In a protracted conflict during the

Spanish colonization of the Americas

Spain began colonizing the Americas under the Crown of Castile and was spearheaded by the Spanish . The Americas were invaded and incorporated into the Spanish Empire, with the exception of Brazil, British America, and some small regions ...

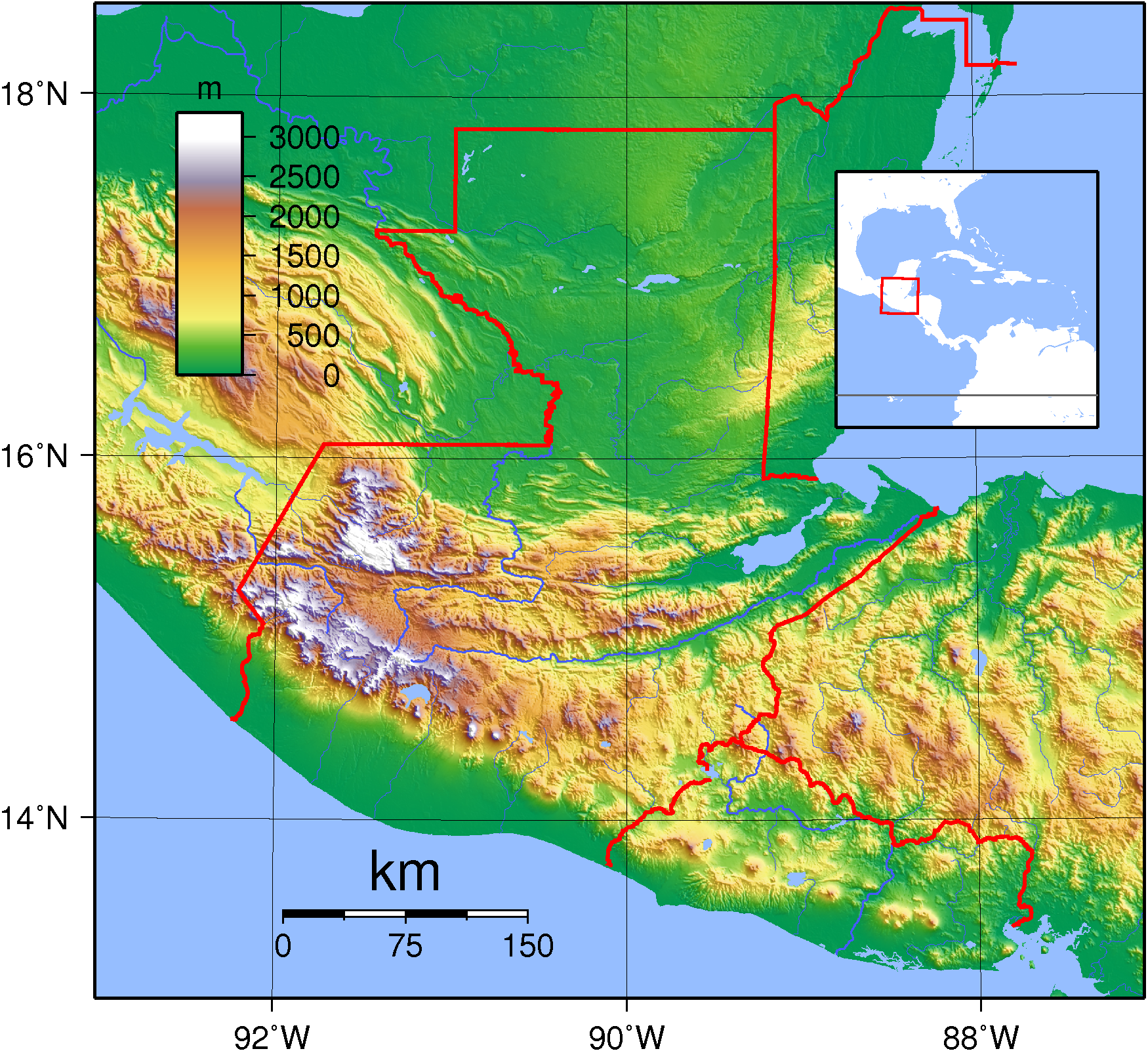

, Spanish colonisers gradually incorporated the territory that became the modern country of

Guatemala

Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico; to the northeast by Belize and the Caribbean; to the east by Hon ...

into the colonial Viceroyalty of

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the A ...

. Before the conquest, this territory contained a number of competing

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Wit ...

n kingdoms, the majority of which were

Maya

Maya may refer to:

Civilizations

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Maya language, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (Ethiopia), a popul ...

. Many

conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, ...

s viewed the Maya as "

infidel

An infidel (literally "unfaithful") is a person accused of disbelief in the central tenets of one's own religion, such as members of another religion, or the irreligious.

Infidel is an ecclesiastical term in Christianity around which the Church ...

s" who needed to be forcefully converted and pacified, disregarding the achievements of their

civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

.

[Jones 2000, p. 356.] The first contact between the Maya and

European explorers came in the early 16th century when a

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

ship sailing from

Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

to

Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

was wrecked on the east coast of the

Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula (, also , ; es, Península de Yucatán ) is a large peninsula in southeastern Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north ...

in 1511.

Several Spanish expeditions followed in 1517 and 1519, making landfall on various parts of the Yucatán coast. The Spanish conquest of the Maya was a prolonged affair; the Maya kingdoms resisted integration into the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

with such tenacity that their defeat took almost two centuries.

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration of the coasts of the Yucat ...

arrived in Guatemala from the

newly conquered Mexico in early 1524, commanding a mixed force of Spanish conquistadors and native allies, mostly from

Tlaxcala

Tlaxcala (; , ; from nah, Tlaxcallān ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tlaxcala ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tlaxcala), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. It is ...

and

Cholula. Geographic features across Guatemala now bear

Nahuatl

Nahuatl (; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have small ...

placenames owing to the influence of these Mexican allies, who translated for the Spanish.

The

Kaqchikel Maya initially allied themselves with the Spanish, but soon rebelled against excessive demands for tribute and did not finally surrender until 1530. In the meantime the other major highland Maya kingdoms had each been defeated in turn by the Spanish and allied warriors from Mexico and already subjugated Maya kingdoms in Guatemala. The

Itza Maya Itza may refer to:

* Itza people, an ethnic group of Guatemala

* Itzaʼ language, a Mayan language

* Itza Kingdom (disambiguation)

* Itza, Navarre, a town in Spain

See also

* Chichen Itza, a Mayan city

* Iza (disambiguation)

* Izza (disambiguat ...

and other lowland groups in the

Petén Basin

The Petén Basin is a geographical subregion of Mesoamerica, primarily located in northern Guatemala within the Department of El Petén, and into Campeche state in southeastern Mexico.

During the Late Preclassic and Classic periods of pre-Col ...

were first contacted by

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

in 1525, but remained independent and hostile to the encroaching Spanish until 1697, when a concerted Spanish assault led by

Martín de Ursúa y Arizmendi finally defeated the last independent Maya kingdom.

Spanish and native tactics and technology differed greatly. The Spanish viewed the taking of prisoners as a hindrance to outright victory, whereas the Maya prioritised the capture of live prisoners and of booty. The

indigenous peoples of Guatemala

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the A ...

lacked key elements of

Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by thei ...

technology such as a functional

wheel

A wheel is a circular component that is intended to rotate on an axle bearing. The wheel is one of the key components of the wheel and axle which is one of the six simple machines. Wheels, in conjunction with axles, allow heavy objects to be ...

, horses, iron, steel, and

gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

; they were also extremely susceptible to Old World diseases, against which they had no resistance. The Maya preferred raiding and ambush to large-scale

warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regu ...

, using spears, arrows and wooden swords with inset

obsidian

Obsidian () is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock.

Obsidian is produced from felsic lava, rich in the lighter elements such as silicon ...

blades; the

Xinca of the southern coastal plain used

poison

Poison is a chemical substance that has a detrimental effect to life. The term is used in a wide range of scientific fields and industries, where it is often specifically defined. It may also be applied colloquially or figuratively, with a broa ...

on their arrows. In response to the use of Spanish cavalry, the highland Maya took to digging pits and lining them with wooden stakes.

Historical sources

The sources describing the Spanish conquest of Guatemala include those written by the Spanish themselves, among them two of four letters written by conquistador

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration of the coasts of the Yucat ...

to

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

in 1524, describing the initial campaign to subjugate the

Guatemalan Highlands

The Guatemalan Highlands is an upland region in southern Guatemala, lying between the Sierra Madre de Chiapas to the south and the Petén lowlands to the north.

Description

The highlands are made up of a series of high valleys enclosed by mount ...

. These letters were despatched to

Tenochtitlan

, ; es, Tenochtitlan also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, ; es, México-Tenochtitlan was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear. The date 13 March 1325 was ...

, addressed to Cortés but with a royal audience in mind; two of these letters are now lost.

Gonzalo de Alvarado y Chávez

Gonzalo de Alvarado y Chávez was a Spanish conquistador and cousin of Pedro de Alvarado and accompanied him on his first campaign in Guatemala. In 1525 he was appointed chief constable of Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala, the new capital ( ...

was Pedro de Alvarado's cousin; he accompanied him on his first campaign in Guatemala and in 1525 he became the chief

constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in criminal law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. A constable is commonly the rank of an officer within the police. Other peop ...

of

Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala

Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala ("St. James of the Knights of Guatemala") was the name given to the capital city of the Spanish colonial Captaincy General of Guatemala in Central America.

History

;Quauhtemallan — Guatemala

:The name was ...

, the newly founded Spanish capital. Gonzalo wrote an account that mostly supports that of Pedro de Alvarado. Pedro de Alvarado's brother

Jorge

Jorge is a Spanish and Portuguese given name. It is derived from the Greek name Γεώργιος (''Georgios'') via Latin ''Georgius''; the former is derived from (''georgos''), meaning "farmer" or "earth-worker".

The Latin form ''Georgius'' ...

wrote another account to the king of Spain that explained it was his own campaign of 1527–1529 that established the Spanish colony.

[Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p. 49.] Bernal Díaz del Castillo

Bernal Díaz del Castillo ( 1492 – 3 February 1584) was a Spanish conquistador, who participated as a soldier in the conquest of the Aztec Empire under Hernán Cortés and late in his life wrote an account of the events. As an experience ...

wrote a lengthy account of the conquest of the Aztec Empire and neighbouring regions, the ''

Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España'' ("True History of the Conquest of New Spain"); his account of the conquest of Guatemala generally agrees with that of the Alvarados. His account was finished around 1568, some 40 years after the campaigns it describes. Hernán Cortés described his expedition to

Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

in the fifth letter of his ''Cartas de Relación'', in which he details his crossing of what is now Guatemala's

Petén Department

Petén is a department of Guatemala. It is geographically the northernmost department of Guatemala, as well as the largest by area at it accounts for about one third of Guatemala's area. The capital is Flores. The population at the mid-2018 o ...

.

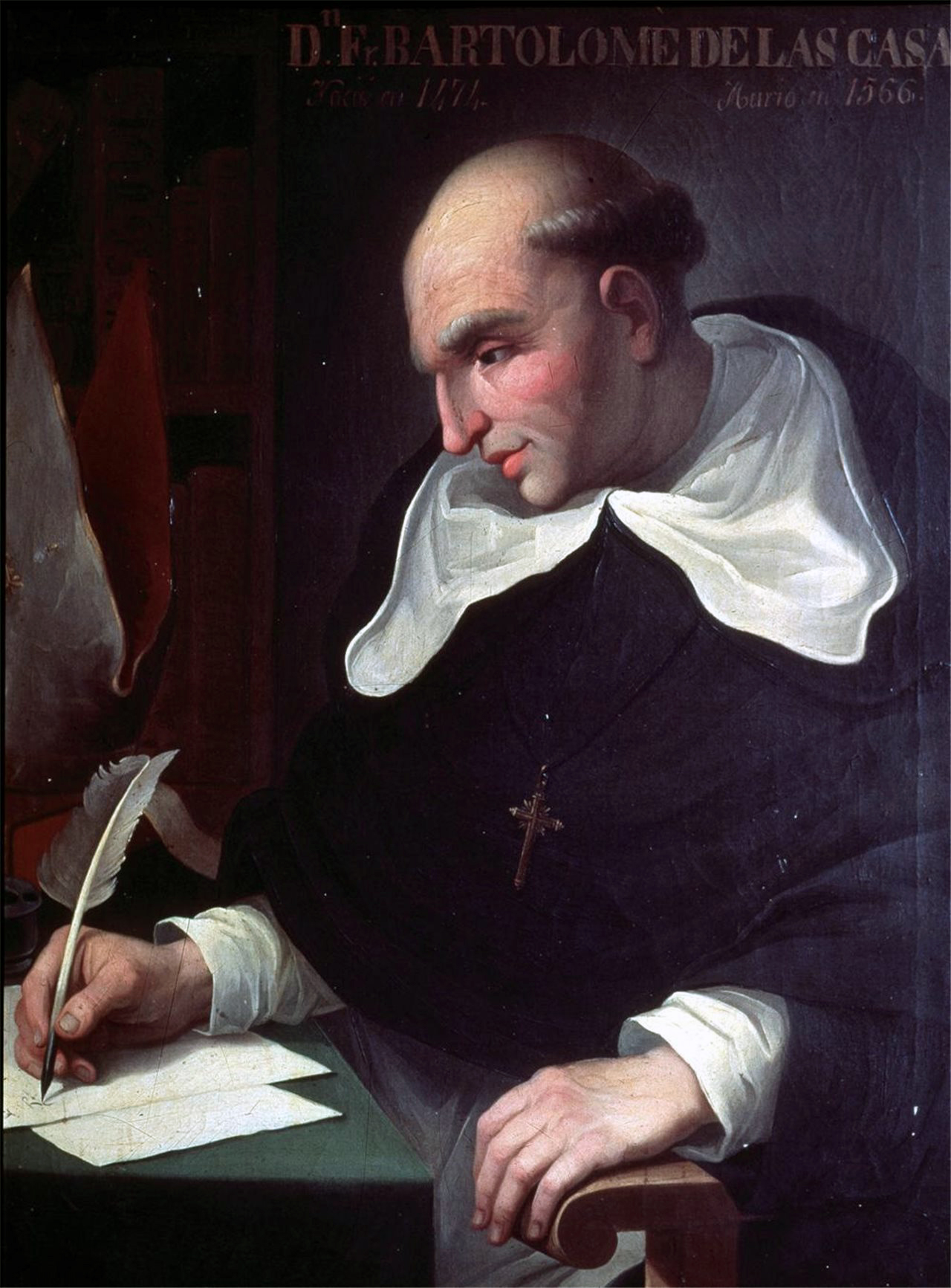

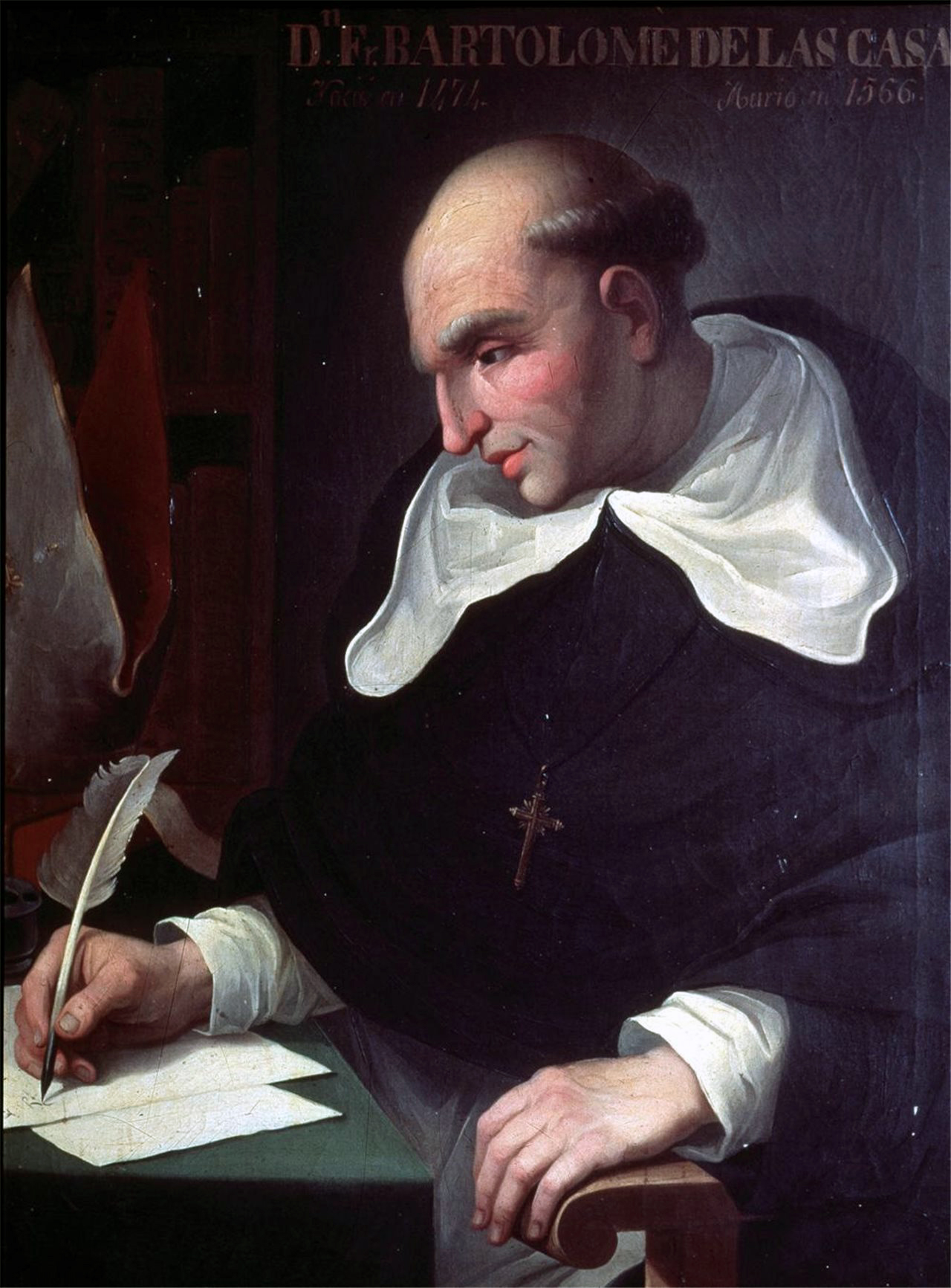

Dominican friar

Bartolomé de las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, OP ( ; ; 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman then became a Dominican friar ...

wrote a highly critical account of the Spanish conquest of the Americas and included accounts of some incidents in Guatemala. The ''

Brevísima Relación de la Destrucción de las Indias'' ("Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies") was first published in 1552 in

Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

.

The

Tlaxcalan

Tlaxcala (; , ; from nah, Tlaxcallān ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tlaxcala ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tlaxcala), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 60 municipaliti ...

allies of the Spanish who accompanied them in their invasion of Guatemala wrote their own accounts of the conquest; these included a letter to the Spanish king protesting at their poor treatment once the campaign was over. Other accounts were in the form of questionnaires answered before colonial magistrates to protest and register a claim for recompense. Two pictorial accounts painted in the stylised indigenous pictographic tradition have survived; these are the ''

Lienzo de Quauhquechollan

The Lienzo de Quauhquechollan ("Quauhquechollan Cloth") is a 16th-century '' lienzo'' (cloth painting) of the Nahua, a group of indigenous peoples of Mexico. It is one of two surviving Nahua pictorial records recounting the Spanish conquest of Gua ...

'', which was probably painted in

Ciudad Vieja

Ciudad Vieja () is a town and municipality in the Guatemalan department of Sacatepéquez. According to the 2018 census, the town has a population of 32,802 in the 1530s, and the ''

Lienzo de Tlaxcala

''History of Tlaxcala'' (Spanish: ''Historia de Tlaxcala'') is an alphabetic text in Spanish with illustrations written by and under the supervision of Diego Muñoz Camargo in the years leading up to 1585.

Muñoz Camargo's work is divided into t ...

'', painted in Tlaxcala.

Accounts of the conquest as seen from the point of view of the defeated highland Maya kingdoms are included in a number of indigenous documents, including the ''

Annals of the Kaqchikels'', which includes the Xajil Chronicle describing the history of the Kaqchikel from their mythical creation down through the Spanish conquest and continuing to 1619. A letter from the defeated

Tzʼutujil Maya nobility of

Santiago Atitlán

Santiago Atitlán (, from Nahuatl ''atitlan'', "at the water", in Tz'utujil ''Tz'ikin Jaay'', "birdhouse") is a municipality in the Sololá department of Guatemala. The town is situated on Lake Atitlán, which has an elevation of . The town s ...

to the Spanish king written in 1571 details the exploitation of the subjugated peoples.

[Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p. 111.]

Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán

Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán (1643–1700) was a Guatemalan '' criollo'' historian and poet. His only surviving work is the '' Recordación Florida''.

Biography

Fuentes y Guzmán was born to a wealthy family in Santiago de los Caballer ...

was a colonial Guatemalan historian of Spanish descent who wrote ''La Recordación Florida'', also called ''Historia de Guatemala'' (''History of Guatemala''). The book was written in 1690 and is regarded as one of the most important works of Guatemalan history, and is the first such book to have been written by a

criollo

Criollo or criolla (Spanish for creole) may refer to:

People

* Criollo people, a social class in the Spanish race-based colonial caste system (the European descendants)

Animals

* Criollo duck, a species of duck native to Central and South Ameri ...

author. Field investigation has tended to support the estimates of indigenous population and army sizes given by Fuentes y Guzmán.

Background

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

discovered the New World for the

Kingdom of Castile and León in 1492. Private adventurers thereafter entered into contracts with the Spanish Crown to conquer the newly discovered lands in return for tax revenues and the power to rule. In the first decades after the discovery of the new lands, the Spanish colonised the

Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

and established a centre of operations on the island of

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

. They heard rumours of the rich empire of the

Aztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl ...

s on the mainland to the west and, in 1519,

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

set sail with eleven ships to explore the Mexican coast. By August 1521 the Aztec capital of

Tenochtitlan

, ; es, Tenochtitlan also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, ; es, México-Tenochtitlan was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear. The date 13 March 1325 was ...

had

fallen to the Spanish and their allies. A single soldier arriving in

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

in 1520 was carrying

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and thus initiated the devastating plagues that swept through the native populations of the Americas. Within three years of the fall of Tenochtitlan the Spanish had conquered a large part of Mexico, extending as far south as the

Isthmus of Tehuantepec

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec () is an isthmus in Mexico. It represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. Before the opening of the Panama Canal, it was a major overland transport route known simply as the T ...

. The newly conquered territory became

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the A ...

, headed by a

viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

who answered to the king of Spain via the

Council of the Indies

The Council of the Indies ( es, Consejo de las Indias), officially the Royal and Supreme Council of the Indies ( es, Real y Supremo Consejo de las Indias, link=no, ), was the most important administrative organ of the Spanish Empire for the Amer ...

. Hernán Cortés received reports of rich, populated lands to the south and dispatched

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration of the coasts of the Yucat ...

to investigate the region.

[Lovell 2005, p. 58.]

Preparations

In the run-up to the announcement that an invasion force was to be sent to Guatemala, 10,000

Nahua

The Nahuas () are a group of the indigenous people of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. They comprise the largest indigenous group in Mexico and second largest in El Salvador. The Mexica (Aztecs) were of Nahua ethnicity, a ...

warriors had already been assembled by the Aztec emperor

Cuauhtémoc

Cuauhtémoc (, ), also known as Cuauhtemotzín, Guatimozín, or Guatémoc, was the Aztec ruler ('' tlatoani'') of Tenochtitlan from 1520 to 1521, making him the last Aztec Emperor. The name Cuauhtemōc means "one who has descended like an eagle ...

to accompany the Spanish expedition. Warriors were ordered to be gathered from each of the

Mexica

The Mexica (Nahuatl: , ;''Nahuatl Dictionary.'' (1990). Wired Humanities Project. University of Oregon. Retrieved August 29, 2012, frolink/ref> singular ) were a Nahuatl-speaking indigenous people of the Valley of Mexico who were the rulers of ...

and

Tlaxcaltec

The Tlaxcalans, or Tlaxcaltecs, are a Nahua people who live in the Mexican state of Tlaxcala.

Pre-Columbian history

The Tlaxcaltecs were originally a conglomeration of three distinct ethnic groups who spoke Nahuatl, Otomi, and Pinome that compr ...

towns. The native warriors supplied their weapons, including swords, clubs and bows and arrows. Alvarado's army left Tenochtitlan at the beginning of the dry season, sometime between the second half of November and December 1523. As

Alvarado left the Aztec capital, he led about 400 Spanish and approximately 200

Tlaxcalan

Tlaxcala (; , ; from nah, Tlaxcallān ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tlaxcala ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tlaxcala), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 60 municipaliti ...

and

Cholulan warriors and 100

Mexica

The Mexica (Nahuatl: , ;''Nahuatl Dictionary.'' (1990). Wired Humanities Project. University of Oregon. Retrieved August 29, 2012, frolink/ref> singular ) were a Nahuatl-speaking indigenous people of the Valley of Mexico who were the rulers of ...

, meeting up with the gathered reinforcements on the way. When the army left the

Basin of Mexico, it may have included as many as 20,000 native warriors from various kingdoms, although the exact numbers are disputed. By the time the army crossed the

Isthmus of Tehuantepec

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec () is an isthmus in Mexico. It represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. Before the opening of the Panama Canal, it was a major overland transport route known simply as the T ...

, the massed native warriors included 800 from

Tlaxcala

Tlaxcala (; , ; from nah, Tlaxcallān ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tlaxcala ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tlaxcala), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. It is ...

, 400 from

Huejotzingo

Huejotzingo ( is a small city and municipality located just northwest of the city of Puebla, in central Mexico. The settlement's history dates back to the pre-Hispanic period, when it was a dominion, with its capital a short distance from where th ...

, 1,600 from

Tepeaca plus many more from other former Aztec territories. Further Mesoamerican warriors were recruited from the

Zapotec and

Mixtec

The Mixtecs (), or Mixtecos, are indigenous Mesoamerican peoples of Mexico inhabiting the region known as La Mixteca of Oaxaca and Puebla as well as La Montaña Region and Costa Chica Regions of the state of Guerrero. The Mixtec Cult ...

provinces, with the addition of more Nahuas from the Aztec garrison in

Soconusco

Soconusco is a region in the southwest corner of the state of Chiapas in Mexico along its border with Guatemala. It is a narrow strip of land wedged between the Sierra Madre de Chiapas mountains and the Pacific Ocean. It is the southernmost par ...

.

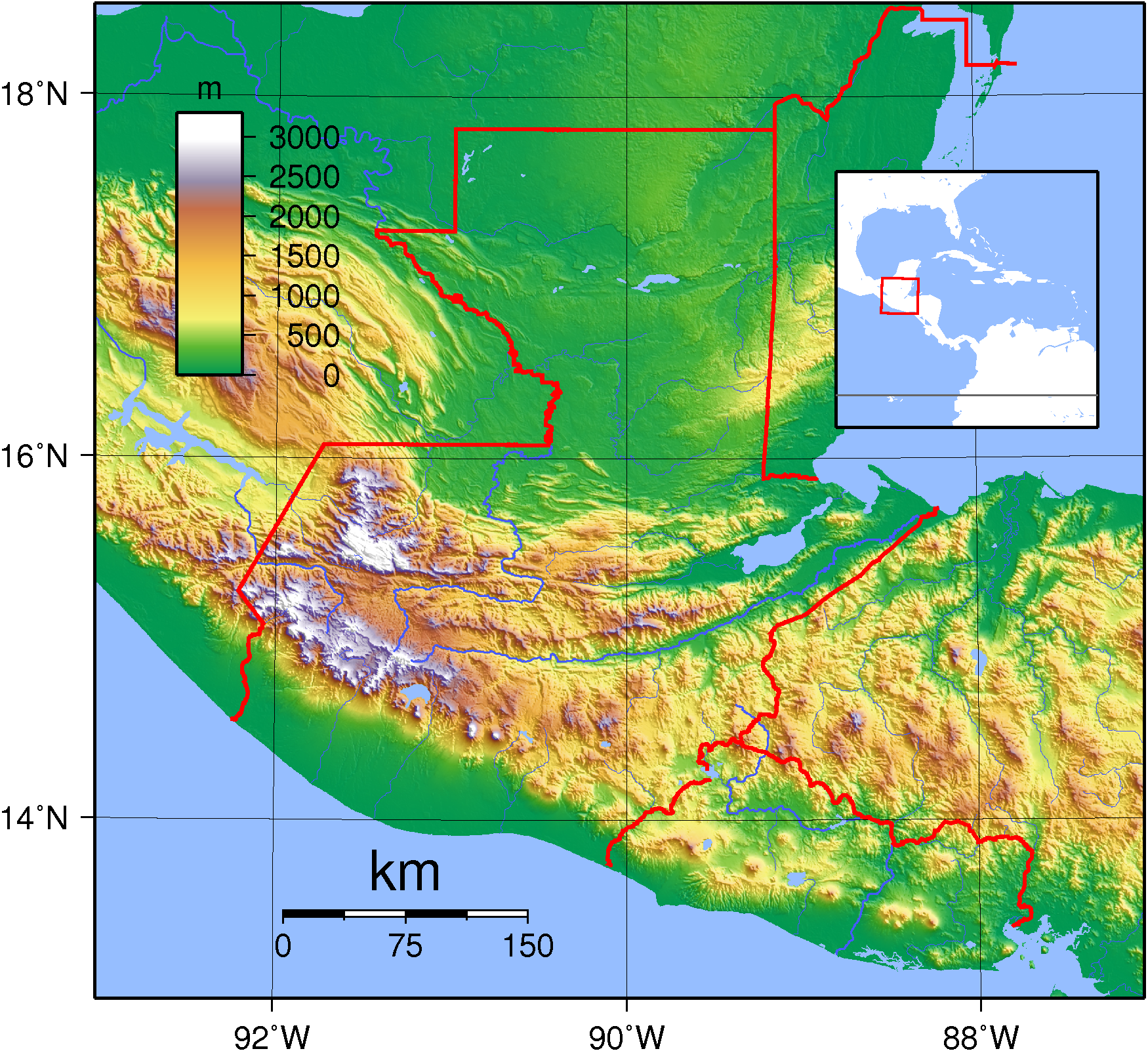

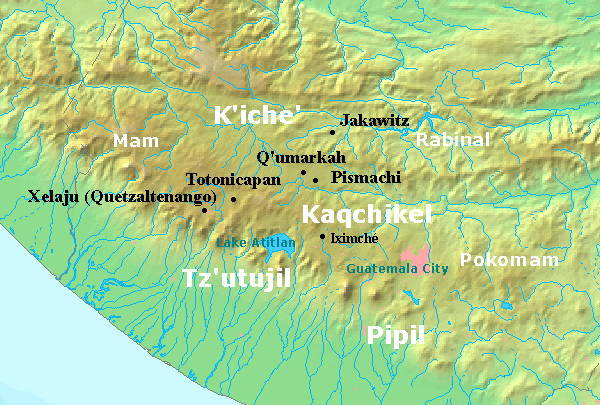

Guatemala before the conquest

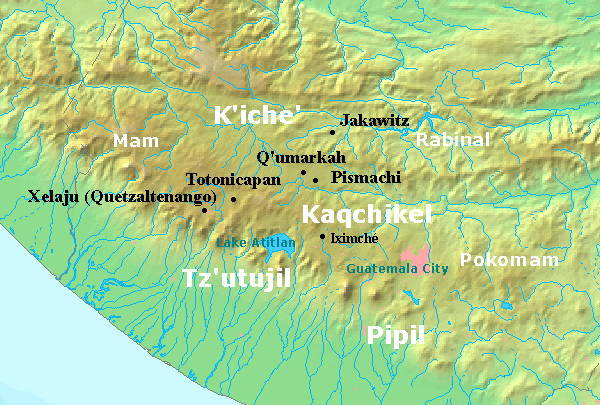

In the early 16th century the territory that now makes up Guatemala was divided into various competing polities, each locked in continual struggle with its neighbours. The most important were the

Kʼicheʼ, the

Kaqchikel, the

Tzʼutujil, the

Chajoma

The Chajoma () were a Kaqchikel-speaking Maya people of the Late Postclassic period, with a large kingdom in the highlands of Guatemala. According to the indigenous chronicles of the K'iche' and the Kaqchikel, there were three principal Postcla ...

, the

Mam

Mam or MAM may refer to:

Places

* An Mám or Maum, a settlement in Ireland

* General Servando Canales International Airport in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico (IATA Code: MAM)

* Isle of Mam, a phantom island

* Mam Tor, a hill near Castleton in th ...

, the

Poqomam and the

Pipil Pipil may refer to:

*Nahua people of western El Salvador

*Pipil language

Nawat (academically Pipil, also known as Nicarao) is a Nahuan language native to Central America. It is the southernmost extant member of the Uto-Aztecan family. It was spo ...

.

[Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p. 6.] All were Maya groups except for the Pipil, who were a

Nahua

The Nahuas () are a group of the indigenous people of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. They comprise the largest indigenous group in Mexico and second largest in El Salvador. The Mexica (Aztecs) were of Nahua ethnicity, a ...

group related to the

Aztecs

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl ...

; the Pipil had a number of small

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s along the Pacific coastal plain of southern Guatemala and

El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south ...

.

[Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p. 25.] The Pipil of Guatemala had their capital at Itzcuintepec. The

Xinca were another non-Maya group occupying the southeastern Pacific coastal area. The Maya had never been unified as a single empire, but by the time the Spanish arrived Maya civilization was thousands of years old and had already seen the rise and fall of

great cities.

[Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p. 4.]

On the eve of the conquest the

highlands of Guatemala were dominated by several powerful Maya states. In the centuries preceding the arrival of the Spanish the Kʼicheʼ had carved out a small empire covering a large part of the western

Guatemalan Highlands

The Guatemalan Highlands is an upland region in southern Guatemala, lying between the Sierra Madre de Chiapas to the south and the Petén lowlands to the north.

Description

The highlands are made up of a series of high valleys enclosed by mount ...

and the neighbouring Pacific coastal plain. However, in the late 15th century the Kaqchikel rebelled against their former Kʼicheʼ allies and founded a new kingdom to the southeast with

Iximche

Iximcheʼ () (or Iximché using Spanish orthography) is a Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican archaeological site in the western highlands of Guatemala. Iximche was the capital of the Late Postclassic Kaqchikel Maya kingdom from 1470 until its abandonm ...

as its capital. In the decades before the Spanish invasion the Kaqchikel kingdom had been steadily eroding the kingdom of the Kʼicheʼ.

[Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p. 5.] Other highland groups included the Tzʼutujil around

Lake Atitlán

Lake Atitlán ( es, links=no, Lago de Atitlán, ) is a lake in the Guatemalan Highlands of the Sierra Madre mountain range. The lake is located in the Sololá Department of southwestern Guatemala. It is known as the deepest lake in Central Ameri ...

, the Mam in the western highlands and the Poqomam in the eastern highlands.

The kingdom of the

Itza was the most powerful polity in the Petén lowlands of northern Guatemala,

[Rice 2009, p. 17.] centred on their capital

Nojpetén

Nojpetén (also spelled Noh Petén, and also known as Tayasal) was the capital city of the Itza Maya kingdom of Petén Itzá. It is located on an island in Lake Petén Itzá in the modern department of Petén in northern Guatemala. The island ...

, on an island in

Lake Petén Itzá

Lake Petén Itzá (''Lago Petén Itzá'', ) is a lake in the northern Petén Department in Guatemala. It is the third largest lake in Guatemala, after Lake Izabal and Lake Atitlán. It is located around . It has an area of , and is some long an ...

.

[While most sources accept the modern town of Flores on Lake Petén Itzá as the location of Nojpetén/Tayasal, Arlen Chase argued that this identification is incorrect and that descriptions of Nojpetén correspond better to the archaeological site of ]Topoxte

Topoxte () (or Topoxté in Spanish orthography) is a pre-Columbian Maya archaeological site in the Petén Basin in northern Guatemala with a long occupational history dating as far back as the Middle Preclassic.Pinto & Noriega 1995, pp.576–7. ...

on Lake Yaxha. Chase 1976. See also the detailed rebuttal by Jones, Rice and Rice 1981. The second polity in importance was that of their hostile neighbours, the

Kowoj. The Kowoj were located to the east of the Itza, around the eastern lakes: Lake Salpetén, Lake Macanché,

Lake Yaxhá and Lake Sacnab. Other groups are less well known and their precise territorial extent and political makeup remains obscure; among them were the

Chinamita

The Chinamita or Tulumkis (Nahuatl ''chinamitl'', Mopan ''tulumki'') were a Mopan Maya people who occupied a territory in the eastern Petén Basin and western Belize between the Itza of Nojpetén, within the borders of modern Guatemala, and thei ...

, the

Kejache

The Kejache () (sometimes spelt Kehache, Quejache, Kehach, Kejach or Cehache) were a Maya people in northern Guatemala at the time of Spanish contact in the 17th century. The Kejache territory was located in the Petén Basin in a region that takes ...

, the Icaiche, the

Lakandon Chʼol, the

Mopan, the

Manche Chʼol and the

Yalain. The Kejache occupied an area north of the lake on the route to

Campeche

Campeche (; yua, Kaampech ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Campeche ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Campeche), is one of the 31 states which make up the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. Located in southeast Mexico, it is bordered by ...

, while the

Mopan and the

Chinamita

The Chinamita or Tulumkis (Nahuatl ''chinamitl'', Mopan ''tulumki'') were a Mopan Maya people who occupied a territory in the eastern Petén Basin and western Belize between the Itza of Nojpetén, within the borders of modern Guatemala, and thei ...

had their polities in the southeastern Petén. The Manche territory was to the southwest of the Mopan. The

Yalain had their territory immediately to the east of Lake Petén Itzá.

Native weapons and tactics

Maya warfare

Although the Maya were once thought to have been peaceful, current theories emphasize the role of inter-polity warfare as a factor in the development and perpetuation of Maya society. The goals and motives of warfare in Maya culture are not thorou ...

was not so much aimed at destruction of the enemy as the seizure of captives and plunder.

[Phillips 2006, 2007, p. 95.] The Spanish described the weapons of war of the Petén Maya as bows and arrows,

fire-sharpened poles, flint-headed spears and two-handed swords crafted from strong wood with the blade fashioned from inset

obsidian

Obsidian () is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock.

Obsidian is produced from felsic lava, rich in the lighter elements such as silicon ...

, similar to the Aztec ''

macuahuitl

A macuahuitl () is a weapon, a wooden club with several embedded obsidian blades. The name is derived from the Nahuatl language and means "hand-wood". Its sides are embedded with prismatic blades traditionally made from obsidian. Obsidian is ...

''.

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration of the coasts of the Yucat ...

described how the

Xinca of the Pacific coast attacked the Spanish with spears, stakes and poisoned arrows.

Maya warriors wore

body armour in the form of quilted cotton that had been soaked in salt water to toughen it; the resulting armour compared favourably to the steel armour worn by the Spanish. The Maya had historically employed ambush and raiding as their preferred tactic, and its employment against the Spanish proved troublesome for the Europeans.

[Phillips 2006, 2007, p. 94.] In response to the use of cavalry, the highland Maya took to digging pits on the roads, lining them with fire-hardened stakes and camouflaging them with grass and weeds, a tactic that according to the

Kaqchikel killed many horses.

Conquistadors

The conquistadors were all volunteers, the majority of whom did not receive a fixed salary but instead a portion of the spoils of victory, in the form of

precious metal

Precious metals are rare, naturally occurring metallic chemical elements of high economic value.

Chemically, the precious metals tend to be less reactive than most elements (see noble metal). They are usually ductile and have a high lu ...

s, land grants and provision of native labour. Many of the Spanish were already experienced soldiers who had previously campaigned in Europe.

[Polo Sifontes 1986, p. 62.] The initial incursion into Guatemala was led by

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration of the coasts of the Yucat ...

, who earned the military title of ''

Adelantado

''Adelantado'' (, , ; meaning "advanced") was a title held by Spanish nobles in service of their respective kings during the Middle Ages. It was later used as a military title held by some Spanish ''conquistadores'' of the 15th, 16th and 17th cen ...

'' in 1527; he answered to the

Spanish crown

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

via

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

in Mexico.

Other early conquistadors included Pedro de Alvarado's brothers

Gómez de Alvarado

Gómez de Alvarado y Contreras (; 1482 – September 1542) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' and explorer. He was a member of the Alvarado family and the older brother of the famous ''conquistador'' Pedro de Alvarado.

Alvarado participated in ...

,

Jorge de Alvarado

Jorge de Alvarado y Contreras (born c.1480 Badajoz, Extremadura, Spaindied Madrid 1540 or 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, brother of the more famous Pedro de Alvarado.Diaz, B., 1963, The Conquest of New Spain, London: Penguin Books,

Biograph ...

and

Gonzalo de Alvarado y Contreras

Gonzalo de Alvarado y Contreras was a Spanish conquistador and brother of Pedro de Alvarado who participated in campaigns in Mexico, Guatemala, and El Salvador (co-founding its present capital, San Salvador).

Gonzalo de Alvarado was a native of ...

; and his cousins

Gonzalo de Alvarado y Chávez

Gonzalo de Alvarado y Chávez was a Spanish conquistador and cousin of Pedro de Alvarado and accompanied him on his first campaign in Guatemala. In 1525 he was appointed chief constable of Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala, the new capital ( ...

,

Hernando de Alvarado Hernando de Alvarado (d. 1540s), was a Spanish conquistador and explorer, lieutenant under Francisco Vázquez de Coronado. In 1540s Coronado expedition into the American Southwest on August 29 1540 Hernando leading small military unit came upon Aco ...

and Diego de Alvarado.

was a nobleman who joined the initial invasion.

[Polo Sifontes 1986, p. 61.] Bernal Díaz del Castillo

Bernal Díaz del Castillo ( 1492 – 3 February 1584) was a Spanish conquistador, who participated as a soldier in the conquest of the Aztec Empire under Hernán Cortés and late in his life wrote an account of the events. As an experience ...

was a petty nobleman who accompanied Hernán Cortés when he crossed the northern lowlands, and Pedro de Alvarado on his invasion of the highlands. In addition to Spaniards, the invasion force probably included dozens of armed

African slaves

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa. Systems of servitude and slavery were common in parts of Africa in ancient times, as they were in much of the rest of the ancient world. When the trans-Saharan slave trade, Indian Ocean ...

and

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

.

Spanish weapons and tactics

Spanish weaponry and tactics differed greatly from that of the indigenous peoples of Guatemala. This included the Spanish use of

crossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an Elasticity (physics), elastic launching device consisting of a Bow and arrow, bow-like assembly called a ''prod'', mounted horizontally on a main frame called a ''tiller'', which is hand-held in a similar ...

s,

firearms

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes ...

(including

musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually di ...

s and

cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

),

war dogs

Dogs in warfare have a very long history starting in ancient times. From being trained in combat, to their use as scouts, sentries, messengers, mercy dogs, and trackers, their uses have been varied and some continue to exist in modern military ...

and

war horses.

Among Mesoamerican peoples the capture of prisoners was a priority, while to the Spanish such taking of prisoners was a hindrance to outright victory.

[Drew 1999, p. 382.] The inhabitants of Guatemala, for all their sophistication, lacked key elements of

Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by thei ...

technology, such as the use of iron and steel and functional wheels. The use of steel swords was perhaps the greatest technological advantage held by the Spanish, although the deployment of cavalry helped them to rout indigenous armies on occasion.

[Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p. 15.] The Spanish were sufficiently impressed by the quilted cotton armour of their Maya enemies that they adopted it in preference to their own steel armour.

The conquistadors applied a more effective military organisation and strategic awareness than their opponents, allowing them to deploy troops and supplies in a way that increased the Spanish advantage.

In Guatemala the Spanish routinely fielded indigenous allies; at first these were

Nahuas

The Nahuas () are a group of the indigenous people of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. They comprise the largest indigenous group in Mexico and second largest in El Salvador. The Mexica (Aztecs) were of Nahua ethnicity, a ...

brought from the recently conquered Mexico, later they also included

Mayas

The Maya peoples () are an ethnolinguistic group of Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. The ancient Maya civilization was formed by members of this group, and today's Maya are generally descended from people ...

. It is estimated that for every Spaniard on the field of battle, there were at least 10 native auxiliaries. Sometimes there were as many as 30 indigenous warriors for every Spaniard, and it was the participation of these Mesoamerican allies that was particularly decisive.

[Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p. 16.] In at least one case, ''

encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

'' rights were granted to one of the

Tlaxcalan

Tlaxcala (; , ; from nah, Tlaxcallān ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tlaxcala ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tlaxcala), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 60 municipaliti ...

leaders who came as allies, and land grants and exemption from being given in ''encomienda'' were given to the Mexican allies as rewards for their participation in the conquest. In practice, such privileges were easily removed or sidestepped by the Spanish and the indigenous conquistadors were treated in a similar manner to the conquered natives.

The Spanish engaged in a strategy of concentrating native populations in newly founded colonial towns, or ''

reducciones

Reductions ( es, reducciones, also called ; , pl. ) were settlements created by Spanish rulers and Roman Catholic missionaries in Spanish America and the Spanish East Indies (the Philippines). In Portuguese-speaking Latin America, such red ...

'' (also known as ''congregaciones''). Native resistance to the new nucleated settlements took the form of the flight of the indigenous inhabitants into inaccessible regions such as mountains and forests.

Impact of Old World diseases

Epidemics accidentally introduced by the Spanish included

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

,

measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

and

influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

. These diseases, together with

typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

and

yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

, had a major impact on

Maya

Maya may refer to:

Civilizations

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Maya language, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (Ethiopia), a popul ...

populations. The

Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by thei ...

diseases brought with the Spanish and against which the indigenous

New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

peoples had no resistance were a deciding factor in the conquest; the diseases crippled armies and decimated populations before battles were even fought. Their introduction was catastrophic in the Americas; it is estimated that 90% of the indigenous population had been eliminated by disease within the first century of European contact.

In 1519 and 1520, before the arrival of the Spanish in the region, a number of epidemics swept through southern Guatemala. At the same time as the Spanish were occupied with the overthrow of the

Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire or the Triple Alliance ( nci, Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān, �jéːʃkaːn̥ t͡ɬaʔtoːˈlóːjaːn̥ was an alliance of three Nahua city-states: , , and . These three city-states ruled that area in and around the Valley of Mexi ...

, a devastating plague struck the

Kaqchikel capital of

Iximche

Iximcheʼ () (or Iximché using Spanish orthography) is a Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican archaeological site in the western highlands of Guatemala. Iximche was the capital of the Late Postclassic Kaqchikel Maya kingdom from 1470 until its abandonm ...

, and the city of

Qʼumarkaj

Qʼumarkaj ( Kʼicheʼ: ) (sometimes rendered as Gumarkaaj, Gumarcaj, Cumarcaj or Kumarcaaj) is an archaeological site in the southwest of the El Quiché department of Guatemala.Kelly 1996, p.200. Qʼumarkaj is also known as Utatlán, the Nahuatl ...

, capital of the

Kʼicheʼ, may also have suffered from the same epidemic. It is likely that the same combination of smallpox and a pulmonary plague swept across the entire

Guatemalan Highlands

The Guatemalan Highlands is an upland region in southern Guatemala, lying between the Sierra Madre de Chiapas to the south and the Petén lowlands to the north.

Description

The highlands are made up of a series of high valleys enclosed by mount ...

. Modern knowledge of the impact of these diseases on populations with no prior exposure suggests that 33–50% of the population of the highlands perished. Population levels in the Guatemalan Highlands did not recover to their pre-conquest levels until the middle of the 20th century.

[Lovell 2005, p. 71.] In 1666 pestilence or

murine typhus swept through what is now the department of

Huehuetenango

Huehuetenango () is a city and municipality in the highlands of western Guatemala. It is also the capital of the department of Huehuetenango. The city is situated from Guatemala City, and is the last departmental capital on the Pan-American High ...

. Smallpox was reported in

San Pedro Saloma, in 1795.

[Hinz 2008, 2010, p. 37.] At the time of the fall of

Nojpetén

Nojpetén (also spelled Noh Petén, and also known as Tayasal) was the capital city of the Itza Maya kingdom of Petén Itzá. It is located on an island in Lake Petén Itzá in the modern department of Petén in northern Guatemala. The island ...

in 1697, there are estimated to have been 60,000 Mayas living around

Lake Petén Itzá

Lake Petén Itzá (''Lago Petén Itzá'', ) is a lake in the northern Petén Department in Guatemala. It is the third largest lake in Guatemala, after Lake Izabal and Lake Atitlán. It is located around . It has an area of , and is some long an ...

, including a large number of refugees from other areas. It is estimated that 88% of them died during the first ten years of colonial rule owing to a combination of disease and war.

Timeline of the conquest

Conquest of the highlands

The conquest of the highlands was made difficult by the many independent polities in the region, rather than one powerful enemy to be defeated as was the case in central Mexico. After the Aztec capital

Tenochtitlan

, ; es, Tenochtitlan also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, ; es, México-Tenochtitlan was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear. The date 13 March 1325 was ...

fell to the Spanish in 1521, the

Kaqchikel Maya of

Iximche

Iximcheʼ () (or Iximché using Spanish orthography) is a Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican archaeological site in the western highlands of Guatemala. Iximche was the capital of the Late Postclassic Kaqchikel Maya kingdom from 1470 until its abandonm ...

sent envoys to

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

to declare their allegiance to the new ruler of Mexico, and the

Kʼicheʼ Maya of

Qʼumarkaj

Qʼumarkaj ( Kʼicheʼ: ) (sometimes rendered as Gumarkaaj, Gumarcaj, Cumarcaj or Kumarcaaj) is an archaeological site in the southwest of the El Quiché department of Guatemala.Kelly 1996, p.200. Qʼumarkaj is also known as Utatlán, the Nahuatl ...

may also have sent a delegation.

[Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 763.] In 1522 Cortés sent Mexican allies to scout the

Soconusco

Soconusco is a region in the southwest corner of the state of Chiapas in Mexico along its border with Guatemala. It is a narrow strip of land wedged between the Sierra Madre de Chiapas mountains and the Pacific Ocean. It is the southernmost par ...

region of lowland

Chiapas

Chiapas (; Tzotzil and Tzeltal: ''Chyapas'' ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Chiapas ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Chiapas), is one of the states that make up the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It comprises 124 municipalities ...

, where they met new delegations from Iximche and Qʼumarkaj at

Tuxpán; both of the powerful highland Maya kingdoms declared their loyalty to the

king of Spain

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

.

But Cortés' allies in Soconusco soon informed him that the Kʼicheʼ and the Kaqchikel were not loyal, and were instead harassing Spain's allies in the region. Cortés decided to despatch

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration of the coasts of the Yucat ...

with 180 cavalry, 300 infantry, crossbows, muskets, 4 cannons, large amounts of ammunition and gunpowder, and thousands of allied Mexican warriors from

Tlaxcala

Tlaxcala (; , ; from nah, Tlaxcallān ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tlaxcala ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tlaxcala), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. It is ...

,

Cholula and other cities in central Mexico; they arrived in Soconusco in 1523.

Pedro de Alvarado was infamous for the

massacre of Aztec nobles in Tenochtitlan and, according to

Bartolomé de las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, OP ( ; ; 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman then became a Dominican friar ...

, he committed further atrocities in the conquest of the Maya kingdoms in Guatemala. Some groups remained loyal to the Spanish once they had submitted to the conquest, such as the

Tzʼutujil and the

Kʼicheʼ of

Quetzaltenango

Quetzaltenango (, also known by its Maya name Xelajú or Xela ) is both the seat of the namesake Department and municipality, in Guatemala.

The city is located in a mountain valley at an elevation of above sea level at its lowest part. It m ...

, and provided them with warriors to assist further conquest. Other groups soon rebelled however, and by 1526 numerous rebellions had engulfed the highlands.

Subjugation of the Kʼicheʼ

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration of the coasts of the Yucat ...

and his army advanced along the

Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

coast unopposed until they reached the

Samalá River

The Samalá is a river in southwestern Guatemala. Its sources are in the Sierra Madre, Valle De Écija range, in the departments of Quetzaltenango and Totonicapán. From there it flows down, past the towns San Carlos Sija in the Valle De É ...

in western Guatemala. This region formed a part of the

Kʼicheʼ kingdom, and a Kʼicheʼ army tried unsuccessfully to prevent the Spanish from crossing the river. Once across, the conquistadors ransacked nearby settlements in an effort to terrorise the Kʼicheʼ.

[Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 764.] On 8 February 1524 Alvarado's army fought a battle at Xetulul, called Zapotitlán by his Mexican allies (modern

). Although suffering many injuries inflicted by defending Kʼicheʼ archers, the Spanish and their allies stormed the town and set up camp in the marketplace. Alvarado then turned to head upriver into the

Sierra Madre mountains towards the Kʼicheʼ heartlands, crossing the pass into the fertile valley of

Quetzaltenango

Quetzaltenango (, also known by its Maya name Xelajú or Xela ) is both the seat of the namesake Department and municipality, in Guatemala.

The city is located in a mountain valley at an elevation of above sea level at its lowest part. It m ...

. On 12 February 1524 Alvarado's Mexican allies were ambushed in the pass and driven back by Kʼicheʼ warriors but the Spanish cavalry charge that followed was a shock for the Kʼicheʼ, who had never before seen horses. The cavalry scattered the Kʼicheʼ and the army crossed to the city of

Xelaju

Quetzaltenango (, also known by its Maya name Xelajú or Xela ) is both the seat of the namesake Department and municipality, in Guatemala.

The city is located in a mountain valley at an elevation of above sea level at its lowest part. It m ...

(modern Quetzaltenango) only to find it deserted. Although the common view is that the Kʼicheʼ prince

Tecun Uman died in the later battle near

Olintepeque, the Spanish accounts are clear that at least one and possibly two of the lords of

Qʼumarkaj

Qʼumarkaj ( Kʼicheʼ: ) (sometimes rendered as Gumarkaaj, Gumarcaj, Cumarcaj or Kumarcaaj) is an archaeological site in the southwest of the El Quiché department of Guatemala.Kelly 1996, p.200. Qʼumarkaj is also known as Utatlán, the Nahuatl ...

died in the fierce battles upon the initial approach to Quetzaltenango. The death of Tecun Uman is said to have taken place in the battle of El Pinar,

[Restall and Asselbergs 2007, pp. 9, 30.] and local tradition has his death taking place on the Llanos de Urbina (Plains of Urbina), upon the approach to Quetzaltenango near the modern village of

Cantel. Pedro de Alvarado, in his third letter to

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

, describes the death of one of the four lords of Qʼumarkaj upon the approach to Quetzaltenango. The letter was dated 11 April 1524 and was written during his stay at Qʼumarkaj.

Almost a week later, on 18 February 1524,

[Gall 1967, p. 41.] a Kʼicheʼ army confronted the Spanish army in the Quetzaltenango valley and were comprehensively defeated; many Kʼicheʼ nobles were among the dead.

Such were the numbers of Kʼicheʼ dead that Olintepeque was given the name ''Xequiquel'', roughly meaning "bathed in blood". In the early 17th century, the grandson of the Kʼicheʼ king informed the

alcalde mayor

An ''alcalde mayor'' was a regional magistrate in Spain and its territories from, at least, the 14th century to the 19th century. These regional officials had judicial, administrative, military and legislative authority. Their judicial and ad ...

(the highest colonial official at the time) that the Kʼicheʼ army that had marched out of Qʼumarkaj to confront the invaders numbered 30,000 warriors, a claim that is considered credible by modern scholars. This battle exhausted the Kʼicheʼ militarily and they asked for peace and offered tribute, inviting Pedro de Alvarado into their capital Qʼumarkaj, which was known as Tecpan Utatlan to the Nahuatl-speaking allies of the Spanish. Alvarado was deeply suspicious of the Kʼicheʼ intentions but accepted the offer and marched to Qʼumarkaj with his army.

[Sharer & Traxler 2006, p. 765.]

The day after the battle of Olintepeque, the Spanish army arrived at

Tzakahá, which submitted peacefully. There the Spanish chaplains

Juan Godínez and

Juan Díaz conducted a Roman Catholic mass under a makeshift roof;

[de León Soto 2010, p. 24.] this site was chosen to build the first church in Guatemala,

[de León Soto 2010, p. 22.] which was dedicated to Concepción La Conquistadora. Tzakahá was renamed as San Luis Salcajá.

The first Easter mass held in Guatemala was celebrated in the new church, during which high-ranking natives were baptised.

In March 1524 Pedro de Alvarado entered Qʼumarkaj at the invitation of the remaining lords of the Kʼicheʼ after their catastrophic defeat, fearing that he was entering a trap.

[Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp. 764–765.] He encamped on the plain outside the city rather than accepting lodgings inside. Fearing the great number of Kʼicheʼ warriors gathered outside the city and that his cavalry would not be able to manoeuvre in the narrow streets of Qʼumarkaj, he invited the leading lords of the city, Oxib-Keh (the ''

ajpop'', or king) and Beleheb-Tzy (the ''

ajpop kʼamha'', or king elect) to visit him in his camp. As soon as they did so, he seized them and kept them as prisoners in his camp. The Kʼicheʼ warriors, seeing their lords taken prisoner, attacked the Spaniards' indigenous allies and managed to kill one of the Spanish soldiers.

[Recinos 1952, 1986, p. 75.] At this point Alvarado decided to have the captured Kʼicheʼ lords burnt to death, and then proceeded to burn the entire city. After the destruction of Qʼumarkaj and the execution of its rulers, Pedro de Alvarado sent messages to

Iximche

Iximcheʼ () (or Iximché using Spanish orthography) is a Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican archaeological site in the western highlands of Guatemala. Iximche was the capital of the Late Postclassic Kaqchikel Maya kingdom from 1470 until its abandonm ...

, capital of the

Kaqchikel, proposing an alliance against the remaining Kʼicheʼ resistance. Alvarado wrote that they sent 4,000 warriors to assist him, although the Kaqchikel recorded that they sent only 400.

San Marcos: Province of Tecusitlán and Lacandón

With the capitulation of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom, various non-Kʼicheʼ peoples under Kʼicheʼ dominion also submitted to the Spanish. This included the Mam inhabitants of the area now within the modern department of

San (. Quetzaltenango and San Marcos were placed under the command of Juan de León y Cardona, who began the reduction of indigenous populations and the foundation of Spanish towns. The towns of

San Marcos and

San Pedro Sacatepéquez were founded soon after the conquest of western Guatemala. In 1533 Pedro de Alvarado ordered de León y Cardona to explore and conquer the area around the

Tacaná,

Tajumulco, Lacandón and San Antonio volcanoes; in colonial times this area was referred to as the Province of Tecusitlán and Lacandón.

De León marched to a Maya city named ''Quezalli'' by his Nahuatl-speaking allies with a force of fifty Spaniards; his Mexican allies also referred to the city by the name Sacatepequez. De León renamed the city as San Pedro Sacatepéquez in honour of his friar, Pedro de Angulo.

[de León Soto 2010, p. 26.] The Spanish founded a village nearby at Candacuchex in April that year, renaming it as San Marcos.

Kaqchikel alliance

On 14 April 1524, soon after the defeat of the

Kʼicheʼ, the Spanish were invited into

Iximche

Iximcheʼ () (or Iximché using Spanish orthography) is a Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican archaeological site in the western highlands of Guatemala. Iximche was the capital of the Late Postclassic Kaqchikel Maya kingdom from 1470 until its abandonm ...

and were well received by the lords Belehe Qat and Cahi Imox.

[Recinos places all these dates two days earlier (e.g. the Spanish arrival at Iximche on 12 April rather than 14 April) based on vague dating in Spanish primary records. Schele and Fahsen calculated all dates on the more securely dated Kaqchikel annals, where equivalent dates are often given in both the Kaqchikel and Spanish calendars. The Schele and Fahsen dates are used in this section. Schele & Mathews 1999, p. 386. n. 15.] The

Kaqchikel kings provided native soldiers to assist the conquistadors against continuing Kʼicheʼ resistance and to help with the defeat of the neighbouring

Tzʼutuhil kingdom.

[Schele and Mathews 1999, p. 297.] The Spanish only stayed briefly in Iximche before continuing through

Atitlán,

Escuintla

Escuintla () is an industrial city in Guatemala, its land extension is 4384 km², and it is nationally known for its sugar agribusiness. Its capital is a minicipality with the same name. Citizens celebrate from December 6 to 9 with a small fair ...

and

Cuscatlán. The Spanish returned to the Kaqchikel capital on 23 July 1524 and on 27 July (''1 Qʼat'' in the Kaqchikel calendar) Pedro de Alvarado declared Iximche as the first capital of Guatemala, Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala ("St. James of the Knights of Guatemala").

[Schele & Mathews 1999, p. 297. Recinos 1998, p. 101. Guillemín 1965, p. 10.] Iximche was called Guatemala by the Spanish, from the

Nahuatl

Nahuatl (; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have small ...

''Quauhtemallan'' meaning "forested land". Since the Spanish conquistadors founded their first capital at Iximche, they took the name of the city used by their Nahuatl-speaking Mexican allies and applied it to the new Spanish city and, by extension, to the

kingdom. From this comes the modern name of the country. When Pedro de Alvarado moved his army to Iximche, he left the defeated Kʼicheʼ kingdom under the command of Juan de León y Cardona.

[de León Soto 2010, p. 29.] Although de León y Cardona was given command of the western reaches of the new colony, he continued to take an active role in the continuing conquest, including the later assault on the

Poqomam capital.

Conquest of the Tzʼutujil

The

Kaqchikel appear to have entered into an alliance with the Spanish to defeat their enemies, the

Tzʼutujil, whose capital was Tecpan Atitlan.

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration of the coasts of the Yucat ...

sent two Kaqchikel messengers to Tecpan Atitlan at the request of the Kaqchikel lords, both of whom were killed by the Tzʼutujil. When news of the killing of the messengers reached the Spanish at

Iximche

Iximcheʼ () (or Iximché using Spanish orthography) is a Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican archaeological site in the western highlands of Guatemala. Iximche was the capital of the Late Postclassic Kaqchikel Maya kingdom from 1470 until its abandonm ...

, the conquistadors marched against the Tzʼutujil with their Kaqchikel allies.

Pedro de Alvarado left Iximche just 5 days after he had arrived there, with 60 cavalry, 150 Spanish infantry and an unspecified number of Kaqchikel warriors. The Spanish and their allies arrived at the lakeshore after a day's hard march, without encountering any opposition. Seeing the lack of resistance, Alvarado rode ahead with 30 cavalry along the lakeshore. Opposite a populated island the Spanish at last encountered hostile Tzʼutujil warriors and charged among them, scattering and pursuing them to a narrow causeway across which the surviving Tzʼutujil fled.

[Recinos 1952, 1986, p. 82.] The causeway was too narrow for the horses, therefore the conquistadors dismounted and crossed to the island before the inhabitants could break the bridges. The rest of Alvarado's army soon reinforced his party and they successfully stormed the island. The surviving Tzʼutujil fled into the lake and swam to safety on another island. The Spanish could not pursue the survivors further because 300 canoes sent by the Kaqchikels had not yet arrived. This battle took place on 18 April.

[Recinos 1952, 1986, p. 83.]

The following day the Spanish entered Tecpan Atitlan but found it deserted. Pedro de Alvarado camped in the centre of the city and sent out scouts to find the enemy. They managed to catch some locals and used them to send messages to the Tzʼutujil lords, ordering them to submit to the king of Spain. The Tzʼutujil leaders responded by surrendering to Pedro de Alvarado and swearing loyalty to Spain, at which point Alvarado considered them pacified and returned to Iximche.

Three days after Pedro de Alvarado returned to Iximche, the lords of the Tzʼutujil arrived there to pledge their loyalty and offer tribute to the conquistadors. A short time afterwards a number of lords arrived from the Pacific lowlands to swear allegiance to the king of Spain, although Alvarado did not name them in his letters; they confirmed Kaqchikel reports that further out on the Pacific plain was the kingdom called Izcuintepeque in

Nahuatl

Nahuatl (; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have small ...

, or Panatacat in

Kaqchikel, whose inhabitants were warlike and hostile towards their neighbours.

[Recinos 1952, 1986, p. 84.]

Kaqchikel rebellion

Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; c. 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador and governor of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the conquest of Cuba, in Juan de Grijalva's exploration of the coasts of the Yucat ...

rapidly began to demand gold in tribute from the

Kaqchikels, souring the friendship between the two peoples.

[Schele & Mathews 1999, p. 298.] He demanded that their kings deliver 1000 gold leaves, each worth 15

peso

The peso is the monetary unit of several countries in the Americas, and the Philippines. Originating in the Spanish Empire, the word translates to "weight". In most countries the peso uses the same sign, "$", as many currencies named " doll ...

s.

[Guillemin 1967 p. 25.][A ''peso'' was a Spanish coin. One peso was worth eight ''reales'' (the source of the term "pieces of eight") or two ''tostones''. During the conquest, a ''peso'' contained of gold. Lovell 2005, p. 223. Recinos 1952, 1986, p. 52. n. 25.]

A Kaqchikel priest foretold that the Kaqchikel gods would destroy the Spanish, causing the Kaqchikel people to abandon their city and flee to the forests and hills on 28 August 1524 (''7 Ahmak'' in the Kaqchikel calendar). Ten days later the Spanish declared war on the Kaqchikel.

Two years later, on 9 February 1526, a group of sixteen Spanish deserters burnt the palace of the ''

Ahpo Xahil'', sacked the temples and kidnapped a priest, acts that the Kaqchikel blamed on Pedro de Alvarado.

[Recinos 1998, p. 19. gives ''sixty'' deserters.] Conquistador

Bernal Díaz del Castillo

Bernal Díaz del Castillo ( 1492 – 3 February 1584) was a Spanish conquistador, who participated as a soldier in the conquest of the Aztec Empire under Hernán Cortés and late in his life wrote an account of the events. As an experience ...

recounted how in 1526 he returned to Iximche and spent the night in the "old city of Guatemala" together with

Luis Marín and other members of

Hernán Cortés's expedition to

Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

. He reported that the houses of the city were still in excellent condition; his account was the last description of the city while it was still inhabitable.

[Schele & Mathews 1999, p. 298. Recinos 1998, p. 19.]

The Spanish founded a new town at nearby

; ''Tecpán'' is

Nahuatl

Nahuatl (; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have small ...

for "palace", thus the name of the new town translated as "the palace among the trees".

The Spanish abandoned Tecpán in 1527, because of the continuous Kaqchikel attacks, and moved to the Almolonga Valley to the east, refounding their capital on the site of today's

San Miguel Escobar district of

Ciudad Vieja

Ciudad Vieja () is a town and municipality in the Guatemalan department of Sacatepéquez. According to the 2018 census, the town has a population of 32,802 , near

Antigua Guatemala

Antigua Guatemala (), commonly known as Antigua or La Antigua, is a city in the central highlands of Guatemala. The city was the capital of the Captaincy General of Guatemala from 1543 through 1773, with much of its Baroque-influenced architec ...

. The

Nahua

The Nahuas () are a group of the indigenous people of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. They comprise the largest indigenous group in Mexico and second largest in El Salvador. The Mexica (Aztecs) were of Nahua ethnicity, a ...

and

Oaxaca

Oaxaca ( , also , , from nci, Huāxyacac ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Oaxaca), is one of the 32 states that compose the Federative Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 570 municipaliti ...

n allies of the Spanish settled in what is now central Ciudad Vieja, then known as Almolonga (not to be confused with

Almolonga

The Almolonga volcano, also called "Cerro Quemado" (Burned Mountain) or "La Muela" (The Molar) due to its distinct shape, is an andesitic stratovolcano in the south-western department of Quetzaltenango in Guatemala. The volcano is located near t ...

near

Quetzaltenango

Quetzaltenango (, also known by its Maya name Xelajú or Xela ) is both the seat of the namesake Department and municipality, in Guatemala.

The city is located in a mountain valley at an elevation of above sea level at its lowest part. It m ...

);

Zapotec and

Mixtec allies also settled San Gaspar Vivar about northeast of Almolonga, which they founded in 1530.

The Kaqchikel kept up resistance against the Spanish for a number of years, but on 9 May 1530, exhausted by the warfare that had seen the deaths of their best warriors and the enforced abandonment of their crops, the two kings of the most important clans returned from the wilds.

A day later they were joined by many nobles and their families and many more people; they then surrendered at the new Spanish capital at Ciudad Vieja.

The former inhabitants of

Iximche

Iximcheʼ () (or Iximché using Spanish orthography) is a Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican archaeological site in the western highlands of Guatemala. Iximche was the capital of the Late Postclassic Kaqchikel Maya kingdom from 1470 until its abandonm ...

were dispersed; some were moved to

Tecpán, the rest to

Sololá __NOTOC__

Sololá is a city in Guatemala. It is the capital of the department of Sololá and the administrative seat of Sololá municipality. It is located close to Lake Atitlan.

The name is a Hispanicized form of its pre-Columbian name, one sp ...

and other towns around

Lake Atitlán

Lake Atitlán ( es, links=no, Lago de Atitlán, ) is a lake in the Guatemalan Highlands of the Sierra Madre mountain range. The lake is located in the Sololá Department of southwestern Guatemala. It is known as the deepest lake in Central Ameri ...

.

[Schele & Mathews 1999, p. 299.]

Siege of Zaculeu

Although a state of hostilities existed between the

Mam

Mam or MAM may refer to:

Places

* An Mám or Maum, a settlement in Ireland

* General Servando Canales International Airport in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico (IATA Code: MAM)

* Isle of Mam, a phantom island

* Mam Tor, a hill near Castleton in th ...

and the

Kʼicheʼ of

Qʼumarkaj