The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within

Western Christianity

Western Christianity is one of two sub-divisions of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, ūÖųĄū®ūüūĢų╝ūóųĘ, translit=Y─ ...

in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and in particular to

papal authority, arising from what were perceived to be

errors, abuses, and discrepancies by the Catholic Church. The Reformation was the start of

Protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

and the split of the Western Church into Protestantism and what is now the Roman Catholic Church. It is also considered to be one of the events that signified the end of the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

and the beginning of the

early modern period in Europe.

[Davies ''Europe'' pp. 291ŌĆō293]

Prior to

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 ŌĆō 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Luther ...

, there were many

earlier reform movements. Although the Reformation is usually considered to have started with the publication of the ''

Ninety-five Theses'' by Martin Luther in 1517, he was not

excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

by

Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

until January 1521. The

Diet of Worms of May 1521 condemned Luther and officially banned citizens of the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

from defending or propagating his ideas.

[Fahlbusch, Erwin, and Bromiley, Geoffrey William (2003). ''The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 3''. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. p. 362.] The spread of

Gutenberg's printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

provided the means for the rapid dissemination of religious materials in the vernacular. Luther survived after being declared an outlaw due to the protection of Elector

Frederick the Wise. The initial movement in Germany diversified, and other reformers such as

Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 ŌĆō 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Uni ...

and

John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

arose. In general, the Reformers argued that

salvation in Christianity

In Christianity, salvation (also called deliverance or redemption) is the "saving fhuman beings from sin and its consequences, which include death and separation from God" by Christ's death and resurrection, and the justification following t ...

was a completed status

based on faith in Jesus alone and not a process that requires

good works, as in the Catholic view. Key events of the period include:

Diet of Worms (1521), formation of the

Lutheran Duchy of Prussia (1525),

English Reformation (1529 onwards), the

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described ...

(1545ŌĆō63), the

Peace of Augsburg (1555), the

excommunication of Elizabeth I

''Regnans in Excelsis'' ("Reigning on High") is a papal bull that Pope Pius V issued on 25 February 1570. It excommunicated Queen Elizabeth I of England, referring to her as "the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime", declared h ...

(1570),

Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was signed in April 1598 by King Henry IV and granted the Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was in essence completely Catholic. In the edict, Henry aim ...

(1598) and

Peace of Westphalia (1648). The

Counter-Reformation, also called the ''Catholic Reformation'' or the ''Catholic Revival'', was the period of Catholic reforms initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. The end of the Reformation era is disputed among modern scholars.

Overview

Movements had been made towards a Reformation prior to Martin Luther, so some Protestants, such as

Landmark Baptists

A landmark is a recognizable natural or artificial feature used for navigation, a feature that stands out from its near environment and is often visible from long distances.

In modern use, the term can also be applied to smaller structures or ...

, and the tradition of the

Radical Reformation prefer to credit the start of the Reformation to reformers such as

Arnold of Brescia,

Peter Waldo,

John Wycliffe,

Jan Hus,

Petr Chel─Źick├Į, and

Girolamo Savonarola

Girolamo Savonarola, OP (, , ; 21 September 1452 ŌĆō 23 May 1498) or Jerome Savonarola was an Italian Dominican friar from Ferrara and preacher active in Renaissance Florence. He was known for his prophecies of civic glory, the destruction ...

. Due to the reform efforts of Hus and other

Bohemian reformers,

Utraquist Hussitism was

acknowledged by the

Council of Basel and was

officially tolerated in the

Crown of Bohemia, although other movements were still subject to persecution, including the

Lollards in England and the

Waldensians in France and Italian regions.

Luther began by criticising the sale of

indulgences, insisting that the Pope had no authority over

purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgat ...

and that the

Treasury of Merit had no foundation in the Bible. The Reformation developed further to include a distinction between

Law and Gospel, a complete reliance on Scripture as the only source of proper doctrine (''

sola scriptura'') and the belief that

faith in

Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, ūÖųĄū®ūüūĢų╝ūóųĘ, translit=Y─ō┼Ī┼½a╩┐, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

is the only way to receive God's pardon for sin (''

sola fide'') rather than good works. Although this is generally considered a Protestant belief, a similar formulation was taught by

Molinist

Molinism, named after 16th-century Spanish Jesuit priest and Roman Catholic theologian Luis de Molina, is the thesis that God has middle knowledge. It seeks to reconcile the apparent tension of divine providence and human free will. Prominent c ...

and

Jansenist Catholics. The

priesthood of all believers downplayed the need for saints or priests to serve as mediators, and mandatory

clerical celibacy was ended. ''

Simul justus et peccator'' implied that although people could improve, no one could become good enough to earn forgiveness from God. Sacramental theology was simplified and attempts at imposing Aristotelian epistemology were resisted.

Luther and his followers did not see these theological developments as changes. The 1530 ''

Augsburg Confession'' concluded that "in doctrine and ceremonies nothing has been received on our part against Scripture or the Church Catholic", and even after the ''Council of Trent'',

Martin Chemnitz published the 1565ŌĆō73 ''

Examination of the Council of Trent'' as an attempt to prove that Trent innovated on doctrine while the Lutherans were following in the footsteps of the Church Fathers and Apostles.

The initial movement in Germany diversified, and other reformers arose independently of Luther such as

Zwingli in

Z├╝rich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, D├╝bendorf, F├żllanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, R├╝mlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Z├╝rich () i ...

and John

Calvin Calvin may refer to:

Names

* Calvin (given name)

** Particularly Calvin Coolidge, 30th President of the United States

* Calvin (surname)

** Particularly John Calvin, theologian

Places

In the United States

* Calvin, Arkansas, a hamlet

* Calvin T ...

in Geneva. Depending on the country, the Reformation had varying causes and different backgrounds and also unfolded differently than in Germany. The spread of

Gutenberg's printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

provided the means for the rapid dissemination of religious materials in the vernacular.

During Reformation-era

confessionalization, Western Christianity adopted different confessions (

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

,

Lutheran,

Reformed,

Anglican,

Anabaptist,

Unitarian

Unitarian or Unitarianism may refer to:

Christian and Christian-derived theologies

A Unitarian is a follower of, or a member of an organisation that follows, any of several theologies referred to as Unitarianism:

* Unitarianism (1565ŌĆōpresent ...

, etc.). Radical Reformers, besides forming communities outside

state sanction, sometimes employed more extreme doctrinal change, such as the rejection of the

tenets of the councils of

Nicaea and

Chalcedon with the Unitarians of

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erd├®ly; german: Siebenb├╝rgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the ...

.

Anabaptist movements were especially persecuted following the

German Peasants' War.

Leaders within the Roman Catholic Church responded with the

Counter-Reformation, initiated by the ''

Confutatio Augustana'' in 1530, the ''

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described ...

'' in 1545, the formation of the

Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuit├”), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

in 1540, the

Defensio Tridentin├” fidei in 1578, and also a series of wars and expulsions of Protestants that continued until the 19th century. Northern Europe, with the exception of most of Ireland, came under the influence of Protestantism. Southern Europe remained predominantly Catholic apart from the much-persecuted

Waldensians. Central Europe was the site of much of the

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battl ...

and there were continued expulsions of Protestants in Central Europe up to the 19th century. Following World War II, the removal of ethnic Germans to either East Germany or Siberia reduced Protestantism in the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

countries, although some remain today.

The absence of Protestants, however, does not necessarily imply a failure of the Reformation. Although Protestants were excommunicated and ended up worshipping in communions separate from Catholics (contrary to the original intention of the Reformers), they were also suppressed and persecuted in most of Europe at one point. As a result, some of them lived as

crypto-Protestants, also called

Nicodemites, contrary to the urging of John Calvin, who wanted them to live their faith openly. Some

crypto-Protestants have been identified as late as the 19th century after immigrating to Latin America.

History

Origins and early history

Earlier reform movements

John Wycliffe questioned the privileged status of the clergy which had bolstered their powerful role in England and the luxury and pomp of local parishes and their ceremonies. He was accordingly characterised as the "evening star" of

scholasticism and as the

morning star

Morning Star, morning star, or Morningstar may refer to:

Astronomy

* Morning star, most commonly used as a name for the planet Venus when it appears in the east before sunrise

** See also Venus in culture

* Morning star, a name for the star Siri ...

or of the

English Reformation. In 1374,

Catherine of Siena began travelling with her followers throughout northern and central Italy advocating reform of the clergy and advising people that repentance and renewal could be done through "the total love for God." She carried on a long correspondence with

Pope Gregory XI, asking him to reform the clergy and the administration of the

Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct Sovereignty, sovereign rule of ...

. The oldest Protestant churches, such as the

Moravian Church, date their origins to

Jan Hus (John Huss) in the early 15th century. As it was led by a Bohemian noble majority, and recognised, for some time, by the Basel Compacts, the Hussite Reformation was Europe's first "

Magisterial Reformation" because the ruling magistrates supported it, unlike the "

Radical Reformation", which the state did not support.

Common factors that played a role during the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation included the rise of the

printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

,

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

,

simony, the appointment of

Cardinal-nephews, and other corruption of the

Roman Curia and other ecclesiastical hierarchy, the impact of

humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

, the new learning of the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

versus

scholasticism, and the

Western Schism that eroded loyalty to the

Papacy. Unrest due to the

Great Schism of Western Christianity (1378ŌĆō1416) excited wars between princes, uprisings among the peasants, and widespread concern over corruption in the Church, especially from

John Wycliffe at

Oxford University and from

Jan Hus at the

Charles University in Prague

)

, image_name = Carolinum_Logo.svg

, image_size = 200px

, established =

, type = Public, Ancient

, budget = 8.9 billion CZK

, rector = Milena Kr├Īl├Ł─Źkov├Ī

, faculty = 4,057

, administrative_staff = 4,026

, students = 51,438

, undergr ...

.

Hus objected to some of the practices of the Roman Catholic Church and wanted to return the church in

Bohemia and

Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, M├żhren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

Th ...

to earlier practices:

liturgy in the language of the people (i.e. Czech), having lay people receive

communion in both kinds (bread ''and'' wineŌĆöthat is, in Latin,

communio sub utraque specie), married priests, and eliminating

indulgences and the concept of

purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgat ...

. Some of these, like the use of local language as the liturgical language, were approved by the pope as early as in the 9th century.

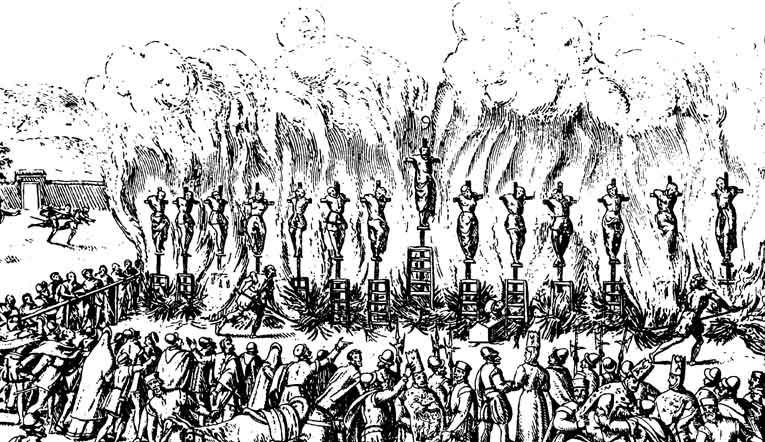

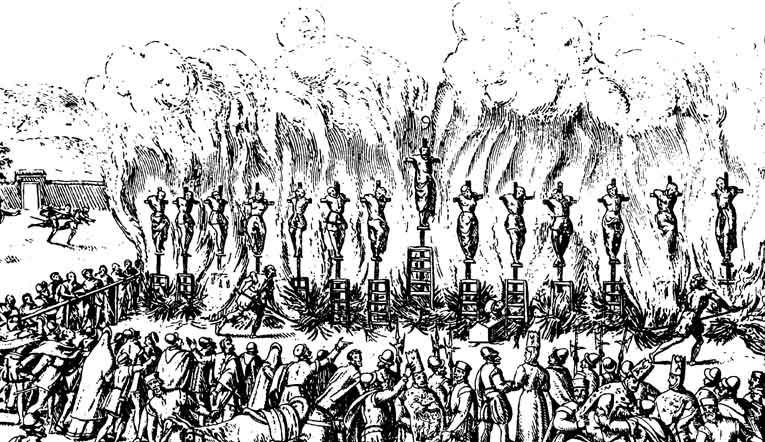

The leaders of the Roman Catholic Church condemned him at the

Council of Constance (1414ŌĆō1417) and he was burnt at the stake, despite a promise of safe-conduct.

[Oberman and Walliser-Schwarzbart ]

Luther: Man between God and the Devil

' pp. 54ŌĆō55 Wycliffe was posthumously condemned as a heretic and his corpse exhumed and burned in 1428. The Council of Constance confirmed and strengthened the traditional medieval conception of church and empire. The council did not address the national tensions or the theological tensions stirred up during the previous century and could not prevent

schism and the

Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, European monarchs loyal to the ...

in Bohemia.

Pope Sixtus IV (1471ŌĆō1484) established the practice of selling indulgences to be applied to the dead, thereby establishing a new stream of revenue with agents across Europe.

(1492ŌĆō1503) was one of the most controversial of the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

popes. He was the father of seven children, including

Lucrezia and

Cesare Borgia. In response to papal corruption, particularly the sale of indulgences, Luther wrote ''The Ninety-Five Theses''.

A number of theologians in the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

preached reformation ideas in the 1510s, shortly before or simultaneously with Luther, including

Christoph Schappeler in

Memmingen (as early as 1513).

Magisterial Reformation

The Reformation is usually dated to 31 October 1517 in

Wittenberg, Saxony, when Luther sent his ''

Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences'' to the

Archbishop of Mainz. The theses

debate

Debate is a process that involves formal discourse on a particular topic, often including a moderator and audience. In a debate, arguments are put forward for often opposing viewpoints. Debates have historically occurred in public meetings, ac ...

d and criticised the Church and the papacy, but concentrated upon the selling of indulgences and doctrinal policies about

purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgat ...

,

particular judgment

Particular judgment, according to Christian eschatology, is the divine judgment that a departed person undergoes immediately after death, in contradistinction to the general judgment (or Last Judgment) of all people at the end of the world.

...

, and the authority of the pope. He would later in the period 1517ŌĆō1521 write works on devotion to

Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ▄Ī▄¬▄Ø▄Ī, translit=Mariam; ar, ┘ģž▒┘Ŗ┘ģ, translit=Maryam; grc, ╬£╬▒Žü╬»╬▒, translit=Mar├Ła; la, Maria; cop, Ō▓śŌ▓üŌ▓ŻŌ▓ōŌ▓ü, translit=Maria was a first-century Jews, Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Jose ...

, the intercession of and devotion to the saints, the sacraments, mandatory clerical celibacy, and later on the authority of the pope, the ecclesiastical law, censure and excommunication, the role of secular rulers in religious matters, the relationship between Christianity and the law,

good works, and monasticism.

[Schofield ''Martin Luther'' p. 122] Some nuns, such as

Katharina von Bora and

Ursula of Munsterberg

Ursula of Munsterberg (german: Ursula von M├╝nsterberg; cs, Ur┼Īula z Minstrberka, Vor┼Īila Minstrbersk├Ī, kn─ø┼Šna a Kladsk├Ī hrab─ønka; c. 1491/95 or 1499,Cf. Siegismund Justus Ehrhardt: ''Abhandlung vom verderbten Religions-Zustand in Schlesien ...

, left the monastic life when they accepted the Reformation, but other orders adopted the Reformation, as Lutherans continue to have

monasteries today. In contrast, Reformed areas typically secularised monastic property.

Reformers and their opponents made heavy use of inexpensive pamphlets as well as vernacular Bibles using the relatively new printing press, so there was swift movement of both ideas and documents.

[Rubin, "Printing and Protestants" Review of Economics and Statistics pp. 270ŌĆō286][Atkinson Fitzgerald "Printing, Reformation and Information Control" ''Short History of Copyright'' pp. 15ŌĆō22] Magdalena Heymair printed pedagogical writings for teaching children Bible stories.

Parallel to events in Germany, a movement began in

Switzerland under the leadership of

Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 ŌĆō 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Uni ...

. These two movements quickly agreed on most issues, but some unresolved differences kept them separate. Some followers of Zwingli believed that the Reformation was too conservative, and moved independently toward more radical positions, some of which survive among modern day

Anabaptists.

After this first stage of the Reformation, following the

excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

of Luther in ''

Decet Romanum Pontificem'' and the condemnation of his followers by the edicts of the 1521 Diet of Worms, the work and writings of

John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

were influential in establishing a loose consensus among various churches in Switzerland,

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to th ...

, Hungary, Germany and elsewhere.

Although the

German Peasants' War of 1524ŌĆō1525 began as a tax and anti-corruption protest as reflected in the

Twelve Articles, its leader

Thomas M├╝ntzer gave it a radical Reformation character. It swept through the Bavarian,

Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Th├╝ringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and lar ...

n and

Swabian principalities, including the

Black Company of

Florian Geier, a knight from

Giebelstadt who joined the peasants in the general outrage against the Catholic hierarchy. In response to reports about the destruction and violence, Luther condemned the revolt in writings such as ''

Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants

''Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants'' (german: link=no, Wider die Mordischen und Reubischen Rotten der Bawren) is a piece written by Martin Luther in response to the German Peasants' War. Beginning in 1524 and ending in 1525, t ...

''; Zwingli and Luther's ally

Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 ŌĆō 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the L ...

also did not condone the uprising. Some 100,000 peasants were killed by the end of the war.

Radical Reformation

The Radical Reformation was the response to what was believed to be the corruption in both the Roman Catholic Church and the

Magisterial Reformation. Beginning in Germany and Switzerland in the 16th century, the Radical Reformation developed radical Protestant churches throughout Europe. The term includes

Thomas M├╝ntzer,

Andreas Karlstadt, the

Zwickau prophets, and

Anabaptists like the

Hutterites

Hutterites (german: link=no, Hutterer), also called Hutterian Brethren (German: ), are a communal ethnoreligious branch of Anabaptists, who, like the Amish and Mennonites, trace their roots to the Radical Reformation of the early 16th century ...

and

Mennonites.

In parts of Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, a majority sympathised with the Radical Reformation despite intense persecution.

Although the surviving proportion of the European population that rebelled against Catholic,

Lutheran and

Zwinglian churches was small, Radical Reformers wrote profusely and the literature on the Radical Reformation is disproportionately large, partly as a result of the proliferation of the Radical Reformation teachings in the United States.

Despite significant diversity among the early Radical Reformers, some "repeating patterns" emerged among many Anabaptist groups. Many of these patterns were enshrined in the

''Schleitheim Confession'' (1527) and include

believers' (or adult) baptism, memorial view of the

Lord's Supper, belief that Scripture is the final authority on matters of faith and practice, emphasis on the

New Testament

The New Testament grc, ß╝® ╬Ü╬▒╬╣╬ĮßĮ┤ ╬ö╬╣╬▒╬Ė╬«╬║╬Ę, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

and the

Sermon on the Mount, interpretation of Scripture in community, separation from the world and a

two-kingdom theology,

pacifism and

nonresistance, communal ownership and economic sharing, belief in the freedom of the will, non-swearing of oaths, "yieldedness" (''Gelassenheit'') to one's community and to God, the

ban

Ban, or BAN, may refer to:

Law

* Ban (law), a decree that prohibits something, sometimes a form of censorship, being denied from entering or using the place/item

** Imperial ban (''Reichsacht''), a form of outlawry in the medieval Holy Roman ...

(i.e., shunning), salvation through divinization (''Verg├Čttung'') and ethical living, and discipleship (''Nachfolge Christi'').

Literacy

The Reformation was a triumph of literacy and the new printing press.

into German was a decisive moment in the spread of literacy, and stimulated as well the printing and distribution of religious books and pamphlets. From 1517 onward, religious pamphlets flooded Germany and much of Europe.

[Edwards ''Printing, Propaganda, and Martin Luther'']

By 1530, over 10,000 publications are known, with a total of ten million copies. The Reformation was thus a media revolution. Luther strengthened his attacks on Rome by depicting a "good" against "bad" church. From there, it became clear that print could be used for propaganda in the Reformation for particular agendas, although the term propaganda derives from the Catholic ''

Congregatio de Propaganda Fide'' (''Congregation for Propagating the Faith'') from the Counter-Reformation. Reform writers used existing styles, cliches and stereotypes which they adapted as needed.

Especially effective were writings in German, including Luther's translation of the Bible, his

Smaller Catechism for parents teaching their children, and his

Larger Catechism, for pastors.

Using the German vernacular they expressed the Apostles' Creed in simpler, more personal, Trinitarian language. Illustrations in the German Bible and in many tracts popularised Luther's ideas.

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472ŌĆō1553), the great painter patronised by the electors of Wittenberg, was a close friend of Luther, and he illustrated Luther's theology for a popular audience. He dramatised Luther's views on the relationship between the Old and New Testaments, while remaining mindful of Luther's careful distinctions about proper and improper uses of visual imagery.

[Weimer "Luther and Cranach" ''Lutheran Quarterly'' pp. 387ŌĆō405]

Causes of the Reformation

The following

supply-side factors have been identified as causes of the Reformation:

* The presence of a

printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

in a city by 1500 made Protestant adoption by 1600 far more likely.

* Protestant literature was produced at greater levels in cities where media markets were more competitive, making these cities more likely to adopt Protestantism.

* Ottoman incursions decreased conflicts between Protestants and Catholics, helping the Reformation take root.

* Greater political autonomy increased the likelihood that Protestantism would be adopted.

* Where Protestant reformers enjoyed princely patronage, they were much more likely to succeed.

* Proximity to neighbours who adopted Protestantism increased the likelihood of adopting Protestantism.

* Cities that had higher numbers of students enrolled in heterodox universities and lower numbers enrolled in orthodox universities were more likely to adopt Protestantism.

The following demand-side factors have been identified as causes of the Reformation:

* Cities with strong cults of saints were less likely to adopt Protestantism.

* Cities where

primogeniture was practised were less likely to adopt Protestantism.

* Regions that were poor but had great economic potential and bad political institutions were more likely to adopt Protestantism.

* The presence of bishoprics made the adoption of Protestantism less likely.

* The presence of monasteries made the adoption of Protestantism less likely.

A 2020 study linked the spread of Protestantism to personal ties to Luther (e.g. letter correspondents, visits, former students) and trade routes.

Reformation in Germany

In 1517, Luther nailed the ''Ninety-five theses'' to the Castle Church door, and without his knowledge or prior approval, they were copied and printed across Germany and internationally. Different reformers arose more or less independently of Luther in 1518 (for example

Andreas Karlstadt,

Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 ŌĆō 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran Protestant Reformers, reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellect ...

,

Erhard Schnepf,

Johannes Brenz and

Martin Bucer) and in 1519 (for example

Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 ŌĆō 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Uni ...

,

Nikolaus von Amsdorf

Nicolaus von Amsdorf (German: Nikolaus von Amsdorf, 3 December 1483 ŌĆō 14 May 1565) was a German Lutheran theologian and an early Protestant reformer. As bishop of Naumburg (1542ŌĆō1546), he became the first Lutheran bishop in the Holy Roman E ...

,

Ulrich von Hutten), and so on.

After the

Heidelberg Disputation (1518) where Luther described the

Theology of the Cross as opposed to the Theology of Glory and the

Leipzig Disputation

The Leipzig Debate (german: Leipziger Disputation) was a theological disputation originally between Andreas Karlstadt, Martin Luther and Johann Eck. Karlstadt, the dean of the Wittenberg theological faculty, felt that he had to defend Luthe ...

(1519), the faith issues were brought to the attention of other German theologians throughout the Empire. Each year drew new theologians to embrace the Reformation and participate in the ongoing, European-wide discussion about faith. The pace of the Reformation proved unstoppable by 1520.

The early Reformation in Germany mostly concerns the life of Martin Luther until he was excommunicated by Pope Leo X on 3 January 1521, in the bull ''

Decet Romanum Pontificem''. The exact moment

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 ŌĆō 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Luther ...

realised the key doctrine of

Justification by Faith is described in German as the ''

Turmerlebnis''. In ''

Table Talk'', Luther describes it as a sudden realization. Experts often speak of a gradual process of realization between 1514 and 1518.

Reformation ideas and Protestant church services were first introduced in cities, being supported by local citizens and also some nobles. The Reformation did not receive overt state support until 1525, although it was only due to the protection of Elector

Frederick the Wise (who had a strange dream the night prior to 31 October 1517) that Luther survived after being declared an outlaw, in hiding

at Wartburg Castle and then

returning to Wittenberg. It was more of a movement among the German people between 1517 and 1525, and then also a political one beginning in 1525. Reformer

Adolf Clarenbach was burned at the stake near Cologne in 1529.

The first state to formally adopt a

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

confession was the

Duchy of Prussia (1525).

Albert, Duke of Prussia formally declared the "Evangelical" faith to be the

state religion. Catholics

labeled self-identified Evangelicals "Lutherans" to discredit them after the practice of naming a heresy after its founder. However, the

Lutheran Church traditionally sees itself as the "main trunk of the historical Christian Tree" founded by Christ and the Apostles, holding that during the Reformation, the

Church of Rome fell away.

Ducal Prussia was followed by many

imperial free cities and other minor

imperial entities. The next sizable territories were the

Landgraviate of Hesse (1526; at the

Synod of Homberg) and the

Electorate of Saxony (1527; Luther's homeland),

Electoral Palatinate

The Electoral Palatinate (german: Kurpfalz) or the Palatinate (), officially the Electorate of the Palatinate (), was a state that was part of the Holy Roman Empire. The electorate had its origins under the rulership of the Counts Palatine of ...

(1530s), and the

Duchy of W├╝rttemberg (1534). For a more complete list, see the

list of states by the date of adoption of the Reformation and the table of the

adoption years for the Augsburg Confession. The reformation wave swept first the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

, and then extended beyond it to the rest of the European continent.

Germany was home to the greatest number of

Protestant reformers. Each state which turned Protestant had their own reformers who contributed towards the ''Evangelical'' faith. In

Electoral Saxony the

Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Saxony

The Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Saxony (''Evangelisch-Lutherische Landeskirche Sachsens'') is one of 20 member Churches of the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD), covering most of the state of Saxony. Its headquarters are in Dresden, and its b ...

was organised and served as an example for other states, although Luther was not dogmatic on questions of polity.

Reformation outside Germany

The Reformation also spread widely throughout Europe, starting with Bohemia, in the Czech lands, and, over the next few decades, to other countries.

Austria

Austria followed the same pattern as the

German-speaking

German ( ) is a West Germanic language mainly spoken in Central Europe. It is the most widely spoken and official or co-official language in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the Italian province of South Tyrol. It is a ...

states within the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

, and Lutheranism became the main Protestant confession among its population.

Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

gained a significant following in the eastern half of present-day Austria, while

Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

was less successful. Eventually the expulsions of the

Counter-Reformation reversed the trend.

Czech lands

The

Hussites were a Christian movement in the

Kingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia ( cs, ─īesk├® kr├Īlovstv├Ł),; la, link=no, Regnum Bohemiae sometimes in English literature referred to as the Czech Kingdom, was a medieval and early modern monarchy in Central Europe, the predecessor of the modern Czec ...

following the teachings of Czech reformer

Jan Hus.

=Jan Hus

=

Czech reformer and university professor

Jan Hus (c. 1369ŌĆō1415) became the best-known representative of the Bohemian Reformation and one of the forerunners of the Protestant Reformation.

Jan Hus was declared a heretic and executedŌĆöburned at stakeŌĆöat the

Council of Constance in 1415 where he arrived voluntarily to defend his teachings.

=Hussite movement

=

This predominantly religious movement was propelled by social issues and strengthened Czech national awareness. In 1417, two years after the execution of Jan Hus, the Czech reformation quickly became the chief force in the country.

Hussites made up the vast majority of the population, forcing the Council of Basel to recognize in 1437 a system of two "religions" for the first time, signing the

Compacts of Basel The Compacts of Basel, also known as Basel Compacts or ''Compactata'', was an agreement between the Council of Basel and the moderate Hussites (or Utraquists), which was ratified by the Estates of Bohemia and Moravia in Jihlava on 5 July 1436. The a ...

for the kingdom (Catholic and Czech

Ultraquism a Hussite movement). Bohemia later also elected two Protestant kings (

George of Pod─øbrady,

Frederick of Palatine).

After

Habsburgs took control of the region, the Hussite churches were prohibited and the kingdom partially recatholicised. Even later,

Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

gained a substantial following, after being permitted by the Habsburgs with the continued persecution of the Czech native Hussite churches. Many Hussites thus declared themselves Lutherans.

Two churches with Hussite roots are now the second and third biggest churches among the largely agnostic peoples:

Czech Brethren (which gave origin to the international church known as the

Moravian Church) and the

Czechoslovak Hussite Church.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, the teachings of the reformers and especially those of Zwingli and Calvin had a profound effect, despite frequent quarrels between the different branches of the Reformation.

= Huldrych Zwingli

=

Parallel to events in Germany, a movement began in the

Swiss Confederation under the leadership of Huldrych Zwingli. Zwingli was a scholar and preacher who moved to

Z├╝rich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, D├╝bendorf, F├żllanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, R├╝mlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Z├╝rich () i ...

ŌĆöthe then-leading city stateŌĆöin 1518, a year after Martin Luther began the Reformation in Germany with his

Ninety-five Theses. Although the two movements agreed on many issues of theology, as the recently introduced

printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

spread ideas rapidly from place to place, some unresolved differences kept them separate. Long-standing resentment between the German states and the Swiss Confederation led to heated debate over how much Zwingli owed his ideas to Lutheranism. Although

Zwinglianism does hold uncanny resemblance to Lutheranism (it even had its own equivalent of the ''Ninety-five Theses'', called the 67 Conclusions), historians have been unable to prove that Zwingli had any contact with Luther's publications before 1520, and Zwingli himself maintained that he had prevented himself from reading them.

The German Prince

Philip of Hesse saw potential in creating an alliance between Zwingli and Luther, seeing strength in a united Protestant front. A meeting was held in his castle in 1529, now known as the

Colloquy of Marburg, which has become infamous for its complete failure. The two men could not come to any agreement due to their disputation over one key doctrine. Although Luther preached

consubstantiation in the

Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was institu ...

over

transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (Latin: ''transubstantiatio''; Greek: ╬╝╬ĄŽä╬┐ŽģŽā╬»ŽēŽā╬╣Žé '' metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of ...

, he believed in the

real presence of Christ

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

There are a number of Christian denominati ...

in the Communion bread. Zwingli, inspired by Dutch theologian

Cornelius Hoen, believed that the Communion bread was only representative and memorialŌĆöChrist was not present. Luther became so angry that he famously carved into the meeting table in chalk ''Hoc Est Corpus Meum''ŌĆöa Biblical quotation from the

Last Supper meaning "This is my body". Zwingli countered this saying that ''est'' in that context was the equivalent of the word ''significat'' (signifies).

Some followers of Zwingli believed that the Reformation was too conservative and moved independently toward more radical positions, some of which survive among modern day

Anabaptists. One famous incident illustrating this was when radical Zwinglians fried and ate sausages during Lent in Zurich city square by way of protest against the Church teaching of

good works. Other Protestant movements grew up along the lines of mysticism or humanism (cf.

Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' w ...

and

Louis de Berquin who was martyred in 1529), sometimes breaking from Rome or from the Protestants, or forming outside of the churches.

= John Calvin

=

Following the

excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

of Luther and condemnation of the Reformation by the Pope, the work and writings of John Calvin were influential in establishing a loose consensus among various churches in Switzerland,

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to th ...

, Hungary, Germany and elsewhere. After the expulsion of its Bishop in 1526, and the unsuccessful attempts of the Berne reformer

Guillaume (William) Farel, Calvin was asked to use the organisational skill he had gathered as a student of law to discipline the "fallen city" of Geneva. His "Ordinances" of 1541 involved a collaboration of Church affairs with the City council and

consistory to bring morality to all areas of life. After the establishment of the Geneva academy in 1559, Geneva became the unofficial capital of the Protestant movement, providing refuge for Protestant exiles from all over Europe and educating them as Calvinist missionaries. These missionaries dispersed Calvinism widely, and formed the French

Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Bez ...

in Calvin's own lifetime and spread to Scotland under the leadership of

John Knox in 1560.

Anne Locke translated some of Calvin's writings to English around this time. The faith continued to spread after Calvin's death in 1563 and reached as far as Constantinople by the start of the 17th century.

The Reformation foundations engaged with

Augustinianism. Both Luther and Calvin thought along lines linked with the theological teachings of

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 ŌĆō 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North A ...

. The Augustinianism of the Reformers struggled against

Pelagianism

Pelagianism is a Christian theological position that holds that the original sin did not taint human nature and that humans by divine grace have free will to achieve human perfection. Pelagius ( ŌĆō AD), an ascetic and philosopher from t ...

, a heresy that they perceived in the Catholic Church of their day. Ultimately, since Calvin and Luther disagreed strongly on certain matters of theology (such as double-predestination and Holy Communion), the relationship between Lutherans and Calvinists was one of conflict.

Nordic countries

All of

Scandinavia

Scandinavia; S├Īmi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

ultimately adopted Lutheranism over the course of the 16th century, as the monarchs of Denmark (who also ruled Norway and Iceland) and Sweden (who also ruled Finland) converted to that faith.

=Sweden

=

In Sweden, the Reformation was spearheaded by

Gustav Vasa

Gustav I, born Gustav Eriksson of the Vasa noble family and later known as Gustav Vasa (12 May 1496 ŌĆō 29 September 1560), was King of Sweden from 1523 until his death in 1560, previously self-recognised Protector of the Realm ('' Riksf├Čr ...

, elected king in 1523, with major contributions by

Olaus Petri, a Swedish clergyman. Friction with the pope over the latter's interference in Swedish ecclesiastical affairs led to the discontinuance of any official connection between Sweden and the papacy since 1523. Four years later, at the

Diet of V├żster├źs, the king succeeded in forcing the diet to accept his dominion over the national church. The king was given possession of all church property, church appointments required royal approval, the clergy were subject to the civil law, and the "pure Word of God" was to be preached in the churches and taught in the schoolsŌĆöeffectively granting official sanction to Lutheran ideas. The

apostolic succession was retained in Sweden during the Reformation. The adoption of Lutheranism was also one of the main reasons for the eruption of the

Dacke War, a peasants uprising in Sm├źland.

=Finland

=

= Denmark

=

Under the reign of

Frederick I (1523ŌĆō33), Denmark remained officially Catholic. Frederick initially pledged to persecute Lutherans, yet he quickly adopted a policy of protecting Lutheran preachers and reformers, of whom the most famous was

Hans Tausen. During his reign, Lutheranism made significant inroads among the Danish population. In 1526, Frederick forbade papal investiture of bishops in Denmark and in 1527 ordered fees from new bishops be paid to the crown, making Frederick the head of the church of Denmark. Frederick's son, Christian, was openly Lutheran, which prevented his election to the throne upon his father's death. In 1536, following his victory in the

Count's War, he became king as

Christian III and continued the

Reformation of the state church with assistance from

Johannes Bugenhagen. By the Copenhagen recess of October 1536, the authority of the Catholic bishops was terminated.

= Faroe Islands

=

= Iceland

=

Luther's influence had already reached

Iceland

Iceland ( is, ├Źsland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjav├Łk, which (along with its ...

before King Christian's decree. The

Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

fished near Iceland's coast, and the

Hanseatic League engaged in commerce with the Icelanders. These Germans raised a Lutheran church in

Hafnarfj├Čr├░ur as early as 1533. Through German trade connections, many young

Icelanders studied in

Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

. In 1538, when the kingly decree of the new Church ordinance reached Iceland, bishop

Ûgmundur and his clergy denounced it, threatening excommunication for anyone subscribing to the German "heresy".

[J├│n R. Hj├Īlmarsson, ''History of Iceland: From the Settlement to the Present Day'', (Iceland Review, 1993), p. 70.] In 1539, the King sent a new governor to Iceland,

Klaus von Mervitz

Klaus is a German, Dutch and Scandinavian given name and surname. It originated as a short form of Nikolaus, a German form of the Greek given name Nicholas.

Notable persons whose family name is Klaus

* Billy Klaus (1928ŌĆō2006), American baseb ...

, with a mandate to introduce reform and take possession of church property.

Von Mervitz seized a monastery in

Vi├░ey with the help of his sheriff,

Dietrich of Minden

Dietrich () is an ancient German name meaning "Ruler of the People.ŌĆØ Also "keeper of the keys" or a "lockpick" either the tool or the profession.

Given name

* Dietrich, Count of Oldenburg (c. 1398 ŌĆō 1440)

* Thierry of Alsace (german: Dietric ...

, and his soldiers. They drove the monks out and seized all their possessions, for which they were promptly excommunicated by Ûgmundur.

United Kingdom

=England

=

Church of England

The separation of the Church of England from Rome under

Henry VIII, beginning in 1529 and completed in 1537, brought England alongside this broad Reformation movement. Although

Robert Barnes attempted to get Henry VIII to adopt Lutheran theology, he refused to do so in 1538 and burned him at the stake in 1540. Reformers in the Church of England alternated, for decades, between sympathies between Catholic tradition and Reformed principles, gradually developing, within the context of robustly Protestant doctrine, a tradition considered a middle way (''

via media'') between the Catholic and Protestant traditions.

The English Reformation followed a different course from the Reformation in continental Europe. There had long been a strong strain of

anti-clericalism. England had already given rise to the

Lollard movement of

John Wycliffe, which played an important part in inspiring the

Hussites in

Bohemia. Lollardy was suppressed and became an underground movement, so the extent of its influence in the 1520s is difficult to assess. The different character of the English Reformation came rather from the fact that it was driven initially by the political necessities of Henry VIII.

Henry had once been a sincere Catholic and had even authored a book strongly criticising Luther. His wife,

Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 ŌĆō 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

, bore him only a single child who survived infancy,

Mary. Henry strongly wanted a male heir, and many of his subjects might have agreed, if only because they wanted to avoid another dynastic conflict like the

Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455ŌĆō1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These wars were fought be ...

.

Refused an annulment of his marriage to Catherine, King Henry decided to remove the Church of England from the authority of Rome. In 1534, the

Act of Supremacy recognised Henry as "the only

Supreme Head on earth of the Church of England".

[Bray (ed.) ''Documents of the English Reformation'' pp. 113ŌĆō] Between 1535 and 1540, under

Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; 1485 ŌĆō 28 July 1540), briefly Earl of Essex, was an English lawyer and statesman who served as List of English chief ministers, chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the kin ...

, the policy known as the

Dissolution of the Monasteries was put into effect. The veneration of some

saints, certain pilgrimages and some pilgrim shrines were also attacked. Huge amounts of church land and property passed into the hands of the Crown and ultimately into those of the nobility and gentry. The vested interest thus created made for a powerful force in support of the dissolution.

There were some notable opponents to the Henrician Reformation, such as

Thomas More and Cardinal

John Fisher, who were executed for their opposition. There was also a growing party of reformers who were imbued with the Calvinistic, Lutheran and Zwinglian doctrines then current on the Continent. When Henry died he was succeeded by his Protestant son

Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 ŌĆō 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour ...

, who, through his empowered councillors (with the King being only nine years old at his succession and fifteen at his death) the Duke of Somerset and the Duke of Northumberland, ordered the destruction of images in churches, and the closing of the

chantries. Under Edward VI the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

moved closer to continental Protestantism.

Yet, at a popular level, religion in England was still in a state of flux. Following a brief Catholic restoration during the reign of Mary (1553ŌĆō1558), a loose consensus developed during the reign of

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, though this point is one of considerable debate among historians. This "

Elizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558ŌĆō1603). Implemented between 1559 and 1563, the settlement is considered the end of the ...

" largely formed

Anglicanism into a distinctive church tradition. The compromise was uneasy and was capable of veering between extreme

Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

on one hand and Catholicism on the other. But compared to the bloody and chaotic state of affairs in contemporary France, it was relatively successful, in part because Queen Elizabeth lived so long, until the Puritan Revolution or

English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642ŌĆō1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians ("Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of Kingdom of England, England's governanc ...

in the seventeenth century.

English dissenters

The success of the

Counter-Reformation on the Continent and the growth of a Puritan party dedicated to further Protestant reform polarised the

Elizabethan Age, although it was not until the 1640s that England underwent religious strife comparable to what its neighbours had suffered some generations before.

The early ''Puritan movement'' (late 16thŌĆō17th centuries) was Reformed (or

Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

) and was a movement for reform in the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

. Its origins lay in the discontent with the

Elizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558ŌĆō1603). Implemented between 1559 and 1563, the settlement is considered the end of the ...

. The desire was for the Church of England to resemble more closely the Protestant churches of Europe, especially

Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Gen├©ve ) frp, Gen├©va ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Z├╝rich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situ ...

. The Puritans objected to ornaments and ritual in the churches as

idolatrous (vestments, surplices, organs, genuflection), calling the vestments "

popish

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodo ...

pomp and rags" (see

Vestments controversy). They also objected to ecclesiastical courts. Their refusal to endorse completely all of the ritual directions and formulas of the ''

Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 ...

'', and the imposition of its liturgical order by legal force and inspection, sharpened Puritanism into a definite opposition movement.

The later Puritan movement, often referred to as

dissenters and

nonconformists, eventually led to the formation of various

Reformed denominations.

The most famous emigration to America was the migration of Puritan separatists from the Anglican Church of England. They fled first to Holland, and then later to America to establish the English

colony of Massachusetts in New England, which later became one of the original United States. These Puritan separatists were also known as "the

Pilgrims". After establishing a colony at

Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymout ...

(which became part of the colony of Massachusetts) in 1620, the Puritan pilgrims received a charter from the

King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Baili ...

that legitimised their colony, allowing them to do trade and commerce with merchants in England, in accordance with the principles of

mercantilism. The Puritans persecuted those of other religious faiths, for example,

Anne Hutchinson was banished to Rhode Island during the

Antinomian Controversy and

Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

Mary Dyer was hanged in Boston for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony.

[Rogers, Horatio, 2009. ]

Mary Dyer of Rhode Island: The Quaker Martyr That Was Hanged on Boston

' pp. 1ŌĆō2. BiblioBazaar, LLC She was one of the four executed Quakers known as the

Boston martyrs. Executions ceased in 1661 when

King Charles II explicitly forbade Massachusetts from executing anyone for professing Quakerism.

In 1647, Massachusetts passed a law prohibiting any

Jesuit Roman Catholic priests from entering territory under Puritan jurisdiction. Any suspected person who could not clear himself was to be banished from the colony; a second offence carried a death penalty.

The Pilgrims held radical Protestant disapproval of Christmas, and its celebration was outlawed in Boston from 1659 to 1681.

The ban was revoked in 1681 by the English-appointed governor

Edmund Andros, who also revoked a Puritan ban on festivities on Saturday nights.

Nevertheless, it was not until the mid-19th century that celebrating Christmas became fashionable in the Boston region.

= Wales

=

Bishop

Richard Davies and dissident Protestant cleric

John Penry introduced Calvinist theology to Wales. In 1588, the Bishop of Llandaff published the entire Bible in the

Welsh language

Welsh ( or ) is a Celtic language of the Brittonic subgroup that is native to the Welsh people. Welsh is spoken natively in Wales, by some in England, and in Y Wladfa (the Welsh colony in Chubut Province, Argentina). Historically, it has ...

. The translation had a significant impact upon the Welsh population and helped to firmly establish Protestantism among the

Welsh people

The Welsh ( cy, Cymry) are an ethnic group native to Wales. "Welsh people" applies to those who were born in Wales ( cy, Cymru) and to those who have Welsh ancestry, perceiving themselves or being perceived as sharing a cultural heritage and ...

. The Welsh Protestants used the model of the

Synod of Dort of 1618ŌĆō1619. Calvinism developed through the Puritan period, following the restoration of the monarchy under Charles II, and within Wales'

Calvinistic Methodist movement. However few copies of Calvin's writings were available before mid-19th century.

= Scotland

=

The Reformation in Scotland's case culminated ecclesiastically in the establishment of a church along

reformed lines, and politically in the triumph of English influence over that of France.

John Knox is regarded as the leader of the Scottish reformation.

The

Reformation Parliament of 1560 repudiated the pope's authority by the ''

Papal Jurisdiction Act 1560

The Papal Jurisdiction Act 1560 (c.2) is an Act of the Parliament of Scotland, Act of the Parliament of Scotland which is still in force. It declares that the Pope has no Temporal jurisdiction (papacy), jurisdiction in Scotland and prohibits any p ...

'', forbade the celebration of the

Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different element ...

and approved a

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

Confession of Faith

A creed, also known as a confession of faith, a symbol, or a statement of faith, is a statement of the shared beliefs of a community (often a religious community) in a form which is structured by subjects which summarize its core tenets.

The e ...

. It was made possible by a revolution against French hegemony under the regime of the

regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state ''pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy, ...

Mary of Guise, who had governed Scotland in the name of her absent daughter

Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 ŌĆō 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

(then also

Queen of France).

Although Protestantism triumphed relatively easily in Scotland, the exact form of Protestantism remained to be determined. The 17th century saw a complex struggle between

Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their na ...

(particularly the

Covenanters) and

Episcopalianism. The Presbyterians eventually won control of the

Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

, which went on to have an important influence on Presbyterian churches worldwide, but Scotland retained a relatively large

Episcopalian minority.

Estonia

France

Besides the Waldensians already present in France, Protestantism also spread in from German lands, where the Protestants were nicknamed ''

Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Bez ...

''; this eventually led to decades of civil warfare.

Though not personally interested in religious reform,

Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366ŌĆō1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414ŌĆō1450), reigned 1442ŌĆō1450

* Francis I of France (1494ŌĆō1547), King of France, reigned 1515ŌĆō1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe ...

(reigned 1515ŌĆō1547) initially maintained an attitude of tolerance, in accordance with his interest in the

humanist movement. This changed in 1534 with the

Affair of the Placards. In this act, Protestants denounced the

Catholic Mass in placards that appeared across France, even reaching the royal apartments. During this time as the issue of religious faith entered into the arena of politics, Francis came to view the movement as a threat to the kingdom's stability.

Following the Affair of the Placards, culprits were rounded up, at least a dozen heretics were put to death, and the persecution of Protestants increased. One of those who fled France at that time was John Calvin, who emigrated to Basel in 1535 before eventually settling in Geneva in 1536. Beyond the reach of the French kings in Geneva, Calvin continued to take an interest in the religious affairs of his native land including the training of ministers for congregations in France.

As the number of Protestants in France increased, the number of heretics in prisons awaiting trial also grew. As an experimental approach to reduce the caseload in Normandy, a special court just for the trial of heretics was established in 1545 in the

Parlement de Rouen

The Parliament of Normandy (''parlement de Normandie''), also known as the Parliament of Rouen (''parlement de Rouen'') after the place where it sat (the provincial capital of Normandy), was a provincial parlement of the Kingdom of France. It ...

. When

Henry II took the throne in 1547, the persecution of Protestants grew and special courts for the trial of heretics were also established in the Parlement de Paris. These courts came to known as

"''La Chambre Ardente''" ("the fiery chamber") because of their reputation of meting out death penalties on burning gallows.

Despite heavy persecution by Henry II, the

Reformed Church of France, largely

Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

in direction, made steady progress across large sections of the nation, in the urban

bourgeoisie and parts of the

aristocracy, appealing to people alienated by the obduracy and the complacency of the Catholic establishment.

French Protestantism, though its appeal increased under persecution, came to acquire a distinctly political character, made all the more obvious by the conversions of nobles during the 1550s. This established the preconditions for a series of destructive and intermittent conflicts, known as the

Wars of Religion. The civil wars gained impetus with the sudden death of

Henry II in 1559, which began a prolonged period of weakness for the French crown.

Atrocity and outrage became the defining characteristics of the time, illustrated at their most intense in the

St. Bartholomew's Day massacre

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre (french: Massacre de la Saint-Barth├®lemy) in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations and a wave of Catholic mob violence, directed against the Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants) during the French War ...

of August 1572, when the Catholic party killed between 30,000 and 100,000 Huguenots across France. The wars only concluded when

Henry IV, himself a former Huguenot, issued the

Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was signed in April 1598 by King Henry IV and granted the Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was in essence completely Catholic. In the edict, Henry aim ...

(1598), promising official toleration of the Protestant minority, but under highly restricted conditions. Catholicism remained the official state religion, and the fortunes of French Protestants gradually declined over the next century, culminating in Louis XIV's

Edict of Fontainebleau