Mesolithic Britain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Several species of humans have intermittently occupied

Sites such as

Sites such as  This period is often divided into three subperiods: the Early Upper Palaeolithic (before the main glacial period), the Middle-Upper Palaeolithic (the main glacial period) and the Late Upper Palaeolithic (after the main glacial period). There was limited Neanderthal occupation of Britain in

This period is often divided into three subperiods: the Early Upper Palaeolithic (before the main glacial period), the Middle-Upper Palaeolithic (the main glacial period) and the Late Upper Palaeolithic (after the main glacial period). There was limited Neanderthal occupation of Britain in

The Younger Dryas was followed by the

The Younger Dryas was followed by the

"Formal definition and dating of the GSSP (Global Stratotype Section and Point) for the base of the Holocene using the Greenland NGRIP ice core, and selected auxiliary records"

''J. Quaternary Sci.'', Vol. 24 pp. 3–17. . and continues to the present. There was then limited occupation by It is likely that these environmental changes were accompanied by social changes. Humans spread and reached the far north of Scotland during this period. Sites from the British Mesolithic include the Mendips,

It is likely that these environmental changes were accompanied by social changes. Humans spread and reached the far north of Scotland during this period. Sites from the British Mesolithic include the Mendips,

further example

has also been identified at

The Neolithic was the period of domestication of plants and animals, but the arrival of a Neolithic package of farming and a sedentary lifestyle is increasingly giving way to a more complex view of the changes and continuities in practices that can be observed from the Mesolithic period onwards. For example, the development of Neolithic monumental architecture, apparently venerating the dead, may represent more comprehensive social and ideological changes involving new interpretations of time, ancestry, community and identity.

In any case, the

The Neolithic was the period of domestication of plants and animals, but the arrival of a Neolithic package of farming and a sedentary lifestyle is increasingly giving way to a more complex view of the changes and continuities in practices that can be observed from the Mesolithic period onwards. For example, the development of Neolithic monumental architecture, apparently venerating the dead, may represent more comprehensive social and ideological changes involving new interpretations of time, ancestry, community and identity.

In any case, the  Different pottery types, such as grooved ware, appear during the later Neolithic (c. 2900 BC – c. 2200 BC). In addition, new enclosures called

Different pottery types, such as grooved ware, appear during the later Neolithic (c. 2900 BC – c. 2200 BC). In addition, new enclosures called

/ref> Analysis of the

(full text) However, more widespread studies have suggested that there was less of a division between Western and Eastern parts of Britain with less Anglo-Saxon migration. Looking from a more Europe-wide standpoint, researchers at Stanford University have found overlapping cultural and genetic evidence that supports the theory that migration was at least partially responsible for the Neolithic Revolution in Northern Europe (including Britain). The science of genetic anthropology is changing very fast and a clear picture across the whole of human occupation of Britain has yet to emerge.

(full text)

This period can be sub-divided into an earlier phase (2300 to 1200 BC) and a later one (1200 – 700 BC). Beaker pottery appears in England around 2475–2315 ''cal.'' BC along with flat axes and burial practices of

This period can be sub-divided into an earlier phase (2300 to 1200 BC) and a later one (1200 – 700 BC). Beaker pottery appears in England around 2475–2315 ''cal.'' BC along with flat axes and burial practices of

In around 750 BC iron working techniques reached Britain from southern Europe.

In around 750 BC iron working techniques reached Britain from southern Europe.  Iron Age Britons lived in organised tribal groups, ruled by a chieftain. As people became more numerous,

Iron Age Britons lived in organised tribal groups, ruled by a chieftain. As people became more numerous,

The last centuries before the Roman invasion saw an influx of

The last centuries before the Roman invasion saw an influx of

Ancient Human Occupation of Britain ProjectBritain's human history revealedScottish Archaeological Research Framework

(ScARF)

700,000-year-old remains in NorfolkThe Boxgrove projectAncient Britons come mainly from Spain

*[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3qZo0_YaBhc Britain BC Episode 1, the first episode of the film of Dr. Francis Pryor, a known expert on the Bronze Age, about British civilization, flourishing long before the Romans.] {{History of the British Isles, bar=yes Prehistoric Britain, Prehistoric Europe, Britain Prehistory by country, Britain Archaeology of the United Kingdom

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

for almost a million years. The earliest evidence of human occupation around 900,000 years ago is at Happisburgh

Happisburgh () is a village civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. The village is on the coast, to the east of a north–south road, the B1159 from Bacton on the coast to Stalham. It is a nucleated village. The nearest substantial ...

on the Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

coast, with stone tools and footprints

Footprints are the impressions or images left behind by a person walking or running. Hoofprints and pawprints are those left by animals with hoof, hooves or paws rather than foot, feet, while "shoeprints" is the specific term for prints made by ...

probably made by ''Homo antecessor

''Homo antecessor'' (Latin "pioneer man") is an extinct species of archaic human recorded in the Spanish Archaeological Site of Atapuerca, Sierra de Atapuerca, a productive archaeological site, from 1.2 to 0.8 million years ago during the Early ...

''. The oldest human fossils, around 500,000 years old, are of ''Homo heidelbergensis

''Homo heidelbergensis'' is a species of archaic human from the Middle Pleistocene of Europe and Africa, as well as potentially Asia depending on the taxonomic convention used. The species-level classification of ''Homo'' during the Middle Pleis ...

'' at Boxgrove

Boxgrove is a village, parish, ecclesiastical parish and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Chichester (district), Chichester District of the English county of West Sussex, about north east of the city of Chichester. The village is ...

in Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

. Until this time Britain had been permanently connected to the Continent by a chalk ridge between South East England

South East England is one of the nine official regions of England, regions of England that are in the ITL 1 statistical regions of England, top level category for Statistics, statistical purposes. It consists of the nine counties of england, ...

and northern France called the Weald-Artois Anticline, but during the Anglian Glaciation around 425,000 years ago a megaflood broke through the ridge, and Britain became an island when sea levels rose during the following Hoxnian interglacial.

Fossils of very early Neanderthal

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinction, extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle to Late Plei ...

s dating to around 400,000 years ago have been found at Swanscombe

Swanscombe /ˈswɔnzkəm/ is a town in the Borough of Dartford in Kent, England, and the civil parish of Swanscombe and Greenhithe. It is 4.4 miles west of Gravesend and 4.8 miles east of Dartford.

History

Prehistory

Bone fragments and to ...

in Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

, and of classic Neanderthals about 225,000 years old at Pontnewydd

Pontnewydd is a suburb of Cwmbran in the county borough of Torfaen, south-east Wales. It should not be confused with Pontnewynydd in nearby Pontypool.

An 18th century settlement within the historical parish of Llanfrechfa Upper, Pontnewydd b ...

in Wales. Britain was unoccupied by humans between 180,000 and 60,000 years ago, when Neanderthals returned. By 40,000 years ago they had become extinct and modern humans had reached Britain. But even their occupations were brief and intermittent due to a climate which swung between low temperatures with a tundra habitat and severe ice ages which made Britain uninhabitable for long periods. The last of these, the Younger Dryas

The Younger Dryas (YD, Greenland Stadial GS-1) was a period in Earth's geologic history that occurred circa 12,900 to 11,700 years Before Present (BP). It is primarily known for the sudden or "abrupt" cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, when the ...

, ended around 11,700 years ago, and since then Britain has been continuously occupied.

Traditionally it was claimed by academics that a post-glacial land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea le ...

existed between Britain and Ireland, however this conjecture began to be refuted by a consensus within the academic community starting in 1983, and since 2006 the idea of a land bridge has been disproven based upon conclusive marine geological evidence. It is now concluded that an ice bridge

An ice bridge is a frozen natural structure formed over seas, bays, rivers or lake surfaces. They facilitate migration of animals or people over a water body that was previously uncrossable by terrestrial animals, including humans. The most signi ...

existed between Britain and Ireland up until 16,000 years ago, but this had melted by around 14,000 years ago. Britain was at this time still joined to the Continent by a land bridge known as Doggerland

Doggerland was a large area of land in Northern Europe, now submerged beneath the southern North Sea. This region was repeatedly exposed at various times during the Pleistocene epoch due to the lowering of sea levels during glacial periods. Howe ...

, but due to rising sea levels

The sea level has been rising from the end of the last ice age, which was around 20,000 years ago. Between 1901 and 2018, the average sea level rose by , with an increase of per year since the 1970s. This was faster than the sea level had e ...

this causeway of dry land would have become a series of estuaries, inlets and islands by 7000 BC, and by 6200 BC, it would have become completely submerged.Cunliffe, 2012, pp. 47–56

Located at the fringes of Europe, Britain received European technological and cultural developments much later than Southern Europe

Southern Europe is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, C ...

and the Mediterranean region did during prehistory. By around 4000 BC, the island was populated by people with a Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

culture. This neolithic population had significant ancestry from the earliest farming communities in Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, indicating that a major migration accompanied farming. The beginning of the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

and the Bell Beaker culture

The Bell Beaker culture, also known as the Bell Beaker complex or Bell Beaker phenomenon, is an archaeological culture named after the inverted-bell beaker drinking vessel used at the beginning of the European Bronze Age, arising from around ...

was marked by an even greater population turnover, this time displacing more than 90% of Britain's neolithic ancestry in the process. This is documented by recent ancient DNA studies which demonstrate that the immigrants had large amounts of Bronze-Age Eurasian Steppe ancestry

In archaeogenetics, the term Western Steppe Herders (WSH), or Western Steppe Pastoralists, is the name given to a distinct ancestral component first identified in individuals from the Chalcolithic steppe around the start of the 5th millennium B ...

, associated with the spread of Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia (e. ...

and the Yamnaya culture

The Yamnaya ( ) or Yamna culture ( ), also known as the Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, is a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archaeological culture of the region between the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Ural rivers (the Pontic–C ...

.

No written language of the pre-Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

inhabitants of Britain is known; therefore, the history, culture and way of life of pre-Roman Britain are known mainly through archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

finds. Archaeological evidence demonstrates that ancient Britons

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs modern British citizenship and nationality, w ...

were involved in extensive maritime trade and cultural links with the rest of Europe from the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

onwards, especially by exporting tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

that was in abundant supply. Although the main evidence for the period is archaeological, available genetic evidence is increasing, and views of British prehistory are evolving accordingly. Julius Caesar's first invasion of Britain in 55 BC is regarded as the start of recorded protohistory

Protohistory is the period between prehistory and written history, during which a culture or civilization has not yet developed writing, but other cultures that have developed writing have noted the existence of those pre-literate groups in the ...

although some historical information is available from before then.

Stone Age

Palaeolithic

Palaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

(Old Stone Age) Britain is the period of the earliest known occupation of Britain by humans. This huge period saw many changes in the environment, encompassing several glacial

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

and interglacial

An interglacial period (or alternatively interglacial, interglaciation) is a geological interval of warmer global average temperature lasting thousands of years that separates consecutive glacial periods within an ice age. The current Holocene i ...

episodes greatly affecting human settlement in the region. Providing dating for this distant period is difficult and contentious. The inhabitants of the region at this time were bands of hunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived Lifestyle, lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, esp ...

s who roamed Northern Europe following herds of animals, or who supported themselves by fishing.

First trace of human settlement at Happisburgh

There is evidence from animal bones andflint tools

Stone tools have been used throughout human history but are most closely associated with prehistory, prehistoric cultures and in particular those of the Stone Age. Stone tools may be made of either ground stone or Lithic reduction, knapped stone, ...

found in coastal deposits near Happisburgh

Happisburgh () is a village civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. The village is on the coast, to the east of a north–south road, the B1159 from Bacton on the coast to Stalham. It is a nucleated village. The nearest substantial ...

in Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

that early humans

''Homo'' () is a genus of great ape (family Hominidae) that emerged from the genus ''Australopithecus'' and encompasses only a single extant species, ''Homo sapiens'' (modern humans), along with a number of extinct species (collectively called ...

were present in Britain over 800,000 years ago. The archaeological site at Happisburgh lies underneath glacial sediments from the Anglian glaciation of 450,000 years ago.''Britain One Million Years of the Human Story'' by Rob Dinnis & Chris Stringer published by the Natural History Museum, London 2013. Reprinted with updates 2023. ISBN 978 0 565 09337 2 Paleo magnetic analysis shows that the sediments in which the stone tools were found have a reversed polarity- which means they are at least 780,000 years old. Plant remains as well as the presence of extinct species of vole, mammoth, red deer, horse and elk indicate a date between 780,000 and 990,000 years old. The evidence is that the early humans were there towards the end of an interglacial during that date range. There are two candidate interglacials - one between 970,000 and 935,000 years ago and the second from 865,000 and 815,000 years ago. Numerous footprints dating to more than 800,000 years ago were found on the beach at Happisburgh in 2013 of a mixed group of adult males, females and children. However there are no human fossils found. ''Homo antecessor

''Homo antecessor'' (Latin "pioneer man") is an extinct species of archaic human recorded in the Spanish Archaeological Site of Atapuerca, Sierra de Atapuerca, a productive archaeological site, from 1.2 to 0.8 million years ago during the Early ...

'' is the most likely candidate species of ancient human as there are remains of roughly the same age at Gran Dolina at Atapuerca. ''Homo antecessor'' lived before the ancestors of Neanderthals split from the ancestors of ''Homo sapiens'' 600,000 years ago.

Summer temperatures at Happisburgh were an average of 16-17 degrees C (60.8-61.6 degrees F) and average winter temperatures were slightly colder than present day temperatures, around freezing point or just below. Conditions were comparable to present-day southern Scandinavia. It is not established how early humans at Happisburgh would have been able to deal with the cold winters. It is possible that they migrated southwards during the winter but the distances are large. No evidence has been found for the use of fire during that period.

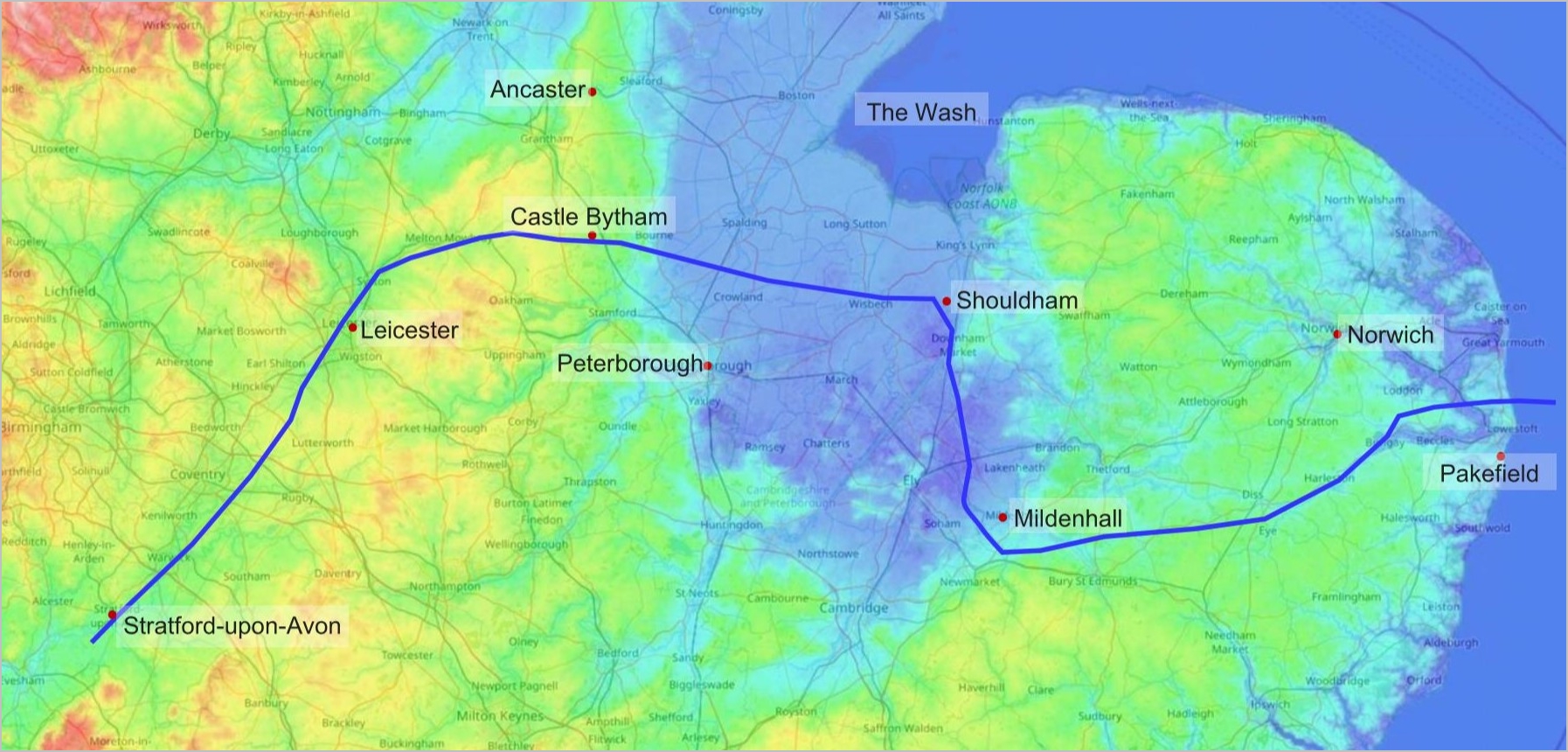

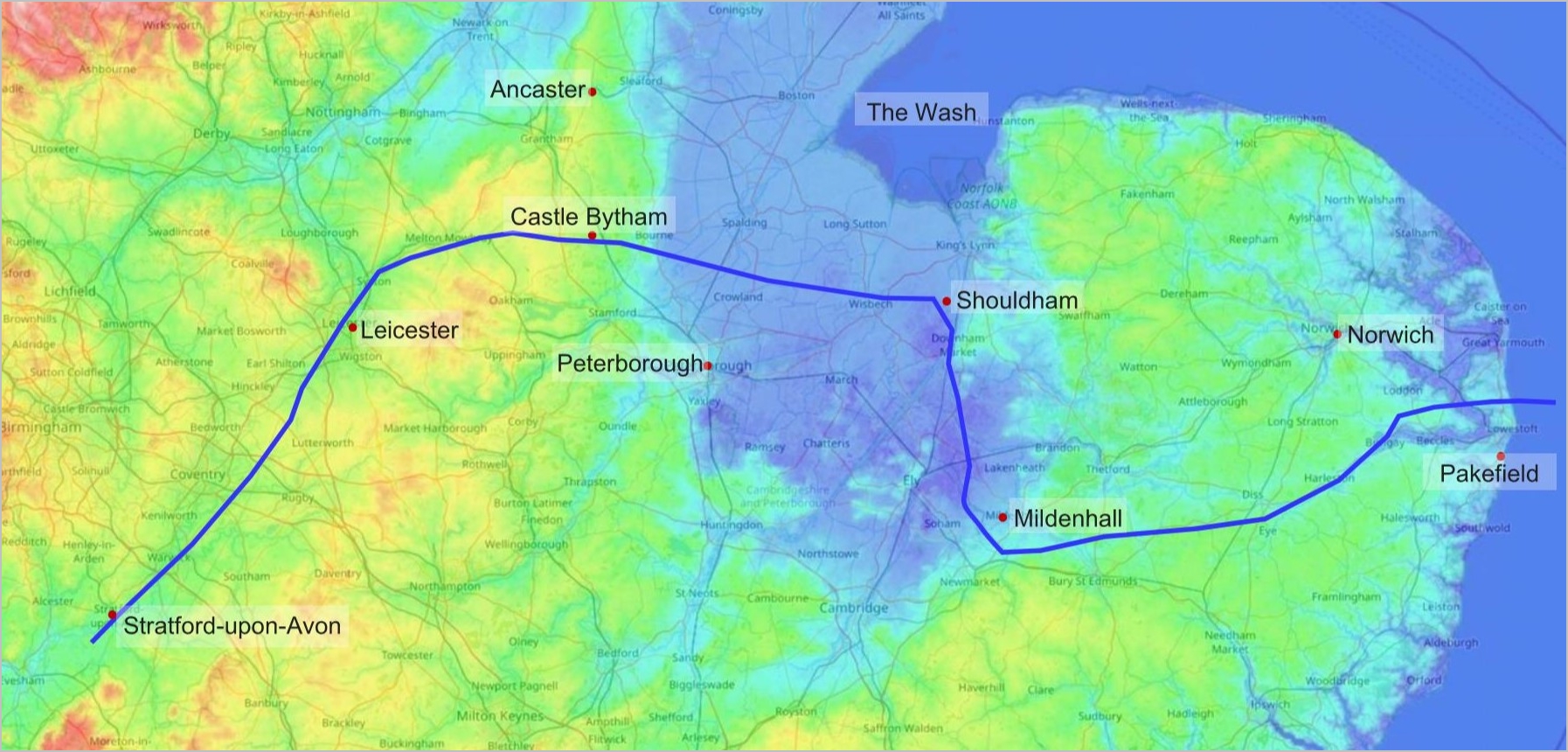

At this time, Britain was a peninsula of Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, connected by a chalk ridge running across to northern France and the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

did not yet exist. There were two main rivers in eastern Britain: the Bytham River, flowing east from the English Midlands and then across the north of East Anglia, and the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

, which then flowed further north than today. Early humans may have followed the Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

and thence around the huge north-facing bay into which the Thames and Bytham also flowed. Humans in Happisburgh were in a great valley downstream from the joining of the two great rivers.

Reconstructing this ancient environment has provided clues to the route first visitors took to arrive at what was then a peninsula of the Eurasian continent. Archaeologists have found a string of early sites located close to the route of a now lost watercourse named the Bytham River which indicate that it was exploited as the earliest route west into Britain.

Settlement at Pakefield

Chronologically, the next evidence of human occupation is at Pakefield on the outskirts ofLowestoft

Lowestoft ( ) is a coastal town and civil parish in the East Suffolk (district), East Suffolk district of Suffolk, England.OS Explorer Map OL40: The Broads: (1:25 000) : . As the List of extreme points of the United Kingdom, most easterly UK se ...

in Suffolk

Suffolk ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Norfolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Essex to the south, and Cambridgeshire to the west. Ipswich is the largest settlement and the county ...

48 kilometres south of Happisburgh. They were in the lower Bytham river, and not the Thames which had now moved further south. Pakefield had mild winters and warm summers with average July temperatures of between 18 and 23 degrees C (64.4 and 73.4 degrees F). There were wet winters and drier summers. Animal bones found in the area include those of rhinos, hippos, extinct elephants, giant deer, hyaenas, lions, and sabre-toothed cats.

Sites such as

Sites such as Boxgrove

Boxgrove is a village, parish, ecclesiastical parish and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Chichester (district), Chichester District of the English county of West Sussex, about north east of the city of Chichester. The village is ...

in Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

illustrate the later arrival in the archaeological record of an archaic ''Homo

''Homo'' () is a genus of great ape (family Hominidae) that emerged from the genus ''Australopithecus'' and encompasses only a single extant species, ''Homo sapiens'' (modern humans), along with a number of extinct species (collectively called ...

'' species called ''Homo heidelbergensis

''Homo heidelbergensis'' is a species of archaic human from the Middle Pleistocene of Europe and Africa, as well as potentially Asia depending on the taxonomic convention used. The species-level classification of ''Homo'' during the Middle Pleis ...

'' around 500,000 years ago. These early peoples made Acheulean

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated with ''Homo ...

flint tools (hand axes) and hunted the large native mammals of the period. One hypothesis is that they drove elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

s, rhinoceros

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

es and hippopotamus

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Sahar ...

es over the tops of cliffs or into bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and musk ...

s to more easily kill them.

The extreme cold of the following Anglian Stage

The Anglian Stage is the name used in the British Isles for a middle Pleistocene glaciation. It precedes the Hoxnian Stage and follows the Cromerian Stage in the British Isles. It correlates to Marine Isotope Stage 12 (MIS 12), which started ab ...

is likely to have driven humans out of Britain altogether and the region does not appear to have been occupied again until the ice receded during the Hoxnian Stage. This warmer time period lasted from around 424,000 until 374,000 years ago and saw the Clactonian

The Clactonian is the name given by archaeologists to an industry of European flint tool manufacture that dates to the early part of the Hoxnian Interglacial (corresponding to the global Marine Isotope Stage 11 and the continental Holstein Int ...

flint tool industry

Industry may refer to:

Economics

* Industry (economics), a generally categorized branch of economic activity

* Industry (manufacturing), a specific branch of economic activity, typically in factories with machinery

* The wider industrial sector ...

develop at sites such as Swanscombe

Swanscombe /ˈswɔnzkəm/ is a town in the Borough of Dartford in Kent, England, and the civil parish of Swanscombe and Greenhithe. It is 4.4 miles west of Gravesend and 4.8 miles east of Dartford.

History

Prehistory

Bone fragments and to ...

in Kent. The period has produced a rich and widespread distribution of sites by Palaeolithic standards, although uncertainty over the relationship between the Clactonian and Acheulean industries is still unresolved.

Britain was populated only intermittently, and even during periods of occupation may have reproduced below replacement level and needed immigration from elsewhere to maintain numbers. According to Paul Pettitt and Mark White:

:The British Lower Palaeolithic

The Lower Paleolithic (or Lower Palaeolithic) is the earliest subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. It spans the time from around 3.3 million years ago when the first evidence for stone tool production and use by hominins appears ...

(and equally that of much of northern Europe) is thus a long record of abandonment and colonisation, and a very short record of residency. The sad but inevitable conclusion of this must be that Britain has little role to play in any understanding of long-term human evolution and its cultural history is largely a broken record dependent on external introductions and insular developments that ultimately lead nowhere. Britain, therefore, was an island of the living dead.

This period also saw Levallois flint tools introduced, possibly by humans arriving from Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

. However, finds from Swanscombe and Botany Pit in Purfleet

Purfleet-on-Thames is a town in the Thurrock unitary authority, Essex, England.

It is bordered by the A13 road to the north and the River Thames to the south and is within the easternmost part of the M25 motorway but just outside the Greater ...

support Levallois technology being a European rather than African introduction. The more advanced flint technology permitted more efficient hunting and therefore made Britain a more worthwhile place to remain until the following period of cooling known as the Wolstonian Stage

The Wolstonian Stage is a middle Pleistocene stage of the geological history of Earth from approximately 374,000 until 130,000 years ago. It precedes the Last Interglacial (also called the Eemian Stage) and follows the Hoxnian Stage in the Briti ...

, 352,000–130,000 years ago. Britain first became an island about 350,000 years ago.

230,000 years BP the landscape was reachable and Early Neanderthal remains discovered at the Pontnewydd Cave in Wales have been dated to 230,000 BP, and are the most north westerly Neanderthal remains found anywhere in the world.

The next glaciation closed in and by about 180,000 years ago Britain no longer had humans.Ancestors - A Prehistory of Britain in Seven Burials. Audiobook by Alice Roberts 2021 About 130,000 years ago there was an interglacial period even warmer than today, which lasted 15,000 years. There were lions, elephants hyenas and hippos as well as deer. There were no humans. Possibly humans were too sparse at that time. Until c.60,000 years ago there is no evidence of human occupation in Britain, probably due to inhospitable cold in some periods, Britain being cut off as an island in others, and the neighbouring areas of north-west Europe being unoccupied by hominins at times when Britain was both accessible and hospitable.

This period is often divided into three subperiods: the Early Upper Palaeolithic (before the main glacial period), the Middle-Upper Palaeolithic (the main glacial period) and the Late Upper Palaeolithic (after the main glacial period). There was limited Neanderthal occupation of Britain in

This period is often divided into three subperiods: the Early Upper Palaeolithic (before the main glacial period), the Middle-Upper Palaeolithic (the main glacial period) and the Late Upper Palaeolithic (after the main glacial period). There was limited Neanderthal occupation of Britain in marine isotope stage

Marine isotope stages (MIS), marine oxygen-isotope stages, or oxygen isotope stages (OIS), are alternating warm and cool periods in the Earth's paleoclimate, deduced from Oxygen isotope ratio cycle, oxygen isotope data derived from deep sea core ...

3 between about 60,000 and 42,000 years BP. Britain had its own unique variety of late Neanderthal handaxe, the bout-coupé, so seasonal migration between Britain and the continent is unlikely, but the main occupation may have been in the now submerged area of Doggerland

Doggerland was a large area of land in Northern Europe, now submerged beneath the southern North Sea. This region was repeatedly exposed at various times during the Pleistocene epoch due to the lowering of sea levels during glacial periods. Howe ...

, with summer migrations to Britain in warmer periods. La Cotte de St Brelade in Jersey

Jersey ( ; ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey, is an autonomous and self-governing island territory of the British Islands. Although as a British Crown Dependency it is not a sovereign state, it has its own distinguishing civil and gov ...

is the only site in the British Isles to have produced late Neanderthal fossils.

The earliest evidence for modern humans in North West Europe is a jawbone discovered in England at Kents Cavern

Kents Cavern is a cave system in Torquay, Devon, England. It is notable both for its archaeological and geological features (as a karst feature in the Devonian limestone). The cave system is open to the public and has been a geological Site of S ...

in 1927, which was re-dated in 2011 to between 41,000 and 44,000 years old. The most famous example from this period is the burial of the "Red Lady of Paviland

The Red "Lady" of Paviland () is an Upper Paleolithic partial male skeleton dyed in red ochre and buried in Wales 33,000 BP (approximately 31,000 BCE). The bones were discovered in 1823 by William Buckland in an archaeological dig at Goat's Hol ...

" (actually now known to be a man) in modern-day coastal South Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, which was dated in 2009 to be 33,000 years old. The distribution of finds shows that humans in this period preferred the uplands of Wales and northern and western England to the flatter areas of eastern England. Their stone tools are similar to those of the same age found in Belgium and far north-east France, and very different from those in north-west France. At a time when Britain was not an island, hunter gatherers may have followed migrating herds of reindeer from Belgium and north-east France across the giant Channel River.

The climatic deterioration which culminated in the Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Last Glacial Coldest Period, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period where ice sheets were at their greatest extent between 26,000 and 20,000 years ago.

Ice sheets covered m ...

, between about 26,500 and 19,000–20,000 years ago, drove humans out of Britain, and there is no evidence of occupation for around 18,000 years after c.33,000 years BP. Sites such as Cathole Cave in Swansea County dated at 14,500BP, Creswell Crags

Creswell Crags is an enclosed limestone gorge on the border between Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, England, near the villages of Creswell and Whitwell. The cliffs in the ravine contain several caves that were occupied during the last ice age ...

on the border between Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire at 12,800BP and Gough's Cave in Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

12,000 years BP, provide evidence suggesting that humans returned to Britain towards the end of this ice age during a warm period from 14,700 to 12,900 years ago (the Bølling-Allerød interstadial known as the ''Windermere Interstadial'' in Britain), although further extremes of cold right before the final thaw may have caused them to leave again and then return repeatedly. The environment during this ice age period would have been largely treeless tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

, eventually replaced by a gradually warmer climate, perhaps reaching 17 degrees Celsius

The degree Celsius is the unit of temperature on the Celsius temperature scale "Celsius temperature scale, also called centigrade temperature scale, scale based on 0 ° for the melting point of water and 100 ° for the boiling point ...

(62.6 Fahrenheit

The Fahrenheit scale () is a scale of temperature, temperature scale based on one proposed in 1724 by the German-Polish physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686–1736). It uses the degree Fahrenheit (symbol: °F) as the unit. Several accou ...

) in summer, encouraging the expansion of birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech- oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 3 ...

trees as well as shrub and grasses.

The first distinct culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

of the Upper Palaeolithic in Britain is what archaeologists call the Creswellian industry, with leaf-shaped points probably used as arrowheads. It produced more refined flint tools but also made use of bone, antler, shell, amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin. Examples of it have been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since the Neolithic times, and worked as a gemstone since antiquity."Amber" (2004). In Maxine N. Lurie and Marc Mappen (eds.) ''Encyclopedia ...

, animal teeth, and mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

ivory. These were fashioned into tools but also jewellery and rods of uncertain purpose. Flint seems to have been brought into areas with limited local resources; the stone tools found in the caves of Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

, such as Kent's Cavern, seem to have been sourced from Salisbury Plain

Salisbury Plain is a chalk plateau in southern England covering . It is part of a system of chalk downlands throughout eastern and southern England formed by the rocks of the Chalk Group and largely lies within the county of Wiltshire, but st ...

, 100 miles (161 km) east. This is interpreted as meaning that the early inhabitants of Britain were highly mobile, roaming over wide distances and carrying 'toolkits' of flint blades with them rather than heavy, unworked flint nodules, or else improvising tools extemporaneously. The possibility that groups also travelled to meet and exchange goods or sent out dedicated expeditions to source flint has also been suggested.

The dominant food species were equine

Equinae is a subfamily of the family Equidae, known from the Hemingfordian stage of the Early Miocene (16 million years ago) onwards. They originated in North America, before dispersing to every continent except Australia and Antarctica. They are ...

s ('' Equus ferus'') and red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or Hart (deer), hart, and a female is called a doe or hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Ir ...

(''Cervus elaphus''), although other mammals ranging from hares

Hares and jackrabbits are mammals belonging to the genus ''Lepus''. They are herbivores and live solitarily or in pairs. They nest in slight depressions called forms, and their young are able to fend for themselves shortly after birth. The genu ...

to mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

were also hunted, including rhino and hyena. From the limited evidence available, burial seemed to involve skinning and dismembering a corpse with the bones placed in caves. This suggests a practice of excarnation

In archaeology and anthropology, the term excarnation (also known as defleshing) refers to the practice of removing the flesh and organs of the dead before burial. Excarnation may be achieved through natural means, such as leaving a dead body exp ...

and secondary burial, and possibly some form of ritual cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is also well document ...

. Artistic expression seems to have been mostly limited to engraved bone, although the cave art

In archaeology, cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric art, prehistoric origin. These paintings were often c ...

at Creswell Crags

Creswell Crags is an enclosed limestone gorge on the border between Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, England, near the villages of Creswell and Whitwell. The cliffs in the ravine contain several caves that were occupied during the last ice age ...

and Mendip caves are notable exceptions.

Between about 12,890 and 11,650 years ago Britain returned to glacial conditions during the Younger Dryas

The Younger Dryas (YD, Greenland Stadial GS-1) was a period in Earth's geologic history that occurred circa 12,900 to 11,700 years Before Present (BP). It is primarily known for the sudden or "abrupt" cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, when the ...

, and may have been unoccupied for periods.

Mesolithic

(c. 9,000 to 4,300 BC) The Younger Dryas was followed by the

The Younger Dryas was followed by the Holocene

The Holocene () is the current geologic time scale, geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene to ...

, which began around 9,700 BC,Walker, M., Johnsen, S., Rasmussen, S. O., Popp, T., Steffensen, J.-P., Gibbard, P., Hoek, W., Lowe, J., Andrews, J., Bjo¨ rck, S., Cwynar, L. C., Hughen, K., Kershaw, P., Kromer, B., Litt, T., Lowe, D. J., Nakagawa, T., Newnham, R., and Schwander, J. 2009"Formal definition and dating of the GSSP (Global Stratotype Section and Point) for the base of the Holocene using the Greenland NGRIP ice core, and selected auxiliary records"

''J. Quaternary Sci.'', Vol. 24 pp. 3–17. . and continues to the present. There was then limited occupation by

Ahrensburgian

The Ahrensburg culture or Ahrensburgian (c. 12,900 to 11,700 BP) was a late Upper Paleolithic nomadic hunter culture (or technocomplex) in north-central Europe during the Younger Dryas, the last spell of cold at the end of the Weichsel glaciati ...

hunter gatherers, but this came to an end when there was a final downturn in temperature which lasted from around 9,400 to 9,200 BC. Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Ancient Greek language, Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic i ...

people occupied Britain by around 9,000 BC, and it has been occupied ever since. By 8000 BC temperatures were higher than today, and birch woodlands spread rapidly, but there was a cold spell around 6,200 BC which lasted about 150 years. The plains of Doggerland

Doggerland was a large area of land in Northern Europe, now submerged beneath the southern North Sea. This region was repeatedly exposed at various times during the Pleistocene epoch due to the lowering of sea levels during glacial periods. Howe ...

were thought to have finally been submerged around 6500 to 6000 BC, but recent evidence suggests that the bridge may have lasted until between 5800 and 5400 BC, and possibly as late as 3800 BC.

The warmer climate changed the arctic environment to one of pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae.

''World Flora Online'' accepts 134 species-rank taxa (119 species and 15 nothospecies) of pines as cu ...

, birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech- oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 3 ...

and alder

Alders are trees of the genus ''Alnus'' in the birch family Betulaceae. The genus includes about 35 species of monoecious trees and shrubs, a few reaching a large size, distributed throughout the north temperate zone with a few species ex ...

forest; this less open landscape was less conducive to the large herds of reindeer

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, taiga, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only re ...

and wild horse

The wild horse (''Equus ferus'') is a species of the genus Equus (genus), ''Equus'', which includes as subspecies the modern domestication of the horse, domesticated horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') as well as the Endangered species, endangered ...

that had previously sustained humans. Those animals were replaced in people's diets by pig and less social animals such as elk

The elk (: ''elk'' or ''elks''; ''Cervus canadensis'') or wapiti, is the second largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. ...

, red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or Hart (deer), hart, and a female is called a doe or hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Ir ...

, roe deer, wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a Suidae, suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The speci ...

and aurochs

The aurochs (''Bos primigenius''; or ; pl.: aurochs or aurochsen) is an extinct species of Bovini, bovine, considered to be the wild ancestor of modern domestic cattle. With a shoulder height of up to in bulls and in cows, it was one of t ...

(wild cattle), which would have required different hunting techniques. Tools changed to incorporate barbs which could snag the flesh of an animal, making it harder for it to escape alive. Tiny microlith

A microlith is a small Rock (geology), stone tool usually made of flint or chert and typically a centimetre or so in length and half a centimetre wide. They were made by humans from around 60,000 years ago, across Europe, Africa, Asia and Austral ...

s were developed for hafting onto harpoons and spears. Woodworking tools such as adze

An adze () or adz is an ancient and versatile cutting tool similar to an axe but with the cutting edge perpendicular to the handle rather than parallel. Adzes have been used since the Stone Age. They are used for smoothing or carving wood in ha ...

s appear in the archaeological record, although some flint blade types remained similar to their Palaeolithic predecessors. The dog

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the gray wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it was selectively bred from a population of wolves during the Late Pleistocene by hunter-gatherers. ...

was domesticated because of its benefits during hunting, and the wetland environments created by the warmer weather would have been a rich source of fish and game. Wheat of a variety grown in the Middle East was present on the Isle of Wight at the Bouldnor Cliff Mesolithic Village

Bouldnor Cliff is a submerged prehistoric settlement site in the Solent. The site dates from the Mesolithic era and is in approximately of water just offshore of the village of Bouldnor on the Isle of Wight in the United Kingdom. The preserv ...

dating from about 6,000 BC.

It is likely that these environmental changes were accompanied by social changes. Humans spread and reached the far north of Scotland during this period. Sites from the British Mesolithic include the Mendips,

It is likely that these environmental changes were accompanied by social changes. Humans spread and reached the far north of Scotland during this period. Sites from the British Mesolithic include the Mendips, Star Carr

Star Carr is a Mesolithic archaeological site in North Yorkshire, England. It is around five miles () south of Scarborough.

It is generally regarded as the most important and informative Mesolithic site in Great Britain. It is as important to ...

in Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

and Oronsay in the Inner Hebrides

The Inner Hebrides ( ; ) is an archipelago off the west coast of mainland Scotland, to the south east of the Outer Hebrides. Together these two island chains form the Hebrides, which experience a mild oceanic climate. The Inner Hebrides compri ...

. Excavations at Howick in Northumberland

Northumberland ( ) is a ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North East England, on the Anglo-Scottish border, border with Scotland. It is bordered by the North Sea to the east, Tyne and Wear and County Durham to the south, Cumb ...

uncovered evidence of a large circular building dating to c. 7600 BC which is interpreted as a dwelling. further example

has also been identified at

Deepcar

Deepcar is a village located on the eastern fringe of the town of Stocksbridge, South Yorkshire, England. It is in the electoral ward of Stocksbridge and Upper Don, 10 miles (16 km) south-west of Barnsley town centre and approximately nor ...

in Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, situated south of Leeds and east of Manchester. The city is the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire and some of its so ...

, and a building dating to c. 8500 BC was discovered at the Star Carr site. A group of 25 pits, aligned with a watercourse, laid out in straight lines, up to 500 metres long, has been found at Linmere, Bedfordshire. The older view of Mesolithic Britons

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs modern British citizenship and nationality, w ...

as nomadic is now being replaced with a more complex picture of seasonal occupation or, in some cases, permanent occupation. Travel distances seem to have become shorter, typically with movement between high and low ground.

In 1997, DNA analysis

Genetic testing, also known as DNA testing, is used to identify changes in DNA sequence or chromosome structure. Genetic testing can also include measuring the results of genetic changes, such as RNA analysis as an output of gene expression, or ...

was carried out on a tooth of Cheddar Man

Cheddar Man is a human male skeleton found in Gough's Cave in Cheddar Gorge, Somerset, England. The skeletal remains date to around the mid-to-late 9th millennium BC, corresponding to the Mesolithic period, and it appears that he died a viole ...

, human remains dated to c. 7150 BC found in Gough's Cave at Cheddar Gorge

Cheddar Gorge is a limestone gorge in the Mendip Hills, near the village of Cheddar, Somerset, England. The gorge is the site of the Cheddar show caves, where Britain's oldest complete human skeleton, Cheddar Man, estimated to be 9,000 years ...

. His mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

(mtDNA) belonged to Haplogroup U5. Within modern European populations, U5 is now concentrated in North-East Europe, among members of the Sami people

Acronyms

* SAMI, ''Synchronized Accessible Media Interchange'', a closed-captioning format developed by Microsoft

* Saudi Arabian Military Industries, a government-owned defence company

* South African Malaria Initiative, a virtual expertise ...

, Finns

Finns or Finnish people (, ) are a Baltic Finns, Baltic Finnic ethnic group native to Finland. Finns are traditionally divided into smaller regional groups that span several countries adjacent to Finland, both those who are native to these cou ...

, and Estonians

Estonians or Estonian people () are a Finnic ethnic group native to the Baltic Sea region in Northern Europe, primarily their nation state of Estonia.

Estonians primarily speak the Estonian language, a language closely related to other Finni ...

. This distribution and the age of the haplogroup indicate that individuals belonging to U5 were among the first people to resettle Northern Europe

The northern region of Europe has several definitions. A restrictive definition may describe northern Europe as being roughly north of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, which is about 54th parallel north, 54°N, or may be based on other ge ...

, following the retreat of ice sheets from the Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Last Glacial Coldest Period, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period where ice sheets were at their greatest extent between 26,000 and 20,000 years ago.

Ice sheets covered m ...

, about 10,000 years ago. It has also been found in other Mesolithic remains in Germany, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Sweden, France and Spain. Members of U5 may have been one of the most common haplogroups in Europe, before the spread of agriculture from the Middle East.

Though the Mesolithic environment was bounteous, the rising population and the ancient Britons' success in exploiting it eventually led to local exhaustion of many natural resources. The remains of a Mesolithic elk found caught in a bog at Poulton-le-Fylde

Poulton-le-Fylde (), commonly shortened to Poulton, is a market town in Lancashire, England, situated on the coastal plain called the Fylde. In the 2021 United Kingdom census, it had a population of 18,115.

There is evidence of human habitatio ...

in Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated ''Lancs'') is a ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Cumbria to the north, North Yorkshire and West Yorkshire to the east, Greater Manchester and Merseyside to the south, and the Irish Sea to ...

show that it had been wounded by hunters and escaped on three occasions, indicating hunting during the Mesolithic. A few Neolithic monuments overlie Mesolithic sites but little continuity can be demonstrated.

Farming of crops and domestic animals was adopted

Adoption is a process whereby a person assumes the parenting of another, usually a child, from that person's biological or legal parent or parents. Legal adoptions permanently transfer all rights and responsibilities, along with filiation, from ...

in Britain around 4500 BC, at least partly because of the need for reliable food sources.

The climate had been warming since the later Mesolithic and continued to improve, replacing the earlier pine forests with woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with woody plants (trees and shrubs), or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the '' plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunli ...

.

Neolithic

(c. 4,300 to 2,000 BC) The Neolithic was the period of domestication of plants and animals, but the arrival of a Neolithic package of farming and a sedentary lifestyle is increasingly giving way to a more complex view of the changes and continuities in practices that can be observed from the Mesolithic period onwards. For example, the development of Neolithic monumental architecture, apparently venerating the dead, may represent more comprehensive social and ideological changes involving new interpretations of time, ancestry, community and identity.

In any case, the

The Neolithic was the period of domestication of plants and animals, but the arrival of a Neolithic package of farming and a sedentary lifestyle is increasingly giving way to a more complex view of the changes and continuities in practices that can be observed from the Mesolithic period onwards. For example, the development of Neolithic monumental architecture, apparently venerating the dead, may represent more comprehensive social and ideological changes involving new interpretations of time, ancestry, community and identity.

In any case, the Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, also known as the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period in Afro-Eurasia from a lifestyle of hunter-gatherer, hunting and gathering to one of a ...

, as it is called, introduced a more settled way of life and ultimately led to societies becoming divided into differing groups of farmers, artisans and leaders. Forest clearances were undertaken to provide room for cereal cultivation and animal herds. Native cattle and pigs were reared whilst sheep and goats were later introduced from the continent, as were the wheats and barleys grown in Britain. However, only a few actual settlement sites are known in Britain, unlike the continent. Cave occupation was common at this time.

The construction of the earliest earthwork sites in Britain began during the early Neolithic (c. 4400 BC – 3300 BC) in the form of long barrow

Long barrows are a style of monument constructed across Western Europe in the fifth and fourth millennia BCE, during the Early Neolithic period. Typically constructed from earth and either timber or stone, those using the latter material repres ...

s used for communal burial and the first causewayed enclosure

A causewayed enclosure is a type of large prehistoric Earthworks (Archaeology), earthwork common to the early Neolithic in Europe. It is an enclosure (archaeology), enclosure marked out by ditches and banks, with a number of causeways crossing ...

s, sites which have parallels on the continent. The former may be derived from the long house

A longhouse or long house is a type of long, proportionately narrow, single-room building for communal dwelling. It has been built in various parts of the world including Asia, Europe, and North America.

Many were built from lumber, timber and ...

, although no long house villages have been found in Britain — only individual examples. The stone-built houses on Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

— such as those at Skara Brae

Skara Brae is a stone-built Neolithic settlement, located on the Bay of Skaill in the parish of Sandwick, Orkney, Sandwick, on the west coast of Mainland, Orkney, Mainland, the largest island in the Orkney archipelago of Scotland. It consiste ...

— are, however, indicators of some nucleated settlement in Britain. Evidence of growing mastery over the environment is embodied in the Sweet Track

The Sweet Track is an ancient trackway, or causeway, in the Somerset Levels, England, named after its finder, Ray Sweet. It was built in 3807 BC (determined using dendrochronology – tree-ring dating) and is the second-oldest timber track ...

, a wooden trackway built to cross the marshes of the Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels are a coastal plain and wetland area of Somerset, England, running south from the Mendips to the Blackdown Hills.

The Somerset Levels have an area of about and are bisected by the Polden Hills; the areas to the south ...

and dated to 3807 BC. Leaf-shaped arrowheads, round-based pottery types and the beginnings of polished axe production are common indicators of the period. Evidence of the use of cow's milk comes from analysis of pottery contents found beside the Sweet Track. According to archaeological evidence from North Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

, salt was being produced by evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the Interface (chemistry), surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. A high concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evapora ...

of seawater around this time, enabling more effective preservation of meat.

Pollen analysis shows that woodland was decreasing and grassland increasing, with a major decline of elms. The winters were typically 3 degrees colder than at present but the summers some 2.5 degrees warmer.

The Middle Neolithic (c. 3300 BC – c. 2900 BC) saw the development of cursus

Cursuses are monumental Neolithic enclosure structures comprising parallel banks with external ditches or trenches. Found only in the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, relics within them indicate that they were built between 3400 and 3000 BC ...

monuments close to earlier barrows and the growth and abandonment of causewayed enclosures, as well as the building of impressive chamber tomb

A chamber tomb is a tomb for burial used in many different cultures. In the case of individual burials, the chamber is thought to signify a higher status for the interred than a simple grave (burial), grave. Built from Rock (geology), rock or som ...

s such as the Maeshowe

Maeshowe (or Maes Howe; ) is a Neolithic chambered cairn and passage grave situated on Mainland Orkney, Scotland. It was probably built around . In the archaeology of Scotland, it gives its name to the Maeshowe type of chambered cairn, which ...

types. The earliest stone circle

A stone circle is a ring of megalithic standing stones. Most are found in Northwestern Europe – especially Stone circles in the British Isles and Brittany – and typically date from the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, with most being ...

s and individual burials also appear.

Different pottery types, such as grooved ware, appear during the later Neolithic (c. 2900 BC – c. 2200 BC). In addition, new enclosures called

Different pottery types, such as grooved ware, appear during the later Neolithic (c. 2900 BC – c. 2200 BC). In addition, new enclosures called henge

A henge can be one of three related types of Neolithic Earthworks (archaeology), earthwork. The essential characteristic of all three is that they feature a ring-shaped bank and ditch, with the ditch inside the bank. Because the internal ditches ...

s were built, along with stone row

A stone row or stone alignment is a linear arrangement of megalithic standing stones set at intervals along a common axis or series of axes, usually dating from the later Neolithic or Bronze Age.Power (1997), p.23 Rows may be individual or groupe ...

s and the famous sites of Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric Megalith, megalithic structure on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, to ...

, Avebury

Avebury () is a Neolithic henge monument containing three stone circles, around the village of Avebury in Wiltshire, in south-west England. One of the best-known prehistoric sites in Britain, it contains the largest megalithic stone circle in ...

and Silbury Hill

Silbury Hill is a prehistoric artificial chalk mound near Avebury in the English county of Wiltshire. It is part of the Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites UNESCO World Heritage Site. At high, the hill is the second tallest prehistoric man ...

, which building reached its peak at this time. Industrial flint mining begins, such as that at Cissbury

Cissbury Ring is an biological Site of Special Scientific Interest north of Worthing in West Sussex. It is owned by the National Trust and is designated a Scheduled monument for its Neolithic flint mine and Iron Age hillfort.

Cissbury Ring is ...

and Grimes Graves

Grime's Graves is a large Neolithic flint mining complex in Norfolk, England. It lies north east from Brandon, Suffolk in the East of England. It was worked between 2600 and 2300 BCE, although production may have continued throug ...

, along with evidence of long-distance trade. Wooden tools and bowls were common, and bows were also constructed.

Changes in Neolithic culture could have been due to the mass migrations that occurred in that time. A 2017 study showed that British Neolithic farmers had formerly been genetically similar to contemporary populations in the Iberian peninsula, but from the Beaker culture

The Bell Beaker culture, also known as the Bell Beaker complex or Bell Beaker phenomenon, is an archaeological culture named after the inverted-bell Beaker (archaeology), beaker drinking vessel used at the beginning of the European Bronze Age, ...

period onwards, all British individuals had high proportions of Steppe ancestry

In archaeogenetics, the term Western Steppe Herders (WSH), or Western Steppe Pastoralists, is the name given to a distinct ancestral component first identified in individuals from the Chalcolithic steppe around the start of the 5th millennium B ...

and were genetically more similar to Beaker-associated people from the Lower Rhine area. The study argues that more than 90% of Britain's Neolithic gene pool was replaced with the coming of the Beaker people.''The Beaker Phenomenon And The Genomic Transformation Of Northwest Europe'' (2017)/ref> Analysis of the

mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

of modern European populations shows that over 80% are descended in the female line from European hunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived Lifestyle, lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, esp ...

s. Less than 20% are descended in the female line from Neolithic farmers from Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

and from subsequent migrations. The percentage in Britain is smaller at around 11%. Initial studies suggested that this situation is different with the paternal Y-chromosome

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes in therian mammals and other organisms. Along with the X chromosome, it is part of the XY sex-determination system, in which the Y is the sex-determining chromosome because the presence of the Y ...

DNA, varying from 10 to 100% across the country, being higher in the east. This was considered to show a large degree of population replacement during the Anglo-Saxon invasion and a nearly complete masking over of whatever population movement (or lack of it) went before in these two countries.''Molecular Biology and Evolution 19: 1008–1021''(full text) However, more widespread studies have suggested that there was less of a division between Western and Eastern parts of Britain with less Anglo-Saxon migration. Looking from a more Europe-wide standpoint, researchers at Stanford University have found overlapping cultural and genetic evidence that supports the theory that migration was at least partially responsible for the Neolithic Revolution in Northern Europe (including Britain). The science of genetic anthropology is changing very fast and a clear picture across the whole of human occupation of Britain has yet to emerge.

(full text)

Bronze Age

(Around 2200 to 750 BC) This period can be sub-divided into an earlier phase (2300 to 1200 BC) and a later one (1200 – 700 BC). Beaker pottery appears in England around 2475–2315 ''cal.'' BC along with flat axes and burial practices of

This period can be sub-divided into an earlier phase (2300 to 1200 BC) and a later one (1200 – 700 BC). Beaker pottery appears in England around 2475–2315 ''cal.'' BC along with flat axes and burial practices of inhumation

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and object ...

. With the revised Stonehenge chronology, this is after the Sarsen Circle and trilithons were erected at Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric Megalith, megalithic structure on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, to ...

. Several regions of origin have been postulated for the Beaker culture

The Bell Beaker culture, also known as the Bell Beaker complex or Bell Beaker phenomenon, is an archaeological culture named after the inverted-bell Beaker (archaeology), beaker drinking vessel used at the beginning of the European Bronze Age, ...

, notably the Iberian peninsula, the Netherlands and Central Europe. Beaker techniques brought to Britain the skill of refining metal

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electrical resistivity and conductivity, electricity and thermal conductivity, heat relatively well. These properties are all associated wit ...

. At first the users made items from copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

, but from around 2150 BCE smiths had discovered how to smelt bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

(which is much harder than copper) by mixing copper with a small amount of tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

. With this discovery, the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

arrived in Britain. Over the next thousand years, bronze gradually replaced stone as the main material for tool and weapon making.

Britain had large, easily accessible reserves of tin in the modern areas of Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

and Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

and thus tin mining

Mining is the Resource extraction, extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agriculture, agricultural processes, or feasib ...

began. By around 1600 BC the southwest of Britain was experiencing a trade boom as British tin was exported across Europe, evidence of ports being found in Southern Devon at Bantham and Mount Batten

Mount Batten is a 24-metre (80-ft) tall outcrop of rock on a 600-metre (2000-ft) peninsula in Plymouth Sound, Devon, England, named after Sir William Batten (c.1600-1667), MP and Surveyor of the Navy; it was previously known as How Stert.

Af ...

. Copper was mined at the Great Orme

The Great Orme () is a limestone headland on the north coast of Wales, north-west of the town of Llandudno. Referred to as ''Cyngreawdr Fynydd'' by the 12th-century poet Gwalchmai ap Meilyr, its English name derives from the Old Norse word for ...

in North Wales.

The Beaker people were also skilled at making ornaments from gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

, silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

and copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

, and examples of these have been found in graves of the wealthy Wessex culture of central southern Britain.

Early Bronze Age Britons buried their dead beneath earth mounds known as barrows, often with a beaker alongside the body. Later in the period, cremation

Cremation is a method of Disposal of human corpses, final disposition of a corpse through Combustion, burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India, Nepal, and ...

was adopted as a burial practice with cemeteries

A cemetery, burial ground, gravesite, graveyard, or a green space called a memorial park or memorial garden, is a place where the remains of many dead people are buried or otherwise entombed. The word ''cemetery'' (from Greek ) implies th ...

of urns

An urn is a vase, often with a cover, with a typically narrowed neck above a rounded body and a footed pedestal. Describing a vessel as an "urn", as opposed to a vase or other terms, generally reflects its use rather than any particular shape ...

containing cremated individuals appearing in the archaeological record, with deposition of metal objects such as daggers. People of this period were also largely responsible for building many famous prehistoric sites such as the later phases of Stonehenge