Protein Ligand on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

BioLiP

/ref> is a comprehensive ligand–protein interaction database, with the 3D structure of the ligand–protein interactions taken from the Protein Data Bank

MANORAA

is a webserver for analyzing conserved and differential molecular interaction of the ligand in complex with protein structure homologs from the Protein Data Bank. It provides the linkage to protein targets such as its location in the biochemical pathways, SNPs and protein/RNA baseline expression in target organ.

Configuration integral (statistical mechanics)

2008. This wiki site is down; se

this article in the Internet Archive from 2012 April 28

{{Authority control Chelating agents Chemical bonding Coordination chemistry

In

In coordination chemistry

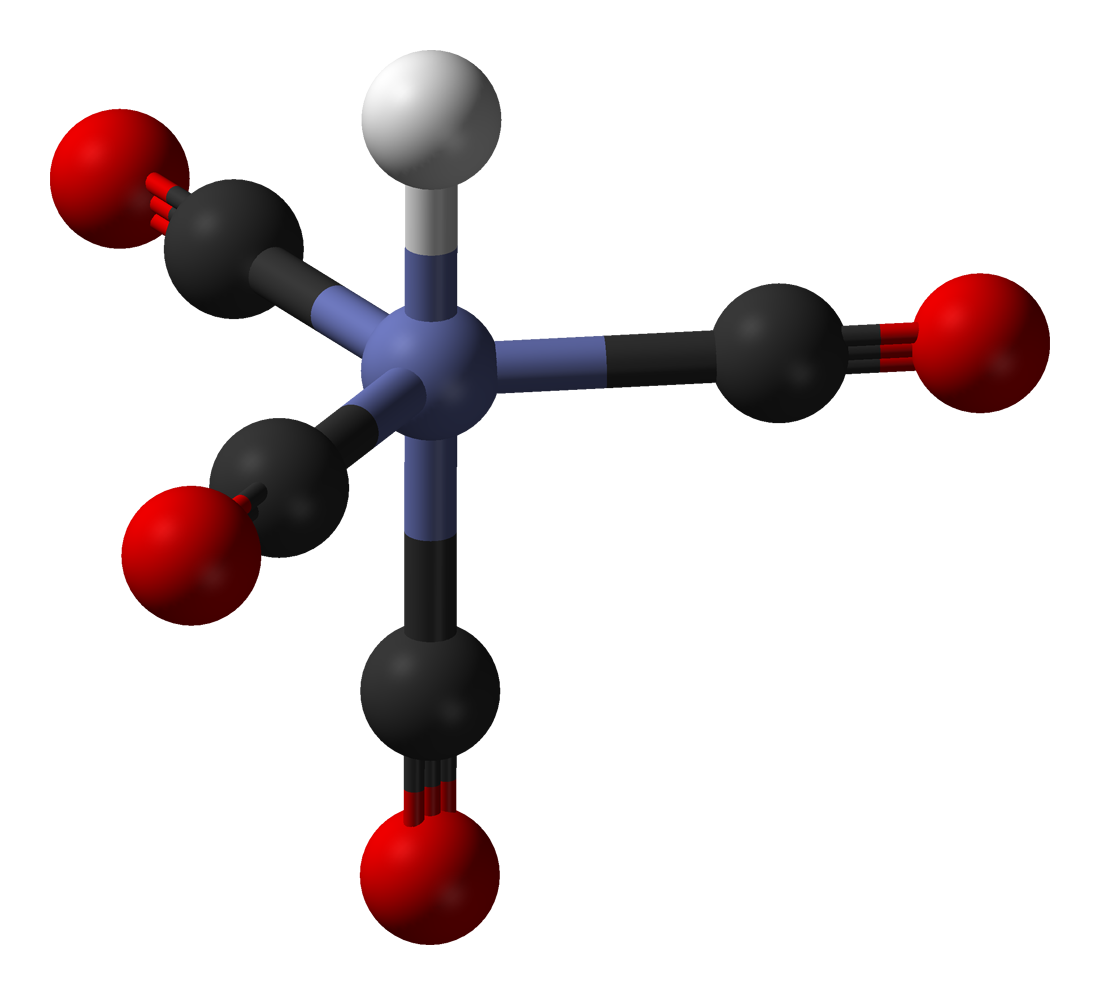

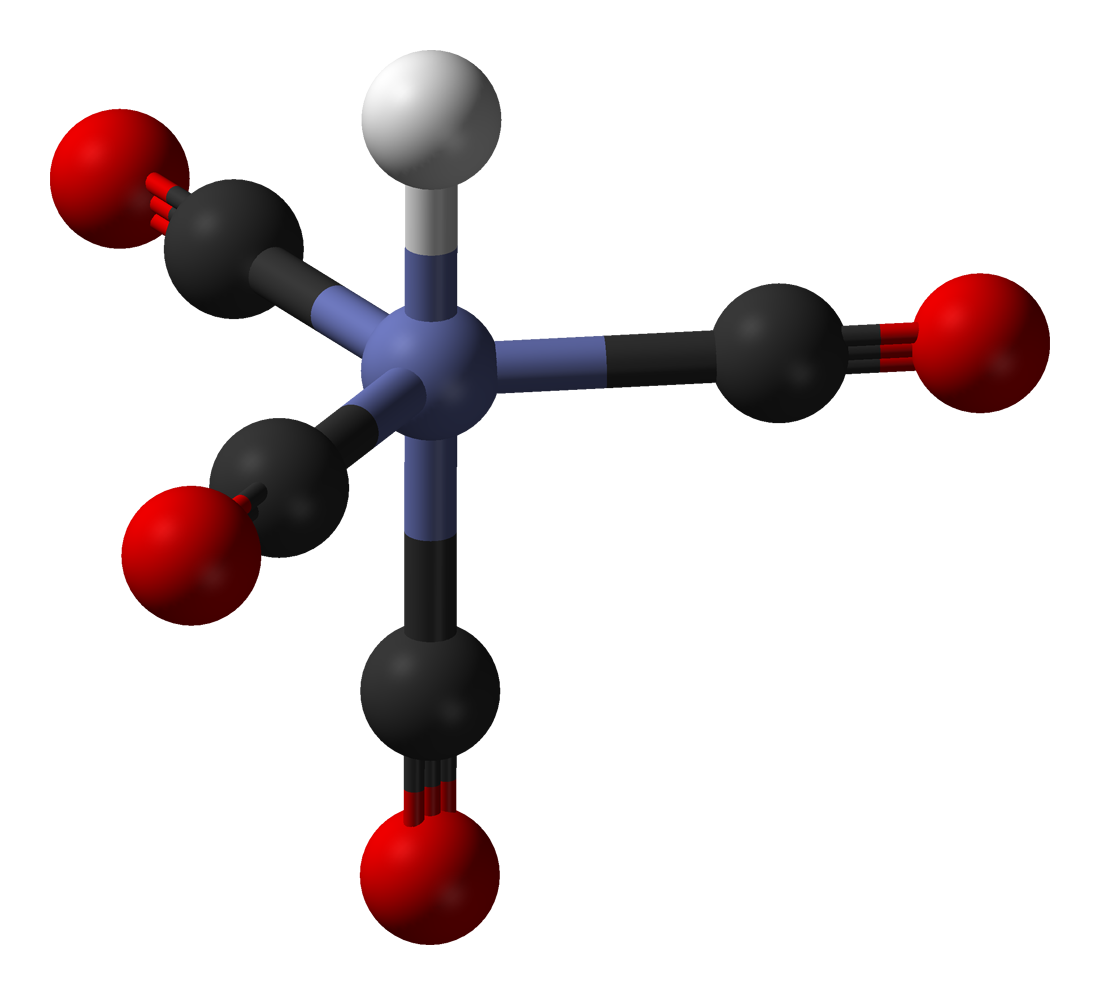

A coordination complex consists of a central atom or ion, which is usually metallic and is called the ''coordination centre'', and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions, that are in turn known as ''ligands'' or complexing agents. Many ...

, a ligand is an ion or molecule ( functional group) that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's electron pairs, often through Lewis bases. The nature of metal–ligand bonding can range from covalent to ionic. Furthermore, the metal–ligand bond order

In chemistry, bond order, as introduced by Linus Pauling, is defined as the difference between the number of bonds and anti-bonds.

The bond order itself is the number of electron pairs (covalent bonds) between two atoms. For example, in diat ...

can range from one to three. Ligands are viewed as Lewis bases, although rare cases are known to involve Lewis acid

A Lewis acid (named for the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis) is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any sp ...

ic "ligands".

Metals and metalloids are bound to ligands in almost all circumstances, although gaseous "naked" metal ions can be generated in a high vacuum. Ligands in a complex dictate the reactivity of the central atom, including ligand substitution rates, the reactivity of the ligands themselves, and redox. Ligand selection requires critical consideration in many practical areas, including bioinorganic and medicinal chemistry, homogeneous catalysis, and environmental chemistry.

Ligands are classified in many ways, including: charge, size (bulk), the identity of the coordinating atom(s), and the number of electrons donated to the metal ( denticity or hapticity). The size of a ligand is indicated by its cone angle.

History

The composition of coordination complexes have been known since the early 1800s, such asPrussian blue

Prussian blue (also known as Berlin blue, Brandenburg blue or, in painting, Parisian or Paris blue) is a dark blue pigment produced by oxidation of ferrous ferrocyanide salts. It has the chemical formula Fe CN)">Cyanide.html" ;"title="e(Cyanid ...

and copper vitriol. The key breakthrough occurred when Alfred Werner

Alfred Werner (12 December 1866 – 15 November 1919) was a Swiss chemist who was a student at ETH Zurich and a professor at the University of Zurich. He won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1913 for proposing the octahedral configuration of ...

reconciled formulas and isomer

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formulae – that is, same number of atoms of each element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. Isomerism is existence or possibility of isomers.

Iso ...

s. He showed, among other things, that the formulas of many cobalt(III) and chromium(III) compounds can be understood if the metal has six ligands in an octahedral geometry. The first to use the term "ligand" were Alfred Werner

Alfred Werner (12 December 1866 – 15 November 1919) was a Swiss chemist who was a student at ETH Zurich and a professor at the University of Zurich. He won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1913 for proposing the octahedral configuration of ...

and Carl Somiesky, in relation to silicon chemistry. The theory allows one to understand the difference between coordinated and ionic chloride in the cobalt ammine chlorides and to explain many of the previously inexplicable isomers. He resolved the first coordination complex called hexol

In chemistry, hexol is a cation with formula 6+ — a coordination complex consisting of four cobalt cations in oxidation state +3, twelve ammonia molecules , and six hydroxy anions , with a net charge of +6. The hydroxy groups act as bridges b ...

into optical isomers, overthrowing the theory that chirality

Chirality is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word ''chirality'' is derived from the Greek (''kheir''), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

An object or a system is ''chiral'' if it is distinguishable from ...

was necessarily associated with carbon compounds.

Strong field and weak field ligands

In general, ligands are viewed as electron donors and the metals as electron acceptors, i.e., respectively,Lewis base

A Lewis acid (named for the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis) is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any sp ...

s and Lewis acid

A Lewis acid (named for the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis) is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any sp ...

s. This description has been semi-quantified in many ways, e.g. ECW model. Bonding is often described using the formalisms of molecular orbital theory.

Ligands and metal ions can be ordered in many ways; one ranking system focuses on ligand 'hardness' (see also hard/soft acid/base theory). Metal ions preferentially bind certain ligands. In general, 'hard' metal ions prefer weak field ligands, whereas 'soft' metal ions prefer strong field ligands. According to the molecular orbital theory, the HOMO (Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital) of the ligand should have an energy that overlaps with the LUMO (Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital) of the metal preferential. Metal ions bound to strong-field ligands follow the Aufbau principle

The aufbau principle , from the German ''Aufbauprinzip'' (building-up principle), also called the aufbau rule, states that in the ground state of an atom or ion, electrons fill subshells of the lowest available energy, then they fill subshells o ...

, whereas complexes bound to weak-field ligands follow Hund's rule.

Binding of the metal with the ligands results in a set of molecular orbitals, where the metal can be identified with a new HOMO and LUMO (the orbitals defining the properties and reactivity of the resulting complex) and a certain ordering of the 5 d-orbitals (which may be filled, or partially filled with electrons). In an octahedral environment, the 5 otherwise degenerate d-orbitals split in sets of 3 and 2 orbitals (for a more in-depth explanation, see crystal field theory):

*3 orbitals of low energy: d''xy'', d''xz'' and d''yz'' and

*2 orbitals of high energy: d''z''2 and d''x''2−''y''2.

The energy difference between these 2 sets of d-orbitals is called the splitting parameter, Δo. The magnitude of Δo is determined by the field-strength of the ligand: strong field ligands, by definition, increase Δo more than weak field ligands. Ligands can now be sorted according to the magnitude of Δo (see the table below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

*Bottom (disambiguation)

Bottom may refer to:

Anatomy and sex

* Bottom (BDSM), the partner in a BDSM who takes the passive, receiving, or obedient role, to that of the top or ...

). This ordering of ligands is almost invariable for all metal ions and is called spectrochemical series.

For complexes with a tetrahedral surrounding, the d-orbitals again split into two sets, but this time in reverse order:

*2 orbitals of low energy: d''z''2 and d''x''2−''y''2 and

*3 orbitals of high energy: d''xy'', d''xz'' and d''yz''.

The energy difference between these 2 sets of d-orbitals is now called Δt. The magnitude of Δt is smaller than for Δo, because in a tetrahedral complex only 4 ligands influence the d-orbitals, whereas in an octahedral complex the d-orbitals are influenced by 6 ligands. When the coordination number is neither octahedral nor tetrahedral, the splitting becomes correspondingly more complex. For the purposes of ranking ligands, however, the properties of the octahedral complexes and the resulting Δo has been of primary interest.

The arrangement of the d-orbitals on the central atom (as determined by the 'strength' of the ligand), has a strong effect on virtually all the properties of the resulting complexes. E.g., the energy differences in the d-orbitals has a strong effect in the optical absorption spectra of metal complexes. It turns out that valence electrons occupying orbitals with significant 3 d-orbital character absorb in the 400–800 nm region of the spectrum (UV–visible range). The absorption of light (what we perceive as the color) by these electrons (that is, excitation of electrons from one orbital to another orbital under influence of light) can be correlated to the ground state

The ground state of a quantum-mechanical system is its stationary state of lowest energy; the energy of the ground state is known as the zero-point energy of the system. An excited state is any state with energy greater than the ground state. ...

of the metal complex, which reflects the bonding properties of the ligands. The relative change in (relative) energy of the d-orbitals as a function of the field-strength of the ligands is described in Tanabe–Sugano diagrams.

In cases where the ligand has low energy LUMO, such orbitals also participate in the bonding. The metal–ligand bond can be further stabilised by a formal donation of electron density back to the ligand in a process known as ''back-bonding

In chemistry, π backbonding, also called π backdonation, is when electrons move from an atomic orbital on one atom to an appropriate symmetry antibonding orbital on a ''π-acceptor ligand''. It is especially common in the organometallic chemi ...

.'' In this case a filled, central-atom-based orbital donates density into the LUMO of the (coordinated) ligand. Carbon monoxide is the preeminent example a ligand that engages metals via back-donation. Complementarily, ligands with low-energy filled orbitals of pi-symmetry can serve as pi-donor.

Classification of ligands as L and X

Especially in the area oforganometallic chemistry

Organometallic chemistry is the study of organometallic compounds, chemical compounds containing at least one chemical bond between a carbon atom of an organic molecule and a metal, including alkali, alkaline earth, and transition metals, and so ...

, ligands are classified as L and X (or combinations of the two). The classification scheme – the "CBC Method" for Covalent Bond Classification – was popularized by M.L.H. Green and "is based on the notion that there are three basic types f ligands

F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''.

Hist ...

.. represented by the symbols L, X, and Z, which correspond respectively to 2-electron, 1-electron and 0-electron neutral ligands." Another type of ligand worthy of consideration is the LX ligand which as expected from the used conventional representation will donate three electrons if NVE (Number of Valence Electrons) required. Example is alkoxy ligands( which is regularly known as X ligand too). L ligands are derived from charge-neutral precursors and are represented by amines, phosphines, CO, N2, and alkenes. X ligands typically are derived from anionic precursors such as chloride but includes ligands where salts of anion do not really exist such as hydride and alkyl. Thus, the complex IrCl(CO)(PPh3)2 is classified as an MXL3 complex, since CO and the two PPh3 ligands are classified as Ls. The oxidative addition of H2 to IrCl(CO)(PPh3)2 gives an 18e− ML3X3 product, IrClH2(CO)(PPh3)2. EDTA4− is classified as an L2X4 ligand, as it features four anions and two neutral donor sites. Cp is classified as an L2X ligand.Hartwig, J. F. Organotransition Metal Chemistry, from Bonding to Catalysis; University Science Books: New York, 2010.

Polydentate and polyhapto ligand motifs and nomenclature

Denticity

Denticity (represented by '' κ'') refers to the number of times a ligand bonds to a metal through noncontiguous donor sites. Many ligands are capable of binding metal ions through multiple sites, usually because the ligands havelone pair

In chemistry, a lone pair refers to a pair of valence electrons that are not shared with another atom in a covalent bondIUPAC ''Gold Book'' definition''lone (electron) pair''/ref> and is sometimes called an unshared pair or non-bonding pair. Lone ...

s on more than one atom. Ligands that bind via more than one atom are often termed '' chelating''. A ligand that binds through two sites is classified as '' bidentate'', and three sites as '' tridentate''. The " bite angle" refers to the angle between the two bonds of a bidentate chelate. Chelating ligands are commonly formed by linking donor groups via organic linkers. A classic bidentate ligand is ethylenediamine

Ethylenediamine (abbreviated as en when a ligand) is the organic compound with the formula C2H4(NH2)2. This colorless liquid with an ammonia-like odor is a basic amine. It is a widely used building block in chemical synthesis, with approximately ...

, which is derived by the linking of two ammonia groups with an ethylene (−CH2CH2−) linker. A classic example of a polydentate ligand is the hexadentate

A hexadentate ligand in coordination chemistry

A coordination complex consists of a central atom or ion, which is usually metallic and is called the ''coordination centre'', and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions, that are in turn k ...

chelating agent EDTA, which is able to bond through six sites, completely surrounding some metals. The number of times a polydentate ligand binds to a metal centre is symbolized by "''κn''", where ''n'' indicates the number of sites by which a ligand attaches to a metal. EDTA4−, when it is hexidentate, binds as a ''κ''6-ligand, the amines and the carboxylate oxygen atoms are not contiguous. In practice, the n value of a ligand is not indicated explicitly but rather assumed. The binding affinity of a chelating system depends on the chelating angle or bite angle.

Complexes of polydentate ligands are called ''chelate'' complexes. They tend to be more stable than complexes derived from monodentate ligands. This enhanced stability, called the ''chelate effect'', is usually attributed to effects of entropy, which favors the displacement of many ligands by one polydentate ligand.

Related to the chelate effect is the macrocyclic effect

In coordination chemistry, a stability constant (also called formation constant or binding constant) is an equilibrium constant for the formation of a complex in solution. It is a measure of the strength of the interaction between the reagents tha ...

. A macrocyclic ligand is any large ligand that at least partially surrounds the central atom and bonds to it, leaving the central atom at the centre of a large ring. The more rigid and the higher its denticity, the more inert will be the macrocyclic complex. Heme is an example, in which the iron atom is at the centre of a porphyrin macrocycle, bound to four nitrogen atoms of the tetrapyrrole macrocycle. The very stable dimethylglyoximate complex of nickel is a synthetic macrocycle derived from dimethylglyoxime.

Hapticity

Hapticity (represented by '' η'') refers to the number of ''contiguous'' atoms that comprise a donor site and attach to a metal center. Butadiene forms both ''η''2 and ''η''4 complexes depending on the number of carbon atoms that are bonded to the metal.Ligand motifs

Trans-spanning ligands

Trans-spanning ligands are bidentate ligands that can span coordination positions on opposite sides of a coordination complex.Ambidentate ligand

Unlike polydentate ligands, ambidentate ligands can attach to the central atom in two places. A good example of this is thiocyanate, SCN−, which can attach at either the sulfur atom or the nitrogen atom. Such compounds give rise tolinkage isomerism

In chemistry, linkage isomerism or ambidentate isomerism is a form of isomerism in which certain coordination compounds have the same composition but differ in their metal atom's connectivity to a ligand.

Typical ligands that give rise to linkage ...

. Polyfunctional ligands, see especially proteins, can bond to a metal center through different ligand atoms to form various isomers.

Bridging ligand

A bridging ligand links two or more metal centers. Virtually all inorganic solids with simple formulas arecoordination polymer

A coordination polymer is an inorganic or organometallic polymer structure containing metal cation centers linked by ligands. More formally a coordination polymer is a coordination compound with repeating coordination entities extending in 1, 2, o ...

s, consisting of metal ion centres linked by bridging ligands. This group of materials includes all anhydrous binary metal ion halides and pseudohalides. Bridging ligands also persist in solution. Polyatomic ligands such as carbonate are ambidentate and thus are found to often bind to two or three metals simultaneously. Atoms that bridge metals are sometimes indicated with the prefix " ''μ''". Most inorganic solids are polymers by virtue of the presence of multiple bridging ligands. Bridging ligands, capable of coordinating multiple metal ions, have been attracting considerable interest because of their potential use as building blocks for the fabrication of functional multimetallic assemblies.

Binucleating ligand

Binucleating ligands bind two metal ions. Usually binucleating ligands feature bridging ligands, such as phenoxide, pyrazolate, or pyrazine, as well as other donor groups that bind to only one of the two metal ions.Metal–ligand multiple bond

Some ligands can bond to a metal center through the same atom but with a different number oflone pair

In chemistry, a lone pair refers to a pair of valence electrons that are not shared with another atom in a covalent bondIUPAC ''Gold Book'' definition''lone (electron) pair''/ref> and is sometimes called an unshared pair or non-bonding pair. Lone ...

s. The bond order

In chemistry, bond order, as introduced by Linus Pauling, is defined as the difference between the number of bonds and anti-bonds.

The bond order itself is the number of electron pairs (covalent bonds) between two atoms. For example, in diat ...

of the metal ligand bond can be in part distinguished through the metal ligand bond angle (M−X−R). This bond angle is often referred to as being linear or bent with further discussion concerning the degree to which the angle is bent. For example, an imido ligand in the ionic form has three lone pairs. One lone pair is used as a sigma X donor, the other two lone pairs are available as L-type pi donors. If both lone pairs are used in pi bonds then the M−N−R geometry is linear. However, if one or both these lone pairs is nonbonding then the M−N−R bond is bent and the extent of the bend speaks to how much pi bonding there may be. ''η''1-Nitric oxide can coordinate to a metal center in linear or bent manner.

Spectator ligand

A spectator ligand is a tightly coordinating polydentate ligand that does not participate in chemical reactions but removes active sites on a metal. Spectator ligands influence the reactivity of the metal center to which they are bound.Bulky ligands

Bulky ligands are used to control the steric properties of a metal center. They are used for many reasons, both practical and academic. On the practical side, they influence the selectivity of metal catalysts, e.g., in hydroformylation. Of academic interest, bulky ligands stabilize unusual coordination sites, e.g., reactive coligands or low coordination numbers. Often bulky ligands are employed to simulate the steric protection afforded by proteins to metal-containing active sites. Of course excessive steric bulk can prevent the coordination of certain ligands.

Chiral ligands

Chiral ligands are useful for inducing asymmetry within the coordination sphere. Often the ligand is employed as an optically pure group. In some cases, such as secondary amines, the asymmetry arises upon coordination. Chiral ligands are used in homogeneous catalysis, such as asymmetric hydrogenation.Hemilabile ligands

Hemilabile ligands contain at least two electronically different coordinating groups and form complexes where one of these is easily displaced from the metal center while the other remains firmly bound, a behaviour which has been found to increase the reactivity of catalysts when compared to the use of more traditional ligands.Non-innocent ligand

Non-innocent ligands bond with metals in such a manner that the distribution of electron density between the metal center and ligand is unclear. Describing the bonding of non-innocent ligands often involves writing multipleresonance form

In chemistry, resonance, also called mesomerism, is a way of describing bonding in certain molecules or polyatomic ions by the combination of several contributing structures (or ''forms'', also variously known as ''resonance structures'' or '' ...

s that have partial contributions to the overall state.

Common ligands

Virtually every molecule and every ion can serve as a ligand for (or "coordinate to") metals. Monodentate ligands include virtually all anions and all simple Lewis bases. Thus, thehalide

In chemistry, a halide (rarely halogenide) is a binary chemical compound, of which one part is a halogen atom and the other part is an element or radical that is less electronegative (or more electropositive) than the halogen, to make a fluor ...

s and pseudohalides are important anionic ligands whereas ammonia, carbon monoxide, and water are particularly common charge-neutral ligands. Simple organic species are also very common, be they anionic ( RO− and ) or neutral ( R2O, R2S, R3−''x''NH''x'', and R3P). The steric properties of some ligands are evaluated in terms of their cone angles.

Beyond the classical Lewis bases and anions, all unsaturated molecules are also ligands, utilizing their pi electrons in forming the coordinate bond. Also, metals can bind to the σ bonds in for example silanes, hydrocarbons, and dihydrogen (see also: Agostic interaction).

In complexes of non-innocent ligands, the ligand is bonded to metals via conventional bonds, but the ligand is also redox-active.

Examples of common ligands (by field strength)

In the following table the ligands are sorted by field strength (weak field ligands first): The entries in the table are sorted by field strength, binding through the stated atom (i.e. as a terminal ligand). The 'strength' of the ligand changes when the ligand binds in an alternative binding mode (e.g., when it bridges between metals) or when the conformation of the ligand gets distorted (e.g., a linear ligand that is forced through steric interactions to bind in a nonlinear fashion).Other generally encountered ligands (alphabetical)

In this table other common ligands are listed in alphabetical order.Ligand exchange

A ligand exchange (also ligand substitution) is a type of chemical reaction in which a ligand in a compound is replaced by another. One type of pathway for substitution is the ligand dependent pathway. In organometallic chemistry this can take place via associative substitution or by dissociative substitution.Ligand–protein binding database

BioLiP/ref> is a comprehensive ligand–protein interaction database, with the 3D structure of the ligand–protein interactions taken from the Protein Data Bank

MANORAA

is a webserver for analyzing conserved and differential molecular interaction of the ligand in complex with protein structure homologs from the Protein Data Bank. It provides the linkage to protein targets such as its location in the biochemical pathways, SNPs and protein/RNA baseline expression in target organ.

See also

*Bridging carbonyl

Metal carbonyls are coordination complexes of transition metals with carbon monoxide ligands. Metal carbonyls are useful in organic synthesis and as catalysts or catalyst precursors in homogeneous catalysis, such as hydroformylation and Reppe ch ...

* Crystal field theory

* DNA binding ligand

* Inorganic chemistry

Inorganic chemistry deals with synthesis and behavior of inorganic and organometallic compounds. This field covers chemical compounds that are not carbon-based, which are the subjects of organic chemistry. The distinction between the two disci ...

* Josiphos ligands

* Ligand dependent pathway

* Ligand field theory

* Ligand isomerism

In coordination chemistry, ligand isomerism is a type of structural isomerism in coordination complexes which arises from the presence of ligand

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule (functional group) that binds to a c ...

* Spectrochemical series

Explanatory notes

References

External links

* See the modeling of ligand–receptor–ligand binding in Vu-Quoc, L.Configuration integral (statistical mechanics)

2008. This wiki site is down; se

this article in the Internet Archive from 2012 April 28

{{Authority control Chelating agents Chemical bonding Coordination chemistry