The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of

Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

in the

Greater Antilles

The Greater Antilles ( es, Grandes Antillas or Antillas Mayores; french: Grandes Antilles; ht, Gwo Zantiy; jam, Grieta hAntiliiz) is a grouping of the larger islands in the Caribbean Sea, including Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and ...

archipelago of the

Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with

Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

, making Hispaniola one of only two Caribbean islands, along with

Saint Martin, that is shared by two

sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a polity, political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defin ...

s. The Dominican Republic is the second-largest nation in the

Antilles

The Antilles (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Antiy; es, Antillas; french: Antilles; nl, Antillen; ht, Antiy; pap, Antias; Jamaican Patois: ''Antiliiz'') is an archipelago bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the south and west, the Gulf of Mex ...

by area (after

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

) at , and third-largest by population, with approximately 10.7 million people (2022 est.), down from 10.8 million in 2020, of whom approximately 3.3 million live in the metropolitan area of

Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

, the capital city.

The official language of the country is

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

.

The native

Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

people had inhabited Hispaniola before the arrival of Europeans, dividing it into five chiefdoms.

They had constructed an advanced farming and hunting society, and were in the process of becoming an organized civilization.

The Taínos also inhabited Cuba,

Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

,

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

, and

the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

. The

Genoese mariner

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

explored and claimed the island for

Castile, landing there on his first voyage in 1492.

The

colony of Santo Domingo

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

became the site of the first permanent European settlement in the Americas and the first seat of Spanish colonial rule in the

New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

. It would also become the site to introduce importations of

enslaved Africans

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

to the Americas. In 1697, Spain recognized French dominion over the western third of the island, which became the independent state of

Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

in 1804.

After more than three hundred years of Spanish rule, the Dominican people declared independence in November 1821.

The leader of the independence movement,

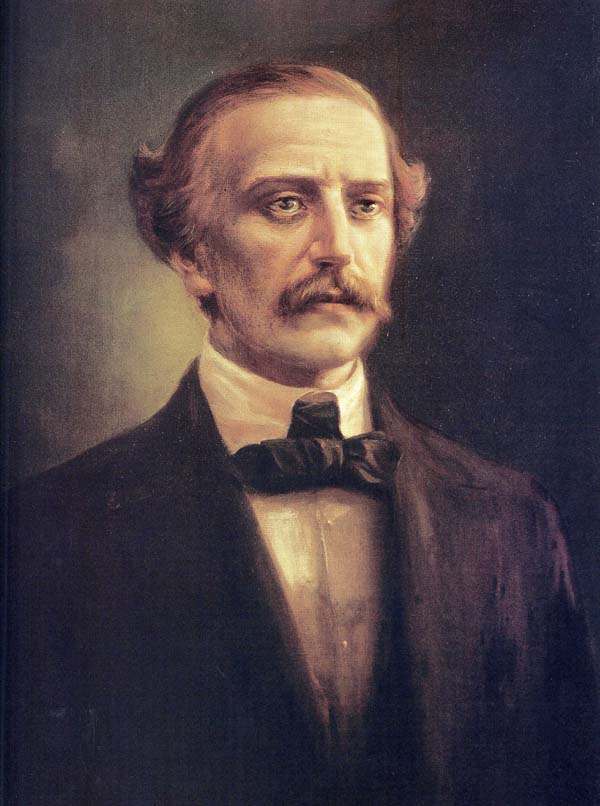

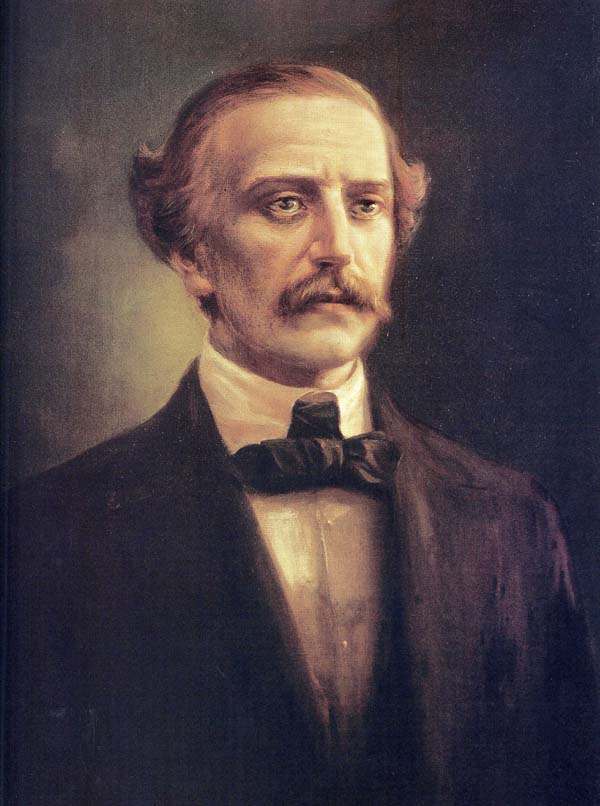

José Núñez de Cáceres

José Núñez de Cáceres y Albor (March 14, 1772 – September 11, 1846) was a Dominican politician and writer. He is known for being the leader of the independence movement against Spain in 1821 and the only president of the short-lived Repu ...

, intended the Dominican nation to unite with the country of

Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia (, "Great Colombia"), or Greater Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia (Spanish: ''República de Colombia''), was a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 18 ...

, but the newly independent Dominicans were forcefully annexed by Haiti in February 1822. Independence came 22 years later in 1844,

after victory in the

Dominican War of Independence

The Dominican War of Independence made the Dominican Republic a sovereign state on February 27, 1844. Before the war, the island of Hispaniola had been united for 22 years when the newly independent nation, previously known as the Captaincy Gen ...

. Over the next 72 years, the Dominican Republic experienced mostly civil wars (financed with loans from European merchants), several failed invasions by its neighbour, Haiti, and brief return to Spanish colonial status, before permanently ousting the Spanish during the

Dominican War of Restoration of 1863–1865. During this period, three presidents were assassinated (

José Antonio Salcedo

General José Antonio Salcedo y Ramírez, known as "Pepillo" (1816–1864) was a 19th-century President of the Dominican Republic.

Biography

Salcedo was born in Madrid, Spain from Criollo people, Criollo (white creole) parents of Spanish heri ...

in 1864,

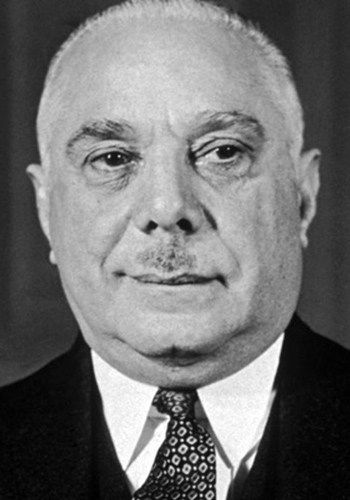

Ulises Heureaux

Ulises Hilarión Heureaux Leibert (; October 21, 1845 – July 26, 1899) nicknamed Lilís, was president of the Dominican Republic from September 1, 1882 to September 1, 1884, from January 6, 1887 to February 27, 1889 and again from April 30, 18 ...

in 1899, and

Ramón Cáceres

Ramón Arturo Cáceres Vasquez (15 December 1866, Moca, Dominican Republic – 19 November 1911, Santo Domingo), nicknamed Mon Cáceres, was a Dominican politician and minister of the Armed Forces. He was the 31st president of the Dominican Repu ...

in 1911).

The

U.S. occupied the Dominican Republic (1916–1924) due to threats of defaulting on foreign debts; a subsequent calm and prosperous six-year period under

Horacio Vásquez

Felipe Horacio Vásquez Lajara (October 22, 1860 – March 25, 1936) was a Dominican general and political figure. He served as the president of the Provisional Government Junta of the Dominican Republic in 1899, and again between 1902 and 1903. ...

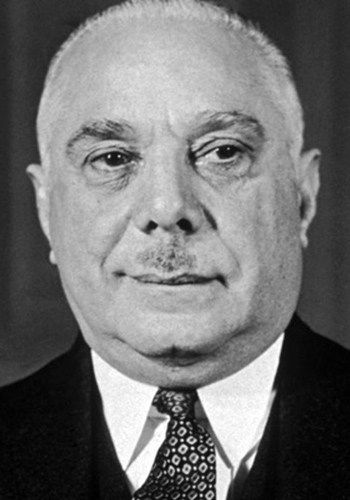

followed. From 1930 the dictatorship of

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina ( , ; 24 October 189130 May 1961), nicknamed ''El Jefe'' (, "The Chief" or "The Boss"), was a Dominican dictator who ruled the Dominican Republic from February 1930 until his assassination in May 1961. He ser ...

ruled until his assassination in 1961.

was elected president in 1962 but was deposed in a military coup in 1963. A

civil war in 1965, the country's last, was ended by U.S. military intervention and was followed by the authoritarian rule of

Joaquín Balaguer

Joaquín Antonio Balaguer Ricardo (1 September 1906 – 14 July 2002) was a Dominican politician, scholar, writer, and lawyer. He was President of the Dominican Republic serving three non-consecutive terms for that office from 1960 to 1962 ...

(1966–1978 and 1986–1996). Since 1978, the Dominican Republic has moved toward

representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a type of democracy where elected people represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function as some type of represen ...

, and has been led by

Leonel Fernández

Leonel Antonio Fernández Reyna () (born 26 December 1953) is a Dominican Republic, Dominican lawyer, academic, and was the 50th and 52nd President of the Dominican Republic from 1996 to 2000 and from 2004 to 2012. From 2016 until 2020, he was ...

for most of the time after 1996.

Danilo Medina

Danilo Medina Sánchez ( : born 10 November 1951) is a Dominican politician who was President of the Dominican Republic from 2012 to 2020.

Medina previously served as Chief of Staff to the President of the Dominican Republic from 1996 to 1999 ...

succeeded Fernández in 2012, winning 51% of the electoral vote over his opponent ex-president

Hipólito Mejía

Rafael Hipólito Mejía Domínguez (born 22 February 1941) is a Dominican politician who served as President of the Dominican Republic from 2000 to 2004.

During his presidential term in office the country was affected by one of its worst econ ...

. He was later succeeded by

Luis Abinader

Luis Rodolfo Abinader Corona (; born 12 July 1967) is a Dominican economist, businessman, and politician who is serving as the 54th president of the Dominican Republic since 2020. He served as the Modern Revolutionary Party candidate for Presi ...

in the 2020 presidential election after

anti-government protests erupted that year.

The Dominican Republic has the

largest economy (according to the

U.S. State Department and the

World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Interna ...

) in the Caribbean and Central American region and is the

seventh-largest economy in

Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

.

Over the last 25 years, the Dominican Republic has had the fastest-growing economy in the

Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the antimeridian. The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Politically, the term We ...

– with an average

real GDP growth rate of 5.3% between 1992 and 2018.

GDP growth in 2014 and 2015 reached 7.3 and 7.0%, respectively, the highest in the Western Hemisphere.

In the first half of 2016, the Dominican economy grew 7.4% continuing its trend of rapid

economic growth

Economic growth can be defined as the increase or improvement in the inflation-adjusted market value of the goods and services produced by an economy in a financial year. Statisticians conventionally measure such growth as the percent rate of ...

.

Recent growth has been driven by construction, manufacturing, tourism, and mining. The country is the site of the third largest

gold mine Gold Mine may refer to:

*Gold Mine (board game)

*Gold Mine (Long Beach), an arena

*"Gold Mine", a song by Joyner Lucas from the 2020 album '' ADHD''

See also

* ''Gold'' (1974 film), based on the novel ''Gold Mine'' by Wilbur Smith

*Gold mining

...

in the world, the

Pueblo Viejo mine

The Pueblo Viejo mine is a gold mine located in the north-central region of the Dominican Republic in the Sánchez Ramírez Province. It is the largest gold mine in Latin America and fifth largest in the world. It is also the first exploited mine ...

.

Private consumption has been strong, as a result of low inflation (under 1% on average in 2015), job creation, and a high level of

remittance

A remittance is a non-commercial transfer of money by a foreign worker, a member of a diaspora community, or a citizen with familial ties abroad, for household income in their home country or homeland. Money sent home by migrants competes wit ...

s.

Income inequality

There are wide varieties of economic inequality, most notably income inequality measured using the distribution of income (the amount of money people are paid) and wealth inequality measured using the distribution of wealth (the amount of we ...

, for generations an unsolved issue, has faded thanks to its rapid economic growth and now the Dominican Republic exhibits a

Gini coefficient of 39, similar to that of

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and

Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

, and better than countries like the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

,

Costa Rica

Costa Rica (, ; ; literally "Rich Coast"), officially the Republic of Costa Rica ( es, República de Costa Rica), is a country in the Central American region of North America, bordered by Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the no ...

or

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

.

Illegal

Illegal, or unlawful, typically describes something that is explicitly prohibited by law, or is otherwise forbidden by a state or other governing body.

Illegal may also refer to:

Law

* Violation of law

* Crime, the practice of breaking the ...

Immigration from Haiti has resulted in government action. Immigration from Haiti has increased tensions between Dominicans and Haitians. The Dominican Republic is also home to 114,050 illegal immigrants from

Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

.

According to the UN, the country struggles with systemic racism and discrimination based on race, mostly targeted towards people of Haitian origin.

The Dominican Republic is the

most visited destination in the Caribbean.

The year-round golf courses are major attractions.

[ A geographically diverse nation, the Dominican Republic is home to both the Caribbean's tallest mountain peak, ]Pico Duarte

Pico Duarte is the highest peak in the Dominican Republic, on the island of Hispaniola and in all the Caribbean. At above sea level, it gives the Dominican Republic the 16th-highest maximum elevation of any island in the world. Additionally, it ...

, and the Caribbean's largest lake and lowest point, Lake Enriquillo

Lake Enriquillo ( es, Lago Enriquillo) is a hypersaline lake in the Dominican Republic located in the southwestern region of the country. Its waters are shared between the provinces of Bahoruco and Independencia, the latter of which borders Hait ...

.World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

.[UNESCO around the World , República Dominicana](_blank)

Unesco.org (November 14, 1957). Retrieved on April 2, 2014. The Dominican Republic is highly vulnerable to natural disaster

A natural disaster is "the negative impact following an actual occurrence of natural hazard in the event that it significantly harms a community". A natural disaster can cause loss of life or damage property, and typically leaves some econ ...

s.

Etymology

The name Dominican originates from

The name Dominican originates from Santo Domingo de Guzmán

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

(Saint Dominic), the patron saint of astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, g ...

s, and founder of the Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of Cal ...

.Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

that is now known as the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo

The Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (UASD) (Autonomous University of Santo Domingo) is the public university system in the Dominican Republic with its flagship campus in the Ciudad Universitaria (lit. University City) neighborhood of San ...

, the first University in the New World. They dedicated themselves to the education of the inhabitants of the island, and to the protection of the native Taíno people

The Taíno were a historic indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the late 15th century, they were the pri ...

who were subjected to slavery.

For most of its history, up until independence, the colony was known simply as 'national anthem of the Dominican Republic

The national anthem of the Dominican Republic ( es, Himno nacional de República Dominicana), also known by its incipit Valiant Quisqueyans ( es, Quisqueyanos valientes), was composed by José Rufino Reyes y Siancas (1835–1905), and its lyri ...

(), the term "Dominicans" does not appear. The author of its lyrics, Emilio Prud'Homme

Emilio Prud'Homme y Maduro (August 20, 1856- July 21, 1932) was a Dominican lawyer, writer, and educator. Prud'Homme is known for having authored the lyrics of the Dominican national anthem. He is also attributed with helping establish a nationa ...

, consistently uses the poetic term "Quisqueyans" (). The word "Quisqueya" derives from the Taíno language

Taíno is an extinct Arawakan language that was spoken by the Taíno people of the Caribbean. At the time of Spanish contact, it was the most common language throughout the Caribbean. Classic Taíno (Taíno proper) was the native language of th ...

, and means "mother of the lands" (). It is often used in songs as another name for the country. The name of the country in English is often shortened to "the D.R." (), but this is rare in Spanish.

History

Pre-European history

The Arawakan-speaking

The Arawakan-speaking Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

moved into Hispaniola from the north east region of what is now known as South America, displacing earlier inhabitants,[ c. 650 C.E. They engaged in farming, fishing,][ The fierce ]Caribs

“Carib” may refer to:

People and languages

*Kalina people, or Caribs, an indigenous people of South America

**Carib language, also known as Kalina, the language of the South American Caribs

*Kalinago people, or Island Caribs, an indigenous pe ...

drove the Taíno to the northeastern Caribbean, during much of the 15th century. The estimates of Hispaniola's population in 1492 vary widely, including tens of thousands, one hundred thousand,[ and four hundred thousand to two million. Determining precisely how many people lived on the island in pre-Columbian times is next to impossible, as no accurate records exist. By 1492, the island was divided into five Taíno chiefdoms. The Taíno name for the entire island was either ''Ayiti'' or ''Quisqueya''.]Anacaona

Anacaona (1474?–1504), or Golden Flower, was a Taíno cacica, or female ''cacique'' (chief), religious expert, poet and composer born in Xaragua. Before the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492, Ayiti or Quisqueya to the Taínos (the Spaniar ...

of Xaragua and her ex-husband Chief Caonabo

Caonabo (died 1496) was a Taíno ''cacique'' (chieftain) of Hispaniola at the time of Christopher Columbus's arrival to the island. He was known for his fighting skills and his ferocity. He was married to Anacaona, who was the sister of another ' ...

of Maguana, as well as Chiefs Guacanagaríx

Guacanagarix (alternate transcriptions: Guacanacaríc, Guacanagarí) was one of five Taíno caciques of the Caribbean island henceforth known as Hispaniola at the arrival of the Europeans in 1492. This was contemporaneous with the first of the voya ...

, Guamá

Guamá (died c. 1532) was a Taíno rebel chief who led a rebellion against Spanish rule in Cuba in the 1530s. Legend states that Guamá was first warned about the Spanish conquistador by Hatuey, a Taíno cacique from the island of Hispaniola. ...

, Hatuey

Hatuey (), also Hatüey (; died 2 February 1512) was a Taíno ''Cacique'' (chief) of the Hispaniola province of Guahaba (present-day La Gonave, Haiti). He lived from the late 15th until the early 16th century. One day Chief Hatuey and many of ...

, and Enriquillo

Enriquillo, also known as "Enrique" by the Spaniards, was a Taíno cacique who rebelled against the Spaniards between 1519 and 1533. Enriquillo's rebellion is the best known rebellion of the early Caribbean period. He was born on the shores of ...

. The latter's successes gained his people an autonomous enclave for a time on the island. Within a few years after 1492, the population of Taínos had declined drastically, due to smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, measles, and other diseases that arrived with the Europeans.["History of Smallpox – Smallpox Through the Ages"](_blank)

. ''Texas Department of State Health Services.''

The first recorded smallpox outbreak, in the Americas, occurred on Hispaniola in 1507.[ Remnants of the Taíno culture include their cave paintings, such as the ]Pomier Caves

The Pomier Caves are a series of 55 caves located north of San Cristobal in the south of the Dominican Republic. They contain the largest collection of rock art in the Caribbean created since 2,000 years ago primarily by the Taíno people but ...

, as well as pottery designs, which are still used in the small artisan village of Higüerito, Moca.

European colonization

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

arrived on the island on December 5, 1492, during the first of his four voyages to the Americas. He claimed the land for Spain and named it ''La Española'', due to its diverse climate and terrain, which reminded him of the Spanish landscape. In 1496, Bartholomew Columbus

Bartholomew Columbus ( lij, label= Genoese, Bertomê Corombo; pt, Bartolomeu Colombo; es, Bartolomé Colón; it, Bartolomeo Colombo; – 1515) was an Italian explorer from Genoa and the younger brother of Christopher Columbus.

Biography

Bor ...

, Christopher's brother, built the city of Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

, Western Europe's first permanent settlement in the "New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

". The Spaniards created a plantation economy

A plantation economy is an economy based on agricultural mass production, usually of a few commodity crops, grown on large farms worked by laborers or slaves. The properties are called plantations. Plantation economies rely on the export of cas ...

on the island.infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

s. Other causes were abuse, suicide, the breakup of family, starvation,[ the ]encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

system, which resembled a feudal system

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

in Medieval Europe, war with the Spaniards, changes in lifestyle, and mixing with other peoples. Laws passed for the native peoples' protection (beginning with the Laws of Burgos, 1512–1513) were never truly enforced. African slaves were imported to replace the dwindling Taínos.

On December 25, 1521, enslaved Africans of

On December 25, 1521, enslaved Africans of Senegalese

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

Wolof

Wolof or Wollof may refer to:

* Wolof people, an ethnic group found in Senegal, Gambia, and Mauritania

* Wolof language, a language spoken in Senegal, Gambia, and Mauritania

* The Wolof or Jolof Empire, a medieval West African successor of the Mal ...

origin led the first major slave revolt

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by enslaved people, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of enslaved people have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire for freed ...

of the Americas on the plantation of Diego Colón

Diego Columbus ( pt, Diogo Colombo; es, Diego Colón; it, Diego Colombo; 1479/1480 – February 23, 1526) was a navigator and explorer under the Kings of Castile and Aragón. He served as the 2nd Admiral of the Indies, 2nd Viceroy of the Indie ...

, son of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

. They fought the Spanish colonists for a year, until the rebellion was brutally crushed in December 1522. After this, laws were passed in order to enforce harsh punishments on those who planned to stage another uprising. But despite this, slave revolts continued to transpire as many of the slaves successfully escaped. This also resulted in the establishment of the first Maroon

Maroon ( US/ UK , Australia ) is a brownish crimson color that takes its name from the French word ''marron'', or chestnut. "Marron" is also one of the French translations for "brown".

According to multiple dictionaries, there are var ...

communities of the Americas, and many Maroon leaders emerged from these revolts. Leaders such as Sebastian Lemba, a Maroon born in Africa who successfully rebelled in 1532, became the most prolific leader of this era. His actions would inspire other leaders such as Juan Vaquero, Diego del Guzmán, Fernando Montoro, Juan Criollo and Diego del Campo, to lead successful revolts of their own. Maroons would continue to place Spanish control in jeopardy, as many parts of the island fell under Maroon control. Although many of the leaders would eventually be captured and executed by the Admiral, Maroon activities would continue to be present in the island well into the 17th century.

After its conquest of the Aztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those g ...

s and Incas

The Inca Empire (also Quechuan and Aymaran spelling shift, known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechuan languages, Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) wa ...

, Spain neglected its Caribbean holdings. Hispaniola's sugar plantation economy quickly declined. Most Spanish colonists left for the silver-mines of Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

and Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

, while new immigrants from Spain bypassed the island. Agriculture dwindled, new imports of slaves ceased, and white colonists, free blacks, and slaves alike lived in poverty, weakening the racial hierarchy and aiding ''intermixing'', resulting in a population of predominantly mixed Spaniard, Taíno, and African descent. Except for the city of Santo Domingo, which managed to maintain some legal exports, Dominican ports were forced to rely on contraband trade, which, along with livestock, became one of the main sources of livelihood for the island's inhabitants.

In the mid-17th century, France sent colonists to settle the island of Tortuga and the northwestern coast of Hispaniola (which the Spaniards had abandoned by 1606) due to its strategic position in the region. In order to entice the pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

s, France supplied them with women who had been taken from prisons, accused of prostitution and thieving. After decades of armed struggles with the French settlers, Spain ceded the western coast of the island to France with the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick

The Peace of Ryswick, or Rijswijk, was a series of treaties signed in the Dutch city of Rijswijk between 20 September and 30 October 1697. They ended the 1688 to 1697 Nine Years' War between France and the Grand Alliance, which included England, ...

, whilst the Central Plateau remained under Spanish domain. France created a wealthy colony on the island, while the Spanish colony continued to suffer economic decline.English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

forces landed on Hispaniola, and marched 30 miles overland to Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

, the main Spanish stronghold on the island, where they laid siege to it. Spanish lancer

A lancer was a type of cavalryman who fought with a lance. Lances were used for mounted warfare in Assyria as early as and subsequently by Persia, India, Egypt, China, Greece, and Rome. The weapon was widely used throughout Eurasia during the M ...

s attacked the English forces, sending them careening back toward the beach in confusion. The English commander hid behind a tree where, in the words of one of his soldiers, he was "so much possessed with terror that he could hardly speak". The Spanish defenders who had secured victory were rewarded with titles from the Spanish Crown

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

.

18th century

The

The House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanis ...

replaced the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

in Spain in 1700, and introduced economic reforms that gradually began to revive trade in Santo Domingo. The crown progressively relaxed the rigid controls and restrictions on commerce between Spain and the colonies and among the colonies. The last ''flotas'' sailed in 1737; the monopoly port system was abolished shortly thereafter. By the middle of the century, the population was bolstered by emigration from the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

, resettling the northern part of the colony and planting tobacco in the Cibao Valley

The Cibao, usually referred as "El Cibao", is a region of the Dominican Republic located at the northern part of the country. As of 2009 the Cibao has a population of 5,622,378 making it the most populous region in the country.

The region constitu ...

, and importation of slaves was renewed.

Santo Domingo's exports soared and the island's agricultural productivity rose, which was assisted by the involvement of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, allowing privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s operating out of Santo Domingo to once again patrol surrounding waters for enemy merchantmen

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are us ...

.War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

just two decades prior, and they sharply reduced the amount of enemy trade operating in West Indian

A West Indian is a native or inhabitant of the West Indies (the Antilles and the Lucayan Archipelago). For more than 100 years the words ''West Indian'' specifically described natives of the West Indies, but by 1661 Europeans had begun to use it ...

waters.[ The ]prizes

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements. they took were carried back to Santo Domingo, where their cargoes were sold to the colony's inhabitants or to foreign merchants doing business there. The enslaved population of the colony also rose dramatically, as numerous captive Africans were taken from enemy slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

s in West Indian waters.[

Between 1720 and 1774, Dominican privateers cruised the waters from Santo Domingo to the coast of Tierra Firme, taking British, French, and Dutch ships with cargoes of African slaves and other commodities.

] The colony of Santo Domingo saw a population increase during the 18th century, as it rose to about 91,272 in 1750. Of this number, approximately 38,272 were white landowners, 38,000 were free mixed people of color, and some 15,000 were slaves. This contrasted sharply with the population of the French colony of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) – the wealthiest colony in the Caribbean and whose population of one-half a million was 90% enslaved and overall, seven times as numerous as the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo.

The colony of Santo Domingo saw a population increase during the 18th century, as it rose to about 91,272 in 1750. Of this number, approximately 38,272 were white landowners, 38,000 were free mixed people of color, and some 15,000 were slaves. This contrasted sharply with the population of the French colony of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) – the wealthiest colony in the Caribbean and whose population of one-half a million was 90% enslaved and overall, seven times as numerous as the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo.Guanche Guanche may refer to:

*Guanches, the indigenous people of the Canary Islands

*Guanche language

Guanche is an extinct language that was spoken by the Guanches of the Canary Islands until the 16th or 17th century. It died out after the conquest ...

s, proclaimed: 'It does not matter if the French are richer than us, we are still the true inheritors of this island. In our veins runs the blood of the heroic ''conquistadores'' who won this island of ours with sword and blood.' As restrictions on colonial trade were relaxed, the colonial elites of Saint-Domingue offered the principal market for Santo Domingo's exports of beef, hides, mahogany, and tobacco. With the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt ...

in 1791, the rich urban families linked to the colonial bureaucracy fled the island, while most of the rural ''hateros'' (cattle ranchers) remained, even though they lost their principal market.

Inspired by disputes between whites and mulattoes in Saint-Domingue, a slave revolt broke out in the French colony. Although the population of Santo Domingo was perhaps one-fourth that of Saint-Domingue, this did not prevent the King of Spain from launching an invasion of the French side of the island in 1793, attempting to seize all, or part, of the western third of the island in an alliance of convenience with the rebellious slaves.column

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column is a compression member. ...

of Dominican troops advanced into Saint-Domingue and were joined by Haitian rebels. However, these rebels soon turned against Spain and instead joined France. The Dominicans were not defeated militarily, but their advance was restrained, and when in 1795 Spain ceded Santo Domingo to France by the Treaty of Basel, Dominican attacks on Saint-Domingue ceased.

French occupation

Between 1795-1802, the French colonists would endure and suppress several slave revolts in Santo Domingo such as the back to back revolts of Hincha and Samaná in the spring of 1795, the large-scale Nigua rebellion in 1796, and the Gambia revolt of 1802. After declaring independence in 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Haitian Creole: ''Jan-Jak Desalin''; ; 20 September 1758 – 17 October 1806) was a leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first ruler of an independent First Empire of Haiti, Haiti under the Constitution of Haiti, 1 ...

, attempted to take control of the eastern side of the island in 1805, laying siege to the city until being forced to retreat in light of news of a possible invasion by a French naval squadron believed to be heading towards Haiti, and along his retreat, subjecting the Dominicans to a massacre

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

. The French retained Santo Domingo until 1809, when combined Spanish and Dominican forces, aided by the British, defeated the French, leading to a recolonization by Spain.

Ephemeral independence

After a dozen years of discontent and failed independence plots by various opposing groups, including a failed 1812 revolt led by Dominican conspirators José Leocadio, Pedro de Seda, and Pedro Henríquez, Santo Domingo's former Lieutenant-Governor (top administrator), José Núñez de Cáceres

José Núñez de Cáceres y Albor (March 14, 1772 – September 11, 1846) was a Dominican politician and writer. He is known for being the leader of the independence movement against Spain in 1821 and the only president of the short-lived Repu ...

, declared the colony's independence from the Spanish crown

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

as Spanish Haiti

The Independent Republic of Spanish Haiti ( es, República del Haití Español), also called the Independent State of Spanish Haiti () was the independent state that resulted from the defeat of Spanish colonialists from Santo Domingo on November ...

, on November 30, 1821. This period is also known as the Ephemeral independence.

Haitian occupation of Santo Domingo (1822–44)

The newly independent republic ended two months later under the Haitian government led by

The newly independent republic ended two months later under the Haitian government led by Jean-Pierre Boyer

Jean-Pierre Boyer (15 February 1776 – 9 July 1850) was one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, and President of Haiti from 1818 to 1843. He reunited the north and south of the country into the Republic of Haiti in 1820 and also annex ...

.Joseph Balthazar Inginac

Joseph Balthazar Inginac (also known as Balthazar Inginac) (1775 in Leogane - 1847) in Leogane - was a Haitian diplomat and member of the presidential inner circle. He served as the secretary-general for the two longest-serving presidents, A ...

's ''Code Rural''. In the rural and rugged mountainous areas, the Haitian administration was usually too inefficient to enforce its own laws. It was in the city of Santo Domingo that the effects of the occupation were most acutely felt, and it was there that the movement for independence originated.

The Haitians associated the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

with the French slave-masters who had exploited them before independence and confiscated all church property, deported all foreign clergy, and severed the ties of the remaining clergy to the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

. All levels of education collapsed; the university was shut down, as it was starved both of resources and students, with young Dominican men from 16 to 25 years old being drafted into the Haitian army. Boyer's occupation troops, who were largely Dominicans, were unpaid and had to "forage and sack" from Dominican civilians. Haiti imposed a "heavy tribute" on the Dominican people.España Boba

In the history of the Dominican Republic, the period of ''España Boba'' (Spanish: "Meek Spain") lasted from 1809 to 1821, during which the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo was under Spanish rule, but the Spanish government exercised minimal ...

period. The few landowners that wanted slavery established in Santo Domingo had to emigrate to Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

, or Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia (, "Great Colombia"), or Greater Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia (Spanish: ''República de Colombia''), was a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 18 ...

. Many landowning families stayed on the island, with a heavy concentration of landowners settling in the Cibao region. After independence, and eventually being under Spanish rule once again in 1861, many families returned to Santo Domingo including new waves of immigration from Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

.

Dominican War of Independence (1844–56)

In 1838,

In 1838, Juan Pablo Duarte

Juan Pablo Duarte y Díez (January 26, 1813 – July 15, 1876) was a Dominican military leader, writer, activist, and nationalist politician who was the foremost of the founding fathers of the Dominican Republic and bears the title of Father of ...

founded a secret society called La Trinitaria, which sought the complete independence of Santo Domingo without any foreign intervention.Francisco del Rosario Sánchez

Francisco del Rosario Sánchez (March 9, 1817 – July 4, 1861) was a Dominican revolutionary, politician, and former president of the Dominican Republic. He is considered by Dominicans as the second leader of the 1844 Dominican War of Independen ...

and Ramon Matias Mella, despite not being among the founding members of La Trinitaria, were decisive in the fight for independence. Duarte, Mella, and Sánchez are considered the three Founding Fathers of the Dominican Republic.

In 1843, the new Haitian president, Charles Rivière-Hérard

Charles Rivière-Hérard also known as Charles Hérard aîné (16 February 1789 – 31 August 1850) was an officer in the Haitian Army under Alexandre Pétion during his struggles against Henri Christophe. He was declared President of Haiti on ...

, exiled or imprisoned the leading ''Trinitarios'' (Trinitarians).[ After subduing the Dominicans, Rivière-Hérard, a mulatto, faced a rebellion by blacks in ]Port-au-Prince

Port-au-Prince ( , ; ht, Pòtoprens ) is the capital and most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 987,311 in 2015 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618,894. The metropolitan area is define ...

. Haiti had formed two regiments composed of Dominicans from the city of Santo Domingo; these were used by Rivière-Hérard to suppress the uprising.[

] On February 27, 1844, the surviving members of ''La Trinitaria'', now led by

On February 27, 1844, the surviving members of ''La Trinitaria'', now led by Tomás Bobadilla

Tomás Bobadilla y Briones (30 March 1785 – 21 December 1871) was a writer, intellectual and politician from the Dominican Republic. The first ruler of the Dominican Republic, he had a significant participation in the movement for Dom ...

, declared the independence from Haiti. The ''Trinitarios'' were backed by Pedro Santana

Pedro Santana y Familias, 1st Marquess of Las Carreras (June 29, 1801June 14, 1864) was a Dominican military commander and royalist politician who served as the president of the junta that had established the First Dominican Republic, a pre ...

, a wealthy cattle rancher from El Seibo

El Seibo (), alternatively spelt El Seybo, is a province of the Dominican Republic. Before 1992 it included what is now Hato Mayor province.

Municipalities and municipal districts

The province as of June 20, 2006 is divided into the following m ...

, who became general of the army of the nascent republic. The Dominican Republic's first Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

was adopted on November 6, 1844, and was modeled after the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

.Buenaventura Báez

Ramón Buenaventura Báez Méndez (July 14, 1812March 14, 1884), was a Dominican politician and military figure. He was president of the Dominican Republic for five nonconsecutive terms. His rule was characterized by being very corrupt and govern ...

held power most of the time, both ruling arbitrarily. They promoted competing plans to annex the new nation to another power: Santana favored Spain, and Báez the United States.

Threatening the nation's independence were renewed Haitian invasions. In March 1844, Rivière-Hérard attempted to reimpose his authority, but the Dominicans put up stiff opposition and inflicted heavy casualties on the Haitians.

The

The Battle of Azua

The Battle of Azua was the first major battle of the Dominican War of Independence and was fought on the 19 March 1844, at Azua de Compostela, Azua Province. A force of some 2,200 Dominican troops, a portion of the Army of the South, led by Gene ...

was the first major battle of the Dominican War of Independence

The Dominican War of Independence made the Dominican Republic a sovereign state on February 27, 1844. Before the war, the island of Hispaniola had been united for 22 years when the newly independent nation, previously known as the Captaincy Gen ...

and was fought on March 19. The Dominicans opened the battle with a cannon barrage followed by rifle discharges and machete charges. When the Haitian commander, Vicent Jean Degales, was beheaded by the Dominicans, his troops retreated in disarray. The outnumbered Dominican forces suffered only five casualties in the battle while the Haitians sustained over 1,000 killed. The Battle of Santiago was the second major battle of the war and was fought on March 30. The Haitians charged the Dominicans under grapeshot

Grapeshot is a type of artillery round invented by a British Officer during the Napoleonic Wars. It was used mainly as an anti infantry round, but had other uses in naval combat.

In artillery, a grapeshot is a type of ammunition that consists of ...

and musketry fire and were repulsed. At sea, the Dominicans defeated the Haitians at the Battle of Tortuguero

The Battle of Tortuguero was the first naval battle of the Dominican War of Independence and was fought on 15 April 1844 at Tortuguero, Azua Province. A force of three Dominican schooners led by Commander Juan Bautista Cambiaso defeated a force o ...

off the coast of Azua on April 15, temporarily expelling Haitian forces.

In early July 1844, Duarte was urged by his followers to take the title of President of the Republic. Duarte agreed, but only if free elections were arranged. However, Santana's forces took Santo Domingo on July 12, and they declared Santana ruler of the Dominican Republic. Santana then put Mella, Duarte, and Sánchez in jail. On February 27, 1845, Santana executed María Trinidad Sánchez

María Trinidad Sánchez, Mother Founder (16 May 1794, Santo Domingo- 27 February 1846, Santo Domingo) was a Dominican freedom fighter and a heroine of the Dominican War of Independence. She participated on the rebel side as a courier. Together wit ...

, heroine of La Trinitaria, and others for conspiracy.

On June 17, 1845, small Dominican detachments invaded Haiti, capturing Lascahobas

Lascahobas ( ht, Laskawobas; es, Las Caobas) is a commune located in the Centre department of Haiti, roughly one hour east of Mirebalais, 10 minutes south of Lac de Peligre, and one hour west of the border with the Dominican Republic.

The pop ...

and Hinche

Hinche (; ht, Ench; es, Hincha) is a commune in the Centre department Haiti. It has a population of about 50,000. It is the capital of the Centre department. Hinche is the hometown of Charlemagne Péralte, the Haitian nationalist leader who r ...

. The Dominicans established an outpost at Cachimán, but the arrival of Haitian reinforcements soon compelled them to retreat back across the frontier. Haiti launched a new invasion on August 6. A member of La Trinitaria, José María Serra, claimed that over 3,000 Haitian soldiers and less than 20 Dominican militias had been killed at this point.vanguard

The vanguard (also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

History

The vanguard derives fr ...

near the frontier at the Battle of Estrelleta

The Battle of Estrelleta was a major battle of the Dominican War of Independence and was fought on September 17, 1845, at the site of Estrelleta, near Las Matas de Farfán, San Juan Province (Dominican Republic), San Juan Province. A force of Domi ...

, where the Dominican infantry square

An infantry square, also known as a hollow square, was a historic combat formation in which an infantry unit formed in close order, usually when it was threatened with cavalry attack. As a traditional infantry unit generally formed a line to adva ...

repulsed a Haitian cavalry charge with bayonets. The Dominicans suffered no deaths during the battle and only three wounded. On November 27, the Dominicans defeated the Haitian army at the Battle of Beler

The Battle of Beler was one of the major battles of the Dominican War of Independence and was fought on the 27 November 1845 at the Beler savanna, Monte Cristi Province. A force of Dominican troops, a portion of the Army of the North, led by Gener ...

. Haitian losses were 350 killed, while the Dominicans suffered 16 killed. Among the dead were three Haitian generals, including the army's commander, Seraphin. The Dominicans repelled the Haitian forces, on both land and sea, by December 1845.

The Haitians invaded again in 1849, forcing the president of the Dominican Republic, Manuel Jimenes

Manuel José Jimenes González (January 14, 1808December 22, 1854) was a military figure and politician in the Dominican Republic. He served as the second President of the Dominican Republic from September 8, 1848, until May 29, 1849. Prior to ...

, to call upon Santana, whom he had ousted as president, to lead the Dominicans against this new invasion. Santana met the enemy at Ocoa, April 21, with only 400 militiamen, and succeeded in defeating the 18,000-strong Haitian army. The battle began with heavy cannon fire by the entrenched Haitians and ended with a Dominican assault followed by hand-to-hand combat

Hand-to-hand combat (sometimes abbreviated as HTH or H2H) is a physical confrontation between two or more persons at short range (grappling distance or within the physical reach of a handheld weapon) that does not involve the use of weapons.Huns ...

. Three Haitian generals were killed. In November 1849, Dominican seamen raided the Haitian coasts, plundered seaside villages, as far as Dame Marie, and butchered crews of captured enemy ships.

By 1854, both countries were at war again. In November, a Dominican squadron composed of the brigantine

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts.

Older ...

''27 de Febrero'' and schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

''Constitución'' captured a Haitian warship and bombarded Anse-à-Pitres and Saltrou. In November 1855, Haiti invaded again. Over 1,000 Haitians (including two generals) were killed in the battles of Santomé and Cambronal in December 1855. The Haitians suffered 1,500 killed at Sabana Larga and Jácuba in January 1856, and in an engagement at Ouanaminthe

Ouanaminthe ( ht, Wanament or Wanamèt; es, Juana Méndez) is a commune or town located in the Nord-Est department of Haiti. It lies along the Massacre River, which forms part of the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Ouanaminth ...

, over 1,000 Haitian troops were killed and many were wounded and missing.

Battles of the Dominican War of Independence

''Key: (D) – Dominican Victory; (H) – Haitian Victory''

*1844

** March 18 – Battle of Cabeza de Las Marías (H)

** March 19 – Battle of Azua

The Battle of Azua was the first major battle of the Dominican War of Independence and was fought on the 19 March 1844, at Azua de Compostela, Azua Province. A force of some 2,200 Dominican troops, a portion of the Army of the South, led by Gene ...

(D)

** March 30 – Battle of Santiago (D)

** April 13 – Battle of El Memiso (D)

** April 15 – Battle of Tortuguero

The Battle of Tortuguero was the first naval battle of the Dominican War of Independence and was fought on 15 April 1844 at Tortuguero, Azua Province. A force of three Dominican schooners led by Commander Juan Bautista Cambiaso defeated a force o ...

(D)

** December 6 – Battle of Fort Cachimán (D)

*1845

** September 17 – Battle of Estrelleta

The Battle of Estrelleta was a major battle of the Dominican War of Independence and was fought on September 17, 1845, at the site of Estrelleta, near Las Matas de Farfán, San Juan Province (Dominican Republic), San Juan Province. A force of Domi ...

(D)

** November 27 – Battle of Beler

The Battle of Beler was one of the major battles of the Dominican War of Independence and was fought on the 27 November 1845 at the Beler savanna, Monte Cristi Province. A force of Dominican troops, a portion of the Army of the North, led by Gener ...

(D)

*1849

** April 19 – Battle of El Número

The Battle of El Número, was a major battle during the years after the Dominican War of Independence and was fought on the 17 April 1849, nearby Azua de Compostela, Azua Province. A force of 300 Dominican troops, a portion of the Army of the Sou ...

(D)

** April 21 – Battle of Las Carreras

The Battle of Las Carreras was a major battle during the years after the Dominican War of Independence and was fought on the 21–22 April 1849, nearby Baní, Peravia Province. A force of 800 Dominican troops, a portion of the Army of the South, ...

(D)

*1855

** December 22 – Battle of Santomé

The Battle of Santomé was a major battle during the years after the Dominican War of Independence and was fought on the 22 December 1855, in the province of San Juan Province (Dominican Republic), San Juan. A detachment of Dominican troops formin ...

(D)

** December 22 – Battle of Cambronal

The Battle of Cambronal was a major battle during the years after the Dominican War of Independence

The Dominican War of Independence made the Dominican Republic a sovereign state on February 27, 1844. Before the war, the island of Hispaniola ...

(D)

*1856

** January 24 – Battle of Sabana Larga (D)

First Republic

The Dominican Republic's first constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

was adopted on November 6, 1844. The state was commonly known as Santo Domingo in English until the early 20th century. It featured a presidential form of government with many liberal tendencies, but it was marred by Article 210, imposed by Pedro Santana

Pedro Santana y Familias, 1st Marquess of Las Carreras (June 29, 1801June 14, 1864) was a Dominican military commander and royalist politician who served as the president of the junta that had established the First Dominican Republic, a pre ...

on the constitutional assembly by force, giving him the privileges of a dictatorship until the war of independence was over. These privileges not only served him to win the war but also allowed him to persecute, execute and drive into exile his political opponents, among which Duarte was the most important.

The constant threat of renewed Haitian invasion required all men of fighting age to take up arms in defense against the Haitian military. Theoretically, fighting age was generally defined as between 15 and 18 years of age to 40 or 50 years. Despite wide, popular glorification of military service, many in the ranks of the Liberation Army were mutinous and desertion

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ar ...

rates were high despite penalties as severe as death for shirking the obligation of military service.

The population of the Dominican Republic in 1845 was approximately 230,000 people (100,000 whites; 40,000 blacks; and 90,000 mulattoes). Due to the rugged mountainous terrain of the island the regions of the Dominican Republic developed in isolation from one another. In the south, also known at the time as Ozama, the economy was dominated by cattle-ranching (particularly in the southeastern savannah) and cutting mahogany and other hardwoods for export. This region retained a semi-feudal character, with little commercial agriculture, the hacienda as the dominant social unit, and the majority of the population living at a subsistence level. In the north (better-known as Cibao), the nation's richest farmland, farmers supplemented their subsistence crops by growing tobacco for export, mainly to Germany. Tobacco required less land than cattle ranching and was mainly grown by smallholders, who relied on itinerant traders to transport their crops to Puerto Plata and Monte Cristi. Santana antagonized the Cibao farmers, enriching himself and his supporters at their expense by resorting to multiple peso printings that allowed him to buy their crops for a fraction of their value. In 1848, he was forced to resign and was succeeded by his vice-president, Manuel Jimenes

Manuel José Jimenes González (January 14, 1808December 22, 1854) was a military figure and politician in the Dominican Republic. He served as the second President of the Dominican Republic from September 8, 1848, until May 29, 1849. Prior to ...

.

After defeating a new Haitian invasion in 1849, Santana marched on Santo Domingo and deposed Jimenes in a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

. At his behest, Congress elected Buenaventura Báez

Ramón Buenaventura Báez Méndez (July 14, 1812March 14, 1884), was a Dominican politician and military figure. He was president of the Dominican Republic for five nonconsecutive terms. His rule was characterized by being very corrupt and govern ...

as president, but Báez was unwilling to serve as Santana's puppet, challenging his role as the country's acknowledged military leader. In 1853, Santana was elected president for his second term, forcing Báez into exile. Three years later, he negotiated a treaty leasing a portion of Samaná Peninsula

The Samaná Península is a peninsula in Dominican Republic situated in the province of Samaná. The Samaná Peninsula is connected to the rest of the state by the isthmus of Samaná; to its south is Samaná Bay. The peninsula contains many beache ...

to a U.S. company; popular opposition forced him to abdicate, enabling Báez to return and seize power. With the treasury depleted, Báez printed eighteen million uninsured pesos, purchasing the 1857 tobacco crop with this currency and exporting it for hard cash at immense profit to himself and his followers. Cibao tobacco planters, who were ruined when hyperinflation ensued, revolted and formed a new government headed by José Desiderio Valverde

José Desiderio Valverde Pérez (1822December 22, 1903) was a Dominican military figure and politician. He served as president of the Dominican Republic

The president of the Dominican Republic ( es, Presidente de la República Dominicana ...

and headquartered in Santiago de los Caballeros. In July 1857, General Juan Luis Franco Bidó besieged Santo Domingo. The Cibao-based government declared an amnesty to exiles and Santana returned and managed to replace Franco Bidó in September 1857. After a year of civil war, Santana captured Santo Domingo in June 1858, overthrew both Báez and Valverde and installed himself as president.

Restoration republic

In 1861, after imprisoning, silencing, exiling, and executing many of his opponents and due to political and economic reasons, Santana asked Queen Isabella II of Spain

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successio ...

to retake control of the Dominican Republic, after a period of only 17 years of independence. Spain, which had not come to terms with the loss of its American colonies 40 years earlier, accepted his proposal and made the country a colony again. Haiti, fearful of the reestablishment of Spain as colonial power, gave refuge and logistics to revolutionaries seeking to reestablish the independent nation of the Dominican Republic. The ensuing civil war, known as the ''War of Restoration'', claimed more than 50,000 lives.

The War of Restoration began in Santiago on August 16, 1863. Spain had a difficult time fighting the Dominican guerrillas

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactics ...

. Over the course of the war, the Spanish would spend over 33 million pesos and suffer 30,000 casualties, including 10,888 killed or wounded in action. In the south, Dominican forces under José María Cabral

General José María Cabral y Luna (born Ingenio Nuevo; December 12, 1816 in San Cristóbal Province – February 28, 1899 in Santo Domingo) was a Dominican military figure and politician. He served as the first Supreme Chief of the Dominica ...

defeated the Spanish in the Battle of La Canela on December 4, 1864. The victory showed the Dominicans that they could defeat the Spaniards in pitched battle

A pitched battle or set-piece battle is a battle in which opposing forces each anticipate the setting of the battle, and each chooses to commit to it. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter. A ...

. After two years of fighting, Spain abandoned the island in 1865. Political strife again prevailed in the following years; warlords ruled, military revolts were extremely common, and the nation amassed debt.

After the Ten Years' War

The Ten Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Diez Años; 1868–1878), also known as the Great War () and the War of '68, was part of Cuba's fight for independence from Spain. The uprising was led by Cuban-born planters and other wealthy natives. O ...

(1868–78) broke out in Spanish Cuba, Dominican exiles, including Máximo Gómez

Máximo Gómez y Báez (November 18, 1836 – June 17, 1905) was a Dominican Generalissimo in Cuban War of Independence, Cuba's War of Independence (1895–1898). He was known for his controversial Scorched earth, scorched-earth policy, whic ...

, Luis Marcano

{{Infobox military person

, name = Luis Marcano Álvarez

, image = Luis Marcano Álvarez.jpg

, caption =

, birth_date = {{Birth date, 1831, 11, 29

, death_date = {{Death date and age, 1870, 05, 16, 18 ...

and Modesto Díaz

Modesto Díaz (1826–1892) was a Dominican Major General of the Cuban Liberation Army. He was a member of the Spanish Army in his country of origin during the Dominican Restoration War (1863–1865). He settled in Cuba and was reinstated to act ...

, joined the Cuban Revolutionary Army

The Cuban Revolutionary Army ( es, Ejército Revolucionario) serve as the ground forces of Cuba. Formed in 1868 during the Ten Years' War, it was originally known as the Cuban Constitutional Army. Following the Cuban Revolution, the revolutiona ...

and provided its initial training and leadership.

In 1869, U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

ordered U.S. Marines to the island for the first time.[ Following the virtual takeover of the island, Báez offered to sell the country to the United States.][ Grant desired a naval base at Samaná and also a place for resettling newly freed ]African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

. The treaty, which included U.S. payment of $1.5 million for Dominican debt repayment, was defeated in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

in 1870Ulises Heureaux

Ulises Hilarión Heureaux Leibert (; October 21, 1845 – July 26, 1899) nicknamed Lilís, was president of the Dominican Republic from September 1, 1882 to September 1, 1884, from January 6, 1887 to February 27, 1889 and again from April 30, 18 ...

.[ In 1899, he was assassinated. However, the relative calm over which he presided allowed improvement in the Dominican economy. The sugar industry was modernized,][ At first, the ]Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

immigrants often faced discrimination in the Dominican Republic, but they were eventually assimilated into Dominican society, giving up their own culture and language.[ During the U.S. occupation of 1916–24, peasants from the countryside, called Gavilleros, would not only kill U.S. Marines, but would also attack and kill Arab vendors traveling through the countryside.

]

20th century (1900–30)

From 1902 on, short-lived governments were again the norm, with their power usurped by

From 1902 on, short-lived governments were again the norm, with their power usurped by caudillo

A ''caudillo'' ( , ; osp, cabdillo, from Latin , diminutive of ''caput'' "head") is a type of personalist leader wielding military and political power. There is no precise definition of ''caudillo'', which is often used interchangeably with " ...

s in parts of the country. Furthermore, the national government was bankrupt and, unable to pay its debts to European creditors, faced the threat of military intervention by France, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

.Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...