A mammal () is a

vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

animal of the

class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of

milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of lactating mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfeeding, breastfed human infants) before they are able to digestion, digest solid food. ...

-producing

mammary gland

A mammary gland is an exocrine gland that produces milk in humans and other mammals. Mammals get their name from the Latin word ''mamma'', "breast". The mammary glands are arranged in organs such as the breasts in primates (for example, human ...

s for feeding their young, a broad

neocortex

The neocortex, also called the neopallium, isocortex, or the six-layered cortex, is a set of layers of the mammalian cerebral cortex involved in higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, cognition, generation of motor commands, ...

region of the brain,

fur or

hair

Hair is a protein filament that grows from follicles found in the dermis. Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals.

The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick terminal and ...

, and three

middle ear bones. These characteristics distinguish them from

reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s and

bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s, from which their ancestors

diverged in the

Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

Period over 300 million years ago. Around 6,640

extant

Extant or Least-concern species, least concern is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Exta ...

species of mammals have been described and divided into 27

orders. The study of mammals is called

mammalogy.

The largest orders of mammals, by number of

species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

, are the

rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and Mandible, lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal specie ...

s,

bats, and

eulipotyphlans (including

hedgehogs,

moles and

shrew

Shrews ( family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, West Indies shrews, or marsupial shrews, which belong to dif ...

s). The next three are the

primate

Primates is an order (biology), order of mammals, which is further divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and Lorisidae, lorisids; and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include Tarsiiformes, tarsiers a ...

s (including

human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

s,

monkeys and

lemur

Lemurs ( ; from Latin ) are Strepsirrhini, wet-nosed primates of the Superfamily (biology), superfamily Lemuroidea ( ), divided into 8 Family (biology), families and consisting of 15 genera and around 100 existing species. They are Endemism, ...

s), the

even-toed ungulates (including

pigs,

camel

A camel (from and () from Ancient Semitic: ''gāmāl'') is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. Camels have long been domesticated and, as livestock, they provid ...

s, and

whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully Aquatic animal, aquatic placental mammal, placental marine mammals. As an informal and Colloquialism, colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea ...

s), and the

Carnivora (including

cats

The cat (''Felis catus''), also referred to as the domestic cat or house cat, is a small domesticated carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species of the family Felidae. Advances in archaeology and genetics have shown that the ...

,

dogs, and

seals).

Mammals are the only living members of

Synapsida; this

clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

, together with

Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

(reptiles and birds), constitutes the larger

Amniota clade. Early synapsids are referred to as "

pelycosaurs." The more advanced

therapsids

Therapsida is a clade comprising a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals and their ancestors and close relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including li ...

became dominant during the

Guadalupian

The Guadalupian is the second and middle Series (stratigraphy), series/Epoch (geology), epoch of the Permian. The Guadalupian was preceded by the Cisuralian and followed by the Lopingian. It is named after the Guadalupe Mountains of New Mexico an ...

. Mammals originated from

cynodonts, an advanced group of therapsids, during the Late

Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

to Early

Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

. Mammals achieved their modern diversity in the

Paleogene

The Paleogene Period ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Neogene Period Ma. It is the fir ...

and

Neogene

The Neogene ( ,) is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period million years ago. It is the second period of th ...

periods of the

Cenozoic era, after the

extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, and have been the

dominant terrestrial animal group from 66 million years ago to the present.

The basic mammalian body type is

quadrupedal, with most mammals using four

limbs for

terrestrial locomotion

Terrestrial locomotion has evolution, evolved as animals adapted from ecoregion#Marine, aquatic to ecoregion#Terrestrial, terrestrial environments. Animal locomotion, Locomotion on land raises different problems than that in water, with reduced f ...

; but in some, the limbs are adapted for life

at sea

A sea is a large body of salt water. There are particular seas and the sea. The sea commonly refers to the ocean, the interconnected body of seawaters that spans most of Earth. Particular seas are either marginal seas, second-order section ...

,

in the air

IN, In or in may refer to:

Dans

* India (country code IN)

* Indiana, United States (postal code IN)

* Ingolstadt, Germany (license plate code IN)

* In, Russia, a town in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast

Businesses and organizations

* Independen ...

,

in trees or

underground. The

bipeds

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an animal moves by means of its two rear (or lower) Limb (anatomy), limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from ...

have adapted to move using only the two lower limbs, while the rear limbs of

cetaceans

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

and the

sea cows are mere internal

vestiges. Mammals range in size from the

bumblebee bat to the

blue whale—possibly the largest animal to have ever lived. Maximum lifespan varies from two years for the shrew to 211 years for the

bowhead whale. All modern mammals give birth to live young, except the five species of

monotremes, which lay eggs. The most species-rich group is the

viviparous placental mammals, so named for the temporary organ (

placenta) used by offspring to draw nutrition from the mother during

gestation

Gestation is the period of development during the carrying of an embryo, and later fetus, inside viviparous animals (the embryo develops within the parent). It is typical for mammals, but also occurs for some non-mammals. Mammals during pregn ...

.

Most mammals are

intelligent, with some possessing large brains,

self-awareness, and

tool use. Mammals can communicate and vocalise in several ways, including the production of

ultrasound

Ultrasound is sound with frequency, frequencies greater than 20 Hertz, kilohertz. This frequency is the approximate upper audible hearing range, limit of human hearing in healthy young adults. The physical principles of acoustic waves apply ...

,

scent marking,

alarm signals,

singing

Singing is the art of creating music with the voice. It is the oldest form of musical expression, and the human voice can be considered the first musical instrument. The definition of singing varies across sources. Some sources define singi ...

,

echolocation; and, in the case of humans, complex

language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

. Mammals can organise themselves into

fission–fusion societies,

harems, and

hierarchies—but can also be solitary and

territorial. Most mammals are

polygynous, but some can be

monogamous or

polyandrous.

Domestication

Domestication is a multi-generational Mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship in which an animal species, such as humans or leafcutter ants, takes over control and care of another species, such as sheep or fungi, to obtain from them a st ...

of many types of mammals by humans played a major role in the

Neolithic Revolution, and resulted in

farming

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

replacing

hunting and gathering as the primary source of food for humans. This led to a major restructuring of human societies from nomadic to sedentary, with more co-operation among larger and larger groups, and ultimately the development of the first

civilisations. Domesticated mammals provided, and continue to provide, power for transport and agriculture, as well as food (

meat

Meat is animal Tissue (biology), tissue, often muscle, that is eaten as food. Humans have hunted and farmed other animals for meat since prehistory. The Neolithic Revolution allowed the domestication of vertebrates, including chickens, sheep, ...

and

dairy product

Dairy products or milk products are food products made from (or containing) milk. The most common dairy animals are cow, water buffalo, goat, nanny goat, and Sheep, ewe. Dairy products include common grocery store food around the world such as y ...

s),

fur, and

leather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning (leather), tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffal ...

. Mammals are also

hunted and raced for sport, kept as

pets and

working animals of various types, and are used as

model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

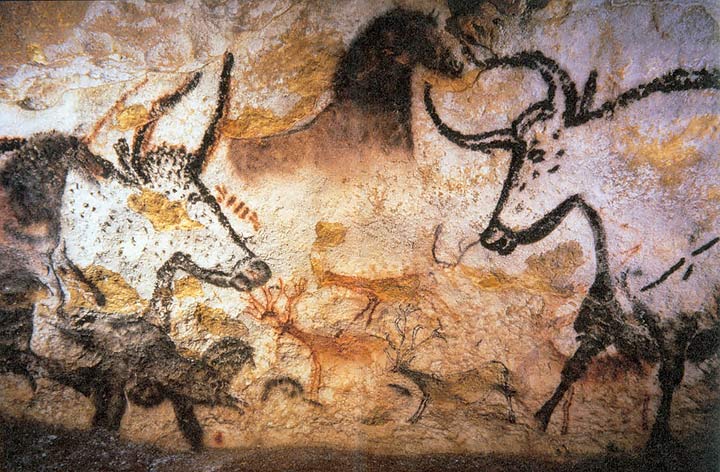

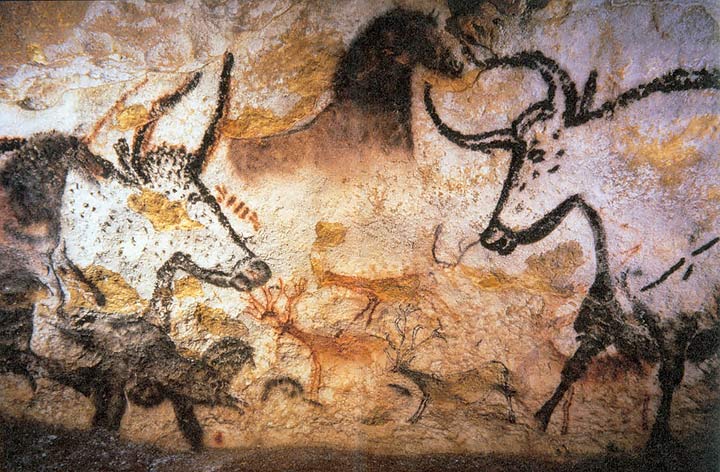

s in science. Mammals have been depicted in

art since

Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

times, and appear in literature, film, mythology, and religion. Decline in numbers and

extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

of many mammals is primarily driven by human

poaching

Poaching is the illegal hunting or capturing of wild animals, usually associated with land use rights.

Poaching was once performed by impoverished peasants for subsistence purposes and to supplement meager diets. It was set against the huntin ...

and

habitat destruction, primarily

deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal and destruction of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. Ab ...

.

Classification

Mammal classification has been through several revisions since

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

initially defined the class, and at present, no classification system is universally accepted. McKenna & Bell (1997) and Wilson & Reeder (2005) provide useful recent compendiums.

Simpson (1945)

provides

systematics

Systematics is the study of the diversification of living forms, both past and present, and the relationships among living things through time. Relationships are visualized as evolutionary trees (synonyms: phylogenetic trees, phylogenies). Phy ...

of mammal origins and relationships that had been taught universally until the end of the 20th century.

However, since 1945, a large amount of new and more detailed information has gradually been found: The

paleontological record has been recalibrated, and the intervening years have seen much debate and progress concerning the theoretical underpinnings of systematisation itself, partly through the new concept of

cladistics

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to Taxonomy (biology), biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesiz ...

. Though fieldwork and lab work progressively outdated Simpson's classification, it remains the closest thing to an official classification of mammals, despite its known issues.

Most mammals, including the six most species-rich orders, belong to the placental group. The three largest orders in numbers of species are

Rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and Mandible, lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal specie ...

ia:

mice

A mouse (: mice) is a small rodent. Characteristically, mice are known to have a pointed snout, small rounded ears, a body-length scaly tail, and a high breeding rate. The best known mouse species is the common house mouse (''Mus musculus' ...

,

rats,

porcupines,

beavers,

capybaras, and other gnawing mammals;

Chiroptera: bats; and

Eulipotyphla:

shrew

Shrews ( family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, West Indies shrews, or marsupial shrews, which belong to dif ...

s,

moles, and

solenodons. The next three biggest orders, depending on the

biological classification

In biology, taxonomy () is the scientific study of naming, defining ( circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxa (singular: taxon), and these groups are give ...

scheme used, are the

primate

Primates is an order (biology), order of mammals, which is further divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and Lorisidae, lorisids; and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include Tarsiiformes, tarsiers a ...

s:

apes,

monkeys, and

lemur

Lemurs ( ; from Latin ) are Strepsirrhini, wet-nosed primates of the Superfamily (biology), superfamily Lemuroidea ( ), divided into 8 Family (biology), families and consisting of 15 genera and around 100 existing species. They are Endemism, ...

s;

Cetartiodactyla:

whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully Aquatic animal, aquatic placental mammal, placental marine mammals. As an informal and Colloquialism, colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea ...

s and

even-toed ungulates; and

Carnivora which includes

cats,

dogs,

weasels,

bear

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family (biology), family Ursidae (). They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats ...

s,

seals, and allies.

According to ''

Mammal Species of the World'', 5,416 species were identified in 2006. These were grouped into 1,229

genera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

, 153

families and 29 orders.

In 2008, the

International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the stat ...

(IUCN) completed a five-year Global Mammal Assessment for its

IUCN Red List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is an inventory of the global conservation status and extinction risk of biological ...

, which counted 5,488 species. According to research published in the ''

Journal of Mammalogy'' in 2018, the number of recognised mammal species is 6,495, including 96 recently extinct.

Definitions

The word "

mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

" is modern, from the scientific name ''Mammalia'' coined by

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

in 1758, derived from the

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

''

mamma'' ("teat, pap"). In an influential 1988 paper, Timothy Rowe defined Mammalia

phylogenetically as the

crown group of mammals, the

clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

consisting of the

most recent common ancestor of living

monotremes (

echidnas and

platypuses) and

theria

Theria ( or ; ) is a scientific classification, subclass of mammals amongst the Theriiformes. Theria includes the eutherians (including the Placentalia, placental mammals) and the metatherians (including the marsupials) but excludes the egg-lay ...

ns (

marsupial

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a r ...

s and

placentals) and all descendants of that ancestor. Since this ancestor lived in the

Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

period, Rowe's definition excludes all animals from the earlier

Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

, despite the fact that Triassic fossils in the

Haramiyida have been referred to the Mammalia since the mid-19th century. If Mammalia is considered as the crown group, its origin can be roughly dated as the first known appearance of animals more closely related to some extant mammals than to others. ''

Ambondro'' is more closely related to monotremes than to therian mammals while ''

Amphilestes'' and ''

Amphitherium'' are more closely related to the therians; as fossils of all three genera are dated about in the

Middle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic is the second Epoch (geology), epoch of the Jurassic Period (geology), Period. It lasted from about 174.1 to 161.5 million years ago. Fossils of land-dwelling animals, such as dinosaurs, from the Middle Jurassic are relativel ...

, this is a reasonable estimate for the appearance of the crown group.

T. S. Kemp has provided a more traditional definition: "

Synapsids that possess a

dentary–

squamosal jaw articulation and

occlusion between upper and lower molars with a transverse component to the movement" or, equivalently in Kemp's view, the clade originating with the last common ancestor of ''

Sinoconodon'' and living mammals. The earliest-known synapsid satisfying Kemp's definitions is ''

Tikitherium'', dated , so the appearance of mammals in this broader sense can be given this

Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch (geology), epoch of the Triassic geologic time scale, Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between annum, Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch a ...

date. However, this animal may have actually evolved during the Neogene.

Molecular classification of placentals

As of the early 21st century, molecular studies based on

DNA analysis have suggested new relationships among mammal families. Most of these findings have been independently validated by

retrotransposon presence/absence data.

Classification systems based on molecular studies reveal three major groups or lineages of placentals—

Afrotheria,

Xenarthra

Xenarthra (; from Ancient Greek ξένος, xénos, "foreign, alien" + ἄρθρον, árthron, "joint") is a superorder and major clade of placental mammals native to the Americas. There are 31 living species: the anteaters, tree sloths, and ...

and

Boreoeutheria—which

diverged in the

Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

. The relationships between these three lineages is contentious, and all three possible hypotheses have been proposed with respect to which group is

basal. These hypotheses are

Atlantogenata (basal Boreoeutheria),

Epitheria (basal Xenarthra) and

Exafroplacentalia (basal Afrotheria).

Boreoeutheria in turn contains two major lineages—

Euarchontoglires and

Laurasiatheria.

Estimates for the divergence times between these three placental groups range from 105 to 120 million years ago, depending on the type of DNA used (such as

nuclear or

mitochondrial) and varying interpretations of

paleogeographic data.

[

Mammal phylogeny according to Álvarez-Carretero ''et al.'', 2022:

]

Evolution

Origins

Synapsida, a clade that contains mammals and their extinct relatives, originated during the Pennsylvanian subperiod (~323 million to ~300 million years ago), when they split from the reptile lineage. Crown group mammals evolved from earlier mammaliaforms during the Early Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (geology), Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic series (stratigraphy), Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic� ...

. The cladogram takes Mammalia to be the crown group.

Evolution from older amniotes

The first fully terrestrial

The first fully terrestrial vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s were amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

s. Like their amphibious early tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

predecessors, they had lungs and limbs. Amniotic eggs, however, have internal membranes that allow the developing embryo to breathe but keep water in. Hence, amniotes can lay eggs on dry land, while amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s generally need to lay their eggs in water.

The first amniotes apparently arose in the Pennsylvanian subperiod of the Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

. They descended from earlier reptiliomorph amphibious tetrapods,insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s and other invertebrates as well as fern

The ferns (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta) are a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. They differ from mosses by being vascular, i.e., having specialized tissue ...

s, moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular plant, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic phylum, division Bryophyta (, ) ''sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Wilhelm Philippe Schimper, Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryo ...

es and other plants. Within a few million years, two important amniote lineages became distinct: the synapsids, which would later include the common ancestor of the mammals; and the sauropsids, which now include turtle

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

s, lizard

Lizard is the common name used for all Squamata, squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most Island#Oceanic isla ...

s, snake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

s, crocodilian

Crocodilia () is an Order (biology), order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorp ...

s and dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s (including bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s). Synapsids have a single hole ( temporal fenestra) low on each side of the skull. Primitive synapsids included the largest and fiercest animals of the early Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

such as '' Dimetrodon''. Nonmammalian synapsids were traditionally—and incorrectly—called "mammal-like reptiles" or pelycosaurs; we now know they were neither reptiles nor part of reptile lineage.[

Therapsids, a group of synapsids, evolved in the Middle Permian, about 265 million years ago, and became the dominant land vertebrates.][ The therapsid lineage leading to mammals went through a series of stages, beginning with animals that were very similar to their early synapsid ancestors and ending with ]probainognathia

Probainognathia is one of the two major subgroups of the clade Eucynodontia, the other being Cynognathia. The earliest forms were carnivorous and insectivorous, though some groups eventually also evolved herbivorous diets. The earliest and most b ...

n cynodont

Cynodontia () is a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian (approximately 260 Megaannum, mya), and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Mammals are cynodonts, as are their extin ...

s, some of which could easily be mistaken for mammals. Those stages were characterised by:

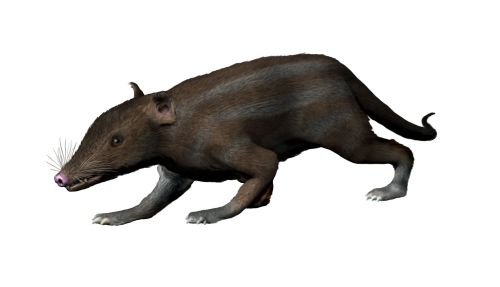

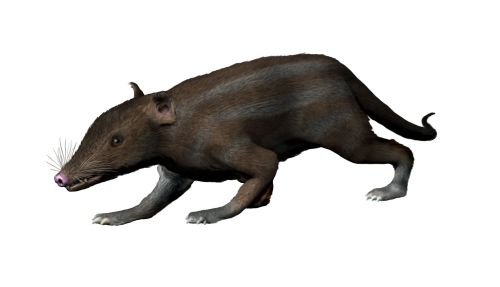

First mammals

The Permian–Triassic extinction event about 252 million years ago, which was a prolonged event due to the accumulation of several extinction pulses, ended the dominance of carnivorous therapsids. In the early Triassic, most medium to large land carnivore niches were taken over by archosaurs which, over an extended period (35 million years), came to include the crocodylomorphs, the pterosaurs and the dinosaurs; however, large cynodonts like '' Trucidocynodon'' and traversodontids still occupied large sized carnivorous and herbivorous niches respectively. By the Jurassic, the dinosaurs had come to dominate the large terrestrial herbivore niches as well.

The first mammals (in Kemp's sense) appeared in the Late Triassic epoch (about 225 million years ago), 40 million years after the first therapsids. They expanded out of their nocturnal insectivore

file:Common brown robberfly with prey.jpg, A Asilidae, robber fly eating a hoverfly

An insectivore is a carnivore, carnivorous animal or plant which eats insects. An alternative term is entomophage, which can also refer to the Entomophagy ...

niche from the mid-Jurassic onwards; the Jurassic '' Castorocauda'', for example, was a close relative of true mammals that had adaptations for swimming, digging and catching fish. Most, if not all, are thought to have remained nocturnal (the nocturnal bottleneck), accounting for much of the typical mammalian traits. The majority of the mammal species that existed in the Mesozoic Era were multituberculates, eutriconodonts and spalacotheriid

Spalacotheriidae is a family of extinct mammals belonging to the paraphyletic group 'Symmetrodonta'. They lasted from the Early Cretaceous to the Campanian in North America, Europe, Asia and North Africa.

Spalacotheriids are characterised by hav ...

s.Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous (geochronology, geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphy, chronostratigraphic name) is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 143.1 ...

shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of Clay mineral, clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g., Kaolinite, kaolin, aluminium, Al2Silicon, Si2Oxygen, O5(hydroxide, OH)4) and tiny f ...

in China's northeastern Liaoning Province. The fossil is nearly complete and includes tufts of fur and imprints of soft tissues.

The oldest-known fossil among the

The oldest-known fossil among the Eutheria

Eutheria (from Greek , 'good, right' and , 'beast'; ), also called Pan-Placentalia, is the clade consisting of Placentalia, placental mammals and all therian mammals that are more closely related to placentals than to marsupials.

Eutherians ...

("true beasts") is the small shrewlike '' Juramaia sinensis'', or "Jurassic mother from China", dated to 160 million years ago in the late Jurassic.fetus

A fetus or foetus (; : fetuses, foetuses, rarely feti or foeti) is the unborn offspring of a viviparous animal that develops from an embryo. Following the embryonic development, embryonic stage, the fetal stage of development takes place. Pren ...

during gestation periods. A narrow pelvic outlet indicates that the young were very small at birth and therefore pregnancy

Pregnancy is the time during which one or more offspring gestation, gestates inside a woman's uterus. A multiple birth, multiple pregnancy involves more than one offspring, such as with twins.

Conception (biology), Conception usually occurs ...

was short, as in modern marsupials. This suggests that the placenta was a later development.

One of the earliest-known monotremes was '' Teinolophos'', which lived about 120 million years ago in Australia. Monotremes have some features which may be inherited from the original amniotes such as the same orifice to urinate, defecate and reproduce (cloaca

A cloaca ( ), : cloacae ( or ), or vent, is the rear orifice that serves as the only opening for the digestive (rectum), reproductive, and urinary tracts (if present) of many vertebrate animals. All amphibians, reptiles, birds, cartilagin ...

)—as reptiles and birds also do— and they lay eggs which are leathery and uncalcified.

Earliest appearances of features

'' Hadrocodium'', whose fossils date from approximately 195 million years ago, in the early Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

, provides the first clear evidence of a jaw joint formed solely by the squamosal and dentary bones; there is no space in the jaw for the articular, a bone involved in the jaws of all early synapsids. The earliest clear evidence of hair or fur is in fossils of '' Castorocauda'' and '' Megaconus'', from 164 million years ago in the mid-Jurassic. In the 1950s, it was suggested that the foramina (passages) in the maxillae and premaxillae (bones in the front of the upper jaw) of cynodonts were channels which supplied blood vessels and nerves to vibrissae ( whiskers) and so were evidence of hair or fur;

The earliest clear evidence of hair or fur is in fossils of '' Castorocauda'' and '' Megaconus'', from 164 million years ago in the mid-Jurassic. In the 1950s, it was suggested that the foramina (passages) in the maxillae and premaxillae (bones in the front of the upper jaw) of cynodonts were channels which supplied blood vessels and nerves to vibrissae ( whiskers) and so were evidence of hair or fur;synapsids

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

of the epoch already had fur, setting the evolution of hairs possibly as far back as dicynodonts.therapsids

Therapsida is a clade comprising a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals and their ancestors and close relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including li ...

.[ Modern monotremes have lower body temperatures and more variable metabolic rates than marsupials and placentals,]synapomorphy

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel Phenotypic trait, character or character state that has evolution, evolved from its ancestral form (or Plesiomorphy and symplesiomorphy, plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy sh ...

between them and Mammaliaformes. They are omnipresent in non-placental Mammaliaformes, though ''Megazostrodon

''Megazostrodon'' is an extinct genus of basal mammaliaforms belonging to the order Morganucodonta. It is approximately 200 million years old. '' and '' Erythrotherium'' appear to have lacked them.

It has been suggested that the original function of lactation

Lactation describes the secretion of milk from the mammary glands and the period of time that a mother lactates to feed her young. The process naturally occurs with all sexually mature female mammals, although it may predate mammals. The process ...

(milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of lactating mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfeeding, breastfed human infants) before they are able to digestion, digest solid food. ...

production) was to keep eggs moist. Much of the argument is based on monotremes, the egg-laying mammals. In human females, mammary glands become fully developed during puberty, regardless of pregnancy.

Rise of the mammals

Therians took over the medium- to large-sized ecological niches in the Cenozoic, after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, also known as the K–T extinction, was the extinction event, mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth approximately 66 million years ago. The event cau ...

approximately 66 million years ago emptied ecological space once filled by non-avian dinosaurs and other groups of reptiles, as well as various other mammal groups,Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

through the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

.Paleocene

The Paleocene ( ), or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 mya (unit), million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), ...

, after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs.Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cre ...

origin for placentals, and a Paleocene origin for most modern clades.

The earliest-known ancestor of primates is '' Archicebus achilles''

Anatomy

Distinguishing features

Living mammal species can be identified by the presence of sweat glands, including those that are specialised to produce milk to nourish their young. In classifying fossils, however, other features must be used, since soft tissue glands and many other features are not visible in fossils.

Many traits shared by all living mammals appeared among the earliest members of the group:

* Jaw joint – The dentary (the lower jaw bone, which carries the teeth) and the squamosal (a small cranial bone) meet to form the joint. In most gnathostomes, including early therapsids

Therapsida is a clade comprising a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals and their ancestors and close relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including li ...

, the joint consists of the articular (a small bone at the back of the lower jaw) and quadrate (a small bone at the back of the upper jaw).[

* Middle ear – In crown-group mammals, sound is carried from the eardrum by a chain of three bones, the malleus, the ]incus

The ''incus'' (: incudes) or anvil in the ear is one of three small bones (ossicles) in the middle ear. The incus receives vibrations from the malleus, to which it is connected laterally, and transmits these to the stapes medially. The incus i ...

and the stapes. Ancestrally, the malleus and the incus are derived from the articular and the quadrate bones that constituted the jaw joint of early therapsids.

* Tooth replacement – Teeth can be replaced once ( diphyodonty) or (as in toothed whales and murid rodents) not at all ( monophyodonty). Elephants, manatees, and kangaroos continually grow new teeth throughout their life (polyphyodont

A polyphyodont is any animal whose tooth (animal), teeth are continually replaced. In contrast, diphyodonts are characterized by having only two successive sets of teeth.

Polyphyodonts include most toothed fishes (most notably sharks), many repti ...

y).

* Prismatic enamel – The enamel coating on the surface of a tooth consists of prisms, solid, rod-like structures extending from the dentin

Dentin ( ) (American English) or dentine ( or ) (British English) () is a calcified tissue (biology), tissue of the body and, along with tooth enamel, enamel, cementum, and pulp (tooth), pulp, is one of the four major components of teeth. It i ...

to the tooth's surface.

* Occipital condyles – Two knobs at the base of the skull fit into the topmost neck vertebra; most other tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s, in contrast, have only one such knob.

For the most part, these characteristics were not present in the Triassic ancestors of the mammals. Nearly all mammaliaforms possess an epipubic bone, the exception being modern placentals.[

]

Sexual dimorphism

On average, male mammals are larger than females, with males being at least 10% larger than females in over 45% of investigated species. Most mammalian orders also exhibit male-biased

On average, male mammals are larger than females, with males being at least 10% larger than females in over 45% of investigated species. Most mammalian orders also exhibit male-biased sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

, although some orders do not show any bias or are significantly female-biased ( Lagomorpha). Sexual size dimorphism increases with body size across mammals ( Rensch's rule), suggesting that there are parallel selection pressures on both male and female size. Male-biased dimorphism relates to sexual selection on males through male–male competition for females, as there is a positive correlation between the degree of sexual selection, as indicated by mating systems, and the degree of male-biased size dimorphism. The degree of sexual selection is also positively correlated with male and female size across mammals. Further, parallel selection pressure on female mass is identified in that age at weaning is significantly higher in more polygynous species, even when correcting for body mass. Also, the reproductive rate is lower for larger females, indicating that fecundity selection selects for smaller females in mammals. Although these patterns hold across mammals as a whole, there is considerable variation across orders.

Biological systems

The majority of mammals have seven cervical vertebrae

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae (: vertebra) are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae (divided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mammals) lie caudal (toward the tail) of cervical vertebrae. In saurop ...

(bones in the neck). The exceptions are the manatee

Manatees (, family (biology), family Trichechidae, genus ''Trichechus'') are large, fully aquatic, mostly herbivory, herbivorous marine mammals sometimes known as sea cows. There are three accepted living species of Trichechidae, representing t ...

and the two-toed sloth, which have six, and the three-toed sloth which has nine. All mammalian brains possess a neocortex

The neocortex, also called the neopallium, isocortex, or the six-layered cortex, is a set of layers of the mammalian cerebral cortex involved in higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, cognition, generation of motor commands, ...

, a brain region unique to mammals. Placental brains have a corpus callosum, unlike monotremes and marsupials.

Circulatory systems

The mammalian heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ found in humans and other animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels. The heart and blood vessels together make the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrie ...

has four chambers, two upper atria, the receiving chambers, and two lower ventricles, the discharging chambers. The heart has four valves, which separate its chambers and ensures blood flows in the correct direction through the heart (preventing backflow). After gas exchange in the pulmonary capillaries (blood vessels in the lungs), oxygen-rich blood returns to the left atrium via one of the four pulmonary veins. Blood flows nearly continuously back into the atrium, which acts as the receiving chamber, and from here through an opening into the left ventricle. Most blood flows passively into the heart while both the atria and ventricles are relaxed, but toward the end of the ventricular relaxation period, the left atrium will contract, pumping blood into the ventricle. The heart also requires nutrients and oxygen found in blood like other muscles, and is supplied via coronary arteries

The coronary arteries are the arteries, arterial blood vessels of coronary circulation, which transport oxygenated blood to the Cardiac muscle, heart muscle. The heart requires a continuous supply of oxygen to function and survive, much like any ...

.

Respiratory systems

The

The lung

The lungs are the primary Organ (biology), organs of the respiratory system in many animals, including humans. In mammals and most other tetrapods, two lungs are located near the Vertebral column, backbone on either side of the heart. Their ...

s of mammals are spongy and honeycombed. Breathing is mainly achieved with the diaphragm, which divides the thorax from the abdominal cavity, forming a dome convex to the thorax. Contraction of the diaphragm flattens the dome, increasing the volume of the lung cavity. Air enters through the oral and nasal cavities, and travels through the larynx, trachea and bronchi, and expands the alveoli. Relaxing the diaphragm has the opposite effect, decreasing the volume of the lung cavity, causing air to be pushed out of the lungs. During exercise, the abdominal wall contracts

A contract is an agreement that specifies certain legally enforceable rights and obligations pertaining to two or more parties. A contract typically involves consent to transfer of goods, services, money, or promise to transfer any of thos ...

, increasing pressure on the diaphragm, which forces air out quicker and more forcefully. The rib cage is able to expand and contract the chest cavity through the action of other respiratory muscles. Consequently, air is sucked into or expelled out of the lungs, always moving down its pressure gradient.[ This type of lung is known as a bellows lung due to its resemblance to blacksmith bellows.]

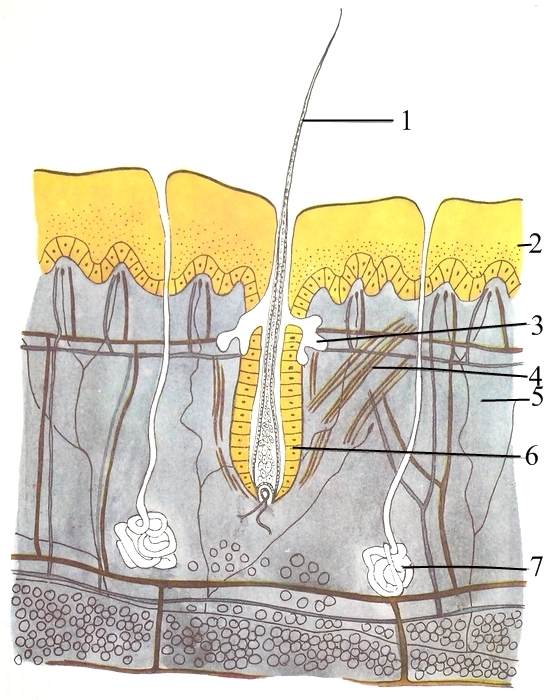

Integumentary systems

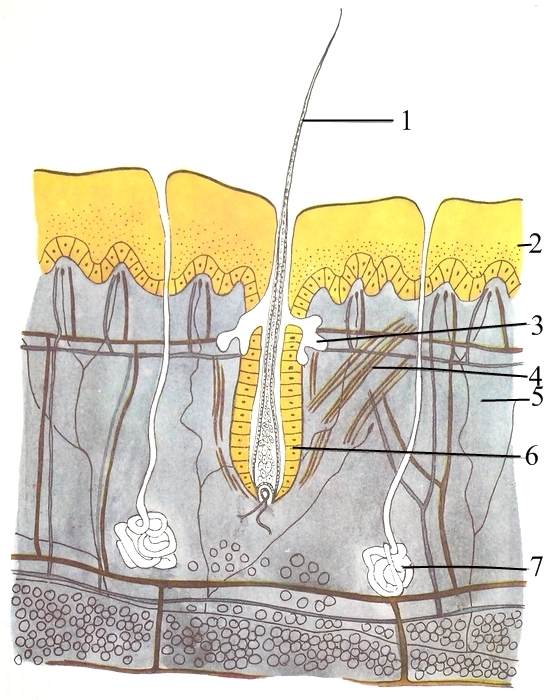

The integumentary system (skin) is made up of three layers: the outermost

The integumentary system (skin) is made up of three layers: the outermost epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and Subcutaneous tissue, hypodermis. The epidermal layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the ...

, the dermis

The dermis or corium is a layer of skin between the epidermis (skin), epidermis (with which it makes up the cutis (anatomy), cutis) and subcutaneous tissues, that primarily consists of dense irregular connective tissue and cushions the body from s ...

and the hypodermis. The epidermis is typically 10 to 30 cells thick; its main function is to provide a waterproof layer. Its outermost cells are constantly lost; its bottommost cells are constantly dividing and pushing upward. The middle layer, the dermis, is 15 to 40 times thicker than the epidermis. The dermis is made up of many components, such as bony structures and blood vessels. The hypodermis is made up of adipose tissue

Adipose tissue (also known as body fat or simply fat) is a loose connective tissue composed mostly of adipocytes. It also contains the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of cells including preadipocytes, fibroblasts, Blood vessel, vascular endothel ...

, which stores lipids and provides cushioning and insulation. The thickness of this layer varies widely from species to species;[ ]marine mammal

Marine mammals are mammals that rely on marine ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as cetaceans, pinnipeds, sirenians, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, unified only by their reliance on marine enviro ...

s require a thick hypodermis (blubber

Blubber is a thick layer of Blood vessel, vascularized adipose tissue under the skin of all cetaceans, pinnipeds, penguins, and sirenians. It was present in many marine reptiles, such as Ichthyosauria, ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs.

Description ...

) for insulation, and right whales have the thickest blubber at . Although other animals have features such as whiskers, feather

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and an exa ...

s, setae, or cilia

The cilium (: cilia; ; in Medieval Latin and in anatomy, ''cilium'') is a short hair-like membrane protrusion from many types of eukaryotic cell. (Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea.) The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike proj ...

that superficially resemble it, no animals other than mammals have hair

Hair is a protein filament that grows from follicles found in the dermis. Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals.

The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick terminal and ...

. It is a definitive characteristic of the class, though some mammals have very little.

Digestive systems

Herbivores have developed a diverse range of physical structures to facilitate the consumption of plant material. To break up intact plant tissues, mammals have developed teeth structures that reflect their feeding preferences. For instance, frugivores (animals that feed primarily on fruit) and herbivores that feed on soft foliage have low-crowned teeth specialised for grinding foliage and seed

In botany, a seed is a plant structure containing an embryo and stored nutrients in a protective coat called a ''testa''. More generally, the term "seed" means anything that can be Sowing, sown, which may include seed and husk or tuber. Seeds ...

s. Grazing

In agriculture, grazing is a method of animal husbandry whereby domestic livestock are allowed outdoors to free range (roam around) and consume wild vegetations in order to feed conversion ratio, convert the otherwise indigestible (by human diges ...

animals that tend to eat hard, silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundant f ...

-rich grasses, have high-crowned teeth, which are capable of grinding tough plant tissues and do not wear down as quickly as low-crowned teeth. Most carnivorous mammals have carnassial

Carnassials are paired upper and lower teeth modified in such a way as to allow enlarged and often self-sharpening edges to pass by each other in a shearing manner. This adaptation is found in carnivorans, where the carnassials are the modified f ...

teeth (of varying length depending on diet), long canines and similar tooth replacement patterns.

The stomach of even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla) is divided into four sections: the rumen

The rumen, also known as a paunch, is the largest stomach compartment in ruminants. The rumen and the reticulum make up the reticulorumen in ruminant animals. The diverse microbial communities in the rumen allows it to serve as the primary si ...

, the reticulum, the omasum and the abomasum (only ruminant

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microb ...

s have a rumen). After the plant material is consumed, it is mixed with saliva in the rumen and reticulum and separates into solid and liquid material. The solids lump together to form a bolus (or cud), and is regurgitated. When the bolus enters the mouth, the fluid is squeezed out with the tongue and swallowed again. Ingested food passes to the rumen and reticulum where cellulolytic microbes (bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

, protozoa and fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

) produce cellulase, which is needed to break down the cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of glycosidic bond, β(1→4) linked glucose, D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important s ...

in plants.cecum

The cecum ( caecum, ; plural ceca or caeca, ) is a pouch within the peritoneum that is considered to be the beginning of the large intestine. It is typically located on the right side of the body (the same side of the body as the appendix (a ...

, where it is fermented by bacteria. Carnivora have a simple stomach adapted to digest primarily meat, as compared to the elaborate digestive systems of herbivorous animals, which are necessary to break down tough, complex plant fibres. The cecum is either absent or short and simple, and the large intestine is not sacculated or much wider than the small intestine.

Excretory and genitourinary systems

The mammalian

The mammalian excretory system

The excretory system is a passive biological system that removes excess, unnecessary materials from the body fluids of an organism, so as to help maintain internal chemical homeostasis and prevent damage to the body. The dual function of excret ...

involves many components. Like most other land animals, mammals are ureotelic, and convert ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

into urea

Urea, also called carbamide (because it is a diamide of carbonic acid), is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two Amine, amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest am ...

, which is done by the liver

The liver is a major metabolic organ (anatomy), organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological Function (biology), functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of var ...

as part of the urea cycle. Bilirubin

Bilirubin (BR) (adopted from German, originally bili—bile—plus ruber—red—from Latin) is a red-orange compound that occurs in the normcomponent of the straw-yellow color in urine. Another breakdown product, stercobilin, causes the brown ...

, a waste product derived from blood cells, is passed through bile

Bile (from Latin ''bilis''), also known as gall, is a yellow-green/misty green fluid produced by the liver of most vertebrates that aids the digestion of lipids in the small intestine. In humans, bile is primarily composed of water, is pro ...

and urine

Urine is a liquid by-product of metabolism in humans and many other animals. In placental mammals, urine flows from the Kidney (vertebrates), kidneys through the ureters to the urinary bladder and exits the urethra through the penile meatus (mal ...

with the help of enzymes excreted by the liver. The passing of bilirubin via bile through the intestinal tract gives mammalian feces

Feces (also known as faeces American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, or fæces; : faex) are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the ...

a distinctive brown coloration. Distinctive features of the mammalian kidney include the presence of the renal pelvis and renal pyramids, and of a clearly distinguishable cortex

Cortex or cortical may refer to:

Biology

* Cortex (anatomy), the outermost layer of an organ

** Cerebral cortex, the outer layer of the vertebrate cerebrum, part of which is the ''forebrain''

*** Motor cortex, the regions of the cerebral cortex i ...

and medulla, which is due to the presence of elongated loops of Henle. Only the mammalian kidney has a bean shape, although there are some exceptions, such as the multilobed reniculate kidneys of pinnipeds, cetaceans and bears.[ Most adult placentals have no remaining trace of the ]cloaca

A cloaca ( ), : cloacae ( or ), or vent, is the rear orifice that serves as the only opening for the digestive (rectum), reproductive, and urinary tracts (if present) of many vertebrate animals. All amphibians, reptiles, birds, cartilagin ...

. In the embryo, the embryonic cloaca divides into a posterior region that becomes part of the anus, and an anterior region that has different fates depending on the sex of the individual: in females, it develops into the vestibule or urogenital sinus

The urogenital sinus is a body part of a human or other Placentalia, placental only present in the development of the urinary system, development of the urinary and development of the reproductive organs, reproductive organs. It is the ventral p ...

that receives the urethra and vagina

In mammals and other animals, the vagina (: vaginas or vaginae) is the elastic, muscular sex organ, reproductive organ of the female genital tract. In humans, it extends from the vulval vestibule to the cervix (neck of the uterus). The #Vag ...

, while in males it forms the entirety of the penile urethra.[ However, the afrosoricids and some ]shrew

Shrews ( family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, West Indies shrews, or marsupial shrews, which belong to dif ...

s retain a cloaca as adults. In marsupials, the genital tract is separate from the anus, but a trace of the original cloaca does remain externally.[

]

Sound production

As in all other tetrapods, mammals have a

As in all other tetrapods, mammals have a larynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ (anatomy), organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal ...

that can quickly open and close to produce sounds, and a supralaryngeal vocal tract

The vocal tract is the cavity in human bodies and in animals where the sound produced at the sound source (larynx in mammals; syrinx in birds) is filtered.

In birds, it consists of the trachea, the syrinx, the oral cavity, the upper part of t ...

which filters this sound. The lungs and surrounding musculature provide the air stream and pressure required to phonate. The larynx controls the pitch and volume

Volume is a measure of regions in three-dimensional space. It is often quantified numerically using SI derived units (such as the cubic metre and litre) or by various imperial or US customary units (such as the gallon, quart, cubic inch) ...

of sound, but the strength the lungs exert to exhale also contributes to volume. More primitive mammals, such as the echidna, can only hiss, as sound is achieved solely through exhaling through a partially closed larynx. Other mammals phonate using vocal folds. The movement or tenseness of the vocal folds can result in many sounds such as purr

A purr or whirr is a tonal fluttering sound made by some species of felids, including both larger, wild cats and the domestic cat (''Felis catus''), as well as two species of genets. It varies in loudness and tone among species and in the same ...

ing and screaming

A scream is a loud/hard speech production, vocalization in which air is passed through the vocal cords with greater force than is used in regular or close-distance vocalisation. This can be performed by any creature possessing lungs, including h ...

. Mammals can change the position of the larynx, allowing them to breathe through the nose while swallowing through the mouth, and to form both oral and nasal sounds; nasal sounds, such as a dog whine, are generally soft sounds, and oral sounds, such as a dog bark, are generally loud.[

Some mammals have a large larynx and thus a low-pitched voice, namely the hammer-headed bat (''Hypsignathus monstrosus'') where the larynx can take up the entirety of the thoracic cavity while pushing the lungs, heart, and trachea into the ]abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the gut, belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach) is the front part of the torso between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and in other vertebrates. The area occupied by the abdomen is called the abdominal ...

. Large vocal pads can also lower the pitch, as in the low-pitched roars of big cat

The term "big cat" is typically used to refer to any of the five living members of the genus ''Panthera'', namely the tiger, lion, jaguar, leopard, and snow leopard.

All cats descend from the ''Felidae'' family, sharing similar musculature, c ...

s. The production of infrasound is possible in some mammals such as the African elephant (''Loxodonta'' spp.) and baleen whale

Baleen whales (), also known as whalebone whales, are marine mammals of the order (biology), parvorder Mysticeti in the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises), which use baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their mouths to sieve plankt ...

s. Small mammals with small larynxes have the ability to produce ultrasound

Ultrasound is sound with frequency, frequencies greater than 20 Hertz, kilohertz. This frequency is the approximate upper audible hearing range, limit of human hearing in healthy young adults. The physical principles of acoustic waves apply ...

, which can be detected by modifications to the middle ear and cochlea

The cochlea is the part of the inner ear involved in hearing. It is a spiral-shaped cavity in the bony labyrinth, in humans making 2.75 turns around its axis, the modiolus (cochlea), modiolus. A core component of the cochlea is the organ of Cort ...

. Ultrasound is inaudible to birds and reptiles, which might have been important during the Mesozoic, when birds and reptiles were the dominant predators. This private channel is used by some rodents in, for example, mother-to-pup communication, and by bats when echolocating. Toothed whales also use echolocation, but, as opposed to the vocal membrane that extends upward from the vocal folds, they have a melon to manipulate sounds. Some mammals, namely the primates, have air sacs attached to the larynx, which may function to lower the resonances or increase the volume of sound.vagus nerve

The vagus nerve, also known as the tenth cranial nerve (CN X), plays a crucial role in the autonomic nervous system, which is responsible for regulating involuntary functions within the human body. This nerve carries both sensory and motor fibe ...

. The vocal tract is supplied by the hypoglossal nerve and facial nerve

The facial nerve, also known as the seventh cranial nerve, cranial nerve VII, or simply CN VII, is a cranial nerve that emerges from the pons of the brainstem, controls the muscles of facial expression, and functions in the conveyance of ta ...

s. Electrical stimulation of the periaqueductal grey (PEG) region of the mammalian midbrain elicit vocalisations. The ability to learn new vocalisations is only exemplified in humans, seals, cetaceans, elephants and possibly bats; in humans, this is the result of a direct connection between the motor cortex

The motor cortex is the region of the cerebral cortex involved in the planning, motor control, control, and execution of voluntary movements.

The motor cortex is an area of the frontal lobe located in the posterior precentral gyrus immediately ...

, which controls movement, and the motor neurons in the spinal cord.[

]

Fur

The primary function of the fur of mammals is thermoregulation

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

. Others include protection, sensory purposes, waterproofing, and camouflage.[

* Definitive – which may be ]shed

A shed is typically a simple, single-storey (though some sheds may have two or more stories and or a loft) roofed structure, often used for storage, for hobby, hobbies, or as a workshop, and typically serving as outbuilding, such as in a bac ...

after reaching a certain length

* Vibrissae – sensory hairs, most commonly whiskers

* Pelage – guard hairs, under-fur, and awn hair

* Spines – stiff guard hair used for defence (such as in porcupines)

* Bristles – long hairs usually used in visual signals. (such as a lion's mane)

* Velli – often called "down fur" which insulates newborn mammals

* Wool

Wool is the textile fiber obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have some properties similar to animal w ...

– long, soft and often curly

Thermoregulation

Hair length is not a factor in thermoregulation: for example, some tropical mammals such as sloths have the same length of fur length as some arctic mammals but with less insulation; and, conversely, other tropical mammals with short hair have the same insulating value as arctic mammals. The denseness of fur can increase an animal's insulation value, and arctic mammals especially have dense fur; for example, the musk ox has guard hairs measuring as well as a dense underfur, which forms an airtight coat, allowing them to survive in temperatures of .[ Some desert mammals, such as camels, use dense fur to prevent solar heat from reaching their skin, allowing the animal to stay cool; a camel's fur may reach in the summer, but the skin stays at .][ Aquatic mammals, conversely, trap air in their fur to conserve heat by keeping the skin dry.][

]

Coloration

Mammalian coats are coloured for a variety of reasons, the major selective pressures including camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

, sexual selection

Sexual selection is a mechanism of evolution in which members of one sex mate choice, choose mates of the other sex to mating, mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex ...

, communication, and thermoregulation. Coloration in both the hair and skin of mammals is mainly determined by the type and amount of melanin; eumelanins for brown and black colours and pheomelanin for a range of yellowish to reddish colours, giving mammals an earth tone.mandrill

The mandrill (''Mandrillus sphinx'') is a large Old World monkey native to west central Africa. It is one of the most colorful mammals in the world, with red and blue skin on its face and posterior. The species is Sexual dimorphism, sexually ...

s and vervet monkeys, and opossums such as the Mexican mouse opossums and Derby's woolly opossums, have blue skin due to light diffraction in collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix of the connective tissues of many animals. It is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up 25% to 35% of protein content. Amino acids are bound together to form a trip ...

fibres.algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

; this may be a symbiotic relation that affords camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

to the sloths.

Camouflage is a powerful influence in a large number of mammals, as it helps to conceal individuals from predators or prey.convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

.Aposematism

Aposematism is the Advertising in biology, advertising by an animal, whether terrestrial or marine, to potential predation, predators that it is not worth attacking or eating. This unprofitability may consist of any defenses which make the pr ...

, warning off possible predators, is the most likely explanation of the black-and-white pelage of many mammals which are able to defend themselves, such as in the foul-smelling skunk and the powerful and aggressive honey badger. Coat color is sometimes sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

, as in many primate species. Differences in female and male coat color may indicate nutrition and hormone levels, important in mate selection.vole

Voles are small rodents that are relatives of lemmings and hamsters, but with a stouter body; a longer, hairy tail; a slightly rounder head; smaller eyes and ears; and differently formed molars (high-crowned with angular cusps instead of lo ...

s, have darker fur in the winter. The white, pigmentless fur of arctic mammals, such as the polar bear, may reflect more solar radiation directly onto the skin.[ The dazzling black-and-white striping of zebras appear to provide some protection from biting flies.]

Reproductive system

Mammals reproduce by internal fertilisation

Mammals reproduce by internal fertilisationhermaphrodite

A hermaphrodite () is a sexually reproducing organism that produces both male and female gametes. Animal species in which individuals are either male or female are gonochoric, which is the opposite of hermaphroditic.

The individuals of many ...

s where there is no such schism). Male mammals ejaculate semen

Semen, also known as seminal fluid, is a bodily fluid that contains spermatozoon, spermatozoa which is secreted by the male gonads (sexual glands) and other sexual organs of male or hermaphrodite, hermaphroditic animals. In humans and placen ...

during copulation through a penis

A penis (; : penises or penes) is a sex organ through which male and hermaphrodite animals expel semen during copulation (zoology), copulation, and through which male placental mammals and marsupials also Urination, urinate.

The term ''pen ...