Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a

ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease

gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by

capital punishment, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of

dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherein a monarch's servants are killed in order for them to continue to serve their master in the next life. Closely related practices found in some

tribal societies are

cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

and

headhunting. Human sacrifice is also known as ritual murder.

Human sacrifice was practiced in many human societies beginning in prehistoric times. By the

Iron Age with the associated developments in religion (the

Axial Age), human sacrifice was becoming less common throughout

Africa,

Europe, and

Asia, and came to be looked down upon as

barbaric during

classical antiquity. In the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

, however, human sacrifice continued to be practiced, by some, to varying degrees until the

European colonization of the Americas. Today, human sacrifice has become extremely rare.

Modern secular laws treat human sacrifices as tantamount to

murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person wit ...

. Most major religions in the modern day condemn the practice. For example, the

Hebrew Bible prohibits murder and human sacrifice to

Moloch.

Evolution and context

Human sacrifice has been practiced on a number of different occasions and in many different cultures. The various rationales behind human sacrifice are the same that motivate religious sacrifice in general. Human sacrifice is typically intended to bring good fortune and to pacify the gods, for example in the context of the dedication of a completed building like a temple or bridge.

Fertility was another common theme in ancient religious sacrifices, such as sacrifices to the Aztec god of agriculture

Xipe Totec.

In ancient Japan, legends talk about ''

hitobashira'' ("human pillar"), in which maidens were

buried alive at the base of or near some constructions to protect the buildings against disasters or enemy attacks, and almost identical accounts appear in the

Balkans (

The Building of Skadar and

Bridge of Arta).

For the re-consecration of the

Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan

The (Spanish: Main Temple) was the main temple of the Mexica people in their capital city of Tenochtitlan, which is now Mexico City. Its architectural style belongs to the late Postclassic period of Mesoamerica. The temple was called ' in ...

in 1487, the

Aztecs

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those g ...

reported that they killed about 80,400 prisoners over the course of four days. According to

Ross Hassig, author of ''Aztec Warfare'', "between 10,000 and 80,400 persons" were sacrificed in the ceremony.

Human sacrifice can also have the intention of winning the gods' favor in warfare. In

Homeric legend,

Iphigeneia

In Greek mythology, Iphigenia (; grc, Ἰφιγένεια, , ) was a daughter of King Agamemnon and Queen Clytemnestra, and thus a princess of Mycenae.

In the story, Agamemnon offends the goddess Artemis on his way to the Trojan War by hunting ...

was to be sacrificed by her father

Agamemnon to appease

Artemis so she would allow the Greeks to wage the

Trojan War.

In some notions of an

afterlife

The afterlife (also referred to as life after death) is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's identity or their stream of consciousness continues to live after the death of their physical body. The surviving ess ...

, the deceased will benefit from victims killed at his funeral.

Mongols,

Scythians, early

Egyptians and various

Mesoamerican chiefs could take most of their household, including servants and

concubines, with them to the next world. This is sometimes called a "retainer sacrifice", as the leader's retainers would be sacrificed along with their master, so that they could continue to serve him in the afterlife.

Another purpose is

divination

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout histor ...

from the body parts of the victim. According to

Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

,

Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

s stabbed a victim with a sword and divined the future from his death spasms.

Headhunting is the practice of taking the head of a killed adversary, for ceremonial or magical purposes, or for reasons of prestige. It was found in many pre-modern

tribal societies.

Human sacrifice may be a ritual practiced in a stable society, and may even be conducive to enhancing societal unity (see:

Sociology of religion), both by creating a

bond unifying the sacrificing community, and by combining human sacrifice and

capital punishment, by removing individuals that have a negative effect on societal stability (criminals, religious heretics, foreign slaves or prisoners of war). However, outside of

civil religion

Civil religion, also referred to as a civic religion, is the implicit religious values of a nation, as expressed through public rituals, symbols (such as the national flag), and ceremonies on sacred days and at sacred places (such as monuments, bat ...

, human sacrifice may also result in outbursts of blood frenzy and

mass killings that destabilize society.

Many cultures show traces of prehistoric human sacrifice in their mythologies and religious texts, but ceased the practice before the onset of historical records. Some see the story of

Abraham and Isaac (

Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Bible

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of mankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Book of ...

22) as an example of an

etiological myth, explaining the abolition of human sacrifice. The Vedic ''

Purushamedha'' (literally "human sacrifice") is already a purely symbolic act in its earliest attestation. According to

Pliny the Elder, human sacrifice in

ancient Rome was abolished by a senatorial decree in 97 BCE, although by this time the practice had already become so rare that the decree was mostly a symbolic act. Human sacrifice once abolished is typically replaced by either animal sacrifice, or by the mock-sacrifice of

effigies, such as the

Argei

The rituals of the Argei were archaic religious observances in ancient Rome that took place on March 16 and March 17, and again on May 14 or May 15. By the time of Augustus, the meaning of these rituals had become obscure even to those who practi ...

in ancient Rome.

History by region

Ancient Near East

Successful agricultural cities had already emerged in the Near East by the

Neolithic, some protected behind stone walls.

Jericho

Jericho ( ; ar, أريحا ; he, יְרִיחוֹ ) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank. It is located in the Jordan Valley, with the Jordan River to the east and Jerusalem to the west. It is the administrative seat of the Jericho Gove ...

is the best known of these cities but other similar settlements existed along the coast of the

Levant extending north into

Asia Minor and west to the

Tigris and

Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

rivers. Most of the land was arid and the religious culture of the entire region centered on fertility and rain. Many of the religious rituals, including human sacrifice, had an agricultural focus. Blood was mixed with soil to improve its fertility.

Ancient Egypt

There may be evidence of retainer sacrifice in the

early dynastic period at

Abydos Abydos may refer to:

*Abydos, a progressive metal side project of German singer Andy Kuntz

* Abydos (Hellespont), an ancient city in Mysia, Asia Minor

* Abydos (''Stargate''), name of a fictional planet in the '' Stargate'' science fiction universe ...

, when on the death of a King he would be accompanied by servants, and possibly high officials, who would continue to serve him in eternal life. The skeletons that were found had no obvious signs of trauma, leading to speculation that the giving up of life to serve the King may have been a voluntary act, possibly carried out in a drug-induced state. At about 2800 BCE, any possible evidence of such practices disappeared, though echoes are perhaps to be seen in the burial of statues of servants in

Old Kingdom tombs.

Servants of both royalty and high court officials were slain to accompany their masters into the next world. The number of retainers buried surrounding the king's tomb was much greater than those of high court officials, however, again suggesting the greater importance of the pharaoh. For example,

King Djer had 318 retainer sacrifices buried in his tomb, and 269 retainer sacrifices buried in enclosures surrounding his tomb.

Biblical accounts

References in the

Bible point to an awareness of and disdain of human sacrifice in the history of

ancient Near Eastern practice. During a battle with the

Israelites, the King of

Moab

Moab ''Mōáb''; Assyrian: 𒈬𒀪𒁀𒀀𒀀 ''Mu'abâ'', 𒈠𒀪𒁀𒀀𒀀

''Ma'bâ'', 𒈠𒀪𒀊 ''Ma'ab''; Egyptian: 𓈗𓇋𓃀𓅱𓈉 ''Mū'ībū'', name=, group= () is the name of an ancient Levantine kingdom whose territo ...

gives his firstborn son and heir as a whole

burnt offering

A holocaust is a religious animal sacrifice that is completely consumed by fire. The word derives from the Ancient Greek ''holokaustos'' which is used solely for one of the major forms of sacrifice, also known as a burnt offering.

Etymology and ...

(''olah'', as used of the Temple sacrifice) (

2 Kings

The Book of Kings (, '' Sēfer Məlāḵīm'') is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Kings) in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. It concludes the Deuteronomistic history, a history of Israel also including the books ...

3:27). The Bible then recounts that, following the King's sacrifice, "There was great indignation

r wrath

R, or r, is the eighteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ar'' (pronounced ), plural ''ars'', or in Irelan ...

against Israel" and that the Israelites had to raise their siege of the Moabite capital and go away. This verse had perplexed many later Jewish and Christian commentators, who tried to explain what the impact of the Moabite King's sacrifice was, to make those under siege emboldened while disheartening the Israelites, make God angry at the Israelites or the Israelites fear his anger, make

Chemosh

Chemosh ( Moabite: 𐤊𐤌𐤔 ''Kamāš''; he, כְּמוֹשׁ ''Kəmōš'' ; Eblaite: 𒅗𒈪𒅖 ''Kamiš'', Akkadian: 𒅗𒄠𒈲 ''Kâmuš'') was the god of the Moabites. He is most notably attested in the Mesha Stele and the Hebrew ...

(the Moabite god) angry, or otherwise. Whatever the explanation, evidently at the time of writing, such an act of sacrificing the firstborn son and heir, while prohibited by Israelites (

Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy ( grc, Δευτερονόμιον, Deuteronómion, second law) is the fifth and last book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called (Hebrew: hbo, , Dəḇārīm, hewords Moses.html"_;"title="f_Moses">f_Moseslabel=none)_and_th ...

12:31; 18:9-12), was considered as an emergency measure in the Ancient Near East, to be performed in exceptional cases where divine favor was desperately needed.

The

binding of Isaac appears in the

Book of Genesis (22),

God tests

Abraham by asking him to present his son as a sacrifice on

Moriah

Moriah ( Hebrew: , ''Mōrīyya''; Arabic: ﻣﺮﻭﻩ, ''Marwah'') is the name given to a mountainous region in the Book of Genesis, where the binding of Isaac by Abraham is said to have taken place. Jews identify the region mentioned in Genes ...

. Abraham agrees to this command without arguing. The story ends with an

angel stopping Abraham at the last minute and providing a ram, caught in some nearby bushes, to be sacrificed instead. Many Bible scholars have suggested this story's origin was a remembrance of an era when human sacrifice was abolished in favour of animal sacrifice.

Another probable instance of human sacrifice mentioned in the Bible is

Jephthah

Jephthah (pronounced ; he, יִפְתָּח, ''Yīftāḥ''), appears in the Book of Judges as a judge who presided over Israel for a period of six years (). According to Judges, he lived in Gilead. His father's name is also given as Gilead, ...

's sacrifice of

his daughter in Judges 11. Jephthah vows to sacrifice to God whatever comes to greet him at the door when he returns home if he is victorious in his war against the

Ammonites. The vow is stated in the

Book of Judges 11:31: "Then whoever comes of the doors of my house to meet me, when I return victorious from the Ammonites, shall be the Lord's, to be offered up by me as a burnt offering (

NRSV)." When he returns from battle, his virgin daughter runs out to greet him, and Jephthah laments to her that he cannot take back his vow. She begs for, and is granted, "two months, so that I may go and wander on the mountains, and bewail my virginity, my companions and I", after which "

ephthahdid with her according to the vow he had made."

Two kings of

Judah,

Ahaz and

Manassah, sacrificed their sons. Ahaz, in 2 Kings 16:3, sacrificed his son. "... He even made his son pass through fire, according to the abominable practices of the nations whom the LORD drove out before the people of Israel (NRSV)." King Manasseh sacrificed his sons in

2 Chronicles

The Book of Chronicles ( he, דִּבְרֵי־הַיָּמִים ) is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Chronicles) in the Christian Old Testament. Chronicles is the final book of the Hebrew Bible, concluding the third sect ...

33:6. "He made his son pass through fire in the

valley of the son of Hinnom

The Valley of Hinnom ( he, , lit=Valley of the son of Hinnom, translit=Gēʾ ḇen-Hīnnōm) is a historic valley surrounding Ancient Jerusalem from the west and southwest. The valley is also known by the name Gehinnom ( ''Gēʾ-Hīnnōm'', ...

... He did much evil in the sight of the Lord, provoking him to anger (NRSV)." The valley symbolized hell in later religions, such as

Christianity, as a result.

Phoenicia

According to Roman and Greek sources,

Phoenicians and

Carthaginians sacrificed infants to their gods. The bones of numerous infants have been found in Carthaginian archaeological sites in modern times, but their cause of death remain controversial. In a single child cemetery called the "Tophet" by archaeologists, an estimated 20,000 urns were deposited.

Plutarch () mentions the practice, as do

Tertullian,

Orosius

Paulus Orosius (; born 375/385 – 420 AD), less often Paul Orosius in English, was a Roman priest, historian and theologian, and a student of Augustine of Hippo. It is possible that he was born in '' Bracara Augusta'' (now Braga, Portugal), t ...

,

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

and

Philo.

Livy and

Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

do not. The Bible asserts that children were sacrificed at a place called the

tophet ("roasting place") to the god

Moloch. According to Diodorus Siculus's ''

Bibliotheca historica

''Bibliotheca historica'' ( grc, Βιβλιοθήκη Ἱστορική, ) is a work of universal history by Diodorus Siculus. It consisted of forty books, which were divided into three sections. The first six books are geographical in theme, ...

'', "There was in their city a bronze image of

Cronus

In Ancient Greek religion and mythology, Cronus, Cronos, or Kronos ( or , from el, Κρόνος, ''Krónos'') was the leader and youngest of the first generation of Titans, the divine descendants of the primordial Gaia (Mother Earth) and ...

extending its hands, palms up and sloping toward the ground, so that each of the children when placed thereon rolled down and fell into a sort of gaping pit filled with fire."

Plutarch, however, claims that the children were already dead at the time, having been killed by their parents, whose consent – as well as that of the children – was required. Tertullian explains the acquiescence of the children as a product of their youthful trustfulness.

[

The accuracy of such stories is disputed by some modern historians and archaeologists.

]

Mesopotamia

Retainer sacrifice was practised within the royal tombs of ancient Mesopotamia. Courtiers, guards, musicians, handmaidens, and grooms were presumed to have committed ritual suicide by taking poison.

A 2009 examination of skulls from the royal cemetery at Ur, discovered in Iraq in the 1920s by a team led by C. Leonard Woolley

Sir Charles Leonard Woolley (17 April 1880 – 20 February 1960) was a British archaeologist best known for his excavations at Ur in Mesopotamia. He is recognized as one of the first "modern" archaeologists who excavated in a methodical way, k ...

, appears to support a more grisly interpretation of human sacrifices associated with elite burials in ancient Mesopotamia than had previously been recognized. Palace attendants, as part of royal mortuary ritual, were not dosed with poison to meet death serenely. Instead, they were put to death by having a sharp instrument, such as a pike, driven into their heads.

Europe

Neolithic Europe

There is archaeological evidence of human sacrifice in Neolithic to Eneolithic Europe.

Greco-Roman antiquity

The ancient ritual of expelling certain slaves, cripples, or criminals from a community to ward off disaster (known as

The ancient ritual of expelling certain slaves, cripples, or criminals from a community to ward off disaster (known as pharmakos

A pharmakós ( el, φαρμακός, plural ''pharmakoi'') in Ancient Greek religion was the ritualistic sacrifice or exile of a human scapegoat or victim.

Ritual

A slave, a cripple, or a criminal was chosen and expelled from the community at tim ...

), would at times involve publicly executing the chosen prisoner by throwing them off of a cliff.

References to human sacrifice can be found in Greek historical accounts as well as mythology. The human sacrifice in mythology, the '' deus ex machina'' salvation in some versions of Iphigeneia

In Greek mythology, Iphigenia (; grc, Ἰφιγένεια, , ) was a daughter of King Agamemnon and Queen Clytemnestra, and thus a princess of Mycenae.

In the story, Agamemnon offends the goddess Artemis on his way to the Trojan War by hunting ...

(who was about to be sacrificed by her father Agamemnon) and her replacement with a deer by the goddess Artemis, may be a vestigial memory of the abandonment and discrediting of the practice of human sacrifice among the Greeks in favour of animal sacrifice.

In ancient Rome, human sacrifice was infrequent but documented. Roman authors often contrast their own behavior with that of people who would commit the heinous act of human sacrifice, as human sacrifice was often looked down upon. These authors make it clear that such practices were from a much more uncivilized time in the past, far removed.Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus ( grc, Διονύσιος Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἁλικαρνασσεύς,

; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary sty ...

says that the ritual of the Argei

The rituals of the Argei were archaic religious observances in ancient Rome that took place on March 16 and March 17, and again on May 14 or May 15. By the time of Augustus, the meaning of these rituals had become obscure even to those who practi ...

, in which straw figures were tossed into the Tiber river, may have been a substitute for an original offering of elderly men. Cicero claimed that puppets thrown from the '' Pons Sublicius'' by the Vestal Virgins

In ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins or Vestals ( la, Vestālēs, singular ) were priestesses of Vesta, virgin goddess of Rome's sacred hearth and its flame.

The Vestals were unlike any other public priesthood. They were chosen before puberty ...

in a processional ceremony were substitutes for the past sacrifice of old men.

After the Roman defeat at Cannae, two Gauls and two Greeks in male-female couples were buried under the Forum Boarium, in a stone chamber used for the purpose at least once before. In Livy's description of these sacrifices, he distances the practice from Roman tradition and asserts that the past human sacrifices evident in the same location were "wholly alien to the Roman spirit." The rite was apparently repeated in 113 BCE, preparatory to an invasion of Gaul. They buried the two Greeks and the two Gauls alive as a plea to the gods to save Rome from destruction at the hands of Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Puni ...

.

According to Pliny the Elder, human sacrifice was banned by law during the consulship of Publius Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus in 97 BCE, although by this time it was so rare that the decree was largely symbolic. Sulla's ''Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficis

The ''Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficis'' (or veneficiis) (''The Cornelian Law against Murderers and Poisoners'') was a Roman statute enacted by Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 81 BC during his dictatorship to write laws and reconstitute the state ( ...

'' in 82 BC also included punishments for human sacrifice. The Romans also had traditions that centered around ritual murder, but which they did not consider to be sacrifice. Such practices included burying unchaste Vestal Virgins alive and drowning visibly intersex children. These were seen as reactions to extraordinary circumstances as opposed to being part of Roman tradition. Vestal Virgins who were accused of being unchaste were put to death, and a special chamber was built to bury them alive. This aim was to please the gods and restore balance to Rome.Gladiator

A gladiator ( la, gladiator, "swordsman", from , "sword") was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gla ...

combat was thought by the Romans to have originated as fights to the death among war captives at the funerals of Roman generals, and Christian polemicists, such as Tertullian, considered deaths in the arena

''In the Arena'' is an American one-hour show on CNN that premiered October 4, 2010 as ''Parker Spitzer'' and was hosted by former New York Democratic governor Eliot Spitzer and Pulitzer Prize-winning political columnist Kathleen Parker. It was b ...

to be little more than human sacrifice. Over time, participants became criminals and slaves, and their death was considered a sacrifice to the Manes on behalf of the dead.

Political rumors sometimes centered around sacrifice and in doing so, aimed to liken individuals to barbarians and show that the individual had become uncivilized. Human sacrifice also became a marker and defining characteristic of magic and bad religion.

Carthage

There is literary evidence for infant sacrifice being practiced in Carthage, however, current anthropological analyses have not found physical evidence to back up these claims. There is a Tophet, where infant remains have been found, but after current analytical techniques, it has been concluded this area is more representative of the naturally high infant mortality rate.

Celtic peoples

There is some evidence that ancient Celtic peoples practiced human sacrifice.Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

and Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

wrote that the Gauls burnt animal and human sacrifices in a large wickerwork figure, known as a wicker man, and said the human victims were usually criminals; while Posidonius wrote that druid

A druid was a member of the high-ranking class in ancient Celtic cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accounts. Whi ...

s who oversaw human sacrifices foretold the future by watching the death throes of the victims. Caesar also wrote that slaves of Gaulish chiefs would be burnt along with the body of their master as part of his funeral rites.Lucan

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (3 November 39 AD – 30 April 65 AD), better known in English as Lucan (), was a Roman poet, born in Corduba (modern-day Córdoba), in Hispania Baetica. He is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imperial ...

mentioned human sacrifices to the Gaulish gods Esus, Toutatis

Toutatis or Teutates is a Celtic god who was worshipped primarily in ancient Gaul and Britain. His name means "god of the tribe", and he has been widely interpreted as a tribal protector.Paul-Marie Duval (1993). ''Les dieux de la Gaule.'' Éditio ...

and Taranis

In Celtic mythology, Taranis (Proto-Celtic: *''Toranos'', earlier ''*Tonaros''; Latin: Taranus, earlier Tanarus) is the god of thunder, who was worshipped primarily in Gaul, Hispania, Britain, and Ireland, but also in the Rhineland and Danube reg ...

. In a 4th-century commentary on Lucan, an unnamed author added that sacrifices to Esus were hanged from a tree, those to Toutatis were drowned, and those to Taranis were burned

Burned or burnt may refer to:

* Anything which has undergone combustion

* Burned (image), quality of an image transformed with loss of detail in all portions lighter than some limit, and/or those darker than some limit

* ''Burnt'' (film), a 2015 ...

. According to the 2nd-century Roman writer Cassius Dio, Boudica

Boudica or Boudicca (, known in Latin chronicles as Boadicea or Boudicea, and in Welsh as ()), was a queen of the ancient British Iceni tribe, who led a failed uprising against the conquering forces of the Roman Empire in AD 60 or 61. She ...

's forces impaled Roman captives during her rebellion against the Roman occupation, to the accompaniment of revelry and sacrifices in the sacred groves of Andate. It is important to note, however, that the Romans benefited from making the Celts sound barbaric, and scholars are more skeptical about these accounts now than in the past.

There is some archaeological evidence of human sacrifice among Celtic peoples, although it is rare.Londinium

Londinium, also known as Roman London, was the capital of Roman Britain during most of the period of Roman rule. It was originally a settlement established on the current site of the City of London around AD 47–50. It sat at a key cross ...

's River Walbrook

The Walbrook is a subterranean river in the City of London that gave its name to the Walbrook City ward and a minor street in its vicinity.

The Walbrook is one of many "lost" rivers of London, the most famous of which is the River Fleet. It p ...

and the twelve headless corpses at the Gaulish sanctuary of Gournay-sur-Aronde

Gournay-sur-Aronde () is a commune in the Oise department in northern France.

Gournay-sur-Aronde is best known for a Late Iron Age sanctuary that dates back to the 4th century BCE, and was burned and levelled at the end of the 1st century BCE. I ...

.

Several ancient Irish bog bodies have been interpreted as kings who were ritually killed, presumably after serious crop failures or other disasters. Some were deposited in bogs on territorial boundaries (which were seen as liminal places) or near royal inauguration sites, and some were found to have eaten a ceremonial last meal. Some academics suggest there are allusions to kings being sacrificed in Irish mythology, particularly in tales of threefold deaths.Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick ( la, Patricius; ga, Pádraig ; cy, Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints be ...

. However, this account was written by Christian scribes centuries after the supposed events and may be based on biblical traditions about the god Moloch.

In Britain, the medieval legends of Dinas Emrys and of Saint Oran of Iona

Oran or Odran (Gaelic ''Oran''/''Odran''/''Odhrán'', the ''dh'' being silent; Latin ''Otteranus'', hence sometimes Otteran; died AD 548), by tradition a descendant of Conall Gulban, was a companion of Saint Columba in Iona, and the first C ...

mention foundation sacrifices, whereby people were ritually killed and buried under foundations

Foundation may refer to:

* Foundation (nonprofit), a type of charitable organization

** Foundation (United States law), a type of charitable organization in the U.S.

** Private foundation, a charitable organization that, while serving a good cause ...

to ensure the building's safety.

Baltic peoples

According to written sources from the 13th-14th centuries, the Lithuanians

Lithuanians ( lt, lietuviai) are a Baltic ethnic group. They are native to Lithuania, where they number around 2,378,118 people. Another million or two make up the Lithuanian diaspora, largely found in countries such as the United States, Uni ...

and Prussians made sacrifices to their pagan gods at their sacred places, alka hills, battlefields and near natural objects (sea

The sea, connected as the world ocean or simply the ocean, is the body of salty water that covers approximately 71% of the Earth's surface. The word sea is also used to denote second-order sections of the sea, such as the Mediterranean Sea, ...

, rivers, lakes, etc.).

Finnic peoples

Pope Gregory IX described in a papal letter how the Tavastians

Tavastians ( fi, Hämäläiset, sv, Tavaster, russian: Емь, Yem, Yam) are a historic people and a modern subgroup (heimo) of the Finnish people. They live in areas of the historical province of Tavastia (historical province), Tavastia (Häme) ...

in Finland sacrificed Christians to their pagan gods:

"The little children, to whom the light of Christ was revealed in baptism, they violently tore from this light and killed, and adult men, after pulling out their entrails, they sacrifice them to evil spirits and force others to run around trees until death, and some of the priests they blind, from others they brutally sever their hands and other limbs and wrap what is left behind in straws and burn them alive."

There have been found bog graves in Estonia that have been interpreted to have been part of human sacrifice. According to Aliis Moora, mostly enemy prisoners of war were sacrificed, the main reason indicated in the Livonian Chronicle as alleviating crop failure. Sacrifices were also performed as a show of gratitude after a victorious battle. Ritual cannibalism also took place, in order to gain the power of the enemy. The " Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum" by Adam of Bremen written at the end of the 11th century claims that behind the island of Kuramaa there is an island called Aestland (Estonia), whose inhabitants do not believe in the Christian God. Instead, they worship dragons and birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

(dracones adorant cum volucribus) to whom people bought from slavers are sacrificed. According to the Livonian Chronicle, describing the events after the Battle of Ümera

Battle of Ümera ( et, Ümera lahing) or Battle of Imera ( lv, Kauja pie Imeras), recorded by Henry of Latvia was fought south of Valmiera ( et, Volmari), near the Gauja River ( et, Ümera) in August or September 1210, during the Livonian Crusade ...

, "Estonians had seized some Germans, Livs, and Latvians, and some of them they simply killed, others they burned alive and tore the shirts off some of them, carved crosses on their backs with a sword and then beheaded". The Chronicle explicitly states they were sacrificed "to their gods" (diis suis).

Germanic peoples

Human sacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exi ...

was not particularly common among the Germanic peoples, being resorted to in exceptional situations arising from environmental crises (crop failure, drought, famine) or social crises (war), often thought to derive at least in part from the failure of the king to establish or maintain prosperity and peace () in the lands entrusted to him. In later Scandinavian practice, human sacrifice appears to have become more institutionalised and was repeated periodically as part of a larger sacrifice (according to Adam of Bremen, every nine years).Germanic pagans

Germanic may refer to:

* Germanic peoples, an ethno-linguistic group identified by their use of the Germanic languages

** List of ancient Germanic peoples and tribes

* Germanic languages

:* Proto-Germanic language, a reconstructed proto-language o ...

before the Viking Age depend on archaeology and on a few accounts in Greco-Roman ethnography. Roman writer Tacitus reported the Suebians

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own names ...

making human sacrifices to gods he interpreted as Mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

and Isis. He also claimed that Germans sacrificed Roman commanders and officers as a thanksgiving for victory in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. Jordanes reported the Goths sacrificing prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

to Mars, suspending the victims' severed arms from tree branches. Tacitus further refers to those who have transgressed certain societal rules being drowned and placed in wetlands

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in the soils. The ...

. This potentially explains finds of bog bodies dating to the Roman Iron Age although it is to be noted that none show signs of having died by drowning.Norse people

The Norsemen (or Norse people) were a North Germanic peoples, North Germanic ethnolinguistic group of the Early Middle Ages, during which they spoke the Old Norse language. The language belongs to the North Germanic languages, North Germanic br ...

. One account by Ahmad ibn Fadlan in 922 claims Varangian warriors were sometimes buried with enslaved women, in the belief they would become their wives in Valhalla. He describes the funeral of a Varangian chieftain, in which a slave girl volunteered to be buried with him. After ten days of festivities, she was given an intoxicating drink, stabbed to death by a priestess, and burnt together with the dead chieftain in his boat (see ship burial). This practice is evidenced archaeologically, with many male warrior burials (such as the ship burial at Balladoole on the Isle of Man, or that at Oseberg in Norway) also containing female remains with signs of trauma.

According to Adémar de Chabannes, just before his death in 932 or 933, Rollo (founder and first ruler of the Viking Duchy of Normandy) performed human sacrifices to appease the pagan gods while at the same time giving gifts to the churches in Normandy.

In the 11th century, Adam of Bremen wrote that human and animal sacrifices were made at the Temple at Gamla Uppsala in Sweden. He wrote that every ninth year, nine men and nine of every animal were sacrificed and their bodies hung in a sacred grove.

The ''

According to Adémar de Chabannes, just before his death in 932 or 933, Rollo (founder and first ruler of the Viking Duchy of Normandy) performed human sacrifices to appease the pagan gods while at the same time giving gifts to the churches in Normandy.

In the 11th century, Adam of Bremen wrote that human and animal sacrifices were made at the Temple at Gamla Uppsala in Sweden. He wrote that every ninth year, nine men and nine of every animal were sacrificed and their bodies hung in a sacred grove.

The ''Historia Norwegiæ

''Historia Norwegiæ'' is a short history of Norway written in Latin by an anonymous monk. The only extant manuscript is in the private possession of the Earl of Dalhousie, and is now kept in the National Records of Scotland in Edinburgh. The manu ...

'' and '' Ynglinga saga'' refer to the willing sacrifice of King Dómaldi

Domalde, ''Dómaldi'' or ''Dómaldr'' (Old Norse possibly "Power to Judge"McKinnell (2005:70).) was a legendary Swedish king of the House of Ynglings, cursed by his stepmother, according to Snorri Sturluson, with ''ósgæssa'', "ill-luck". He w ...

after bad harvests. The same saga also relates that Dómaldi's descendant king Aun

Aun the Old (Old Norse ''Aunn inn gamli'', Latinized ''Auchun'', Proto-Norse ''*Audawiniʀ'': English: "Edwin the Old") is a mythical Swedish king of the House of Yngling in the ''Heimskringla''.

Aun was the son of Jorund, and had ten sons, nin ...

sacrificed nine of his own sons to Odin

Odin (; from non, Óðinn, ) is a widely revered Æsir, god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, v ...

in exchange for longer life, until the Swedes stopped him from sacrificing his last son, Egil.

In the '' Saga of Hervor and Heidrek'', Heidrek agrees to the sacrifice of his son in exchange for command over half the army of Reidgotaland

Reidgotaland, Reidgothland, Reidgotland, Hreidgotaland or Hreiðgotaland was a land mentioned in Germanic heroic legend (mentioned in the Scandinavian sagas as well as the Anglo-Saxon Widsith) usually interpreted as the land of the Goths.

Etymol ...

. With this, he seizes the whole kingdom and prevents the sacrifice of his son, dedicating those fallen in his rebellion to Odin instead.

Slavic peoples

In the 10th century, Persian explorer Ahmad ibn Rustah described funerary rites for the Rus' (Scandinavian Norsemen traders in northeastern Europe) including the sacrifice of a young female slave.Sviatoslav

Sviatoslav (russian: Святосла́в, Svjatosláv, ; uk, Святосла́в, Svjatosláv, ) is a Russian and Ukrainian given name of Slavic origin. Cognates include Svetoslav, Svatoslav, , Svetislav. It has a Pre-Christian pagan charact ...

during the Russo-Byzantine War "in accordance with their ancestral custom."

According to the 12th-century Primary Chronicle

The ''Tale of Bygone Years'' ( orv, Повѣсть времѧньныхъ лѣтъ, translit=Pověstĭ vremęnĭnyxŭ lětŭ; ; ; ; ), often known in English as the ''Rus' Primary Chronicle'', the ''Russian Primary Chronicle'', or simply the ...

, prisoners of war were sacrificed to the supreme Slavic deity Perun. Sacrifices to pagan gods, along with paganism itself, were banned after the Christianization of Rus'

Christianization (American and British English spelling differences#-ise.2C -ize .28-isation.2C -ization.29, or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of ...

by Grand Prince Vladimir the Great in the 980s.

Archeological findings indicate that the practice may have been widespread, at least among slaves, judging from mass graves containing the cremated fragments of a number of different people.

East Asia

China

The history of human sacrifice in China may extend as early as 2300 BCE.

The history of human sacrifice in China may extend as early as 2300 BCE.[ Forensic analysis indicates the victims were all teenage girls.][

The ancient Chinese are known to have made drowned sacrifices of men and women to the river god ]Hebo

Hebo () is the god of the Yellow River (''Huang He''). The Yellow River is the main river of northern China, one of the world's major rivers and a river of great cultural importance in China. This is reflected in Chinese mythology by the tales su ...

. They also have buried slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

alive with their owners upon death as part of a funeral

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect th ...

service. This was especially prevalent during the Shang

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Chinese royal dynasty founded by Tang of Shang (Cheng Tang) that ruled in the Yellow River valley in the second millennium BC, traditionally succeeding the Xia dynasty and f ...

and Zhou dynasties. During the Warring States period, Ximen Bao

Ximen Bao was a Chinese hydraulic engineer, philosopher, and politician. He was a government minister and court advisor to Marquis Wen of Wei (reigned 445–396 BC) during the Warring States period of ancient China. He was known as an early ratio ...

of Wei

Wei or WEI may refer to:

States

* Wey (state) (衛, 1040–209 BC), Wei in pinyin, but spelled Wey to distinguish from the bigger Wei of the Warring States

* Wei (state) (魏, 403–225 BC), one of the seven major states of the Warring States per ...

outlawed human sacrificial practices to the river god. In Chinese lore, Ximen Bao is regarded as a folk hero who pointed out the absurdity of human sacrifice.

The sacrifice of a high-ranking male's slaves, concubines, or servants upon his death (called ''Xun Zang'' 殉葬 or ''Sheng Xun'' 生殉) was a more common form. The stated purpose was to provide companionship for the dead in the afterlife. In earlier times, the victims were either killed or buried alive, while later they were usually forced to commit suicide.

Funeral human sacrifice was widely practiced in the ancient Chinese state of Qin

Qin () was an ancient Chinese state during the Zhou dynasty. Traditionally dated to 897 BC, it took its origin in a reconquest of western lands previously lost to the Rong; its position at the western edge of Chinese civilization permitted ex ...

. According to the '' Records of the Grand Historian'' by Han dynasty historian Sima Qian

Sima Qian (; ; ) was a Chinese historian of the early Han dynasty (206AD220). He is considered the father of Chinese historiography for his ''Records of the Grand Historian'', a general history of China covering more than two thousand years b ...

, the practice was started by Duke Wu, the tenth ruler of Qin, who had 66 people buried with him in 678 BCE. The 14th ruler Duke Mu had 177 people buried with him in 621 BCE, including three senior government officials.[

][

]

Afterwards, the people of Qin wrote the famous poem ''Yellow Bird'' to condemn this barbaric practice, later compiled in the Confucian '' Classic of Poetry''.

The tomb of the 18th ruler Duke Jing of Qin

Duke Jing of Qin (, died 537 BC) was from 576 to 537 BC the eighteenth ruler of the Zhou Dynasty state of Qin that eventually united China to become the Qin Dynasty. His ancestral name was Ying ( 嬴), and Duke Jing was his posthumous title. D ...

, who died in 537 BCE, has been excavated. More than 180 coffins containing the remains of 186 victims were found in the tomb.

The practice would continue until Duke Xian of Qin (424–362 BCE) abolished it in 384 BCE. Modern historian Ma Feibai considers the significance of Duke Xian's abolition of human sacrifice in Chinese history comparable to that of Abraham Lincoln's abolition of slavery in American history.Hongwu Emperor

The Hongwu Emperor (21 October 1328 – 24 June 1398), personal name Zhu Yuanzhang (), courtesy name Guorui (), was the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty of China, reigning from 1368 to 1398.

As famine, plagues and peasant revolts in ...

of the Ming dynasty revived it in 1395, following the Mongolian Yuan precedent, when his second son died and two of the prince's concubines were sacrificed. In 1464, the Tianshun Emperor, in his will, forbade the practice for Ming emperors and princes.

Human sacrifice was also practised by the Manchus. Following Nurhaci's death, his wife, Lady Abahai, and his two lesser consorts committed suicide. During the Qing dynasty, sacrifice of slaves was banned by the Kangxi Emperor in 1673.

Japan

In the practice known as Hitobashira (人柱, "human pillar"), a person was buried alive at the base of large structures such as dams, castles, and bridges.

Tibet

Human sacrifice was practiced in Tibet prior to the arrival of Buddhism in the 7th century.

Historical practices such as burying bodies under the cornerstones of houses may have been practiced during the medieval era, but few concrete instances have been recorded or verified.[ This replacement of human victims with effigies is attributed to Padmasambhava, a Tibetan saint of the mid-8th century, in Tibetan tradition.

Nevertheless, there is some evidence that outside of orthodox Buddhism, there were practices of tantric human sacrifice which survived throughout the medieval period, and possibly into modern times.][ The 15th century Blue Annals reports that in the 13th century so-called "18 robber-monks" slaughtered men and women in their ceremonies. Grunfeld (1996) concludes that it cannot be ruled out that isolated instances of human sacrifice did survive in remote areas of Tibet until the mid-20th century, but they must have been rare.][ Grunfeld also notes that Tibetan practices unrelated to human sacrifice, such as the use of human bone in ritual instruments, have been depicted without evidence as products of human sacrifice.][

]

Indian subcontinent

In India, human sacrifice is mainly known as ''Narabali''. Here "nara" means human and "bali" means sacrifice. It takes place in some parts of India mostly to find lost treasure. In

In India, human sacrifice is mainly known as ''Narabali''. Here "nara" means human and "bali" means sacrifice. It takes place in some parts of India mostly to find lost treasure. In Maharashtra

Maharashtra (; , abbr. MH or Maha) is a states and union territories of India, state in the western India, western peninsular region of India occupying a substantial portion of the Deccan Plateau. Maharashtra is the List of states and union te ...

, the government made it illegal to practice with the Anti-Superstition and Black Magic Act

The Maharashtra Prevention and Eradication of Human Sacrifice and other Inhuman, Evil and Aghori Practices and Black Magic Act, 2013 is a criminal law act for the state of Maharashtra, India, originally drafted by anti-superstition activist and ...

. Currently human sacrifice is very rare in modern India. There have been at least three cases through 2003–2013 where men have been murdered allegedly in the name of human sacrifice.

Thuggee

Thuggee (, ) are actions and crimes carried out by Thugs, historically, organised gangs of professional robbers and murderers in India. The English word ''thug'' traces its roots to the Hindi ठग (), which means 'swindler' or 'deceiver'. Rela ...

s, or thugs, were an organized gang of professional robbers

Robbery is the crime of taking or attempting to take anything of value by force, threat of force, or by use of fear. According to common law, robbery is defined as taking the property of another, with the intent to permanently deprive the perso ...

and murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person wit ...

ers who traveled in groups across the Indian subcontinent for several hundred years. They were first mentioned in Ẓiyā'-ud-Dīn Baranī's ( en, History of Fīrūz Shāh) dated around 1356.Henry Colebrooke

Henry Thomas Colebrooke FRS FRSE (15 June 1765 – 10 March 1837) was an English orientalist and mathematician. He has been described as "the first great Sanskrit scholar in Europe".

Biography

Henry Thomas Colebrooke was born on 15 Jun ...

, was that human sacrifice did not actually take place. Those verses which referred to '' purushamedha'' were meant to be read symbolically,Rajendralal Mitra

Raja Rajendralal Mitra (16 February 1822 – 26 July 1891) was among the first Indian cultural researchers and historians writing in English. A polymath and the first Indian president of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, he was a pioneering figur ...

published a defence of the thesis that human sacrifice, as had been practised in Bengal, was a continuation of traditions dating back to Vedic periods.Chandogya Upanishad

The ''Chandogya Upanishad'' (Sanskrit: , IAST: ''Chāndogyopaniṣad'') is a Sanskrit text embedded in the Chandogya Brahmana of the Sama Veda of Hinduism.Patrick Olivelle (2014), ''The Early Upanishads'', Oxford University Press; , pp. 166-16 ...

(3.17.4) includes ahimsa in its list of virtues.Hatimura Temple

The Hatimura Temple is a Hindu temple (Shakti Pitha), located at Hatimura Post office Jakhalabandha, Nagaon district of Assam, India. It was built during the reign of Ahom king Pramatta Singha in 1667 '' Sakabda'' (1745-46 AD). It used to be a ...

, a Shakti (Great Goddess) temple located at Silghat

Silghat is a town located on the southern banks of the Brahmaputra, in Nagaon district in the Indian state of Assam. It is 48 km northeast of Nagaon. With a river and hills, the scenic beauty of Silghat attracts local and visitors throughou ...

, in the Nagaon district of Assam. It was built during the reign of king Pramatta Singha

Sunenphaa () also, Pramatta Singha, was the king of Ahom Kingdom. He succeeded his elder brother Swargadeo Siva Singha, as the king of Ahom Kingdom. His reign of seven years was peaceful and prosperous. He constructed numerous buildings and te ...

in 1667 '' Sakabda'' (1745–1746 CE). It used to be an important center of Shaktism in ancient Assam. Its presiding goddess is Durga in her aspect of ''Mahisamardini

Durga ( sa, दुर्गा, ) is a major Hindu goddess, worshipped as a principal aspect of the mother goddess Mahadevi. She is associated with protection, strength, motherhood, destruction, and wars.

Durga's legend centres around co ...

'', slayer of the demon Mahisasura. It was also performed in the Tamresari Temple

Tamreswari temple (also Dikkaravasini, Kesai Khati) is situated about 18 km away from Sadiya in Tinsukia district, Assam, India. The temple was in the custody of non-Brahmin tribal priests called Deoris. Some remains suggest that a Chut ...

which was located in Sadiya under the Chutia kings.

Open human sacrifices were carried out in connection with the worship of Shakti until approximately the early modern period, and in Bengal perhaps as late as the early 19th century.Hindu culture

Hinduism () is an Indian religions, Indian religion or ''dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the Major religious groups, world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion ...

certain Tantric cults performed human sacrifice until around the same time, both actual and symbolic; it was a highly ritualised act, and on occasion took many months to complete.Bengal Sati Regulation, 1829

The Bengal Sati Regulation, or Regulation XVII, in India under East India Company rule, by the Governor-General Lord William Bentinck, which made the practice of sati or suttee illegal in all jurisdictions of India and subject to prosecu ...

, later across India, the last explicit legislation, in India, being the Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987

Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 is a law enacted by Government of Rajasthan in 1987. It became an Act of the Parliament of India with the enactment of The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 in 1988. The Act seeks to prevent ''sati'', the volu ...

.

Pacific

In Ancient Hawaii, a luakini temple, or luakini heiau, was a Native Hawaiian sacred place where human and animal blood sacrifices were offered. '' Kauwa'', the outcast or slave class, were often used as human sacrifices at the ''luakini heiau''. They are believed to have been war captives, or the descendants of war captives. They were not the only sacrifices; law-breakers of all castes or defeated political opponents were also acceptable as victims. Rituals for the Hawaiian god Kūkaʻilimoku included human sacrifice, which was not part of the worship of other gods.

According to an 1817 account, in Tonga, a child was strangled to assist the recovery of a sick relation.

The people of Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

practised widow-strangling. When Fijians adopted Christianity, widow-strangling was abandoned.

Pre-Columbian Americas

Some of the most famous forms of ancient human sacrifice were performed by various Pre-Columbian civilizations in the

Some of the most famous forms of ancient human sacrifice were performed by various Pre-Columbian civilizations in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

that included the sacrifice of prisoners as well as voluntary sacrifice. Friar Marcos de Niza (1539), writing of the Chichimecas, said that from time to time "they of this valley cast lots whose luck (honour) it shall be to be sacrificed, and they make him great cheer, on whom the lot falls, and with great joy they lund him with flowers upon a bed prepared in the said ditch all full of flowers and sweet herbs, on which they lay him along, and lay great store of dry wood on both sides of him, and set it on fire on either part, and so he dies" and "that the victim took great pleasure" in being sacrificed.

North America

The Mixtec players of the Mesoamerican ballgame were sacrificed when the game was used to resolve a dispute between cities. The rulers would play a game instead of going to battle. The losing ruler would be sacrificed. The ruler "Eight Deer", who was considered a great ball player and who won several cities this way, was eventually sacrificed, because he attempted to go beyond lineage-governing practices, and to create an empire.

=Maya

=

The Maya held the belief that cenotes or limestone sinkholes were portals to the underworld and sacrificed human beings and tossed them down the cenote to please the water god Chaac

Chaac (also spelled Chac or, in Classic Mayan, Chaahk ) is the name of the Maya god of rain, thunder, and lighting. With his lightning axe, Chaac strikes the clouds, causing them to produce thunder and rain. Chaac corresponds to Tlaloc among ...

. The most notable example of this is the "Sacred Cenote

The Sacred Cenote ( es, cenote sagrado, , "sacred well"; alternatively known as the "Well of Sacrifice") is a water-filled sinkhole in limestone at the pre-Columbian Maya archaeological site of Chichen Itza, in the northern Yucatán Peninsula. It ...

" at Chichén Itzá.[ Extensive excavations have recovered the remains of 42 individuals, half of them under twenty years old.

Only in the ]Post-Classic

Mesoamerican chronology divides the history of prehispanic Mesoamerica into several periods: the Paleo-Indian (first human habitation until 3500 BCE); the Archaic (before 2600 BCE), the Preclassic or Formative (2500 BCE – ...

era did this practice become as frequent as in central Mexico. In the Post-Classic period, the victims and the altar are represented as daubed in a hue now known as Maya blue, obtained from the añil

''Indigofera suffruticosa'', commonly known as Guatemalan indigo, small-leaved indigo (Sierra Leone), West Indian indigo, wild indigo, and anil, is a flowering plant in the pea family, Fabaceae.

''Anil'' is native to the subtropical and tropic ...

plant and the clay mineral palygorskite.[ cited in ]

=Aztecs

=

The Aztecs were particularly noted for practicing human sacrifice on a large scale; an offering to Huitzilopochtli would be made to restore the blood he lost, as the sun was engaged in a daily battle. Human sacrifices would prevent the end of the world that could happen on each cycle of 52 years. In the 1487 re-consecration of the

The Aztecs were particularly noted for practicing human sacrifice on a large scale; an offering to Huitzilopochtli would be made to restore the blood he lost, as the sun was engaged in a daily battle. Human sacrifices would prevent the end of the world that could happen on each cycle of 52 years. In the 1487 re-consecration of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan

The (Spanish: Main Temple) was the main temple of the Mexica people in their capital city of Tenochtitlan, which is now Mexico City. Its architectural style belongs to the late Postclassic period of Mesoamerica. The temple was called ' in ...

some estimate that 80,400 prisoners were sacrificed though numbers are difficult to quantify, as all obtainable Aztec texts were destroyed by Christian missionaries during the period 1528–1548.[ and that on cautious reckoning, based on reliable evidence, the numbers could not have exceeded at most several hundred per year in Tenochtitlan.][ The real number of sacrificed victims during the 1487 consecration is unknown.

] Michael Harner, in his 1997 article ''The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice'', estimates the number of persons sacrificed in central Mexico in the 15th century as high as 250,000 per year.

Michael Harner, in his 1997 article ''The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice'', estimates the number of persons sacrificed in central Mexico in the 15th century as high as 250,000 per year. Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl

Fernando is a Spanish and Portuguese given name and a surname common in Spain, Portugal, Italy, France, Switzerland, former Spanish or Portuguese colonies in Latin America, Africa, the Philippines, India, and Sri Lanka. It is equivalent to the G ...

, a Mexica descendant and the author of ''Codex Ixtlilxochitl

Aztec codices ( nah, Mēxihcatl āmoxtli , sing. ''codex'') are Mesoamerican manuscripts made by the pre-Columbian Aztec, and their Nahuatl-speaking descendants during the colonial period in Mexico.

History

Before the start of the Sp ...

'', claimed that one in five children of the Mexica subjects was killed annually. Victor Davis Hanson argues that an estimate by Carlos Zumárraga of 20,000 per annum is more plausible. Other scholars believe that, since the Aztecs always tried to intimidate their enemies, it is far more likely that they inflated the official number as a propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

tool.

=United States and Canada

=

The peoples of the Southeastern United States known as the

The peoples of the Southeastern United States known as the Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

(800 to 1600 CE) have been suggested to have practiced human sacrifice, because some artifacts have been interpreted as depicting such acts. Mound 72 at Cahokia (the largest Mississippian site), located near modern St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

, was found to have numerous pits filled with mass burials thought to have been retainer sacrifices. One of several similar pit burials had the remains of 53 young women who had been strangled and neatly arranged in two layers. Another pit held 39 men, women, and children who showed signs of dying a violent death before being unceremoniously dumped into the pit. Several bodies showed signs of not having been fully dead when buried and of having tried to claw their way to the surface. On top of these people another group had been neatly arranged on litters made of cedar poles and cane matting. Another group of four individuals found in the mound were interred on a low platform, with their arms interlocked. They had had their heads and hands removed. The most spectacular burial at the mound is the "Birdman burial

Mound 72 is a small ridgetop mound located roughly to the south of Monks Mound at Cahokia Mounds near Collinsville, Illinois. Early in the site's history, the location began as a circle of 48 large wooden posts known as a "woodhenge". The woodhen ...

". This was the burial of a tall man in his 40s, now thought to have been an important early Cahokian ruler. He was buried on an elevated platform covered by a bed of more than 20,000 marine-shell disc beads arranged in the shape of a falcon, with the bird's head appearing beneath and beside the man's head, and its wings and tail beneath his arms and legs. Below the birdman was another man, buried facing downward. Surrounding the birdman were several other retainers and groups of elaborate grave goods.Tattooed Serpent

Tattooed Serpent (died 1725) (Natchez: Obalalkabiche; French: Serpent Piqué) was the war chief of the Natchez people of Grand Village, which was located near Natchez in what is now the U.S. state of Mississippi. He and his brother, the paramoun ...

" in 1725, the war chief and younger brother of the "Great Sun" or Chief of the Natchez; two of his wives, one of his sisters (nicknamed ''La Glorieuse'' by the French), his first warrior, his doctor, his head servant and the servant's wife, his nurse, and a craftsman of war clubs all chose to die and be interred with him, as well as several old women and an infant who was strangled by his parents.[

The Pawnee practiced an annual ]Morning Star Ceremony

Pawnee mythology is the body of oral history, cosmology, and myths of the Pawnee people concerning their gods and heroes. The Pawnee are a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans, originally located o ...

, which included the sacrifice of a young girl. Though the ritual continued, the sacrifice was discontinued in the 19th century.

South America

The Incas practiced human sacrifice, especially at great festivals or royal funerals where retainers died to accompany the dead into the next life. The Moche sacrificed teenagers en masse, as archaeologist Steve Bourget found when he uncovered the bones of 42 male adolescents in 1995.

The Incas practiced human sacrifice, especially at great festivals or royal funerals where retainers died to accompany the dead into the next life. The Moche sacrificed teenagers en masse, as archaeologist Steve Bourget found when he uncovered the bones of 42 male adolescents in 1995.Sapa Inca

The Sapa Inca (from Quechua ''Sapa Inka'' "the only Inca") was the monarch of the Inca Empire (''Tawantinsuyu''), as well as ruler of the earlier Kingdom of Cusco and the later Neo-Inca State. While the origins of the position are mythical and o ...

(emperor) or during a famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, Demographic trap, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. Th ...

.[

]

Africa

West Africa

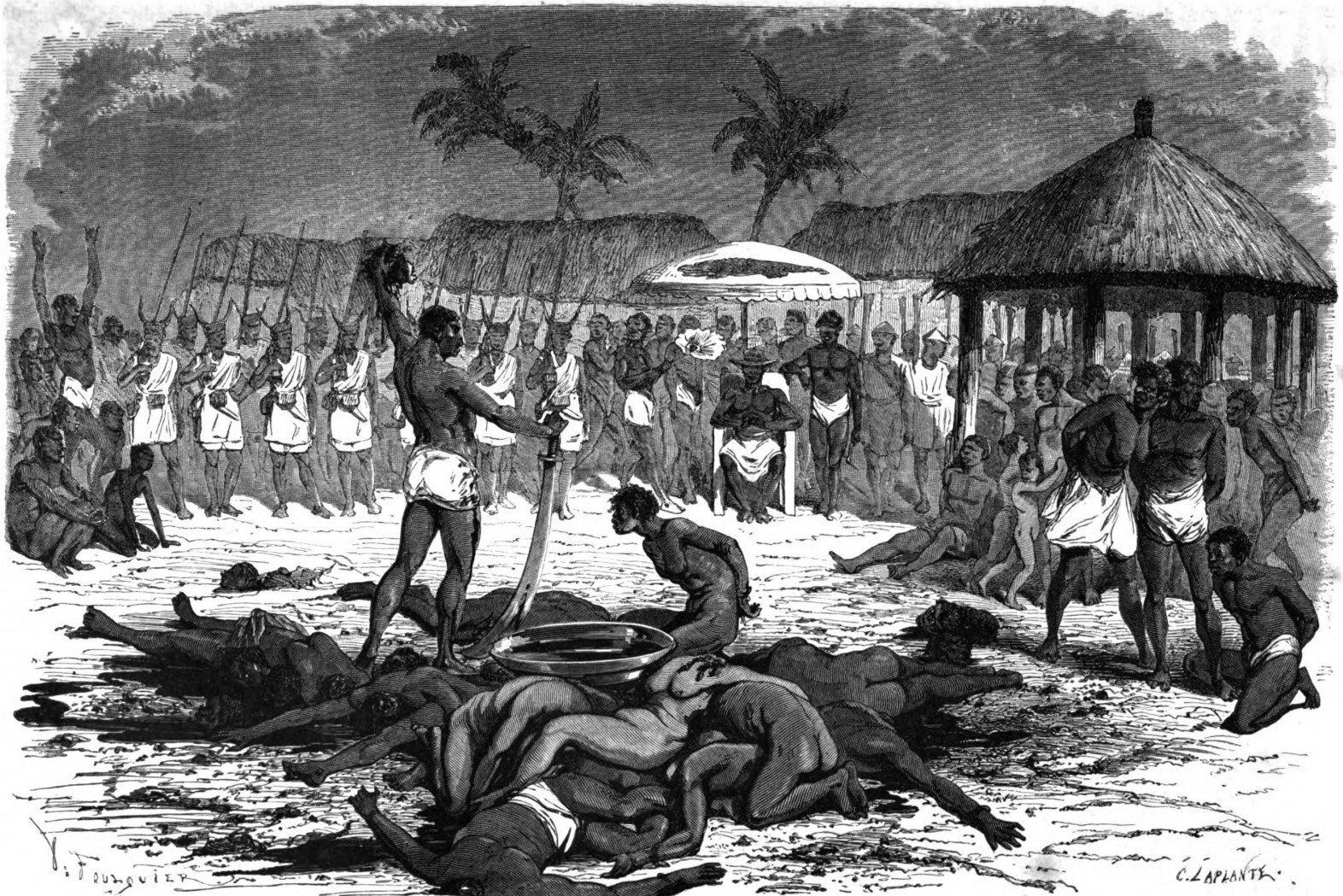

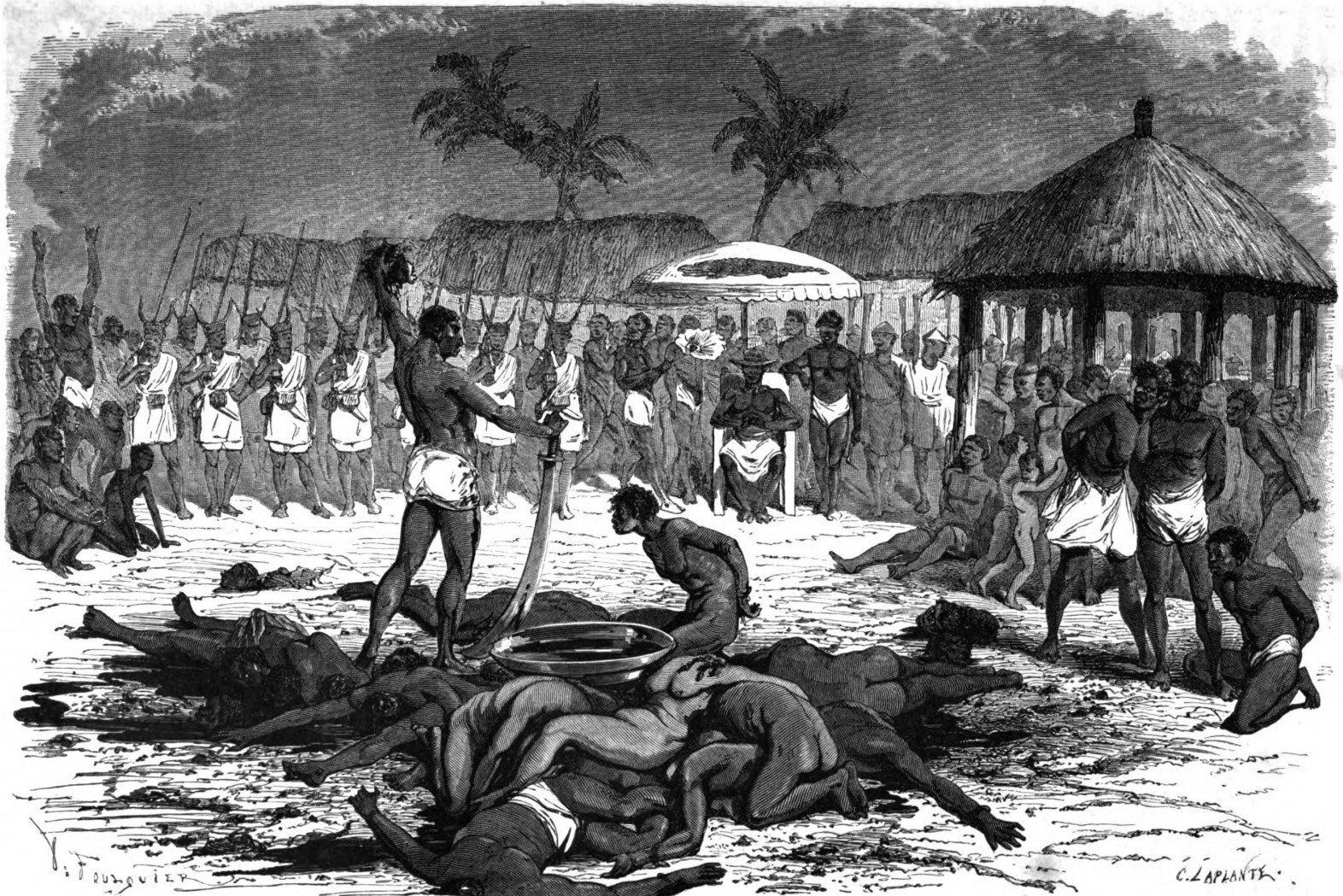

JuJu Human sacrifice is still practiced in West Africa. The Annual customs of Dahomey was the most notorious example, but sacrifices were carried out all along the West African coast and further inland. Sacrifices were particularly common after the death of a king or queen, and there are many recorded cases of hundreds or even thousands of slaves being sacrificed at such events. Sacrifices were particularly common in

JuJu Human sacrifice is still practiced in West Africa. The Annual customs of Dahomey was the most notorious example, but sacrifices were carried out all along the West African coast and further inland. Sacrifices were particularly common after the death of a king or queen, and there are many recorded cases of hundreds or even thousands of slaves being sacrificed at such events. Sacrifices were particularly common in Dahomey

The Kingdom of Dahomey () was a West African kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. Dahomey developed on the Abomey Plateau amongst the Fon people in the early 17th century and became a region ...

, in what is now Benin, and in the small independent states in what is now southern Nigeria. According to Rudolph Rummel

Rudolph Joseph Rummel (October 21, 1932 – March 2, 2014) was an American political scientist and professor at the Indiana University, Yale University, and University of Hawaiʻi. He spent his career studying data on collective violence and war w ...

, "Just consider the Grand Custom in Dahomey: When a ruler died, hundreds, sometimes even thousands, of prisoners would be slain. In one of these ceremonies in 1727, as many as 4,000 were reported killed. In addition, Dahomey had an Annual Custom during which 500 prisoners were sacrificed."

In the Ashanti Region of modern-day Ghana, human sacrifice was often combined with capital punishment.

The ''Leopard men

The Leopard Society (not to be confused with Ekpe), was a secret society that originated in Sierra Leone.#refBeatty1915, Beatty, p.3 It was believed that members of the society could transform into leopards through the use of witchcraft. The ear ...

'' were a West African secret society active into the mid-1900s that practised cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

. It was believed that the ritual cannibalism would strengthen both members of the society and their entire tribe. In Tanganyika

Tanganyika may refer to:

Places

* Tanganyika Territory (1916–1961), a former British territory which preceded the sovereign state

* Tanganyika (1961–1964), a sovereign state, comprising the mainland part of present-day Tanzania

* Tanzania Main ...

, the ''Lion men'' committed an estimated 200 murders in a single three-month period.

Canary Islands

It has been reported from Spanish chronicles that the Guanches (ancient inhabitants of these islands) performed both animal and human sacrifices.[ These children were brought from various parts of the island for the purpose of sacrifice. Likewise, when an aboriginal king died his subjects should also assume the sea, along with the embalmers who embalmed the Guanche mummies.

In Gran Canaria, bones of children were found mixed with those of lambs and goat kids and on Tenerife, amphorae have been found with the remains of children inside. This suggests a different kind of ritual infanticide from those who were thrown off the cliffs.][

]

Prohibition in major religions

Greek polytheism

In Greek polytheism, Tantalus was condemned to Tartarus for eternity for the human sacrifice of his son Pelops.

Abrahamic religions

Many traditions of Abrahamic religions such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

consider that God commanded Abraham to sacrifice his son to examine obedience of Abraham to His commands. To prove his obedience, Abraham intended to sacrifice his son. However at the eleventh hour God commanded Abraham to sacrifice a ram instead of his son.

Judaism

Judaism explicitly forbids human sacrifice, regarding it as murder. Jews view the ''Akedah

The Binding of Isaac ( he, , ), or simply "The Binding" (, ), is a story from Genesis 22 of the Hebrew Bible. In the biblical narrative, God tells Abraham to sacrifice his son, Isaac, on Moriah. As Abraham begins to comply, having bound Is ...

'' as central to the abolition of human sacrifice. Some Talmudic scholars assert that its replacement is the sacrificial offering of animals at the Temple – using Exodus 13:2–12ff; 22:28ff; 34:19ff; Numeri 3:1ff; 18:15; Deuteronomy 15:19 – others view that as being superseded by the symbolic '' pars-pro-toto'' sacrifice of the covenant of circumcision. Leviticus 20:2 and Deuteronomy 18:10 specifically outlaw the giving of children to Moloch, making it punishable by stoning; the Tanakh subsequently denounces human sacrifice as barbaric customs of Moloch worshippers (e.g. Psalms 106:37ff).

Judges chapter 11 features a Judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as a part of a panel of judges. A judge hears all the witnesses and any other evidence presented by the barristers or solicitors of the case, assesses the credibility an ...

named Jephthah

Jephthah (pronounced ; he, יִפְתָּח, ''Yīftāḥ''), appears in the Book of Judges as a judge who presided over Israel for a period of six years (). According to Judges, he lived in Gilead. His father's name is also given as Gilead, ...

vowing that "whatsoever cometh forth from the doors of my house to meet me shall surely be the Lord's, and I will offer it up as a burnt-offering" in gratitude for God's help with a military battle against the Ammonites.Radak ''Cervera Bible'', David Qimhi's Grammar Treatise

David Kimhi ( he, ר׳ דָּוִד קִמְחִי, also Kimchi or Qimḥi) (1160–1235), also known by the Hebrew acronym as the RaDaK () (Rabbi David Kimhi), was a medieval rabbi, biblical commen ...

) to suggest that she was not actually killed."Radak ''Cervera Bible'', David Qimhi's Grammar Treatise

David Kimhi ( he, ר׳ דָּוִד קִמְחִי, also Kimchi or Qimḥi) (1160–1235), also known by the Hebrew acronym as the RaDaK () (Rabbi David Kimhi), was a medieval rabbi, biblical commen ...

, Book of Judges 11:39; ''Metzudas Dovid'' ibid Allegations accusing Jews of committing ritual murder – called the "

Allegations accusing Jews of committing ritual murder – called the "blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mur ...

" – were widespread during the Middle Ages, often leading to the slaughter of entire Jewish communities.

Christianity

Christianity developed the belief that the story of Isaac's binding was a foreshadowing of the sacrifice of Christ, whose death and resurrection are believed to have enabled the salvation and atonement for man from its sins, including original sin

Original sin is the Christian doctrine that holds that humans, through the fact of birth, inherit a tainted nature in need of regeneration and a proclivity to sinful conduct. The biblical basis for the belief is generally found in Genesis 3 (t ...

. There is a tradition that the site of Isaac's binding, Moriah

Moriah ( Hebrew: , ''Mōrīyya''; Arabic: ﻣﺮﻭﻩ, ''Marwah'') is the name given to a mountainous region in the Book of Genesis, where the binding of Isaac by Abraham is said to have taken place. Jews identify the region mentioned in Genes ...

, later became Jerusalem, the city of Jesus's future crucifixion. The beliefs of most Christian denominations hinge upon the substitutionary atonement

Substitutionary atonement, also called vicarious atonement, is a central concept within Christian theology which asserts that Jesus died "for us", as propagated by the Western classic and objective paradigms of atonement in Christianity, which ...

of the sacrifice of God the Son, which was necessary for salvation in the afterlife. According to Christian doctrine, each individual person on earth must participate in, and / or receive the benefits of, this divine human sacrifice for the atonement of their sins. Early Christian sources explicitly described this event as a sacrificial offering, with Christ in the role of both priest and human sacrifice, although starting with the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, some writers, such as John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

, have disputed the model of Jesus' death as a propitiatory sacrifice.

Although early Christians in the Roman Empire were accused of being cannibals, ''theophages'' (Greek for "god eaters") practices such as human sacrifice were abhorrent to them. Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Christians believe that this "pure sacrifice" as Christ's self-giving in love is made present in the sacrament

A sacrament is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments ...

of the Eucharist