Chlorine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chlorine is a

p. 105:

''"Accipe salis petrae, vitrioli, & alumnis partes aequas: exsiccato singula, & connexis simul, distilla aquam. Quae nil aliud est, quam merum sal volatile. Hujus accipe uncias quatuor, salis armeniaci unciam junge, in forti vitro, alembico, per caementum (ex cera, colophonia, & vitri pulverre) calidissime affusum, firmato; mox, etiam in frigore, Gas excitatur, & vas, utut forte, dissilit cum fragore."'' (Take equal parts of saltpeter .e., sodium nitrate vitriol .e., concentrated sulfuric acid and alum: dry each and combine simultaneously; distill off the water .e., liquid That istillateis nothing else than pure volatile salt .e., spirit of nitre, nitric acid Take four ounces of this iz, nitric acid add one ounce of Armenian salt .e., ammonium chloride lace itin a strong glass alembic sealed by cement ( adefrom wax, rosin, and powdered glass) hat has beenpoured very hot; soon, even in the cold, gas is stimulated, and the vessel, however strong, bursts into fragments.) From ''"De Flatibus"'' (On gases)

p. 408

: ''"Sal armeniacus enim, & aqua chrysulca, quae singula per se distillari, possunt, & pati calorem: sin autem jungantur, & intepescant, non possunt non, quin statim in Gas sylvestre, sive incoercibilem flatum transmutentur."'' (Truly Armenian salt .e., ammonium chlorideand nitric acid, each of which can be distilled by itself, and submitted to heat; but if, on the other hand, they be combined and become warm, they cannot but be changed immediately into carbon dioxide ote: van Helmont's identification of the gas is mistakenor an incondensable gas.)

See also:

Helmont, Johannes (Joan) Baptista Van, Encyclopedia.Com

: "Others were chlorine gas from the reaction of nitric acid and sal ammoniac; ... " * Wisniak, Jaime (2009) "Carl Wilhelm Scheele," ''Revista CENIC Ciencias Químicas'', 40 (3): 165–73; see p. 168: "Early in the seventeenth century Johannes Baptiste van Helmont (1579–1644) mentioned that when sal marin (sodium chloride) or sal ammoniacus and aqua chrysulca (nitric acid) were mixed together, a flatus incoercible (non-condensable gas) was evolved."

The element was first studied in detail in 1774 by Swedish chemist

The element was first studied in detail in 1774 by Swedish chemist

Chlorine is the second halogen, being a nonmetal in group 17 of the periodic table. Its properties are thus similar to

Chlorine is the second halogen, being a nonmetal in group 17 of the periodic table. Its properties are thus similar to

The simplest chlorine compound is

The simplest chlorine compound is

The chlorine oxides are well-studied in spite of their instability (all of them are endothermic compounds). They are important because they are produced when

The chlorine oxides are well-studied in spite of their instability (all of them are endothermic compounds). They are important because they are produced when

Like the other carbon–halogen bonds, the C–Cl bond is a common functional group that forms part of core

Like the other carbon–halogen bonds, the C–Cl bond is a common functional group that forms part of core

Chlorine is too reactive to occur as the free element in nature but is very abundant in the form of its chloride salts. It is the 20th most abundant element in Earth's crust and makes up 126

Chlorine is too reactive to occur as the free element in nature but is very abundant in the form of its chloride salts. It is the 20th most abundant element in Earth's crust and makes up 126

The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination

'. . Harvard University Press. pp. 121–22. These "putrid miasmas" were thought by many to cause the spread of "contagion" and "infection" – both words used before the germ theory of infection. Chloride of lime was used for destroying odors and "putrid matter". One source claims chloride of lime was used by Dr. John Snow to disinfect water from the cholera-contaminated well that was feeding the Broad Street pump in 1854 London, though three other reputable sources that describe that famous cholera epidemic do not mention the incident.Vinten-Johansen, Peter, Howard Brody, Nigel Paneth, Stephen Rachman and Michael Rip. (2003). ''Cholera, Chloroform, and the Science of Medicine''. New York:Oxford University. One reference makes it clear that chloride of lime was used to disinfect the offal and filth in the streets surrounding the Broad Street pump – a common practice in mid-nineteenth century England.

The first continuous application of chlorination to drinking U.S. water was installed in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1908. By 1918, the US Department of Treasury called for all drinking water to be disinfected with chlorine. Chlorine is presently an important chemical for water purification (such as in water treatment plants), in

The first continuous application of chlorination to drinking U.S. water was installed in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1908. By 1918, the US Department of Treasury called for all drinking water to be disinfected with chlorine. Chlorine is presently an important chemical for water purification (such as in water treatment plants), in

Chlorine is widely used for purifying water, especially potable water supplies and water used in swimming pools. Several catastrophic collapses of swimming pool ceilings have occurred from chlorine-induced stress corrosion cracking of

Chlorine is widely used for purifying water, especially potable water supplies and water used in swimming pools. Several catastrophic collapses of swimming pool ceilings have occurred from chlorine-induced stress corrosion cracking of

Chlorine

at '' The Periodic Table of Videos'' (University of Nottingham) * Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

Chlorine

Chlorine Production Using Mercury, Environmental Considerations and Alternatives

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health – Chlorine Page

Chlorine Institute

– Trade association representing the chlorine industry

Chlorine Online

– the web portal of Eurochlor – the business association of the European chlor-alkali industry {{Authority control Chemical elements Chemical hazards Diatomic nonmetals Gases with color Halogens Industrial gases Oxidizing agents Pulmonary agents Reactive nonmetals Swimming pool equipment

chemical element

A chemical element is a chemical substance whose atoms all have the same number of protons. The number of protons is called the atomic number of that element. For example, oxygen has an atomic number of 8: each oxygen atom has 8 protons in its ...

; it has symbol

A symbol is a mark, Sign (semiotics), sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, physical object, object, or wikt:relationship, relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by cr ...

Cl and atomic number

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol ''Z'') of a chemical element is the charge number of its atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei composed of protons and neutrons, this is equal to the proton number (''n''p) or the number of pro ...

17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine

Fluorine is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol F and atomic number 9. It is the lightest halogen and exists at Standard temperature and pressure, standard conditions as pale yellow Diatomic molecule, diatomic gas. Fluorine is extre ...

and bromine

Bromine is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Br and atomic number 35. It is a volatile red-brown liquid at room temperature that evaporates readily to form a similarly coloured vapour. Its properties are intermediate between th ...

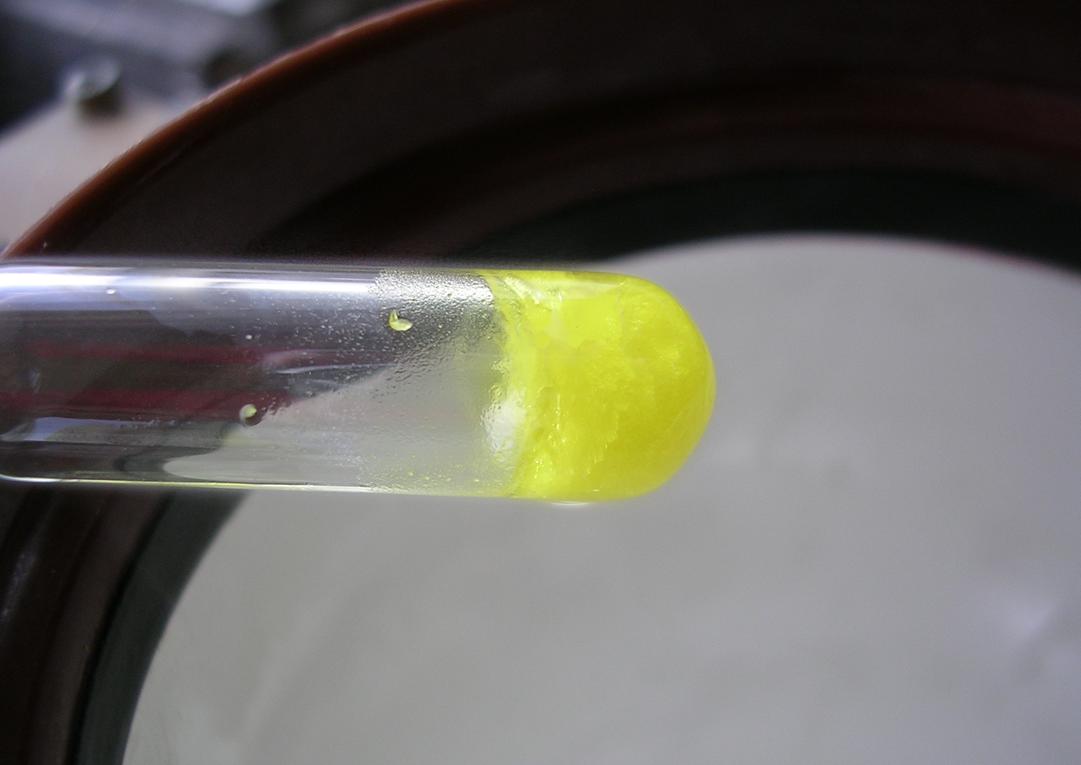

in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between them. Chlorine is a yellow-green gas at room temperature. It is an extremely reactive element and a strong oxidising agent: among the elements, it has the highest electron affinity and the third-highest electronegativity

Electronegativity, symbolized as , is the tendency for an atom of a given chemical element to attract shared electrons (or electron density) when forming a chemical bond. An atom's electronegativity is affected by both its atomic number and the ...

on the revised Pauling scale, behind only oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

and fluorine.

Chlorine played an important role in the experiments conducted by medieval alchemists, which commonly involved the heating of chloride salts like ammonium chloride

Ammonium chloride is an inorganic chemical compound with the chemical formula , also written as . It is an ammonium salt of hydrogen chloride. It consists of ammonium cations and chloride anions . It is a white crystalline salt (chemistry), sal ...

( sal ammoniac) and sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as Salt#Edible salt, edible salt, is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. It is transparent or translucent, brittle, hygroscopic, and occurs a ...

( common salt), producing various chemical substances containing chlorine such as hydrogen chloride

The Chemical compound, compound hydrogen chloride has the chemical formula and as such is a hydrogen halide. At room temperature, it is a colorless gas, which forms white fumes of hydrochloric acid upon contact with atmospheric water vapor. Hyd ...

, mercury(II) chloride (corrosive sublimate), and . However, the nature of free chlorine gas as a separate substance was only recognised around 1630 by Jan Baptist van Helmont. Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (, ; 9 December 1742 – 21 May 1786) was a Swedish Pomerania, German-Swedish pharmaceutical chemist.

Scheele discovered oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first), and identified the elements molybd ...

wrote a description of chlorine gas in 1774, supposing it to be an oxide

An oxide () is a chemical compound containing at least one oxygen atom and one other element in its chemical formula. "Oxide" itself is the dianion (anion bearing a net charge of −2) of oxygen, an O2− ion with oxygen in the oxidation st ...

of a new element. In 1809, chemists suggested that the gas might be a pure element, and this was confirmed by Sir Humphry Davy in 1810, who named it after the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

(, "pale green") because of its colour.

Because of its great reactivity, all chlorine in the Earth's crust is in the form of ionic chloride

The term chloride refers to a compound or molecule that contains either a chlorine anion (), which is a negatively charged chlorine atom, or a non-charged chlorine atom covalently bonded to the rest of the molecule by a single bond (). The pr ...

compounds, which includes table salt. It is the second-most abundant halogen (after fluorine) and 20th most abundant element in Earth's crust. These crystal deposits are nevertheless dwarfed by the huge reserves of chloride in seawater.

Elemental chlorine is commercially produced from brine by electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses Direct current, direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of c ...

, predominantly in the chloralkali process. The high oxidising potential of elemental chlorine led to the development of commercial bleaches and disinfectant

A disinfectant is a chemical substance or compound used to inactivate or destroy microorganisms on inert surfaces. Disinfection does not necessarily kill all microorganisms, especially resistant bacterial spores; it is less effective than ...

s, and a reagent for many processes in the chemical industry. Chlorine is used in the manufacture of a wide range of consumer products, about two-thirds of them organic chemicals such as polyvinyl chloride

Polyvinyl chloride (alternatively: poly(vinyl chloride), colloquial: vinyl or polyvinyl; abbreviated: PVC) is the world's third-most widely produced synthetic polymer of plastic (after polyethylene and polypropylene). About 40 million tons of ...

(PVC), many intermediates for the production of plastics, and other end products which do not contain the element. As a common disinfectant, elemental chlorine and chlorine-generating compounds are used more directly in swimming pool

A swimming pool, swimming bath, wading pool, paddling pool, or simply pool, is a structure designed to hold water to enable Human swimming, swimming and associated activities. Pools can be built into the ground (in-ground pools) or built abo ...

s to keep them sanitary. Elemental chlorine at high concentration

In chemistry, concentration is the abundance of a constituent divided by the total volume of a mixture. Several types of mathematical description can be distinguished: '' mass concentration'', '' molar concentration'', '' number concentration'', ...

is extremely dangerous, and poisonous to most living organisms. As a chemical warfare agent, chlorine was first used in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

as a poison gas weapon.

In the form of chloride ions

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

, chlorine is necessary to all known species of life. Other types of chlorine compounds are rare in living organisms, and artificially produced chlorinated organics range from inert to toxic. In the upper atmosphere, chlorine-containing organic molecules such as chlorofluorocarbon

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) are fully or partly Halogenation, halogenated hydrocarbons that contain carbon (C), hydrogen (H), chlorine (Cl), and fluorine (F). They are produced as volatility (chemistry), volat ...

s have been implicated in ozone depletion. Small quantities of elemental chlorine are generated by oxidation of chloride ions in neutrophil

Neutrophils are a type of phagocytic white blood cell and part of innate immunity. More specifically, they form the most abundant type of granulocytes and make up 40% to 70% of all white blood cells in humans. Their functions vary in differe ...

s as part of an immune system

The immune system is a network of biological systems that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to bacteria, as well as Tumor immunology, cancer cells, Parasitic worm, parasitic ...

response against bacteria.

History

The most common compound of chlorine, sodium chloride, has been known since ancient times; archaeologists have found evidence that rock salt was used as early as 3000 BC and brine as early as 6000 BC.Early discoveries

Around 900, the authors of the Arabic writings attributed toJabir ibn Hayyan

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic: , variously called al-Ṣūfī, al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, or al-Ṭūsī), died 806−816, is the purported author of a large number of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The treatises that ...

(Latin: Geber) and the Persian physician and alchemist Abu Bakr al-Razi ( 865–925, Latin: Rhazes) were experimenting with sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride

Ammonium chloride is an inorganic chemical compound with the chemical formula , also written as . It is an ammonium salt of hydrogen chloride. It consists of ammonium cations and chloride anions . It is a white crystalline salt (chemistry), sal ...

), which when it was distilled together with vitriol (hydrated sulfates

The sulfate or sulphate ion is a Polyatomic ion, polyatomic anion with the empirical formula . Salts, acid derivatives, and peroxides of sulfate are widely used in industry. Sulfates occur widely in everyday life. Sulfates are salt (chemistry), ...

of various metals) produced hydrogen chloride

The Chemical compound, compound hydrogen chloride has the chemical formula and as such is a hydrogen halide. At room temperature, it is a colorless gas, which forms white fumes of hydrochloric acid upon contact with atmospheric water vapor. Hyd ...

. However, it appears that in these early experiments with chloride salts, the gaseous products were discarded, and hydrogen chloride may have been produced many times before it was discovered that it can be put to chemical use. One of the first such uses was the synthesis of mercury(II) chloride (corrosive sublimate), whose production from the heating of mercury either with alum

An alum () is a type of chemical compound, usually a hydrated double salt, double sulfate salt (chemistry), salt of aluminium with the general chemical formula, formula , such that is a valence (chemistry), monovalent cation such as potassium ...

and ammonium chloride or with vitriol and sodium chloride was first described in the ''De aluminibus et salibus'' ("On Alums and Salts", an eleventh- or twelfth century Arabic text falsely attributed to Abu Bakr al-Razi and translated into Latin in the second half of the twelfth century by Gerard of Cremona, 1144–1187). Another important development was the discovery by pseudo-Geber (in the ''De inventione veritatis'', "On the Discovery of Truth", after c. 1300) that by adding ammonium chloride to nitric acid

Nitric acid is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but samples tend to acquire a yellow cast over time due to decomposition into nitrogen oxide, oxides of nitrogen. Most com ...

, a strong solvent capable of dissolving gold (i.e., ''aqua regia

Aqua regia (; from Latin, "regal water" or "royal water") is a mixture of nitric acid and hydrochloric acid, optimally in a molar concentration, molar ratio of 1:3. Aqua regia is a fuming liquid. Freshly prepared aqua regia is colorless, but i ...

'') could be produced. Although ''aqua regia'' is an unstable mixture that continually gives off fumes containing free chlorine gas, this chlorine gas appears to have been ignored until c. 1630, when its nature as a separate gaseous substance was recognised by the Brabantian chemist and physician Jan Baptist van Helmont. From ''"Complexionum atque mistionum elementalium figmentum."'' (Formation of combinations and of mixtures of elements), §37p. 105:

''"Accipe salis petrae, vitrioli, & alumnis partes aequas: exsiccato singula, & connexis simul, distilla aquam. Quae nil aliud est, quam merum sal volatile. Hujus accipe uncias quatuor, salis armeniaci unciam junge, in forti vitro, alembico, per caementum (ex cera, colophonia, & vitri pulverre) calidissime affusum, firmato; mox, etiam in frigore, Gas excitatur, & vas, utut forte, dissilit cum fragore."'' (Take equal parts of saltpeter .e., sodium nitrate vitriol .e., concentrated sulfuric acid and alum: dry each and combine simultaneously; distill off the water .e., liquid That istillateis nothing else than pure volatile salt .e., spirit of nitre, nitric acid Take four ounces of this iz, nitric acid add one ounce of Armenian salt .e., ammonium chloride lace itin a strong glass alembic sealed by cement ( adefrom wax, rosin, and powdered glass) hat has beenpoured very hot; soon, even in the cold, gas is stimulated, and the vessel, however strong, bursts into fragments.) From ''"De Flatibus"'' (On gases)

p. 408

: ''"Sal armeniacus enim, & aqua chrysulca, quae singula per se distillari, possunt, & pati calorem: sin autem jungantur, & intepescant, non possunt non, quin statim in Gas sylvestre, sive incoercibilem flatum transmutentur."'' (Truly Armenian salt .e., ammonium chlorideand nitric acid, each of which can be distilled by itself, and submitted to heat; but if, on the other hand, they be combined and become warm, they cannot but be changed immediately into carbon dioxide ote: van Helmont's identification of the gas is mistakenor an incondensable gas.)

See also:

Helmont, Johannes (Joan) Baptista Van, Encyclopedia.Com

: "Others were chlorine gas from the reaction of nitric acid and sal ammoniac; ... " * Wisniak, Jaime (2009) "Carl Wilhelm Scheele," ''Revista CENIC Ciencias Químicas'', 40 (3): 165–73; see p. 168: "Early in the seventeenth century Johannes Baptiste van Helmont (1579–1644) mentioned that when sal marin (sodium chloride) or sal ammoniacus and aqua chrysulca (nitric acid) were mixed together, a flatus incoercible (non-condensable gas) was evolved."

Isolation

The element was first studied in detail in 1774 by Swedish chemist

The element was first studied in detail in 1774 by Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (, ; 9 December 1742 – 21 May 1786) was a Swedish Pomerania, German-Swedish pharmaceutical chemist.

Scheele discovered oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first), and identified the elements molybd ...

, and he is credited with the discovery. Scheele produced chlorine by reacting MnO2 (as the mineral pyrolusite) with HCl:

:4 HCl + MnO2 → MnCl2 + 2 H2O + Cl2

Scheele observed several of the properties of chlorine: the bleaching effect on litmus, the deadly effect on insects, the yellow-green colour, and the smell similar to aqua regia

Aqua regia (; from Latin, "regal water" or "royal water") is a mixture of nitric acid and hydrochloric acid, optimally in a molar concentration, molar ratio of 1:3. Aqua regia is a fuming liquid. Freshly prepared aqua regia is colorless, but i ...

. He called it "''dephlogisticated muriatic acid air''" since it is a gas (then called "airs") and it came from hydrochloric acid (then known as "muriatic acid"). He failed to establish chlorine as an element.

Common chemical theory at that time held that an acid is a compound that contains oxygen (remnants of this survive in the German and Dutch names of oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

: or ', both translating into English as ''acid substance''), so a number of chemists, including Claude Berthollet, suggested that Scheele's ''dephlogisticated muriatic acid air'' must be a combination of oxygen and the yet undiscovered element, ''muriaticum''.

In 1809, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and Louis-Jacques Thénard tried to decompose ''dephlogisticated muriatic acid air'' by reacting it with charcoal to release the free element ''muriaticum'' (and carbon dioxide). They did not succeed and published a report in which they considered the possibility that ''dephlogisticated muriatic acid air'' is an element, but were not convinced.

In 1810, Sir Humphry Davy tried the same experiment again, and concluded that the substance was an element, and not a compound. He announced his results to the Royal Society on 15 November that year. At that time, he named this new element "chlorine", from the Greek word χλωρος (''chlōros'', "green-yellow"), in reference to its colour. The name " halogen", meaning "salt producer", was originally used for chlorine in 1811 by Johann Salomo Christoph Schweigger. This term was later used as a generic term to describe all the elements in the chlorine family (fluorine, bromine, iodine), after a suggestion by Jöns Jakob Berzelius in 1826. In 1823, Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English chemist and physicist who contributed to the study of electrochemistry and electromagnetism. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

liquefied chlorine for the first time, and demonstrated that what was then known as "solid chlorine" had a structure of chlorine hydrate (Cl2·H2O).

Later uses

Chlorine gas was first used by French chemist Claude Berthollet to bleach textiles in 1785. Modern bleaches resulted from further work by Berthollet, who first produced sodium hypochlorite in 1789 in his laboratory in the town of Javel (now part of Paris, France), by passing chlorine gas through a solution of sodium carbonate. The resulting liquid, known as "" (" Javel water"), was a weak solution of sodium hypochlorite. This process was not very efficient, and alternative production methods were sought. Scottish chemist and industrialist Charles Tennant first produced a solution of calcium hypochlorite ("chlorinated lime"), then solid calcium hypochlorite (bleaching powder). These compounds produced low levels of elemental chlorine and could be more efficiently transported than sodium hypochlorite, which remained as dilute solutions because when purified to eliminate water, it became a dangerously powerful and unstable oxidizer. Near the end of the nineteenth century, E. S. Smith patented a method of sodium hypochlorite production involving electrolysis of brine to producesodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly corrosive base (chemistry), ...

and chlorine gas, which then mixed to form sodium hypochlorite. This is known as the chloralkali process, first introduced on an industrial scale in 1892, and now the source of most elemental chlorine and sodium hydroxide. In 1884 Chemischen Fabrik Griesheim of Germany developed another chloralkali process which entered commercial production in 1888.

Elemental chlorine solutions dissolved in chemically basic water (sodium and calcium hypochlorite) were first used as anti-putrefaction

Putrefaction is the fifth stage of death, following pallor mortis, livor mortis, algor mortis, and rigor mortis. This process references the breaking down of a body of an animal Post-mortem interval, post-mortem. In broad terms, it can be view ...

agents and disinfectant

A disinfectant is a chemical substance or compound used to inactivate or destroy microorganisms on inert surfaces. Disinfection does not necessarily kill all microorganisms, especially resistant bacterial spores; it is less effective than ...

s in the 1820s, in France, long before the establishment of the germ theory of disease. This practice was pioneered by Antoine-Germain Labarraque, who adapted Berthollet's "Javel water" bleach and other chlorine preparations. Elemental chlorine has since served a continuous function in topical antisepsis (wound irrigation solutions and the like) and public sanitation, particularly in swimming and drinking water.

Chlorine gas was first used as a weapon on April 22, 1915, at the Second Battle of Ypres by the German Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

. The effect on the allies was devastating because the existing gas masks were difficult to deploy and had not been broadly distributed.

Properties

Chlorine is the second halogen, being a nonmetal in group 17 of the periodic table. Its properties are thus similar to

Chlorine is the second halogen, being a nonmetal in group 17 of the periodic table. Its properties are thus similar to fluorine

Fluorine is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol F and atomic number 9. It is the lightest halogen and exists at Standard temperature and pressure, standard conditions as pale yellow Diatomic molecule, diatomic gas. Fluorine is extre ...

, bromine

Bromine is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Br and atomic number 35. It is a volatile red-brown liquid at room temperature that evaporates readily to form a similarly coloured vapour. Its properties are intermediate between th ...

, and iodine, and are largely intermediate between those of the first two. Chlorine has the electron configuration es23p5, with the seven electrons in the third and outermost shell acting as its valence electrons. Like all halogens, it is thus one electron short of a full octet, and is hence a strong oxidising agent, reacting with many elements in order to complete its outer shell. Corresponding to periodic trends, it is intermediate in electronegativity

Electronegativity, symbolized as , is the tendency for an atom of a given chemical element to attract shared electrons (or electron density) when forming a chemical bond. An atom's electronegativity is affected by both its atomic number and the ...

between fluorine and bromine (F: 3.98, Cl: 3.16, Br: 2.96, I: 2.66), and is less reactive than fluorine and more reactive than bromine. It is also a weaker oxidising agent than fluorine, but a stronger one than bromine. Conversely, the chloride

The term chloride refers to a compound or molecule that contains either a chlorine anion (), which is a negatively charged chlorine atom, or a non-charged chlorine atom covalently bonded to the rest of the molecule by a single bond (). The pr ...

ion is a weaker reducing agent than bromide, but a stronger one than fluoride. It is intermediate in atomic radius between fluorine and bromine, and this leads to many of its atomic properties similarly continuing the trend from iodine to bromine upward, such as first ionisation energy, electron affinity, enthalpy of dissociation of the X2 molecule (X = Cl, Br, I), ionic radius, and X–X bond length. (Fluorine is anomalous due to its small size.)

All four stable halogens experience intermolecular van der Waals forces of attraction, and their strength increases together with the number of electrons among all homonuclear diatomic halogen molecules. Thus, the melting and boiling points of chlorine are intermediate between those of fluorine and bromine: chlorine melts at −101.0 °C and boils at −34.0 °C. As a result of the increasing molecular weight of the halogens down the group, the density and heats of fusion and vaporisation of chlorine are again intermediate between those of bromine and fluorine, although all their heats of vaporisation are fairly low (leading to high volatility) thanks to their diatomic molecular structure. The halogens darken in colour as the group is descended: thus, while fluorine is a pale yellow gas, chlorine is distinctly yellow-green. This trend occurs because the wavelengths of visible light absorbed by the halogens increase down the group. Specifically, the colour of a halogen, such as chlorine, results from the electron transition between the highest occupied antibonding ''πg'' molecular orbital and the lowest vacant antibonding ''σu'' molecular orbital. The colour fades at low temperatures, so that solid chlorine at −195 °C is almost colourless.

Like solid bromine and iodine, solid chlorine crystallises in the orthorhombic crystal system

In crystallography, the orthorhombic crystal system is one of the 7 crystal systems. Orthorhombic lattices result from stretching a cubic lattice along two of its orthogonal pairs by two different factors, resulting in a rectangular prism with ...

, in a layered lattice of Cl2 molecules. The Cl–Cl distance is 198 pm (close to the gaseous Cl–Cl distance of 199 pm) and the Cl···Cl distance between molecules is 332 pm within a layer and 382 pm between layers (compare the van der Waals radius of chlorine, 180 pm). This structure means that chlorine is a very poor conductor of electricity, and indeed its conductivity is so low as to be practically unmeasurable.

Isotopes

Chlorine has two stable isotopes, 35Cl and 37Cl. These are its only two natural isotopes occurring in quantity, with 35Cl making up 76% of natural chlorine and 37Cl making up the remaining 24%. Both are synthesised in stars in the oxygen-burning and silicon-burning processes. Both have nuclear spin 3/2+ and thus may be used for nuclear magnetic resonance, although the spin magnitude being greater than 1/2 results in non-spherical nuclear charge distribution and thus resonance broadening as a result of a nonzero nuclear quadrupole moment and resultant quadrupolar relaxation. The other chlorine isotopes are all radioactive, with half-lives too short to occur in nature primordially. Of these, the most commonly used in the laboratory are 36Cl (''t''1/2 = 3.0×105 y) and 38Cl (''t''1/2 = 37.2 min), which may be produced from the neutron activation of natural chlorine. The most stable chlorine radioisotope is 36Cl. The primary decay mode of isotopes lighter than 35Cl iselectron capture

Electron capture (K-electron capture, also K-capture, or L-electron capture, L-capture) is a process in which the proton-rich nucleus of an electrically neutral atom absorbs an inner atomic electron, usually from the K or L electron shells. Th ...

to isotopes of sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

; that of isotopes heavier than 37Cl is beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron), transforming into an isobar of that nuclide. For example, beta decay of a neutron ...

to isotopes of argon

Argon is a chemical element; it has symbol Ar and atomic number 18. It is in group 18 of the periodic table and is a noble gas. Argon is the third most abundant gas in Earth's atmosphere, at 0.934% (9340 ppmv). It is more than twice as abu ...

; and 36Cl may decay by either mode to stable 36S or 36Ar. 36Cl occurs in trace quantities in nature as a cosmogenic nuclide in a ratio of about (7–10) × 10−13 to 1 with stable chlorine isotopes: it is produced in the atmosphere by spallation of 36 Ar by interactions with cosmic ray

Cosmic rays or astroparticles are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the ...

proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , Hydron (chemistry), H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' (elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and approximately times the mass of an e ...

s. In the top meter of the lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the lithospheric mantle, the topmost portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time ...

, 36Cl is generated primarily by thermal neutron activation of 35Cl and spallation of 39 K and 40 Ca. In the subsurface environment, muon capture by 40 Ca becomes more important as a way to generate 36Cl.

Chemistry and compounds

Chlorine is intermediate in reactivity between fluorine and bromine, and is one of the most reactive elements. Chlorine is a weaker oxidising agent than fluorine but a stronger one than bromine or iodine. This can be seen from the standard electrode potentials of the X2/X− couples (F, +2.866 V; Cl, +1.395 V; Br, +1.087 V; I, +0.615 V; At, approximately +0.3 V). However, this trend is not shown in the bond energies because fluorine is singular due to its small size, low polarisability, and inability to show hypervalence. As another difference, chlorine has a significant chemistry in positive oxidation states while fluorine does not. Chlorination often leads to higher oxidation states than bromination or iodination but lower oxidation states than fluorination. Chlorine tends to react with compounds including M–M, M–H, or M–C bonds to form M–Cl bonds. Given that E°(O2/H2O) = +1.229 V, which is less than +1.395 V, it would be expected that chlorine should be able to oxidise water to oxygen and hydrochloric acid. However, the kinetics of this reaction are unfavorable, and there is also a bubble overpotential effect to consider, so that electrolysis of aqueous chloride solutions evolves chlorine gas and not oxygen gas, a fact that is very useful for the industrial production of chlorine.Hydrogen chloride

The simplest chlorine compound is

The simplest chlorine compound is hydrogen chloride

The Chemical compound, compound hydrogen chloride has the chemical formula and as such is a hydrogen halide. At room temperature, it is a colorless gas, which forms white fumes of hydrochloric acid upon contact with atmospheric water vapor. Hyd ...

, HCl, a major chemical in industry as well as in the laboratory, both as a gas and dissolved in water as hydrochloric acid. It is often produced by burning hydrogen gas in chlorine gas, or as a byproduct of chlorinating hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and Hydrophobe, hydrophobic; their odor is usually fain ...

s. Another approach is to treat sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as Salt#Edible salt, edible salt, is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. It is transparent or translucent, brittle, hygroscopic, and occurs a ...

with concentrated sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen, ...

to produce hydrochloric acid, also known as the "salt-cake" process:

:NaCl + H2SO4 NaHSO4 + HCl

:NaCl + NaHSO4 Na2SO4 + HCl

In the laboratory, hydrogen chloride gas may be made by drying the acid with concentrated sulfuric acid. Deuterium chloride, DCl, may be produced by reacting benzoyl chloride with heavy water

Heavy water (deuterium oxide, , ) is a form of water (molecule), water in which hydrogen atoms are all deuterium ( or D, also known as ''heavy hydrogen'') rather than the common hydrogen-1 isotope (, also called ''protium'') that makes up most o ...

(D2O).

At room temperature, hydrogen chloride is a colourless gas, like all the hydrogen halides apart from hydrogen fluoride, since hydrogen cannot form strong hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, Covalent bond, covalently b ...

s to the larger electronegative chlorine atom; however, weak hydrogen bonding is present in solid crystalline hydrogen chloride at low temperatures, similar to the hydrogen fluoride structure, before disorder begins to prevail as the temperature is raised. Hydrochloric acid is a strong acid (p''K''a = −7) because the hydrogen-chlorine bonds are too weak to inhibit dissociation. The HCl/H2O system has many hydrates HCl·''n''H2O for ''n'' = 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6. Beyond a 1:1 mixture of HCl and H2O, the system separates completely into two separate liquid phases. Hydrochloric acid forms an azeotrope

An azeotrope () or a constant heating point mixture is a mixture of two or more liquids whose proportions cannot be changed by simple distillation.Moore, Walter J. ''Physical Chemistry'', 3rd e Prentice-Hall 1962, pp. 140–142 This happens beca ...

with boiling point 108.58 °C at 20.22 g HCl per 100 g solution; thus hydrochloric acid cannot be concentrated beyond this point by distillation.

Unlike hydrogen fluoride, anhydrous liquid hydrogen chloride is difficult to work with as a solvent, because its boiling point is low, it has a small liquid range, its dielectric constant

The relative permittivity (in older texts, dielectric constant) is the permittivity of a material expressed as a ratio with the electric permittivity of a vacuum. A dielectric is an insulating material, and the dielectric constant of an insul ...

is low and it does not dissociate appreciably into H2Cl+ and ions – the latter, in any case, are much less stable than the bifluoride ions () due to the very weak hydrogen bonding between hydrogen and chlorine, though its salts with very large and weakly polarising cations such as Cs+ and (R = Me, Et, Bu''n'') may still be isolated. Anhydrous hydrogen chloride is a poor solvent, only able to dissolve small molecular compounds such as nitrosyl chloride and phenol

Phenol (also known as carbolic acid, phenolic acid, or benzenol) is an aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatile and can catch fire.

The molecule consists of a phenyl group () ...

, or salts with very low lattice energies such as tetraalkylammonium halides. It readily protonates nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

s containing lone-pairs or π bonds. Solvolysis

In chemistry, solvolysis is a type of nucleophilic substitution (S1/S2) or elimination reaction, elimination where the nucleophile is a solvent molecule. Characteristic of S1 reactions, solvolysis of a chirality (chemistry), chiral reactant affor ...

, ligand

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule with a functional group that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's el ...

replacement reactions, and oxidations are well-characterised in hydrogen chloride solution:

:Ph3SnCl + HCl ⟶ Ph2SnCl2 + PhH (solvolysis)

:Ph3COH + 3 HCl ⟶ + H3O+Cl− (solvolysis)

: + BCl3 ⟶ + HCl (ligand replacement)

:PCl3 + Cl2 + HCl ⟶ (oxidation)

Other binary chlorides

Nearly all elements in the periodic table form binary chlorides. The exceptions are decidedly in the minority and stem in each case from one of three causes: extreme inertness and reluctance to participate in chemical reactions (thenoble gas

The noble gases (historically the inert gases, sometimes referred to as aerogens) are the members of Group (periodic table), group 18 of the periodic table: helium (He), neon (Ne), argon (Ar), krypton (Kr), xenon (Xe), radon (Rn) and, in some ...

es, with the exception of xenon

Xenon is a chemical element; it has symbol Xe and atomic number 54. It is a dense, colorless, odorless noble gas found in Earth's atmosphere in trace amounts. Although generally unreactive, it can undergo a few chemical reactions such as the ...

in the highly unstable XeCl2 and XeCl4); extreme nuclear instability hampering chemical investigation before decay and transmutation (many of the heaviest elements beyond bismuth); and having an electronegativity higher than chlorine's (oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

and fluorine

Fluorine is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol F and atomic number 9. It is the lightest halogen and exists at Standard temperature and pressure, standard conditions as pale yellow Diatomic molecule, diatomic gas. Fluorine is extre ...

) so that the resultant binary compounds are formally not chlorides but rather oxides or fluorides of chlorine. Even though nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

in NCl3 is bearing a negative charge, the compound is usually called nitrogen trichloride.

Chlorination of metals with Cl2 usually leads to a higher oxidation state than bromination with Br2 when multiple oxidation states are available, such as in MoCl5 and MoBr3. Chlorides can be made by reaction of an element or its oxide, hydroxide, or carbonate with hydrochloric acid, and then dehydrated by mildly high temperatures combined with either low pressure or anhydrous hydrogen chloride gas. These methods work best when the chloride product is stable to hydrolysis; otherwise, the possibilities include high-temperature oxidative chlorination of the element with chlorine or hydrogen chloride, high-temperature chlorination of a metal oxide or other halide by chlorine, a volatile metal chloride, carbon tetrachloride, or an organic chloride. For instance, zirconium dioxide reacts with chlorine at standard conditions to produce zirconium tetrachloride, and uranium trioxide reacts with hexachloropropene when heated under reflux to give uranium tetrachloride. The second example also involves a reduction in oxidation state

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical Electrical charge, charge of an atom if all of its Chemical bond, bonds to other atoms are fully Ionic bond, ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons ...

, which can also be achieved by reducing a higher chloride using hydrogen or a metal as a reducing agent. This may also be achieved by thermal decomposition or disproportionation as follows:

: EuCl3 + H2 ⟶ EuCl2 + HCl

: ReCl5 ReCl3 + Cl2

: AuCl3 AuCl + Cl2

Most metal chlorides with the metal in low oxidation states (+1 to +3) are ionic. Nonmetals tend to form covalent molecular chlorides, as do metals in high oxidation states from +3 and above. Both ionic and covalent chlorides are known for metals in oxidation state +3 (e.g. scandium chloride is mostly ionic, but aluminium chloride is not). Silver chloride is very insoluble in water and is thus often used as a qualitative test for chlorine.

Polychlorine compounds

Although dichlorine is a strong oxidising agent with a high first ionisation energy, it may be oxidised under extreme conditions to form the cation. This is very unstable and has only been characterised by its electronic band spectrum when produced in a low-pressure discharge tube. The yellow cation is more stable and may be produced as follows: : This reaction is conducted in the oxidising solvent arsenic pentafluoride. The trichloride anion, , has also been characterised; it is analogous to triiodide.Chlorine fluorides

The three fluorides of chlorine form a subset of the interhalogen compounds, all of which are diamagnetic. Some cationic and anionic derivatives are known, such as , , , and Cl2F+. Some pseudohalides of chlorine are also known, such as cyanogen chloride (ClCN, linear), chlorine cyanate (ClNCO), chlorine thiocyanate (ClSCN, unlike its oxygen counterpart), and chlorine azide (ClN3). Chlorine monofluoride (ClF) is extremely thermally stable, and is sold commercially in 500-gram steel lecture bottles. It is a colourless gas that melts at −155.6 °C and boils at −100.1 °C. It may be produced by the reaction of its elements at 225 °C, though it must then be separated and purified from chlorine trifluoride and its reactants. Its properties are mostly intermediate between those of chlorine and fluorine. It will react with many metals and nonmetals from room temperature and above, fluorinating them and liberating chlorine. It will also act as a chlorofluorinating agent, adding chlorine and fluorine across a multiple bond or by oxidation: for example, it will attackcarbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

to form carbonyl chlorofluoride, COFCl. It will react analogously with hexafluoroacetone, (CF3)2CO, with a potassium fluoride catalyst to produce heptafluoroisopropyl hypochlorite, (CF3)2CFOCl; with nitriles RCN to produce RCF2NCl2; and with the sulfur oxides SO2 and SO3 to produce ClSO2F and ClOSO2F respectively. It will also react exothermically with compounds containing –OH and –NH groups, such as water:

:H2O + 2 ClF ⟶ 2 HF + Cl2O

Chlorine trifluoride (ClF3) is a volatile colourless molecular liquid which melts at −76.3 °C and boils at 11.8 °C. It may be formed by directly fluorinating gaseous chlorine or chlorine monofluoride at 200–300 °C. One of the most reactive chemical compounds known, the list of elements it sets on fire is diverse, containing hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

, potassium

Potassium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol K (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to ...

, phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol P and atomic number 15. All elemental forms of phosphorus are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive and are therefore never found in nature. They can nevertheless be prepared ar ...

, arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol As and atomic number 33. It is a metalloid and one of the pnictogens, and therefore shares many properties with its group 15 neighbors phosphorus and antimony. Arsenic is not ...

, antimony

Antimony is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Sb () and atomic number 51. A lustrous grey metal or metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient t ...

, sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

, selenium

Selenium is a chemical element; it has symbol (chemistry), symbol Se and atomic number 34. It has various physical appearances, including a brick-red powder, a vitreous black solid, and a grey metallic-looking form. It seldom occurs in this elem ...

, tellurium, bromine

Bromine is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Br and atomic number 35. It is a volatile red-brown liquid at room temperature that evaporates readily to form a similarly coloured vapour. Its properties are intermediate between th ...

, iodine, and powdered molybdenum

Molybdenum is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mo (from Neo-Latin ''molybdaenum'') and atomic number 42. The name derived from Ancient Greek ', meaning lead, since its ores were confused with lead ores. Molybdenum minerals hav ...

, tungsten, rhodium, iridium, and iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

. It will also ignite water, along with many substances which in ordinary circumstances would be considered chemically inert such as asbestos, concrete, glass, and sand. When heated, it will even corrode noble metal

A noble metal is ordinarily regarded as a metallic chemical element, element that is generally resistant to corrosion and is usually found in nature in its native element, raw form. Gold, platinum, and the other platinum group metals (ruthenium ...

s as palladium, platinum

Platinum is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a density, dense, malleable, ductility, ductile, highly unreactive, precious metal, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name origina ...

, and gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

, and even the noble gas

The noble gases (historically the inert gases, sometimes referred to as aerogens) are the members of Group (periodic table), group 18 of the periodic table: helium (He), neon (Ne), argon (Ar), krypton (Kr), xenon (Xe), radon (Rn) and, in some ...

es xenon

Xenon is a chemical element; it has symbol Xe and atomic number 54. It is a dense, colorless, odorless noble gas found in Earth's atmosphere in trace amounts. Although generally unreactive, it can undergo a few chemical reactions such as the ...

and radon do not escape fluorination. An impermeable fluoride layer is formed by sodium

Sodium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Na (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 element, group 1 of the peri ...

, magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 ...

, aluminium

Aluminium (or aluminum in North American English) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Al and atomic number 13. It has a density lower than that of other common metals, about one-third that of steel. Aluminium has ...

, zinc

Zinc is a chemical element; it has symbol Zn and atomic number 30. It is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodic tabl ...

, tin, and silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

, which may be removed by heating. Nickel, copper, and steel containers are usually used due to their great resistance to attack by chlorine trifluoride, stemming from the formation of an unreactive layer of metal fluoride. Its reaction with hydrazine

Hydrazine is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a simple pnictogen hydride, and is a colourless flammable liquid with an ammonia-like odour. Hydrazine is highly hazardous unless handled in solution as, for example, hydraz ...

to form hydrogen fluoride, nitrogen, and chlorine gases was used in experimental rocket engine, but has problems largely stemming from its extreme hypergolicity resulting in ignition without any measurable delay. Today, it is mostly used in nuclear fuel processing, to oxidise uranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

to uranium hexafluoride for its enriching and to separate it from plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

, as well as in the semiconductor industry, where it is used to clean chemical vapor deposition chambers. It can act as a fluoride ion donor or acceptor (Lewis base or acid), although it does not dissociate appreciably into and ions.

Chlorine pentafluoride (ClF5) is made on a large scale by direct fluorination of chlorine with excess fluorine

Fluorine is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol F and atomic number 9. It is the lightest halogen and exists at Standard temperature and pressure, standard conditions as pale yellow Diatomic molecule, diatomic gas. Fluorine is extre ...

gas at 350 °C and 250 atm, and on a small scale by reacting metal chlorides with fluorine gas at 100–300 °C. It melts at −103 °C and boils at −13.1 °C. It is a very strong fluorinating agent, although it is still not as effective as chlorine trifluoride. Only a few specific stoichiometric reactions have been characterised. Arsenic pentafluoride and antimony pentafluoride form ionic adducts of the form lF4sup>+ F6sup>− (M = As, Sb) and water reacts vigorously as follows:

:2 H2O + ClF5 ⟶ 4 HF + FClO2

The product, chloryl fluoride, is one of the five known chlorine oxide fluorides. These range from the thermally unstable FClO to the chemically unreactive perchloryl fluoride (FClO3), the other three being FClO2, F3ClO, and F3ClO2. All five behave similarly to the chlorine fluorides, both structurally and chemically, and may act as Lewis acids or bases by gaining or losing fluoride ions respectively or as very strong oxidising and fluorinating agents.

Chlorine oxides

The chlorine oxides are well-studied in spite of their instability (all of them are endothermic compounds). They are important because they are produced when

The chlorine oxides are well-studied in spite of their instability (all of them are endothermic compounds). They are important because they are produced when chlorofluorocarbon

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) are fully or partly Halogenation, halogenated hydrocarbons that contain carbon (C), hydrogen (H), chlorine (Cl), and fluorine (F). They are produced as volatility (chemistry), volat ...

s undergo photolysis in the upper atmosphere and cause the destruction of the ozone layer. None of them can be made from directly reacting the elements.

Dichlorine monoxide (Cl2O) is a brownish-yellow gas (red-brown when solid or liquid) which may be obtained by reacting chlorine gas with yellow mercury(II) oxide. It is very soluble in water, in which it is in equilibrium with hypochlorous acid (HOCl), of which it is the anhydride. It is thus an effective bleach and is mostly used to make hypochlorites. It explodes on heating or sparking or in the presence of ammonia gas.

Chlorine dioxide

Chlorine dioxide is a chemical compound with the formula ClO2 that exists as yellowish-green gas above 11 °C, a reddish-brown liquid between 11 °C and −59 °C, and as bright orange crystals below −59 °C. It is usually ...

(ClO2) was the first chlorine oxide to be discovered in 1811 by Humphry Davy. It is a yellow paramagnetic gas (deep-red as a solid or liquid), as expected from its having an odd number of electrons: it is stable towards dimerisation due to the delocalisation of the unpaired electron. It explodes above −40 °C as a liquid and under pressure as a gas and therefore must be made at low concentrations for wood-pulp bleaching and water treatment. It is usually prepared by reducing a chlorate as follows:

: + Cl− + 2 H+ ⟶ ClO2 + Cl2 + H2O

Its production is thus intimately linked to the redox reactions of the chlorine oxoacids. It is a strong oxidising agent, reacting with sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

, phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol P and atomic number 15. All elemental forms of phosphorus are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive and are therefore never found in nature. They can nevertheless be prepared ar ...

, phosphorus halides, and potassium borohydride. It dissolves exothermically in water to form dark-green solutions that very slowly decompose in the dark. Crystalline clathrate hydrates ClO2·''n''H2O (''n'' ≈ 6–10) separate out at low temperatures. However, in the presence of light, these solutions rapidly photodecompose to form a mixture of chloric and hydrochloric acids. Photolysis of individual ClO2 molecules result in the radicals ClO and ClOO, while at room temperature mostly chlorine, oxygen, and some ClO3 and Cl2O6 are produced. Cl2O3 is also produced when photolysing the solid at −78 °C: it is a dark brown solid that explodes below 0 °C. The ClO radical leads to the depletion of atmospheric ozone and is thus environmentally important as follows:

:Cl• + O3 ⟶ ClO• + O2

:ClO• + O• ⟶ Cl• + O2

Chlorine perchlorate (ClOClO3) is a pale yellow liquid that is less stable than ClO2 and decomposes at room temperature to form chlorine, oxygen, and dichlorine hexoxide (Cl2O6). Chlorine perchlorate may also be considered a chlorine derivative of perchloric acid (HOClO3), similar to the thermally unstable chlorine derivatives of other oxoacids: examples include chlorine nitrate (ClONO2, vigorously reactive and explosive), and chlorine fluorosulfate (ClOSO2F, more stable but still moisture-sensitive and highly reactive). Dichlorine hexoxide is a dark-red liquid that freezes to form a solid which turns yellow at −180 °C: it is usually made by reaction of chlorine dioxide with oxygen. Despite attempts to rationalise it as the dimer of ClO3, it reacts more as though it were chloryl perchlorate, lO2sup>+ lO4sup>−, which has been confirmed to be the correct structure of the solid. It hydrolyses in water to give a mixture of chloric and perchloric acids: the analogous reaction with anhydrous hydrogen fluoride does not proceed to completion.

Dichlorine heptoxide (Cl2O7) is the anhydride of perchloric acid (HClO4) and can readily be obtained from it by dehydrating it with phosphoric acid

Phosphoric acid (orthophosphoric acid, monophosphoric acid or phosphoric(V) acid) is a colorless, odorless phosphorus-containing solid, and inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is commonly encountered as an 85% aqueous solution, ...

at −10 °C and then distilling the product at −35 °C and 1 mmHg. It is a shock-sensitive, colourless oily liquid. It is the least reactive of the chlorine oxides, being the only one to not set organic materials on fire at room temperature. It may be dissolved in water to regenerate perchloric acid or in aqueous alkalis to regenerate perchlorates. However, it thermally decomposes explosively by breaking one of the central Cl–O bonds, producing the radicals ClO3 and ClO4 which immediately decompose to the elements through intermediate oxides.

Chlorine oxoacids and oxyanions

Chlorine forms four oxoacids: hypochlorous acid (HOCl), chlorous acid (HOClO), chloric acid (HOClO2), and perchloric acid (HOClO3). As can be seen from the redox potentials given in the adjacent table, chlorine is much more stable towards disproportionation in acidic solutions than in alkaline solutions: : The hypochlorite ions also disproportionate further to produce chloride and chlorate (3 ClO− 2 Cl− + ) but this reaction is quite slow at temperatures below 70 °C in spite of the very favourable equilibrium constant of 1027. The chlorate ions may themselves disproportionate to form chloride and perchlorate (4 Cl− + 3 ) but this is still very slow even at 100 °C despite the very favourable equilibrium constant of 1020. The rates of reaction for the chlorine oxyanions increases as the oxidation state of chlorine decreases. The strengths of the chlorine oxyacids increase very quickly as the oxidation state of chlorine increases due to the increasing delocalisation of charge over more and more oxygen atoms in their conjugate bases. Most of the chlorine oxoacids may be produced by exploiting these disproportionation reactions. Hypochlorous acid (HOCl) is highly reactive and quite unstable; its salts are mostly used for their bleaching and sterilising abilities. They are very strong oxidising agents, transferring an oxygen atom to most inorganic species. Chlorous acid (HOClO) is even more unstable and cannot be isolated or concentrated without decomposition: it is known from the decomposition of aqueous chlorine dioxide. However, sodium chlorite is a stable salt and is useful for bleaching and stripping textiles, as an oxidising agent, and as a source of chlorine dioxide. Chloric acid (HOClO2) is a strong acid that is quite stable in cold water up to 30% concentration, but on warming gives chlorine and chlorine dioxide. Evaporation under reduced pressure allows it to be concentrated further to about 40%, but then it decomposes to perchloric acid, chlorine, oxygen, water, and chlorine dioxide. Its most important salt is sodium chlorate, mostly used to make chlorine dioxide to bleach paper pulp. The decomposition of chlorate to chloride and oxygen is a common way to produce oxygen in the laboratory on a small scale. Chloride and chlorate may comproportionate to form chlorine as follows: : + 5 Cl− + 6 H+ ⟶ 3 Cl2 + 3 H2O Perchlorates and perchloric acid (HOClO3) are the most stable oxo-compounds of chlorine, in keeping with the fact that chlorine compounds are most stable when the chlorine atom is in its lowest (−1) or highest (+7) possible oxidation states. Perchloric acid and aqueous perchlorates are vigorous and sometimes violent oxidising agents when heated, in stark contrast to their mostly inactive nature at room temperature due to the high activation energies for these reactions for kinetic reasons. Perchlorates are made by electrolytically oxidising sodium chlorate, and perchloric acid is made by reacting anhydrous sodium perchlorate or barium perchlorate with concentrated hydrochloric acid, filtering away the chloride precipitated and distilling the filtrate to concentrate it. Anhydrous perchloric acid is a colourless mobile liquid that is sensitive to shock that explodes on contact with most organic compounds, sets hydrogen iodide and thionyl chloride on fire and even oxidises silver and gold. Although it is a weak ligand, weaker than water, a few compounds involving coordinated are known. The Table below presents typical oxidation states for chlorine element as given in the secondary schools or colleges. There are more complex chemical compounds, the structure of which can only be explained using modern quantum chemical methods, for example, cluster technetium chloride CH3)4Nsub>3 c6Cl14 in which 6 of the 14 chlorine atoms are formally divalent, and oxidation states are fractional. In addition, all the above chemical regularities are valid for "normal" or close to normal conditions, while at ultra-high pressures (for example, in the cores of large planets), chlorine can form a Na3Cl compound with sodium, which does not fit into traditional concepts of chemistry.Organochlorine compounds

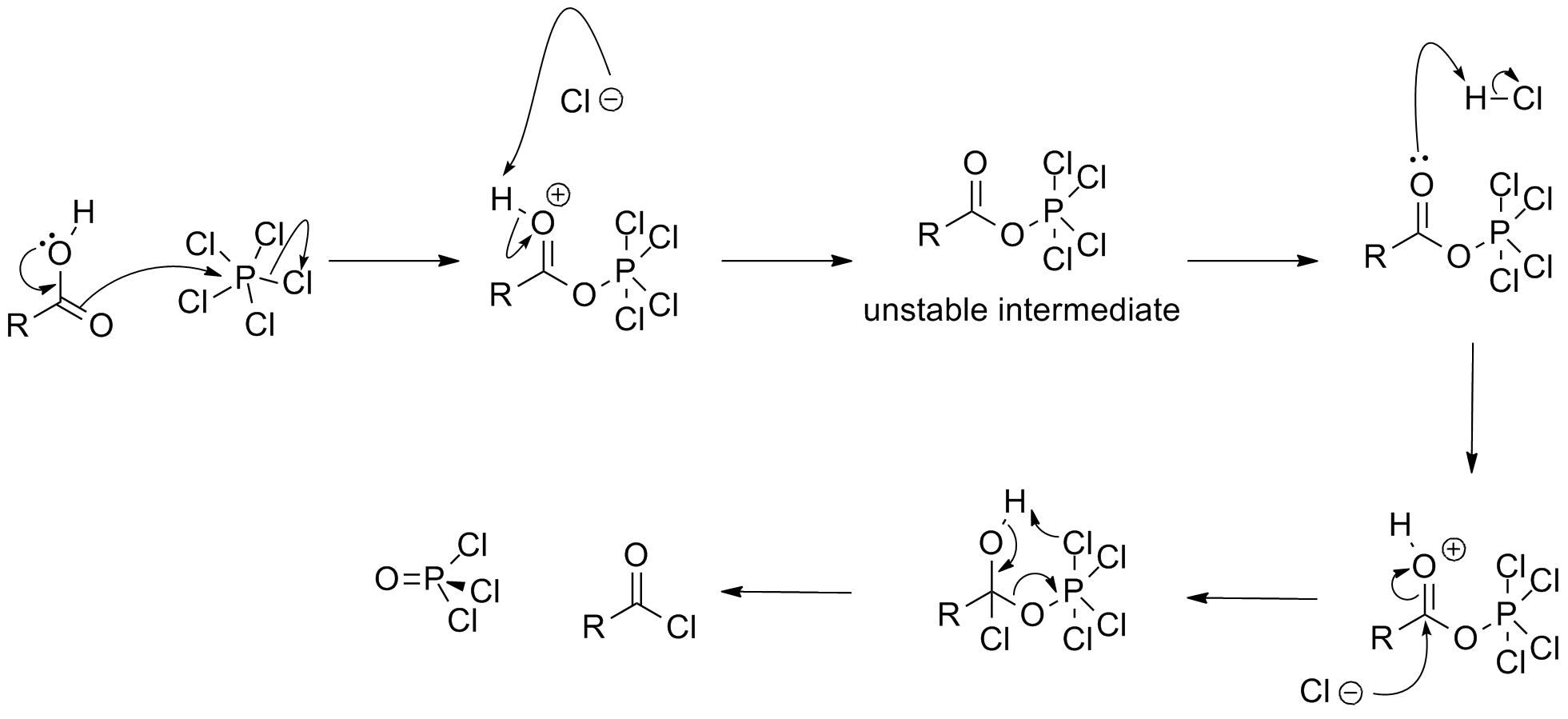

Like the other carbon–halogen bonds, the C–Cl bond is a common functional group that forms part of core

Like the other carbon–halogen bonds, the C–Cl bond is a common functional group that forms part of core organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic matter, organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain ...

. Formally, compounds with this functional group may be considered organic derivatives of the chloride anion. Due to the difference of electronegativity between chlorine (3.16) and carbon (2.55), the carbon in a C–Cl bond is electron-deficient and thus electrophilic. Chlorination modifies the physical properties of hydrocarbons in several ways: chlorocarbons are typically denser than water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

due to the higher atomic weight of chlorine versus hydrogen, and aliphatic organochlorides are alkylating agents because chloride is a leaving group.M. Rossberg et al. "Chlorinated Hydrocarbons" in ''Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry'' 2006, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim.

Alkanes and aryl alkanes may be chlorinated under free-radical conditions, with UV light. However, the extent of chlorination is difficult to control: the reaction is not regioselective and often results in a mixture of various isomers with different degrees of chlorination, though this may be permissible if the products are easily separated. Aryl chlorides may be prepared by the Friedel-Crafts halogenation, using chlorine and a Lewis acid catalyst. The haloform reaction, using chlorine and sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly corrosive base (chemistry), ...

, is also able to generate alkyl halides from methyl ketones, and related compounds. Chlorine adds to the multiple bonds on alkenes and alkynes as well, giving di- or tetrachloro compounds. However, due to the expense and reactivity of chlorine, organochlorine compounds are more commonly produced by using hydrogen chloride, or with chlorinating agents such as phosphorus pentachloride (PCl5) or thionyl chloride (SOCl2). The last is very convenient in the laboratory because all side products are gaseous and do not have to be distilled out.

Many organochlorine compounds have been isolated from natural sources ranging from bacteria to humans. Chlorinated organic compounds are found in nearly every class of biomolecules including alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

s, terpene

Terpenes () are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n ≥ 2. Terpenes are major biosynthetic building blocks. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predomi ...

s, amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s, flavonoid

Flavonoids (or bioflavonoids; from the Latin word ''flavus'', meaning yellow, their color in nature) are a class of polyphenolic secondary metabolites found in plants, and thus commonly consumed in the diets of humans.

Chemically, flavonoids ...

s, steroid

A steroid is an organic compound with four fused compound, fused rings (designated A, B, C, and D) arranged in a specific molecular configuration.

Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes t ...

s, and fatty acid

In chemistry, in particular in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated and unsaturated compounds#Organic chemistry, saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an ...

s. Organochlorides, including dioxins, are produced in the high temperature environment of forest fires, and dioxins have been found in the preserved ashes of lightning-ignited fires that predate synthetic dioxins. In addition, a variety of simple chlorinated hydrocarbons including dichloromethane, chloroform, and carbon tetrachloride have been isolated from marine algae. A majority of the chloromethane in the environment is produced naturally by biological decomposition, forest fires, and volcanoes.

Some types of organochlorides, though not all, have significant toxicity to plants or animals, including humans. Dioxins, produced when organic matter is burned in the presence of chlorine, and some insecticide

Insecticides are pesticides used to kill insects. They include ovicides and larvicides used against insect eggs and larvae, respectively. The major use of insecticides is in agriculture, but they are also used in home and garden settings, i ...

s, such as DDT, are persistent organic pollutants which pose dangers when they are released into the environment. For example, DDT, which was widely used to control insects in the mid 20th century, also accumulates in food chains, and causes reproductive problems (e.g., eggshell thinning) in certain bird species. Due to the ready homolytic fission of the C–Cl bond to create chlorine radicals in the upper atmosphere, chlorofluorocarbon

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) are fully or partly Halogenation, halogenated hydrocarbons that contain carbon (C), hydrogen (H), chlorine (Cl), and fluorine (F). They are produced as volatility (chemistry), volat ...

s have been phased out due to the harm they do to the ozone layer.

Occurrence

Chlorine is too reactive to occur as the free element in nature but is very abundant in the form of its chloride salts. It is the 20th most abundant element in Earth's crust and makes up 126

Chlorine is too reactive to occur as the free element in nature but is very abundant in the form of its chloride salts. It is the 20th most abundant element in Earth's crust and makes up 126 parts per million

In science and engineering, the parts-per notation is a set of pseudo-units to describe the small values of miscellaneous dimensionless quantity, dimensionless quantities, e.g. mole fraction or mass fraction (chemistry), mass fraction.

Since t ...

of it, through the large deposits of chloride minerals, especially sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as Salt#Edible salt, edible salt, is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. It is transparent or translucent, brittle, hygroscopic, and occurs a ...

, that have been evaporated from water bodies. All of these pale in comparison to the reserves of chloride ions in seawater: smaller amounts at higher concentrations occur in some inland seas and underground brine wells, such as the Great Salt Lake in Utah and the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea (; or ; ), also known by #Names, other names, is a landlocked salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east, the Israeli-occupied West Bank to the west and Israel to the southwest. It lies in the endorheic basin of the Jordan Rift Valle ...

in Israel.

Small batches of chlorine gas are prepared in the laboratory by combining hydrochloric acid and manganese dioxide, but the need rarely arises due to its ready availability. In industry, elemental chlorine is usually produced by the electrolysis of sodium chloride dissolved in water. This method, the chloralkali process industrialized in 1892, now provides most industrial chlorine gas. Along with chlorine, the method yields hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

gas and sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly corrosive base (chemistry), ...

, which is the most valuable product. The process proceeds according to the following chemical equation

A chemical equation is the symbolic representation of a chemical reaction in the form of symbols and chemical formulas. The reactant entities are given on the left-hand side and the Product (chemistry), product entities are on the right-hand side ...

:

:2 NaCl + 2 H2O → Cl2 + H2 + 2 NaOH

Production

Chlorine is primarily produced by the chloralkali process, although non-chloralkali processes exist. Global 2022 production was estimated to be 97 million tonnes. The most visible use of chlorine is in water disinfection. 35-40 % of chlorine produced is used to make poly(vinyl chloride) through ethylene dichloride and vinyl chloride. The chlorine produced is available in cylinders from sizes ranging from 450 g to 70 kg, as well as drums (865 kg), tank wagons (15 tonnes on roads; 27–90 tonnes by rail), and barges (600–1200 tonnes). Due to the difficulty and hazards in transporting elemental chlorine, production is typically located near where it is consumed. As examples, vinyl chloride producers such as Westlake Chemical and Formosa Plastics have integrated chloralkali assets.Chloralkali processes

The electrolysis of chloride solutions all proceed according to the following equations: :Cathode: 2 H2O + 2 e− → H2 + 2 OH− :Anode: 2 Cl− → Cl2 + 2 e− In the conventional case where sodium chloride is electrolyzed,sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly corrosive base (chemistry), ...

and chlorine are coproducts.

Industrially, there are three chloralkali processes:

* The Castner–Kellner process

The Castner–Kellner process is a method of electrolysis on an aqueous alkali chloride solution (usually sodium chloride solution) to produce the corresponding alkali hydroxide, invented by American Hamilton Castner and Austrian Carl Kellner (mys ...

that utilizes a mercury electrode