Austro-Turkish War (1683–1699) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Great Turkish War () or The Last Crusade, also called in Ottoman sources The Disaster Years (), was a series of conflicts between the

The Great Turkish War () or The Last Crusade, also called in Ottoman sources The Disaster Years (), was a series of conflicts between the

After a few years of peace, the Ottoman Empire, encouraged by successes in the west of the

After a few years of peace, the Ottoman Empire, encouraged by successes in the west of the

After allied Christian forces had captured Buda from the Ottoman Empire in 1686 during the Great Turkish War, Serbs from Pannonian Plain (present-day

After allied Christian forces had captured Buda from the Ottoman Empire in 1686 during the Great Turkish War, Serbs from Pannonian Plain (present-day

Capturing Vienna had long been a strategic aspiration of the Ottoman Empire, because of its interlocking control over Danubian (Black Sea to Western Europe) southern Europe, and the overland (Eastern Mediterranean to Germany) trade routes. During the years preceding this second siege ( the first had taken place in 1529), under the auspices of Grand viziers from the influential

Capturing Vienna had long been a strategic aspiration of the Ottoman Empire, because of its interlocking control over Danubian (Black Sea to Western Europe) southern Europe, and the overland (Eastern Mediterranean to Germany) trade routes. During the years preceding this second siege ( the first had taken place in 1529), under the auspices of Grand viziers from the influential  During early September, the experienced 5,000 Ottoman

During early September, the experienced 5,000 Ottoman

The relief army had to act quickly to save the city and so prevent another long siege. Despite the binational composition of the army and the short space of only six days, an effective leadership structure was established, centred on the Polish king and his

The relief army had to act quickly to save the city and so prevent another long siege. Despite the binational composition of the army and the short space of only six days, an effective leadership structure was established, centred on the Polish king and his

At around 6:00 pm, the Polish king ordered the cavalry to attack in four groups, three Polish and one from the Holy Roman Empire. Eighteen thousand horsemen charged down the hills, the largest cavalry charge in history. Sobieski led the charge at the head of 3,000 Polish heavy lancers, the famed "Winged Hussars". The Lipka Tatars who fought on the Polish side wore a sprig of straw in their helmets to distinguish themselves from the Tatars fighting on the Ottoman side. The charge easily broke the lines of the Ottomans, who were exhausted and demoralised and soon started to flee the battlefield. The cavalry headed straight for the Ottoman camps and Kara Mustafa's headquarters, while the remaining Viennese garrison sallied out of its defences to join in the assault.

The Ottoman troops were tired and dispirited following the failure of both the attempt at sapping and the assault on the city and the advance of the Holy League infantry on the Turkenschanz. The cavalry charge was one last deadly blow. Less than three hours after the cavalry attack, the Christian forces had won the battle and saved Vienna. The first Christian officer who entered Vienna was Margrave Ludwig of Baden, at the head of his dragoons.''The Enemy at the Gate'', Andrew Wheatcroft. 2008.

Afterwards, Sobieski paraphrased

At around 6:00 pm, the Polish king ordered the cavalry to attack in four groups, three Polish and one from the Holy Roman Empire. Eighteen thousand horsemen charged down the hills, the largest cavalry charge in history. Sobieski led the charge at the head of 3,000 Polish heavy lancers, the famed "Winged Hussars". The Lipka Tatars who fought on the Polish side wore a sprig of straw in their helmets to distinguish themselves from the Tatars fighting on the Ottoman side. The charge easily broke the lines of the Ottomans, who were exhausted and demoralised and soon started to flee the battlefield. The cavalry headed straight for the Ottoman camps and Kara Mustafa's headquarters, while the remaining Viennese garrison sallied out of its defences to join in the assault.

The Ottoman troops were tired and dispirited following the failure of both the attempt at sapping and the assault on the city and the advance of the Holy League infantry on the Turkenschanz. The cavalry charge was one last deadly blow. Less than three hours after the cavalry attack, the Christian forces had won the battle and saved Vienna. The first Christian officer who entered Vienna was Margrave Ludwig of Baden, at the head of his dragoons.''The Enemy at the Gate'', Andrew Wheatcroft. 2008.

Afterwards, Sobieski paraphrased

After the Ottoman army was defeated at Vienna, the Imperial army and its allied Polish troops began a counteroffensive to conquer

After the Ottoman army was defeated at Vienna, the Imperial army and its allied Polish troops began a counteroffensive to conquer

In October 1685, the Venetian army retreated to the Ionian Islands for winter quarters, where a plague broke out, something which would occur regularly in the next years, and take a great toll on the Venetian army, especially among the German contingents. In April 1686, the Venetians helped repulse an Ottoman attack that threatened to overrun Mani, and were reinforced from the Papal States and

In October 1685, the Venetian army retreated to the Ionian Islands for winter quarters, where a plague broke out, something which would occur regularly in the next years, and take a great toll on the Venetian army, especially among the German contingents. In April 1686, the Venetians helped repulse an Ottoman attack that threatened to overrun Mani, and were reinforced from the Papal States and  Despite losses to the plague during the autumn and winter of 1686, Morosini's forces were replenished by the arrival of new German mercenary corps from

Despite losses to the plague during the autumn and winter of 1686, Morosini's forces were replenished by the arrival of new German mercenary corps from

an

at History of Warfare, World History at KMLA A new Holy League was initiated by

Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century

' (Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society, 1991) * . * . * Wolf, John B. ''The Emergence of the Great Powers: 1685–1715'' (1951), pp 15–53.

The Great Turkish War () or The Last Crusade, also called in Ottoman sources The Disaster Years (), was a series of conflicts between the

The Great Turkish War () or The Last Crusade, also called in Ottoman sources The Disaster Years (), was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

and the Holy League consisting of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, Poland-Lithuania, Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, and the Kingdom of Hungary. Intensive fighting began in 1683 and ended with the signing of the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699. The war was a resounding defeat for the Ottoman Empire, which for the first time lost substantial territory, in Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, as well as in part of the western Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

. The war was significant also for being the first instance of Russia joining an alliance with Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

. Historians have labeled the war as the Fourteenth Crusade launched against the Turks by the papacy.

The French did not join the Holy League, as France had agreed to reviving an informal Franco-Ottoman alliance

The Franco-Ottoman alliance, also known as the Franco-Turkish alliance, was an alliance established in 1536 between Francis I of France, Francis I, King of France and Suleiman the Magnificent, Suleiman I of the Ottoman Empire. The strategic and s ...

in 1673, in exchange for Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

being recognized as a protector of Catholics in the Ottoman domains.

Initially Louis XIV took advantage of the conflict to extend France's eastern borders, seizing Luxembourg in the War of the Reunions, but deciding that it was unseemly to be fighting the Holy Roman Empire at the same time of its struggle with the Ottomans, he agreed to the Truce of Ratisbon in 1684. However, as the Holy League made gains against the Ottoman Empire, capturing Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

by 1688, the French began to worry that their Habsburg rivals would grow too powerful and eventually turn on France. Therefore, the French besieged Philippsburg on 27 September 1688, breaking the truce and triggering the separate Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War was a European great power conflict from 1688 to 1697 between Kingdom of France, France and the Grand Alliance (League of Augsburg), Grand Alliance. Although largely concentrated in Europe, fighting spread to colonial poss ...

against the Grand Alliance, which included the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

, the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, and after the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

, England as well. The war drew Imperial resources to the west and relieved the Turks. This was partially compensated by the entrance of Russia into the war in 1687. While the war started off with the Ottomans facing Imperial forces in the west, the Venetians to the south, and Poland-Lithuania to the north, the majority of Turkish forces were always on the western front and Imperial troops also served on the other fronts.

As a result, the advance made by the Holy League stalled, allowing the Ottomans to retake Belgrade in 1690. The war then fell into a stalemate, and peace was concluded in 1699 which began following the Battle of Zenta in 1697 when an Ottoman attempt to retake their lost possessions in Hungary was crushed by the Holy League.

The war largely overlapped with the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), which took up the vast majority of the Habsburgs' attention while it was active. In 1695, for instance, the Holy Roman Empire states had 280,000 troops in the field, with England, the Dutch Republic, and Spain contributing another 156,000, specifically to the conflict against France. Of those 280,000, only 74,000, or about one quarter, were positioned against the Turks; the rest were fighting France. Overall, from 1683 to 1699, the Imperial States had on average 88,100 men fighting the Turks, while from 1688 to 1697, they had on average 127,410 fighting the French.

Background (1667–1683)

FollowingBohdan Khmelnytsky

Zynoviy Bohdan Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky of the Abdank coat of arms (Ruthenian language, Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богданъ Хмелнiцкiи; modern , Polish language, Polish: ; 15956 August 1657) was a Ruthenian nobility, Ruthenian noble ...

's rebellion

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

, the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia, also known as the Tsardom of Moscow, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of tsar by Ivan the Terrible, Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter the Great in 1721.

...

in 1654 acquired territories from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

(currently parts of eastern Ukraine), while some Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

stayed in the southeastern part of the Commonwealth. Their leader, Petro Doroshenko, sought the Ottoman Empire's protection and in 1667 attacked Polish commander John Sobieski.

Sultan Mehmed IV, who knew that the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was weakened by internal conflicts, in August 1672 attacked Kamenets Podolski, a large city on the border of the Commonwealth. The small Polish force resisted the siege of Kamenets for two weeks but was then forced to surrender. The Polish army was too small to resist the Ottoman invasion and could score only some minor tactical victories. After three months, the Poles were forced to sign the Treaty of Buchach in which they agreed to cede Kamenets, Podolia and to pay tribute to the Ottomans. When the news of the defeat and treaty terms reached Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

, the Sejm

The Sejm (), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (), is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of the Third Polish Republic since the Polish People' ...

refused to pay the tribute and organized a large army under Sobieski; subsequently, the Poles won the Battle of Khotyn (1673)

The Battle of Khotyn or Battle of Chocim, also known as the Hotin War, took place on 11 November 1673 in Khotyn, where the forces of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth under the Hetmans of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Grand Hetman ...

. After the death of King Michael in 1673, Sobieski was elected king of Poland. He tried to defeat the Ottomans for four years, with no success. The war ended on 17 October 1676 with the Treaty of Żurawno in which the Turks retained control over only Kamenets-Podolski. This Turkish attack also led in 1676 to the beginning of the Russo-Turkish Wars

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

.

Overview

After a few years of peace, the Ottoman Empire, encouraged by successes in the west of the

After a few years of peace, the Ottoman Empire, encouraged by successes in the west of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, attacked the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

. The Turks almost captured Vienna, but John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( (); (); () 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobieski was educated at the Jagiellonian University and toured Eur ...

led a Christian alliance that defeated them in the Battle of Vienna (1683), stalling the Ottoman Empire's hegemony in south-eastern Europe.

A new Holy League was initiated by Pope Innocent XI

Pope Innocent XI (; ; 16 May 1611 – 12 August 1689), born Benedetto Odescalchi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 21 September 1676 until his death on 12 August 1689.

Political and religious tensions with ...

and encompassed the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

(headed by the Habsburg monarchy), the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

and the Venetian Republic in 1684,Treasure, Geoffrey 1985, ''The making of modern Europe, 1648–1780'', Methuen & Co, 614. joined by Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

in 1686. Holy League's troops besieged and in 1686 conquered Buda, which had been under Ottoman rule since 1541. The second battle of Mohács (1687) was a crushing defeat for the Sultan. The Turks were more successful on the Polish front and were able to retain Podolia during their battles with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Russia's involvement marked the first time the country formally joined an alliance of European powers. This was the beginning of a series of Russo-Turkish Wars

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

, the last of which was part of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. As a result of the Crimean campaigns and Azov campaigns, Russia captured the key Ottoman fortress of Azov.

Following the decisive Battle of Zenta in 1697 and lesser skirmishes (such as the Battle of Podhajce in 1698), the League won the war in 1699 and forced the Ottoman Empire to sign the Treaty of Karlowitz.Sicker, Martin 2001, ''The Islamic world in decline'', Praeger Publishers, 32. The Ottomans ceded most of Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

and Slavonia

Slavonia (; ) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria County, Istria, one of the four Regions of Croatia, historical regions of Croatia. Located in the Pannonian Plain and taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with f ...

, as well as parts of Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

, to the Habsburg monarchy while Podolia returned to Poland. Most of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

passed to Venice, along with the Morea, which the Ottomans reconquered in 1715 and regained in the Treaty of Passarowitz of 1718.

Serbia

Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, Slavonia

Slavonia (; ) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria County, Istria, one of the four Regions of Croatia, historical regions of Croatia. Located in the Pannonian Plain and taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with f ...

region in present-day Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

, Bačka

Bačka ( sr-Cyrl, Бачка, ) or Bácska (), is a geographical and historical area within the Pannonian Plain bordered by the river Danube to the west and south, and by the river Tisza to the east. It is divided between Serbia and Hungary. ...

and Banat

Banat ( , ; ; ; ) is a geographical and Historical regions of Central Europe, historical region located in the Pannonian Basin that straddles Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. It is divided among three countries: the eastern part lie ...

regions in present-day Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

) joined the troops of the Habsburg monarchy as separate units known as Serbian Militia. Serbs, as volunteers, massively joined the Habsburg side. In the first half of 1688, the Habsburg army, together with units of Serbian Militia, captured Gyula, Lippa ''(today Lipova, Romania)'' and Borosjenő ''(today Ienu, Romania)'' from the Ottoman Empire. After the capture of Belgrade from the Ottomans in 1688, Serbs from the territories in the south of the Sava

The Sava, is a river in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, a right-bank and the longest tributary of the Danube. From its source in Slovenia it flows through Croatia and along its border with Bosnia and Herzegovina, and finally reac ...

and Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

rivers began to join Serbian Militia units.

Kosovo

The Roman Catholic bishop and philosopher Pjetër Bogdani returned to theBalkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

in March 1686 and spent the next years promoting resistance to the armies of the Ottoman Empire, in particular in his native Kosovo

Kosovo, officially the Republic of Kosovo, is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe with International recognition of Kosovo, partial diplomatic recognition. It is bordered by Albania to the southwest, Montenegro to the west, Serbia to the ...

. He and his vicar Toma Raspasani played a leading role in the pro-Austrian movement in Kosovo during the Great Turkish War. He contributed a force of 6,000 Albanian soldiers to the Austrian army which had arrived in Pristina

Pristina or Prishtina ( , ), . is the capital and largest city of Kosovo. It is the administrative center of the eponymous municipality and District of Pristina, district.

In antiquity, the area of Pristina was part of the Dardanian Kingdo ...

and accompanied it to capture Prizren

Prizren ( sq-definite, Prizreni, ; sr-cyr, Призрен) is the second List of cities and towns in Kosovo, most populous city and Municipalities of Kosovo, municipality of Kosovo and seat of the eponymous municipality and District of Prizren, ...

. There, however, he and much of his army were met by another equally formidable adversary, the plague. Bogdani returned to Pristina but succumbed to the disease there on 6 December 1689. His nephew, Gjergj Bogdani, reported in 1698 that his uncle's remains were later exhumed by Turkish and Tatar soldiers and fed to the dogs in the middle of the square in Pristina.

Sources from 1690 report that the "Germans" in Kosovo have made contact with 20,000 Albanians who have turned their weapons against the Turks.

Battle of Vienna

Capturing Vienna had long been a strategic aspiration of the Ottoman Empire, because of its interlocking control over Danubian (Black Sea to Western Europe) southern Europe, and the overland (Eastern Mediterranean to Germany) trade routes. During the years preceding this second siege ( the first had taken place in 1529), under the auspices of Grand viziers from the influential

Capturing Vienna had long been a strategic aspiration of the Ottoman Empire, because of its interlocking control over Danubian (Black Sea to Western Europe) southern Europe, and the overland (Eastern Mediterranean to Germany) trade routes. During the years preceding this second siege ( the first had taken place in 1529), under the auspices of Grand viziers from the influential Köprülü family Köprülü may refer to:

People

* Köprülü family (Kypriljotet), an Ottoman noble family of Albanian origin

** Köprülü era (1656–1703), the period in which the Ottoman Empire's politics were set by the Grand Viziers, mainly the Köprülü fa ...

, the Ottoman Empire undertook extensive logistical preparations, including the repair and establishment of roads and bridges leading into the Holy Roman Empire and its logistical centres, as well as the forwarding of ammunition, cannon and other resources from all over the Ottoman Empire to these centres and into the Balkans. Since 1679, the Great Plague had been ravaging Vienna.

The main Ottoman army finally laid siege to Vienna on 14 July 1683. On the same day, Kara Mustafa Pasha sent the traditional demand for surrender to the city. Ernst Rüdiger Graf von Starhemberg, leader of the garrison of 15,000 troops and 8,700 volunteers with 370 cannon, refused to capitulate. Only days before, he had received news of the mass slaughter at Perchtoldsdorf, a town south of Vienna, where the citizens had handed over the keys of the city after having been given a similar choice. Siege operations started on 17 July.

On 6 September, the Poles under John III Sobieski crossed the Danube 30 km north-west of Vienna at Tulln

Tulln an der Donau () is a historic town in the Austrian state of Lower Austria, the administrative seat of Tulln District. Because of its abundance of parks and gardens, Tulln is often referred to as ''Blumenstadt'' ("City of Flowers"), and "The ...

to unite with the Imperial troops and the additional forces from Saxony, Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

, Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in southern Germany. In earlier times it was considered to be on both sides of the Upper Rhine, but since the Napoleonic Wars, it has been considered only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Ba ...

, Franconia

Franconia ( ; ; ) is a geographical region of Germany, characterised by its culture and East Franconian dialect (). Franconia is made up of the three (governmental districts) of Lower Franconia, Lower, Middle Franconia, Middle and Upper Franco ...

, and Swabia

Swabia ; , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of Swabia, one of ...

. Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

of France declined to help his Habsburg rival, having just annexed Alsace. An alliance between Sobieski and the Emperor Leopold I resulted in the addition of the Polish hussars to the already existing allied army. The command of the forces of European allies was entrusted to the Polish king, who had under his command 70,000–80,000 soldiers facing a Turkish army of 150,000.Tucker, S.C., 2010, ''A Global Chronology of Conflict'', Vol. Two, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, LLC, Sobieski's courage and remarkable aptitude for command were already known in Europe.

During early September, the experienced 5,000 Ottoman

During early September, the experienced 5,000 Ottoman sapper

A sapper, also called a combat engineer, is a combatant or soldier who performs a variety of military engineering duties, such as breaching fortifications, demolitions, bridge-building, laying or clearing minefields, preparing field defenses ...

s had repeatedly blown up large portions of the walls between the Burg bastion

A bastion is a structure projecting outward from the curtain wall of a fortification, most commonly angular in shape and positioned at the corners of the fort. The fully developed bastion consists of two faces and two flanks, with fire from the ...

, the Löbel bastion and the Burg ravelin, creating gaps of about 12m in width. The Viennese tried to counter this by digging their own tunnels to intercept the depositing of large amounts of gunpowder in caverns. The Ottomans finally managed to occupy the Burg ravelin and the low wall in that area on 8 September. Anticipating a breach in the city walls, the remaining Viennese prepared to fight in the inner city.

Staging the battle

The relief army had to act quickly to save the city and so prevent another long siege. Despite the binational composition of the army and the short space of only six days, an effective leadership structure was established, centred on the Polish king and his

The relief army had to act quickly to save the city and so prevent another long siege. Despite the binational composition of the army and the short space of only six days, an effective leadership structure was established, centred on the Polish king and his Hussars

A hussar, ; ; ; ; . was a member of a class of light cavalry, originally from the Kingdom of Hungary during the 15th and 16th centuries. The title and distinctive dress of these horsemen were subsequently widely adopted by light cavalry ...

. The Holy League settled the issues of payment by using all available funds from the government, loans from several wealthy bankers and noblemen and large sums of money from the Pope.Stoye, John. ''The Siege of Vienna: The Last Great Trial between Cross & Crescent''. 2011 Also, the Habsburgs and Poles agreed that the Polish government would pay for its own troops while still in Poland, but that they would be paid by the Emperor once they had crossed into Imperial territory. However, the Emperor had to recognise Sobieski's claim to first rights of plunder of the enemy camp in the event of a victory.

Kara Mustafa Pasha was less effective at ensuring his forces' motivation and loyalty, and preparing for the expected relief-army attack. He had entrusted defence of the rear to the Khan of Crimea and his light cavalry force, which numbered about 30,000–40,000. There is doubt as to how far the Tatars participated in the final battle before Vienna.

The Ottomans could not rely on their Wallachian and Moldavian allies. George Ducas

George Ducas ( – 31 March 1685) was the prince (List of monarchs of Moldavia, voivode) of Moldavia (1665–1666, 1668–1672, 1678–1684) and the List of Wallachian rulers, prince of Wallachia (1674–1678). He also served as the hetman of ...

, Prince of Moldavia

This is a list of monarchs of Moldavia, from the first mention of the medieval polity east of the Carpathians and until its disestablishment in 1862, when it united with Wallachia, the other Danubian Principality, to form the modern-day state of ...

, was captured, while Șerban Cantacuzino

Șerban Cantacuzino (), (1634/1640 – 29 October 1688) was a List of rulers of Wallachia, Prince of Wallachia between 1678 and 1688.

Biography

Șerban Cantacuzino was a member of the Romanian branch of the Cantacuzino family, Cantacuzino noble ...

's forces joined the retreat after Sobieski's cavalry charge.Varvounis, M., 2012, ''Jan Sobieski'', Xlibris,

The confederated troops signalled their arrival on the Kahlenberg above Vienna with bonfires. Before the battle a Mass was celebrated for the King of Poland and his nobles.

Battle

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

's famous quotation in saying "" – "I came, I saw, God conquered".

Reconquest of Hungary

After the Ottoman army was defeated at Vienna, the Imperial army and its allied Polish troops began a counteroffensive to conquer

After the Ottoman army was defeated at Vienna, the Imperial army and its allied Polish troops began a counteroffensive to conquer Ottoman Hungary

Ottoman Hungary () encompassed the parts of the Kingdom of Hungary which were under the rule of the Ottoman Empire from the occupation of Buda in 1541 until the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699. The territory was incorporated into the empire, under ...

. After the Victory at Párkány in October 1683, Esztergom

Esztergom (; ; or ; , known by Names of European cities in different languages: E–H#E, alternative names) is a city with county rights in northern Hungary, northwest of the capital Budapest. It lies in Komárom-Esztergom County, on the righ ...

was forced to surrender after a short siege.

Field Marshal Aeneas de Caprara defeated the Ottoman Army near the city of Kassa in 1685. After the Ottoman field army was defeated near Esztergom in 1685, the cities besieged by the Imperial forces could no longer count on relief. Érsekújvár (Nové Zámky) fell

A fell (from Old Norse ''fell'', ''fjall'', "mountain"Falk and Torp (2006:161).) is a high and barren landscape feature, such as a mountain or Moorland, moor-covered hill. The term is most often employed in Fennoscandia, Iceland, the Isle of M ...

on 19 August, soon afterwards also the places Eperies, Kaschau, and Tokaj

Tokaj () is a historical town in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén county, Northern Hungary, 54 kilometers from county capital Miskolc. It is the centre of the Tokaj-Hegyalja wine district where Tokaji wine is produced.

History

The wine-growing area ...

.

In 1686, two years after an unsuccessful siege of Buda, a renewed European campaign was started to enter Buda

Buda (, ) is the part of Budapest, the capital city of Hungary, that lies on the western bank of the Danube. Historically, “Buda” referred only to the royal walled city on Castle Hill (), which was constructed by Béla IV between 1247 and ...

. In June 1686, the Duke of Lorraine besieged Buda (Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

), the centre of Ottoman Hungary and the old royal capital. After resisting for 78 days, the city fell on 2 September, and Turkish resistance collapsed throughout the region as far away as Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

and Serbia.

In 1687, the Ottomans raised new armies and marched north once more. However, Charles V, Duke of Lorraine intercepted the Turks at the Second Battle of Mohács and avenged the loss inflicted over 160 years ago by Suleiman the Magnificent. Such was the scale of their defeat that the Ottoman army mutinied—a revolt which spread to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

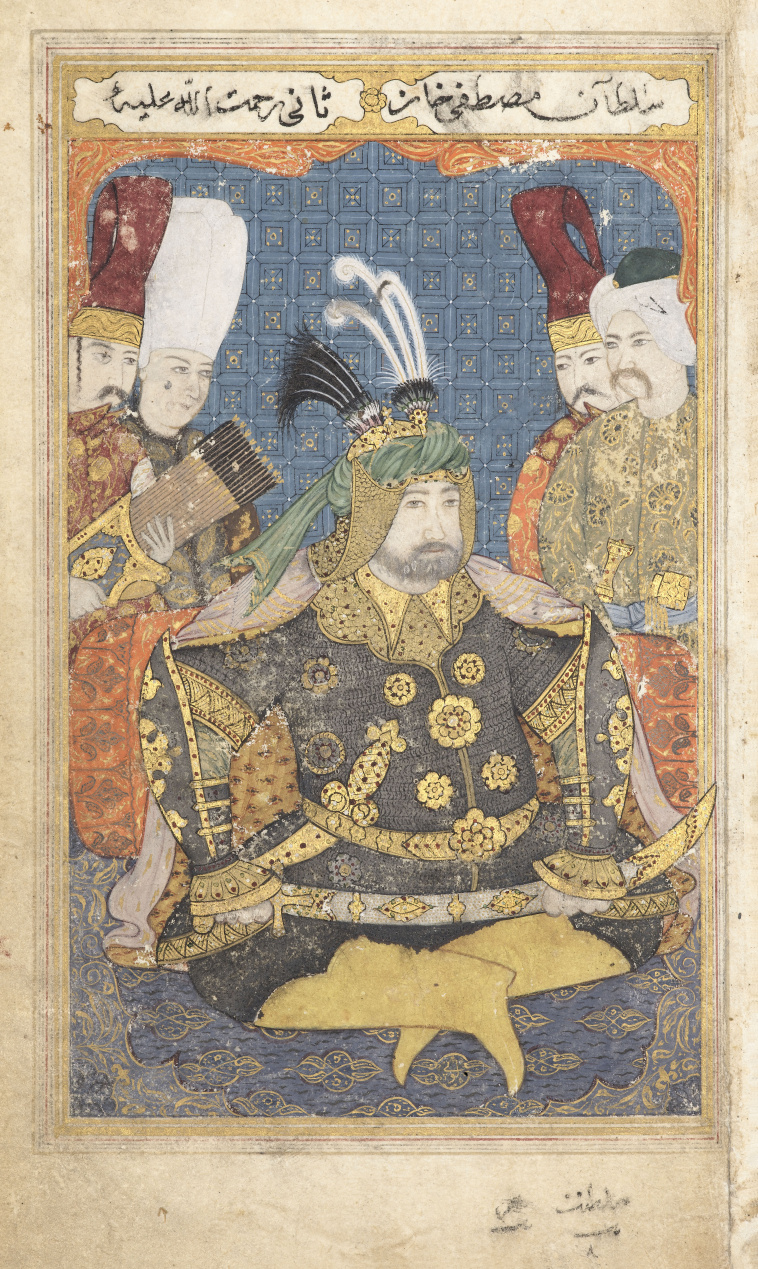

. The Grand Vizier, Sarı Süleyman Pasha, was executed and Sultan Mehmed IV deposed.

Only when the Ottomans suffered yet another disastrous battle at the Battle of Zenta in 1697 did the Ottomans sue for peace; the resulting Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 secured territories, the rest of Hungary and overlordship of Transylvania for the Austrians. Throughout Europe Protestants and Catholics hailed Prince Eugene of Savoy

Prince Eugene Francis of Savoy-Carignano (18 October 1663 – 21 April 1736), better known as Prince Eugene, was a distinguished Generalfeldmarschall, field marshal in the Army of the Holy Roman Empire and of the Austrian Habsburg dynasty durin ...

as "the savior of Christendom".

Balkan campaign

The distractions of the war againstLouis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

had enabled the Turks to recapture Belgrade in 1690. In August 1691, the Austrians, under Louis of Baden, regained the advantage by heavily defeating the Turks at the Battle of Slankamen on the Danube, securing Habsburg possession of Hungary and Transylvania.

While the Ottoman army was in the process of crossing the Tisza

The Tisza, Tysa or Tisa (see below) is one of the major rivers of Central and Eastern Europe. It was once called "the most Hungarian river" because it used to flow entirely within the Kingdom of Hungary. Today, it crosses several national bo ...

River near Zenta, it was engaged in a surprise attack by Habsburg Imperial forces commanded by Prince Eugene of Savoy. His victory at Zenta had turned him into a European hero. After a brief raid into Ottoman Bosnia, culminating in the sack of Sarajevo, Eugene returned to Vienna in November 1697 to a triumphal reception.

Associated wars

Morean War

TheRepublic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

had held several islands in the Aegean and the Ionian seas, together with strategically positioned forts along the coast of the Greek mainland since the carving up of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

after the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

. However, with the rise of the Ottomans, during the 16th and early 17th centuries, they lost most of these, such as Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

and Euboea ( Negropont) to the Turks. Between 1645 and 1669, the Venetians and the Ottomans fought a long and costly war over Crete, the last major Venetian possession in the Aegean. During this war, the Venetian commander, Francesco Morosini, came into contact with the rebellious Maniots

The Maniots () or Maniates () are an ethnic Greeks, Greek subgroup that traditionally inhabit the Mani Peninsula; located in western Laconia and eastern Messenia, in the southern Peloponnese, Greece. They were also formerly known as Mainotes, an ...

, for a joint campaign in the Morea. In 1659, Morosini landed in the Morea

Morea ( or ) was the name of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The name was used by the Principality of Achaea, the Byzantine province known as the Despotate of the Morea, by the O ...

, and together with the Maniots, he took Kalamata

Kalamata ( ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece after Patras, and the largest city of the Peloponnese (region), homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia regiona ...

. However, he was soon after forced to return to Crete, and the Peloponnesian venture failed.

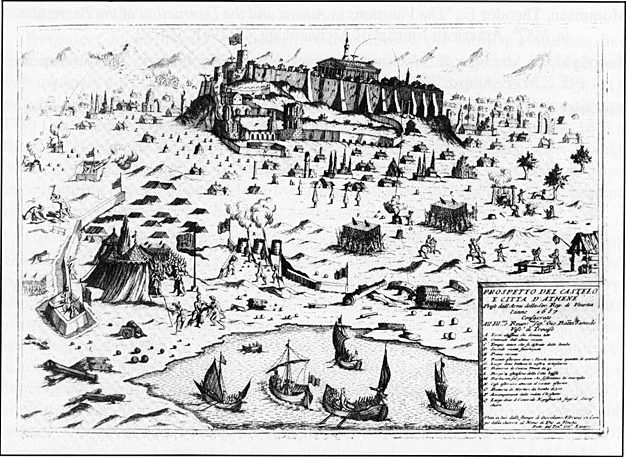

In 1683, a new war broke out between the Habsburg monarchy and the Ottomans, with a large Ottoman army advancing towards Vienna. In response to this, a Holy League was formed. After the Ottoman army was defeated in the Battle of Vienna, the Venetians decided to use the opportunity of the weakening of Ottoman power and its distraction in the Danubian front so as to reconquer its lost territories in the Aegean and Dalmatia. On 25 April 1684, the Most Serene Republic declared war on the Ottomans.

Aware that it would have to rely on its own strength for success, Venice prepared for the war by securing financial and military aid in men and ships from Hospitaller Malta, the Duchy of Savoy

The Duchy of Savoy (; ) was a territorial entity of the Savoyard state that existed from 1416 until 1847 and was a possession of the House of Savoy.

It was created when Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, raised the County of Savoy into a duchy f ...

, the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

, and the Knights of St. Stephen. In addition, the Venetians enrolled large numbers of mercenaries from Italy and the German states, especially Saxony

Saxony, officially the Free State of Saxony, is a landlocked state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, and Bavaria, as well as the countries of Poland and the Czech Republic. Its capital is Dresden, and ...

and Brunswick.

Operations in the Ionian Sea

In mid-June, the Venetian fleet moved from the Adriatic towards the Ottoman-heldIonian Islands

The Ionian Islands (Modern Greek: , ; Ancient Greek, Katharevousa: , ) are a archipelago, group of islands in the Ionian Sea, west of mainland Greece. They are traditionally called the Heptanese ("Seven Islands"; , ''Heptanēsa'' or , ''Heptanē ...

. The first target was the island of Lefkada

Lefkada (, ''Lefkáda'', ), also known as Lefkas or Leukas (Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: Λευκάς, ''Leukás'', modern pronunciation ''Lefkás'') and Leucadia, is a Greece, Greek list of islands of Greece, island in the Ionian Sea on the ...

(Santa Maura), which fell, after a siege of 16 days, on 6 August 1684. The Venetians, aided by Greek irregulars, then crossed into the mainland and started raiding the opposite shore of Acarnania

Acarnania () is a region of west-central Greece that lies along the Ionian Sea, west of Aetolia, with the Achelous River for a boundary, and north of the gulf of Calydon, which is the entrance to the Gulf of Corinth. Today it forms the western part ...

. Most of the area was soon under Venetian control, and the fall of the forts of Preveza

Preveza (, ) is a city in the region of Epirus (region), Epirus, northwestern Greece, located on the northern peninsula of the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf. It is the capital of the Preveza (regional unit), regional unit of Preveza, which is the s ...

and Vonitsa in late September removed the last Ottoman bastions. These early successes were important for the Venetians not only for reasons of morale, but because they secured their communications with Venice, denied to the Ottomans the possibility of threatening the Ionian Islands or of ferrying troops via western Greece to the Peloponnese, and because these successes encouraged the Greeks to cooperate with them against the Ottomans.

The conquest of the Morea

Having secured his rear during the previous year, Morosini set his sights upon the Peloponnese, where the Greeks, especially the Maniots, had begun showing signs of revolt and communicated with Morosini, promising to rise up in his aid. Ismail Pasha, the new military commander of Morea, learned of this and invaded the Mani Peninsula with 10,000 men, reinforcing the three forts that the Ottomans already garrisoned, and compelled the Maniots to give up hostages to secure their loyalty. As a result, the Maniots remained uncommitted when, on 25 June 1685, the Venetian army, 8,100 men strong, landed outside the former Venetian fort of Koroni and laid siege to it. The castle surrendered after 49 days, on 11 August, and the garrison was massacred. After this success, Morosini embarked his troops towards the town ofKalamata

Kalamata ( ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece after Patras, and the largest city of the Peloponnese (region), homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia regiona ...

, in order to encourage the Maniots to revolt. The Venetian army, reinforced by 3,300 Saxons and under the command of general Hannibal von Degenfeld, defeated a Turkish force of ca. 10,000 outside Kalamata on 14 September, and by the end of the month, all of Mani and much of Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a prefecture (''nomos' ...

were under Venetian control.

In October 1685, the Venetian army retreated to the Ionian Islands for winter quarters, where a plague broke out, something which would occur regularly in the next years, and take a great toll on the Venetian army, especially among the German contingents. In April 1686, the Venetians helped repulse an Ottoman attack that threatened to overrun Mani, and were reinforced from the Papal States and

In October 1685, the Venetian army retreated to the Ionian Islands for winter quarters, where a plague broke out, something which would occur regularly in the next years, and take a great toll on the Venetian army, especially among the German contingents. In April 1686, the Venetians helped repulse an Ottoman attack that threatened to overrun Mani, and were reinforced from the Papal States and Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

. The Swedish marshal Otto Wilhelm Königsmarck was appointed head of the land forces, while Morosini retained command of the fleet. On 3 June Königsmarck took Pylos

Pylos (, ; ), historically also known as Navarino, is a town and a former Communities and Municipalities of Greece, municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part of ...

and proceeded to lay siege the fortress of Navarino. A relief force under Ismail Pasha was defeated on 16 June, and the next day the fort surrendered. The garrison and the Muslim population were transported to Tripoli. Methoni (Modon) followed on 7 July, after an effective bombardment destroyed the fort's walls, and its inhabitants were also transferred to Tripoli. The Venetians then advanced towards Argos and Nafplion, which was then the most important town in the Peloponnese. The Venetian army, ca. 12,000 strong, landed around Nafplion between 30 July and 4 August. Königsmarck immediately led an assault upon the hill of Palamidi, then unfortified, which overlooked the town. Despite the Venetians' success in capturing Palamidi, the arrival of a 7,000 strong Ottoman army under Ismail Pasha at Argos rendered their position difficult. The Venetians' initial assault against the relief army succeeded in taking Argos and forcing the pasha to retreat to Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

, but for two weeks, from 16 August, Königsmarck's forces were forced to continuously repulse attacks from Ismail Pasha's forces, fight off the sorties of the besieged Ottoman garrison and cope with a new outbreak of plague. On 29 August 1686 Ismail Pasha attacked the Venetian camp, but was heavily defeated. With the defeat of the relief army, Nafplion was forced to surrender on 3 September. News of this major victory were greeted in Venice with joy and celebration. Nafplion became the Venetians' major base, while Ismail Pasha withdrew to Achaea

Achaea () or Achaia (), sometimes transliterated from Greek language, Greek as Akhaia (, ''Akhaḯa'', ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Western Greece and is situated in the northwest ...

after strengthening the garrisons at Corinth, which controlled the passage to central Greece.

Despite losses to the plague during the autumn and winter of 1686, Morosini's forces were replenished by the arrival of new German mercenary corps from

Despite losses to the plague during the autumn and winter of 1686, Morosini's forces were replenished by the arrival of new German mercenary corps from Hanover

Hanover ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the States of Germany, German state of Lower Saxony. Its population of 535,932 (2021) makes it the List of cities in Germany by population, 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-l ...

in spring 1687. Thus strengthened, he was able to move against the last major Ottoman bastion in the Peloponnese, the town of Patras

Patras (; ; Katharevousa and ; ) is Greece's List of cities in Greece, third-largest city and the regional capital and largest city of Western Greece, in the northern Peloponnese, west of Athens. The city is built at the foot of Mount Panachaiko ...

and the fort

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from La ...

of Rion, which along with its twin at Antirrion controlled the entrance to the Corinthian Gulf (the "Little Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

"). On 22 July 1687, Morosini, with a force of 14,000, landed outside Patras, where the new Ottoman commander, Mehmed Pasha, had established himself. Mehmed, with an army of roughly equal size, attacked the Venetian force immediately after it landed, but was defeated and forced to retreat. At this point panic spread among the Ottoman forces, and the Venetians were able, within a few days, to capture the citadel of Patras, and the forts of Rion, Antirrion, and Nafpaktos (Lepanto) without any opposition, as their garrisons abandoned them. This new success caused great joy in Venice, and honours were heaped on Morosini and his officers. Morosini received the victory title "''Peloponnesiacus''", and a bronze bust of his was displayed in the Great Hall, something never before done for a living citizen. The Venetians followed up this success with the reduction of the last Ottoman bastions in the Peloponnese, including Corinth, which was occupied on 7 August, and Mystra, which surrendered later in the month. The Peloponnese was under complete Venetian control, and only the fort of Monemvasia

Monemvasia (, or ) is a town and municipality in Laconia, Greece. The town is located in mainland Greece on a tied island off the east coast of the Peloponnese, surrounded by the Myrtoan Sea. Monemvasia is connected to the rest of the mainland by a ...

(Malvasia) in the southeast continued to resist, holding out until 1690.

Polish–Ottoman & Austro-Turkish Wars (1683–1699)

After a few years of peace, the Ottoman Empire attacked the Habsburg monarchy again. The Turks almost captured Vienna, but King John III Sobieski of Poland led a Christian alliance that defeated them in the Battle of Vienna, which shook the Ottoman Empire's hegemony in south-eastern Europe.Polish-Ottoman War, 1683–1699an

at History of Warfare, World History at KMLA A new Holy League was initiated by

Pope Innocent XI

Pope Innocent XI (; ; 16 May 1611 – 12 August 1689), born Benedetto Odescalchi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 21 September 1676 until his death on 12 August 1689.

Political and religious tensions with ...

and encompassed the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

(headed by the Habsburg monarchy), joined by the Venetian Republic and Poland in 1684 and the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia, also known as the Tsardom of Moscow, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of tsar by Ivan the Terrible, Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter the Great in 1721.

...

in 1686. The Ottomans suffered three decisive defeats against the Holy Roman Empire after siege of Buda

Buda (, ) is the part of Budapest, the capital city of Hungary, that lies on the western bank of the Danube. Historically, “Buda” referred only to the royal walled city on Castle Hill (), which was constructed by Béla IV between 1247 and ...

: the second Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; , ) took place on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, in the Kingdom of Hungary. It was fought between the forces of Hungary, led by King Louis II of Hungary, Louis II, and the invading Ottoman Empire, commanded by Suleima ...

in 1687, the Battle of Slankamen in 1691 and the Battle of Zenta a decade later, in 1697.

On the smaller Polish front, after the battles of 1683 (Vienna and Parkany), Sobieski, after his proposal for the League to start a major coordinated offensive, undertook a rather unsuccessful offensive in Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

in 1686, with the Ottomans refusing a major engagement and harassing the army. For the next four years Poland would blockade the key fortress at Kamenets, and Ottoman Tatars would raid the borderlands. In 1691, Sobieski undertook another expedition to Moldavia, with slightly better results, but still with no decisive victories.

The last battle of the campaign was the Battle of Podhajce in 1698, where a Polish hetman named Feliks Kazimierz Potocki defeated the Ottoman incursion into the Commonwealth. The League won the war in 1699 and forced the Ottoman Empire to sign the Treaty of Karlowitz. The Ottomans thereby lost much of their European possessions, with Podolia (including Kamenets) returned to Poland.

Russo-Turkish War (1686–1700)

During the war, the Russian army organized the Crimean campaigns of 1687 and 1689, which both ended in Russian defeats. Despite these setbacks, Russia launched the Azov campaigns in 1695 and 1696, and after laying siege to Azov in 1695 successfully occupied the city in 1696.Conclusion

On 11 September 1697, the Battle of Zenta was fought just south of the Ottoman ruled town of Zenta. During the battle, Habsburg Imperial forces routed the Ottoman forces while the Ottomans were crossing the Tisa River near the town. This resulted in the Habsburg forces killing over 30,000 Ottomans and dispersing the rest. This crippling defeat was the ultimate factor of the Ottoman Empire signing the Treaty of Karlowitz on 22 January 1699, ending the Great Turkish War. This treaty resulted in the transfer of most of Ottoman Hungary to the Habsburgs, and after further losses in theAustro-Turkish War (1716–1718)

The Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718) was fought between Habsburg monarchy and the Ottoman Empire. The 1699 Treaty of Karlowitz was not an acceptable permanent agreement for the Ottoman Empire. Twelve years after Karlowitz, it began the long ...

, prompted the Ottomans to adopt a more defensive military policy in the following century.Virginia Aksan, ''Ottoman Wars, 1700–1860: An Empire Besieged'', (Pearson Education Ltd., 2007), 28.

See also

* Croatian-Slavonian-Dalmatian theater in Great Turkish War * Enea Silvio Piccolomini (general), among the first Christian victims of the war. * Scutum (constellation)References

Sources

* * * Setton, Kenneth Meyer.Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century

' (Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society, 1991) * . * . * Wolf, John B. ''The Emergence of the Great Powers: 1685–1715'' (1951), pp 15–53.

Further reading

* {{authority control 1680s conflicts 1690s conflicts 1680s in the Habsburg monarchy 1690s in the Habsburg monarchy 1680s in the Ottoman Empire 1690s in the Ottoman Empire 17th-century conflicts 17th century in the Habsburg monarchy 17th century in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth France–Ottoman Empire relations Habsburg monarchy–Ottoman Empire relations History of Central Europe History of Eastern Europe History of the Ottoman Empire in Europe Military history of Slovenia Military operations involving the Crimean Khanate Ottoman period in Moldova Ottoman period in Ukraine Ottoman Serbia Wars involving Austria Wars involving the Grand Duchy of Lithuania Wars involving Moldavia Wars involving Montenegro Wars involving Poland Wars involving Slovenia Wars involving the Ottoman Empire Wars involving the Republic of Venice Wars involving Wallachia Wars involving the Holy Roman Empire Wars involving the Cossack Hetmanate Ottoman–Spanish conflicts