism" like

Nichiren

was a Japanese Buddhist priest and philosopher of the Kamakura period. His teachings form the basis of Nichiren Buddhism, a unique branch of Japanese Mahayana Buddhism based on the '' Lotus Sutra''.

Nichiren declared that the '' Lotus Sutra ...

,

Hōnen,

Shinran,

Eisai and

Dōgen

was a Japanese people, Japanese Zen Buddhism, Buddhist Bhikkhu, monk, writer, poet, philosopher, and founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan. He is also known as Dōgen Kigen (), Eihei Dōgen (), Kōso Jōyō Daishi (), and Busshō Dent� ...

, were all initially trained as Tendai monks.

Tendai practices and monastic organization were adopted to some degree or another by each of these new schools, but one common feature of each school was a more narrowly-focused set of practices (e.g.

daimoku for the Nichiren school,

zazen for Zen,

nembutsu

file:玉里華山寺 (21)南無阿彌陀佛古碑.jpg, 250px, Chinese Nianfo carving

The Nianfo ( zh, t=wikt:念佛, 念佛, p=niànfó, alternatively in Japanese language, Japanese ; ; or ) is a Buddhist practice central to East Asian Buddhism. ...

for Pure Land schools, etc.) in contrast to the more integrated approach of the Tendai. In spite of the rise of these new competing schools which saw Tendai as being "corrupt", medieval Tendai remained a "a rich, varied, and thriving tradition" during the medieval period according to Jacqueline Stone.

Initially, the largest and most popular of these new traditions—

Pure Land Buddhism

Pure Land Buddhism or the Pure Land School ( zh, c=淨土宗, p=Jìngtǔzōng) is a broad branch of Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhism focused on achieving rebirth in a Pure land, Pure Land. It is one of the most widely practiced traditions of East Asi ...

and

Nichiren Buddhism—did not attempt create new "schools" or "sects" separate from Tendai, as many of their monastics continued to be ordained and trained in Tendai institutions. Over time however, these groups gradually differentiated themselves from the Tendai mainstream, eventually forming separate institutions. As a number of new sects began to develop during the Kamakura period, the Tendai school used its patronage to try to oppose the growth of these rival factions. The Tendai establishment often used brigades of

sōhei (warrior monks) to repress these groups as well as drawing on their political influence. In one such event, Tendai warrior monks destroyed the printing blocks of

Hōnen's ''Senchakushū'' and raided the tomb of Hōnen''.

[Jodo Shu Research Institute]

The 4 Eras of Honen's Disciples

/ref>mantrayana

''Vajrayāna'' (; 'vajra vehicle'), also known as Mantrayāna ('mantra vehicle'), Guhyamantrayāna ('secret mantra vehicle'), Tantrayāna ('tantra vehicle'), Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, is a Mahāyāna Buddhism, Mahāyāna Buddhis ...

(''shingon'') Buddhism was superior to the Tendai Mahāyāna teaching of the one vehicle.

Muromachi and Sengoku Periods (1333–1600)

The Muromachi period

The , also known as the , is a division of Japanese history running from approximately 1336 to 1573. The period marks the governance of the Muromachi or Ashikaga shogunate ( or ), which was officially established in 1338 by the first Muromachi ...

saw Tendai Buddhism continue to hold prestige, but political instability and the weakening of the imperial court diminished its influence. Tendai remained closely connected to the Ashikaga shogunate, and its doctrines influenced esoteric and Pure Land practices. However, the school’s warrior monks were drawn into larger conflicts, particularly during the Ōnin War (1467–1477), which devastated Kyoto and disrupted religious institutions.

During this time, some Tendai figures sought to revive the fractured tradition in various ways. One such figure was Shinsei 眞盛 (1443–1495), who emphasized the practice of nembutsu.[Payne, Richard K]

''Shinzei’s Discourse on Practicing the Samadhi of Meditating on the Buddha''.

Pacific World Journal New Series Number 7 Fall 1991

During the Sengoku period, the power of Enryaku-ji was directly challenged by Oda Nobunaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods. He was the and regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan. He is sometimes referred as the "Demon Daimyō" and "Demo ...

. In 1571, seeking to break the political and military power of Buddhist institutions, Nobunaga launched a brutal assault on Mount Hiei, burning Enryaku-ji and massacring thousands of monks and laypeople. This event severely weakened Tendai’s influence and authority, though its doctrines and traditions persisted in smaller temples and through its connection with the imperial lineage.

Edo Period (1603–1868)

Kan'ei-ji's original Five-storied Pagoda

The Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868.

The Tokugawa shogunate was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu after victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, ending the civil wars ...

sought to control religious institutions, and under its temple registration system (the Danka system). Tendai, like other Buddhist schools, was integrated into the state’s religious structure. Enryaku-ji was rebuilt with shogunal support, but Tendai never regained the influence and power it had wielded in previous centuries. Tendai monks of this era refocused themselves on doctrinal study, ritual practice, and its esoteric (Taimitsu) traditions.

During this period, one of the most important Tendai leaders was Tenkai (1536–1643). Tenkai helped restore the school’s prestige by securing Tokugawa patronage, linking Tendai to the ideology of the shogunate and building new temples like Kita-in, and Kan'ei-ji near Tokyo

Tokyo, officially the Tokyo Metropolis, is the capital of Japan, capital and List of cities in Japan, most populous city in Japan. With a population of over 14 million in the city proper in 2023, it is List of largest cities, one of the most ...

, the new seat of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Meiji Period to Present (1868–Present)

The Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

brought severe challenges to Tendai and other Buddhist institutions. The government’s promotion of Shinto

, also called Shintoism, is a religion originating in Japan. Classified as an East Asian religions, East Asian religion by Religious studies, scholars of religion, it is often regarded by its practitioners as Japan's indigenous religion and as ...

led to the confiscation of temple lands and a decline in patronage. The 19th and early 20th centuries saw efforts to modernize the school while maintaining its traditional teachings. In the 20th century, Tendai became part of the broader Buddhist revival movements in Japan, with renewed interest in its esoteric and Lotus Sutra-based teachings.

One of the most prominent Tendai figures of the 20th century was Shōchō Hagami (1903–1989). He served as President of the Japanese Religious Committee for World Federation and was a great practitioner of extenseive Kaihōgyō.[Shocho Hagami, ''Kaihogyo No Kokoro'' (Kyoto: Shunju, 1996); Ichijo Miyamoto and Taisho Yokoyama, eds., ''Zansho'' (Otsu: Zenpon Sha, 1990), esp. 372-74.] Hagami, along with Etai Yamada (1900–1999) were two major Tendai figures of the 20th century who widely promoted religious dialogue with other world religions and traveled widely.

Worldview

According to Jiko Hazama, the Tendai Buddhist worldview advocates a comprehensive form of Buddhism which sees all Buddhist teachings as being unified under an inclusive reading of the ekayāna teaching of the ''Lotus Sutra''.

According to Jiko Hazama, the Tendai Buddhist worldview advocates a comprehensive form of Buddhism which sees all Buddhist teachings as being unified under an inclusive reading of the ekayāna teaching of the ''Lotus Sutra''.[Hazama, Jiko (1987). The Characteristics of Japanese Tendai, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 14 (2-3), p. 10]

PDF

/ref> This holistic and inclusive form of Buddhism is based on the doctrinal synthesis of Tiantai Zhiyi, which was ultimately based on the '' Lotus Sutra''.Japanese culture

Japanese culture has changed greatly over the millennia, from the country's prehistoric Jōmon period, to its contemporary modern culture, which absorbs influences from Asia and other regions of the world.

Since the Jomon period, ancestral ...

such as Shinto

, also called Shintoism, is a religion originating in Japan. Classified as an East Asian religions, East Asian religion by Religious studies, scholars of religion, it is often regarded by its practitioners as Japan's indigenous religion and as ...

and Japanese aesthetics. Tendai doctrines like original enlightenment and '' honji suijaku'' contributed to the integration of native Japanese religion with Tendai Buddhism.

In the major Tendai institutions like Taisho University and Mount Hiei, the main subjects of study are the ''Lotus Sutra'', the works of the Tiantai Patriarch Zhiyi, the works of the founder Saichō and some later Tendai figures like Ennin.

Foundational Tendai philosophy

The thought of the Japanese Tendai school is founded on the classic Chinese Tiantai doctrines found in the works of patriarchs Zhìyǐ and Zhanran. These foundational doctrines include:Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha (),*

*

*

was a śramaṇa, wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism. According to Buddhist lege ...

.[Teiser, Stephen F.; Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse (2009), ''Interpreting the Lotus Sutra''; in: Teiser, Stephen F.; Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse; eds. ''Readings of the Lotus Sutra'', New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 1–61, ]

Saichō taught that there were "three kinds of ''Lotus Sutra''". According to Jacqueline Stone, these can be explained as follows:[Stone, Jacqueline (1999)]

''Inclusive and Exclusive Perspectives on the One Vehicle''

/ref>

* The Fundamental ''Lotus'': "the one vehicle which represents the Buddha's single compassionate intent, underlying all his teachings, to lead all beings to buddhahood."

* The Hidden and Secret ''Lotus'': "those teachings in which, due to the immaturity of the Buddha's audience, this intention is not outwardly revealed."

* The ''Lotus'' that was Preached Explicitly: The actual text of the ''Lotus Sutra''.

Stone writes that Saichō saw all Buddhist teachings as being the true "''Lotus Sutra''" and he therefore attempted to integrate all Buddhist teachings he had studied within a single framework based on the ''Lotus Sutra'''s One Vehicle.

Doctrinal classification

Tendai thought also frames its understanding of Buddhist practice on the Lotus Sutra's teaching of upāya or . Furthermore, Tendai uses a similar hierarchy as the one used in Chinese Tiantai to classify the various other sutra

''Sutra'' ()Monier Williams, ''Sanskrit English Dictionary'', Oxford University Press, Entry fo''sutra'' page 1241 in Indian literary traditions refers to an aphorism or a collection of aphorisms in the form of a manual or, more broadly, a ...

s in the Buddhist canon in relation to the ''Lotus Sutra'', and it also follows Zhiyi's original conception of Five Periods Eight Teachings or ''gojihakkyō'' . This doctrinal classification system ( panjiao) is based on the doctrine of expedient means, but was also a common practice among East Asian schools trying to sort the vast corpus of writing inherited from India.[Shōshin Ichishima (2013)]

"Integration of sutra and Tantra on mt. Hiei."

Tendai Bdudhist Sect Overseas Charitable Foundation.

Later Tendai thinkers like Annen provided a new doctrinal classification system (based on Zhiyi's system) for Japanese Tendai. All Buddhist teachings are seen as being included into the following categories. The first major group are those teachings that rely on the three vehicles:

Buddha-nature

Tendai thought vigorously defends the idea that all beings have the potential for full buddhahood

In Buddhism, Buddha (, which in classic Indo-Aryan languages, Indic languages means "awakened one") is a title for those who are Enlightenment in Buddhism, spiritually awake or enlightened, and have thus attained the Buddhist paths to liberat ...

and thus that the Lotus Sutra was a teaching for all sentient beings.Yogacara

Yogachara (, IAST: ') is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through the interior lens of meditation, as well as philosophical reasoning (hetuvidyā). ...

) school in Japan who espoused the which argues that not all being can become Buddhas, since some do not have the seeds for Buddhahood.Dharma

Dharma (; , ) is a key concept in various Indian religions. The term ''dharma'' does not have a single, clear Untranslatability, translation and conveys a multifaceted idea. Etymologically, it comes from the Sanskrit ''dhr-'', meaning ''to hold ...

. Tendai Buddhism claims that each and every sense phenomenon ''just as it is'' is the expression of Dharma. This idea comes from Zhanran's view of buddha nature as an all-pervasive reality that also includes insentient things (like mountains, rivers etc). Drawing on this, Saichō also argued that insentient things possess Buddha-nature and that the distinction between sentient and insentient is ultimately illusory, since buddha-nature pervades all things through the principle of mutual inclusion, in which each dharma realm contains all others. Thus for Saichō ultimate reality, the Dharmakaya, actively manifests in the phenomenal world as the world itself.

Hongaku

The medieval Tendai school was the locus of the development of the Japanese doctrine of ''hongaku'' 本覚 (innate or original enlightenment), which holds that all beings are enlightened inherently. This theory developed in Tendai from the cloistered rule era (1086–1185) through the Edo period

The , also known as the , is the period between 1600 or 1603 and 1868 in the history of Japan, when the country was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and some 300 regional ''daimyo'', or feudal lords. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengok ...

(1688–1735).Kūkai

, born posthumously called , was a Japanese Buddhist monk, calligrapher, and poet who founded the Vajrayana, esoteric Shingon Buddhism, Shingon school of Buddhism. He travelled to China, where he studied Tangmi (Chinese Vajrayana Buddhism) und ...

.[Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse (2003). ''Original enlightenment and the transformation of medieval Japanese Buddhism''. Issue 12 of ''Studies in East Asian Buddhism''. A Kuroda Institute book: University of Hawaii Press. . Source]

(accessed: Thursday April 22, 2010), p.3 Scholars also refer to the doctrinal system associated with this idea as "original enlightenment thought". Stone defines this as the "array of doctrines and concepts associated with the proposition that all beings are enlightened inherently."Not only human beings, but ants and crickets, mountains and rivers, grasses and trees are all innately Buddhas. The Buddhas who appear in sutras, radiating light and endowed with excellent marks, are merely provisional signs. The "real" Buddha is the ordinary worldling. Indeed, the whole phenomenal world is the primordially enlightened Tathāgata.

Tamura Yoshirō argued that hongaku was a non-dual teaching which saw all existents as interpenetrating and mutually identified. This negates any ontological difference between Buddhas and common people as well as between pure lands and mundane worlds. Tamura argued that this move re-affirms the relative phenomenal world as an expression of the ultimate nondual reality and is found in phrases like "the worldly passions are precisely enlightenment" and "birth and death are precisely nirvana".

Buddhahood with this very body

Another important doctrine in Japanese Tendai is that it is possible to attain "Buddhahood with this very body" (即身成佛 ''sokushin jōbutsu''). This is closely related to the idea of original enlightenment.[Groner, Paul. ''Shortening the Path: Early Tendai Interpretations of the Realization of Buddhahood with This Very Body (Sokushin jobutsu)'' in Buswell, Robert E.; Gimello, Robert M. (1992) ''"Paths to Liberation: The Mārga and Its Transformations in Buddhist Thought".'' University of Hawaii Press.] This idea was introduced by Saichō, who held that this described certain advanced practitioners who had realized the fifth degree of identity, though this attainment was a rare thing.Shingon

is one of the major schools of Buddhism in Japan and one of the few surviving Vajrayana lineages in East Asian Buddhism. It is a form of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism and is sometimes called "Tōmitsu" (東密 lit. "Esoteric uddhismof Tō- ...

school led Tendai scholars to continue to explore ways to "shorten the path" and attain Buddhahood swiftly in one lifetime. Later Tendai scholars like Rinshō, and Annen were much more optimistic about ''sokushin jōbutsu'', claiming certain esoteric practices could lead to Buddhahood rapidly in only one lifetime, while de-emphasizing the concern with achieving Buddhahood in future lives. They also further extended the application of this idea to individuals at the lower levels of the degrees of identity, arguing that one could jump over bodhisattva stages and attain Buddhahood without fully eradicating defilements. This idea, known as "realization by worldlings" (bon'i jōbutsu), posited that practitioners could gain Buddha-wisdom through the power of the Buddha's presence and the Taimitsu esoteric practices. According to Groner, this allowed "for the possibility that worldlings who still have some of the coarser defilements might experience ''sokushin jōbutsu''."

Honji suijaku

Another important theory which developed in the Japanese Tendai school during the early Heian period was the theory of '' honji suijaku'' (本地垂迹, traces from the original ground). This idea facilitated the integration of native Japanese deities (kami

are the Deity, deities, Divinity, divinities, Spirit (supernatural entity), spirits, mythological, spiritual, or natural phenomena that are venerated in the traditional Shinto religion of Japan. ''Kami'' can be elements of the landscape, forc ...

) into the Buddhist pantheon, with buddhas seen as representing the ‘original ground’ (honji 本地) and the kami as their ‘traces’ (suijaku 垂迹).wisdom kings

A wisdom king (Sanskrit: विद्याराज; International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration, IAST: ''vidyārāja'', ) is a type of Wrathful deities, wrathful deity in East Asian Buddhism.

Whereas the Sanskrit name is translated lite ...

, and celestial beings as manifestations of Dainichi ( Mahavairocana).

Study

The Tendai school emphasizes the unity of study and practice. The curriculum includes a comprehensive approach to Buddhist study that reflects its foundation in the Chinese tradition. The Tendai curriculum is distinctive for its breadth, combining scriptural study, debate, and exegesis.

The primary textual foundation of the Tendai school is the ''Threefold Lotus Sūtra'' (Japanese: ''Hokke-kyō''), which is regarded as the supreme teaching of the Buddha and the main scriptural authority of the Tendai tradition. In addition to the ''Lotus Sutra'', the Tendai curriculum includes several other key Indic sources which are used to support the ''Lotus Sutra'' which are'':'' the '' Daichido-ron (Great Wisdom Treatise)'', the '' Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra'' (Jp: ''Daihatsunehan-kyō''), the '' Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra'' '' in 25000 slokas'' (''Daihannya-kyō'') and the ''Book of the Original Acts that Adorn the Bodhisattva'' (''Bosatsu Yōraku Hongyō Kyō'', T. 24, No. 1485).

Practice

Tendai Practice Theory

A feature unique to Japanese Tendai Buddhism from its inception was the concept of ''shishūyūgō'' . Senior Tendai teachers, or ajari, train in various practice traditions, especially the "Shishū Sōjō" (Four-fold transmission).Mahayana sutras

The Mahayana sutras are Buddhist texts that are accepted as wikt:canon, canonical and authentic Buddhist texts, ''buddhavacana'' in Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhist sanghas. These include three types of sutras: Those spoken by the Buddha; those spoke ...

and Tendai doctrine (''Tendai no kyōgi''), as well as various ritual practices, such as the Lotus Repentance Ritual (''Hokke Senbo''). It also includes ''Lotus Sutra'' devotional practices, such as those described in the '' Hokke Genki,'' which often center around the recitation of the ''Lotus Sutra''. A common practice still observed today is the ''Method for Prostrating to the Dharma Flower Sūtra'' (禮法華經儀式), which involves prostrations to each character of the sūtra in long (the entire sutra), medium (selecting one chapter of the text), or short forms. The short form focuses on prostrating to the characters of the sūtra's title, often accompanied by a dedication chant.

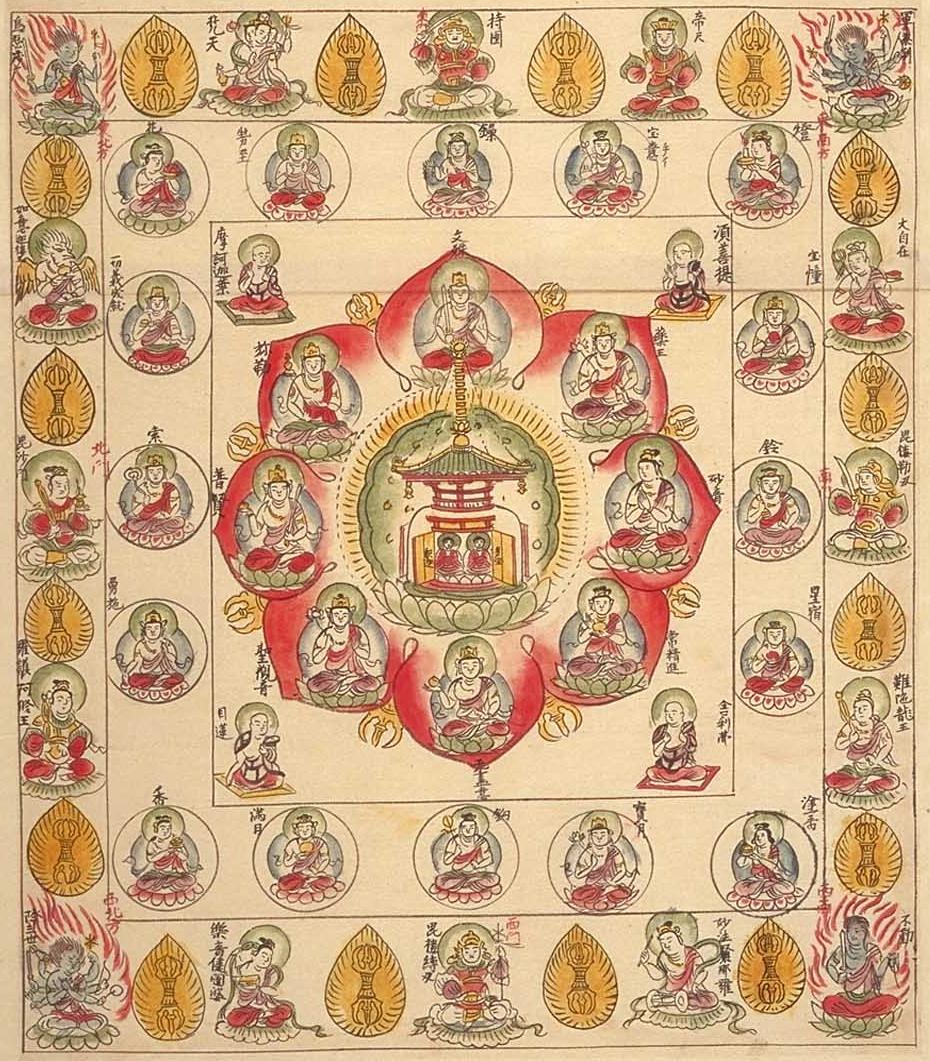

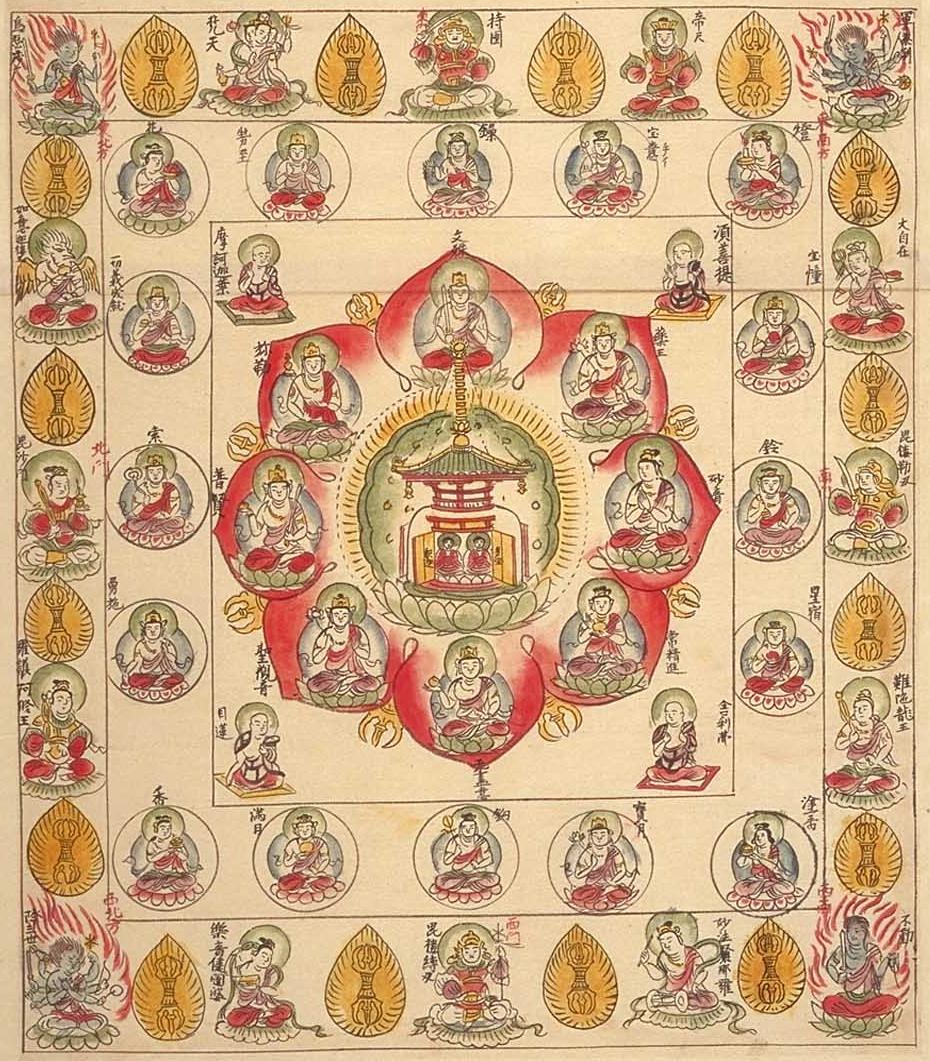

* Esoteric practices (''Mitsu'' or '' Mikkyō'' 密教) which make use of mantras, mudras and mandalas from tantras like the '' Vairocanābhisaṃbodhi Sūtra'' and Yixing's commentary

* Meditation (''Zen''), this is ''not'' the practice of "Zen Buddhism

Zen (; from Chinese: '' Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka ph ...

", but merely signifies Tendai teachings on "meditation" ( dhyāna), including '' Śamatha- vipaśyanā'' meditation (''Shikan'' 止観, "calming-insight") based on Zhiyi's '' Móhē zhǐguān'' and to a lesser extent, his other meditation works

* Precepts (''Kai''), in particular the Bodhisattva Precepts based on the ''Lotus Sutra'' and the '' Brahmajāla Sūtra.''

* Pure Land

Pure Land is a Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhist concept referring to a transcendent realm emanated by a buddhahood, buddha or bodhisattva which has been purified by their activity and Other power, sustaining power. Pure lands are said to be places ...

(''Jōdo'' 浄土) practices focused on Amitabha, especially the recitation of the Buddha's name (''nembutsu

file:玉里華山寺 (21)南無阿彌陀佛古碑.jpg, 250px, Chinese Nianfo carving

The Nianfo ( zh, t=wikt:念佛, 念佛, p=niànfó, alternatively in Japanese language, Japanese ; ; or ) is a Buddhist practice central to East Asian Buddhism. ...

''), based on the Pure Land sutras and '' Treatise on the Pure Land'' by Vasubandhu

Vasubandhu (; Tibetan: དབྱིག་གཉེན་ ; floruit, fl. 4th to 5th century CE) was an influential Indian bhikkhu, Buddhist monk and scholar. He was a philosopher who wrote commentary on the Abhidharma, from the perspectives of th ...

To this, one can also add other elements that became integrated to Tendai practice, including Shinto

, also called Shintoism, is a religion originating in Japan. Classified as an East Asian religions, East Asian religion by Religious studies, scholars of religion, it is often regarded by its practitioners as Japan's indigenous religion and as ...

and Shugendō practices. It is due to this syncretic aspect of Tendai that it is sometimes termed ''Integrated Buddhism'' (総合佛教 ''Sōgōbukkyō'').[Gardiner, David L. (2019). ''Tantric Buddhism in Japan: Kūkai and Saichō.'' ]Shingon

is one of the major schools of Buddhism in Japan and one of the few surviving Vajrayana lineages in East Asian Buddhism. It is a form of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism and is sometimes called "Tōmitsu" (東密 lit. "Esoteric uddhismof Tō- ...

founder Kūkai

, born posthumously called , was a Japanese Buddhist monk, calligrapher, and poet who founded the Vajrayana, esoteric Shingon Buddhism, Shingon school of Buddhism. He travelled to China, where he studied Tangmi (Chinese Vajrayana Buddhism) und ...

, Saichō did not see esoteric teachings as more powerful or superior to exoteric Tendai teaching and practice. Instead, Saichō held that all Buddhist teachings are included in the single intent of the ''Lotus Sutra''.

Shikan meditation

Tendai's Shikan-gō (止觀業) tradition focuses on shikan ('' śamatha-vipaśyanā'') meditation, especially on the Four Samadhis (四種三昧, ''shishu zanmai'') as taught in Zhiyi’s '' Móhē zhǐguān'' (''Great Cessation ndContemplation''). Saichō emphasized the importance of the ''Four Samādhis'' in his ''Kanjō Tendai-shū Nenbun Gakushō-shiki'' (Regulations for Tendai School Annual Ordinands), and he sought to establish special halls as a place for these practices.[清水擴「初期延暦寺における四種三昧堂」『建築史学』第42巻、建築史学会](_blank)

��2004年、doi:10.24574/jsahj.42.0_88。 The ''Four Samādhis'' are foundational to Tendai Buddhism and are designed to cultivate deep states of meditative absorption (''samādhi

Statue of a meditating Rishikesh.html" ;"title="Shiva, Rishikesh">Shiva, Rishikesh

''Samādhi'' (Pali and ), in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, is a state of meditative consciousness. In many Indian religious traditions, the cultivati ...

'').

The Four-fold Samādhi (四種三昧 shishu-zammai) is outlined as follows:Amitābha

Amitābha (, "Measureless" or "Limitless" Light), also known as Amituofo in Chinese language, Chinese, Amida in Japanese language, Japanese and Öpakmé in Tibetan script, Tibetan, is one of the main Buddhahood, Buddhas of Mahayana, Mahayana Buddh ...

or within a designated meditation space. The practitioner maintains mindfulness while moving. This practice is based on the '' Pratyutpanna Samādhi Sutra'', which emphasizes the contemplation of Amitābha and recitation of his name. It also influenced the development of Pure Land Buddhism in East Asia.

* Half-Walking and Half-Sitting Samādhi (半行半坐三昧, ''Hangyō Hanza Zanmai''): This practice alternates between periods of seated meditation and walking meditation, seamlessly transitioning between the two without breaks. The duration can vary, with some practices lasting 21 days (based on the ''Lotus Sutra'') or 7 days (based on the ''Great Correct and Equal Dhāranī Sutra''). This practice is often incorporated into rituals like the ''Hokke Senbo'' (法華懺法, Lotus Repentance Ritual), where practitioners alternate between sitting and walking while chanting the ''Lotus Sutra'' and other texts.

* Neither Walking nor Sitting Samādhi (非行非坐三昧, ''Hikō Hiza Zanmai''): This practice is not confined to a specific posture or duration. It encompasses all forms of meditation that do not fit into the other three categories, allowing for flexibility in practice. This practice represents the ultimate goal of integrating meditation into every moment of daily life, emphasizing the universality of meditative practice beyond structured forms.

Other forms of Tendai meditation include the famous hiking

A hike is a long, vigorous walk, usually on trails or footpaths in the countryside. Walking for pleasure developed in Europe during the eighteenth century. Long hikes as part of a religious pilgrimage have existed for a much longer time.

"Hi ...

meditation practice of Kaihōgyō (回峰行 Circling the mountain).

Pure Land practice

Practices related to and veneration of

Practices related to and veneration of Amitābha

Amitābha (, "Measureless" or "Limitless" Light), also known as Amituofo in Chinese language, Chinese, Amida in Japanese language, Japanese and Öpakmé in Tibetan script, Tibetan, is one of the main Buddhahood, Buddhas of Mahayana, Mahayana Buddh ...

and his pure land of Sukhavati

Sukhavati ( IAST: ''Sukhāvatī''; "Blissful"; Chinese: 極樂世界, lit. "realm of ultimate bliss") is the pure land (or buddhafield) of the Buddha Amitābha in Mahayana Buddhism. Sukhavati is also called the Land of Bliss or Western Pure L ...

in the Tendai tradition began with Saichō's disciple, Ennin. After journeying to China for further study and training, he brought back a practice called the "five-tone ''nembutsu''" or , which was a form of intonation practiced in China for reciting the Buddha's name. This contrasted with earlier practices in Japan starting in the Nara period

The of the history of Japan covers the years from 710 to 794. Empress Genmei established the capital of Heijō-kyō (present-day Nara). Except for a five-year period (740–745), when the capital was briefly moved again, it remained the capita ...

, where meditation on images of the Pure Land, typically in the form of mandala, were practiced.Genshin

, also known as , was a prominent Japanese monk of the Tendai school, recognized for his significant contributions to both Tendai and Pure Land Buddhism. Genshin studied under Ryōgen, a key reformer of the Tendai tradition, and became well kn ...

(源信, 942–1017) who was a disciple of Ryōgen, the 18th chief abbot or ''zasu'' (座主) of Mount Hiei. Genshin wrote an influential treatise called , which vividly contrasted the Sukhavati Pure Land of Amitābha with the descriptions of the hell realms in Buddhism. Further, Genshin promoted the popular notion of the Latter Age of the Dharma, which posited that society had degenerated to a point when they could no longer rely on traditional Buddhist practices, and would instead need to rely solely on Amitābha's grace to escape saṃsāra. Genshin drew upon past Chinese Pure Land teachers such as Daochuo and Shandao

Shandao (; ; 613–681) was a Chinese Buddhist scholar monk and an influential figure of East Asian Pure Land Buddhism.Jones (2019), pp. 20-21

Shandao was one of the first Pure Land authors to argue that all Pṛthagjana, ordinary people, and e ...

.Jōdo Shinshū

, also known as Shin Buddhism or True Pure Land Buddhism, is a school of Pure Land Buddhism founded by the former Tendai Japanese monk Shinran.

Shin Buddhism is the most widely practiced branch of Buddhism in Japan.

History

Shinran (founder)

S ...

.

Tendai Esotericism (''Taimitsu'')

A key element of Tendai is esoteric Buddhist practice and theory. This was originally known as "the ''shingon'' (or '' mikkyō'') of the Tendai lineages" and was later named ''Taimitsu'' ("Tendai Esotericism", 台密), distinguishing it from the Shingon

is one of the major schools of Buddhism in Japan and one of the few surviving Vajrayana lineages in East Asian Buddhism. It is a form of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism and is sometimes called "Tōmitsu" (東密 lit. "Esoteric uddhismof Tō- ...

( Mantra) school, which is known as "Tōmitsu" (東密, literally, "the esotericism of the Tōji lineages").[Dolce, Lucia. ''Taimitsu: The Esoteric Buddhism Of The Tendai School'' In: "Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia", pp. 744–767. BRILL. ] Taimitsu, as a form of East Asian Esoteric Buddhism, holds that by making use of mantras, mudras, and mandalas (known as "the three mysteries"), one is able to attain Buddhahood within this very body. Eventually, these esoteric rituals came to be considered of equal importance with the teachings of the ''Lotus Sutra,'' which was also seen as an esoteric sutra (but only "in principle", not "in practice", since it did not include the practice of the three mysteries).Shingon

is one of the major schools of Buddhism in Japan and one of the few surviving Vajrayana lineages in East Asian Buddhism. It is a form of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism and is sometimes called "Tōmitsu" (東密 lit. "Esoteric uddhismof Tō- ...

, though some of the underlying doctrines and practices differ. Regarding textual basis, while Shingon mainly uses the '' Mahavairocana Tantra'' and the '' Vajrasekhara Sutra'' (seeing these as the highest and most superior texts), Tendai uses a larger corpus of texts, including the ''Lotus Sutra'' and esoteric Lotus Sutra texts.[Lucia Dolce, "The Lotus Sutra and Esoteric Buddhism," The Lotus Sutra and Japanese Culture. ルチア・ドルチェ「法華経と密教」『法華経と日本文化』、大正大学出版会.] To defend this view, Tendai scholars pointed to passages in the ''Lotus Sutra'' itself, such as when the sutra refers to itself as "the secret essential of the buddhas" and "the secret treasure of the Thus-Come One." They also relied on the interpretations of Yixing.

Lotus Esotericism (Hokke Mikkyō)

The ''Lotus Sutra'' underwent a process of "esotericization" in the medieval Tendai school, fueled by the tradition's engagement with Esoteric Buddhism. This esotericism did not originate in Japan, since there were esoteric sources written in China that Tendai relied on for their interpretations of the ''Lotus Sutra''. However, Lotus Esotericism became much more central in Japanese Tendai than in the mainland.

The ''Lotus Sutra'' underwent a process of "esotericization" in the medieval Tendai school, fueled by the tradition's engagement with Esoteric Buddhism. This esotericism did not originate in Japan, since there were esoteric sources written in China that Tendai relied on for their interpretations of the ''Lotus Sutra''. However, Lotus Esotericism became much more central in Japanese Tendai than in the mainland.[Dolce, Lucia]

“Hokekyô to mikkyô,” [The Lotus Sutra and Tantric Buddhism

/nowiki>">he Lotus Sutra and Tantric Buddhism">“Hokekyô to mikkyô,” [The Lotus Sutra and Tantric Buddhism

/nowiki>in ''Hokekyô to Nichiren'', vol. 1 of ''Shirizu Nichiren'', 5 vols, Komatsu Hôshô and Hanano Jûdô, eds, Tokyo: Shunjûsha, 2014, pp. 268-293. The most important Chinese sources for this tradition are Yixing's (683–727) ''Darijing Shu'' (''Commentary on the Mahāvairocana Sutra''), which integrates Tiantai ideas with Chinese mantrayana

''Vajrayāna'' (; 'vajra vehicle'), also known as Mantrayāna ('mantra vehicle'), Guhyamantrayāna ('secret mantra vehicle'), Tantrayāna ('tantra vehicle'), Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, is a Mahāyāna Buddhism, Mahāyāna Buddhis ...

, and the ''Ritual Manual for the Contemplation of the Lotus Sutra'' (''Fahua guanzhi yigui,'' 法華経観智儀軌), an esoteric manual. This manual describes a deity yoga practice based on the ''Lotus Sutra'' which relies on reciting passages and mantras from the sutra, and arranging a ritual altar and a Lotus Maṇḍala. The ''Lotus Contemplation Manual'' derives from Amoghavajra's circle and was likely composed by him or his disciples.

Bodhisattva precepts

The Tendai school's ethical teachings focus exclusively on the Bodhisattva Precepts (C. ''pusajie'', J. ''bostasukai'' 菩薩戒) drawn from the '' Brahmajala Sutra.'' Tendai ordinations do not make use of the traditional Dharmaguptaka

The Dharmaguptaka (Sanskrit: धर्मगुप्तक; ; ) are one of the eighteen or twenty early Buddhist schools from the ancient region of Gandhara, now Pakistan. They are said to have originated from another sect, the Mahīśāsakas f ...

Vinaya

The Vinaya (Pali and Sanskrit: विनय) refers to numerous monastic rules and ethical precepts for fully ordained monks and nuns of Buddhist Sanghas (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). These sets of ethical rules and guidelines devel ...

Pratimoksha set of monastic rules. Saichō argued in favor of this idea in his ''Kenkairon'' (顕戒論, "On promoting the Mahāyāna precepts"). This was a revolutionary change in East Asian Buddhism that was without precedent.[Lin, Pei‐Yin (2011) ''Precepts and lineage in Chan tradition: cross‐cultural perspectives in ninth century East Asia,'' pp. 147–148, 154-157. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/14241]The first category includes the prohibitions against the ten major and forty-eight minor transgressions as explained in the ''Bonmokyo'' 梵辋経 (T24, 997–1010). It also includes general restrictions against any kind of evil activity, whether physical, verbal, or mental. Any and all kinds of moral cultivation are included. The second category entails every kind of good activity, including but not limited to acts associated with the Buddhist categories of keeping precepts, the practice of concentration (samadhi), and the cultivation of wisdom. Also included are such worldly pursuits as dedication to scholarly excellence, or any effort aimed at self improvement. The third category refers not only to the effort to help and save all sentient beings through the perfection of the six Mahayana virtues (paramita, charity, morality, patience, diligence, meditation, and wisdom), but also includes such mundane activity as raising one's children with loving care, living for the sake of others, and dedicating oneself to the good of society.

The Tendai school made extensive use of the Lotus Sutra in its interpretation of the bodhisattva precepts, even though the sutra does not itself contains a specific list of precepts. Also, various passages from the sutra were used to defend the Tendai position not to follow the pratimoksha, since they state, for example, "we will not follow śrāvaka ways."

Saichō’s rejection of the Hīnayāna vinaya precepts stemmed from his understanding of the ''Lotus Sutra'' as the ultimate expression of the Buddha's teachings. In his biography, ''Eizan Daishi den'', Saichō expressed his commitment to abandoning the 250 Hīnayāna precepts and focused on the bodhisattva path. His interpretation of the ''Lotus Sutra'', particularly in the "Comfortable Practices" chapter, provided a basis for rejecting śrāvaka practices and precepts. Saichō’s reforms eventually led to the development of the "Perfect-Sudden Precepts," which emphasized the inherent Buddha-nature in all beings and allowed for a more flexible approach to monastic discipline.

The bodhisattva precepts were thus seen in Tendai as being based on the ''Lotus Sutr''a's teaching that all beings have the potential for Buddhahood and that they have a fundamental goodness, or Buddha-nature.

Tendai and Shinto

Tendai doctrine allowed Japanese Buddhists to reconcile Buddhist teachings with the native religious beliefs and practices of Japan (now labeled "

Tendai doctrine allowed Japanese Buddhists to reconcile Buddhist teachings with the native religious beliefs and practices of Japan (now labeled "Shinto

, also called Shintoism, is a religion originating in Japan. Classified as an East Asian religions, East Asian religion by Religious studies, scholars of religion, it is often regarded by its practitioners as Japan's indigenous religion and as ...

"). In the case of Shinto, the difficulty is the reconciliation of the pantheon of Japanese gods (''kami

are the Deity, deities, Divinity, divinities, Spirit (supernatural entity), spirits, mythological, spiritual, or natural phenomena that are venerated in the traditional Shinto religion of Japan. ''Kami'' can be elements of the landscape, forc ...

''), as well as with the myriad spirits associated with places, shrines or objects, with Buddhist teachings. These gods and spirits were initially seen as local protectors of Buddhism.[Sugahara Shinkai 菅原信海 ]

The Distinctive Features of Sanno Ichijitsu Shinto.

' Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1996 23/1-2.

Sannō Shintō 山王神道 was a specifically Tendai branch of syncretic Buddhist-Shinto religious practice, which revered kamis called the Mountain Kings (Sannō) or Sanno Sansei 山王三聖 (The Three Sacred eitiesof Sanno) and was based on Hie Taisha 日吉大社 a shrine on Mount Hiei.kami

are the Deity, deities, Divinity, divinities, Spirit (supernatural entity), spirits, mythological, spiritual, or natural phenomena that are venerated in the traditional Shinto religion of Japan. ''Kami'' can be elements of the landscape, forc ...

are simply local manifestations (the ''suijaku'' or "traces") of the Buddhas (''honji,'' "true nature"). This manifestation of the Buddhas was explained through the classic Mahayana doctrines of skillful means and the Trikaya.

Shugendō

Some Tendai Buddhist temples and mountains are also sites for the practice of the syncretic Shugendō tradition. Shugendō is a mountain ascetic practice which also adopted Tendai and Shingon elements. This tradition focuses on ascetic practices on mountainous terrain.[Castiglioni, Andrea; Rambelli, Fabio; Roth, Carina (2020). ''Defining Shugendo: Critical Studies on Japanese Mountain Religion'', p. 8. Bloomsbury Publishing.]

Art and aesthetics

The classic Buddhist understanding of the

The classic Buddhist understanding of the Four Noble Truths

In Buddhism, the Four Noble Truths (; ; "The Four Arya (Buddhism), arya satya") are "the truths of the noble one (the Buddha)," a statement of how things really are (Three marks of existence, the three marks of existence) when they are seen co ...

posits that craving for pleasure, worldly desire and attachment must be cut off to put an end to suffering ('' dukkha''). In early Buddhism, the emphasis, especially for monastics, was on avoiding activities that might arouse worldly desires, including many artistic endeavors like music and performance arts. This tendency toward rejecting certain popular art forms created a potential conflict with mainstream East Asian cultures.

However, later Mahayana

Mahāyāna ( ; , , ; ) is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, Buddhist texts#Mahāyāna texts, texts, Buddhist philosophy, philosophies, and practices developed in ancient India ( onwards). It is considered one of the three main ex ...

views developed a different emphasis which embraced all the arts. In Japan, certain Buddhist rituals (which were also performed in Tendai) grew to include music and dance, and these became very popular with the people. Doctrinally, these performative arts were seen as skillful means (''hōben'', Skt. ''upaya'') of teaching Buddhism. Monks specializing in such arts were called ''yūsō'' ("artistic monks"). The writing of religious poetry was also a major pursuit among certain Tendai as well as Shingon figures, like the Shingon priest Shukaku and the Tendai monk Jien (1155–1225). These poets met together to discuss poetry in poetry circles (''kadan'').[Deal, William E.; Ruppert, Brian (2015). ''A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism'', pp. 104-106. John Wiley & Sons. .] According to Deal and Ruppert, "Shingon, Tendai and Nara cloisters had a great impact on the development of literary treatises and poetry houses."[LaFleur, R. William. ''Symbol and Yūgen: Shunzei's Use of Tendai Buddhism'' In "Flowing Traces: Buddhism in the Literary and Visual Arts of Japan," pp. 16-45, edited by James H. Sanford, William R. LaFleur, Masatoshi Nagatomi.] According to William R. LaFleur, the development of ''yūgen'' aesthetic theory was also influenced by the Tendai practice of ''shikan'' meditation. According to LaFleur, for Shunzei's poetics, the beauty of ''yūgen'' manifests a deep tranquility which reflects and is akin to ''shikan'' practice. This link is asserted by Shunzei in his ''Kurai futeisho.''[Odin, Steve (2001). ''Artistic Detachment in Japan and the West: Psychic Distance in Comparative Aesthetics'', pp. 107-108. University of Hawaii Press.] These poets also understood the depth of ''yūgen'' through the holistic Tendai metaphysics of interfusion''.''

Key Tendai figures

Chinese Ancestors

Portrait of Dengyō Daishi (Saichō) at the MET

The following ancestors or patriarchs (祖) form the main line of the Chinese Tiantai lineage:

* Nāgārjuna (3rd century CE)

* Huiwen (d.u.), who is said to have read Nāgārjuna's works, practiced accordingly, and then had a direct insight into the master's Dharma, thus initiating the Chinese Tiantai lineage

* Nanyue Huisi (515-577), a Meditation Master and Lotus Sūtra specialist who was Zhiyi's teacher

* Tiantai Zhiyi (538–597), the most important figure of the Tiantai school who wrote the foundational treatises of the tradition

* Guanding 561–632), Zhiyi's student, he edited and compiled the main treatises of Zhiyi

* Zhiwei (?–680)

* Huiwei (634–713)

* Xuanlang (673-754)

* Zhanran (711-782), the second most important Chinese Tiantai master, he wrote some key commentaries to Zhiyi's three major works

* Daosui (806-820) and Xingman (?–823), both students of Zhanran and teachers of Saichō

Portrait of Dengyō Daishi (Saichō) at the MET

The following ancestors or patriarchs (祖) form the main line of the Chinese Tiantai lineage:

* Nāgārjuna (3rd century CE)

* Huiwen (d.u.), who is said to have read Nāgārjuna's works, practiced accordingly, and then had a direct insight into the master's Dharma, thus initiating the Chinese Tiantai lineage

* Nanyue Huisi (515-577), a Meditation Master and Lotus Sūtra specialist who was Zhiyi's teacher

* Tiantai Zhiyi (538–597), the most important figure of the Tiantai school who wrote the foundational treatises of the tradition

* Guanding 561–632), Zhiyi's student, he edited and compiled the main treatises of Zhiyi

* Zhiwei (?–680)

* Huiwei (634–713)

* Xuanlang (673-754)

* Zhanran (711-782), the second most important Chinese Tiantai master, he wrote some key commentaries to Zhiyi's three major works

* Daosui (806-820) and Xingman (?–823), both students of Zhanran and teachers of Saichō

Japanese Ancestors

The Japanese Tendai founder Saichō (最澄, 767–822) was a student of the last two patriarchs on the list, Daosui (806-820) and Xingman (?–823), both of whom studied under Zhanran. Saichō received Tiantai teachings and texts from them at Guoqing temple on Mt. Tiantai. Saichō also studied Chinese Esoteric Buddhism under two Chinese esoteric masters ( ācāryas): Shunxiao and Weixiang, from whom he received initiation into the dual-realm mandalas. Furthermore, Saichō received Chan (Zen

Zen (; from Chinese: ''Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka phil ...

) teachings in China from the Oxhead (Jp. Gozu) school and Northern schools. He was a student of the Oxhead master Shunian (Shukunen), who resided at Chanlinsi (Zenrinji) Temple.Kūkai

, born posthumously called , was a Japanese Buddhist monk, calligrapher, and poet who founded the Vajrayana, esoteric Shingon Buddhism, Shingon school of Buddhism. He travelled to China, where he studied Tangmi (Chinese Vajrayana Buddhism) und ...

. He helped establish the new ordination platform on Mount Hiei.

* Ennin (円仁, 794-864) – A direct disciple of Saichō who traveled to China to study further, who was the first to write scholastic works on the union of esoteric practices with exoteric Tendai School theories (this merger is now known as "Taimitsu"). He also promoted Chinese nianfo practices.

* Enchin (円珍, 814–891) – Gishin's successor, junior to Ennin. He traveled to China and studied further esoteric teachings with different masters there. He then worked to assimilate esoteric buddhism to Tendai, and was also a notable administrator.

* Annen (安然, 841–889?) - Ennin's disciple and successor to Henjō. An influential thinker who's known having finalized the assimilation of esoteric and exoteric buddhism within Tendai.

* Sō-ō (相應, 831-918), who developed the '' kaihōgyō'' ("circling the mountain")

* Ryōgen (良源, 912–985) – Annen's successor, and skilled politician who helped ally the Tendai School with the Fujiwara clan

The was a powerful family of imperial regents in Japan, descending from the Nakatomi clan and, as legend held, through them their ancestral god Ame-no-Koyane. The Fujiwara prospered since ancient times and dominated the imperial court until th ...

.

* Genshin

, also known as , was a prominent Japanese monk of the Tendai school, recognized for his significant contributions to both Tendai and Pure Land Buddhism. Genshin studied under Ryōgen, a key reformer of the Tendai tradition, and became well kn ...

(源信, 942–1017) – Famous for his writings on Pure Land Buddhism

Pure Land Buddhism or the Pure Land School ( zh, c=淨土宗, p=Jìngtǔzōng) is a broad branch of Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhism focused on achieving rebirth in a Pure land, Pure Land. It is one of the most widely practiced traditions of East Asi ...

, particularly his ''Ōjōyōshū

The was an influential medieval Buddhism, Buddhist text composed in 985 by the Japanese Buddhist monk Genshin. The text is a comprehensive analysis of Buddhist practices related to rebirth in the Pure Land of Amitābha, Amida Buddha, drawing upon ...

''. Influenced Hōnen's Jōdo-shū tradition and later Tendai Pure Land.

* Sengaku (1203 – c. 1273) – a Tendai scholar and literary critic, who authored an influential commentary on the '' Man'yōshū'', the oldest extant Japanese poetry.

* Shinsei Shōnin (1443–1495) – Founder of the Tendai Shinsei school, who promoted precepts and Nembutsu practice.

* Tenkai (天海, 1536–1643) – a Tendai , who served as an entrusted advisor of Tokugawa Ieyasu

Tokugawa Ieyasu (born Matsudaira Takechiyo; 31 January 1543 – 1 June 1616) was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan, which ruled from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was the third of the three "Gr ...

, the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868.

The Tokugawa shogunate was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu after victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, ending the civil wars ...

.

Founders of new Kamakura schools

During the Kamakura period

The is a period of History of Japan, Japanese history that marks the governance by the Kamakura shogunate, officially established in 1192 in Kamakura, Kanagawa, Kamakura by the first ''shōgun'' Minamoto no Yoritomo after the conclusion of the G ...

, numerous Tendai monastics founded new schools of Japanese Buddhism, today known as the schools of New "Kamakura Buddhism". All of them were initially ordained and trained at the Tendai center on Mount Hiei. Key figures include:Jōdo Shinshū

, also known as Shin Buddhism or True Pure Land Buddhism, is a school of Pure Land Buddhism founded by the former Tendai Japanese monk Shinran.

Shin Buddhism is the most widely practiced branch of Buddhism in Japan.

History

Shinran (founder)

S ...

school, who emphasized salvation through Amida Buddha’s Other-Power.

* Dōgen Zenji (1200–1253): Founder of the Japanese Sōtō Zen school, who taught ''shikan taza'' (just sitting) meditation.

* Nichiren Shōnin (1222–1282): Founder of the Nichiren school, who propagated exclusive devotion to the ''Lotus Sutra''.

See also

* Enryaku-ji, the headquarters of Tendai Buddhism on Mount Hiei

* Hongaku

* Kaihōgyō

* Nichiren Buddhism, which developed the Tendai emphasis on the Lotus Sutra into a distinctive Japanese Buddhist school

* Tiantai Buddhism, the Chinese sect that Tendai developed from

Notes

References

* Chappell, David W. (1987)

"Is Tendai Buddhism Relevant to the Modern World?"