Ecuador ( ; ;

Quechua

Quechua may refer to:

*Quechua people, several indigenous ethnic groups in South America, especially in Peru

*Quechuan languages, a Native South American language family spoken primarily in the Andes, derived from a common ancestral language

**So ...

: ''Ikwayur'';

Shuar

The Shuar are an Indigenous people of Ecuador and Peru. They are members of the Jivaroan peoples, who are Amazonian tribes living at the headwaters of the Marañón River.

Name

Shuar, in the Shuar language, means "people". The people who speak ...

: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the

Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

";

Quechua

Quechua may refer to:

*Quechua people, several indigenous ethnic groups in South America, especially in Peru

*Quechuan languages, a Native South American language family spoken primarily in the Andes, derived from a common ancestral language

**So ...

: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika'';

Shuar

The Shuar are an Indigenous people of Ecuador and Peru. They are members of the Jivaroan peoples, who are Amazonian tribes living at the headwaters of the Marañón River.

Name

Shuar, in the Shuar language, means "people". The people who speak ...

: ''Ekuatur Nunka''), is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by

Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

on the north,

Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

on the east and south, and the

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

on the west. Ecuador also includes the

Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands (Spanish: , , ) are an archipelago of volcanic islands. They are distributed on each side of the equator in the Pacific Ocean, surrounding the centre of the Western Hemisphere, and are part of the Republic of Ecuador ...

in the Pacific, about west of the mainland. The country's

capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used f ...

and largest city is

Quito

Quito (; qu, Kitu), formally San Francisco de Quito, is the capital and largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its urban area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha. Quito is located in a valley o ...

.

The territories of modern-day Ecuador were once home to a variety of

Indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

groups that were gradually incorporated into the

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The admin ...

during the 15th century. The territory was

colonized by Spain during the 16th century, achieving independence in 1820 as part of

Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia (, "Great Colombia"), or Greater Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia (Spanish: ''República de Colombia''), was a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 18 ...

, from which it emerged as its own sovereign state in 1830. The legacy of both empires is reflected in Ecuador's ethnically diverse population, with most of its million people being

mestizo

(; ; fem. ) is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed Ethnic groups in Europe, European and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also r ...

s, followed by large minorities of

Europeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common genetic ancestry, common language, or both. Pan and Pfeil (2004) ...

,

Native American, and

African

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

descendants. Spanish is the official language and is spoken by a majority of the population, though 13 Native languages are also recognized, including

Quechua

Quechua may refer to:

*Quechua people, several indigenous ethnic groups in South America, especially in Peru

*Quechuan languages, a Native South American language family spoken primarily in the Andes, derived from a common ancestral language

**So ...

and

Shuar

The Shuar are an Indigenous people of Ecuador and Peru. They are members of the Jivaroan peoples, who are Amazonian tribes living at the headwaters of the Marañón River.

Name

Shuar, in the Shuar language, means "people". The people who speak ...

.

The

sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a polity, political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defin ...

of Ecuador is a

representative democratic

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a type of democracy where elected people represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function as some type of represe ...

republic and a

developing country

A developing country is a sovereign state with a lesser developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreem ...

that is highly dependent on commodities, namely petroleum and agricultural products. It is governed as a democratic

presidential republic. The country is a founding member of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

,

Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS; es, Organización de los Estados Americanos, pt, Organização dos Estados Americanos, french: Organisation des États américains; ''OEA'') is an international organization that was founded on 30 April ...

,

Mercosur

The Southern Common Market, commonly known by Spanish abbreviation Mercosur, and Portuguese Mercosul, is a South American trade bloc established by the Treaty of Asunción in 1991 and Protocol of Ouro Preto in 1994. Its full members are Argentina ...

,

PROSUR and the

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath o ...

.

One of 17

megadiverse countries in the world,

[, Conservation.org (16 September 2003).] Ecuador hosts many

endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

plants and animals, such as those of the

Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands (Spanish: , , ) are an archipelago of volcanic islands. They are distributed on each side of the equator in the Pacific Ocean, surrounding the centre of the Western Hemisphere, and are part of the Republic of Ecuador ...

. In recognition of its unique ecological heritage, the new constitution of 2008 is the first in the world to recognize legally enforceable

Rights of Nature

Rights of nature or Earth rights is a legal and jurisprudential theory that describes inherent rights as associated with ecosystems and species, similar to the concept of fundamental human rights. The rights of nature concept challenges twentie ...

, or ecosystem rights.

According to the

Center for Economic and Policy Research

The Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) is a progressive American think tank that specializes in economic policy. Based in Washington, D.C. CEPR was co-founded by economists Dean Baker and Mark Weisbrot in 1999.

Considered a left-lea ...

, between 2006 and 2016, poverty decreased from 36.7% to 22.5% and annual per capita GDP growth was 1.5 percent (as compared to 0.6 percent over the prior two decades). At the same time, the country's

Gini index of economic inequality decreased from 0.55 to 0.47.

Etymology

The country's name means "

Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

" in Spanish, truncated from the Spanish official name, ''República del Ecuador'' ( "Republic of the Equator"), derived from the former

Ecuador Department

Ecuador Department was one of the departments of Gran Colombia.

It had borders to:

* Azuay Department in the South.

* Guayaquil Department in the West.

Subdivisions

3 provincias and 15 cantones:

* Pichincha Province. Capital: Quito. Cantones: ...

of

Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia (, "Great Colombia"), or Greater Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia (Spanish: ''República de Colombia''), was a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 18 ...

established in 1824 as a division of the former territory of the

Royal Audience of Quito

The of Quito (sometimes referred to as or ) was an administrative unit in the Spanish Empire which had political, military, and religious jurisdiction over territories that today include Ecuador, parts of northern Peru, parts of southern Colo ...

. Quito, which remained the capital of the department and republic, is located only about , of a

degree

Degree may refer to:

As a unit of measurement

* Degree (angle), a unit of angle measurement

** Degree of geographical latitude

** Degree of geographical longitude

* Degree symbol (°), a notation used in science, engineering, and mathematics

...

, south of the equator.

History

Pre-Inca era

Various peoples had settled in the area of future Ecuador before the arrival of the

Incas

The Inca Empire (also Quechuan and Aymaran spelling shift, known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechuan languages, Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) wa ...

. The archeological evidence suggests that the

Paleo-Indians' first dispersal into the Americas occurred near the end of the

last glacial period, around 16,500–13,000 years ago. The first people who reached Ecuador may have journeyed by land from

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and

Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

or by boat down the Pacific Ocean coastline.

Even though their languages were unrelated, these groups developed similar groups of cultures, each based in different environments. The people of the coast developed a fishing, hunting, and gathering culture; the people of the highland Andes developed a sedentary agricultural way of life, and the people of the Amazon basin developed a nomadic hunting-and-gathering mode of existence.

Over time these groups began to interact and intermingle with each other so that groups of families in one area became one community or tribe, with a similar language and culture. Many civilizations arose in Ecuador, such as the

Valdivia Culture

The Valdivia culture is one of the oldest settled cultures recorded in the Americas. It emerged from the earlier Las Vegas culture and thrived on the Santa Elena peninsula near the modern-day town of Valdivia, Ecuador between 3500 BCE and 1500 BCE ...

and

Machalilla Culture

The Machalilla were a prehistoric people in Ecuador, in southern Manabí and the Santa Elena Peninsula. The dates when the culture thrived are uncertain, but are generally agreed to encompass 1500 BCE to 1100 BCE. on the coast, the

Quitus

''Quitus'' is a genus of grasshoppers in the subfamily Romaleinae

Romaleinae is a subfamily of lubber grasshoppers in the family Romaleidae, found in North and South America. More than 60 genera and 260 described species are placed in the Romal ...

(near present-day Quito), and the

Cañari

The Cañari (in Kichwa: Kañari) are an indigenous ethnic group traditionally inhabiting the territory of the modern provinces of Azuay and Cañar in Ecuador. They are descended from the independent pre-Columbian tribal confederation of the s ...

(near present-day

Cuenca). Each civilisation developed its own distinctive architecture, pottery, and religious interests.

In the highland Andes mountains, where life was more sedentary, groups of tribes cooperated and formed villages; thus the first nations based on agricultural resources and the domestication of animals formed. Eventually, through wars and marriage alliances of their

leader

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets vi ...

s, a group of nations formed confederations. One region consolidated under a confederation called the

Shyris, which exercised organized trading and bartering between the different regions. Its political and military power came under the rule of the Duchicela blood-line.

Inca era

When the

Incas

The Inca Empire (also Quechuan and Aymaran spelling shift, known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechuan languages, Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) wa ...

arrived, they found that these confederations were so developed that it took the Incas two generations of rulers—

Topa Inca Yupanqui

Topa Inca Yupanqui or Túpac Inca Yupanqui ( qu, 'Tupaq Inka Yupanki'), translated as "noble Inca accountant," (c. 1441–c. 1493) was the tenth Sapa Inca (1471–93) of the Inca Empire, fifth of the Hanan dynasty. His father was Pachacuti, and h ...

and

Huayna Capac

Huayna Capac (with many alternative transliterations; 1464/1468–1524) was the third Sapan Inka of the Inca Empire, born in Tumipampa sixth of the Hanan dynasty, and eleventh of the Inca civilization. Subjects commonly approached Sapa Inkas addi ...

—to absorb them into the

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The admin ...

. The native confederations that gave them the most problems were deported to distant areas of Peru, Bolivia, and north Argentina. Similarly, a number of loyal Inca subjects from Peru and Bolivia were brought to Ecuador to prevent rebellion. Thus, the region of highland Ecuador became part of the

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The admin ...

in 1463 sharing the same language.

In contrast, when the Incas made incursions into coastal Ecuador and the eastern Amazon jungles of Ecuador, they found both the environment and indigenous people more hostile. Moreover, when the Incas tried to subdue them, these indigenous people withdrew to the interior and resorted to

guerrilla tactics. As a result, Inca expansion into the Amazon Basin and the Pacific coast of Ecuador was hampered. The indigenous people of the Amazon jungle and coastal Ecuador remained relatively autonomous until the Spanish soldiers and missionaries arrived in force. The Amazonian people and the

Cayapas of Coastal Ecuador were the only groups to resist Inca and Spanish domination, maintaining their language and culture well into the 21st century.

Before the arrival of the Spaniards, the Inca Empire was involved in a

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. The untimely death of both the heir Ninan Cuchi and the Emperor Huayna Capac, from a European disease that spread into Ecuador, created a power vacuum between two factions. The northern faction headed by Atahualpa claimed that Huayna Capac gave a verbal decree before his death about how the empire should be divided. He gave the territories pertaining to present-day Ecuador and northern Peru to his favorite son Atahualpa, who was to rule from Quito; and he gave the rest to

Huáscar

Huáscar Inca (; Quechua: ''Waskar Inka''; 1503–1532) also Guazcar was Sapa Inca of the Inca Empire from 1527 to 1532. He succeeded his father, Huayna Capac and his brother Ninan Cuyochi, both of whom died of smallpox while campaigning near Qui ...

, who was to rule from

Cuzco

Cusco, often spelled Cuzco (; qu, Qusqu ()), is a city in Southeastern Peru near the Urubamba Valley of the Andes mountain range. It is the capital of the Cusco Region and of the Cusco Province. The city is the seventh most populous in Peru; ...

. He willed that his heart be buried in Quito, his favorite city, and the rest of his body be buried with his ancestors in Cuzco.

Huáscar did not recognize his father's will, since it did not follow Inca traditions of naming an Inca through the priests. Huáscar ordered Atahualpa to attend their father's burial in Cuzco and pay homage to him as the new Inca ruler. Atahualpa, with a large number of his father's veteran soldiers, decided to ignore Huáscar, and a civil war ensued. A number of bloody battles took place until finally Huáscar was captured. Atahualpa marched south to Cuzco and massacred the royal family associated with his brother.

In 1532, a small band of Spaniards headed by Francisco Pizarro landed in Tumbez and marched over the Andes Mountains until they reached Cajamarca, where the new Inca Atahualpa was to hold an interview with them. Valverde, the priest, tried to convince Atahualpa that he should join the Catholic Church and declare himself a vassal of Spain. This infuriated Atahualpa so much that he threw the Bible to the ground. At this point the enraged Spaniards, with orders from Valverde, attacked and massacred unarmed escorts of the Inca and captured Atahualpa.

Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of Peru.

Born in Trujillo, Spain to a poor family, Pizarro chose ...

promised to release Atahualpa if he made good his promise of filling a room full of gold. But, after a mock trial, the Spaniards executed Atahualpa by strangulation.

Spanish colonization

New infectious diseases such as

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, endemic to the Europeans, caused high fatalities among the Amerindian population during the first decades of Spanish rule, as they had no

immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

. At the same time, the natives were forced into the ''

encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

'' labor system for the Spanish. In 1563,

Quito

Quito (; qu, Kitu), formally San Francisco de Quito, is the capital and largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its urban area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha. Quito is located in a valley o ...

became the seat of a

real audiencia

A ''Real Audiencia'' (), or simply an ''Audiencia'' ( ca, Reial Audiència, Audiència Reial, or Audiència), was an appellate court in Spain and its empire. The name of the institution literally translates as Royal Audience. The additional des ...

(administrative district) of Spain and part of the

Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru ( es, Virreinato del Perú, links=no) was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America, governed from ...

and later the

Viceroyalty of New Granada

The Viceroyalty of New Granada ( es, Virreinato de Nueva Granada, links=no ) also called Viceroyalty of the New Kingdom of Granada or Viceroyalty of Santafé was the name given on 27 May 1717, to the jurisdiction of the Spanish Empire in norther ...

.

The

1797 Riobamba earthquake

The 1797 Riobamba earthquake occurred at 12:30 UTC on 4 February. It devastated the city of Riobamba and many other cities in the Interandean valley, causing between 6,000–40,000 casualties. It is estimated that seismic intensities in the ep ...

, which caused up to 40,000 casualties, was studied by

Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, p ...

, when he visited the area in 1801–1802.

After nearly 300 years of Spanish rule, Quito still remained small with a population of 10,000 people. On 10 August 1809, the city's ''

criollos

In Hispanic America, criollo () is a term used originally to describe people of Spanish descent born in the colonies. In different Latin American countries the word has come to have different meanings, sometimes referring to the local-born majo ...

'' called for independence from Spain (first among the peoples of Latin America). They were led by Juan Pío Montúfar, Quiroga, Salinas, and Bishop Cuero y Caicedo. Quito's nickname, "''

Luz de América

The Ecuadorian War of Independence was fought from 1820 to 1822 between several South American armies and Spain over control of the lands of the Royal Audience of Quito, a Spanish colonial administrative jurisdiction from which would eventually ...

''" ("Light of America"), is based on its leading role in trying to secure an independent, local government. Although the new government lasted no more than two months, it had important repercussions and was an inspiration for the independence movement of the rest of Spanish America. 10 August is now celebrated as Independence Day, a

national holiday National holiday may refer to:

* National day, a day when a nation celebrates a very important event in its history, such as its establishment

*Public holiday, a holiday established by law, usually a day off for at least a portion of the workforce, ...

.

Independence

On 9 October 1820, the Department of

Guayaquil

, motto = Por Guayaquil Independiente en, For Independent Guayaquil

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Ecuador#South America

, pushpin_re ...

became the first territory in Ecuador to gain its independence from Spain, and it spawned most of the Ecuadorian coastal provinces, establishing itself as an independent state. Its inhabitants celebrated what is now Ecuador's official Independence Day on 24 May 1822. The rest of Ecuador gained its independence after

Antonio José de Sucre

Antonio José de Sucre y Alcalá (; 3 February 1795 – 4 June 1830), known as the "Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho" ( en, "Grand Marshal of Ayacucho"), was a Venezuelan independence leader who served as the president of Peru and as the second pr ...

defeated the Spanish Royalist forces at the

Battle of Pichincha

The Battle of Pichincha took place on 24 May 1822, on the slopes of the Pichincha volcano, 3,500 meters above sea-level, right next to the city of Quito, in modern Ecuador.

The encounter, fought in the context of the Spanish American wars of in ...

, near

Quito

Quito (; qu, Kitu), formally San Francisco de Quito, is the capital and largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its urban area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha. Quito is located in a valley o ...

. Following the battle, Ecuador joined

Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24 July 1783 – 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama and B ...

's

Republic of Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia (, "Great Colombia"), or Greater Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia (Spanish: ''República de Colombia''), was a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 18 ...

, also including modern-day

Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

,

Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

and

Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cos ...

. In 1830, Ecuador separated from Gran Colombia and became an independent republic. Two years later, it annexed the

Galapagos Islands.

The 19th century was marked by instability for Ecuador with a rapid succession of rulers. The first president of Ecuador was the Venezuelan-born

Juan José Flores

Juan José Flores y Aramburu (19 July 1800 – 1 October 1864) was a Venezuelan-born military general who became the first (in 1830), third (in 1839) and fourth (in 1843) President of the new Republic of Ecuador. He is often referred to as "The ...

, who was ultimately deposed, followed by several authoritarian leaders, such as

Vicente Rocafuerte

Vicente Rocafuerte y Bejarano (1 May 1783 – 16 May 1847) was an influential figure in Ecuadorian politics and President of Ecuador from 10 September 1834 to 31 January 1839.

He was born into an aristocratic family in Guayaquil, Ecuador, an ...

;

José Joaquín de Olmedo

José Joaquín de Olmedo y Maruri (20 March 1780 – 19 February 1847) was President of Ecuador from 6 March 1845 to 8 December 1845. A patriot and poet, he was the son of the Spanish Captain Don Miguel de Olmedo y Troyano and the Guayaquilean An ...

;

José María Urbina

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernacul ...

;

Diego Noboa

Diego de Noboa y Arteta (15 April 1789, in Guayaquil – 3 November 1870) was President of Ecuador from 8 December 1850 to 26 February 1851 (interim) and 26 February 1851 to 17 July 1851. He was President of the Senate in 1839 and 1848.

In 18 ...

;

Pedro José de Arteta

Pedro José de Arteta y Calisto (1797 in Quito – 24 August 1873) was Vice President of Ecuador from 1865 to 1869 and served briefly as President from 6 November 1867 to 20 January 1868. He was President of the Senate in 1839. He was the brother ...

;

Manuel de Ascásubi

Manuel de Ascázubi y Matheu (30 December 1804 – 25 December 1876) served as Vice President of Ecuador from 1847 to 1849 and in that capacity he was also interim List of heads of state of Ecuador, President from 16 October 1849 to 10 June 1850.

...

; and Flores's own son,

Antonio Flores Jijón

Juan Antonio María Flores y Jijón de Vivanco (23 October 1833 – 30 August 1915) as 13th President of Ecuador 17 August 1888 to 30 June 1892.

He was a member of the Progressive Party, a Liberal Catholic party.

Antonio Flores was born in Q ...

, among others. The conservative

Gabriel García Moreno

Gabriel Gregorio Fernando José María García Moreno y Morán de Butrón (24 December 1821 – 6 August 1875), was an Ecuadorian politician and aristocrat who twice served as President of Ecuador (1861–65 and 1869–75) and was assassinated d ...

unified the country in the 1860s with the support of the Roman Catholic Church. In the late 19th century, world demand for

cocoa

Cocoa may refer to:

Chocolate

* Chocolate

* ''Theobroma cacao'', the cocoa tree

* Cocoa bean, seed of ''Theobroma cacao''

* Chocolate liquor, or cocoa liquor, pure, liquid chocolate extracted from the cocoa bean, including both cocoa butter and ...

tied the economy to commodity exports and led to migrations from the highlands to the agricultural frontier on the coast.

Ecuador

abolished slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and freed its

black slaves

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

in 1851.

Liberal Revolution

The Liberal Revolution of 1895 under

Eloy Alfaro

José Eloy Alfaro Delgado (25 June 1842 – 28 January 1912) often referred to as "The Old Warrior," was an Ecuadorian politician who served as the President of Ecuador from 1895 to 1901 and from 1906 to 1911. Eloy Alfaro emerged as the leader ...

reduced the power of the clergy and the conservative land owners. This liberal wing retained power until the military "Julian Revolution" of 1925. The 1930s and 1940s were marked by instability and emergence of populist politicians, such as five-time President

José María Velasco Ibarra

José María Velasco Ibarra (19 March 1893 – 30 March 1979) was an Ecuadorian politician. He became president of Ecuador five times, in 1934–1935, 1944–1947, 1952–1956, 1960–1961, and 1968–1972, and only in 1952–1956 he complete ...

.

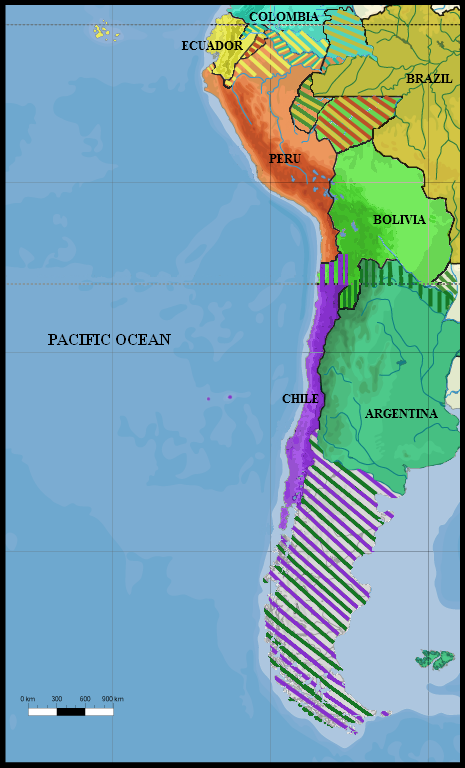

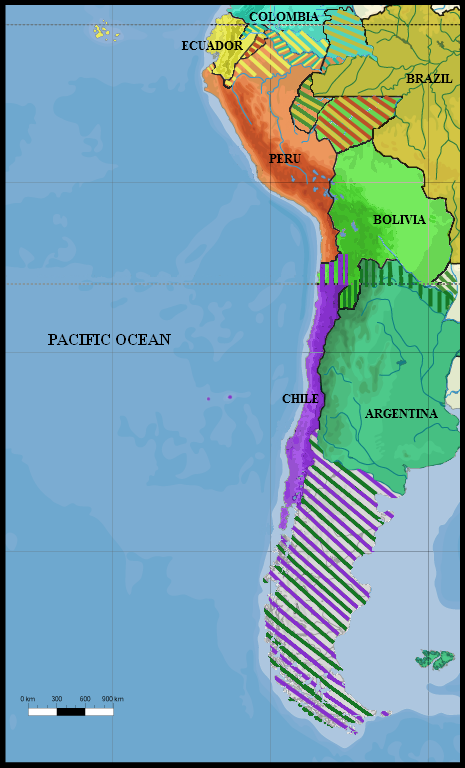

Loss of claimed territories since 1830

President Juan José Flores de jure territorial claims

Since Ecuador's separation from Colombia on 13 May 1830, its first President, General

Juan José Flores

Juan José Flores y Aramburu (19 July 1800 – 1 October 1864) was a Venezuelan-born military general who became the first (in 1830), third (in 1839) and fourth (in 1843) President of the new Republic of Ecuador. He is often referred to as "The ...

, laid claim to the territory that was called the

Real Audiencia of Quito

The of Quito (sometimes referred to as or ) was an administrative unit in the Spanish Empire which had political, military, and religious jurisdiction over territories that today include Ecuador, parts of northern Peru, parts of southern Col ...

, also referred to as the Presidencia of Quito. He supported his claims with Spanish Royal decrees or ''Real Cedulas'', that delineated the borders of Spain's former overseas colonies. In the case of Ecuador, Flores-based Ecuador's ''

de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' claims on the following cedulas – Real Cedula of 1563, 1739, and 1740; with modifications in the Amazon Basin and Andes Mountains that were introduced through the

Treaty of Guayaquil

The Treaty of Guayaquil, officially the Treaty of Peace Between Colombia and Peru, and also known as the Larrea–Gual Treaty after its signatories, was a peace treaty signed between Gran Colombia and Peru in 1829 that officially put an end to the ...

(1829) which Peru reluctantly signed, after the overwhelmingly outnumbered Gran Colombian force led by

Antonio José de Sucre

Antonio José de Sucre y Alcalá (; 3 February 1795 – 4 June 1830), known as the "Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho" ( en, "Grand Marshal of Ayacucho"), was a Venezuelan independence leader who served as the president of Peru and as the second pr ...

defeated President and General La Mar's Peruvian invasion force in the

Battle of Tarqui

The Battle of Tarqui, also known as the Battle of Portete de Tarqui, took place on 27 February 1829 at Tarqui, near Cuenca, today part of Ecuador. It was fought between troops from Gran Colombia, commanded by Antonio José de Sucre, and Peruvian ...

. In addition, Ecuador's eastern border with the Portuguese colony of Brazil in the Amazon Basin was modified before the wars of Independence by the

First Treaty of San Ildefonso

The First Treaty of San Ildefonso was signed on 1 October 1777 between Spain and Portugal. It settled long-running territorial disputes between the two kingdoms' possessions in South America, primarily in the Río de la Plata region.

Background

...

(1777) between the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

and the

Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire ( pt, Império Português), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (''Ultramar Português'') or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (''Império Colonial Português''), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and the l ...

. Moreover, to add legitimacy to his claims, on 16 February 1840, Flores signed a treaty with Spain, whereby Flores convinced Spain to officially recognize Ecuadorian independence and its sole rights to colonial titles over Spain's former colonial territory known anciently to Spain as the Kingdom and Presidency of Quito.

Ecuador during its long and turbulent history has lost most of its contested territories to each of its more powerful neighbors, such as Colombia in 1832 and 1916, Brazil in 1904 through a series of peaceful treaties, and Peru after a short war in which the Protocol of Rio de Janeiro was signed in 1942.

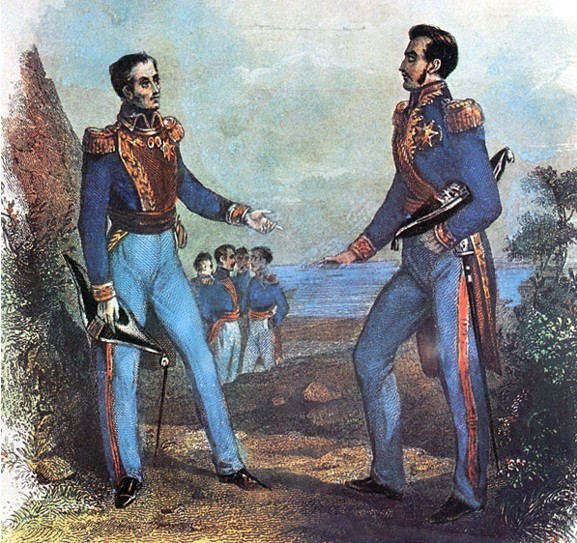

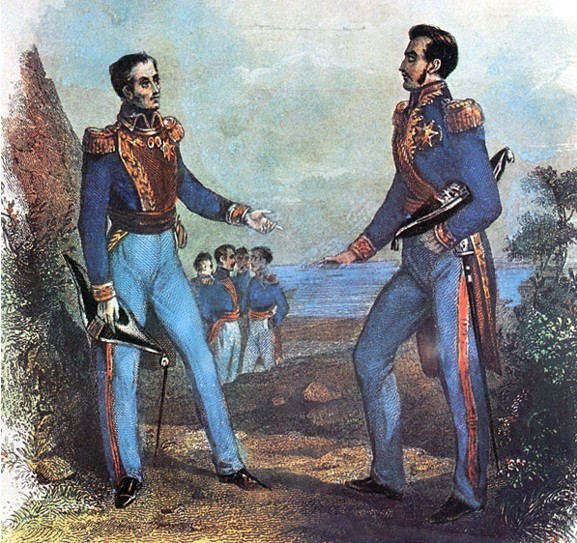

Struggle for independence

During the

struggle for independence, before Peru or Ecuador became independent nations, a few areas of the former Vice Royalty of New Granada – Guayaquil, Tumbez, and Jaén – declared themselves independent from Spain. A few months later, a part of the Peruvian liberation army of San Martin decided to occupy the independent cities of Tumbez and Jaén with the intention of using these towns as springboards to occupy the independent city of Guayaquil and then to liberate the rest of the Audiencia de Quito (Ecuador). It was common knowledge among the top officers of the liberation army from the south that their leader

San Martin wished to liberate present-day Ecuador and add it to the future republic of Peru, since it had been part of the Inca Empire before the Spaniards conquered it.

However,

Bolívar's intention was to form a new republic known as the Gran Colombia, out of the liberated Spanish territory of New Granada which consisted of Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. San Martin's plans were thwarted when

Bolívar, with the help of Marshal Antonio José de Sucre and the Gran Colombian liberation force, descended from the Andes mountains and occupied Guayaquil; they also annexed the newly liberated Audiencia de Quito to the Republic of

Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia (, "Great Colombia"), or Greater Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia (Spanish: ''República de Colombia''), was a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 18 ...

. This happened a few days before San Martin's Peruvian forces could arrive and occupy Guayaquil, with the intention of annexing Guayaquil to the rest of Audiencia of Quito (Ecuador) and to the future republic of Peru. Historic documents repeatedly stated that San Martin told Bolivar he came to Guayaquil to liberate the land of the Incas from Spain. Bolivar countered by sending a message from Guayaquil welcoming San Martin and his troops to Colombian soil.

Peruvian occupation of Jaén, Tumbes, and Guayaquil

In the south, Ecuador had ''de jure'' claims to a small piece of land beside the Pacific Ocean known as

Tumbes which lay between the

Zarumilla and

Tumbes rivers. In Ecuador's southern Andes Mountain region where the Marañon cuts across, Ecuador had ''de jure'' claims to an area it called

Jaén de Bracamoros. These areas were included as part of the territory of Gran Colombia by Bolivar on 17 December 1819, during the

Congress of Angostura

The Congress of Angostura was convened by Simón Bolívar and took place in Angostura (today Ciudad Bolívar) during the wars of Independence of Colombia and Venezuela, culminating in the proclamation of the Republic of Colombia (historiograph ...

when the Republic of Gran Colombia was created. Tumbes declared itself independent from Spain on 17 January 1821, and Jaen de Bracamoros on 17 June 1821, without any outside help from revolutionary armies. However, that same year, 1821, Peruvian forces participating in the Trujillo revolution occupied both Jaen and Tumbes. Some Peruvian generals, without any legal titles backing them up and with Ecuador still federated with the Gran Colombia, had the desire to annex Ecuador to the Republic of Peru at the expense of the Gran Colombia, feeling that Ecuador was once part of the Inca Empire.

On 28 July 1821, Peruvian independence was proclaimed in Lima by the Liberator San Martin, and Tumbes and Jaen, which were included as part of the revolution of Trujillo by the Peruvian occupying force, had the whole region swear allegiance to the new Peruvian flag and incorporated itself into Peru, even though Peru was not completely liberated from Spain. After Peru was completely liberated from Spain by the patriot armies led by Bolivar and Antonio Jose de Sucre at the

Battle of Ayacucho

The Battle of Ayacucho ( es, Batalla de Ayacucho, ) was a decisive military encounter during the Peruvian War of Independence. This battle secured the independence of Peru and ensured independence for the rest of South America. In Peru it is co ...

dated 9 December 1824, there was a strong desire by some Peruvians to resurrect the

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The admin ...

and to include Bolivia and Ecuador. One of these Peruvian Generals was the Ecuadorian-born

José de La Mar

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernacul ...

, who became one of Peru's presidents after Bolivar resigned as dictator of Peru and returned to Colombia. Gran Colombia had always protested Peru for the return of Jaen and Tumbes for almost a decade, then finally Bolivar after long and futile discussion over the return of Jaen, Tumbes, and part of Mainas, declared war. President and General

José de La Mar

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernacul ...

, who was born in Ecuador, believing his opportunity had come to annex the District of Ecuador to Peru, personally, with a Peruvian force, invaded and occupied Guayaquil and a few cities in the Loja region of southern Ecuador on 28 November 1828.

The war ended when a triumphant heavily outnumbered southern Gran Colombian army at

Battle of Tarqui

The Battle of Tarqui, also known as the Battle of Portete de Tarqui, took place on 27 February 1829 at Tarqui, near Cuenca, today part of Ecuador. It was fought between troops from Gran Colombia, commanded by Antonio José de Sucre, and Peruvian ...

dated 27 February 1829, led by

Antonio José de Sucre

Antonio José de Sucre y Alcalá (; 3 February 1795 – 4 June 1830), known as the "Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho" ( en, "Grand Marshal of Ayacucho"), was a Venezuelan independence leader who served as the president of Peru and as the second pr ...

, defeated the Peruvian invasion force led by President La Mar. This defeat led to the signing of the Treaty of Guayaquil dated 22 September 1829, whereby Peru and its Congress recognized Gran Colombian rights over Tumbes, Jaen, and Maynas. Through protocolized meetings between representatives of Peru and Gran Colombia, the border was set as Tumbes river in the west and in the east the Maranon and Amazon rivers were to be followed toward Brazil as the most natural borders between them. However, what was pending was whether the new border around the Jaen region should follow the Chinchipe River or the Huancabamba River. According to the peace negotiations Peru agreed to return Guayaquil, Tumbez, and Jaén; despite this, Peru returned Guayaquil, but failed to return Tumbes and Jaén, alleging that it was not obligated to follow the agreements, since the Gran Colombia ceased to exist when it divided itself into three different nations – Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela.

The dissolution of Gran Colombia

The Central District of the Gran Colombia, known as Cundinamarca or New Granada (modern Colombia) with its capital in Bogota, did not recognize the separation of the Southern District of the Gran Colombia, with its capital in Quito, from the Gran Colombian federation on 13 May 1830. After Ecuador's separation, the

Department of Cauca voluntarily decided to unite itself with Ecuador due to instability in the central government of Bogota. The Venezuelan born President of Ecuador, the general

Juan José Flores

Juan José Flores y Aramburu (19 July 1800 – 1 October 1864) was a Venezuelan-born military general who became the first (in 1830), third (in 1839) and fourth (in 1843) President of the new Republic of Ecuador. He is often referred to as "The ...

, with the approval of the Ecuadorian congress annexed the Department of Cauca on 20 December 1830, since the government of Cauca had called for union with the District of the South as far back as April 1830. Moreover, the Cauca region, throughout its long history, had very strong economic and cultural ties with the people of Ecuador. Also, the Cauca region, which included such cities as

Pasto

Pasto, officially San Juan de Pasto (; "Saint John of Pasto"), is the capital of the department of Nariño, in southern Colombia. Pasto was founded in 1537 and named after indigenous people of the area. In the 2018 census, the city had appr ...

,

Popayán

Popayán () is the capital of the Colombian departments of Colombia, department of Cauca Department, Cauca. It is located in southwestern Colombia between the Cordillera Occidental (Colombia), Western Mountain Range and Cordillera Central (Colo ...

, and

Buenaventura, had always been dependent on the Presidencia or Audiencia of Quito.

Fruitless negotiations continued between the governments of Bogotá and Quito, where the government of Bogotá did not recognize the separation of Ecuador or that of Cauca from the Gran Colombia until war broke out in May 1832. In five months, New Granada defeated Ecuador due to the fact that the majority of the Ecuadorian Armed Forces were composed of rebellious angry unpaid veterans from Venezuela and Colombia that did not want to fight against their fellow countrymen. Seeing that his officers were rebelling, mutinying, and changing sides, President Flores had no option but to reluctantly make peace with New Granada. The Treaty of Pasto of 1832 was signed by which the Department of Cauca was turned over to New Granada (modern Colombia), the government of Bogotá recognized Ecuador as an independent country and the border was to follow the Ley de División Territorial de la República de Colombia (Law of the Division of Territory of the Gran Colombia) passed on 25 June 1824. This law set the border at the river Carchi and the eastern border that stretched to Brazil at the Caquetá river. Later, Ecuador contended that the Republic of Colombia, while reorganizing its government, unlawfully made its eastern border provisional and that Colombia extended its claims south to the Napo River because it said that the Government of Popayán extended its control all the way to the Napo River.

Struggle for possession of the Amazon Basin

When Ecuador seceded from the Gran Colombia, Peru decided not to follow the treaty of Guayaquil of 1829 or the protocoled agreements made. Peru contested Ecuador's claims with the newly discovered ''Real Cedula'' of 1802, by which Peru claims the King of Spain had transferred these lands from the Viceroyalty of New Granada to the Viceroyalty of Peru. During colonial times this was to halt the ever-expanding Portuguese settlements into Spanish domains, which were left vacant and in disorder after the expulsion of Jesuit missionaries from their bases along the Amazon Basin. Ecuador countered by labeling the Cedula of 1802 an ecclesiastical instrument, which had nothing to do with political borders. Peru began its de facto occupation of disputed Amazonian territories, after it signed a secret 1851 peace treaty in favor of Brazil. This treaty disregarded Spanish rights that were confirmed during colonial times by a Spanish-Portuguese treaty over the Amazon regarding territories held by illegal Portuguese settlers.

Peru began occupying the missionary villages in the Mainas or Maynas region, which it began calling Loreto, with its capital in

Iquitos

Iquitos (; ) is the capital city of Peru's Maynas Province and Loreto Region. It is the largest metropolis in the Peruvian Amazon, east of the Andes, as well as the ninth-most populous city of Peru. Iquitos is the largest city in the world th ...

. During its negotiations with Brazil, Peru claimed Amazonian Basin territories up to Caqueta River in the north and toward the Andes Mountain range. Colombia protested stating that its claims extended south toward the Napo and Amazon Rivers. Ecuador protested that it claimed the Amazon Basin between the Caqueta river and the Marañon-Amazon river. Peru ignored these protests and created the Department of Loreto in 1853 with its capital in Iquitos. Peru briefly occupied Guayaquil again in 1860, since Peru thought that Ecuador was selling some of the disputed land for development to British bond holders, but returned Guayaquil after a few months. The border dispute was then submitted to Spain for arbitration from 1880 to 1910, but to no avail.

In the early part of the 20th century, Ecuador made an effort to peacefully define its eastern Amazonian borders with its neighbours through negotiation. On 6 May 1904, Ecuador signed the Tobar-Rio Branco Treaty recognizing Brazil's claims to the Amazon in recognition of Ecuador's claim to be an Amazonian country to counter Peru's earlier Treaty with Brazil back on 23 October 1851. Then after a few meetings with the Colombian government's representatives an agreement was reached and the Muñoz Vernaza-Suarez Treaty was signed 15 July 1916, in which Colombian rights to the Putumayo river were recognized as well as Ecuador's rights to the Napo river and the new border was a line that ran midpoint between those two rivers. In this way, Ecuador gave up the claims it had to the Amazonian territories between the Caquetá River and Napo River to Colombia, thus cutting itself off from Brazil. Later, a brief war erupted between Colombia and Peru, over Peru's claims to the Caquetá region, which ended with Peru reluctantly signing the Salomon-Lozano Treaty on 24 March 1922. Ecuador protested this secret treaty, since Colombia gave away Ecuadorian claimed land to Peru that Ecuador had given to Colombia in 1916.

On 21 July 1924, the Ponce-Castro Oyanguren Protocol was signed between Ecuador and Peru where both agreed to hold direct negotiations and to resolve the dispute in an equitable manner and to submit the differing points of the dispute to the United States for arbitration. Negotiations between the Ecuadorian and Peruvian representatives began in Washington on 30 September 1935. These negotiations were long and tiresome. Both sides logically presented their cases, but no one seemed to give up their claims. Then on 6 February 1937, Ecuador presented a transactional line which Peru rejected the next day. The negotiations turned into intense arguments during the next 7 months and finally on 29 September 1937, the Peruvian representatives decided to break off the negotiations without submitting the dispute to arbitration because the direct negotiations were going nowhere.

Four years later in 1941, amid fast-growing tensions within disputed territories around the Zarumilla River, war broke out with Peru. Peru claimed that Ecuador's military presence in Peruvian-claimed territory was an invasion; Ecuador, for its part, claimed that Peru had recently invaded Ecuador around the Zarumilla River and that Peru since Ecuador's independence from Spain has systematically occupied Tumbez, Jaen, and most of the disputed territories in the Amazonian Basin between the Putomayo and Marañon Rivers. In July 1941, troops were mobilized in both countries. Peru had an army of 11,681 troops who faced a poorly supplied and inadequately armed Ecuadorian force of 2,300, of which only 1,300 were deployed in the southern provinces. Hostilities erupted on 5 July 1941, when Peruvian forces crossed the Zarumilla river at several locations, testing the strength and resolve of the Ecuadorian border troops. Finally, on 23 July 1941, the Peruvians launched a major invasion, crossing the Zarumilla river in force and advancing into the Ecuadorian province of

El Oro.

During the course of the

Ecuadorian–Peruvian War

The Ecuadorian–Peruvian War, known locally as the War of '41 ( es, link=no, Guerra del 41), was a South American border war fought between 5–31 July 1941. It was the first of three military conflicts between Ecuador and Peru during the 20th ...

, Peru gained control over part of the disputed territory and some parts of the province of El Oro, and some parts of the

province of Loja, demanding that the Ecuadorian government give up its territorial claims. The Peruvian Navy blocked the port of

Guayaquil

, motto = Por Guayaquil Independiente en, For Independent Guayaquil

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Ecuador#South America

, pushpin_re ...

, almost cutting all supplies to the Ecuadorian troops. After a few weeks of war and under pressure by the United States and several Latin American nations, all fighting came to a stop. Ecuador and Peru came to an accord formalized in the

Rio Protocol

The Protocol of Peace, Friendship, and Boundaries between Peru and Ecuador, or Rio Protocol for short, was an international agreement signed in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on January 29, 1942, by the foreign ministers of Peru and Ecuador, with t ...

, signed on 29 January 1942, in favor of hemispheric unity against the

Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

favoring Peru with the territory they occupied at the time the war came to an end.

The 1944

Glorious May Revolution followed a military-civilian rebellion and a subsequent civic strike which successfully removed Carlos Arroyo del Río as a dictator from Ecuador's government. However, a post-Second World War recession and popular unrest led to a return to populist politics and domestic military interventions in the 1960s, while foreign companies developed oil resources in the Ecuadorian Amazon. In 1972, construction of the Andean pipeline was completed. The pipeline brought oil from the east side of the Andes to the coast, making Ecuador South America's second largest oil exporter. The pipeline in southern Ecuador did nothing to resolve tensions between Ecuador and Peru, however.

In 1978, the city of

Quito

Quito (; qu, Kitu), formally San Francisco de Quito, is the capital and largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its urban area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha. Quito is located in a valley o ...

and the

Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands (Spanish: , , ) are an archipelago of volcanic islands. They are distributed on each side of the equator in the Pacific Ocean, surrounding the centre of the Western Hemisphere, and are part of the Republic of Ecuador ...

were inscribed as

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

, making the first two properties in the world to become listed sites.

The

Rio Protocol

The Protocol of Peace, Friendship, and Boundaries between Peru and Ecuador, or Rio Protocol for short, was an international agreement signed in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on January 29, 1942, by the foreign ministers of Peru and Ecuador, with t ...

failed to precisely resolve the border along a little river in the remote ''Cordillera del Cóndor'' region in southern Ecuador. This caused a long-simmering dispute between Ecuador and Peru, which ultimately led to fighting between the two countries; first a border skirmish in January–February 1981 known as the

Paquisha Incident

The Paquisha War or Fake Paquisha War () was a military clash that took place between January and February 1981 between Ecuador and Peru over the control of three watchposts. While Peru felt that the matter was already decided in the Ecuadorian� ...

, and ultimately full-scale warfare in January 1995 where the Ecuadorian military shot down Peruvian aircraft and helicopters and Peruvian infantry marched into southern Ecuador. Each country blamed the other for the onset of hostilities, known as the

Cenepa War

The Cenepa War (26 January – 28 February 1995), also known as the Alto Cenepa War, was a brief and localized military conflict between Ecuador and Peru, fought over control of an area in Peruvian territory (i.e. in the eastern side of the Cord ...

.

Sixto Durán Ballén

Sixto Alfonso Durán-Ballén Cordovez (14 July 1921 – 15 November 2016) was an Ecuadorian political figure and architect. He served as Mayor of Quito between 1970 and 1978. In 1951, he co-founded a political party, the Social Christian Party. ...

, the Ecuadorian president, famously declared that he would not give up a single centimeter of Ecuador. Popular sentiment in Ecuador became strongly

nationalistic

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

against Peru: graffiti could be seen on the walls of Quito referring to Peru as the "''Cain de Latinoamérica''", a reference to the murder of

Abel

Abel ''Hábel''; ar, هابيل, Hābīl is a Biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He was the younger brother of Cain, and the younger son of Adam and Eve, the first couple in Biblical history. He was a shepher ...

by his brother

Cain

Cain ''Káïn''; ar, قابيل/قايين, Qābīl/Qāyīn is a Biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He is the elder brother of Abel, and the firstborn son of Adam and Eve, the first couple within the Bible. He wa ...

in the

Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek ; Hebrew: בְּרֵאשִׁית ''Bəreʾšīt'', "In hebeginning") is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its first word, ( "In the beginning") ...

.

Ecuador and Peru signed the

Brasilia Presidential Act

The Brasilia Presidential Act ( es, Acta Presidencial de Brasilia, pt, Ato Presidencial de Brasília), also known as the Fujimori–Mahuad Treaty ( es, Tratado Fujimori–Mahuad), is an international treaty signed in Brasilia by the then Presiden ...

peace agreement on 26 October 1998, which ended hostilities, and effectively put an end to the Western Hemisphere's longest running territorial dispute.

The Guarantors of the

Rio Protocol

The Protocol of Peace, Friendship, and Boundaries between Peru and Ecuador, or Rio Protocol for short, was an international agreement signed in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on January 29, 1942, by the foreign ministers of Peru and Ecuador, with t ...

(Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and the United States of America) ruled that the border of the undelineated zone was to be set at the line of the ''Cordillera del Cóndor''. While Ecuador had to give up its decades-old territorial claims to the eastern slopes of the Cordillera, as well as to the entire western area of Cenepa headwaters, Peru was compelled to give to Ecuador, in perpetual lease but without sovereignty, of its territory, in the area where the Ecuadorian base of Tiwinza – focal point of the war – had been located within Peruvian soil and which the Ecuadorian Army held during the conflict. The final border demarcation came into effect on 13 May 1999, and the multi-national MOMEP (Military Observer Mission for Ecuador and Peru) troop deployment withdrew on 17 June 1999.

Military governments (1972–79)

In 1972, a "revolutionary and nationalist" military

junta

Junta may refer to:

Government and military

* Junta (governing body) (from Spanish), the name of various historical and current governments and governing institutions, including civil ones

** Military junta, one form of junta, government led by ...

overthrew the government of Velasco Ibarra. The

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

was led by General

Guillermo Rodríguez and executed by navy commander Jorge Queirolo G. The new president exiled José María Velasco to Argentina. He remained in power until 1976, when he was removed by another military government. That military junta was led by Admiral

Alfredo Poveda

Alfredo Ernesto Poveda Burbano (January 24, 1926 – June 7, 1990) was an Interim President of Ecuador January 11, 1976, to August 10, 1979.

Background

Poveda was born in Ambato on January 24, 1926. He attended Mejía High School in Quito an ...

, who was declared chairman of the Supreme Council. The Supreme Council included two other members: General Guillermo Durán Arcentales and General Luis Pintado. The civil society more and more insistently called for democratic elections. Colonel

Richelieu Levoyer, Government Minister, proposed and implemented a Plan to return to the constitutional system through universal elections. This plan enabled the new democratically elected president to assume the duties of the executive office.

Return to democracy

Elections were held on 29 April 1979, under a new constitution.

Jaime Roldós Aguilera

Jaime Roldós Aguilera (5 November 1940 – 24 May 1981) was 33rd President of Ecuador from 10 August 1979 until his death on 24 May 1981. In his short tenure, he became known for his firm stance on human rights.

Early life and career

Roldós ...

was elected president, garnering over one million votes, the most in Ecuadorian history. He took office on 10 August, as the first constitutionally elected president after nearly a decade of civilian and military dictatorships. In 1980, he founded the ''Partido Pueblo, Cambio y Democracia'' (People, Change, and Democracy Party) after withdrawing from the ''Concentración de Fuerzas Populares'' (Popular Forces Concentration) and governed until 24 May 1981, when he died along with his wife and the minister of defense,

Marco Subia Martinez, when his Air Force plane crashed in heavy rain near the Peruvian border. Many people believe that he was assassinated by the CIA, given the multiple death threats leveled against him because of his reformist agenda, deaths in automobile crashes of two key witnesses before they could testify during the investigation, and the sometimes contradictory accounts of the incident.

Roldos was immediately succeeded by Vice President Osvaldo Hurtado, who was followed in 1984 by

León Febres Cordero

León Esteban Febres-Cordero Ribadeneyra (9 March 1931 – 15 December 2008), known in the Ecuadorian media as LFC or more simply by his composed surname (Febres-Cordero), was the 35th President of Ecuador, serving a four-year term from 10 Augu ...

from the Social Christian Party.

Rodrigo Borja Cevallos

Rodrigo Borja Cevallos (born 19 June 1935) is an Ecuadorian politician who was President of Ecuador from 10 August 1988 to 10 August 1992. He is also a descendant of the House of Borgia.

Life

Borja was born in Quito, the capital of Ecuador. ...

of the Democratic Left (Izquierda Democrática, or ID) party won the presidency in 1988, running in the runoff election against

Abdalá Bucaram

Abdalá Jaime Bucaram Ortiz ( ; ; born 20 February 1952) is an Ecuadorian politician and lawyer who was President of Ecuador from 10 August 1996, to 6 February 1997. As President, Abdalá Bucaram was nicknamed "El Loco Que Ama" ("The Madman Wh ...

(brother in law of

Jaime Roldos and founder of the Ecuadorian Roldosist Party). His government was committed to improving human rights protection and carried out some reforms, notably an opening of Ecuador to foreign trade. The Borja government concluded an accord leading to the disbanding of the small terrorist group, "

¡Alfaro Vive, Carajo!

¡Alfaro Vive, Carajo! (AVC) ( en, Alfaro Lives, Dammit!), another name for the Fuerzas Armadas Populares Eloy Alfaro ( en, Eloy Alfaro Popular Armed Forces), was a clandestine left-wing group in Ecuador, founded in 1982 and named after popular ...

" ("Alfaro Lives, Dammit!"), named after

Eloy Alfaro

José Eloy Alfaro Delgado (25 June 1842 – 28 January 1912) often referred to as "The Old Warrior," was an Ecuadorian politician who served as the President of Ecuador from 1895 to 1901 and from 1906 to 1911. Eloy Alfaro emerged as the leader ...

. However, continuing economic problems undermined the popularity of the ID, and opposition parties gained control of Congress in 1999.

Ecuador adopted the

United States dollar

The United States dollar ( symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the officia ...

on 13 April 2000 as its national currency and on 11 September, the country eliminated the

Ecuadorian sucre

The Sucre () was the currency of Ecuador between 1884 and 2000. Its ISO code was ECS and it was subdivided into 10 ''decimos'' and 100 '' centavos''. The sucre was named after Latin American political leader Antonio José de Sucre. The currency ...

, in order to stabilize the

country's economy. US Dollar has been the only official currency of Ecuador since the year 2000.

The emergence of the Amerindian population as an active constituency has added to the democratic volatility of the country in recent years. The population has been motivated by government failures to deliver on promises of land reform, lower unemployment and provision of social services, and historical exploitation by the land-holding elite. Their movement, along with the continuing destabilizing efforts by both the elite and leftist movements, has led to a deterioration of the executive office. The populace and the other branches of government give the president very little political capital, as illustrated by the most recent removal of President

Lucio Gutiérrez

Lucio Edwin Gutiérrez Borbúa (born 23 March 1957 in Quito) served as 43rd President of Ecuador from 15 January 2003 to 20 April 2005.

Early life

Lucio Gutierrez, in full Lucio Edwin Gutiérrez Borbua, (born 23 March 1957, Quito, Ecuador), ...

from office by Congress in April 2005. Vice President

Alfredo Palacio

Luis Alfredo Palacio González (born 22 January 1939) is an Ecuadorian cardiologist and former politician who served as President of Ecuador from 20 April 2005 to 15 January 2007. From 15 January 2003 to 20 April 2005, he served as vice presid ...

took his place and remained in office until the presidential

election of 2006, in which

Rafael Correa

Rafael Vicente Correa Delgado (; born 6 April 1963), known as Rafael Correa, is an Ecuadorian politician and economist who served as President of Ecuador from 2007 to 2017. The leader of the PAIS Alliance political movement from its foundation ...

gained the presidency. On 15 January 2007, Rafael Correa was sworn in as the

President of Ecuador

The president of Ecuador ( es, Presidente del Ecuador), officially called the Constitutional President of the Republic of Ecuador ( es, Presidente Constitucional de la República del Ecuador), serves as both the head of state and head of govern ...

. Several left-wing political leaders of Latin America, his future allies, attended the ceremony.

The new socialist constitution, endorsed in

2008 referendum (

2008 Constitution of Ecuador

The Constitution of Ecuador is the supreme law of Ecuador. The current constitution has been in place since 2008. It is the country's 20th constitution.

History

Ecuador has had new constitutions promulgated in 1830, 1835, 1843, 1845, 1851, 1852, ...

), implemented leftist reforms. In December 2008, president Correa declared Ecuador's

national debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt, or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit oc ...

illegitimate, based on the argument that it was

odious debt

In international law, odious debt, also known as illegitimate debt, is a legal theory that says that the national debt incurred by a despotic regime should not be enforceable. Such debts are, thus, considered by this doctrine to be personal debts ...

contracted by corrupt and despotic prior regimes. He announced that the country would default on over $3 billion worth of bonds; he then pledged to fight creditors in

international court

International courts are formed by treaties between nations or under the authority of an international organization such as the United Nations and include ''ad hoc'' tribunals and permanent institutions but exclude any courts arising purely under n ...

s and succeeded in reducing the price of outstanding bonds by more than 60%.

"Avenger against oligarchy" wins in Ecuador

' The Real News

The Real News Network (TRNN) is an independent, nonprofit news organization based in Baltimore, MD that covers both national and international news.

History

TRNN was founded by documentary producer Paul Jay and Mishuk Munier in September 20 ...

, 27 April 2009. He brought Ecuador into the

Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kingdom ...

in June 2009. Correa's administration succeeded in reducing the high levels of poverty and unemployment in Ecuador.

After Correa era

Rafael Correa's three consecutive terms (from 2007 to 2017) were followed by his former Vice President

Lenín Moreno

Lenín Voltaire Moreno Garcés (; born 19 March 1953) is an Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as ...

’s four years as president (2017–21). After being elected in 2017, President

Lenin Moreno

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

's government adopted

economically liberal

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberalism, ...

policies: reduction of

public spending

Government spending or expenditure includes all government consumption, investment, and transfer payments. In national income accounting, the acquisition by governments of goods and services for current use, to directly satisfy the individual o ...

,

trade liberalization

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

, flexibility of the labour code, etc. Ecuador also left the left-wing

Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kingdom ...

(Alba) in August 2018. The Productive Development Act enshrines an austerity policy, and reduces the development and redistribution policies of the previous mandate. In the area of taxes, the authorities aim to "encourage the return of investors" by granting amnesty to fraudsters and proposing measures to reduce

tax rates for large companies. In addition, the government waives the right to tax increases in raw material prices and foreign exchange repatriations. In October 2018, the government of President Lenin Moreno cut diplomatic relations with the

Maduro

Maduro is a surname. Notable people with the name include:

Politicians

* Conrad Maduro (), British Virgin Islands politicians and party leader

* Nicolás Maduro (born 1962), Venezuelan president

* Nicolás Maduro Guerra (born 1990), Venezuelan ...

administration of Venezuela, a close ally of Rafael Correa. The relations with the United States improved significantly during the presidency of Lenin Moreno. In February 2020, his visit to Washington was the first meeting between an Ecuadorian and U.S. president in 17 years. In June 2019, Ecuador had agreed to allow US military planes to operate from an airport on the Galapagos Islands.

2019 state of emergency

A

series of protests began on 3 October 2019 against the end of fuel

subsidies

A subsidy or government incentive is a form of financial aid or support extended to an economic sector (business, or individual) generally with the aim of promoting economic and social policy. Although commonly extended from the government, the ter ...

and

austerity measures

Austerity is a set of political-economic policies that aim to reduce government budget deficits through spending cuts, tax increases, or a combination of both. There are three primary types of austerity measures: higher taxes to fund spend ...

adopted by

President of Ecuador

The president of Ecuador ( es, Presidente del Ecuador), officially called the Constitutional President of the Republic of Ecuador ( es, Presidente Constitucional de la República del Ecuador), serves as both the head of state and head of govern ...

Lenín Moreno

Lenín Voltaire Moreno Garcés (; born 19 March 1953) is an Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as ...

and his administration. On 10 October, protesters overran the capital Quito causing the Government of Ecuador to relocate to

Guayaquil

, motto = Por Guayaquil Independiente en, For Independent Guayaquil

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Ecuador#South America

, pushpin_re ...

, but the government had plans to return to Quito. On 14 October 2019, the government restored fuel subsidies and withdrew an austerity package, meaning the end of nearly two weeks of protests.

Presidency of Guillermo Lasso since 2021

The 11 April 2021

election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

run-off vote ended in a win for conservative former banker,

Guillermo Lasso

Guillermo Alberto Santiago Lasso Mendoza (; born 16 November 1955) is an Ecuadorian businessman, banker, writer and politician who has served as the 47th president of Ecuador since 24 May 2021. He is the country's first centre-right president i ...

, taking 52.4% of the vote compared to 47.6% of left-wing economist

Andrés Arauz

Andrés Arauz Galarza (born 6 February 1985) is an Ecuadorian politician and economist. He was a candidate for President in the 2021 election.

Background

Andrés Arauz started his career as a public servant in 2009 at the Central Bank of Ec ...