Stravinsky, Igor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

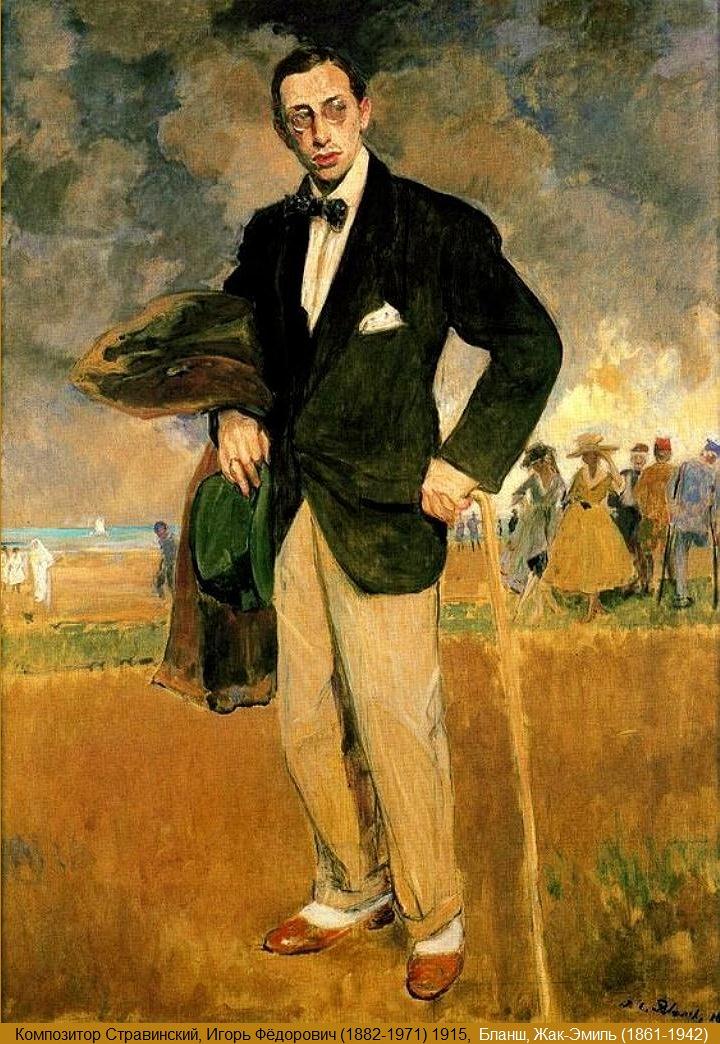

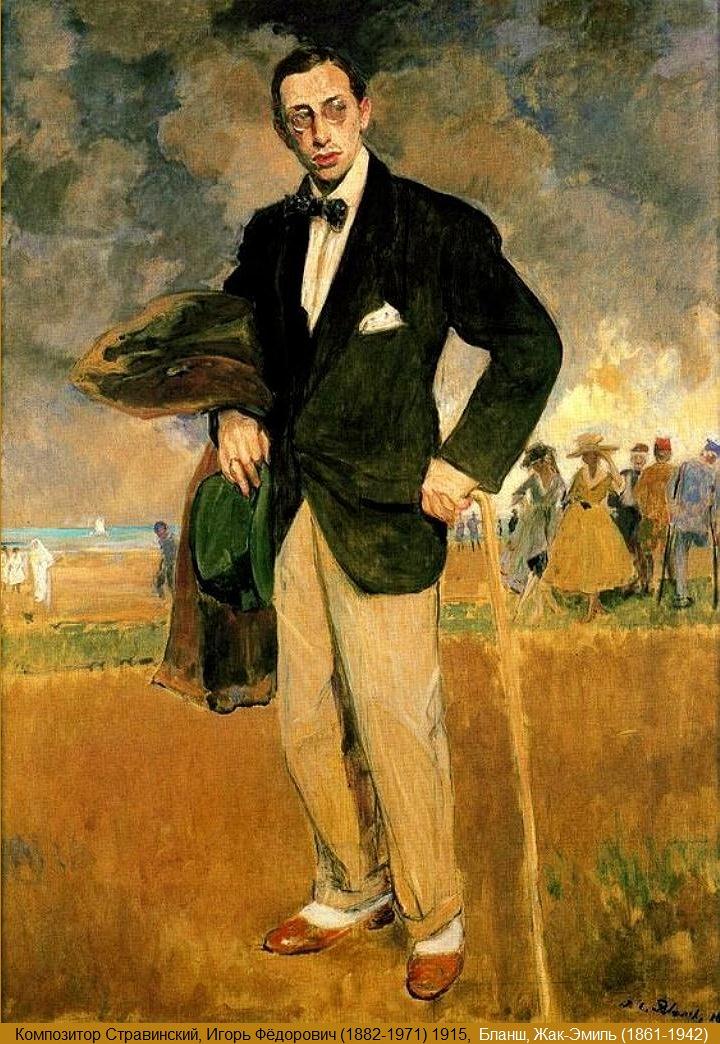

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century and a pivotal figure in

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century and a pivotal figure in

On 10 August 1882, Stravinsky was baptised at Nikolsky Cathedral in Saint Petersburg. Until 1914, he spent most of his summers in the town of

On 10 August 1882, Stravinsky was baptised at Nikolsky Cathedral in Saint Petersburg. Until 1914, he spent most of his summers in the town of

Despite Stravinsky's enthusiasm and ability in music, his parents expected him to study law, and he at first took to the subject. In 1901, he enrolled at the

Despite Stravinsky's enthusiasm and ability in music, his parents expected him to study law, and he at first took to the subject. In 1901, he enrolled at the

By 1909, Stravinsky had composed two more pieces, ''

By 1909, Stravinsky had composed two more pieces, '' In April 1914, Stravinsky and his family returned to Clarens. Following the outbreak of

In April 1914, Stravinsky and his family returned to Clarens. Following the outbreak of

Stravinsky met

Stravinsky met

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century and a pivotal figure in

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century and a pivotal figure in modernist music

In music, modernism is an aesthetic stance underlying the period of change and development in musical language that occurred around the turn of the 20th century, a period of diverse reactions in challenging and reinterpreting older categories o ...

.

Stravinsky's compositional career was notable for its stylistic diversity. He first achieved international fame with three ballets commissioned by the impresario

An impresario (from the Italian ''impresa'', "an enterprise or undertaking") is a person who organizes and often finances concerts, plays, or operas, performing a role in stage arts that is similar to that of a film or television producer.

Hist ...

Sergei Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev ( ; rus, Серге́й Па́влович Дя́гилев, , sʲɪˈrɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪdʑ ˈdʲæɡʲɪlʲɪf; 19 August 1929), usually referred to outside Russia as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic, pat ...

and first performed in Paris by Diaghilev's Ballets Russes

The Ballets Russes () was an itinerant ballet company begun in Paris that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. The company never performed in Russia, where the Revolution disrupted society. A ...

: ''The Firebird

''The Firebird'' (french: L'Oiseau de feu, link=no; russian: Жар-птица, Zhar-ptitsa, link=no) is a ballet and orchestral concert work by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. It was written for the 1910 Paris season of Sergei Diaghilev's ...

'' (1910), ''Petrushka

Petrushka ( rus, Петру́шка, p=pʲɪtˈruʂkə, a=Ru-петрушка.ogg) is a stock character of Russian folk puppetry. Italian puppeteers introduced it in the first third of the 19th century. While most core characters came from Italy ...

'' (1911), and ''The Rite of Spring

''The Rite of Spring''. Full name: ''The Rite of Spring: Pictures from Pagan Russia in Two Parts'' (french: Le Sacre du printemps: tableaux de la Russie païenne en deux parties) (french: Le Sacre du printemps, link=no) is a ballet and orchestral ...

'' (1913). The last transformed the way in which subsequent composers thought about rhythmic structure and was largely responsible for Stravinsky's enduring reputation as a revolutionary who pushed the boundaries of musical design. His "Russian phase", which continued with works such as '' Renard'', ''L'Histoire du soldat

' (''The Soldier's Tale'') is a theatrical work "to be read, played, and danced" () by three actors and one or several dancers, accompanied by a septet of instruments. Conceived by Igor Stravinsky and Swiss writer C. F. Ramuz, the piece was bas ...

,'' and ''Les noces

''Les Noces'' (French for The Wedding; russian: Свадебка, ''Svadebka'') is a ballet and orchestral concert work composed by Igor Stravinsky for percussion, pianists, chorus, and vocal soloists. The composer gave it the descriptive title " ...

'', was followed in the 1920s by a period in which he turned to neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism was ...

. The works from this period tended to make use of traditional musical forms (concerto grosso The concerto grosso (; Italian for ''big concert(o)'', plural ''concerti grossi'' ) is a form of baroque music in which the musical material is passed between a small group of soloists (the '' concertino'') and full orchestra (the ''ripieno'', ''tut ...

, fugue

In music, a fugue () is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the c ...

, and symphony

A symphony is an extended musical composition in Western classical music, most often for orchestra. Although the term has had many meanings from its origins in the ancient Greek era, by the late 18th century the word had taken on the meaning com ...

) and drew from earlier styles, especially those of the 18th century. In the 1950s, Stravinsky adopted serial procedures. His compositions of this period shared traits with examples of his earlier output: rhythmic energy, the construction of extended melodic ideas out of a few two- or three-note cells, and clarity of form

Form is the shape, visual appearance, or configuration of an object. In a wider sense, the form is the way something happens.

Form also refers to:

*Form (document), a document (printed or electronic) with spaces in which to write or enter data

...

and instrumentation

Instrumentation a collective term for measuring instruments that are used for indicating, measuring and recording physical quantities. The term has its origins in the art and science of scientific instrument-making.

Instrumentation can refer to ...

.

Biography

Early life, 1882–1901

Stravinsky was born on 17 June 1882 in the town of Oranienbaum on the southern coast of theGulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland ( fi, Suomenlahti; et, Soome laht; rus, Фи́нский зали́в, r=Finskiy zaliv, p=ˈfʲinskʲɪj zɐˈlʲif; sv, Finska viken) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and E ...

, west of Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. His father, Fyodor Ignatievich Stravinsky (1843–1902), was an established bass opera singer in the Kiev Opera

The Kyiv Opera group was formally established in the summer of 1867, and is the third oldest in Ukraine, after Odessa Opera and Lviv Opera.

The Kyiv Opera Company perform at the National Opera House of Ukraine named after Taras Shevchenko in ...

and the Mariinsky Theatre

The Mariinsky Theatre ( rus, Мариинский театр, Mariinskiy teatr, also transcribed as Maryinsky or Mariyinsky) is a historic theatre of opera and ballet in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Opened in 1860, it became the preeminent music th ...

in Saint Petersburg and his mother, Anna Kirillovna Stravinskaya (''née'' Kholodovskaya; 1854–1939), a native of Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

, was one of four daughters of a high-ranking official in the Kiev Ministry of Estates. Igor was the third of their four sons; his brothers were Roman, Yury, and Gury. The Stravinsky family was of Polish and Russian heritage, descended "from a long line of Polish grandees, senators and landowners". It is traceable to the 17th and 18th centuries to the bearers of the Sulima and Strawiński coat of arms. The original family surname was Sulima-Strawiński; the name "Stravinsky" originated from the word "Strava", one of the variants of the Streva River in Lithuania.

On 10 August 1882, Stravinsky was baptised at Nikolsky Cathedral in Saint Petersburg. Until 1914, he spent most of his summers in the town of

On 10 August 1882, Stravinsky was baptised at Nikolsky Cathedral in Saint Petersburg. Until 1914, he spent most of his summers in the town of Ustilug

Ustylúh (, , yi, אוסטילע ''Ustile'') is a town in Volodymyr Raion, Volyn Oblast, Ukraine. It is situated on the east side of the Ukrainian-Polish border, and 8 miles (13 km) west of Volodymyr (city), Volodymyr. Population:

Igor Str ...

, now in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, where his father-in-law owned an estate. Stravinsky's first school was The Second Saint Petersburg Gymnasium, where he stayed until his mid-teens. Then he moved to Gourevitch Gymnasium, a private school, where he studied history, mathematics, and languages (Latin, Greek, and Slavonic; and French, German, and his native Russian). Stravinsky expressed his general distaste for schooling and recalled being a lonely pupil: "I never came across anyone who had any real attraction for me."

Stravinsky took to music at an early age and began regular piano lessons at age nine, followed by tuition in music theory and composition. At around eight years old, he attended a performance of Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

's ballet '' The Sleeping Beauty'' at the Mariinsky Theatre, which began a lifelong interest in ballets and the composer himself. By age fifteen, Stravinsky had mastered Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic music, Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositi ...

's Piano Concerto No. 1 and finished a piano reduction of a string quartet by Alexander Glazunov

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov; ger, Glasunow (, 10 August 1865 – 21 March 1936) was a Russian composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Russian Romantic period. He was director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 1905 ...

, who reportedly considered Stravinsky unmusical and thought little of his skills.

Education and first compositions, 1901–1909

Despite Stravinsky's enthusiasm and ability in music, his parents expected him to study law, and he at first took to the subject. In 1901, he enrolled at the

Despite Stravinsky's enthusiasm and ability in music, his parents expected him to study law, and he at first took to the subject. In 1901, he enrolled at the University of Saint Petersburg

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, the ...

, studying criminal law and legal philosophy, but attendance at lectures was optional and he estimated that he turned up to fewer than fifty classes in his four years of study. In 1902, Stravinsky met Vladimir, a fellow student at the University of Saint Petersburg and the youngest son of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ. la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsk ...

. Rimsky-Korsakov at that time was arguably the leading Russian composer, and he was a professor at Saint Petersburg Conservatory of Music. Stravinsky wished to meet Vladimir's father to discuss his musical aspirations. He spent the summer of 1902 with Rimsky-Korsakov and his family in Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: ''Heidlberg'') is a city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914 ...

, Germany. Rimsky-Korsakov suggested to Stravinsky that he should not enter the Saint Petersburg Conservatory but continue private lessons in theory.

By the time of his father's death from cancer in 1902, Stravinsky was spending more time studying music than law. His decision to pursue music full time was helped when the university was closed for two months in 1905 in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence aga ...

, which prevented him from taking his final law exams. In April 1906, Stravinsky received a half-course diploma and concentrated on music thereafter. In 1905, he began studying with Rimsky-Korsakov twice a week and came to regard him as a second father. These lessons continued until Rimsky-Korsakov's death in 1908. Stravinsky completed his first composition during this time, the Symphony in E-flat, catalogued as Opus 1. In the wake of Rimsky-Korsakov's death, Stravinsky composed '' Funeral Song'', Op. 5 which was performed once and then considered lost until its re-discovery in 2015.

In August 1905, Stravinsky became engaged to his first cousin, Katherina Gavrylovna Nosenko. In spite of the Orthodox Church

Orthodox Church may refer to:

* Eastern Orthodox Church

* Oriental Orthodox Churches

* Orthodox Presbyterian Church

* Orthodox Presbyterian Church of New Zealand

* State church of the Roman Empire

* True Orthodox church

See also

* Orthodox (di ...

's opposition to marriage between first cousins, the couple married on 23 January 1906. They lived in the family's residence at 6 Kryukov Canal in Saint Petersburg before they moved into a new home in Ustilug, which Stravinsky designed and built, and which he later called his "heavenly place". He wrote many of his first compositions there. It is now a museum with documents, letters, and photographs on display, and an annual Stravinsky Festival takes place in the nearby town of Lutsk

Lutsk ( uk, Луцьк, translit=Lutsk}, ; pl, Łuck ; yi, לוצק, Lutzk) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Volyn Oblast (province) and the administrative center of the surrounding Luts ...

. Stravinsky and Nosenko's first two children, Fyodor

Fyodor, Fedor (russian: Фёдор) or Feodor is the Russian form of the name "Theodore (given name), Theodore" meaning “God’s Gift”. Fedora () is the feminine form. Fyodor and Fedor are two English transliterations of the same Russian name. ...

(Theodore) and Ludmila, were born in 1907 and 1908, respectively.

Ballets for Diaghilev and international fame, 1909–1920

By 1909, Stravinsky had composed two more pieces, ''

By 1909, Stravinsky had composed two more pieces, ''Scherzo fantastique

''Scherzo fantastique'', op. 3, composed in 1908, is the second purely orchestral work by Igor Stravinsky (preceded by the Symphony in E-flat op.1). Despite the composer's later description of the work as "a piece of 'pure', symphonic music", the ...

'', Op. 3, and ''Feu d'artifice

''Feu d'artifice'', Op. 4 (''Fireworks'', russian: Фейерверк, ) is a composition by Igor Stravinsky, written in 1908 and described by the composer as a "short orchestral fantasy." It usually takes less than four minutes to perform.

C ...

'' ("Fireworks"), Op. 4. In February of that year, both were performed in Saint Petersburg at a concert that marked a turning point in Stravinsky's career. In the audience was Sergei Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev ( ; rus, Серге́й Па́влович Дя́гилев, , sʲɪˈrɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪdʑ ˈdʲæɡʲɪlʲɪf; 19 August 1929), usually referred to outside Russia as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic, pat ...

, a Russian impresario and owner of the Ballets Russes

The Ballets Russes () was an itinerant ballet company begun in Paris that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. The company never performed in Russia, where the Revolution disrupted society. A ...

who was struck with Stravinsky's compositions. He wished to stage a mix of Russian opera and ballet for the 1910 season in Paris, among them a new ballet from fresh talent that was based on the Russian fairytale of the Firebird

Firebird and fire bird may refer to:

Mythical birds

* Phoenix (mythology), sacred firebird found in the mythologies of many cultures

* Bennu, Egyptian firebird

* Huma bird, Persian firebird

* Firebird (Slavic folklore)

Bird species

''Various sp ...

. After Anatoly Lyadov

Anatoly Konstantinovich Lyadov (russian: Анато́лий Константи́нович Ля́дов; ) was a Russian composer, teacher, and conductor (music), conductor.

Biography

Lyadov was born in 1855 in Saint Petersburg, St. Petersbur ...

was given the task of composing the score, he informed Diaghilev that he needed about one year to complete it. Diaghilev then asked the 28-year-old Stravinsky, who had provided satisfactory orchestrations for him for the previous season at short notice and agreed to compose a full score. At about 50 minutes in length, ''The Firebird

''The Firebird'' (french: L'Oiseau de feu, link=no; russian: Жар-птица, Zhar-ptitsa, link=no) is a ballet and orchestral concert work by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. It was written for the 1910 Paris season of Sergei Diaghilev's ...

'' was revised by Stravinsky for concert performance in 1911, 1919, and 1945.

''The Firebird'' premiered at the Opera de Paris

The Paris Opera (, ) is the primary opera and ballet company of France. It was founded in 1669 by Louis XIV as the , and shortly thereafter was placed under the leadership of Jean-Baptiste Lully and officially renamed the , but continued to be ...

on 25 June 1910 to widespread critical acclaim and Stravinsky became an overnight sensation. As his wife was expecting their third child, the Stravinskys spent the summer in La Baule

La Baule-Escoublac (; br, Ar Baol-Skoubleg, ), commonly referred to as La Baule, is a communes of France, commune in the Loire-Atlantique departments of France, department, Pays de la Loire, western France.

A century-old seaside resort in southe ...

in western France. In September, they moved to Clarens, Switzerland where their second son, Sviatoslav

Sviatoslav (russian: Святосла́в, Svjatosláv, ; uk, Святосла́в, Svjatosláv, ) is a Russian and Ukrainian given name of Slavic origin. Cognates include Svetoslav, Svatoslav, , Svetislav. It has a Pre-Christian pagan charact ...

(Soulima), was born. The family would spend their summers in Russia and winters in Switzerland until 1914. Diaghilev commissioned Stravinsky to score a second ballet for the 1911 Paris season. The result was ''Petrushka

Petrushka ( rus, Петру́шка, p=pʲɪtˈruʂkə, a=Ru-петрушка.ogg) is a stock character of Russian folk puppetry. Italian puppeteers introduced it in the first third of the 19th century. While most core characters came from Italy ...

'', based the Russian folk tale featuring the titular character

The title character in a narrative work is one who is named or referred to in the title of the work. In a performed work such as a play or film, the performer who plays the title character is said to have the title role of the piece. The title of ...

, a puppet, who falls in love with another, a ballerina. Though it failed to capture the immediate reception that ''The Firebird'' had following its premiere at Théâtre du Châtelet

The Théâtre du Châtelet () is a theatre and opera house, located in the place du Châtelet in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France.

One of two theatres (the other being the Théâtre de la Ville) built on the site of a ''châtelet'', a s ...

in June 1911, the production continued Stravinsky's success.

It was Stravinsky's third ballet for Diaghilev, ''The Rite of Spring

''The Rite of Spring''. Full name: ''The Rite of Spring: Pictures from Pagan Russia in Two Parts'' (french: Le Sacre du printemps: tableaux de la Russie païenne en deux parties) (french: Le Sacre du printemps, link=no) is a ballet and orchestral ...

'', that caused a sensation among critics, fellow composers, and concertgoers. Based on an original idea offered to Stravinsky by Nicholas Roerich, the production features a series of primitive rituals celebrating the advent of spring, after which a young girl is chosen as a sacrificial victim to the sun god Yarilo, and dances herself to death. Stravinsky's score contained many novel features for its time, including experiments in tonality, metre, rhythm, stress and dissonance. The radical nature of the music and choreography caused a near-riot at its premiere at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées () is an entertainment venue standing at 15 avenue Montaigne in Paris. It is situated near Avenue des Champs-Élysées, from which it takes its name. Its eponymous main hall may seat up to 1,905 people, while th ...

on 29 May 1913.

Shortly after the premiere, Stravinsky contracted typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

from eating bad oysters and he was confined to a Paris nursing home. He left in July 1913 and returned to Ustilug. For the rest of the summer he focused on his first opera, '' The Nightingale'' (''Le Rossignol''), based on the same-titled story by Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen ( , ; 2 April 1805 – 4 August 1875) was a Danish author. Although a prolific writer of plays, travelogues, novels, and poems, he is best remembered for his literary fairy tales.

Andersen's fairy tales, consisti ...

, which he had started in 1908. On 15 January 1914, Stravinsky and Nosenko had their fourth child, Marie Milène (or Maria Milena). After her delivery, Nosenko was discovered to have tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

and was confined to a sanatorium

A sanatorium (from Latin '' sānāre'' 'to heal, make healthy'), also sanitarium or sanitorium, are antiquated names for specialised hospitals, for the treatment of specific diseases, related ailments and convalescence. Sanatoriums are often ...

in Leysin

Leysin is a municipality of the canton of Vaud in the Aigle district of Switzerland. It is first mentioned around 1231–32 as ''Leissins'', in 1352 as ''Leisins''.

Located in the Vaud Alps, Leysin is a sunny alpine resort village at the easter ...

in the Alps. Stravinsky took up residence nearby, where he completed ''The Nightingale''. The work premiered in Paris in May 1914, after the Moscow Free Theatre had commissioned the piece for 10,000 rubles but soon became bankrupt. Diaghilev agreed for the Ballets Russes to stage it. The opera had only lukewarm success with the public and the critics, apparently because its delicacy did not meet their expectations following the tumultuous ''Rite of Spring''. However, composers including Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism in music, Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composer ...

, Bartók, and Reynaldo Hahn

Reynaldo Hahn (; 9 August 1874 – 28 January 1947) was a Venezuelan-born French composer, conductor, music critic, and singer. He is best known for his songs – ''mélodies'' – of which he wrote more than 100.

Hahn was born in Caracas b ...

found much to admire in the score's craftsmanship, even alleging to detect the influence of Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

.

In April 1914, Stravinsky and his family returned to Clarens. Following the outbreak of

In April 1914, Stravinsky and his family returned to Clarens. Following the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

later that year, he was ineligible for military service due to health reasons. Stravinsky managed a short visit to Ustilug to retrieve personal items just before national borders were closed. In June 1915, he and his family moved from Clarens to Morges

Morges (; la, Morgiis, plural, probably ablative, else dative; frp, Môrges) is a municipality in the Swiss canton of Vaud and the seat of the district of Morges. It is located on Lake Geneva.

History

Morges is first mentioned in 1288 as ' ...

, a town six miles from Lausanne on the shore of Lake Geneva

, image = Lake Geneva by Sentinel-2.jpg

, caption = Satellite image

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = Switzerland, France

, coords =

, lake_type = Glacial lak ...

. The family lived there (at three different addresses), until 1920. In December 1915, Stravinsky made his conducting debut at two concerts in aid of the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

with ''The Firebird''. The war and subsequent Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

in 1917 made it impossible for Stravinsky to return to his homeland.

Stravinsky began to struggle financially in the late 1910s as Russia (and its successor, the USSR) did not adhere to the Berne Convention

The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, usually known as the Berne Convention, was an international assembly held in 1886 in the Swiss city of Bern by ten European countries with the goal to agree on a set of leg ...

, thus creating problems for Stravinsky to collect royalties for the performances of his pieces for the Ballets Russes. He blamed Diaghilev for his financial troubles, accusing the impresario of failing to adhere to their contract. While composing his theatrical piece ''L'Histoire du soldat

' (''The Soldier's Tale'') is a theatrical work "to be read, played, and danced" () by three actors and one or several dancers, accompanied by a septet of instruments. Conceived by Igor Stravinsky and Swiss writer C. F. Ramuz, the piece was bas ...

'' (''The Soldier's Tale''), Stravinsky approached Swiss philanthropist Werner Reinhart Werner Reinhart (19 March 1884 – 29 August 1951) was a Swiss merchant, philanthropist, amateur clarinetist, and patron of composers and writers, particularly Igor Stravinsky and Rainer Maria Rilke. Reinhart knew and corresponded with many artist ...

for financial assistance, who agreed to sponsor him and largely underwrite its first performance which took place in Lausanne in September 1918. In gratitude, Stravinsky dedicated the work to Reinhart and gave him the original manuscript. Reinhart supported Stravinsky further when he funded a series of concerts of his chamber music in 1919. In gratitude to his benefactor, Stravinsky also dedicated his ''Three Pieces for Clarinet'' to Reinhart, who was also an amateur clarinetist.

Following the premiere of ''Pulcinella

Pulcinella (; nap, Pulecenella) is a classical character that originated in of the 17th century and became a stock character in Neapolitan puppetry. Pulcinella's versatility in status and attitude has captivated audiences worldwide and kept t ...

'' by the Ballets Russes in Paris on 15 May 1920, Stravinsky returned to Switzerland.

Life in France, 1920–1939

In June 1920, Stravinsky and his family left Switzerland for France, first settling inCarantec

Carantec (; br, Karanteg) is a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany in north-western France.

Carantec is located on the coast of the English Channel. It contains a small island within its boundaries, Île Callot, which can be reache ...

, Brittany for the summer while they sought a permanent home in Paris. They soon heard from couturière Coco Chanel

Gabrielle Bonheur "Coco" Chanel ( , ; 19 August 1883 – 10 January 1971) was a French fashion designer and businesswoman. The founder and namesake of the Chanel brand, she was credited in the post-World War I era with popularizing a sporty, c ...

, who invited the family to live in her Paris mansion until they had found their own residence. The Stravinskys accepted and arrived in September. Chanel helped secure a guarantee for a revival production of ''The Rite of Spring'' by the Ballets Russes from December 1920 with an anonymous gift to Diaghilev that was claimed to be worth 300,000 francs.

In 1920, Stravinsky signed a contract with the French piano manufacturing company Pleyel

Ignace Joseph Pleyel (; ; 18 June 1757 – 14 November 1831) was an Austrian-born French composer, music publisher and piano builder of the Classical period.

Life Early years

He was born in in Lower Austria, the son of a schoolmaster named Ma ...

. As part of the deal, Stravinsky transcribed most of his compositions for their player piano

A player piano (also known as a pianola) is a self-playing piano containing a pneumatic or electro-mechanical mechanism, that operates the piano action via programmed music recorded on perforated paper or metallic rolls, with more modern i ...

, the Pleyela. The company helped collect Stravinsky's mechanical royalties for his works and provided him with a monthly income. In 1921, he was given studio space at their Paris headquarters where he worked and entertained friends and acquaintances. The piano rolls were not recorded, but were instead marked up from a combination of manuscript fragments and handwritten notes by Jacques Larmanjat, musical director of Pleyel's roll department. During the 1920s, Stravinsky recorded Duo-Art

Duo-Art was one of the leading reproducing piano technologies of the early 20th century, the others being American Piano Company (Ampico), introduced in 1913 too, and Welte-Mignon in 1905. These technologies flourished at that time because of th ...

piano rolls for the Aeolian Company The Aeolian Company was a musical-instrument making firm whose products included player organs, pianos, sheet music, records and phonographs. Founded in 1887, it was at one point the world's largest such firm. During the mid 20th century, it surpas ...

in London and New York City, not all of which have survived.

Stravinsky met

Stravinsky met Vera de Bosset

Vera de Bosset Stravinsky (January 7, 1889 – September 17, 1982) was an American dancer and artist. She is better known as the second wife of composer Igor Stravinsky, who married her in 1940.

Life

Vera de Bosset was born Vera Bosse, the d ...

in Paris in February 1921, while she was married to the painter and stage designer Serge Sudeikin

Sergey Yurievich Sudeikin, also known as Serge Soudeikine (19 March 1882 in Smolensk – 12 August 1946 in Nyack, New York), was a Russian artist and set-designer associated with the Ballets Russes and the Metropolitan Opera.

Biography

Havin ...

, and they began an affair that led to de Bosset leaving her husband.

In May 1921, Stravinsky and his family moved to Anglet

Anglet (; , eu, Angelu )ANGELU

Stravinsky arrived in New York City on 30 September 1939 and headed for Cambridge, Massachusetts to fulfill his engagements at Harvard. During his first two months in the US, Stravinsky stayed at Gerry's Landing, the home of art historian Edward W. Forbes. Vera arrived in January 1940 and the couple married on 9 March in

Stravinsky arrived in New York City on 30 September 1939 and headed for Cambridge, Massachusetts to fulfill his engagements at Harvard. During his first two months in the US, Stravinsky stayed at Gerry's Landing, the home of art historian Edward W. Forbes. Vera arrived in January 1940 and the couple married on 9 March in

On the same day Stravinsky became an American citizen, he arranged for

On the same day Stravinsky became an American citizen, he arranged for

In October 1969, after close to three decades in California and being denied to travel overseas by his doctors due to ill health, Stravinsky and Vera secured a two-year lease for a luxury three bedroom apartment in Essex House in New York City. Craft moved in with them, effectively putting his career on hold to care for the ailing composer. Among Stravinsky's final projects was orchestrating two preludes from ''

In October 1969, after close to three decades in California and being denied to travel overseas by his doctors due to ill health, Stravinsky and Vera secured a two-year lease for a luxury three bedroom apartment in Essex House in New York City. Craft moved in with them, effectively putting his career on hold to care for the ailing composer. Among Stravinsky's final projects was orchestrating two preludes from ''

In 1908, Stravinsky composed ''Funeral Song'' (Погребальная песня), Op. 5 to commemorate the death of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. The piece premiered 17 January 1909 in the Grand Hall of the

In 1908, Stravinsky composed ''Funeral Song'' (Погребальная песня), Op. 5 to commemorate the death of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. The piece premiered 17 January 1909 in the Grand Hall of the

Stravinsky's use of

Stravinsky's use of  The three ballets composed for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes call for particularly large orchestras:

* ''The Firebird'' (1910) is scored for the following orchestra: 2 piccolos (2nd doubles 3rd flute), 2 flutes, 3 oboes, cor anglais, 3 clarinets in A (3rd doubles piccolo clarinet in D), bass clarinet, 3 bassoons (3rd doubles contrabassoon 2), contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets in A, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, celesta, piano, 3 harps, and strings. The percussion section requires bass drum, cymbals, triangle, tambourine, tam-tam, tubular bells, glockenspiel, and xylophone. In addition, the original version calls for 3 onstage trumpets and 4 onstage Wagner tubas (2 tenor and 2 bass).

* The original version of ''

The three ballets composed for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes call for particularly large orchestras:

* ''The Firebird'' (1910) is scored for the following orchestra: 2 piccolos (2nd doubles 3rd flute), 2 flutes, 3 oboes, cor anglais, 3 clarinets in A (3rd doubles piccolo clarinet in D), bass clarinet, 3 bassoons (3rd doubles contrabassoon 2), contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets in A, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, celesta, piano, 3 harps, and strings. The percussion section requires bass drum, cymbals, triangle, tambourine, tam-tam, tubular bells, glockenspiel, and xylophone. In addition, the original version calls for 3 onstage trumpets and 4 onstage Wagner tubas (2 tenor and 2 bass).

* The original version of ''

Upon relocating to America in the 1940s, Stravinsky again embraced the liberalism of his youth, remarking that Europeans "can have their generalissimos and Führers. Leave me Mr. Truman and I'm satisfied." Towards the end of his life, at Craft's behest, Stravinsky made a return visit to his native country and composed a

Upon relocating to America in the 1940s, Stravinsky again embraced the liberalism of his youth, remarking that Europeans "can have their generalissimos and Führers. Leave me Mr. Truman and I'm satisfied." Towards the end of his life, at Craft's behest, Stravinsky made a return visit to his native country and composed a

Stravinsky was a devout member of the

Stravinsky was a devout member of the

In 1935, the American composer

In 1935, the American composer

DICTECO

* A

DICTECO

* * A

DICTECO

* * * A

DICTECO

* A

DICTECO

* Translated in English, 1936, as ''An Autobiography''. * * *

''The New York Times''. Retrieved 12 July 2021. * * * * *

Stravinsky Liable to Fine

. ''The New York Times'' (16 January) (Retrieved 22 June 2010). * Anonymous. 1957. "Stravinsky Turns 75". ''

Reprinted in ''Los Angeles Times'' "Daily Mirror" blog (3 June 2007)

(accessed 9 March 2010). * Anonymous. 1962.

Life Guide: Salutes to Stravinsky on His 80th; A Funny Faulkner, Farm Tours

, ''Life Magazine'' (8 June): 17. * Berry, David Carson. 2008.

The Roles of Invariance and Analogy in the Linear Design of Stravinsky's

'Musick to Heare.'" ''Gamut: The Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic'' 1, no. 1. * Cocteau, Jean. 1918. ''Le Coq et l'arlequin: notes de la musique''. Paris: Éditions de la Sirène. Reprinted 1979, with a preface by Georges Auric. Paris: Stock. English edition, as ''Cock and Harlequin: Notes Concerning Music'', translated by Rollo H. Myers, London: Egoist Press, 1921. * Cohen, Allen. 2004.

Howard Hanson in Theory and Practice

'. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. . * Craft, Robert. 1994. ''Stravinsky: Chronicle of a Friendship'', revised and expanded edition. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. . * Cross, Jonathan. 1999.

The Stravinsky Legacy

'. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. . * Floirat, Anetta. 2016

"The Scythian element of the Russian primitivism, in music and visual arts. Based on the work of three painters (Goncharova, Malevich and Roerich) and two composers (Stravinsky and Prokofiev")

* Floirat, Anetta. 2019

""Marc Chagall (1887–1985) and Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971), a painter and a composer facing similar twentieth-century challenges, a parallel. [revised version]"

Academia.edu. * Goubault, Christian. 1991. ''Igor Stravinsky''. Editions Champion, Musichamp l’essentiel 5, Paris 1991 (with catalogue raisonné and calendar). * Hazlewood, Charles. 20 December 2003. "Stravinsky – ''The Firebird Suite''"

Audio

''Discovering Music'',

Discovering Music: Listening LibraryProgrammes

* Joseph, Charles M. 2002.

Stravinsky and Balanchine, A Journey of Invention

'. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. . * Kohl, Jerome. 1979–80. "Exposition in Stravinsky's Orchestral Variations". ''

Annotated Catalog of Works and Work Editions of Igor Strawinsky till 1971 – Verzeichnis der Werke und Werkausgaben Igor Strawinskys bis 1971

', Leipzig: Publications of the Saxon Academy of Sciences in Leipzig. Extended edition available online since 2015, in English and German. * Kirchmeyer, Helmut. 1958. ''Igor Strawinsky. Zeitgeschichte im Persönlichkeitsbild''. Regensburg: Bosse-Verlag. * Kundera, Milan. 1995. ''Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts'', translated by Linda Asher. New York: HarperCollins. . * Lehrer, Jonah. 2007. "Igor Stravinsky and the Source of Music", in his ''Proust Was a Neuroscientist''. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. . * Libman, Lillian. 1972. ''And Music at the Close: Stravinsky's Last Years''. New York: W. W. Norton * Locanto, Massimiliano (ed.) 2014. ''Igor Stravinsky: Sounds and Gestures of Modernity.'' Salerno: Brepols. * McFarland, Mark. 2011. "Igor Stravinsky." In

Oxford Bibliographies Online: Music

'', edited by Bruce Gustavson. New York: Oxford University Press. * Page, Tim. 30 July 2006. "Classical Music: Great Composers, a Less-Than-Great Poser and an Operatic Impresario". ''

Stravinsky and the Rite of Spring: The Beginnings of a Musical Language

'. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and Oxford: University of California Press. * Vlad, Roman. 1958, 1973, 1983. ''Strawinsky''. Turin: Piccola Biblioteca Einaudi. * Vlad, Roman. 1960, 1967. ''Stravinsky''. London and New York: Oxford University Press,. * Wallace, Helen. 2007. ''Boosey & Hawkes, The Publishing Story''. London: Boosey & Hawkes. . * Walsh, Stephen. 2007. "The Composer, the Antiquarian and the Go-between: Stravinsky and the Rosenthals". ''

The Stravinsky Foundation

website * *

" 'Jews and Geniuses': An Exchange"

between

another exchange

between Niel Glixon and Craft, 27 April 1989; and th

original review

(16 February 1989) by Robert Craft of

Victoria and Albert Museum London, Department of Theatre and Performance

A full catalogue and details of access arrangements are availabl

here

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stravinsky, Igor 1882 births 1971 deaths 20th-century American composers 20th-century American conductors (music) 20th-century American male musicians 20th-century American pianists 20th-century classical composers 20th-century classical pianists Academics of the École Normale de Musique de Paris American classical composers American classical pianists American male classical composers American male classical pianists American male conductors (music) American opera composers American people of Polish descent American people of Russian descent Ballets Russes composers Burials at Isola di San Michele Composers for piano Grammy Award winners Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners Honorary Members of the Royal Philharmonic Society Emigrants from the Russian Empire to France Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Switzerland Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States Jazz-influenced classical composers Male opera composers Modernist composers Naturalized citizens of France Neoclassical composers People from Lomonosov People from Petergofsky Uyezd Pupils of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov Ragtime composers Recipients of the Léonie Sonning Music Prize Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists Russian anti-communists Russian classical pianists Russian conductors (music) Russian male conductors (music) Russian male classical composers Russian opera composers Russian Orthodox Christians from the United States Russian people of Polish descent Twelve-tone and serial composers

Biarritz

Biarritz ( , , , ; Basque also ; oc, Biàrritz ) is a city on the Bay of Biscay, on the Atlantic coast in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department in the French Basque Country in southwestern France. It is located from the border with Spain. ...

and Stravinsky completed his ''Trois mouvements de Petrouchka

''Trois mouvements de Petrouchka'' or ''Three Movements from Petrushka'' is an arrangement for piano of music from the ballet ''Petrushka'' by the composer Igor Stravinsky for the pianist Arthur Rubinstein.

History

Sergei Diaghilev, who had commi ...

'', a piano transcription of excerpts from ''Petrushka'' for Artur Rubinstein

Arthur Rubinstein ( pl, Artur Rubinstein; 28 January 188720 December 1982) was a Polish-American pianist.

. Diaghilev then requested orchestrations for a revival production of Tchaikovsky's ballet ''The Sleeping Beauty''. From then until his wife's death in 1939, Stravinsky led a double life, dividing his time between his family in Anglet, and Vera in Paris and on tour. Katya reportedly bore her husband's infidelity "with a mixture of magnanimity, bitterness, and compassion".

In June 1923, Stravinsky's ballet ''Les noces

''Les Noces'' (French for The Wedding; russian: Свадебка, ''Svadebka'') is a ballet and orchestral concert work composed by Igor Stravinsky for percussion, pianists, chorus, and vocal soloists. The composer gave it the descriptive title " ...

'' (''The Wedding'') premiered in Paris and performed by the Ballets Russes. In the following month, he started to receive money from an anonymous patron from the US who insisted to remain anonymous and only identified themselves as "Madame". They promised to send him $6,000 in the course of three years, and sent Stravinsky an initial cheque for $1,000. Despite some payments not being sent, Robert Craft

Robert Lawson Craft (October 20, 1923 – November 10, 2015) was an American conductor and writer. He is best known for his intimate professional relationship with Igor Stravinsky, on which Craft drew in producing numerous recordings and books.

...

believed that the patron was famed conductor Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appeara ...

, whom Stravinsky had recently met, and theorised that the conductor wanted to win Stravinsky over to visit the US.

In September 1924, Stravinsky bought a new home in Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative c ...

. Here, the composer re-evaluated his religious beliefs and reconnected with his Christian faith with help from a Russian priest, Father Nicholas. He also thought of his future, and used the experience of conducting the premiere of his ''Octet

Octet may refer to:

Music

* Octet (music), ensemble consisting of eight instruments or voices, or composition written for such an ensemble

** String octet, a piece of music written for eight string instruments

*** Octet (Mendelssohn), 1825 compos ...

'' at one of Serge Koussevitzky

Sergei Alexandrovich KoussevitzkyKoussevitzky's original Russian forename is usually transliterated into English as either "Sergei" or "Sergey"; however, he himself adopted the French spelling "Serge", using it in his signature. (SeThe Koussevit ...

's concerts the year before to build on his career as a conductor. Koussevitzky asked for Stravinsky to compose a new piece for one of his upcoming concerts; Stravinsky agreed to a piano concerto, to which Koussevitzky convinced him that he be the soloist at its premiere. Stravinsky agreed, and the ''Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments The Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments was written by Igor Stravinsky in Paris in 1923–24. This work was revised in 1950.

It was composed four years after the ''Symphonies of Wind Instruments'', which he wrote upon his arrival in Paris after ...

'' was first performed in May 1924. The piece was a success, and Stravinsky secured himself the rights to exclusively perform the work for the next five years. Following a European tour through the latter half of 1924, Stravinsky completed his first US tour in early 1925 which spanned two months. It opened with Stravinsky conducting an all-Stravinsky program at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

. He visited Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

six times, and the first time, in 1924, after holding three concerts with the Pau Casals Orchestra at the Gran Teatre del Liceu

Gran may refer to:

People

*Grandmother, affectionately known as "gran"

* Gran (name)

Places

* Gran, the historical German name for Esztergom, a city and the primatial metropolitan see of Hungary

* Gran, Norway, a municipality in Innlandet coun ...

, he stated: "Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

will be unforgettable for me. What I liked most was the cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the '' cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denomination ...

and the sardana

The ''sardana'' (; plural ''sardanes'' in Catalan) is a Catalan musical genre typical of Catalan culture and danced in circle following a set of steps. The dance was originally from the Empordà region, but started gaining popularity throughout ...

s".

In May 1927, Stravinsky's opera-oratorio ''Oedipus Rex

''Oedipus Rex'', also known by its Greek title, ''Oedipus Tyrannus'' ( grc, Οἰδίπους Τύραννος, ), or ''Oedipus the King'', is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles that was first performed around 429 BC. Originally, to the ancient Gr ...

'' premiered in Paris. The funding of its production was largely provided by Winnaretta Singer, Princesse Edmond de Polignac, who paid 12,000 francs for a private preview of the piece at her house. Stravinsky gave the money to Diaghilev to help finance the public performances. The premiere received a reaction, which irked Stravinsky, who had started to become annoyed at the public's fixation towards his early ballets. In the summer of 1927 Stravinsky received a commission from Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge

Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge aka Liz Coolidge (30 October 1864 – 4 November 1953), born Elizabeth Penn Sprague, was an American pianist and patron of music, especially of chamber music.

Biography

Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge's father was a we ...

, his first from the US. A wealthy patroness of music, Coolidge requested a thirty-minute ballet score for a festival to be held at the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

, for a $1,000 fee. Stravinsky accepted and wrote ''Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

'', which premiered in 1928.

From 1931 to 1933, the Stravinskys lived in Voreppe

Voreppe () is a commune in the Isère department in southeastern France. It is part of the Grenoble urban unit (agglomeration).Grenoble

lat, Gratianopolis

, commune status = Prefecture and commune

, image = Panorama grenoble.png

, image size =

, caption = From upper left: Panorama of the city, Grenoble’s cable cars, place Saint- ...

in southeastern France. In June 1934, the couple acquired French citizenship. Later in that year, they left Voreppe to live on rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré

The Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré () is a street located in the 8th arrondissement of Paris, France. Relatively narrow and nondescript, especially in comparison to the nearby Avenue des Champs-Élysées, it is cited as being one of the most luxu ...

in Paris, where they stayed for five years. The composer used his citizenship to publish his memoirs in French, entitled ''Chroniques de ma Vie'' in 1935, and underwent a US tour with Samuel Dushkin

Samuel Dushkin (December 13, 1891 – June 24, 1976) was an American violinist, composer, and pedagogue of Polish birth and Jewish origin.

Dushkin was born in Suwałki, Poland. He studied at the Conservatoire de Paris, as well as with Leopold ...

. His only composition of that year was the ''Concerto for Two Solo Pianos'', which was written for himself and his son Soulima using a special double piano that Pleyel had built. The pair completed a tour of Europe and South America in 1936. In April 1937 in New York City he directed his three-part ballet '' Jeu de cartes'', itself a commission for Lincoln Kirstein

Lincoln Edward Kirstein (May 4, 1907 – January 5, 1996) was an American writer, impresario, art connoisseur, philanthropist, and cultural figure in New York City, noted especially as co-founder of the New York City Ballet. He developed and sus ...

's ballet company with choreography by George Balanchine

George Balanchine (;

Various sources:

*

*

*

* born Georgiy Melitonovich Balanchivadze; ka, გიორგი მელიტონის ძე ბალანჩივაძე; January 22, 1904 (O. S. January 9) – April 30, 1983) was ...

. Stravinsky later remembered this last European address as his unhappiest. Upon his return to Europe, Stravinsky left Paris for Annemasse

Annemasse (; Arpitan: ''Anemâsse'') is a commune in the Haute-Savoie department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region in Eastern France. Even though it covers a relatively small territory (4.98 km2 or 1.92 sq mi), it is Haute-Savoie's second ...

near the Swiss border to be near his family, after his wife and daughters Ludmila and Milena had contracted tuberculosis and were in a sanatorium. Ludmila died in late 1938, followed by his wife of 33 years, in March 1939. Stravinsky himself spent five months in hospital at Sancellemoz

Sancellemoz is a sanatorium in the town of Passy, in Haute-Savoie, eastern France. Professor Marie Curie

Marie Salomea Skłodowska–Curie ( , , ; born Maria Salomea Skłodowska, ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934) was a Polish and natur ...

, during which time his mother also died.

During his later years in Paris, Stravinsky had developed professional relationships with key people in the United States: he was already working on his Symphony in C for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) was founded by Theodore Thomas in 1891. The ensemble makes its home at Orchestra Hall in Chicago and plays a summer season at the Ravinia Festival. The music director is Riccardo Muti, who began his tenure ...

and he had agreed to accept the Charles Eliot Norton Chair of Poetry of 1939–1940 at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

and while there, deliver six lectures on music as part of the prestigious Charles Eliot Norton Lectures

The Charles Eliot Norton Professorship of Poetry at Harvard University was established in 1925 as an annual lectureship in "poetry in the broadest sense" and named for the university's former professor of fine arts. Distinguished creative figures ...

.

Life in the United States, 1939–1971

Early US years, 1939–1945

Stravinsky arrived in New York City on 30 September 1939 and headed for Cambridge, Massachusetts to fulfill his engagements at Harvard. During his first two months in the US, Stravinsky stayed at Gerry's Landing, the home of art historian Edward W. Forbes. Vera arrived in January 1940 and the couple married on 9 March in

Stravinsky arrived in New York City on 30 September 1939 and headed for Cambridge, Massachusetts to fulfill his engagements at Harvard. During his first two months in the US, Stravinsky stayed at Gerry's Landing, the home of art historian Edward W. Forbes. Vera arrived in January 1940 and the couple married on 9 March in Bedford, Massachusetts

Bedford is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. The population of Bedford was 14,383 at the time of the 2020 United States Census.

History

''The following compilation comes from Ellen Abrams (1999) based on information ...

. After a period of travel, the two moved into a home in Beverly Hills, California

Beverly Hills is a city located in Los Angeles County, California. A notable and historic suburb of Greater Los Angeles, it is in a wealthy area immediately southwest of the Hollywood Hills, approximately northwest of downtown Los Angeles. B ...

before they settled in Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood, ...

from 1941. Stravinsky felt the warmer Californian climate would benefit his health. Stravinsky had adapted to life in France, but moving to America at the age of 58 was a very different prospect. For a while, he maintained a circle of contacts and émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French ''émigrer'', "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Huguenots fled France followi ...

friends from Russia, but he eventually found that this did not sustain his intellectual and professional life. He was drawn to the growing cultural life of Los Angeles, especially during World War II, when writers, musicians, composers, and conductors settled in the area. Music critic Bernard Holland

Bernard Holland (born 1933) is an American music critic. He served on the staff of '' The New York Times'' from 1981 until 2008 and held the post of chief music critic from 1995, contributing 4,575 articles to the newspaper. He then became the Nat ...

claimed Stravinsky was especially fond of British writers, who visited him in Beverly Hills, "like W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

, Christopher Isherwood

Christopher William Bradshaw Isherwood (26 August 1904 – 4 January 1986) was an Anglo-American novelist, playwright, screenwriter, autobiographer, and diarist. His best-known works include '' Goodbye to Berlin'' (1939), a semi-autobiographical ...

, Dylan Thomas

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer whose works include the poems "Do not go gentle into that good night" and "And death shall have no dominion", as well as the "play for voices" ''Under ...

. They shared the composer's taste for hard spirits – especially Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxley ...

, with whom Stravinsky spoke in French." Stravinsky and Huxley had a tradition of Saturday lunches for west coast avant-garde and luminaries.

In 1940, Stravinsky completed his ''Symphony in C'' and conducted the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at its premiere later that year. It was at this time when Stravinsky began to associate himself with film music; the first major film to use his music was Walt Disney

Walter Elias Disney (; December 5, 1901December 15, 1966) was an American animator, film producer and entrepreneur. A pioneer of the American animation industry, he introduced several developments in the production of cartoons. As a film p ...

's animated feature ''Fantasia

Fantasia International Film Festival (also known as Fantasia-fest, FanTasia, and Fant-Asia) is a film festival that has been based mainly in Montreal since its founding in 1996. Regularly held in July of each year, it is valued by both hardcore ...

'' (1940) which includes parts of ''The Rite of Spring'' rearranged by Leopold Stokowski to a segment depicting the history of Earth and the age of dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s. Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American actor, director, producer, and screenwriter, known for his innovative work in film, radio and theatre. He is considered to be among the greatest and most influential f ...

urged Stravinsky to write the score for ''Jane Eyre

''Jane Eyre'' ( ; originally published as ''Jane Eyre: An Autobiography'') is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The first ...

'' (1943), but negotiations broke down; a piece used in one of the film's hunting scenes was used in Stravinsky's orchestral work ''Ode

An ode (from grc, ᾠδή, ōdḗ) is a type of lyric poetry. Odes are elaborately structured poems praising or glorifying an event or individual, describing nature intellectually as well as emotionally. A classic ode is structured in three majo ...

'' (1943). An offer to score '' The Song of Bernadette'' (1943) also fell through; Stravinsky deemed the terms fell into the producer's favour. Music he had written for the film was later used in his ''Symphony in Three Movements

The Symphony in Three Movements is a work by Russian expatriate composer Igor Stravinsky. Stravinsky wrote the symphony from 1942–45 on commission by the Philharmonic Symphony Society of New York. It was premièred by the New York Philharmoni ...

''.

Stravinsky's unconventional dominant seventh chord

In music theory, a dominant seventh chord, or major minor seventh chord, is a seventh chord, usually built on the fifth degree of the major scale, and composed of a root, major third, perfect fifth, and minor seventh. Thus it is a major triad tog ...

in his arrangement of the "Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written on September 14, 1814, by 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key after witnessing the bo ...

" led to an incident with the Boston police on 15 January 1944, and he was warned that the authorities could impose a $100 fine upon any "re-arrangement of the national anthem in whole or in part". The police, as it turned out, were wrong. The law in question merely forbade using the national anthem "as dance music, as an exit march, or as a part of a medley of any kind", but the incident soon established itself as a myth, in which Stravinsky was supposedly arrested, held in custody for several nights, and photographed for police records.

On 28 December 1945, Stravinsky and his wife Vera became naturalized

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

US citizens. Their sponsor and witness was actor Edward G. Robinson.

Last major works, 1945–1966

On the same day Stravinsky became an American citizen, he arranged for

On the same day Stravinsky became an American citizen, he arranged for Boosey & Hawkes

Boosey & Hawkes is a British music publisher purported to be the largest specialist classical music publisher in the world. Until 2003, it was also a major manufacturer of brass, string and woodwind musical instruments.

Formed in 1930 throu ...

to publish rearrangements of several of his compositions and used his newly acquired American citizenship to secure a copyright on the material, thus allowing him to earn money from them. The five-year contract was finalised and signed in January 1947 which included a guarantee of $10,000 per for the first two years, then $12,000 for the remaining three.

In late 1945, Stravinsky received a commission from Europe, his first since ''Perséphone'', in the form of a string piece for the 20th anniversary for Paul Sacher

Paul Sacher (28 April 190626 May 1999) was a Swiss conductor, patron and billionaire businessperson. At the time of his death Sacher was majority shareholder of pharmaceutical company Hoffmann-La Roche and was considered the third richest person i ...

's Basle Chamber Orchestra. The '' Concerto in D'' premiered in 1947. In January 1946, Stravinsky conducted the premiere of his ''Symphony in Three Movements'' at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

in New York City. It marked his first premiere in the US. In 1947, Stravinsky was inspired to write his English-language opera ''The Rake's Progress

''The Rake's Progress'' is an English-language opera from 1951 in three acts and an epilogue by Igor Stravinsky. The libretto, written by W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman, is based loosely on the eight paintings and engravings ''A Rake's Progres ...

'' by a visit to a Chicago exhibition of the same-titled series of paintings by the eighteenth-century British artist William Hogarth

William Hogarth (; 10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was an English painter, engraver, pictorial satirist, social critic, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like s ...

, which tells the story of a fashionable wastrel descending into ruin. Auden and writer Chester Kallman

Chester Simon Kallman (January 7, 1921 – January 18, 1975) was an American poet, librettist, and translator, best known for collaborating with W. H. Auden on opera librettos for Igor Stravinsky and other composers.

Life

Kallman was born in ...

worked on the libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the t ...

. The opera premiered in 1951 and marks the final work of Stravinsky's neoclassical period. While composing ''The Rake's Progress'', Stravinsky befriended Robert Craft

Robert Lawson Craft (October 20, 1923 – November 10, 2015) was an American conductor and writer. He is best known for his intimate professional relationship with Igor Stravinsky, on which Craft drew in producing numerous recordings and books.

...

, who became his personal assistant and close friend and encouraged the composer to write serial music

In music, serialism is a method of Musical composition, composition using series of pitches, rhythms, dynamics, timbres or other elements of music, musical elements. Serialism began primarily with Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, thou ...

. This began Stravinsky's third and final distinct musical period which lasted until his death.

In 1953, Stravinsky agreed to compose a new opera with a libretto by Dylan Thomas

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer whose works include the poems "Do not go gentle into that good night" and "And death shall have no dominion", as well as the "play for voices" ''Under ...

, which detailed the recreation of the world after one man and one woman remained on Earth after a nuclear disaster. Development on the project came to a sudden end following Thomas's death in November of that year. Stravinsky completed ''In Memorian Dylan Thomas'', a piece for tenor, string quartet, and four trombones, in 1954.

In 1961, Igor and Vera Stravinsky and Robert Craft traveled to London, Zürich and Cairo on their way to Australia where Stravinsky and Craft conducted all-Stravinsky concerts in Sydney and Melbourne. They returned to California via New Zealand, Tahiti, and Mexico. In January 1962, during his tour's stop in Washington, D.C., Stravinsky attended a dinner at the White House with President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

in honour of his eightieth birthday, where he received a special medal for "the recognition his music has achieved throughout the world". In September 1962, Stravinsky returned to Russia for the first time since 1914, accepting an invitation from the Union of Soviet Composers

The Union of Russian Composers (formerly the Union of Soviet Composers, Order of Lenin Union of Composers of USSR () (1932- ), and Union of Soviet Composers of the USSR) is a state-created organization for musicians and musicologists created in 193 ...

to conduct six performances in Moscow and Leningrad. During the three-week visit he met with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

and several leading Soviet composers, including Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, , group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his Symphony No. 1 (Shostakovich), First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throug ...

and Aram Khachaturian

Aram Ilyich Khachaturian (; rus, Арам Ильич Хачатурян, , ɐˈram ɨˈlʲjitɕ xətɕɪtʊˈrʲan, Ru-Aram Ilyich Khachaturian.ogg; hy, Արամ Խաչատրյան, ''Aram Xačʿatryan''; 1 May 1978) was a Soviet and Armenian ...

. Stravinsky did not return to his Hollywood home until December 1962 in what was almost eight months of continual travelling. Following the assassination of Kennedy in 1963, Stravinsky completed his '' Elegy for J.F.K.'' in the following year. The two-minute work took the composer two days to write.

By early 1964, the long periods of travel had started to affect Stravinsky's health. His case of polycythemia

Polycythemia (also known as polycythaemia) is a laboratory finding in which the hematocrit (the volume percentage of red blood cells in the blood) and/or hemoglobin concentration are increased in the blood. Polycythemia is sometimes called erythr ...

had worsened and his friends had noticed that his movements and speech had slowed. In 1965, Stravinsky agreed to have David Oppenheim produce a documentary film about himself for the CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainm ...

network. It involved a film crew following the composer at home and on tour that year, and he was paid $10,000 for the production. The documentary includes Stravinsky's visit to Les Tilleuls, the house in Clarens, Switzerland, where he wrote the majority of ''The Rite of Spring''. The crew asked Soviet authorities for permission to film Stravinsky returning to his hometown of Ustilug, but the request was denied. In 1966, Stravinsky completed his last major work, the ''Requiem Canticles

''Requiem Canticles'' is a 15-minute composition by Igor Stravinsky, for contralto and bass soli, chorus, and orchestra. Stravinsky completed the work in 1966, and it received its first performance that same year.

The work is a partial setting o ...

''.

Final years and death, 1967–1971

In February 1967, Stravinsky and Craft directed their own concert in Miami, Florida, the composer's first in that state. By this time, Stravinsky's typical performance fee had grown to $10,000. However subsequently, upon doctor's orders, offers to perform that required him to fly were generally declined. An exception to this was a concert atMassey Hall

Massey Hall is a performing arts theatre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Opened in 1894, it is known for its outstanding acoustics and was the long-time hall of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. An intimate theatre, it was originally designed to seat ...

in Toronto, Canada in May 1967, where he conducted the relatively physically undemanding ''Pulcinella'' suite with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra

The Toronto Symphony Orchestra (TSO) is a Canadian orchestra based in Toronto, Ontario. Founded in 1906, the TSO gave regular concerts at Massey Hall until 1982, and since then has performed at Roy Thomson Hall. The TSO also manages the Toronto ...

. He had become increasingly frail and for the only time in his career, Stravinsky conducted while sitting down. It was his final performance as conductor in his lifetime. While backstage at the venue, Stravinsky informed Craft that he believed he had suffered a stroke. In August 1967, Stravinsky was hospitalised in Hollywood for bleeding stomach ulcers and thrombosis which required a blood transfusion. In his diary, Craft wrote that he spoon-fed the ailing composer and held his hand: "He says the warmth diminishes the pain."

By 1968, Stravinsky had recovered enough to resume touring across the US with him in the audience while Craft took to the conductor's post for the majority of the concerts. In May 1968, Stravinsky completed the piano arrangement of two songs by Austrian composer Hugo Wolf

Hugo Philipp Jacob Wolf (13 March 1860 – 22 February 1903) was an Austrian composer of Slovene origin, particularly noted for his art songs, or Lieder. He brought to this form a concentrated expressive intensity which was unique in late Ro ...

for a small orchestra. In October Stravinsky, Vera, and Craft travelled to Zurich, Switzerland to sort out business matters with Stravinsky's family. While there, Stravinsky's son Theodore held the manuscript of ''The Rite of Spring'' while Stravinsky signed it before giving it to Vera. The three considered relocating to Switzerland as they had become increasingly less fond of Hollywood, but they decided against it and returned to the US.

In October 1969, after close to three decades in California and being denied to travel overseas by his doctors due to ill health, Stravinsky and Vera secured a two-year lease for a luxury three bedroom apartment in Essex House in New York City. Craft moved in with them, effectively putting his career on hold to care for the ailing composer. Among Stravinsky's final projects was orchestrating two preludes from ''

In October 1969, after close to three decades in California and being denied to travel overseas by his doctors due to ill health, Stravinsky and Vera secured a two-year lease for a luxury three bedroom apartment in Essex House in New York City. Craft moved in with them, effectively putting his career on hold to care for the ailing composer. Among Stravinsky's final projects was orchestrating two preludes from ''The Well-Tempered Clavier

''The Well-Tempered Clavier'', BWV 846–893, consists of two sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the composer's time, ''clavier'', meaning keyboard, referred to a variety of in ...

'' by Bach, but it was never completed. He was hospitalised in April 1970 following a bout of pneumonia, which he successfully recovered from. Two months later, he travelled to Évian-les-Bains

Évian-les-Bains (), or simply Évian ( frp, Èvian, , or ), is a Communes of France, commune in the northern part of the Haute-Savoie Departments of France, department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Regions of France, region, Southeastern France. ...

by Lake Geneva where he reunited with his eldest son Theodore and niece Xenia.

On 18 March 1971, Stravinsky was taken to Lenox Hill Hospital

Lenox Hill Hospital (LHH) is a nationally ranked 450-bed non-profit, tertiary, research and academic medical center located on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City, servicing the tri-state area. LHH is one of the region's many unive ...

with pulmonary edema

Pulmonary edema, also known as pulmonary congestion, is excessive edema, liquid accumulation in the parenchyma, tissue and pulmonary alveolus, air spaces (usually alveoli) of the lungs. It leads to impaired gas exchange and may cause hypoxemia an ...

where he stayed for ten days. On 29 March, he moved into a newly furnished apartment at 920 Fifth Avenue