Ukrainian ( uk, украї́нська мо́ва, translit=ukrainska mova, label=native name, ) is an

East Slavic language

The East Slavic languages constitute one of three regional subgroups of the Slavic languages, distinct from the West and South Slavic languages. East Slavic languages are currently spoken natively throughout Eastern Europe, and eastwards to Sibe ...

of the

Indo-European language family. It is the

native language of about 40 million people and the

official state language of

Ukraine in

Eastern Europe. Written Ukrainian uses the

Ukrainian alphabet, a variant of the

Cyrillic script. The

standard Standard may refer to:

Symbols

* Colours, standards and guidons, kinds of military signs

* Standard (emblem), a type of a large symbol or emblem used for identification

Norms, conventions or requirements

* Standard (metrology), an object ...

Ukrainian language is regulated by the

National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (NANU; particularly by its

Institute for the Ukrainian Language), the Ukrainian language-information fund, and

Potebnia Institute of Linguistics

Potebnia Institute of Linguistics is a research institute in Ukraine, which is part of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine department of literature, language, and art studies. It is focused on linguistic research and studies of linguistic ...

. Comparisons are often drawn to

Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

* Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and p ...

, a prominent

Slavic language, but there is more

mutual intelligibility with

Belarusian

Belarusian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to Belarus

* Belarusians, people from Belarus, or of Belarusian descent

* A citizen of Belarus, see Demographics of Belarus

* Belarusian language

* Belarusian culture

* Belarusian cuisine

* Byelor ...

,

[Alexander M. Schenker. 1993. "Proto-Slavonic," ''The Slavonic Languages''. (Routledge). pp. 60–121. p. 60: " hedistinction between dialect and language being blurred, there can be no unanimity on this issue in all instances..."]

C.F. Voegelin and F.M. Voegelin. 1977. ''Classification and Index of the World's Languages'' (Elsevier). p. 311, "In terms of immediate mutual intelligibility, the East Slavic zone is a single language."

Bernard Comrie. 1981. ''The Languages of the Soviet Union'' (Cambridge). pp. 145–146: "The three East Slavonic languages are very close to one another, with very high rates of mutual intelligibility...The separation of Russian, Ukrainian, and Belorussian as distinct languages is relatively recent...Many Ukrainians in fact speak a mixture of Ukrainian and Russian, finding it difficult to keep the two languages apart..."

The Swedish linguist Alfred Jensen wrote in 1916 that the difference between the Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

* Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and p ...

and Ukrainian languages was significant and that it could be compared to the difference between Swedish and Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish ance ...

. Jensen, Alfred. ''Slaverna och världskriget. Reseminnen och intryck från Karpaterna till Balkan 1915–16.''. Albert Bonniers förlag, Stockholm, 1916, p. 145. Ukrainian's closest relative.

Historical linguists trace the origin of the Ukrainian language to

Old East Slavic

Old East Slavic (traditionally also Old Russian; be, старажытнаруская мова; russian: древнерусский язык; uk, давньоруська мова) was a language used during the 9th–15th centuries by East ...

, a language of the early medieval state of

Kyivan Rus'. Modern linguistics denies the existence of a stage of a common East Slavic language, therefore, referring the Ukrainian language to "East Slavonic" is also more of a tribute to the academic tradition. After the fall of the Kyivan Rus' as well as the

Kingdom of Ruthenia

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

, the language developed into a form called the

Ruthenian language, and enjoyed as such the status of one of the official languages of the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania for several centuries. Along with Ruthenian, in the territory of modern Ukraine, the Kyiv version (''Kyiv Izvod'') of

Church Slavonic

Church Slavonic (, , literally "Church-Slavonic language"), also known as Church Slavic, New Church Slavonic or New Church Slavic, is the conservative Slavic liturgical language used by the Eastern Orthodox Church in Belarus, Bosnia and Herzeg ...

was also used in

liturgical services.

The Ukrainian language has been in common use since the late 17th century, associated with the establishment of the

Cossack Hetmanate

The Cossack Hetmanate ( uk, Гетьманщина, Hetmanshchyna; or ''Cossack state''), officially the Zaporizhian Host or Army of Zaporizhia ( uk, Військо Запорозьке, Viisko Zaporozke, links=no; la, Exercitus Zaporoviensis) ...

. From 1804 until the 1917–1921

Ukrainian War of Independence

The Ukrainian War of Independence was a series of conflicts involving many adversaries that lasted from 1917 to 1921 and resulted in the establishment and development of a Ukrainian republic, most of which was later absorbed into the Soviet U ...

, the Ukrainian language was banned from schools in the

Russian Empire, of which the

biggest part of Ukraine (Central, Eastern and Southern) was a part at the time.

[Eternal Russia: Yeltsin, Gorbachev, and the Mirage of Democracy](_blank)

by Jonathan Steele, Harvard University Press, 1988, (p. 217) Through folk songs,

itinerant musicians, and prominent authors, the language has always maintained a sufficient base in

Western Ukraine, where the language was never banned.

[Purism and Language: A Study in Modem Ukrainian and Belorussian Nationalism](_blank)

by Paul Wexler, Indiana University Press, (page 309)[Contested Tongues: Language Politics and Cultural Correction in Ukraine](_blank)

by Laada Bilaniuk, Cornell Univ. Press

The Cornell University Press is the university press of Cornell University; currently housed in Sage House, the former residence of Henry William Sage. It was first established in 1869, making it the first university publishing enterprise in t ...

, 2006, (page 78)

Linguistic development

Theories

Specifically Ukrainian developments that led to a gradual change of the Old East Slavic vowel system into the system found in modern Ukrainian began approximately in the 12th/13th century (that is, still at the time of the Kyivan Rus') with a lengthening and raising of the Old East Slavic mid vowels ''e'' and ''o'' when followed by a consonant and a

weak yer vowel that would eventually disappear completely, for example Old East Slavic котъ /kɔtə/ > Ukrainian кіт /kit/ 'cat' (via transitional stages such as /koˑtə̆/, /kuˑt(ə̆)/, /kyˑt/ or similar) or Old East Slavic печь /pʲɛtʃʲə/ > Ukrainian піч /pitʃ/ 'oven' (via transitional stages such as /pʲeˑtʃʲə̆/, /pʲiˑtʃʲ/ or similar). This raising and other phonological developments of the time, such as the merger of the Old East Slavic vowel phonemes и /i/ and ы /ɨ/ into the specifically Ukrainian phoneme /ɪ ~ e/, spelled with и (in the 13th/14th centuries), and the fricativisation of the Old East Slavic consonant г /g/, probably first to /ɣ/ (in the 13th century), with the result /ɦ/ in Modern Ukrainian, never happened in Russian, and only the fricativisation of Old East Slavic г /g/ occurred in Belarusian, where the result is /ɣ/.

The first theory of the origin of the Ukrainian language was suggested in

Imperial Russia in the middle of the 18th century by

Mikhail Lomonosov. This theory posits the existence of a common language spoken by all

East Slavic people

The East Slavs are the most populous subgroup of the Slavs. They speak the East Slavic languages, and formed the majority of the population of the medieval state Kievan Rus', which they claim as their cultural ancestor.John Channon & Robert Hud ...

in the time of the Rus'. According to Lomonosov, the differences that subsequently developed between

Great Russian

Russian (russian: русский язык, russkij jazyk, link=no, ) is an East Slavic language mainly spoken in Russia. It is the native language of the Russians, and belongs to the Indo-European language family. It is one of four living Eas ...

and Ukrainian (which he referred to as

Little Russian) could be explained by the influence of the Polish and Slovak languages on Ukrainian and the influence of

Uralic languages on Russian from the 13th to the 17th centuries.

Another point of view was developed during the 19th and 20th centuries by other

linguists of Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union. Like Lomonosov, they assumed the existence of a common language spoken by East Slavs in the past. But unlike Lomonosov's hypothesis, this theory does not view "

Polonization" or any other external influence as the main driving force that led to the formation of three different languages (Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian) from the common

Old East Slavic

Old East Slavic (traditionally also Old Russian; be, старажытнаруская мова; russian: древнерусский язык; uk, давньоруська мова) was a language used during the 9th–15th centuries by East ...

language. The supporters of this theory disagree, however, about the time when the different languages were formed.

Soviet scholars set the divergence between Ukrainian and Russian only at later time periods (14th through 16th centuries). According to this view, Old East Slavic diverged into Belarusian and Ukrainian to the west (collectively, the

Ruthenian language of the 15th to 18th centuries), and

Old East Slavic

Old East Slavic (traditionally also Old Russian; be, старажытнаруская мова; russian: древнерусский язык; uk, давньоруська мова) was a language used during the 9th–15th centuries by East ...

to the north-east, after the political boundaries of the Kyivan Rus' were redrawn in the 14th century.

Some researchers, while admitting the differences between the dialects spoken by East Slavic tribes in the 10th and 11th centuries, still consider them as "regional manifestations of a common language".

In contrast,

Ahatanhel Krymsky

Ahatanhel Yukhymovych Krymsky ( uk, Агатангел Юхимович Кримський, russian: Агафангел Ефимович Крымский; – 25 January 1942) was a Ukrainian Orientalist, linguist, polyglot (knowing up to 35 lan ...

and

Aleksey Shakhmatov

Alexei Alexandrovich Shakhmatov (russian: link=no, Алексе́й Алекса́ндрович Ша́хматов, – 16 August 1920) was a Russian Imperial philologist and historian credited with laying foundations for the science of t ...

assumed the existence of the common spoken language of Eastern Slavs only in prehistoric times. According to their point of view, the diversification of the Old East Slavic language took place in the 8th or early 9th century.

Russian linguist

Andrey Zaliznyak

Andrey Anatolyevich Zaliznyak ( rus, Андре́й Анато́льевич Зализня́к, p=zəlʲɪˈzʲnʲak; 29 April 1935 – 24 December 2017) was a Soviet and Russian linguist, an expert in historical linguistics, accentology, dialec ...

stated that the

Old Novgorod dialect

Old Novgorod dialect (russian: древненовгородский диалект, translit=drevnenovgorodskij dialekt; also translated as Old Novgorodian or Ancient Novgorod dialect) is a term introduced by Andrey Zaliznyak to describe the dial ...

differed significantly from that of other dialects of Kyivan Rus' during the 11th–12th century, but

started becoming more similar to them around 13th–15th centuries. The modern Russian language hence developed from the fusion of this Novgorod dialect and the common dialect spoken by the other Kyivan Rus', whereas the modern Ukrainian and Belarusian languages developed from the dialects which did not differ from each other in a significant way.

Some Ukrainian features were recognizable in the southern dialects of Old East Slavic as far back as the language can be documented.

Ukrainian linguist

Stepan Smal-Stotsky denies the existence of a common Old East Slavic language at any time in the past. Similar points of view were shared by

Yevhen Tymchenko,

Vsevolod Hantsov,

Olena Kurylo,

Ivan Ohienko and others. According to this theory, the dialects of East Slavic tribes evolved gradually from the common Proto-Slavic language without any intermediate stages during the 6th through 9th centuries. The Ukrainian language was formed by convergence of tribal dialects, mostly due to an intensive migration of the population within the territory of today's Ukraine in later historical periods. This point of view was also supported by

George Shevelov

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Łomża, Łomża Governorate, Russian Empire (now Poland)

, death_date =

, death_place =

, resting_place =

, resting_place_coordinates =

, home_town =

, other_names ...

's phonological studies.

Origins and developments during medieval times

As a result of close Slavic contacts with the remnants of the

Scythian and

Sarmatian

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cent ...

population north of the

Black Sea, lasting into the early

Middle Ages, the appearance of the voiced fricative γ/г (romanized "h"), in modern Ukrainian and some southern Russian dialects is explained by the assumption that it initially emerged in

Scythian and related eastern Iranian dialects, from earlier common

Proto-Indo-European ''*g'' and ''*gʰ''.

During the 13th century, when German settlers were invited to Ukraine by the princes of the Kingdom of Ruthenia, German words began to appear in the language spoken in Ukraine. Their influence would continue under

Poland not only through German colonists but also through the

Yiddish-speaking Jews. Often such words involve trade or handicrafts. Examples of words of German or Yiddish origin spoken in Ukraine include ''dakh'' (roof), ''rura'' (pipe), ''rynok'' (market), ''kushnir'' (furrier), and ''majster'' (master or craftsman).

[History of the Ukrainian Language. R. Smal-Stocky. In ''Ukraine: A Concise Encyclopedia.''(1963). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 490–500]

Developments under Poland and Lithuania

In the 13th century, eastern parts of Rus (including Moscow) came under

Tatar rule until their unification under the Tsardom of

Muscovy, whereas the south-western areas (including

Kyiv) were incorporated into the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania. For the following four centuries, the languages of the two regions evolved in relative isolation from each other. Direct written evidence of the existence of the Ukrainian language dates to the late 16th century. By the 16th century, a peculiar official language formed: a mixture of the liturgical standardised language of

Old Church Slavonic,

Ruthenian and

Polish. The influence of the latter gradually increased relative to the former two, as the nobility and rural large-landowning class, known as the

szlachta, was largely Polish-speaking. Documents soon took on many Polish characteristics superimposed on Ruthenian phonetics.

[ ]Nikolay Kostomarov

Mykola Ivanovych Kostomarov or Nikolai Ivanovich Kostomarov (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Костома́ров, ; uk, Микола Іванович Костомаров, ; May 16, 1817, vil. Yurasovka, Voronezh Governorate, R ...

, ''Russian History in Biographies of its main figures'', Chapter

Knyaz Kostantin Konstantinovich Ostrozhsky

' (Konstanty Wasyl Ostrogski

Konstanty Wasyl Ostrogski (2 February 1526 – 13 or 23 February 1608, also known as ''Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozkyi'', uk, Костянтин-Василь Острозький, be, Канстантын Васіль Астрожскi, lt, Konst ...

)

Polish rule and education also involved significant exposure to the

Latin language. Much of the influence of Poland on the development of the Ukrainian language has been attributed to this period and is reflected in multiple words and constructions used in everyday Ukrainian speech that were taken from Polish or Latin. Examples of Polish words adopted from this period include ''zavzhdy'' (always; taken from old Polish word ''zawżdy'') and ''obitsiaty'' (to promise; taken from Polish ''obiecać'') and from Latin (via Polish) ''raptom'' (suddenly) and ''meta'' (aim or goal).

Significant contact with

Tatars and

Turks resulted in many

Turkic words, particularly those involving military matters and steppe industry, being adopted into the Ukrainian language. Examples include ''torba'' (bag) and ''tyutyun'' (tobacco).

Due to heavy borrowings from Polish, German, Czech and Latin, early modern vernacular Ukrainian (''prosta mova'', "

simple speech Simple speech ( uk, проста мова, prosta mova, pl, mowa prosta, po prostu, be, про́стая мова; па простаму, prostaya mova; "(to speak) in a simple way"), also translated as "simple language" or "simple talk", is an in ...

") had more lexical similarity with

West Slavic languages

The West Slavic languages are a subdivision of the Slavic language group. They include Polish, Czech, Slovak, Kashubian, Upper Sorbian and Lower Sorbian. The languages have traditionally been spoken across a mostly continuous region encompas ...

than with Russian or Church Slavonic. By the mid-17th century, the linguistic divergence between the Ukrainian and Russian languages had become so significant that there was a need for translators during negotiations for the

, between

Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynovii Mykhailovych Khmelnytskyi ( Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богданъ Хмелнiцкiи; modern ua, Богдан Зиновій Михайлович Хмельницький; 6 August 1657) was a Ukrainian military commander and ...

, head of the

Zaporozhian Host

Zaporozhian Host (or Zaporizhian Sich) is a term for a military force inhabiting or originating from Zaporizhzhia, the territory beyond the rapids of the Dnieper River in what is Central Ukraine today, from the 15th to the 18th centuries.

These ...

, and the Russian state.

Chronology

The accepted chronology of Ukrainian divides the language into Old, Middle, and Modern Ukrainian.

George Shevelov

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Łomża, Łomża Governorate, Russian Empire (now Poland)

, death_date =

, death_place =

, resting_place =

, resting_place_coordinates =

, home_town =

, other_names ...

explains that much of this is based on the character of contemporary written sources, ultimately reflecting socio-historical developments, and he further subdivides the MU period with Early and Late phases.

* Proto-Ukrainian (abbreviated PU, Ukrainian: , until the mid-11th century), with no extant written sources by speakers in Ukraine. Corresponding to aspects of

Old East Slavic

Old East Slavic (traditionally also Old Russian; be, старажытнаруская мова; russian: древнерусский язык; uk, давньоруська мова) was a language used during the 9th–15th centuries by East ...

.

* Old Ukrainian (OU, or , mid-11th to 14th c., conventional end date 1387), elements of phonology are deduced from written texts mainly in Church Slavic. Part of broader Old East Slavic.

*Middle Ukrainian ( or , 15th to 18th c.), historically called Ruthenian.

** Early Middle Ukrainian (EMU, , 15th to mid-16th c., 1387–1575), analysis focuses on distinguishing Ukrainian and Belarusian texts.

** Middle Ukrainian (MU, , mid-16th to early 18th c., 1575–1720), represented by several vernacular language varieties as well as a version of Church Slavic.

** Late Middle Ukrainian (LMU, , rest of the 18th c., 1720–1818), found in many mixed Ukrainian–Russian and Russian–Ukrainian texts.

* Modern Ukrainian (MoU, from the very end of the 18th c., or , from 1818), the vernacular recognized first in literature, and subsequently all other written genres.

Ukraine annually marks the Day of Ukrainian Writing and Language on November 9, the

Eastern Orthodox feast day

The calendar of saints is the traditional Christian method of organizing a liturgical year by associating each day with one or more saints and referring to the day as the feast day or feast of said saint. The word "feast" in this context does ...

of

Nestor the Chronicler

Saint Nestor the Chronicler ( orv, Несторъ Лѣтописецъ; 1056 – c. 1114, in Principality of Kiev, Kievan Rus') was the reputed author of ''Primary Chronicle'' (the earliest East Slavic letopis), ''Life of the Venerable Theod ...

.

History of the spoken language

Rus and Kingdom of Ruthenia

During the

Khazar period, the territory of Ukraine was settled by Iranian (post-

Scythian), Turkic (post-Hunnic, proto-Bulgarian), and Uralic (proto-Hungarian) tribes and Slavic tribes. Later, the

Varangian ruler

Oleg of Novgorod would seize Kyiv and establish the political entity of Kyivan Rus'.

The era of Kyivan Rus is the subject of some linguistic controversy, as the language of much of the literature was purely or heavily

Old Church Slavonic. Literary records from Kyivan Rus testify to substantial difference between

Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

* Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and p ...

and

Ruthenian form of the Ukrainian language as early as Kyivan Rus time.

Some theorists see an early Ukrainian stage in language development here, calling it Old

Ruthenian; others term this era

Old East Slavic

Old East Slavic (traditionally also Old Russian; be, старажытнаруская мова; russian: древнерусский язык; uk, давньоруська мова) was a language used during the 9th–15th centuries by East ...

. Russian theorists tend to amalgamate Rus to the modern nation of Russia, and call this linguistic era Old Russian. However, according to Russian linguist Andrey Zaliznyak, Novgorod people did not call themselves Rus until the 14th century, calling Rus only

Kyiv,

Pereiaslav

Pereiaslav ( uk, Перея́слав, translit=Pereiaslav, yi, פּרעיאַסלעוו, Periyoslov) is a historical city in the Boryspil Raion, Kyiv Oblast (province) of central Ukraine, located near the confluence of Alta and Trubizh rive ...

and

Chernihiv

Chernihiv ( uk, Черні́гів, , russian: Черни́гов, ; pl, Czernihów, ; la, Czernihovia), is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within t ...

principalities

(the Kyivan Rus state existed till 1240). At the same time as evidenced by the contemporary chronicles, the ruling princes of

Kingdom of Ruthenia

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

and Kyiv called themselves "People of Rus" –

Ruthenians, and

Galicia–Volhynia was called the Kingdom of Ruthenia.

Also according to Andrey Zaliznyak, the Novgorod dialect differed significantly from that of other dialects of Kyivan Rus during the 11th–12th century, but

started becoming more similar to them around 13th–15th centuries. The modern Russian language hence developed from the fusion of this Novgorod dialect and the common dialect spoken by the other Kyivan Rus, whereas the modern Ukrainian and Belarusian languages developed from the dialects which did not differ from each other in a significant way.

Under Lithuania/Poland, Muscovy/Russia and Austro-Hungary

After the fall of

Kingdom of Ruthenia

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

, Ukrainians mainly fell under the rule of Lithuania and then

Poland. Local autonomy of both rule and language was a marked feature of Lithuanian rule. In the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Old East Slavic became the language of the chancellery and gradually evolved into the Ruthenian language. Polish rule, which came later, was accompanied by a more assimilationist policy. By the 1569

Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin ( pl, Unia lubelska; lt, Liublino unija) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the pe ...

that formed the

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a significant part of Ukrainian territory was moved from Lithuanian rule to Polish administration, resulting in cultural

Polonization and visible attempts to

colonize

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

Ukraine by the Polish nobility.

Many Ukrainian nobles were forced to learn the Polish language and convert to Catholicism during that period in order to maintain their lofty aristocratic position. Lower classes were less affected because literacy was common only in the upper class and clergy. The latter were also under significant Polish pressure after the

Union with the Catholic Church. Most of the educational system was gradually Polonized. In Ruthenia, the language of administrative documents gradually shifted towards Polish.

The

Polish language has had heavy influences on Ukrainian (particularly in

Western Ukraine). The southwestern Ukrainian dialects are

transitional to Polish.

[Geoffrey Hull, Halyna Koscharsky.]

Contours and Consequences of the Lexical Divide in Ukrainian

. ''Australian Slavonic and East European Studies''. Vol. 20, no. 1-2. 2006. pp. 140–147. As the Ukrainian language developed further, some borrowings from

Tatar

The Tatars ()[Tatar]

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different and

Turkish occurred. Ukrainian culture and language flourished in the sixteenth and first half of the 17th century, when Ukraine was part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, albeit in spite of being part of the PLC, not as a result. Among many schools established in that time, the Kyiv-Mohyla Collegium (the predecessor of the modern

Kyiv-Mohyla Academy), founded by the

Moldavian

Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pa ...

Metropolitan

Metropolitan may refer to:

* Metropolitan area, a region consisting of a densely populated urban core and its less-populated surrounding territories

* Metropolitan borough, a form of local government district in England

* Metropolitan county, a typ ...

Peter Mogila

Metropolitan Petru Movilă ( ro, Petru Movilă, uk, Петро Симеонович Могила, translit=Petro Symeonovych Mohyla, russian: Пётр Симеонович Могила, translit=Pëtr Simeonovich Mogila, pl, Piotr Mohyła; ...

, was the most important. At that time languages were associated more with religions: Catholics spoke

Polish, and members of the Orthodox church spoke

Ruthenian.

After the

, Ukrainian high culture went into a long period of steady decline. In the aftermath, the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy was taken over by the

Russian Empire and closed down later in the 19th century. Most of the remaining Ukrainian schools also switched to Polish or Russian in the territories controlled by these respective countries, which was followed by a new wave of

Polonization and

Russification of the native nobility. Gradually the official language of Ukrainian provinces under Poland was changed to Polish, while the upper classes in the Russian part of Ukraine used Russian.

During the 19th century, a revival of Ukrainian self-identification manifested in the literary classes of both Russian-Empire

Dnieper Ukraine

The term Dnieper Ukraine

(: "over Dnieper land"), usually refers to territory on either side of the middle course of the Dnieper River. The Ukrainian name derives from ''nad‑'' (prefix: "above, over") + ''Dnipró'' ("Dnieper") + ''‑shchyna' ...

and Austrian

Galicia. The

Brotherhood of Sts Cyril and Methodius in Kyiv applied an old word for the Cossack motherland, ''Ukrajina'', as a self-appellation for the nation of Ukrainians, and ''Ukrajins'ka mova'' for the language. Many writers published works in the Romantic tradition of Europe demonstrating that Ukrainian was not merely a language of the village but suitable for literary pursuits.

However, in the Russian Empire expressions of Ukrainian culture and especially language were repeatedly persecuted for fear that a self-aware Ukrainian nation would threaten the unity of the empire. In 1804 Ukrainian as a subject and language of instruction was banned from schools.

[ In 1811 by the Order of the Russian government, the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy was closed. The academy had been open since 1632 and was the first university in Eastern Europe.

In 1847 the Brotherhood of Sts Cyril and Methodius was terminated. The same year ]Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko ( uk, Тарас Григорович Шевченко , pronounced without the middle name; – ), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (a kobzar is a bard in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukrainian poet, wr ...

was arrested, exiled for ten years, and banned for political reasons from writing and painting. In 1862 Pavlo Chubynsky was exiled for seven years to Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ; rus, Арха́нгельск, p=ɐrˈxanɡʲɪlʲsk), also known in English as Archangel and Archangelsk, is a city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina near i ...

. The Ukrainian magazine ''Osnova

The Ukrainian journal ''Osnova'' (meaning ''Basis'' in English) was published between 1861 and 1862 in Saint Petersburg. It contained articles devoted to life and customs of the Ukrainian people, including regular features about their wedding c ...

'' was discontinued. In 1863, the tsarist interior minister Pyotr Valuyev

Count Pyotr Aleksandrovich ValuevAlso transliterated Peter Alexandrovich Valuyev. ( rus, Граф Пётр Алекса́ндрович Валу́ев; September 22, 1815 – January 27, 1890) was a Russian statesman and writer.

Life

Valuev w ...

proclaimed in his decree that "there never has been, is not, and never can be a separate Little Russian language".

A following ban on Ukrainian books led to Alexander II's secret Ems Ukaz

The Ems Ukaz or Ems Ukase (russian: Эмский указ, Emskiy ukaz; uk, Емський указ, Ems’kyy ukaz), was a secret decree (''ukaz'') of Emperor Alexander II of Russia issued on May 18, 1876, banning the use of the Ukrainian lang ...

, which prohibited publication and importation of most Ukrainian-language books, public performances and lectures, and even banned the printing of Ukrainian texts accompanying musical scores. A period of leniency after 1905 was followed by another strict ban in 1914, which also affected Russian-occupied Galicia.

For much of the 19th century the Austrian authorities demonstrated some preference for Polish culture, but the Ukrainians were relatively free to partake in their own cultural pursuits in Halychyna and Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter Berge ...

, where Ukrainian was widely used in education and official documents. The suppression by Russia hampered the literary development of the Ukrainian language in Dnipro Ukraine, but there was a constant exchange with Halychyna, and many works were published under Austria and smuggled to the east.

By the time of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the collapse of Austro-Hungary in 1918, Ukrainians were ready to openly develop a body of national literature, institute a Ukrainian-language educational system, and form an independent state (the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 19 ...

, shortly joined by the West Ukrainian People's Republic). During this brief independent statehood the stature and use of Ukrainian greatly improved.

Speakers in the Russian Empire

In the Russian Empire Census of 1897 the following picture emerged, with Ukrainian being the second most spoken language of the Russian Empire. According to the Imperial census's terminology, the Russian language (''Русскій'') was subdivided into Ukrainian (Малорусскій, ' Little Russian'), what is known as Russian today (Великорусскій, '

In the Russian Empire Census of 1897 the following picture emerged, with Ukrainian being the second most spoken language of the Russian Empire. According to the Imperial census's terminology, the Russian language (''Русскій'') was subdivided into Ukrainian (Малорусскій, ' Little Russian'), what is known as Russian today (Великорусскій, 'Great Russian

Russian (russian: русский язык, russkij jazyk, link=no, ) is an East Slavic language mainly spoken in Russia. It is the native language of the Russians, and belongs to the Indo-European language family. It is one of four living Eas ...

'), and Belarusian (Бѣлорусскій, 'White Russian').

The following table shows the distribution of settlement by native language (''"по родному языку"'') in 1897 in Russian Empire governorates ('' guberniyas'') that had more than 100,000 Ukrainian speakers.

Although in the rural regions of the Ukrainian provinces, 80% of the inhabitants said that Ukrainian was their native language in the Census of 1897 (for which the results are given above), in the urban regions only 32.5% of the population claimed Ukrainian as their native language. For example, in Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

(then part of the Russian Empire), at the time the largest city in the territory of current Ukraine, only 5.6% of the population said Ukrainian was their native language.[''Soviet Nationality Policy, Urban Growth, and Identity Change in the Ukrainian SSR 1923–1934'']

by George O. Liber, Cambridge University Press, 1992, (page 12/13)

Until the 1920s the urban population in Ukraine grew faster than the number of Ukrainian speakers. This implies that there was a (relative) decline in the use of Ukrainian language. For example, in Kyiv, the number of people stating that Ukrainian was their native language declined from 30.3% in 1874 to 16.6% in 1917.[

]

Soviet era

During the seven-decade-long

During the seven-decade-long Soviet era

The history of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union (USSR) reflects a period of change for both Russia and the world. Though the terms "Soviet Russia" and "Soviet Union" often are synonymous in everyday speech (either acknowledging the dominance ...

, the Ukrainian language held the formal position of the principal local language in the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

.[The Ukraine]

''Life'', 26 October 1946 However, practice was often a different story:[ Ukrainian always had to compete with Russian, and the attitudes of the Soviet leadership towards Ukrainian varied from encouragement and tolerance to de facto banishment.

Officially, there was no ]state language

An official language is a language given supreme status in a particular country, state, or other jurisdiction. Typically the term "official language" does not refer to the language used by a people or country, but by its government (e.g. judiciary, ...

in the Soviet Union until the very end when it was proclaimed in 1990 that Russian language was the all-Union state language and that the constituent republics

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

had rights to declare additional state languages within their jurisdictions. Still it was implicitly understood in the hopes of minority nations that Ukrainian would be used in the Ukrainian SSR, Uzbek would be used in the Uzbek SSR, and so on. However, Russian was used in all parts of the Soviet Union and a special term, "a language of inter-ethnic communication", was coined to denote its status.

Soviet language policy in Ukraine may be divided into the following policy periods:

* Ukrainianization

Ukrainization (also spelled Ukrainisation), sometimes referred to as Ukrainianization (or Ukrainianisation) is a policy or practice of increasing the usage and facilitating the development of the Ukrainian language and promoting other elements of ...

and tolerance (1921–1932)

* Persecution and Russification (1933–1957)

* Khrushchev thaw (1958–1962)

* The Shelest period: limited progress (1963–1972)

* The Shcherbytsky

Volodymyr Vasylyovych Shcherbytsky, russian: Влади́мир Васи́льевич Щерби́цкий; ''Vladimir Vasilyevich Shcherbitsky'', (17 February 1918 — 16 February 1990) was a Ukrainian Soviet politician. He was First Secr ...

period: gradual suppression (1973–1989)

* Mikhail Gorbachev and perestroika

''Perestroika'' (; russian: links=no, перестройка, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg) was a political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s widely associated wit ...

(1990–1991)

Ukrainianization

Following the Russian Revolution, the Russian Empire was broken up. In different parts of the former empire, several nations, including Ukrainians, developed a renewed sense of national identity. In the chaotic post-revolutionary years the Ukrainian language gained some usage in government affairs. Initially, this trend continued under the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

government of the Soviet Union, which in a political struggle to retain its grip over the territory had to encourage the national movements of the former Russian Empire. While trying to ascertain and consolidate its power, the Bolshevik government was by far more concerned about many political oppositions connected to the pre-revolutionary order than about the national movements inside the former empire, where it could always find allies.

The widening use of Ukrainian further developed in the first years of Bolshevik rule into a policy called

The widening use of Ukrainian further developed in the first years of Bolshevik rule into a policy called korenizatsiya

Korenizatsiya ( rus, коренизация, p=kərʲɪnʲɪˈzatsɨjə, , "indigenization") was an early policy of the Soviet Union for the integration of non-Russian nationalities into the governments of their specific Soviet republics. In th ...

. The government pursued a policy of Ukrainianization

Ukrainization (also spelled Ukrainisation), sometimes referred to as Ukrainianization (or Ukrainianisation) is a policy or practice of increasing the usage and facilitating the development of the Ukrainian language and promoting other elements of ...

by lifting a ban on the Ukrainian language. That led to the introduction of an impressive education program which allowed Ukrainian-taught classes and raised the literacy of the Ukrainophone population. This policy was led by Education Commissar Mykola Skrypnyk

Mykola Oleksiiovych Skrypnyk ( uk, Микола Олексійович Скрипник; – 7 July 1933), also known as Nikolai Alekseyevich Skripnik (russian: Никола́й Алексе́евич Скри́пник), was a Ukrainian Bolshe ...

and was directed to approximate the language to Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

* Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and p ...

.

Newly generated academic efforts from the period of independence were co-opted by the Bolshevik government. The party and government apparatus was mostly Russian-speaking but were encouraged to learn the Ukrainian language. Simultaneously, the newly literate ethnic Ukrainians migrated to the cities, which became rapidly largely Ukrainianized – in both population and in education.

The policy even reached those regions of southern Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

where the ethnic Ukrainian population was significant, particularly the areas by the Don River

The Don ( rus, Дон, p=don) is the fifth-longest river in Europe. Flowing from Central Russia to the Sea of Azov in Southern Russia, it is one of Russia's largest rivers and played an important role for traders from the Byzantine Empire.

Its ...

and especially Kuban in the North Caucasus

The North Caucasus, ( ady, Темыр Къафкъас, Temır Qafqas; kbd, Ишхъэрэ Къаукъаз, İṩxhərə Qauqaz; ce, Къилбаседа Кавказ, Q̇ilbaseda Kavkaz; , os, Цӕгат Кавказ, Cægat Kavkaz, inh, ...

. Ukrainian language teachers, just graduated from expanded institutions of higher education in Soviet Ukraine, were dispatched to these regions to staff newly opened Ukrainian schools or to teach Ukrainian as a second language in Russian schools. A string of local Ukrainian-language publications were started and departments of Ukrainian studies were opened in colleges. Overall, these policies were implemented in thirty-five raions

A raion (also spelt rayon) is a type of administrative unit of several post-Soviet states. The term is used for both a type of subnational entity and a division of a city. The word is from the French (meaning 'honeycomb, department'), and is com ...

(administrative districts) in southern Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eight ...

.

Persecution and russification

Soviet policy towards the Ukrainian language changed abruptly in late 1932 and early 1933, with the termination of the policy of Ukrainianization. In December 1932, the regional party cells received a telegram signed by V. Molotov and Stalin with an order to immediately reverse the Ukrainianization policies. The telegram condemned Ukrainianization as ill-considered and harmful and demanded to "immediately halt Ukrainianization in raions (districts), switch all Ukrainianized newspapers, books and publications into Russian and prepare by autumn of 1933 for the switching of schools and instruction into Russian".

Western and most contemporary Ukrainian historians emphasize that the cultural repression was applied earlier and more fiercely in Ukraine than in other parts of the Soviet Union, and were therefore anti-Ukrainian; others assert that Stalin's goal was the generic crushing of any dissent, rather than targeting the Ukrainians in particular.

Stalinist policies shifted to define Russian as the language of (inter-ethnic) communication. Although Ukrainian continued to be used (in print, education, radio and later television programs), it lost its primary place in advanced learning and republic-wide media. Ukrainian was demoted to a language of secondary importance, often associated with the rise in Ukrainian self-awareness and nationalism and often branded "politically incorrect". The new Soviet Constitution adopted in 1936, however, stipulated that teaching in schools should be conducted in native languages.

Major repression started in 1929–30, when a large group of Ukrainian intelligentsia was arrested and most were executed. In Ukrainian history, this group is often referred to as "

Soviet policy towards the Ukrainian language changed abruptly in late 1932 and early 1933, with the termination of the policy of Ukrainianization. In December 1932, the regional party cells received a telegram signed by V. Molotov and Stalin with an order to immediately reverse the Ukrainianization policies. The telegram condemned Ukrainianization as ill-considered and harmful and demanded to "immediately halt Ukrainianization in raions (districts), switch all Ukrainianized newspapers, books and publications into Russian and prepare by autumn of 1933 for the switching of schools and instruction into Russian".

Western and most contemporary Ukrainian historians emphasize that the cultural repression was applied earlier and more fiercely in Ukraine than in other parts of the Soviet Union, and were therefore anti-Ukrainian; others assert that Stalin's goal was the generic crushing of any dissent, rather than targeting the Ukrainians in particular.

Stalinist policies shifted to define Russian as the language of (inter-ethnic) communication. Although Ukrainian continued to be used (in print, education, radio and later television programs), it lost its primary place in advanced learning and republic-wide media. Ukrainian was demoted to a language of secondary importance, often associated with the rise in Ukrainian self-awareness and nationalism and often branded "politically incorrect". The new Soviet Constitution adopted in 1936, however, stipulated that teaching in schools should be conducted in native languages.

Major repression started in 1929–30, when a large group of Ukrainian intelligentsia was arrested and most were executed. In Ukrainian history, this group is often referred to as "Executed Renaissance

The Executed Renaissance (or "Red Renaissance", uk, Розстріляне відродження, Червоний ренесанс, translit=Rozstriliane vidrodzhennia, Chervonyi renesans) is a term used to describe the generatio ...

" (Ukrainian: розстріляне відродження). "Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism

In Marxism, bourgeois nationalism is the practice by the ruling classes of deliberately dividing people by nationality, race, ethnicity, or religion, so as to distract them from engaging in class struggle. It is seen as a divide-and-conquer strat ...

" was declared to be the primary problem in Ukraine. The terror peaked in 1933, four to five years before the Soviet-wide " Great Purge", which, for Ukraine, was a second blow. The vast majority of leading scholars and cultural leaders of Ukraine were liquidated, as were the "Ukrainianized" and "Ukrainianizing" portions of the Communist party.

Soviet Ukraine's autonomy was completely destroyed by the late 1930s. In its place, the glorification of Russia as the first nation to throw off the capitalist yoke had begun, accompanied by the migration of Russian workers into parts of Ukraine which were undergoing industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econom ...

and mandatory instruction of classic Russian language and literature. Ideologists warned of over-glorifying Ukraine's Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

past, and supported the closing of Ukrainian cultural institutions and literary publications. The systematic assault upon Ukrainian identity in culture and education, combined with effects of an artificial famine ('' Holodomor'') upon the peasantry—the backbone of the nation—dealt Ukrainian language and identity a crippling blow.

This sequence of policy change was repeated in Western Ukraine when it was incorporated into Soviet Ukraine. In 1939, and again in the late 1940s, a policy of Ukrainianization was implemented. By the early 1950s, Ukrainian was persecuted and a campaign of Russification began.

Khrushchev thaw

After the death of Stalin (1953), a general policy of relaxing the language policies of the past was implemented (1958 to 1963). The Khrushchev era which followed saw a policy of relatively lenient concessions to development of the languages at the local and republic level, though its results in Ukraine did not go nearly as far as those of the Soviet policy of Ukrainianization in the 1920s. Journals and encyclopedic publications advanced in the Ukrainian language during the Khrushchev era, as well as transfer of Crimea under Ukrainian SSR jurisdiction.

Yet, the 1958 school reform that allowed parents to choose the language of primary instruction for their children, unpopular among the circles of the national intelligentsia in parts of the USSR, meant that non-Russian languages would slowly give way to Russian in light of the pressures of survival and advancement. The gains of the past, already largely reversed by the Stalin era, were offset by the liberal attitude towards the requirement to study the local languages (the requirement to study Russian remained).

Parents were usually free to choose the language of study of their children (except in few areas where attending the Ukrainian school might have required a long daily commute) and they often chose Russian, which reinforced the resulting Russification. In this sense, some analysts argue that it was not the "oppression" or "persecution", but rather the ''lack of

After the death of Stalin (1953), a general policy of relaxing the language policies of the past was implemented (1958 to 1963). The Khrushchev era which followed saw a policy of relatively lenient concessions to development of the languages at the local and republic level, though its results in Ukraine did not go nearly as far as those of the Soviet policy of Ukrainianization in the 1920s. Journals and encyclopedic publications advanced in the Ukrainian language during the Khrushchev era, as well as transfer of Crimea under Ukrainian SSR jurisdiction.

Yet, the 1958 school reform that allowed parents to choose the language of primary instruction for their children, unpopular among the circles of the national intelligentsia in parts of the USSR, meant that non-Russian languages would slowly give way to Russian in light of the pressures of survival and advancement. The gains of the past, already largely reversed by the Stalin era, were offset by the liberal attitude towards the requirement to study the local languages (the requirement to study Russian remained).

Parents were usually free to choose the language of study of their children (except in few areas where attending the Ukrainian school might have required a long daily commute) and they often chose Russian, which reinforced the resulting Russification. In this sense, some analysts argue that it was not the "oppression" or "persecution", but rather the ''lack of protection

Protection is any measure taken to guard a thing against damage caused by outside forces. Protection can be provided to physical objects, including organisms, to systems, and to intangible things like civil and political rights. Although th ...

'' against the expansion of Russian language that contributed to the relative decline of Ukrainian in the 1970s and 1980s. According to this view, it was inevitable that successful careers required a good command of Russian, while knowledge of Ukrainian was not vital, so it was common for Ukrainian parents to send their children to Russian-language schools, even though Ukrainian-language schools were usually available.

While in the Russian-language schools within the republic, Ukrainian was supposed to be learned as a second language at comparable level, the instruction of other subjects was in Russian and, as a result, students had a greater command of Russian than Ukrainian on graduation. Additionally, in some areas of the republic, the attitude towards teaching and learning of Ukrainian in schools was relaxed and it was, sometimes, considered a subject of secondary importance and even a waiver from studying it was sometimes given under various, ever expanding, circumstances.

The complete suppression of all expressions of separatism or Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism refers to the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and it also refers to the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The nation building that arose as nationalism grew following the French Revo ...

also contributed to lessening interest in Ukrainian. Some people who persistently used Ukrainian on a daily basis were often perceived as though they were expressing sympathy towards, or even being members of, the political opposition. This, combined with advantages given by Russian fluency and usage, made Russian the primary language of choice for many Ukrainians, while Ukrainian was more of a hobby. In any event, the mild liberalization in Ukraine and elsewhere was stifled by new suppression of freedoms at the end of the Khrushchev era (1963) when a policy of gradually creeping suppression of Ukrainian was re-instituted.

The next part of the Soviet Ukrainian language policy divides into two eras: first, the Shelest period (early 1960s to early 1970s), which was relatively liberal towards the development of the Ukrainian language. The second era, the policy of Shcherbytsky (early 1970s to early 1990s), was one of gradual suppression of the Ukrainian language.

Shelest period

The Communist Party leader from 1963 to 1972, Petro Shelest

Petro Yukhymovych Shelestrussian: Пётр Ефи́мович Ше́лест, translit=Pyotr Yefimovich Shelest (14 February 190822 January 1996) was a Ukrainian Soviet politician. First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Ukrainian Sovie ...

, pursued a policy of defending Ukraine's interests within the Soviet Union. He proudly promoted the beauty of the Ukrainian language and developed plans to expand the role of Ukrainian in higher education. He was removed, however, after only a brief tenure, for being too lenient on Ukrainian nationalism.

Shcherbytsky period

The new party boss from 1972 to 1989, Volodymyr Shcherbytsky

Volodymyr Vasylyovych Shcherbytsky, russian: Влади́мир Васи́льевич Щерби́цкий; ''Vladimir Vasilyevich Shcherbitsky'', (17 February 1918 — 16 February 1990) was a Ukrainian Soviet politician. He was First Sec ...

, purged the local party, was fierce in suppressing dissent, and insisted Russian be spoken at all official functions, even at local levels. His policy of Russification was lessened only slightly after 1985.

Gorbachev and perebudova

The management of dissent by the local Ukrainian Communist Party

The Ukrainian Communist Party ( uk, Українська Комуністична Партія, ''Ukrayins’ka Komunistychna Partiya'') was an oppositional political party in Soviet Ukraine, from 1920 until 1925. Its followers were known as Ukap ...

was more fierce and thorough than in other parts of the Soviet Union. As a result, at the start of the Mikhail Gorbachev reforms perebudova and hlasnist’ (Ukrainian for ''perestroika'' and ''glasnost''), Ukraine under Shcherbytsky was slower to liberalize than Russia itself.

Although Ukrainian still remained the native language for the majority in the nation on the eve of Ukrainian independence, a significant share of ethnic Ukrainians were russified. In Donetsk there were no Ukrainian language schools and in Kyiv only a quarter of children went to Ukrainian language schools.

The Russian language was the dominant vehicle, not just of government function, but of the media, commerce, and modernity itself. This was substantially less the case for western Ukraine, which escaped the artificial famine, Great Purge, and most of Stalinism. And this region became the center of a hearty, if only partial, renaissance of the Ukrainian language during independence.

Independence in the modern era

Since 1991, Ukrainian has been the official state language in Ukraine, and the state administration implemented government policies to broaden the use of Ukrainian. The educational system in Ukraine has been transformed over the first decade of independence from a system that is partly Ukrainian to one that is overwhelmingly so. The government has also mandated a progressively increased role for Ukrainian in the media and commerce.

In some cases the abrupt changing of the language of instruction in institutions of secondary and higher education led to the charges of

Since 1991, Ukrainian has been the official state language in Ukraine, and the state administration implemented government policies to broaden the use of Ukrainian. The educational system in Ukraine has been transformed over the first decade of independence from a system that is partly Ukrainian to one that is overwhelmingly so. The government has also mandated a progressively increased role for Ukrainian in the media and commerce.

In some cases the abrupt changing of the language of instruction in institutions of secondary and higher education led to the charges of Ukrainianization

Ukrainization (also spelled Ukrainisation), sometimes referred to as Ukrainianization (or Ukrainianisation) is a policy or practice of increasing the usage and facilitating the development of the Ukrainian language and promoting other elements of ...

, raised mostly by the Russian-speaking population. This transition, however, lacked most of the controversies that arose during the de- russification of the other former Soviet Republics

The Republics of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics or the Union Republics ( rus, Сою́зные Респу́блики, r=Soyúznye Respúbliki) were national-based administrative units of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics ( ...

.

With time, most residents, including ethnic Russians, people of mixed origin, and Russian-speaking Ukrainians, started to self-identify as Ukrainian nationals, even those who remained Russophone

This article details the geographical distribution of Russian-speakers. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the status of the Russian language often became a matter of controversy. Some Post-Soviet states adopted policies of derus ...

. The Russian language, however, still dominates the print media in most of Ukraine and private radio and TV broadcasting in the eastern, southern, and, to a lesser degree, central regions. The state-controlled broadcast media have become exclusively Ukrainian. There are few obstacles to the usage of Russian in commerce and it is still occasionally used in government affairs.

Late 20th-century Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eight ...

n politicians like Alexander Lebed

Lieutenant General Alexander Ivanovich Lebed (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Ле́бедь, link=no; 20 April 1950 – 28 April 2002) was a Soviet and Russian military officer and politician who held senior positions in the A ...

and Mikhail Yuryev

Mikhail Zinovyevich Yuryev (russian: Михаил Зиновьевич Юрьев; 10 April 1959 – 15 February 2019) was a Russian politician who served as a member of the State Duma between 1996 and 1999.

Yuryev came from a Jewish family. His ...

still claimed that Ukrainian is a Russian dialect.[Contemporary Ukraine: Dynamics of Post-Soviet Transformation]

by Taras Kuzio, M.E. Sharpe

M. E. Sharpe, Inc., an academic publisher, was founded by Myron Sharpe in 1958 with the original purpose of publishing translations from Russian in the social sciences and humanities. These translations were published in a series of journals, the ...

, 1998, (page 35)

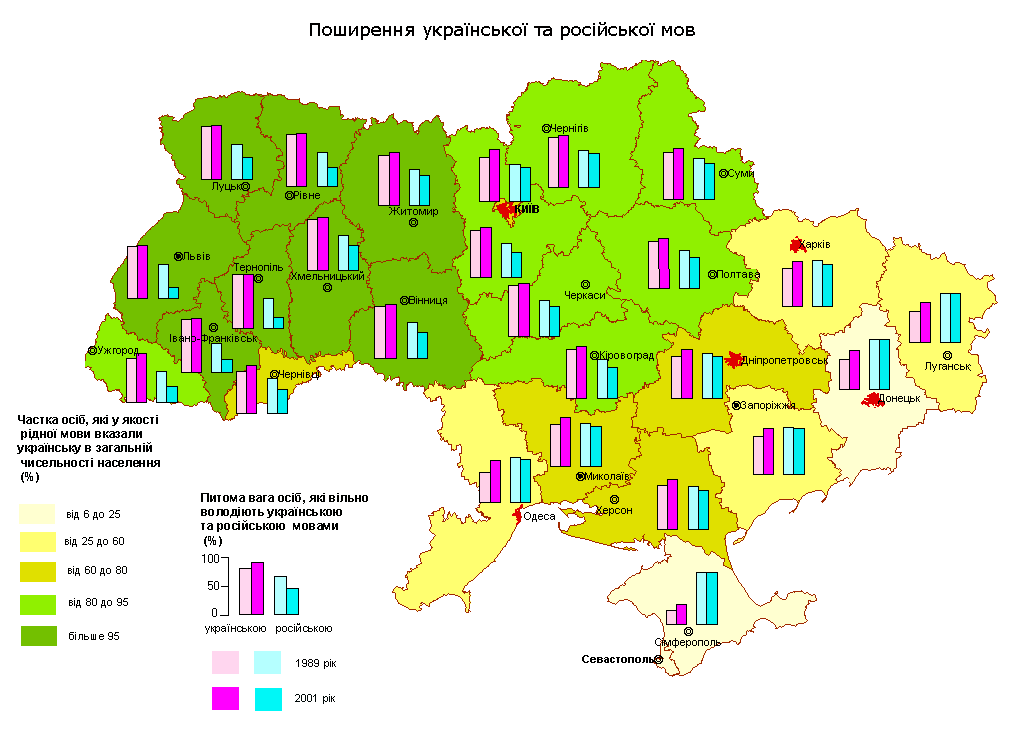

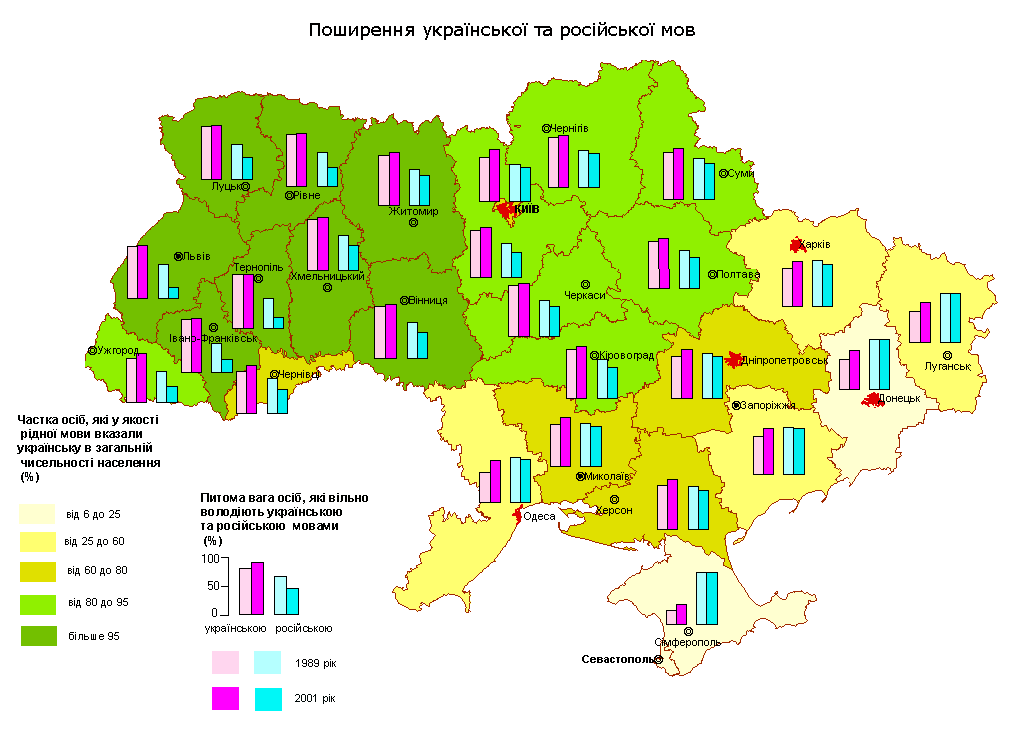

In the 2001 census, 67.5% of the country's population named Ukrainian as their native language (a 2.8% increase from 1989), while 29.6% named Russian (a 3.2% decrease). For many Ukrainians (of various ethnic origins), the term '' native language'' may not necessarily associate with the language they use more frequently. The overwhelming majority of ethnic Ukrainians consider the Ukrainian language ''native'', including those who often speak Russian.[

According to the official 2001 census data, 92.3% of Kyiv region population responded "Ukrainian" to the ''native language'' (''ridna mova'') census question, compared with 88.4% in 1989, and 7.2% responded "Russian".][ On the other hand, when the question "What language do you use in everyday life?" was asked in the sociological survey, the Kyivans' answers were distributed as follows: "mostly Russian": 52%, "both Russian and Ukrainian in equal measure": 32%, "mostly Ukrainian": 14%, "exclusively Ukrainian": 4.3%.

Ethnic minorities, such as Romanians, Tatars and Jews usually use Russian as their lingua franca. But there are tendencies within these minority groups to use Ukrainian. The Jewish writer Olexander Beyderman from the mainly Russian-speaking city of Odessa is now writing most of his dramas in Ukrainian. The emotional relationship regarding Ukrainian is changing in southern and eastern areas.

Opposition to expansion of Ukrainian-language teaching is a matter of contention in eastern regions closer to Russia – in May 2008, the Donetsk city council prohibited the creation of any new Ukrainian schools in the city in which 80% of them are ]Russian-language

Russian (russian: русский язык, russkij jazyk, link=no, ) is an East Slavic language mainly spoken in Russia. It is the native language of the Russians, and belongs to the Indo-European language family. It is one of four living E ...

schools.

In 2019, the law "On supporting the functioning of the Ukrainian language as the State language" was approved by the Ukrainian parliament, formalizing rules governing the usage of Ukrainian and introducing penalties for violations. For its enforcement the office of Language ombudsman was introduced.

Literature and literary language

The literary Ukrainian language, which was preceded by Old East Slavic literature, may be subdivided into two stages: during the 12th to 18th centuries what in Ukraine is referred to as "Old Ukrainian", but elsewhere, and in contemporary sources, is known as the Ruthenian language, and from the end of the 18th century to the present what in Ukraine is known as "Modern Ukrainian", but elsewhere is known as just Ukrainian.

Influential literary figures in the development of modern Ukrainian literature include the philosopher Hryhorii Skovoroda, Ivan Kotlyarevsky

Ivan Petrovych Kotliarevsky ( uk, Іван Петрович Котляревський) ( in Poltava – in Poltava, Russian Empire, now Ukraine) was a Ukrainian writer, poet and playwright, social activist, regarded as the pioneer of modern Ukr ...

, Mykola Kostomarov

Mykola Ivanovych Kostomarov or Nikolai Ivanovich Kostomarov (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Костома́ров, ; uk, Микола Іванович Костомаров, ; May 16, 1817, vil. Yurasovka, Voronezh Governorate, R ...

, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko ( uk, Тарас Григорович Шевченко , pronounced without the middle name; – ), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (a kobzar is a bard in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukrainian poet, wr ...

, Ivan Franko, and Lesia Ukrainka

Lesya Ukrainka ( uk, Леся Українка ; born Larysa Petrivna Kosach, uk, Лариса Петрівна Косач; – ) was one of Ukrainian literature's foremost writers, best known for her poems and plays. She was also an active ...

. The earliest literary work in the Ukrainian language was recorded in 1798 when Ivan Kotlyarevsky

Ivan Petrovych Kotliarevsky ( uk, Іван Петрович Котляревський) ( in Poltava – in Poltava, Russian Empire, now Ukraine) was a Ukrainian writer, poet and playwright, social activist, regarded as the pioneer of modern Ukr ...

, a playwright from Poltava in southeastern Ukraine, published his epic poem, ''Eneyida'', a burlesque

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects. in Ukrainian, based on Virgil's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled the fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the ...

''. His book was published in vernacular Ukrainian in a satirical way to avoid being censored, and is the earliest known Ukrainian published book to survive through Imperial and, later, Soviet policies on the Ukrainian language.

Kotlyarevsky's work and that of another early writer using the Ukrainian vernacular language, Petro Artemovsky, used the southeastern dialect spoken in the Poltava, Kharkiv and southern Kyiven regions of the Russian Empire. This dialect would serve as the basis of the Ukrainian literary language when it was developed by Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko ( uk, Тарас Григорович Шевченко , pronounced without the middle name; – ), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (a kobzar is a bard in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukrainian poet, wr ...

and Panteleimon Kulish

Panteleimon Oleksandrovych Kulish (also spelled ''Panteleymon'' or ''Pantelejmon Kuliš'', uk, Пантелеймон Олександрович Куліш, August 7, 1819 – February 14, 1897) was a Ukrainian writer, critic, poet, folkloris ...

in the mid 19th century. In order to raise its status from that of a dialect to that of a language, various elements from folklore and traditional styles were added to it.

Current usage

The use of the Ukrainian language is increasing after a long period of decline. Although there are almost fifty million ethnic Ukrainians worldwide, including 37.5 million in Ukraine in 2001 (77.8% of the total population at the time), the Ukrainian language is prevalent mainly in western and central Ukraine. In Kyiv, both Ukrainian and Russian are spoken, a notable shift from the recent past when the city was primarily Russian-speaking.

The use of the Ukrainian language is increasing after a long period of decline. Although there are almost fifty million ethnic Ukrainians worldwide, including 37.5 million in Ukraine in 2001 (77.8% of the total population at the time), the Ukrainian language is prevalent mainly in western and central Ukraine. In Kyiv, both Ukrainian and Russian are spoken, a notable shift from the recent past when the city was primarily Russian-speaking.[D-M.com.ua](_blank)

In August 2022, a survey in Ukraine by Rating Group found that 85% said they speak Ukrainian or Ukrainian and Russian at home, 51% only Ukrainian, an increase from 61% and 44% in February 2014.

Popular culture

Music

Ukrainian has become popular in other countries through movies and songs performed in the Ukrainian language. The most popular Ukrainian rock

Ukrainian rock ( uk, Український рок) is rock music from Ukraine.

While it is rock it is important for those who follow Ukrainian contemporary music to understand the VIA music scene of the 1970s and 1980s. This controlled form of ...

bands, such as Okean Elzy

Okean Elzy ( uk, Океан Ельзи, translation: ''Elza's Ocean'') is a Ukrainian rock band. It was formed in 1994 in Lviv, Ukraine. The band's vocalist and frontman is Svyatoslav Vakarchuk. In April 2007 Okean Elzy received ''FUZZ Magazine' ...

, Vopli Vidopliassova

Vopli Vidopliassova ( uk, Воплі Відоплясова ), also shortened to VV (), is a Ukrainian rock band. It was created in 1986 in Kyiv, in the Ukrainian SSR of the Soviet Union (present-day Ukraine). The leader of the band is singer ...

, BoomBox

A boombox is a transistorized portable music player featuring one or two cassette tape recorder/players and AM/FM radio, generally with a carrying handle. Beginning in the mid 1980s, a CD player was often included. Sound is delivered throug ...

perform regularly in tours across Europe, Israel, North America and especially Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eight ...

. In countries with significant Ukrainian populations, bands singing in the Ukrainian language sometimes reach top places on the charts, such as Enej (a band from Poland). Other notable Ukrainian-language bands are The Ukrainians

The Ukrainians are a British band, which plays traditional Ukrainian music, heavily influenced by western post-punk.

Career

The Ukrainians were formed in 1990 by Wedding Present guitarist Peter Solowka, with singer/violinist Len Liggins and ...

from the United Kingdom, Klooch from Canada, Ukrainian Village Band from the United States, and the Kuban Cossack Choir

Kuban Cossack Chorus (russian: Кубанский Казачий Хор, uk, Кубанський козачий хор) is one of the leading Folkloric ensembles in Russia. Its repertoire and performances reflect the songs, dances and folklo ...

from the Kuban region in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eight ...

.

Cinema

The 2010s saw a revival of Ukrainian cinema. The top Ukrainian-language films (by IMDb rating) are:

Argots

Oleksa Horbach's 1951 study of argots analyzed historical primary sources (argots of professionals, thugs, prisoners, homeless, school children, etc.) paying special attention to etymological features of argots, word formation and borrowing patterns depending on the source-language (Church Slavonic, Russian, Czech, Polish, Romani, Greek, Romanian, Hungarian, German).

Dialects

Several modern dialects of Ukrainian exist

* Northern (Polissian) dialects:

** (3) ''Eastern Polissian'' is spoken in

Several modern dialects of Ukrainian exist

* Northern (Polissian) dialects:

** (3) ''Eastern Polissian'' is spoken in Chernihiv

Chernihiv ( uk, Черні́гів, , russian: Черни́гов, ; pl, Czernihów, ; la, Czernihovia), is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within t ...

(excluding the southeastern districts), in the northern part of Sumy, and in the southeastern portion of the Kyiv Oblast as well as in the adjacent areas of Russia, which include the southwestern part of the Bryansk Oblast

Bryansk Oblast (russian: Бря́нская о́бласть, ''Bryanskaya oblast''), also known as Bryanshchina (russian: Брянщина, ) is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast). Its administrative center is the city of Bryansk. As of t ...

(the area around Starodub), as well as in some places in the Kursk

Kursk ( rus, Курск, p=ˈkursk) is a city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur, Tuskar, and Seym rivers. The area around Kursk was the site of a turning point in the Soviet–German str ...

, Voronezh and Belgorod

Belgorod ( rus, Белгород, p=ˈbʲeɫɡərət) is a city and the administrative center of Belgorod Oblast, Russia, located on the Seversky Donets River north of the border with Ukraine. Population: Demographics

The population of ...

Oblasts. No linguistic border can be defined. The vocabulary approaches Russian as the language approaches the Russian Federation. Both Ukrainian and Russian grammar sets can be applied to this dialect.Brest Voblast

Brest Region or Brest Oblast or Brest Voblasts ( be, Брэ́сцкая во́бласць ''(Bresckaja vobłasć)''; russian: Бре́стская о́бласть (''Brestskaya Oblast)'') is one of the regions of Belarus. Its administrative cent ...

in Belarus. The dialect spoken in Belarus uses Belarusian grammar and thus is considered by some to be a dialect of Belarusian.

* Southeastern dialects:

** (4) ''Middle Dnieprian'' is the basis of the Standard Standard may refer to:

Symbols

* Colours, standards and guidons, kinds of military signs

* Standard (emblem), a type of a large symbol or emblem used for identification

Norms, conventions or requirements

* Standard (metrology), an object ...

Literary Ukrainian. It is spoken in the central part of Ukraine, primarily in the southern and eastern part of the Kyiv Oblast. In addition, the dialects spoken in Cherkasy

Cherkasy ( uk, Черка́си, ) is a city in central Ukraine. Cherkasy is the capital of Cherkasy Oblast (province), as well as the administrative center of Cherkasky Raion (district) within the oblast. The city has a population of

Ch ...

, Poltava, and Kyiv regions are considered to be close to "standard" Ukrainian.

** (5) ''Slobodan'' is spoken in Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine. , Sumy, Luhansk, and the northern part of Donetsk, as well as in the Voronezh and Belgorod

Belgorod ( rus, Белгород, p=ˈbʲeɫɡərət) is a city and the administrative center of Belgorod Oblast, Russia, located on the Seversky Donets River north of the border with Ukraine. Population: Demographics

The population of ...

regions of Russia. This dialect is formed from a gradual mixture of Russian and Ukrainian, with progressively more Russian in the northern and eastern parts of the region. Thus, there is no linguistic border between Russian and Ukrainian, and, thus, both grammar sets can be applied.Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, Військо Запорізьке, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, Запорожці, translit=Zaporoz ...

.

** A ''Kuban'' dialect related to or based on the Steppe dialect is often referred to as ''Balachka

Baláchka ( uk, балачка, p=bɐˈlat͡ʃkɐ – conversation, chat) is a Ukrainian dialect spoken in the Kuban and Don regions, where Ukrainian settlers used to live. It was strongly influenced by Cossack culture.

The term is connecte ...

'' and is spoken by the Kuban Cossacks

Kuban Cossacks (russian: кубанские казаки, ''kubanskiye kаzaki''; uk, кубанські козаки, ''kubanski kozaky''), or Kubanians (russian: кубанцы, ; uk, кубанці, ), are Cossacks who live in the Kuban r ...

in the Kuban region in Russia by the descendants of the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, Військо Запорізьке, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, Запорожці, translit=Zaporoz ...

, who settled in that area in the late 18th century. It was formed from a gradual mixture of Russian into Ukrainian. This dialect features the use of some Russian vocabulary along with some Russian grammar.[Viktor Zakharchenko, Folk songs of the Kuban, 1997 , Retrieved 7 November 2007] There are three main variants, which have been grouped together according to location.

* Southwestern dialects:

** (13) ''Boyko'' is spoken by the Boyko people on the northern side of the Carpathian Mountains in the Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukra ...

and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblasts. It can also be heard across the border in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship

Subcarpathian Voivodeship or Subcarpathia Province (in pl, Województwo podkarpackie ) is a voivodeship, or province, in the southeastern corner of Poland. Its administrative capital and largest city is Rzeszów. Along with the Marshall, it is ...

of Poland.