Samurai Beach, New South Wales on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

were the hereditary military nobility and officer

were the hereditary military nobility and officer

Following the

Following the

(in Japanese)''

(in Japanese)'' Shin Meikai kokugo jiten, Shin Meikai Kokugo Jiten'', fifth edition, 1997''Digital

(in Japanese) Military men, however, would not be referred to as "samurai" for many more centuries.

File:Gosannen kassen.jpg, The

The

The

File:Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba e2.jpg, Samurai of the

The thunderstorms of 1274 and the typhoon of 1281 helped the samurai defenders of Japan repel the Mongol invaders despite being vastly outnumbered. These winds became known as ''kami-no-Kaze'', which literally translates as "wind of the gods". This is often given a simplified translation as "divine wind". The ''kami-no-Kaze'' lent credence to the Japanese belief that their lands were indeed divine and under supernatural protection.

During this period, the tradition of Japanese swordsmithing developed using laminated or piled steel, a technique dating back over 2,000 years in the Mediterranean and Europe of combining layers of soft and hard steel to produce a blade with a very hard (but brittle) edge, capable of being highly sharpened, supported by a softer, tougher, more flexible spine. The Japanese swordsmiths refined this technique by using multiple layers of steel of varying composition, together with

The thunderstorms of 1274 and the typhoon of 1281 helped the samurai defenders of Japan repel the Mongol invaders despite being vastly outnumbered. These winds became known as ''kami-no-Kaze'', which literally translates as "wind of the gods". This is often given a simplified translation as "divine wind". The ''kami-no-Kaze'' lent credence to the Japanese belief that their lands were indeed divine and under supernatural protection.

During this period, the tradition of Japanese swordsmithing developed using laminated or piled steel, a technique dating back over 2,000 years in the Mediterranean and Europe of combining layers of soft and hard steel to produce a blade with a very hard (but brittle) edge, capable of being highly sharpened, supported by a softer, tougher, more flexible spine. The Japanese swordsmiths refined this technique by using multiple layers of steel of varying composition, together with  Issues of inheritance caused family strife as

Issues of inheritance caused family strife as

The

The

In 1592 and again in 1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, aiming to invade China through Korea, mobilized an army of 160,000 peasants and samurai and deployed them to Korea. Taking advantage of arquebus mastery and extensive wartime experience from the Sengoku period, Japanese samurai armies made major gains in most of Korea. A few of the famous samurai generals of this war were

In 1592 and again in 1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, aiming to invade China through Korea, mobilized an army of 160,000 peasants and samurai and deployed them to Korea. Taking advantage of arquebus mastery and extensive wartime experience from the Sengoku period, Japanese samurai armies made major gains in most of Korea. A few of the famous samurai generals of this war were  In spite of the superiority of Japanese land forces, the two expeditions ultimately failed, though they did devastate the Korean peninsula. The causes of the failure included Korean naval superiority (which, led by Admiral

In spite of the superiority of Japanese land forces, the two expeditions ultimately failed, though they did devastate the Korean peninsula. The causes of the failure included Korean naval superiority (which, led by Admiral

Many samurai forces that were active throughout this period were not deployed to Korea; most importantly, the ''

Many samurai forces that were active throughout this period were not deployed to Korea; most importantly, the ''

After the Battle of Sekigahara, when the Tokugawa shogunate defeated the

After the Battle of Sekigahara, when the Tokugawa shogunate defeated the

The relative peace of the Tokugawa era was shattered with the arrival of Commodore

The relative peace of the Tokugawa era was shattered with the arrival of Commodore  The last showing of the original samurai was in 1867 when samurai from Chōshū and

The last showing of the original samurai was in 1867 when samurai from Chōshū and

In the 1870s, samurai comprised five percent of the population, or 400,000 families with about 1.9 million members. They came under direct national jurisdiction in 1869, and of all the classes during the Meiji revolution they were the most affected.

Although many lesser samurai had been active in the

In the 1870s, samurai comprised five percent of the population, or 400,000 families with about 1.9 million members. They came under direct national jurisdiction in 1869, and of all the classes during the Meiji revolution they were the most affected.

Although many lesser samurai had been active in the

In the 13th century, Hōjō Shigetoki wrote: "When one is serving officially or in the master's court, he should not think of a hundred or a thousand people, but should consider only the importance of the master."

In the 13th century, Hōjō Shigetoki wrote: "When one is serving officially or in the master's court, he should not think of a hundred or a thousand people, but should consider only the importance of the master."  In 1412,

In 1412,

Historian H. Paul Varley notes the description of Japan given by Jesuit leader St. Francis Xavier: "There is no nation in the world which fears death less." Xavier further describes the honour and manners of the people: "I fancy that there are no people in the world more punctilious about their honour than the Japanese, for they will not put up with a single insult or even a word spoken in anger." Xavier spent 1549 to 1551 converting Japanese to Christianity. He also observed: "The Japanese are much braver and more warlike than the people of China, Korea,

Historian H. Paul Varley notes the description of Japan given by Jesuit leader St. Francis Xavier: "There is no nation in the world which fears death less." Xavier further describes the honour and manners of the people: "I fancy that there are no people in the world more punctilious about their honour than the Japanese, for they will not put up with a single insult or even a word spoken in anger." Xavier spent 1549 to 1551 converting Japanese to Christianity. He also observed: "The Japanese are much braver and more warlike than the people of China, Korea,

In general, samurai, aristocrats, and priests had a very high literacy rate in

In general, samurai, aristocrats, and priests had a very high literacy rate in

Samurai had arranged marriages, which were arranged by a go-between of the same or higher rank. While for those samurai in the upper ranks this was a necessity (as most had few opportunities to meet women), this was a formality for lower-ranked samurai. Most samurai married women from a samurai family, but for lower-ranked samurai, marriages with commoners were permitted. In these marriages a

Samurai had arranged marriages, which were arranged by a go-between of the same or higher rank. While for those samurai in the upper ranks this was a necessity (as most had few opportunities to meet women), this was a formality for lower-ranked samurai. Most samurai married women from a samurai family, but for lower-ranked samurai, marriages with commoners were permitted. In these marriages a

Maintaining the household was the main duty of women of the samurai class. This was especially crucial during early feudal Japan, when warrior husbands were often traveling abroad or engaged in clan battles. The wife, or ''okugatasama'' (meaning: one who remains in the home), was left to manage all household affairs, care for the children, and perhaps even defend the home forcibly. For this reason, many women of the samurai class were trained in wielding a polearm called a ''

Maintaining the household was the main duty of women of the samurai class. This was especially crucial during early feudal Japan, when warrior husbands were often traveling abroad or engaged in clan battles. The wife, or ''okugatasama'' (meaning: one who remains in the home), was left to manage all household affairs, care for the children, and perhaps even defend the home forcibly. For this reason, many women of the samurai class were trained in wielding a polearm called a ''

File:Kasuga_no_Tsubone_(c._1880).jpg, ''

Several people born in foreign countries were granted the title of samurai.

After Bunroku and Keichō no eki, many people born in the

Several people born in foreign countries were granted the title of samurai.

After Bunroku and Keichō no eki, many people born in the

_of_Kyushu_used_cannon_like_this_at_the_Battle_of_Okinawate_against_the_Ryūzōji_clan.

*_Commons:Samurai_staff_weapons.html" ;"title="Ryūzōji_clan.html" ;"title="DF 6-7 of 80/nowiki>">DF ...

of Kyushu used cannon like this at the Battle of Okinawate against the Ryūzōji clan">DF 6-7 of 80/nowiki>">DF ... were the hereditary military nobility and officer

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultura ...

of medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the Post-classical, post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with t ...

and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the ''daimyo

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast, hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and nominally ...

'' (the great feudal landholders). They had high prestige and special privileges such as wearing two swords and ''Kiri-sute gomen

''Kiri-sute gomen'' ( or ) is an old Japanese expression dating back to the feudal era ''right to strike'' (right of samurai to kill commoners for perceived affronts). Samurai had the right to strike with their sword at anyone of a lower class wh ...

'' (right to kill anyone of a lower class in certain situations). They cultivated the ''bushido

is a moral code concerning samurai attitudes, behavior and lifestyle. There are multiple bushido types which evolved significantly through history. Contemporary forms of bushido are still used in the social and economic organization of Japan. ...

'' codes of martial virtues, indifference to pain, and unflinching loyalty, engaging in many local battles.

Though they had predecessors in earlier military and administrative officers, the samurai truly emerged during the Kamakura shogunate

The was the feudal military government of Japan during the Kamakura period from 1185 to 1333. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Kamakura-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia'', p. 459.

The Kamakura shogunate was established by Minamoto no Y ...

, ruling from 1185 to 1333. They became the ruling political class, with significant power but also significant responsibility. During the 13th century, the samurai proved themselves as adept warriors against the invading Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal membe ...

. During the peaceful Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was characteriz ...

(1603 to 1868), they became the stewards and chamberlains of the daimyo estates, gaining managerial experience and education.

In the 1870s, samurai families comprised 5% of the population. As modern militaries emerged in the 19th century, the samurai were rendered increasingly obsolete and very expensive to maintain compared to the average conscript soldier. The Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

ended their feudal roles, and they moved into professional and entrepreneurial roles. Their memory and weaponry remain prominent in Japanese popular culture

Japanese popular culture includes Japanese cinema, cuisine, television programs, anime, manga, video games, music, and doujinshi, all of which retain older artistic and literary traditions; many of their themes and styles of presentation can be t ...

.

Terminology

In Japanese, historical warriors are usually referred to as , meaning 'warrior', or , meaning 'military family'. According to translatorWilliam Scott Wilson

William Scott Wilson (born 1944, Nashville, Tennessee) is known for translating several works of Japanese literature, mostly those relating to the martial tradition of that country.

Wilson has brought historical Chinese and Japanese thought, ph ...

: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning 'to wait upon', 'accompany persons' in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, '' saburau''. In both countries the terms were nominalized to mean 'those who serve in close attendance to the nobility', the Japanese term '' saburai'' being the nominal form of the verb." According to Wilson, an early reference to the word ''saburai'' appears in the ''Kokin Wakashū

The , commonly abbreviated as , is an early anthology of the ''waka'' form of Japanese poetry, dating from the Heian period. An imperial anthology, it was conceived by Emperor Uda () and published by order of his son Emperor Daigo () in about ...

'', the first imperial anthology of poems, completed in the early 900s.

In modern usage, ''bushi'' is often used as a synonym for ''samurai''; however, historical sources make it clear that ''bushi'' and ''samurai'' were distinct concepts, with the former referring to soldier

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a conscripted or volunteer enlisted person, a non-commissioned officer, or an officer.

Etymology

The word ''soldier'' derives from the Middle English word , from Old French ...

s or warrior

A warrior is a person specializing in combat or warfare, especially within the context of a tribal or clan-based warrior culture society that recognizes a separate warrior aristocracies, class, or caste.

History

Warriors seem to have been p ...

s and the latter referring instead to a kind of hereditary nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

. The word ''samurai'' is now closely associated with the middle and upper echelons of the warrior class. These warriors were usually associated with a clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

and their lord, and were trained as officers in military tactics and grand strategy. While these samurai numbered less than 10% of then Japan's population, their teachings can still be found today in both everyday life and in modern Japanese martial arts

Japanese martial arts refers to the variety of martial arts native to the country of Japan. At least three Japanese terms (''budō'', ''bujutsu'', and ''bugei'') are used interchangeably with the English phrase Japanese martial arts.

The usage ...

.

History

Asuka and Nara periods

Following the

Following the Battle of Hakusukinoe

The Battle of Baekgang or Battle of Baekgang-gu, also known as Battle of Hakusukinoe ( ja, 白村江の戦い, Hakusuki-no-e no Tatakai / Hakusonkō no Tatakai) in Japan, as Battle of Baijiangkou ( zh, c=白江口之战, p=Bāijiāngkǒu Zhīzh ...

against Tang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) b ...

China and Silla

Silla or Shilla (57 BCE – 935 CE) ( , Old Korean: Syera, Old Japanese: Siraki2) was a Korean kingdom located on the southern and central parts of the Korean Peninsula. Silla, along with Baekje and Goguryeo, formed the Three Kingdoms of K ...

in 663 AD, which led to a retreat from Korean affairs, Japan underwent widespread reform. One of the most important was that of the Taika Reform

The were a set of doctrines established by Emperor Kōtoku (孝徳天皇 ''Kōtoku tennō'') in the year 645. They were written shortly after the death of Prince Shōtoku and the defeat of the Soga clan (蘇我氏 ''Soga no uji''), uniting Japan ...

, issued by Prince Naka-no-Ōe (Emperor Tenji

, also known as Emperor Tenchi, was the 38th emperor of Japan, Imperial Household Agency (''Kunaichō'')天智天皇 (38)/ref> according to the traditional order of succession.Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1959). ''The Imperial House of Japan'', p. 5 ...

) in 646. This edict allowed the Japanese aristocracy to adopt the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

political structure, bureaucracy, culture, religion, and philosophy.William Wayne Farris, ''Heavenly Warriors – The Evolution of Japan's Military, 500–1300'', Harvard University Press

Harvard University Press (HUP) is a publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University, and focused on academic publishing. It is a member of the Association of American University Presses. After the retirem ...

, 1995. As part of the Taihō Code

The was an administrative reorganisation enacted in 703 in Japan, at the end of the Asuka period. It was historically one of the . It was compiled at the direction of Prince Osakabe, Fujiwara no Fuhito and Awata no Mahito. Nussbaum, Louis-Fr� ...

of 702, and the later Yōrō Code

The was one iteration of several codes or governing rules compiled in early Nara period in Classical Japan. It was compiled in 718, the second year of the Yōrō regnal era by Fujiwara no Fuhito et al., but not promulgated until 757 under the ...

,''A History of Japan'', Vol. 3 and 4, George Samson, Tuttle Publishing, 2000. the population was required to report regularly for the census, a precursor for national conscription. With an understanding of how the population was distributed, Emperor Monmu

was the 42nd emperor of Japan, Imperial Household Agency (''Kunaichō'') 文武天皇 (42) retrieved 2013-8-22. according to the traditional order of succession.

Monmu's reign spanned the years from 697 through 707.

Traditional narrative

Befo ...

introduced a law whereby 1 in 3–4 adult males were drafted into the national military. These soldiers were required to supply their own weapons, and in return were exempted from duties and taxes. This was one of the first attempts by the imperial government to form an organized army modeled after the Chinese system. It was called "Gundan-Sei" ( :ja:軍団制) by later historians and is believed to have been short-lived.

The Taihō Code classified most of the Imperial bureaucrats into 12 ranks, each divided into two sub-ranks, 1st rank being the highest adviser to the emperor. Those of 6th rank and below were referred to as "samurai" and dealt with day-to-day affairs and were initially civilian public servants, in keeping with the original derivation of this word from , a verb meaning 'to serve'.''Nihon Kokugo Daijiten

The , often abbreviated as the and sometimes known in English as ''Shogakukan's Japanese Dictionary'', is the largest Japanese language dictionary published. In the period from 1972 to 1976, Shogakukan published the 20-volume first edition. The ...

'', entry for available online her(in Japanese)''

Daijirin

is a comprehensive single-volume Japanese dictionary edited by , and first published by in 1988. This title is based upon two early Sanseidō dictionaries edited by Shōzaburō Kanazawa (金沢庄三郎, 1872–1967), ''Jirin'' (辞林 "Forest o ...

'', second edition, 1995''Nihon Kokugo Daijiten

The , often abbreviated as the and sometimes known in English as ''Shogakukan's Japanese Dictionary'', is the largest Japanese language dictionary published. In the period from 1972 to 1976, Shogakukan published the 20-volume first edition. The ...

'', entry for available online her(in Japanese)'' Shin Meikai kokugo jiten, Shin Meikai Kokugo Jiten'', fifth edition, 1997''Digital

Daijisen

The is a general-purpose Japanese dictionary published by Shogakukan in 1995 and 1998. It was designed as an "all-in-one" dictionary for native speakers of Japanese, especially high school and university students.

History

Shogakukan intended for ...

'', entries for and available online her(in Japanese) Military men, however, would not be referred to as "samurai" for many more centuries.

Heian period

In the earlyHeian period

The is the last division of classical Japanese history, running from 794 to 1185. It followed the Nara period, beginning when the 50th emperor, Emperor Kanmu, moved the capital of Japan to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto). means "peace" in Japanese. ...

, during the late 8th and early 9th centuries, Emperor Kanmu

, or Kammu, was the 50th emperor of Japan, Imperial Household Agency (''Kunaichō'') 桓武天皇 (50) retrieved 2013-8-22. according to the traditional order of succession. Kanmu reigned from 781 to 806, and it was during his reign that the sco ...

sought to consolidate and expand his rule in northern Honshū

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island separa ...

and made military campaigns against the Emishi

The (also called Ebisu and Ezo), written with Chinese characters that literally mean "shrimp barbarians," constituted an ancient ethnic group of people who lived in parts of Honshū, especially in the Tōhoku region, referred to as in contemp ...

, who resisted the governance of the Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin metropolitan area along with Osaka and Kobe. , the ci ...

-based imperial court. Emperor Kanmu introduced the title of ''sei'i-taishōgun'' (), or ''shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

'', and began to rely on the powerful regional clans to conquer the Emishi. Skilled in mounted combat and archery (kyūdō

''Kyūdō'' ( ja, 弓道) is the Japanese martial art of archery. Kyūdō is based on '' kyūjutsu'' ("art of archery"), which originated with the samurai class of feudal Japan. In 1919, the name of kyūjutsu was officially changed to kyūdō, a ...

), these clan warriors became the emperor's preferred tool for putting down rebellions; the most well-known of which was Sakanoue no Tamuramaro

was a court noble, general and ''shōgun'' of the early Heian period of Japan. He served as Dainagon, Minister of War and ''Ukon'e no Taisho'' (Major Captain of the Right Division of Inner Palace Guards). He held the ''kabane'' of Ōsukune and ...

. Though this is the first known use of the title ''shōgun'', it was a temporary title and was not imbued with political power until the 13th century. At this time (the 7th to 9th centuries), officials considered them to be merely a military section under the control of the Imperial Court.

Ultimately, Emperor Kanmu disbanded his army. From this time, the emperor's power gradually declined. While the emperor was still the ruler, powerful clans around Kyoto assumed positions as ministers, and their relatives bought positions as magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judici ...

s. To amass wealth and repay their debts, magistrates often imposed heavy taxes, resulting in many farmers becoming landless. Through protective agreements and political marriages, the aristocrats accumulated political power, eventually surpassing the traditional aristocracy.

Some clans were originally formed by farmers who had taken up arms to protect themselves from the imperial magistrates sent to govern their lands and collect taxes. These clans formed alliances to protect themselves against more powerful clans, and by the mid-Heian period, they had adopted characteristic armor and weapons (''tachi'').

Gosannen War

The Gosannen War (後三年合戦, ''gosannen kassen''), also known as the Later Three-Year War, was fought in the late 1080s in Japan's Mutsu Province on the island of Honshū.

History

The Gosannen War was part of a long struggle for power wi ...

in the 11th century

File:Sasaki Toyokichi - Nihon hana zue - Walters 95208.jpg, Samurai on horseback, wearing ō-yoroi

The is a prominent example of early Japanese armor worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The term ''ō-yoroi'' means "great armor."(Mondadori, 1979, p. 507).

History

''Ō-yoroi'' first started to appear in the 10th century during the mid ...

armor, carrying a bow (''yumi

is the Japanese term for a bow. As used in English, refers more specifically to traditional Japanese asymmetrical bows, and includes the longer and the shorter used in the practice of and , or Japanese archery.

The was an important weap ...

'') and arrows in an ''yebira

are types of quiver used in Japanese archery. The quiver is unusual in that in some cases, it may have open sides, while the arrows are held in the quiver by the tips which sit on a rest at the base of the ebira, and a rib that composes the upper ...

'' quiver

File:Kyujutsu10.jpg, Heiji rebellion in 1159

Late Heian Period, Kamakura Bakufu, and the rise of samurai

The

The Kamakura period

The is a period of Japanese history that marks the governance by the Kamakura shogunate, officially established in 1192 in Kamakura by the first ''shōgun'' Minamoto no Yoritomo after the conclusion of the Genpei War, which saw the struggle bet ...

(1185–1333) saw the rise of the samurai under shogun rule as they were "entrusted with the security of the estates" and were symbols of the ideal warrior and citizen. Originally, the emperor and non-warrior nobility employed these warrior nobles. In time they amassed enough manpower, resources and political backing, in the form of alliances with one another, to establish the first samurai-dominated government. As the power of these regional clans grew, their chief was typically a distant relative of the emperor and a lesser member of either the Fujiwara Fujiwara (, written: 藤原 lit. "''Wisteria'' field") is a Japanese surname. (In English conversation it is likely to be rendered as .) Notable people with the surname include:

; Families

* The Fujiwara clan and its members

** Fujiwara no Kamatari ...

, Minamoto

was one of the surnames bestowed by the Emperors of Japan upon members of the imperial family who were excluded from the line of succession and demoted into the ranks of the nobility from 1192 to 1333. The practice was most prevalent during the ...

, or Taira

The Taira was one of the four most important clans that dominated Japanese politics during the Heian, Kamakura and Muromachi Periods of Japanese history – the others being the Fujiwara, the Tachibana, and the Minamoto. The clan is divided i ...

clan.

Though originally sent to provincial areas for fixed four-year terms as magistrates, the ''toryo'' declined to return to the capital when their terms ended, and their sons inherited their positions and continued to lead the clans in putting down rebellions throughout Japan during the middle- and later-Heian period. Because of their rising military and economic power, the warriors ultimately became a new force in the politics of the imperial court. Their involvement in the Hōgen Rebellion

In Japanese, Hōgen may refer to several words. Among them:

* Hōgen (era) (保元, 1156–1159), an era in Japan

* Hōgen rebellion, a short civil war in 1156

* dialect (方言) — for example: "eigo no hōgen" (English dialect)

See also

* ...

in the late Heian period consolidated their power, which later pitted the rivalry of Minamoto and Taira clans against each other in the Heiji Rebellion of 1160.

The victor, Taira no Kiyomori

was a military leader and ''kugyō'' of the late Heian period of Japan. He established the first samurai-dominated administrative government in the history of Japan.

Early life

Kiyomori was born in Heian-kyō, Japan, in 1118 as the first so ...

, became an imperial advisor and was the first warrior to attain such a position. He eventually seized control of the central government, establishing the first samurai-dominated government and relegating the emperor to figurehead status. However, the Taira clan was still very conservative when compared to its eventual successor, the Minamoto, and instead of expanding or strengthening its military might, the clan had its women marry emperors and exercise control through the emperor.

The Taira and the Minamoto clashed again in 1180, beginning the Genpei War

The was a national civil war between the Taira and Minamoto clans during the late Heian period of Japan. It resulted in the downfall of the Taira and the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate under Minamoto no Yoritomo, who appointed himself ...

, which ended in 1185. Samurai fought at the naval battle of Dan-no-ura

The was a major sea battle of the Genpei War, occurring at Dan-no-ura, in the Shimonoseki Strait off the southern tip of Honshū. On April 25, 1185 (or March 24, 1185 by the official page of Shimonoseki City), the fleet of the Minamoto clan ...

, at the Shimonoseki Strait which separates Honshu and Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's five main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands ( i.e. excluding Okinawa). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regional name referred to Kyushu and its surround ...

in 1185. The victorious Minamoto no Yoritomo

was the founder and the first shogun of the Kamakura shogunate of Japan, ruling from 1192 until 1199.Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Minamoto no Yoriie" in . He was the husband of Hōjō Masako who acted as regent (''shikken'') after his ...

established the superiority of the samurai over the aristocracy. In 1190 he visited Kyoto and in 1192 became '' Sei'i Taishōgun'', establishing the Kamakura shogunate, or ''Kamakura bakufu''. Instead of ruling from Kyoto, he set up the shogunate in Kamakura

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

Kamakura has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 persons per km² over the total area of . Kamakura was designated as a city on 3 November 1939.

Kamak ...

, near his base of power. "Bakufu" means "tent government", taken from the encampments the soldiers would live in, in accordance with the Bakufu's status as a military government.

After the Genpei war, Yoritomo obtained the right to appoint ''shugo

, commonly translated as “(military) governor,” “protector,” or “constable,” was a title given to certain officials in feudal Japan. They were each appointed by the ''shōgun'' to oversee one or more of the provinces of Japan. The pos ...

'' and ''jitō

were medieval territory stewards in Japan, especially in the Kamakura and Muromachi shogunates. Appointed by the ''shōgun'', ''jitō'' managed manors including national holdings governed by the provincial governor ( kokushi). There were also d ...

'', and was allowed to organize soldiers and police, and to collect a certain amount of tax. Initially, their responsibility was restricted to arresting rebels and collecting needed army provisions and they were forbidden from interfering with '' Kokushi'' officials, but their responsibility gradually expanded. Thus, the samurai class became the political ruling power in Japan.

Shōni clan

was a family of Japanese nobles descended from the Fujiwara family, many of whom held high government offices in Kyūshū. Prior to the Kamakura period (1185–1333), "Shōni" was originally a title and post within the Kyūshū ( Dazaifu) governm ...

gather to defend against Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of th ...

's Mongolian army during the first Mongol Invasion of Japan, 1274

File:Battle of Yashima Folding Screens Kano School.jpg, Battle of Yashima

Battle of Yashima (屋島の戦い) was one of the battles of the Genpei War on March 22, 1185 in the Heian period. It occurred in Sanuki Province (Shikoku) which is now Takamatsu, Kagawa.

Background

Following a long string of defeats, the Tai ...

folding screens

Ashikaga shogunate and the Mongol invasions

Various samurai clans struggled for power during theKamakura

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

Kamakura has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 persons per km² over the total area of . Kamakura was designated as a city on 3 November 1939.

Kamak ...

and Ashikaga shogunate

The , also known as the , was the feudal military government of Japan during the Muromachi period from 1336 to 1573.Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Muromachi-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia'', p. 669.

The Ashikaga shogunate was establ ...

s. Zen Buddhism

Zen ( zh, t=禪, p=Chán; ja, text= 禅, translit=zen; ko, text=선, translit=Seon; vi, text=Thiền) is a school of Mahayana Buddhism that originated in China during the Tang dynasty, known as the Chan School (''Chánzong'' 禪宗), and ...

spread among the samurai in the 13th century and helped to shape their standards of conduct, particularly overcoming the fear of death and killing, but among the general populace Pure Land Buddhism

Pure Land Buddhism (; ja, 浄土仏教, translit=Jōdo bukkyō; , also referred to as Amidism in English,) is a broad branch of Mahayana Buddhism focused on achieving rebirth in a Buddha's Buddha-field or Pure Land. It is one of the most wid ...

was favored.

In 1274, the Mongol-founded Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fifth ...

in China sent a force of some 40,000 men and 900 ships to invade Japan in northern Kyūshū. Japan mustered a mere 10,000 samurai to meet this threat. The invading army was harassed by major thunderstorms throughout the invasion, which aided the defenders by inflicting heavy casualties. The Yuan army was eventually recalled, and the invasion was called off. The Mongol invaders used small bombs, which was likely the first appearance of bombs and gunpowder in Japan.

The Japanese defenders recognized the possibility of a renewed invasion and began construction of a great stone barrier around Hakata Bay

is a bay in the northwestern part of Fukuoka city, on the Japanese island of Kyūshū. It faces the Tsushima Strait, and features beaches and a port, though parts of the bay have been reclaimed in the expansion of the city of Fukuoka. The bay ...

in 1276. Completed in 1277, this wall stretched for 20 kilometers around the border of the bay. It would later serve as a strong defensive point against the Mongols. The Mongols attempted to settle matters in a diplomatic way from 1275 to 1279, but every envoy sent to Japan was executed.

Leading up to the second Mongolian invasion, Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of th ...

continued to send emissaries to Japan, with five diplomats sent in September 1275 to Kyūshū. Hōjō Tokimune

of the Hōjō clan was the eighth ''shikken'' (officially regent of the shōgun, but ''de facto'' ruler of Japan) of the Kamakura shogunate (reigned 1268–84), known for leading the Japanese forces against the invasion of the Mongols and fo ...

, the shikken

The was a titular post held by a member of the Hōjō clan, officially a regent of the shogunate, from 1199 to 1333, during the Kamakura period, and so he was head of the ''bakufu'' (shogunate). It was part of the era referred to as .

During rou ...

of the Kamakura shogun, responded by having the Mongolian diplomats brought to Kamakura and then beheading them. The graves of the five executed Mongol emissaries exist to this day in Kamakura at Tatsunokuchi. On 29 July 1279, five more emissaries were sent by the Mongol empire, and again beheaded, this time in Hakata. This continued defiance of the Mongol emperor set the stage for one of the most famous engagements in Japanese history.

In 1281, a Yuan army of 140,000 men with 5,000 ships was mustered for another invasion of Japan. Northern Kyūshū was defended by a Japanese army of 40,000 men. The Mongol army was still on its ships preparing for the landing operation when a typhoon hit north Kyūshū island. The casualties and damage inflicted by the typhoon, followed by the Japanese defense of the Hakata Bay barrier, resulted in the Mongols again being defeated.

The thunderstorms of 1274 and the typhoon of 1281 helped the samurai defenders of Japan repel the Mongol invaders despite being vastly outnumbered. These winds became known as ''kami-no-Kaze'', which literally translates as "wind of the gods". This is often given a simplified translation as "divine wind". The ''kami-no-Kaze'' lent credence to the Japanese belief that their lands were indeed divine and under supernatural protection.

During this period, the tradition of Japanese swordsmithing developed using laminated or piled steel, a technique dating back over 2,000 years in the Mediterranean and Europe of combining layers of soft and hard steel to produce a blade with a very hard (but brittle) edge, capable of being highly sharpened, supported by a softer, tougher, more flexible spine. The Japanese swordsmiths refined this technique by using multiple layers of steel of varying composition, together with

The thunderstorms of 1274 and the typhoon of 1281 helped the samurai defenders of Japan repel the Mongol invaders despite being vastly outnumbered. These winds became known as ''kami-no-Kaze'', which literally translates as "wind of the gods". This is often given a simplified translation as "divine wind". The ''kami-no-Kaze'' lent credence to the Japanese belief that their lands were indeed divine and under supernatural protection.

During this period, the tradition of Japanese swordsmithing developed using laminated or piled steel, a technique dating back over 2,000 years in the Mediterranean and Europe of combining layers of soft and hard steel to produce a blade with a very hard (but brittle) edge, capable of being highly sharpened, supported by a softer, tougher, more flexible spine. The Japanese swordsmiths refined this technique by using multiple layers of steel of varying composition, together with differential heat treatment

Differential heat treatment (also called selective heat treatment or local heat treatment) is a technique used during heat treating to harden or soften certain areas of a steel object, creating a difference in hardness between these areas. There ar ...

, or tempering, of the finished blade, achieved by protecting part of it with a layer of clay while quenching (as explained in the article on Japanese swordsmithing

Japanese swordsmithing is the labour-intensive bladesmithing process developed in Japan for forging traditionally made bladed weapons ( ''nihonto'') including ''katana'', ''wakizashi'', ''tantō'', ''yari'', ''naginata'', ''nagamaki'', ''tachi'', ...

). The craft was perfected in the 14th century by the great swordsmith Masamune

, was a medieval Japanese blacksmith widely acclaimed as Japan's greatest swordsmith. He created swords and daggers, known in Japanese as ''tachi'' and ''tantō'', in the ''Sōshū'' school. However, many of his forged ''tachi'' were made into ...

. The Japanese sword (''tachi

A is a type of traditionally made Japanese sword (''nihonto'') worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. ''Tachi'' and ''katana'' generally differ in length, degree of curvature, and how they were worn when sheathed, the latter depending on t ...

'' and ''katana

A is a Japanese sword characterized by a curved, single-edged blade with a circular or squared guard and long grip to accommodate two hands. Developed later than the ''tachi'', it was used by samurai in feudal Japan and worn with the edge fa ...

'') became renowned around the world for its sharpness and resistance to breaking. Many swords made using these techniques were exported across the East China Sea

The East China Sea is an arm of the Western Pacific Ocean, located directly offshore from East China. It covers an area of roughly . The sea’s northern extension between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula is the Yellow Sea, separated b ...

, a few making their way as far as India.

Issues of inheritance caused family strife as

Issues of inheritance caused family strife as primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

became common, in contrast to the division of succession designated by law before the 14th century. Invasions of neighboring samurai territories became common to avoid infighting, and bickering among samurai was a constant problem for the Kamakura and Ashikaga shogunates.

Sengoku period

The ''Sengoku jidai

The was a period in Japanese history of near-constant civil war and social upheaval from 1467 to 1615.

The Sengoku period was initiated by the Ōnin War in 1467 which collapsed the feudal system of Japan under the Ashikaga shogunate. Various ...

'' ("warring states period") was marked by the loosening of samurai culture, with people born into other social strata sometimes making a name for themselves as warriors and thus becoming ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'' samurai.

Japanese war tactics and technologies improved rapidly in the 15th and 16th centuries. Use of large numbers of infantry called ashigaru

were infantry employed by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The first known reference to ''ashigaru'' was in the 14th century, but it was during the Ashikaga shogunate (Muromachi period) that the use of ''ashigaru'' became prevalent by various ...

("light-foot", because of their light armor), formed of humble warriors or ordinary people with ''naga yari'' (a long lance

A lance is a spear designed to be used by a mounted warrior or cavalry soldier ( lancer). In ancient and medieval warfare, it evolved into the leading weapon in cavalry charges, and was unsuited for throwing or for repeated thrusting, unlike si ...

) or ''naginata

The ''naginata'' (, ) is a pole weapon and one of several varieties of traditionally made Japanese blades (''nihontō''). ''Naginata'' were originally used by the samurai class of feudal Japan, as well as by ashigaru (foot soldiers) and sōhei ( ...

'', was introduced and combined with cavalry in maneuvers. The number of people mobilized in warfare ranged from thousands to hundreds of thousands.

The

The arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

, a matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of rope that is touched to the gunpowder by a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or trigger with his finger. Before ...

gun, was introduced by the Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

via a Chinese pirate ship in 1543, and the Japanese succeeded in assimilating it within a decade. Groups of mercenaries with mass-produced arquebuses began playing a critical role. By the end of the Sengoku period, several hundred thousand firearms existed in Japan, and massive armies numbering over 100,000 clashed in battles.

Azuchi–Momoyama period

Oda, Toyotomi and Tokugawa

Oda Nobunaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period. He is regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan.

Nobunaga was head of the very powerful Oda clan, and launched a war against other ''daimyō'' to unify ...

was the well-known lord of the Nagoya

is the largest city in the Chūbu region, the fourth-most populous city and third most populous urban area in Japan, with a population of 2.3million in 2020. Located on the Pacific coast in central Honshu, it is the capital and the most pop ...

area (once called Owari Province

was a province of Japan in the area that today forms the western half of Aichi Prefecture, including the modern city of Nagoya. The province was created in 646. Owari bordered on Mikawa, Mino, and Ise Provinces. Owari and Mino provinces were ...

) and an exceptional example of a samurai of the Sengoku period. He came within a few years of, and laid down the path for his successors to follow, the reunification of Japan under a new ''bakufu'' (shogunate).

Oda Nobunaga made innovations in the fields of organization and war tactics, made heavy use of arquebuses, developed commerce and industry, and treasured innovation. Consecutive victories enabled him to realize the termination of the Ashikaga Bakufu and the disarmament of the military powers of the Buddhist monks, which had inflamed futile struggles among the populace for centuries. Attacking from the "sanctuary" of Buddhist temples, they were constant headaches to any warlord and even the emperor who tried to control their actions. He died in 1582 when one of his generals, Akechi Mitsuhide

, first called Jūbei from his clan and later from his title, was a Japanese ''samurai'' general of the Sengoku period best known as the assassin of Oda Nobunaga. Mitsuhide was a bodyguard of Ashikaga Yoshiaki and later a successful general under ...

, turned upon him with his army.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: Military Innovations that Changed the Cour ...

and Tokugawa Ieyasu

was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan, which ruled Japan from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the three "Great Unifiers" of Japan, along with his former lord Oda Nobunaga and fellow ...

, who founded the Tokugawa shogunate, were loyal followers of Nobunaga. Hideyoshi began as a peasant and became one of Nobunaga's top generals, and Ieyasu had shared his childhood with Nobunaga. Hideyoshi defeated Mitsuhide within a month and was regarded as the rightful successor of Nobunaga by avenging the treachery of Mitsuhide. These two were able to use Nobunaga's previous achievements on which build a unified Japan and there was a saying: "The reunification is a rice cake; Oda made it. Hashiba shaped it. In the end, only Ieyasu tastes it." (Hashiba is the family name that Toyotomi Hideyoshi used while he was a follower of Nobunaga.)

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who became a grand minister in 1586, created a law that non-samurai were not allowed to carry weapons, which the samurai caste codified as permanent and hereditary, thereby ending the social mobility of Japan, which lasted until the dissolution of the Edo shogunate by the Meiji revolutionaries.

The distinction between samurai and non-samurai was so obscure that during the 16th century, most male adults in any social class (even small farmers) belonged to at least one military organization of their own and served in wars before and during Hideyoshi's rule. It can be said that an "all against all" situation continued for a century. The authorized samurai families after the 17th century were those that chose to follow Nobunaga, Hideyoshi and Ieyasu. Large battles occurred during the change between regimes, and a number of defeated samurai were destroyed, went ''rōnin

A ''rōnin'' ( ; ja, 浪人, , meaning 'drifter' or 'wanderer') was a samurai without a lord or master during the feudal period of Japan (1185–1868). A samurai became masterless upon the death of his master or after the loss of his master's ...

'' or were absorbed into the general populace.

Invasions of Korea

In 1592 and again in 1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, aiming to invade China through Korea, mobilized an army of 160,000 peasants and samurai and deployed them to Korea. Taking advantage of arquebus mastery and extensive wartime experience from the Sengoku period, Japanese samurai armies made major gains in most of Korea. A few of the famous samurai generals of this war were

In 1592 and again in 1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, aiming to invade China through Korea, mobilized an army of 160,000 peasants and samurai and deployed them to Korea. Taking advantage of arquebus mastery and extensive wartime experience from the Sengoku period, Japanese samurai armies made major gains in most of Korea. A few of the famous samurai generals of this war were Katō Kiyomasa

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' of the Azuchi–Momoyama and Edo periods. His court title was Higo-no-kami. His name as a child was ''Yashamaru'', and first name was ''Toranosuke''. He was one of Hideyoshi's Seven Spears of Shizugatake.

Biography

...

, Konishi Yukinaga

Konishi Yukinaga (小西 行長, baptized under the personal name Agostinho (Portuguese for Augustine); 1558 – November 6, 1600) was a Kirishitan daimyō under Toyotomi Hideyoshi. He is notable for his role as the vanguard of the Japanes ...

, and Shimazu Yoshihiro

was the second son of Shimazu Takahisa and the younger brother of Shimazu Yoshihisa. Traditionally believed to be the 17th head of the Shimazu clan, he was a skilled general during the Sengoku period who greatly contributed to the unification o ...

. Katō Kiyomasa advanced to Orangkai territory (present-day Manchuria) bordering Korea to the northeast and crossed the border into Manchuria.

He withdrew after retaliatory attacks from the Jurchens

Jurchen (Manchu language, Manchu: ''Jušen'', ; zh, 女真, ''Nǚzhēn'', ) is a term used to collectively describe a number of East Asian people, East Asian Tungusic languages, Tungusic-speaking peoples, descended from the Donghu people. They ...

there, as it was clear he had outpaced the rest of the Japanese invasion force. Shimazu Yoshihiro led some 7,000 samurai and, despite being heavily outnumbered, defeated a host of allied Ming and Korean forces at the Battle of Sacheon in 1598, near the conclusion of the campaigns. Yoshihiro was feared as ''Oni-Shimazu'' ("Shimazu ogre") and his nickname spread across Korea and into China.

In spite of the superiority of Japanese land forces, the two expeditions ultimately failed, though they did devastate the Korean peninsula. The causes of the failure included Korean naval superiority (which, led by Admiral

In spite of the superiority of Japanese land forces, the two expeditions ultimately failed, though they did devastate the Korean peninsula. The causes of the failure included Korean naval superiority (which, led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin

Admiral Yi Sun-sin (April 28, 1545 – December 16, 1598) was a Korean admiral and military general famed for his victories against the Japanese navy during the Imjin war in the Joseon Dynasty. Over the course of his career, Admiral Yi fough ...

, harassed Japanese supply lines continuously throughout the wars, resulting in supply shortages on land), the commitment of sizable Ming forces to Korea, Korean guerrilla actions, wavering Japanese commitment to the campaigns as the wars dragged on, and the underestimation of resistance by Japanese commanders.

In the first campaign of 1592, Korean defenses on land were caught unprepared, under-trained, and under-armed. They were rapidly overrun, with only a limited number of successfully resistant engagements against the more experienced and battle-hardened Japanese forces. During the second campaign in 1597, Korean and Ming forces proved far more resilient and with the support of continued Korean naval superiority, managed to limit Japanese gains to parts of southeastern Korea. The final death blow to the Japanese campaigns in Korea came with Hideyoshi's death in late 1598 and the recall of all Japanese forces in Korea by the Council of Five Elders

The Council of Five Elders (Japanese: :jp:五大老, 五大老, ''Go-Tairō'') was a group of five powerful feudal lords (Japanese: 大名, ''Daimyō'') formed in 1598 by the Regent (Japanese: 太閤 ''Sesshō and Kampaku, Taikō'') Toyotomi Hideyo ...

, established by Hideyoshi to oversee the transition from his regency to that of his son Hideyori.

Battle of Sekigahara

Many samurai forces that were active throughout this period were not deployed to Korea; most importantly, the ''

Many samurai forces that were active throughout this period were not deployed to Korea; most importantly, the ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji era, Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast, hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and n ...

s'' Tokugawa Ieyasu

was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan, which ruled Japan from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the three "Great Unifiers" of Japan, along with his former lord Oda Nobunaga and fellow ...

carefully kept forces under his command out of the Korean campaigns, and other samurai commanders who were opposed to Hideyoshi's domination of Japan either mulled Hideyoshi's call to invade Korea or contributed a small token force.

Most commanders who opposed or otherwise resisted or resented Hideyoshi ended up as part of the so-called Eastern Army, while commanders loyal to Hideyoshi and his son (a notable exception to this trend was Katō Kiyomasa, who deployed with Tokugawa and the Eastern Army) were largely committed to the Western Army; the two opposing sides (so named for the relative geographical locations of their respective commanders' domains) later clashed, most notably at the Battle of Sekigahara

The Battle of Sekigahara (Shinjitai: ; Kyūjitai: , Hepburn romanization: ''Sekigahara no Tatakai'') was a decisive battle on October 21, 1600 (Keichō 5, 15th day of the 9th month) in what is now Gifu prefecture, Japan, at the end of ...

which was won by Tokugawa Ieyasu and the Eastern Forces, paving the way for the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

.

Social mobility was high, as the ancient regime collapsed and emerging samurai needed to maintain a large military and administrative organizations in their areas of influence. Most of the samurai families that survived to the 19th century originated in this era, declaring themselves to be the blood of one of the four ancient noble clans: Minamoto

was one of the surnames bestowed by the Emperors of Japan upon members of the imperial family who were excluded from the line of succession and demoted into the ranks of the nobility from 1192 to 1333. The practice was most prevalent during the ...

, Taira

The Taira was one of the four most important clans that dominated Japanese politics during the Heian, Kamakura and Muromachi Periods of Japanese history – the others being the Fujiwara, the Tachibana, and the Minamoto. The clan is divided i ...

, Fujiwara Fujiwara (, written: 藤原 lit. "''Wisteria'' field") is a Japanese surname. (In English conversation it is likely to be rendered as .) Notable people with the surname include:

; Families

* The Fujiwara clan and its members

** Fujiwara no Kamatari ...

and Tachibana The term has at least two different meanings, and has been used in several contexts.

People

* – a clan of ''kuge'' (court nobles) prominent in the Nara and Heian periods (710–1185)

* – a clan of ''daimyō'' (feudal lords) prominent in the Mu ...

. In most cases, however, it is difficult to prove these claims.

Tokugawa shogunate

Toyotomi clan

The was a Japanese clan that ruled over the Japanese before the Edo period.

Unity and conflict

The most influential figure within the Toyotomi was Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of the three "unifiers of Japan". Oda Nobunaga was another primary un ...

at summer campaign of the Siege of Osaka

The was a series of battles undertaken by the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate against the Toyotomi clan, and ending in that clan's destruction. Divided into two stages (winter campaign and summer campaign), and lasting from 1614 to 1615, the siege ...

in 1615, the long war period ended. During the Tokugawa shogunate, samurai increasingly became courtiers, bureaucrats, and administrators rather than warriors. With no warfare since the early 17th century, samurai gradually lost their military function during the Tokugawa era (also called the Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was characteriz ...

).

By the end of the Tokugawa era, samurai were aristocratic bureaucrats for the ''daimyōs'', with their ''daishō'', the paired long and short swords of the samurai (cf. katana

A is a Japanese sword characterized by a curved, single-edged blade with a circular or squared guard and long grip to accommodate two hands. Developed later than the ''tachi'', it was used by samurai in feudal Japan and worn with the edge fa ...

and wakizashi

The is one of the traditionally made Japanese swords (''nihontō'') worn by the samurai in feudal Japan.

History and use

The production of swords in Japan is divided into specific time periods:

) becoming more of a symbolic emblem of power rather than a weapon used in daily life. They still had the legal right to cut down any commoner who did not show proper respect , but to what extent this right was used is unknown. When the central government forced ''daimyōs'' to cut the size of their armies, unemployed rōnin became a social problem.

Theoretical obligations between a samurai and his lord (usually a ''daimyō'') increased from the Genpei era to the Edo era. They were strongly emphasized by the teachings of Confucius

Confucius ( ; zh, s=, p=Kǒng Fūzǐ, "Master Kǒng"; or commonly zh, s=, p=Kǒngzǐ, labels=no; – ) was a Chinese philosopher and politician of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. C ...

and Mencius

Mencius ( ); born Mèng Kē (); or Mèngzǐ (; 372–289 BC) was a Chinese Confucianism, Confucian Chinese philosophy, philosopher who has often been described as the "second Sage", that is, second to Confucius himself. He is part of Confuc ...

, which were required reading for the educated samurai class. The leading figures who introduced Confucianism in Japan in the early Tokugawa period were Fujiwara Seika (1561–1619), Hayashi Razan (1583–1657), and Matsunaga Sekigo (1592–1657).

The conduct of samurai served as role model behavior for the other social classes. With time on their hands, samurai spent more time in pursuit of other interests such as becoming scholars.

Modernization

The relative peace of the Tokugawa era was shattered with the arrival of Commodore

The relative peace of the Tokugawa era was shattered with the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry

Matthew Langford Perry (born August 19, 1969) is an American-Canadian actor. He is best known for his role as Chandler Bing on the NBC television sitcom ''Friends'' (1994–2004).

As well as starring in the short-lived television series ''Stud ...

's massive U.S. Navy steamships in 1853. Perry used his superior firepower to force Japan to open its borders to trade. Prior to that only a few harbor towns, under strict control from the shogunate, were allowed to participate in Western trade, and even then, it was based largely on the idea of playing the Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related Mendicant orders, mendicant Christianity, Christian Catholic religious order, religious orders within the Catholic Church. Founded in 1209 by Italian Catholic friar Francis of Assisi, these orders include t ...

s and Dominicans against one another (in exchange for the crucial arquebus technology, which in turn was a major contributor to the downfall of the classical samurai).

From 1854, the samurai army and the navy were modernized. A naval training school

The Naval Training School is the main training institution of the Namibian Navy. It was created in 2009, and is located at the Wilbard Tashiya Nakada Military Base, Walvis Bay.

History

Recognizing the need to locally train its personnel as it wa ...

was established in Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

in 1855. Naval students were sent to study in Western naval schools for several years, starting a tradition of foreign-educated future leaders, such as Admiral Enomoto. French naval engineers were hired to build naval arsenals, such as Yokosuka

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

, the city has a population of 409,478, and a population density of . The total area is . Yokosuka is the 11th most populous city in the Greater Tokyo Area, and the 12th in the Kantō region.

The city ...

and Nagasaki. By the end of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1867, the Japanese navy of the ''shōgun'' already possessed eight western-style steam warships around the flagship ''Kaiyō Maru'', which were used against pro-imperial forces during the Boshin War

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a clique seeking to seize political power in the name of the Imperi ...

, under the command of Admiral Enomoto Takeaki

Viscount was a Japanese samurai and admiral of the Tokugawa navy of Bakumatsu period Japan, who remained faithful to the Tokugawa shogunate and fought against the new Meiji government until the end of the Boshin War. He later served in the Mei ...

. A French Military Mission to Japan (1867)

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

was established to help modernize the armies of the Bakufu

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

.

The last showing of the original samurai was in 1867 when samurai from Chōshū and

The last showing of the original samurai was in 1867 when samurai from Chōshū and Satsuma Satsuma may refer to:

* Satsuma (fruit), a citrus fruit

* ''Satsuma'' (gastropod), a genus of land snails

Places Japan

* Satsuma, Kagoshima, a Japanese town

* Satsuma District, Kagoshima, a district in Kagoshima Prefecture

* Satsuma Domain, a sou ...

provinces defeated the shogunate forces in favor of the rule of the emperor in the Boshin War. The two provinces were the lands of the ''daimyōs'' that submitted to Ieyasu after the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600.

Dissolution

In the 1870s, samurai comprised five percent of the population, or 400,000 families with about 1.9 million members. They came under direct national jurisdiction in 1869, and of all the classes during the Meiji revolution they were the most affected.

Although many lesser samurai had been active in the

In the 1870s, samurai comprised five percent of the population, or 400,000 families with about 1.9 million members. They came under direct national jurisdiction in 1869, and of all the classes during the Meiji revolution they were the most affected.

Although many lesser samurai had been active in the Meiji restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

, the older ones represented an obsolete feudal institution that had a practical monopoly of military force, and to a large extent of education as well. A priority of the Meiji government was to gradually abolish the entire class of samurai and integrate them into the Japanese professional, military and business classes. Their traditional guaranteed salaries were very expensive, and in 1873 the government started taxing the stipends and began to transform them into interest-bearing government bonds; the process was completed in 1879. The main goal was to provide enough financial liquidity to enable former samurai to invest in land and industry. A military force capable of contesting not just China but the imperial powers required a large conscript army that closely followed Western standards. Germany became the model. The notion of very strict obedience to chain of command was incompatible with the individual authority of the samurai. Samurai now became ''Shizoku

The was a social class in Japan composed of former ''samurai'' after the Meiji Restoration from 1869 to 1947. ''Shizoku'' was a distinct class between the ''kazoku'' (a merger of the former ''kuge'' and ''daimyō'' classes) and ''heimin'' (commo ...

'' (; this status was abolished in 1947). The right to wear a katana in public was abolished, along with the right to execute commoners who paid them disrespect. In 1877, there was a localized samurai rebellion that was quickly crushed.

Younger samurai often became exchange students because they were ambitious, literate and well-educated. On return, some started private schools for higher education, while many samurai became reporters and writers and set up newspaper companies. Others entered governmental service. In the 1880s, 23 percent of prominent Japanese businessmen were from the samurai class; by the 1920s the number had grown to 35 percent.

Philosophy

Religious influences

The philosophies ofBuddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

and Zen

Zen ( zh, t=禪, p=Chán; ja, text= 禅, translit=zen; ko, text=선, translit=Seon; vi, text=Thiền) is a school of Mahayana Buddhism that originated in China during the Tang dynasty, known as the Chan School (''Chánzong'' 禪宗), and ...

, and to a lesser extent Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

and Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintois ...

, influenced the samurai culture. Zen meditation became an important teaching because it offered a process to calm one's mind. The Buddhist concept of reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is a ...

and rebirth led samurai to abandon torture and needless killing, while some samurai even gave up violence altogether and became Buddhist monks after coming to believe that their killings were fruitless. Some were killed as they came to terms with these conclusions in the battlefield. The most defining role that Confucianism played in samurai philosophy was to stress the importance of the lord-retainer relationship—the loyalty that a samurai was required to show his lord.

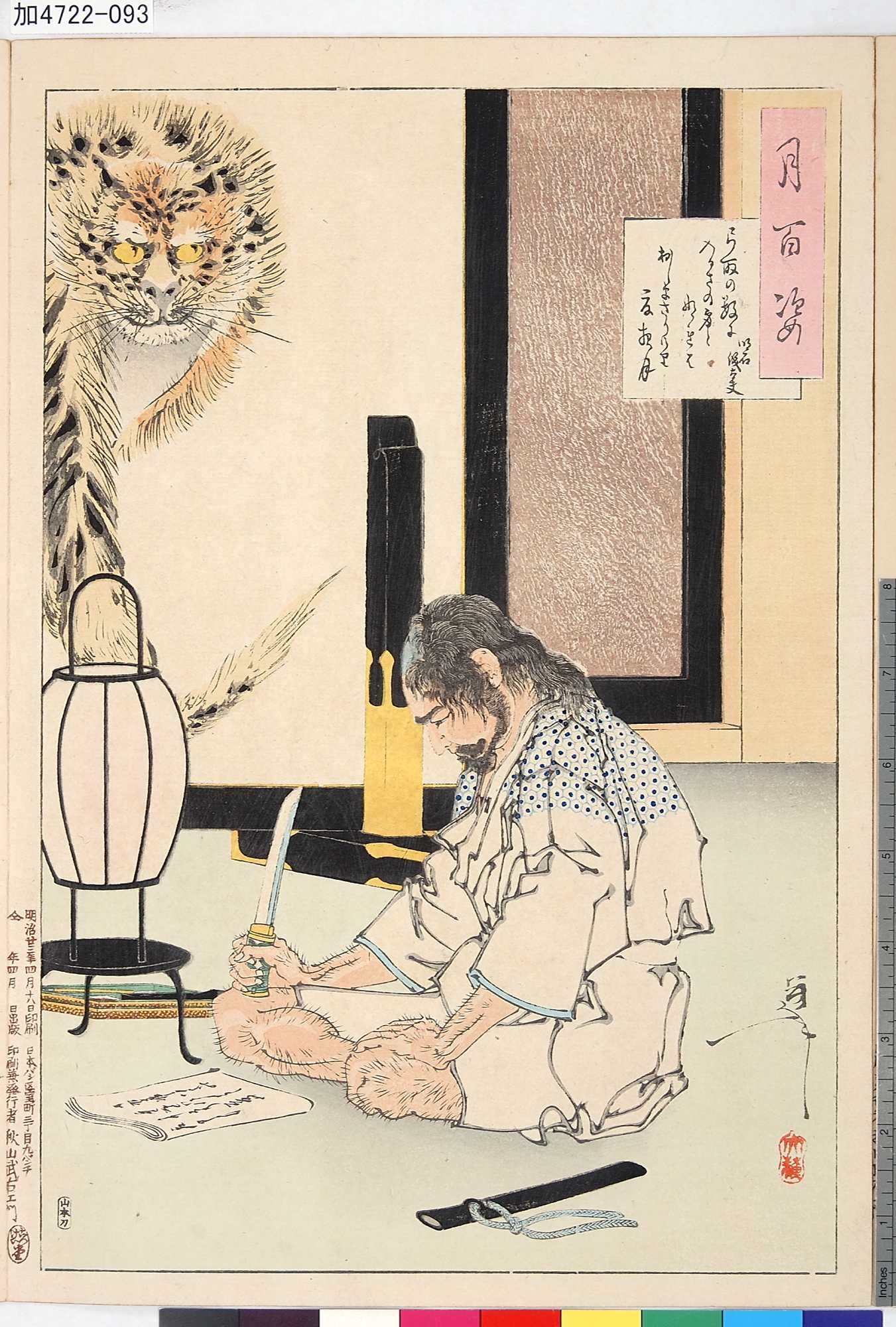

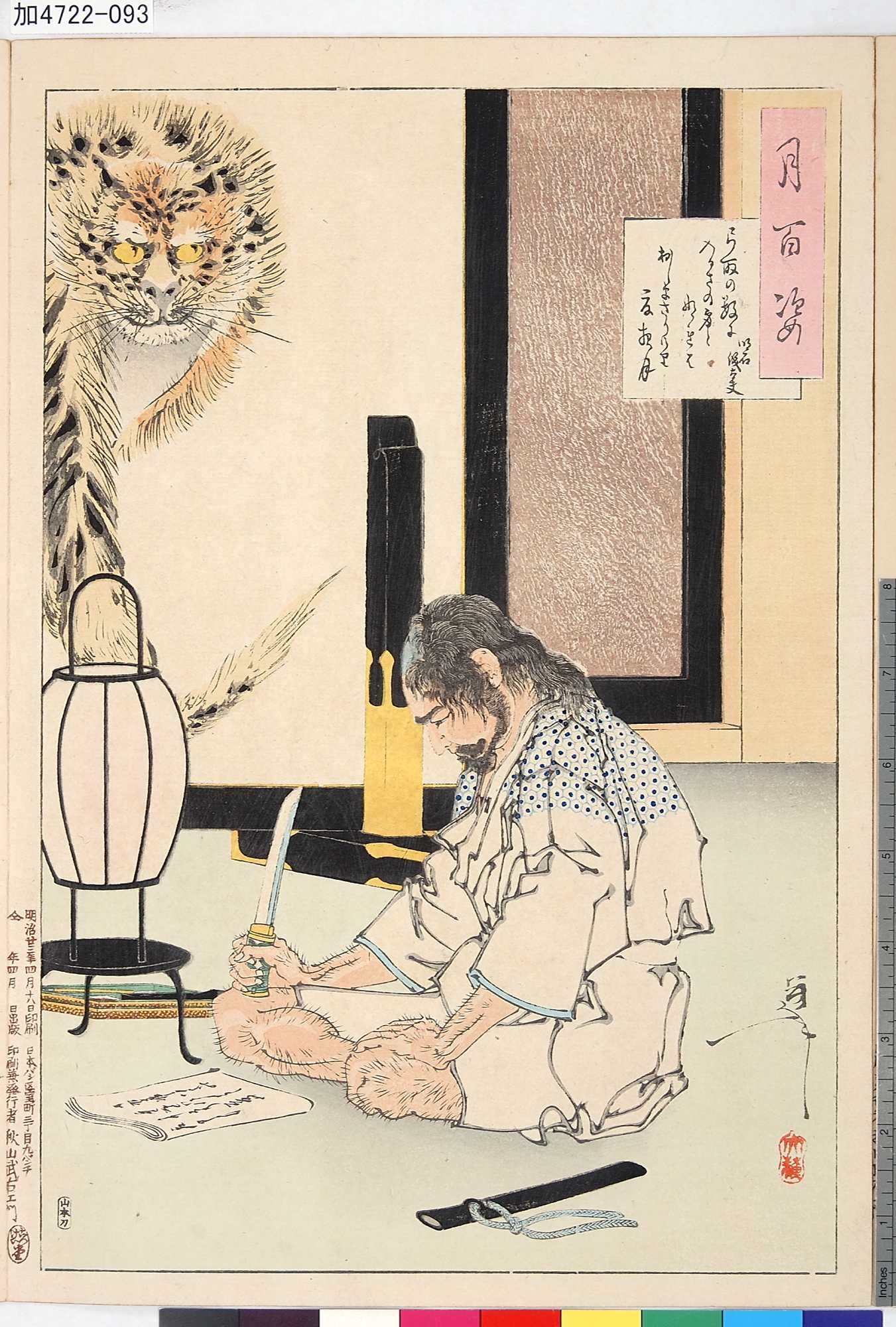

Literature on the subject of ''bushido'' such as ''Hagakure

''Hagakure'' (Kyūjitai: ; Shinjitai: ; meaning ''Hidden by the Leaves'' or ''Hidden Leaves''), or , is a practical and spiritual guide for a warrior, drawn from a collection of commentaries by the clerk Yamamoto Tsunetomo, former retainer to Nab ...

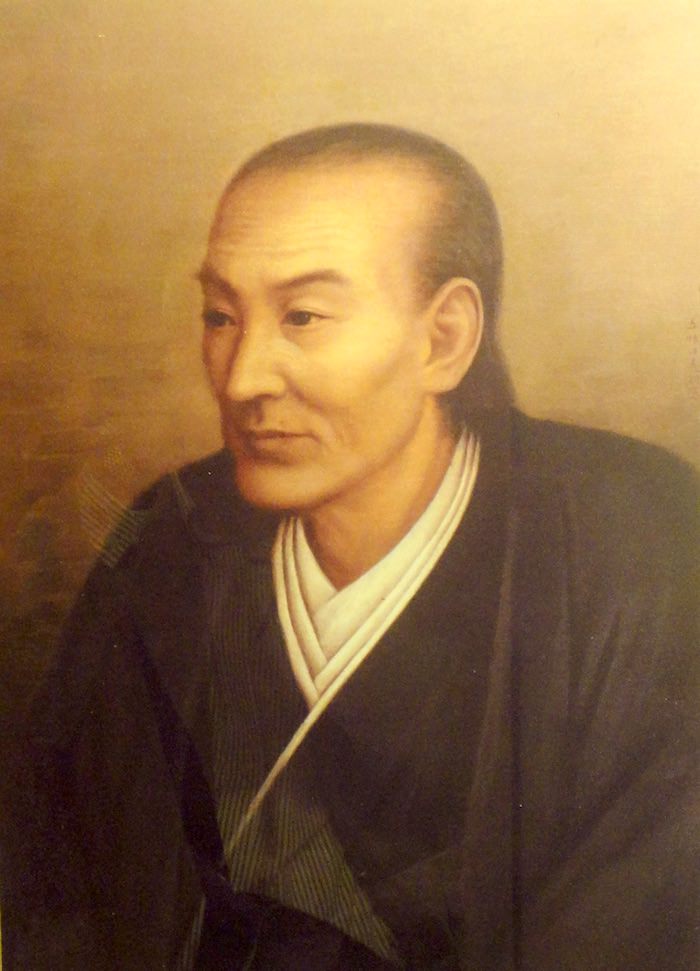

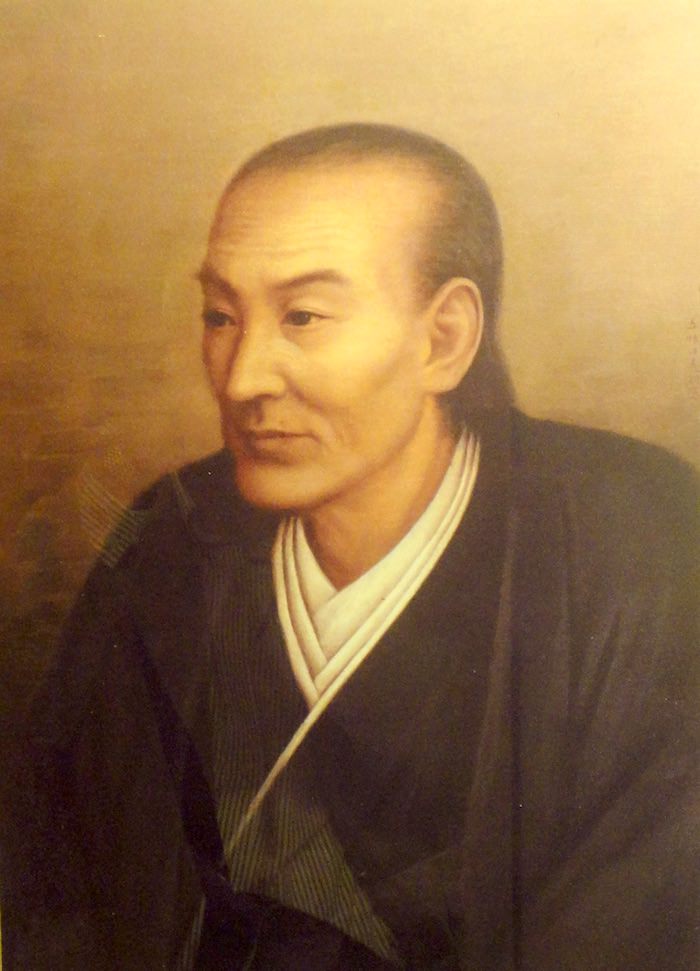

'' ("Hidden in Leaves") by Yamamoto Tsunetomo

, Buddhist monastic name Yamamoto Jōchō (June 11, 1659 – November 30, 1719), was a samurai of the Saga Domain in Hizen Province under his lord Nabeshima Mitsushige. He became a Zen Buddhist priest and relayed his experiences, memories, ...

and '' Gorin no Sho'' ("Book of the Five Rings") by Miyamoto Musashi

, also known as Shinmen Takezō, Miyamoto Bennosuke or, by his Buddhist name, Niten Dōraku, was a Japanese swordsman, philosopher, strategist, writer and rōnin, who became renowned through stories of his unique double-bladed swordsmanship a ...

, both written in the Edo period, contributed to the development of ''bushidō'' and Zen philosophy.

According to Robert Sharf, "The notion that Zen is somehow related to Japanese culture in general, and bushidō in particular, is familiar to Western students of Zen through the writings of D. T. Suzuki, no doubt the single most important figure in the spread of Zen in the West." In an account of Japan sent to Father Ignatius Loyola

Ignatius of Loyola, S.J. (born Íñigo López de Oñaz y Loyola; eu, Ignazio Loiolakoa; es, Ignacio de Loyola; la, Ignatius de Loyola; – 31 July 1556), venerated as Saint Ignatius of Loyola, was a Spanish Catholic priest and theologian, ...

at Rome, drawn from the statements of Anger (Han-Siro's western name), Xavier describes the importance of honor to the Japanese (Letter preserved at College of Coimbra):

In the first place, the nation with which we have had to do here surpasses in goodness any of the nations lately discovered. I really think that among barbarous nations there can be none that has more natural goodness than the Japanese. They are of a kindly disposition, not at all given to cheating, wonderfully desirous of honour and rank. Honour with them is placed above everything else. There are a great many poor among them, but poverty is not a disgrace to any one. There is one thing among them of which I hardly know whether it is practised anywhere among Christians. The nobles, however poor they may be, receive the same honour from the rest as if they were rich.

Doctrine

In the 13th century, Hōjō Shigetoki wrote: "When one is serving officially or in the master's court, he should not think of a hundred or a thousand people, but should consider only the importance of the master."

In the 13th century, Hōjō Shigetoki wrote: "When one is serving officially or in the master's court, he should not think of a hundred or a thousand people, but should consider only the importance of the master." Carl Steenstrup

Carl Steenstrup (1934 – 11 November 2014)) was a Danish japanologist.

Carl Steenstrup is known for translating several works of Japanese literature, mostly those relating to the historical development of Bushido, Japanese Feudal Law, and th ...

notes that 13th- and 14th-century warrior writings ('' gunki'') "portrayed the ''bushi'' in their natural element, war, eulogizing such virtues as reckless bravery, fierce family pride, and selfless, at times senseless devotion of master and man". Feudal lords such as Shiba Yoshimasa (1350–1410) stated that a warrior looked forward to a glorious death in the service of a military leader or the emperor: "It is a matter of regret to let the moment when one should die pass by ... First, a man whose profession is the use of arms should think and then act upon not only his own fame, but also that of his descendants. He should not scandalize his name forever by holding his one and only life too dear ... One's main purpose in throwing away his life is to do so either for the sake of the Emperor or in some great undertaking of a military general. It is that exactly that will be the great fame of one's descendants."

In 1412,

In 1412, Imagawa Sadayo

, also known as , was a renowned Japanese poet and military commander who served as tandai ("constable") of Kyūshū under the Ashikaga bakufu from 1371 to 1395. His father, Imagawa Norikuni, had been a supporter of the first Ashikaga ''shōgun ...

wrote a letter of admonishment to his brother stressing the importance of duty to one's master. Imagawa was admired for his balance of military and administrative skills during his lifetime, and his writings became widespread. The letters became central to Tokugawa-era laws and became required study material for traditional Japanese until World War II:

"First of all, a samurai who dislikes battle and has not put his heart in the right place even though he has been born in the house of the warrior, should not be reckoned among one's retainers ... It is forbidden to forget the great debt of kindness one owes to his master and ancestors and thereby make light of the virtues of loyalty and filial piety ... It is forbidden that one should ... attach little importance to his duties to his master ... There is a primary need to distinguish loyalty from disloyalty and to establish rewards and punishments."

Similarly, the feudal lord Takeda Nobushige

was a samurai of Japan's Sengoku period, and younger brother of Takeda Shingen.

He was known as one of the "Twenty-Four Generals of Takeda Shingen".

Takeda Nobushige held the favor of their father, and was meant to inherit the Takeda lands, we ...

(1525–1561) stated: "In matters both great and small, one should not turn his back on his master's commands ... One should not ask for gifts or enfiefments from the master ... No matter how unreasonably the master may treat a man, he should not feel disgruntled ... An underling does not pass judgments on a superior."

Nobushige's brother Takeda Shingen

, of Kai Province, was a pre-eminent ''daimyō'' in feudal Japan. Known as the "Tiger of Kai", he was one of the most powerful daimyō with exceptional military prestige in the late stage of the Sengoku period.

Shingen was a warlord of great ...

(1521–1573) also made similar observations: "One who was born in the house of a warrior, regardless of his rank or class, first acquaints himself with a man of military feats and achievements in loyalty ... Everyone knows that if a man doesn't hold filial piety toward his own parents he would also neglect his duties toward his lord. Such a neglect means a disloyalty toward humanity. Therefore such a man doesn't deserve to be called 'samurai'."

The feudal lord Asakura Yoshikage