Anglo-Norman Isles on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an

The two major islands are Jersey and Guernsey. They make up 99% of the population and 92% of the area.

The two major islands are Jersey and Guernsey. They make up 99% of the population and 92% of the area.

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Arch ...

in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

, off the French coast of Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey

A bailiwick () is usually the area of jurisdiction of a bailiff, and once also applied to territories in which a privately appointed bailiff exercised the sheriff's functions under a royal or imperial writ. The bailiwick is probably modelled on the ...

, which is the largest of the islands; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey

The Bailiwick of Guernsey (french: Bailliage de Guernesey; Guernésiais: ''Bailliage dé Guernési'') is an island country off the coast of France as one of the three Crown Dependencies.

Separated from the Duchy of Normandy by and under t ...

, consisting of Guernsey

Guernsey (; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; french: Guernesey) is an island in the English Channel off the coast of Normandy that is part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown Dependency.

It is the second largest of the Channel Islands ...

, Alderney

Alderney (; french: Aurigny ; Auregnais: ) is the northernmost of the inhabited Channel Islands. It is part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown Dependencies, Crown dependency. It is long and wide.

The island's area is , making i ...

, Sark

Sark (french: link=no, Sercq, ; Sercquiais: or ) is a part of the Channel Islands in the southwestern English Channel, off the coast of Normandy, France. It is a royal fief, which forms part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, with its own set of ...

, Herm

Herm ( Guernésiais: , ultimately from Old Norse 'arm', due to the shape of the island, or Old French 'hermit') is one of the Channel Islands and part of the Parish of St Peter Port in the Bailiwick of Guernsey. It is located in the English ...

and some smaller islands. They are considered the remnants of the Duchy of Normandy

The Duchy of Normandy grew out of the 911 Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King Charles III of West Francia and the Viking leader Rollo. The duchy was named for its inhabitants, the Normans.

From 1066 until 1204, as a result of the Norman c ...

and, although they are not part of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, the UK is responsible for the defence and international relations of the islands. The Crown dependencies are not members of the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the C ...

, nor have they ever been in the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

. They have a total population of about , and the bailiwicks' capitals

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

, Saint Helier

St Helier (; Jèrriais: ; french: Saint-Hélier) is one of the twelve parishes of Jersey, the largest of the Channel Islands in the English Channel. St Helier has a population of 35,822 – over one-third of the total population of Jersey – ...

and Saint Peter Port

St. Peter Port (french: Saint-Pierre Port) is a town and one of the ten parishes on the island of Guernsey in the Channel Islands. It is the capital of the Bailiwick of Guernsey as well as the main port. The population in 2019 was 18,958.

St. ...

, have populations of 33,500 and 18,207, respectively.

"Channel Islands" is a geographical term, not a political unit. The two bailiwick

A bailiwick () is usually the area of jurisdiction of a bailiff, and once also applied to territories in which a privately appointed bailiff exercised the sheriff's functions under a royal or imperial writ. The bailiwick is probably modelled on th ...

s have been administered separately since the late 13th century. Each has its own independent laws, elections, and representative bodies (although in modern times, politicians from the islands' legislatures are in regular contact). Any institution common to both is the exception rather than the rule.

The Bailiwick of Guernsey is divided into three jurisdictions – Guernsey, Alderney and Sark – each with its own legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known ...

. Although there are a few pan-island institutions (such as the Channel Islands Brussels Office, which is actually a joint venture between the bailiwicks), these tend to be established structurally as equal projects between Guernsey and Jersey. Otherwise, entities proclaiming membership of both Guernsey and Jersey might in fact be from one bailiwick only. For instance, the Channel Islands Securities Exchange is in Saint Peter Port and therefore is in Guernsey.

The term "Channel Islands" began to be used around 1830, possibly first by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

as a collective name for the islands. The term refers only to the archipelago to the west of the Cotentin Peninsula

The Cotentin Peninsula (, ; nrf, Cotentîn ), also known as the Cherbourg Peninsula, is a peninsula in Normandy that forms part of the northwest coast of France. It extends north-westward into the English Channel, towards Great Britain. To its w ...

. Other populated islands located in the English Channel, such as the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Is ...

, Hayling Island

Hayling Island is an island off the south coast of England, in the borough of Havant in the county of Hampshire, east of Portsmouth.

History

An Iron Age shrine in the north of Hayling Island was later developed into a Roman temple in the 1s ...

and Portsea Island

Portsea Island is a flat and low-lying natural island in area, just off the southern coast of Hampshire in England. Portsea Island contains the majority of the city of Portsmouth.

Portsea Island has the third-largest population of all ...

, are not regarded as "Channel Islands".

Geography

List of islands

Names

The names of the larger islands in the archipelago in general have the ''-ey'' suffix, whilst those of the smaller ones have the ''-hou

''-hou'' or ''hou'' is a place-name element found commonly in the Norman toponymy of the Channel Islands and continental Normandy.

Etymology and signification

Its etymology and meaning are disputed, but most specialists think it comes from Sax ...

'' suffix. These are believed to be from the Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlement ...

''ey'' (island) and ''holmr'' (islet).

The Chausey Islands

The Chausey Islands south of Jersey are not generally included in the geographical definition of the Channel Islands but are occasionally described in English as 'French Channel Islands' in view of their French jurisdiction. They were historically linked to the Duchy of Normandy, but they are part of the French territory along with continental Normandy, and not part of theBritish Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

or of the Channel Islands in a political sense. They are an incorporated part of the commune of Granville (Manche

Manche (, ) is a coastal French département in Normandy, on the English Channel, which is known as ''La Manche'', literally "the sleeve", in French. It had a population of 495,045 in 2019.Jersey Standard French, the Channel Islands are called 'Îles de la Manche', while in France, the term 'Îles Anglo-normandes' (Anglo-Norman Isles) is used to refer to the British 'Channel Islands' in contrast to other islands in the Channel. Chausey is referred to as an 'Île normande' (as opposed to ''anglo-normande''). 'Îles Normandes' and 'Archipel Normand' have also, historically, been used in Channel Island French to refer to the islands as a whole.

The islands were the only part of the

The islands were the only part of the  The population of Sark largely remained where they were; but in Alderney, all but six people left. In Alderney, the occupying Germans built four prison camps which housed approximately 6,000 people, of which over 700 died. Due to the destruction of documents, it is impossible to state how many forced workers died in the other islands. Alderney had the only Nazi concentration camps on

The population of Sark largely remained where they were; but in Alderney, all but six people left. In Alderney, the occupying Germans built four prison camps which housed approximately 6,000 people, of which over 700 died. Due to the destruction of documents, it is impossible to state how many forced workers died in the other islands. Alderney had the only Nazi concentration camps on

File:Flag of Jersey.svg, Flag of

The UK Parliament has power to legislate for the islands, but Acts of Parliament do not extend to the islands automatically. Usually, an Act gives power to extend its application to the islands by an

The UK Parliament has power to legislate for the islands, but Acts of Parliament do not extend to the islands automatically. Usually, an Act gives power to extend its application to the islands by an

The Norman language predominated in the islands until the nineteenth century, when increasing influence from English-speaking settlers and easier transport links led to Anglicisation. There are four main dialects/languages of Norman in the islands,

The Norman language predominated in the islands until the nineteenth century, when increasing influence from English-speaking settlers and easier transport links led to Anglicisation. There are four main dialects/languages of Norman in the islands,  The main islanders have traditional animal nicknames:

*Guernsey: ''les ânes'' (" donkeys" in French and Norman): the steepness of St Peter Port streets required beasts of burden, but Guernsey people also claim it is a symbol of their strength of characterwhich Jersey people traditionally interpret as stubbornness.

*Jersey: ''les crapauds'' ("

The main islanders have traditional animal nicknames:

*Guernsey: ''les ânes'' (" donkeys" in French and Norman): the steepness of St Peter Port streets required beasts of burden, but Guernsey people also claim it is a symbol of their strength of characterwhich Jersey people traditionally interpret as stubbornness.

*Jersey: ''les crapauds'' ("

States of AlderneyStates of GuernseyStates of JerseyGovernment of Sark

{{authority control British Isles Northwestern Europe Geography of Northwestern Europe English-speaking countries and territories French-speaking countries and territories Special territories of the European Union

Waters

The very large tidal variation provides an environmentally rich inter-tidal zone around the islands, and some islands such asBurhou

Burhou (pronounced ''ber-ROO'') is a small island about northwest of Alderney that is part of the Channel Islands. It has no permanent residents, and is a bird sanctuary, so landing there is banned from March 15 to August 1. The island's wildl ...

, the Écréhous, and the Minquiers

The Minquiers (''Les Minquiers''; in Jèrriais: ''Les Mîntchièrs'' ; known as "the Minkies" in local English) are a group of islands and rocks, about south of Jersey. They form part of the Bailiwick of Jersey.

They are administratively part of ...

have been designated Ramsar sites.

The waters around the islands include the following:

* The Swinge (between Alderney and Burhou)

*The Little Swinge (between Burhou and Les Nannels)

*La Déroute (between Jersey and Sark, and Jersey and the Cotentin)

*Le Raz Blanchard, or Race of Alderney (between Alderney and the Cotentin)

*The Great Russel

The Big/Great Roussel, Big Russel or Grand Ruau is the channel running between Herm on the west, and Brecqhou, and Sark on the east, in the Channel Islands. It has a treacherous current, and the tidal variations in this region are amongst some ...

(between Sark, Jéthou and Herm)

*The Little Russel (between Guernsey, Herm and Jéthou)

*Souachehouais (between Le Rigdon and L'Étacq, Jersey)

*Le Gouliot (between Sark and Brecqhou)

*La Percée (between Herm and Jéthou)

Highest point

The highest point in the islands is Les Platons in Jersey at 143 metres (469 ft) above sea level. The lowest point is the English Channel (sea level).Climate

History

Prehistory

The earliest evidence of human occupation of the Channel Islands has been dated to 250,000 years ago when they were attached to the landmass of continental Europe. The islands became detached byrising sea levels

Rising may refer to:

* Rising, a stage in baking - see Proofing (baking technique)

*Elevation

* Short for Uprising, a rebellion

Film and TV

* "Rising" (''Stargate Atlantis''), the series premiere of the science fiction television program ''Starg ...

in the Mesolithic period. The numerous dolmens and other archaeological sites extant and recorded in history demonstrate the existence of a population large enough and organised enough to undertake constructions of considerable size and sophistication, such as the burial mound at La Hougue Bie

La Hougue Bie is a historic site, with museum, in the Jersey parish of Grouville. La Hougue Bie is depicted on the 2010 issue Jersey 1 pound note.

Toponymy

''Hougue'' is a Jèrriais/Cotentin variant form of the more common Norman form ''Ho ...

in Jersey or the statue menhirs of Guernsey.

From the Iron Age

Hoards ofArmorica

Armorica or Aremorica (Gaulish: ; br, Arvorig, ) is the name given in ancient times to the part of Gaul between the Seine and the Loire that includes the Brittany Peninsula, extending inland to an indeterminate point and down the Atlantic Coast ...

n coins have been excavated, providing evidence of trade and contact in the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostl ...

period. Evidence for Roman settlement is sparse, although evidently the islands were visited by Roman officials and traders. The Roman name for the Channel Islands was ''I. Lenuri'' (Lenur Islands) and is included in the Peutinger Table

' (Latin for "The Peutinger Map"), also referred to as Peutinger's Tabula or Peutinger Table, is an illustrated ' (ancient Roman road map) showing the layout of the '' cursus publicus'', the road network of the Roman Empire.

The map is a 13th-ce ...

The traditional Latin names used for the islands (Caesarea for Jersey, Sarnia for Guernsey, Riduna for Alderney) derive (possibly mistakenly) from the Antonine Itinerary. Gallo-Roman culture was adopted to an unknown extent in the islands.

In the sixth century, Christian missionaries visited the islands. Samson of Dol

Samson of Dol (also Samsun; born late 5th century) was a Cornish saint, who is also counted among the seven founder saints of Brittany with Pol Aurelian, Tugdual or Tudwal, Brieuc, Malo, Patern (Paternus) and Corentin. Born in southern Wal ...

, Helier

Saint Helier (died 555) was a 6th-century ascetic hermit. He is the patron saint of Jersey in the Channel Islands, and in particular of the town and parish of Saint Helier, the island's capital. He is also invoked as a healing saint for diseases ...

, Marculf and Magloire are among saints associated with the islands. In the sixth century, they were already included in the diocese of Coutances

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Coutances (–Avranches) (Latin: ''Dioecesis Constantiensis (–Abrincensis)''; French: ''Diocèse de Coutances (–Avranches)'') is a diocese of the Roman Catholic Church in France. Its mother church is the Cathed ...

where they remained until the Reformation.

There were probably some Celtic Britons who settled on the Islands in the 5th and 6th centuries AD (the indigenous Celts of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

, and the ancestors of the modern Welsh, Cornish, and Bretons

The Bretons (; br, Bretoned or ''Vretoned,'' ) are a Celtic ethnic group native to Brittany. They trace much of their heritage to groups of Brittonic speakers who emigrated from southwestern Great Britain, particularly Cornwall and Devon, mo ...

) who had emigrated from Great Britain in the face of invading Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

. But there were not enough of them to leave any trace, and the islands continued to be ruled by the king of the Franks and its church remained part of the diocese of Coutances

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Coutances (–Avranches) (Latin: ''Dioecesis Constantiensis (–Abrincensis)''; French: ''Diocèse de Coutances (–Avranches)'') is a diocese of the Roman Catholic Church in France. Its mother church is the Cathed ...

.

From the beginning of the ninth century, Norse raiders appeared on the coasts. Norse settlement eventually succeeded initial attacks, and it is from this period that many place names of Norse origin appear, including the modern names of the islands.

From the Duchy of Normandy

In 933, the islands were granted toWilliam I Longsword

William Longsword (french: Guillaume Longue-Épée, nrf, Willâome de lon Espee, la, Willermus Longa Spata, on, Vilhjálmr Langaspjót; c. 893 – 17 December 942) was the second ruler of Normandy, from 927 until his assassination in 942.Det ...

by Raoul, the King of Western Francia, and annexed to the Duchy of Normandy

The Duchy of Normandy grew out of the 911 Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King Charles III of West Francia and the Viking leader Rollo. The duchy was named for its inhabitants, the Normans.

From 1066 until 1204, as a result of the Norman c ...

. In 1066, William II of Normandy

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 108 ...

invaded and conquered England, becoming William I of England, also known as William the Conqueror. In the period 1204–1214, King John lost the Angevin lands

The Angevin Empire (; french: Empire Plantagenêt) describes the possessions of the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly half of France, all of England, and parts of Ireland and ...

in northern France, including mainland Normandy, to King Philip II of France, but managed to retain control of the Channel Islands. In 1259, his successor, Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, Henry a ...

, by the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

, officially surrendered his claim and title to the Duchy of Normandy, while retaining the Channel Islands, as peer of France and feudal vassal of the King of France. Since then, the Channel Islands have been governed as two separate bailiwicks and were never absorbed into the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various History of Anglo-Saxon England, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, ...

nor its successor kingdoms of Great Britain and the United Kingdom. During the Hundred Years' War, the Channel Islands were part of the French territory recognizing the claims of the English kings to the French throne.

The islands were invaded by the French in 1338, who held some territory until 1345. Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ...

granted a Charter in July 1341 to Jersey, Guernsey, Sark and Alderney, confirming their customs and laws to secure allegiance to the English Crown. Owain Lawgoch

Owain Lawgoch ( en, Owain of the Red Hand, french: Yvain de Galles), full name Owain ap Thomas ap Rhodri (July 1378), was a Welsh soldier who served in Lombardy, France, Alsace, and Switzerland. He led a Free Company fighting for the French agai ...

, a mercenary leader of a Free Company in the service of the French Crown, attacked Jersey and Guernsey in 1372, and in 1373 Bertrand du Guesclin

Bertrand du Guesclin ( br, Beltram Gwesklin; 1320 – 13 July 1380), nicknamed "The Eagle of Brittany" or "The Black Dog of Brocéliande", was a Breton knight and an important military commander on the French side during the Hundred Years' Wa ...

besieged Mont Orgueil

Mont Orgueil (French for 'Mount Pride') is a castle in Jersey that overlooks the harbour of Gorey. It is also called Gorey Castle by English-speakers, and ''lé Vièr Châté'' (the Old Castle) by Jèrriais-speakers.The castle is first called 'M ...

. The young King Richard II of England reconfirmed in 1378 the Charter rights granted by his grandfather, followed in 1394 with a second Charter granting, because of great loyalty shown to the Crown, exemption for ever, from English tolls, customs and duties. Jersey was occupied by the French in 1461 as part of an exchange for helping the Lancastrians fight against the Yorkists during The War of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These wars were fought bet ...

. It was retaken by the Yorkists in 1468. In 1483 a Papal bull decreed that the islands would be neutral during time of war. This privilege of neutrality enabled islanders to trade with both France and England and was respected until 1689 when it was abolished by Order in Council

An Order-in-Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council (''Kin ...

following the Glorious Revolution in Great Britain.

Various attempts to transfer the islands from the diocese of Coutances (to Nantes (1400), Salisbury (1496), and Winchester (1499)) had little effect until an Order in Council of 1569 brought the islands formally into the diocese of Winchester

The Diocese of Winchester forms part of the Province of Canterbury of the Church of England. Founded in 676, it is one of the older dioceses in England. It once covered Wessex, many times its present size which is today most of the historic enl ...

. Control by the bishop of Winchester was ineffectual as the islands had turned overwhelmingly Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

and the episcopacy

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

was not restored until 1620 in Jersey and 1663 in Guernsey.

After the loss of Calais in 1558, the Channel Islands were the last remaining English holdings in France and the only French territory that was controlled by the English kings as Kings of France. This situation lasted until the English kings dropped their title and claims to the French throne in 1801, confirming the Channel Islands in a situation of a crown dependency under the sovereignty of neither Great-Britain nor France but of the British crown directly.

Sark in the 16th century was uninhabited until colonised from Jersey in the 1560s. The grant of seigneur

''Seigneur'' is an originally feudal title in France before the Revolution, in New France and British North America until 1854, and in the Channel Islands to this day. A seigneur refers to the person or collective who owned a ''seigneurie'' (or ...

ship from Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

in 1565 forms the basis of Sark's constitution today.

From the seventeenth century

During theWars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities united in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 B ...

, Jersey held out strongly for the Royalist cause, providing refuge for Charles, Prince of Wales

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to a ...

in 1646 and 1649–1650, while the more strongly Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

Guernsey more generally favoured the parliamentary cause (although Castle Cornet was held by Royalists and did not surrender until October 1651).

The islands acquired commercial and political interests in the North American colonies. Islanders became involved with the Newfoundland fisheries in the seventeenth century. In recognition for all the help given to him during his exile in Jersey in the 1640s, Charles II gave George Carteret

Vice Admiral Sir George Carteret, 1st Baronet ( – 14 January 1680 N.S.) was a royalist statesman in Jersey and England, who served in the Clarendon Ministry as Treasurer of the Navy. He was also one of the original lords proprietor of the ...

, Bailiff and governor, a large grant of land in the American colonies, which he promptly named New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

, now part of the United States of America. Sir Edmund Andros

Sir Edmund Andros (6 December 1637 – 24 February 1714) was an English colonial administrator in British America. He was the governor of the Dominion of New England during most of its three-year existence. At other times, Andros served ...

, bailiff of Guernsey, was an early colonial governor in North America, and head of the short-lived Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was an administrative union of English colonies covering New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies (except for Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvania). Its political structure rep ...

.

In the late eighteenth century, the Islands were dubbed "the French Isles". Wealthy French émigrés fleeing the Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

sought residency in the islands. Many of the town domiciles existing today were built in that time. In Saint Peter Port

St. Peter Port (french: Saint-Pierre Port) is a town and one of the ten parishes on the island of Guernsey in the Channel Islands. It is the capital of the Bailiwick of Guernsey as well as the main port. The population in 2019 was 18,958.

St. ...

, a large part of the harbour had been built by 1865.

20th century

World War II

The islands were the only part of the

The islands were the only part of the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

to be occupied by the German Army during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

.

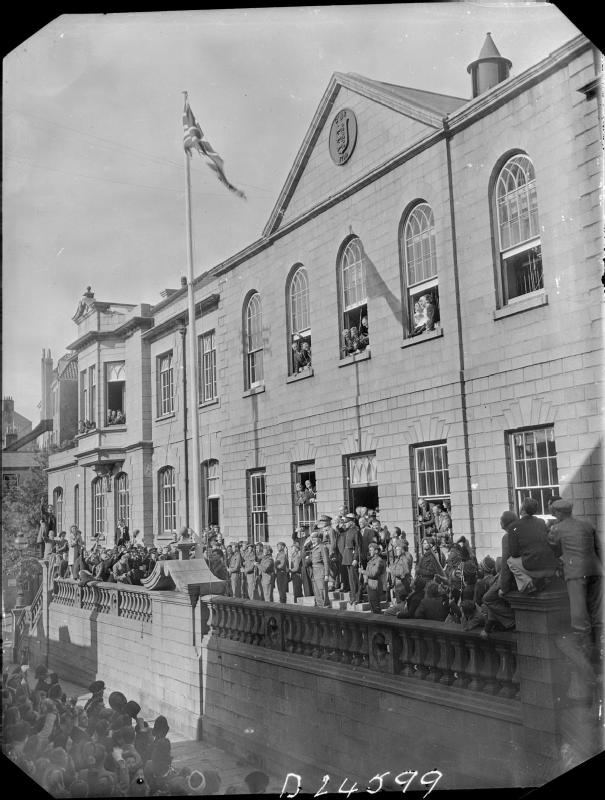

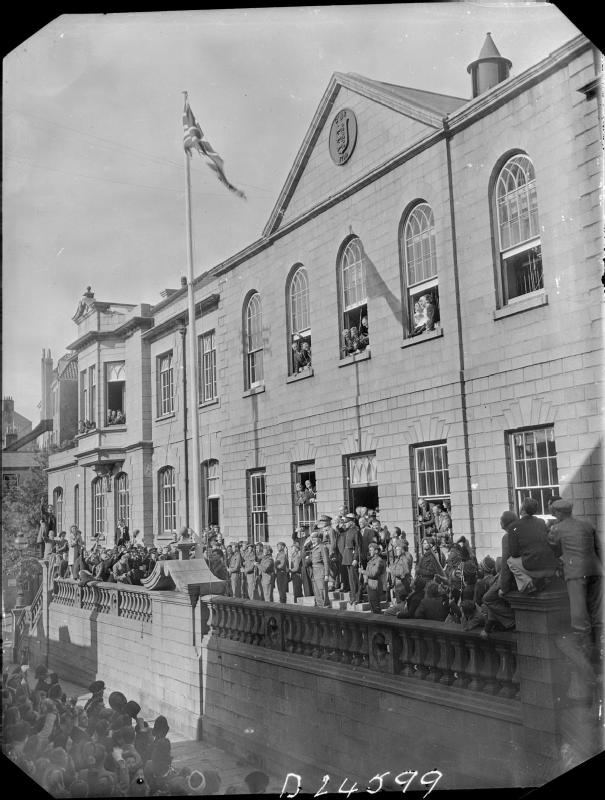

The British Government demilitarised the islands in June 1940, and the lieutenant-governors were withdrawn on 21 June, leaving the insular administrations to continue government as best they could under impending military occupation.

Before German troops landed, between 30 June and 4 July 1940, evacuation took place. Many young men had already left to join the Allied armed forces, as volunteers. 6,600 out of 50,000 left Jersey while 17,000 out of 42,000 left Guernsey. Thousands of children were evacuated with their schools to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

.

The population of Sark largely remained where they were; but in Alderney, all but six people left. In Alderney, the occupying Germans built four prison camps which housed approximately 6,000 people, of which over 700 died. Due to the destruction of documents, it is impossible to state how many forced workers died in the other islands. Alderney had the only Nazi concentration camps on

The population of Sark largely remained where they were; but in Alderney, all but six people left. In Alderney, the occupying Germans built four prison camps which housed approximately 6,000 people, of which over 700 died. Due to the destruction of documents, it is impossible to state how many forced workers died in the other islands. Alderney had the only Nazi concentration camps on British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

soil.

The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are leg ...

d the islands from time to time, particularly following the Invasion of Normandy in June 1944. There was considerable hunger and privation

Privation is the absence or lack of basic necessities.

Child psychology

In child psychology, privation occurs when a child has no opportunity to form a relationship with a parent figure, or when such relationship is distorted, due to their treat ...

during the five years of German occupation, particularly in the final months when the population was close to starvation. Intense negotiations resulted in some humanitarian aid being sent via the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, and ...

, leading to the arrival of Red Cross parcel

Red Cross parcel refers to packages containing mostly food, tobacco and personal hygiene items sent by the International Association of the Red Cross to prisoners of war during the First and Second World Wars, as well as at other times. It ...

s in the supply ship SS Vega in December 1944.

The German occupation of 1940–45 was harsh: over 2,000 Islanders were deported by the Germans,''The German Occupation of the Channel Islands'', Cruikshank, Oxford 1975 some Jews were sent to concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

; partisan resistance and retribution, accusations of collaboration, and slave labour also occurred. Many Spaniards, initially refugees from the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

, were brought to the islands to build fortification

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere' ...

s. Later, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

ns and Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

ans continued the work. Many land mine

A land mine is an explosive device concealed under or on the ground and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets, ranging from combatants to vehicles and tanks, as they pass over or near it. Such a device is typically detonated automati ...

s were laid, with 65,718 land mines laid in Jersey alone.

There was no resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to withstand the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. It may seek to achieve its objective ...

in the Channel Islands on the scale of that in mainland France. This has been ascribed to a range of factors including the physical separation of the Islands, the density of troops (up to one German for every two Islanders), the small size of the Islands precluding any hiding places for resistance groups, and the absence of the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

from the occupying forces. Moreover, much of the population of military age had already joined the British Army.

The end of the occupation came after VE-Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Easter ...

on 8 May 1945, with Jersey and Guernsey being liberated on 9 May. The German garrison in Alderney was left until 16 May, and it was one of the last of the Nazi German

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

remnants to surrender. The first evacuees returned on the first sailing from Great Britain on 23 June, but the people of Alderney were unable to start returning until December 1945. Many of the evacuees who returned home had difficulty reconnecting with their families after five years of separation.

After 1945

Following the liberation of 1945, reconstruction led to a transformation of the economies of the islands, attracting immigration and developing tourism. The legislatures were reformed and non-party governments embarked on social programmes, aided by the incomes fromoffshore finance

An offshore financial centre (OFC) is defined as a "country or jurisdiction that provides financial services to nonresidents on a scale that is incommensurate with the size and the financing of its domestic economy."

"Offshore" does not refer ...

, which grew rapidly from the 1960s. The islands decided not to join the European Economic Community when the UK joined. Since the 1990s, declining profitability of agriculture and tourism has challenged the governments of the islands.

Flag gallery

Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label= Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west France. It is the l ...

File:Flag of Guernsey.svg, Flag of Guernsey

Guernsey (; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; french: Guernesey) is an island in the English Channel off the coast of Normandy that is part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown Dependency.

It is the second largest of the Channel Islands ...

File:Flag of Alderney.svg, Flag of Alderney

Alderney (; french: Aurigny ; Auregnais: ) is the northernmost of the inhabited Channel Islands. It is part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown Dependencies, Crown dependency. It is long and wide.

The island's area is , making i ...

File:Flag of Sark.svg, Flag of Sark

Sark (french: link=no, Sercq, ; Sercquiais: or ) is a part of the Channel Islands in the southwestern English Channel, off the coast of Normandy, France. It is a royal fief, which forms part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, with its own set of ...

File:Flag of Herm.svg, Flag of Herm

Herm ( Guernésiais: , ultimately from Old Norse 'arm', due to the shape of the island, or Old French 'hermit') is one of the Channel Islands and part of the Parish of St Peter Port in the Bailiwick of Guernsey. It is located in the English ...

File:Flag of Brecqhou.svg, Flag of Brecqhou

Brecqhou (or Brechou; ) is one of the Channel Islands, located off the west coast of Sark where they are now geographically detached from each other. Brecqhou is politically part of both Sark and the Bailiwick of Guernsey. It has been establishe ...

Governance

The Channel Islands fall into two separateself-governing

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

bailiwick

A bailiwick () is usually the area of jurisdiction of a bailiff, and once also applied to territories in which a privately appointed bailiff exercised the sheriff's functions under a royal or imperial writ. The bailiwick is probably modelled on th ...

s, the Bailiwick of Guernsey

The Bailiwick of Guernsey (french: Bailliage de Guernesey; Guernésiais: ''Bailliage dé Guernési'') is an island country off the coast of France as one of the three Crown Dependencies.

Separated from the Duchy of Normandy by and under t ...

and the Bailiwick of Jersey

A bailiwick () is usually the area of jurisdiction of a bailiff, and once also applied to territories in which a privately appointed bailiff exercised the sheriff's functions under a royal or imperial writ. The bailiwick is probably modelled on the ...

. Both are British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

Crown Dependencies, and neither is a part of the United Kingdom. They have been parts of the Duchy of Normandy

The Duchy of Normandy grew out of the 911 Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King Charles III of West Francia and the Viking leader Rollo. The duchy was named for its inhabitants, the Normans.

From 1066 until 1204, as a result of the Norman c ...

since the tenth century, and Queen Elizabeth II was often referred to by her traditional and conventional title of Duke of Normandy. However, pursuant to the Treaty of Paris (1259)

The Treaty of Paris (also known as the Treaty of Albeville) was a treaty between Louis IX of France and Henry III of England, agreed to on 4 December 1259, ending 100 years of conflicts between the Capetian and Plantagenet dynasties.

History

...

, she governed in her right as The Queen (the "Crown in right of Jersey", and the "Crown in right of the ''république'' of the Bailiwick of Guernsey"), and not as the Duke. This notwithstanding, it is a matter of local pride for monarchists to treat the situation otherwise: the Loyal toast

A loyal toast is a salute given to the sovereign monarch or head of state of the country in which a formal gathering is being given, or by expatriates of that country, whether or not the particular head of state is present. It is usually a mat ...

at formal dinners was to 'The Queen, our Duke', rather than to 'Her Majesty, The Queen' as in the UK. The Queen died in 2022 and her son Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person t ...

became the King.

A bailiwick is a territory administered by a bailiff. Although the words derive from a common root ('bail' = 'to give charge of') there is a vast difference between the meanings of the word 'bailiff' in Great Britain and in the Channel Islands; a bailiff in Britain is a court-appointed private debt-collector authorised to collect judgment debts, in the Channel Islands, the Bailiff in each bailiwick is the civil head, presiding officer of the States, and also head of the judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

, and thus the most important citizen in the bailiwick.

In the early 21st century, the existence of governmental offices such as the bailiffs' with multiple roles straddling the different branches of government came under increased scrutiny for their apparent contravention of the doctrine of separation of powers—most notably in the Guernsey case of ''McGonnell -v- United Kingdom'' (2000) 30 EHRR 289. That case, following final judgement at the European Court of Human Rights, became part of the impetus for much recent constitutional change, particularly the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 (2005 c.4) in the UK, including the separation of the roles of the Lord Chancellor, the abolition of the House of Lords' judicial role, and its replacement by the UK Supreme Court. The islands' bailiffs, however, still retain their historic roles.

The systems of government in the islands date from Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

times, which accounts for the names of the legislatures, the States, derived from the Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

'États' or ' estates' (i.e. the Crown, the Church, and the people). The States have evolved over the centuries into democratic parliaments.

The UK Parliament has power to legislate for the islands, but Acts of Parliament do not extend to the islands automatically. Usually, an Act gives power to extend its application to the islands by an

The UK Parliament has power to legislate for the islands, but Acts of Parliament do not extend to the islands automatically. Usually, an Act gives power to extend its application to the islands by an Order in Council

An Order-in-Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council (''Kin ...

, after consultation. For the most part the islands legislate for themselves. Each island has its own primary legislature, known as the States of Guernsey and the States of Jersey, with Chief Pleas in Sark and the States of Alderney. The Channel Islands are not represented in the UK Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

. Laws passed by the States are given royal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in oth ...

by The Queen in Council, to whom the islands' governments are responsible.

The islands have never been part of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

, and thus were not a party to the 2016 referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

on the EU membership, but were part of the Customs Territory of the European Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisb ...

by virtue of Protocol Three to the Treaty on European Union

The Treaty on European Union (2007) is one of the primary Treaties of the European Union, alongside the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). The TEU form the basis of EU law, by setting out general principles of the EU's ...

. In September 2010, a Channel Islands Brussels Office was set up jointly by the two Bailiwicks to develop the Channel Islands' influence with the EU, to advise the Channel Islands' governments on European matters, and to promote economic links with the EU.

Both bailiwicks are members of the British–Irish Council

The British–Irish Council (BIC) ( ga, Comhairle na Breataine-na hÉireann) is an intergovernmental organisation that aims to improve collaboration between its members in a number of areas including transport, the environment, and energy. Its ...

, and Jèrriais and Guernésiais

Guernésiais, also known as ''Dgèrnésiais'', Guernsey French, and Guernsey Norman French, is the variety of the Norman language spoken in Guernsey. It is sometimes known on the island simply as "patois". As one of the langues d'oïl, it has it ...

are recognised regional language

*

A regional language is a language spoken in a region of a sovereign state, whether it be a small area, a federated state or province or some wider area.

Internationally, for the purposes of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Lan ...

s of the islands.

The legal courts are separate; separate courts of appeal have been in place since 1961. Among the legal heritage from Norman law is the Clameur de haro

The () is an ancient legal injunction of restraint employed by a person who believes they are being wronged by another at that moment. It survives as a fully enforceable law to this day in the legal systems of Jersey and Guernsey, and is use ...

. The basis of the legal systems of both Bailiwicks is Norman customary law (Coutume

Old French law, referred to in French as ''l'Ancien Droit'', was the law of the Kingdom of France until the French Revolution. In the north of France were the ''Pays de coutumes'' ('customary countries'), where customary laws were in force, whil ...

) rather than the English Common Law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipres ...

, although elements of the latter have become established over time.

Islanders are full British citizens, but were not classed as European citizens unless by descent from a UK national. Any British citizen who applies for a passport in Jersey or Guernsey receives a passport bearing the words "British Islands

The British Islands is a term within the law of the United Kingdom which refers collectively to the following four polities:

* the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (formerly the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland) ...

, Bailiwick of Jersey" or "British Islands, Bailiwick of Guernsey". Under the provisions of Protocol Three, Channel Islanders who do not have a close connection with the UK (no parent or grandparent from the UK, and have never been resident in the UK for a five-year period) did not automatically benefit from the EU provisions on free movement within the EU, and their passports received an endorsement to that effect. This affected only a minority of islanders.

Under the UK Interpretation Act 1978

The Interpretation Act 1978 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act makes provision for the interpretation of Acts of Parliament, Measures of the General Synod of the Church of England, Measures of the Church Assembly, subor ...

, the Channel Islands are deemed to be part of the British Islands, not to be confused with the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

. For the purposes of the British Nationality Act 1981

The British Nationality Act 1981 (c.61) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom concerning British nationality since 1 January 1983.

History

In the mid-1970s the British Government decided to update the nationality code, which had b ...

, the "British Islands" include the United Kingdom (Great Britain and Northern Ireland), the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

, taken together, unless the context otherwise requires.

Economy

Tourism is still important. However, Jersey and Guernsey have, since the 1960s, become majoroffshore financial centre

An offshore financial centre (OFC) is defined as a "country or jurisdiction that provides financial services to nonresidents on a scale that is incommensurate with the size and the financing of its domestic economy."

"Offshore" does not refer ...

s. Historically Guernsey's horticultural and greenhouse activities have been more significant than in Jersey, and Guernsey has maintained light industry

Light industry are industries that usually are less capital-intensive than heavy industry and are more consumer-oriented than business-oriented, as they typically produce smaller consumer goods. Most light industry products are produced for ...

as a higher proportion of its economy than Jersey. In Jersey, potatoes are an important export crop, shipped mostly to the UK.

Jersey is heavily reliant on financial services, with 39.4% of Gross Value Added (GVA) in 2018 contributed by the sector. Rental income comes second at 15.1% with other business activities at 11.2%. Tourism 4.5% with agriculture contributing just 1.2% and manufacturing even lower at 1.1%. GVA has fluctuated between £4.5 and £5 billion for 20 years.

Jersey has had a steadily rising population, increasing from below 90,000 in 2000 to over 105,000 in 2018 which combined with a flat GVA has resulted in GVA per head of population falling from £57,000 to £44,000 per person. Guernsey had a GDP of £3.2 billion in 2018 and with a stable population of around 66,000 has had a steadily rising GDP, and a GVA per head of population which in 2018 surpassed £52,000.

Both bailiwicks issue their own banknotes and coins, which circulate freely in all the islands alongside UK coinage and Bank of England and Scottish banknotes.

Transport and communications

Post

Since 1969, Jersey and Guernsey have operated postal administrations independently of the UK's Royal Mail, with their own postage stamps, which can be used for postage only in their respective Bailiwicks. UK stamps are no longer valid, but mail to the islands, and to theIsle of Man

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

, is charged at UK inland rates. It was not until the early 1990s that the islands joined the UK's postcode system, Jersey postcodes using the initials JE and Guernsey GY.

Transport

Road

Each of the three largest islands has a distinct vehicle registration scheme: *Guernsey (GBG): a number of up to five digits; *Jersey (GBJ): ''J'' followed by up to six digits (''JSY'' vanity plates are also issued); *Alderney (GBA): ''AY'' followed by up to five digits (four digits are the most that have been used, as redundant numbers are re-issued). InSark

Sark (french: link=no, Sercq, ; Sercquiais: or ) is a part of the Channel Islands in the southwestern English Channel, off the coast of Normandy, France. It is a royal fief, which forms part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, with its own set of ...

, where most motor traffic is prohibited, the few vehicles – nearly all tractors – do not display plates. Bicycles display tax discs.

Sea

In the 1960s, names used for the cross-Channel ferries plying the mail route between the islands and Weymouth, Dorset, were taken from the popular Latin names for the islands: ''Caesarea'' (Jersey), ''Sarnia'' (Guernsey) and ''Riduna'' (Alderney). Fifty years later, the ferry route between the Channel Islands and the UK is operated byCondor Ferries

Condor Ferries is an operator of passenger and freight ferry services between The United Kingdom, Bailiwick of Guernsey, Bailiwick of Jersey and France.

Corporate history

Condor Ferries established the first high-speed car ferry service to ...

from both St Helier, Jersey and St Peter Port, Guernsey, using high-speed catamaran fast craft to Poole in the UK. A regular passenger ferry service on the Commodore Clipper goes from both Channel Island ports to Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

daily, and carries both passengers and freight.

Ferry services to Normandy are operated by Manche Îles Express, and services between Jersey and Saint-Malo

Saint-Malo (, , ; Gallo: ; ) is a historic French port in Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany, on the English Channel coast.

The walled city had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth from local extortion and overseas adventures. In 1944, the Alli ...

are operated by Compagnie Corsaire and Condor Ferries.

The Isle of Sark Shipping Company operates small ferries to Sark.

On 20 August 2013, Huelin-Renouf, which had operated a "lift-on lift-off" container service for 80 years between the Port of Southampton

The Port of Southampton is a passenger and cargo port in the central part of the south coast of England. The modern era in the history of the Port of Southampton began when the first dock was inaugurated in 1843. The port has been owned and op ...

and the Port of Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label= Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west France. It is the l ...

, ceased trading. Senator Alan Maclean, a Jersey politician, had previously tried to save the 90-odd jobs furnished by the company to no avail. On 20 September, it was announced that Channel Island Lines

Channel, channels, channeling, etc., may refer to:

Geography

* Channel (geography), in physical geography, a landform consisting of the outline (banks) of the path of a narrow body of water.

Australia

* Channel Country, region of outback Austral ...

would continue this service, and would purchase the MV Huelin Dispatch from Associated British Ports who in turn had purchased them from the receiver in the bankruptcy. The new operator was to be funded by Rockayne Limited, a closely held association of Jersey businesspeople.

Air

There are three airports in the Channel Islands;Alderney Airport

Alderney Airport is the only airport on the island of Alderney, Guernsey. Built in 1935, Alderney Airport was the first airport in the Channel Islands. Located on the Blaye ( southwest of St Anne), it is the closest Channel Island airport to th ...

, Guernsey Airport

Guernsey Airport is an international airport on the island of Guernsey and the largest airport in the Bailiwick of Guernsey. It is located in the Forest, a parish in Guernsey, southwest of St. Peter Port and features mostly flights to Great B ...

and Jersey Airport

Jersey Airport is an international airport located in the parish of Saint Peter, west northwest of Saint Helier in Jersey, in the Channel Islands.

History

Air service to Jersey before 1937 consisted of biplane airliners and some seaplanes la ...

, which are directly connected to each other by services operated by Blue Islands

Blue Islands Limited is a British regional airline of the Channel Islands. Its head office is in Saint Peter, Jersey, and its registered office is in Saint Anne, Alderney. It operates scheduled services from and within the Channel Islands to ...

and Aurigny

Aurigny Air Services Limited (pronounced ), commonly known as Aurigny, is the flag carrier airline of the Bailiwick of Guernsey with its head office next to Guernsey Airport in the Channel Islands, and wholly owned by the States of Guernse ...

.

Rail

Historically, there have been railway networks on Jersey, Guernsey, and Alderney, but all of the lines on Jersey and Guernsey have been closed and dismantled. Today there are three working railways in the Channel Islands, of which theAlderney Railway

The Alderney Railway on Alderney is the only railway in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, and the only working railway in the Channel Islands. (There is a standard gauge railway at the Pallot Heritage Steam Museum in Jersey, but this provides no actua ...

is the only one providing a regular timetabled passenger service. The other two are a gauge miniature railway, also on Alderney, and the heritage steam railway operated on Jersey as part of the Pallot Heritage Steam Museum

The Pallot Heritage Steam Museum is a mechanical heritage museum located in Rue De Bechet in the Parish of Trinity on the island of Jersey.

Museum origins

Lyndon Pallot (known as Don) amassed a large collection of Jersey's mechanical, agricul ...

.

Media

The Channel Islands are served by a number of local radio services -BBC Radio Jersey

BBC Radio Jersey (Jèrriais: ''BBC Radio Jèrri'') is the BBC's local radio station serving the Bailiwick of Jersey. It broadcasts on FM, AM, DAB+, Freeview and via BBC Sounds from studios on Parade Road in Saint Helier. Like other BBC enter ...

and BBC Radio Guernsey

BBC Radio Guernsey is the BBC's local radio station serving the Bailiwick of Guernsey.

It broadcasts on FM, AM, DAB, digital TV and via BBC Sounds from studios on Bulwer Avenue in St Sampson.

According to RAJAR, the station has a weekly au ...

, Channel 103

Channel 103 is an independent local radio station broadcasting to the island of Jersey on 103.7 FM and DAB+ digital radio.

The station launched on 25 October 1992. Channel 103 is part of Tindle Radio, which also owns Island FM in Guernsey and ...

and Island FM

Island FM is an Independent Local Radio station broadcasting across the Bailiwick of Guernsey on 104.7FM and 93.7FM in Alderney.

Launched in 1992, Island FM remains the sole commercial station in the island and continues to be extremely succes ...

- as well as regional television news opt-outs from BBC Channel Islands and ITV Channel Television

ITV Channel Television, previously Channel Television, is a British television station which has served as the ITV contractor for the Channel Islands since 1962. It is based in Jersey and broadcasts regional programme for insertion into the ...

.

On 1 August 2021, DAB+ digital radio became available for the first time, introducing new stations like the local Bailiwick Radio and Soleil Radio, and UK-wide services like Capital, Heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide to t ...

, and Times Radio

Times Radio is a British digital radio station owned by News UK. It is jointly operated by Wireless Group (which News UK acquired in 2016), ''The Times'' and ''The Sunday Times''.

As of September 2022, the station broadcasts to a weekly audienc ...

.

There are two broadcast transmitters serving Jersey - at Frémont Point and Les Platons - as well as one at Les Touillets in Guernsey and a relay in Alderney.

There are several local newspapers including the Guernsey Press

The ''Guernsey Press and Star'', more commonly known as the ''Guernsey Press'' is the only daily newspaper published in Guernsey.

History

The ''Guernsey Evening Press'' was first published in 1897. In 1951 it purchased the struggling ''Guernse ...

and the Jersey Evening Post

The ''Jersey Evening Post'' (''JEP'') is a local newspaper published six days a week in the Bailiwick of Jersey. It was printed in broadsheet format for 87 years, though it is now of compact ( tabloid) size. Its strapline is: "At the heart of ...

and magazines.

Telephone

Jersey always operated its own telephone services independently of Britain's national system, Guernsey established its own telephone service in 1968. Both islands still form part of the British telephone numbering plan, but Ofcom on the mainlines does not have responsibility for telecommunications regulatory and licensing issues on the islands. It is responsible for wireless telegraphy licensing throughout the islands, and by agreement, for broadcasting regulation in the two large islands only. Submarine cables connect the various islands and provide connectivity with England and France.Internet

Modern broadband speeds are available in all the islands, including full-fibre (FTTH

Fiber to the ''x'' (FTTX; also spelled "fibre") or fiber in the loop is a generic term for any broadband network architecture using optical fiber to provide all or part of the local loop used for last mile telecommunications. As fiber op ...

) in Jersey (offering speeds of up to 1Gbps on all broadband connections) and VDSL

Very high-speed digital subscriber line (VDSL) and very high-speed digital subscriber line 2 (VDSL2) are digital subscriber line (DSL) technologies providing data transmission faster than the earlier standards of asymmetric digital subscriber li ...

and some business fibre connectivity in Guernsey. Providers include Sure and JT.

The two Bailiwicks each have their own internet domain, .GG

.gg is the country code top-level domain for the Bailiwick of Guernsey. The domain is administered by Island Networks, who also administer the .je domain for neighbouring territory Jersey. The domain was chosen as other possible codes were al ...

(Guernsey, Alderney, Sark) and .JE

.je is the country code top-level domain for Jersey. The domain is administered by Island Networks, who also administer the .gg domain for neighbouring territory Guernsey. In 2003, a Google Search website was made available for Jersey, which us ...

(Jersey), which are managed by channelisles.net.

Culture

The Norman language predominated in the islands until the nineteenth century, when increasing influence from English-speaking settlers and easier transport links led to Anglicisation. There are four main dialects/languages of Norman in the islands,

The Norman language predominated in the islands until the nineteenth century, when increasing influence from English-speaking settlers and easier transport links led to Anglicisation. There are four main dialects/languages of Norman in the islands, Auregnais

Auregnais, Aoeur'gnaeux, or Aurignais was the Norman dialect of the Channel Island of Alderney (french: Aurigny, Auregnais: ''aoeur'gny'' or ''auregny''). It was closely related to the Guernésiais (Guernsey), Jèrriais ( Jersey), and Sercqui ...

(Alderney, extinct in late twentieth century), Dgèrnésiais (Guernsey), Jèrriais (Jersey) and Sercquiais

, also known as , Sarkese or Sark-French, is the Norman dialect of the Channel Island of Sark (Bailiwick of Guernsey).

Sercquiais is a descendant of the 16th century Jèrriais used by the original colonists, 40 families mostly from Saint Ouen, ...

(Sark, an offshoot of Jèrriais).

Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

spent many years in exile, first in Jersey and then in Guernsey, where he finished ''Les Misérables

''Les Misérables'' ( , ) is a French historical novel by Victor Hugo, first published in 1862, that is considered one of the greatest novels of the 19th century.

In the English-speaking world, the novel is usually referred to by its origin ...

''. Guernsey is the setting of Hugo's later novel ''Les Travailleurs de la Mer'' ('' Toilers of the Sea''). A "Guernsey-man" also makes an appearance in chapter 91 of Herman Melville

Herman Melville ( born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works are ''Moby-Dick'' (1851); ''Typee'' (1846), a rom ...

's ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is the sailor Ishmael's narrative of the obsessive quest of Ahab, captain of the whaling ship ''Pequod'', for revenge against Moby Dick, the giant whi ...

''.

The annual " Muratti", the inter-island football match, is considered the sporting event of the year, although, due to broadcast coverage, it no longer attracts the crowds of spectators, travelling between the islands, that it did during the twentieth century.

Cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by str ...

is popular in the Channel Islands. The Jersey cricket team and the Guernsey cricket team are both associate members of the International Cricket Council

The International Cricket Council (ICC) is the world governing body of cricket. Headquartered in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, its members are 108 national associations, with 12 Full Members and 96 Associate Members. Founded in 1909 as the ' ...

. The teams have played each other in the inter-insular match since 1957. In 2001 and 2002, the Channel Islands entered a team into the MCCA Knockout Trophy

The National Counties Cricket Association Knockout Cup was started in 1983 as a knockout one-day competition for the National Counties in English cricket. At first it was known as the ''English Industrial Estates Cup'', before being called the ...

, the one-day tournament of the minor counties of English and Welsh cricket.

Channel Island sportsmen and women compete in the Commonwealth Games

The Commonwealth Games, often referred to as the Friendly Games or simply the Comm Games, are a quadrennial international multi-sport event among athletes from the Commonwealth of Nations. The event was first held in 1930, and, with the exce ...

for their respective islands and the islands have also been enthusiastic supporters of the Island Games

The Island Games (currently known as the NatWest International Island Games for sponsorship reasons) are biennial international multi-sports events organised by the International Island Games Association (IIGA). Competitor teams each represent d ...

. Shooting is a popular sport, in which islanders have won Commonwealth medals.

Guernsey's traditional colour for sporting and other purposes is green and Jersey's is red.

The main islanders have traditional animal nicknames:

*Guernsey: ''les ânes'' (" donkeys" in French and Norman): the steepness of St Peter Port streets required beasts of burden, but Guernsey people also claim it is a symbol of their strength of characterwhich Jersey people traditionally interpret as stubbornness.

*Jersey: ''les crapauds'' ("

The main islanders have traditional animal nicknames:

*Guernsey: ''les ânes'' (" donkeys" in French and Norman): the steepness of St Peter Port streets required beasts of burden, but Guernsey people also claim it is a symbol of their strength of characterwhich Jersey people traditionally interpret as stubbornness.

*Jersey: ''les crapauds'' ("toad

Toad is a common name for certain frogs, especially of the family Bufonidae, that are characterized by dry, leathery skin, short legs, and large bumps covering the parotoid glands.

A distinction between frogs and toads is not made in scient ...

s" in French and Jèrriais): Jersey has toads and snakes, which Guernsey lacks.

*Sark: ''les corbins'' ("crow

A crow is a bird of the genus '' Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

s" in Sercquiais

, also known as , Sarkese or Sark-French, is the Norman dialect of the Channel Island of Sark (Bailiwick of Guernsey).

Sercquiais is a descendant of the 16th century Jèrriais used by the original colonists, 40 families mostly from Saint Ouen, ...

, Dgèrnésiais and Jèrriais, ''les corbeaux'' in French): crows could be seen from the sea on the island's coast.

*Alderney: ''les lapins'' (" rabbits" in French and Auregnais

Auregnais, Aoeur'gnaeux, or Aurignais was the Norman dialect of the Channel Island of Alderney (french: Aurigny, Auregnais: ''aoeur'gny'' or ''auregny''). It was closely related to the Guernésiais (Guernsey), Jèrriais ( Jersey), and Sercqui ...

): the island is noted for its warren

A warren is a network of wild rodent or lagomorph, typically rabbit burrows. Domestic warrens are artificial, enclosed establishment of animal husbandry dedicated to the raising of rabbits for meat and fur. The term evolved from the medieval A ...

s.

Religion

Christianity was brought to the islands around the sixth century; according to tradition, Jersey was evangelised by StHelier

Saint Helier (died 555) was a 6th-century ascetic hermit. He is the patron saint of Jersey in the Channel Islands, and in particular of the town and parish of Saint Helier, the island's capital. He is also invoked as a healing saint for diseases ...

, Guernsey by St Samson of Dol

Samson of Dol (also Samsun; born late 5th century) was a Cornish saint, who is also counted among the seven founder saints of Brittany with Pol Aurelian, Tugdual or Tudwal, Brieuc, Malo, Patern (Paternus) and Corentin. Born in southern Wal ...

, and the smaller islands were occupied at various times by monastic communities representing strands of Celtic Christianity. At the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, the previously Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome