Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

has been practiced in

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

since about the 6th century CE.

Japanese Buddhism () created many new

Buddhist schools, and some schools are original to Japan and some are derived from

Chinese Buddhist schools. Japanese Buddhism has had a major influence on

Japanese society and culture and remains an influential aspect to this day.

[Asia Societ]

Buddhism in Japan

accessed July 2012

According to the

Japanese Government

The Government of Japan consists of legislative, executive and judiciary branches and is based on popular sovereignty. The Government runs under the framework established by the Constitution of Japan, adopted in 1947. It is a unitary state, c ...

's

Agency for Cultural Affairs

The is a special body of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). It was set up in 1968 to promote Japanese arts and culture.

The agency's budget for FY 2018 rose to ¥107.7 billion.

Overview

The ag ...

estimate, , with about 84 million or about 67% of the

Japanese population, Buddhism was the

religion in Japan with the second most adherents, next to

Shinto, though a large number of people practice elements of both.

According to the statistics by the Agency for Cultural Affairs in 2021, the

religious corporation under the jurisdiction of the

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology

The , also known as MEXT or Monka-shō, is one of the eleven Ministries of Japan that composes part of the executive branch of the Government of Japan. Its goal is to improve the development of Japan in relation with the international community ...

in Japan had 135 million believers, of which 47 million were Buddhists and most of them were believers of new schools of Buddhism which were established in the

Kamakura period

The is a period of Japanese history that marks the governance by the Kamakura shogunate, officially established in 1192 in Kamakura by the first ''shōgun'' Minamoto no Yoritomo after the conclusion of the Genpei War, which saw the struggle betwee ...

(1185-1333).

According to these statistics, the largest sects of Japanese Buddhism are the

Jōdo Buddhists with 22 million believers, followed by the

Nichiren Buddhists with 11 million believers.

There are a wide range of estimates, however; the

Pew Research Center

The Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan American think tank (referring to itself as a "fact tank") based in Washington, D.C.

It provides information on social issues, public opinion, and demographic trends shaping the United States and the w ...

estimated 36.2% of the population in 2010 practiced Buddhism.

The Japanese General Social Survey places the figure at less than 20% of the population in 2017, and along with the 2013 Japanese National Character Survey, shows that roughly 70% of the population do not adhere to any religious beliefs.

Another survey indicates that about 60% of the Japanese have a

Butsudan (Buddhist shrine) in their homes. According to a Pew Research study from 2012, Japan has the

third largest Buddhist population in the world, after

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

and

Thailand.

History

Arrival and initial spread of Buddhism

Buddhism arrived in Japan by first

making its way to China and Korea through the Silk Road and then traveling by sea to the

Japanese archipelago. As such, early Japanese Buddhism is strongly influenced by

Chinese Buddhism

Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism ( zh, s=汉传佛教, t=漢傳佛教, p=Hànchuán Fójiào) is a Chinese form of Mahayana Buddhism which has shaped Chinese culture in a wide variety of areas including art, politics, literature, philosophy ...

and

Korean Buddhism

Korean Buddhism is distinguished from other forms of Buddhism by its attempt to resolve what its early practitioners saw as inconsistencies within the Mahayana Buddhist traditions that they received from foreign countries. To address this, the ...

. Though the "official" introduction of Buddhism to the country occurred at some point in the middle of the sixth century, there were likely earlier contacts and attempts to introduce the religion. Immigrants from the Korean Peninsula, as well as merchants and sailors who frequented the mainland, likely brought Buddhism with them independent of the transmission as recorded in court chronicles. Some Japanese sources mention this explicitly. For example, the

Heian Period ''Fusō ryakki'' (Abridged Annals of Japan), mentions a foreigner known in Japanese as Shiba no Tatsuto, who may have been Chinese-born,

Baekje-born, or a descendent of an immigrant group in Japan. He is said to have built a thatched hut in Yamato and enshrined an object of worship there. Immigrants like this may have been a source for the Soga clan's later sponsorship of Buddhism.

The ''

Nihon Shoki'' (''Chronicles of Japan'') provides a date of 552 for when King

Seong

Seong, also spelled Song or Sung, is an uncommon Korean family name, a single-syllable Korean given name, as well as a common element in two-syllable Korean given names. The meaning differs based on the hanja used to write it.

Family name

The ...

of

Baekje (now western

South Korea) sent a mission to

Emperor Kinmei

was the 29th Emperor of Japan, Imperial Household Agency (''Kunaichō'') 欽明天皇 (29) retrieved 2013-8-22. according to the traditional order of succession. Titsingh, Isaac. (1834)pp. 34–36 Brown, Delmer. (1979) ''Gukanshō,'' pp. 261– ...

that included an image of the

Buddha Shakyamuni, ritual banners, and

sutra

''Sutra'' ( sa, सूत्र, translit=sūtra, translit-std=IAST, translation=string, thread)Monier Williams, ''Sanskrit English Dictionary'', Oxford University Press, Entry fo''sutra'' page 1241 in Indian literary traditions refers to an aph ...

s. This event is usually considered the official introduction of Buddhism to Japan.

Other sources, however, give the date of 538 and both dates are thought to be unreliable. However, it can still be said that in the middle of the sixth century, Buddhism was introduced through official diplomatic channels.

According to the ''Nihon Shoki'', after receiving the Buddhist gifts, the Japanese emperor asked his officials if the Buddha should be worshipped in Japan. They were divided on the issue, with

Soga no Iname (506–570) supporting the idea while

Mononobe no Okoshi and Nakatomi no Kamako worried that the

kami of Japan would become angry at this worship of a foreign deity. The ''Nihon Shoki'' then states that the emperor allowed only the Soga clan to worship the Buddha, to test it out.

Thus, the powerful

Soga clan played a key role in the early spread of Buddhism in the country. Their support, along with that of immigrant groups like the

Hata clan, gave Buddhism its initial impulse in Japan along with its first temple (Hōkō-ji, also known as

Asukadera). The Nakatomi and Mononobe, however, continued to oppose the Soga, blaming their worship for disease and disorder. These opponents of Buddhism are even said to have thrown the image of the Buddha into the Naniwa canal. Eventually outright war erupted. The Soga side, led by

Soga no Umako and a young

Prince Shōtoku, emerged victorious and promoted Buddhism on the archipelago with support of the broader court.

Based on traditional sources, Shōtoku has been seen as an ardent Buddhist who taught, wrote on, and promoted Buddhism widely, especially during the reign of

Empress Suiko (554 – 15 April 628). He is also believed to have sent envoys to China and is even seen as a spiritually accomplished

bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schoo ...

who is the true founder of Japanese Buddhism. Modern historians have questioned much of this, seeing most of it as a constructed hagiography. Regardless of his actual historical role, however, it is beyond doubt that Shōtoku became an important figure in Japanese Buddhist lore beginning soon after his death if not earlier.

Asuka Buddhism (552–645)

Asuka-period

Asuka-period Buddhism (''Asuka bukkyō'') refers to Buddhist practice and thought that mainly developed after 552 in the

Nara Basin region. Buddhism grew here through the support and efforts of two main groups: immigrant kinship groups like the Hata clan (who were experts in Chinese technology as well as intellectual and material culture), and through aristocratic clans like the Soga.

Immigrant groups like the Korean monks who supposedly instructed Shōtoku introduced Buddhist learning, administration, ritual practice and the skills to build Buddhist art and architecture. They included individuals like

Ekan

Hyegwan (Japanese: was a priest who came across the sea from Goguryeo to Japan in the Asuka period. He is known for introducing the Chinese Buddhist school of Sanlun to Japan.

Hyegwan studied under Jizang and learned Sanron. In 625 (the 33rd ye ...

(dates unknown), a

Koguryŏ priest of the Madhyamaka school, who (according to the ''Nihon Shoki'') was appointed to the highest rank of primary monastic prelate (''sōjō'').

Aside from the Buddhist immigrant groups, Asuka Buddhism was mainly the purview of aristocratic groups like the Soga clan and other related clans, who patronized clan temples as a way to express their power and influence. These temples mainly focused on the performance of rituals which were believed to provide magical effects, such as protection.

[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 32-34.] During this period, Buddhist art was dominated by the style of

Tori Busshi, who came from a Korean immigrant family.

Hakuhō Buddhism (645–710)

Hakuhō Buddhism (Hakuhō refers to

Emperor Tenmu

was the 40th emperor of Japan, Imperial Household Agency (''Kunaichō'') 天武天皇 (40) retrieved 2013-8-22. according to the traditional order of succession. Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1959). ''The Imperial House of Japan'', p. 53.

Tenmu's re ...

) saw the official patronage of Buddhism being taken up by the Japanese imperial family, who replaced the Soga clan as the main patrons of Buddhism. Japanese Buddhism at this time was also influenced by Tang dynasty (618–907) Buddhism.

[Deal & Ruppert (2015) p. 45] It was also during this time that Buddhism began to spread from the

Yamato Province to the other regions and islands of Japan.

An important part of the centralizing reforms of this era (the

Taika reforms) was the use of Buddhist institutions and rituals (often performed at the palace or capital) in the service of the state.

The imperial government also actively built and managed the Buddhist temples as well as the monastic community. The Nihon Shoki states that in 624 there were 46 Buddhist temples. Some of these temples include

Kawaradera and

Yakushiji. Archeological research has also revealed numerous local and regional temples outside of the capital. At the state temples, Buddhist rituals were performed in order to create merit for the royal family and the well-being of the nation. Particular attention was paid to rituals centered around Buddhist sutras (scriptures), such as the ''

Golden Light Sutra''. The monastic community was overseen by the complex and hierarchical imperial Monastic Office (''sōgō''), who managed everything from the monastic code to the color of the robes.

Nara Buddhism (710–794)

In 710,

Empress Genme moved the state capital to

Heijōkyō, (modern

Nara) thus inaugurating the

Nara period. This period saw the establishment of the

''kokubunji'' system, which was a way to manage provincial temples through a network of national temples in each province. The head temple of the entire system was

Tōdaiji.

Nara state sponsorship saw the development of the six great Nara schools, called , all were continuations of Chinese Buddhist schools. The temples of these schools became important places for the study of Buddhist doctrine. The six Nara schools were: ''

Ritsu'' (

Vinaya

The Vinaya (Pali & Sanskrit: विनय) is the division of the Buddhist canon ('' Tripitaka'') containing the rules and procedures that govern the Buddhist Sangha (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). Three parallel Vinaya traditions remai ...

), ''Jōjitsu'' (

Tattvasiddhi)'',

Kusha-shū

The was one of the six schools of Buddhism introduced to Japan during the Asuka and Nara periods. Along with the and the Risshū, it is a school of Nikaya Buddhism, which is sometimes derisively known to Mahayana Buddhism as "the Hinayana".

A ...

'' (

Abhidharmakosha), ''Sanronshū'' (

East Asian Mādhyamaka), ''Hossō'' (

East Asian Yogācāra

East Asian Yogācāra (, "'Consciousness Only' school" or , "'Dharma Characteristics' school") refers to the traditions in East Asia which developed out of the Indian Buddhist Yogachara systems.

The 4th-century Gandharan brothers, Asaṅga an ...

) and ''

Kegon'' (

Huayan).

These schools were centered around the capital where great temples such as the

Asuka-dera and

Tōdai-ji were erected. The most influential of the temples are known as the "

seven great temples of the southern capital" (''Nanto Shichi Daiji''). The temples were not exclusive and sectarian organizations. Instead, temples were apt to have scholars versed in several of schools of thought. It has been suggested that they can best be thought of as "study groups".

State temples continued the practice of conducting numerous rituals for the good of the nation and the imperial family. Rituals centered on scriptures like the ''Golden Light'' and the ''

Lotus Sūtra

The ''Lotus Sūtra'' ( zh, 妙法蓮華經; sa, सद्धर्मपुण्डरीकसूत्रम्, translit=Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtram, lit=Sūtra on the White Lotus of the True Dharma, italic=) is one of the most influ ...

''. Another key function of the state temples was the transcription of Buddhist scriptures, which was seen as generating much merit. Buddhist monastics were firmly controlled by the state's monastic office through an extensive monastic code of law, and monastic ranks were matched to the ranks of government officials. It was also during this era that the ''Nihon Shoki'' was written, a text which shows significant Buddhist influence. The monk Dōji (?–744) may have been involved in its compilation.

[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 60-61]

The elite state sponsored Nara Buddhism was not the only type of Buddhism at this time. There were also groups of unofficial monastics or priests (or, self-ordained; ''shido sōni'') who were either not formally ordained and trained through the state channels, or who chose to preach and practice outside of the system. These "unofficial" monks were often subject to state punishment.

Their practice could have also included Daoist and indigenous kami worship elements. Some of these figures became immensely popular and were a source of criticism for the sophisticated, academic and bureaucratic Buddhism of the capital.

Early Heian Period Buddhism (794–950)

During the

Heian period, the capital was shifted to

Kyoto (then known as

Heiankyō) by

emperor Kanmu, mainly for economic and strategic reasons. As before, Buddhist institutions continued to play a key role in the state, with Kanmu being a strong supporter of the new Tendai school of

Saichō (767–822) in particular. Saichō, who had studied the Tiantai school in China, established the influential temple complex of

Enryakuji at

Mount Hiei, and developed a new system of monastic regulations based on the

bodhisattva precepts

The Bodhisattva Precepts ( Skt. ''bodhisattva-śīla'', , ja, bosatsukai) are a set of ethical trainings (''śīla'') used in Mahāyāna Buddhism to advance a practitioner along the path to becoming a bodhisattva. Traditionally, monastics obse ...

. This new system allowed Tendai to free itself from direct state control.

Also during this period, the

Shingon ( Ch. Zhenyan; "True Word", from Sanskrit: "

Mantra") school was established in the country under the leadership of

Kūkai. This school also received state sponsorship and introduced esoteric

Vajrayana (also referred to as ''

mikkyō'', "secret teaching") elements.

The new Buddhist lineages of Shingon and Tendai also developed somewhat independently from state control, partly because the old system was becoming less important to Heian aristocrats. This period also saw an increase in the official separation between the different schools, due to a new system that specified the particular school which an imperial priest (''nenbundosha'') belonged to.

Later Heian Period Buddhism (950–1185)

During this period, there was a consolidation of a series of annual court ceremonies (''nenjū gyōji''). Tendai Buddhism was particularly influential, and the veneration of the ''Lotus Sūtra'' grew in popularity, even among the low class and non-aristocratic population, which often formed religious groups such as the "Lotus holy ones" (''hokke hijiri'' or ''jikyōja'') and

mountain ascetics (''shugenja'').

Furthermore, during this era, new Buddhist traditions began to develop. While some of these have been grouped into what is referred to as "new Kamakura" Buddhism, their beginning can actually be traced to the late Heian. This includes the practice of Japanese

Pure Land Buddhism, which focuses on the contemplation and chanting of the ''

nenbutsu'', the name of the Buddha

Amida (Skt. Amitābha), in hopes of being reborn in the

Buddha field

A pure land is the celestial realm of a buddha or bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism. The term "pure land" is particular to East Asian Buddhism () and related traditions; in Sanskrit the equivalent concept is called a buddha-field (Sanskrit ). The ...

of

Sukhāvatī

Sukhavati (International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration, IAST: ''Sukhāvatī''; "Blissful") is a pure land of Amitābha in Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhism. It is also called the Land of Bliss or Western Pure Land, and is the most well-known o ...

. This practice was initially popular in Tendai monasteries but then spread throughout Japan. Texts which discussed miracles associated with the Buddhas and bodhisattvas became popular in this period, along with texts which outlined death bed rites.

During this period, some Buddhist temples established groups of warrior-monks called

Sōhei. This phenomenon began in Tendai temples, as they vied for political influence with each other. The

Genpei war

The was a national civil war between the Taira and Minamoto clans during the late Heian period of Japan. It resulted in the downfall of the Taira and the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate under Minamoto no Yoritomo, who appointed himself ...

saw various groups of warrior monks join the fray.

There were also semi-independent clerics (who were called shōnin or hijiri, "holy ones") who lived away from the major Buddhist monasteries and preached to the people. These figures had much more contact with the general populace than other monks. The most well known of these figures was

Kūya (alt. Kōya; 903–972), who wandered throughout the provinces engaging in good works (''sazen''), preaching on nembutsu practice and working with local Buddhist cooperatives (''zenchishiki'') to create images of bodhisattvas like Kannon.

Another important development during this era was that Buddhist monks were now being widely encouraged by the state to pray for the salvation of Japanese ''

kami'' (divine beings in Shinto). The merging of Shinto deities with Buddhist practice was not new at this time. Already in the eighth century, some major Shinto shrines (

''jingūji'') included Buddhist monks which conducted rites for shinto divinities. One of the earliest such figures was "great Bodhisattva

Hachiman

In Japanese religion, ''Yahata'' (八幡神, ancient Shinto pronunciation) formerly in Shinto and later commonly known as Hachiman (八幡神, Japanese Buddhist pronunciation) is the syncretic divinity of archery and war, incorporating elements f ...

" (Hachiman daibosatsu) who was popular in

Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's five main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands ( i.e. excluding Okinawa). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regional name referred to Kyushu and its surround ...

.

Popular sites for pilgrimage and religious practice, like

Kumano, included both kami worship and the worship of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, which were often associated with each other. Furthermore, temples like Tōdaiji also included shrines for the worship of kami (in Tōdaiji's case, it was the kami Shukongōjin that was enshrined in its rear entryway).

Buddhist monks interpreted their relationship to the kami in different ways. Some monks saw them as just worldly beings who could be prayed for. Other saw them as manifestations of Buddhas and bodhisattvas. For example, the Mt. Hiei monk Eryō saw the kami as "traces" (suijaku) of the Buddha. This idea, called

essence-trace (''honji-suijaku''), would have a strong influence throughout the medieval era.

The copying and writing of Buddhist scripture was a widespread practice in this period. It was seen as producing

merit (good karma). Artistic portraits depicting events from the scriptures were also quite popular during this era. They were used to generate merit as well as to preach and teach the doctrine. The "Enshrined Sutra of the

Taira Family" (''Heikenōkyō''), is one of the greatest examples of Buddhist visual art from this period. It is an elaborately illustrated Lotus Sūtra installed at

Itsukushima Shrine

is a Shinto jinja (shrine), shrine on the island of Itsukushima (popularly known as Miyajima, Hiroshima, Miyajima), best known for its "floating" ''torii'' gate.Louis-Frédéric, Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric (2005)"''Itsukushima-jinja''"in ''Japa ...

.

The Buddhist liturgy of this era also became more elaborate and performative. Rites such as the Repentance Assembly (''keka'e'') at

Hōjōji developed to include elaborate music, dance and other forms of performance. Major temples and monasteries such as the royal

Hosshōji temple and Kōfukuji, also became home to the performance of

Sarugaku theater (which is the origin of

Nō Drama) as well as ennen ("longevity-enhancing") arts which included dances and music. Doctrinally, these performative arts were seen as

skillful means (''hōben'', Skt. ''upaya'') of teaching Buddhism. Monks specializing in such arts were called yūsō ("artistic monks").

Another way of communicating the Buddhist message was through the medium of poetry, which included both Chinese poetry (

kanshi) and Japanese poetry (

waka). An example of Buddhist themed waka is Princess Senshi's (964–1035) ''Hosshin waka shū'' (Collection of Waka of the Awakening Mind, 1012). The courtly practice of rōei (performing poetry to music) was also taken up in the Tendai and Shingon lineages. Both monks and laypersons met in poetry circles (''kadan'') like the

Ninnaji circle which was patronized by Prince Shukaku (1150–1202).

Early and Middle Kamakura Buddhism (1185–1300)

The

Kamakura period

The is a period of Japanese history that marks the governance by the Kamakura shogunate, officially established in 1192 in Kamakura by the first ''shōgun'' Minamoto no Yoritomo after the conclusion of the Genpei War, which saw the struggle betwee ...

was a period of crisis in which the control of the country moved from the imperial aristocracy to the

samurai. In 1185 the

Kamakura shogunate was established at

Kamakura

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

Kamakura has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 persons per km² over the total area of . Kamakura was designated as a city on 3 November 1939.

Kamak ...

.

This period saw the development of new Buddhist lineages or schools which have been called "Kamakura Buddhism" and "New Buddhism". All of the major founders of these new lineages were ex-Tendai monks who had trained at Mt. Hiei and had studied the exoteric and esoteric systems of Tendai Buddhism. During the Kamakura period, these new schools did not gain as much prominence as the older lineages, with the possible exception of the highly influential

Rinzai Zen school.

The new schools include Pure Land lineages like

Hōnen's (1133–1212)

Jōdo shū and

Shinran's (1173–1263)

Jōdo Shinshū

, also known as Shin Buddhism or True Pure Land Buddhism, is a school of Pure Land Buddhism. It was founded by the former Tendai Japanese monk Shinran.

Shin Buddhism is the most widely practiced branch of Buddhism in Japan.

History

Shinran ( ...

, both of which focused on the practice of chanting the name of Amida Buddha. These new Pure Land schools both believed that Japan had entered the era of the decline of the Dharma (

''mappō'') and that therefore other Buddhist practices were not useful. The only means to liberation was now the faithful chanting of the nembutsu. This view was critiqued by more traditional figures such as

Myō'e (1173–1232).

Another response to the social instability of the period was an attempt by certain monks to return to the proper practice of Buddhist precepts as well as meditation. These figures include figures like the Kōfukuji monk

Jōkei (1155–1213) and the Tendai monk Shunjō (1166–1227), who sought to return to the traditional foundations of the Buddhist path, ethical cultivation and meditation practice.

Other monks attempted to minister to marginalized low class groups. The Kegon-Shingon monk Myō'e was known for opening his temple to lepers, beggars, and other marginal people, while precept masters such as

Eison (1201–1290) and

Ninshō (1217–1303) were also active in ministering and caring for ill and marginalized persons, particularly those outcast groups termed "non-persons" (''

hinin''). Deal & Ruppert (2015) p. 122 Ninshō established a medical facility at

Gokurakuji in 1287, which treated more than 88,000 people over a 34-year-period and collected Chinese medical knowledge.

Another set of new Kamakura schools include the two major

Zen schools of Japan (Rinzai and

Sōtō), promulgated by monks such as

Eisai and

Dōgen, which emphasize liberation through the insight of meditation (zazen). Dōgen (1200–1253) began a prominent meditation teacher and abbot. He introduced the

Chan

Chan may refer to:

Places

*Chan (commune), Cambodia

*Chan Lake, by Chan Lake Territorial Park in Northwest Territories, Canada

People

*Chan (surname), romanization of various Chinese surnames (including 陳, 曾, 詹, 戰, and 田)

*Chan Caldwel ...

lineage of

Caodong, which would grow into the Sōtō school. He criticized ideas like the

final age of the Dharma (''mappō''), and the practice of

apotropaic prayer.

Additionally, it was during this period that monk

Nichiren (1222–1282) began teaching his exclusively ''

Lotus Sutra'' based Buddhism, which he saw as the only valid object of devotion in the age of mappō. Nichiren believed that the conflicts and disasters of this period were caused by the wrong views of Japanese Buddhists (such as the followers of Pure Land and esoteric Buddhism). Nichiren faced much opposition for his views and was also attacked and exiled twice by the Kamakura state.

Late Medieval Buddhism (1300-1467)

During this period, the new "Kamakura schools" continued to develop and began to consolidate themselves as unique and separate traditions. However, as Deal and Ruppert note, "most of them remained at the periphery of Buddhist institutional power and, in some ways, discourse during this era." They further add that it was only "from the late fifteenth century onward that these lineages came to increasingly occupy the center of Japanese Buddhist belief and practice." The only exception is

Rinzai Zen, which attained prominence earlier (13th century).

[Deal & Rupert (2015) pp. 135-136] Meanwhile, the "old" schools and lineages continued to develop in their own ways and remained influential.

The new schools' independence from the old schools did not happen all at once. In fact, the new schools remained under the old schools' doctrinal and political influence for some time. For example, Ōhashi Toshio has stressed how during this period, the Jōdo sect was mainly seen as a subsidiary or temporary branch sect of Tendai. Furthermore, not all monks of the old sects were antagonistic to the new sects.

During the height of the medieval era, political power was decentralized and shrine-temple complexes were often competing with each other for influence and power. These complexes often controlled land and multiple manors, and also maintained military forces of warrior monks which they used to battle with each other. In spite of the instability of this era, the culture of Buddhist study and learning continued to thrive and grow.

[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 142-144]

Furthermore, though there were numerous independent Buddhist schools and lineages at this time, many monks did not exclusively belong to one lineage and instead traveled to study and learn in various temples and seminaries. This tendency of practicing in multiple schools or lineages was termed ''shoshū kengaku''. It became much more prominent in the medieval era due to the increased social mobility that many monks enjoyed''.''

Both the

Kamakura shogunate (1192–1333) and the

Ashikaga shogunate (1336–1573) supported and patronized the "

Five Mountains culture" (''Gozan Jissetsu Seido'') of

Rinzai Zen. This Rinzai Zen tradition was centered on the ten "Five Mountain" temples (five in Kyoto and five in Kamakura). Besides teaching zazen meditation, they also pursued studies in esoteric Buddhism and in certain art forms like calligraphy and poetry. A pivotal early figure of Rinzai was

Enni Ben'en

Enni Ben'en (圓爾辯圓, pinyin: ''Yuán'ěr Biànyuán''; 1 November 1202 – 10 November 1280), also known as Shōichi Kokushi, was a Japanese Buddhist monk. He started his Buddhist training as a Tendai monk. While he was studying with ...

(1202–1280), a high-ranking and influential monk who was initiated into Tendai and Shingon. He then traveled to China to study Zen and later founded

Tōfukuji.

The Tendai and Shingon credentials of Rinzai figures such as Enni show that early Zen was not a lineage that was totally separate from the other "old" schools. Indeed, Zen monastic codes feature procedures for "worship of the Buddha, funerals, memorial rites for ancestral spirits, the feeding of hungry ghosts, feasts sponsored by donors, and tea services that served to highlight the bureaucratic and social hierarchy."

Medieval Rinzai was also invigorated by a series of Chinese masters who came to Japan during the Song dynasty, such as

Issan Ichinei

Yishan Yining (一山一寧, in Japanese: ''Issan Ichinei'') (1247 – 28 November 1317) was a Chinese Buddhist monk who traveled to Japan. Before monkhood his family name was Hu. He was born in 1247 in Linhai, Taizhou, Zhejiang, China. He was ...

(1247–1317). Issan influenced the Japanese interest in Chinese literature, calligraphy and painting. The

Japanese literature

Japanese literature throughout most of its history has been influenced by cultural contact with neighboring Asian literatures, most notably China and its literature. Early texts were often written in pure Classical Chinese or , a Chinese-Japanes ...

of the Five Mountains (

''Gozan Bungaku'') reflects this influence. One of his students was

Musō Soseki, a Zen master, calligraphist, poet and garden designer who was granted the title "national Zen teacher" by Emperor

Go-Daigo. The Zen monk poets

Sesson Yūbai and

Kokan Shiren also studied under Issan.

[Louis-Frédéric, Käthe Roth]

Japan encyclopedia.

Harvard University Press, 2005. , Стр. 402 Shiren was also a historian who wrote the Buddhist history ''

Genkō shakusho''.

The Royal court and elite families of the capital also studied the classic Chinese arts that were being taught in the five mountain Rinzai temples. The shogunal families even built Zen temples in their residential palaces. The five mountain temples also established their own printing program (''Gozan-ban'') to copy and disseminate a wide variety of literature that included records of Zen masters, the writings of

Tang poets,

Confucian classics, Chinese dictionaries, reference works, and medical texts.

It is also during this period that true lineages of "Shintō" kami worship begin to develop in Buddhist temples complexes, lineages which would become the basis for institutionalized Shintō of later periods. Buddhists continued to develop theories about the relationship between kami and the Buddhas and bodhisattvas. One such idea, ''

gongen'' ("provisional manifestation")'','' promoted the worship of kami as manifest forms of the Buddhas. A group of Tendai monks at Mt. Hiei meanwhile incorporated ''

hongaku'' thought into their worship of the kami Sannō, which eventually came to be seen as the source or "original ground" (''honji'') of all Buddhas (thereby reversing the old ''

honji suijaku'' theory which saw the Buddha as the ''honji''). This idea can be found in the work of the Hiei monk Sonshun (1451–1514).

Late Muromachi-Period Buddhism (1467–1600)

Beginning with the devastating

Ōnin War (1467–1477), the

Muromachi period (1336–1573) saw the devolution of central government control and the rise of regional

samurai warlords called ''

daimyōs'' and the so called "warring states era" (''

Sengokuki''). During this era of widespread warfare, many Buddhist temples and monasteries were destroyed, particularly in and around Kyoto. Many of these old temples would not be rebuilt until the 16th and 17th centuries.

During this period, the new Kamakura schools rose to a new level of prominence and influence. They also underwent reforms in study and practice which would make them more independent and would last centuries. For example, it was during this period that the True Pure Land monk

Rennyo (1415–1499) forged a large following for his school and rebuilt

Honganji. He reformed devotional practices with a focus on Shinran and

honzon scrolls inscribed with the nembutsu. He also made widespread use of the Japanese vernacular.

The Zen lineages were also widely disseminated throughout the country during this era. A key contributing factor to their spread (as well as to the spread of Pure Land temples) was their activity in funerals and mortuary rituals. Some temple halls were reconstructed with a focus on mortuary rites (sometimes for a specific family, like the

Tokugawa) and were thus known as mortuary temples (''

bodaiji''). Furthermore, during this era, schools like Soto Zen, the Hokke (Nichiren) schools and Rennyo's Pure land school also developed comprehensive curricula for doctrinal study, which allowed them to become more self sufficient and independent schools and eliminated the need for their monks to study with other schools.

There was also a decrease in the ritual schedule of the royal court. Because of this, Buddhist Temples which did survive this period had to turn to new ways of fundraising. Aside from mortuary duties, this also included increasing public viewings (''kaichos'') of hidden or esoteric images.

This era also saw the rise of militant Buddhist leagues (''ikki''), like the

Ikko Ikki ("Single Minded" Pure Land Leagues) and Hokke Ikki (Nichirenist "Lotus" Leagues), who rose in revolt against samurai lords and established self-rule in certain regions. These leagues would also sometimes go to war with each other and with major temples. The Hokke Ikki managed to destroy the Ikko Ikki's

Yamashina Honganji temple complex and take over much of Kyoto in the 1530s. They eventually came into conflict with the Tendai warrior monks of Enryakuji in what became known as the Tenbun Period War, in which all 21 major Hokke (Nichiren) temples were destroyed, along with much of Kyoto.

[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 179-181]

The Tendai warrior monks and the Ikko Ikki leagues remained a major political power in Japan until their defeat at the hands of

Oda Nobunaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period. He is regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan.

Nobunaga was head of the very powerful Oda clan, and launched a war against other ''daimyō'' to unify ...

(1534–1582), who subjugated both the Tendai monks at Mt Hiei and then the Ikko Ikki, in the

Ishiyama Honganji War (1570–1580) .

During the mid-sixteenth century westerners first began to arrive in Japan, introducing new technologies, as well as Christianity. This led to numerous debates between Christians and Buddhists, such as the so-called "Yamaguchi sectarian debates" (''yamaguchi no shūron'').

Early and Middle Edo-Period Buddhism (1600–1800)

After the

Sengoku period of war, Japan was re-united by the

Tokugawa Shogunate (1600–1868) who ran the country through a feudal system of regional ''daimyō''. The Tokugawa also banned most foreigners from entering the country. The only traders to be allowed were the Dutch at the island of

Dejima.

During the seventeenth century, the

Tokugawa shōgun Iemitsu set into motion a series of reforms which sought to increase state control of religion (as well as to eliminate Christianity). Iemitsu's reforms developed what has been called the head–branch system (''hon-matsu seido'') and the temple affiliation system (''jidan''; alt. ''danka seido''). This system made use of already existing Buddhist institutions and affiliations, but attempted to bring them under official government control and required all temples to be affiliated with a government recognized lineage. In general, the

Tendai,

Pure Land

A pure land is the celestial realm of a buddha or bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism. The term "pure land" is particular to East Asian Buddhism () and related traditions; in Sanskrit the equivalent concept is called a buddha-field (Sanskrit ). Th ...

, and

Shingon sects were treated more favourably than the

True Pure Land and

Nichiren sects because the latter had a history of inciting socio-political disturbances in the 16th century.

Buddhist leaders often worked with the government, providing religious support for their rule. For example, the Zen monk

Takuan Sōhō (1573–1645) suggested that the spirit of

Tokugawa Ieyasu, was a kami (divine spirit). He also wrote a book on zen and martial arts (''

The Unfettered Mind'') addressed to the samurai. Meanwhile,

Suzuki Shōsan

was a Japanese samurai who served under the ''shōgun'' Tokugawa Ieyasu. Shōsan was born in modern-day Aichi Prefecture of Japan. He participated in the Battle of Sekigahara and the Battle of Osaka before renouncing life as a warrior and becomi ...

would even call the Tokugawa shōgun a "holy king" (''shōō'').

[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 188-190]

In the Edo Period, Buddhist institutions procured funding through various ritual means, such as the sale of talismans, posthumous names and titles, prayer petitions, and medicine.

[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 199-201] The practice of pilgrimage was also prominent in the Edo Period. Many temples and holy sites like

Mt. Kōya,

Mt. Konpira and Mt. Ōyama (

Sagami Province) hosted Buddhist pilgrims and mountain ascetics throughout the era.

[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 193-195]

During the 17th century, the

Ōbaku lineage of Zen would be introduced by

Ingen

Ingen Ryūki () (December 7, 1592 – May 19, 1673) was a Chinese poet, calligrapher, and monk of Linji Chan Buddhism from China.Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Ingen" in ; n.b., Louis-Frédéric is pseudonym of Louis-Frédéric Nussbaum, ' ...

, a Chinese monk. Ingen had been a member of the

Linji school in Ming China. This lineage, which promoted the dual practice of zazen and nembutsu, would be very successful, having over a thousand temples by the mid-18th century.

Meanwhile, a new breed of public preaches was beginning to frequent public spaces and develop new forms of preaching. These include Pure Land monk

Sakuden (1554–1642), who is seen as an originator of

Rakugo humor and wrote the ''Seisuishō'' (Laughs to Wake You Up), which is a collection of humorous anecdotes. Other traveling preachers of the era who made use of stories and narratives include the Shingon-Ritsu monk Rentai (1663–1726) and the Pure Land monk

Asai Ryōi (d. 1691).

During the 18th century, Japanese Rinzai would be transformed by the work of

Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768) and his students. Hakuin focused on reforming Rinzai kōan training, which he interpreted as a somatic practice by drawing on ideas from Chinese medicine and Daoism. Hakuin also criticized the mixing of Zen and Pure Land.

During the Edo period, there was an unprecedented growth of print publishing (in part due to the support of the Tokugawa regime), and the creation and sale of printed Buddhist works exploded. The Tendai monk

Tenkai, supported by Iemitsu, led the printing of the Buddhist "canon" (''issaikyō,'' i.e. ''

The Tripiṭaka''). Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 184–186 Also notable was the publication of an exceptionally high quality reprint of the Ming-era ''Tripiṭaka'' by

Tetsugen Doko, a renowned master of the Ōbaku school.

[Japan Buddhist Federation, Buddhane]

"A Brief History of Buddhism in Japan", accessed 30/4/2012

/ref> An important part of the publishing boom were books of Buddhist sermons called ''kange-bon'' or ''dangi-bon.''[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 200-202]

Also during this time there was a widespread movement among many Buddhist sects to return to the proper use of Buddhist precepts. Numerous figures in the Ōbaku, Shingon, Shingon-risshū, Nichiren, Jōdo shū and Soto schools participated in this effort to tighten and reform Buddhist ethical discipline.

Meiji period (1868-1931)

After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the new imperial government adopted a strong anti-Buddhist attitude. A new form of pristine Shinto, shorn of all Buddhist influences, was promoted as the state religion, an official state policy known as ''

After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the new imperial government adopted a strong anti-Buddhist attitude. A new form of pristine Shinto, shorn of all Buddhist influences, was promoted as the state religion, an official state policy known as ''shinbutsu bunri

The Japanese term indicates the separation of Shinto from Buddhism, introduced after the Meiji Restoration which separated Shinto ''kami'' from buddhas, and also Buddhist temples from Shinto shrines, which were originally amalgamated. It is a ...

'' (separating Buddhism from Shinto), which began with the ''Kami and Buddhas Separation Order'' (''shinbutsu hanzenrei'') of 1868. The ideologues of this new Shinto sought to return to a pure Japanese spirit, before it was "corrupted" by external influences, mainly Buddhism. They were influenced by national study ('' kokugaku'') figures like Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801) and Hirata Atsutane (1776–1843), both of whom strongly criticized Buddhism. The new order dismantled the combined temple-shrine complexes that had existed for centuries. Buddhists priests were no longer able to practice at Shinto shrines and Buddhist artifacts were removed from Shinto shrines.[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 212-214]

This sparked a popular and often violent movement to eradicate Buddhism, which was seen as backwards and foreign and associated with the corrupt Shogunate. There had been much pent-up anger among the populace because the Tokugawa ''danka'' system forced families to affiliate themselves with a Buddhist temple, which included the obligation of monetary donations. Many Buddhist temples abused this system to make money, causing an undue burden on their parishioners.[Paul B. Watt, Review of ''Nam-Lin Hur, Death and Social Order in Tokugawa Japan: Buddhism, Anti-Christianity, and the Danka System''](_blank)

Internet Archive[Nam-Lin Hur, ''Death and social order in Tokugawa Japan: Buddhism, anti-Christianity, and the danka system,'' Harvard University Asia Center, 2007; pp. 1-30 (The Rise of Funerary Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan)]

Internet archive

/ref>

This religious persecution of Buddhism, known as '' haibutsu kishaku (''literally: ''"abolish Buddhism and destroy Shākyamuni"''), saw the destruction and closure of many Buddhist institutions throughout Japan as well as the confiscation of their land, the forced laicization of Buddhist monks and the destruction of Buddhist books and artifacts. In some instances, monks were attacked and killed.[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 213-215.]

Anti-Buddhist government policies and religious persecution put many Buddhist institutions on the defensive against those who saw it as the enemy of the Japanese people.[Deal & Ruppert (2015) p. 209.] This led Japanese Buddhist institutions to re-examine and re-invent the role of Buddhism in a modernizing Japanese state which now supported state Shintō.[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 214-216] The New Buddhists often joined Japanese nationalist patriotism with Buddhist virtues. Some new Buddhist organizations fully embraced Japanese nationalism, such as the '' Kokuchūkai'' (Pillar of the Nation Society) of Tanaka Chigaku

was a Japanese Buddhist scholar and preacher of Nichiren Buddhism, orator, writer and ultranationalist propagandist in the Meiji, Taishō and early Shōwa periods. He is considered to be the father of Nichirenism, the fiercely ultranatio ...

(1861–1939), who promoted Japanese Imperialism as a way to spread the message of the Lotus Sutra. Another new Buddhist society was the ''Keii-kai'' (Woof and Warp Society, founded in 1894), which was critical of doctrinal rigidity of traditional Buddhism and championed what they termed "free investigation" (jiyū tōkyū) as a way to respond to the rapid changes of the time.

Kiyozawa Manshi's ''Seishin-shugi'' (Spiritualism) movement promoted the idea that Buddhists should focus on self-cultivation without relying on organized Buddhism or the state. Kiyozawa and his friends lived together in a commune called Kōkōdō (Vast Cavern), and published a journal called ''Seishinkai'' (Spiritual World).[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 220-222]

There were also a number of new Buddhist movements that grew popular in the Meiji period through 1945. Some of the most influential of these were the Nichirenist/Lotus movements of Sōka Gakkai, Reiyūkai

, or Reiyūkai Shakaden, is a Japanese Buddhism, Buddhist Japanese new religions, new religious movement founded in 1919 by Kakutarō Kubo (1892-1944) and Kimi Kotani (1901-1971). It is a laity, lay organization (there are no priests) inspired by ...

, and Risshō Kōseikai. They focused on active proselytization and worldly personal benefits.

War time Buddhism (1931–1945)

During the "fifteen year war" (beginning with the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and ending with the surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy ...

in '45), most Japanese Buddhist institutions supported Japan's militarization.

Japanese Buddhist support for imperialism and militarism was rooted in the Meiji era need for Buddhists to show that they were good citizens that were relevant to Japan's efforts to modernize and become a major power. Some Buddhists, like Tanaka Chigaku, saw the war as a way to spread Buddhism. During the Russo-Japanese War, Buddhist leaders supported the war effort in different ways, such as by providing chaplains to the army, performing rituals to secure victory and working with the families of fallen soldiers. During the fifteen-year war, Japanese Buddhists supported the war effort in similar ways, and Buddhist priests became attached to Imperial army regiments.[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 222-225]

The Myōwakai (Society for Light and Peace), a transsectarian Buddhist organization, was a strong supporter of the war effort who promoted the idea of "benevolent forcefulness" which held that "war conducted for a good reason is in accord with the great benevolence and compassion of Buddhism."[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 224-226]

Buddhists were also forced to venerate talismans from the Isse Shrine, and there were serious consequences for those who refused. For example, during the 1940s, "leaders of both Honmon Hokkeshu and Sōka Gakkai were imprisoned for their defiance of wartime government religious policy, which mandated display of reverence for state Shinto."[Religion and American Cultures, An Encyclopedia, vol 1 p. 61 ] A few individuals who directly opposed war were targeted by the government. These include the Rinzai priest Ichikawa Hakugen, and Itō Shōshin (1876–1963), a former Jōdo Shinshū priest.

Japanese Buddhism since 1945

At the end of the war, Japan was devastated by the allied bombing campaigns, with most cities in ruins. The occupation government abolished state Shinto, establishing freedom of religion and a separation of religion and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

which became an official part of the Japanese constitution.

This meant that Buddhist temples and institutions were now free to associate with any religious lineage or to become independent if doctrinal or administrative differences proved too much. One example is when Hōryūji temple became independent from the Hossō lineage and created its own Shōtoku denomination.[Deal & Ruppert (2015) pp. 232-234]

The Japanese populace was aware of Buddhist involvement in aiding and promoting the war effort. Because of this, Buddhist lineages have engaged in acts of repentance for their wartime activities. Buddhist groups have been active in the post-war peace movement. During the post-war period, in contrast to traditional temple Buddhism, Buddhist based Japanese new religions grew rapidly, especially the Nichiren/Lotus Sūtra based movements like Sōka Gakkai and Risshō Kōseikai (which are today the largest lay Buddhist organizations in Japan). Soka Gakkai "... grew rapidly in the chaos of post war Japan

During the post-war period, in contrast to traditional temple Buddhism, Buddhist based Japanese new religions grew rapidly, especially the Nichiren/Lotus Sūtra based movements like Sōka Gakkai and Risshō Kōseikai (which are today the largest lay Buddhist organizations in Japan). Soka Gakkai "... grew rapidly in the chaos of post war JapanAum Shinrikyō

, formerly , is a Japanese doomsday cult founded by Shoko Asahara in 1987. It carried out the deadly Tokyo subway sarin attack in 1995 and was found to have been responsible for the Matsumoto sarin attack the previous year.

The group says th ...

, the most notorious of these new new religions, is a dangerous cult responsible for the Tokyo gas attack.

The post-war era also saw a new philosophical movements among Buddhist intellectuals called the Kyoto school, since it was led by a group of Kyoto University professors, mainly Nishida Kitarō

was a Japanese moral

philosopher, philosopher of mathematics and science, and religious scholar. He was the founder of what has been called the Kyoto School of philosophy. He graduated from the University of Tokyo during the Meiji period in 18 ...

(1870–1945), Tanabe Hajime (1885–1962), and Nishitani Keiji

was a Japanese university professor, scholar, and Kyoto School philosopher. He was a disciple of Kitarō Nishida. In 1924 Nishitani received his doctorate from Kyoto Imperial University for his dissertation ''"Das Ideale und das Reale bei Sche ...

(1900–1991). These thinkers drew from Western philosophers like Kant, Hegel and Nietzsche and Buddhist thought to express a new perspective. Another intellectual field that has attracted interest is Critical Buddhism

Critical Buddhism (Japanese: 批判仏教, hihan bukkyō) was a trend in Japanese Buddhist scholarship, associated primarily with the works of Hakamaya Noriaki (袴谷憲昭) and Matsumoto Shirō (松本史朗).

Hakamaya stated that "'Buddhism ...

(''hihan bukkyō''), associated with Sōtō Zen priests like Hakamaya Noriaki (b. 1943) and Matsumoto Shirō (b. 1950), who criticized certain key ideas in Japanese Mahayana (mainly Buddha nature and original enlightenment) as being incompatible with the Buddha's not-self doctrine. Critical Buddhists have also examined the moral failings of Japanese Buddhism, such as support for nationalist violence and social discrimination.

Japanese Buddhist schools

Japanese Buddhism is very diverse with numerous independent schools and temple lineages (including the "old" Nara schools and the "new" Kamakura schools) that can be traced back to ancient and medieval Japan, as well as more recent Japanese New Religious movements and modern lay organizations.

According to the religious statistics of 2021 by the Agency for Cultural Affairs

The is a special body of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). It was set up in 1968 to promote Japanese arts and culture.

The agency's budget for FY 2018 rose to ¥107.7 billion.

Overview

The ag ...

of Japan, the religious corporation under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology

The , also known as MEXT or Monka-shō, is one of the eleven Ministries of Japan that composes part of the executive branch of the Government of Japan. Its goal is to improve the development of Japan in relation with the international community ...

in Japan had 135 million believers, of which 47 million were Buddhists and most of them were believers of new schools of Buddhism which were established in the Kamakura period

The is a period of Japanese history that marks the governance by the Kamakura shogunate, officially established in 1192 in Kamakura by the first ''shōgun'' Minamoto no Yoritomo after the conclusion of the Genpei War, which saw the struggle betwee ...

(1185-1333). The number of believers of each sect is approximately 22 million for the Jōdo Buddhism ( Jōdo-shū, Jōdo Shinshū

, also known as Shin Buddhism or True Pure Land Buddhism, is a school of Pure Land Buddhism. It was founded by the former Tendai Japanese monk Shinran.

Shin Buddhism is the most widely practiced branch of Buddhism in Japan.

History

Shinran ( ...

, Yuzu Nembutsu and Ji-shū), 11 million for the Nichiren Buddhism, 5.5 million for the Shingon Buddhism, 5.3 million for the Zen Buddhism ( Rinzai, Sōtō and Ōbaku), 2.8 million for the Tendai Buddhism, and only about 700,000 for the old schools, which were established in the Nara period (710-794).[文化庁 宗教年鑑令和3年版. p.51](_blank)

Agency for Cultural Affairs

The is a special body of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). It was set up in 1968 to promote Japanese arts and culture.

The agency's budget for FY 2018 rose to ¥107.7 billion.

Overview

The ag ...

An old saying regarding the schools of Buddhism in relation to the different classes is:

Some of the major groups are outlined below.

The Old Schools

Six Nara Schools

The Six Nara Schools are the oldest Buddhist schools in Japan. They are associated with the ancient capital of Nara, where they founded the famed " seven great temples of the southern capital" (''Nanto Shichi Daiji'' 南都七大寺).

The six schools are:

* Hossō - is based on the Idealistic "consciousness-only" philosophy of Asanga

Asaṅga (, ; Romaji: ''Mujaku'') ( fl. 4th century C.E.) was "one of the most important spiritual figures" of Mahayana Buddhism and the "founder of the Yogachara school".Engle, Artemus (translator), Asanga, ''The Bodhisattva Path to Unsurpassed ...

and Vasubandhu. The East Asian Yogācāra school of Buddhism was founded by Xuanzang (玄奘, Jp. ''Genjō'') in China c. 630 and introduced to Japan in 654 by Dōshō, who had travelled to China to study under him.[Heinrich Dumoulin, James W. Heisig, Paul F. Knitter, ''Zen Buddhism : a History: Japan'', p. 5. World Wisdom, Inc, 2005] The is an important text for the Hossō school. Hossō was connected with several prominent temples: Hōryūji, Yakushiji, and Kōfukuji.

*Kusha - This is a school of Nikaya Buddhism which focused on the , a compendium of Abhidharma by the fourth-century Buddhist philosopher Vasubandhu. Kusha was never a truly independent school, instead it was studied along with Hossō doctrine.

* Sanron - The Chinese ''Three-Discourse School'' was transmitted to Japan in the 7th century. It is a Madhyamaka school which developed in China based on two discourses by Nagarjuna and one by Aryadeva. Madhyamaka is one of the most important Mahayana philosophical schools, and emphasizes the emptiness of all phenomena. Sanron was the focus of study at Gangōji and Daianji.

*Jōjitsu - A tradition focused on the study of the '' Tattvasiddhi shastra'', a text possibly belonging to the Sautrantika school. It was introduced in 625 by the monk Ekwan of Goryeo. Jōjitsu was never an independent school, instead it was taught in tandem with Sanron.

* Kegon - The Kegon (Ch. Huayan, Skt. Avatamsaka) school was founded by c. 600 and was introduced to Japan by the Indian monk Bodhisena in 736. The ''Avatamsaka Sutra

The ' (IAST, sa, 𑀅𑀯𑀢𑀁𑀲𑀓 𑀲𑀽𑀢𑁆𑀭) or ''Buddhāvataṃsaka-nāma-mahāvaipulya-sūtra (The Mahāvaipulya Sūtra named “Buddhāvataṃsaka”)'' is one of the most influential Mahāyāna sutras of East Asian B ...

'' (''Kegon-kyō'' 華厳経) is the central text (along with the writings of the Chinese Huayan patriarchs).

* Risshū

The traditional Chinese calendar divides a year into 24 solar terms. ''Lìqiū'', ''Risshū'', ''Ipchu'', or ''Lập thu'' () is the 13th solar term. It begins when the Sun reaches the celestial longitude of 135° and ends when it reaches t ...

- The Risshū (Ritsu or vinaya

The Vinaya (Pali & Sanskrit: विनय) is the division of the Buddhist canon ('' Tripitaka'') containing the rules and procedures that govern the Buddhist Sangha (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). Three parallel Vinaya traditions remai ...

school) was founded by Daoxuan (道宣, Jp. ''Dosen''), and introduced to Japan by Jianzhen in 753. The Ritsu school specialized in the Vinaya (the Buddhist monastic rules). They used the Dharmagupta version of the vinaya which is known in Japanese as ''Shibunritsu'' (四分律). It was closely associated with Tōshōdaiji.

Esoteric Schools

* Tendai - This is a branch of the Chinese Tiantai school introduced by Saichō, who also introduced tantric elements into the tradition. The primary text of Tiantai is Lotus Sutra, but the is also important.

* was founded by Kūkai in 816, who traveled to China and studied the Chinese Mantrayana tradition. In China, Kūkai studied Sanskrit, and received tantric initiation from Huiguo. Shingon is based mainly on two tantric scriptures, the ''Mahavairocana Tantra'' and the .

* Shugendō, an eclectic tradition which brought together Buddhist and ancient Shinto elements. It was founded by En no Gyōja

( b. 634, in Katsuragi (modern Nara Prefecture); d. c. 700–707) was a Japanese ascetic and mystic, traditionally held to be the founder of Shugendō, the path of ascetic training practiced by the ''gyōja'' or ''yamabushi''.

He was banish ...

(役行者, ''"En the ascetic"'').

The New Schools

During the Kamakura period, many Buddhist schools (classified by scholars as "New Buddhism" or ''Shin Bukkyo''), as opposed to "Old Buddhism" ''(Kyū Bukkyō)'' of the Nara period.

The main New Buddhism schools are:

* The Jōdo-shū (

During the Kamakura period, many Buddhist schools (classified by scholars as "New Buddhism" or ''Shin Bukkyo''), as opposed to "Old Buddhism" ''(Kyū Bukkyō)'' of the Nara period.

The main New Buddhism schools are:

* The Jōdo-shū (Pure Land

A pure land is the celestial realm of a buddha or bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism. The term "pure land" is particular to East Asian Buddhism () and related traditions; in Sanskrit the equivalent concept is called a buddha-field (Sanskrit ). Th ...

school) founded by Hōnen

was the religious reformer and founder of the first independent branch of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism called . He is also considered the Seventh Jōdo Shinshū Patriarch.

Hōnen became a Tendai initiate at an early age, but grew disaffected and ...

(1133–1212), focused on chanting the name of Amida Buddha Amida can mean :

Places and jurisdictions

* Amida (Mesopotamia), now Diyarbakır, an ancient city in Asian Turkey; it is (nominal) seat of :

** The Chaldean Catholic Archeparchy of Amida

** The Latin titular Metropolitan see of Amida of the Roma ...

so as to be reborn in the Pure land.

* The Yūzū-Nembutsu school was founded by Ryōnin (良忍, 1072–1132), this is another Pure Land school.

* The Jōdo Shinshū

, also known as Shin Buddhism or True Pure Land Buddhism, is a school of Pure Land Buddhism. It was founded by the former Tendai Japanese monk Shinran.

Shin Buddhism is the most widely practiced branch of Buddhism in Japan.

History

Shinran ( ...

(True Pure Land) founded by Shinran

''Popular Buddhism in Japan: Shin Buddhist Religion & Culture'' by Esben Andreasen, pp. 13, 14, 15, 17. University of Hawaii Press 1998, was a Japanese Buddhist monk, who was born in Hino (now a part of Fushimi, Kyoto) at the turbulent close of ...

(1173–1263)

* The Rinzai school of Zen founded by Eisai (1141–1215), a Japanese branch of the Chinese Linji school, focuses on zazen sitting meditation, and kōan practice.

* The Sōtō school of Zen founded by Dōgen (1200–1253), a Japanese branch of the Chinese Caodong school, also focuses on zazen.

* The Nichiren school founded by Nichiren (1222–1282) which focuses on the Lotus Sutra and reciting the name of the Lotus Sutra.

* The Ji-shū branch of Pure Land Buddhism founded by Ippen (1239–1289)

*The Fuke-shū sect of Zen was founded by Puhua in 1254.

* Shingon-risshū ("The Shingon-Vinaya school"), founded by Eison (1201-1290)

Other schools of Japanese Buddhism

After the Kamakura period, there were other Buddhist schools founded throughout the history of Japan, though none have attained the influence of the earlier traditions on the island. Some of these later schools include:

* The Ōbaku School of Zen was introduced by Ingen

Ingen Ryūki () (December 7, 1592 – May 19, 1673) was a Chinese poet, calligrapher, and monk of Linji Chan Buddhism from China.Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Ingen" in ; n.b., Louis-Frédéric is pseudonym of Louis-Frédéric Nussbaum, ' ...

in 1654.

* Sanbo Kyodan (" Three Treasures Religious Organization"), a relatively new sect of Zen founded by Hakuun Yasutani

was a Sōtō rōshi, the founder of the Sanbo Kyodan organization of Japanese Zen.

Biography

Ryōkō Yasutani (安谷 量衡) was born in Japan in Shizuoka Prefecture. His family was very poor, and therefore he was adopted by another family. ...

in 1954

Japanese New Religious Movements

There are various Japanese New Religious movements which can be considered Buddhist sects, the largest of these are lay Nichiren Buddhist groups such as Soka Gakkai

is a Japanese Buddhist religious movement based on the teachings of the 13th-century Japanese priest Nichiren as taught by its first three presidents Tsunesaburō Makiguchi, Jōsei Toda, and Daisaku Ikeda. It is the largest of the Japanese ...

, Reiyūkai

, or Reiyūkai Shakaden, is a Japanese Buddhism, Buddhist Japanese new religions, new religious movement founded in 1919 by Kakutarō Kubo (1892-1944) and Kimi Kotani (1901-1971). It is a laity, lay organization (there are no priests) inspired by ...

and Risshō Kōsei-kai. But there are other new movements such as Agon Shū (阿含宗, ''"Agama School"''), a Buddhist school which focuses on studying the '' Agamas'', a collection of early Buddhist scriptures.

Cultural influence

Societal influence

During the Kamakura (1185–1333) and Muromachi (1336–1573) Buddhism, or the Buddhist institutions, had a great influence on Japanese society. Buddhist institutions were used by the shogunate to control the country. During the Edo (1600–1868) this power was constricted, to be followed by persecutions at the beginning of the Meiji restoration (1868–1912). Buddhist temples played a major administrative role during the Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional ''daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was character ...

, through the Danka or ''terauke'' system. In this, Japanese citizens were required to register at their local Buddhist temples and obtain a certification (''terauke''), which became necessary to function in society. At first, this system was put into place to suppress Christianity, but over time it took on the larger role of census and population control.

Artistic influence

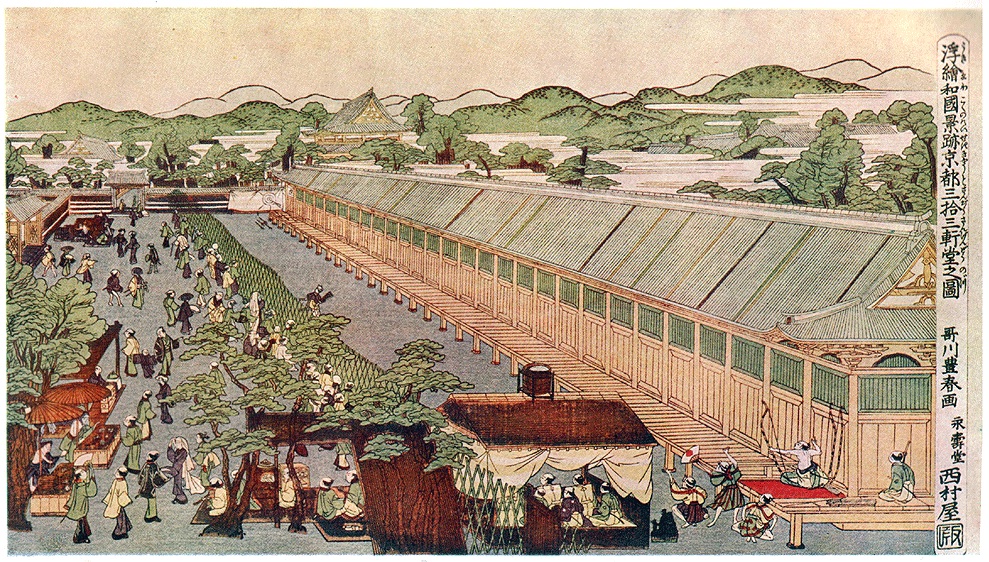

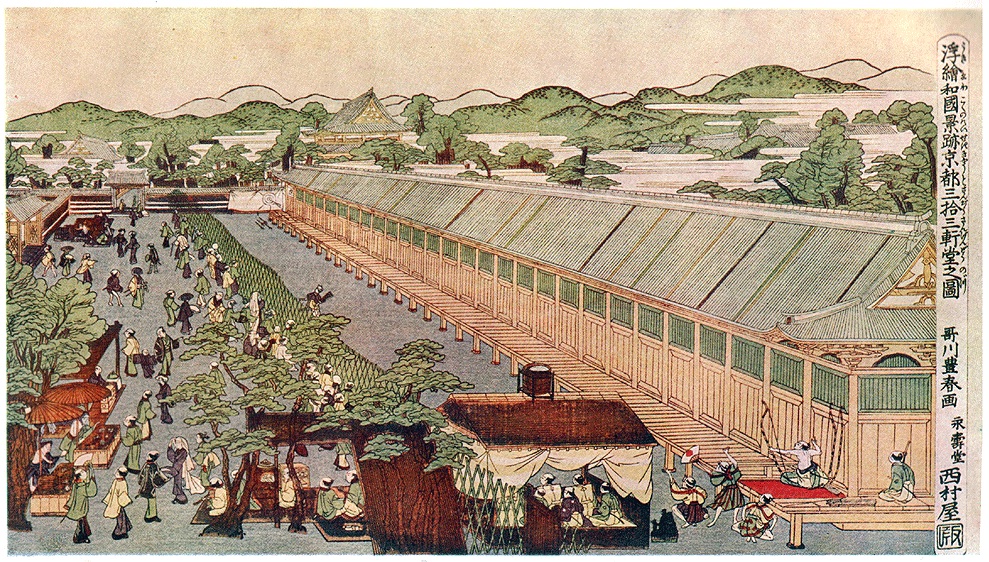

In Japan, Buddhist art started to develop as the country converted to Buddhism in 548. Some tiles from the

In Japan, Buddhist art started to develop as the country converted to Buddhism in 548. Some tiles from the Asuka period

The was a period in the history of Japan lasting from 538 to 710 (or 592 to 645), although its beginning could be said to overlap with the preceding Kofun period. The Yamato polity evolved greatly during the Asuka period, which is named after t ...

(shown above), the first period following the conversion of the country to Buddhism, display a strikingly classical style, with ample Hellenistic dress and realistically rendered body shape characteristic of Greco-Buddhist art

The Greco-Buddhist art or Gandhara art of the north Indian subcontinent is the artistic manifestation of Greco-Buddhism, a cultural syncretism between Ancient Greek art and Buddhism. It had mainly evolved in the ancient region of Gandhara.

The s ...

.

Buddhist art became extremely varied in its expression. Many elements of Greco-Buddhist art remain to this day however, such as the Hercules inspiration behind the Nio guardian deities in front of Japanese Buddhist temples, or representations of the Buddha reminiscent of Greek art such as the Buddha in Kamakura

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

Kamakura has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 persons per km² over the total area of . Kamakura was designated as a city on 3 November 1939.

Kamak ...

.

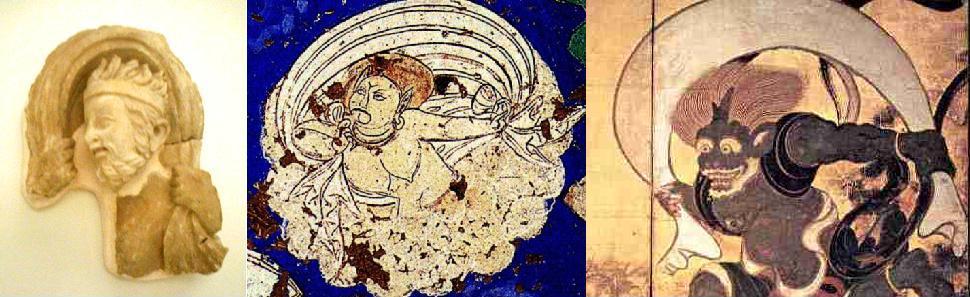

Deities

Various other Greco-Buddhist artistic influences can be found in the Japanese Buddhist pantheon, the most striking being that of the Japanese wind god Fūjin. In consistency with Greek iconography for the wind god Boreas, the Japanese wind god holds above his head with his two hands a draping or "wind bag" in the same general attitude. The abundance of hair has been kept in the Japanese rendering, as well as exaggerated facial features.

Another Buddhist deity, Shukongōshin, one of the wrath-filled protector deities of Buddhist temples in Japan, is also an interesting case of transmission of the image of the famous Greek god Heracles to East Asia along the

Various other Greco-Buddhist artistic influences can be found in the Japanese Buddhist pantheon, the most striking being that of the Japanese wind god Fūjin. In consistency with Greek iconography for the wind god Boreas, the Japanese wind god holds above his head with his two hands a draping or "wind bag" in the same general attitude. The abundance of hair has been kept in the Japanese rendering, as well as exaggerated facial features.

Another Buddhist deity, Shukongōshin, one of the wrath-filled protector deities of Buddhist temples in Japan, is also an interesting case of transmission of the image of the famous Greek god Heracles to East Asia along the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and reli ...

. Heracles was used in Greco-Buddhist art to represent Vajrapani, the protector of the Buddha, and his representation was then used in China and Japan to depict the protector gods of Buddhist temples.

Artistic motifs

The artistic inspiration from Greek floral scrolls is found quite literally in the decoration of Japanese roof tiles, one of the only remaining element of wooden architecture throughout centuries. The clearest ones are from the 7th century Nara temple building tiles, some of them exactly depicting vines and grapes. These motifs have evolved towards more symbolic representations, but essentially remain to this day in many Japanese traditional buildings.

The artistic inspiration from Greek floral scrolls is found quite literally in the decoration of Japanese roof tiles, one of the only remaining element of wooden architecture throughout centuries. The clearest ones are from the 7th century Nara temple building tiles, some of them exactly depicting vines and grapes. These motifs have evolved towards more symbolic representations, but essentially remain to this day in many Japanese traditional buildings.

Architecture and Temples

Soga no Umako built Hōkō-ji, the first temple in Japan, between 588 and 596. It was later renamed as Asuka-dera for Asuka, the name of the capital where it was located. Unlike early Shinto shrine

A is a structure whose main purpose is to house ("enshrine") one or more ''kami'', the deities of the Shinto religion.

Overview

Structurally, a Shinto shrine typically comprises several buildings.

The '' honden''Also called (本殿, meani ...

s, early Buddhist temple

A Buddhist temple or Buddhist monastery is the place of worship for Buddhists, the followers of Buddhism. They include the structures called vihara, chaitya, stupa, wat and pagoda in different regions and languages. Temples in Buddhism represen ...

s were highly ornamental and strictly symmetrical. The early Heian period (9th–10th century) saw an evolution of style based on the mikkyō sects Tendai and Shingon Buddhism. The Daibutsuyō style and the Zenshūyō

is a Japanese Buddhist architectural style derived from Chinese Song Dynasty architecture. Named after the Zen sect of Buddhism which brought it to Japan, it emerged in the late 12th or early 13th century. Together with Wayō and Daibutsuyō, ...

style emerged in the late 12th or early 13th century.

Buddhist holidays

The following Japanese Buddhist holidays are celebrated by most, if not all, major Buddhist traditions:Spring Equinox Spring equinox or vernal equinox or variations may refer to:

* March equinox, the spring equinox in the Northern Hemisphere

* September equinox, the spring equinox in the Southern Hemisphere

Other uses

* Nowruz, Persian/Iranian new year which be ...

celebration.

* Apr. 8th – Buddha's Birthday ''(Hanamatsuri''), i.e. Kanbutsu-e (潅仏会) or ''Busshō-e'' (仏生会).

* July – Aug. – '' Obon Festival,'' a festival to honor the spirits of one's ancestors.

* Sept. 21st, approximately – '' Higan-e'', the Autumnal Equinox celebration.

* Dec. 8th – Bodhi Day (''Shaka-Jōdō-e'' or just ''Jōdō-e''), this celebrated the awakening of the Buddha

* Dec. 31st – ''Jōya-e'' or ''Sechibun-E'', the end of the year celebration.

Some holidays are specific to certain schools or traditions. For example, Zen Buddhist traditions celebrate ''Daruma-ki'' on October 15 to commemorate the life of Bodhidharma

Bodhidharma was a semi-legendary Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th or 6th century CE. He is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China, and regarded as its first Chinese patriarch. According to a 17th century apo ...

.

See also

* Japanese Buddhist architecture

* Buddhist deities

* Buddhist modernism

* Buddhist philosophy

* History of Buddhism

* Ichibata Yakushi Kyodan

Ichibata Yakushi Kyōdan is an independent school of Buddhism in Japan which places great importance on what they term ''genze riyaku'' (faith) in Yakushi (Medicine Buddha). Previously affiliated with the Tendai and then the Myōshin-ji branch of ...

* Japanese Buddhist pantheon

* Kaichō

, from the Edo period of Japan onwards, was the public exhibition of religious objects from Buddhist temples, usually relics or statuary, that were normally not on display. Such exhibitions were often the bases for public fairs, which would invo ...

* Kanjin

* Nara National Museum

* Religion in Japan

* Shinbutsu-shūgō

''Shinbutsu-shūgō'' (, "syncretism of kami and buddhas"), also called Shinbutsu shū (, "god buddha school") Shinbutsu-konkō (, "jumbling up" or "contamination of kami and buddhas"), is the syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism that was Japan's o ...

* Shinbutsu kakuri

* Shinbutsu bunri

The Japanese term indicates the separation of Shinto from Buddhism, introduced after the Meiji Restoration which separated Shinto ''kami'' from buddhas, and also Buddhist temples from Shinto shrines, which were originally amalgamated. It is a ...

* Haibutsu kishaku

Notes

References

Bibliography

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

*Asakawa, K., and Henry Cabot Lodge (Ed.). ''Japan From the Japanese Government History''.

* Eliot, Sir Charles. ''Japanese Buddhism''. London: Kegan Paul International, 2005. . Reprint of the 1935 original edition.

* Bunyiu Nanjio (1886)

A short history of the twelve Japanese Buddhist sects

Tokyo: Bukkyo-sho-ei-yaku-shupan-sha

* Covell, Stephen (2001)

"Living Temple Buddhism in Contemporary Japan: The Tendai Sect Today"

Comparative Religion Publications. Paper 1. (Dissertation, Western Michigan University)

*Covell, Stephen G. (2006). "Japanese Temple Buddhism: Worldliness in a Religion of Renunciation", Univ of Hawaii.

* Horii, Mitsutoshi (2006)

Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies 6 (1), unpaginated

*Kawanami, Hiroko: Japanese Nationalism and the Universal Dharma, in: Ian Harris (ed.): ''Buddhism and Politics in Twentieth-Century Asia''. London/New York: Continuum, 1999, pp. 105–126.

* Matsunaga, Daigan; Matsunaga, Alicia (1996), Foundation of Japanese buddhism, Vol. 1: The Aristocratic Age, Los Angeles; Tokyo: Buddhist Books International.

* Matsunaga, Daigan, Matsunaga, Alicia (1996), Foundation of Japanese buddhism, Vol. 2: The Mass Movement (Kamakura and Muromachi Periods), Los Angeles; Tokyo: Buddhist Books International, 1996.

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Buddhism In Japan

Buddhism in Asia

Religion in Japan

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

The '' Nihon Shoki'' (''Chronicles of Japan'') provides a date of 552 for when King

The '' Nihon Shoki'' (''Chronicles of Japan'') provides a date of 552 for when King  Based on traditional sources, Shōtoku has been seen as an ardent Buddhist who taught, wrote on, and promoted Buddhism widely, especially during the reign of Empress Suiko (554 – 15 April 628). He is also believed to have sent envoys to China and is even seen as a spiritually accomplished

Based on traditional sources, Shōtoku has been seen as an ardent Buddhist who taught, wrote on, and promoted Buddhism widely, especially during the reign of Empress Suiko (554 – 15 April 628). He is also believed to have sent envoys to China and is even seen as a spiritually accomplished

In 710, Empress Genme moved the state capital to Heijōkyō, (modern Nara) thus inaugurating the Nara period. This period saw the establishment of the ''kokubunji'' system, which was a way to manage provincial temples through a network of national temples in each province. The head temple of the entire system was Tōdaiji.

Nara state sponsorship saw the development of the six great Nara schools, called , all were continuations of Chinese Buddhist schools. The temples of these schools became important places for the study of Buddhist doctrine. The six Nara schools were: '' Ritsu'' (