Tibet Police College on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in

The

The

The language has numerous regional dialects which are generally not mutually intelligible. It is employed throughout the Tibetan plateau and

The language has numerous regional dialects which are generally not mutually intelligible. It is employed throughout the Tibetan plateau and

The history of a unified Tibet begins with the rule of

The history of a unified Tibet begins with the rule of  The

The

The Mongol

The Mongol

China's Tibet Policy

'', p. 139. Psychology Press. The

Between 1346 and 1354, Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen toppled the Sakya and founded the Phagmodrupa Dynasty. The following 80 years saw the founding of the

Between 1346 and 1354, Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen toppled the Sakya and founded the Phagmodrupa Dynasty. The following 80 years saw the founding of the

As the Qing dynasty weakened, its authority over Tibet also gradually declined, and by the mid-19th century, its influence was minuscule. Qing authority over Tibet had become more symbolic than real by the late 19th century, although in the 1860s, the Tibetans still chose for reasons of their own to emphasize the empire's symbolic authority and make it seem substantial.

In 1774, a Scottish

As the Qing dynasty weakened, its authority over Tibet also gradually declined, and by the mid-19th century, its influence was minuscule. Qing authority over Tibet had become more symbolic than real by the late 19th century, although in the 1860s, the Tibetans still chose for reasons of their own to emphasize the empire's symbolic authority and make it seem substantial.

In 1774, a Scottish

After the

After the

East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea and ...

, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the Ti ...

and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people

The Tibetan people (; ) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Tibet. Their current population is estimated to be around 6.7 million. In addition to the majority living in Tibet Autonomous Region of China, significant numbers of Tibetans live ...

. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa

The Monpa or Mönpa () is a major tribe of Arunachal Pradesh in northeastern India. The Tawang Monpas have a migration history from Changrelung. The Monpa are believed to be the only nomadic tribe in Northeast India – they are totally dependen ...

, Tamang

The Tamang (; Devanagari: तामाङ; ''tāmāṅ'') are an Tibeto-Burmese ethnic group of Nepal. In Nepal Tamang/Moormi people constitute 5.6% of the Nepalese population at over 1.3 million in 2001, increasing to 1,539,830 as of the 2011 c ...

, Qiang, Sherpa Sherpa may refer to:

Ethnography

* Sherpa people, an ethnic group in north eastern Nepal

* Sherpa language

Organizations and companies

* Sherpa (association), a French network of jurists dedicated to promoting corporate social responsibility

* ...

and Lhoba people

Lhoba (English translation: ; ; bo, ལྷོ་པ།) is any of a diverse amalgamation of Sino-Tibetan-speaking tribespeople living in and around Pemako, a region in southeastern Tibet including Mainling, Medog and Zayü counties of Nying ...

s and now also considerable numbers of Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive va ...

and Hui

The Hui people ( zh, c=, p=Huízú, w=Hui2-tsu2, Xiao'erjing: , dng, Хуэйзў, ) are an East Asian ethnoreligious group predominantly composed of Chinese-speaking adherents of Islam. They are distributed throughout China, mainly in the n ...

settlers. Since 1951

Events

January

* January 4 – Korean War: Third Battle of Seoul – Chinese and North Korean forces capture Seoul for the second time (having lost the Second Battle of Seoul in September 1950).

* January 9 – The Government of the United ...

, the entire plateau has been under the administration of the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, a major portion in the Tibet Autonomous Region

The Tibet Autonomous Region or Xizang Autonomous Region, often shortened to Tibet or Xizang, is a Provinces of China, province-level Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People's Republic of China in Southwest China. I ...

, and other portions in the Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

and Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of the ...

provinces.

Tibet is the highest region on Earth, with an average elevation of . Located in the Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

, the highest elevation in Tibet is Mount Everest

Mount Everest (; Tibetan: ''Chomolungma'' ; ) is Earth's highest mountain above sea level, located in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas. The China–Nepal border runs across its summit point. Its elevation (snow heig ...

, Earth's highest mountain, rising 8,848.86 m (29,032 ft) above sea level.

The Tibetan Empire

The Tibetan Empire (, ; ) was an empire centered on the Tibetan Plateau, formed as a result of imperial expansion under the Yarlung dynasty heralded by its 33rd king, Songtsen Gampo, in the 7th century. The empire further expanded under the 38 ...

emerged in the 7th century. At its height in the 9th century, the Tibetan Empire

The Tibetan Empire (, ; ) was an empire centered on the Tibetan Plateau, formed as a result of imperial expansion under the Yarlung dynasty heralded by its 33rd king, Songtsen Gampo, in the 7th century. The empire further expanded under the 38 ...

extended far beyond the Tibetan Plateau, from Central Asian's Tarim Basin

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Northwest China occupying an area of about and one of the largest basins in Northwest China.Chen, Yaning, et al. "Regional climate change and its effects on river runoff in the Tarim Basin, China." Hydr ...

and the Pamirs

The Pamir Mountains are a mountain range between Central Asia and Pakistan. It is located at a junction with other notable mountains, namely the Tian Shan, Karakoram, Kunlun, Hindu Kush and the Himalaya mountain ranges. They are among the world' ...

in the west to Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked Provinces of China, province in Southwest China, the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is ...

and Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

in the southeast. But once the process of fragmentation began, the empire divided into a variety of territories. The bulk of western and central Tibet (Ü-Tsang

Ü-Tsang is one of the three traditional provinces of Tibet, the others being Amdo in the north-east, and Kham in the east. Ngari (including former Guge kingdom) in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Geographically Ü-Tsang covere ...

) was often at least nominally unified under a series of Tibetan governments in Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level city, prefecture-level Lhasa (prefecture-level city), Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Regio ...

, Shigatse

Shigatse, officially known as Xigazê (; Nepali: ''सिगात्से''), is a prefecture-level city of the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. Its area of jurisdiction, with an area of , corresponds to the histor ...

, or nearby locations. The eastern regions of Kham

Kham (; )

is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being Amdo in the northeast, and Ü-Tsang in central Tibet. The original residents of Kham are called Khampas (), and were governed locally by chieftains and monasteries. Kham ...

and Amdo

Amdo ( �am˥˥.to˥˥ ) is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being U-Tsang in the west and Kham in the east. Ngari (including former Guge kingdom) in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Amdo is also the bi ...

often maintained a more decentralized indigenous political structure, being divided among a number of small principalities and tribal groups, while also often falling more directly under Chinese rule; most of this area was eventually annexed into the Chinese provinces of Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of the ...

and Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

. The current borders of Tibet were generally established in the 18th century.

Following the Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of a d ...

against the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

in 1912, Qing soldiers were disarmed and escorted out of Tibet Area (Ü-Tsang). The region subsequently declared its independence in 1913 without recognition and permission by the subsequent Chinese Republican government. Later, Lhasa took control of the western part of Xikang

Xikang (also Sikang or Hsikang) was a nominal province

formed by the Republic of China in 1939 on the initiative of prominent Sichuan warlord Liu Wenhui and continued by the early People's Republic of China. Thei idea was to form a single unifi ...

. The region maintained its autonomy until 1951 when, following the Battle of Chamdo

The Battle of Chamdo (or Qamdo; ) occurred from 6 to 24 October 1950. It was a military campaign by the People's Republic of China (PRC) to take the Chamdo Region from a ''de facto'' independent Tibetan state.Shakya 1999 pp.28–32. The campai ...

, Tibet was occupied and annexed into the People's Republic of China, and the previous Tibetan government was abolished in 1959 after a failed uprising. Today, China governs western and central Tibet as the Tibet Autonomous Region

The Tibet Autonomous Region or Xizang Autonomous Region, often shortened to Tibet or Xizang, is a Provinces of China, province-level Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People's Republic of China in Southwest China. I ...

while the eastern areas are now mostly ethnic autonomous prefectures within Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of the ...

, Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

and other neighbouring provinces. There are tensions regarding Tibet's political status and dissident groups that are active in exile.

Tibetan activists in Tibet have reportedly been arrested or tortured.

With the growth of tourism in recent years, the service sector has become the largest sector in Tibet, accounting for 50.1% of the local GDP in 2020. The dominant religion in Tibet is Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism (also referred to as Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Lamaism, Lamaistic Buddhism, Himalayan Buddhism, and Northern Buddhism) is the form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Bhutan, where it is the dominant religion. It is also in majo ...

; other religions include Bön

''Bon'', also spelled Bön () and also known as Yungdrung Bon (, "eternal Bon"), is a Tibetan culture, Tibetan religious tradition with many similarities to Tibetan Buddhism and also many unique features.Samuel 2012, pp. 220-221. Bon initiall ...

, an indigenous religion similar to Tibetan Buddhism, Tibetan Muslims

Tibetan Muslims, also known as the Kachee (; ; also spelled Kache), form a small minority in Tibet. Despite being Muslim, they are officially recognized as Tibetans by the government of the People's Republic of China, unlike the Hui Muslims, ...

, and Christian minorities. Tibetan Buddhism is a primary influence on the art

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

There is no generally agreed definition of wha ...

, music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

, and festivals

A festival is an event ordinarily celebrated by a community and centering on some characteristic aspect or aspects of that community and its religion or cultures. It is often marked as a local or national holiday, mela, or eid. A festival co ...

of the region. Tibetan architecture reflects Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

and Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

influences. Staple foods in Tibet are roasted barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley pr ...

, yak

The domestic yak (''Bos grunniens''), also known as the Tartary ox, grunting ox or hairy cattle, is a species of long-haired domesticated cattle found throughout the Himalayan region of the Indian subcontinent, the Tibetan Plateau, Kachin Sta ...

meat, and butter tea

Butter tea, also known as ''po cha'' (, "Tibetan tea"), ''cha süma'' (, "churned tea"), Mandarin Chinese: ''sūyóu chá'' ( 酥 油 茶) or ''gur gur cha'' in the Ladakhi language, is a drink of the people in the Himalayan regions of Nepal, Bhut ...

.

Names

The

The Tibetan

Tibetan may mean:

* of, from, or related to Tibet

* Tibetan people, an ethnic group

* Tibetan language:

** Classical Tibetan, the classical language used also as a contemporary written standard

** Standard Tibetan, the most widely used spoken dial ...

name for their land, ''Bod'' (), means 'Tibet' or 'Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the Ti ...

', although it originally meant the central region around Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level city, prefecture-level Lhasa (prefecture-level city), Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Regio ...

, now known in Tibetan as ''Ü'' (). The Standard Tibetan

Lhasa Tibetan (), or Standard Tibetan, is the Tibetan dialect spoken by educated people of Lhasa, the capital of the Tibetan Autonomous Region of China. It is an official language of the Tibet Autonomous Region.

In the traditional "three-branch ...

pronunciation of ''Bod'' () is transcribed as: ''Bhö'' in Tournadre Phonetic Transcription; ''Bö'' in the THL Simplified Phonetic Transcription

The THL Simplified Phonetic Transcription of Standard Tibetan (or ''THL Phonetic Transcription'' for short) is a system for the phonetic rendering of the Tibetan language.

It was created by David Germano and Nicolas Tournadre and was published on ...

; and ''Poi'' in Tibetan pinyin. Some scholars believe the first written reference to ''Bod'' ('Tibet') was the ancient Bautai people recorded in the Egyptian-Greek works ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

The ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' ( grc, Περίπλους τῆς Ἐρυθρᾶς Θαλάσσης, ', modern Greek '), also known by its Latin name as the , is a Greco-Roman periplus written in Koine Greek that describes navigation and ...

'' (1st century CE) and ''Geographia

The ''Geography'' ( grc-gre, Γεωγραφικὴ Ὑφήγησις, ''Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis'', "Geographical Guidance"), also known by its Latin names as the ' and the ', is a gazetteer, an atlas, and a treatise on cartography, com ...

'' (Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

, 2nd century CE), itself from the Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

form ''Bhauṭṭa'' of the Indian geographical tradition.

The modern Standard Chinese

Standard Chinese ()—in linguistics Standard Northern Mandarin or Standard Beijing Mandarin, in common speech simply Mandarin, better qualified as Standard Mandarin, Modern Standard Mandarin or Standard Mandarin Chinese—is a modern Standar ...

exonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

for the ethnic Tibetan region is ''Zangqu'' (), which derives by metonymy

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something closely associated with that thing or concept.

Etymology

The words ''metonymy'' and ''metonym'' come from grc, μετωνυμία, 'a change of name' ...

from the Tsang region around Shigatse

Shigatse, officially known as Xigazê (; Nepali: ''सिगात्से''), is a prefecture-level city of the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. Its area of jurisdiction, with an area of , corresponds to the histor ...

plus the addition of a Chinese suffix (), which means 'area, district, region, ward'. Tibetan people, language, and culture, regardless of where they are from, are referred to as ''Zang'' (), although the geographical term is often limited to the Tibet Autonomous Region

The Tibet Autonomous Region or Xizang Autonomous Region, often shortened to Tibet or Xizang, is a Provinces of China, province-level Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People's Republic of China in Southwest China. I ...

. The term ''Xīzàng'' was coined during the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

in the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor

The Jiaqing Emperor (13 November 1760 – 2 September 1820), also known by his temple name Emperor Renzong of Qing, born Yongyan, was the sixth emperor of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and the fifth Qing emperor to rule over China proper, fro ...

(1796–1820) through the addition of the prefix (, 'west') to ''Zang''.

The best-known medieval Chinese name for Tibet is ''Tubo'' (; or , or , ). This name first appears in Chinese characters as in the 7th century (Li Tai

Li Tai (; 620 – 14 January 653), courtesy name Huibao (惠褒), nickname Qingque (青雀), formally Prince Gong of Pu (濮恭王), was an imperial prince of the Chinese Tang Dynasty.

Li Tai, who carried the title of Prince of Wei, was favored ...

) and as in the 10th-century (''Old Book of Tang

The ''Old Book of Tang'', or simply the ''Book of Tang'', is the first classic historical work about the Tang dynasty, comprising 200 chapters, and is one of the Twenty-Four Histories. Originally compiled during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdo ...

'', describing 608–609 emissaries from Tibetan King Namri Songtsen

Namri Songtsen (), also known as "Namri Löntsen" () (died 618) was according to tradition, the 32nd King of Tibet of the Yarlung Dynasty. (Reign: 570 – 618) During his 48 years of reign, he expanded his kingdom to rule the central part of the ...

to Emperor Yang of Sui

Emperor Yang of Sui (隋煬帝, 569 – 11 April 618), personal name Yang Guang (), alternative name Ying (), Xianbei name Amo (), also known as Emperor Ming of Sui () during the brief reign of his grandson Yang Tong, was the second emperor of ...

). In the Middle-Chinese language spoken during that period, as reconstructed by William H. Baxter

William Hubbard Baxter III (born March 3, 1949) is an American linguistics, linguist specializing in the history of the Chinese language and best known for Baxter's transcription for Middle Chinese, his work on the reconstruction on Old Chinese.

...

, was pronounced ''thu-phjon'', and was pronounced ''thu-pjon'' (with the ' representing a ''shang

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Chinese royal dynasty founded by Tang of Shang (Cheng Tang) that ruled in the Yellow River valley in the second millennium BC, traditionally succeeding the Xia dynasty and f ...

'' tone).

Other pre-modern Chinese names for Tibet include:

* ''Wusiguo'' (; cf.

The abbreviation ''cf.'' (short for the la, confer/conferatur, both meaning "compare") is used in writing to refer the reader to other material to make a comparison with the topic being discussed. Style guides recommend that ''cf.'' be used onl ...

Tibetan: ''dbus'', Ü, );

* ''Wusizang'' (, cf. Tibetan: ''dbus-gtsang'', Ü-Tsang

Ü-Tsang is one of the three traditional provinces of Tibet, the others being Amdo in the north-east, and Kham in the east. Ngari (including former Guge kingdom) in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Geographically Ü-Tsang covere ...

);

* ''Tubote'' (); and

* ''Tanggute'' (, cf. Tangut).

American Tibetologist

Tibetology () refers to the study of things related to Tibet, including its history, religion, language, culture, politics and the collection of Tibetan articles of historical, cultural and religious significance. The last may mean a collection of ...

Elliot Sperling

Elliot Sperling (January 4, 1951 – January 29, 2017) was one of the world's leading historians of Tibet and Tibetan-China, Chinese relations, and a MacArthur Fellow. He spent most of his scholarly career as an associate professor at Indiana Uni ...

has argued in favor of a recent tendency by some authors writing in Chinese to revive the term ''Tubote'' () for modern use in place of ''Xizang'', on the grounds that ''Tubote'' more clearly includes the entire Tibetan plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the Ti ...

rather than simply the Tibet Autonomous Region

The Tibet Autonomous Region or Xizang Autonomous Region, often shortened to Tibet or Xizang, is a Provinces of China, province-level Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People's Republic of China in Southwest China. I ...

.

The English word ''Tibet'' or ''Thibet'' dates back to the 18th century. Historical linguists

Historical linguistics, also termed diachronic linguistics, is the scientific study of language change over time. Principal concerns of historical linguistics include:

# to describe and account for observed changes in particular languages

# ...

generally agree that "Tibet" names in European languages are loanword

A loanword (also loan word or loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language. This is in contrast to cognates, which are words in two or more languages that are similar because th ...

s from Semitic or ( ar, طيبة، توبات; he, טובּה, טובּת), itself deriving from Turkic ' (plural of ), literally 'The Heights'.

Language

Linguists generally classify theTibetan language Tibetan language may refer to:

* Classical Tibetan, the classical language used also as a contemporary written standard

* Lhasa Tibetan, the most widely used spoken dialect

* Any of the other Tibetic languages

See also

*Old Tibetan, the language ...

as a Tibeto-Burman

The Tibeto-Burman languages are the non- Sinitic members of the Sino-Tibetan language family, over 400 of which are spoken throughout the Southeast Asian Massif ("Zomia") as well as parts of East Asia and South Asia. Around 60 million people spea ...

language of the Sino-Tibetan language

Sino-Tibetan, also cited as Trans-Himalayan in a few sources, is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers. The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Chinese languages. ...

family although the boundaries between 'Tibetan' and certain other Himalaya

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

n languages can be unclear. According to Matthew Kapstein

Matthew T. Kapstein is a scholar of Tibetan religions, Buddhism, and the cultural effects of the Chinese occupation of Tibet. He is Numata Visiting Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Chicago Divinity School, and Director of Tibetan ...

:From the perspective of historical linguistics, Tibetan most closely resembles Burmese among the major languages of Asia. Grouping these two together with other apparently related languages spoken in theHimalaya The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...n lands, as well as in the highlands of Southeast Asia and the Sino-Tibetan frontier regions, linguists have generally concluded that there exists a Tibeto-Burman family of languages. More controversial is the theory that the Tibeto-Burman family is itself part of a larger language family, calledSino-Tibetan Sino-Tibetan, also cited as Trans-Himalayan in a few sources, is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers. The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Chinese languages. ..., and that through it Tibetan and Burmese are distant cousins of Chinese.

The language has numerous regional dialects which are generally not mutually intelligible. It is employed throughout the Tibetan plateau and

The language has numerous regional dialects which are generally not mutually intelligible. It is employed throughout the Tibetan plateau and Bhutan

Bhutan (; dz, འབྲུག་ཡུལ་, Druk Yul ), officially the Kingdom of Bhutan,), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is situated in the Eastern Himalayas, between China in the north and India in the south. A mountainous ...

and is also spoken in parts of Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

and northern India, such as Sikkim

Sikkim (; ) is a state in Northeastern India. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Province No. 1 of Nepal in the west and West Bengal in the south. Sikkim is also close to the Siligur ...

. In general, the dialects of central Tibet (including Lhasa), Kham

Kham (; )

is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being Amdo in the northeast, and Ü-Tsang in central Tibet. The original residents of Kham are called Khampas (), and were governed locally by chieftains and monasteries. Kham ...

, Amdo

Amdo ( �am˥˥.to˥˥ ) is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being U-Tsang in the west and Kham in the east. Ngari (including former Guge kingdom) in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Amdo is also the bi ...

and some smaller nearby areas are considered Tibetan dialects. Other forms, particularly Dzongkha

Dzongkha (; ) is a Sino-Tibetan language that is the official and national language of Bhutan. It is written using the Tibetan script.

The word means "the language of the fortress", from ' "fortress" and ' "language". , Dzongkha had 171,080 n ...

, Sikkimese, Sherpa Sherpa may refer to:

Ethnography

* Sherpa people, an ethnic group in north eastern Nepal

* Sherpa language

Organizations and companies

* Sherpa (association), a French network of jurists dedicated to promoting corporate social responsibility

* ...

, and Ladakhi, are considered by their speakers, largely for political reasons, to be separate languages. However, if the latter group of Tibetan-type languages are included in the calculation, then 'greater Tibetan' is spoken by approximately 6 million people across the Tibetan Plateau. Tibetan is also spoken by approximately 150,000 exile speakers who have fled from modern-day Tibet to India and other countries.

Although spoken Tibetan varies according to the region, the written language, based on Classical Tibetan

Classical Tibetan refers to the language of any text written in Tibetic after the Old Tibetan period. Though it extends from the 12th century until the modern day, it particularly refers to the language of early canonical texts translated from oth ...

, is consistent throughout. This is probably due to the long-standing influence of the Tibetan empire, whose rule embraced (and extended at times far beyond) the present Tibetan linguistic area, which runs from Gilgit Baltistan

Gilgit (; Shina language, Shina: ; ur, ) is the capital city of Gilgit-Baltistan, Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan. The city is located in a broad valley near the confluence of the Gilgit River and the Hunza River. It is a major Tourism in Paki ...

in the west to Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked Provinces of China, province in Southwest China, the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is ...

and Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of the ...

in the east, and from north of Qinghai Lake

Qinghai Lake or Ch'inghai Lake, also known by other names, is the largest lake in China. Located in an endorheic basin in Qinghai Province, to which it gave its name, Qinghai Lake is classified as an alkaline salt lake. The lake has fluctuat ...

south as far as Bhutan. The Tibetan language has its own script which it shares with Ladakhi and Dzongkha

Dzongkha (; ) is a Sino-Tibetan language that is the official and national language of Bhutan. It is written using the Tibetan script.

The word means "the language of the fortress", from ' "fortress" and ' "language". , Dzongkha had 171,080 n ...

, and which is derived from the ancient Indian Brāhmī script

Brahmi (; ; ISO: ''Brāhmī'') is a writing system of ancient South Asia. "Until the late nineteenth century, the script of the Aśokan (non-Kharosthi) inscriptions and its immediate derivatives was referred to by various names such as 'lath' o ...

.

Starting in 2001, the local deaf sign language

Sign languages (also known as signed languages) are languages that use the visual-manual modality to convey meaning, instead of spoken words. Sign languages are expressed through manual articulation in combination with non-manual markers. Sign l ...

s of Tibet were standardized, and Tibetan Sign Language

Tibetan Sign Language is the recently established deaf sign language of Tibet.

Tibetan Sign is the first recognized sign language for a minority in China. The Tibetan Sign Language Project, staffed by members of the local deaf club, was set up ...

is now being promoted across the country.

The first Tibetan-English dictionary and grammar book was written by Alexander Csoma de Kőrös in 1834.

History

Early history

Humans inhabited the Tibetan Plateau at least 21,000 years ago. This population was largely replaced around 3,000 BP byNeolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

immigrants from northern China, but there is a partial genetic continuity between the Paleolithic inhabitants and contemporary Tibetan populations.

The earliest Tibetan historical texts identify the Zhang Zhung culture as a people who migrated from the Amdo region into what is now the region of Guge

Guge (; ) was an ancient dynastic kingdom in Western Tibet. The kingdom was centered in present-day Zanda County, Ngari Prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region. At various points in history after the 10th century AD, the kingdom held sway over a vast ...

in western Tibet.Norbu 1989, pp. 127–128 Zhang Zhung is considered to be the original home of the Bön

''Bon'', also spelled Bön () and also known as Yungdrung Bon (, "eternal Bon"), is a Tibetan culture, Tibetan religious tradition with many similarities to Tibetan Buddhism and also many unique features.Samuel 2012, pp. 220-221. Bon initiall ...

religion.Helmut Hoffman in McKay 2003 vol. 1, pp. 45–68 By the 1st century BCE, a neighboring kingdom arose in the Yarlung valley

The Yarlung Valley is formed by Yarlung Chu, a tributary of the Tsangpo river, Tsangpo River in the Shannan Prefecture in the Tibet Autonomous Region, Tibet region of China. It refers especially to the district where Yarlung Chu joins with the Cho ...

, and the Yarlung king, Drigum Tsenpo Drigum Tsenpo was an emperor of Tibet. According to Tibetan mythology, he was the first king of Tibet to lose his immortality when he angered his stable master, Lo-ngam. Legend states that rulers of Tibet descended from heaven to earth on a cord, ...

, attempted to remove the influence of the Zhang Zhung by expelling the Zhang's Bön priests from Yarlung. He was assassinated and Zhang Zhung continued its dominance of the region until it was annexed by Songtsen Gampo in the 7th century. Prior to Songtsen Gampo

Songtsen Gampo (; 569–649? 650), also Songzan Ganbu (), was the 33rd Tibetan king and founder of the Tibetan Empire, and is traditionally credited with the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet, influenced by his Nepali consort Bhrikuti, of Nepal ...

, the kings of Tibet were more mythological than factual, and there is insufficient evidence of their existence.

Tibetan Empire

The history of a unified Tibet begins with the rule of

The history of a unified Tibet begins with the rule of Songtsen Gampo

Songtsen Gampo (; 569–649? 650), also Songzan Ganbu (), was the 33rd Tibetan king and founder of the Tibetan Empire, and is traditionally credited with the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet, influenced by his Nepali consort Bhrikuti, of Nepal ...

(604–650CE), who united parts of the Yarlung River Valley and founded the Tibetan Empire. He also brought in many reforms, and Tibetan power spread rapidly, creating a large and powerful empire. It is traditionally considered that his first wife was the Princess of Nepal, Bhrikuti

Princess Bhrikuti Devi ( sa, भृकुटी, known to Tibetans as Bal-mo-bza' Khri-btsun, Bhelsa Tritsun (Nepal ), or simply, Khri bTsun ()) of Licchavi is traditionally considered to have been the first wife and queen of the earliest emperor ...

, and that she played a great role in the establishment of Buddhism in Tibet. In 640, he married Princess Wencheng

Princess Wencheng (; ) was a member of a minor branch of the royal clan of the Tang Dynasty who married King Songtsen Gampo of the Tibetan Empire in 641. She is also known by the name Gyasa or "Chinese wife" in Tibet. Some Tibetan historians cons ...

, the niece of the Chinese emperor Taizong of Tang China.

Under the next few Tibetan kings, Buddhism became established as the state religion and Tibetan power increased even further over large areas of Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

, while major inroads were made into Chinese territory, even reaching the Tang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) b ...

's capital Chang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin Shi ...

(modern Xi'an

Xi'an ( , ; ; Chinese: ), frequently spelled as Xian and also known by #Name, other names, is the list of capitals in China, capital of Shaanxi, Shaanxi Province. A Sub-provincial division#Sub-provincial municipalities, sub-provincial city o ...

) in late 763. However, the Tibetan occupation of Chang'an only lasted for fifteen days, after which they were defeated by Tang and its ally, the Turkic Uyghur Khaganate

The Uyghur Khaganate (also Uyghur Empire or Uighur Khaganate, self defined as Toquz-Oghuz country; otk, 𐱃𐰆𐰴𐰕:𐰆𐰍𐰕:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣, Toquz Oγuz budun, Tang-era names, with modern Hanyu Pinyin: or ) was a Turkic empire that e ...

.

The

The Kingdom of Nanzhao

Nanzhao (, also spelled Nanchao, ) was a dynastic kingdom that flourished in what is now southern China and northern Southeast Asia during the 8th and 9th centuries. It was centered on present-day Yunnan in China.

History

Origins

Nanzha ...

(in Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked Provinces of China, province in Southwest China, the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is ...

and neighbouring regions) remained under Tibetan control from 750 to 794, when they turned on their Tibetan overlords and helped the Chinese inflict a serious defeat on the Tibetans.

In 747, the hold of Tibet was loosened by the campaign of general Gao Xianzhi

Gao Xianzhi, or Go Seonji, (died January 24, 756) was a Tang dynasty general of Goguryeo descent. He was known as a great commander during his lifetime. He is most well known for taking part in multiple military expeditions to conquer the Western R ...

, who tried to re-open the direct communications between Central Asia and Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

. By 750, the Tibetans had lost almost all of their central Asian possessions to the Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

. However, after Gao Xianzhi's defeat by the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

and Qarluqs

The Karluks (also Qarluqs, Qarluks, Karluqs, otk, 𐰴𐰺𐰞𐰸, Qarluq, Para-Mongol: Harluut, zh, s=葛逻禄, t=葛邏祿 ''Géluólù'' ; customary phonetic: ''Gelu, Khololo, Khorlo'', fa, خَلُّخ, ''Khallokh'', ar, قارلوق ...

at the Battle of Talas

The Battle of Talas or Battle of Artlakh (; ar, معركة نهر طلاس, translit=Maʿrakat nahr Ṭalās, Persian: Nabard-i Tarāz) was a military encounter and engagement between the Abbasid Caliphate along with its ally, the Tibetan Empir ...

(751) and the subsequent civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

known as the An Lushan Rebellion

The An Lushan Rebellion was an uprising against the Tang dynasty of China towards the mid-point of the dynasty (from 755 to 763), with an attempt to replace it with the Yan dynasty. The rebellion was originally led by An Lushan, a general office ...

(755), Chinese influence decreased rapidly and Tibetan influence resumed.

At its height in the 780s to 790s, the Tibetan Empire reached its highest glory when it ruled and controlled a territory stretching from modern day Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Burma, China, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan.

In 821/822CE, Tibet and China signed a peace treaty. A bilingual account of this treaty, including details of the borders between the two countries, is inscribed on a stone pillar which stands outside the Jokhang

The Jokhang (, ), also known as the Qoikang Monastery, Jokang, Jokhang Temple, Jokhang Monastery and Zuglagkang ( or Tsuklakang), is a Buddhist temple in Barkhor Square in Lhasa, the capital city of Tibet Autonomous Region of China. Tibetans, in ...

temple in Lhasa. Tibet continued as a Central Asian empire until the mid-9th century, when a civil war over succession led to the collapse of imperial Tibet. The period that followed is known traditionally as the ''Era of Fragmentation

The Era of Fragmentation (; ) was an era of disunity in Tibetan history lasting from the death of the Tibetan Empire's last emperor, Langdarma, in 842 until Drogön Chögyal Phagpa became the Imperial Preceptor of the three provinces of Tibet ...

'', when political control over Tibet became divided between regional warlords and tribes with no dominant centralized authority. An Islamic invasion from Bengal took place in 1206.

Yuan dynasty

The Mongol

The Mongol Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fifth ...

, through the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs __NOTOC__

The Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs, or Xuanzheng Yuan () was a government agency of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China to handle Buddhist affairs across the empire in addition to managing the territory of Tibet. It was original ...

, or Xuanzheng Yuan, ruled Tibet through a top-level administrative department. One of the department's purposes was to select a ''dpon-chen

The ''dpon-chen'' or ''pönchen'' (), literally the "great authority" or "great administrator", was the chief administrator or governor of Tibet located at Sakya Monastery during the Yuan administrative rule of Tibet in the 13th and 14th centuries ...

'' ("great administrator"), usually appointed by the lama and confirmed by the Mongol emperor in Beijing.Dawa Norbu. China's Tibet Policy

'', p. 139. Psychology Press. The

Sakya

The ''Sakya'' (, 'pale earth') school is one of four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism, the others being the Nyingma, Kagyu, and Gelug. It is one of the Red Hat Orders along with the Nyingma and Kagyu.

Origins

Virūpa, 16th century. It depict ...

lama retained a degree of autonomy, acting as the political authority of the region, while the ''dpon-chen'' held administrative and military power. Mongol rule of Tibet remained separate from the main provinces of China, but the region existed under the administration of the Yuan dynasty. If the Sakya lama ever came into conflict with the ''dpon-chen'', the ''dpon-chen'' had the authority to send Chinese troops into the region.

Tibet retained nominal power over religious and regional political affairs, while the Mongols managed a structural and administrative rule over the region, reinforced by the rare military intervention. This existed as a "diarchic

Diarchy (from Greek , ''di-'', "double", and , ''-arkhía'', "ruled"),Occasionally misspelled ''dyarchy'', as in the ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' article on the colonial British institution duarchy, or duumvirate (from Latin ', "the office of ...

structure" under the Yuan emperor, with power primarily in favor of the Mongols. Mongolian prince Khuden gained temporal power in Tibet in the 1240s and sponsored Sakya Pandita

Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyeltsen (Tibetan: ས་སྐྱ་པཎ་ཌི་ཏ་ཀུན་དགའ་རྒྱལ་མཚན, ) (1182 – 28 November 1251) was a Tibetan spiritual leader and Buddhist scholar and the fourth of the Five Sa ...

, whose seat became the capital of Tibet. Drogön Chögyal Phagpa

Drogön Chogyal Phagpa (; ; 1235 – 15 December 1280), was the fifth leader of the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism. He was also the first Imperial Preceptor of the Yuan dynasty, and was concurrently named the director of the Bureau of Buddhist ...

, Sakya Pandita's nephew became Imperial Preceptor

The Imperial Preceptor, or Dishi (, lit. "Teacher of the Emperor") was a high title and powerful post created by Kublai Khan, founder of the Yuan dynasty. It was established as part of Mongol patronage of Tibetan Buddhism and the Yuan administra ...

of Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of th ...

, founder of the Yuan dynasty.

Yuan control over the region ended with the Ming overthrow of the Yuan and Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen (; )Chen Qingying (2003) (1302 – 21 November 1364) was the founder of the Phagmodrupa Dynasty that replaced the Mongol-backed Sakya dynasty, ending Tibet under Yuan rule. He ruled most of Tibet as ''desi'' (regent) from ...

's revolt against the Mongols.Rossabi 1983, p. 194 Following the uprising, Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen founded the Phagmodrupa Dynasty

The Phagmodrupa dynasty or Pagmodru (, ; ) was a dynastic regime that held sway over Tibet or parts thereof from 1354 to the early 17th century. It was established by Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen of the Lang () family at the end of the Yuan dynast ...

, and sought to reduce Yuan influences over Tibetan culture and politics.

Phagmodrupa, Rinpungpa and Tsangpa Dynasties

Between 1346 and 1354, Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen toppled the Sakya and founded the Phagmodrupa Dynasty. The following 80 years saw the founding of the

Between 1346 and 1354, Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen toppled the Sakya and founded the Phagmodrupa Dynasty. The following 80 years saw the founding of the Gelug

file:DalaiLama0054 tiny.jpg, 240px, 14th Dalai Lama, The 14th Dalai Lama (center), the most influential figure of the contemporary Gelug tradition, at the 2003 Kalachakra ceremony, Bodh Gaya, Bodhgaya (India).

The Gelug (, also Geluk; "virtuous ...

school (also known as Yellow Hats) by the disciples of Je Tsongkhapa

Tsongkhapa ('','' meaning: "the man from Tsongkha" or "the Man from Onion Valley", c. 1357–1419) was an influential Tibetan Buddhist monk, philosopher and tantric yogi, whose activities led to the formation of the Gelug school of Tibetan Budd ...

, and the founding of the important Ganden

Ganden Monastery (also Gaden or Gandain) or Ganden Namgyeling or Monastery of Gahlden is one of the "great three" Gelug university monasteries of Tibet. It is in Dagzê County, Lhasa. The other two are Sera Monastery and Drepung Monastery. Gand ...

, Drepung

Drepung Monastery (, "Rice Heap Monastery"), located at the foot of Mount Gephel, is one of the "great three" Gelug university gompas (monasteries) of Tibet. The other two are Ganden Monastery and Sera Monastery.

Drepung is the largest of all ...

and Sera monasteries near Lhasa. However, internal strife within the dynasty and the strong localism of the various fiefs and political-religious factions led to a long series of internal conflicts. The minister family Rinpungpa

Rinpungpa (; ) was a Tibetan dynastic regime that dominated much of Western Tibet and part of Ü-Tsang between 1435 and 1565. During one period around 1500 the Rinpungpa lords came close to assemble the Tibetan lands around the Yarlung Tsangpo R ...

, based in Tsang (West Central Tibet), dominated politics after 1435. In 1565 they were overthrown by the Tsangpa

Tsangpa (; ) was a dynasty that dominated large parts of Tibet from 1565 to 1642. It was the last Tibetan royal dynasty to rule in their own name. The regime was founded by Karma Tseten, a low-born retainer of the prince of the Rinpungpa Dynasty ...

Dynasty of Shigatse

Shigatse, officially known as Xigazê (; Nepali: ''सिगात्से''), is a prefecture-level city of the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. Its area of jurisdiction, with an area of , corresponds to the histor ...

which expanded its power in different directions of Tibet in the following decades and favoured the Karma Kagyu

Karma Kagyu (), or Kamtsang Kagyu (), is a widely practiced and probably the second-largest lineage within the Kagyu school, one of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The lineage has long-standing monasteries in Tibet, China, Russia, Mon ...

sect.

Rise of Ganden Phodrang

In 1578,Altan Khan

Altan Khan of the Tümed (1507–1582; mn, ᠠᠯᠲᠠᠨ ᠬᠠᠨ, Алтан хан; Chinese language, Chinese: 阿勒坦汗), whose given name was Anda (Mongolian language, Mongolian: ; Chinese language, Chinese: 俺答), was the leader of ...

of the Tümed

The Tümed (Tumad, ; "The many or ten thousands" derived from Tumen) are a Mongol subgroup. They live in Tumed Left Banner, district of Hohhot and Tumed Right Banner, district of Baotou in China. Most engage in sedentary agriculture, living in mi ...

Mongols gave Sonam Gyatso, a high lama of the Gelugpa school, the name ''Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama (, ; ) is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and current Dal ...

'', ''Dalai'' being the Mongolian translation of the Tibetan name ''Gyatso'' "Ocean".

Unified heartland under Buddhist Gelug school

The5th Dalai Lama

Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (; ; 1617–1682) was the 5th Dalai Lama and the first Dalai Lama to wield effective temporal and spiritual power over all Tibet. He is often referred to simply as the Great Fifth, being a key religious and temporal leader ...

(1617-1682) is known for unifying the Tibetan heartland under the control of the Gelug

file:DalaiLama0054 tiny.jpg, 240px, 14th Dalai Lama, The 14th Dalai Lama (center), the most influential figure of the contemporary Gelug tradition, at the 2003 Kalachakra ceremony, Bodh Gaya, Bodhgaya (India).

The Gelug (, also Geluk; "virtuous ...

school of Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism (also referred to as Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Lamaism, Lamaistic Buddhism, Himalayan Buddhism, and Northern Buddhism) is the form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Bhutan, where it is the dominant religion. It is also in majo ...

, after defeating the rival Kagyu

The ''Kagyu'' school, also transliterated as ''Kagyü'', or ''Kagyud'' (), which translates to "Oral Lineage" or "Whispered Transmission" school, is one of the main schools (''chos lugs'') of Tibetan (or Himalayan) Buddhism. The Kagyu lineag ...

and Jonang

The Jonang () is one of the schools of Tibetan Buddhism. Its origins in Tibet can be traced to early 12th century master Yumo Mikyo Dorje, but became much wider known with the help of Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen, a monk originally trained in the ...

sects and the secular ruler, the Tsangpa

Tsangpa (; ) was a dynasty that dominated large parts of Tibet from 1565 to 1642. It was the last Tibetan royal dynasty to rule in their own name. The regime was founded by Karma Tseten, a low-born retainer of the prince of the Rinpungpa Dynasty ...

prince, in a prolonged civil war. His efforts were successful in part because of aid from Güshi Khan

Güshi Khan (1582 – 14 January 1655; ) was a Khoshut prince and founder of the Khoshut Khanate, who supplanted the Tumed descendants of Altan Khan as the main benefactor of the Dalai Lama and the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. In 1637, Güsh ...

, the Oirat leader of the Khoshut Khanate

The Khoshut Khanate was a Mongol Oirat khanate based on the Tibetan Plateau from 1642 to 1717. Based in modern Qinghai, it was founded by Güshi Khan in 1642 after defeating the opponents of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibet. The ...

. With Güshi Khan as a largely uninvolved overlord, the 5th Dalai Lama and his intimates established a civil administration which is referred to by historians as the ''Lhasa state''. This Tibetan regime or government is also referred to as the Ganden Phodrang

The Ganden Phodrang or Ganden Podrang (; ) was the Tibetan system of government established by the 5th Dalai Lama in 1642; it operated in Tibet until the 1950s. Lhasa became the capital of Tibet again early in this period, after the Oirat lo ...

.

Qing dynasty

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

rule in Tibet began with their 1720 expedition to the country when they expelled the invading Dzungars

The Dzungar people (also written as Zunghar; from the Mongolian words , meaning 'left hand') were the many Mongol Oirat tribes who formed and maintained the Dzungar Khanate in the 17th and 18th centuries. Historically they were one of major tr ...

. Amdo

Amdo ( �am˥˥.to˥˥ ) is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being U-Tsang in the west and Kham in the east. Ngari (including former Guge kingdom) in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Amdo is also the bi ...

came under Qing control in 1724, and eastern Kham

Kham (; )

is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being Amdo in the northeast, and Ü-Tsang in central Tibet. The original residents of Kham are called Khampas (), and were governed locally by chieftains and monasteries. Kham ...

was incorporated into neighbouring Chinese provinces in 1728.Wang Jiawei, "The Historical Status of China's Tibet

''The Historical Status of China's Tibet'' is a book published in 1997 in English by China Intercontinental Press, the propaganda press for the government of the People's Republic of China. The book presents the Chinese government's official posi ...

", 2000, pp. 162–6. Meanwhile, the Qing government sent resident commissioners called ''Amban

Amban (Manchu language, Manchu and Mongolian language, Mongol: ''Amban'', Standard Tibetan, Tibetan: ་''am ben'', , Uyghur language, Uighur:''am ben'') is a Manchu language term meaning "high official", corresponding to a number of different ...

s'' to Lhasa. In 1750, the Ambans and the majority of the Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive va ...

and Manchus

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and Q ...

living in Lhasa were killed in a riot, and Qing troops arrived quickly and suppressed the rebels in the next year. Like the preceding Yuan dynasty, the Manchus of the Qing dynasty exerted military and administrative control of the region, while granting it a degree of political autonomy. The Qing commander publicly executed a number of supporters of the rebels and, as in 1723 and 1728, made changes in the political structure and drew up a formal organization plan. The Qing now restored the Dalai Lama as ruler, leading the governing council called ''Kashag

The Kashag (; ), was the governing council of Tibet during the rule of the Qing dynasty and post-Qing period until the 1950s. It was created in 1721, and set by Qianlong Emperor in 1751 for the Ganden Phodrang in the 13-Article Ordinance for ...

'', but elevated the role of ''Ambans'' to include more direct involvement in Tibetan internal affairs. At the same time, the Qing took steps to counterbalance the power of the aristocracy by adding officials recruited from the clergy to key posts.

For several decades, peace reigned in Tibet, but in 1792, the Qing Qianlong Emperor

The Qianlong Emperor (25 September 17117 February 1799), also known by his temple name Emperor Gaozong of Qing, born Hongli, was the fifth Emperor of the Qing dynasty and the fourth Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1735 t ...

sent a large Chinese army into Tibet to push the invading Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

ese out. This prompted yet another Qing reorganization of the Tibetan government, this time through a written plan called the "Twenty-Nine Regulations for Better Government in Tibet". Qing military garrisons staffed with Qing troops were now also established near the Nepalese border. Tibet was dominated by the Manchus in various stages in the 18th century, and the years immediately following the 1792 regulations were the peak of the Qing imperial commissioners' authority; but there was no attempt to make Tibet a Chinese province.

In 1834, the Sikh Empire

The Sikh Empire was a state originating in the Indian subcontinent, formed under the leadership of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who established an empire based in the Punjab. The empire existed from 1799, when Maharaja Ranjit Singh captured Lahor ...

invaded and annexed Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory which constitutes a part of the larger Kashmir region and has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since 1947. (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu and ...

, a culturally Tibetan region that was an independent kingdom at the time. Seven years later, a Sikh army led by General Zorawar Singh

Zorawar Singh (1784–12 December 1841) was a military general of the Dogra Rajput ruler, Gulab Singh of Jammu. He served as the governor (''wazir-e-wazarat'') of Kishtwar and extended the territories of the kingdom by conquering Ladakh and B ...

invaded western Tibet from Ladakh, starting the Sino-Sikh War. A Qing-Tibetan army repelled the invaders but was in turn defeated when it chased the Sikhs into Ladakh. The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Chushul

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

between the Chinese and Sikh empires.

As the Qing dynasty weakened, its authority over Tibet also gradually declined, and by the mid-19th century, its influence was minuscule. Qing authority over Tibet had become more symbolic than real by the late 19th century, although in the 1860s, the Tibetans still chose for reasons of their own to emphasize the empire's symbolic authority and make it seem substantial.

In 1774, a Scottish

As the Qing dynasty weakened, its authority over Tibet also gradually declined, and by the mid-19th century, its influence was minuscule. Qing authority over Tibet had become more symbolic than real by the late 19th century, although in the 1860s, the Tibetans still chose for reasons of their own to emphasize the empire's symbolic authority and make it seem substantial.

In 1774, a Scottish nobleman

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristi ...

, George Bogle, travelled to Shigatse

Shigatse, officially known as Xigazê (; Nepali: ''सिगात्से''), is a prefecture-level city of the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. Its area of jurisdiction, with an area of , corresponds to the histor ...

to investigate prospects of trade for the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

. His efforts, while largely unsuccessful, established permanent contact between Tibet and the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and state (polity), states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

. However, in the 19th century, tensions between foreign powers and Tibet increased. The British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

was expanding its territories in India into the Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

, while the Emirate of Afghanistan

The Emirate of Afghanistan also referred to as the Emirate of Kabul (until 1855) ) was an emirate between Central Asia and South Asia that is now today's Afghanistan and some parts of today's Pakistan (before 1893). The emirate emerged from th ...

and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

were both doing likewise in Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

.

In 1904, a British expedition to Tibet

The British expedition to Tibet, also known as the Younghusband expedition, began in December 1903 and lasted until September 1904. The expedition was effectively a temporary invasion by British Indian Armed Forces under the auspices of the ...

, spurred in part by a fear that Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

was extending its power into Tibet as part of the Great Game

The Great Game is the name for a set of political, diplomatic and military confrontations that occurred through most of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century – involving the rivalry of the British Empire and the Russian Empi ...

, was launched. Although the expedition initially set out with the stated purpose of resolving border disputes between Tibet and Sikkim

Sikkim (; ) is a state in Northeastern India. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Province No. 1 of Nepal in the west and West Bengal in the south. Sikkim is also close to the Siligur ...

, it quickly turned into a military invasion. The British expeditionary force, consisting of mostly Indian troops, quickly invaded and captured Lhasa, with the Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama (, ; ) is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and current Dal ...

fleeing to the countryside.Smith 1996, pp. 154–6 Afterwards, the leader of the expedition, Sir Francis Younghusband, negotiated the Convention Between Great Britain and Tibet

The Convention of Lhasa,

officially the Convention Between Great Britain and Thibet, was a treaty signed in 1904 between Tibet and Great Britain, in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet. It was signed following the British expedition to Tibet of 1903–1 ...

with the Tibetans, which guaranteed the British great economic influence but ensured the region remained under Chinese control. The Qing imperial resident, known as the Amban

Amban (Manchu language, Manchu and Mongolian language, Mongol: ''Amban'', Standard Tibetan, Tibetan: ་''am ben'', , Uyghur language, Uighur:''am ben'') is a Manchu language term meaning "high official", corresponding to a number of different ...

, publicly repudiated the treaty, while the British government, eager for friendly relations with China, negotiated a new treaty two years later known as the Convention Between Great Britain and China Respecting Tibet

The Convention Between Great Britain and China Respecting Tibet () was a treaty signed between the Qing dynasty and the British Empire in 1906, as a follow-on to the 1904 Convention of Lhasa between the British Empire and Tibet. It reaffirmed the ...

. The British agreed not to annex or interfere in Tibet in return for an indemnity from the Chinese government, while China agreed not to permit any other foreign state to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet.

In 1910, the Qing government sent a military expedition of its own under Zhao Erfeng

Zhao Erfeng (1845–1911), courtesy name Jihe, was a late Qing Dynasty official and Han Chinese bannerman, who belonged to the Plain Blue Banner. He was an assistant amban in Tibet at Chamdo in Kham (eastern Tibet). He was appointed in March, ...

to establish direct Manchu-Chinese rule and, in an imperial edict, deposed the Dalai Lama, who fled to British India. Zhao Erfeng defeated the Tibetan military conclusively and expelled the Dalai Lama's forces from the province. His actions were unpopular, and there was much animosity against him for his mistreatment of civilians and disregard for local culture.

Post-Qing period

After the

After the Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of a d ...

(1911–12) toppled the Qing dynasty and the last Qing troops were escorted out of Tibet, the new Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

apologized for the actions of the Qing and offered to restore the Dalai Lama's title. The Dalai Lama refused any Chinese title and declared himself ruler of an independent Tibet.Shakya 1999, pg. 5 In 1913, Tibet and Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

concluded a treaty of mutual recognition. For the next 36 years, the 13th Dalai Lama and the regents who succeeded him governed Tibet. During this time, Tibet fought Chinese warlords for control of the ethnically Tibetan areas in Xikang

Xikang (also Sikang or Hsikang) was a nominal province

formed by the Republic of China in 1939 on the initiative of prominent Sichuan warlord Liu Wenhui and continued by the early People's Republic of China. Thei idea was to form a single unifi ...

and Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

(parts of Kham and Amdo) along the upper reaches of the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest list of rivers of Asia, river in Asia, the list of rivers by length, third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in th ...

.Wang Jiawei, "The Historical Status of China's Tibet", 2000, p. 150. In 1914, the Tibetan government signed the Simla Convention

The Simla Convention, officially the Convention Between Great Britain, China, and Tibet,

with Britain, which recognized Chinese suzerainty over Tibet in return for a border settlement. China refused to sign the Convention and lost its suzerain rights. When in the 1930s and 1940s the regents displayed negligence in affairs, the Kuomintang Government of the Republic of China took advantage of this to expand its reach into the territory. On December 20, 1941, Kuomingtang leader

Emerging with control over most of

Emerging with control over most of

All of modern China, including Tibet, is considered a part of East Asia. Historically, some European sources also considered parts of Tibet to lie in

All of modern China, including Tibet, is considered a part of East Asia. Historically, some European sources also considered parts of Tibet to lie in

Tibet has some of the world's tallest mountains, with several of them making the top ten list.

Tibet has some of the world's tallest mountains, with several of them making the top ten list.  The Indus and Brahmaputra rivers originate from the vicinities of Lake Mapam Yumco in Western Tibet, near

The Indus and Brahmaputra rivers originate from the vicinities of Lake Mapam Yumco in Western Tibet, near

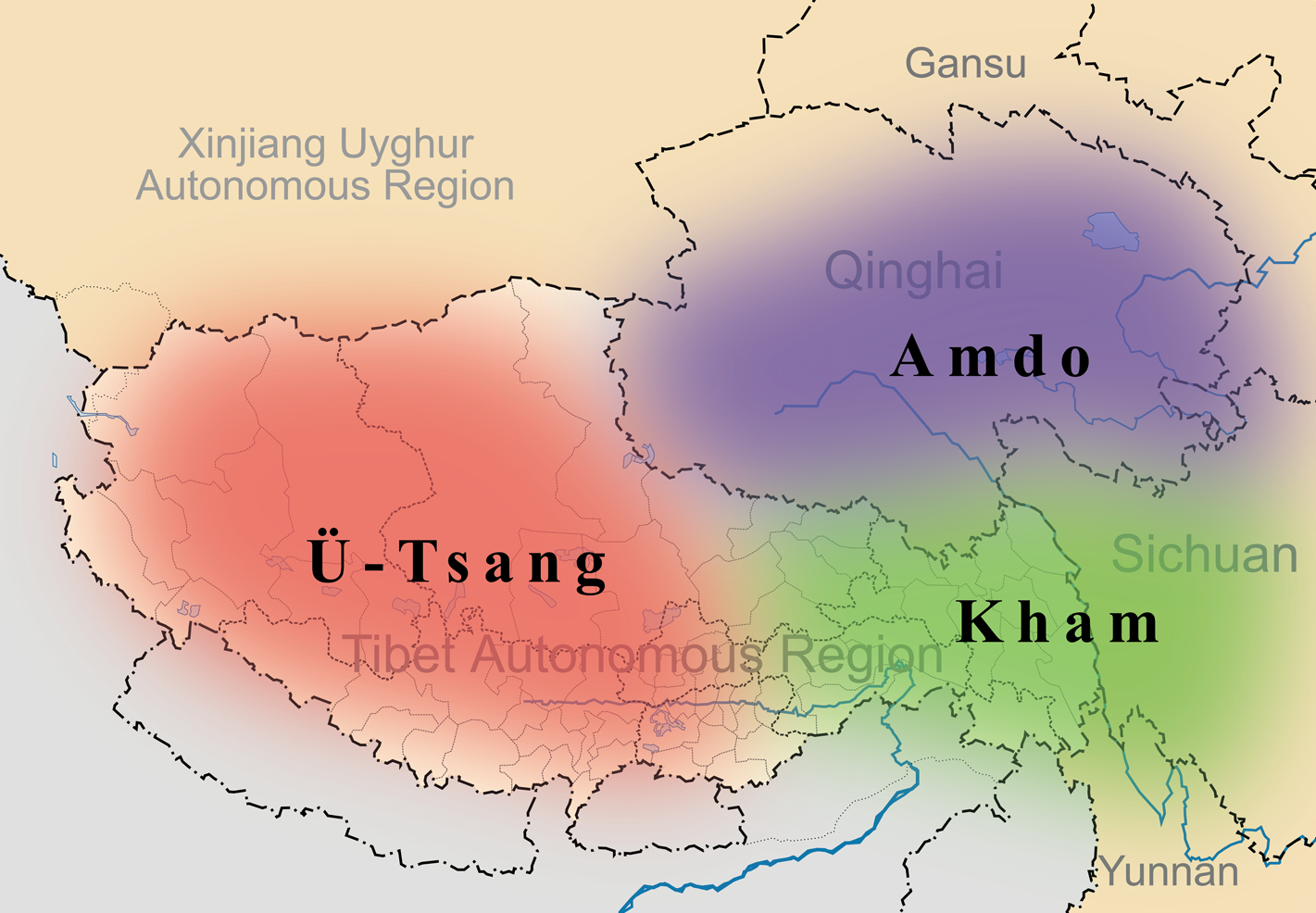

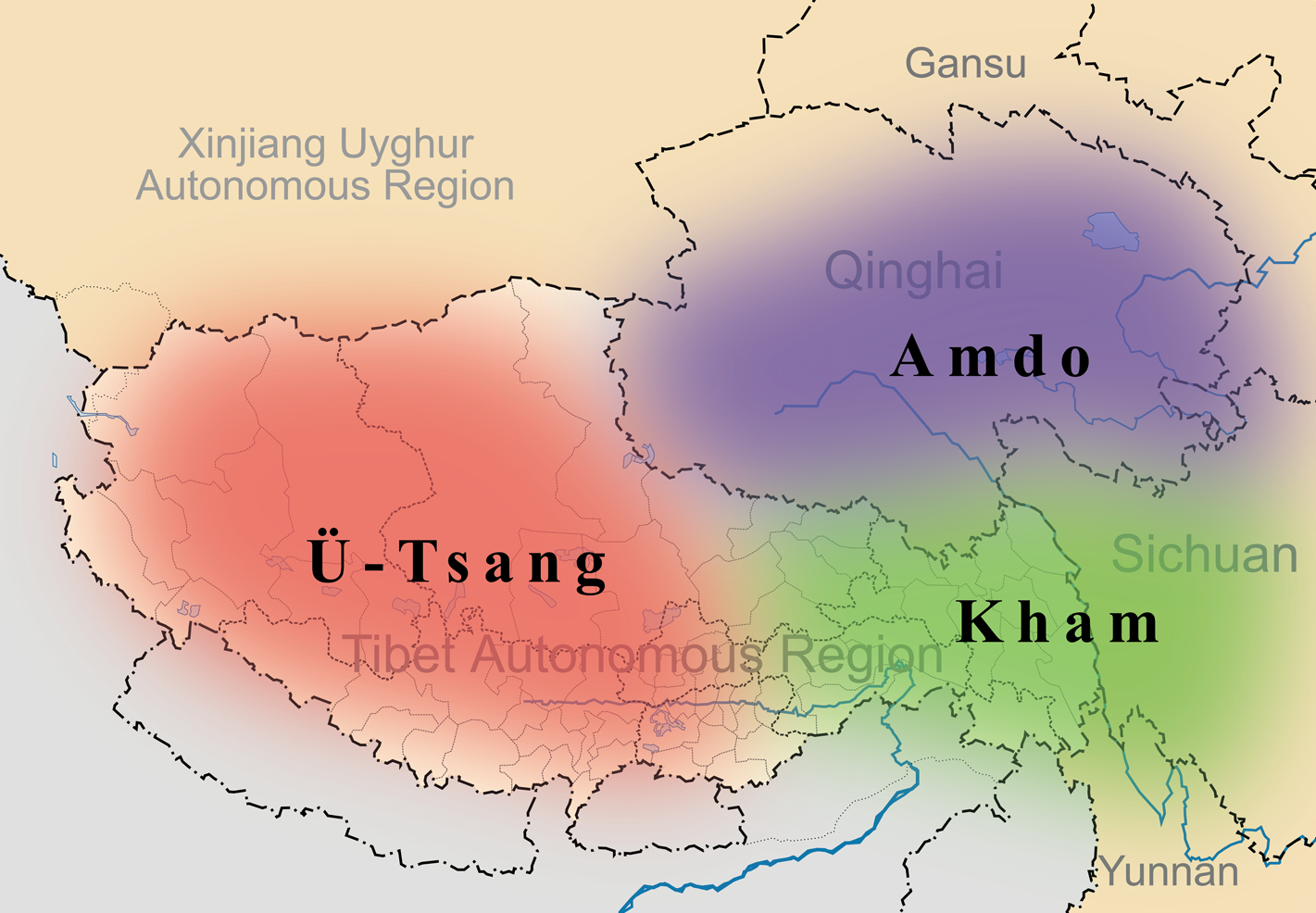

Cultural Tibet consists of several regions. These include Amdo (''A mdo'') in the northeast, which is administratively part of the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu, and Sichuan. Kham (''Khams'') in the southeast encompasses parts of western Sichuan, northern

Cultural Tibet consists of several regions. These include Amdo (''A mdo'') in the northeast, which is administratively part of the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu, and Sichuan. Kham (''Khams'') in the southeast encompasses parts of western Sichuan, northern

The Tibetan economy is dominated by

The Tibetan economy is dominated by  Forty percent of the rural cash income in the Tibet Autonomous Region is derived from the harvesting of the fungus ''

Forty percent of the rural cash income in the Tibet Autonomous Region is derived from the harvesting of the fungus '' The Qingzang railway linking the

The Qingzang railway linking the

Historically, the population of Tibet consisted of primarily ethnic

Historically, the population of Tibet consisted of primarily ethnic

Religion is extremely important to the Tibetans and has a strong influence over all aspects of their lives.

Religion is extremely important to the Tibetans and has a strong influence over all aspects of their lives.

. BBC News. March 20, 2008. A few monasteries have begun to rebuild since the 1980s (with limited support from the Chinese government) and greater religious freedom has been granted – although it is still limited. Monks returned to monasteries across Tibet and monastic education resumed even though the number of monks imposed is strictly limited. Before the 1950s, between 10 and 20% of males in Tibet were monks. Tibetan Buddhism has five main traditions (the suffix ''pa'' is comparable to "er" in English): * Gelug(pa), ''Way of Virtue'', also known casually as ''Yellow Hat'', whose spiritual head is the

Muslims have been living in Tibet since as early as the 8th or 9th century. In Tibetan cities, there are small communities of Tibetan Muslim, Muslims, known as Kachee (Kache), who trace their origin to immigrants from three main regions:

Muslims have been living in Tibet since as early as the 8th or 9th century. In Tibetan cities, there are small communities of Tibetan Muslim, Muslims, known as Kachee (Kache), who trace their origin to immigrants from three main regions:

File:thanka.jpg, A thangka painting in

Tibet has various festivals, many for worshipping the Buddha, that take place throughout the year. Losar is the Tibetan New Year Festival. Preparations for the festive event are manifested by special offerings to family shrine deities, painted doors with religious symbols, and other painstaking jobs done to prepare for the event. Tibetans eat ''Guthuk'' (barley noodle soup with filling) on New Year's Eve with their families. The Monlam Prayer Festival follows it in the first month of the Tibetan calendar, falling between the fourth and the eleventh days of the first Tibetan month. It involves dancing and participating in sports events, as well as sharing picnics. The event was established in 1049 by Tsong Khapa, the founder of the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama's order.

Tibet has various festivals, many for worshipping the Buddha, that take place throughout the year. Losar is the Tibetan New Year Festival. Preparations for the festive event are manifested by special offerings to family shrine deities, painted doors with religious symbols, and other painstaking jobs done to prepare for the event. Tibetans eat ''Guthuk'' (barley noodle soup with filling) on New Year's Eve with their families. The Monlam Prayer Festival follows it in the first month of the Tibetan calendar, falling between the fourth and the eleventh days of the first Tibetan month. It involves dancing and participating in sports events, as well as sharing picnics. The event was established in 1049 by Tsong Khapa, the founder of the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama's order.

A History of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State