Transatlantic Flights on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A transatlantic flight is the flight of an aircraft across the Atlantic Ocean from Europe, Africa, South Asia, or the Middle East to

In April 1913 the London newspaper ''The Daily Mail'' offered a prize of £10,000 (£ in ) to

The competition was suspended with the outbreak of World War I in 1914 but reopened after Armistice was declared in 1918. The war saw tremendous advances in aerial capabilities, and a real possibility of transatlantic flight by aircraft emerged.

Between 8 and 31 May 1919, the Curtiss seaplane ''

In April 1913 the London newspaper ''The Daily Mail'' offered a prize of £10,000 (£ in ) to

The competition was suspended with the outbreak of World War I in 1914 but reopened after Armistice was declared in 1918. The war saw tremendous advances in aerial capabilities, and a real possibility of transatlantic flight by aircraft emerged.

Between 8 and 31 May 1919, the Curtiss seaplane '' The first transatlantic flight by rigid airship, and the first return transatlantic flight, was made just a couple of weeks after the transatlantic flight of Alcock and Brown, on 2 July 1919. Major

The first transatlantic flight by rigid airship, and the first return transatlantic flight, was made just a couple of weeks after the transatlantic flight of Alcock and Brown, on 2 July 1919. Major

On 11 October 1928, Hugo Eckener, commanding the airship '' Graf Zeppelin'' as part of DELAG's operations, began the first non-stop transatlantic passenger flights, leaving Friedrichshafen, Germany, at 07:54 on 11 October 1928, and arriving at NAS Lakehurst, New Jersey, on 15 October.

Thereafter, DELAG used the ''Graf Zeppelin'' on regular scheduled passenger flights across the North Atlantic, from

On 11 October 1928, Hugo Eckener, commanding the airship '' Graf Zeppelin'' as part of DELAG's operations, began the first non-stop transatlantic passenger flights, leaving Friedrichshafen, Germany, at 07:54 on 11 October 1928, and arriving at NAS Lakehurst, New Jersey, on 15 October.

Thereafter, DELAG used the ''Graf Zeppelin'' on regular scheduled passenger flights across the North Atlantic, from

It would take two more decades after Alcock and Brown's first nonstop flight across the Atlantic in 1919, before commercial airplane flights became practical. The North Atlantic presented severe challenges for aviators due to weather and the long distances involved, with few stopping points. Initial transatlantic services, therefore, focused on the South Atlantic, where a number of French, German, and Italian airlines offered seaplane service for mail between South America and West Africa in the 1930s.

Between February 1934 and August 1939

It would take two more decades after Alcock and Brown's first nonstop flight across the Atlantic in 1919, before commercial airplane flights became practical. The North Atlantic presented severe challenges for aviators due to weather and the long distances involved, with few stopping points. Initial transatlantic services, therefore, focused on the South Atlantic, where a number of French, German, and Italian airlines offered seaplane service for mail between South America and West Africa in the 1930s.

Between February 1934 and August 1939  In the 1930s a flying boat route was the only practical means of transatlantic air travel, as land-based aircraft lacked sufficient range for the crossing. An agreement between the governments of the US, Britain, Canada, and the Irish Free State in 1935 set aside the Irish town of Foynes, the most westerly port in Ireland, as the terminal for all such services to be established.

Imperial Airways had bought the Short Empire flying boat, primarily for use along the empire routes to Africa, Asia and Australia, and had established an international airport on Darrell's Island, in the Imperial fortress colony of Bermuda (640 miles off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina), which began serving both Imperial Airways (subsequently renamed British Overseas Airways Corporation, or BOAC) and Pan American World Airways (PAA) flights from the United States in 1936, but began exploring the possibility of using it for transatlantic flights from 1937. PAA would begin scheduled trans-Atlantic flights via Bermuda before Imperial Airways did, enabling the United States Government to covertly assist the British Government before the United States entry into the Second World War as mail was taken off trans-Atlantic PAA flights by the Imperial Censorship of British Security Co-ordination to search for secret communications from Axis spies operating in the United States, including the Joe K ring, with information gained being shared with the

In the 1930s a flying boat route was the only practical means of transatlantic air travel, as land-based aircraft lacked sufficient range for the crossing. An agreement between the governments of the US, Britain, Canada, and the Irish Free State in 1935 set aside the Irish town of Foynes, the most westerly port in Ireland, as the terminal for all such services to be established.

Imperial Airways had bought the Short Empire flying boat, primarily for use along the empire routes to Africa, Asia and Australia, and had established an international airport on Darrell's Island, in the Imperial fortress colony of Bermuda (640 miles off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina), which began serving both Imperial Airways (subsequently renamed British Overseas Airways Corporation, or BOAC) and Pan American World Airways (PAA) flights from the United States in 1936, but began exploring the possibility of using it for transatlantic flights from 1937. PAA would begin scheduled trans-Atlantic flights via Bermuda before Imperial Airways did, enabling the United States Government to covertly assist the British Government before the United States entry into the Second World War as mail was taken off trans-Atlantic PAA flights by the Imperial Censorship of British Security Co-ordination to search for secret communications from Axis spies operating in the United States, including the Joe K ring, with information gained being shared with the  On 5 July 1937, A.S. Wilcockson flew a Short Empire for Imperial Airways from Foynes to Botwood,

On 5 July 1937, A.S. Wilcockson flew a Short Empire for Imperial Airways from Foynes to Botwood,  Meanwhile, Pan Am bought nine

Meanwhile, Pan Am bought nine

''Travel Scholar'', Sound Message, LLC. Retrieved: 19 August 2006. The ''Yankee Clippers inaugural trip across the Atlantic was on 24 June 1939. Its route was from Southampton to Port Washington, New York with intermediate stops at Foynes, Ireland,

It was from the emergency exigencies of World War II that crossing the Atlantic by land-based aircraft became a practical and commonplace possibility. With the

It was from the emergency exigencies of World War II that crossing the Atlantic by land-based aircraft became a practical and commonplace possibility. With the

Juno Beach Centre In 1941, MAP took the operation off CPR to put the whole operation under the Atlantic Ferry Organization ("Atfero") was set up by Morris W. Wilson, a banker in Montreal. Wilson hired civilian pilots to fly the aircraft to the UK. The pilots were then ferried back in converted RAF Liberators. "Atfero hired the pilots, planned the routes, selected the airports ndset up weather and radiocommunication stations." The organization was passed to Air Ministry administration though retaining civilian pilots, some of which were Americans, alongside RAF navigators and British radio operators. After completing delivery, crews were flown back to Canada for the next run. RAF Ferry Command was formed on 20 July 1941, by the raising of the RAF Atlantic Ferry Service to Command status."RAF Home Commands formed between 1939–1957"

The organization was passed to Air Ministry administration though retaining civilian pilots, some of which were Americans, alongside RAF navigators and British radio operators. After completing delivery, crews were flown back to Canada for the next run. RAF Ferry Command was formed on 20 July 1941, by the raising of the RAF Atlantic Ferry Service to Command status."RAF Home Commands formed between 1939–1957"

Air of Authority – A History of RAF Organisation Its commander for its whole existence was

Ferry Command did this over only one area of the world, rather than the more general routes that Transport Command later developed. The Command's operational area was the north Atlantic, and its responsibility was to bring the larger aircraft that had the range to do the trip over the ocean from American and Canadian factories to the RAF home Commands. With the entry of the United States into the War, the Atlantic Division of the United States Army Air Forces Air Transport Command began similar ferrying services to transport aircraft, supplies and passengers to the British Isles. By September 1944 British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), as Imperial Airways had by then become, had made 1,000 transatlantic crossings. After World War II long runways were available, and North American and European carriers such as Pan Am, In May 1952, BOAC was the first airline to introduce a

In May 1952, BOAC was the first airline to introduce a

;First transatlantic flight: On 8–31 May 1919, the U.S. Navy Curtiss NC-4

;First transatlantic flight: On 8–31 May 1919, the U.S. Navy Curtiss NC-4

FAI

; Mass flight: Notable mass transatlantic flight: On 1–15 July 1933, Gen. Italo Balbo of Italy led 24

* 2 May 2002: Lindbergh's grandson,

* 2 May 2002: Lindbergh's grandson,

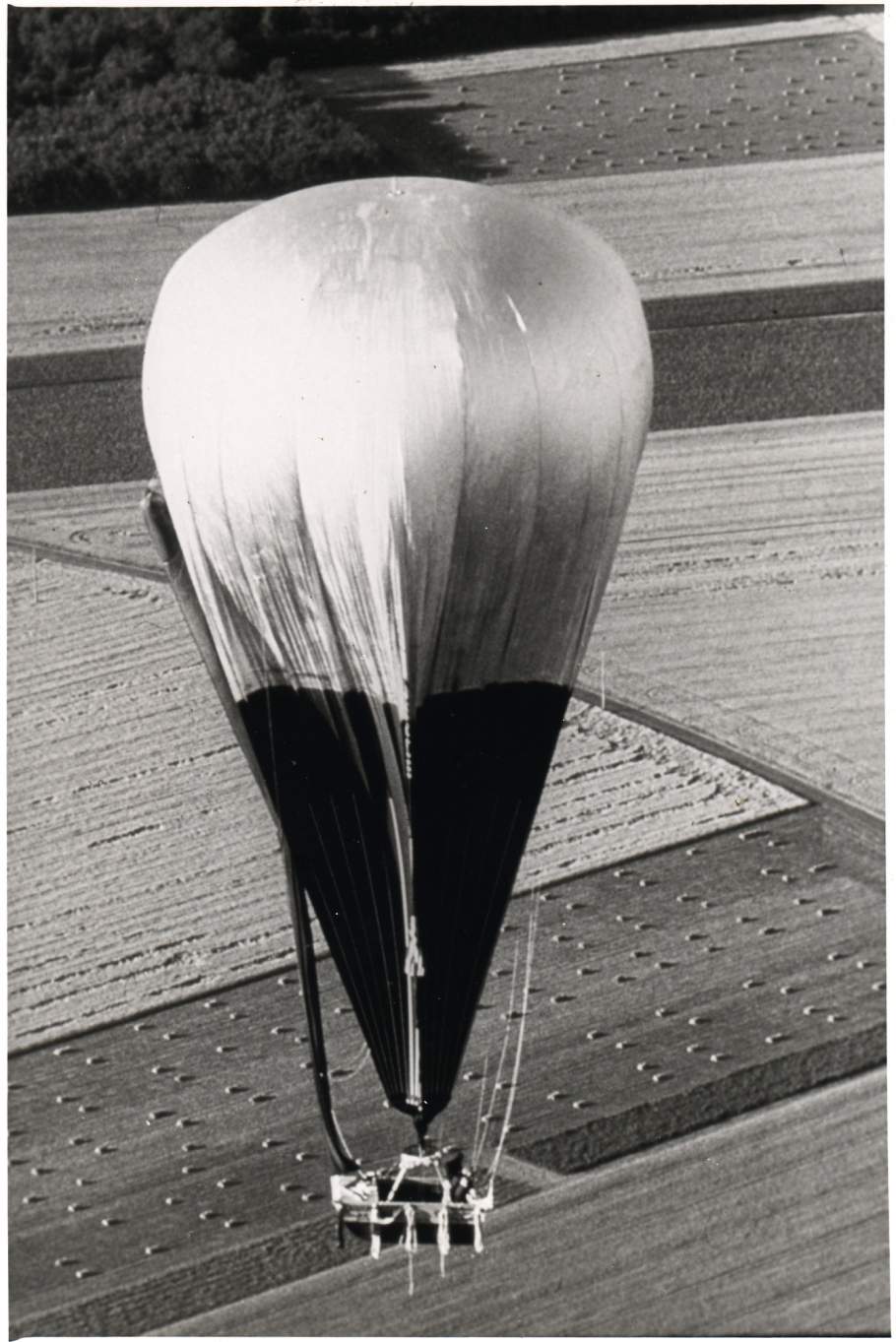

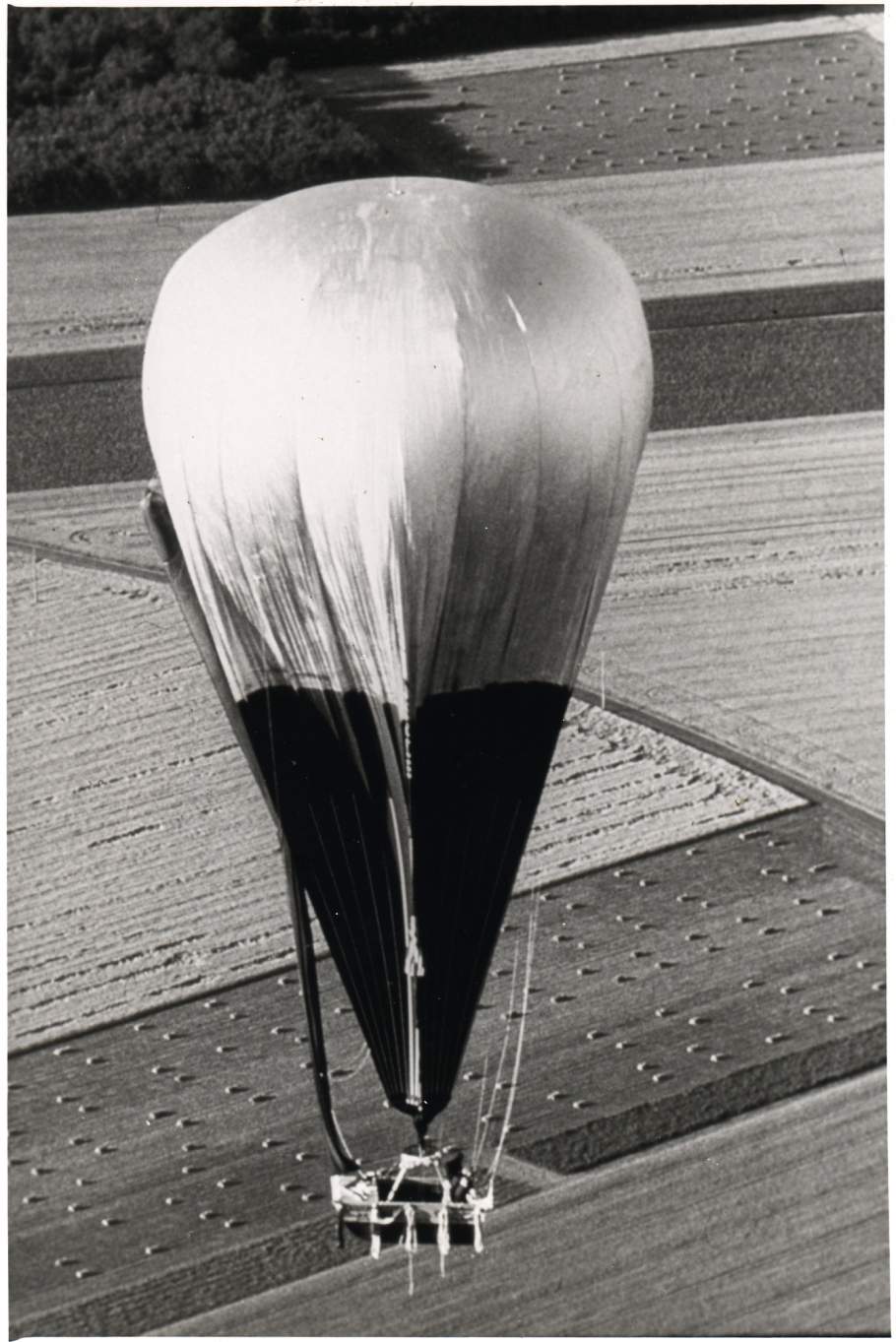

''The Guardian''. Retrieved: 13 September 2013. attached to 370 balloons filled with helium. A short time later, due to difficulty controlling the balloons, Trappe was forced to land near the town of York Harbour, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Trappe had expected to arrive in Europe sometime between three and six days after liftoff. The craft ascended by the dropping of ballast, and was to drift at an altitude of up to 25,000 ft (7.6 km). It was intended to follow wind currents toward Europe, the intended destination, however, unpredictable wind currents could have forced the craft to North Africa or Norway. To descend, Trappe would have popped or released some of the balloons. The last time the Atlantic was crossed by helium balloon was in 1984 by Colonel

''sr-71.org''. Retrieved: 18 October 2009. The fastest time for an airliner is 2 hours 53 minutes for

Current North Atlantic Weather and Tracks

– a 1948 '' Flight'' article on the first jet crossing of the Atlantic

"North Atlantic Retrospect and Prospect"

a 1969 ''Flight'' article

a 1961 ''Flight'' article on the 1919 flights of R 34 * {{authority control History of aviation History of the Atlantic Ocean Aviation in the Atlantic Ocean

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

, Central America, or South America, or ''vice versa''. Such flights have been made by fixed-wing aircraft

A fixed-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air flying machine, such as an airplane, which is capable of flight using wings that generate lift caused by the aircraft's forward airspeed and the shape of the wings. Fixed-wing aircraft are distinc ...

, airships, balloons and other aircraft.

Early aircraft engine

An aircraft engine, often referred to as an aero engine, is the power component of an aircraft propulsion system. Most aircraft engines are either piston engines or gas turbines, although a few have been rocket powered and in recent years many ...

s did not have the reliability nor the power to lift the required fuel to make a transatlantic flight. There were difficulties navigating over the featureless expanse of water for thousands of miles, and the weather, especially in the North Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe and ...

, is unpredictable. Since the middle of the 20th century, however, transatlantic flight has become routine, for commercial, military, diplomatic

Diplomatics (in American English, and in most anglophone countries), or diplomatic (in British English), is a scholarly discipline centred on the critical analysis of documents: especially, historical documents. It focuses on the conventions, p ...

, and other purposes.

History

The idea of transatlantic flight came about with the advent of the hot air balloon. The balloons of the period were inflated withcoal gas

Coal gas is a flammable gaseous fuel made from coal and supplied to the user via a piped distribution system. It is produced when coal is heated strongly in the absence of air. Town gas is a more general term referring to manufactured gaseous ...

, a moderate lifting medium compared to hydrogen or helium, but with enough lift to use the winds that would later be known as the Jet Stream

Jet streams are fast flowing, narrow, meandering thermal wind, air currents in the Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheres of some planets, including Earth. On Earth, the main jet streams are located near the altitude of the tropopause and are west ...

. In 1859, John Wise built an enormous aerostat named the ''Atlantic'', intending to cross the Atlantic. The flight lasted less than a day, crash-landing in Henderson, New York. Thaddeus S. C. Lowe

Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe (August 20, 1832 – January 16, 1913), also known as Professor T. S. C. Lowe, was an American Civil War aeronaut, scientist and inventor, mostly self-educated in the fields of chemistry, meteorology, and a ...

prepared a massive balloon of called the ''City of New York'' to take off from Philadelphia in 1860, but was interrupted by the onset of the American Civil War in 1861. The first successful transatlantic flight in a balloon was the Double Eagle II from Presque Isle, Maine, to Miserey

Miserey () is a commune in the Eure department in the Normandy region in Northern France. In 2017, it had a population of 629.

History

On 23 August 1944, the first Recon Platoon of the 823rd Tank Destroyer Bn., 30th Infantry Division was order ...

, near Paris in 1978.

First transatlantic flights

In April 1913 the London newspaper ''The Daily Mail'' offered a prize of £10,000 (£ in ) to

The competition was suspended with the outbreak of World War I in 1914 but reopened after Armistice was declared in 1918. The war saw tremendous advances in aerial capabilities, and a real possibility of transatlantic flight by aircraft emerged.

Between 8 and 31 May 1919, the Curtiss seaplane ''

In April 1913 the London newspaper ''The Daily Mail'' offered a prize of £10,000 (£ in ) to

The competition was suspended with the outbreak of World War I in 1914 but reopened after Armistice was declared in 1918. The war saw tremendous advances in aerial capabilities, and a real possibility of transatlantic flight by aircraft emerged.

Between 8 and 31 May 1919, the Curtiss seaplane ''NC-4

The NC-4 was a Curtiss NC flying boat that was the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, albeit not non-stop. The NC designation was derived from the collaborative efforts of the Navy (N) and Curtiss (C). The NC series flying boats w ...

'' made a crossing of the Atlantic flying from the U.S. to Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, then to the Azores, and on to mainland Portugal and finally the United Kingdom. The whole journey took 23 days, with six stops along the way. A trail of 53 "station ships" across the Atlantic gave the aircraft points to navigate by. This flight was not eligible for the ''Daily Mail'' prize since it took more than 72 consecutive hours and also because more than one aircraft was used in the attempt.

There were four teams competing for the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic. They were Australian pilot Harry Hawker

Harry George Hawker, MBE, AFC (22 January 1889 – 12 July 1921) was an Australian aviation pioneer. He was the chief test pilot for Sopwith and was also involved in the design of many of their aircraft. After the First World War, he co-fou ...

with observer Kenneth Mackenzie-Grieve in a single-engine Sopwith Atlantic

The Sopwith Atlantic was an experimental British long-range aircraft of 1919. It was a single-engined biplane that was designed and built to be the first aeroplane to cross the Atlantic Ocean non-stop. It took off on an attempt to cross the A ...

; Frederick Raynham and C. W. F. Morgan in a Martinsyde

Martinsyde was a British aircraft and motorcycle manufacturer between 1908 and 1922, when it was forced into liquidation by a factory fire.

History

The company was first formed in 1908 as a partnership between H.P. Martin and George Handasyde ...

; the Handley Page

Handley Page Limited was a British aerospace manufacturer. Founded by Frederick Handley Page (later Sir Frederick) in 1909, it was the United Kingdom's first publicly traded aircraft manufacturing company. It went into voluntary liquidation a ...

Group, led by Mark Kerr; and the Vickers entry John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown. Each group had to ship its aircraft to Newfoundland and make a rough field for the takeoff.

Hawker and Mackenzie-Grieve made the first attempt on 18 May, but engine failure brought them down in the ocean where they were rescued. Raynham and Morgan also made an attempt on 18 May but crashed on takeoff due to the high fuel load. The Handley Page team was in the final stages of testing its aircraft for the flight in June, but the Vickers group was ready earlier.

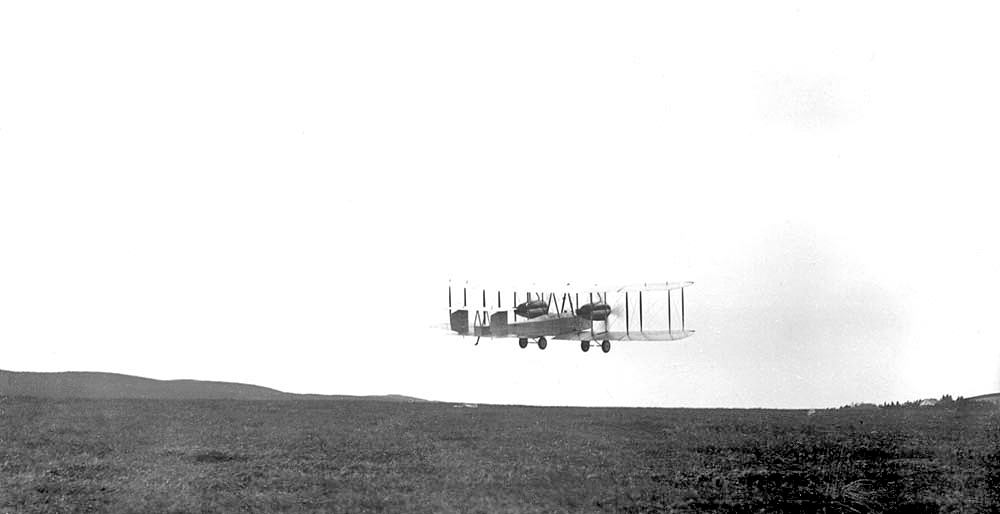

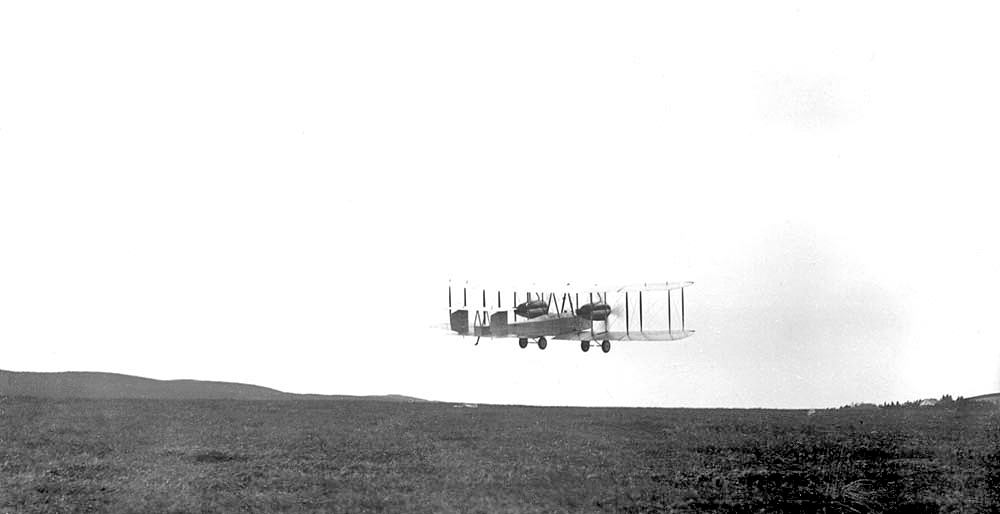

During 14–15 June 1919, the British aviators Alcock and Brown made the first non-stop transatlantic flight. During the War, Alcock resolved to fly the Atlantic, and after the war he approached the Vickers engineering and aviation firm at Weybridge, which had considered entering its Vickers Vimy IV twin-engined bomber in the competition but had not yet found a pilot. Alcock's enthusiasm impressed Vickers's team, and he was appointed as its pilot. Work began on converting the Vimy for the long flight, replacing its bomb racks with extra petrol tanks. Shortly afterwards Brown, who was unemployed, approached Vickers seeking a post and his knowledge of long-distance navigation convinced them to take him on as Alcock's navigator.

Vickers's team quickly assembled its plane and at around 1:45 p.m. on 14 June, while the Handley Page team was conducting yet another test, the Vickers plane took off from Lester's Field, in St John's, Newfoundland

St. John's is the capital and largest city of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, located on the eastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland.

The city spans and is the easternmost city in North America ...

.

Alcock and Brown flew the modified Vickers Vimy, powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle 360 hp engines. It was not an easy flight, with unexpected fog, and a snow storm almost causing the crewmen to crash into the sea. Their altitude varied between sea level and and upon takeoff, they carried 865 imperial gallons (3,900 L) of fuel. They made landfall in Clifden, County Galway

"Righteousness and Justice"

, anthem = ()

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Galway.svg

, map_caption = Location in Ireland

, area_footnotes =

, area_total_km2 = ...

at 8:40 a.m. on 15 June 1919, not far from their intended landing place, after less than sixteen hours of flying.

The Secretary of State for Air

The Secretary of State for Air was a Secretary of State (United Kingdom), secretary of state position in the British government, which existed from 1919 to 1964. The person holding this position was in charge of the Air Ministry. The Secretar ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, presented Alcock and Brown with the ''Daily Mail'' prize for the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean in "less than 72 consecutive hours". There was a small amount of mail carried on the flight making it also the first transatlantic airmail flight.

The two aviators were awarded the honour of Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (KBE) one week later by King George V at Windsor Castle.

The first transatlantic flight by rigid airship, and the first return transatlantic flight, was made just a couple of weeks after the transatlantic flight of Alcock and Brown, on 2 July 1919. Major

The first transatlantic flight by rigid airship, and the first return transatlantic flight, was made just a couple of weeks after the transatlantic flight of Alcock and Brown, on 2 July 1919. Major George Herbert Scott

Major George Herbert "Lucky Breeze" Scott, CBE, AFC, (25 May 1888 – 5 October 1930) was a British airship pilot and engineer. After serving in the Royal Naval Air Service and Royal Air Force during World War I, Scott went on to command the ai ...

of the Royal Air Force flew the airship R34 with his crew and passengers from RAF East Fortune, Scotland to Mineola, New York (on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

), covering a distance of about in about four and a half days.

The flight was intended as a testing ground for postwar commercial services by airship (see Imperial Airship Scheme), and it was the first flight to transport paying passengers. The R34 wasn't built as a passenger carrier, so extra accommodations was arranged by slinging hammocks in the keel walkway. The return journey to Pulham in Norfolk, was from 10 to 13 July over some 75 hours.

The first aerial crossing of the South Atlantic was made by the Portuguese naval aviators Gago Coutinho

Carlos Viegas Gago Coutinho, GCTE, GCC, generally known simply as Gago Coutinho (; 17 February 1869 – 18 February 1959) was a Portuguese geographer, cartographer, naval officer, historian and aviator. An aviation pioneer, Gago Coutinho and Sac ...

and Sacadura Cabral in 1922. Coutinho and Cabral flew from Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

, Portugal, to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in stages, using three different Fairey III biplanes, and they covered a distance of between 30 March and 17 June.

The first transatlantic flight between Spain and South America was completed in January 1926 with a crew of Spanish aviators on board '' Plus Ultra'', a Dornier Do J

The Dornier Do J ''Wal'' ("whale") is a twin-engine German flying boat of the 1920s designed by '' Dornier Flugzeugwerke''. The Do J was designated the Do 16 by the Reich Air Ministry (''RLM'') under its aircraft designation system of 1933.

...

flying boat; the crew was the captain Ramón Franco, co-pilot Julio Ruiz de Alda Miqueleiz, Teniente de Navio (Navy Lieutenant), Juan Manuel Durán, and Pablo Rada.

The first transpolar flight eastbound and the first flight crossing the North Pole ever, was the airship carrying Norwegian explorer and pilot Roald Amundsen on 11 May 1926. He flew with the airship "NORGE" ("Norway") piloted by the Italian colonel Umberto Nobile, non-stop from Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), also known as Spitsbergen, or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it is about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group range ...

, Norway to Teller, Alaska, USA. The flight lasted for 72 hours.

The first night-time crossing of the South Atlantic was accomplished during 16–17 April 1927 by the Portuguese aviators Sarmento de Beires

José Manuel Sarmento de Beires (4 September 1892 – 8 June 1974) was a Portuguese Army officer and an aviation pioneer.

Sarmento de Beires became famous for piloting the first night-time aerial crossing of the Atlantic, in April 1927.

The fir ...

, Jorge de Castilho and Manuel Gouveia, flying from the Bijagós Archipelago

The Bissagos Islands, also spelled Bijagós ( pt, Arquipélago dos Bijagós), are a group of about 88 islands and islets located in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Guinea-Bissau. The archipelago was formed from the ancient delta of the Geb ...

, Portuguese Guinea, to Fernando de Noronha, Brazil in the ''Argos'', a Dornier Wal

The Dornier Do J ''Wal'' ("whale") is a twin-engine German flying boat of the 1920s designed by ''Dornier Flugzeugwerke''. The Do J was designated the Do 16 by the Reich Air Ministry (''RLM'') under its aircraft designation system of 1933.

De ...

flying boat.

In the early morning of 20 May 1927, Charles Lindbergh took off from Roosevelt Field, Mineola, New York, on his successful attempt to fly nonstop from New York to the European continental land mass. Over the next 33.5 hours, Lindbergh and the ''Spirit of St. Louis

The ''Spirit of St. Louis'' (formally the Ryan NYP, registration: N-X-211) is the custom-built, single-engine, single-seat, high-wing monoplane that was flown by Charles Lindbergh on May 20–21, 1927, on the first solo nonstop transatlant ...

'' encountered many challenges before landing at Le Bourget Airport near Paris, at 10:22 p.m. on 21 May 1927, completing the first solo crossing of the Atlantic.

The first east-west non-stop transatlantic crossing by an aeroplane was made in 1928 by the ''Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state consis ...

'', a German Junkers W33 type aircraft, from Baldonnel Airfield

Casement Aerodrome ( ga, Aeradróm Mhic Easmainn) or Baldonnel Aerodrome is a military airbase to the southwest of Dublin, Ireland situated off the N7 main road route to the south and south west. It is the headquarters and the sole airfield of ...

in County Dublin, Ireland.

On 18 August 1932 Jim Mollison made the first east-to-west solo trans-Atlantic flight; flying from Portmarnock in Ireland to Pennfield, New Brunswick, Canada in a de Havilland Puss Moth.

In 1936 the first woman aviator to cross the Atlantic east to west, and the first person to fly solo from England to North America, was Beryl Markham

Beryl Markham (née Clutterbuck; 26 October 1902 – 3 August 1986) was a Kenyan aviator born in England (one of the first bush flying, bush pilots), adventurer, racehorse trainer and author. She was the first person to fly solo, non-stop acros ...

. She wrote about her adventures in her memoir, ''West with the Night''.

The first transpolar transatlantic (and transcontinental) crossing was the piloted by the crew led by Valery Chkalov covering some over 63 hours from Moscow, Russia to Vancouver, Washington from 18–20 June 1937.

Commercial airship flights

On 11 October 1928, Hugo Eckener, commanding the airship '' Graf Zeppelin'' as part of DELAG's operations, began the first non-stop transatlantic passenger flights, leaving Friedrichshafen, Germany, at 07:54 on 11 October 1928, and arriving at NAS Lakehurst, New Jersey, on 15 October.

Thereafter, DELAG used the ''Graf Zeppelin'' on regular scheduled passenger flights across the North Atlantic, from

On 11 October 1928, Hugo Eckener, commanding the airship '' Graf Zeppelin'' as part of DELAG's operations, began the first non-stop transatlantic passenger flights, leaving Friedrichshafen, Germany, at 07:54 on 11 October 1928, and arriving at NAS Lakehurst, New Jersey, on 15 October.

Thereafter, DELAG used the ''Graf Zeppelin'' on regular scheduled passenger flights across the North Atlantic, from Frankfurt-am-Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian dialects, Hessian: , "Franks, Frank ford (crossing), ford on the Main (river), Main"), is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as o ...

to Lakehurst. In the summer of 1931 a South Atlantic route was introduced, from Frankfurt and Friedrichshafen to Recife and Rio de Janeiro. Between 1931 and 1937 the ''Graf Zeppelin'' crossed the South Atlantic 136 times.

The British rigid airship R100 made a successful return trip from Cardington to Montreal in July–August 1930, in what was intended to be a proving flight for regularly scheduled passenger services. Following the R101 disaster in October 1930, the British rigid airship program was abandoned and the R100 scrapped, leaving DELAG as the sole remaining operator of transatlantic passenger airship flights.

In 1936 DELAG began passenger flights with '' LZ 129 Hindenburg'', and made 36 Atlantic crossings (North and South). The first passenger trip across the North Atlantic left Friedrichshafen on 6 May with 56 crew and 50 passengers, arriving Lakehurst on 9 May. Fare was $400 one way; the ten westward trips that season took 53 to 78 hours and eastward took 43 to 61 hours. The last eastward trip of the year left Lakehurst on 10 October; the first North Atlantic trip of 1937 ended in the Hindenburg disaster.

Commercial aeroplane service attempts

It would take two more decades after Alcock and Brown's first nonstop flight across the Atlantic in 1919, before commercial airplane flights became practical. The North Atlantic presented severe challenges for aviators due to weather and the long distances involved, with few stopping points. Initial transatlantic services, therefore, focused on the South Atlantic, where a number of French, German, and Italian airlines offered seaplane service for mail between South America and West Africa in the 1930s.

Between February 1934 and August 1939

It would take two more decades after Alcock and Brown's first nonstop flight across the Atlantic in 1919, before commercial airplane flights became practical. The North Atlantic presented severe challenges for aviators due to weather and the long distances involved, with few stopping points. Initial transatlantic services, therefore, focused on the South Atlantic, where a number of French, German, and Italian airlines offered seaplane service for mail between South America and West Africa in the 1930s.

Between February 1934 and August 1939 Lufthansa

Deutsche Lufthansa AG (), commonly shortened to Lufthansa, is the flag carrier of Germany. When combined with its subsidiaries, it is the second- largest airline in Europe in terms of passengers carried. Lufthansa is one of the five founding m ...

operated a regular airmail service between Natal, Brazil, and , continuing ''via'' the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

and Spain to Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the ...

, Germany. From December 1935, '' Air France'' opened a regular weekly airmail route between South America and Africa. German airlines, such as ''Deutsche Luft Hansa'', experimented with mail routes over the North Atlantic in the early 1930s, with flying boats and dirigibles.

In the 1930s a flying boat route was the only practical means of transatlantic air travel, as land-based aircraft lacked sufficient range for the crossing. An agreement between the governments of the US, Britain, Canada, and the Irish Free State in 1935 set aside the Irish town of Foynes, the most westerly port in Ireland, as the terminal for all such services to be established.

Imperial Airways had bought the Short Empire flying boat, primarily for use along the empire routes to Africa, Asia and Australia, and had established an international airport on Darrell's Island, in the Imperial fortress colony of Bermuda (640 miles off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina), which began serving both Imperial Airways (subsequently renamed British Overseas Airways Corporation, or BOAC) and Pan American World Airways (PAA) flights from the United States in 1936, but began exploring the possibility of using it for transatlantic flights from 1937. PAA would begin scheduled trans-Atlantic flights via Bermuda before Imperial Airways did, enabling the United States Government to covertly assist the British Government before the United States entry into the Second World War as mail was taken off trans-Atlantic PAA flights by the Imperial Censorship of British Security Co-ordination to search for secret communications from Axis spies operating in the United States, including the Joe K ring, with information gained being shared with the

In the 1930s a flying boat route was the only practical means of transatlantic air travel, as land-based aircraft lacked sufficient range for the crossing. An agreement between the governments of the US, Britain, Canada, and the Irish Free State in 1935 set aside the Irish town of Foynes, the most westerly port in Ireland, as the terminal for all such services to be established.

Imperial Airways had bought the Short Empire flying boat, primarily for use along the empire routes to Africa, Asia and Australia, and had established an international airport on Darrell's Island, in the Imperial fortress colony of Bermuda (640 miles off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina), which began serving both Imperial Airways (subsequently renamed British Overseas Airways Corporation, or BOAC) and Pan American World Airways (PAA) flights from the United States in 1936, but began exploring the possibility of using it for transatlantic flights from 1937. PAA would begin scheduled trans-Atlantic flights via Bermuda before Imperial Airways did, enabling the United States Government to covertly assist the British Government before the United States entry into the Second World War as mail was taken off trans-Atlantic PAA flights by the Imperial Censorship of British Security Co-ordination to search for secret communications from Axis spies operating in the United States, including the Joe K ring, with information gained being shared with the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

. The range of the Short Empire flying boat was less than that of the equivalent US Sikorsky "Clipper" flying boats and as such was initially unable to provide a true trans-Atlantic service.

Two flying boats (''Caledonia'' and ''Cambria'') were lightened and given long range tanks to increase the aircraft's range to .

In the US, attention was at first focused on transatlantic flight for a faster postal service between Europe and the United States. In 1931 W. Irving Glover, the second assistant postmaster, wrote an article for '' Popular Mechanics'' on the challenges and the need for a regular service. In the 1930s, under the direction of Juan Trippe, Pan American began to get interested in the feasibility of a transatlantic passenger service using flying boats.

On 5 July 1937, A.S. Wilcockson flew a Short Empire for Imperial Airways from Foynes to Botwood,

On 5 July 1937, A.S. Wilcockson flew a Short Empire for Imperial Airways from Foynes to Botwood, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

and Harold Gray piloted a Sikorsky S-42 for Pan American in the opposite direction. Both flights were a success and both airlines made a series of subsequent proving flights that same year to test out a variety of different weather conditions. Air France also became interested and began experimental flights in 1938.Gandt, Robert L. ''China Clipper—The Age of the Great Flying Boats''. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1991. .

As the Short Empire only had enough range with enlarged fuel tanks at the expense of passenger room, a number of pioneering experiments were done with the aircraft to work around the problem. It was known that aircraft could maintain flight with a greater load than is possible to take off with, so Major Robert H. Mayo, Technical general manager at Imperial Airways, proposed mounting a small, long-range seaplane on top of a larger carrier aircraft, using the combined power of both to bring the smaller aircraft to operational height, at which time the two aircraft would separate, the carrier aircraft returning to base while the other flew on to its destination.

The Short Mayo Composite project, co-designed by Mayo and Shorts chief designer Arthur Gouge, comprised the ''Short S.21 Maia'',Named for Maia, the Greek goddess and mother of Hermes, messenger of the Gods, while Hermes was known to the Romans as Mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

(''G-ADHK'') which was a variant of the Short "C-Class" Empire flying-boat fitted with a trestle or pylon on the top of the fuselage to support the ''Short S.20 Mercury''(''G-ADHJ'').

The first successful in-flight separation of the ''Composite'' was carried out on 6 February 1938, and the first transatlantic flight was made on 21 July 1938 from Foynes to Boucherville

Boucherville is a city in the Montérégie region in Quebec, Canada. It is a suburb of Montreal on the South Shore (Montreal), South shore of the Saint Lawrence River.

Boucherville is part of both the urban agglomeration of Longueuil and Greate ...

. ''Mercury'', piloted by Captain Don Bennett

Air Vice Marshal Donald Clifford Tyndall Bennett, (14 September 1910 – 15 September 1986) was an Australian aviation pioneer and bomber pilot who rose to be the youngest air vice marshal in the Royal Air Force. He led the "Pathfinder Fo ...

, separated from her carrier at 8 pm to continue what was to become the first commercial non-stop east-to-west transatlantic flight by a heavier-than-air machine. This initial journey took 20 hrs, 21 min at an average ground speed of .

Another technology developed for the purpose of transatlantic commercial flight, was aerial refuelling. Sir Alan Cobham developed the ''Grappled-line looped-hose'' system to stimulate the possibility for long-range transoceanic commercial aircraft flights, and publicly demonstrated it for the first time in 1935. In the system the receiver aircraft trailed a steel cable which was then grappled by a line shot from the tanker. The line was then drawn back into the tanker where the receiver's cable was connected to the refueling hose. The receiver could then haul back in its cable bringing the hose to it. Once the hose was connected, the tanker climbed sufficiently above the receiver aircraft to allow the fuel to flow under gravity.

Cobham founded Flight Refuelling Ltd in 1934 and by 1938 had demonstrated the ''FRL's looped-hose'' system to refuel the Short Empire flying boat ''Cambria'' from an Armstrong Whitworth AW.23

The Armstrong Whitworth A.W.23 was a prototype bomber/transport aircraft produced to List of Air Ministry specifications, specification C.26/31 for the United Kingdom, British Air Ministry by Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft. While it was not select ...

. Handley Page Harrows were used in the 1939 trials to aerial refuel the Empire flying boats for regular transatlantic crossings. From 5 August – 1 October 1939, sixteen crossings of the Atlantic were made by Empire flying boats, with 15 crossings using FRL's aerial refueling system. After the 16 crossings more trials were suspended due to the outbreak of World War II.

The Short S.26

The Short S.26 G-class was a large transport flying boat designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Short Brothers. It was designed to achieve a non-stop transatlantic capability, increasing the viability of long distant service ...

was built in 1939 as an enlarged Short Empire, powered by four 1,400 hp (1,044 kW) Bristol Hercules

The Bristol Hercules is a 14-cylinder two-row radial aircraft engine designed by Sir Roy Fedden and produced by the Bristol Engine Company starting in 1939. It was the most numerous of their single sleeve valve ( Burt-McCollum, or Argyll, typ ...

sleeve valve radial engines and designed with the capability of crossing the Atlantic without refuelling. It was intended to form the backbone of Imperial Airways' Empire services. It could fly unburdened, or 150 passengers for a "short hop". On 21 July 1939, the first aircraft, (G-AFCI "Golden Hind"), was first flown at Rochester by Shorts' chief test pilot, John Lankester Parker. Although two aircraft were handed over to Imperial Airways for crew training, all three were impressed (along with their crews) into the RAF before they could begin civilian operation with the onset of World War II.

Meanwhile, Pan Am bought nine

Meanwhile, Pan Am bought nine Boeing 314 Clipper

The Boeing 314 Clipper was an American long-range flying boat produced by Boeing from 1938 to 1941. One of the largest aircraft of its time, it had the range to cross the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. For its wing, Boeing re-used the design fro ...

s in 1939, a long-range flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

capable of flying the Atlantic. The "Clippers" were built for "one-class" luxury air travel, a necessity given the long duration of transoceanic flights. The seats could be converted into 36 bunks for overnight accommodation; with a cruising speed of only . The 314s had a lounge and dining area, and the galleys were crewed by chefs from four-star hotels. Men and women were provided with separate dressing rooms, and white-coated stewards served five and six-course meals with gleaming silver service."British Airways Concorde."''Travel Scholar'', Sound Message, LLC. Retrieved: 19 August 2006. The ''Yankee Clippers inaugural trip across the Atlantic was on 24 June 1939. Its route was from Southampton to Port Washington, New York with intermediate stops at Foynes, Ireland,

Botwood, Newfoundland

Botwood is a town in north-central Newfoundland, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada in Census Division 6. It is located on the west shore of the Bay of Exploits on a natural deep water harbour used by cargo ships and seaplanes throughout the town ...

, and Shediac, New Brunswick. Its first passenger flight was on 9 July, and this continued only until the onset of the Second World War, less than two months later. The ''Clipper'' fleet was then pressed into military service and the flying boats were used for ferrying personnel and equipment to the European

European, or Europeans, or Europeneans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe ...

and Pacific fronts.

In 1938 a Lufthansa Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor long range airliner flew non-stop from Berlin to New York and returned non-stop as a proving flight for the development of passenger carrying services. This was the first landplane to fulfil this function and marked a departure from the British and American reliance on flying boats for long over-water routes. A regular Lufthansa Transatlantic service was planned but didn't begin until after World War II.

Maturation

It was from the emergency exigencies of World War II that crossing the Atlantic by land-based aircraft became a practical and commonplace possibility. With the

It was from the emergency exigencies of World War II that crossing the Atlantic by land-based aircraft became a practical and commonplace possibility. With the Fall of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second World ...

in June 1940, and the loss of much war materiel on the continent, the need for the British to purchase replacement materiel from the United States was urgent. Airbases for refuelling were built in Greenland and Iceland, which were occupied by the United States after the German invasion of Denmark (1940).

The British and United States Government hurried a secret agreement before Britain declared war on Germany in 1939 for the United States to establish a base in Bermuda. Ultimately, the agreement would be expanded to include a United States Naval Operating Base, containing a Naval Air Station serving anti-submarine flying boats, on the Great Sound

The Great Sound is large ocean inlet (a sound) located in Bermuda. It may be the submerged remains of a Pre-Holocene volcanic caldera. Other geologists dispute the origin of the Bermuda Pedestal as a volcanic hotspot.

Geography

The Great Sound d ...

(near to the Royal Naval Dockyard, Bermuda, Royal Naval Air Station Bermuda that had been operated for the Royal Navy with the rest of the Fleet Air Arm at its original location in HM Dockyard Bermuda until 1939 by the Royal Air Force, and the Darrell's Island airport, which was taken over by the Royal Air Force for trans-Atlantic ferrying of flying boats such as the Catalinas, which were flown there from United States factories to be tested prior to acceptance by the Air Ministry and delivery across the Atlantic, usually on direct flights to Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

, Scotland. RAF Transport Command

RAF Transport Command was a Royal Air Force command that controlled all transport aircraft of the RAF. It was established on 25 March 1943 by the renaming of the RAF Ferry Command, and was subsequently renamed RAF Air Support Command in 1967.

...

flights, such as those flown by Coronados, also utilised the facility as BOAC and PAA continued to do) and Kindley Field

Kindley Air Force Base was a United States Air Force base in Bermuda from 1948–1970, having been operated from 1943 to 1948 by the United States Army Air Forces as ''Kindley Field''.

History

World War II

Prior to American entry into th ...

, serving landplanes, constructed by the United states Army for operation by the United States Army Air Forces, but to be used jointly by the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy. In January, 1942, Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

visited Bermuda on his return to Britain, following December 1941 meetings in Washington D.C. with US President Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, in the weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Churchill flew into Darrell's Island on the BOAC Boeing 314 ''Berwick''. Although it had been planned to continue the journey aboard the battleship HMS Duke of York, he made an impulsive decision to complete it by a direct flight from Bermuda to Plymouth, England aboard Berwick, marking the first trans-Atlantic air crossing by a national leader. When the first runway at Kindley Field became operational in 1943, the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm relocated Roc target tugs that had been operating on floats from RNAS Bermuda to the airfield to operate as landplanes, and RAF Transport Command moved its operations there, leaving RAF Ferry Command at Darrell's Island.

The time taken for an aircraft – such as the Lockheed Hudson – bought in the United States, to be flown to Nova Scotia and Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, and then partially dis-assembled before being transported by ship to England, where it was re-assembled and subject to repairs of any damage sustained during shipment, could mean an aircraft could not enter service for several weeks. Further, German U-boats operating in the North Atlantic Ocean made it particularly hazardous for merchant ships between Newfoundland and Britain.

Larger aircraft could be flown directly to the UK and an organization was set up to manage this using civilian pilots. The program was begun by the Ministry of Aircraft Production

Ministry may refer to:

Government

* Ministry (collective executive), the complete body of government ministers under the leadership of a prime minister

* Ministry (government department), a department of a government

Religion

* Christian ...

. Its minister, Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), generally known as Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics o ...

a Canadian by origin, reached an agreement with Sir Edward Beatty, a friend and chairman of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company

Canadian Pacific Limited was created in 1971 to own properties formerly owned by Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), a transportation and mining giant in Canada. In October 2001, CPR completed the corporate spin-offs of each of the remaining business ...

to provide ground facilities and support. Ministry of Aircraft Production

Ministry may refer to:

Government

* Ministry (collective executive), the complete body of government ministers under the leadership of a prime minister

* Ministry (government department), a department of a government

Religion

* Christian ...

would provide civilian crews and management and former RAF officer Don Bennett

Air Vice Marshal Donald Clifford Tyndall Bennett, (14 September 1910 – 15 September 1986) was an Australian aviation pioneer and bomber pilot who rose to be the youngest air vice marshal in the Royal Air Force. He led the "Pathfinder Fo ...

, a specialist in long distance flying and later Air Vice Marshal and commander of the Pathfinder Force, led the first delivery flight in November 1940.Ferrying Aircraft OverseasJuno Beach Centre In 1941, MAP took the operation off CPR to put the whole operation under the Atlantic Ferry Organization ("Atfero") was set up by Morris W. Wilson, a banker in Montreal. Wilson hired civilian pilots to fly the aircraft to the UK. The pilots were then ferried back in converted RAF Liberators. "Atfero hired the pilots, planned the routes, selected the airports ndset up weather and radiocommunication stations."

The organization was passed to Air Ministry administration though retaining civilian pilots, some of which were Americans, alongside RAF navigators and British radio operators. After completing delivery, crews were flown back to Canada for the next run. RAF Ferry Command was formed on 20 July 1941, by the raising of the RAF Atlantic Ferry Service to Command status."RAF Home Commands formed between 1939–1957"

The organization was passed to Air Ministry administration though retaining civilian pilots, some of which were Americans, alongside RAF navigators and British radio operators. After completing delivery, crews were flown back to Canada for the next run. RAF Ferry Command was formed on 20 July 1941, by the raising of the RAF Atlantic Ferry Service to Command status."RAF Home Commands formed between 1939–1957"Air of Authority – A History of RAF Organisation Its commander for its whole existence was

Air Chief Marshal

Air chief marshal (Air Chf Mshl or ACM) is a high-ranking air officer originating from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. An air chief marshal is equivalent to an Admir ...

Sir Frederick Bowhill.

As its name suggests, the main function of Ferry Command was the ferrying of new aircraft from factory to operational unit.''Flying the Secret Sky: The Story of the RAF Ferry Command''Ferry Command did this over only one area of the world, rather than the more general routes that Transport Command later developed. The Command's operational area was the north Atlantic, and its responsibility was to bring the larger aircraft that had the range to do the trip over the ocean from American and Canadian factories to the RAF home Commands. With the entry of the United States into the War, the Atlantic Division of the United States Army Air Forces Air Transport Command began similar ferrying services to transport aircraft, supplies and passengers to the British Isles. By September 1944 British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), as Imperial Airways had by then become, had made 1,000 transatlantic crossings. After World War II long runways were available, and North American and European carriers such as Pan Am,

TWA

Trans World Airlines (TWA) was a major American airline which operated from 1930 until 2001. It was formed as Transcontinental & Western Air to operate a route from New York City to Los Angeles via St. Louis, Kansas City, and other stops, with ...

, Trans Canada Airlines

Trans-Canada Air Lines (also known as TCA in English, and Trans-Canada in French) was a Canadian airline that operated as the country's flag carrier, with corporate headquarters in Montreal, Quebec. Its first president was Gordon McGregor, Go ...

(TCA), BOAC, and Air France acquired larger piston airliners that could cross the North Atlantic with stops (usually in Gander, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

and/or Shannon, Ireland). In January 1946 Pan Am's Douglas DC-4 was scheduled New York ( La Guardia) to London ( Hurn) in 17 hours 40 minutes, five days a week; in June 1946 Lockheed L-049 Constellations had brought the eastward time to London Heathrow down to 15 hr 15 min.

To aid aircraft crossing the Atlantic, six nations grouped to divide the Atlantic into ten zones. Each zone had a letter and a vessels station in that zone, providing radio relay, radio navigation beacons, weather reports and rescues if an aircraft went down. The six nations of the group split the cost of these vessels.

The September 1947 ABC Guide shows 27 passenger flights a week west across the North Atlantic to the US and Canada on BOAC and other European airlines and 151 flights every two weeks on Pan Am, AOA, TWA and TCA, 15 flights a week to the Caribbean and South America, plus three a month on Iberia and a Latécoère 631

The Latécoère 631 was a civil transatlantic flying boat built by Latécoère, the largest ever built up to its time. The type was not a success, being unreliable and uneconomic to operate. Five of the eleven aircraft built were written off in ...

six-engine flying boat every two weeks to Fort de France.

In May 1952, BOAC was the first airline to introduce a

In May 1952, BOAC was the first airline to introduce a passenger jet

A jet airliner or jetliner is an airliner powered by jet engines (passenger jet aircraft). Airliners usually have two or four jet engines; three-engined designs were popular in the 1970s but are less common today. Airliners are commonly clas ...

, the de Havilland Comet, into airline service, operating on routes in Europe and beyond (but not transatlantic). All Comet 1 aircraft were grounded in April 1954 after four Comets crashed, the last two being BOAC aircraft which suffered catastrophic failure at altitude. Later jet airliners, including the larger and longer-range Comet 4, were designed so that in the event of for example a skin-failure due to cracking the damage would be localized and not catastrophic.

On 4 October 1958, BOAC started the "first-ever transatlantic jet service" between London Heathrow and New York Idlewild with a Comet 4, and Pan Am followed on 26 October with a Boeing 707

The Boeing 707 is an American, long-range, narrow-body airliner, the first jetliner developed and produced by Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

Developed from the Boeing 367-80 prototype first flown in 1954, the initial first flew on December 20, ...

service between New York and Paris.

Supersonic flights on the Concorde were offered from 1976 to 2003, from London (by British Airways) and Paris (by Air France) to New York and Washington, and back, with flight times of around three and a half hours one-way. Since the loosening of regulations in the 1970s and 1980s, many airlines now compete across the Atlantic.

Present day

In 2015, 44 million seats were offered on the transatlantic routes, an increase of 6% over the previous year. Of the 67 European airports with links to North America, the busiest was LondonHeathrow Airport

Heathrow Airport (), called ''London Airport'' until 1966 and now known as London Heathrow , is a major international airport in London, England. It is the largest of the six international airports in the London airport system (the others be ...

with 231,532 weekly seats, followed by Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport with 129,831, Frankfurt Airport with 115,420, and Amsterdam Airport Schiphol

Amsterdam Airport Schiphol , known informally as Schiphol Airport ( nl, Luchthaven Schiphol, ), is the main international airport of the Netherlands. It is located southwest of Amsterdam, in the municipality of Haarlemmermeer in the province ...

with 79,611. Of the 45 airports in North America, the busiest linked to Europe was New York John F. Kennedy International Airport with 198,442 seats, followed by Toronto Pearson International Airport with 90,982, New York Newark Liberty International Airport

Newark Liberty International Airport , originally Newark Metropolitan Airport and later Newark International Airport, is an international airport straddling the boundary between the cities of Newark in Essex County and Elizabeth in Union Count ...

with 79,107, and Chicago O'Hare International Airport

Chicago O'Hare International Airport , sometimes referred to as, Chicago O'Hare, or simply O'Hare, is the main international airport serving Chicago, Illinois, located on the city's Northwest Side, approximately northwest of the Chicago Loop, ...

with 75,391 seats.

Joint ventures, allowing coordination on prices, schedules, and strategy, control almost 75% of Transatlantic capacity. They are parallel to airline alliances: British Airways, Iberia and American Airlines are part of Oneworld; Lufthansa

Deutsche Lufthansa AG (), commonly shortened to Lufthansa, is the flag carrier of Germany. When combined with its subsidiaries, it is the second- largest airline in Europe in terms of passengers carried. Lufthansa is one of the five founding m ...

, Air Canada and United Airlines are members of Star Alliance; and Delta Air Lines, Air France, KLM

KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, legally ''Koninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij N.V.'' (literal translation: Royal Aviation Company Plc.), is the flag carrier airline of the Netherlands. KLM is headquartered in Amstelveen, with its hub at nearby Amste ...

and Alitalia belong to SkyTeam

SkyTeam is one of the world's three major airline alliances. Founded in June 2000, SkyTeam was the last of the three alliances to be formed, the first two being Star Alliance and Oneworld, respectively. Its annual passenger count is 630 million ...

. Low cost carriers are starting to compete on this market, most importantly Norwegian Air Shuttle, WestJet and WOW Air. A total of 431 non-stop routes between North America and Europe were scheduled for summer 2017, up 84 routes from 347 in 2012 – a 24% increase.

In 2016 Dr. Paul Williams of the University of Reading published a scientific study showing that transatlantic flight times are expected to change as the North Atlantic jet stream

Jet streams are fast flowing, narrow, meandering thermal wind, air currents in the Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheres of some planets, including Earth. On Earth, the main jet streams are located near the altitude of the tropopause and are west ...

responds to global warming, with eastbound flights speeding up and westbound flights slowing down.

In February 2017, Norwegian Air International announced it would start transatlantic flights to the United States from the United Kingdom and Ireland in summer 2017 on behalf of its parent company using the parent's new Boeing 737 MAX aircraft expected to be delivered from May 2017.

Norwegian Air performed its first transatlantic flight with a Boeing 737-800 on 16 June 2017 between Edinburgh Airport and Stewart Airport, New York

Stewart International Airport, officially New York Stewart International Airport , is a public/military airport in Orange County, New York, United States. It is in the southern Hudson Valley, west of Newburgh, south of Kingston, and southwest ...

.

The first transatlantic flight with a 737 MAX was performed on 15 July 2017, with a MAX 8 named ''Sir Freddie Laker'', between Edinburgh Airport in Scotland and Hartford International Airport

Bradley International Airport is a public international airport in Windsor Locks, Connecticut, United States. Owned and operated by the Connecticut Airport Authority, it is the second-largest airport in New England.

The airport is about halfw ...

in the US state of Connecticut, followed by a second rotation from Edinburgh to Stewart Airport, New York

Stewart International Airport, officially New York Stewart International Airport , is a public/military airport in Orange County, New York, United States. It is in the southern Hudson Valley, west of Newburgh, south of Kingston, and southwest ...

.

Long-haul low-cost carrier

A low-cost carrier or low-cost airline (occasionally referred to as '' no-frills'', ''budget'' or '' discount carrier'' or ''airline'', and abbreviated as ''LCC'') is an airline that is operated with an especially high emphasis on minimizing op ...

s are emerging on the transatlantic market with 545,000 seats offered over 60 city pairs in September 2017 (a 66% growth over one year), compared to 652,000 seats over 96 pairs for leisure airlines and 8,798,000 seats over 357 pairs for mainline carriers.

LCC seat grew to 7.7% of North Atlantic seats in 2018 from 3.0% in 2016, led by Norwegian with 4.8% then WOW air with 1.6% and WestJet with 0.6%, while the three airline alliances dedicated joint ventures seat share is 72.3%, down from 79.8% in 2015.

By July 2018, Norwegian became the largest European airline for New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, carrying 1.67 million passengers over a year, beating British Airways's 1.63 million, while the U.S. major carriers combined transported 26.1 million transatlantic passengers.

Transatlantic routes

Unlike over land, transatlantic flights use standardized aircraft routes called North Atlantic Tracks (NATs). These change daily in position (although altitudes are standardized) to compensate for weather—particularly thejet stream

Jet streams are fast flowing, narrow, meandering thermal wind, air currents in the Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheres of some planets, including Earth. On Earth, the main jet streams are located near the altitude of the tropopause and are west ...

tailwinds and headwinds, which may be substantial at cruising altitudes and have a strong influence on trip duration and fuel economy. Eastbound flights generally operate during night-time hours, while westbound flights generally operate during daytime hours, for passenger convenience. The eastbound flow, as it is called, generally makes European landfall from about 0600UT to 0900UT. The westbound flow generally operates within a 1200–1500UT time slot. Restrictions on how far a given aircraft may be from an airport also play a part in determining its route; in the past, airliners with three or more engines were not restricted, but a twin-engine airliner was required to stay within a certain distance of airports that could accommodate it (since a single engine failure in a four-engine aircraft is less crippling than a single engine failure in a twin). Modern aircraft with two engines flying transatlantic (the most common models used for transatlantic service being the Airbus A330, Boeing 767

The Boeing 767 is an American wide-body aircraft developed and manufactured by Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

The aircraft was launched as the 7X7 program on July 14, 1978, the prototype first flew on September 26, 1981, and it was certified on ...

, Boeing 777 and Boeing 787) have to be ETOPS certified.

Gaps in air traffic control and radar coverage over large stretches of the Earth's oceans, as well as an absence of most types of radio navigation aids, impose a requirement for a high level of autonomy in navigation upon transatlantic flights. Aircraft must include reliable systems that can determine the aircraft's course and position with great accuracy over long distances. In addition to the traditional compass, inertials and satellite navigation systems such as GPS

The Global Positioning System (GPS), originally Navstar GPS, is a Radionavigation-satellite service, satellite-based radionavigation system owned by the United States government and operated by the United States Space Force. It is one of t ...

all have their place in transatlantic navigation. Land-based systems such as VOR

VOR or vor may refer to:

Organizations

* Vale of Rheidol Railway in Wales

* Voice of Russia, a radio broadcaster

* Volvo Ocean Race, a yacht race

Science, technology and medicine

* VHF omnidirectional range, a radio navigation aid used in a ...

and DME, because they operate "line of sight", are mostly useless for ocean crossings, except in initial and final legs within about of those facilities. In the late 1950s and early 1960s an important facility for low-flying aircraft was the Radio Range. Inertial navigation systems became prominent in the 1970s.

Busiest transatlantic routes

The twenty busiest commercial routes between North America and Europe (traffic traveling in both directions) in 2010 were:Notable transatlantic flights and attempts

1910s

;Airship America failure: In October 1910, the American journalist Walter Wellman, who had in 1909 attempted to reach the North Pole by balloon, set out for Europe fromAtlantic City

Atlantic City, often known by its initials A.C., is a coastal resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States. The city is known for its casinos, Boardwalk (entertainment district), boardwalk, and beaches. In 2020 United States censu ...

in a dirigible

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

, ''America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

''. A storm off Cape Cod sent him off course, and then engine failure forced him to ditch halfway between New York and Bermuda. Wellman, his crew of five – and the balloon's cat – were rescued by RMS Trent, a passing British ship. The Atlantic bid failed, but the distance covered, about , was at the time a record for a dirigible.

;First transatlantic flight: On 8–31 May 1919, the U.S. Navy Curtiss NC-4

;First transatlantic flight: On 8–31 May 1919, the U.S. Navy Curtiss NC-4 flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

under the command of Albert Read, flew from Rockaway, New York, to Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

( England), ''via'' among other stops Trepassey

Trepassey () is a small fishing community located in Trepassey Bay on the south eastern corner of the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland and Labrador. It was in Trepassey Harbour where the flight of the ''Friendship'' took off, with Amelia Earhart ...

(Newfoundland), Horta

Horta may refer to:

People

* Horta (surname), a list of people

Places

* Horta, Africa, an ancient city and former bishopric in Africa Proconsularis, now in Tunisia and a Latin Catholic titular see

* Horta, Azores, Portugal, a municipality an ...

and Ponta Delgada (both Azores) and Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

( Portugal) in 53h 58m, spread over 23 days. The crossing from Newfoundland to the European mainland had taken 10 days 22 hours, with the total time in flight of 26h 46m. The longest non-stop leg of the journey, from Trepassey, Newfoundland, to Horta in the Azores, was and lasted 15h 18m.

;Sopwith Atlantic failure: On 18 May 1919, the Australian Harry Hawker

Harry George Hawker, MBE, AFC (22 January 1889 – 12 July 1921) was an Australian aviation pioneer. He was the chief test pilot for Sopwith and was also involved in the design of many of their aircraft. After the First World War, he co-fou ...

, together with navigator Kenneth Mackenzie Grieve

Kenneth is an English language, English given name and surname. The name is an Anglicised form of two entirely different Gaelic personal names: ''Cainnech'' and ''Cináed (disambiguation), Cináed''. The modern Scottish Gaelic, Gaelic form of ''C ...

, attempted to become the first to achieve a non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean. They set off from Mount Pearl

Mount Pearl is the third-largest settlement and second-largest city in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. The city is located southwest of St. John's, on the eastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland. Mount Pearl is the fo ...

, Newfoundland, in the Sopwith Atlantic

The Sopwith Atlantic was an experimental British long-range aircraft of 1919. It was a single-engined biplane that was designed and built to be the first aeroplane to cross the Atlantic Ocean non-stop. It took off on an attempt to cross the A ...

biplane. After fourteen and a half hours of flight the engine overheated and they were forced to divert towards the shipping lanes: they found a passing freighter, the Danish ''Mary'', established contact and crash-landed ahead of her. ''Mary's'' radio was out of order, so that it was not until six days later when the boat reached Scotland that word was received that they were safe. The wheels from the undercarriage, jettisoned soon after takeoff, were later recovered by local fishermen and are now in the Newfoundland Museum in St. John's.Kev Darling: ''Hawker Typhoon, Tempest and Sea Fury''. The Crowood Press, 2003. . p.8

; First non-stop transatlantic flight: On 14–15 June 1919, Capt. John Alcock and Lieut. Arthur Whitten Brown of the United Kingdom in Vickers Vimy bomber, between islands, , from St. John's, Newfoundland

St. John's is the capital and largest city of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, located on the eastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland.

The city spans and is the easternmost city in North America ...

, to Clifden, Ireland, in 16h 12m.

;First east-to-west transatlantic flight: On 2 July 1919, Major George Herbert Scott

Major George Herbert "Lucky Breeze" Scott, CBE, AFC, (25 May 1888 – 5 October 1930) was a British airship pilot and engineer. After serving in the Royal Naval Air Service and Royal Air Force during World War I, Scott went on to command the ai ...

of the Royal Air Force with his crew and passengers flies from RAF East Fortune, Scotland to Mineola, New York (on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

) in airship ''R34'', covering a distance of about in about four and a half days. ''R34'' then made the return trip to England arriving at RNAS Pulham in 75 hours, thus also completing the first double crossing of the Atlantic (east-west-east).

1920s

; First flight across the South Atlantic: On 30 March–17 June 1922, Lieutenant Commander Sacadura Cabral and CommanderGago Coutinho

Carlos Viegas Gago Coutinho, GCTE, GCC, generally known simply as Gago Coutinho (; 17 February 1869 – 18 February 1959) was a Portuguese geographer, cartographer, naval officer, historian and aviator. An aviation pioneer, Gago Coutinho and Sac ...

of Portugal, using three Fairey IIID floatplanes (''Lusitania'', ''Portugal'', and ''Santa Cruz''), after two ditchings, with only internal means of navigation (the Coutinho-invented sextant with artificial horizon) from Lisbon, Portugal, to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

; First non-stop aircraft flight between European and American mainlands: On 12 October 1924, the Zeppelin '' LZ-126'' (later known as ''ZR-3'' ''USS Los Angeles''), began an 81-hour flight from Germany to New Jersey with a crew commanded by Dr. Hugo Eckener, covering a distance of .

; First night-time flight across the Atlantic: On the night of 16–17 April 1927, the Portuguese aviators Sarmento de Beires, Jorge de Castilho and Manuel Gouveia, flew from the Bijagós islands, Portuguese Guinea to Fernando de Noronha island, Brazil in the Dornier Wal flying boat ''Argos''.

; First flight across the South Atlantic made by a non-European crew: On 28 April 1927, Brazilian João Ribeiro de Barros

João Ribeiro de Barros (4 April 1900 – 20 July 1947) was the first aviator of the three Americas to make an air crossing from Europe to America, on April 28, 1927, crossing the Atlantic Ocean with the Savoia-Marchetti S.55 hydroplane ...

, with the assistance of João Negrão (co-pilot), Newton Braga (navigator), and Vasco Cinquini (mechanic), crossed the Atlantic in the hydroplane ''Jahú''. The four aviators flew from Genoa, in Italy, to Santo Amaro (São Paulo)

Santo Amaro, Portuguese for "Saint Amaro", may refer to the following places:

Brazil

* Santo Amaro, Bahia

*Santo Amaro da Imperatriz, Santa Catarina

*Santo Amaro das Brotas, Sergipe

*Santo Amaro do Maranhão, Maranhão

* Santo Amaro, a district ...

, making stops in Spain, Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, Cape Verde

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

and Fernando de Noronha, in the Brazilian territory.

; Disappearance of ''L'Oiseau Blanc'': On 8–9 May 1927, Charles Nungesser

Charles Eugène Jules Marie Nungesser (15 March 1892 – presumably on or after 8 May 1927) was a French ace pilot and adventurer. Nungesser was a renowned ace in France, ranking third highest in the country with 43 air combat victories during Wo ...

and François Coli