Eric Melrose Brown on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

afresearch.org

On returning to a United Kingdom then at war, he joined the

On returning to a United Kingdom then at war, he joined the

After World War II‚ Brown commanded the Enemy Aircraft Flight, an elite group of pilots who test-flew captured German and Italian aircraft. That experience rendered Brown one of the few men to have been qualified to compare both Allied and Axis aeroplanes as they flew during the war. He flight-tested 53 German aircraft, including the Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet rocket fighter. That Komet is now on display at the

After World War II‚ Brown commanded the Enemy Aircraft Flight, an elite group of pilots who test-flew captured German and Italian aircraft. That experience rendered Brown one of the few men to have been qualified to compare both Allied and Axis aeroplanes as they flew during the war. He flight-tested 53 German aircraft, including the Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet rocket fighter. That Komet is now on display at the  In 1949, he test flew a modified (strengthened and control-boosted)

In 1949, he test flew a modified (strengthened and control-boosted)

Eric Brown, Interviewed on BBC Radio 4's iPM program

Former BBC space correspondent Reg Turnill interviews Eric Brown in 2008

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20141129012146/http://www.theaviationindex.com/authors/eric-brown List of Articles and publications by Eric Brownvia https://web.archive.org/web/20110110021804/http://www.theaviationindex.com/

The Sea Vampire ''LZ551/G'' at the Fleet Air Arm Museum, Yeovilton

Video

of test pilot Eric "Winkle" Brown landing a Sea Vampire on the experimental

''Captain Eric Brown: Wedded to German Aviation for Better or Worse''

Captain Eric Brown discusses (episode 40 on Astrotalkuk.org) his private meeting with Yuri Gagarin in London on 13 July 1961.

a 1945 ''Flight'' article on Brown's deck-landing trials of the Sea Vampire *

Imperial War Museum Interview from 1991

Imperial War Museum Interview from 1992

Mountbatten lecture goes live

Facts about Eric Brown at key.aero

{{DEFAULTSORT:Brown, Eric 1919 births 2016 deaths Alumni of the University of Edinburgh British World War II pilots Fleet Air Arm aviators People from Leith Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Fellows of the Royal Aeronautical Society Recipients of the Air Force Cross (United Kingdom) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Recipients of the Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air Royal Navy officers of World War II Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve personnel of World War II Scottish autobiographers Scottish non-fiction writers Scottish test pilots British aviation record holders Fleet Air Arm personnel of World War II People from Copthorne, West Sussex

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Eric Melrose "Winkle" Brown, CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

, DSC DSC may refer to:

Academia

* Doctor of Science (D.Sc.)

* District Selection Committee, an entrance exam in India

* Doctor of Surgical Chiropody, superseded in the 1960s by Doctor of Podiatric Medicine

Educational institutions

* Dalton State Col ...

, AFC, Hon FRAeS, RN (21 January 1919 – 21 February 2016) was a British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

officer and test pilot

A test pilot is an aircraft pilot with additional training to fly and evaluate experimental, newly produced and modified aircraft with specific maneuvers, known as flight test techniques.Stinton, Darrol. ''Flying Qualities and Flight Testing ...

who flew 487 types of aircraft, more than anyone else in history.

Brown holds the world record

A world record is usually the best global and most important performance that is ever recorded and officially verified in a specific skill, sport, or other kind of activity. The book ''Guinness World Records'' and other world records organization ...

for the most aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

deck take-offs and landings performed (2,407 and 2,271 respectively) and achieved several "firsts" in naval aviation, including the first landings on an aircraft carrier of a twin-engined aircraft, an aircraft with a tricycle undercarriage

Tricycle gear is a type of aircraft undercarriage, or ''landing gear'', arranged in a tricycle fashion. The tricycle arrangement has a single nose wheel in the front, and two or more main wheels slightly aft of the center of gravity. Tricycle ge ...

, a jet aircraft

A jet aircraft (or simply jet) is an aircraft (nearly always a fixed-wing aircraft) propelled by jet engines.

Whereas the engines in propeller-powered aircraft generally achieve their maximum efficiency at much lower speeds and altitudes, je ...

, and a rotary-wing aircraft.

He flew almost every category of Royal Navy and Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

aircraft: glider, fighter, bomber, airliner, amphibian, flying boat and helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attributes ...

. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he flew many types of captured German, Italian, and Japanese aircraft, including new jet and rocket aircraft. He was a pioneer of jet technology into the postwar era.

Early life

Brown was born inLeith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by '' Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

, near Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

. His father was a former balloon observer and pilot in the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

(RFC) and Brown first flew when he was eight or ten when he was taken up in a Gloster Gauntlet by his father, the younger Brown sitting on his father's knee.

In 1936 Brown's father took him to see the 1936 Olympics 1936 Olympics may refer to:

*The 1936 Winter Olympics, which were held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany

*The 1936 Summer Olympics

The 1936 Summer Olympics (German: ''Olympische Sommerspiele 1936''), officially known as the Games of the XI ...

in Berlin. Hermann Göring had recently announced the existence of the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

, and Brown and his father met and were invited to join social gatherings by members of the newly disclosed organisation. At one of these meetings, Ernst Udet

Ernst Udet (26 April 1896 – 17 November 1941) was a German pilot during World War I and a ''Luftwaffe'' Colonel-General (''Generaloberst'') during World War II.

Udet joined the Imperial German Air Service at the age of 19, and eventually ...

, a former World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

fighter ace, was fascinated to make the acquaintance of Brown senior, a former RFC pilot, and offered to take his son Eric up flying with him. Eric eagerly accepted the German's offer and after his arrival at the appointed airfield at Halle Halle may refer to:

Places Germany

* Halle (Saale), also called Halle an der Saale, a city in Saxony-Anhalt

** Halle (region), a former administrative region in Saxony-Anhalt

** Bezirk Halle, a former administrative division of East Germany

** Hall ...

, he was soon flying in a two-seat Bücker Jungmann. He recalled the incident nearly 80 years later on the BBC radio programme '' Desert Island Discs'',

During the Olympic Games Brown witnessed Hitler shaking hands with Jesse Owens.

In 1937, Brown left the Royal High School and entered the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

, studying modern languages

A modern language is any human language that is currently in use. The term is used in language education to distinguish between languages which are used for day-to-day communication (such as French and German) and dead classical languages such a ...

with an emphasis on German. While there he joined the university's air unit and received his first formal flying instruction. In February 1938 he returned to Germany under the sponsorship of the Foreign Office, having been invited to attend the 1938 Automobile Exhibition by Udet, by then a Luftwaffe major general. He there saw the demonstration of the Focke-Wulf Fw 61 helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attributes ...

flown by Hanna Reitsch before a small crowd inside the '' Deutschlandhalle''. During this visit he met and got to know Reitsch, whom he had also briefly met in 1936.

In the meantime, Brown had been selected to take part as an exchange student at the Schule Schloss Salem, located on the banks of Lake Constance

Lake Constance (german: Bodensee, ) refers to three Body of water, bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, ca ...

, and it was while there in Germany that Brown was woken up with a loud knocking on his door one morning in September 1939. Upon opening the door he was met by a woman with the announcement that " our countries are at war". Soon afterwards, Brown was arrested by the SS. However, after three days' incarceration, they merely escorted Brown in his MG Magnette sports car to the Swiss border, saying they were allowing him to keep the car because they "had no spares for it".Profileafresearch.org

Wartime service

On returning to a United Kingdom then at war, he joined the

On returning to a United Kingdom then at war, he joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

The Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) was established in 1936 to support the preparedness of the U.K. Royal Air Force in the event of another war. The Air Ministry intended it to form a supplement to the Royal Auxiliary Air Force (RAuxAF ...

before subsequently joining the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve as a Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy and is responsible for the delivery of naval air power both from land and at sea. The Fleet Air Arm operates the F-35 Lightning II for maritime strike, the AW159 Wil ...

pilot, where he was posted to 802 Naval Air Squadron

802 Naval Air Squadron (802 NAS) was a Naval Air Squadron of the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm.

Early history

802 Squadron was formed on 3 April 1933 aboard by the merger of two independent Royal Air Force naval units, 408 (Fleet Fighter) Flight ...

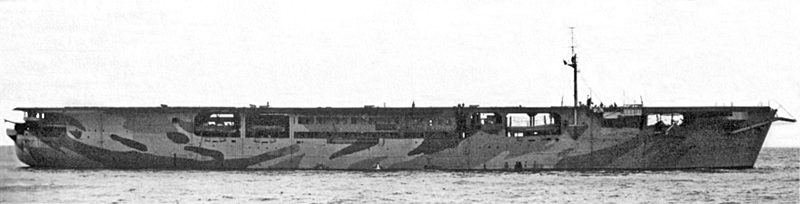

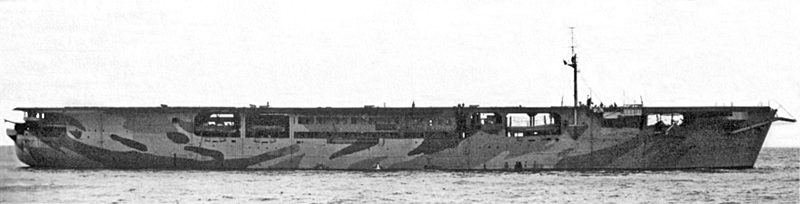

, initially serving on the first escort carrier

The escort carrier or escort aircraft carrier (U.S. hull classification symbol CVE), also called a "jeep carrier" or "baby flattop" in the United States Navy (USN) or "Woolworth Carrier" by the Royal Navy, was a small and slow type of aircraft ...

, , converted and thus named in July 1941. He flew one of the carrier's Grumman Martlets. During his service on board ''Audacity'' he shot down two Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor

The Focke-Wulf Fw 200 ''Condor'', also known as ''Kurier'' to the Allies (English: Courier), was a German all-metal four-engined monoplane originally developed by Focke-Wulf as a long-range airliner. A Japanese request for a long-range maritime p ...

maritime patrol aircraft, using head-on attacks to exploit the blind spot in their defensive armament.

''Audacity'' was torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

ed and sunk on 21 December 1941 by the , commanded by Gerhard Bigalk

Gerhard Bigalk (26 November 1908 – 17 July 1942) was a captain with the ''Kriegsmarine'' during World War II and commander of . He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross of Nazi Germany.

Career

Bigalk spent some years in the ...

. The first rescue ship left because of warnings of a nearby U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

, and Brown was left in the sea overnight with a dwindling band of survivors, until he was rescued the next day. He was the one of two of the 24 to survive the hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe h ...

; the rest succumbed to the cold. Of the complement of 480, 407 survived,

The loss of life was such that 802 Squadron was disbanded until February 1942. On 10 March 1942, Brown was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

*Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom)

*Distinguished Service Cross (U ...

for his service on ''Audacity'', in particular "For bravery and skill in action against Enemy aircraft and in the protection of a Convoy against heavy and sustained Enemy attacks".

Following the loss of ''Audacity'', Brown resumed operational flying, being seconded

In deliberative bodies a second to a proposed motion is an indication that there is at least one person besides the mover that is interested in seeing the motion come before the meeting. It does not necessarily indicate that the seconder favors th ...

to Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; french: Aviation royale canadienne, ARC) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environm ...

(RCAF) squadrons flying escort operations to USAAF Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Relatively fast and high-flying for a bomber of its era, the B-17 was used primarily in the European Theater ...

bombers over France. His job was to train them in deck-landing techniques, though the training took place on airfields.The training was in preparation for the Allied invasion's amphibious operations against Salerno

Salerno (, , ; nap, label= Salernitano, Saliernë, ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' in Campania (southwestern Italy) and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after ...

, Sicily. If the landings had been a failure, the squadrons would have had to be evacuated by carrier. As a form of ''quid pro quo

Quid pro quo ('what for what' in Latin) is a Latin phrase used in English to mean an exchange of goods or services, in which one transfer is contingent upon the other; "a favor for a favor". Phrases with similar meanings include: "give and take", ...

'' he joined them on fighter operations.

this time to perform experimental flying, including batting in the much more experienced Admiralty Test Pilot Lieutant Commander Roy Sydney Baker-Falkner

Roy Sydney Baker-Falkner (3 June 1916 – 18 July 1944) was a Canadian Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm naval aviator and wing leader during the Second World War, who attained the rank of Lieutenant commander. He was a veteran of the evacuation of Dunk ...

flying the experimental Fairey Barracuda

The Fairey Barracuda was a British carrier-borne torpedo and dive bomber designed by Fairey Aviation. It was the first aircraft of this type operated by the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm (FAA) to be fabricated entirely from metal.

The Barracuda ...

onto the deck of a carrier in the Clyde. Almost immediately he was transferred to Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

to evaluate captured ''Regia Aeronautica

The Italian Royal Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica Italiana'') was the name of the air force of the Kingdom of Italy. It was established as a service independent of the Royal Italian Army from 1923 until 1946. In 1946, the monarchy was abolis ...

'' and ''Luftwaffe'' aircraft. This Brown did with almost no tuition, information having to be gleaned from whatever documents were available. On completion of these duties, his commander, being impressed with his performance, sent him back to the RAE with the recommendation that he be employed in the Aerodynamics Flight department at Farnborough. During the first month in the Flight, Brown flew 13 aircraft types, including a captured Focke-Wulf Fw 190

The Focke-Wulf Fw 190, nicknamed ''Würger'' (" Shrike") is a German single-seat, single-engine fighter aircraft designed by Kurt Tank at Focke-Wulf in the late 1930s and widely used during World War II. Along with its well-known counterpart, ...

.

Brown was posted to the Royal Aircraft Establishment

The Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) was a British research establishment, known by several different names during its history, that eventually came under the aegis of the Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom), UK Ministry of Defence (MoD), bef ...

(RAE) at Farnborough Farnborough may refer to:

Australia

* Farnborough, Queensland, a locality in the Shire of Livingstone

United Kingdom

* Farnborough, Hampshire, a town in the Rushmoor district of Hampshire, England

** Farnborough (Main) railway station, a railw ...

, where his experience in deck landings was sought. While there he initially performed testing of the newly navalised Sea Hurricane and Seafire. His aptitude for deck landings led to his posting for the testing of carriers' landing arrangements before they were brought into service. The testing involved multiple combinations of landing point and type of aircraft, with the result being that by the close of 1943 he had performed around 1,500 deck landings on 22 different carriers. In six years at RAE, Brown recalled that he hardly ever took a single day's leave. During carrier compatibility trials, Brown crash-landed a Fairey Firefly Mk I, ''Z1844'', on the deck of on 9 September 1943, when the arrestor hook indicator light falsely showed the hook was in the "down" position, compounded by the batsman failing to notice that the hook was not down. The fighter hit the crash barrier, sheared off its undercarriage and shredded the propeller, but he was unhurt.

While at Farnborough as chief naval test pilot, Brown was involved in the deck landing trials of the de Havilland Sea Mosquito, the heaviest aircraft yet chosen to be flown from a British carrier. Brown landed one for the first time on on 25 March 1944. This was the first landing on a carrier by a twin-engined aircraft.The North American B-25 Mitchell had been flown off a carrier earlier during the attack on Tokyo led by James Doolittle; however the aircraft had been loaded aboard the carrier by crane.The Potez 56 made an arrested landing and a subsequent take-off on French aircraft carrier Béarn in March 1936. The fastest speed for deck landing was , while the aircraft's stall speed was . He also flew several stints with Fighter Command in the air defence of Great Britain. During this time, in the summer of 1944, Brown's home was destroyed by a V-1 "Doodlebug" cruise missile, concussing his wife and causing serious injury to their cleaner. At this time, the RAE was the leading authority on high-speed flight and Brown became involved in this sort of testing, flights being flown where the aircraft, usually a Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

, would be dived at speeds of the high subsonic

Subsonic may refer to:

Motion through a medium

* Any speed lower than the speed of sound within a sound-propagating medium

* Subsonic aircraft, a flying machine that flies at air speeds lower than the speed of sound

* Subsonic ammunition, a type o ...

and near transonic

Transonic (or transsonic) flow is air flowing around an object at a speed that generates regions of both subsonic and supersonic airflow around that object. The exact range of speeds depends on the object's critical Mach number, but transonic ...

region. Figures achieved by Brown and his colleagues during these tests reached Mach

Mach may refer to Mach number, the speed of sound in local conditions. It may also refer to:

Computing

* Mach (kernel), an operating systems kernel technology

* ATI Mach, a 2D GPU chip by ATI

* GNU Mach, the microkernel upon which GNU Hurd is bas ...

0.86 for a standard Spitfire MK IX, to Mach 0.92 for a modified Spitfire PR Mk XI flown by his colleague, Squadron Leader Anthony F. Martindale

Anthony or Antony is a masculine given name, derived from the ''Antonii'', a ''gens'' ( Roman family name) to which Mark Antony (''Marcus Antonius'') belonged. According to Plutarch, the Antonii gens were Heracleidae, being descendants of Anton, ...

.

Assisting the USAAF's Eighth Air Force

Together with Brown and Martindale, the RAE Aerodynamics Flight also included two other test pilots, Sqn Ldr James "Jimmy" Nelson and Sqn Ldr Douglas Weightman. Wings on my Sleeve p. 69 During this same period the RAE was approached by USAAF General Jimmy Doolittle with a request for help, as the 8th Air Force had been having trouble when theirLockheed P-38 Lightning

The Lockheed P-38 Lightning is an American single-seat, twin piston-engined fighter aircraft that was used during World War II. Developed for the United States Army Air Corps by the Lockheed Corporation, the P-38 incorporated a distinctive twi ...

, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt

The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt is a World War II-era fighter aircraft produced by the American company Republic Aviation from 1941 through 1945. It was a successful high-altitude fighter and it also served as the foremost American fighter-bombe ...

and North American P-51 Mustang fighters, providing top cover for the bombers, dived down onto attacking German fighters, some of the diving U.S. fighters encountering speed regions where they became difficult to control.

As a result of Doolittle's request, early in 1944 the P-38H Lightning, a Packard Merlin-powered P-51B Mustang and P-47C Thunderbolt were dived for compressibility testing at the RAE by Brown and several other pilots. The results of the tests were that the tactical Mach numbers, i.e., the manoeuvring limits, were Mach 0.68 for the Lightning and Mach 0.71 for the Thunderbolt; the corresponding figure for both the Fw 190 and Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was, along with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter force. The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War an ...

was Mach 0.75, giving them the advantage in a dive. However the tests flown by Brown and his colleagues also gave a Mach number for the Mustang of 0.78, resulting in Doolittle being able to argue with his superiors for the Mustang to be chosen in preference to the P-38 and P-47 for all escort duties from then on, ''Wings on my Sleeve'', p. 70-72 which was available in growing numbers by very early 1944; for Doolittle's eventual move to air supremacy missions in ''leading'' the bomber combat box

The combat box was a tactical formation used by heavy (strategic) bombers of the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II. The combat box was also referred to as a "staggered formation". Its defensive purpose was in massing the firepower of the bo ...

es with the Mustangs by some 75–100 miles, instead of merely accompanying them nearby.

Brown's first encounters with jet flight

Brown had been made aware of the British progress in jet propulsion in May 1941 when he had heard of the Gloster E.28/39 after diverting in bad weather toRAF Cranwell

Royal Air Force Cranwell or more simply RAF Cranwell is a Royal Air Force station in Lincolnshire, England, close to the village of Cranwell, near Sleaford. Among other functions, it is home to the Royal Air Force College (RAFC), which trai ...

during a flight and had subsequently met Frank Whittle when asked to suggest improvements to the jet engine

A jet engine is a type of reaction engine discharging a fast-moving jet of heated gas (usually air) that generates thrust by jet propulsion. While this broad definition can include rocket, Pump-jet, water jet, and hybrid propulsion, the term ...

to make it more suitable for naval use. This resulted in the Gloster Meteor being selected as the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

's first jet fighter, although, as it turned out, few would be used by them. Brown was also selected as the pilot for the Miles M.52

The Miles M.52 was a turbojet-powered supersonic research aircraft project designed in the United Kingdom in the mid-1940s. In October 1943, Miles Aircraft was issued with a contract to produce the aircraft in accordance with Air Ministry Sp ...

supersonic

Supersonic speed is the speed of an object that exceeds the speed of sound ( Mach 1). For objects traveling in dry air of a temperature of 20 °C (68 °F) at sea level, this speed is approximately . Speeds greater than five times ...

research aircraft programme, and he flew modified aircraft incorporating components intended for the M.52; however, the post-war government cancelled the project in 1945 with the M.52 almost complete. On 2 May 1944, he was appointed MBE Mbe may refer to:

* Mbé, a town in the Republic of the Congo

* Mbe Mountains Community Forest, in Nigeria

* Mbe language, a language of Nigeria

* Mbe' language, language of Cameroon

* ''mbe'', ISO 639 code for the extinct Molala language

Molal ...

"for outstanding enterprise and skill in piloting aircraft during hazardous aircraft trials."

Brown's first encounter with helicopters

In February 1945, Brown learned that the Aerodynamics Flight had been allocated three Sikorsky R-4B Hoverfly/Gadfly helicopters. He had never seen one of these tail-rotor machines, so a trip to Farnborough was arranged and Brown had a short flight as a passenger in one. A few days later, Brown and Martindale were sent toRAF Speke

Speke () is a suburb of Liverpool. It is southeast of the city centre. Located near the widest part of the River Mersey, it is bordered by the suburbs of Garston and Hunts Cross, and nearby to Halewood, Hale Village, and Widnes. The rural ar ...

to collect two new R-4Bs.

On arrival, they found the American mechanics assembling the machines, and when Brown asked the Master Sergeant in charge about himself and Martindale being taught to fly them, he was handed a "large orange-coloured booklet" with the retort; "Whaddya mean, bud? – Here's your instructor". Brown and Martindale examined the booklet and after several practice attempts at hovering and controlling the craft, followed by a stiff drink, they set off for Farnborough. Brown and Martindale managed the trip safely, if raggedly, in formation, although sometimes as much as a couple of miles apart. Wings on my Sleeve p. 91–92

On 4 April, Brown added another "first" to his logbook when engaged in trials in relation to the flexible deck concept with HMS ''Pretoria Castle'', in which he was supposed to make a number of landing approaches to the escort carrier in a Bell Airacobra, which had coincidentally been modified with a tail hook. During one of these passes, Brown declared an emergency and was given permission to make a deck landing; a ruse which had previously been agreed with the carrier's captain, Caspar John. Although the landing was achieved without difficulty, the long take off run required for the Airacobra meant that even with the ship steaming at full speed, there was little margin of error. This was the first carrier landing and take off for any aircraft with a tricycle undercarriage.

The RAE's "Enemy Flight"

With the end of the European war in sight, the RAE prepared itself to acquire German aeronautical technology and aircraft before it was either accidentally destroyed or taken by the Soviets, and, because of his skills in the language, Brown was made the commanding officer of "Operation Enemy Flight". He flew tonorthern Germany

Northern Germany (german: link=no, Norddeutschland) is a linguistic, geographic, socio-cultural and historic region in the northern part of Germany which includes the coastal states of Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Lower Saxony an ...

; among the targets for the RAE was the Arado Ar 234, a new jet bomber in which the Allies, particularly the Americans, were very much interested. A number of the jets were based at an airfield in Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

, the German forces having retreated there. He expected to arrive at a liberated aerodrome, just after it had been taken by the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

; however, German resistance to the Allied advance meant that the ground forces had been delayed and the airfield was still an operational Luftwaffe base. Luckily for Brown, the commanding officer of the Luftwaffe airfield at Grove offered his surrender and Brown took charge of the airfield and its staff of 2,000 men until Allied forces arrived the next day.

Subsequently, Brown and Martindale, along with several other members of the Aerodynamics Flight and assisted by a co-operative German pilot, later ferried twelve Ar 234s across the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

and on to Farnborough. The venture was not without risk, as before their capture, the Germans had destroyed all the engine log books for the aircraft, leaving Brown and his colleagues no idea of the expected engine hours remaining to the machines. Because of the scarcity of the special high-temperature alloys for use in their construction, the Junkers Jumo 004

The Junkers Jumo 004 was the world's first production turbojet engine in operational use, and the first successful axial compressor turbojet engine. Some 8,000 units were manufactured by Junkers in Germany late in World War II, powering the Mess ...

engines had a life of only 25 hours – it was thus not known whether the engines were brand new or just about to expire. ''Wings on my Sleeve'', p. 116

During this period, Brown was asked by Brigadier Glyn Hughes, the Medical Officer of the British 2nd Army occupying the newly liberated Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, to help interrogate the former camp commandant and his assistant. Wings on my Sleeve p. 94 Agreeing to do so, he soon interviewed Josef Kramer

Josef Kramer (10 November 1906 – 13 December 1945) was Hauptsturmführer and the Commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau (from 8 May 1944 to 25 November 1944) and of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp (from December 1944 to its liberation on 15 Apr ...

and Irma Grese

Irma Ilse Ida Grese (7 October 1923 – 13 December 1945) was a Nazi concentration camp guard at Ravensbrück and Auschwitz, and served as warden of the women's section of Bergen-Belsen. She was a volunteer member of the SS.

Grese was convi ...

, and remarked upon the experience by saying that; "Two more loathsome creatures it is hard to imagine" and further describing the latter as "... the worst human being I have ever met." Kramer and Grese were later tried and hanged for war crimes. Wings on my Sleeve, p. 98

Postwar

After World War II‚ Brown commanded the Enemy Aircraft Flight, an elite group of pilots who test-flew captured German and Italian aircraft. That experience rendered Brown one of the few men to have been qualified to compare both Allied and Axis aeroplanes as they flew during the war. He flight-tested 53 German aircraft, including the Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet rocket fighter. That Komet is now on display at the

After World War II‚ Brown commanded the Enemy Aircraft Flight, an elite group of pilots who test-flew captured German and Italian aircraft. That experience rendered Brown one of the few men to have been qualified to compare both Allied and Axis aeroplanes as they flew during the war. He flight-tested 53 German aircraft, including the Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet rocket fighter. That Komet is now on display at the National Museum of Flight

The National Museum of Flight is Scotland's national aviation museum, at East Fortune Airfield, just south of the village of East Fortune, Scotland. It is one of the museums within National Museums Scotland. The museum is housed in the original ...

east of Edinburgh in the United Kingdom.

His flight test of this rocket plane, the only one by an Allied pilot using the rocket motor, was accomplished unofficially: it was deemed to be more or less suicidal due to the notoriously dangerous C-Stoff

C-Stoff (; "substance C") was a reductant used in bipropellant rocket fuels (as a fuel itself) developed by Hellmuth Walter Kommanditgesellschaft in Germany during World War II. It was developed for use with T-Stoff (a high-test peroxide) as an oxi ...

fuel and T-Stoff

T-Stoff (; 'substance T') was a stabilised high test peroxide used in Germany during World War II. T-Stoff was specified to contain 80% (occasionally 85%) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), remainder water, with traces (<0.1%) of stabilisers. Stabilisers ...

oxidizer combination.

Commenting to a newspaper in September 2015 he recalled, To me it was the most exciting thing on the horizon, a totally new experience. I remember watching the ground crew very carefully before take-off, wondering if they thought they were waving goodbye to me forever or whether they thought this thing was going to return. The noise it made was absolutely thunderous and it was like being in charge of a runaway train; everything changed so rapidly and I really had to have my wits about me.Brown flight-tested all three of the German jet designs to see front-line action in the war: the

Messerschmitt Me 262

The Messerschmitt Me 262, nicknamed ''Schwalbe'' (German: "Swallow") in fighter versions, or ''Sturmvogel'' (German: "Storm Bird") in fighter-bomber versions, is a fighter aircraft and fighter-bomber that was designed and produced by the Germa ...

A ''Schwalbe'' and the Arado Ar 234B ''Blitz'', each type powered by twin Junkers Jumo 004 engines, and the single-engined BMW 003-powered Heinkel He 162A ''Spatz'' turbojet combat aircraft. He would later fly the He 162A at the Farnborough Air Show

The Farnborough Airshow, officially the Farnborough International Airshow, is a trade exhibition for the aerospace and defence industries, where civilian and military aircraft are demonstrated to potential customers and investors. Since its fir ...

, and described it as having the best controls of any aircraft he had ever flown but as being difficult to handle. One of his colleagues at Farnborough died trying the aircraft type in an evaluation.

Fluent in German, he helped interview many Germans after World War II, including Wernher von Braun and Hermann Göring, Wings on my Sleeve, p. 110 Willy Messerschmitt

Wilhelm Emil "Willy" Messerschmitt (; 26 June 1898 – 15 September 1978) was a German aircraft designer and manufacturer. In 1934, in collaboration with Walter Rethel, he designed the Messerschmitt Bf 109, which became the most importan ...

, Ernst Heinkel and Kurt Tank

Kurt Waldemar Tank (24 February 1898 – 5 June 1983) was a German aeronautical engineer and test pilot who led the design department at Focke-Wulf from 1931 to 1945. He was responsible for the creation of several important Luftwaffe aircraft of ...

. However, he described the interviews as being minimal, due to the need to begin the Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

trials, and limited to matters related to aviation.

Brown was using Himmler's personal aircraft, a specially converted Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor

The Focke-Wulf Fw 200 ''Condor'', also known as ''Kurier'' to the Allies (English: Courier), was a German all-metal four-engined monoplane originally developed by Focke-Wulf as a long-range airliner. A Japanese request for a long-range maritime p ...

that had been captured and was being used by the RAE Flight based at the former Luftwaffe airfield at Schleswig. Wings on my Sleeve p. 114 He was also able to renew acquaintances with German pilot Hanna Reitsch, whom he had met in Germany before the war. She had been arrested after the German surrender in 1945. Fearing the approaching Russians, her father had killed her mother, sister and then himself.

As an RAE test pilot

A test pilot is an aircraft pilot with additional training to fly and evaluate experimental, newly produced and modified aircraft with specific maneuvers, known as flight test techniques.Stinton, Darrol. ''Flying Qualities and Flight Testing ...

he was involved in the wartime Miles M.52

The Miles M.52 was a turbojet-powered supersonic research aircraft project designed in the United Kingdom in the mid-1940s. In October 1943, Miles Aircraft was issued with a contract to produce the aircraft in accordance with Air Ministry Sp ...

supersonic

Supersonic speed is the speed of an object that exceeds the speed of sound ( Mach 1). For objects traveling in dry air of a temperature of 20 °C (68 °F) at sea level, this speed is approximately . Speeds greater than five times ...

project, test flying a Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Griff ...

fitted with the M.52's all moving tail, diving from high altitude to achieve high subsonic

Subsonic may refer to:

Motion through a medium

* Any speed lower than the speed of sound within a sound-propagating medium

* Subsonic aircraft, a flying machine that flies at air speeds lower than the speed of sound

* Subsonic ammunition, a type o ...

speeds. He was due to fly the M.52 in 1946, but this fell through when the project was cancelled. The all moving tail information, however, supplied upon instruction from the British government ostensibly as part of an information exchange with the Americans (although no information was ever received in return), allowed Bell to modify its XS-1 for true transsonic pitch controllability, in turn allowing Chuck Yeager to become the first man to exceed Mach 1 in 1947.

If the Ministry of Supply had proceeded with Ralph Smith's V2-based Megaroc sub-orbital manned spacecraft, Brown would also have been the leading candidate for its projected 1949 first manned spaceflight.

In a throwback to his days testing aircraft in high speed dives, while at the RAE Brown performed similar testing of the Avro Tudor

The Avro Type 688 Tudor was a British piston-engined airliner based on Avro's four-engine Lincoln bomber, itself a descendant of the famous Lancaster heavy bomber, and was Britain's first pressurised airliner. Customers saw the aircraft as ...

airliner. The requirement was to determine the safe limiting speed for the aircraft and to gather data on high-speed handling of large civil aircraft in preparation for a projected four-jet version of the Tudor. Flying from 32,000 ft, in a succession of dives to speeds initially to Mach 0.6, he succeeded in diving the Tudor up to Mach 0.7, an unusual figure for such a large piston-engined aeroplane, this speed figure being dictated by the pilot's discretion, as pulling the aircraft out of the dive had required the combined efforts of both Brown and his second pilot. However, as an airliner, the Tudor was not a success. The planned jet version of the Tudor would later become the Avro Ashton

The Avro 706 Ashton was a British prototype jet airliner made by Avro during the 1950s. Although it flew nearly a year after the de Havilland Comet, it represented an experimental programme and was never intended for commercial use.

Design an ...

. Wings on my Sleeve p. 174

In 1949, he test flew a modified (strengthened and control-boosted)

In 1949, he test flew a modified (strengthened and control-boosted) de Havilland DH.108

The de Havilland DH 108 "Swallow" was a British experimental aircraft designed by John Carver Meadows Frost in October 1945. The DH 108 featured a tailless, swept wing with a single vertical stabilizer, similar to the layout of the wartime Ge ...

, after a crash in a similar aircraft while diving at speeds approaching the sound barrier had killed Geoffrey de Havilland, Jr., Brown initially started his tests from a height of 35,000 ft, rising to 45,000 ft and during a dive from the latter he achieved a Mach number

Mach number (M or Ma) (; ) is a dimensionless quantity in fluid dynamics representing the ratio of flow velocity past a boundary to the local speed of sound.

It is named after the Moravian physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach.

: \mathrm = \frac ...

of 0.985. It was only when attempting the tests from the same height as de Havilland, 4,000 ft, that he discovered that in a Mach 0.88 dive from that altitude the aircraft suffered from a high- g pitch oscillation

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum ...

at several hertz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), equivalent to one event (or cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose expression in terms of SI base units is s−1, meaning that on ...

(Hz). "The ride was smooth, then suddenly it all went to pieces ... as the plane porpoised wildly my chin hit my chest, jerked hard back, slammed forward again, repeated it over and over, flogged by the awful whipping of the plane ...". Remembering the drill he had often practised, Brown managed to pull back gently on both stick and throttle and the motion; "... ceased as quickly as it had started". Wings on my Sleeve p. 184 He believed that he survived the test flight partly because he was a shorter man, de Havilland having suffered a broken neck possibly due to the violent oscillation. Wings on my Sleeve, p. 184

Test instrumentation on Brown's flight recorded during the oscillations accelerations of +4 and −3g's at 3 Hz. Brown described the DH 108 as; "A killer. Nasty stall. Vicious undamped longitudinal oscillation at speed in bumps". ''Wings on my Sleeve'', p. 147 All three DH 108 aircraft were lost in fatal accidents.

In 1948, Brown was awarded the Boyd Trophy

The Boyd Trophy is a silver model of a Fairey Swordfish, which was presented by the Fairey Aviation Company, Fairey Aviation Company Limited in 1946, in commemoration of the work for Naval Aviation of Admiral Sir Denis Boyd, Order of the Bath, KCB ...

for his work in trials for the rubber deck

The flight deck of an aircraft carrier is the surface from which its aircraft take off and land, essentially a miniature airfield at sea. On smaller naval ships which do not have aviation as a primary mission, the landing area for helicopter ...

landing system. On 30 March 1949 he was granted a permanent Royal Navy commission as a lieutenant, with seniority backdated to his original wartime promotion to the rank.

On 12 August 1949, he was testing the third of three Saunders-Roe SR.A/1 jet-powered flying-boat fighter prototypes, ''TG271'', when he struck submerged debris, which resulted in the aircraft sinking in the Solent off Cowes

Cowes () is an English seaport town and civil parish on the Isle of Wight. Cowes is located on the west bank of the estuary of the River Medina, facing the smaller town of East Cowes on the east bank. The two towns are linked by the Cowes Floa ...

, Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

.Hooks, Mike, "''The Jet Boat''", Aeroplane, London, UK, Number 411, Volume 35, Number 7, p. 90. He was pulled unconscious from the cockpit of the wrecked aircraft by his Saunders-Roe test pilot Geoffrey Tyson

Geoffrey Arthur Virley Tyson FRAeS OBE (4 February 1907 – 9 January 1987) was an RAF officer, barnstormer and test pilot. He is best known for his aerobatic skills and the test flying of the Saunders-Roe SR.A/1 and Princess flying boats.

Ea ...

, having been knocked out in the crash. He was promoted lieutenant-commander on 1 April 1951, commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

on 31 December 1953 and captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on 31 December 1960.

Brown was responsible for at least three important firsts in carrier

Carrier may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Carrier'' (album), a 2013 album by The Dodos

* ''Carrier'' (board game), a South Pacific World War II board game

* ''Carrier'' (TV series), a ten-part documentary miniseries that aired on PBS in April 20 ...

aviation: the first carrier landing using an aircraft equipped with a tricycle undercarriage

Tricycle gear is a type of aircraft undercarriage, or ''landing gear'', arranged in a tricycle fashion. The tricycle arrangement has a single nose wheel in the front, and two or more main wheels slightly aft of the center of gravity. Tricycle ge ...

( Bell Airacobra Mk 1 ''AH574

''AH574'' was a Bell Airacobra I used by the Royal Navy for test work during and after the Second World War

Initial history

''AH574'' was initially ordered in 1940 for the Royal Air Force (RAF) as part of the Airacobra I serial number block ...

'') on the trials carrier on 4 April 1945; the first landing of a twin-engined aircraft on a carrier (the Mosquito) on on 25 March 1944; and the world's first carrier landing of a jet aircraft

A jet aircraft (or simply jet) is an aircraft (nearly always a fixed-wing aircraft) propelled by jet engines.

Whereas the engines in propeller-powered aircraft generally achieve their maximum efficiency at much lower speeds and altitudes, je ...

, landing the prototype de Havilland Vampire '' LZ551/G'' on the Royal Navy carrier on 3 December 1945. For this work with the Mosquito and the Vampire

A vampire is a mythical creature that subsists by feeding on the Vitalism, vital essence (generally in the form of blood) of the living. In European folklore, vampires are undead, undead creatures that often visited loved ones and caused mi ...

he was later appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE).

In the 1950s during the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, Brown was seconded as an exchange officer for two years to Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland, US where he flew a number of American aircraft, including 36 types of helicopter. In January 1952, it was while at Patuxent River that Brown demonstrated the steam catapult to the Americans, flying a Grumman Panther off the carrier while the ship was still tied up to the dock at the Philadelphia Naval Yard. It had been planned for Brown to make the first catapult launch with the ship under way and steaming into any wind; however, the wind on the day was so slight that British officials decided that, as the new steam catapult was capable of launching an aircraft without any wind, they would risk their pilot (Brown) if the Americans would risk their aircraft. The launch was a success and US carriers would later feature the steam catapult.

It was around the same time that another British invention was being offered to the US, the angled flight deck

The flight deck of an aircraft carrier is the surface from which its aircraft take off and land, essentially a miniature airfield at sea. On smaller naval ships which do not have aviation as a primary mission, the landing area for helicopter ...

, and Brown once again was called upon to promote the concept. Whether due to Brown or not, the first US aircraft carrier modified with the new flight deck, , was ready less than nine months later.

In 1954 Brown, by then a Commander in the Royal Navy, became Commander (Air) of the RNAS Brawdy

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps ...

, where he remained until returning to Germany in late 1957, becoming Chief of British Naval Mission to Germany, his brief being to re-establish German naval aviation after its pre-war integration with and subornation to, the Luftwaffe. During this period Brown worked closely with Admiral Gerhard Wagner of the German Naval Staff. Training was conducted initially in the UK on Hawker Sea Hawks and Fairey Gannets, and during this time Brown was allocated a personal Percival Pembroke

The Percival Pembroke is a British high-wing twin-engined light transport aircraft built by the Percival Aircraft Company, later Hunting Percival.

Development

The Pembroke was a development of the Percival Prince civil transport. It had a ...

aircraft by the Marineflieger, which, to his surprise, the German maintenance personnel took great pride in. It was, in fact, the first exclusively naval aircraft the German Navy had owned since the 1930s. Wings on my Sleeve p. 230 Brown led the re-emergence of naval aviation in Germany to the point that in 1960 Marineflieger squadrons were integrated into NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

.

Later Brown enjoyed a brief three-month period as a test pilot for the Focke-Wulf

Focke-Wulf Flugzeugbau AG () was a German manufacturer of civil and military aircraft before and during World War II. Many of the company's successful fighter aircraft designs were slight modifications of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190. It is one of the ...

company, helping them out until they could find a replacement after the company's previous test pilot had been detained due to having relatives in East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

. Wings on my Sleeve p. 233

In the 1960s, due to his considerable experience of carrier aviation, Brown, while working at the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

* Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

*Admiralty, Tr ...

as deputy director of Naval Air Warfare, was consulted on the flight deck arrangement of the planned new UK class of aircraft carrier, the CVA-01

CVA-01 was a proposed United Kingdom aircraft carrier, designed during the 1960s. The ship was intended to be the first of a class that would replace all of the Royal Navy's carriers, most of which had been designed before or during the Second ...

, although the ship was subsequently cancelled while still on the stocks.

In September 1967 came his last appointment in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

when, as a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

, he took command of HMS ''Fulmar'', then the Royal Naval Air Station (now RAF), Lossiemouth, until March 1970. He was appointed a naval aide de camp to Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. She was queen ...

on 7 July 1969 and appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(CBE) in the 1970 New Year Honours. He relinquished his appointment as naval ADC on 27 January 1970 and retired from the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

later in 1970.

Records

Brown flew aircraft from Britain, the United States, Germany, the Soviet Union, Italy and Japan and is listed in the ''Guinness Book of World Records

''Guinness World Records'', known from its inception in 1955 until 1999 as ''The Guinness Book of Records'' and in previous United States editions as ''The Guinness Book of World Records'', is a reference book published annually, listing world ...

'' as holding the record for flying the greatest number of different aircraft. The official record is 487, but includes only basic types. For example, Brown flew 14 versions of the Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Griff ...

and Seafire and although these versions are very different they appear only once in the list. This list includes only aircraft flown by Brown as "Captain in Command".

Because of the special circumstances involved, Brown didn't think that this record would ever be topped.

He also held the world record for the most carrier landings, 2,407, partly compiled in testing the arrestor wires on more than 20 aircraft carriers during World War II.

Credits

In his book ''Wings on My Sleeve'' (page 157 et seq), Brown records his admiration of a number of erstwhile colleagues who deserve recognition:- Brown goes on to mention the pilot of the first jet flight in Britain,Gerry Sayer

Flying Officer Phillip Edward Gerald Sayer (5 February 1905 – 21 October 1942), was the chief test pilot for Gloster Aircraft as well as a serving RAF officer. "Gerry" Sayer flew Britain's maiden jet flight in Sir Frank Whittle's Gloster E. ...

, then the aircraft designers R. J. Mitchell (designer of the Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Griff ...

), Sir Sydney Camm

Sir Sydney Camm, CBE, FRAeS (5 August 189312 March 1966) was an English aeronautical engineer who contributed to many Hawker aircraft designs, from the biplanes of the 1920s to jet fighters. One particularly notable aircraft he designed was th ...

, R. E. Bishop

Ronald Eric Bishop CBE FRAeS (27 February 1903 – 11 June 1989), commonly referred to as R. E. Bishop, was a British engineer who was the chief designer of the de Havilland Mosquito, one of the most famous aircraft of the Second World War ...

, Roy Chadwick

Roy Chadwick, CBE, FRSA, FRAeS (30 April 1893 – 23 August 1947) was an aircraft design engineer for the Avro Company.

Born at Marsh Hall Farm, Farnworth, Widnes, the son of the mechanical engineer Charles Chadwick, he was the chief designer f ...

and Joe Smith, followed by the names of what he describes as " boffins and boffinettes", which include the brilliant aerodynamicists Morien Morgan

Sir Morien Bedford Morgan Order of the Bath, CB Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (20 December 1912 – 4 April 1978), was a noted Welsh aeronautical engineer, sometimes known as "the Father of Concorde". He spent most of his career at the Royal ...

, Handel Davies, Dai Morris and P. A. Hufton, and the "boffinettes" like aerodynamicist Gwen Alston

Hannah Gwendolen Shone (22 May 1907 – 14 July 1993) was a British aerodynamicist and educationalist most known for her work on spinning tunnels and aircraft flight-testing during World War II, as well as her involvement in flight educati ...

, Anne Burns (structural engineer), Dorothy Pearse (aircraft engineer) and Pauline Gower

Pauline Mary de Peauly Gower Fahie (22 July 1910 – 2 March 1947) was a British pilot and writer who established the women's branch of the Air Transport Auxiliary during the Second World War.

Early life and education

Pauline Mary de Peauly ...

(head of the women's section of the ATA).

Brown's last credits mention Lewis Boddington

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* "Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohead ...

, Dr. Thomlinson, John Noble and Charles Crowfoot

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was "f ...

, whom he records (with "others") as being responsible for "giving the Royal Navy a technical lead in aircraft carrier equipment which it still holds to this day 978

Year 978 ( CMLXXVIII) was a common year starting on Tuesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* Battle of Pankaleia: Rebel forces under General Bardas Skleros are defeated ...

" He ends this section: "These men and women were civil servants, but they worked hours, took responsibility, and produced results far beyond what their country paid them for. To me they represent the true measure of Britain's greatness."

Books

Brown wrote several books about his experiences, including ones describing the flight characteristics of the various aircraft he flew and an autobiography, ''Wings on My Sleeve'', first published in 1961 and considerably up-dated in later editions. Other books were 'Wings of the Luftwaffe', 'Wings of the Weird and Wonderful' and 'Miles M.52' (with Dennis Bancorft). He was also the author of dozens of articles in aviation magazines and journals. His best-known series of articles is "Viewed from the Cockpit", which was published (and occasionally re-published) in the journal ''Air International

''AIR International'' is a British aviation magazine covering current defence aerospace and civil aviation topics. It has been in publication since 1971 and is currently published by Key Publishing Ltd.

History and profile

The magazine was fir ...

''. Flight review highlights in this series have included the following types:

* Dornier Do 217

* Fairey Swordfish

* Fairey Fulmar

* Fairey Spearfish, a prototype torpedo bomber (1947) which Brown did not enjoy

* Fairey Barracuda

The Fairey Barracuda was a British carrier-borne torpedo and dive bomber designed by Fairey Aviation. It was the first aircraft of this type operated by the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm (FAA) to be fabricated entirely from metal.

The Barracuda ...

, which Brown found lacklustre and somewhat disappointing

* Focke-Wulf Fw 190

The Focke-Wulf Fw 190, nicknamed ''Würger'' (" Shrike") is a German single-seat, single-engine fighter aircraft designed by Kurt Tank at Focke-Wulf in the late 1930s and widely used during World War II. Along with its well-known counterpart, ...

A and D Series. Wings of the Luftwaffe, pp. 78–91

* Grumman F9F Panther and Grumman F-9 Cougar, which Brown found (on initial models) somewhat underpowered

* Hawker Sea Fury

* Hawker Sea Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane was a British single-seat fighter aircraft designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. Some versions were built in Canada by the Canada Car and Foundry Co Ltd

British variants

Hurricane Mk I

; Hurricane Mk I ( ...

* Heinkel He 111

The Heinkel He 111 is a German airliner and bomber designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1934. Through development, it was described as a "wolf in sheep's clothing". Due to restrictions placed on Germany after th ...

* Junkers Ju 87

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from ''Sturzkampfflugzeug'', "dive bomber") was a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Con ...

D ''Stuka''

* Supermarine Seafire

The Supermarine Seafire is a naval version of the Supermarine Spitfire adapted for operation from aircraft carriers. It was analogous in concept to the Hawker Sea Hurricane, a navalised version of the Spitfire's stablemate, the Hawker Hurri ...

, various marks.

* Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was, along with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter force. The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War an ...

E (Emil) and G (Gustav) – Brown flew the G-12 training sub-type from the rear cockpit and nearly crashed because of poor visibility from that position.

* Messerschmitt Me 163

The Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet is a rocket-powered interceptor aircraft primarily designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Messerschmitt. It is the only operational rocket-powered fighter aircraft in history as well as th ...

''Komet''. Brown was one of few pilots to successfully fly one of these, having signed a disclaimer for the German ground crew.''Wings of the Luftwaffe'', pp. 167–176

* Messerschmitt Me 262

The Messerschmitt Me 262, nicknamed ''Schwalbe'' (German: "Swallow") in fighter versions, or ''Sturmvogel'' (German: "Storm Bird") in fighter-bomber versions, is a fighter aircraft and fighter-bomber that was designed and produced by the Germa ...

''Schwalbe''. Wings of the Luftwaffe, pp. 58–68

* Heinkel He 177 ''Greif'' bomber Wings of the Luftwaffe, pp. 46–57

As regards his preferences Brown states:

My favourite in the piston engine (era) is the de Havilland Hornet. For the simple reason it was over-powered. This is an unusual feature in an aircraft, you could do anything on one engine, almost, that you could do on two. It was a 'hot rod Hot rods are typically American cars that might be old, classic, or modern and that have been rebuilt or modified with large engines optimised for speed and acceleration. One definition is: "a car that's been stripped down, souped up and made ...Mosquito' really, I always described it as like flying aFerrari Ferrari S.p.A. (; ) is an Italian luxury sports car manufacturer based in Maranello, Italy. Founded by Enzo Ferrari (1898–1988) in 1939 from the Alfa Romeo racing division as ''Auto Avio Costruzioni'', the company built its first car in ...in the sky. On the jet side I was a great admirer of the F-86 Sabre, but in particular, the Model E (F-86E) which had the flying tail, and this gave me what I call the 'perfect harmony of control'. If a pilot has this perfect harmony of control you feel you're part of the aeroplane and you're bonded with it really. You've got into it and the aeroplane welcomes you and says 'thank God you've come, you're part of me anyway' and to fly like that is a sheer delight.

Later life

Brown served as president of the Royal Aeronautical Society from 1982 to 1983. His last flight as a pilot was in 1994, but in 2015 he was still lecturing and regularly attending the British Rocketry Oral History Programme (BROHP), where the annual presentation of theSir Arthur Clarke Award

The Sir Arthur Clarke Award is a British award given annually since 2005 in recognition of notable contributions to space exploration, particularly British achievements. Nominations for the awards are made by members of the public, with shortlis ...

s takes place. In 2007 he was the recipient of their Lifetime Achievement Award.

Brown lived, in semi-retirement, at Copthorne, West Sussex. He had married Evelyn (Lynn) Macrory in 1942. She died in 1998. He was interviewed many times, most recently by BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history from the BBC' ...

at his home in April 2013.

In June 2014 he was the subject of the hour-long BBC Two

BBC Two is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network owned and operated by the BBC. It covers a wide range of subject matter, with a remit "to broadcast programmes of depth and substance" in contrast to the more mainstream an ...

documentary ''Britain's Greatest Pilot: The Extraordinary Story of Captain Winkle Brown''. Assessing those achievements, Mark Bowman, chief test pilot at BAE Systems

BAE Systems plc (BAE) is a British multinational arms, security, and aerospace company based in London, England. It is the largest defence contractor in Europe, and ranked the seventh-largest in the world based on applicable 2021 revenues. ...

, said, "They didn't have the advantage of high-tech simulators. He just had to look at the aircraft and think what he was going to do with it", adding that he would have been flying the aircraft with "the benefit of a slide rule, not a bank of computers as we have now."

In November 2014 he was the guest for the 3,000th edition of BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history from the BBC' ...

's '' Desert Island Discs''. During the programme, the 95-year-old said that he still enjoyed driving and had just bought himself a new sports car. His musical choices included " At Last" by the Glenn Miller Orchestra

Glenn Miller and His Orchestra was an American swing dance band formed by Glenn Miller in 1938. Arranged around a clarinet and tenor saxophone playing melody, and three other saxophones playing harmony, the band became the most popular and com ...

and " Amazing Grace" by the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards. His favourite was " Stardust" by Artie Shaw and His Orchestra.

On 24 February 2015 Brown delivered the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

Mountbatten Lecture, entitled "Britain's Defence in the Near Future". Speaking at the Playfair Library, he warned: "They he Russians

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

are playing a very dangerous game of chess. ... They are playing it to the hilt. It may develop into that. It is certainly showing the same signs as what caused the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

."

In May 2015, Brown was awarded the Founder's Medal by the Air League

The Air League is an aviation and aerospace non-profit organisation based in the United Kingdom. It is the UK's largest provider of aviation and aerospace scholarships and bursaries.

The Air League aims to inspire, enable, and support the next ...

. This was presented to him by the patron, the Duke of Edinburgh

Duke of Edinburgh, named after the city of Edinburgh in Scotland, was a substantive title that has been created three times since 1726 for members of the British royal family. It does not include any territorial landholdings and does not produc ...

at the annual reception held at St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, the capital of the United Kingdom. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster in London. Altho ...

"for his amazing flying achievements and involvement with aviation during a remarkable lifetime." Brown died aged 97 on 21 February 2016 at East Surrey Hospital

East Surrey Hospital is a National Health Service hospital in the Whitebushes area to the south of Redhill, in Surrey, England. It is managed by the Surrey and Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust.

History

The hospital has its origins in the Reigate C ...

in Redhill, Surrey

Redhill () is a town in the borough of Reigate and Banstead within the county of Surrey, England. The town, which adjoins the town of Reigate to the west, is due south of Croydon in Greater London, and is part of the London commuter belt. The ...

after a short illness.

Nickname

Brown received the affectionate nickname "Winkle" from his Royal Navy colleagues. Short for "Periwinkle", a smallmollusc

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is esti ...

, the name was given to Brown because of his short stature of . Brown partly attributed his survival of dangerous incidents to his ability to "curl himself up in the cockpit".

Honours and awards

* 10 March 1942 Temporary Sub-Lieutenant (A) Eric Melrose Brown RNVR of HMS ''Audacity'' is awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) in particular "For bravery and skill in action against Enemy aircraft and in the protection of a Convoy against heavy and sustained Enemy attacks". * 2 May 1944 Temporary Lieutenant (A) Eric Melrose Brown, DSC, RNVR is appointedMember of the Order of the British Empire (MBE)

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

''"for outstanding enterprise and skill in piloting aircraft during hazardous flight trials."''

* 19 February 1946 Temporary Acting Lieutenant Commander (A) Eric Melrose Brown, MBE, DSC, RNVR is appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) ''"For courage, exceptional skill and devotion to duty in carrying out the first deck-landings of Mosquito and Vampire. In doing so he has been the first pilot ever to land on the deck of a carrier, a twin-engined aircraft ( Mosquito) and a pure jet-propelled aircraft (Vampire

A vampire is a mythical creature that subsists by feeding on the Vitalism, vital essence (generally in the form of blood) of the living. In European folklore, vampires are undead, undead creatures that often visited loved ones and caused mi ...

). The success of these great strides in Naval Aviation has been largely due to his exceptional flying skill".''

* 6 June 1947 Lieutenant Commander Eric Brown OBE DSC is awarded the Air Force Cross (AFC)

* 1 January 1949 Lieutenant Commander E. M. Brown, OBE, DSC, AFC is awarded at the King's Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air

The Queen's Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air, formerly the King's Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air, was a merit award for flying service awarded by the United Kingdom between 1942 and 1994. It was replaced by the Queen’ ...

* 1 January 1970 Captain Eric Melrose Brown, OBE, DSC, AFC, Royal Navy is appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE).

* 3 July 2018 – statue of Eric Brown unveiled at Edinburgh Airport.Edinburgh Evening News 3 July 2018

See also

*No. 1426 Flight RAF