Silicon Sensing Systems on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Silicon is a

In 1787,

In 1787,

A silicon atom has fourteen

A silicon atom has fourteen

Many metal

Many metal

File:Quartz, Tibet.jpg, Quartz

File:Quartz - Agateplate, redbrown-white.jpg, Agate

File:Tridymite tabulars - Ochtendung, Eifel, Germany.jpg, Tridymite

File:Cristobalite-Fayalite-40048.jpg, Cristobalite

File:Coesiteimage.jpg, Coesite

Most crystalline forms of silica are made of infinite arrangements of tetrahedra (with Si at the center) connected at their corners, with each oxygen atom linked to two silicon atoms. In the thermodynamically stable room-temperature form, α-quartz, these tetrahedra are linked in intertwined helical chains with two different Si–O distances (159.7 and 161.7 pm) with a Si–O–Si angle of 144°. These helices can be either left- or right-handed, so that individual α-quartz crystals are optically active. At 537 °C, this transforms quickly and reversibly into the similar β-quartz, with a change of the Si–O–Si angle to 155° but a retention of handedness. Further heating to 867 °C results in another reversible phase transition to β-tridymite, in which some Si–O bonds are broken to allow for the arrangement of the tetrahedra into a more open and less dense hexagonal structure. This transition is slow and hence tridymite occurs as a metastable mineral even below this transition temperature; when cooled to about 120 °C it quickly and reversibly transforms by slight displacements of individual silicon and oxygen atoms to α-tridymite, similarly to the transition from α-quartz to β-quartz. β-tridymite slowly transforms to cubic β-cristobalite at about 1470 °C, which once again exists metastably below this transition temperature and transforms at 200–280 °C to α-cristobalite via small atomic displacements. β-cristobalite melts at 1713 °C; the freezing of silica from the melt is quite slow and vitrification, or the formation of a

Layer silicates, such as the clay minerals and the micas, are very common, and often are formed by horizontal cross-linking of metasilicate chains or planar condensation of smaller units. An example is kaolinite []; in many of these minerals cation and anion replacement is common, so that for example tetrahedral SiIV may be replaced by AlIII, octahedral AlIII by MgII, and by . Three-dimensional framework aluminosilicates are structurally very complex; they may be conceived of as starting from the structure, but having replaced up to one-half of the SiIV atoms with AlIII, they require more cations to be included in the structure to balance charge. Examples include feldspars (the most abundant minerals on the Earth), zeolites, and ultramarines. Many feldspars can be thought of as forming part of the ternary system . Their lattice is destroyed by high pressure prompting AlIII to undergo six-coordination rather than four-coordination, and this reaction destroying feldspars may be a reason for the Mohorovičić discontinuity, which would imply that the crust and mantle have the same chemical composition, but different lattices, although this is not a universally held view. Zeolites have many polyhedral cavities in their frameworks (truncated cuboctahedron, truncated cuboctahedra being most common, but other polyhedra also are known as zeolite cavities), allowing them to include loosely bound molecules such as water in their structure. Ultramarines alternate silicon and aluminium atoms and include a variety of other anions such as , , and , but are otherwise similar to the feldspars.

Layer silicates, such as the clay minerals and the micas, are very common, and often are formed by horizontal cross-linking of metasilicate chains or planar condensation of smaller units. An example is kaolinite []; in many of these minerals cation and anion replacement is common, so that for example tetrahedral SiIV may be replaced by AlIII, octahedral AlIII by MgII, and by . Three-dimensional framework aluminosilicates are structurally very complex; they may be conceived of as starting from the structure, but having replaced up to one-half of the SiIV atoms with AlIII, they require more cations to be included in the structure to balance charge. Examples include feldspars (the most abundant minerals on the Earth), zeolites, and ultramarines. Many feldspars can be thought of as forming part of the ternary system . Their lattice is destroyed by high pressure prompting AlIII to undergo six-coordination rather than four-coordination, and this reaction destroying feldspars may be a reason for the Mohorovičić discontinuity, which would imply that the crust and mantle have the same chemical composition, but different lattices, although this is not a universally held view. Zeolites have many polyhedral cavities in their frameworks (truncated cuboctahedron, truncated cuboctahedra being most common, but other polyhedra also are known as zeolite cavities), allowing them to include loosely bound molecules such as water in their structure. Ultramarines alternate silicon and aluminium atoms and include a variety of other anions such as , , and , but are otherwise similar to the feldspars.

Silicon carbide (SiC) was first made by Edward Goodrich Acheson in 1891, who named it carborundum to reference its intermediate hardness and abrasive power between diamond (an allotrope of carbon) and corundum (aluminium oxide). He soon founded a company to manufacture it, and today about one million tonnes are produced each year.{{sfn, Greenwood, Earnshaw, 1997, p=334 Silicon carbide exists in about 250 crystalline forms. The polymorphism of SiC is characterized by a large family of similar crystalline structures called polytypes. They are variations of the same chemical compound that are identical in two dimensions and differ in the third. Thus they can be viewed as layers stacked in a certain sequence.{{cite journal , doi =10.1063/1.358463 , title=Large-band-gap SiC, III–V nitride, and II–VI ZnSe-based semiconductor device technologies , year=1994 , author=Morkoç, H. , journal=Journal of Applied Physics , volume=76, issue=3 , page=1363 , last2=Strite , first2=S. , last3=Gao , first3=G.B. , last4=Lin , first4=M.E. , last5=Sverdlov , first5=B. , last6=Burns , first6=M. , bibcode=1994JAP....76.1363M It is made industrially by reduction of quartz sand with excess coke or anthracite at 2000–2500 °C in an electric furnace:{{sfn, Greenwood, Earnshaw, 1997, p=334

:{{chem, SiO, 2 + 2 C → Si + 2 CO

:Si + C → SiC

It is the most thermally stable binary silicon compound, only decomposing through loss of silicon starting from around 2700 °C. It is resistant to most aqueous acids, phosphoric acid being an exception. It forms a protective layer of

Silicon carbide (SiC) was first made by Edward Goodrich Acheson in 1891, who named it carborundum to reference its intermediate hardness and abrasive power between diamond (an allotrope of carbon) and corundum (aluminium oxide). He soon founded a company to manufacture it, and today about one million tonnes are produced each year.{{sfn, Greenwood, Earnshaw, 1997, p=334 Silicon carbide exists in about 250 crystalline forms. The polymorphism of SiC is characterized by a large family of similar crystalline structures called polytypes. They are variations of the same chemical compound that are identical in two dimensions and differ in the third. Thus they can be viewed as layers stacked in a certain sequence.{{cite journal , doi =10.1063/1.358463 , title=Large-band-gap SiC, III–V nitride, and II–VI ZnSe-based semiconductor device technologies , year=1994 , author=Morkoç, H. , journal=Journal of Applied Physics , volume=76, issue=3 , page=1363 , last2=Strite , first2=S. , last3=Gao , first3=G.B. , last4=Lin , first4=M.E. , last5=Sverdlov , first5=B. , last6=Burns , first6=M. , bibcode=1994JAP....76.1363M It is made industrially by reduction of quartz sand with excess coke or anthracite at 2000–2500 °C in an electric furnace:{{sfn, Greenwood, Earnshaw, 1997, p=334

:{{chem, SiO, 2 + 2 C → Si + 2 CO

:Si + C → SiC

It is the most thermally stable binary silicon compound, only decomposing through loss of silicon starting from around 2700 °C. It is resistant to most aqueous acids, phosphoric acid being an exception. It forms a protective layer of

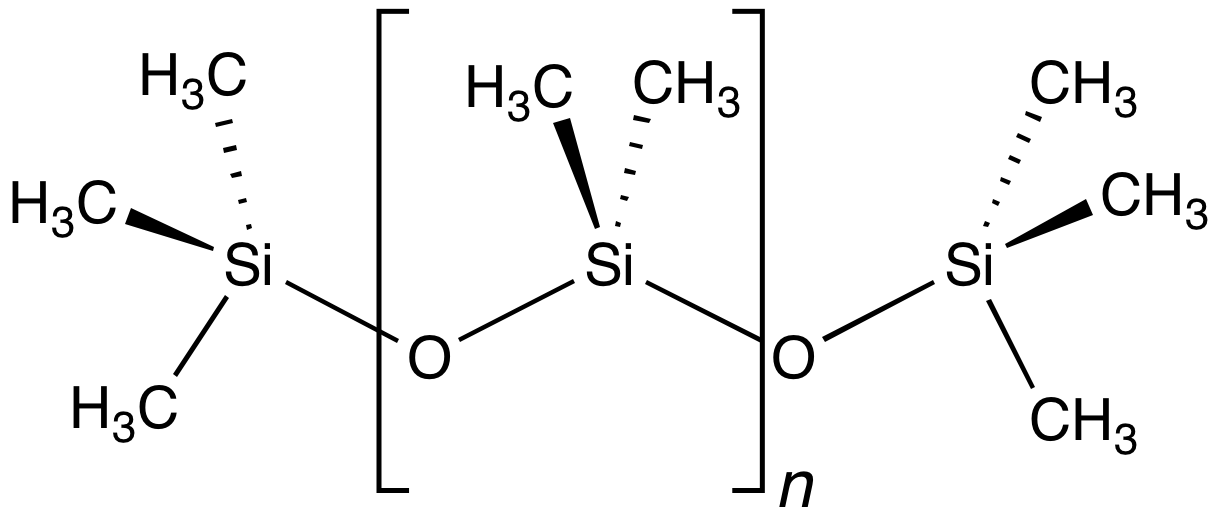

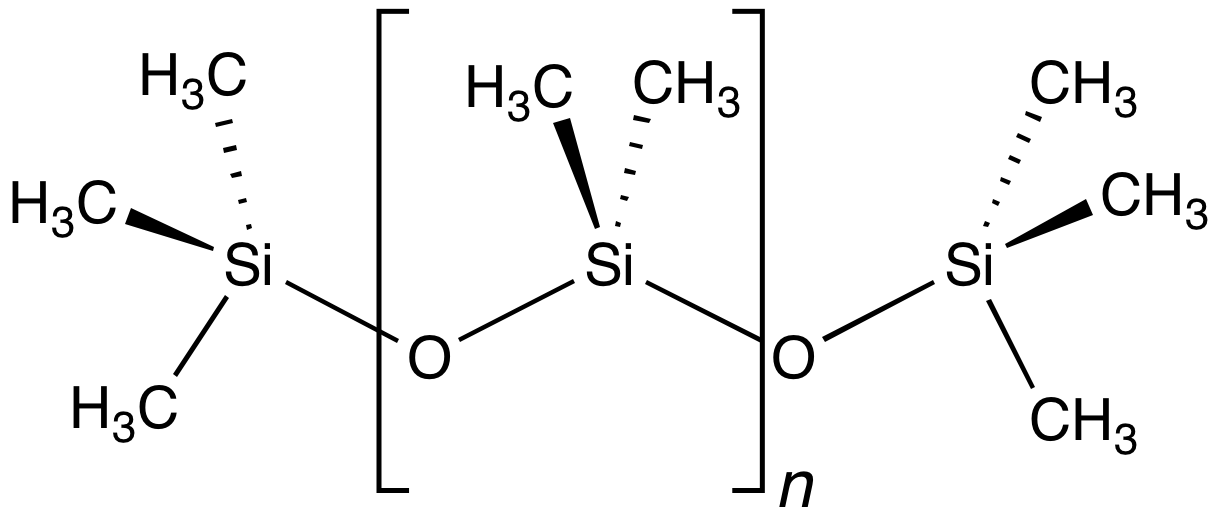

The word "silicone" was first used by Frederic Kipping in 1901. He invented the word to illustrate the similarity of chemical formulae between {{chem, Ph, 2, SiO and benzophenone, {{chem, Ph, 2, CO, although he also stressed the lack of chemical resemblance due to the polymeric structure of {{chem, Ph, 2, SiO, which is not shared by {{chem, Ph, 2, CO.{{sfn, Greenwood, Earnshaw, 1997, p=361

Silicones may be considered analogous to mineral silicates, in which the methyl groups of the silicones correspond to the isoelectronic <{{chem, O, − of the silicates.{{sfn, Greenwood, Earnshaw, 1997, p=361 They are quite stable to extreme temperatures, oxidation, and water, and have useful dielectric, antistick, and antifoam properties. Furthermore, they are resistant over long periods of time to ultraviolet radiation and weathering, and are inert physiologically. They are fairly unreactive, but do react with concentrated solutions bearing the hydroxide ion and fluorinating agents, and occasionally, may even be used as mild reagents for selective syntheses. For example, {{chem, (Me, 3, Si), 2, O is valuable for the preparation of derivatives of molybdenum and tungsten oxyhalides, converting a tungsten hexachloride suspension in dichloroethane solution quantitatively to {{chem, WOCl, 4 in under an hour at room temperature, and then to yellow {{chem, WO, 2, C, 2 at 100 °C in light petroleum at a yield of 95% overnight.{{sfn, Greenwood, Earnshaw, 1997, p=361

The word "silicone" was first used by Frederic Kipping in 1901. He invented the word to illustrate the similarity of chemical formulae between {{chem, Ph, 2, SiO and benzophenone, {{chem, Ph, 2, CO, although he also stressed the lack of chemical resemblance due to the polymeric structure of {{chem, Ph, 2, SiO, which is not shared by {{chem, Ph, 2, CO.{{sfn, Greenwood, Earnshaw, 1997, p=361

Silicones may be considered analogous to mineral silicates, in which the methyl groups of the silicones correspond to the isoelectronic <{{chem, O, − of the silicates.{{sfn, Greenwood, Earnshaw, 1997, p=361 They are quite stable to extreme temperatures, oxidation, and water, and have useful dielectric, antistick, and antifoam properties. Furthermore, they are resistant over long periods of time to ultraviolet radiation and weathering, and are inert physiologically. They are fairly unreactive, but do react with concentrated solutions bearing the hydroxide ion and fluorinating agents, and occasionally, may even be used as mild reagents for selective syntheses. For example, {{chem, (Me, 3, Si), 2, O is valuable for the preparation of derivatives of molybdenum and tungsten oxyhalides, converting a tungsten hexachloride suspension in dichloroethane solution quantitatively to {{chem, WOCl, 4 in under an hour at room temperature, and then to yellow {{chem, WO, 2, C, 2 at 100 °C in light petroleum at a yield of 95% overnight.{{sfn, Greenwood, Earnshaw, 1997, p=361

Silicon is the eighth most abundant element in the universe, coming after hydrogen, helium,

Silicon is the eighth most abundant element in the universe, coming after hydrogen, helium,

This reaction, known as carbothermal reduction of silicon dioxide, usually is conducted in the presence of scrap iron with low amounts of

This reaction, known as carbothermal reduction of silicon dioxide, usually is conducted in the presence of scrap iron with low amounts of

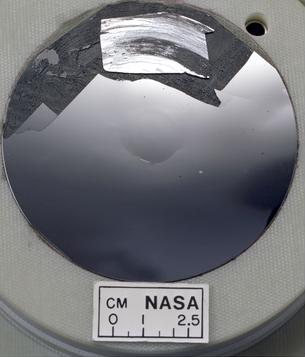

Most elemental silicon produced remains as a ferrosilicon alloy, and only approximately 20% is refined to metallurgical grade purity (a total of 1.3–1.5 million metric tons/year). An estimated 15% of the world production of metallurgical grade silicon is further refined to semiconductor purity. This typically is the "nine-9" or 99.9999999% purity, nearly defect-free single crystalline material.

Monocrystalline silicon of such purity is usually produced by the Czochralski process, and is used to produce Wafer (electronics), silicon wafers used in the

Most elemental silicon produced remains as a ferrosilicon alloy, and only approximately 20% is refined to metallurgical grade purity (a total of 1.3–1.5 million metric tons/year). An estimated 15% of the world production of metallurgical grade silicon is further refined to semiconductor purity. This typically is the "nine-9" or 99.9999999% purity, nearly defect-free single crystalline material.

Monocrystalline silicon of such purity is usually produced by the Czochralski process, and is used to produce Wafer (electronics), silicon wafers used in the

2009 Minerals Yearbook

USGS

Although silicon is readily available in the form of

Although silicon is readily available in the form of

chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

with the symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

Si and atomic number

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol ''Z'') of a chemical element is the charge number of an atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei, this is equal to the proton number (''n''p) or the number of protons found in the nucleus of every ...

14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic luster, and is a tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with other atoms when it forms chemical compounds or molecules.

Description

The combining capacity, or affinity of an ...

metalloid

A metalloid is a type of chemical element which has a preponderance of material property, properties in between, or that are a mixture of, those of metals and nonmetals. There is no standard definition of a metalloid and no complete agreement on ...

and semiconductor

A semiconductor is a material which has an electrical resistivity and conductivity, electrical conductivity value falling between that of a electrical conductor, conductor, such as copper, and an insulator (electricity), insulator, such as glas ...

. It is a member of group 14

The carbon group is a group (periodic table), periodic table group consisting of carbon (C), silicon (Si), germanium (Ge), tin (Sn), lead (Pb), and flerovium (Fl). It lies within the p-block.

In modern International Union of Pure and Applied Chem ...

in the periodic table: carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with o ...

is above it; and germanium

Germanium is a chemical element with the symbol Ge and atomic number 32. It is lustrous, hard-brittle, grayish-white and similar in appearance to silicon. It is a metalloid in the carbon group that is chemically similar to its group neighbors s ...

, tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

, lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

, and flerovium

Flerovium is a superheavy chemical element with symbol Fl and atomic number 114. It is an extremely radioactive synthetic element. It is named after the Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions of the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubn ...

are below it. It is relatively unreactive.

Because of its high chemical affinity for oxygen, it was not until 1823 that Jöns Jakob Berzelius

Jöns is a Swedish given name and a surname.

Notable people with the given name include:

* Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1779–1848), Swedish chemist

* Jöns Budde (1435–1495), Franciscan friar from the Brigittine monastery in NaantaliVallis Gratiae ...

was first able to prepare it and characterize it in pure form. Its oxide

An oxide () is a chemical compound that contains at least one oxygen atom and one other element in its chemical formula. "Oxide" itself is the dianion of oxygen, an O2– (molecular) ion. with oxygen in the oxidation state of −2. Most of the E ...

s form a family of anion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

s known as silicate

In chemistry, a silicate is any member of a family of polyatomic anions consisting of silicon and oxygen, usually with the general formula , where . The family includes orthosilicate (), metasilicate (), and pyrosilicate (, ). The name is al ...

s. Its melting and boiling points of 1414 °C and 3265 °C, respectively, are the second highest among all the metalloids and nonmetals, being surpassed only by boron

Boron is a chemical element with the symbol B and atomic number 5. In its crystalline form it is a brittle, dark, lustrous metalloid; in its amorphous form it is a brown powder. As the lightest element of the ''boron group'' it has th ...

.

Silicon is the eighth most common element in the universe by mass, but very rarely occurs as the pure element in the Earth's crust. It is widely distributed in space in cosmic dust

Dust is made of fine particles of solid matter. On Earth, it generally consists of particles in the atmosphere that come from various sources such as soil lifted by wind (an aeolian process), volcanic eruptions, and pollution. Dust in homes ...

s, planetoids

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet. Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term ''mino ...

, and planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

s as various forms of silicon dioxide

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one ...

(silica) or silicate

In chemistry, a silicate is any member of a family of polyatomic anions consisting of silicon and oxygen, usually with the general formula , where . The family includes orthosilicate (), metasilicate (), and pyrosilicate (, ). The name is al ...

s. More than 90% of the Earth's crust is composed of silicate minerals

Silicate minerals are rock-forming minerals made up of silicate groups. They are the largest and most important class of minerals and make up approximately 90 percent of Earth's crust.

In mineralogy, silica (silicon dioxide, ) is usually con ...

, making silicon the second most abundant element in the Earth's crust (about 28% by mass), after oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

.

Most silicon is used commercially without being separated, often with very little processing of the natural minerals. Such use includes industrial construction with clays

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

, silica sand

Sand casting, also known as sand molded casting, is a metal casting process characterized by using sand as the mold material. The term "sand casting" can also refer to an object produced via the sand casting process. Sand castings are produced i ...

, and stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

. Silicates are used in Portland cement

Portland cement is the most common type of cement in general use around the world as a basic ingredient of concrete, mortar, stucco, and non-specialty grout. It was developed from other types of hydraulic lime in England in the early 19th c ...

for mortar and stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and a ...

, and mixed with silica sand and gravel

Gravel is a loose aggregation of rock fragments. Gravel occurs naturally throughout the world as a result of sedimentary and erosive geologic processes; it is also produced in large quantities commercially as crushed stone.

Gravel is classifi ...

to make concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of fine and coarse aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement (cement paste) that hardens (cures) over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most wi ...

for walkways, foundations, and roads. They are also used in whiteware ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcelain ...

s such as porcelain

Porcelain () is a ceramic material made by heating substances, generally including materials such as kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises mainl ...

, and in traditional silicate

In chemistry, a silicate is any member of a family of polyatomic anions consisting of silicon and oxygen, usually with the general formula , where . The family includes orthosilicate (), metasilicate (), and pyrosilicate (, ). The name is al ...

-based soda-lime glass

Soda lime is a mixture of NaOH and CaO chemicals, used in granular form in closed breathing environments, such as general anaesthesia, submarines, rebreathers and recompression chambers, to remove carbon dioxide from breathing gases to prevent ...

and many other specialty glass

Glass is a non-crystalline, often transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Glass is most often formed by rapid cooling (quenching) of ...

es. Silicon compounds such as silicon carbide

Silicon carbide (SiC), also known as carborundum (), is a hard chemical compound containing silicon and carbon. A semiconductor, it occurs in nature as the extremely rare mineral moissanite, but has been mass-produced as a powder and crystal sin ...

are used as abrasives and components of high-strength ceramics. Silicon is the basis of the widely used synthetic polymers called silicone

A silicone or polysiloxane is a polymer made up of siloxane (−R2Si−O−SiR2−, where R = organic group). They are typically colorless oils or rubber-like substances. Silicones are used in sealants, adhesives, lubricants, medicine, cooking ...

s.

The late 20th century to early 21st century has been described as the Silicon Age (also known as the Digital Age

The Information Age (also known as the Computer Age, Digital Age, Silicon Age, or New Media Age) is a historical period that began in the mid-20th century. It is characterized by a rapid shift from traditional industries, as established during t ...

or Information Age

The Information Age (also known as the Computer Age, Digital Age, Silicon Age, or New Media Age) is a historical period that began in the mid-20th century. It is characterized by a rapid shift from traditional industries, as established during ...

) because of the large impact that elemental silicon has on the modern world economy. The small portion of very highly purified elemental silicon used in semiconductor electronics

A semiconductor device is an electronic component that relies on the electronic properties of a semiconductor material (primarily silicon, germanium, and gallium arsenide, as well as organic semiconductors) for its function. Its conductivity li ...

(<10%) is essential to the transistors

upright=1.4, gate (G), body (B), source (S) and drain (D) terminals. The gate is separated from the body by an insulating layer (pink).

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to Electronic amplifier, amplify or electronic switch, switch e ...

and integrated circuit

An integrated circuit or monolithic integrated circuit (also referred to as an IC, a chip, or a microchip) is a set of electronic circuits on one small flat piece (or "chip") of semiconductor material, usually silicon. Large numbers of tiny ...

chips used in most modern technology such as smartphone

A smartphone is a portable computer device that combines mobile telephone and computing functions into one unit. They are distinguished from feature phones by their stronger hardware capabilities and extensive mobile operating systems, whic ...

s and other computer

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to Execution (computing), carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (computation) automatically. Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as C ...

s. In 2019, 32.4% of the semiconductor market segment was for networks and communications devices, and the semiconductors industry is projected to reach $726.73 billion by 2027.

Silicon is an essential element in biology. Only traces are required by most animals, but some sea sponges

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through ...

and microorganisms, such as diatoms

A diatom (New Latin, Neo-Latin ''diatoma''), "a cutting through, a severance", from el, διάτομος, diátomos, "cut in half, divided equally" from el, διατέμνω, diatémno, "to cut in twain". is any member of a large group com ...

and radiolaria

The Radiolaria, also called Radiozoa, are protozoa of diameter 0.1–0.2 mm that produce intricate mineral skeletons, typically with a central capsule dividing the cell (biology), cell into the inner and outer portions of endoplasm and Ecto ...

, secrete skeletal structures made of silica. Silica is deposited in many plant tissues.

History

Owing to the abundance of silicon in theEarth's crust

Earth's crust is Earth's thin outer shell of rock, referring to less than 1% of Earth's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a division of Earth's layers that includes the crust and the upper part of the mantle. The ...

, natural silicon-based materials have been used for thousands of years. Silicon rock crystal

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical form ...

s were familiar to various ancient civilizations

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

Civi ...

, such as the predynastic Egypt

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt span the period from the earliest human settlement to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period around 3100 BC, starting with the first Pharaoh, Narmer for some Egyptologists, Hor-Aha for others, with th ...

ians who used it for beads

A bead is a small, decorative object that is formed in a variety of shapes and sizes of a material such as stone, bone, shell, glass, plastic, wood, or pearl and with a small hole for threading or stringing. Beads range in size from under ...

and small vases

A vase ( or ) is an open container. It can be made from a number of materials, such as ceramics, glass, non-rusting metals, such as aluminium, brass, bronze, or stainless steel. Even wood has been used to make vases, either by using tree species ...

, as well as the ancient Chinese. Glass

Glass is a non-crystalline, often transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Glass is most often formed by rapid cooling (quenching) of ...

containing silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one ...

was manufactured by the Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

since at least 1500 BC, as well as by the ancient Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient thalassocracy, thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-st ...

. Natural silicate

In chemistry, a silicate is any member of a family of polyatomic anions consisting of silicon and oxygen, usually with the general formula , where . The family includes orthosilicate (), metasilicate (), and pyrosilicate (, ). The name is al ...

compounds were also used in various types of mortar for construction of early human dwellings

In law, a dwelling (also known as a residence or an abode) is a self-contained unit of accommodation used by one or more households as a home - such as a house, apartment, mobile home, houseboat, vehicle, or other "substantial" structure. The ...

.

Discovery

In 1787,

In 1787, Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794), When reduced without charcoal, it gave off an air which supported respiration and combustion in an enhanced way. He concluded that this was just a pure form of common air and th ...

suspected that silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one ...

might be an oxide of a fundamental chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

, but the chemical affinity In chemical physics and physical chemistry, chemical affinity is the electronic property by which dissimilar chemical species are capable of forming chemical compounds. Chemical affinity can also refer to the tendency of an atom or compound to comb ...

of silicon for oxygen is high enough that he had no means to reduce the oxide and isolate the element. After an attempt to isolate silicon in 1808, Sir Humphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet, (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several elements for the ...

proposed the name "silicium" for silicon, from the Latin ''silex'', ''silicis'' for flint, and adding the "-ium" ending because he believed it to be a metal. Most other languages use transliterated forms of Davy's name, sometimes adapted to local phonology (e.g. German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

''Silizium'', Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

''silisyum'', Catalan

Catalan may refer to:

Catalonia

From, or related to Catalonia:

* Catalan language, a Romance language

* Catalans, an ethnic group formed by the people from, or with origins in, Northern or southern Catalonia

Places

* 13178 Catalan, asteroid #1 ...

''silici'', Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian Diaspora, Armenian communities across the ...

''Սիլիցիում'' or ''Silitzioum''). A few others use instead a calque

In linguistics, a calque () or loan translation is a word or phrase borrowed from another language by literal word-for-word or root-for-root translation. When used as a verb, "to calque" means to borrow a word or phrase from another language wh ...

of the Latin root (e.g. Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

''кремний'', from ''кремень'' "flint"; Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''πυρίτιο'' from ''πυρ'' "fire"; Finnish

Finnish may refer to:

* Something or someone from, or related to Finland

* Culture of Finland

* Finnish people or Finns, the primary ethnic group in Finland

* Finnish language, the national language of the Finnish people

* Finnish cuisine

See also ...

''pii'' from ''piikivi'' "flint", Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

*Czech, ...

''křemík'' from ''křemen'' "quartz", "flint").

Gay-Lussac

Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (, , ; 6 December 1778 – 9 May 1850) was a French chemist and physicist. He is known mostly for his discovery that water is made of two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen (with Alexander von Humboldt), for two laws ...

and Thénard are thought to have prepared impure amorphous silicon

Amorphous silicon (a-Si) is the non-crystalline form of silicon used for solar cells and thin-film transistors in LCDs.

Used as semiconductor material for a-Si solar cells, or thin-film silicon solar cells, it is deposited in thin films onto ...

in 1811, through the heating of recently isolated potassium

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin ''kalium'') and atomic number19. Potassium is a silvery-white metal that is soft enough to be cut with a knife with little force. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmosphe ...

metal with silicon tetrafluoride

Silicon tetrafluoride or tetrafluorosilane is a chemical compound with the formula Si F4. This colorless gas is notable for having a narrow liquid range: its boiling point is only 4 °C above its melting point. It was first prepared in 1771 ...

, but they did not purify and characterize the product, nor identify it as a new element. Silicon was given its present name in 1817 by Scottish chemist Thomas Thomson Thomas Thomson may refer to:

* Tom Thomson (1877–1917), Canadian painter

* Thomas Thomson (apothecary) (died 1572), Scottish apothecary

* Thomas Thomson (advocate) (1768–1852), Scottish lawyer

* Thomas Thomson (botanist) (1817–1878), Scottis ...

. He retained part of Davy's name but added "-on" because he believed that silicon was a nonmetal

In chemistry, a nonmetal is a chemical element that generally lacks a predominance of metallic properties; they range from colorless gases (like hydrogen) to shiny solids (like carbon, as graphite). The electrons in nonmetals behave differentl ...

similar to boron

Boron is a chemical element with the symbol B and atomic number 5. In its crystalline form it is a brittle, dark, lustrous metalloid; in its amorphous form it is a brown powder. As the lightest element of the ''boron group'' it has th ...

and carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with o ...

. In 1824, Jöns Jacob Berzelius

Baron Jöns Jacob Berzelius (; by himself and his contemporaries named only Jacob Berzelius, 20 August 1779 – 7 August 1848) was a Swedish chemist. Berzelius is considered, along with Robert Boyle, John Dalton, and Antoine Lavoisier, to be on ...

prepared amorphous silicon using approximately the same method as Gay-Lussac (reducing potassium fluorosilicate

Potassium fluorosilicate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula .

When doped with Potassium hexafluoromanganate(IV) () it forms a narrow band red producing phosphor, (often abbreviated PSF or KSF), of economic interest due to its applic ...

with molten potassium metal), but purifying the product to a brown powder by repeatedly washing it. As a result, he is usually given credit for the element's discovery. The same year, Berzelius became the first to prepare silicon tetrachloride

Silicon tetrachloride or tetrachlorosilane is the inorganic compound with the formula SiCl4. It is a colourless volatile liquid that fumes in air. It is used to produce high purity silicon and silica for commercial applications.

Preparation

Silic ...

; silicon tetrafluoride

Silicon tetrafluoride or tetrafluorosilane is a chemical compound with the formula Si F4. This colorless gas is notable for having a narrow liquid range: its boiling point is only 4 °C above its melting point. It was first prepared in 1771 ...

had already been prepared long before in 1771 by Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (, ; 9 December 1742 – 21 May 1786) was a Swedish German pharmaceutical chemist.

Scheele discovered oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first), and identified molybdenum, tungsten, barium, hydrog ...

by dissolving silica in hydrofluoric acid

Hydrofluoric acid is a Solution (chemistry), solution of hydrogen fluoride (HF) in water. Solutions of HF are colourless, acidic and highly Corrosive substance, corrosive. It is used to make most fluorine-containing compounds; examples include th ...

.

Silicon in its more common crystalline form was not prepared until 31 years later, by Deville. By electrolyzing a mixture of sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as salt (although sea salt also contains other chemical salts), is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. With molar masses of 22.99 and 35.45 g ...

and aluminium chloride

Aluminium chloride, also known as aluminium trichloride, is an inorganic compound with the formula . It forms hexahydrate with the formula , containing six water molecules of hydration. Both are colourless crystals, but samples are often contam ...

containing approximately 10% silicon, he was able to obtain a slightly impure allotrope

Allotropy or allotropism () is the property of some chemical elements to exist in two or more different forms, in the same physical state, known as allotropes of the elements. Allotropes are different structural modifications of an element: the ...

of silicon in 1854. Later, more cost-effective methods have been developed to isolate several allotrope forms, the most recent being silicene

Silicene is a two-dimensional allotrope of silicon, with a hexagonal honeycomb structure similar to that of graphene. Contrary to graphene, silicene is not flat, but has a periodically buckled topology; the coupling between layers in silicene is ...

in 2010. Meanwhile, research on the chemistry of silicon continued; Friedrich Wöhler

Friedrich Wöhler () FRS(For) HonFRSE (31 July 180023 September 1882) was a German chemist known for his work in inorganic chemistry, being the first to isolate the chemical elements beryllium and yttrium in pure metallic form. He was the firs ...

discovered the first volatile hydrides of silicon, synthesising trichlorosilane

Trichlorosilane is an inorganic compound with the formula HCl3Si. It is a colourless, volatile liquid. Purified trichlorosilane is the principal precursor to ultrapure silicon in the semiconductor industry. In water, it rapidly decomposes to pr ...

in 1857 and silane

Silane is an inorganic compound with chemical formula, . It is a colourless, pyrophoric, toxic gas with a sharp, repulsive smell, somewhat similar to that of acetic acid. Silane is of practical interest as a precursor to elemental silicon. Sila ...

itself in 1858, but a detailed investigation of the silanes Silanes refers to diverse kinds of charge-neutral silicon compounds with the formula . The R substituents can any combination of organic or inorganic groups. Most silanes contain Si-C bonds, and are discussed under organosilicon compounds.

Examp ...

was only carried out in the early 20th century by Alfred Stock

Alfred Stock (July 16, 1876 – August 12, 1946) was a German inorganic chemist. He did pioneering research on the hydrides of boron and silicon, coordination chemistry, mercury, and mercury poisoning. The German Chemical Society's Alfred-Stock Me ...

, despite early speculation on the matter dating as far back as the beginnings of synthetic organic chemistry in the 1830s. Similarly, the first organosilicon compound

Organosilicon compounds are organometallic compounds containing carbon–silicon chemical bond, bonds. Organosilicon chemistry is the corresponding science of their preparation and properties. Most organosilicon compounds are similar to the ordin ...

, tetraethylsilane, was synthesised by Charles Friedel

Charles Friedel (; 12 March 1832 – 20 April 1899) was a French chemist and Mineralogy, mineralogist.

Life

A native of Strasbourg, France, he was a student of Louis Pasteur at the University of Paris, Sorbonne. In 1876, he became a professor of ...

and James Crafts

James Mason Crafts (March 8, 1839 – June 20, 1917) was an American chemist, mostly known for developing the Friedel–Crafts alkylation and acylation reactions with Charles Friedel in 1876.

Biography

James Crafts, the son of Royal Altamo ...

in 1863, but detailed characterisation of organosilicon chemistry was only done in the early 20th century by Frederic Kipping

Frederic Stanley Kipping FRS (16 August 1863 – 1 May 1949) was an English chemist. He undertook much of the pioneering work on silicon polymers and coined the term silicone.

Life

He was born in Salford, Lancashire, England, the son of James ...

.

Starting in the 1920s, the work of William Lawrence Bragg

Sir William Lawrence Bragg, (31 March 1890 – 1 July 1971) was an Australian-born British physicist and X-ray crystallographer, discoverer (1912) of Bragg's law of X-ray diffraction, which is basic for the determination of crystal structu ...

on X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

successfully elucidated the compositions of the silicates, which had previously been known from analytical chemistry

Analytical chemistry studies and uses instruments and methods to separate, identify, and quantify matter. In practice, separation, identification or quantification may constitute the entire analysis or be combined with another method. Separati ...

but had not yet been understood, together with Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific top ...

's development of crystal chemistry

Crystal chemistry is the study of the principles of chemistry behind crystals and their use in describing structure-property relations in solids. The principles that govern the assembly of crystal and glass structures are described, models of many ...

and Victor Goldschmidt

Victor Moritz Goldschmidt (27 January 1888 in Zürich – 20 March 1947 in Oslo) was a Norwegian mineralogist considered (together with Vladimir Vernadsky) to be the founder of modern geochemistry and crystal chemistry, developer of the Goldsch ...

's development of geochemistry

Geochemistry is the science that uses the tools and principles of chemistry to explain the mechanisms behind major geological systems such as the Earth's crust and its oceans. The realm of geochemistry extends beyond the Earth, encompassing the e ...

. The middle of the 20th century saw the development of the chemistry and industrial use of siloxane

A siloxane is a functional group in organosilicon chemistry with the Si−O−Si linkage. The parent siloxanes include the oligomeric and polymeric hydrides with the formulae H(OSiH2)''n''OH and (OSiH2)n. Siloxanes also include branched compoun ...

s and the growing use of silicone

A silicone or polysiloxane is a polymer made up of siloxane (−R2Si−O−SiR2−, where R = organic group). They are typically colorless oils or rubber-like substances. Silicones are used in sealants, adhesives, lubricants, medicine, cooking ...

polymer

A polymer (; Greek '' poly-'', "many" + ''-mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic a ...

s, elastomer

An elastomer is a polymer with viscoelasticity (i.e. both viscosity and elasticity) and with weak intermolecular forces, generally low Young's modulus and high failure strain compared with other materials. The term, a portmanteau of ''elastic p ...

s, and resin

In polymer chemistry and materials science, resin is a solid or highly viscous substance of plant or synthetic origin that is typically convertible into polymers. Resins are usually mixtures of organic compounds. This article focuses on natu ...

s. In the late 20th century, the complexity of the crystal chemistry of silicide

A silicide is a type of chemical compound that combines silicon and a (usually) more electropositive element.

Silicon is more electropositive than carbon. Silicides are structurally closer to borides than to carbides.

Similar to borides and carbi ...

s was mapped, along with the solid-state physics

Solid-state physics is the study of rigid matter, or solids, through methods such as quantum mechanics, crystallography, electromagnetism, and metallurgy. It is the largest branch of condensed matter physics. Solid-state physics studies how the l ...

of doped semiconductor

A semiconductor is a material which has an electrical resistivity and conductivity, electrical conductivity value falling between that of a electrical conductor, conductor, such as copper, and an insulator (electricity), insulator, such as glas ...

s.

Silicon semiconductors

The firstsemiconductor devices

A semiconductor device is an electronic component that relies on the electronic properties of a semiconductor material (primarily silicon, germanium, and gallium arsenide, as well as organic semiconductors) for its function. Its conductivity li ...

did not use silicon, but used galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It cryst ...

, including German physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate caus ...

Ferdinand Braun

Karl Ferdinand Braun (; 6 June 1850 – 20 April 1918) was a German electrical engineer, inventor, physicist and Nobel laureate in physics. Braun contributed significantly to the development of radio and television technology: he shared the ...

's crystal detector

A crystal detector is an obsolete electronic component used in some early 20th century radio receivers that consists of a piece of crystalline mineral which rectifies the alternating current radio signal. It was employed as a detector (demod ...

in 1874 and Indian physicist Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose

(;, ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a biologist, physicist, Botany, botanist and an early writer of science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contr ...

's radio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmit ...

crystal detector in 1901. The first silicon semiconductor device was a silicon radio crystal detector, developed by American engineer Greenleaf Whittier Pickard

Greenleaf Whittier Pickard (February 14, 1877, Portland, Maine

– January 8, 1956, Newton, Massachusetts) was a United States radio pioneer. Pickard was a researcher in the early days of wireless. While not the earliest discoverer of the rectifyi ...

in 1906.

In 1940, Russell Ohl

Russell Shoemaker Ohl (January 30, 1898 – March 20, 1987) was an American scientist who is generally recognized for patenting the modern solar cell (, "Light sensitive device").

Ohl was a notable semiconductor researcher prior to the invention o ...

discovered the p–n junction

A p–n junction is a boundary or interface between two types of semiconductor materials, p-type and n-type, inside a single crystal of semiconductor. The "p" (positive) side contains an excess of holes, while the "n" (negative) side contains ...

and photovoltaic effect

The photovoltaic effect is the generation of voltage and electric current in a material upon exposure to light. It is a physical property, physical and chemical phenomenon.

The photovoltaic effect is closely related to the photoelectric effect. F ...

s in silicon. In 1941, techniques for producing high-purity germanium

Germanium is a chemical element with the symbol Ge and atomic number 32. It is lustrous, hard-brittle, grayish-white and similar in appearance to silicon. It is a metalloid in the carbon group that is chemically similar to its group neighbors s ...

and silicon crystal

Monocrystalline silicon, more often called single-crystal silicon, in short mono c-Si or mono-Si, is the base material for silicon-based discrete components and integrated circuits used in virtually all modern electronic equipment. Mono-Si also ...

s were developed for radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths ranging from about one meter to one millimeter corresponding to frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz respectively. Different sources define different frequency ran ...

detector crystals during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. In 1947, physicist William Shockley

William Bradford Shockley Jr. (February 13, 1910 – August 12, 1989) was an American physicist and inventor. He was the manager of a research group at Bell Labs that included John Bardeen and Walter Brattain. The three scientists were jointly ...

theorized a field-effect amplifier made from germanium and silicon, but he failed to build a working device, before eventually working with germanium instead. The first working transistor was a point-contact transistor

The point-contact transistor was the first type of transistor to be successfully demonstrated. It was developed by research scientists John Bardeen and Walter Brattain at Bell Laboratories in December 1947. They worked in a group led by physicis ...

built by John Bardeen

John Bardeen (; May 23, 1908 – January 30, 1991) was an American physicist and engineer. He is the only person to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics twice: first in 1956 with William Shockley and Walter Brattain for the invention of the tran ...

and Walter Brattain

Walter Houser Brattain (; February 10, 1902 – October 13, 1987) was an American physicist at Bell Labs who, along with fellow scientists John Bardeen and William Shockley, invented the point-contact transistor in December 1947. They shared the ...

later that year while working under Shockley. In 1954, physical chemist

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistical me ...

Morris Tanenbaum

Morris Tanenbaum (November 10, 1928 - February 26, 2023) was an American physical chemist and executive who worked at Bell Laboratories and AT&T Corporation.

Tanenbaum made significant contributions in the fields of transistor development and se ...

fabricated the first silicon junction transistor

A bipolar junction transistor (BJT) is a type of transistor that uses both electrons and electron holes as charge carriers. In contrast, a unipolar transistor, such as a field-effect transistor, uses only one kind of charge carrier. A bipolar t ...

at Bell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, originally named Bell Telephone Laboratories (1925–1984),

then AT&T Bell Laboratories (1984–1996)

and Bell Labs Innovations (1996–2007),

is an American industrial research and scientific development company owned by mult ...

. In 1955, Carl Frosch

Carl John Frosch (September 6, 1908 – May 18, 1984)Carl J Frosch (1908-1984)

Find A Grave was a ...

and Lincoln Derick at Bell Labs accidentally discovered that Find A Grave was a ...

silicon dioxide

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one ...

() could be grown on silicon, and they later proposed this could mask silicon surfaces during diffusion processes

Molecular diffusion, often simply called diffusion, is the thermal motion of all (liquid or gas) particles at temperatures above absolute zero. The rate of this movement is a function of temperature, viscosity of the fluid and the size (mass) of ...

in 1958.

Silicon Age

The MOSFET, also known as the MOS transistor, is the key component of the Silicon Age. It was invented by Mohamed M. Atalla and Dawon Kahng">Mohamed M. Atalla">MOSFET, also known as the MOS transistor, is the key component of the Silicon Age. It was invented by Mohamed M. Atalla and Dawon Kahng atBell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, originally named Bell Telephone Laboratories (1925–1984),

then AT&T Bell Laboratories (1984–1996)

and Bell Labs Innovations (1996–2007),

is an American industrial research and scientific development company owned by mult ...

in 1959.

The "Silicon Age" refers to the late 20th century to early 21st century. This is due to silicon being the dominant material of the Silicon Age (also known as the Digital Age

The Information Age (also known as the Computer Age, Digital Age, Silicon Age, or New Media Age) is a historical period that began in the mid-20th century. It is characterized by a rapid shift from traditional industries, as established during t ...

or Information Age

The Information Age (also known as the Computer Age, Digital Age, Silicon Age, or New Media Age) is a historical period that began in the mid-20th century. It is characterized by a rapid shift from traditional industries, as established during ...

), similar to how the Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with t ...

, Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

and Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

were defined by the dominant materials during their respective ages of civilization.

Because silicon is an important element in high-technology semiconductor devices, many places in the world bear its name. For example, Santa Clara Valley

The Santa Clara Valley is a geologic trough in Northern California that extends 90 miles (145 km) south–southeast from San Francisco to Hollister. The longitudinal valley is bordered on the west by the Santa Cruz Mountains and on the east ...

in California acquired the nickname Silicon Valley

Silicon Valley is a region in Northern California that serves as a global center for high technology and innovation. Located in the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area, it corresponds roughly to the geographical areas San Mateo County ...

, as the element is the base material in the semiconductor industry

The semiconductor industry is the aggregate of companies engaged in the design and fabrication of semiconductors and semiconductor devices, such as transistors and integrated circuits. It formed around 1960, once the fabrication of semiconduct ...

there. Since then, many other places have been dubbed similarly, including Silicon Wadi

Silicon Wadi ( he, סִילִיקוֹן וְאֵדֵי, ) is a region in Israel that serves as one of the global centres for advanced technology. It spans the Israeli coastal plain, and is cited as among the reasons why the country has b ...

in Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, Silicon Forest

Silicon is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic luster, and is a Tetravalence, tetravalent metalloid and semiconductor. It is a member ...

in Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, Silicon Hills

Silicon Hills is a nickname for the cluster of high-tech companies in the Austin metropolitan area in the U.S. state of Texas. Silicon Hills has been a nickname for Austin since the mid-1990s. The name is analogous to Silicon Valley, but refers ...

in Austin, Texas

Austin is the capital city of the U.S. state of Texas, as well as the county seat, seat and largest city of Travis County, Texas, Travis County, with portions extending into Hays County, Texas, Hays and Williamson County, Texas, Williamson co ...

, Silicon Slopes

Silicon Slopes is a reference to the area surrounding Lehi, Utah where dozens of tech start-ups are centralized. It has been generalized to include the entire startup and technology ecosystem of Utah. Served by the Salt Lake City International ...

in Salt Lake City, Utah

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

, Silicon Saxony

Silicon Saxony is a registered industry association of nearly 300 companies in the microelectronics and related sectors in Saxony, Germany, with around 40,000 employees. Many, but not all, of those firms are situated in the north of Dresden.

Wit ...

in Germany, Silicon Valley

Silicon Valley is a region in Northern California that serves as a global center for high technology and innovation. Located in the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area, it corresponds roughly to the geographical areas San Mateo County ...

in India, Silicon Border

Silicon Border Holding Company, LLC is a commercial development site designed to produce semi-conductors for consumers in North America. The site is located in Mexicali, Baja California, along the western border of the United States of America and ...

in Mexicali, Mexico

Mexicali (; ) is the capital city of the Mexican state of Baja California. The city, seat of the Mexicali Municipality, has a population of 689,775, according to the 2010 census, while the Calexico–Mexicali metropolitan area is home to 1,000, ...

, Silicon Fen

Silicon Fen (also known as the Cambridge Cluster) is the name given to the region around Cambridge, England, which is home to a large cluster of high-tech businesses focusing on software, electronics and biotechnology, such as Arm and A ...

in Cambridge, England

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge became ...

, Silicon Roundabout

East London Tech City (also known as Tech City and Silicon Roundabout) is a Science park, technology cluster of high-tech companies located in East London, United Kingdom. Its main area lies broadly between St Luke's, London, St Luke's and Hackney ...

in London, Silicon Glen

Silicon Glen is a nickname for the high tech sector of Scotland, the name inspired by Silicon Valley in California. It is applied to the Central Belt triangle between Dundee, Inverclyde and Edinburgh, which includes Fife, Glasgow and Stirling; ...

in Scotland, Silicon Gorge

Silicon Gorge is a region in South West England in which several high-tech and research companies are based, specifically the triangle of Bristol, Swindon and Gloucester. It is ranked fifth of such areas in Europe, and is named after the Avon Gorge ...

in Bristol, England

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in S ...

, Silicon Alley

Silicon Alley is an area of high tech companies centered around southern Manhattan's Flatiron district in New York City. The term was coined in the 1990s during the dot-com boom, alluding to California's Silicon Valley tech center. The term has ...

in New York, New York

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Uni ...

and Silicon Beach

Silicon Beach is the Westside region of the Los Angeles metropolitan area that is home to more than 500 technology companies, including startups. It is particularly applied to the coastal strip from Los Angeles International Airport north to t ...

in Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

.

Characteristics

Physical and atomic

electrons

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no ...

. In the ground state, they are arranged in the electron configuration es23p2. Of these, four are valence electron

In chemistry and physics, a valence electron is an electron in the outer shell associated with an atom, and that can participate in the formation of a chemical bond if the outer shell is not closed. In a single covalent bond, a shared pair forms ...

s, occupying the 3s orbital and two of the 3p orbitals. Like the other members of its group, the lighter carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with o ...

and the heavier germanium

Germanium is a chemical element with the symbol Ge and atomic number 32. It is lustrous, hard-brittle, grayish-white and similar in appearance to silicon. It is a metalloid in the carbon group that is chemically similar to its group neighbors s ...

, tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

, and lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

, it has the same number of valence electrons as valence orbitals: hence, it can complete its octet

Octet may refer to:

Music

* Octet (music), ensemble consisting of eight instruments or voices, or composition written for such an ensemble

** String octet, a piece of music written for eight string instruments

*** Octet (Mendelssohn), 1825 compos ...

and obtain the stable noble gas

The noble gases (historically also the inert gases; sometimes referred to as aerogens) make up a class of chemical elements with similar properties; under standard conditions, they are all odorless, colorless, monatomic gases with very low chemi ...

configuration of argon

Argon is a chemical element with the symbol Ar and atomic number 18. It is in group 18 of the periodic table and is a noble gas. Argon is the third-most abundant gas in Earth's atmosphere, at 0.934% (9340 ppmv). It is more than twice as abu ...

by forming sp3 hybrid orbitals, forming tetrahedral derivatives where the central silicon atom shares an electron pair with each of the four atoms it is bonded to. The first four ionisation energies of silicon are 786.3, 1576.5, 3228.3, and 4354.4 kJ/mol respectively; these figures are high enough to preclude the possibility of simple cationic chemistry for the element. Following periodic trend

Periodic trends are specific patterns that are present in the periodic table that illustrate different aspects of a certain element. They were discovered by the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev in the year 1863. Major periodic trends include atom ...

s, its single-bond covalent radius of 117.6 pm is intermediate between those of carbon (77.2 pm) and germanium (122.3 pm). The hexacoordinate ionic radius of silicon may be considered to be 40 pm, although this must be taken as a purely notional figure given the lack of a simple cation in reality.

Electrical

At standard temperature and pressure, silicon is a shinysemiconductor

A semiconductor is a material which has an electrical resistivity and conductivity, electrical conductivity value falling between that of a electrical conductor, conductor, such as copper, and an insulator (electricity), insulator, such as glas ...

with a bluish-grey metallic lustre; as typical for semiconductors, its resistivity drops as temperature rises. This arises because silicon has a small energy gap (band gap

In solid-state physics, a band gap, also called an energy gap, is an energy range in a solid where no electronic states can exist. In graphs of the electronic band structure of solids, the band gap generally refers to the energy difference (in ...

) between its highest occupied energy levels (the valence band) and the lowest unoccupied ones (the conduction band). The Fermi level

The Fermi level of a solid-state body is the thermodynamic work required to add one electron to the body. It is a thermodynamic quantity usually denoted by ''µ'' or ''E''F

for brevity. The Fermi level does not include the work required to remove ...

is about halfway between the valence and conduction bands

In solid-state physics, the valence band and conduction band are the bands closest to the Fermi level, and thus determine the electrical conductivity of the solid. In nonmetals, the valence band is the highest range of electron energies in wh ...

and is the energy at which a state is as likely to be occupied by an electron as not. Hence pure silicon is effectively an insulator at room temperature. However, doping silicon with a pnictogen

A pnictogen ( or ; from grc, πνῑ́γω "to choke" and -gen, "generator") is any of the chemical elements in group 15 of the periodic table. Group 15 is also known as the nitrogen group or nitrogen family. Group 15 consists of the ele ...

such as phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ear ...

, arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, but ...

, or antimony

Antimony is a chemical element with the symbol Sb (from la, stibium) and atomic number 51. A lustrous gray metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (Sb2S3). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient time ...

introduces one extra electron per dopant and these may then be excited into the conduction band either thermally or photolytically, creating an n-type semiconductor

An extrinsic semiconductor is one that has been '' doped''; during manufacture of the semiconductor crystal a trace element or chemical called a doping agent has been incorporated chemically into the crystal, for the purpose of giving it different ...

. Similarly, doping silicon with a group 13 element

The Group 13 network ( pl, Trzynastka, Yiddish: ''דאָס דרײַצענטל'') was a Jewish Nazi collaborationist organization in the Warsaw Ghetto during the German occupation of Poland in World War II. The rise and fall of the Group ...

such as boron

Boron is a chemical element with the symbol B and atomic number 5. In its crystalline form it is a brittle, dark, lustrous metalloid; in its amorphous form it is a brown powder. As the lightest element of the ''boron group'' it has th ...

, aluminium

Aluminium (aluminum in American and Canadian English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. I ...

, or gallium

Gallium is a chemical element with the symbol Ga and atomic number 31. Discovered by French chemist Paul-Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran in 1875, Gallium is in group 13 of the periodic table and is similar to the other metals of the group (aluminiu ...

results in the introduction of acceptor levels that trap electrons that may be excited from the filled valence band, creating a p-type semiconductor

An extrinsic semiconductor is one that has been '' doped''; during manufacture of the semiconductor crystal a trace element or chemical called a doping agent has been incorporated chemically into the crystal, for the purpose of giving it different ...

. Joining n-type silicon to p-type silicon creates a p–n junction

A p–n junction is a boundary or interface between two types of semiconductor materials, p-type and n-type, inside a single crystal of semiconductor. The "p" (positive) side contains an excess of holes, while the "n" (negative) side contains ...

with a common Fermi level; electrons flow from n to p, while holes flow from p to n, creating a voltage drop. This p–n junction thus acts as a diode

A diode is a two-terminal electronic component that conducts current primarily in one direction (asymmetric conductance); it has low (ideally zero) resistance in one direction, and high (ideally infinite) resistance in the other.

A diode ...

that can rectify alternating current that allows current to pass more easily one way than the other. A transistor

upright=1.4, gate (G), body (B), source (S) and drain (D) terminals. The gate is separated from the body by an insulating layer (pink).

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to Electronic amplifier, amplify or electronic switch, switch e ...

is an n–p–n junction, with a thin layer of weakly p-type silicon between two n-type regions. Biasing the emitter through a small forward voltage and the collector through a large reverse voltage allows the transistor to act as a triode

A triode is an electronic amplifying vacuum tube (or ''valve'' in British English) consisting of three electrodes inside an evacuated glass envelope: a heated filament or cathode, a grid, and a plate (anode). Developed from Lee De Forest's 19 ...

amplifier.

Crystal structure

Silicon crystallises in a giant covalent structure at standard conditions, specifically in adiamond cubic

The diamond cubic crystal structure is a repeating pattern of 8 atoms that certain materials may adopt as they solidify. While the first known example was diamond, other elements in group 14 also adopt this structure, including α-tin, the sem ...

lattice ( space group 227). It thus has a high melting point of 1414 °C, as a lot of energy is required to break the strong covalent bonds and melt the solid. Upon melting silicon contracts as the long-range tetrahedral network of bonds breaks up and the voids in that network are filled in, similar to water ice when hydrogen bonds are broken upon melting. It does not have any thermodynamically stable allotropes at standard pressure, but several other crystal structures are known at higher pressures. The general trend is one of increasing coordination number

In chemistry, crystallography, and materials science, the coordination number, also called ligancy, of a central atom in a molecule or crystal is the number of atoms, molecules or ions bonded to it. The ion/molecule/atom surrounding the central i ...

with pressure, culminating in a hexagonal close-packed

In geometry, close-packing of equal spheres is a dense arrangement of congruent spheres in an infinite, regular arrangement (or lattice). Carl Friedrich Gauss proved that the highest average density – that is, the greatest fraction of space occu ...

allotrope at about 40 gigapascal