Islamic World on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the

Sunni Islam: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide

"Sunni Islam is the dominant division of the global Muslim community, and throughout history it has made up a substantial majority (85 to 90 percent) of that community." * * and

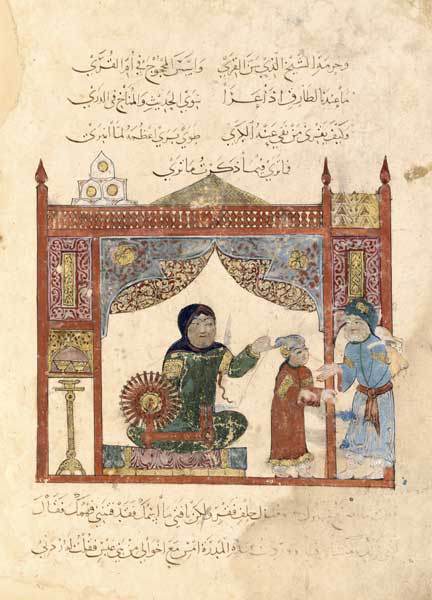

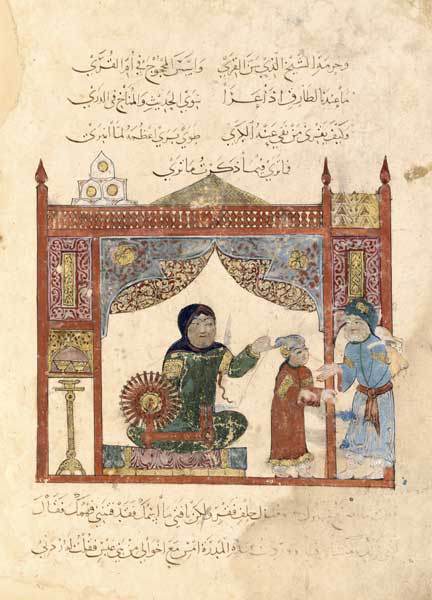

File:Mahmud in robe from the caliph.jpg, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni receiving a richly decorated robe of honor from the caliph al-Qadir in 1000. Miniature from the Rashid al-Din's Jami‘ al-Tawarikh

File:1541-Battle in the war between Shah Isma'il and the King of Shirvan-Shahnama-i-Isma'il.jpg,

The term "

Between the 8th and 18th centuries, the use of

Between the 8th and 18th centuries, the use of

File:Brooklyn Museum - Manuscript of the Hadiqat al-Su`ada (Garden of the Blessed) of Fuzuli - Muhammad bin Sulayman known as Fuzuli2.jpg, ''Hadiqatus-suada'' by Oghuz Turkic poet Fuzûlî

File:Princess Parizade Bringing Home the Singing Tree.jpg, The story of ''Princess Parizade'' and the ''Magic Tree''.

File:Cassim (cropped).jpg, ''Cassim in the Cave'' by

The best known work of fiction from the Islamic world is ''

, ''Encyclopedia of Islamic World''). A Latin translation of Ibn Tufail's work, ''Philosophus Autodidactus'', first appeared in 1671, prepared by Edward Pococke the Younger, followed by an English translation by Simon Ockley in 1708, as well as German and Dutch translations. These translations might have later inspired Daniel Defoe to write '' Robinson Crusoe'', regarded as the first novel in English.Amber Haque (2004), "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists", ''Journal of Religion and Health'' 43 (4): 357–77 69Martin Wainwright

Desert island scripts

, ''

One of the common definitions for "Islamic philosophy" is "the style of philosophy produced within the framework of

One of the common definitions for "Islamic philosophy" is "the style of philosophy produced within the framework of

, ''Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (1998) Islamic philosophy, in this definition is neither necessarily concerned with religious issues, nor is exclusively produced by Muslims. The Persian scholar

In technology, the Muslim world adopted papermaking from China. The knowledge of

In technology, the Muslim world adopted papermaking from China. The knowledge of

Gunpowder Composition for Rockets and Cannon in Arabic Military Treatises In Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries

, ''History of Science and Technology in Islam''. were developed. Advances were made in

Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part II: Transmission Of Islamic Engineering

Such advances made it possible for industrial tasks that were previously driven by manual labour in ancient times to be mechanized and driven by machinery instead in the medieval Islamic world. The transfer of these technologies to medieval Europe had an influence on the

The history of the Islamic faith as a religion and social institution begins with its inception around 610 CE, when the

The history of the Islamic faith as a religion and social institution begins with its inception around 610 CE, when the

File:Bagdad1258.jpg, The city of Baghdad being besieged during the Mongolian invasions.

File:Assassins2-alamut.jpg, Mongol armies capture of the Alamut, Persian miniature.

File:Canonnier Persan. Auguste Wahlen. Moeurs, usages et costumes de tous les peuples du monde. 1843.jpg, Safavid Empire's Zamburak.

File:Bullocks dragging siege-guns up hill during the attack on Ranthambhor Fort.jpg, Bullocks dragging siege-guns up hill during

File:Shah Alam II, Mughal emperor of india, reviewing the East India Companys troops.jpg,

Beginning with the 15th century,

Beginning with the 15th century,

File:Défense de Mazagran.jpg, The French conquest of Algeria, from 1830 to 1903

File:MARIANO FORTUNY - La Batalla de Tetuán (Museo Nacional de Arte de Cataluña, 1862-64. Óleo sobre lienzo, 300 x 972 cm).jpg, The

According to a 2010 study and released January 2011, Islam had 1.5 billion adherents, making up c. 22% of the world population. Because the terms 'Muslim world' and 'Islamic world' are disputed, since no country is homogeneously Muslim, and there is no way to determine at what point a Muslim minority in a country is to be considered 'significant' enough, there is no consensus on how to define the Muslim world geographically. The only rule of thumb for inclusion which has some support, is that countries need to have a Muslim population of more than 50%. According to the Pew Research Center in 2015 there were 50 Muslim-majority countries. Jones (2005) defines a "large minority" as being between 30% and 50%, which described nine countries in 2000, namely

According to a 2010 study and released January 2011, Islam had 1.5 billion adherents, making up c. 22% of the world population. Because the terms 'Muslim world' and 'Islamic world' are disputed, since no country is homogeneously Muslim, and there is no way to determine at what point a Muslim minority in a country is to be considered 'significant' enough, there is no consensus on how to define the Muslim world geographically. The only rule of thumb for inclusion which has some support, is that countries need to have a Muslim population of more than 50%. According to the Pew Research Center in 2015 there were 50 Muslim-majority countries. Jones (2005) defines a "large minority" as being between 30% and 50%, which described nine countries in 2000, namely

In some states, Muslim ethnic groups enjoy considerable autonomy.

In some places, Muslims implement Islamic law, called sharia in Arabic. The Islamic law exists in a number of variations, called schools of jurisprudence. The Amman Message, which was endorsed in 2005 by prominent Islamic scholars around the world, recognized four Sunni schools (

In some states, Muslim ethnic groups enjoy considerable autonomy.

In some places, Muslims implement Islamic law, called sharia in Arabic. The Islamic law exists in a number of variations, called schools of jurisprudence. The Amman Message, which was endorsed in 2005 by prominent Islamic scholars around the world, recognized four Sunni schools (

During much of the 20th century, the Islamic identity and the dominance of Islam on political issues have arguably increased during the early 21st century. The fast-growing interests of the Western world in Islamic regions, international conflicts and

During much of the 20th century, the Islamic identity and the dominance of Islam on political issues have arguably increased during the early 21st century. The fast-growing interests of the Western world in Islamic regions, international conflicts and

File:Muslims perform the Eid Al-Adha prayer at Eyup Sultan Mosque 2019-08-11 21.jpg, Turkish Muslims at the Eyüp Sultan Mosque on

The first centuries of Islam gave rise to three major sects: Sunnis, Shi'as and Kharijites. Each sect developed distinct jurisprudence schools (''

The first centuries of Islam gave rise to three major sects: Sunnis, Shi'as and Kharijites. Each sect developed distinct jurisprudence schools (''

File:Drummer at Hamed el-Nil Mosque (8625532075).jpg, A Sufi dervish drums up the Friday afternoon crowd in Omdurman, Sudan

File:Flickr - Government Press Office (GPO) - Nebi Shueib Festival.jpg,

The Muslim world is home to some of the world's most ancient Christian communities, and some of the most important cities of the Christian world—including three of its five great patriarchates (

The Muslim world is home to some of the world's most ancient Christian communities, and some of the most important cities of the Christian world—including three of its five great patriarchates (

File:Saint Mark Church, Heliopolis.jpg, Egypt has one of the largest Christian population in the Muslim world

File:Shiva temples Dhakeshwari Mandir 2 by Ragib Hasan.jpg, Bangladesh has the largest Hindu population in the Muslim world

File:Yüksekkaldırım Ashkenazi Synagogue.jpg, Turkey has the largest Jewish population in the Muslim world

File:Schoolgirls in Bamozai.JPG, Young school girls in Paktia Province of

According to the

According to the

File:Interlaced-Triangles quasi-Arabesque Brunnian-link.svg, Example of an Arabesque

File:Brunnian-link-12crossings-nonBorromean-quasi-Arabesque.svg, Example of an Arabesque

File:Interlaced-Triangles Brunnian-link alternate.svg, Example of an Arabesque

File:Girih tiles.svg, Girih tiles

File:Darbeimam subdivision rule.svg, The subdivision rule used to generate the Girih pattern on the spandrel.

File:Girih compass straightedge example.svg, Girih pattern that can be drawn with compass and straight edge.

File:Kufic Quran, sura 7, verses 86-87.jpg, Kufic script from an early Qur'an manuscript, 7th century. (Surah 7: 86–87)

File:Bismillah.svg, Bismallah calligraphy.

File:Seven sleepers islam.jpg, Islamic calligraphy represented for amulet of sailors in the

File:Kazakh wedding 3.jpg, A

*Livny, Avital. Trust and the Islamic Advantage: Religious-Based Movements in Turkey and the Muslim World. United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2020.

The Islamic World to 1600

an online tutorial at the University of Calgary, Canada.

Is There a Muslim World?

on NPR

* ttps://ideas.repec.org/b/erv/ebooks/b001.html Why Europe has to offer a better deal towards its Muslim communities. A quantitative analysis of open international data

Indian Ocean in World History, A free online educational resource

{{Authority control Cultural regions Islamic culture Pan-Islamism Historical regions Muslims Regions of Africa Regions of Eurasia

Ummah

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In a modern geopolitical

Geopolitics (from Greek γῆ ''gê'' "earth, land" and πολιτική ''politikḗ'' "politics") is the study of the effects of Earth's geography (human and physical) on politics and international relations. While geopolitics usually refers to ...

sense, these terms refer to countries in which Islam is widespread, although there are no agreed criteria for inclusion. The term Muslim-majority countries is an alternative often used for the latter sense.

The history of the Muslim world spans about 1,400 years and includes a variety of socio-political developments, as well as advances in the arts, science, medicine, philosophy, law, economics and technology, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

. All Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abra ...

look for guidance to the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

and believe in the prophetic mission of the Islamic prophet

Prophets in Islam ( ar, الأنبياء في الإسلام, translit=al-ʾAnbiyāʾ fī al-ʾIslām) are individuals in Islam who are believed to spread God's message on Earth and to serve as models of ideal human behaviour. Some prophets a ...

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

, but disagreements on other matters have led to the appearance of different religious schools of thought and sects within Islam. In the modern era, most of the Muslim world came under European colonial domination. The nation states that emerged in the post-colonial era have adopted a variety of political and economic models, and they have been affected by secular and as well as religious trends.

, the combined GDP (nominal) of 49 Muslim majority countries was US$5.7 trillion. , they contributed 8% of the world's total. In 2020 Economy of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation which consists of 57 member states had combined GDP US$22 trillion or US$ 28 trillion with 5 OIC observer states which is equal about 22% world GDP. As of 2015, 1.8 billion or about 24.1% of the world population are Muslims. By the percentage of the total population in a region considering themselves Muslim, 91% in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

-North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in t ...

( MENA), 89% in Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the former ...

, 40% in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

, 31% in South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;; ...

, 30% in Sub-Saharan Africa, 25% in Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

–Oceania

Oceania (, , ) is a region, geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern Hemisphere, Eastern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of ...

, around 6% in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

, and 1% in the Americas.

Most Muslims are of one of two denominations: Sunni Islam (87-90%)*

Sunni Islam: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide

"Sunni Islam is the dominant division of the global Muslim community, and throughout history it has made up a substantial majority (85 to 90 percent) of that community." * * and

Shia

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the ...

(10-13%).See

*

*

*

* However, other denominations exist in pockets, such as Ibadi (primarily in Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

). About 13% of Muslims live in Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

, the largest Muslim-majority country; % of Muslims live in South Asia, the largest population of Muslims in the world; % in the Middle East–North Africa, where it is the dominant religion; and 15% in Sub-Saharan Africa and West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Mau ...

, incl. Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of G ...

. Muslims are the overwhelming majority in Central Asia, the majority in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

, and widespread in Southeast Asia. India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

has the largest Muslim population outside Muslim-majority countries. Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million pe ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkm ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

are home to second, fourth, sixth and seventh largest Muslim populations. Sizeable Muslim communities are also found in the Americas, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

, China, and Europe. Islam is the fastest-growing major religion in the world. China has the second largest Muslim population outside Muslim-majority countries while Russia has the third largest Muslim population. Nigeria has the largest Muslim population in Africa while Indonesia has the largest Muslim population in Asia.

Terminology

The term has been documented as early as 1912 to encompass the influence of perceived pan-Islamicpropaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loa ...

. ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ...

'' described Pan-Islamism as a movement with power, importance, and cohesion born in Paris, where Turks, Arabs and Persians congregated. The correspondent's focus was on India: it would take too long to consider the progress made in various parts of the Muslim world. The article considered the position of the Amir, the effect of the Tripoli Campaign, Anglo-Russian The Anglo-Russians were an English expatriate business community centred in St Petersburg, then also Moscow, from the 1730s till the 1920s. This community was established against the background of Peter I's recruitment of foreign engineers for his n ...

action in Persia, and "Afghan Ambitions".''Pan-Islamism In India,'' FROM A CORRESPONDENT IN INDIA, Tuesday, 3 September 1912, The Times, Issue: 39994

In a modern geopolitical

Geopolitics (from Greek γῆ ''gê'' "earth, land" and πολιτική ''politikḗ'' "politics") is the study of the effects of Earth's geography (human and physical) on politics and international relations. While geopolitics usually refers to ...

sense, the terms 'Muslim world' and 'Islamic world' refer to countries in which Islam is widespread, although there are no agreed criteria for inclusion. Some scholars and commentators have criticised the term 'Muslim/Islamic world' and its derivative terms 'Muslim/Islamic country' as "simplistic" and "binary", since no state has a religiously homogeneous population (e.g. Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

's citizens are c. 10% Christians), and in absolute numbers, there are sometimes fewer Muslims living in countries in which they make up the majority than in countries in which they form a minority. Hence, the term 'Muslim-majority countries' is often preferred in literature.

Culture

Classical culture

Battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

between Ismail of the Safaviyya and the ruler of Shirvan, Farrukh Yassar

File:Shah Abbas I and Vali Muhammad Khan.jpg, Shah of Safavid Empire Abbas I meet with Vali Muhammad Khan

File:Mir Sayyid Ali - Portrait of a Young Indian Scholar.jpg, Mir Sayyid Ali, a scholar writing a commentary on the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

, during the reign of the Mughal Emperor

The Mughal emperors ( fa, , Pādishāhān) were the supreme heads of state of the Mughal Empire on the Indian subcontinent, mainly corresponding to the modern countries of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh. The Mughal rulers styled ...

Shah Jahan

File:Ottoman Dynasty, Portrait of a Painter, Reign of Mehmet II (1444-1481).jpg, Portrait of a painter during the reign of Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II

File:6 Dust Muhammad. Portrait of Shah Abu'l Ma‘ali. ca. 1556 Aga Khan Collection.jpg, A Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkme ...

n miniature of Shah Abu'l Ma‘ali, a scholar

File:DiezAlbumsStudyingTheKoran.jpg, Ilkhanate Empire ruler, Ghazan, studying the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

File:Laila and Majnun in School, New-York.jpg, Layla and Majnun studying together, from a Persian miniature painting

Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

" has been attributed to a period in history during which science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

, economic development and cultural works in most of the Muslim-dominated world flourished. George Saliba (1994), ''A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam'', pp. 245, 250, 256–7. New York University Press, . The age is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign of the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttal ...

caliph Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, هَارُون الرَشِيد, translit=Hārūn ...

(786–809) with the inauguration of the House of Wisdom in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesipho ...

, where scholars from various parts of the world sought to translate and gather all the known world's knowledge into Arabic, and to have ended with the collapse of the Abbasid caliphate due to Mongol invasions and the Siege of Baghdad in 1258. The Abbasids were influenced by the Quranic injunctions and hadiths, such as "the ink of a scholar is more holy than the blood of a martyr," that stressed the value of knowledge. The major Islamic capital cities of Baghdad, Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo met ...

, and Córdoba Córdoba most commonly refers to:

* Córdoba, Spain, a major city in southern Spain and formerly the imperial capital of Islamic Spain

* Córdoba, Argentina, 2nd largest city in the country and capital of Córdoba Province

Córdoba or Cordoba may ...

became the main intellectual centers for science, philosophy, medicine, and education. During this period, the Muslim world was a collection of cultures; they drew together and advanced the knowledge gained from the ancient Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Roman, Persian, Chinese, Indian, Egyptian, and Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

n civilizations.Vartan Gregorian, "Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith", Brookings Institution Press, 2003, pp. 26–38

Ceramics

Between the 8th and 18th centuries, the use of

Between the 8th and 18th centuries, the use of ceramic glaze

Ceramic glaze is an impervious layer or coating of a vitreous substance which has been fused to a pottery body through firing. Glaze can serve to color, decorate or waterproof an item. Glazing renders earthenware vessels suitable for holdi ...

was prevalent in Islamic art, usually assuming the form of elaborate pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and po ...

. Tin-opacified glazing was one of the earliest new technologies developed by the Islamic potters. The first Islamic opaque glazes can be found as blue-painted ware in Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

, dating to around the 8th century. Another contribution was the development of fritware, originating from 9th-century Iraq. Other centers for innovative ceramic pottery in the Old world included Fustat (from 975 to 1075), Damascus (from 1100 to around 1600) and Tabriz

Tabriz ( fa, تبریز ; ) is a city in northwestern Iran, serving as the capital of East Azerbaijan Province. It is the sixth-most-populous city in Iran. In the Quru River valley in Iran's historic Azerbaijan region between long ridges of vo ...

(from 1470 to 1550).

Literature

Maxfield Parrish

Maxfield Parrish (July 25, 1870 – March 30, 1966) was an American painter and illustrator active in the first half of the 20th century. He is known for his distinctive saturated hues and idealized neo-classical imagery. His career spann ...

.

File:Vasnetsov samolet.jpg, The Magic carpet.

One Thousand and One Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

'' (In Persian: ''hezār-o-yek šab'' > Arabic: ''ʔalf-layl-at-wa-l’-layla''= One thousand Night and (one) Night) or *''Arabian Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

'', a name invented by early Western translators, which is a compilation of folk tales

Oral literature, orature or folk literature is a genre of literature that is spoken or sung as opposed to that which is written, though much oral literature has been transcribed. There is no standard definition, as anthropologists have used vary ...

from Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominalization, nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cul ...

, Persian, and later Arabian fable

Fable is a literary genre: a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are anthropomorphized, and that illustrates or leads to a particular mor ...

s. The original concept is derived from a pre-Islamic Persian prototype ''Hezār Afsān'' (Thousand Fables) that relied on particular Indian elements. It reached its final form by the 14th century; the number and type of tales have varied from one manuscript to another.Grant & Clute, p. 51 All Arabian fantasy tales tend to be called ''Arabian Nights'' stories when translated into English, regardless of whether they appear in '' The Book of One Thousand and One Nights'' or not. This work has been very influential in the West since it was translated in the 18th century, first by Antoine Galland

Antoine Galland (; 4 April 1646 – 17 February 1715) was a French orientalist and archaeologist, most famous as the first European translator of ''One Thousand and One Nights'', which he called '' Les mille et une nuits''. His version of the ta ...

. Imitations were written, especially in France.Grant & Clute, p 52 Various characters from this epic have themselves become cultural icon

A cultural icon is a person or an artifact that is identified by members of a culture as representative of that culture. The process of identification is subjective, and "icons" are judged by the extent to which they can be seen as an authentic s ...

s in Western culture

image:Da Vinci Vitruve Luc Viatour.jpg, Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions, human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise '' ...

, such as Aladdin

Aladdin ( ; ar, علاء الدين, ', , ATU 561, ‘Aladdin') is a Middle-Eastern folk tale. It is one of the best-known tales associated with ''The Book of One Thousand and One Nights'' (''The Arabian Nights''), despite not being part o ...

, Sinbad the Sailor

Sinbad the Sailor (; ar, سندباد البحري, Sindibādu al-Bahriyy; fa, سُنباد بحری, Sonbād-e Bahri or Sindbad) is a fictional mariner and the hero of a story-cycle of Persian origin. He is described as hailing from Baghda ...

and Ali Baba.

A famous example of Arabic poetry

Arabic poetry ( ar, الشعر العربي ''ash-shi‘ru al-‘Arabīyyu'') is the earliest form of Arabic literature. Present knowledge of poetry in Arabic dates from the 6th century, but oral poetry is believed to predate that.

Arabic poetry ...

and Persian poetry on romance (love)

Romance or romantic love is a feeling of love for, or a Interpersonal attraction, strong attraction towards another person, and the Courtship, courtship behaviors undertaken by an individual to express those overall feelings and resultant emot ...

is '' Layla and Majnun'', dating back to the Umayyad era in the 7th century. It is a tragic story of undying love. Ferdowsi's ''Shahnameh

The ''Shahnameh'' or ''Shahnama'' ( fa, شاهنامه, Šāhnāme, lit=The Book of Kings, ) is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50 ...

'', the national epic of Greater Iran

Greater Iran ( fa, ایران بزرگ, translit=Irān-e Bozorg) refers to a region covering parts of Western Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, Xinjiang, and the Caucasus, where both Iranian culture and Iranian languages have had ...

, is a mythical and heroic retelling of Persian history. '' Amir Arsalan'' was also a popular mythical Persian story, which has influenced some modern works of fantasy fiction, such as '' The Heroic Legend of Arslan''.

Ibn Tufail (Abubacer) and Ibn al-Nafis were pioneers of the philosophical novel. Ibn Tufail wrote the first Arabic novel '' Hayy ibn Yaqdhan'' (''Philosophus Autodidactus

''Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān'' () is an Arabic philosophical novel and an allegorical tale written by Ibn Tufail (c. 1105 – 1185) in the early 12th century in Al-Andalus. Names by which the book is also known include the ('The Self-Taught Phi ...

'') as a response to Al-Ghazali's '' The Incoherence of the Philosophers'', and then Ibn al-Nafis also wrote a novel ''Theologus Autodidactus

''Theologus Autodidactus'' ("The Self-taught Theologian"), originally titled ''The Treatise of Kāmil on the Prophet's Biography'' ( ar, الرسالة الكاملية في السيرة النبوية), also known as ''Risālat Fādil ibn Nātiq'' ...

'' as a response to Ibn Tufail's ''Philosophus Autodidactus''. Both of these narratives had protagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a st ...

s (Hayy in ''Philosophus Autodidactus'' and Kamil in ''Theologus Autodidactus

''Theologus Autodidactus'' ("The Self-taught Theologian"), originally titled ''The Treatise of Kāmil on the Prophet's Biography'' ( ar, الرسالة الكاملية في السيرة النبوية), also known as ''Risālat Fādil ibn Nātiq'' ...

'') who were autodidactic feral children living in seclusion on a desert island

A desert island, deserted island, or uninhabited island, is an island, islet or atoll that is not permanently populated by humans. Uninhabited islands are often depicted in films or stories about shipwrecked people, and are also used as stereo ...

, both being the earliest examples of a desert island story. However, while Hayy lives alone with animals on the desert island for the rest of the story in ''Philosophus Autodidactus'', the story of Kamil extends beyond the desert island setting in ''Theologus Autodidactus'', developing into the earliest known coming of age plot and eventually becoming the first example of a science fiction novel.

''Theologus Autodidactus'', written by the Arabian polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288), is the first example of a science fiction novel. It deals with various science fiction elements such as spontaneous generation, futurology, the end of the world and doomsday, resurrection

Resurrection or anastasis is the concept of coming back to life after death. In a number of religions, a dying-and-rising god is a deity which dies and is resurrected. Reincarnation is a similar process hypothesized by other religions, whic ...

, and the afterlife. Rather than giving supernatural or mythological explanations for these events, Ibn al-Nafis attempted to explain these plot elements using the scientific knowledge of biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditar ...

, astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosophe ...

and geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ea ...

known in his time. Ibn al-Nafis' fiction explained Islamic religious teachings via science and Islamic philosophy

Islamic philosophy is philosophy that emerges from the Islamic tradition. Two terms traditionally used in the Islamic world are sometimes translated as philosophy—falsafa (literally: "philosophy"), which refers to philosophy as well as logic ...

.Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), "Ibn Al-Nafis as a philosopher", ''Symposium on Ibn al Nafis'', Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait ( cf.br>Ibnul-Nafees As a Philosopher, ''Encyclopedia of Islamic World''). A Latin translation of Ibn Tufail's work, ''Philosophus Autodidactus'', first appeared in 1671, prepared by Edward Pococke the Younger, followed by an English translation by Simon Ockley in 1708, as well as German and Dutch translations. These translations might have later inspired Daniel Defoe to write '' Robinson Crusoe'', regarded as the first novel in English.Amber Haque (2004), "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists", ''Journal of Religion and Health'' 43 (4): 357–77 69Martin Wainwright

Desert island scripts

, ''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide ...

'', 22 March 2003. ''Philosophus Autodidactus'', continuing the thoughts of philosophers such as Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

from earlier ages, inspired Robert Boyle to write his own philosophical novel set on an island, ''The Aspiring Naturalist''.

Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His '' Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ...

's ''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' ( it, Divina Commedia ) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun 1308 and completed in around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature a ...

'', derived features of and episodes about '' Bolgia'' from Arabic works on Islamic eschatology: the ''Hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

'' and the '' Kitab al-Miraj'' (translated into Latin in 1264 or shortly beforeI. Heullant-Donat and M.-A. Polo de Beaulieu, "Histoire d'une traduction," in ''Le Livre de l'échelle de Mahomet'', Latin edition and French translation by Gisèle Besson and Michèle Brossard-Dandré, Collection ''Lettres Gothiques'', Le Livre de Poche, 1991, p. 22 with note 37. as ''Liber scalae Machometi

The ''Book of Muḥammad's Ladder'' is a first-person account of the Islamic prophet Muḥammad's night journey ('' isrāʾ'') and ascent to heaven ('' miʿrāj''), translated into Latin (as ) and Old French (as ) from traditional Arabic materials ...

'') concerning the ascension to Heaven of Muhammad, and the spiritual writings of Ibn Arabi. The Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct o ...

also had a noticeable influence on the works of George Peele and William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

. Some of their works featured Moorish characters, such as Peele's '' The Battle of Alcazar'' and Shakespeare's ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as ...

'', ''Titus Andronicus

''Titus Andronicus'' is a tragedy by William Shakespeare believed to have been written between 1588 and 1593, probably in collaboration with George Peele. It is thought to be Shakespeare's first tragedy and is often seen as his attempt to emul ...

'' and '' Othello'', which featured a Moorish Othello as its title character. These works are said to have been inspired by several Moorish delegations from Morocco to Elizabethan England at the beginning of the 17th century.

Philosophy

One of the common definitions for "Islamic philosophy" is "the style of philosophy produced within the framework of

One of the common definitions for "Islamic philosophy" is "the style of philosophy produced within the framework of Islamic culture

Islamic culture and Muslim culture refer to cultural practices which are common to historically Islamic people. The early forms of Muslim culture, from the Rashidun Caliphate to the early Umayyad period and the early Abbasid period, were pre ...

.""Islamic Philosophy", ''Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (1998) Islamic philosophy, in this definition is neither necessarily concerned with religious issues, nor is exclusively produced by Muslims. The Persian scholar

Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

(Avicenna) (980–1037) had more than 450 books attributed to him. His writings were concerned with various subjects, most notably philosophy and medicine. His medical textbook '' The Canon of Medicine'' was used as the standard text in European universities for centuries. He also wrote '' The Book of Healing'', an influential scientific and philosophical encyclopedia.

One of the most influential Muslim philosophers in the West was Averroes (Ibn Rushd), founder of the Averroism

Averroism refers to a school of medieval philosophy based on the application of the works of 12th-century Al-Andalus, Andalusian Islamic philosophy, philosopher Averroes, (known in his time in Arabic as ابن رشد, ibn Rushd, 1126–1198) a co ...

school of philosophy, whose works and commentaries affected the rise of secular thought in Europe.Majid Fakhry (2001). ''Averroes: His Life, Works and Influence''. Oneworld Publications. . He also developed the concept of " existence precedes essence".

Another figure from the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

, Avicenna, also founded his own Avicennism school of philosophy, which was influential in both Islamic and Christian lands. He was also a critic of Aristotelian logic and founder of Avicennian logic, developed the concepts of empiricism and tabula rasa, and distinguished between essence and existence

Existence is the ability of an entity to interact with reality. In philosophy, it refers to the ontological property of being.

Etymology

The term ''existence'' comes from Old French ''existence'', from Medieval Latin ''existentia/exsistenti ...

.

Yet another influential philosopher who had an influence on modern philosophy was Ibn Tufail. His philosophical novel, '' Hayy ibn Yaqdha'', translated into Latin as ''Philosophus Autodidactus'' in 1671, developed the themes of empiricism, tabula rasa, nature versus nurture, condition of possibility, materialism, and Molyneux's problem

Molyneux's problem is a thought experiment in philosophy concerning immediate recovery from blindness. It was first formulated by William Molyneux, and notably referred to in John Locke's '' An Essay Concerning Human Understanding'' (1689). Th ...

. European scholars and writers influenced by this novel include John Locke, Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mat ...

, Melchisédech Thévenot, John Wallis, Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists ...

, George Keith, Robert Barclay

Robert Barclay (23 December 16483 October 1690) was a Scottish Quaker, one of the most eminent writers belonging to the Religious Society of Friends and a member of the Clan Barclay. He was a son of Col. David Barclay, Laird of Urie, and his ...

, the Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

, and Samuel Hartlib. G. J. Toomer (1996), ''Eastern Wisedome and Learning: The Study of Arabic in Seventeenth-Century England'', p. 222, Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print book ...

, .

Islamic philosophers continued making advances in philosophy through to the 17th century, when Mulla Sadra founded his school of Transcendent theosophy and developed the concept of existentialism

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning

Meaning most comm ...

.

Other influential Muslim philosophers include al-Jahiz, a pioneer in evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary thought; Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

(Alhazen), a pioneer of phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (philosophy), a branch of philosophy which studies subjective experiences and a ...

and the philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is a branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. The central questions of this study concern what qualifies as science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ulti ...

and a critic of Aristotelian natural philosophy and Aristotle's concept of place (topos); Al-Biruni, a critic of Aristotelian natural philosophy; Ibn Tufail and Ibn al-Nafis, pioneers of the philosophical novel; Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi, founder of Illuminationist philosophy; Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, a critic of Aristotelian logic and a pioneer of inductive logic; and Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, o ...

, a pioneer in the philosophy of history.Dr. S.R.W. Akhtar (1997). "The Islamic Concept of Knowledge", ''Al-Tawhid: A Quarterly Journal of Islamic Thought & Culture'' 12 (3).

Sciences

Muslim scientists placed far greater emphasis on experiment than theGreeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, Albania, Greeks in Italy, ...

. This led to an early scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article hist ...

being developed in the Muslim world, where progress in methodology was made, beginning with the experiments of Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) on optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultra ...

from ''circa'' 1000, in his '' Book of Optics''. The most important development of the scientific method was the use of experiments to distinguish between competing scientific theories set within a generally empirical orientation, which began among Muslim scientists. Ibn al-Haytham is also regarded as the father of optics, especially for his empirical proof of the intromission theory

Visual perception is the ability to interpret the surrounding environment through photopic vision (daytime vision), color vision, scotopic vision (night vision), and mesopic vision (twilight vision), using light in the visible spectrum refle ...

of light. Jim Al-Khalili stated in 2009 that Ibn al-Haytham is 'often referred to as the "world's first true scientist".' al-Khwarzimi

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī ( ar, محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي, Muḥammad ibn Musā al-Khwārazmi; ), or al-Khwarizmi, was a Persian polymath from Khwarazm, who produced vastly influential works in mathematics, astro ...

's invented the log base systems that are being used today, he also contributed theorems in trigonometry as well as limits. Recent studies show that it is very likely that the Medieval Muslim artists were aware of advanced decagonal quasicrystal geometry (discovered half a millennium later in the 1970s and 1980s in the West) and used it in intricate decorative tilework in the architecture.

Muslim physicians contributed to the field of medicine, including the subjects of anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

and physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemic ...

: such as in the 15th-century Persian work by Mansur ibn Muhammad ibn al-Faqih Ilyas entitled ''Tashrih al-badan'' (''Anatomy of the body'') which contained comprehensive diagrams of the body's structural, nervous and circulatory system

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

s; or in the work of the Egyptian physician Ibn al-Nafis, who proposed the theory of pulmonary circulation. Avicenna's ''The Canon of Medicine'' remained an authoritative medical textbook in Europe until the 18th century. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (also known as ''Abulcasis'') contributed to the discipline of medical surgery with his '' Kitab al-Tasrif'' ("Book of Concessions"), a medical encyclopedia which was later translated to Latin and used in European and Muslim medical schools for centuries. Other medical advancements came in the fields of pharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemi ...

and pharmacy

Pharmacy is the science and practice of discovering, producing, preparing, dispensing, reviewing and monitoring medications, aiming to ensure the safe, effective, and affordable use of medication, medicines. It is a miscellaneous science as it ...

.

In astronomy, Muḥammad ibn Jābir al-Ḥarrānī al-Battānī

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Jābir ibn Sinān al-Raqqī al-Ḥarrānī aṣ-Ṣābiʾ al-Battānī ( ar, محمد بن جابر بن سنان البتاني) ( Latinized as Albategnius, Albategni or Albatenius) (c. 858 – 929) was an astron ...

improved the precision of the measurement of the precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In o ...

of the Earth's axis. The corrections made to the geocentric model by al-Battani, Averroes, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Mu'ayyad al-Din al-'Urdi and Ibn al-Shatir were later incorporated into the Copernican heliocentric model. Heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth ...

theories were also discussed by several other Muslim astronomers such as Al-Biruni, Al-Sijzi, Qotb al-Din Shirazi, and Najm al-Dīn al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī Najm al-Dīn 'Alī ibn 'Umar al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī (died AH 675 / 1276 CE) was a Persian Islamic philosopher and logician of the Shafi`i school. A student of Athīr al-Dīn al-Abharī. His most important works are a treatise on logic, ''Al-Risa ...

. The astrolabe

An astrolabe ( grc, ἀστρολάβος ; ar, ٱلأَسْطُرلاب ; persian, ستارهیاب ) is an ancient astronomical instrument that was a handheld model of the universe. Its various functions also make it an elaborate incli ...

, though originally developed by the Greeks, was perfected by Islamic astronomers and engineers, and was subsequently brought to Europe.

Some most famous scientists from the medieval Islamic world include Jābir ibn Hayyān, al-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a renowned early Is ...

, Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi, Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

, Al-Biruni, Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islam ...

, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, and Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, o ...

.

Technology

In technology, the Muslim world adopted papermaking from China. The knowledge of

In technology, the Muslim world adopted papermaking from China. The knowledge of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate ( saltpeter) ...

was also transmitted from China via predominantly Islamic countries, where formulas for pure potassium nitrate Ahmad Y. al-HassanGunpowder Composition for Rockets and Cannon in Arabic Military Treatises In Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries

, ''History of Science and Technology in Islam''. were developed. Advances were made in

irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has been dev ...

and farming, using new technology such as the windmill

A windmill is a structure that converts wind power into rotational energy using vanes called sails or blades, specifically to mill grain (gristmills), but the term is also extended to windpumps, wind turbines, and other applications, in so ...

. Crops such as almonds and citrus

''Citrus'' is a genus of flowering trees and shrubs in the rue family, Rutaceae. Plants in the genus produce citrus fruits, including important crops such as oranges, lemons, grapefruits, pomelos, and limes. The genus ''Citrus'' is nati ...

fruit were brought to Europe through al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the Mus ...

, and sugar cultivation was gradually adopted by the Europeans. Arab merchants dominated trade in the Indian Ocean until the arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century. Hormuz was an important center for this trade. There was also a dense network of trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over bodies of water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a sin ...

s in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on th ...

, along which Muslim-majority countries traded with each other and with European powers such as Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

, Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Regions of Italy, Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of t ...

and Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

. The Silk Road crossing Central Asia passed through Islamic states between China and Europe. The emergence of major economic empires with technological resources after the conquests of Timur

Timur ; chg, ''Aqsaq Temür'', 'Timur the Lame') or as ''Sahib-i-Qiran'' ( 'Lord of the Auspicious Conjunction'), his epithet. ( chg, ''Temür'', 'Iron'; 9 April 133617–19 February 1405), later Timūr Gurkānī ( chg, ''Temür Kür ...

(Tamerlane) and the resurgence of the Timurid Renaissance include the Mali Empire and the India's Bengal Sultanate in particular, a major global trading nation in the world, described by the Europeans to be the "richest country to trade with".

Muslim engineers in the Islamic world made a number of innovative industrial uses of hydropower

Hydropower (from el, ὕδωρ, "water"), also known as water power, is the use of falling or fast-running water to produce electricity or to power machines. This is achieved by converting the gravitational potential or kinetic energy of ...

, and early industrial uses of tidal power and wind power, fossil fuels such as petroleum, and early large factory complexes (''tiraz'' in Arabic). The industrial uses of watermills in the Islamic world date back to the 7th century, while horizontal-wheeled

A wheel is a circular component that is intended to rotate on an axle bearing. The wheel is one of the key components of the wheel and axle which is one of the six simple machines. Wheels, in conjunction with axles, allow heavy objects to be ...

and vertical-wheeled water mills were both in widespread use since at least the 9th century. A variety of industrial mills were being employed in the Islamic world, including early fulling mills, gristmill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separated ...

s, paper mills, hullers, sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logging, logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes ...

s, ship mills, stamp mills, steel mills, sugar mills

A sugar cane mill is a factory that processes sugar cane to produce raw or white sugar.

The term is also used to refer to the equipment that crushes the sticks of sugar cane to extract the juice.

Processing

There are a number of steps in prod ...

, tide mills and windmills. By the 11th century, every province throughout the Islamic world had these industrial mills in operation, from al-Andalus and North Africa to the Middle East and Central Asia.Adam Robert Lucas (2005), "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds: A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe", ''Technology and Culture'' 46 (1), pp. 1–30 0 Muslim engineers also invented crankshafts and water turbines, employed gear

A gear is a rotating circular machine part having cut teeth or, in the case of a cogwheel or gearwheel, inserted teeth (called ''cogs''), which mesh with another (compatible) toothed part to transmit (convert) torque and speed. The basic p ...

s in mills and water-raising machines, and pioneered the use of dams as a source of water power, used to provide additional power to watermills and water-raising machines. Ahmad Y. al-HassanTransfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part II: Transmission Of Islamic Engineering

Such advances made it possible for industrial tasks that were previously driven by manual labour in ancient times to be mechanized and driven by machinery instead in the medieval Islamic world. The transfer of these technologies to medieval Europe had an influence on the

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, particularly from the proto-industrialised Mughal Bengal and Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan (born Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, 1 December 1751 – 4 May 1799), also known as the Tiger of Mysore, was the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India. He was a pioneer of rocket artillery.Dalrymple, p. 243 He in ...

's Kingdom, through the conquests of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sout ...

.

History

The history of the Islamic faith as a religion and social institution begins with its inception around 610 CE, when the

The history of the Islamic faith as a religion and social institution begins with its inception around 610 CE, when the Islamic prophet

Prophets in Islam ( ar, الأنبياء في الإسلام, translit=al-ʾAnbiyāʾ fī al-ʾIslām) are individuals in Islam who are believed to spread God's message on Earth and to serve as models of ideal human behaviour. Some prophets a ...

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

, a native of Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow val ...

, is believed by Muslims to have received the first revelation of the Quran, and began to preach his message. In 622 CE, facing opposition in Mecca, he and his followers migrated to Yathrib (now Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

), where he was invited to establish a new constitution for the city under his leadership. This migration, called the Hijra, marks the first year of the Islamic calendar

The Hijri calendar ( ar, ٱلتَّقْوِيم ٱلْهِجْرِيّ, translit=al-taqwīm al-hijrī), also known in English as the Muslim calendar and Islamic calendar, is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 lunar months in a year of 354 ...

. By the time of his death, Muhammad had become the political and spiritual leader of Medina, Mecca, the surrounding region, and numerous other tribes in the Arabian Peninsula.

After Muhammad died in 632, his successors (the Caliphs) continued to lead the Muslim community based on his teachings and guidelines of the Quran. The majority of Muslims consider the first four successors to be 'rightly guided' or Rashidun. The conquests of the Rashidun Caliphate helped to spread Islam beyond the Arabian Peninsula, stretching from northwest India, across Central Asia, the Near East, North Africa, southern Italy, and the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

, to the Pyrenees. The Arab Muslims were unable to conquer the entire Christian Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

in Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

during the Arab–Byzantine wars, however. The succeeding Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

attempted two failed sieges of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

in 674–678 and 717–718. Meanwhile, the Muslim community tore itself apart into the rivalling Sunni and Shia sects since the killing of caliph Uthman in 656, resulting in a succession crisis that has never been resolved. The following First, Second and Third Fitnas and finally the Abbasid Revolution (746–750) also definitively destroyed the political unity of the Muslims, who have been inhabiting multiple states ever since. Ghaznavids' rule was succeeded by the Ghurid Empire of Muhammad of Ghor and Ghiyath al-Din Muhammad, whose reigns under the leadership of Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji extended until the Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

, where Indian Islamic missionaries achieved their greatest success in terms of dawah

Dawah ( ar, دعوة, lit=invitation, ) is the act of inviting or calling people to embrace Islam. The plural is ''da‘wāt'' (دَعْوات) or ''da‘awāt'' (دَعَوات).

Etymology

The English term ''Dawah'' derives from the Arabic ...

and number of converts to Islam. Qutb-ud-din Aybak conquered Delhi in 1206 and began the reign of the Delhi Sultanate, a successive series of dynasties that synthesized Indian civilization with the wider commercial and cultural networks of Africa and Eurasia, greatly increased demographic and economic growth in India and deterred Mongol incursion into the prosperous Indo-Gangetic Plain and enthroned one of the few female Muslim rulers, Razia Sultana.

Notable major empires dominated by Muslims, such as those of the Abbasids, Fatimids, Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that ...

, Seljukids, Ajuran Ajuran may refer to:

* Ajuran Sultanate, a medieval Somali empire

* Ajuran (clan), a Somali clan

* Ajuran currency Ajuran currency was an old coinage system minted in the Ajuran Sultanate. The polity was a Somali people, Somali Muslim kingdom that ...

, Adal and Warsangali in Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constitut ...

, Mughals

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

in the Indian subcontinent (India, Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million pe ...

, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

e.t.c), Safavids in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkme ...

and Ottomans in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The r ...

, were among the influential and distinguished powers in the world. 19th-century colonialism and 20th-century decolonisation have resulted in several independent Muslim-majority states around the world, with vastly differing attitudes towards and political influences granted to, or restricted for, Islam from country to country. These have revolved around the question of Islam's compatibility with other ideological concepts such as secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on secular, naturalistic considerations.

Secularism is most commonly defined as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state, and may be broadened to a si ...

, nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

(especially Arab nationalism and Pan-Arabism, as opposed to Pan-Islamism), socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

(see also Arab socialism and socialism in Iran), democracy (see Islamic democracy), republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

(see also Islamic republic), liberalism and progressivism, feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

, capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

and more.

Mongol invasions

Gunpowder empires

Scholars often use the termAge of the Islamic Gunpowders

The gunpowder empires, or Islamic gunpowder empires, is a collective term coined by Marshall G. S. Hodgson and William H. McNeill at the University of Chicago, referring to three Muslim empires: the Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire and the Mugha ...

to describe period the Safavid, Ottoman and Mughal

Mughal or Moghul may refer to:

Related to the Mughal Empire

* Mughal Empire of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries

* Mughal dynasty

* Mughal emperors

* Mughal people, a social group of Central and South Asia