Platelets, also called thrombocytes (from

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

θρόμβος, "clot" and κύτος, "cell"), are a component of

blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the c ...

whose function (along with the

coagulation factors

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism o ...

) is to react to

bleeding

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

from

blood vessel

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport blood throughout the human body. These vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to the tissues of the body. They also take waste and carbon dioxide away ...

injury by clumping, thereby initiating a

blood clot

A thrombus (plural thrombi), colloquially called a blood clot, is the final product of the blood coagulation step in hemostasis. There are two components to a thrombus: aggregated platelets and red blood cells that form a plug, and a mesh of c ...

. Platelets have no

cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (pl. nuclei; from Latin or , meaning ''kernel'' or ''seed'') is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryotic cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, h ...

; they are fragments of

cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

that are derived from the

megakaryocyte

A megakaryocyte (''mega-'' + '' karyo-'' + '' -cyte'', "large-nucleus cell") is a large bone marrow cell with a lobated nucleus responsible for the production of blood thrombocytes (platelets), which are necessary for normal blood clotting. In hum ...

s of the

bone marrow

Bone marrow is a semi-solid tissue found within the spongy (also known as cancellous) portions of bones. In birds and mammals, bone marrow is the primary site of new blood cell production (or haematopoiesis). It is composed of hematopoietic ce ...

or lung, which then enter the circulation. Platelets are found only in mammals, whereas in other

vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

s (e.g.

bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

s,

amphibian

Amphibians are tetrapod, four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the Class (biology), class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terres ...

s), thrombocytes circulate as intact

mononuclear cell

In immunology, agranulocytes (also known as nongranulocytes or mononuclear leukocytes) are one of the two types of leukocytes (white blood cells), the other type being granulocytes. Agranular cells are noted by the absence of Granule (cell biol ...

s.

[

] One major function of platelets is to contribute to

One major function of platelets is to contribute to hemostasis

In biology, hemostasis or haemostasis is a process to prevent and stop bleeding, meaning to keep blood within a damaged blood vessel (the opposite of hemostasis is hemorrhage). It is the first stage of wound healing. This involves coagulation, whi ...

: the process of stopping bleeding at the site of interrupted endothelium

The endothelium is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the rest of the vessel ...

. They gather at the site and, unless the interruption is physically too large, they plug the hole. First, platelets attach to substances outside the interrupted endothelium: ''adhesion

Adhesion is the tendency of dissimilar particles or surfaces to cling to one another ( cohesion refers to the tendency of similar or identical particles/surfaces to cling to one another).

The forces that cause adhesion and cohesion can be ...

''. Second, they change shape, turn on receptors and secrete chemical messengers: ''activation''. Third, they connect to each other through receptor bridges: ''aggregation''.platelet plug

The platelet plug, also known as the hemostatic plug or platelet thrombus, is an aggregation of platelets formed during early stages of hemostasis in response to one or more injuries to blood vessel walls. After platelets are recruited and begi ...

(primary hemostasis) is associated with activation of the coagulation cascade

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism o ...

, with resultant fibrin

Fibrin (also called Factor Ia) is a fibrous, non-globular protein involved in the clotting of blood. It is formed by the action of the protease thrombin on fibrinogen, which causes it to polymerize. The polymerized fibrin, together with platele ...

deposition and linking (secondary hemostasis). These processes may overlap: the spectrum is from a predominantly platelet plug, or "white clot" to a predominantly fibrin, or "red clot" or the more typical mixture. Some would add the subsequent ''retraction'' and ''platelet inhibition

Platelets, also called thrombocytes (from Greek θρόμβος, "clot" and κύτος, "cell"), are a component of blood whose function (along with the coagulation factors) is to react to bleeding from blood vessel injury by clumping, thereby ini ...

'' as fourth and fifth steps to the completion of the process and still others would add a sixth step, ''wound repair''. Platelets also participate in both innate

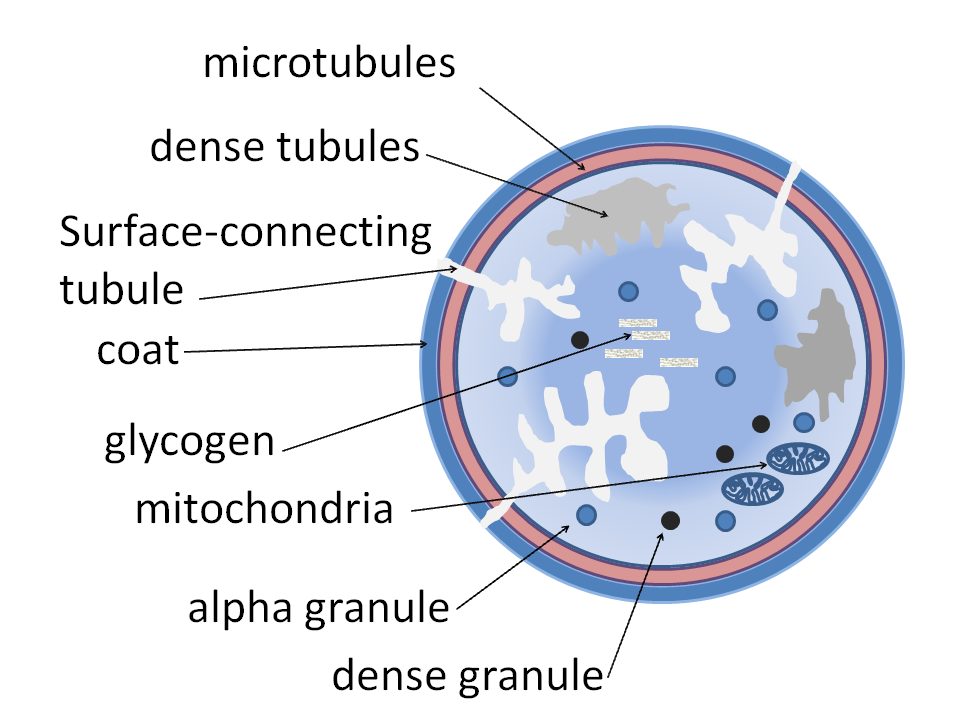

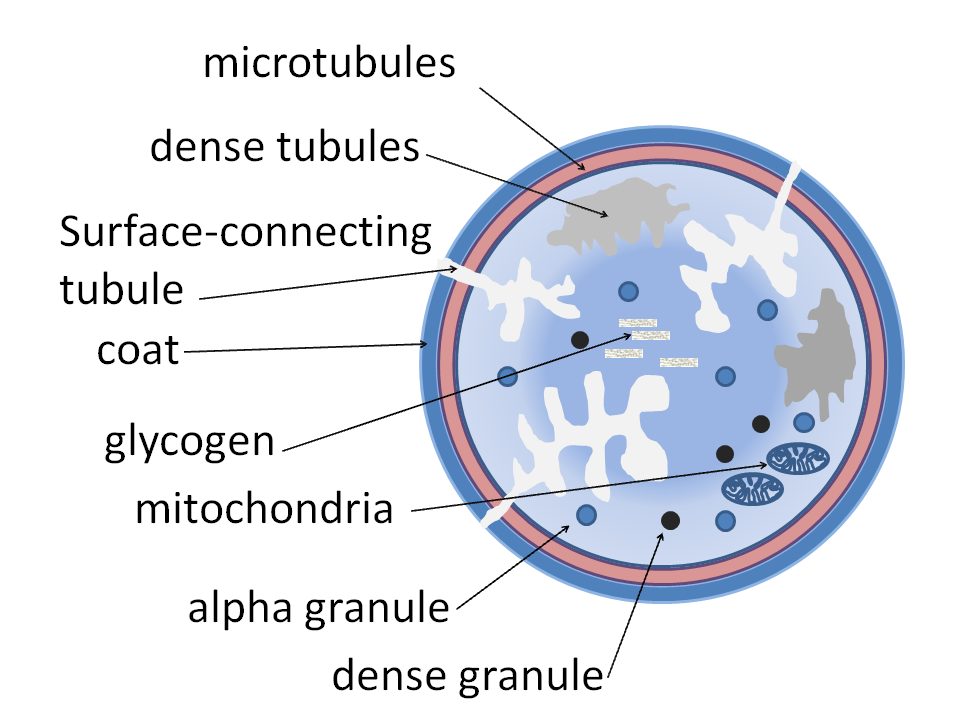

Structure

Structure

Structurally the platelet can be divided into four zones, from peripheral to innermost:

* Peripheral zone – is rich in glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glycos ...

s required for platelet adhesion, activation and aggregation. For example, GPIb/IX/V; GPVI

Glycoprotein VI (platelet), also known as GPVI, is a glycoprotein receptor for collagen which is expressed in platelets. In humans, glycoprotein VI is encoded by the ''GPVI'' gene.

GPVI was first cloned in 2000 by several groups including that ...

; GPIIb/IIIa

In medicine, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa, also known as integrin αIIbβ3) is an integrin complex found on platelets. It is a receptor for fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor and aids platelet activation. The complex is formed via calcium ...

.

* Sol-gel zone – is rich in microtubules

Microtubules are polymers of tubulin that form part of the cytoskeleton and provide structure and shape to eukaryotic cells. Microtubules can be as long as 50 micrometres, as wide as 23 to 27 nm and have an inner diameter between 11 an ...

and microfilament

Microfilaments, also called actin filaments, are protein filaments in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells that form part of the cytoskeleton. They are primarily composed of polymers of actin, but are modified by and interact with numerous other pr ...

s, allowing the platelets to maintain their discoid shape.

* Organelle zone – is rich in platelet granules. Alpha granule

Alpha granules, (α-granules) also known as platelet alpha-granules are a cellular component of platelets. Platelets contain different types of granules that perform different functions, and include alpha granules, dense granules, and lysosomes. ...

s contain clotting mediators such as factor V

Factor V (pronounced factor five) is a protein of the coagulation system, rarely referred to as proaccelerin or labile factor. In contrast to most other coagulation factors, it is not enzymatically active but functions as a cofactor. Deficienc ...

, factor VIII

Factor VIII (FVIII) is an essential blood-clotting protein, also known as anti-hemophilic factor (AHF). In humans, factor VIII is encoded by the ''F8'' gene. Defects in this gene result in hemophilia A, a recessive X-linked coagulation disorder. ...

, fibrinogen

Fibrinogen (factor I) is a glycoprotein complex, produced in the liver, that circulates in the blood of all vertebrates. During tissue and vascular injury, it is converted enzymatically by thrombin to fibrin and then to a fibrin-based blood clo ...

, fibronectin

Fibronectin is a high- molecular weight (~500-~600 kDa) glycoprotein of the extracellular matrix that binds to membrane-spanning receptor proteins called integrins. Fibronectin also binds to other extracellular matrix proteins such as collage ...

, platelet-derived growth factor, and chemotactic agents. Delta granules, or dense bodies, contain ADP, calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to ...

and serotonin

Serotonin () or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is a monoamine neurotransmitter. Its biological function is complex and multifaceted, modulating mood, cognition, reward, learning, memory, and numerous physiological processes such as vomiting and vas ...

, which are platelet-activating mediators.

* Membranous zone – contains membranes derived from megakaryocyte

A megakaryocyte (''mega-'' + '' karyo-'' + '' -cyte'', "large-nucleus cell") is a large bone marrow cell with a lobated nucleus responsible for the production of blood thrombocytes (platelets), which are necessary for normal blood clotting. In hum ...

smooth endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

organized into a dense tubular system which is responsible for thromboxane A2

Thromboxane A2 (TXA2) is a type of thromboxane that is produced by activated platelets during hemostasis and has prothrombotic properties: it stimulates activation of new platelets as well as increases platelet aggregation. This is achieved by act ...

synthesis. This dense tubular system is connected to the surface platelet membrane to aid thromboxane A2 release.

Shape

Circulating inactivated platelets are biconvex discoid (lens-shaped) structures,

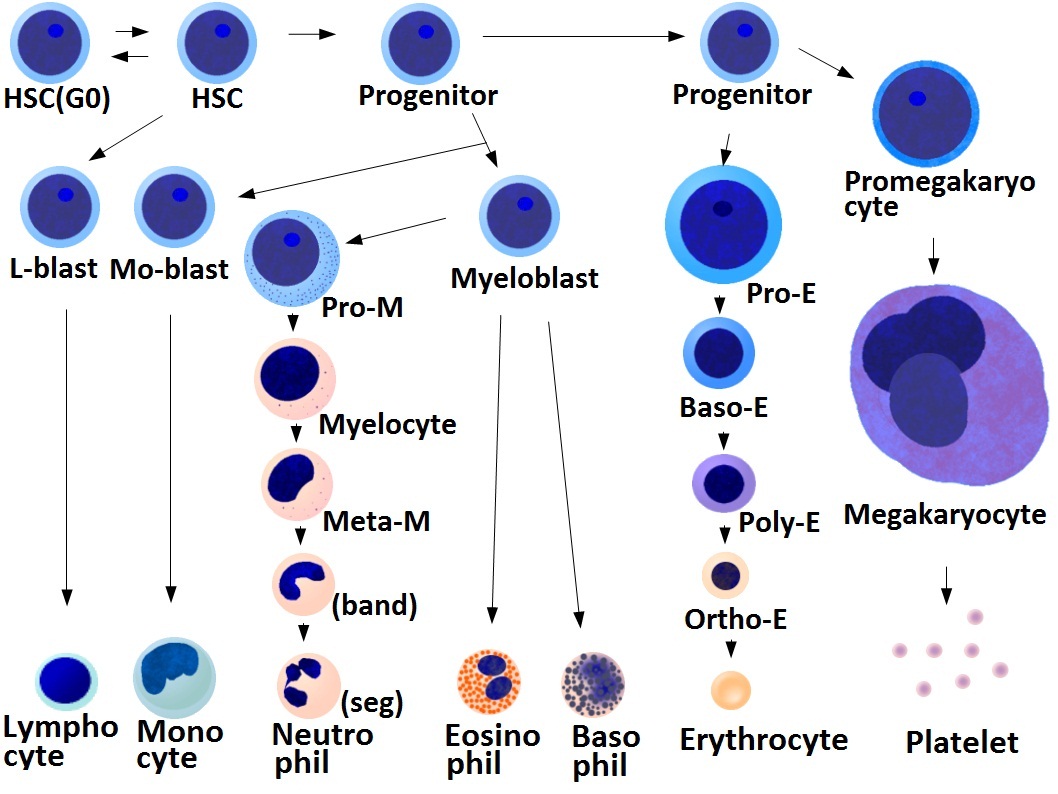

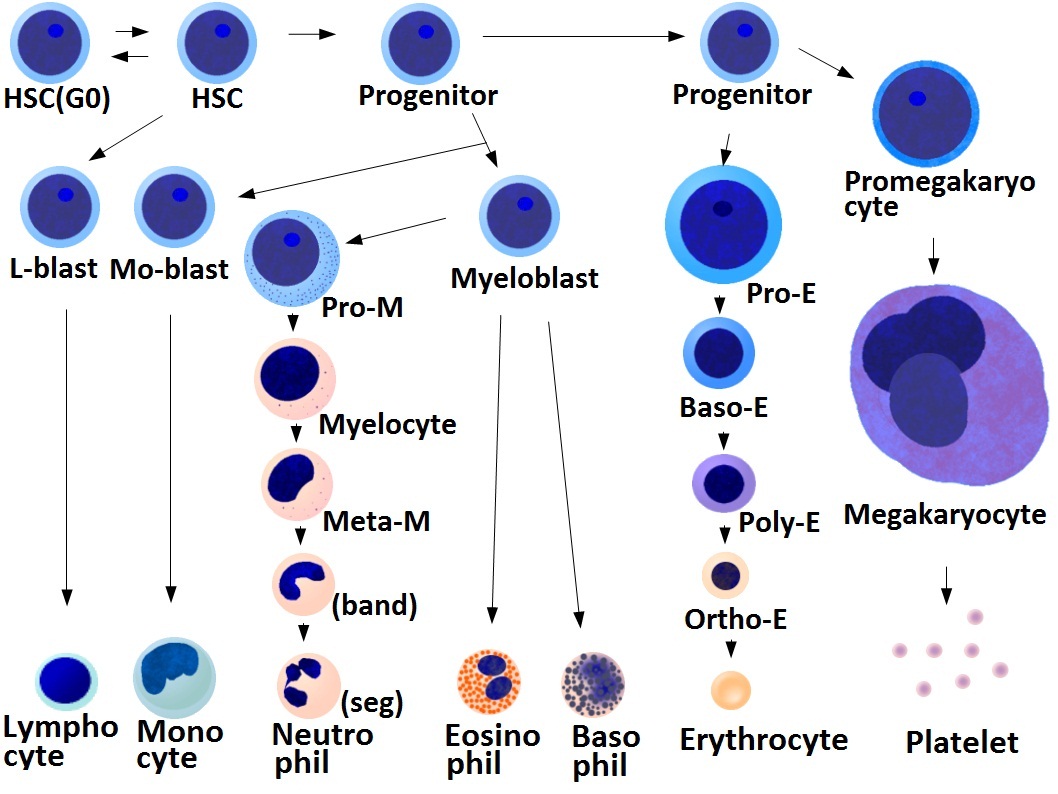

Development

* Megakaryocyte and platelet production is regulated by

* Megakaryocyte and platelet production is regulated by thrombopoietin

Thrombopoietin (THPO) also known as megakaryocyte growth and development factor (MGDF) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''THPO'' gene.

Thrombopoietin is a glycoprotein hormone produced by the liver and kidney which regulates the pro ...

, a hormone produced in the kidneys and liver.

* Each megakaryocyte produces between 1,000 and 3,000 platelets during its lifetime.

* An average of 1011 platelets are produced daily in a healthy adult.

* Reserve platelets are stored in the spleen and are released when needed by splenic contraction induced by the sympathetic nervous system.

* The average life span of circulating platelets is 8 to 9 days. Life span of individual platelets is controlled by the internal apoptotic regulating pathway, which has a Bcl-xL timer.

* Old platelets are destroyed by

* The average life span of circulating platelets is 8 to 9 days. Life span of individual platelets is controlled by the internal apoptotic regulating pathway, which has a Bcl-xL timer.

* Old platelets are destroyed by phagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis is ...

in the spleen and liver.

Hemostasis

The fundamental function of platelets is to clump together to stop acute bleeding. This process is complex, as more than 193 proteins and 301 interactions are known to be involved in platelet dynamics.

The fundamental function of platelets is to clump together to stop acute bleeding. This process is complex, as more than 193 proteins and 301 interactions are known to be involved in platelet dynamics.

Adhesion

Thrombus

A thrombus (plural thrombi), colloquially called a blood clot, is the final product of the blood coagulation step in hemostasis. There are two components to a thrombus: aggregated platelets and red blood cells that form a plug, and a mesh of c ...

formation on an intact endothelium

The endothelium is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the rest of the vessel ...

is prevented by nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes denoted by a dot in its che ...

, prostacyclin

Prostacyclin (also called prostaglandin I2 or PGI2) is a prostaglandin member of the eicosanoid family of lipid molecules. It inhibits platelet activation and is also an effective vasodilator.

When used as a drug, it is also known as epoprosteno ...

,Endothelial cells

The endothelium is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the rest of the vessel ...

are attached to the subendothelial collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix found in the body's various connective tissues. As the main component of connective tissue, it is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up from 25% to 35% of the whole ...

by von Willebrand factor

Von Willebrand factor (VWF) () is a blood glycoprotein involved in hemostasis, specifically, platelet adhesion. It is deficient and/or defective in von Willebrand disease and is involved in many other diseases, including thrombotic thrombocytopen ...

(VWF), which these cells produce. VWF is also stored in the Weibel-Palade bodies of the endothelial cells and secreted constitutively into the blood. Platelets store vWF in their alpha granules.

When the endothelial layer is disrupted, collagen and VWF anchor platelets to the subendothelium. Platelet GP1b-IX-V receptor binds with VWF; and GPVI receptor and integrin α2β1 bind with collagen.

Activation

Inhibition

The intact endothelial lining ''inhibits'' platelet activation by producing nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes denoted by a dot in its che ...

, endothelial- ADPase, and PGI2 (prostacyclin). Endothelial-ADPase degrades the platelet activator ADP.

Resting platelets maintain active calcium efflux via a cyclic AMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP, cyclic AMP, or 3',5'-cyclic adenosine monophosphate) is a second messenger important in many biological processes. cAMP is a derivative of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and used for intracellular signal transd ...

-activated calcium pump. Intracellular calcium concentration determines platelet activation status, as it is the second messenger

Second messengers are intracellular signaling molecules released by the cell in response to exposure to extracellular signaling molecules—the first messengers. (Intercellular signals, a non-local form or cell signaling, encompassing both first me ...

that drives platelet conformational change and degranulation (see below). Endothelial prostacyclin

Prostacyclin (also called prostaglandin I2 or PGI2) is a prostaglandin member of the eicosanoid family of lipid molecules. It inhibits platelet activation and is also an effective vasodilator.

When used as a drug, it is also known as epoprosteno ...

binds to prostanoid

Prostanoids are active lipid mediators that regulate inflammatory response. Prostanoids are a subclass of eicosanoids consisting of the prostaglandins (mediators of inflammatory and anaphylactic reactions), the thromboxanes (mediators of vasocons ...

receptors on the surface of resting platelets. This event stimulates the coupled Gs protein to increase adenylate cyclase

Adenylate cyclase (EC 4.6.1.1, also commonly known as adenyl cyclase and adenylyl cyclase, abbreviated AC) is an enzyme with systematic name ATP diphosphate-lyase (cyclizing; 3′,5′-cyclic-AMP-forming). It catalyzes the following reaction:

:A ...

activity and increases the production of cAMP, further promoting the efflux of calcium and reducing intracellular calcium availability for platelet activation.

ADP on the other hand binds to purinergic receptor

Purinergic receptors, also known as purinoceptors, are a family of plasma membrane molecules that are found in almost all mammalian tissues. Within the field of purinergic signalling, these receptors have been implicated in learning and memory, lo ...

s on the platelet surface. Since the thrombocytic purinergic receptor P2Y12

P2Y12 is a chemoreceptor for adenosine diphosphate (ADP) that belongs to the Gi class of a group of G protein-coupled (GPCR) purinergic receptors. This P2Y receptor family has several receptor subtypes with different pharmacological selec ...

is coupled to Gi proteins, ADP reduces platelet adenylate cyclase activity and cAMP production, leading to accumulation of calcium inside the platelet by inactivating the cAMP calcium efflux pump. The other ADP-receptor P2Y1

P2Y purinoceptor 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''P2RY1'' gene.

Function

The product of this gene, P2Y1 belongs to the family of G-protein coupled receptors. This family has several receptor subtypes with different pharmacolog ...

couples to Gq that activates phospholipase C-beta 2 (PLCB2

1-Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase beta-2 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''PLCB2'' gene.

Function

The gene codes for the enzyme phospholipase C β2. The enzyme catalyzes the formation of inositol 1,4,5-tris ...

), resulting in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

Inositol trisphosphate or inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate abbreviated InsP3 or Ins3P or IP3 is an inositol phosphate signaling molecule. It is made by hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a phospholipid that is located in the ...

(IP3) generation and intracellular release of more calcium. This together induces platelet activation. Endothelial ADPase degrades ADP and prevents this from happening. Clopidogrel

Clopidogrel — sold under the brand name Plavix, among others — is an antiplatelet medication used to reduce the risk of heart disease and stroke in those at high risk. It is also used together with aspirin in heart attacks and following t ...

and related antiplatelet medications also work as purinergic receptor P2Y12

P2Y12 is a chemoreceptor for adenosine diphosphate (ADP) that belongs to the Gi class of a group of G protein-coupled (GPCR) purinergic receptors. This P2Y receptor family has several receptor subtypes with different pharmacological selec ...

antagonists

An antagonist is a character in a story who is presented as the chief foe of the protagonist.

Etymology

The English word antagonist comes from the Greek ἀνταγωνιστής – ''antagonistēs'', "opponent, competitor, villain, enemy, riv ...

. Data suggest that ADP activates the PI3K/Akt pathway during a first wave of aggregation, leading to thrombin generation and PAR‐1 activation, which evokes a second wave of aggregation.

Trigger (induction)

Platelet activation begins seconds after adhesion occurs. It is triggered when ''collagen'' from the subendothelium binds with its receptors (GPVI

Glycoprotein VI (platelet), also known as GPVI, is a glycoprotein receptor for collagen which is expressed in platelets. In humans, glycoprotein VI is encoded by the ''GPVI'' gene.

GPVI was first cloned in 2000 by several groups including that ...

receptor and integrin α2β1) on the platelet. GPVI is associated with the Fc receptor gamma chain and leads via the activation of a tyrosine kinase cascade finally to the activation of PLC-gamma2 (PLCG2

1-Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase gamma-2 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''PLCG2'' gene.

Function

Enzymes of the phospholipase C family catalyze the hydrolysis of phospholipids to yield diacylglycerols an ...

) and more calcium release.

Tissue factor also binds to factor VII

Coagulation factor VII (, formerly known as proconvertin) is one of the proteins that causes blood to clot in the coagulation cascade, and in humans is coded for by the gene ''F7''. It is an enzyme of the serine protease class. Once bound to tis ...

in the blood, which initiates the extrinsic coagulation

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism o ...

cascade to increase thrombin

Thrombin (, ''fibrinogenase'', ''thrombase'', ''thrombofort'', ''topical'', ''thrombin-C'', ''tropostasin'', ''activated blood-coagulation factor II'', ''blood-coagulation factor IIa'', ''factor IIa'', ''E thrombin'', ''beta-thrombin'', ''gamma- ...

production. Thrombin is a potent platelet activator, acting through Gq and G12. These are G protein-coupled receptor

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), also known as seven-(pass)-transmembrane domain receptors, 7TM receptors, heptahelical receptors, serpentine receptors, and G protein-linked receptors (GPLR), form a large group of evolutionarily-related p ...

s and they turn on calcium-mediated signaling pathways

Signal transduction is the process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a series of molecular events, most commonly protein phosphorylation catalyzed by protein kinases, which ultimately results in a cellula ...

within the platelet, overcoming the baseline calcium efflux. Families of three G proteins (Gq, Gi, G12) operate together for full activation. Thrombin also promotes secondary fibrin-reinforcement of the platelet plug. Platelet activation in turn degranulates and releases factor V

Factor V (pronounced factor five) is a protein of the coagulation system, rarely referred to as proaccelerin or labile factor. In contrast to most other coagulation factors, it is not enzymatically active but functions as a cofactor. Deficienc ...

and fibrinogen

Fibrinogen (factor I) is a glycoprotein complex, produced in the liver, that circulates in the blood of all vertebrates. During tissue and vascular injury, it is converted enzymatically by thrombin to fibrin and then to a fibrin-based blood clo ...

, potentiating the coagulation cascade. So, in reality, the process of platelet plugging and coagulation are occurring simultaneously rather than sequentially, with each inducing the other to form the final fibrin-crosslinked thrombus.

Components (consequences)

=GPIIb/IIIa activation

=

Collagen-mediated GPVI signalling increases the platelet production of thromboxane A2

Thromboxane A2 (TXA2) is a type of thromboxane that is produced by activated platelets during hemostasis and has prothrombotic properties: it stimulates activation of new platelets as well as increases platelet aggregation. This is achieved by act ...

(TXA2) and decreases the production of prostacyclin

Prostacyclin (also called prostaglandin I2 or PGI2) is a prostaglandin member of the eicosanoid family of lipid molecules. It inhibits platelet activation and is also an effective vasodilator.

When used as a drug, it is also known as epoprosteno ...

. This occurs by altering the metabolic flux of platelet's eicosanoid

Eicosanoids are signaling molecules made by the enzymatic or non-enzymatic oxidation of arachidonic acid or other polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) that are, similar to arachidonic acid, around 20 carbon units in length. Eicosanoids are a s ...

synthesis pathway, which involves enzymes phospholipase A2

The enzyme phospholipase A2 (EC 3.1.1.4, PLA2, systematic name phosphatidylcholine 2-acylhydrolase) catalyse the cleavage of fatty acids in position 2 of phospholipids, hydrolyzing the bond between the second fatty acid “tail” and the glyce ...

, cyclo-oxygenase 1, and thromboxane-A synthase

Thromboxane A synthase 1 (, platelet, cytochrome P450, family 5, subfamily A), also known as TBXAS1, is a cytochrome P450 enzyme that, in humans, is encoded by the ''TBXAS1'' gene.

Function

This gene encodes a member of the cytochrome P450 supe ...

. Platelets secrete thromboxane A2, which acts on the platelet's own thromboxane receptor

The thromboxane receptor (TP) also known as the prostanoid TP receptor is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''TBXA2R'' gene, The thromboxane receptor is one among the five classes of prostanoid receptors and was the first eicosanoid rec ...

s on the platelet surface (hence the so-called "out-in" mechanism), and those of other platelets. These receptors trigger intraplatelet signaling, which converts GPIIb/IIIa

In medicine, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa, also known as integrin αIIbβ3) is an integrin complex found on platelets. It is a receptor for fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor and aids platelet activation. The complex is formed via calcium ...

receptors to their active form to initiate ''aggregation''.

=Granule secretion

=

Platelets contain dense granules, lambda granules and

Platelets contain dense granules, lambda granules and alpha granules

Alpha granules, (α-granules) also known as platelet alpha-granules are a cellular component of platelets. Platelets contain different types of Granule (cell biology), granules that perform different functions, and include alpha granules, dense gra ...

. Activated platelets secrete the contents of these granules through their canalicular systems to the exterior. Simplistically, bound and activated platelets degranulate to release platelet chemotactic

Chemotaxis (from '' chemo-'' + ''taxis'') is the movement of an organism or entity in response to a chemical stimulus. Somatic cells, bacteria, and other single-cell or multicellular organisms direct their movements according to certain chemical ...

agents to attract more platelets to the site of endothelial injury. Granule characteristics:

* α granules (alpha granules) – containing P-selectin

P-selectin is a type-1 transmembrane protein that in humans is encoded by the SELP gene.

P-selectin functions as a cell adhesion molecule (CAM) on the surfaces of activated endothelial cells, which line the inner surface of blood vessels, and act ...

, platelet factor 4

Platelet factor 4 (PF4) is a small cytokine belonging to the CXC chemokine family that is also known as chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 4 (CXCL4) . This chemokine is released from alpha-granules of activated platelets during platelet aggregation, ...

, transforming growth factor-β1, platelet-derived growth factor

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) is one among numerous growth factors that regulate cell growth and division. In particular, PDGF plays a significant role in blood vessel formation, the growth of blood vessels from already-existing blood v ...

, fibronectin

Fibronectin is a high- molecular weight (~500-~600 kDa) glycoprotein of the extracellular matrix that binds to membrane-spanning receptor proteins called integrins. Fibronectin also binds to other extracellular matrix proteins such as collage ...

, B-thromboglobulin, vWF, fibrinogen

Fibrinogen (factor I) is a glycoprotein complex, produced in the liver, that circulates in the blood of all vertebrates. During tissue and vascular injury, it is converted enzymatically by thrombin to fibrin and then to a fibrin-based blood clo ...

, and coagulation factor

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism o ...

s V and XIII

XIII may refer to:

* 13 (number) or XIII in Roman numerals

* 13th century in Roman numerals

* ''XIII'' (comics), a Belgian comic book series by Jean Van Hamme and William Vance

** ''XIII'' (2003 video game), a 2003 video game based on the comic b ...

* δ granules (delta or dense granules) – containing ADP or ATP, calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to ...

, and serotonin

Serotonin () or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is a monoamine neurotransmitter. Its biological function is complex and multifaceted, modulating mood, cognition, reward, learning, memory, and numerous physiological processes such as vomiting and vas ...

* γ granules (gamma granules) – similar to lysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle found in many animal cells. They are spherical vesicles that contain hydrolytic enzymes that can break down many kinds of biomolecules. A lysosome has a specific composition, of both its membrane prot ...

s and contain several hydrolytic enzymes

* λ granules (lambda granules) – contents involved in resorption during later stages of vessel repair

=Morphology change

=

As shown by flow cytometry and electron microscopy, the most sensitive sign of activation, when exposed to platelets using ADP, are morphological changes. Mitochondrial hyperpolarization is a key event in initiating changes in morphology. Intraplatelet calcium concentration increases, stimulating the interplay between the microtubule/actin filament complex. The continuous changes in shape from the unactivated to the fully activated platelet is best seen on scanning electron microscopy. Three steps along this path are named ''early dendritic'', ''early spread'' and ''spread''. The surface of the unactivated platelet looks very similar to the surface of the brain, with a wrinkled appearance from numerous shallow folds to increase the surface area; ''early dendritic'', an octopus with multiple arms and legs; ''early spread'', an uncooked frying egg in a pan, the "yolk" being the central body; and the ''spread'', a cooked fried egg with a denser central body.

These changes are all brought about by the interaction of the microtubule/actin complex with the platelet cell membrane and open canalicular system (OCS), which is an extension and invagination of that membrane. This complex runs just beneath these membranes and is the chemical motor that literally pulls the invaginated OCS out of the interior of the platelet, like turning pants pockets inside out, creating the dendrites. This process is similar to the mechanism of contraction in a muscle cell

A muscle cell is also known as a myocyte when referring to either a cardiac muscle cell (cardiomyocyte), or a smooth muscle cell as these are both small cells. A skeletal muscle cell is long and threadlike with many nuclei and is called a muscl ...

. The entire OCS thus becomes indistinguishable from the initial platelet membrane as it forms the "fried egg". This dramatic increase in surface area comes about with neither stretching nor adding phospholipids to the platelet membrane.

=Platelet-coagulation factor interactions: coagulation facilitation

=

Platelet activation causes its membrane surface to become negatively charged. One of the signaling pathways turns on scramblase

Scramblase is a protein responsible for the translocation of phospholipids between the two monolayers of a lipid bilayer of a cell membrane. In humans, phospholipid scramblases (PLSCRs) constitute a family of five homologous proteins tha ...

, which moves negatively charged phospholipid

Phospholipids, are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s from the inner to the outer platelet membrane surface. These phospholipids then bind the tenase

In coagulation, the procoagulant protein factor X can be activated into factor Xa in two ways: either extrinsically or intrinsically.

The activating complexes are together called tenase. Tenase is a blend word of "ten" and the suffix "-ase", whic ...

and prothrombinase The prothrombinase complex consists of the serine protease, Factor Xa, and the protein cofactor, Factor Va. The complex assembles on negatively charged phospholipid membranes in the presence of calcium ions. The prothrombinase complex catalyzes the ...

complexes, two of the sites of interplay between platelets and the coagulation cascade. Calcium ions are essential for the binding of these coagulation factors.

In addition to interacting with vWF and fibrin, platelets interact with thrombin, Factors X, Va, VIIa, XI, IX, and prothrombin to complete formation via the coagulation cascade.[ The platelets from rats were conclusively shown to express tissue factor protein and also it was proved that the rat platelets carry both the tissue factor pre-mRNA and mature mRNA.

]

Aggregation

Aggregation begins minutes after activation, and occurs as a result of turning on the

Aggregation begins minutes after activation, and occurs as a result of turning on the GPIIb/IIIa

In medicine, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa, also known as integrin αIIbβ3) is an integrin complex found on platelets. It is a receptor for fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor and aids platelet activation. The complex is formed via calcium ...

receptor, allowing these receptors to bind with vWF or fibrinogen

Fibrinogen (factor I) is a glycoprotein complex, produced in the liver, that circulates in the blood of all vertebrates. During tissue and vascular injury, it is converted enzymatically by thrombin to fibrin and then to a fibrin-based blood clo ...

.

Immune function

Platelets have central role in innate immunity, initiating and participating in multiple inflammatory processes, directly binding pathogens and even destroying them. This supports clinical data which show that many with serious bacterial or viral infections have thrombocytopenia, thus reducing their contribution to inflammation. Also platelet-leukocyte aggregates (PLAs) found in circulation are typical in sepsis

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

or inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of inflammation, inflammatory conditions of the colon (anatomy), colon and small intestine, Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis being the principal types. Crohn's disease affects the small intestine a ...

, showing the connection between thrombocytes and immune cells.

Immunothrombosis

As hemostasis is a basic function of thrombocytes in mammals, it also has its uses in possible infection confinement.Atlantic horseshoe crab

The Atlantic horseshoe crab (''Limulus polyphemus''), also known as the American horseshoe crab, is a species of marine and brackish chelicerate arthropod. Despite their name, horseshoe crabs are more closely related to spiders, ticks, and scorp ...

(living fossil

A living fossil is an extant taxon that cosmetically resembles related species known only from the fossil record. To be considered a living fossil, the fossil species must be old relative to the time of origin of the extant clade. Living fossi ...

estimated to be over 400 million years old), the only blood cell type, the amebocyte, facilitates both the hemostatic function and the encapsulation and phagocytosis of pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

s by means of exocytosis

Exocytosis () is a form of active transport and bulk transport in which a cell transports molecules (e.g., neurotransmitters and proteins) out of the cell ('' exo-'' + ''cytosis''). As an active transport mechanism, exocytosis requires the use o ...

of intracellular granules containing bactericidal

A bactericide or bacteriocide, sometimes abbreviated Bcidal, is a substance which kills bacteria. Bactericides are disinfectants, antiseptics, or antibiotics.

However, material surfaces can also have bactericidal properties based solely on their ...

defense molecules. Blood clotting supports the immune function by trapping the pathogenic bacteria within.

Although thrombosis, blood coagulation in intact blood vessels, is usually viewed as a pathological immune response, leading to obturation of lumen of blood vessel and subsequent hypoxic tissue damage, in some cases, directed thrombosis, called immunothrombosis, can locally control the spread of the infection. The thrombosis is directed in concordance of platelets, neutrophil

Neutrophils (also known as neutrocytes or heterophils) are the most abundant type of granulocytes and make up 40% to 70% of all white blood cells in humans. They form an essential part of the innate immune system, with their functions varying in ...

s and monocyte

Monocytes are a type of leukocyte or white blood cell. They are the largest type of leukocyte in blood and can differentiate into macrophages and conventional dendritic cells. As a part of the vertebrate innate immune system monocytes also inf ...

s. The process is initiated either by immune cells by activating their pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), or by platelet-bacterial binding. Platelets can bind to bacteria either directly through thrombocytic PRRspathogen-associated molecular pattern

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are small molecular motifs conserved within a class of microbes. They are recognized by toll-like receptors (TLRs) and other pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in both plants and animals. A vast arra ...

s (PAMPs), or damage-associated molecular pattern

Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are molecules within cells that are a component of the innate immune response released from damaged or dying cells due to trauma or an infection by a pathogen. They are also known as danger-associated m ...

s (DAMPs) by activating the extrinsic pathway of coagulation. Neutrophils facilitate the blood coagulation by NETosis. In turn, the platelets facilitate neutrophils' NETosis. NETs bind tissue factor, binding the coagulation centres to the location of infection. They also activate the intrinsic coagulation pathway by providing its negatively charged surface to the factor XII. Other neutrophil secretions, such as proteolytic enzymes, which cleave coagulation inhibitors, also bolster the process.disseminated intravascular coagulation

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a condition in which blood clots form throughout the body, blocking small blood vessels. Symptoms may include chest pain, shortness of breath, leg pain, problems speaking, or problems moving parts o ...

(DIC) or deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a type of venous thrombosis involving the formation of a blood clot in a deep vein, most commonly in the legs or pelvis. A minority of DVTs occur in the arms. Symptoms can include pain, swelling, redness, and enla ...

. DIC in sepsis is a prime example of both dysregulated coagulation process as well as undue systemic inflammatory response resulting in multitude of microthrombi of similar composition to that in physiological immunothrombosis – fibrin, platelets, neutrophils and NETs.

Inflammation

Platelets are rapidly deployed to sites of injury or infection, and potentially modulate inflammatory processes by interacting with leukocytes

White blood cells, also called leukocytes or leucocytes, are the cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign invaders. All white blood cells are produced and derived from mult ...

and by secreting cytokines

Cytokines are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling. Cytokines are peptides and cannot cross the lipid bilayer of cells to enter the cytoplasm. Cytokines have been shown to be involved in autocrin ...

, chemokines

Chemokines (), or chemotactic cytokines, are a family of small cytokines or signaling proteins secreted by cells that induce directional movement of leukocytes, as well as other cell types, including endothelial and epithelial cells. In addition ...

and other inflammatory mediators.platelet-derived growth factor

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) is one among numerous growth factors that regulate cell growth and division. In particular, PDGF plays a significant role in blood vessel formation, the growth of blood vessels from already-existing blood v ...

(PDGF).

Platelets modulate neutrophils by forming platelet-leukocyte aggregates (PLAs). These formations induce upregulated production of αmβ2 ( Mac-1) integrin in neutrophils. Interaction with PLAs also induce degranulation and increased phagocytosis in neutrophils. Platelets are also the largest source of soluble CD40L

CD154, also called CD40 ligand or CD40L, is a protein that is primarily expressed on activated T cells and is a member of the TNF superfamily of molecules. It binds to CD40 on antigen-presenting cells (APC), which leads to many effects dependin ...

which induces production of reactive oxygen species

In chemistry, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (). Examples of ROS include peroxides, superoxide, hydroxyl radical, singlet oxygen, and alpha-oxygen.

The reduction of molecular oxygen () p ...

(ROS) and upregulate expression of adhesion molecules, such as E-selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, in neutrophils, activates macrophages and activates cytotoxic response in T and B lymphocytes.fibroblast-like synoviocyte

Fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) represent a specialised cell type located inside joints in the synovium. These cells play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Fibroblast-like syno ...

s, most prominently Il-6 and Il-8. Inflammatory damage to surrounding extracellular matrix continually reveals more collagen, maintaining the microvesicle production.

Adaptive immunity

Activated platelets are able to participate in adaptive immunity, interacting with antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

. They are able to specifically bind IgG

Immunoglobulin G (Ig G) is a type of antibody. Representing approximately 75% of serum antibodies in humans, IgG is the most common type of antibody found in blood circulation. IgG molecules are created and released by plasma B cells. Each IgG ...

through FcγRIIA

Low affinity immunoglobulin gamma Fc region receptor II-a is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''FCGR2A'' gene.

Interactions

FCGR2A has been shown to interact with PIK3R1 and Syk.

See also

* CD32

CD32 (cluster of differentiation 3 ...

, receptor for constant fragment (Fc) of IgG. When activated and bound to IgG opsonised bacteria, the platelets subsequently release reactive oxygen species (ROS), antimicrobial peptides, defensins, kinocidins and proteases, killing the bacteria directly.platelet factor 4

Platelet factor 4 (PF4) is a small cytokine belonging to the CXC chemokine family that is also known as chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 4 (CXCL4) . This chemokine is released from alpha-granules of activated platelets during platelet aggregation, ...

(PF4), connecting innate and adaptive immune responses.

Signs and symptoms of disorders

''Spontaneous and excessive bleeding'' can occur because of platelet disorders. This bleeding can be caused by deficient numbers of platelets, dysfunctional platelets, or very excessive numbers of platelets: over 1.0 million/microliter. (The excessive numbers create a relative von Willebrand factor deficiency due to sequestration.)

One can get a clue as to whether bleeding is due to a platelet disorder or a coagulation factor disorder by the characteristics and location of the bleeding.[ All of the following suggest platelet bleeding, not coagulation bleeding: the bleeding from a skin cut such as a razor nick is prompt and excessive, but can be controlled by pressure; spontaneous bleeding into the skin which causes a purplish stain named by its size: ]petechiae

A petechia () is a small red or purple spot (≤4 mm in diameter) that can appear on the skin, conjunctiva, retina, and mucous membranes which is caused by haemorrhage of capillaries. The word is derived from Italian , 'freckle,' of obscure origin ...

, purpura

Purpura () is a condition of red or purple discolored spots on the skin that do not blanch on applying pressure. The spots are caused by bleeding underneath the skin secondary to platelet disorders, vascular disorders, coagulation disorders, ...

, ecchymoses

A bruise, also known as a contusion, is a type of hematoma of tissue, the most common cause being capillaries damaged by trauma, causing localized bleeding that extravasates into the surrounding interstitial tissues. Most bruises occur close e ...

; bleeding into mucous membranes causing bleeding gums, nose bleed, and gastrointestinal bleeding; menorrhagia; and intraretinal and intracranial bleeding.

Excessive numbers of platelets, and/or normal platelets responding to abnormal vessel walls, can result in venous thrombosis

Venous thrombosis is blockage of a vein caused by a thrombus (blood clot). A common form of venous thrombosis is deep vein thrombosis (DVT), when a blood clot forms in the deep veins. If a thrombus breaks off (embolizes) and flows to the lungs to ...

and arterial thrombosis

Thrombosis (from Ancient Greek "clotting") is the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel (a vein or an artery) is injured, the body uses platelets (thr ...

. The symptoms depend on the site of thrombosis.

Measurement and Testing

Measurement

Platelet concentration in the blood (i.e. platelet count), is measured either manually using a hemocytometer

The hemocytometer (or haemocytometer) is a counting-chamber device originally designed and usually used for counting blood cells.

The hemocytometer was invented by Louis-Charles Malassez and consists of a thick glass microscope slide with a ...

, or by placing blood in an automated platelet analyzer using particle counting, such as a Coulter counter

A Coulter counter is an apparatus for counting and sizing particles suspended in electrolytes. The Coulter counter is the commercial term for the technique known as resistive pulse sensing or electrical zone sensing, the apparatus is based on T ...

or optical methods. On a stained

On a stained blood smear

A blood smear, peripheral blood smear or blood film is a thin layer of blood smeared on a glass microscope slide and then stained in such a way as to allow the various blood cells to be examined microscopically. Blood smears are examined in the ...

, platelets appear as dark purple spots, about 20% the diameter of red blood cells. The smear is used to examine platelets for size, shape, qualitative number, and clumping. A healthy adult typically has 10 to 20 times more red blood cells than platelets.

Bleeding time

Bleeding time

Bleeding time is a medical test done on someone to assess their platelets function. It involves making a patient bleed, then timing how long it takes for them to stop bleeding using a stopwatch or other suitable devices.

The term template bleedin ...

was first developed as a test of platelet function by Duke in 1910.microvasculature

The microcirculation is the circulation of the blood in the smallest blood vessels, the microvessels of the microvasculature present within organ tissues. The microvessels include terminal arterioles, metarterioles, capillaries, and venules. ...

.

Multiple electrode aggregometry

In multiple electrode aggregometry

Multiplate multiple electrode aggregometry (MEA) is a test of platelet function in whole blood. The test can be used to diagnose platelet disorders, monitor antiplatelet therapy, and is also investigated as a potential predictor of transfusion requ ...

, anticoagulated whole blood is mixed with saline and a platelet agonist in a single-use cuvette with two pairs of electrodes. The increase in impedance between the electrodes as platelets aggregate onto them, is measured and visualized as a curve.

Light transmission aggregometry

In light transmission aggregometry (LTA), platelet-rich plasma is placed between a light source and a photocell. Unaggregated plasma allows relatively little light to pass through. After adding an agonist, the platelets aggregate, resulting in greater light transmission, which is detected by the photocell.

PFA-100

The PFA-100 (Platelet Function Assay - 100) is a system for analysing platelet function in which citrated whole blood is aspirated through a disposable cartridge containing an aperture within a membrane coated with either collagen and epinephrine or collagen and ADP. These agonists induce platelet adhesion, activation and aggregation, leading to rapid occlusion of the aperture and cessation of blood flow termed the closure time (CT). An elevated CT with EPI and collagen can indicate intrinsic defects such as von Willebrand disease

Von Willebrand disease (VWD) is the most common hereditary blood-clotting disorder in humans. An acquired form can sometimes result from other medical conditions. It arises from a deficiency in the quality or quantity of von Willebrand factor ( ...

, uremia

Uremia is the term for high levels of urea in the blood. Urea is one of the primary components of urine. It can be defined as an excess of amino acid and protein metabolism end products, such as urea and creatinine, in the blood that would be nor ...

, or circulating platelet inhibitors. The follow-up test involving collagen and ADP is used to indicate if the abnormal CT with collagen and EPI was caused by the effects of acetyl sulfosalicylic acid (aspirin) or medications containing inhibitors.

Disorders

Adapted from:[

Low platelet concentration is called ]thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia is a condition characterized by abnormally low levels of platelets, also known as thrombocytes, in the blood. It is the most common coagulation disorder among intensive care patients and is seen in a fifth of medical patients an ...

, and is due to either ''decreased production'' or ''increased destruction''. Elevated platelet concentration is called thrombocytosis

Thrombocythemia is a condition of high platelet (thrombocyte) count in the blood. Normal count is in the range of 150x109 to 450x109 platelets per liter of blood, but investigation is typically only considered if the upper limit exceeds 750x109/L. ...

, and is either ''congenital

A birth defect, also known as a congenital disorder, is an abnormal condition that is present at birth regardless of its cause. Birth defects may result in disabilities that may be physical, intellectual, or developmental. The disabilities can ...

'', ''reactive'' (to cytokine

Cytokines are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling. Cytokines are peptides and cannot cross the lipid bilayer of cells to enter the cytoplasm. Cytokines have been shown to be involved in autocrin ...

s), or due to ''unregulated production'': one of the ''myeloproliferative neoplasm

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are a group of rare blood cancers in which excess red blood cells, white blood cells or platelets are produced in the bone marrow. ''Myelo'' refers to the bone marrow, ''proliferative'' describes the rapid growt ...

s'' or certain other myeloid neoplasm

A neoplasm () is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of tissue. The process that occurs to form or produce a neoplasm is called neoplasia. The growth of a neoplasm is uncoordinated with that of the normal surrounding tissue, and persists ...

s. A disorder of platelet function is called a thrombocytopathy

Platelets, also called thrombocytes (from Greek θρόμβος, "clot" and κύτος, "cell"), are a component of blood whose function (along with the coagulation factors) is to react to bleeding from blood vessel injury by clumping, thereby ini ...

or a platelet function disorder

Platelets, also called thrombocytes (from Greek θρόμβος, "clot" and κύτος, "cell"), are a component of blood whose function (along with the coagulation factors) is to react to bleeding from blood vessel injury by clumping, thereby ini ...

.

Normal platelets can respond to an ''abnormality on the vessel wall'' rather than to hemorrhage, resulting in inappropriate platelet adhesion/activation and thrombosis

Thrombosis (from Ancient Greek "clotting") is the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel (a vein or an artery) is injured, the body uses platelets (thro ...

: the formation of a clot within an intact vessel. This type of thrombosis arises by mechanisms different from those of a normal clot: namely, extending the fibrin of venous thrombosis

Venous thrombosis is blockage of a vein caused by a thrombus (blood clot). A common form of venous thrombosis is deep vein thrombosis (DVT), when a blood clot forms in the deep veins. If a thrombus breaks off (embolizes) and flows to the lungs to ...

; extending an unstable or ruptured arterial plaque, causing arterial thrombosis

Thrombosis (from Ancient Greek "clotting") is the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel (a vein or an artery) is injured, the body uses platelets (thr ...

; and microcirculatory thrombosis. An arterial thrombus

A thrombus (plural thrombi), colloquially called a blood clot, is the final product of the blood coagulation step in hemostasis. There are two components to a thrombus: aggregated platelets and red blood cells that form a plug, and a mesh of c ...

may partially obstruct blood flow, causing downstream ischemia

Ischemia or ischaemia is a restriction in blood supply to any tissue, muscle group, or organ of the body, causing a shortage of oxygen that is needed for cellular metabolism (to keep tissue alive). Ischemia is generally caused by problems wi ...

, or may completely obstruct it, causing downstream tissue death.

The three broad categories of platelet disorders are "not enough", "dysfunctional", and "too many".[

]

Thrombocytopenia

* Immune thrombocytopenia

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), also known as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura or immune thrombocytopenia, is a type of thrombocytopenic purpura defined as an isolated low platelet count with a normal bone marrow in the absence of othe ...

(ITP) – formerly known as immune thrombocytopenic purpura and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

* Splenomegaly

Splenomegaly is an enlargement of the spleen. The spleen usually lies in the left upper quadrant (LUQ) of the human abdomen. Splenomegaly is one of the four cardinal signs of ''hypersplenism'' which include: some reduction in number of circulating ...

** Gaucher's disease

Gaucher's disease or Gaucher disease () (GD) is a genetic disorder

A genetic disorder is a health problem caused by one or more abnormalities in the genome. It can be caused by a mutation in a single gene (monogenic) or multiple genes (polyg ...

* Familial thrombocytopenia

* Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (often abbreviated to chemo and sometimes CTX or CTx) is a type of cancer treatment that uses one or more anti-cancer drugs (chemotherapeutic agents or alkylating agents) as part of a standardized chemotherapy regimen. Chemotherap ...

* Babesiosis

Babesiosis or piroplasmosis is a malaria-like parasitic disease caused by infection with a eukaryotic parasite in the order Piroplasmida, typically a ''Babesia'' or ''Theileria'', in the phylum Apicomplexa. Human babesiosis transmission via ti ...

* Dengue fever

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne tropical disease caused by the dengue virus. Symptoms typically begin three to fourteen days after infection. These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characterist ...

* Onyalai

Onyalai (Pronunciation: ō′nē-al′ā-ē) is a form of thrombocytopenia that affects some of the population in areas of central Africa. Onyalai exhibits similarities to idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) but differs in pathogenesis ...

* Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a blood disorder that results in blood clots forming in small blood vessels throughout the body. This results in a low platelet count, low red blood cells due to their breakdown, and often kidney, h ...

* HELLP syndrome

HELLP syndrome is a complication of pregnancy; the acronym stands for hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count. It usually begins during the last three months of pregnancy or shortly after childbirth. Symptoms may include feelin ...

* Hemolytic–uremic syndrome

Hemolytic–uremic syndrome (HUS) is a group of blood disorders characterized by low red blood cells, acute kidney failure, and low platelets. Initial symptoms typically include bloody diarrhea, fever, vomiting, and weakness. Kidney problems and ...

* Drug-induced thrombocytopenic purpura

Drug-induced thrombocytopenic purpura is a skin condition result from a low platelet count due to drug-induced anti-platelet antibodies caused by drugs such as heparin, sulfonamines, digoxin, quinine, and quinidine.

See also

* Idiopathic thro ...

(five known drugs – most problematic is heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is the development of thrombocytopenia (a low platelet count), due to the administration of various forms of heparin, an anticoagulant. HIT predisposes to thrombosis (the abnormal formation of blood clots in ...

(HIT)

* Pregnancy-associated

* Neonatal alloimmune associated

* Aplastic anemia

Aplastic anemia is a cancer in which the body fails to make blood cells in sufficient numbers. Blood cells are produced in the bone marrow by stem cells that reside there. Aplastic anemia causes a deficiency of all blood cell types: red blood ...

* Transfusion-associated

* Pseudothrombocytopenia

Pseudothrombocytopenia or spurious thrombocytopenia is an in-vitro sampling problem which may mislead the diagnosis towards the more critical condition of thrombocytopenia. The phenomenon occurs when the anticoagulant used while testing the blood ...

* Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia

Post-vaccination embolic and thrombotic events, termed vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT), vaccine-induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia (VIPIT), thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS), vaccine-induced imm ...

(VITT)

Altered platelet function (thrombocytopathy)

* Congenital

** Disorders of adhesion

*** Bernard–Soulier syndrome

Bernard–Soulier syndrome (BSS) is a rare autosomal recessive bleeding disorder that is caused by a deficiency of the ''glycoprotein Ib-IX-V complex'' (GPIb-IX-V), the receptor for von Willebrand factor. The incidence of BSS is estimated to be l ...

** Disorders of activation

*** Disorders of granule amount or release

*** Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome

Heřmanský–Pudlák syndrome (often written Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome or abbreviated HPS) is an extremely rare autosomal recessive disorder which results in oculocutaneous albinism (decreased pigmentation), bleeding problems due to a platele ...

*** Gray platelet syndrome

Gray platelet syndrome (GPS), or platelet alpha-granule deficiency, is a rare congenital autosomal recessive bleeding disorder caused by a reduction or absence of alpha-granules in blood platelets, and the release of proteins normally contained in ...

*** ADP receptor defect

*** Decreased cyclooxygenase activity

*** Platelet storage pool deficiency

** Disorders of aggregation

*** Glanzmann's thrombasthenia

Glanzmann's thrombasthenia is an abnormality of the platelets. It is an extremely rare coagulopathy (bleeding disorder due to a blood abnormality), in which the platelets contain defective or low levels of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GpIIb/IIIa), which ...

*** Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome

Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome (WAS) is a rare X-linked recessive disease characterized by eczema, thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), immune deficiency, and bloody diarrhea (secondary to the thrombocytopenia). It is also sometimes called the eczem ...

** Disorders of coagulant activity

*** COAT platelet defect

A collagen- and thrombin-activated (COAT) platelet defect is a platelet function disorder that is due to a reduced ability to generate procoagulant platelets. It is associated with a clinically relevant bleeding phenotype.

During physiological p ...

*** Scott syndrome

Scott syndrome is a rare congenital bleeding disorder that is due to a defect in a platelet mechanism required for blood coagulation.

Normally when a vascular injury occurs (i.e., a cut, scrape or other injury that causes bleeding), platelets ar ...

* Acquired

** Disorders of adhesion

*** Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a rare, acquired, life-threatening disease of the blood characterized by destruction of red blood cells by the complement system, a part of the body's innate immune system. This destructive process occu ...

*** Asthma

Asthma is a long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wheezing, cou ...

Samter's triad

Aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), also termed aspirin-induced asthma, is a medical condition initially defined as consisting of three key features: asthma, respiratory symptoms exacerbated by aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inf ...

(aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease/AERD)Cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

*** Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

*** Decreased cyclooxygenase activity

Thrombocytosis and thrombocythemia

* Reactive

** Chronic infection

** Chronic inflammation

** Malignancy

** Hyposplenism (post-splenectomy)

** Iron deficiency

** Acute blood loss

* Myeloproliferative neoplasm

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are a group of rare blood cancers in which excess red blood cells, white blood cells or platelets are produced in the bone marrow. ''Myelo'' refers to the bone marrow, ''proliferative'' describes the rapid growt ...

s – platelets are both elevated and activated

** Essential thrombocythemia

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is a rare chronic blood cancer (myeloproliferative neoplasm) characterised by the overproduction of platelets (thrombocytes) by megakaryocytes in the bone marrow. It may, albeit rarely, develop into acute myeloid leuk ...

** Polycythemia vera

Polycythemia vera is an uncommon myeloproliferative neoplasm (a type of chronic leukemia) in which the bone marrow makes too many red blood cells. It may also result in the overproduction of white blood cells and platelets.

Most of the health ...

* Associated with other myeloid neoplasms

* Congenital

Pharmacology

Anti-inflammatory drugs

Some drugs used to treat inflammation have the unwanted side effect of suppressing normal platelet function. These are the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS). Aspirin

Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and/or inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions which aspirin is used to treat inc ...

irreversibly disrupts platelet function by inhibiting cyclooxygenase

Cyclooxygenase (COX), officially known as prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase (PTGS), is an enzyme (specifically, a family of isozymes, ) that is responsible for formation of prostanoids, including thromboxane and prostaglandins such as prosta ...

-1 (COX1), and hence normal hemostasis. The resulting platelets are unable to produce new cyclooxygenase because they have no DNA. Normal platelet function will not return until the use of aspirin has ceased and enough of the affected platelets have been replaced by new ones, which can take over a week. Ibuprofen

Ibuprofen is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that is used for treating pain, fever, and inflammation. This includes painful menstrual periods, migraines, and rheumatoid arthritis. It may also be used to close a patent ductus arte ...

, another NSAID

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are members of a therapeutic drug class which reduces pain, decreases inflammation, decreases fever, and prevents blood clots. Side effects depend on the specific drug, its dose and duration of ...

, does not have such a long duration effect, with platelet function usually returning within 24 hours, and taking ibuprofen before aspirin prevents the irreversible effects of aspirin.

Drugs that suppress platelet function

These drugs are used to prevent thrombus formation.

Oral agents

* Aspirin

Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and/or inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions which aspirin is used to treat inc ...

* Clopidogrel

Clopidogrel — sold under the brand name Plavix, among others — is an antiplatelet medication used to reduce the risk of heart disease and stroke in those at high risk. It is also used together with aspirin in heart attacks and following t ...

* Cilostazol

Cilostazol, sold under the brand name Pletal among others, is a medication used to help the symptoms of intermittent claudication in peripheral vascular disease. If no improvement is seen after 3 months, stopping the medication is reasonable. It ...

* Ticlopidine

Ticlopidine, sold under the brand name Ticlid, is a medication used to reduce the risk of thrombotic strokes. It is an antiplatelet drug in the thienopyridine family which is an adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor inhibitor. Research initially s ...

* Ticagrelor

Ticagrelor, sold under the brand name Brilinta among others, is a medication used for the prevention of stroke, heart attack and other events in people with acute coronary syndrome, meaning problems with blood supply in the coronary arteries. It ...

* Prasugrel

Prasugrel, sold under the brand name Effient in the US, Australia and India, and Efient in the EU) is a medication used to prevent formation of blood clots. It is a platelet inhibitor and an irreversible antagonist of P2Y12 ADP receptors and is ...

Drugs that stimulate platelet production

* Thrombopoietin mimetics Thrombopoietin mimetics are drugs that considerably increase platelet production by stimulating the receptor for the hormone thrombopoietin; Romiplostim and Eltrombopag

Eltrombopag, sold under the brand name Promacta among others, is a medica ...

* Desmopressin

Desmopressin, sold under the trade name DDAVP among others, is a medication used to treat diabetes insipidus, bedwetting, hemophilia A, von Willebrand disease, and high blood urea levels. In hemophilia A and von Willebrand disease, it should on ...

* Factor VIIa

Coagulation factor VII (, formerly known as proconvertin) is one of the proteins that causes blood to clot in the coagulation cascade, and in humans is coded for by the gene ''F7''. It is an enzyme of the serine protease class. Once bound to tiss ...

Intravenous agents

* Abciximab

Abciximab, a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonist manufactured by Janssen Biologics BV and distributed by Eli Lilly under the trade name ReoPro, is a platelet aggregation inhibitor mainly used during and after coronary artery procedures lik ...

* Eptifibatide

Eptifibatide (Integrilin, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, also co-promoted by Schering-Plough/Essex), is an antiplatelet drug of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor class. Eptifibatide is a cyclic heptapeptide derived from a disintegrin protein () ...

* Tirofiban

Tirofiban, sold under the brand name Aggrastat, is an antiplatelet medication. It belongs to a class of antiplatelets named glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Tirofiban is a small molecule inhibitor of the protein-protein interaction between fibr ...

* Others: oprelvekin, romiplostim

Romiplostim, sold under the brand name Nplate among others, is a fusion protein analog of thrombopoietin, a hormone that regulates platelet production.

Indications and Marketing

The drug was developed by Amgen through a restricted usage program ...

, eltrombopag

Eltrombopag, sold under the brand name Promacta among others, is a medication used to treat thrombocytopenia (abnormally low platelet counts) and severe aplastic anemia. Eltrombopag is sold under the brand name Revolade outside the US and is mar ...

, argatroban

Argatroban is an anticoagulant that is a small molecule direct thrombin inhibitor. In 2000, argatroban was licensed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for prophylaxis or treatment of thrombosis in patients with heparin-induced thrombocyto ...

Therapies

Transfusion

Indications

Platelet transfusion

Platelet transfusion, also known as platelet concentrate, is used to prevent or treat bleeding in people with either a low platelet count or poor platelet function. Often this occurs in people receiving cancer chemotherapy. Preventive transfusi ...

is most frequently used to correct unusually low platelet counts, either to prevent spontaneous bleeding (typically at counts below 10×109/L) or in anticipation of medical procedures that will necessarily involve some bleeding. For example, in patients undergoing surgery

Surgery ''cheirourgikē'' (composed of χείρ, "hand", and ἔργον, "work"), via la, chirurgiae, meaning "hand work". is a medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a person to investigate or treat a pat ...

, a level below 50×109/L is associated with abnormal surgical bleeding, and regional anaesthetic

Local anesthesia is any technique to induce the absence of sense, sensation in a specific part of the body, generally for the aim of inducing local analgesia, that is, local insensitivity to pain, although other local senses may be affected as we ...

procedures such as epidural

Epidural administration (from Ancient Greek ἐπί, , upon" + ''dura mater'') is a method of medication administration in which a medicine is injected into the epidural space around the spinal cord. The epidural route is used by physicians an ...

s are avoided for levels below 80×109/L.clopidogrel

Clopidogrel — sold under the brand name Plavix, among others — is an antiplatelet medication used to reduce the risk of heart disease and stroke in those at high risk. It is also used together with aspirin in heart attacks and following t ...

. Finally, platelets may be transfused as part of a massive transfusion protocol, in which the three major blood components (red blood cells, plasma, and platelets) are transfused to address severe hemorrhage. Platelet transfusion is contraindicated in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a blood disorder that results in blood clots forming in small blood vessels throughout the body. This results in a low platelet count, low red blood cells due to their breakdown, and often kidney, h ...

(TTP), as it fuels the coagulopathy

Coagulopathy (also called a bleeding disorder) is a condition in which the blood's ability to coagulate (form clots) is impaired. This condition can cause a tendency toward prolonged or excessive bleeding (bleeding diathesis), which may occur spo ...

.

Collection

Platelets are either isolated from collected units of whole blood and pooled to make a therapeutic dose, or collected by platelet apheresis: blood is taken from the donor, passed through a device which removes the platelets, and the remainder is returned to the donor in a closed loop. The industry standard is for platelets to be tested for bacteria before transfusion to avoid septic reactions, which can be fatal. Recently the AABB Industry Standards for

Platelets are either isolated from collected units of whole blood and pooled to make a therapeutic dose, or collected by platelet apheresis: blood is taken from the donor, passed through a device which removes the platelets, and the remainder is returned to the donor in a closed loop. The industry standard is for platelets to be tested for bacteria before transfusion to avoid septic reactions, which can be fatal. Recently the AABB Industry Standards for Blood Banks

A blood bank is a center where blood gathered as a result of blood donation is stored and preserved for later use in blood transfusion. The term "blood bank" typically refers to a department of a hospital usually within a Clinical Pathology laborat ...

and Transfusion Services (5.1.5.1) has allowed for use of pathogen reduction technology as an alternative to bacterial screenings in platelets.

Pooled whole-blood platelets, sometimes called "random" platelets, are separated by one of two methods.centrifuge

A centrifuge is a device that uses centrifugal force to separate various components of a fluid. This is achieved by spinning the fluid at high speed within a container, thereby separating fluids of different densities (e.g. cream from milk) or ...

in what is referred to as a "soft spin". At these settings, the platelets remain suspended in the plasma. The platelet-rich plasma

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), also known as autologous conditioned plasma, is a concentrate of platelet-rich plasma protein derived from whole blood, centrifuged to remove red blood cells. Though promoted to treat an array of medical problems, evid ...