Sir Malcolm Sargent on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

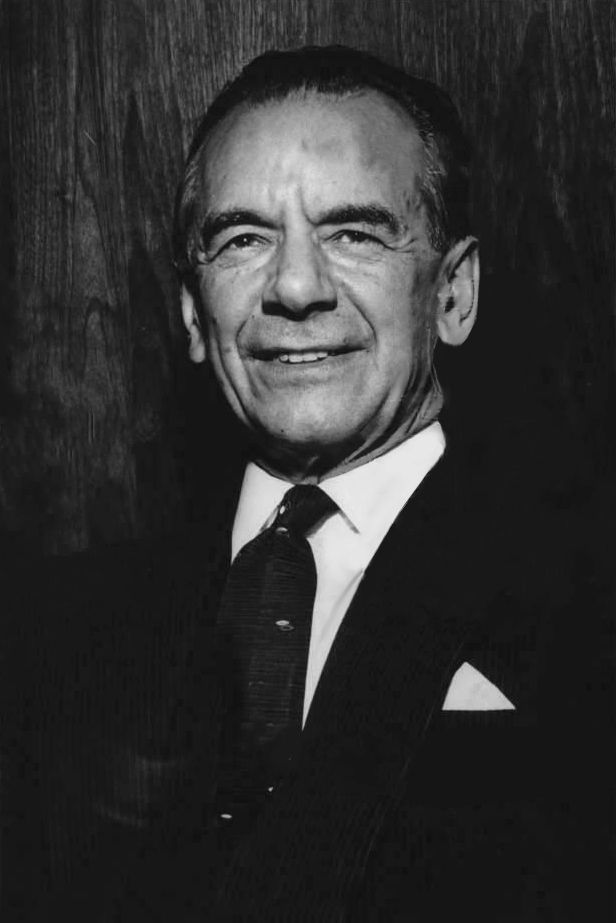

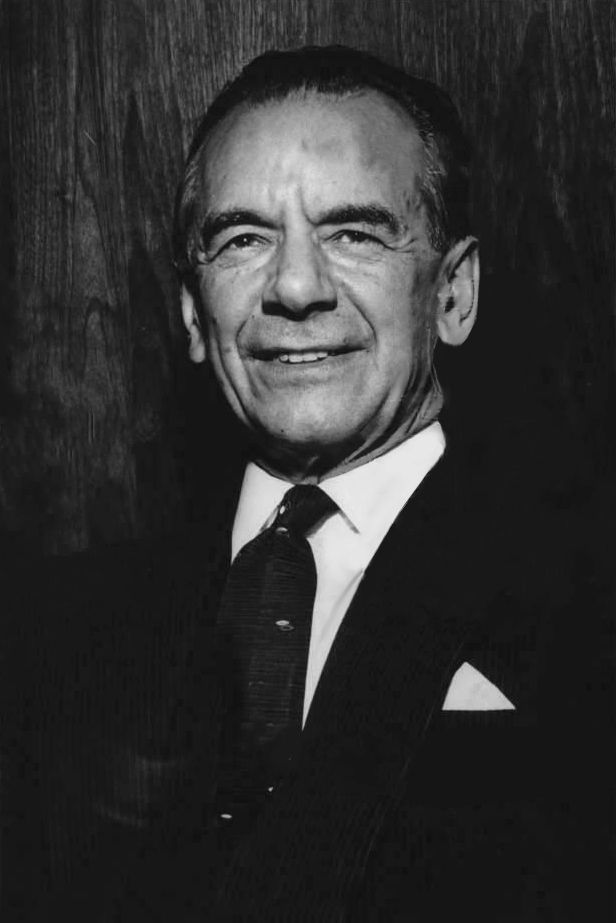

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent (29 April 1895 – 3 October 1967) was an English conductor, organist and composer widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works. The musical ensembles with which he was associated included the

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent (29 April 1895 – 3 October 1967) was an English conductor, organist and composer widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works. The musical ensembles with which he was associated included the

"Sargent, Sir (Harold) Malcolm Watts (1895–1967), conductor"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2021 At the age of 16 he gained his diploma as Associate of the

"Sargent, Sir (Harold) Malcolm"

''Grove Music Online'', Oxford University Press, 2001. Retrieved 14 March 2021

Sargent worked first as an organist at

Sargent worked first as an organist at

In 1926 Sargent began an association with the

In 1926 Sargent began an association with the  Elizabeth Courtauld, wife of the industrialist and art collector Samuel Courtauld, promoted a popular series of subscription concerts beginning in 1929 and on Schnabel's advice engaged Sargent as chief conductor, with guest conductors including

Elizabeth Courtauld, wife of the industrialist and art collector Samuel Courtauld, promoted a popular series of subscription concerts beginning in 1929 and on Schnabel's advice engaged Sargent as chief conductor, with guest conductors including

In October 1932 Sargent suffered a near-fatal attack of

In October 1932 Sargent suffered a near-fatal attack of  Being popular in Australia with players as well as the public, Sargent made three lengthy tours of Australia and New Zealand, beginning in 1936. He was on the point of accepting a permanent appointment with the

Being popular in Australia with players as well as the public, Sargent made three lengthy tours of Australia and New Zealand, beginning in 1936. He was on the point of accepting a permanent appointment with the

Sargent made two tours of South America. In 1950 he conducted in

Sargent made two tours of South America. In 1950 he conducted in

/ref> For this reason, among others, Sargent was continually in demand as a conductor for concertos. ''The Times'' obituary said Sargent "was of all British conductors in his day the most widely esteemed by the lay public... a fluent, attractive pianist, a brilliant score-reader, a skilful and effective arranger and orchestrator... as a conductor his stick technique was regarded by many as the most accomplished and reliable in the world.... s taste... was moulded by the Victorian cathedral tradition into which he was born." It commented that, in his later years, his interpretations of the standard classical and romantic repertoire were "prepared... down to the last detail" but sometimes "unexuberant", though his performances of "the music composed within his lifetime... remained lucid and continually compelling". The flute player Gerald Jackson wrote, "I feel that altonconducts his own music as well as anyone else, with the possible exception of Sargent, who of course introduced and always makes a big thing of ''Belshazzar's Feast''." The composers whose works Sargent regularly conducted included, from the eighteenth century, Bach, Handel,

''Who Was Who'', Oxford University Press, 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2014 His public service appointments included the joint presidency of the London Union of Youth Clubs, and the presidency of the

Since 1968, the year after Sargent's death, the Proms have begun on a Friday evening rather than as previously a Saturday, and in memory of Sargent's choral work, a large-scale choral piece is customarily given. Beyond the world of music, a school and a charity were named after him: the Malcolm Sargent Primary School in Stamford and the Malcolm Sargent Cancer Fund for Children. Merging with another charity (Cancer and Leukaemia in Childhood) in 2005, it was renamed CLIC Sargent. In 2021 the charity was renamed again as

Since 1968, the year after Sargent's death, the Proms have begun on a Friday evening rather than as previously a Saturday, and in memory of Sargent's choral work, a large-scale choral piece is customarily given. Beyond the world of music, a school and a charity were named after him: the Malcolm Sargent Primary School in Stamford and the Malcolm Sargent Cancer Fund for Children. Merging with another charity (Cancer and Leukaemia in Childhood) in 2005, it was renamed CLIC Sargent. In 2021 the charity was renamed again as

Although the heyday of live performances of Sargent's Coleridge-Taylor signature piece at the Albert Hall was by then long gone, Sargent, the Royal Choral Society and the Philharmonia made a stereo recording in 1962 of '' Hiawatha's Wedding Feast'', which has been reissued on CD. In 1963, Sargent recorded Gay's ''

Although the heyday of live performances of Sargent's Coleridge-Taylor signature piece at the Albert Hall was by then long gone, Sargent, the Royal Choral Society and the Philharmonia made a stereo recording in 1962 of '' Hiawatha's Wedding Feast'', which has been reissued on CD. In 1963, Sargent recorded Gay's ''

"Instruments of the Orchestra"

British Film Institute. Retrieved 19 November 2014

Biography, photos.

at the ''Memories of the D'Oyly Carte'' website

* ttp://www.classicstoday.com/digest/pdigest.asp?perfidx=3536 Links to reviews to Sargent recordings by Classics Today magazine

Searchable lists of Sargent's performances at the BBC Proms

Leicester Symphony Orchestra

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sargent, Malcolm 1895 births 1967 deaths 20th-century British conductors (music) Academics of the Royal College of Music Alumni of Durham University British Army personnel of World War I BBC Symphony Orchestra Conductors associated with the BBC Proms Conductors (music) awarded knighthoods Durham Light Infantry soldiers English choral conductors Knights Bachelor Musicians from Kent Musicians from Leicestershire Burials in Lincolnshire People educated at Stamford School People from Ashford, Kent People from Melton Mowbray Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists English conductors (music) British male conductors (music) Deaths from pancreatic cancer Associates of the Royal College of Organists 20th-century male musicians Classical musicians associated with the BBC

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent (29 April 1895 – 3 October 1967) was an English conductor, organist and composer widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works. The musical ensembles with which he was associated included the

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent (29 April 1895 – 3 October 1967) was an English conductor, organist and composer widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works. The musical ensembles with which he was associated included the Ballets Russes

The Ballets Russes () was an itinerant ballet company begun in Paris that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. The company never performed in Russia, where the Revolution disrupted society. ...

, the Huddersfield Choral Society, the Royal Choral Society

The Royal Choral Society (RCS) is an amateur choir, based in London.

History

Formed soon after the opening of the Royal Albert Hall in 1871, the choir gave its first performance as the Royal Albert Hall Choral Society on 8 May 1872 – the choir' ...

, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company is a professional British light opera company that, from the 1870s until 1982, staged Gilbert and Sullivan's Savoy operas nearly year-round in the UK and sometimes toured in Europe, North America and elsewhere. Th ...

, and the London Philharmonic

The London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) is one of five permanent symphony orchestras based in London. It was founded by the conductors Sir Thomas Beecham and Malcolm Sargent in 1932 as a rival to the existing London Symphony and BBC Symphon ...

, Hallé, Liverpool Philharmonic

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic is a music organisation based in Liverpool, England, that manages a professional symphony orchestra, a concert venue, and extensive programmes of learning through music. Its orchestra, the Royal Liverpool Philharmon ...

, BBC Symphony and Royal Philharmonic

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London, that performs and produces primarily classic works.

The RPO was established by Thomas Beecham in 1946. In its early days, the orchestra secured profitable ...

orchestras. Sargent was held in high esteem by choirs and instrumental soloists, but because of his high standards and a statement that he made in a 1936 interview disputing musicians' rights to tenure, his relationship with orchestral players was often uneasy. Despite this, he was co-founder of the London Philharmonic, was the first conductor of the Liverpool Philharmonic as a full-time ensemble, and played an important part in saving the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra from disbandment in the 1960s.

As chief conductor of London's internationally famous summer music festival the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts ("the Proms") from 1947 to 1967, Sargent was one of the best-known English conductors. When he took over the Proms, he and two assistants conducted the two-month season between them. By the time he died, he was assisted by a large international roster of guest conductors.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Sargent turned down an offer of a musical directorship in Australia and returned to Britain to bring music to as many people as possible as his contribution to national morale. His fame extended beyond the concert hall: to the British public, he was a familiar broadcaster in BBC radio discussion programmes, and generations of Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan was a Victorian era, Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900), who jointly created fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which ...

devotees have known his recordings of the most popular Savoy Opera

Savoy opera was a style of comic opera that developed in Victorian England in the late 19th century, with W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan as the original and most successful practitioners. The name is derived from the Savoy Theatre, which impr ...

s. He toured widely throughout the world and was noted for his skill as a conductor, his championship of British composers, and his debonair appearance, which won him the nickname "Flash Harry".

Life and career

Sargent's parents lived inStamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford is a town and civil parish in the South Kesteven District of Lincolnshire, England. The population at the 2011 census was 19,701 and estimated at 20,645 in 2019. The town has 17th- and 18th-century stone buildings, older timber-framed ...

, but he was born in Ashford Ashford may refer to:

Places

Australia

*Ashford, New South Wales

*Ashford, South Australia

*Electoral district of Ashford, South Australia

Ireland

*Ashford, County Wicklow

*Ashford Castle, County Galway

United Kingdom

*Ashford, Kent, a town

**B ...

, in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

while his mother was staying with a family friend. He was the elder child and only son of Henry Edward Sargent (1863–1936) and his wife Agnes, ''née'' Hall (1860–1942). Henry Sargent was chief clerk at a Stamford coal merchant, an amateur musician and local church organist; before their marriage his wife had been the matron of the Stamford High School for Girls. The young Sargent won a scholarship to Stamford School

Stamford School is an independent school for boys in Stamford, Lincolnshire in the English public school tradition. Founded in 1532, it has been a member of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference since 1920. With the girls-only S ...

, where he was a pupil from 1907 to 1912. At the same time he was preparing for the musical career his father envisaged for him. He studied piano and organ, and joined the local amateur operatic society, making his stage debut in ''The Mikado

''The Mikado; or, The Town of Titipu'' is a comic opera in two acts, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert, their ninth of fourteen operatic collaborations. It opened on 14 March 1885, in London, where it ran at the ...

'' aged 13 and conducting for the first time the following year when the regular conductor was unavailable. On leaving school, Sargent was articled

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

to Haydn Keeton, organist of Peterborough Cathedral

Peterborough Cathedral, properly the Cathedral Church of St Peter, St Paul and St Andrew – also known as Saint Peter's Cathedral in the United Kingdom – is the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Peterborough, dedicated to Saint Peter, Saint Pau ...

, and was one of the last musicians to be trained in that traditional way.Armstrong, Thomas"Sargent, Sir (Harold) Malcolm Watts (1895–1967), conductor"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2021 At the age of 16 he gained his diploma as Associate of the

Royal College of Organists

The Royal College of Organists (RCO) is a charity and membership organisation based in the United Kingdom, with members worldwide. Its role is to promote and advance organ playing and choral music, and it offers music education, training and de ...

, and at 18 he was awarded the degree of Bachelor of Music

Bachelor of Music (BM or BMus) is an academic degree awarded by a college, university, or conservatory upon completion of a program of study in music. In the United States, it is a professional degree, and the majority of work consists of pre ...

by the University of Durham

, mottoeng = Her foundations are upon the holy hills ( Psalm 87:1)

, established = (university status)

, type = Public

, academic_staff = 1,830 (2020)

, administrative_staff = 2,640 (2018/19)

, chancellor = Sir Thomas Allen

, vice_cha ...

.Crichton, Ronald"Sargent, Sir (Harold) Malcolm"

''Grove Music Online'', Oxford University Press, 2001. Retrieved 14 March 2021

Early career

Sargent worked first as an organist at

Sargent worked first as an organist at St Mary's Church, Melton Mowbray

St Mary is the parish church of Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire. The large medieval church, described as "one of the finest parish churches in Leicestershire", suffered from a poor Victorian restoration, and was left in a poor state of repair and d ...

, Leicestershire, from 1914 to 1924, except for eight months in 1918 when he served as a private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

in the Durham Light Infantry

The Durham Light Infantry (DLI) was a light infantry regiment of the British Army in existence from 1881 to 1968. It was formed in 1881 under the Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 68th (Durham) Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry) and t ...

during the First World War. He was chosen for the organist post over more than 150 other applicants. In addition to his organ playing he worked on many musical projects in Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

, Melton Mowbray and Stamford, where he not only conducted but also produced the operas of Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan was a Victorian era, Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900), who jointly created fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which ...

and others for amateur societies. The Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

and his entourage often hunted in Leicestershire and watched the annual Gilbert and Sullivan productions there, together with the Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of English (later British) monarchs. The equivalent title in the Scottish peerage was ...

and other members of the Royal Family. At the age of 24 Sargent became England's youngest Doctor of Music

The Doctor of Music degree (D.Mus., D.M., Mus.D. or occasionally Mus.Doc.) is a higher doctorate awarded on the basis of a substantial portfolio of compositions and/or scholarly publications on music. Like other higher doctorates, it is granted b ...

, with a degree from Durham.

Sargent's break came when Sir Henry Wood

Sir Henry Joseph Wood (3 March 186919 August 1944) was an English conductor best known for his association with London's annual series of promenade concerts, known as the The Proms, Proms. He conducted them for nearly half a century, introd ...

visited the De Montfort Hall, Leicester, early in 1921 with the Queen's Hall

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect Thomas Knightley, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. Fro ...

orchestra. As it was his custom to commission a piece from a local composer, Wood invited Sargent to write a piece. Sargent did so – a tone poem

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music, usually in a single continuous movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, landscape, or other (non-musical) source. The German term ''T ...

, ''An Impression on a Windy Day'', a seven-minute orchestral '' allegro impetuoso''. He completed it too late for Wood to have enough time to learn it, and Wood called on him to conduct the first performance. Wood recognised not only the worth of the piece but also Sargent's talent as a conductor and gave him the chance to make his London debut, conducting the work at the Proms

The BBC Proms or Proms, formally named the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts Presented by the BBC, is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert Hal ...

– the annual season of the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts – in the Queen's Hall on 11 October of the same year.

Sargent as composer attracted favourable notice in a Prom season when other composer-conductors included Gustav Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst (born Gustavus Theodore von Holst; 21 September 1874 – 25 May 1934) was an English composer, arranger and teacher. Best known for his orchestral suite ''The Planets'', he composed many other works across a range ...

with his ''Planets

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a youn ...

'' suite, and the next year Wood included Sargent's " Nocturne and Scherzo

A scherzo (, , ; plural scherzos or scherzi), in western classical music, is a short composition – sometimes a movement from a larger work such as a symphony or a sonata. The precise definition has varied over the years, but scherzo often re ...

" in the Proms programme, also conducted by the composer. Sargent was invited to conduct his ''Impression'' again in the 1923 season, but it was as a conductor that he made the greater impact. On the advice of Wood, among others, he soon abandoned composition in favour of conducting. He founded the amateur Leicester Symphony Orchestra in 1922, which he continued to conduct until 1939. Under Sargent, the orchestra's prestige grew until it was able to obtain such top-flight soloists as Alfred Cortot

Alfred Denis Cortot (; 26 September 187715 June 1962) was a French pianist, conductor, and teacher who was one of the most renowned classical musicians of the 20th century. A pianist of massive repertory, he was especially valued for his poetic ...

, Artur Schnabel, Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

, Guilhermina Suggia

Guilhermina Augusta Xavier de Medim Suggia Carteado Mena, known as Guilhermina Suggia, (27 June 1885 – 30 July 1950) was a Portuguese cellist. She studied in Paris, France with Pablo Casals, and built an international reputation. She spent many ...

and Benno Moiseiwitsch

Benno Moiseiwitsch CBE (22 February 18909 April 1963) was a Russian-born British pianist.

Biography

Moiseiwitsch was born to Jewish parents in Odessa, Russian Empire (today part of Ukraine), and began his studies at age seven with Dmitry Klim ...

. Moiseiwitsch gave Sargent piano lessons without charge, judging him talented enough to make a successful career as a concert pianist, but Sargent chose a conducting career. At the instigation of Wood and Adrian Boult

Sir Adrian Cedric Boult, CH (; 8 April 1889 – 22 February 1983) was an English conductor. Brought up in a prosperous mercantile family, he followed musical studies in England and at Leipzig, Germany, with early conducting work in Londo ...

he became a lecturer at the Royal College of Music

The Royal College of Music is a conservatoire established by royal charter in 1882, located in South Kensington, London, UK. It offers training from the undergraduate to the doctoral level in all aspects of Western Music including perform ...

in London in 1923.

National fame

In the 1920s Sargent became one of the best-known English conductors. In London, he succeeded Boult as conductor of the Robert Mayer Concerts for Children from 1924 to 1939. In the provinces he conducted the British National Opera Company in '' The Mastersingers'' on tour in 1924 and 1925, winning praise from music critics around the country. In 1925 he conducted his first broadcast performance for the BBC: more than two thousand more followed over the next four decades. In 1926 Sargent began an association with the

In 1926 Sargent began an association with the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company is a professional British light opera company that, from the 1870s until 1982, staged Gilbert and Sullivan's Savoy operas nearly year-round in the UK and sometimes toured in Europe, North America and elsewhere. Th ...

that lasted, on and off, for the rest of his life. He conducted London seasons at the Prince's Theatre

The Shaftesbury Theatre is a West End theatre, located on Shaftesbury Avenue, in the London Borough of Camden. Opened in 1911 as the New Prince's Theatre, it was the last theatre to be built in Shaftesbury Avenue.

History

The theatre was d ...

in 1926 and the newly rebuilt Savoy Theatre

The Savoy Theatre is a West End theatre in the Strand in the City of Westminster, London, England. The theatre was designed by C. J. Phipps for Richard D'Oyly Carte and opened on 10 October 1881 on a site previously occupied by the Savoy P ...

in 1929–30. He was criticised by ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' for allegedly adding "gags" to the Gilbert and Sullivan scores, although the writer praised the crispness of the ensemble, the "musicalness" of the performance and the beauty of the overture. Rupert D'Oyly Carte wrote to the paper stating that Sargent had worked from Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 comic opera, operatic Gilbert and Sullivan, collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinaf ...

's manuscript scores and had merely brought out the "details of the orchestration" exactly as Sullivan had written them. Some of the principal cast members objected to Sargent's fast tempi, at least at first. The D'Oyly Carte seasons brought Sargent's name to a wider public with an early BBC radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927). The service provides national radio stations covering ...

relay of ''The Mikado

''The Mikado; or, The Town of Titipu'' is a comic opera in two acts, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert, their ninth of fourteen operatic collaborations. It opened on 14 March 1885, in London, where it ran at the ...

'' in 1926 heard by up to eight million people. ''The Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after bei ...

'' commented that this was "probably the largest audience that has ever heard anything at one time in the history of the world".

In 1927 Sergei Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev ( ; rus, Серге́й Па́влович Дя́гилев, , sʲɪˈrɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪdʑ ˈdʲæɡʲɪlʲɪf; 19 August 1929), usually referred to outside Russia as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic, pa ...

engaged Sargent to conduct for the Ballets Russes

The Ballets Russes () was an itinerant ballet company begun in Paris that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. The company never performed in Russia, where the Revolution disrupted society. ...

, sharing the conducting with Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential 20th-century clas ...

and Sir Thomas Beecham. In 1928 Sargent was appointed conductor of the Royal Choral Society

The Royal Choral Society (RCS) is an amateur choir, based in London.

History

Formed soon after the opening of the Royal Albert Hall in 1871, the choir gave its first performance as the Royal Albert Hall Choral Society on 8 May 1872 – the choir' ...

; he retained this post for four decades until his death. The society was famous in the 1920s and 1930s for staged performances of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor's ''Hiawatha

Hiawatha ( , also : ), also known as Ayenwathaaa or Aiionwatha, was a precolonial Native American leader and co-founder of the Iroquois Confederacy. He was a leader of the Onondaga people, the Mohawk people, or both. According to some account ...

'' at the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

, a work with which Sargent's name soon became synonymous.

Elizabeth Courtauld, wife of the industrialist and art collector Samuel Courtauld, promoted a popular series of subscription concerts beginning in 1929 and on Schnabel's advice engaged Sargent as chief conductor, with guest conductors including

Elizabeth Courtauld, wife of the industrialist and art collector Samuel Courtauld, promoted a popular series of subscription concerts beginning in 1929 and on Schnabel's advice engaged Sargent as chief conductor, with guest conductors including Bruno Walter

Bruno Walter (born Bruno Schlesinger, September 15, 1876February 17, 1962) was a German-born conductor, pianist and composer. Born in Berlin, he escaped Nazi Germany in 1933, was naturalised as a French citizen in 1938, and settled in the U ...

, Otto Klemperer

Otto Nossan Klemperer (14 May 18856 July 1973) was a 20th-century conductor and composer, originally based in Germany, and then the US, Hungary and finally Britain. His early career was in opera houses, but he was later better known as a concer ...

and Stravinsky. The Courtauld-Sargent concerts, as they became known, were aimed at people who had not previously attended concerts. They attracted large audiences, bringing Sargent's name before another section of the public. In addition to the core repertory, Sargent introduced new works by Bliss, Honegger

Arthur Honegger (; 10 March 1892 – 27 November 1955) was a Swiss composer who was born in France and lived a large part of his life in Paris. A member of Les Six, his best known work is probably ''Antigone'', composed between 1924 and 1927 to ...

, Kodály, Martinů, Prokofiev

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev; alternative transliterations of his name include ''Sergey'' or ''Serge'', and ''Prokofief'', ''Prokofieff'', or ''Prokofyev''., group=n (27 April .S. 15 April1891 – 5 March 1953) was a Russian composer, p ...

, Szymanowski and Walton, among others. At first, the London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

was engaged for these concerts, but the orchestra, a self-governing co-operative, refused to replace key players whom Sargent considered sub-standard. As a result, in conjunction with Beecham, Sargent set about establishing a new orchestra, the London Philharmonic

The London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) is one of five permanent symphony orchestras based in London. It was founded by the conductors Sir Thomas Beecham and Malcolm Sargent in 1932 as a rival to the existing London Symphony and BBC Symphon ...

.

In these years Sargent tackled a wide repertoire, recording much of it, but he was particularly noted for performances of choral pieces, most notably Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concertos. Handel received his training i ...

's ''Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

'', performed with large choruses and orchestras. He joked that his career was based on "the two M's – ''Messiah'' and ''Mikado''". He promoted British music, as he would throughout his career, and conducted the premieres of ''At the Boar's Head

''At the Boar's Head'' is an opera in one act by the English composer Gustav Holst, his op. 42. Holst himself described the work as "A Musical Interlude in One Act". The libretto, by the composer himself, is based on Shakespeare's ''Henry IV, Pa ...

'' (1925) by Holst; '' Hugh the Drover'' (1924); ''Sir John in Love

''Sir John in Love'' is an opera in four acts by the English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. The libretto, by the composer himself, is based on Shakespeare's ''The Merry Wives of Windsor'' and supplemented with texts by Philip Sidney, Thomas Mi ...

'' (1929) by Vaughan Williams; and Walton's cantata

A cantata (; ; literally "sung", past participle feminine singular of the Italian verb ''cantare'', "to sing") is a vocal composition with an instrumental accompaniment, typically in several movements, often involving a choir.

The meaning o ...

'' Belshazzar's Feast'' (at the Leeds Triennial Festival of 1931). The chorus for the last of these found Walton's music difficult, but Sargent engaged them with it, telling them they were helping to make musical history, and reminding them that Berlioz's Requiem

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

and Elgar's ''The Dream of Gerontius

''The Dream of Gerontius'', Op. 38, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by Edward Elgar in 1900, to text from the poem by John Henry Newman. It relates the journey of a pious man's soul from his deathbed to his judgment b ...

'' had been considered impossible at first. He drew from them and the LSO what ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' described as "a performance of unflagging energy and amazing volume of tone under Dr. Malcolm Sargent",

Difficult years and war years

In October 1932 Sargent suffered a near-fatal attack of

In October 1932 Sargent suffered a near-fatal attack of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

. For almost two years he was unable to work, and it was only later in the 1930s that he returned to the concert scene. In 1936 he conducted his first opera at Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

, Gustave Charpentier's '' Louise''. He did not conduct opera there again until 1954, with Walton's ''Troilus and Cressida

''Troilus and Cressida'' ( or ) is a play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1602.

At Troy during the Trojan War, Troilus and Cressida begin a love affair. Cressida is forced to leave Troy to join her father in the Greek camp. Me ...

'',''The Times'' obituary notice, 4 October 1967, p. 12 although he did conduct the incidental music for a dramatisation of ''The Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in English literature and a progenitor of t ...

'' given at the Royal Opera House in 1948.

Although Sargent was popular with choral singers, his relations with orchestras were sometimes strained. After giving a ''Daily Telegraph

Daily or The Daily may refer to:

Journalism

* Daily newspaper, newspaper issued on five to seven day of most weeks

* ''The Daily'' (podcast), a podcast by ''The New York Times''

* ''The Daily'' (News Corporation), a defunct US-based iPad new ...

'' interview in 1936 in which he said that an orchestral musician did not deserve a "job for life" and should "give of his lifeblood with every bar he plays," Sargent lost much favour with orchestral musicians. They were particularly aggrieved because of their support of him during his long illness, and thereafter he faced frequent hostility from British orchestras.Aldous, p. 83

Being popular in Australia with players as well as the public, Sargent made three lengthy tours of Australia and New Zealand, beginning in 1936. He was on the point of accepting a permanent appointment with the

Being popular in Australia with players as well as the public, Sargent made three lengthy tours of Australia and New Zealand, beginning in 1936. He was on the point of accepting a permanent appointment with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) is the national broadcaster of Australia. It is principally funded by direct grants from the Australian Government and is administered by a government-appointed board. The ABC is a publicly-owne ...

when, at the outbreak of the Second World War, he felt it his duty to return to his country, resisting strong pressure from the Australian media for him to stay. During the war, Sargent directed the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester (1939–1942) and the Liverpool Philharmonic

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic is a music organisation based in Liverpool, England, that manages a professional symphony orchestra, a concert venue, and extensive programmes of learning through music. Its orchestra, the Royal Liverpool Philharmon ...

(1942–1948) and became a popular BBC Home Service

The BBC Home Service was a national and regional radio station that broadcast from 1939 until 1967, when it was replaced by BBC Radio 4.

History

1922–1939: Interwar period

Between the early 1920s and the outbreak of World War II, the BBC ...

radio broadcaster, particularly in the discussion programme ''The Brains Trust

''The Brains Trust'' was an informational BBC radio and later television programme popular in the United Kingdom during the 1940s and 1950s, on which a panel of experts tried to answer questions sent in by the audience.

History

The series was ...

''. He helped boost public morale during the war by extensive concert tours around the country conducting for nominal fees. On one occasion, an air raid interrupted a performance of Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

's Symphony No. 7. Sargent stopped the orchestra, reassured the audience that they were safer inside the hall than fleeing outside, and resumed conducting. He later said that no orchestra had ever played so well and that no audience in his experience had ever listened so intently. In May 1941 he conducted the last performance heard in the Queen's Hall. Following an afternoon concert comprising the ''Enigma Variations

Edward Elgar composed his ''Variations on an Original Theme'', Op. 36, popularly known as the ''Enigma Variations'', between October 1898 and February 1899. It is an orchestral work comprising fourteen variations on an original theme.

Elgar ...

'' and ''The Dream of Gerontius'' – praised by ''The Times'' as "performances of real distinction" – the hall was destroyed during an overnight incendiary raid.

In 1945 Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini (; ; March 25, 1867January 16, 1957) was an Italian conductor. He was one of the most acclaimed and influential musicians of the late 19th and early 20th century, renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orch ...

invited Sargent to conduct the NBC Symphony Orchestra

The NBC Symphony Orchestra was a radio orchestra conceived by David Sarnoff, the president of the Radio Corporation of America, especially for the conductor Arturo Toscanini. The NBC Symphony performed weekly radio concert broadcasts with Tosc ...

. In four concerts Sargent chose to present all English music, with the exception of Sibelius

Jean Sibelius ( ; ; born Johan Julius Christian Sibelius; 8 December 186520 September 1957) was a Finnish composer of the late Romantic and early-modern periods. He is widely regarded as his country's greatest composer, and his music is often ...

's Symphony No. 1 and Dvořák's Symphony No. 7. Two concertos, Walton's Viola Concerto with William Primrose, and Elgar's Violin Concerto with Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi or Jehudi (Hebrew: יהודי, endonym for Jew) is a common Hebrew name:

* Yehudi Menuhin (1916–1999), violinist and conductor

** Yehudi Menuhin School, a music school in Surrey, England

** Who's Yehoodi?, a catchphrase referring to t ...

, were programmed as part of these concerts. Menuhin judged Sargent's conducting of the latter "the next best to Elgar in this work".

The Proms

Sargent was made aKnight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised orders of chivalry; it is a part of the British honours system. Knights Bachelor are ...

in the 1947 Birthday Honours

The 1947 King's Birthday Honours were appointments by many of the Commonwealth Realms of King George VI to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of those countries. The appointments were made "on the occasion o ...

for services to music. He performed in numerous English-speaking countries during the post-war years and continued to promote British composers, conducting the premieres of Walton's opera, ''Troilus and Cressida'' (1954), and Vaughan Williams's Symphony No. 9 (1958).

Sargent was a dominant figure at the Proms in the post-war era. He was chief conductor of the Proms from 1947 until his death in 1967, taking part in 514 concerts. A 1947 Prom under his baton was the first concert to be televised in Britain.Maloney, Chapter 8 As conductor of the Proms, Sargent gained his widest fame, making the "Last Night" of each season into a high-ratings broadcast celebration aimed at ordinary audiences, a popular, theatrical flag-waving extravaganza presided over by himself. He was noted for his witty addresses in which he good-naturedly chided the noisy promenaders. In his programmes he often conducted choral music and music by British composers, but his range was broad: the BBC's official history of the Proms lists selected programmes from this period showing Sargent conducting works by Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the ''Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard wor ...

, Sibelius, Dvořák, Berlioz, Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one o ...

, Rimsky-Korsakov, Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wag ...

and Kodály in three successive programmes. During his chief conductorship, prestigious foreign conductors and orchestras began to perform regularly at the Proms. In his first season in charge, Sargent and two assistant conductors conducted all the concerts among them; by 1966 there were Sargent and 25 other conductors. Those making their Prom debuts in the Sargent years included Carlo Maria Giulini

Carlo Maria Giulini (; 9 May 1914 – 14 June 2005) was an Italian conductor.

From the age of five, when he began to play the violin, Giulini's musical education was expanded when he began to study at Italy's foremost conservatory, the Conserva ...

, Georg Solti

Sir Georg Solti ( , ; born György Stern; 21 October 1912 – 5 September 1997) was a Hungarian-British orchestral and operatic conductor, known for his appearances with opera companies in Munich, Frankfurt and London, and as a long-servin ...

, Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appear ...

, Rudolf Kempe

Rudolf Kempe (14 June 1910 – 12 May 1976) was a German conductor.

Biography

Kempe was born in Dresden, where from the age of fourteen he studied at the Dresden State Opera School. He played oboe in the opera orchestra of Dortmund and ...

, Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mo ...

and Bernard Haitink

Bernard Johan Herman Haitink (; 4 March 1929 – 21 October 2021) was a Dutch conductor and violinist. He was the principal conductor of several international orchestras, beginning with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1961. He moved to Lon ...

.

Sargent was chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra

The BBC Symphony Orchestra (BBC SO) is a British orchestra based in London. Founded in 1930, it was the first permanent salaried orchestra in London, and is the only one of the city's five major symphony orchestras not to be self-governing. T ...

from 1950 to 1957, succeeding Boult. He was not the BBC's first choice, but John Barbirolli

Sir John Barbirolli ( Giovanni Battista Barbirolli; 2 December 189929 July 1970) was a British conductor and cellist. He is remembered above all as conductor of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester, which he helped save from dissolution in 194 ...

and Rafael Kubelik

Rafael may refer to:

* Rafael (given name) or Raphael, a name of Hebrew origin

* Rafael, California

* Rafael Advanced Defense Systems, Israeli manufacturer of weapons and military technology

* Hurricane Rafael, a 2012 hurricane

Fiction

* ' ...

turned the post down, and it went to Sargent, despite reservations about his commitment. Unlike Boult he refused to join the staff of the BBC and remained a freelance, accepting other engagements as he pleased. The historian of the BBC Asa Briggs

Asa Briggs, Baron Briggs (7 May 1921 – 15 March 2016) was an English historian. He was a leading specialist on the Victorian era, and the foremost historian of broadcasting in Britain. Briggs achieved international recognition during his lon ...

has written, "Sargent sometimes ruffled the orchestra in a way that Boult had never done. Indeed there were many people inside the BBC who profoundly regretted Boult's departure." Briggs adds that Sargent was the target of criticism from the BBC's own Music Department for "not devoting enough time to the orchestra".Briggs, p. 230 The music journalist Norman Lebrecht

Norman Lebrecht (born 11 July 1948) is a British music journalist and author who specializes in classical music. He is best known as the owner of the classical music blog, ''Slipped Disc'', where he frequently publishes articles. Unlike other ...

goes so far as to say that Sargent "almost wrecked" the BBC orchestra. The orchestra objected to his "autocratic and ''prima-donna'' attitude towards orchestral players" and flatly refused to accede to his demand that they all stand up when he came on to the platform. He rapidly became equally unpopular with the BBC music department, ignoring its agenda and pursuing his own.Cox, p. 164 A senior BBC manager wrote:

It did not help that Sargent was universally acknowledged to be at his finest in choral music.Shore, p. 153 His reputation in big works for chorus and orchestra such as ''The Dream of Gerontius'', ''Hiawatha'' and ''Belshazzar's Feast'' was unrivalled, and his large-scale performances of Handel oratorios were assured packed houses. But his regular programming of such works did nothing to lift the spirits of the BBC SO: orchestral musicians regarded playing the instrumental accompaniment for large choirs as drudgery.

Although there were complaints within the BBC, there was praise from outside it for Sargent's work with the orchestra. His biographer Reid wrote, "Sargent's liveliness and drive soon gave BBC playing a gloss and briskness which had not been conspicuous before". Another biographer, Aldous, wrote, "Everywhere Sargent and the orchestra performed there were ovations, laurel wreaths and terrific reviews." The orchestra's reputation both in Britain and internationally grew during Sargent's tenure. Briggs records that conductor had "great moments of triumph ... both at festivals overseas and during the Proms". In the 1950s and 1960s he made many recordings with the BBC Symphony, as well as other ensembles, as described below. In this period, also, he conducted the concerts that opened the Royal Festival Hall

The Royal Festival Hall is a 2,700-seat concert, dance and talks venue within Southbank Centre in London. It is situated on the South Bank of the River Thames, not far from Hungerford Bridge, in the London Borough of Lambeth. It is a Grade I li ...

in 1951 and returned to the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company for the summer 1951 Festival of Britain

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition and fair that reached millions of visitors throughout the United Kingdom in the summer of 1951. Historian Kenneth O. Morgan says the Festival was a "triumphant success" during which people:

...

season at the Savoy Theatre and the winter 1961–62 and 1963–64 seasons at the Savoy. In August 1956 the BBC announced that he would be replaced as Chief Conductor of the BBC orchestra by Rudolf Schwarz. Sargent was given the title of "Chief Guest Conductor" and he remained Conductor-in-Chief of the Proms.

Overseas and last years

Sargent made two tours of South America. In 1950 he conducted in

Sargent made two tours of South America. In 1950 he conducted in Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, Montevideo

Montevideo () is the capital and largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . Montevideo is situated on the southern co ...

, Rio de Janeiro and Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whos ...

. His programmes included Vaughan Williams's ''London'' and 6th

6 (six) is the natural number following 5 and preceding 7. It is a composite number and the smallest perfect number.

In mathematics

Six is the smallest positive integer which is neither a square number nor a prime number; it is the second ...

Symphonies; Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

's Symphony No. 88, Beethoven's Symphony No. 8, Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

's ''Jupiter'' symphony, Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. Despite his short lifetime, Schubert left behind a vast ''oeuvre'', including more than 600 secular vocal wor ...

's 5th

Fifth is the ordinal form of the number five.

Fifth or The Fifth may refer to:

* Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as in the expression "pleading the Fifth"

* Fifth column, a political term

* Fifth disease, a contagious rash tha ...

, Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped with ...

's 2nd

A second is the base unit of time in the International System of Units (SI).

Second, Seconds or 2nd may also refer to:

Mathematics

* 2 (number), as an ordinal (also written as ''2nd'' or ''2d'')

* Second of arc, an angular measurement unit, ...

and 4th and Sibelius's 5th

Fifth is the ordinal form of the number five.

Fifth or The Fifth may refer to:

* Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as in the expression "pleading the Fifth"

* Fifth column, a political term

* Fifth disease, a contagious rash tha ...

symphonies, Elgar's ''Serenade for Strings'', Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

's '' The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra'', Strauss's '' Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks'', Walton's Viola Concerto and Dvořák's Cello Concerto A cello concerto (sometimes called a violoncello concerto) is a concerto for solo cello with orchestra or, very occasionally, smaller groups of instruments.

These pieces have been written since the Baroque era if not earlier. However, unlike instr ...

with Pierre Fournier

Pierre Léon Marie Fournier (24 June 19068 January 1986) was a French cellist who was called the "aristocrat of cellists" on account of his elegant musicianship and majestic sound.

Biography

He was born in Paris, the son of a French Army gen ...

. In 1952 Sargent conducted in all the above-mentioned cities and also in Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

. Half his repertory on that tour consisted of British music and included Delius, Vaughan Williams, Britten, Walton and Handel.

When the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London, that performs and produces primarily classic works.

The RPO was established by Thomas Beecham in 1946. In its early days, the orchestra secured profitable ...

was in danger of extinction after Beecham's death in 1961, Sargent played a major part in saving it, doing much to win back the good opinion of orchestral players that he had lost because of his 1936 interview. In the 1960s, he toured Russia, the United States, Canada, Turkey, Israel, India, the Far East and Australia. By the mid-1960s his health began to deteriorate. His final conducting appearances were on 6 and 8 July 1967, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) was founded by Theodore Thomas in 1891. The ensemble makes its home at Orchestra Hall in Chicago and plays a summer season at the Ravinia Festival. The music director is Riccardo Muti, who began his tenu ...

at the Ravinia Festival

Ravinia Festival is an outdoor music venue in Highland Park, Illinois. It hosts a series of outdoor concerts and performances every summer from June to September. The first orchestra to perform at Ravinia Festival was the New York Philharmonic unde ...

. On 6 July he conducted Holst's ''The Perfect Fool'', Wieniawski's Second Violin Concerto with Itzhak Perlman

Itzhak Perlman ( he, יצחק פרלמן; born August 31, 1945) is an Israeli-American violinist widely considered one of the greatest violinists in the world. Perlman has performed worldwide and throughout the United States, in venues that hav ...

, and Vaughan Williams's ''A London Symphony''. On 8 July he conducted Vaughan Williams's Overture ''The Wasps'', Delius's ''The Walk to the Paradise Garden'', Prokofiev's Piano Concerto No. 4 with David Bar-Illan, and Sibelius's Symphony No. 2.

Sargent underwent surgery in July 1967 for pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer arises when cells in the pancreas, a glandular organ behind the stomach, begin to multiply out of control and form a mass. These cancerous cells have the ability to invade other parts of the body. A number of types of pancr ...

and made a valedictory appearance at the end of the Last Night of the Proms in September that year, handing over the baton to his successor, Colin Davis

Sir Colin Rex Davis (25 September 1927 – 14 April 2013) was an English conductor, known for his association with the London Symphony Orchestra, having first conducted it in 1959. His repertoire was broad, but among the composers with whom h ...

. He died two weeks later, at the age of 72. He was buried in Stamford cemetery alongside members of his family.

Musical reputation and repertoire

Toscanini, Beecham and many others regarded Sargent as the finest choral conductor in the world. Even orchestral musicians gave him credit: the principal violist of the BBC Symphony Orchestra wrote of him, "He is able to instil into the singers a life and efficiency they never dreamed of. You have only to see the eyes of a choral society screwing into him like hundreds of gimlets to understand what he means to them." Boult thought him "a great all-rounder", but added, "he never developed his potentialities, which were enormous, simply because he didn't think hard enough about music – he never troubled to improve on a successful interpretation. He was too interested in other things, and not single-minded enough about music." Although orchestral players resented Sargent for much of his career after the 1936 interview, instrumental soloists generally liked working with him. The cellist Pierre Fournier called him a "guardian angel" and compared him favourably withGeorge Szell

George Szell (; June 7, 1897 – July 30, 1970), originally György Széll, György Endre Szél, or Georg Szell, was a Hungarian-born American conductor and composer. He is widely considered one of the twentieth century's greatest condu ...

and Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan (; born Heribert Ritter von Karajan; 5 April 1908 – 16 July 1989) was an Austrian conductor. He was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic for 34 years. During the Nazi era, he debuted at the Salzburg Festival, wit ...

. Artur Schnabel, Jascha Heifetz

Jascha Heifetz (; December 10, 1987) was a Russian-born American violinist. Born in Vilnius, he moved while still a teenager to the United States, where his Carnegie Hall debut was rapturously received. He was a virtuoso since childhood. Fritz ...

and Yehudi Menuhin thought similarly highly of him. Cyril Smith

Sir Cyril Richard Smith (28 June 1928 – 3 September 2010) was a prominent British politician who after his death was revealed to have been a prolific serial sex offender against children. A member of the Liberal Party, he was Member of ...

wrote in his autobiography, "...he seems to sense what the pianist wants of the music even before he begins to play it.... He has an incredible speed of mind, and it has always been a great joy, as well as a rare professional experience, to work with him."Review of Sargent's biographies by Stephen Lloyd/ref> For this reason, among others, Sargent was continually in demand as a conductor for concertos. ''The Times'' obituary said Sargent "was of all British conductors in his day the most widely esteemed by the lay public... a fluent, attractive pianist, a brilliant score-reader, a skilful and effective arranger and orchestrator... as a conductor his stick technique was regarded by many as the most accomplished and reliable in the world.... s taste... was moulded by the Victorian cathedral tradition into which he was born." It commented that, in his later years, his interpretations of the standard classical and romantic repertoire were "prepared... down to the last detail" but sometimes "unexuberant", though his performances of "the music composed within his lifetime... remained lucid and continually compelling". The flute player Gerald Jackson wrote, "I feel that altonconducts his own music as well as anyone else, with the possible exception of Sargent, who of course introduced and always makes a big thing of ''Belshazzar's Feast''." The composers whose works Sargent regularly conducted included, from the eighteenth century, Bach, Handel,

Gluck

Christoph Willibald (Ritter von) Gluck (; 2 July 1714 – 15 November 1787) was a composer of Italian and French opera in the early classical period. Born in the Upper Palatinate and raised in Bohemia, both part of the Holy Roman Empire, he ...

, Mozart and Haydn; and from the nineteenth century, Beethoven, Berlioz, Schubert, Schumann

Robert Schumann (; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career a ...

, Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include sym ...

, Brahms, Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

, Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

, Smetana, Sullivan and Dvořák. From the twentieth century, British composers in his repertoire included Bliss, Britten, Delius, Elgar (a favourite, especially Elgar's choral works ''The Dream of Gerontius'', '' The Apostles'' and '' The Kingdom'' and symphonies), Holst, Tippett, Vaughan Williams and Walton. With the exception of Alban Berg's Violin Concerto, Sargent avoided the works of the Second Viennese School

The Second Viennese School (german: Zweite Wiener Schule, Neue Wiener Schule) was the group of composers that comprised Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils, particularly Alban Berg and Anton Webern, and close associates in early 20th-century Vienn ...

but programmed works by Bartók, Dohnányi, Hindemith, Honegger, Kodály, Martinů, Poulenc

Francis Jean Marcel Poulenc (; 7 January 189930 January 1963) was a French composer and pianist. His compositions include songs, solo piano works, chamber music, choral pieces, operas, ballets, and orchestral concert music. Among the best-kno ...

, Prokofiev, Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich, Sibelius, Strauss, Stravinsky and Szymanowski.

Personal life, reputation and legacy

Private life

In 1923 Sargent married Eileen Laura Harding Horne (1898–1977). She was the younger daughter of Frederick William Horne – a prosperous miller, farmer, coal merchant and carter – and the niece of Evangeline Astley Cooper ofHambleton Hall

Hambleton Hall is a hotel and restaurant located in the village of Hambleton, Rutland, Hambleton close to Oakham, Rutland, England. The restaurant has held one star in the Michelin Guide since 1982.

The Hall was built in 1881 as a hunting box b ...

in Rutland

Rutland () is a ceremonial county and unitary authority in the East Midlands, England. The county is bounded to the west and north by Leicestershire, to the northeast by Lincolnshire and the southeast by Northamptonshire.

Its greatest len ...

, where she lived in the early 1920s. Sargent was a guest there in the same period, and his name occurs alongside hers in local press reports of social gatherings such as hunt ball

A hunt ball is an annual event hosted by a mounted fox hunting club, most of which are located in Britain and the United States. These balls are traditionally held around the holiday season, which is why many American Hunts mark the end of the hu ...

s. When they married, the press headlined her name rather than that of her still little-known husband. The couple were married at St Mary's Church, Drinkstone, the service conducted by the bride's uncle, who, as her grandfather had been, was rector there."Marriage of Miss Eileen Horne", ''The Bury Free Press'', 15 September 1923, p. 11 By 1926, the couple had two children, a daughter, Pamela, who died of polio

Poliomyelitis, commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 70% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe sy ...

in 1944, and a son Peter. Sargent was much affected by his daughter's death, and his recording of Elgar's ''The Dream of Gerontius'' in 1945 was an expression of his grief. The marriage was unhappy and ended in divorce in 1946. Before, during and after his marriage, Sargent was a continual womaniser, which he did not deny. Among his reported affairs were long-standing ones with Diana Bowes-Lyon

The Bowes-Lyon family descends from George Bowes of Gibside and Streatlam Castle ''(1701–1760)'', a County Durham landowner and politician, through John Bowes, 9th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne, chief of the Clan Lyon. Following the marriage ...

, Princess Marina and Edwina Mountbatten. More casual encounters are typified by the young woman who said, "Promise me that whatever happens I shan't have to go home alone in a taxi with Malcolm Sargent."Lyttelton and Hart-Davis (1981), p. 6

Away from music, Sargent was elected a member of The Literary Society

The Literary Society is a London dining club, founded by William Wordsworth and others in 1807. Its members are generally either prominent figures in English literature or eminent people in other fields with a strong interest in literature. No pa ...

, a dining club founded in 1807 by William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication '' Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

and others. He was also a member of the Beefsteak Club

Beefsteak Club is the name or nickname of several 18th- and 19th-century male dining clubs in Britain and Australia that celebrated the beefsteak as a symbol of patriotic and often Whig concepts of liberty and prosperity.

The first beefsteak clu ...

, for which his proposer was Sir Edward Elgar, the Garrick, and the long-established and aristocratic White's and Pratt's clubs."Sargent, Sir (Harold) Malcolm (Watts)"''Who Was Who'', Oxford University Press, 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2014 His public service appointments included the joint presidency of the London Union of Youth Clubs, and the presidency of the

Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) is a charity operating in England and Wales that promotes animal welfare. The RSPCA is funded primarily by voluntary donations. Founded in 1824, it is the oldest and largest a ...

.

Despite Sargent's vanities and rivalries, he had many friends. Sir Thomas Armstrong

Sir Thomas Armstrong (c. 1633, Nijmegen – 20 June 1684, London) was an English army officer and Member of Parliament executed for treason.Richard L. Greaves, Armstrong, Sir Thomas (bap. 1633, d. 1684), Oxford Dictionary of National Biograph ...

in a 1994 broadcast interview stressed that Sargent "had many good generous virtues; he was kind to many people, and I loved him...". Nevertheless, even friends such as Sir Rupert Hart-Davis, secretary of the Literary Society, considered him a "bounder", and the composer Dame Ethel Smyth called him a "cad". Yet despite his philandering and ambition, Sargent was a deeply religious man all his life and was comforted on his deathbed by visits from the Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers ...

, Donald Coggan and the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

Archbishop of Westminster

The Archbishop of Westminster heads the Roman Catholic Diocese of Westminster, in England. The incumbent is the metropolitan of the Province of Westminster, chief metropolitan of England and Wales and, as a matter of custom, is elected presid ...

, Cardinal Heenan. He also received telephone calls from Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen ...

and Prince Charles

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to a ...

, and had a reconciliation with his son, Peter, from whom he had been estranged.

"Flash Harry"

A number of purported explanations have been advanced for Sargent's nickname, "Flash Harry". Reid opines that it "was first in circulation among orchestral players before the war and that they used it in no spirit of adulation". It may have arisen from his impeccable and stylish appearance – he always wore a red or white carnation in his buttonhole (the carnation is now the symbol of the school named for him). This was perhaps reinforced by his brisk tempi early in his career, and by a story about his racing from one recording session to another. Another explanation, that he was named afterRonald Searle

Ronald William Fordham Searle, CBE, RDI (3 March 1920 – 30 December 2011) was an English artist and satirical cartoonist, comics artist, sculptor, medal designer and illustrator. He is perhaps best remembered as the creator of St Trinian's S ...

's St Trinian's character " Flash Harry", is certainly wrong: Sargent's nickname was current long before the first appearance of the St Trinian's character in 1954. Sargent's devoted fans, the Promenaders, used the nickname in an approving sense, and shortened it to "Flash", though Sargent was not especially fond of the sobriquet, even thus modified.

Beecham and Sargent were allies from the early days of the London Philharmonic to Beecham's final months when they were planning joint concerts. They even happened to share the same birthday. When Sargent was incapacitated by tuberculosis in 1933, Beecham conducted a performance of ''Messiah'' at the Albert Hall to raise money to support his younger colleague. Sargent enjoyed Beecham's company, and took in good part his quips, such as his reference to the image-conscious young conductor Herbert von Karajan as "a kind of musical Malcolm Sargent" and, on learning that Sargent's car was caught in rifle fire in Palestine, "I had no idea the Arabs were so musical." Beecham declared that Sargent "is the greatest choirmaster we have ever produced ... he makes the buggers sing like blazes". And on another occasion he said that Sargent was "the most expert of all our conductors – myself excepted of course".

Honours and memorials

In addition to his own doctorate from Durham, Sargent was awarded honorary degrees by the Universities ofOxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

and by the Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in London, England, is the oldest conservatoire in the UK, founded in 1822 by John Fane and Nicolas-Charles Bochsa. It received its royal charter in 1830 from King George IV with the support of the first Duke ...

, the Royal College of Organists, the Royal College of Music and the Swedish Academy of Music. He was awarded the highest honour of the Royal Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a memb ...

, its Gold Medal, in 1959. Foreign honours included the Order of the Star of the North (Sweden), 1956; the Order of the White Rose

The Order of the White Rose of Finland ( fi, Suomen Valkoisen Ruusun ritarikunta; sv, Finlands Vita Ros’ orden) is one of three official orders in Finland, along with the Order of the Cross of Liberty, and the Order of the Lion of Finland. ...

(Finland), 1965; and Chevalier of France's Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

, 1967.

After his death Sargent was commemorated in a variety of ways. His memorial service in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

in October 1967 was attended by 3,000 people including the royalty of three countries, official representatives from France, South Africa, and Malaysia, and notables as diverse as Princess Marina of Kent; Bridget D'Oyly Carte

Dame Bridget D'Oyly Carte DBE (25 March 1908 – 2 May 1985) was head of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company from 1948 until 1982. She was the granddaughter of the impresario Richard D'Oyly Carte and the only daughter of Rupert D'Oyly Carte.

Thoug ...

; Pierre Boulez; Larry Adler; Elgar's daughter; Beecham's widow; Douglas Fairbanks Junior; Léon Goossens

Léon Jean Goossens, CBE, FRCM (12 June 1897 – 13 February 1988) was an English oboist.

Career

Goossens was born in Liverpool, Lancashire, and studied at Liverpool College of Music and the Royal College of Music. His father was violinist and ...

; the Master of the Queen's Music

Master of the King's Music (or Master of the Queen's Music, or earlier Master of the King's Musick) is a post in the Royal Household of the United Kingdom. The holder of the post originally served the monarch of England, directing the court orche ...

; the Secretary of London Zoo; and representatives of the London orchestras and of the Promenaders. Colin Davis and the BBC Chorus and Symphony Orchestra performed the music.

Since 1968, the year after Sargent's death, the Proms have begun on a Friday evening rather than as previously a Saturday, and in memory of Sargent's choral work, a large-scale choral piece is customarily given. Beyond the world of music, a school and a charity were named after him: the Malcolm Sargent Primary School in Stamford and the Malcolm Sargent Cancer Fund for Children. Merging with another charity (Cancer and Leukaemia in Childhood) in 2005, it was renamed CLIC Sargent. In 2021 the charity was renamed again as

Since 1968, the year after Sargent's death, the Proms have begun on a Friday evening rather than as previously a Saturday, and in memory of Sargent's choral work, a large-scale choral piece is customarily given. Beyond the world of music, a school and a charity were named after him: the Malcolm Sargent Primary School in Stamford and the Malcolm Sargent Cancer Fund for Children. Merging with another charity (Cancer and Leukaemia in Childhood) in 2005, it was renamed CLIC Sargent. In 2021 the charity was renamed again as Young Lives vs Cancer

Young Lives vs Cancer, the operating name for "CLIC Sargent", is a charity in the United Kingdom formed in 2005. Young Lives vs Cancer is the UK's leading cancer charity for children, young people and their families. Its care teams provide speci ...

; it is the UK's leading children's cancer charity. In 1980 the Royal Mail

, kw, Postya Riel, ga, An Post Ríoga

, logo = Royal Mail.svg

, logo_size = 250px

, type = Public limited company

, traded_as =