Aristotle Metadata Registry, Wikipedia Page on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an

At the age of seventeen or eighteen, Aristotle moved to

At the age of seventeen or eighteen, Aristotle moved to  While Alexander deeply admired Aristotle, near the end of his life, the two men became estranged having diverging opinions over issues, like the optimal administration of city-states, the treatment of conquered populations, such as the Persians, and philosophical questions, like the definition of braveness. A widespread speculation in antiquity suggested that Aristotle played a role in Alexander's death, but the only evidence of this is an unlikely claim made some six years after the death. Following Alexander's death, anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens was rekindled. In 322 BC, Demophilus and

While Alexander deeply admired Aristotle, near the end of his life, the two men became estranged having diverging opinions over issues, like the optimal administration of city-states, the treatment of conquered populations, such as the Persians, and philosophical questions, like the definition of braveness. A widespread speculation in antiquity suggested that Aristotle played a role in Alexander's death, but the only evidence of this is an unlikely claim made some six years after the death. Following Alexander's death, anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens was rekindled. In 322 BC, Demophilus and

Most of Aristotle's work is probably not in its original form, because it was most likely edited by students and later lecturers. The logical works of Aristotle were compiled into a set of six books called the ''

Most of Aristotle's work is probably not in its original form, because it was most likely edited by students and later lecturers. The logical works of Aristotle were compiled into a set of six books called the ''

Like his teacher Plato, Aristotle's philosophy aims at the

Like his teacher Plato, Aristotle's philosophy aims at the

Coming-to-be is a change where the substrate of the thing that has undergone the change has itself changed. In that particular change he introduces the concept of potentiality (''

Coming-to-be is a change where the substrate of the thing that has undergone the change has itself changed. In that particular change he introduces the concept of potentiality (''

Aristotle's

Aristotle's

Aristotle believed the chain of thought that achieves recollection of impressions was connected systematically in relationships such as similarity, contrast, and

Aristotle believed the chain of thought that achieves recollection of impressions was connected systematically in relationships such as similarity, contrast, and

The immediate influence of Aristotle's work was felt as the

The immediate influence of Aristotle's work was felt as the

Ancient Greek philosopher

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics ...

and polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

s, philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

, economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

, politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

, psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, and the arts

The arts or creative arts are a vast range of human practices involving creative expression, storytelling, and cultural participation. The arts encompass diverse and plural modes of thought, deeds, and existence in an extensive range of m ...

. As the founder of the Peripatetic school

The Peripatetic school ( ) was a philosophical school founded in 335 BC by Aristotle in the Lyceum in ancient Athens. It was an informal institution whose members conducted philosophical and scientific inquiries. The school fell into decline afte ...

of philosophy in the Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, he began the wider Aristotelian tradition that followed, which set the groundwork for the development of modern science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

.

Little is known about Aristotle's life. He was born in the city of Stagira in northern Greece

Northern Greece () is used to refer to the northern parts of Greece, and can have various definitions.

Administrative term

The term "Northern Greece" is widely used to refer mainly to the two northern regions of Macedonia and (Western) Thra ...

during the Classical period. His father, Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa (; ) was an Ancient Greek Neopythagorean philosopher from Gerasa, in the Roman province of Syria (now Jerash, Jordan). Like many Pythagoreans, Nicomachus wrote about the mystical properties of numbers, best known for his ...

, died when Aristotle was a child, and he was brought up by a guardian. At around eighteen years old, he joined Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

's Academy

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

in Athens and remained there until the age of thirty seven (). Shortly after Plato died, Aristotle left Athens and, at the request of Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon (; 382 BC – October 336 BC) was the king (''basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

, tutored his son Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

beginning in 343 BC. He established a library in the Lyceum, which helped him to produce many of his hundreds of books on papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, ''Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'' or ''papyruses'') can a ...

scrolls

A scroll (from the Old French ''escroe'' or ''escroue''), also known as a roll, is a roll of papyrus, parchment, or paper containing writing.

Structure

A scroll is usually partitioned into pages, which are sometimes separate sheets of papyru ...

.

Though Aristotle wrote many treatises and dialogues for publication, only around a third of his original output has survived, none of it intended for publication. Aristotle provided a complex synthesis of the various philosophies existing prior to him. His teachings and methods of inquiry have had a significant impact across the world, and remain a subject of contemporary philosophical discussion.

Aristotle's views profoundly shaped medieval scholarship. The influence of his physical science extended from late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

and the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

into the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, and was not replaced systematically until the Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empirici ...

and theories such as classical mechanics

Classical mechanics is a Theoretical physics, physical theory describing the motion of objects such as projectiles, parts of Machine (mechanical), machinery, spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. The development of classical mechanics inv ...

were developed. He influenced Judeo-Islamic philosophies during the Middle Ages, as well as Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology – the systematic study of the divine and religion – of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. It concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Ch ...

, especially the Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

of the Early Church

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the historical era of the Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Christianity spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and bey ...

and the scholastic tradition of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

.

Aristotle was revered among medieval Muslim scholars as "The First Teacher", and among medieval Christians like Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

as simply "The Philosopher", while the poet Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

called him "the master of those who know". He has been referred to as the first scientist

A scientist is a person who Scientific method, researches to advance knowledge in an Branches of science, area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engag ...

. His works contain the earliest known systematic study of logic, and were studied by medieval scholars such as Peter Abelard

Peter Abelard (12 February 1079 – 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, teacher, musician, composer, and poet. This source has a detailed description of his philosophical work.

In philos ...

and Jean Buridan

Jean Buridan (; ; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14thcentury French scholastic philosopher.

Buridan taught in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career and focused in particular on logic and ...

. His influence on logic continued well into the 19th century. In addition, his ethics, although always influential, has gained renewed interest with the modern advent of virtue ethics

Virtue ethics (also aretaic ethics, from Greek []) is a philosophical approach that treats virtue and moral character, character as the primary subjects of ethics, in contrast to other ethical systems that put consequences of voluntary acts, pri ...

.

Life

In general, the details of Aristotle's life are not well-established. The biographies written in ancient times are often speculative and historians only agree on a few salient points. Aristotle was born in 384 BC in Stagira,Chalcidice

Chalkidiki (; , alternatively Halkidiki), also known as Chalcidice, is a peninsula and regional units of Greece, regional unit of Greece, part of the region of Central Macedonia, in the Geographic regions of Greece, geographic region of Macedon ...

, about 55 km (34 miles) east of modern-day Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

. He was the son of Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa (; ) was an Ancient Greek Neopythagorean philosopher from Gerasa, in the Roman province of Syria (now Jerash, Jordan). Like many Pythagoreans, Nicomachus wrote about the mystical properties of numbers, best known for his ...

, the personal physician of King Amyntas of Macedon, and Phaestis, a woman with origins from Chalcis

Chalcis (; Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: , ), also called Chalkida or Halkida (Modern Greek: , ), is the chief city of the island of Euboea or Evia in Greece, situated on the Euripus Strait at its narrowest point. The name is preserved from ...

, Euboea

Euboea ( ; , ), also known by its modern spelling Evia ( ; , ), is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete, and the sixth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by ...

. Nicomachus was said to have belonged to the medical guild of Asclepiadae Asclepiad (Ancient Greek, Greek: Ἀσκληπιάδης, pl.: Ἀσκληπιάδαι) was a title borne by many Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek medical doctors, notably Hippocrates of Kos. It is not clear whether the Asclepiads were originally a bio ...

and was likely responsible for Aristotle's early interest in biology and medicine. Ancient tradition held that Aristotle's family descended from the legendary physician Asclepius

Asclepius (; ''Asklēpiós'' ; ) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Religion in ancient Greece, Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis (lover of Apollo), Coronis, or Arsinoe (Greek myth), Ars ...

and his son Machaon. Both of Aristotle's parents died when he was still at a young age and Proxenus of Atarneus Proxenus of Atarneus () is most famous for being Aristotle's guardian after the death of his parents. Proxenus educated Aristotle for a couple of years before sending him to Athens to Plato's Academy. He lived in Atarneus, a city in Asia Minor.

...

became his guardian. Although little information about Aristotle's childhood has survived, he probably spent some time in the Macedonian

Macedonian most often refers to someone or something from or related to Macedonia.

Macedonian(s) may refer to:

People Modern

* Macedonians (ethnic group), a nation and a South Slavic ethnic group primarily associated with North Macedonia

* Mac ...

capital, making his first connections with the Macedonian monarchy.

At the age of seventeen or eighteen, Aristotle moved to

At the age of seventeen or eighteen, Aristotle moved to Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

to continue his education at Plato's Academy

The Academy (), variously known as Plato's Academy, or the Platonic Academy, was founded in Athens by Plato ''circa'' 387 BC. The academy is regarded as the first institution of higher education in the west, where subjects as diverse as biolog ...

. He became distinguished as a researcher and lecturer, earning for himself the nickname "mind of the school" by his tutor Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

. In Athens, he probably experienced the Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries () were initiations held every year for the Cult (religious practice), cult of Demeter and Persephone based at the Panhellenic Sanctuary of Eleusis in ancient Greece. They are considered the "most famous of the secret rel ...

as he wrote when describing the sights one viewed at the Mysteries, "to experience is to learn" (). Aristotle remained in Athens for nearly twenty years before leaving in 348/47 BC after Plato's death. The traditional story about his departure records that he was disappointed with the academy's direction after control passed to Plato's nephew Speusippus

Speusippus (; ; c. 408 – 339/8 BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek philosopher. Speusippus was Plato's nephew by his sister Potone. After Plato's death, c. 348 BC, Speusippus inherited the Platonic Academy, Academy, near age 60, and remai ...

, although it is possible that the anti-Macedonian sentiments in Athens could have also influenced his decision. Aristotle left with Xenocrates

Xenocrates (; ; c. 396/5314/3 BC) of Chalcedon was a Greek philosopher, mathematician, and leader ( scholarch) of the Platonic Academy from 339/8 to 314/3 BC. His teachings followed those of Plato, which he attempted to define more closely, of ...

to Assos

Assos (; , ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city near today's Behramkale () or Behram for short, which most people still call by its ancient name of Assos. It is located on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast in the Ayvacık, Çanakkale, Ayvac ...

in Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, where he was invited by his former fellow student Hermias of Atarneus

Hermias of Atarneus (; ; died 341/0 BC) was a Greek tyrant of Atarneus, and Aristotle's father-in-law.

The first mention of Hermias is as a slave to Eubulus, a Bithynian banker who ruled Atarneus. Hermias eventually won his freedom and inher ...

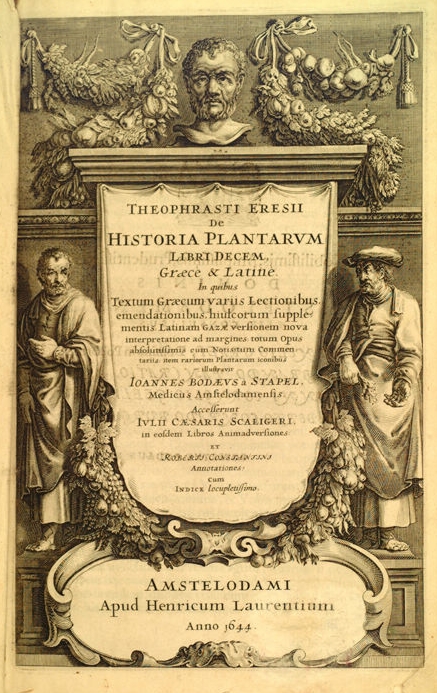

; he stayed there for a few years and left around the time of Hermias' death. While at Assos, Aristotle and his colleague Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

did extensive research in botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

and marine biology

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms that inhabit the sea. Given that in biology many scientific classification, phyla, family (biology), families and genera have some species that live in the sea and ...

, which they later continued at the near-by island of Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

. During this time, Aristotle married Pythias

Pythias (; ), also known as Pythias the Elder, was the adopted daughter of Hermias, ruler of the cities Assos and Atarneus on the Anatolian coast opposite the island of Lesbos. She was also Aristotle's first wife. Hermias was an enemy of Per ...

, Hermias's adoptive daughter and niece, and had a daughter whom they also named Pythias.

In 343/42 BC, Aristotle was invited to Pella

Pella () is an ancient city located in Central Macedonia, Greece. It served as the capital of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. Currently, it is located 1 km outside the modern town of Pella ...

by Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon (; 382 BC – October 336 BC) was the king (''basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

to become the tutor to his thirteen-year-old son Alexander

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here ar ...

; a choice perhaps influenced by the relationship of Aristotle's family with the Macedonian dynasty. Aristotle taught Alexander at the private school of Mieza, in the gardens of the Nymph

A nymph (; ; sometimes spelled nymphe) is a minor female nature deity in ancient Greek folklore. Distinct from other Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature; they are typically tied to a specific place, land ...

s, the royal estate near Pella. Alexander's education probably included a number of subjects, such as ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

and politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

, as well as standard literary texts, like Euripides

Euripides () was a Greek tragedy, tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars attributed ninety-five plays to ...

and Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

. It is likely that during Aristotle's time in the Macedonian court, other prominent nobles, like Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

and Cassander

Cassander (; ; 355 BC – 297 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia from 305 BC until 297 BC, and '' de facto'' ruler of southern Greece from 317 BC until his death.

A son of Antipater and a contemporary of Alexander the ...

, would have occasionally attended his lectures. Aristotle encouraged Alexander toward eastern conquest, and his own attitude towards Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

was strongly ethnocentric

Ethnocentrism in social science and anthropology—as well as in colloquial English discourse—means to apply one's own culture or ethnicity as a frame of reference to judge other cultures, practices, behaviors, beliefs, and people, instead of ...

. In one famous example, he counsels Alexander to be "a leader to the Greeks and a despot to the barbarians". Alexander's education under the guardianship of Aristotle likely lasted for only a few years, as at around the age of sixteen he returned to Pella and was appointed regent of Macedon by his father Philip. During this time, Aristotle gifted Alexander an annotated copy of the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'', which is said to have become one of Alexander's most prized possessions. Scholars speculate that two of Aristotle's now lost works, ''On kingship'' and ''On behalf of the Colonies'', were composed by the philosopher for the young prince. Aristotle returned to Athens for the second and final time a year after Philip II's assassination in 336 BC.

As a metic

In ancient Greece, a metic (Ancient Greek: , : from , , indicating change, and , 'dwelling') was a resident of Athens and some other cities who was a citizen of another polis. They held a status broadly analogous to modern permanent residency, b ...

, Aristotle could not own property in Athens and thus rented a building known as the Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

(named after the sacred grove of Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

''Lykeios''), in which he established his own school. The building included a gymnasium and a colonnade

In classical architecture, a colonnade is a long sequence of columns joined by their entablature, often free-standing, or part of a building. Paired or multiple pairs of columns are normally employed in a colonnade which can be straight or curv ...

(), from which the school acquired the name ''Peripatetic

Peripatetic may refer to:

*Peripatetic school, a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece

*Peripatetic axiom, in philosophy

*Peripatetic minority, a mobile population moving among settled populations offering a craft or trade.

*Peripatetic Jats

T ...

''. Aristotle conducted courses and research at the school for the next twelve years. He often lectured small groups of distinguished students and, along with some of them, such as Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

, Eudemus, and Aristoxenus

Aristoxenus of Tarentum (; born 375, fl. 335 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek Peripatetic school, Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have been lost, but one musi ...

, Aristotle built a large library which included manuscripts, maps, and museum objects. While in Athens, his wife Pythias died and Aristotle became involved with Herpyllis

Herpyllis of Stagira () was Aristotle's companion and lover after his wife, Pythias, died. It is unclear whether she was a free woman (as it appears in the surviving Greek version of Aristotle's will) or a servant (as in the Arabic version).

T ...

of Stagira. They had a son whom Aristotle named after his father, Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa (; ) was an Ancient Greek Neopythagorean philosopher from Gerasa, in the Roman province of Syria (now Jerash, Jordan). Like many Pythagoreans, Nicomachus wrote about the mystical properties of numbers, best known for his ...

. This period in Athens, between 335 and 323 BC, is when Aristotle is believed to have composed many of his philosophical works. He wrote many dialogues, of which only fragments have survived. Those works that have survived are in treatise

A treatise is a Formality, formal and systematic written discourse on some subject concerned with investigating or exposing the main principles of the subject and its conclusions."mwod:treatise, Treatise." Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Acc ...

form and were not, for the most part, intended for widespread publication; they are generally thought to be lecture aids for his students. His most important treatises include ''Physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

'', ''Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

'', ''Nicomachean Ethics

The ''Nicomachean Ethics'' (; , ) is Aristotle's best-known work on ethics: the science of the good for human life, that which is the goal or end at which all our actions aim. () It consists of ten sections, referred to as books, and is closely ...

'', ''Politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

'', ''On the Soul

''On the Soul'' ( Greek: , ''Peri Psychēs''; Latin: ) is a major treatise written by Aristotle . His discussion centres on the kinds of souls possessed by different kinds of living things, distinguished by their different operations. Thus pla ...

'' and ''Poetics

Poetics is the study or theory of poetry, specifically the study or theory of device, structure, form, type, and effect with regards to poetry, though usage of the term can also refer to literature broadly. Poetics is distinguished from hermeneu ...

''. Aristotle studied and made significant contributions to "logic, metaphysics, mathematics, physics, biology, botany, ethics, politics, agriculture, medicine, dance, and theatre."

While Alexander deeply admired Aristotle, near the end of his life, the two men became estranged having diverging opinions over issues, like the optimal administration of city-states, the treatment of conquered populations, such as the Persians, and philosophical questions, like the definition of braveness. A widespread speculation in antiquity suggested that Aristotle played a role in Alexander's death, but the only evidence of this is an unlikely claim made some six years after the death. Following Alexander's death, anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens was rekindled. In 322 BC, Demophilus and

While Alexander deeply admired Aristotle, near the end of his life, the two men became estranged having diverging opinions over issues, like the optimal administration of city-states, the treatment of conquered populations, such as the Persians, and philosophical questions, like the definition of braveness. A widespread speculation in antiquity suggested that Aristotle played a role in Alexander's death, but the only evidence of this is an unlikely claim made some six years after the death. Following Alexander's death, anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens was rekindled. In 322 BC, Demophilus and Eurymedon the Hierophant

Eurymedon the Hierophant (; ) was a representative of the priestly clan overseeing the Eleusinian Mysteries. Together with Demophilus he reportedly brought a charge of impiety against Aristotle after Alexander the Great

Alexander III of M ...

reportedly denounced Aristotle for impiety, prompting him to flee to his mother's family estate in Chalcis

Chalcis (; Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: , ), also called Chalkida or Halkida (Modern Greek: , ), is the chief city of the island of Euboea or Evia in Greece, situated on the Euripus Strait at its narrowest point. The name is preserved from ...

, Euboea, at which occasion he was said to have stated "I will not allow the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy" – a reference to Athens's trial and execution of Socrates. He died in Chalcis, Euboea of natural causes later that same year, having named his student Antipater

Antipater (; ; 400 BC319 BC) was a Macedonian general, regent and statesman under the successive kingships of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. In the wake of the collapse of the Argead house, his son Cassander ...

as his chief executor

An executor is someone who is responsible for executing, or following through on, an assigned task or duty.

The feminine form, executrix, is sometimes used.

Executor of will

An executor is a legal term referring to a person named by the maker o ...

and leaving a will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

in which he asked to be buried next to his wife. Aristotle left his works to Theophrastus, his successor as the head of the Lyceum, who in turn passed them down to Neleus of Scepsis

Neleus of Scepsis (; ), was the son of Coriscus of Scepsis. He was a disciple of Aristotle and Theophrastus, the latter of whom bequeathed to him his library, and appointed him one of his executors. Neleus supposedly took the writings of Aristotle ...

in Asia Minor. There, the papers remained hidden for protection until they were purchased by the collector Apellicon. In the meantime, many copies of Aristotle's major works had already begun to circulate and be used in the Lyceum of Athens, Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, and later in Rome.

Theoretical philosophy

Logic

With the '' Prior Analytics'', Aristotle is credited with the earliest systematic study of logic, and his conception of it was the dominant form of Western logic until 19th-century advances inmathematical logic

Mathematical logic is the study of Logic#Formal logic, formal logic within mathematics. Major subareas include model theory, proof theory, set theory, and recursion theory (also known as computability theory). Research in mathematical logic com ...

. Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, et ...

stated in the ''Critique of Pure Reason

The ''Critique of Pure Reason'' (; 1781; second edition 1787) is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was foll ...

'' that with Aristotle, logic reached its completion.

''Organon''

Most of Aristotle's work is probably not in its original form, because it was most likely edited by students and later lecturers. The logical works of Aristotle were compiled into a set of six books called the ''

Most of Aristotle's work is probably not in its original form, because it was most likely edited by students and later lecturers. The logical works of Aristotle were compiled into a set of six books called the ''Organon

The ''Organon'' (, meaning "instrument, tool, organ") is the standard collection of Aristotle's six works on logical analysis and dialectic. The name ''Organon'' was given by Aristotle's followers, the Peripatetics, who maintained against the ...

'' around 40 BC by Andronicus of Rhodes

Andronikos of Rhodes (; ; ) was a Greek philosopher from Rhodes who was also the scholarch (head) of the Peripatetic school. He is most famous for publishing a new edition of the works of Aristotle that forms the basis of the texts that survive t ...

or others among his followers. The books are:

# ''Categories

Category, plural categories, may refer to:

General uses

*Classification, the general act of allocating things to classes/categories Philosophy

*Category of being

* ''Categories'' (Aristotle)

*Category (Kant)

*Categories (Peirce)

*Category (Vais ...

''

# ''On Interpretation

''On Interpretation'' (Ancient Greek, Greek: , ) is the second text from Aristotle's ''Organon'' and is among the earliest surviving philosophical works in the Western philosophy, Western tradition to deal with the relationship between language an ...

''

# '' Prior Analytics''

# ''Posterior Analytics

The ''Posterior Analytics'' (; ) is a text from Aristotle's '' Organon'' that deals with demonstration, definition, and scientific knowledge. The demonstration is distinguished as ''a syllogism productive of scientific knowledge'', while the de ...

''

# '' Topics''

# ''On Sophistical Refutations

''Sophistical Refutations'' (; ) is a text in Aristotle's ''Organon'' in which he identified thirteen Fallacy, fallacies.Sometimes listed as twelve. According to Aristotle, this is the first work to treat the subject of deductive reasoning in anc ...

''

The order of the books (or the teachings from which they are composed) is not certain, but this list was derived from analysis of Aristotle's writings. It goes from the basics, the analysis of simple terms in the ''Categories,'' the analysis of propositions and their elementary relations in ''On Interpretation'', to the study of more complex forms, namely, syllogisms and demonstration (in the ''Analytics'') and dialectics (in the ''Topics'' and ''Sophistical Refutations''). The first three treatises form the core of the logical theory ''stricto sensu'': the grammar of the language of logic and the correct rules of reasoning. The ''Rhetoric'' is not conventionally included, but it states that it relies on the ''Topics''.

Syllogism

What is today called ''Aristotelian logic'' with its types of syllogism (methods of logical argument), Aristotle himself would have labelled "analytics". The term "logic" he reserved to mean ''dialectics''.Demonstration

Aristotle's ''Posterior Analytics'' contains his account of demonstration, or demonstrative knowledge, what would today be considered the study ofepistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

rather than logic, but which for Aristotle is deeply connected with his account of syllogism. For Aristotle, knowledge is that which is necessarily the case, along with the study of causes.

Metaphysics

The word "metaphysics" comes from the title of a collection of works by Aristotle bearing that title. However, Aristotle himself did not use that term himself, which is due to a later compiler, but instead called it "first philosophy" ortheology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

. He distinguished this as "the study of being qua being" which, as opposed to other studies of being, such as mathematics and natural science, studies that which is eternal, unchanging, and immaterial. He wrote in his ''Metaphysics'' (1026a16):

Substance

Aristotle examines the concepts ofsubstance

Substance may refer to:

* Matter, anything that has mass and takes up space

Chemistry

* Chemical substance, a material with a definite chemical composition

* Drug, a chemical agent affecting an organism

Arts, entertainment, and media Music

* ' ...

(''ousia'') and essence

Essence () has various meanings and uses for different thinkers and in different contexts. It is used in philosophy and theology as a designation for the property (philosophy), property or set of properties or attributes that make an entity the ...

(''to ti ên einai'', "the what it was to be") in his ''Metaphysics'' (Book VII), and he concludes that a particular substance is a combination of both matter and form, a philosophical theory called hylomorphism

Hylomorphism is a philosophical doctrine developed by the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, which conceives every physical entity or being ('' ousia'') as a compound of matter (potency) and immaterial form (act), with the generic form as imm ...

. In Book VIII, he distinguishes the matter of the substance as the substratum

Substrata, plural of substratum, may refer to:

*Earth's substrata, the geologic layering of the Earth

*''Hypokeimenon'', sometimes translated as ''substratum'', a concept in metaphysics

*Substrata (album), a 1997 ambient music album by Biosphere

* ...

, or the stuff of which it is composed. For example, the matter of a house is the bricks, stones, timbers, etc., or whatever constitutes the ''potential'' house, while the form of the substance is the ''actual'' house, namely 'covering for bodies and chattels' or any other differentia

In scholastic logic, ''differentia'' (also called ''differentia specifica'') is one of the predicables; it is that part of a definition which is predicable in a given ''genus'' only of the '' definiendum''; or the corresponding " metaphysical pa ...

that let us define something as a house. The formula that gives the components is the account of the matter, and the formula that gives the differentia is the account of the form.

= Moderate realism

=universal

Universal is the adjective for universe.

Universal may also refer to:

Companies

* NBCUniversal, a media and entertainment company that is a subsidiary of Comcast

** Universal Animation Studios, an American Animation studio, and a subsidiary of N ...

. Aristotle's ontology

Ontology is the philosophical study of existence, being. It is traditionally understood as the subdiscipline of metaphysics focused on the most general features of reality. As one of the most fundamental concepts, being encompasses all of realit ...

has the universal () exist in a lesser sense than particular

In metaphysics, particulars or individuals are usually contrasted with ''universals''. Universals concern features that can be exemplified by various different particulars. Particulars are often seen as concrete, spatiotemporal entities as opposed ...

s (), things in the world, whereas for Plato the universal

Universal is the adjective for universe.

Universal may also refer to:

Companies

* NBCUniversal, a media and entertainment company that is a subsidiary of Comcast

** Universal Animation Studios, an American Animation studio, and a subsidiary of N ...

is a realer, separately existing form which particular things merely imitate. For Aristotle, universals still exist, but are only encountered when "instantiated" in a particular substance.

In addition, Aristotle disagreed with Plato about the location of universals. Where Plato spoke of the forms as existing separately from the things that participate in them, Aristotle maintained that universals are multiply located. So, according to Aristotle, the form of apple exists within each apple, rather than in the world of the forms.

= Potentiality and actuality

= Concerning the nature of change ('' kinesis'') and its causes, as he outlines in his ''Physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

'' and ''On Generation and Corruption

''On Generation and Corruption'' (; ), also known as ''On Coming to Be and Passing Away'' is a treatise by Aristotle. Like many of his texts, it is both scientific, part of Aristotle's biology, and philosophic. The philosophy is essentially emp ...

(''319b–320a), he distinguishes coming-to-be (''genesis'', also translated as 'generation') from:

# growth and diminution, which is change in quantity;

# locomotion, which is change in space; and

# alteration, which is change in quality.

Coming-to-be is a change where the substrate of the thing that has undergone the change has itself changed. In that particular change he introduces the concept of potentiality (''

Coming-to-be is a change where the substrate of the thing that has undergone the change has itself changed. In that particular change he introduces the concept of potentiality (''dynamis

Dunamis (Ancient Greek: δύναμις) is a Greek philosophical concept meaning "power", "potential" or "ability", and is central to the Aristotelian idea of ''potentiality and actuality''.

Dunamis or Dynamis may also refer to:

* Dynamis (Bosp ...

'') and actuality (''entelecheia

In philosophy, potentiality and actuality are a pair of closely connected principles which Aristotle used to analyze Motion (physics), motion, Four causes, causality, Aristotelian ethics, ethics, and physiology in his ''Aristotelian physics, Ph ...

'') in association with the matter and the form. Referring to potentiality, this is what a thing is capable of doing or being acted upon if the conditions are right and it is not prevented by something else. For example, the seed of a plant in the soil is potentially (''dynamei'') a plant, and if it is not prevented by something, it will become a plant. Potentially, beings can either 'act' (''poiein'') or 'be acted upon' (''paschein''), which can be either innate or learned. For example, the eyes possess the potentiality of sight (innate – being acted upon), while the capability of playing the flute can be possessed by learning (exercise – acting). Actuality is the fulfilment of the end of the potentiality. Because the end (''telos'') is the principle of every change, and potentiality exists for the sake of the end, actuality, accordingly, is the end. Referring then to the previous example, it can be said that an actuality is when a plant does one of the activities that plants do.

In summary, the matter used to make a house has potentiality to be a house and both the activity of building and the form of the final house are actualities, which is also a final cause

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: material cause, the formal cause, the efficient cause, ...

or end. Then Aristotle proceeds and concludes that the actuality is prior to potentiality in formula, in time and in substantiality. With this definition of the particular substance (i.e., matter and form), Aristotle tries to solve the problem of the unity of the beings, for example, "what is it that makes a man one"? Since, according to Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

there are two Ideas: animal and biped, how then is man a unity? However, according to Aristotle, the potential being (matter) and the actual one (form) are one and the same.

Natural philosophy

Aristotle's "natural philosophy" spans a wide range of natural phenomena including those now covered by physics, biology and other natural sciences. In Aristotle's terminology, "natural philosophy" is a branch of philosophy examining the phenomena of the natural world, and includes fields that would be regarded today as physics, biology and other natural sciences. Aristotle's work encompassed virtually all facets of intellectual inquiry. Aristotle makes philosophy in the broad sense coextensive with reasoning, which he also would describe as "science". However, his use of the term ''science'' carries a different meaning than that covered by the term "scientific method". For Aristotle, "all science (''dianoia'') is either practical, poetical or theoretical" (''Metaphysics'' 1025b25). His practical science includes ethics and politics; his poetical science means the study of fine arts including poetry; his theoretical science covers physics, mathematics and metaphysics.Physics

Five elements

In his ''On Generation and Corruption

''On Generation and Corruption'' (; ), also known as ''On Coming to Be and Passing Away'' is a treatise by Aristotle. Like many of his texts, it is both scientific, part of Aristotle's biology, and philosophic. The philosophy is essentially emp ...

'', Aristotle related each of the four elements proposed earlier by Empedocles

Empedocles (; ; , 444–443 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is known best for originating the Cosmogony, cosmogonic theory of the four cla ...

, earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

, water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

, air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

, and fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a fuel in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

Flames, the most visible portion of the fire, are produced in the combustion re ...

, to two of the four sensible qualities, hot, cold, wet, and dry. In the Empedoclean scheme, all matter was made of the four elements, in differing proportions. Aristotle's scheme added the heavenly aether, the divine substance of the heavenly spheres

''Heavenly Spheres'' (L'Harmonie des Sphères) is an a cappella choral album by the Studio de musique ancienne de Montréal under the direction of Christopher Jackson (keyboardist), Christopher Jackson. Recorded in 1998, it features songs from ...

, stars and planets.

Motion

Aristotle describes two kinds of motion: "violent" or "unnatural motion", such as that of a thrown stone, in the ''Physics'' (254b10), and "natural motion", such as of a falling object, in ''On the Heavens'' (300a20). In violent motion, as soon as the agent stops causing it, the motion stops also: in other words, the natural state of an object is to be at rest, since Aristotle does not addressfriction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. Types of friction include dry, fluid, lubricated, skin, and internal -- an incomplete list. The study of t ...

. With this understanding, it can be observed that, as Aristotle stated, heavy objects (on the ground, say) require more force to make them move; and objects pushed with greater force move faster. This would imply the equation

:: ,

incorrect in modern physics.

Natural motion depends on the element concerned: the aether naturally moves in a circle around the heavens, while the 4 Empedoclean elements move vertically up (like fire, as is observed) or down (like earth) towards their natural resting places.

In the ''Physics'' (215a25), Aristotle effectively states a quantitative law, that the speed, v, of a falling body is proportional (say, with constant c) to its weight, W, and inversely proportional to the density, ρ, of the fluid in which it is falling:;

::

Aristotle implies that in a vacuum

A vacuum (: vacuums or vacua) is space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective (neuter ) meaning "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressur ...

the speed of fall would become infinite, and concludes from this apparent absurdity that a vacuum is not possible. Opinions have varied on whether Aristotle intended to state quantitative laws. Henri Carteron held the "extreme view" that Aristotle's concept of force was basically qualitative, but other authors reject this.

Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

corrected Aristotle's theory that bodies move towards their natural resting places; metal boats can float if they displace enough water; floating depends in Archimedes' scheme on the mass and volume of the object, not, as Aristotle thought, its elementary composition.

Aristotle's writings on motion remained influential until the early modern

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

period. John Philoponus

John Philoponus ( Greek: ; , ''Ioánnis o Philóponos''; c. 490 – c. 570), also known as John the Grammarian or John of Alexandria, was a Coptic Miaphysite philologist, Aristotelian commentator and Christian theologian from Alexandria, Byza ...

(in late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

) and Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

(in the early modern period) are said to have shown by experiment that Aristotle's claim that a heavier object falls faster than a lighter object is incorrect. A contrary opinion is given by Carlo Rovelli

Carlo Rovelli (born 3 May 1956) is an Italian theoretical physicist and writer who has worked in Italy, the United States, France, and Canada. He is currently Emeritus Professor at the Centre de Physique Theorique of Marseille in France, a Disti ...

, who argues that Aristotle's physics of motion is correct within its domain of validity, that of objects in the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

's gravitational field immersed in a fluid such as air. In this system, heavy bodies in steady fall indeed travel faster than light ones (whether friction is ignored, or not), and they do fall more slowly in a denser medium.

Newton's "forced" motion corresponds to Aristotle's "violent" motion with its external agent, but Aristotle's assumption that the agent's effect stops immediately it stops acting (e.g., the ball leaves the thrower's hand) has awkward consequences: he has to suppose that surrounding fluid helps to push the ball along to make it continue to rise even though the hand is no longer acting on it, resulting in the Medieval theory of impetus

The theory of impetus, developed in the Middle Ages, attempts to explain the forced motion of a body, what it is, and how it comes about or ceases. It is important to note that in ancient and medieval times, motion was always considered absolute, ...

.

Four causes

Aristotle distinguished between four different "causes"(, ''aitia'') or explanations for why an object exists or changes: * Thematerial cause

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: material cause, the formal cause, the efficient cause, a ...

describes the material out of which something is composed. Thus the material cause of a wooden table is the wood it is made of.

* The formal cause

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: material cause, the formal cause, the efficient cause, ...

is its form, i.e., the arrangement of that matter, the design of the table independent of the specific material it is made of.

* The efficient cause

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: material cause, the formal cause, the efficient cause, ...

is "the primary source", the modern definition of "cause" as either the agent or agency of particular events or states of affairs. In the case of two dominoes, when the first is knocked over it ''causes'' the second to fall. In the case of an animal, this agency is a combination of how it develops from the egg, and how its body functions.

* The final cause

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: material cause, the formal cause, the efficient cause, ...

(''telos'') is its purpose, the reason why it exists or is done, or function that something is supposed to serve. In the case of living things, it implies adaptation

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the p ...

to a particular way of life.

Optics

Aristotle was aware of Pythagorean optics. He used optics in his ''Meteorology'', treating it as a science. He viewed optics as stating the laws of sight, thus combining what is now treated as physics and biology. The process of seeing involved the movement of a visible form from the thing seen through the air (or other medium) to the eye, where the form comes to rest. Aristotle does not analyse the nature of this movement; he does not anticipategeometrical optics

Geometrical optics, or ray optics, is a model of optics that describes light Wave propagation, propagation in terms of ''ray (optics), rays''. The ray in geometrical optics is an abstract object, abstraction useful for approximating the paths along ...

.

Chance and spontaneity

According to Aristotle, spontaneity and chance are causes of some things, distinguishable from other types of cause such as simple necessity. Chance as an incidental cause lies in the realm of accidental things, "from what is spontaneous". There is also more a specific kind of chance, which Aristotle names "luck", that only applies to people's moral choices.Astronomy

Inastronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, Aristotle refuted Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

's claim that the Milky Way

The Milky Way or Milky Way Galaxy is the galaxy that includes the Solar System, with the name describing the #Appearance, galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars in other arms of the galax ...

was made up of "those stars which are shaded by the earth from the sun's rays," pointing out partly correctly that if "the size of the sun is greater than that of the earth and the distance of the stars from the earth many times greater than that of the sun, then... the sun shines on all the stars and the earth screens none of them." He also wrote descriptions of comets, including the Great Comet of 371 BC

The Great Comet of 372–371 BC (sometimes Aristotle's Comet) was a comet that was observed by Aristotle, Ephorus, and Callisthenes. Ephorus reported that it split into two pieces, a larger fragment that is thought to have possibly returned in 1 ...

.

Geology and natural sciences

Aristotle was one of the first people to record anygeological

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth s ...

observations. He stated that geological change was too slow to be observed in one person's lifetime.

The geologist Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

noted that Aristotle described such change, including "lakes that had dried up" and "deserts that had become watered by rivers", giving as examples the growth of the Nile delta

The Nile Delta (, or simply , ) is the River delta, delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the eas ...

since the time of Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

, and "the upheaving of one of the Aeolian islands

The Aeolian Islands ( ; ; ), sometimes referred to as the Lipari Islands or Lipari group ( , ) after their largest island, are a volcanic archipelago in the Tyrrhenian Sea north of Sicily, said to be named after Aeolus, the mythical ruler of ...

, previous to a volcanic eruption

A volcanic eruption occurs when material is expelled from a volcanic vent or fissure. Several types of volcanic eruptions have been distinguished by volcanologists. These are often named after famous volcanoes where that type of behavior h ...

."'

''Meteorologica'' lends its name to the modern study of meteorology, but its modern usage diverges from the content of Aristotle's ancient treatise on meteors

A meteor, known colloquially as a shooting star, is a glowing streak of a small body (usually meteoroid) going through Earth's atmosphere, after being heated to incandescence by collisions with air molecules in the upper atmosphere,

creating a ...

. The ancient Greeks did use the term for a range of atmospheric phenomena, but also for earthquakes

An earthquakealso called a quake, tremor, or tembloris the shaking of the Earth's surface resulting from a sudden release of energy in the lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from those so weak they c ...

and volcanic eruptions. Aristotle proposed that the cause of earthquakes was a gas or vapor (''anathymiaseis'') that was trapped inside the earth and trying to escape, following other Greek authors Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; , ''Anaxagóras'', 'lord of the assembly'; ) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, Anaxagoras came to Athens. In later life he was charged ...

, Empedocles

Empedocles (; ; , 444–443 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is known best for originating the Cosmogony, cosmogonic theory of the four cla ...

and Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

.

Aristotle also made many observations about the hydrologic cycle. For example, he made some of the earliest observations about desalination: he observed early – and correctly – that when seawater is heated, freshwater evaporates and that the oceans are then replenished by the cycle of rainfall and river runoff ("I have proved by experiment that salt water evaporated forms fresh and the vapor does not when it condenses condense into sea water again.")

Biology

Empirical research

Aristotle was the first person to study biology systematically, and biology forms a large part of his writings. He spent two years observing and describing the zoology ofLesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

and the surrounding seas, including in particular the Pyrrha lagoon in the centre of Lesbos. His data in ''History of Animals

''History of Animals'' (, ''Ton peri ta zoia historion'', "Inquiries on Animals"; , "History of Animals") is one of the major texts on biology by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. It was written in sometime between the mid-fourth centur ...

'', ''Generation of Animals

The ''Generation of Animals'' (or ''On the Generation of Animals''; Greek: ''Περὶ ζῴων γενέσεως'' (''Peri Zoion Geneseos''); Latin: ''De Generatione Animalium'') is one of the biological works of the Corpus Aristotelicum, the col ...

'', ''Movement of Animals

''Movement of Animals'' (or ''On the Motion of Animals''; Greek Περὶ ζῴων κινήσεως; Latin ''De Motu Animalium'') is one of Aristotle's major texts on biology. It sets out the general principles of animal locomotion

In etho ...

'', and ''Parts of Animals

''Parts of Animals'' (or ''On the Parts of Animals''; Greek Περὶ ζῴων μορίων; Latin ''De Partibus Animalium'') is one of Aristotle's major texts on biology. It was written around 350 BC. The whole work is roughly a study in animal ...

'' are from his own observations, statements by knowledgeable people such as beekeepers and fishermen, and accounts by travellers. His apparent emphasis on animals rather than plants is a historical accident: his works on botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

have been lost, but two books on plants by his pupil Theophrastus have survived.

Aristotle reports on sea-life from observation on Lesbos and the catches of fishermen. He describes the catfish

Catfish (or catfishes; order (biology), order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Catfish are common name, named for their prominent barbel (anatomy), barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, though not ...

, electric ray

The electric rays are a group of rays, flattened cartilaginous fish with enlarged pectoral fins, composing the order Torpediniformes . They are known for being capable of producing an electric discharge, ranging from 8 to 220 volts, depending ...

, and frogfish

Frogfishes are any member of the anglerfish family Antennariidae, of the order Lophiiformes. Antennariids are known as anglerfish in Australia, where the term "frogfish" refers to members of the unrelated family Batrachoididae. Frogfishes are f ...

, as well as cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

s such as the octopus

An octopus (: octopuses or octopodes) is a soft-bodied, eight-limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefish, and nautiloids. Like oth ...

and paper nautilus

The argonauts (genus ''Argonauta'', the only extant genus in the family Argonautidae) are a group of pelagic octopuses. They are also called paper nautili, referring to the paper-thin eggcase that females secrete; however, as octopuses, they are ...

. His description of the hectocotyl arm

A hectocotylus (: hectocotyli) is one of the arms of male cephalopods that is specialized to store and transfer spermatophores to the female. Structurally, hectocotyli are muscular hydrostats. Depending on the species, the male may use it merely a ...

of cephalopods, used in sexual reproduction, was widely disbelieved until the 19th century. He gives accurate descriptions of the four-chambered stomachs of ruminant

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microb ...

s, and of the ovoviviparous

Ovoviviparity, ovovivipary, ovivipary, or aplacental viviparity is a "bridging" form of reproduction between egg-laying oviparity, oviparous and live-bearing viviparity, viviparous reproduction. Ovoviviparous animals possess embryos that develo ...

embryological development of the hound shark

The Triakidae or houndsharks are a family (biology), family of Carcharhiniformes, ground sharks, consisting of about 40 species in nine genera. In some classifications, the family is split into two subfamilies, with the genera ''Mustelus'', ''Scy ...

.

He notes that an animal's structure is well matched to function so the heron

Herons are long-legged, long-necked, freshwater and coastal birds in the family Ardeidae, with 75 recognised species, some of which are referred to as egrets or bitterns rather than herons. Members of the genus ''Botaurus'' are referred to as bi ...

has a long neck, long legs, and a sharp spear-like beak, whereas duck

Duck is the common name for numerous species of waterfowl in the family (biology), family Anatidae. Ducks are generally smaller and shorter-necked than swans and goose, geese, which are members of the same family. Divided among several subfam ...

s have short legs and webbed feet. Darwin, too, noted such differences, but unlike Aristotle used the data to come to the theory of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

. Aristotle's writings can seem to imply evolution, but Aristotle saw mutations or hybridizations as rare accidents, distinct from natural causes. He was thus critical of Empedocles's theory of a "survival of the fittest" origin of living things and their organs, and ridiculed the idea that accidents could lead to orderly results. In modern terms, he nowhere says that different species can have a common ancestor

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. According to modern evolutionary biology, all living beings could be descendants of a unique ancestor commonl ...

, that one kind can change into another, or that kinds can become extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

.

Scientific style

Aristotle did not do experiments in the modern sense. He made observations, or at most investigative procedures like dissection. In ''Generation of Animals'', he opens a fertilized hen's egg to see the embryo's heart beating inside. Instead, he systematically gathered data, discovering patterns common to whole groups of animals, and inferring possible causal explanations from these. This style is common in modern biology when large amounts of data become available in a new field, such asgenomics

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of molecular biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, ...

. This sets out testable hypotheses and constructs a narrative explanation of what is observed. In this sense, Aristotle's biology

Aristotle's biology is the theory of biology, grounded in systematic observation and collection of data, mainly zoology, zoological, embodied in Aristotle's books on the science. Many of his observations were made during his stay on the island ...

is scientific.

From his data, Aristotle inferred rules

Rule or ruling may refer to:

Human activity

* The exercise of political or personal control by someone with authority or power

* Business rule, a rule pertaining to the structure or behavior internal to a business

* School rule, a rule tha ...

relating the life-history features of live-bearing tetrapods (terrestrial placental mammals) that he studied. He correctly predicted that brood size decreases with body mass; that lifespan increases with gestation period

In mammals, pregnancy is the period of reproduction during which a female carries one or more live offspring from implantation in the uterus through gestation. It begins when a fertilized zygote implants in the female's uterus, and ends once i ...

and with body mass, and that fecundity

Fecundity is defined in two ways; in human demography, it is the potential for reproduction of a recorded population as opposed to a sole organism, while in population biology, it is considered similar to fertility, the capability to produc ...

decreases with lifespan.

Classification of living things

Aristotle distinguished about 500animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...