Dwale (anaesthetic) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Attempts at producing a state of general anesthesia can be traced throughout recorded history in the writings of the ancient

The Sumerians are said to have cultivated and harvested the

The Sumerians are said to have cultivated and harvested the

Bian Que (

Bian Que (

Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) was an English polymath who discovered nitrous oxide,

Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) was an English polymath who discovered nitrous oxide,

Friedrich Sertürner (1783–1841) first isolated morphine from

Friedrich Sertürner (1783–1841) first isolated morphine from

The 20th century saw the transformation of the practices of tracheotomy, endoscopy and non-surgical tracheal intubation from rarely employed procedures to essential components of the practices of anesthesia,

The 20th century saw the transformation of the practices of tracheotomy, endoscopy and non-surgical tracheal intubation from rarely employed procedures to essential components of the practices of anesthesia,

Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of c ...

ians, Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

ns, Assyrians, Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

, Indians

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

, and Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

.

The Renaissance saw significant advances in anatomy and surgical technique

Surgery ''cheirourgikē'' (composed of χείρ, "hand", and ἔργον, "work"), via la, chirurgiae, meaning "hand work". is a medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a person to investigate or treat a pat ...

. However, despite all this progress, surgery remained a treatment of last resort. Largely because of the associated pain

Pain is a distressing feeling often caused by intense or damaging stimuli. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, ...

, many patients with surgical disorders chose certain death rather than undergo surgery. Although there has been a great deal of debate as to who deserves the most credit for the discovery of general anesthesia, it is generally agreed that certain scientific discoveries in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were critical to the eventual introduction and development of modern anesthetic techniques.

Two major advances occurred in the late 19th century, which together allowed the transition to modern surgery. An appreciation of the germ theory of disease led rapidly to the development and application of antiseptic techniques in surgery. Antisepsis, which soon gave way to asepsis, reduced the overall morbidity and mortality

Mortality is the state of being mortal, or susceptible to death; the opposite of immortality.

Mortality may also refer to:

* Fish mortality, a parameter used in fisheries population dynamics to account for the loss of fish in a fish stock throug ...

of surgery to a far more acceptable rate than in previous eras. Concurrent with these developments were the significant advances in pharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemica ...

and physiology which led to the development of general anesthesia and the control of pain.

In the 20th century, the safety and efficacy of general anesthesia was improved by the routine use of tracheal intubation and other advanced airway management

Airway management includes a set of maneuvers and medical procedures performed to prevent and relieve airway obstruction. This ensures an open pathway for gas exchange between a patient's lungs and the atmosphere. This is accomplished by either cl ...

techniques. Significant advances in monitoring and new anesthetic agents

Anesthesia is a state of controlled, temporary loss of sensation or awareness that is induced for medical or veterinary purposes. It may include some or all of analgesia (relief from or prevention of pain), paralysis (muscle relaxation), am ...

with improved pharmacokinetic

Pharmacokinetics (from Ancient Greek ''pharmakon'' "drug" and ''kinetikos'' "moving, putting in motion"; see chemical kinetics), sometimes abbreviated as PK, is a branch of pharmacology dedicated to determining the fate of substances administered ...

and pharmacodynamic

Pharmacodynamics (PD) is the study of the biochemical and physiologic effects of drugs (especially pharmaceutical drugs). The effects can include those manifested within animals (including humans), microorganisms, or combinations of organisms (for ...

characteristics also contributed to this trend. Standardized training programs for anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetist

A nurse anesthetist is an advanced practice nurse who administers anesthesia for surgery or other medical procedures. They are involved in the administration of anesthesia in a majority of countries, with varying levels of autonomy.

A survey pu ...

s emerged during this period. The increased application of economic and business administration principles to health care in the late 20th and early 21st centuries led to the introduction of management practices such as transfer pricing to improve the efficiency of anesthetists.

Etymology of "anesthesia"

The word "anesthesia", coined by Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809–1894) in 1846 from the Greek , ''an-'', "without"; and , ''aisthēsis'', "sensation", refers to the inhibition of sensation.Antiquity

The first attempts at general anesthesia were probably herbal remedies administered in prehistory.Alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

is the oldest known sedative

A sedative or tranquilliser is a substance that induces sedation by reducing irritability or excitement. They are CNS depressants and interact with brain activity causing its deceleration. Various kinds of sedatives can be distinguished, but t ...

; it was used in ancient Mesopotamia thousands of years ago.

Opium

The Sumerians are said to have cultivated and harvested the

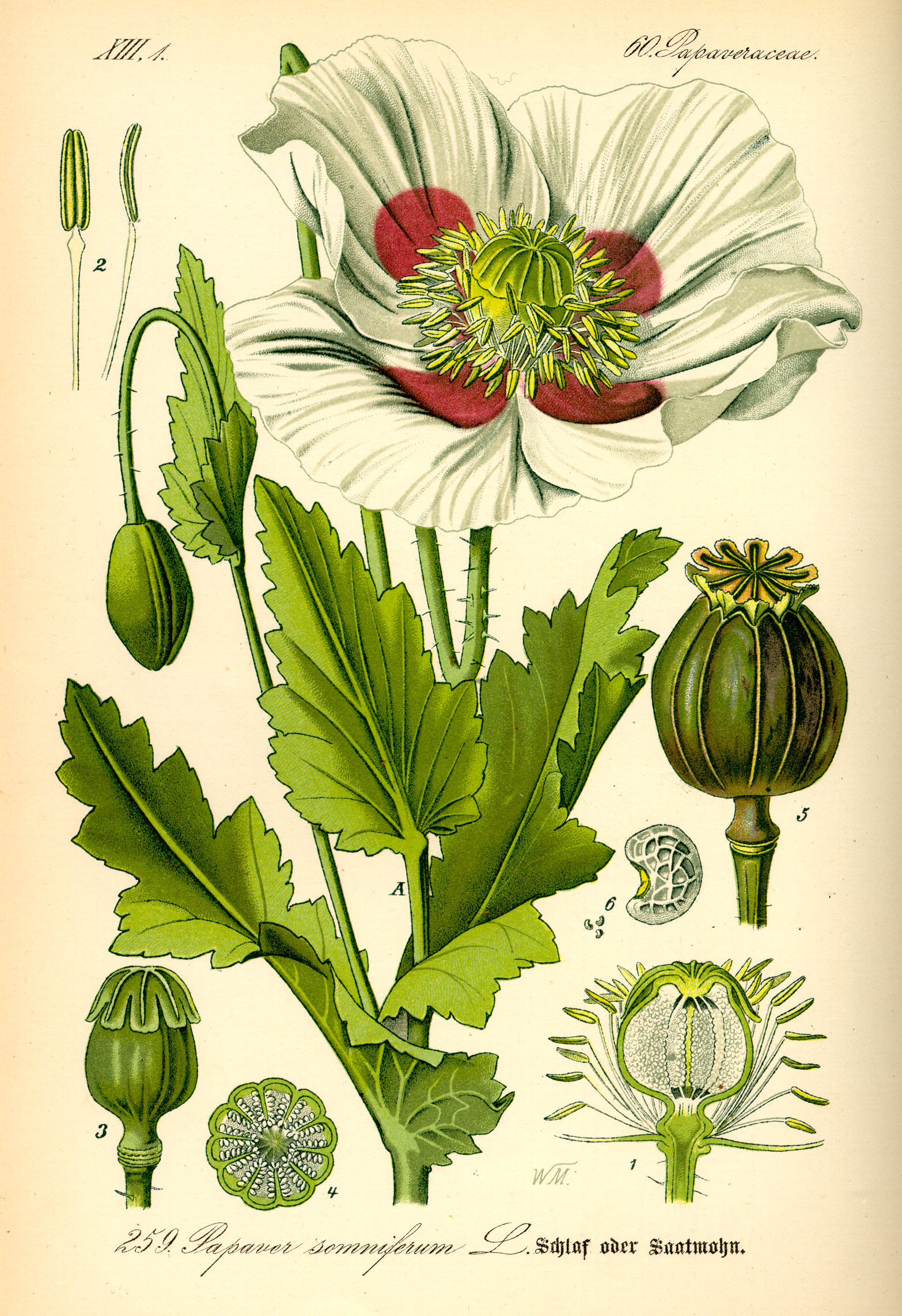

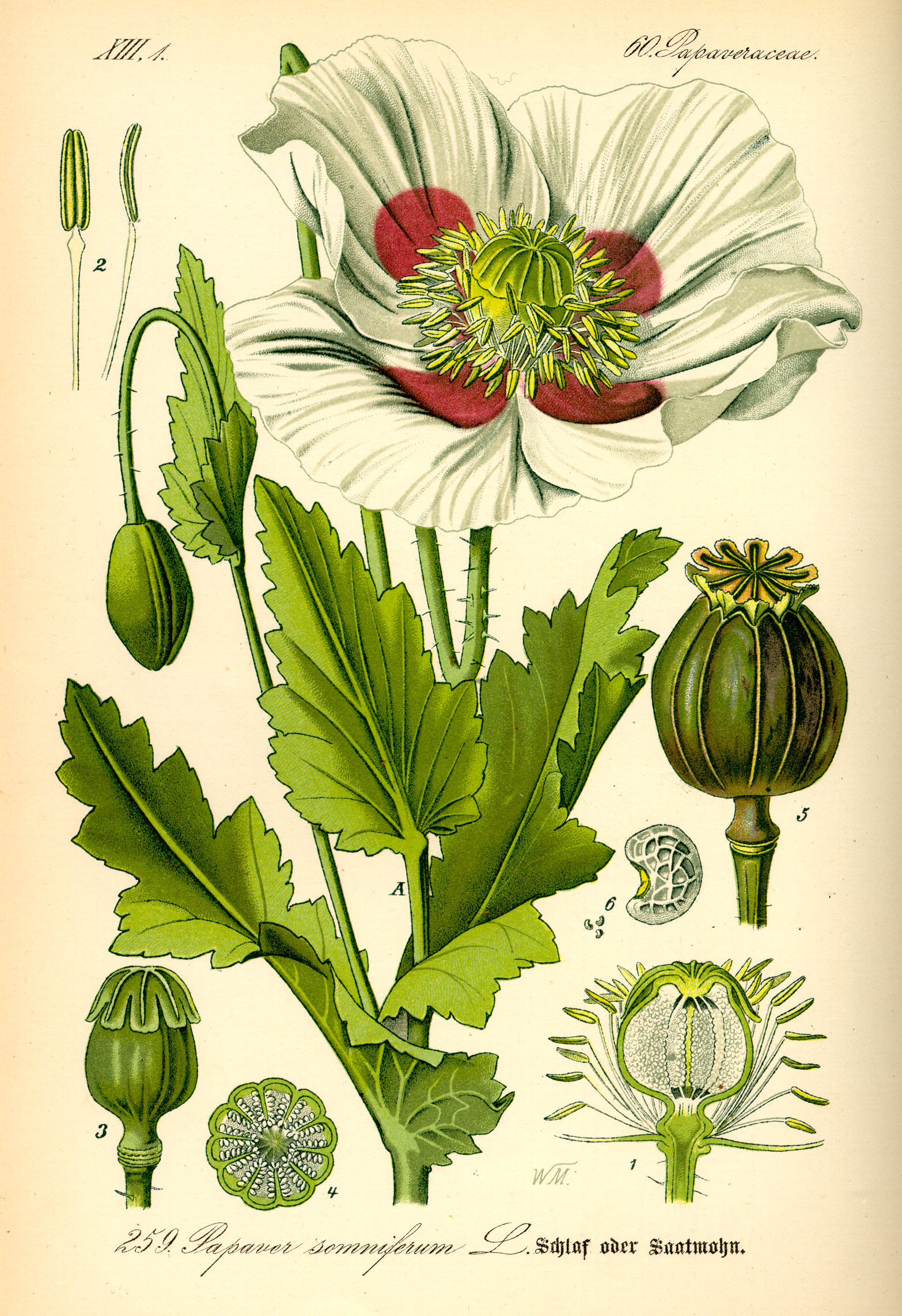

The Sumerians are said to have cultivated and harvested the opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

poppy ('' Papaver somniferum'') in lower Mesopotamia as early as 3400 BC, though this has been disputed. The most ancient testimony concerning the opium poppy found to date was inscribed in cuneiform script

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-sha ...

on a small white clay tablet at the end of the third millennium BC. This tablet was discovered in 1954 during excavations at Nippur

Nippur (Sumerian language, Sumerian: ''Nibru'', often logogram, logographically recorded as , EN.LÍLKI, "Enlil City;"The Cambridge Ancient History: Prolegomena & Prehistory': Vol. 1, Part 1. Accessed 15 Dec 2010. Akkadian language, Akkadian: '' ...

, and is currently kept at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Deciphered by Samuel Noah Kramer

Samuel Noah Kramer (September 28, 1897 – November 26, 1990) was one of the world's leading Assyriologists, an expert in Sumerian history and Sumerian language. After high school, he attended Temple University, before Dropsie and Penn, both in ...

and Martin Leve, it is considered to be the most ancient pharmacopoeia in existence. Some Sumerian tablets of this era have an ideogram inscribed upon them, "hul gil", which translates to "plant of joy", believed by some authors to refer to opium. The term ''gil'' is still used for opium in certain parts of the world. The Sumerian goddess Nidaba is often depicted with poppies growing out of her shoulders. About 2225 BC, the Sumerian territory became a part of the Babylonian empire. Knowledge and use of the opium poppy and its euphoric effects thus passed to the Babylonians, who expanded their empire eastwards to Persia and westwards to Egypt, thereby extending its range to these civilizations. British archaeologist and cuneiformist Reginald Campbell Thompson writes that opium was known to the Assyrians in the 7th century BC. The term "Arat Pa Pa" occurs in the ''Assyrian Herbal'', a collection of inscribed Assyrian tablets dated to c. 650 BC. According to Thompson, this term is the Assyrian name for the juice of the poppy and it may be the etymological origin of the Latin "'' papaver''".

The ancient Egyptians had some surgical instruments, as well as crude analgesics and sedatives, including possibly an extract prepared from the mandrake fruit. The use of preparations similar to opium in surgery is recorded in the Ebers Papyrus, an Egyptian medical papyrus written in the Eighteenth dynasty. However, it is questionable whether opium itself was known in ancient Egypt. The Greek gods Hypnos (Sleep), Nyx

Nyx (; , , "Night") is the Greek goddess and personification of night. A shadowy figure, Nyx stood at or near the beginning of creation and mothered other personified deities, such as Hypnos (Sleep) and Thanatos (Death), with Erebus (Darknes ...

(Night), and Thanatos (Death) were often depicted holding poppies.

Prior to the introduction of opium to ancient India and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, these civilizations pioneered the use of cannabis incense and aconitum

''Aconitum'' (), also known as aconite, monkshood, wolf's-bane, leopard's bane, mousebane, women's bane, devil's helmet, queen of poisons, or blue rocket, is a genus of over 250 species of flowering plants belonging to the family Ranunculaceae. ...

. c. 400 BC, the Sushruta Samhita

The ''Sushruta Samhita'' (सुश्रुतसंहिता, IAST: ''Suśrutasaṃhitā'', literally "Suśruta's Compendium") is an ancient Sanskrit text on medicine and surgery, and one of the most important such treatises on this subj ...

(a text from the Indian subcontinent on ayurvedic medicine

Ayurveda () is an alternative medicine system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent. The theory and practice of Ayurveda is pseudoscientific. Ayurveda is heavily practiced in India and Nepal, where around 80% of the population repor ...

and surgery) advocates the use of wine with incense of cannabis for anesthesia. By the 8th century AD, Arab traders had brought opium to India and China.

Classical antiquity

In Classical antiquity, anaesthetics were described by: * Dioscorides ('' De Materia Medica'') * Galen * Hippocrates * Theophrastus (''Historia Plantarum

Historia may refer to:

* Historia, the local version of the History channel in Spain and Portugal

* Historia (TV channel), a Canadian French language specialty channel

* Historia (newspaper), a French monthly newspaper devoted to History topics

* ...

'')

China and Hua Tuo's Ancient Chemical Mixture

Bian Que (

Bian Que (Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

: 扁鵲, Wade–Giles: ''Pien Ch'iao'', ) was a legendary Chinese internist and surgeon who reportedly used general anesthesia for surgical procedures. It is recorded in the '' Book of Master Han Fei'' (), the '' Records of the Grand Historian'' (), and the '' Book of Master Lie'' () that Bian Que gave two men, named "Lu" and "Chao", a toxic drink which rendered them unconscious for three days, during which time he performed a gastrostomy

Gastrostomy is the creation of an artificial external opening into the stomach for nutritional support or gastric decompression.

Typically this would include an incision in the patient's epigastrium as part of a formal operation. It can be perfor ...

upon them.

Hua Tuo (Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

:華佗, ) was a Chinese surgeon

In modern medicine, a surgeon is a medical professional who performs surgery. Although there are different traditions in different times and places, a modern surgeon usually is also a licensed physician or received the same medical training as ...

of the 2nd century AD. According to the '' Records of Three Kingdoms'' () and the ''Book of the Later Han

The ''Book of the Later Han'', also known as the ''History of the Later Han'' and by its Chinese name ''Hou Hanshu'' (), is one of the Twenty-Four Histories and covers the history of the Han dynasty from 6 to 189 CE, a period known as the Later ...

'' (), Hua Tuo performed surgery under general anesthesia using a formula he had developed by mixing wine with a mixture of herbal extract

An extract is a substance made by extracting a part of a raw material, often by using a solvent such as ethanol, oil or water. Extracts may be sold as tinctures, absolutes or in powder form.

The aromatic principles of many spices, nuts, h ...

s he called '' mafeisan'' (麻沸散). Hua Tuo reportedly used mafeisan to perform even major operations such as resection of gangrenous

Gangrene is a type of tissue death caused by a lack of blood supply. Symptoms may include a change in skin color to red or black, numbness, swelling, pain, skin breakdown, and coolness. The feet and hands are most commonly affected. If the ga ...

intestines. Before the surgery, he administered an oral anesthetic potion, probably dissolved in wine, in order to induce a state of unconsciousness and partial neuromuscular blockade

Neuromuscular-blocking drugs block neuromuscular transmission at the neuromuscular junction, causing paralysis of the affected skeletal muscles. This is accomplished via their action on the post-synaptic acetylcholine (Nm) receptors.

In clin ...

.

The exact composition of mafeisan, similar to all of Hua Tuo's clinical knowledge, was lost when he burned his manuscripts, just before his death. The composition of the anesthetic powder was not mentioned in either the ''Records of Three Kingdoms'' or the ''Book of the Later Han''. Because Confucian teachings regarded the body as sacred and surgery was considered a form of body mutilation, surgery was strongly discouraged in ancient China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapte ...

. Because of this, despite Hua Tuo's reported success with general anesthesia, the practice of surgery in ancient China ended with his death.

The name ''mafeisan'' combines ''ma'' ( 麻, meaning "cannabis, hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants o ...

, numbed or tingling

Paresthesia is an abnormal sensation of the skin (tingling, pricking, chilling, burning, numbness) with no apparent physical cause. Paresthesia may be transient or chronic, and may have any of dozens of possible underlying causes. Paresthesias ar ...

"), ''fei'' ( 沸, meaning "boiling

Boiling is the rapid vaporization of a liquid, which occurs when a liquid is heated to its boiling point, the temperature at which the vapour pressure of the liquid is equal to the pressure exerted on the liquid by the surrounding atmosphere. Th ...

or bubbling"), and ''san'' ( 散, meaning "to break up or scatter", or "medicine in powder form"). Therefore, the word ''mafeisan'' probably means something like "cannabis boil powder". Many sinologists and scholars of traditional Chinese medicine have guessed at the composition of Hua Tuo's mafeisan powder, but the exact components still remain unclear. His formula is believed to have contained some combination of:

* ''bai zhi'' (''Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

:白芷'',''Angelica dahurica

''Angelica dahurica'', commonly known as Dahurian angelica, is a wildly grown species of angelica native to Siberia, Russia Far East, Mongolia, Northeastern China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. This species tend to grow near river banks, along str ...

''),

* ''cao wu'' (''Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

:草烏'', ''Aconitum kusnezoffii

''Aconitum'' (), also known as aconite, monkshood, wolf's-bane, leopard's bane, mousebane, women's bane, devil's helmet, queen of poisons, or blue rocket, is a genus of over 250 species of flowering plants belonging to the family Ranunculaceae. ...

'', ''Aconitum kusnezoffii

''Aconitum'' (), also known as aconite, monkshood, wolf's-bane, leopard's bane, mousebane, women's bane, devil's helmet, queen of poisons, or blue rocket, is a genus of over 250 species of flowering plants belonging to the family Ranunculaceae. ...

'', Kusnezoff's monkshood, or wolfsbane root),

* ''chuān xiōng'' (''Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

:川芎,Ligusticum wallichii

''Ligusticum striatum'' (syn. ''L. wallichii'') is a flowering plant native to India, Kashmir, and Nepal in the carrot family best known for its use in traditional Chinese medicine where it is considered one of the 50 fundamental herbs. It is k ...

'', or Szechuan lovage),

* ''dong quai'' (''Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

:当归'', '' Angelica sinensis'', or "female ginseng"),

* ''wu tou'' (烏頭, '' Aconitum carmichaelii'', rhizome of ''Aconitum'', or "Chinese monkshood"),

* ''yang jin hua'' (洋金花, '' Flos Daturae metelis'', or '' Datura stramonium'', jimson weed, devil's trumpet, thorn apple, locoweed, moonflower),

* ''ya pu lu'' (押不芦,'' Mandragora officinarum'')

* rhododendron

''Rhododendron'' (; from Ancient Greek ''rhódon'' "rose" and ''déndron'' "tree") is a very large genus of about 1,024 species of woody plants in the heath family (Ericaceae). They can be either evergreen or deciduous. Most species are nati ...

flower, and

* jasmine

Jasmine ( taxonomic name: ''Jasminum''; , ) is a genus of shrubs and vines in the olive family (Oleaceae). It contains around 200 species native to tropical and warm temperate regions of Eurasia, Africa, and Oceania. Jasmines are widely cultiva ...

root.

Others have suggested the potion may have also contained hashish

Hashish ( ar, حشيش, ()), also known as hash, "dry herb, hay" is a drug made by compressing and processing parts of the cannabis plant, typically focusing on flowering buds (female flowers) containing the most trichomes. European Monitorin ...

, bhang, ''shang-luh'', or opium. Victor H. Mair

Victor Henry Mair (; born March 25, 1943) is an American sinologist. He is a professor of Chinese at the University of Pennsylvania. Among other accomplishments, Mair has edited the standard '' Columbia History of Chinese Literature'' and the ''C ...

wrote that ''mafei'' "appears to be a transcription of some Indo-European word related to "morphine"." Some authors believe that Hua Tuo may have discovered surgical analgesia by acupuncture, and that mafeisan either had nothing to do with or was simply an adjunct to his strategy for anesthesia. Many physicians have attempted to re-create the same formulation based on historical records but none have achieved the same clinical efficacy as Hua Tuo's. In any event, Hua Tuo's formula did not appear to be effective for major operations.

Other substances used from antiquity for anesthetic purposes include extracts of juniper

Junipers are coniferous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Juniperus'' () of the cypress family Cupressaceae. Depending on the taxonomy, between 50 and 67 species of junipers are widely distributed throughout the Northern Hemisphere, from the Arcti ...

and coca.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

Ferdowsi

Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi ( fa, ; 940 – 1019/1025 CE), also Firdawsi or Ferdowsi (), was a Persians, Persian poet and the author of ''Shahnameh'' ("Book of Kings"), which is one of the world's longest epic poetry, epic poems created by a sin ...

(940–1020) was a Persian poet who lived in the Abbasid Caliphate. In '' Shahnameh'', his national epic

A national epic is an epic poem or a literary work of epic scope which seeks or is believed to capture and express the essence or spirit of a particular nation—not necessarily a nation state, but at least an ethnic or linguistic group with as ...

poem, Ferdowsi described a caesarean section

Caesarean section, also known as C-section or caesarean delivery, is the surgical procedure by which one or more babies are delivered through an incision in the mother's abdomen, often performed because vaginal delivery would put the baby or mo ...

performed on Rudaba

Rudāba or Rudābeh ( fa, رودابه ) is a Persian mythological female figure in Ferdowsi's epic Shahnameh. She is the princess of Kabul, daughter of Mehrab Kaboli and Sindukht, and later she becomes married to Zal, as they become lovers. The ...

. A special wine prepared by a Zoroastrian priest was used as an anesthetic for this operation.

c. 1020, Ibn Sīnā (980–1037) in '' The Canon of Medicine'' described the "soporific sponge", a sponge imbued with aromatics and narcotic

The term narcotic (, from ancient Greek ναρκῶ ''narkō'', "to make numb") originally referred medically to any psychoactive compound with numbing or paralyzing properties. In the United States, it has since become associated with opiates ...

s, which was to be placed under a patient's nose during surgical operations. Opium made its way from Asia Minor to all parts of Europe between the 10th and 13th centuries.

Throughout 1200–1500 AD in England, a potion called dwale was used as an anesthetic. This alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

-based mixture contained bile

Bile (from Latin ''bilis''), or gall, is a dark-green-to-yellowish-brown fluid produced by the liver of most vertebrates that aids the digestion of lipids in the small intestine. In humans, bile is produced continuously by the liver (liver bile ...

, opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

, lettuce, bryony

''Bryonia'' is a genus of flowering plants in the gourd family. Bryony is its best-known common name. They are native to western Eurasia and adjacent regions, such as North Africa, the Canary Islands and South Asia.

Description and ecology

B ...

, henbane, hemlock and vinegar. Surgeons roused them by rubbing vinegar and salt on their cheekbones. One can find records of dwale in numerous literary sources, including Shakespeare's

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

'' Hamlet'', and the John Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculo ...

poem " Ode to a Nightingale". In the 13th century, we have the first prescription of the "spongia soporifica"—a sponge soaked in the juices of unripe mulberry, flax, mandragora leaves, ivy, lettuce seeds, lapathum, and hemlock with hyoscyamus. After treatment and/or storage, the sponge could be heated and the vapors inhaled with anesthetic effect.

Alchemist

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscience, protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in Chinese alchemy, C ...

Ramon Llull

Ramon Llull (; c. 1232 – c. 1315/16) was a philosopher, theologian, poet, missionary, and Christian apologist from the Kingdom of Majorca.

He invented a philosophical system known as the ''Art'', conceived as a type of universal logic to pro ...

has been credited with discovering diethyl ether in 1275. Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (1493–1541), better known as Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

He w ...

, discovered the analgesic

An analgesic drug, also called simply an analgesic (American English), analgaesic (British English), pain reliever, or painkiller, is any member of the group of drugs used to achieve relief from pain (that is, analgesia or pain management). It ...

properties of diethyl ether around 1525. It was first synthesized in 1540 by Valerius Cordus, who noted some of its medicinal properties. He called it ''oleum dulce vitrioli'', a name that reflects the fact that it is synthesized by distilling a mixture of ethanol and sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular formu ...

(known at that time as oil of vitriol). August Sigmund Frobenius August Sigmund Frobenius (earliest date mentioned 1727, died 1741), FRS, also known as Sigismond Augustus Frobenius, Joannes Sigismundus Augustus Frobenius, and Johann Sigismund August Froben, was a German-born chemist in the 18th century who is kn ...

gave the name ''Spiritus Vini Æthereus'' to the substance in 1730.

18th century

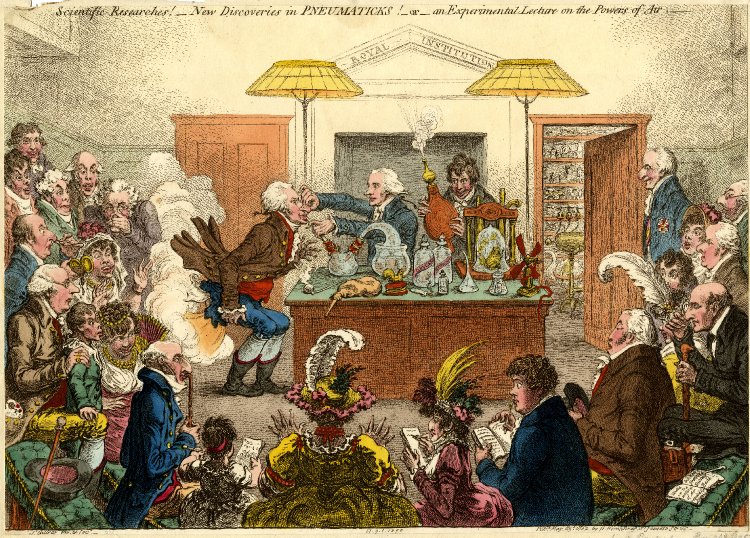

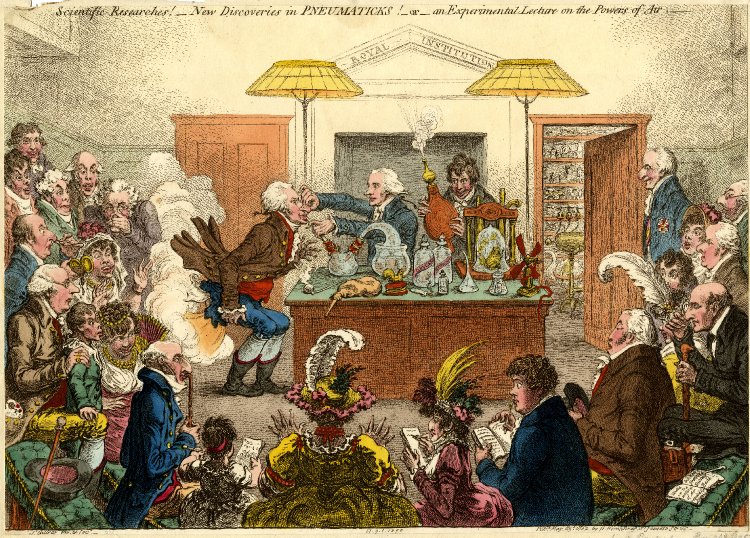

Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) was an English polymath who discovered nitrous oxide,

Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) was an English polymath who discovered nitrous oxide, nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes denoted by a dot in its che ...

, ammonia, hydrogen chloride and (along with Carl Wilhelm Scheele and Antoine Lavoisier) oxygen. Beginning in 1775, Priestley published his research in '' Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air'', a six-volume work. The recent discoveries about these and other gases stimulated a great deal of interest in the European scientific community. Thomas Beddoes (1760–1808) was an English philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, physician and teacher of medicine, and like his older colleague Priestley, was also a member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham. With an eye toward making further advances in this new science as well as offering treatment for diseases previously thought to be untreatable (such as asthma and tuberculosis), Beddoes founded the ''Pneumatic Institution

The Pneumatic Institution (also referred to as Pneumatic Institute) was a medical research facility in Bristol, England, in 1799–1802. It was established by physician and science writer Thomas Beddoes to study the medical effects of gases, know ...

'' for inhalation gas therapy in 1798 at Dowry Square in Clifton, Bristol. Beddoes employed chemist and physicist Humphry Davy (1778–1829) as superintendent of the institute, and engineer James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was fun ...

(1736–1819) to help manufacture the gases. Other members of the Lunar Society such as Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

His poems ...

and Josiah Wedgwood were also actively involved with the institute.

During the course of his research at the Pneumatic Institution, Davy discovered the anesthetic properties of nitrous oxide. Davy, who coined the term "laughing gas" for nitrous oxide, published his findings the following year in the now-classic treatise, ''Researches, chemical and philosophical–chiefly concerning nitrous oxide or dephlogisticated nitrous air, and its respiration''. Davy was not a physician, and he never administered nitrous oxide during a surgical procedure. He was, however, the first to document the analgesic effects of nitrous oxide, as well as its potential benefits in relieving pain during surgery:

19th century

Eastern hemisphere

Takamine Tokumei from Shuri, Ryūkyū Kingdom, is reported to have made a general anesthesia in 1689 in the Ryukyus, now known as Okinawa. He passed on his knowledge to theSatsuma Satsuma may refer to:

* Satsuma (fruit), a citrus fruit

* ''Satsuma'' (gastropod), a genus of land snails

Places Japan

* Satsuma, Kagoshima, a Japanese town

* Satsuma District, Kagoshima, a district in Kagoshima Prefecture

* Satsuma Domain, a sout ...

doctors in 1690 and to Ryūkyūan doctors in 1714.

Hanaoka Seishū

was a Japanese surgeon of the Edo period with a knowledge of Chinese herbal medicine, as well as Western surgical techniques he had learned through ''Rangaku'' (literally "Dutch learning", and by extension "Western learning"). Hanaoka is said t ...

(華岡 青洲, 1760–1835) of Osaka was a Japanese surgeon of the Edo period with a knowledge of Chinese herbal medicine

Chinese herbology () is the theory of traditional Chinese herbal therapy, which accounts for the majority of treatments in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). A ''Nature'' editorial described TCM as "fraught with pseudoscience", and said that t ...

, as well as Western surgical techniques he had learned through '' Rangaku'' (literally "Dutch learning", and by extension "Western learning"). Beginning in about 1785, Hanaoka embarked on a quest to re-create a compound that would have pharmacologic properties similar to Hua Tuo's mafeisan. After years of research and experimentation, he finally developed a formula which he named ''tsūsensan'' (also known as ''mafutsu-san''). Like that of Hua Tuo, this compound was composed of extracts of several different plants, including:

* 2 parts ''bai zhi'' (''Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

:白芷'',''Angelica dahurica'');

* 2 parts ''cao wu'' (''Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

:草烏'',''Aconitum sp.'', ''monkshood'' or ''wolfsbane'');

* 2 parts ''chuān ban xia'' ('' Pinellia ternata'');

* 2 parts ''chuān xiōng'' (''Ligusticum wallichii'', ''Cnidium rhizome'', ''Cnidium officinale'' or ''Szechuan lovage'');

* 2 parts ''dong quai'' (''Angelica sinensis'' or ''female ginseng'');

* 1 part ''tian nan xing'' ('' Arisaema rhizomatum'' or ''cobra lily'')

* 8 parts ''yang jin hua'' (''Datura stramonium'', ''Korean morning glory'', ''thorn apple'', ''jimson weed'', ''devil's trumpet'', ''stinkweed'', or ''locoweed'').

The active ingredients in tsūsensan are scopolamine

Scopolamine, also known as hyoscine, or Devil's Breath, is a natural or synthetically produced tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic drug that is formally used as a medication for treating motion sickness and postoperative nausea and vomiting ...

, hyoscyamine

Hyoscyamine (also known as daturine or duboisine) is a naturally occurring tropane alkaloid and plant toxin. It is a secondary metabolite found in certain plants of the family Solanaceae, including henbane, mandrake, angel's trumpets, jimsonweed ...

, atropine

Atropine is a tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic medication used to treat certain types of nerve agent and pesticide poisonings as well as some types of slow heart rate, and to decrease saliva production during surgery. It is typically given i ...

, aconitine and angelicotoxin. When consumed in sufficient quantity, tsūsensan produces a state of general anesthesia and skeletal muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of muscl ...

paralysis

Paralysis (also known as plegia) is a loss of motor function in one or more muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory damage. In the United States, roughly 1 in 50 ...

. Shutei Nakagawa (1773–1850), a close friend of Hanaoka, wrote a small pamphlet titled "Mayaku-ko" ("narcotic powder") in 1796. Although the original manuscript was lost in a fire in 1867, this brochure described the current state of Hanaoka's research on general anesthesia.

On 13 October 1804, Hanaoka performed a partial mastectomy for breast cancer on a 60-year-old woman named Kan Aiya, using tsūsensan as a general anesthetic

General anaesthetics (or anesthetics, see spelling differences) are often defined as compounds that induce a loss of consciousness in humans or loss of righting reflex in animals. Clinical definitions are also extended to include an induced coma ...

. This is generally regarded today as the first reliable documentation of an operation to be performed under general anesthesia. Hanaoka went on to perform many operations using tsūsensan, including resection of malignant tumors, extraction of bladder stones

A bladder stone is a stone found in the urinary bladder.

Signs and symptoms

Bladder stones are small mineral deposits that can form in the bladder. In most cases bladder stones develop when the urine becomes very concentrated or when one is d ...

, and extremity amputation

Amputation is the removal of a limb by trauma, medical illness, or surgery. As a surgical measure, it is used to control pain or a disease process in the affected limb, such as malignancy or gangrene. In some cases, it is carried out on indi ...

s. Before his death in 1835, Hanaoka performed more than 150 operations for breast cancer.

Western hemisphere

Friedrich Sertürner (1783–1841) first isolated morphine from

Friedrich Sertürner (1783–1841) first isolated morphine from opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

in 1804; he named it morphine after Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams.

Henry Hill Hickman

Henry Hill Hickman (27 January 1800 – 2 April 1830) was an English physician and promoter of anaesthesia.

Life

He was born to tenant farmers at Lady Halton, (near Bromfield, just outside Ludlow, Shropshire). He was the fifth of thirteen c ...

(1800–1830) experimented with the use of carbon dioxide as an anesthetic in the 1820s. He would make the animal insensible, effectively via almost suffocating it with carbon dioxide, then determine the effects of the gas by amputating one of its limbs. In 1824, Hickman submitted the results of his research to the Royal Society in a short treatise titled ''Letter on suspended animation: with the view of ascertaining its probable utility in surgical operations on human subjects''. The response was an 1826 article in '' The Lancet'' titled "Surgical Humbug" that ruthlessly criticised his work. Hickman died four years later at age 30. Though he was unappreciated at the time of his death, his work has since been positively reappraised and he is now recognised as one of the fathers of anesthesia.

By the late 1830s, Humphry Davy's experiments had become widely publicized within academic circles in the northeastern United States. Wandering lecturers would hold public gatherings, referred to as "ether frolics", where members of the audience were encouraged to inhale diethyl ether or nitrous oxide to demonstrate the mind-altering properties of these agents while providing much entertainment to onlookers. Four notable men participated in these events and witnessed the use of ether in this manner. They were William Edward Clarke

William is a masculine given name of Norman French origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conques ...

(1819–1898), Crawford W. Long

Crawford Williamson Long (November 1, 1815 – June 16, 1878) was an American surgeon and pharmacist best known for his first use of inhaled sulfuric ether as an anesthetic, discovered by performing surgeries on disabled African American slaves ...

(1815–1878), Horace Wells (1815–1848), and William T. G. Morton (1819–1868).

While attending undergraduate school in Rochester, New York, in 1839, classmates Clarke and Morton apparently participated in ether frolics with some regularity. In January 1842, by now a medical student at Berkshire Medical College, Clarke administered ether to a Miss Hobbie, while Elijah Pope performed a dental extraction. In so doing, he became the first to administer an inhaled anesthetic to facilitate the performance of a surgical procedure. Clarke apparently thought little of his accomplishment, and chose neither to publish nor to pursue this technique any further. Indeed, this event is not even mentioned in Clarke's biography.

Crawford W. Long was a physician and pharmacist practicing in Jefferson, Georgia in the mid-19th century. During his time as a student at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in the late 1830s, he had observed and probably participated in the ether frolics that had become popular at that time. At these gatherings, Long observed that some participants experienced bumps and bruises, but afterward had no recall of what had happened. He postulated that diethyl ether produced pharmacologic effects similar to those of nitrous oxide. On 30 March 1842, he administered diethyl ether by inhalation to a man named James Venable, in order to remove a tumor from the man's neck. Long later removed a second tumor from Venable, again under ether anesthesia. He went on to employ ether as a general anesthetic for limb amputations and parturition. Long, however, did not publish his experience until 1849, thereby denying himself much of the credit he deserved.

With the beginnings of modern medicine the stage was set for physicians and surgeons to build a paradigm in which anesthesia became useful.

On 10 December 1844, Gardner Quincy Colton

Gardner Quincy Colton (February 7, 1814, Georgia, Vermont – August 10, 1898, Geneva, Switzerland) was an American showman, medicine man, lecturer, and former medical student who pioneered the use of nitrous oxide, or laughing gas, in dentistr ...

held a public demonstration of nitrous oxide in Hartford, Connecticut. One of the participants, Samuel A. Cooley, sustained a significant injury to his leg while under the influence of nitrous oxide without noticing the injury. Horace Wells, a Connecticut dentist present in the audience that day, immediately seized upon the significance of this apparent analgesic effect of nitrous oxide. The following day, Wells underwent a painless dental extraction while under the influence of nitrous oxide administered by Colton. Wells then began to administer nitrous oxide to his patients, successfully performing several dental extractions over the next couple of weeks.

William T. G. Morton, another New England dentist, was a former student and then-current business partner of Wells. He was also a former acquaintance and classmate of William Edward Clarke (the two had attended undergraduate school together in Rochester, New York). Morton arranged for Wells to demonstrate his technique for dental extraction under nitrous oxide general anesthesia at Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General or MGH) is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School located in the West End neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. It is the third oldest general hospital in the United Stat ...

, in conjunction with the prominent surgeon John Collins Warren. This demonstration, which took place on 20 January 1845, ended in failure when the patient cried out in pain in the middle of the operation.

On 30 September 1846, Morton administered diethyl ether to Eben Frost, a music teacher from Boston, for a dental extraction. Two weeks later, Morton became the first to publicly demonstrate the use of diethyl ether as a general anesthetic at Massachusetts General Hospital, in what is known today as the Ether Dome. On 16 October 1846, John Collins Warren removed a tumor from the neck of a local printer, Edward Gilbert Abbott. Upon completion of the procedure, Warren reportedly quipped, "Gentlemen, this is no humbug." News of this event rapidly traveled around the world. Robert Liston performed the first amputation in December of that year. Morton published his experience soon after. Harvard University professor Charles Thomas Jackson (1805–1880) later claimed that Morton stole his idea; Morton disagreed and a lifelong dispute began. For many years, Morton was credited as being the pioneer of general anesthesia in the Western hemisphere, despite the fact that his demonstration occurred four years after Long's initial experience. Long later petitioned William Crosby Dawson

William Crosby Dawson (January 4, 1798May 5, 1856) was a lawyer, judge, politician, and soldier from Georgia.

Early life, education and legal career

Dawson was born in Greensboro, Greene County, Georgia, January 4, 1798. His parents were Geo ...

(1798–1856), a United States Senator from Georgia at that time, to support his claim on the floor of the United States Senate as the first to use ether anesthesia.

In 1847, Scottish obstetrician James Young Simpson (1811–1870) of Edinburgh was the first to use chloroform

Chloroform, or trichloromethane, is an organic compound with chemical formula, formula Carbon, CHydrogen, HChlorine, Cl3 and a common organic solvent. It is a colorless, strong-smelling, dense liquid produced on a large scale as a precursor to ...

as a general anesthetic on a human (Robert Mortimer Glover

Dr Robert Mortimer Glover FRSE (1815-1859) was an English physician. In 1838 he co-founded the Paris Medical Society and served as its first Vice President. He won the Medical Society of London’s Fothergill Gold Medal in 1846 for his lecture ...

had written on this possibility in 1842 but only used it on dogs). The use of chloroform anesthesia expanded rapidly thereafter in Europe. Chloroform began to replace ether as an anesthetic in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century. It was soon abandoned in favor of ether when its hepatic and cardiac toxicity, especially its tendency to cause potentially fatal cardiac dysrhythmias, became apparent. In fact, the use of chloroform versus ether as the primary anesthetic gas varied by country and region. For instance, Britain and the American South stuck with chloroform while the American North returned to ether. John Snow

John Snow (15 March 1813 – 16 June 1858) was an English physician and a leader in the development of anaesthesia and medical hygiene. He is considered one of the founders of modern epidemiology, in part because of his work in tracing the so ...

quickly became the most experienced British physician working with the new anesthetic gases of ether and chloroform thus becoming, in effect, the first British anesthetist. Through his careful clinical records he was eventually able to convince the elite of London medicine that anesthesia (chloroform) had a rightful place in childbirth. Thus, in 1853 Queen Victoria's accoucheurs invited John Snow to anesthetize the Queen for the birth of her eighth child. From the beginnings of ether and chloroform anesthesia until well into the 20th century, the standard method of administration was the drop mask. A mask was placed over the patient's mouth with some fabric in it and the volatile liquid was dropped onto the mask with the patient spontaneously breathing. Later development of safe endotracheal tubes changed this. Because of the unique social setting of London medicine, anesthesia had become its own speciality there by the end of the nineteenth century, while in the rest of the United Kingdom and most of the world anesthesia remained under the purview of the surgeon who would assign the task to a junior doctor or nurse.

After Austrian diplomat Karl von Scherzer brought back sufficient quantities of coca leaves from Peru, in 1860 Albert Niemann isolated cocaine, which thus became the first local anesthetic.

In 1871, the German surgeon Friedrich Trendelenburg

Friedrich Trendelenburg (; 24 May 184415 December 1924) was a German surgeon. He was son of the philosophy, philosopher Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg, father of the pharmacology, pharmacologist Paul Trendelenburg and grandfather of the pharmaco ...

(1844–1924) published a paper describing the first successful elective human tracheotomy to be performed for the purpose of administration of general anesthesia.

In 1880, the Scottish surgeon William Macewen

Sir William Macewen, (; 22 June 1848 – 22 March 1924) was a Scottish surgeon. He was a pioneer in modern brain surgery, considered the ''father of neurosurgery'' and contributed to the development of bone graft surgery, the surgical treat ...

(1848–1924) reported on his use of orotracheal intubation as an alternative to tracheotomy to allow a patient with glottic edema to breathe, as well as in the setting of general anesthesia with chloroform

Chloroform, or trichloromethane, is an organic compound with chemical formula, formula Carbon, CHydrogen, HChlorine, Cl3 and a common organic solvent. It is a colorless, strong-smelling, dense liquid produced on a large scale as a precursor to ...

. All previous observations of the glottis and larynx (including those of Manuel García, Wilhelm Hack and Macewen) had been performed under indirect vision (using mirrors) until 23 April 1895, when Alfred Kirstein (1863–1922) of Germany first described direct visualization of the vocal cords. Kirstein performed the first direct laryngoscopy in Berlin, using an esophagoscope he had modified for this purpose; he called this device an ''autoscope''. The death of Emperor Frederick III (1831–1888) may have motivated Kirstein to develop the autoscope.

20th century

The 20th century saw the transformation of the practices of tracheotomy, endoscopy and non-surgical tracheal intubation from rarely employed procedures to essential components of the practices of anesthesia,

The 20th century saw the transformation of the practices of tracheotomy, endoscopy and non-surgical tracheal intubation from rarely employed procedures to essential components of the practices of anesthesia, critical care medicine

Intensive care medicine, also called critical care medicine, is a medical specialty that deals with seriously or critically ill patients who have, are at risk of, or are recovering from conditions that may be life-threatening. It includes pro ...

, emergency medicine

Emergency medicine is the medical speciality concerned with the care of illnesses or injuries requiring immediate medical attention. Emergency physicians (often called “ER doctors” in the United States) continuously learn to care for unsche ...

, gastroenterology, pulmonology and surgery.

In 1902, Hermann Emil Fischer

Hermann Emil Louis Fischer (; 9 October 1852 – 15 July 1919) was a German chemist and 1902 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He discovered the Fischer esterification. He also developed the Fischer projection, a symbolic way of dra ...

(1852–1919) and Joseph von Mering

Josef, Baron von Mering (28 February 1849, in Cologne – 5 January 1908, at Halle an der Saale, Germany) was a German physician.

Working at the University of Strasbourg, Mering was the first person to discover (in conjunction with Oskar Minkowsk ...

(1849–1908) discovered that diethylbarbituric acid

Barbital (or barbitone), marketed under the brand names Veronal for the pure acid and Medinal for the sodium salt, was the first commercially available barbiturate. It was used as a sleeping aid ( hypnotic) from 1903 until the mid-1950s. The chem ...

was an effective hypnotic

Hypnotic (from Greek ''Hypnos'', sleep), or soporific drugs, commonly known as sleeping pills, are a class of (and umbrella term for) psychoactive drugs whose primary function is to induce sleep (or surgical anesthesiaWhen used in anesthesia ...

agent. Also called barbital or ''Veronal'' (the trade name assigned to it by Bayer Pharmaceuticals

Bayer AG (, commonly pronounced ; ) is a German multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology company and one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world. Headquartered in Leverkusen, Bayer's areas of business include pharmaceutica ...

), this new drug became the first commercially marketed barbiturate

Barbiturates are a class of depressant drugs that are chemically derived from barbituric acid. They are effective when used medically as anxiolytics, hypnotics, and anticonvulsants, but have physical and psychological addiction potential as we ...

; it was used as a treatment for insomnia from 1903 until the mid-1950s.

Until 1913, oral and maxillofacial surgery was performed by mask inhalation anesthesia, topical application of local anesthetics to the mucosa

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It is ...

, rectal anesthesia, or intravenous

Intravenous therapy (abbreviated as IV therapy) is a medical technique that administers fluids, medications and nutrients directly into a person's vein. The intravenous route of administration is commonly used for rehydration or to provide nutrie ...

anesthesia. While otherwise effective, these techniques did not protect the airway from obstruction and also exposed patients to the risk of pulmonary aspiration of blood and mucus into the tracheobronchial tree. In 1913, Chevalier Jackson (1865–1958) was the first to report a high rate of success for the use of direct laryngoscopy as a means to intubate the trachea. Jackson introduced a new laryngoscope blade that had a light source at the distal tip, rather than the proximal light source used by Kirstein. This new blade incorporated a component that the operator could slide out to allow room for passage of an endotracheal tube or bronchoscope.

Also in 1913, Henry H. Janeway

Henry Harrington Janeway (19 March 1873 – 1 February 1921) was an American physician and pioneer of radiation therapy.

Publications

Janeway's clinical and experimental observations were published in medical journals of his time. His report on ' ...

(1873–1921) published results he had achieved using a laryngoscope he had recently developed. An American anesthesiologist practicing at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, Janeway was of the opinion that direct intratracheal insufflation of volatile anesthetics

An inhalational anesthetic is a chemical compound possessing general anesthetic properties that can be delivered via inhalation. They are administered through a face mask, laryngeal mask airway or tracheal tube connected to an anesthetic vapor ...

would provide improved conditions for otolaryngologic surgery. With this in mind, he developed a laryngoscope designed for the sole purpose of tracheal intubation. Similar to Jackson's device, Janeway's instrument incorporated a distal light source. Unique, however, was the inclusion of batteries

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

within the handle, a central notch in the blade for maintaining the tracheal tube in the midline of the oropharynx during intubation and a slight curve to the distal tip of the blade to help guide the tube through the glottis. The success of this design led to its subsequent use in other types of surgery. Janeway was thus instrumental in popularizing the widespread use of direct laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation in the practice of anesthesiology.

In 1928 Arthur Ernest Guedel

Arthur Ernest Guedel (June 13, 1883 – June 10, 1956) was an American anesthesiologist. He was known for his studies on the uptake and distribution of inhalational anesthetics, as well for defining the various stages of general anesthesia.

The gu ...

introduced the cuffed endotracheal tube, which allowed deep enough anesthesia that completely suppressed spontaneously respirations while the gas and oxygen were delivered via positive pressure ventilation controlled by the anesthesiologist. Also important for the development of modern anesthesia are anesthesia machines. Only three years later Joseph W. Gale developed the technology where the anesthesiologist was able to ventilate only one lung at a time. This allowed the development of thoracic surgery, which had previously been vexed by the pendelluft problem in which the bad lung being operated on inflated with patient exhalation due to the loss of vacuum with the thorax being open to the atmosphere. Eventually by early 1980s double lumen endotracheal tubes made out of clear plastic enabled anesthesiologists to selectively ventilate one lung while using flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy to block off the diseased lung and prevent cross contamination. One early device, the copper kettle, was developed by Dr. Lucien E. Morris at the University of Wisconsin.

Sodium thiopental, the first intravenous anesthetic, was synthesized in 1934 by Ernest H. Volwiler

Ernest Henry Volwiler (August 22, 1893 – October 3, 1992) was an American chemist. He spent his career at Abbott Laboratories working his way from staff chemist to CEO. He was a pioneer in the field of anesthetic pharmacology, assisting in th ...

(1893–1992) and Donalee L. Tabern (1900–1974), working for Abbott Laboratories

Abbott Laboratories is an American multinational medical devices and health care company with headquarters in Abbott Park, Illinois, United States. The company was founded by Chicago physician Wallace Calvin Abbott in 1888 to formulate known dr ...

. It was first used in humans on 8 March 1934 by Ralph M. Waters

Ralph Milton Waters (October 9, 1883 – December 19, 1979) was an American anesthesiologist known for introducing professionalism into the practice of anesthesia.

Medical career

Waters attended Western Reserve University Medical School and start ...

in an investigation of its properties, which were short-term anesthesia and surprisingly little analgesia. Three months later, John Silas Lundy

John Silas Lundy (July 6, 1894 – April 26, 1973) was an American physician and anesthesiologist who established the first post-anesthesia recovery room and the first blood bank in the United States.

References

*

*

*

*

1894 births

1973 d ...

started a clinical trial of thiopental at the Mayo Clinic

The Mayo Clinic () is a nonprofit American academic medical center focused on integrated health care, education, and research. It employs over 4,500 physicians and scientists, along with another 58,400 administrative and allied health staff, ...

at the request of Abbott Laboratories. Volwiler and Tabern were awarded U.S. Patent No. 2,153,729 in 1939 for the discovery of thiopental, and they were inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1986.

In 1939, the search for a synthetic substitute for atropine culminated serendipitously in the discovery of meperidine, the first opiate with a structure altogether different from that of morphine. This was followed in 1947 by the widespread introduction of methadone, another structurally unrelated compound with pharmacological properties similar to those of morphine.

After World War I, further advances were made in the field of intratracheal anesthesia. Among these were those made by Sir Ivan Whiteside Magill (1888–1986). Working at the Queen's Hospital for Facial and Jaw Injuries in Sidcup with plastic surgeon Sir Harold Gillies (1882–1960) and anesthetist E. Stanley Rowbotham (1890–1979), Magill developed the technique of awake blind nasotracheal intubation. Magill devised a new type of angulated forceps (the Magill forceps

Magill forceps are angled forceps used to guide a tracheal tube into the larynx or a nasogastric tube into the esophagus under direct vision. Other devices invented by Magill include the Magill laryngoscope blade, as well as several apparatuses for the administration of volatile anesthetic agents. The Magill curve of an endotracheal tube is also named for Magill.

The first hospital anesthesia department was established at the Massachusetts General Hospital in 1936, under the leadership of

The "digital revolution" of the 21st century has brought newer technology to the art and science of tracheal intubation. Several manufacturers have developed video laryngoscopes which employ digital technology such as the

The "digital revolution" of the 21st century has brought newer technology to the art and science of tracheal intubation. Several manufacturers have developed video laryngoscopes which employ digital technology such as the

Wood Library-Museum of Anesthesiology

The most comprehensive educational, scientific and archival resources in anesthesiology.

An article at University of Bristol providing interesting facts about chloroform.

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20051219095333/http://www.rcoa.ac.uk/index.asp?PageID=69 Royal College of Anaesthetists Patient Information page

''Turning the Pages''

a virtual reconstruction of Hanaoka's ''Surgical Casebook'', c. 1825. From the

Die Geschichte der Anästhesie

"Anesthesia as a specialty: Past, present and future"

Presentation by Prof. Janusz Andres. {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of General Anesthesia General anesthetics General anesthesia Drug discovery

Henry K. Beecher

Henry Knowles Beecher (February 4, 1904 – July 25, 1976) was a pioneering American anesthesiologist, medical ethicist, and investigator of the placebo effect at Harvard Medical School.

An article by Beecher's in 1966 on unethical medical exp ...

(1904–1976). Beecher, who received his training in surgery, had no previous experience in anesthesia.

Although initially used to reduce the sequelae of spasticity associated with electro-shock therapy for psychiatric disease, curare found use in the operating rooms at Bellvue by E.M. Papper and Stuart Cullen in the 1940s using preparations made by Squibb. This neuromuscular blockade permitted complete paralysis of the diaphragm and enabled control of ventilation via positive pressure ventilation. Mechanical ventilation first became common place with the polio epidemics of the 1950s, most notably in Denmark where an outbreak in 1952 lead to the creation of critical care medicine out of anesthesia. At first anesthesiologists hesitated to bring the ventilator into the operating theater unless necessary, but by the 1960s it became standard operating room equipment.

Sir Robert Macintosh

Sir Robert Reynolds Macintosh (17 October 1897, Timaru, New Zealand – 28 August 1989, Oxford, England) was a New Zealand-born British anaesthetist. He was the first professor of anaesthetics outside the United States.

Early life

Macintosh w ...

(1897–1989) achieved significant advances in techniques for tracheal intubation when he introduced his new curved laryngoscope blade in 1943. The Macintosh blade remains to this day the most widely used laryngoscope blade for orotracheal intubation. In 1949, Macintosh published a case report describing the novel use of a gum elastic urinary catheter as an endotracheal tube introducer to facilitate difficult tracheal intubation. Inspired by Macintosh's report, P. Hex Venn (who was at that time the anesthetic advisor to the British firm Eschmann Bros. & Walsh, Ltd.) set about developing an endotracheal tube introducer based on this concept. Venn's design was accepted in March 1973, and what became known as the Eschmann endotracheal tube introducer went into production later that year. The material of Venn's design was different from that of a gum elastic bougie in that it had two layers: a core of tube woven from polyester

Polyester is a category of polymers that contain the ester functional group in every repeat unit of their main chain. As a specific material, it most commonly refers to a type called polyethylene terephthalate (PET). Polyesters include natural ...

threads and an outer resin layer. This provided more stiffness but maintained the flexibility and the slippery surface. Other differences were the length (the new introducer was , which is much longer than the gum elastic bougie) and the presence of a 35° curved tip, permitting it to be steered around obstacles.

For over a hundred years the mainstay of inhalational anesthetics remained ether with cyclopropane

Cyclopropane is the cycloalkane with the molecular formula (CH2)3, consisting of three methylene groups (CH2) linked to each other to form a ring. The small size of the ring creates substantial ring strain in the structure. Cyclopropane itself ...

, which had been introduced in the 1930s. In 1956 halothane

Halothane, sold under the brand name Fluothane among others, is a general anaesthetic. It can be used to induce or maintain anaesthesia. One of its benefits is that it does not increase the production of saliva, which can be particularly useful i ...

was introduced which had the significant advantage of not being flammable. This reduced the risk of operating room fires. In the sixties the halogenated ether

A halogenated ether is a subcategory of a larger group of chemicals known as ethers. An ether is an organic chemical that contains an ether group—an oxygen atom connected to two (substituted) alkyl groups. A good example of an ether is t ...

s superseded Halothane

Halothane, sold under the brand name Fluothane among others, is a general anaesthetic. It can be used to induce or maintain anaesthesia. One of its benefits is that it does not increase the production of saliva, which can be particularly useful i ...

due to the rare, but significant side effects of cardiac arrhythmias and liver toxicity. The first two halogenated ethers were methoxyflurane

Methoxyflurane, sold under the brand name Penthrox among others, is an inhaled medication primarily used to reduce pain following trauma. It may also be used for short episodes of pain as a result of medical procedures. Onset of pain relief is ...

and enflurane

Enflurane (2-chloro-1,1,2-trifluoroethyl difluoromethyl ether) is a halogenated ether. Developed by Ross Terrell in 1963, it was first used clinically in 1966. It was increasingly used for inhalational anesthesia during the 1970s and 1980s but is ...

. These in turn were replaced by the current standards of isoflurane

Isoflurane, sold under the brand name Forane among others, is a general anesthetic. It can be used to start or maintain anesthesia; however, other medications are often used to start anesthesia rather than isoflurane, due to airway irritation w ...

, sevoflurane

Sevoflurane, sold under the brand name Sevorane, among others, is a sweet-smelling, nonflammable, highly fluorinated methyl isopropyl ether used as an inhalational anaesthetic for induction and maintenance of general anesthesia. After desflura ...

, and desflurane

Desflurane (1,2,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl difluoromethyl ether) is a highly fluorinated methyl ethyl ether used for maintenance of general anesthesia. Like halothane, enflurane, and isoflurane, it is a racemic mixture of (''R'') and (''S'') optical i ...

in the eighties and nineties although methoxyflurane

Methoxyflurane, sold under the brand name Penthrox among others, is an inhaled medication primarily used to reduce pain following trauma. It may also be used for short episodes of pain as a result of medical procedures. Onset of pain relief is ...

remains in use for prehospital anesthesia in Australia as Penthrox. Halothane

Halothane, sold under the brand name Fluothane among others, is a general anaesthetic. It can be used to induce or maintain anaesthesia. One of its benefits is that it does not increase the production of saliva, which can be particularly useful i ...

remains in common place throughout much of the developing world.

Many new intravenous and inhalational anesthetics were developed and brought into clinical use during the second half of the 20th century. Paul Janssen (1926–2003), the founder of Janssen Pharmaceutica, is credited with the development of over 80 pharmaceutical compounds. Janssen synthesized nearly all of the butyrophenone class of antipsychotic agents, beginning with haloperidol (1958) and droperidol

Droperidol (Inapsine, Droleptan, Dridol, Xomolix, Innovar ombination with fentanyl">fentanyl.html" ;"title="ombination with fentanyl">ombination with fentanyl is an antidopaminergic medication, drug used as an antiemetic (that is, to prevent o ...

(1961). These agents were rapidly integrated into the practice of anesthesia. In 1960, Janssen's team synthesized fentanyl, the first of the piperidinone-derived opioids. Fentanyl was followed by sufentanil (1974), alfentanil (1976), carfentanil (1976), and lofentanil (1980). Janssen and his team also developed etomidate (1964), a potent intravenous anesthetic induction agent.

The concept of using a fiberoptic endoscope for tracheal intubation was introduced by Peter Murphy, an English anesthetist, in 1967. By the mid-1980s, the flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope had become an indispensable instrument within the pulmonology

Pulmonology (, , from Latin ''pulmō, -ōnis'' "lung" and the Greek suffix "study of"), pneumology (, built on Greek πνεύμων "lung") or pneumonology () is a medical specialty that deals with diseases involving the respiratory tract. ...

and anesthesia communities.

21st century

The "digital revolution" of the 21st century has brought newer technology to the art and science of tracheal intubation. Several manufacturers have developed video laryngoscopes which employ digital technology such as the

The "digital revolution" of the 21st century has brought newer technology to the art and science of tracheal intubation. Several manufacturers have developed video laryngoscopes which employ digital technology such as the CMOS

Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS, pronounced "sea-moss", ) is a type of metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) fabrication process that uses complementary and symmetrical pairs of p-type and n-type MOSFE ...

active pixel sensor

An active-pixel sensor (APS) is an image sensor where each pixel sensor unit cell has a photodetector (typically a pinned photodiode) and one or more active transistors. In a metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) active-pixel sensor, MOS field-effec ...

(APS) to generate a view of the glottis so that the trachea may be intubated. The Glidescope video laryngoscope is one example of such a device.

Xenon has recently been approved in some jurisdictions as an anaesthetic agent which does not act as a greenhouse gas.

See also

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * Arashiro Toshiaki, ''Ryukyu-Okinawa Rekishi Jinbutsuden'', Okinawajijishuppan, 2006 p66 * "Reevaluation of surgical achievements by Tokumei Takamine". Matsuki A. Masui. November 2000; 49(11):1285-9. Japanese. * "The secret anesthetic used in the repair of a hare-lip performed by Tokumei Takamine in Ryukyu". Matsuki A. ''Nippon Ishigaku Zasshi''. October 1985 31(4):463-89. Japanese.External links

Wood Library-Museum of Anesthesiology

The most comprehensive educational, scientific and archival resources in anesthesiology.

An article at University of Bristol providing interesting facts about chloroform.

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20051219095333/http://www.rcoa.ac.uk/index.asp?PageID=69 Royal College of Anaesthetists Patient Information page

''Turning the Pages''

a virtual reconstruction of Hanaoka's ''Surgical Casebook'', c. 1825. From the

U.S. National Library of Medicine

The United States National Library of Medicine (NLM), operated by the United States federal government, is the world's largest medical library.

Located in Bethesda, Maryland, the NLM is an institute within the National Institutes of Health. Its ...

*Die Geschichte der Anästhesie

"Anesthesia as a specialty: Past, present and future"

Presentation by Prof. Janusz Andres. {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of General Anesthesia General anesthetics General anesthesia Drug discovery