Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in

Northeast Africa

Northeast Africa, or Northeastern Africa, or Northern East Africa as it was known in the past, encompasses the countries of Africa situated in and around the Red Sea. The region is intermediate between North Africa and East Africa, and encompasses ...

. It borders the

Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to Central African Republic–Chad border, the north, Sudan to Central African Republic–Sudan border, the northeast, South Sudan to Central ...

to the southwest,

Chad

Chad, officially the Republic of Chad, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of North Africa, North and Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to Chad–Libya border, the north, Sudan to Chad–Sudan border, the east, the Central Afric ...

to the west,

Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

to the northwest,

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

to the north, the

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

to the east,

Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

and

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

to the southeast, and

South Sudan

South Sudan (), officially the Republic of South Sudan, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered on the north by Sudan; on the east by Ethiopia; on the south by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Kenya; and on the ...

to the south. Sudan has a population of 50 million people as of 2024 and occupies 1,886,068 square kilometres (728,215 square miles), making it Africa's

third-largest country by area and the third-largest by area in the

Arab League

The Arab League (, ' ), officially the League of Arab States (, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world. The Arab League was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945, initially with seven members: Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt, Kingdom of Iraq, ...

. It was the largest country by area in Africa and the Arab League until the

secession of South Sudan in 2011; since then both titles have been held by

Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

. Sudan's capital and most populous city is

Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum is the capital city of Sudan as well as Khartoum State. With an estimated population of 7.1 million people, Greater Khartoum is the largest urban area in Sudan.

Khartoum is located at the confluence of the White Nile – flo ...

.

The area that is now Sudan witnessed the

Khormusan ( 40000–16000 BC),

Halfan culture ( 20500–17000 BC),

Sebilian ( 13000–10000 BC),

Qadan culture ( 15000–5000 BC), the war of

Jebel Sahaba, the earliest known war in the world, around 11500 BC,

A-Group culture

The A-Group was the first powerful society in Nubia, located in modern northern Sudan and southern Egypt and flourished between the First and Second Cataracts of the Nile in Lower Nubia. It lasted from the 4th millennium BC, reached its clima ...

( 3800–3100 BC),

Kingdom of Kerma ( 2500–1500 BC), the

Egyptian New Kingdom ( 1500–1070 BC), and the

Kingdom of Kush

The Kingdom of Kush (; Egyptian language, Egyptian: 𓎡𓄿𓈙𓈉 ''kꜣš'', Akkadian language, Assyrian: ''Kûsi'', in LXX Χους or Αἰθιοπία; ''Ecōš''; ''Kūš''), also known as the Kushite Empire, or simply Kush, was an an ...

( 785 BC – 350 AD). After the fall of Kush, the

Nubians

Nubians () ( Nobiin: ''Nobī,'' ) are a Nilo-Saharan speaking ethnic group indigenous to the region which is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. They originate from the early inhabitants of the central Nile valley, believed to be one of th ...

formed the three Christian kingdoms of

Nobatia,

Makuria, and

Alodia.

Between the 14th and 15th centuries, most of Sudan was gradually settled by

Arab nomads. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, central and eastern Sudan were dominated by the

Funj sultanate, while

Darfur

Darfur ( ; ) is a region of western Sudan. ''Dār'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f – the region was named Dardaju () while ruled by the Daju, who migrated from Meroë , and it was renamed Dartunjur () when the Tunjur ruled the area. ...

ruled the west and the Ottomans the east. In 1811,

Mamluk

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-so ...

s established a state at

Dunqulah as a base for their

slave trading. Under

Turco-Egyptian rule of Sudan after the 1820s, the practice of trading slaves was entrenched along a north–south axis, with

slave raids taking place in southern parts of the country and slaves being transported to Egypt and the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.

From the 19th century, the entirety of Sudan was conquered by the Egyptians under the

Muhammad Ali dynasty

The Muhammad Ali dynasty or the Alawiyya dynasty was the ruling dynasty of Egypt and Sudan from the 19th to the mid-20th century. It is named after its progenitor, the Albanians, Albanian Muhammad Ali of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, regarded as the fou ...

. Religious-nationalist fervour erupted in the

Mahdist Uprising in which Mahdist forces were eventually defeated by a joint Egyptian-British military force. In 1899, under British pressure, Egypt agreed to share sovereignty over Sudan with the United Kingdom as a

condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership regime in which a building (or group of buildings) is divided into multiple units that are either each separately owned, or owned in common with exclusive rights of occupation by individual own ...

. In effect, Sudan was governed as a British possession.

The

Egyptian revolution of 1952

The Egyptian revolution of 1952, also known as the 1952 coup d'état () and the 23 July Revolution (), was a period of profound political, economic, and societal change in Egypt. On 23 July 1952, the revolution began with the toppling of King ...

toppled the monarchy and demanded the withdrawal of British forces from all of Egypt and Sudan.

Muhammad Naguib, one of the two co-leaders of the revolution and Egypt's first President, was half-Sudanese and had been raised in Sudan. He made securing Sudanese independence a priority of the revolutionary government. The following year, under Egyptian and Sudanese pressure, the British agreed to Egypt's demand for both governments to terminate their shared sovereignty over Sudan and to grant Sudan independence. On 1 January 1956, Sudan was duly declared an independent state.

After Sudan became independent, the

Gaafar Nimeiry

Gaafar Muhammad an-Nimeiry (otherwise spelled in English as Gaafar Nimeiry, Jaafar Nimeiry, or Ja'far Muhammad Numayri; ; 1 January 193030 May 2009) was a Sudanese military officer and politician who served as the fourth president of Sudan, hea ...

regime began

Islamist rule.

This exacerbated the rift between the Islamic North, the seat of the government, and the

Animists and Christians in the South. Differences in language, religion, and political power erupted in a

civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

between government forces, influenced by the

National Islamic Front (NIF), and the southern rebels, whose most influential faction was the

Sudan People's Liberation Army

The South Sudan People's Defence Forces (SSPDF), formerly the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), is the military force of South Sudan. The SPLA was founded as a guerrilla movement against the government of Sudan in 1983 and was a key parti ...

(SPLA), which eventually led to the

independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of ...

of

South Sudan

South Sudan (), officially the Republic of South Sudan, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered on the north by Sudan; on the east by Ethiopia; on the south by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Kenya; and on the ...

in 2011. Between 1989 and 2019, a 30-year-long

military dictatorship

A military dictatorship, or a military regime, is a type of dictatorship in which Power (social and political), power is held by one or more military officers. Military dictatorships are led by either a single military dictator, known as a Polit ...

led by

Omar al-Bashir

Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir (born 1 January 1944) is a Sudanese former military officer and politician who served as Head of state of Sudan, Sudan's head of state under various titles from 1989 until 2019, when he was deposed in 2019 Sudanese c ...

ruled Sudan and committed widespread

human rights abuses

Human rights are universally recognized moral principles or norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both national and international laws. These rights are considered inherent and inalienable, meaning t ...

, including torture, persecution of minorities,

alleged sponsorship of global terrorism, and

ethnic genocide in

Darfur

Darfur ( ; ) is a region of western Sudan. ''Dār'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f – the region was named Dardaju () while ruled by the Daju, who migrated from Meroë , and it was renamed Dartunjur () when the Tunjur ruled the area. ...

from 2003–2020. Overall, the regime killed an estimated 300,000 to 400,000 people.

Protests erupted in 2018, demanding Bashir's resignation, which resulted in a

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

on 11 April 2019 and Bashir's imprisonment. Sudan is currently embroiled in

a civil war between two rival factions, the

Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), and the paramilitary

Rapid Support Forces

The Rapid Support Forces (RSF; ) is a paramilitary force formerly operated by the government of Sudan. The RSF grew out of, and is primarily composed of, the Janjaweed militias which previously fought on behalf of the Sudanese government.

RSF ...

(RSF).

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

was Sudan's state religion and

Islamic laws were applied from 1983 until 2020 when the country became a

secular state

is an idea pertaining to secularity, whereby a state is or purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. A secular state claims to treat all its citizens equally regardless of relig ...

.

Sudan is a

least developed country and among the poorest countries in the world, ranking 170th on the

Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistical composite index of life expectancy, Education Index, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income i ...

as of 2024 and 185th by

nominal GDP per capita. Its

economy

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

largely relies on

agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

due to

international sanctions

International sanctions are political and economic decisions that are part of diplomatic efforts by countries, multilateral or regional organizations against states or organizations either to protect national security interests, or to protect i ...

and isolation, as well as a history of internal instability and factional violence. The large majority of Sudan is dry and over 60% of Sudan's population lives in poverty. Sudan is a member of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

,

Arab League

The Arab League (, ' ), officially the League of Arab States (, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world. The Arab League was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945, initially with seven members: Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt, Kingdom of Iraq, ...

,

African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the African Union. The b ...

,

COMESA

The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) is a regional economic community in Africa with twenty-one member states stretching from Tunisia to Eswatini. COMESA was formed in December 1994, replacing a Preferential Trade Area whi ...

,

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

and the

Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC; ; ), formerly the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, is an intergovernmental organisation founded in 1969. It consists of Member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, 57 member s ...

.

Etymology

The country's name ''Sudan'' is a name given historically to the large

Sahel

The Sahel region (; ), or Sahelian acacia savanna, is a Biogeography, biogeographical region in Africa. It is the Ecotone, transition zone between the more humid Sudanian savannas to its south and the drier Sahara to the north. The Sahel has a ...

region of West Africa to the immediate west of modern-day Sudan. Historically, Sudan referred to both the

geographical region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as areas, zones, lands or territories, are portions of the Earth's surface that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and ...

, stretching from

Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

on the

Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

Coast to Northeast Africa and the modern Sudan.

The name derives from the Arabic ' (), or "The Land of the

Blacks". The name is one of various

toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of ''wikt:toponym, toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for ...

s sharing similar

etymologies

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

, in reference to the very dark skin of the indigenous people. Prior to this, Sudan was known as ''Nubia'' and ''Ta Nehesi'' or ''Ta Seti'' by

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

ians named for the Nubian and

Medjay

Medjay (also ''Medjai'', ''Mazoi'', ''Madjai'', ''Mejay'', Egyptian ''mḏꜣ.j'', a Arabic nouns and adjectives#Nisba, nisba of ''mḏꜣ'') was a demonym used in various ways throughout History of ancient Egypt, ancient Egyptian history to refe ...

archers or bowmen.

Since 2011, Sudan is also sometimes referred to as North Sudan to distinguish it from

South Sudan

South Sudan (), officially the Republic of South Sudan, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered on the north by Sudan; on the east by Ethiopia; on the south by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Kenya; and on the ...

.

History

Prehistoric Sudan (before c. 8000 BC)

Affad 23

Affad 23 is an

archaeological site

An archaeological site is a place (or group of physical sites) in which evidence of past activity is preserved (either prehistoric or recorded history, historic or contemporary), and which has been, or may be, investigated using the discipline ...

located in the

Affad region of southern Dongola Reach in northern Sudan,

which hosts "the well-preserved remains of prehistoric camps (relics of the oldest

open-air hut in the world) and diverse

hunting

Hunting is the Human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, and killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to obtain the animal's body for meat and useful animal products (fur/hide (sk ...

and

gathering loci some 50,000 years old".

By the eighth millennium BC, people of a

Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

culture had settled into a sedentary way of life there in fortified

mudbrick

Mudbrick or mud-brick, also known as unfired brick, is an air-dried brick, made of a mixture of mud (containing loam, clay, sand and water) mixed with a binding material such as rice husks or straw. Mudbricks are known from 9000 BCE.

From ...

villages, where they supplemented hunting and fishing on the Nile with grain gathering and cattle herding.

Neolithic peoples created cemeteries such as

R12. During the fifth millennium BC, migrations from the drying Sahara brought neolithic people into the Nile Valley along with agriculture.

The population that resulted from this cultural and genetic mixing developed a social hierarchy over the next centuries which became the

Kingdom of Kerma

The Kingdom of Kerma or the Kerma culture was an early civilization centered in Kerma, Sudan. It flourished from around 2500 BC to 1500 BC in ancient Nubia. The Kerma culture was based in the southern part of Nubia, or " Upper Nubia" (in parts of ...

at 2500 BC. Anthropological and archaeological research indicates that during the predynastic period Nubia and Nagadan Upper Egypt were ethnically and culturally nearly identical, and thus, simultaneously evolved systems of pharaonic kingship by 3300 BC.

Kerma culture (2500–1500 BC)

The Kerma culture was an early civilization centered in

Kerma

Kerma was the capital city of the Kerma culture, which was founded in present-day Sudan before 3500 BC. Kerma is one of the largest archaeological sites in ancient Nubia. It has produced decades of extensive excavations and research, including t ...

, Sudan. It flourished from around 2500 BC to 1500 BC in ancient

Nubia

Nubia (, Nobiin language, Nobiin: , ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue and White Nile, White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract ...

. The Kerma culture was based in the southern part of Nubia, or "

Upper Nubia Upper Nubia (also called Kush) is the southernmost part of Nubia, upstream on the Nile from Lower Nubia. It is so called because the Nile flows north, so it is further upstream and of higher elevation in relation to Lower Nubia.

The extension of '' ...

" (in parts of present-day northern and central Sudan), and later extended its reach northward into Lower Nubia and the border of Egypt. The polity seems to have been one of several

Nile Valley

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the longest river i ...

states during the

Middle Kingdom of Egypt

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt (also known as The Period of Reunification) is the period in the history of ancient Egypt following a period of political division known as the First Intermediate Period of Egypt, First Intermediate Period. The Middl ...

. In the Kingdom of Kerma's latest phase, lasting from about 1700–1500 BC, it absorbed the Sudanese kingdom of

Saï and became a sizable, populous empire rivaling Egypt.

Egyptian Nubia (1504–1070 BC)

Mentuhotep II

Mentuhotep II (, meaning "Mentu is satisfied"), also known under his Prenomen (Ancient Egypt), prenomen Nebhepetre (, meaning "The Lord of the rudder is Ra"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the sixth ruler of the Eleventh Dynasty of Egypt, Elev ...

, the 21st century BC founder of the

Middle Kingdom, is recorded to have undertaken campaigns against Kush in the 29th and 31st years of his reign. This is the earliest Egyptian reference to ''Kush''; the

Nubia

Nubia (, Nobiin language, Nobiin: , ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue and White Nile, White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract ...

n region had gone by other names in the Old Kingdom. Under

Thutmose I

Thutmose I (sometimes read as Thutmosis or Tuthmosis I, Thothmes in older history works in Latinized Greek; meaning "Thoth is born") was the third pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, 18th Dynasty of History of Ancient Egypt, Egypt. He re ...

, Egypt made several campaigns south.

The Egyptians ruled Kush in the New kingdom beginning when the Egyptian King Thutmose I occupied Kush and destroyed its capital, Kerma.

This eventually resulted in their annexation of Nubia . Around 1500 BC, Nubia was absorbed into the

New Kingdom of Egypt

The New Kingdom, also called the Egyptian Empire, refers to ancient Egypt between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC. This period of History of ancient Egypt, ancient Egyptian history covers the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth, ...

, but rebellions continued for centuries. After the conquest, Kerma culture was increasingly Egyptianized, yet rebellions continued for 220 years until . Nubia nevertheless became a key province of the New Kingdom, economically, politically, and spiritually. Indeed, major pharaonic ceremonies were held at Jebel Barkal near Napata. As an Egyptian colony from the 16th century BC, Nubia ("Kush") was governed by an Egyptian

Viceroy of Kush.

Resistance to the early eighteenth Dynasty Egyptian rule by neighboring Kush is evidenced in the writings of

Ahmose, son of Ebana, an Egyptian warrior who served under Nebpehtrya Ahmose (1539–1514 BC), Djeserkara Amenhotep I (1514–1493 BC), and Aakheperkara Thutmose I (1493–1481 BC). At the end of the

Second Intermediate Period

The Second Intermediate Period dates from 1700 to 1550 BC. It marks a period when ancient Egypt was divided into smaller dynasties for a second time, between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the New Kingdom. The concept of a Secon ...

(mid-sixteenth century BC), Egypt faced the twin existential threats—the

Hyksos

The Hyksos (; Egyptian language, Egyptian ''wikt:ḥqꜣ, ḥqꜣ(w)-wikt:ḫꜣst, ḫꜣswt'', Egyptological pronunciation: ''heqau khasut'', "ruler(s) of foreign lands"), in modern Egyptology, are the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt ( ...

in the North and the Kushites in the South. Taken from the autobiographical inscriptions on the walls of his tomb-chapel, the Egyptians undertook campaigns to defeat Kush and conquer Nubia under the rule of

Amenhotep I (1514–1493 BC). In Ahmose's writings, the Kushites are described as

archers

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a Bow and arrow, bow to shooting, shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting ...

, "Now after his Majesty had slain the Bedoin of Asia, he sailed upstream to

Upper Nubia Upper Nubia (also called Kush) is the southernmost part of Nubia, upstream on the Nile from Lower Nubia. It is so called because the Nile flows north, so it is further upstream and of higher elevation in relation to Lower Nubia.

The extension of '' ...

to destroy the Nubian bowmen." The tomb writings contain two other references to the Nubian bowmen of Kush. By 1200 BC, Egyptian involvement in the

Dongola Reach

The Dongola Reach is a reach of approximately 160 km in length stretching from the Fourth downriver to the Third Cataracts of the Nile in Upper Nubia, Sudan. Named after the Sudanese town of Dongola which dominates this part of the river, the r ...

was nonexistent.

Egypt's international prestige had declined considerably towards the end of the

Third Intermediate Period

The Third Intermediate Period of ancient Egypt began with the death of Pharaoh Ramesses XI in 1077 BC, which ended the New Kingdom, and was eventually followed by the Late Period. Various points are offered as the beginning for the latt ...

. Its historical allies, the inhabitants of

Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

, had fallen to the

Middle Assyrian Empire

The Middle Assyrian Empire was the third stage of Assyrian history, covering the history of Assyria from the accession of Ashur-uballit I 1363 BC and the rise of Assyria as a territorial kingdom to the death of Ashur-dan II in 912 BC. ...

(1365–1020 BC), and then the resurgent

Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

(935–605 BC). The

Assyrians

Assyrians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to Mesopotamia, a geographical region in West Asia. Modern Assyrians share descent directly from the ancient Assyrians, one of the key civilizations of Mesopotamia. While they are distinct from ot ...

, from the tenth century BC onwards, had once more expanded from northern

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, and conquered a vast empire, including the whole of the

Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

, and much of

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, the eastern

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

, the

Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

and

early Iron Age Iran.

According to Josephus Flavius, the biblical Moses led the Egyptian army in a siege of the Kushite city of Meroe. To end the siege Princess Tharbis was given to Moses as a (diplomatic) bride, and thus the Egyptian army retreated back to Egypt.

Kingdom of Kush (c. 1070 BC–350 AD)

The

Kingdom of Kush

The Kingdom of Kush (; Egyptian language, Egyptian: 𓎡𓄿𓈙𓈉 ''kꜣš'', Akkadian language, Assyrian: ''Kûsi'', in LXX Χους or Αἰθιοπία; ''Ecōš''; ''Kūš''), also known as the Kushite Empire, or simply Kush, was an an ...

was an ancient

Nubia

Nubia (, Nobiin language, Nobiin: , ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue and White Nile, White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract ...

n state centred on the confluences of the

Blue Nile

The Blue Nile is a river originating at Lake Tana in Ethiopia. It travels for approximately through Ethiopia and Sudan. Along with the White Nile, it is one of the two major Tributary, tributaries of the Nile and supplies about 85.6% of the wa ...

and

White Nile

The White Nile ( ') is a river in Africa, the minor of the two main tributaries of the Nile, the larger being the Blue Nile. The name "White" comes from the clay sediment carried in the water that changes the water to a pale color.

In the stri ...

, and the

Atbarah River and the

Nile River

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the longest river i ...

. It was established after the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

collapse and the disintegration of the

New Kingdom of Egypt

The New Kingdom, also called the Egyptian Empire, refers to ancient Egypt between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC. This period of History of ancient Egypt, ancient Egyptian history covers the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth, ...

; it was centred at Napata in its early phase.

After King

Kashta

Kashta was an 8th century BCE king of the Kingdom of Kush, Kushite Dynasty in ancient Nubia and the successor of Alara of Kush, Alara. His nomen ''k3š-t3'' (transcribed as Kashta, possibly pronounced /kuʔʃi-taʔ/) "of the land of Kush" is ofte ...

("the Kushite") invaded Egypt in the eighth century BC, the Kushite kings ruled as pharaohs of the

Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt

The Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XXV, alternatively 25th Dynasty or Dynasty 25), also known as the Nubian Dynasty, the Kushite Empire, the Black Pharaohs, or the Napatans, after their capital Napata, was the last dynasty of t ...

for nearly a century before being defeated and driven out by the

Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

ns.

[ At the height of their glory, the Kushites conquered an empire that stretched from what is now known as ]South Kordofan

South Kordofan ( ') is one of the 18 States of Sudan, wilayat or states of Sudan. It has an area of 158,355 km2 and an estimated population of approximately 2,107,623 people (2018 est). Kaduqli is the capital of the state. It is centered on t ...

to the Sinai. Pharaoh Piye

Piye (also interpreted as Pankhy or Piankhi; was an ancient Kushite king and founder of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, who ruled Egypt from 744–714 BC. He ruled from the city of Napata, located deep in Nubia, modern-day Sudan.

Name

Piye ...

attempted to expand the empire into the Near East but was thwarted by the Assyrian king Sargon II

Sargon II (, meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is generally believed to have be ...

.

Between 800 BCE and 100 AD the Nubian pyramids were built, among them can be named El-Kurru

El-Kurru was the first of the three royal cemeteries used by the Kingdom of Kush, Kushite royals of Napata, also referred to as Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, Egypt's 25th Dynasty, and is home to some of the royal Nubian pyramids, Nubian Pyramid ...

, Kashta

Kashta was an 8th century BCE king of the Kingdom of Kush, Kushite Dynasty in ancient Nubia and the successor of Alara of Kush, Alara. His nomen ''k3š-t3'' (transcribed as Kashta, possibly pronounced /kuʔʃi-taʔ/) "of the land of Kush" is ofte ...

, Piye

Piye (also interpreted as Pankhy or Piankhi; was an ancient Kushite king and founder of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, who ruled Egypt from 744–714 BC. He ruled from the city of Napata, located deep in Nubia, modern-day Sudan.

Name

Piye ...

, Tantamani

Tantamani ( Meroitic: 𐦛𐦴𐦛𐦲𐦡𐦲, , Neo-Assyrian: , ), also known as Tanutamun or Tanwetamani (d. 653 BC) was ruler of the Kingdom of Kush located in Northern Sudan, and the last pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt. ...

, Shabaka

Neferkare Shabaka, or Shabako ( Meroitic: 𐦰𐦲𐦡𐦐𐦲 (sha-ba-ka), Egyptian: 𓆷𓃞𓂓 ''šꜣ bꜣ kꜣ'', Assyrian: ''Ša-ba-ku-u'', Šabakû ) was the third Kushite pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, who reigned fr ...

, Pyramids of Gebel Barkal, Pyramids of Meroe (Begarawiyah), the Sedeinga pyramids, and Pyramids of Nuri.Taharqa

Taharqa, also spelled Taharka or Taharqo, Akkadian: ''Tar-qu-ú'', , Manetho's ''Tarakos'', Strabo's ''Tearco''), was a pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt and qore (king) of the Kingdom of Kush (present day Sudan) from 690 to 664 BC. ...

and the Assyrian king Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

was a decisive event in western history, with the Nubians being defeated in their attempts to gain a foothold in the Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

by Assyria. Sennacherib's successor Esarhaddon

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon (, also , meaning " Ashur has given me a brother"; Biblical Hebrew: ''ʾĒsar-Ḥaddōn'') was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 681 to 669 BC. The third king of the S ...

went further and invaded Egypt itself to secure his control of the Levant. This succeeded, as he managed to expel Taharqa from Lower Egypt. Taharqa fled back to Upper Egypt and Nubia, where he died two years later. Lower Egypt came under Assyrian vassalage but proved unruly, unsuccessfully rebelling against the Assyrians. Then, the king Tantamani

Tantamani ( Meroitic: 𐦛𐦴𐦛𐦲𐦡𐦲, , Neo-Assyrian: , ), also known as Tanutamun or Tanwetamani (d. 653 BC) was ruler of the Kingdom of Kush located in Northern Sudan, and the last pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt. ...

, a successor of Taharqa, made a final determined attempt to regain Lower Egypt from the newly reinstated Assyrian vassal Necho I

Menkheperre Necho I (Egyptian language, Egyptian: Nekau, Ancient Greek, Greek: Νεχώς Α' or Νεχώ Α', Akkadian language, Akkadian: Nikuu. or Nikû.) (? – near Memphis, Egypt, Memphis) was a ruler of the ancient Egyptian city of Sais, E ...

. He managed to retake Memphis killing Necho in the process and besieged cities in the Nile Delta. Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (, meaning " Ashur is the creator of the heir")—or Osnappar ()—was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BC to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Ashurbanipal inherited the th ...

, who had succeeded Esarhaddon, sent a large army in Egypt to regain control. He routed Tantamani near Memphis and, pursuing him, sacked Thebes. Although the Assyrians immediately departed Upper Egypt after these events, weakened, Thebes peacefully submitted itself to Necho's son Psamtik I

Wahibre Psamtik I (Ancient Egyptian: ) was the first pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt, the Saite period, ruling from the city of Sais in the Nile delta between 664 and 610 BC. He was installed by Ashurbanipal of the Neo-Assyrian E ...

less than a decade later. This ended all hopes of a revival of the Nubian Empire, which rather continued in the form of a smaller kingdom centred on Napata

Napata

(2020).

. The city was raided by the Egyptian 590 BC, and sometime soon after to the late-3rd century BC, the Kushite resettled in Meroë

Meroë (; also spelled ''Meroe''; Meroitic: ; and ; ) was an ancient city on the east bank of the Nile about 6 km north-east of the Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, approximately 200 km north-east of Khartoum. Near the site is ...

.

Medieval Christian Nubian kingdoms (c. 350–1500)

On the turn of the fifth century the Blemmyes established a short-lived state in Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia, probably centred around Talmis ( Kalabsha), but before 450 they were already driven out of the Nile Valley by the Nobatians. The latter eventually founded a kingdom on their own, Nobatia.

By the sixth century there were in total three Nubian kingdoms: Nobatia in the north, which had its capital at Pachoras ( Faras); the central kingdom, Makuria centred at Tungul (

On the turn of the fifth century the Blemmyes established a short-lived state in Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia, probably centred around Talmis ( Kalabsha), but before 450 they were already driven out of the Nile Valley by the Nobatians. The latter eventually founded a kingdom on their own, Nobatia.

By the sixth century there were in total three Nubian kingdoms: Nobatia in the north, which had its capital at Pachoras ( Faras); the central kingdom, Makuria centred at Tungul (Old Dongola

Old Dongola ( Old Nubian: ⲧⲩⲛⲅⲩⲗ, ''Tungul''; , ''Dunqulā al-ʿAjūz'') is a deserted Nubian town in what is now Northern State, Sudan, located on the east bank of the Nile opposite the Wadi Howar. An important city in medieval Nub ...

), about south of modern Dongola

Dongola (), also known as Urdu or New Dongola, is the capital of Northern State in Sudan, on the banks of the Nile. It should not be confused with Old Dongola, a now deserted medieval city located 80 km upstream on the opposite bank.

Et ...

; and Alodia, in the heartland of the old Kushitic kingdom, which had its capital at Soba

Soba ( or , "buckwheat") are Japanese noodles made primarily from buckwheat flour, with a small amount of wheat flour mixed in.

It has an ashen brown color, and a slightly grainy texture. The noodles are served either chilled with a dipping sau ...

(now a suburb of modern-day Khartoum). Still in the sixth century they converted to Christianity. In the seventh century, probably at some point between 628 and 642, Nobatia was incorporated into Makuria.

Between 639 and 641 the Muslim Arabs of the Rashidun Caliphate

The Rashidun Caliphate () is a title given for the reigns of first caliphs (lit. "successors") — Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali collectively — believed to Political aspects of Islam, represent the perfect Islam and governance who led the ...

conquered

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or legal prohibitions against conquest ...

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

Egypt. In 641 or 642 and again in 652 they invaded Nubia but were repelled, making the Nubians one of the few who managed to defeat the Arabs during the Islamic expansion. Afterward the Makurian king and the Arabs agreed on a unique non-aggression pact that also included an annual exchange of gifts, thus acknowledging Makuria's independence. While the Arabs failed to conquer Nubia they began to settle east of the Nile, where they eventually founded several port towns and intermarried with the local Beja.

From the mid-eighth to mid-eleventh century the political power and cultural development of Christian Nubia peaked. In 747 Makuria invaded Egypt, which at this time belonged to the declining Umayyads, and it did so again in the early 960s, when it pushed as far north as

From the mid-eighth to mid-eleventh century the political power and cultural development of Christian Nubia peaked. In 747 Makuria invaded Egypt, which at this time belonged to the declining Umayyads, and it did so again in the early 960s, when it pushed as far north as Akhmim

Akhmim (, ; Akhmimic , ; Sahidic/Bohairic ) is a city in the Sohag Governorate of Upper Egypt. Referred to by the ancient Greeks as Khemmis or Chemmis () and Panopolis (), it is located on the east bank of the Nile, to the northeast of Sohag.

...

. Makuria maintained close dynastic ties with Alodia, perhaps resulting in the temporary unification of the two kingdoms into one state. The culture of the medieval Nubians has been described as "''Afro-Byzantine''", but was also increasingly influenced by Arab culture. The state organisation was extremely centralised, being based on the Byzantine bureaucracy of the sixth and seventh centuries. Arts flourished in the form of pottery paintings and especially wall paintings. The Nubians developed an alphabet for their language, Old Nobiin, basing it on the Coptic alphabet

The Coptic alphabet is the script used for writing the Coptic language, the most recent development of Egyptian. The repertoire of glyphs is based on the uncial Greek alphabet, augmented by letters borrowed from the Egyptian Demotic. It was ...

, while also using Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, Coptic and Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

. Women enjoyed high social status: they had access to education, could own, buy and sell land and often used their wealth to endow churches and church paintings. Even the royal succession was matrilineal

Matrilineality, at times called matriliny, is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which people identify with their matriline, their mother's lineage, and which can involve the inheritan ...

, with the son of the king's sister being the rightful heir.

From the late 11th/12th century, Makuria's capital Dongola was in decline, and Alodia's capital declined in the 12th century as well. In the 14th and 15th centuries Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu ( ; , singular ) are pastorally nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia (Iraq). The Bedouin originated in the Sy ...

tribes overran most of Sudan, migrating to the Butana

The Butana (Arabic: البطانة, ''Buṭāna''), historically called the Island of Meroë, is the region between the Atbarah River, Atbara and the Nile in the Sudan. South of Khartoum it is bordered by the Blue Nile and in the east by Lake T ...

, the Gezira, Kordofan

Kordofan ( ') is a former province of central Sudan. In 1994 it was divided into three new federal states: North Kordofan, South Kordofan and West Kordofan. In August 2005, West Kordofan State was abolished and its territory divided between N ...

and Darfur

Darfur ( ; ) is a region of western Sudan. ''Dār'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f – the region was named Dardaju () while ruled by the Daju, who migrated from Meroë , and it was renamed Dartunjur () when the Tunjur ruled the area. ...

. In 1365 a civil war forced the Makurian court to flee to Gebel Adda in Lower Nubia

Lower Nubia (also called Wawat) is the northernmost part of Nubia, roughly contiguous with the modern Lake Nasser, which submerged the historical region in the 1960s with the construction of the Aswan High Dam. Many ancient Lower Nubian monuments, ...

, while Dongola was destroyed and left to the Arabs. Afterwards Makuria continued to exist only as a petty kingdom. After the prosperous reign of king Joel ( 1463–1484) Makuria collapsed. Coastal areas from southern Sudan up to the port city of Suakin was succeeded by the Adal Sultanate

The Adal Sultanate, also known as the Adal Empire or Barr Saʿad dīn (alt. spelling ''Adel Sultanate'', ''Adal Sultanate'') (), was a medieval Sunni Muslim empire which was located in the Horn of Africa. It was founded by Sabr ad-Din III on th ...

in the fifteenth century. To the south, the kingdom of Alodia fell to either the Arabs, commanded by tribal leader Abdallah Jamma, or the Funj, an African people originating from the south. Datings range from the 9th century after the Hijra ( 1396–1494), the late 15th century, 1504 to 1509. An alodian rump state might have survived in the form of the kingdom of Fazughli, lasting until 1685.

Islamic kingdoms of Sennar and Darfur (c. 1500–1821)

In 1504 the Funj are recorded to have founded the Kingdom of Sennar

The Funj Sultanate, also known as Funjistan, Sultanate of Sennar (after its capital Sennar) or Blue Sultanate (due to the traditional Sudanese convention of referring to black people as blue) (), was a monarchy in what is now Sudan, northwester ...

, in which Abdallah Jamma's realm was incorporated. By 1523, when Jewish traveller David Reubeni visited Sudan, the Funj state already extended as far north as Dongola. Meanwhile, Islam began to be preached on the Nile by Sufi

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

holy men who settled there in the 15th and 16th centuries and by David Reubeni's visit king Amara Dunqas, previously a Pagan or nominal Christian, was recorded to be Muslim. However, the Funj would retain un-Islamic customs like the divine kingship or the consumption of alcohol until the 18th century. Sudanese folk Islam preserved many rituals stemming from Christian traditions until the recent past.

Soon the Funj came in conflict with the Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

, who had occupied Suakin and eventually pushed south along the Nile, reaching the third Nile cataract area in 1583/1584. A subsequent Ottoman attempt to capture Dongola was repelled by the Funj in 1585. Afterwards, Hannik, located just south of the third cataract, would mark the border between the two states. The aftermath of the Ottoman invasion saw the attempted usurpation of Ajib, a minor king of northern Nubia. While the Funj eventually killed him in 1611/1612 his successors, the Abdallab, were granted to govern everything north of the confluence of Blue and White Niles with considerable autonomy.

During the 17th century the Funj state reached its widest extent, but in the following century it began to decline. A coup in 1718 brought a dynastic change, while another one in 1761–1762 resulted in the Hamaj Regency, where the Hamaj (a people from the Ethiopian borderlands) effectively ruled while the Funj sultans were their mere puppets. Shortly afterwards the sultanate began to fragment; by the early 19th century it was essentially restricted to the Gezira.

The coup of 1718 kicked off a policy of pursuing a more orthodox Islam, which in turn promoted the Arabisation of the state. To legitimise their rule over their Arab subjects the Funj began to propagate an Umayyad descend. North of the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, as far downstream as Al Dabbah, the Nubians adopted the tribal identity of the Arab Jaalin. Until the 19th century Arabic had succeeded in becoming the dominant language of central riverine Sudan and most of Kordofan.

West of the Nile, in

The coup of 1718 kicked off a policy of pursuing a more orthodox Islam, which in turn promoted the Arabisation of the state. To legitimise their rule over their Arab subjects the Funj began to propagate an Umayyad descend. North of the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, as far downstream as Al Dabbah, the Nubians adopted the tribal identity of the Arab Jaalin. Until the 19th century Arabic had succeeded in becoming the dominant language of central riverine Sudan and most of Kordofan.

West of the Nile, in Darfur

Darfur ( ; ) is a region of western Sudan. ''Dār'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f – the region was named Dardaju () while ruled by the Daju, who migrated from Meroë , and it was renamed Dartunjur () when the Tunjur ruled the area. ...

, the Islamic period saw at first the rise of the Tunjur kingdom, which replaced the old Daju kingdom in the 15th century and extended as far west as Wadai. The Tunjur people were probably Arabised Berbers

Berbers, or the Berber peoples, also known as Amazigh or Imazighen, are a diverse grouping of distinct ethnic groups indigenous to North Africa who predate the arrival of Arab migrations to the Maghreb, Arabs in the Maghreb. Their main connec ...

and, their ruling elite at least, Muslims. In the 17th century the Tunjur were driven from power by the Fur

A fur is a soft, thick growth of hair that covers the skin of almost all mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an ...

Keira sultanate. The Keira state, nominally Muslim since the reign of Sulayman Solong (r. 1660–1680), was initially a small kingdom in northern Jebel Marra, but expanded west- and northwards in the early 18th century and eastwards under the rule of Muhammad Tayrab (r. 1751–1786), peaking in the conquest of Kordofan in 1785. The apogee of this empire, now roughly the size of present-day Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

, would last until 1821.

Turkiyah and Mahdist Sudan (1821–1899)

In 1821, the Ottoman ruler of Egypt,

In 1821, the Ottoman ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali (4 March 1769 – 2 August 1849) was the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Albanians, Albanian viceroy and governor who became the ''de facto'' ruler of History of Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty, Egypt from 1805 to 1848, widely consi ...

, invaded and conquered northern Sudan. Although technically the Vali of Egypt under the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, Muhammad Ali styled himself as Khedive

Khedive ( ; ; ) was an honorific title of Classical Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the Khedive of Egypt, viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"Khedive" ''Encyclopaedi ...

of a virtually independent Egypt. Seeking to add Sudan to his domains, he sent his third son Ismail (not to be confused with Ismaʻil Pasha mentioned later) to conquer the country, and subsequently incorporate it into Egypt. With the exception of the Shaiqiya and the Darfur sultanate in Kordofan, he was met without resistance. The Egyptian policy of conquest was expanded and intensified by Ibrahim Pasha's son, Ismaʻil, under whose reign most of the remainder of modern-day Sudan was conquered.

The Egyptian authorities made significant improvements to the Sudanese infrastructure (mainly in the north), especially with regard to irrigation and cotton production. In 1879, the Great Powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

forced the removal of Ismail and established his son Tewfik Pasha

Mohamed Tewfik Pasha ( ''Muḥammad Tawfīq Bāshā''; April 30 or 15 November 1852 – 7 January 1892), also known as Tawfiq of Egypt, was khedive of Khedivate of Egypt, Egypt and the Turco-Egyptian Sudan, Sudan between 1879 and 1892 and the s ...

in his place. Tewfik's corruption and mismanagement resulted in the 'Urabi revolt

The ʻUrabi revolt, also known as the ʻUrabi Revolution (), was a nationalist uprising in the Khedivate of Egypt from 1879 to 1882. It was led by and named for Colonel Ahmed Urabi and sought to depose the khedive, Tewfik Pasha, and end Imperi ...

, which threatened the Khedive's survival. Tewfik appealed for help to the British, who subsequently occupied Egypt in 1882. Sudan was left in the hands of the Khedivial government, and the mismanagement and corruption of its officials.

During the Khedivial period, dissent had spread due to harsh taxes imposed on most activities. Taxation on irrigation wells and farming lands were so high most farmers abandoned their farms and livestock. During the 1870s, European initiatives against the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

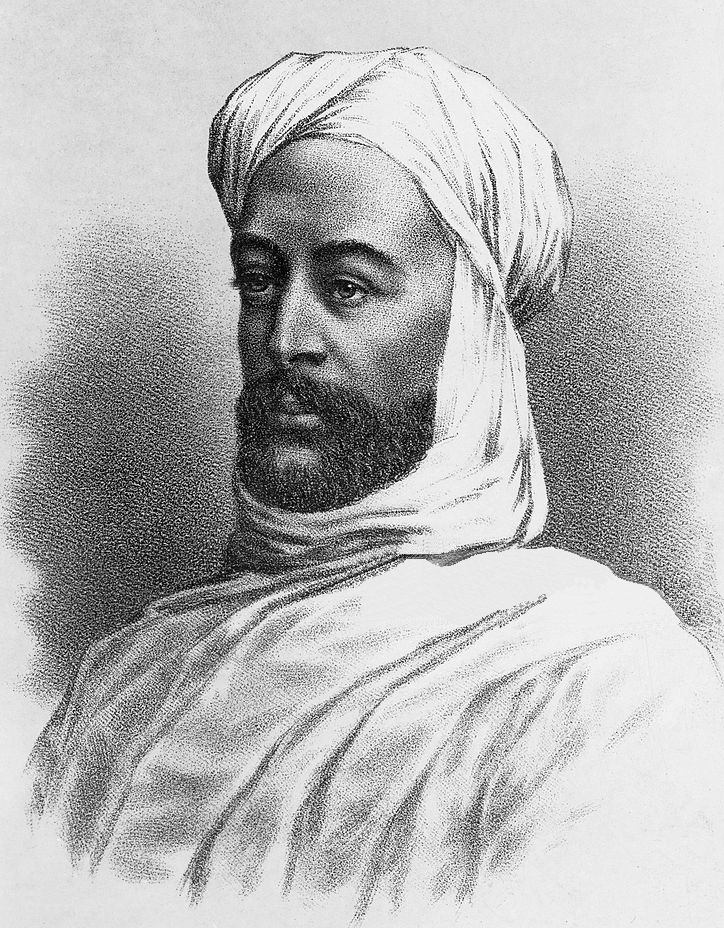

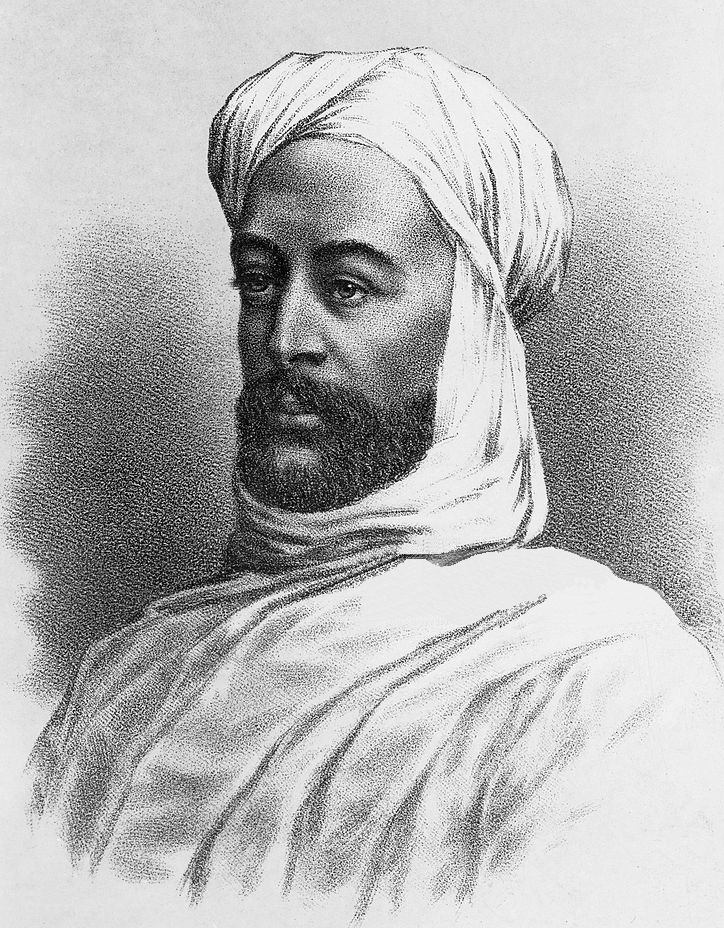

had an adverse impact on the economy of northern Sudan, precipitating the rise of Mahdist forces. Muhammad Ahmad ibn Abd Allah, the ''Mahdi

The Mahdi () is a figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the Eschatology, End of Times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad, and will appear shortly before Jesu ...

'' (Guided One), offered to the ''ansars'' (his followers) and those who surrendered to him a choice between adopting Islam or being killed. The Mahdiyah (Mahdist regime) imposed traditional Sharia Islamic law

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' refers to immutable, intan ...

s. On 12 August 1881, an incident occurred at Aba Island, sparking the outbreak of what became the Mahdist War

The Mahdist War (; 1881–1899) was fought between the Mahdist Sudanese, led by Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdullah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided One"), and the forces of the Khedivate of Egypt, initially, and later th ...

.

From his announcement of the Mahdiyya in June 1881 until the fall of Khartoum in January 1885, Muhammad Ahmad led a successful military campaign against the Turco-Egyptian government of the Sudan, known as the Turkiyah. Muhammad Ahmad died on 22 June 1885, a mere six months after the conquest of Khartoum. After a power struggle amongst his deputies, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad

Abdullah ibn-Mohammed al-Khalifa or Abdullah al-Taashi or Abdallah al-Khalifa, also known as "The Caliph, Khalifa" (; 184625 November 1899) was a Sudanese Ansar (Sudan), Ansar ruler who was one of the principal followers of Muhammad Ahmad. Ahmad c ...

, with the help primarily of the Baggara

The Baggāra ( "heifer herder"), also known as Chadian Arabs, are a nomadic confederation of people of mixed Arab and Arabized indigenous African ancestry, inhabiting a portion of the Sahel mainly between Lake Chad and the Nile river near sou ...

of western Sudan, overcame the opposition of the others and emerged as the unchallenged leader of the Mahdiyah. After consolidating his power, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad assumed the title of ''Khalifa'' (successor) of the Mahdi, instituted an administration, and appointed Ansar (who were usually Baggara

The Baggāra ( "heifer herder"), also known as Chadian Arabs, are a nomadic confederation of people of mixed Arab and Arabized indigenous African ancestry, inhabiting a portion of the Sahel mainly between Lake Chad and the Nile river near sou ...

) as emirs over each of the several provinces.

Regional relations remained tense throughout much of the Mahdiyah period, largely because of the Khalifa's brutal methods to extend his rule throughout the country. In 1887, a 60,000-man Ansar army invaded

Regional relations remained tense throughout much of the Mahdiyah period, largely because of the Khalifa's brutal methods to extend his rule throughout the country. In 1887, a 60,000-man Ansar army invaded Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

, penetrating as far as Gondar

Gondar, also spelled Gonder (Amharic: ጎንደር, ''Gonder'' or ''Gondär''; formerly , ''Gʷandar'' or ''Gʷender''), is a city and woreda in Ethiopia. Located in the North Gondar Zone of the Amhara Region, Gondar is north of Lake Tana on ...

. In March 1889, king Yohannes IV

Yohannes IV ( Tigrinya: ዮሓንስ ፬ይ ''Rabaiy Yōḥānnes''; horse name Abba Bezbiz also known as Kahśsai; born ''Lij'' Kahssai Mercha; 11 July 1837 – 10 March 1889) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1871 to his death in 1889 at the ...

of Ethiopia marched on Metemma; however, after Yohannes fell in battle, the Ethiopian forces withdrew. Abd ar-Rahman an-Nujumi, the Khalifa's general, attempted an invasion of Egypt in 1889, but British-led Egyptian troops defeated the Ansar at Tushkah. The failure of the Egyptian invasion broke the spell of the Ansar's invincibility. The Belgians

Belgians ( ; ; ) are people identified with the Kingdom of Belgium, a federal state in Western Europe. As Belgium is a multinational state, this connection may be residential, legal, historical, or cultural rather than ethnic. The majority ...

prevented the Mahdi's men from conquering Equatoria

Equatoria is the southernmost region of South Sudan, along the upper reaches of the White Nile and the border between South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Juba, the national capital is the largest city in South S ...

, and in 1893, the Italians repelled an Ansar attack at Agordat (in Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

) and forced the Ansar to withdraw from Ethiopia.

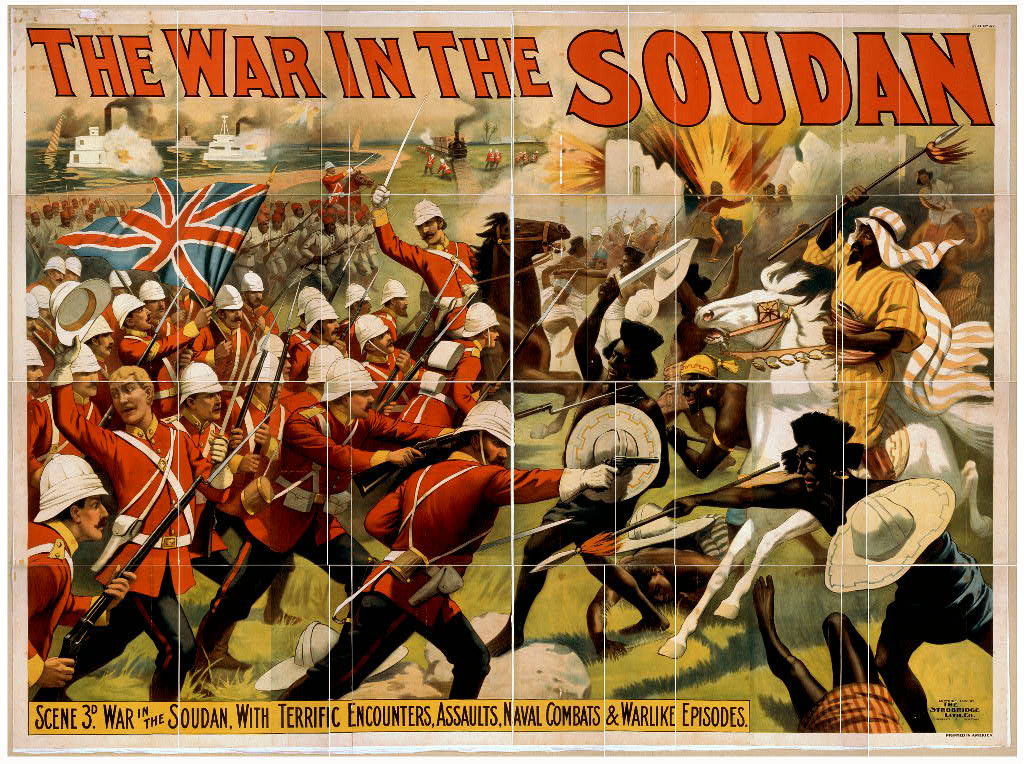

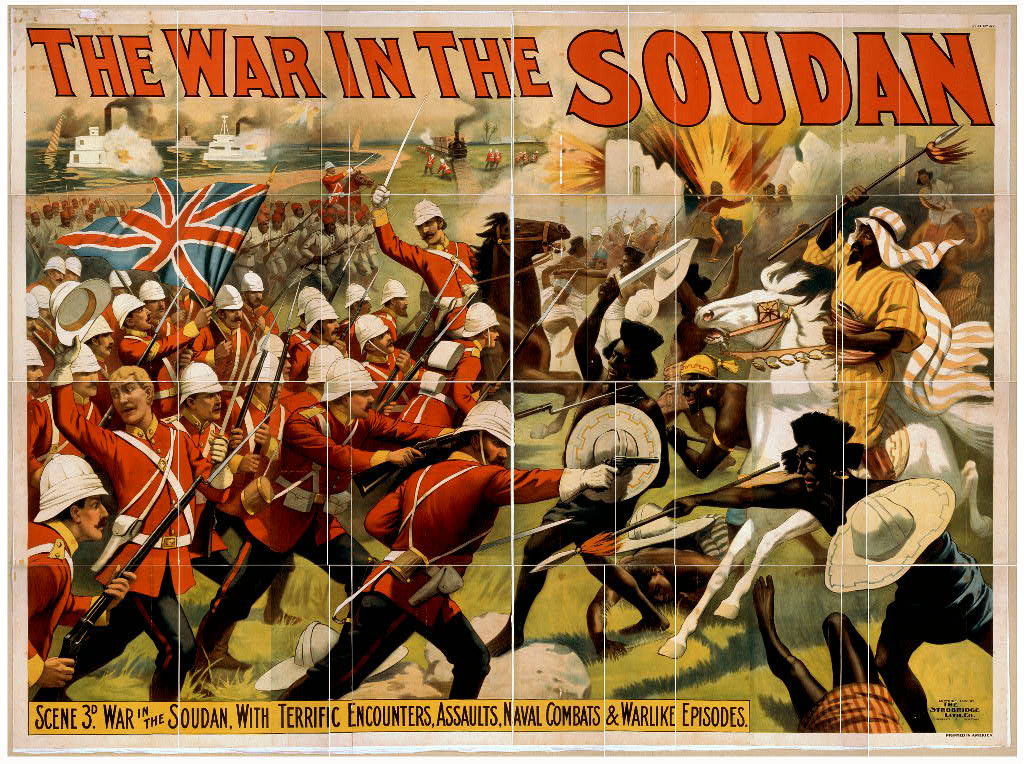

In the 1890s, the British sought to re-establish their control over Sudan, once more officially in the name of the Egyptian Khedive, but in actuality treating the country as a British colony. By the early 1890s, British, French, and Belgian claims had converged at the Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

headwaters. Britain feared that the other powers would take advantage of Sudan's instability to acquire territory previously annexed to Egypt. Apart from these political considerations, Britain wanted to establish control over the Nile to safeguard a planned irrigation dam at Aswan

Aswan (, also ; ) is a city in Southern Egypt, and is the capital of the Aswan Governorate.

Aswan is a busy market and tourist centre located just north of the Aswan Dam on the east bank of the Nile at the first cataract. The modern city ha ...

. Herbert Kitchener led military campaigns against the Mahdist Sudan from 1896 to 1898. Kitchener's campaigns culminated in a decisive victory in the Battle of Omdurman

The Battle of Omdurman, also known as the Battle of Karary, was fought during the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan between a British–Egyptian expeditionary force commanded by British Commander-in-Chief (sirdar) major general Horatio Herbert ...

on 2 September 1898. A year later, the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat on 25 November 1899 resulted in the death of Abdallahi ibn Muhammad

Abdullah ibn-Mohammed al-Khalifa or Abdullah al-Taashi or Abdallah al-Khalifa, also known as "The Caliph, Khalifa" (; 184625 November 1899) was a Sudanese Ansar (Sudan), Ansar ruler who was one of the principal followers of Muhammad Ahmad. Ahmad c ...

, subsequently bringing to an end the Mahdist War.

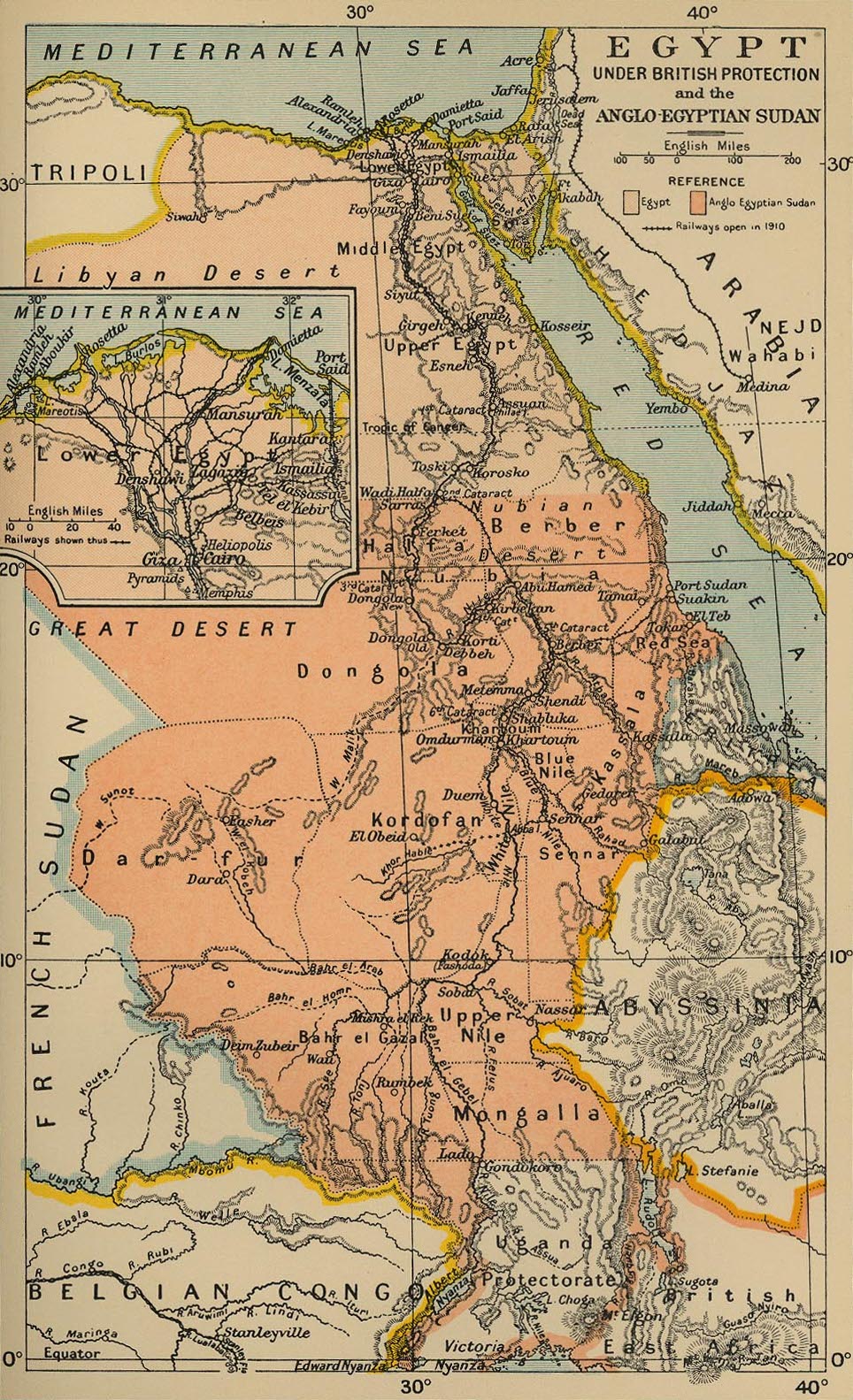

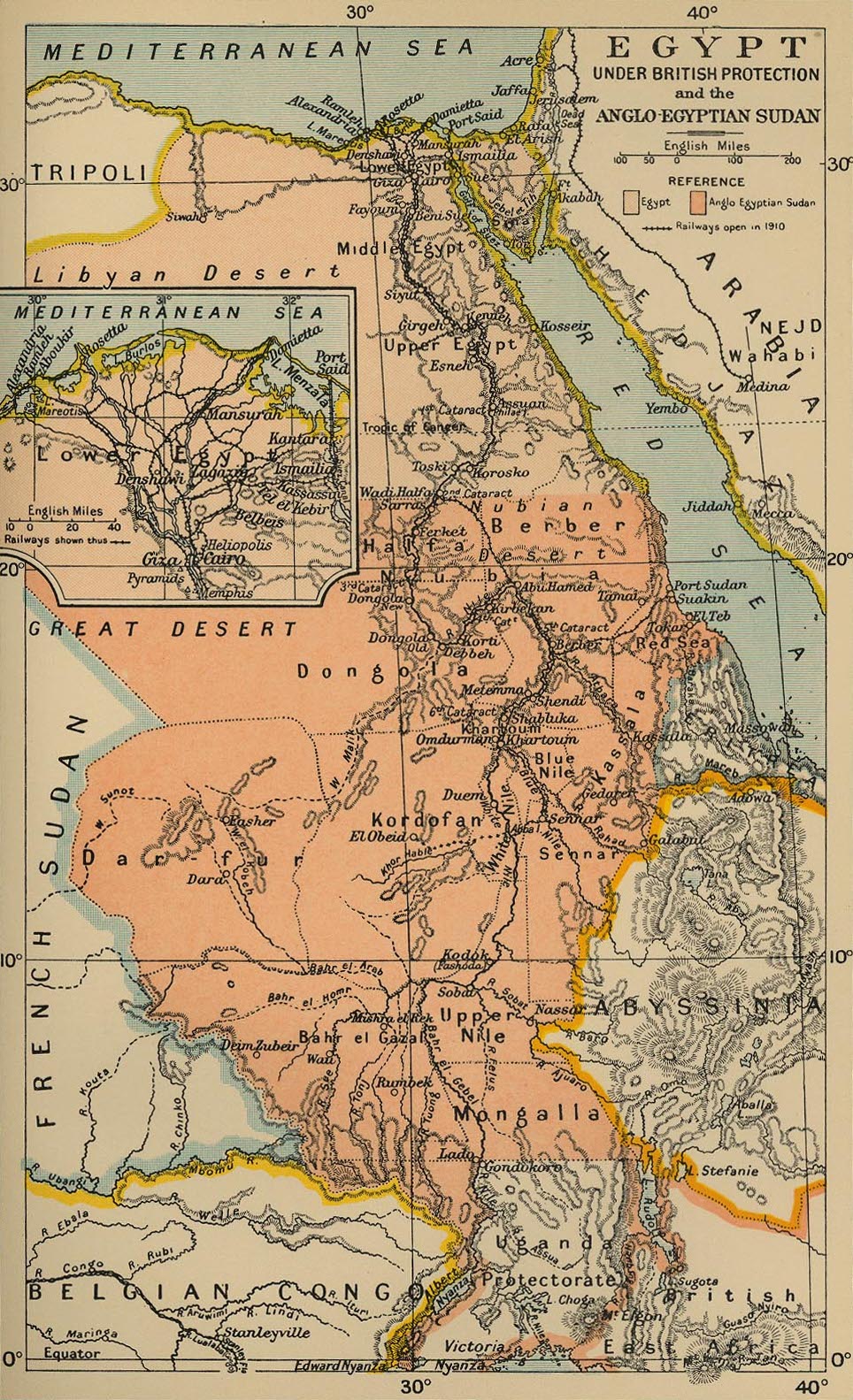

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1899–1956)

In 1899, Britain and Egypt reached an agreement under which Sudan was run by a governor-general appointed by Egypt with British consent. In reality, Sudan was effectively administered as a

In 1899, Britain and Egypt reached an agreement under which Sudan was run by a governor-general appointed by Egypt with British consent. In reality, Sudan was effectively administered as a Crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by Kingdom of England, England, and then Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English overseas possessions, English and later British Empire. There was usua ...

. The British were keen to reverse the process, started under Muhammad Ali Pasha, of uniting the Nile Valley

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the longest river i ...

under Egyptian leadership and sought to frustrate all efforts aimed at further uniting the two countries.

Under the Delimitation, Sudan's border with Abyssinia was contested by raiding tribesmen trading slaves, breaching boundaries of the law. In 1905 local chieftain Sultan Yambio, reluctant to the end, gave up the struggle with British forces that had occupied the Kordofan

Kordofan ( ') is a former province of central Sudan. In 1994 it was divided into three new federal states: North Kordofan, South Kordofan and West Kordofan. In August 2005, West Kordofan State was abolished and its territory divided between N ...

region, finally ending the lawlessness. Ordinances published by Britain enacted a system of taxation. This was following the precedent set by the Khalifa. The main taxes were recognized. These taxes were on land, herds, and date-palms. The continued British administration of Sudan fuelled an increasingly strident nationalist backlash, with Egyptian nationalist leaders determined to force Britain to recognise a single independent union of Egypt and Sudan. With a formal end to Ottoman rule in 1914, Sir Reginald Wingate was sent that December to occupy Sudan as the new Military Governor. Hussein Kamel was declared Sultan of Egypt and Sudan, as was his brother and successor, Fuad I. They continued upon their insistence of a single Egyptian-Sudanese state even when the Sultanate of Egypt was retitled as the Kingdom of Egypt and Sudan, but it was Saad Zaghloul who continued to be frustrated in the ambitions until his death in 1927.

From 1924 until independence in 1956, the British had a policy of running Sudan as two essentially separate territories; the north and south. The assassination of a Governor-General of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan in Cairo was the causative factor; it brought demands of the newly elected Wafd government from colonial forces. A permanent establishment of two battalions in Khartoum was renamed the

From 1924 until independence in 1956, the British had a policy of running Sudan as two essentially separate territories; the north and south. The assassination of a Governor-General of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan in Cairo was the causative factor; it brought demands of the newly elected Wafd government from colonial forces. A permanent establishment of two battalions in Khartoum was renamed the Sudan Defence Force

The Sudan Defence Force (SDF) was a British Colonial Auxiliary Forces unit raised in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan in 1925 to assist local police in internal security duties and maintain the condominium's territorial integrity. During World War II, ...

acting as under the government, replacing the former garrison of Egyptian army soldiers, saw action afterward during the Walwal Incident. The Wafdist parliamentary majority had rejected Sarwat Pasha's accommodation plan with Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of ...

in London; yet Cairo still needed the money. The Sudanese Government's revenue had reached a peak in 1928 at £6.6 million, thereafter the Wafdist disruptions, and Italian borders incursions from Somaliland, London decided to reduce expenditure during the Great Depression. Cotton and gum exports were dwarfed by the necessity to import almost everything from Britain leading to a balance of payments deficit at Khartoum.

In July 1936 the Liberal Constitutional leader, Muhammed Mahmoud was persuaded to bring Wafd delegates to London to sign the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, "the beginning of a new stage in Anglo-Egyptian relations", wrote Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achi ...

. The British Army was allowed to return to Sudan to protect the Canal Zone. They were able to find training facilities, and the RAF was free to fly over Egyptian territory. It did not, however, resolve the problem of Sudan: the Sudanese Intelligentsia agitated for a return to metropolitan rule, conspiring with Germany's agents.

Italian fascist leader

Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

made it clear that he could not invade Abyssinia without first conquering Egypt and Sudan; they intended unification of Italian Libya

Libya (; ) was a colony of Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica, Cyrenaica and Italian Tripolitan ...

with Italian East Africa. The British Imperial General Staff prepared for military defence of the region, which was thin on the ground. The British ambassador blocked Italian attempts to secure a Non-Aggression Treaty with Egypt-Sudan. But Mahmoud was a supporter of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem; the region was caught between the Empire's efforts to save the Jews, and moderate Arab calls to halt migration.

The Sudanese Government was directly involved militarily in the East African Campaign. Formed in 1925, the Sudan Defence Force

The Sudan Defence Force (SDF) was a British Colonial Auxiliary Forces unit raised in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan in 1925 to assist local police in internal security duties and maintain the condominium's territorial integrity. During World War II, ...

played an active part in responding to incursions early in World War Two. Italian troops occupied Kassala

Kassala (, ) is the capital of the state of Kassala (state), Kassala in eastern Sudan. In 2003 its population was recorded to be 530,950. Built on the banks of the Mareb River, Gash River, it is a market city and is famous for its fruit gardens. ...

and other border areas from Italian Somaliland

Italian Somaliland (; ; ) was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia, which was ruled in the 19th century by the Sultanate of Hobyo and the Majeerteen Sultanate in the north, and by the Hiraab Imamate and ...

during 1940. In 1942, the SDF also played a part in the invasion of the Italian colony by British and Commonwealth forces. The last British governor-general

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

was Robert George Howe.

The Egyptian revolution of 1952

The Egyptian revolution of 1952, also known as the 1952 coup d'état () and the 23 July Revolution (), was a period of profound political, economic, and societal change in Egypt. On 23 July 1952, the revolution began with the toppling of King ...

finally heralded the beginning of the march towards Sudanese independence. Having abolished the monarchy in 1953, Egypt's new leaders, Mohammed Naguib, whose mother was Sudanese, and later Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

, believed the only way to end British domination in Sudan was for Egypt to officially abandon its claims of sovereignty. In addition, Nasser knew it would be difficult for Egypt to govern an impoverished Sudan after its independence. The British on the other hand continued their political and financial support for the Mahdist successor, Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi

Sir Sayyid Abdul Rahman al-Mahdi, Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire, KBE (; June 1885 – 24 March 1959) was a Sudanese politician and prominent religious leader. He was one of the leading religious and political figures duri ...

, who it was believed would resist Egyptian pressure for Sudanese independence. Abd al-Rahman was capable of this, but his regime was plagued by political ineptitude, which garnered a colossal loss of support in northern and central Sudan. Both Egypt and Britain sensed a great instability fomenting, and thus opted to allow both Sudanese regions, north and south to have a free vote on whether they wished independence or a British withdrawal.

Independence (1956–present)

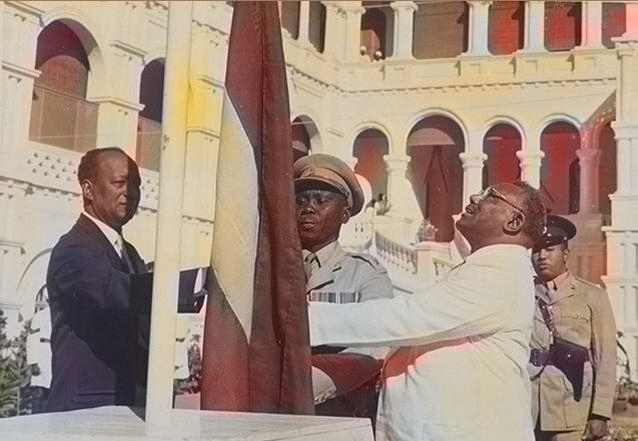

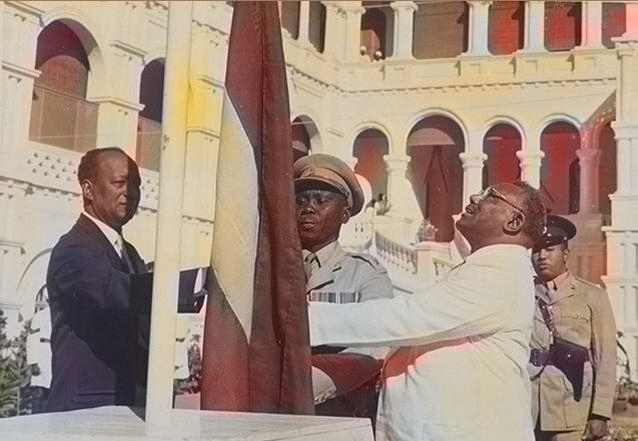

A polling process was carried out resulting in the composition of a democratic parliament and

A polling process was carried out resulting in the composition of a democratic parliament and Ismail al-Azhari

Ismail al-Azhari (; October 20, 1900 – August 26, 1969) was a Sudanese nationalist and political figure. He served as the first Prime Minister of Sudan between 1954 and 1956, and as List of heads of state of Sudan, Head of State of Sudan from ...

was elected first Prime Minister and led the first modern Sudanese government. On 1 January 1956, in a special ceremony held at the People's Palace, the Egyptian and British flags were lowered and the new Sudanese flag, composed of green, blue and yellow stripes, was raised in their place by the prime minister Ismail al-Azhari

Ismail al-Azhari (; October 20, 1900 – August 26, 1969) was a Sudanese nationalist and political figure. He served as the first Prime Minister of Sudan between 1954 and 1956, and as List of heads of state of Sudan, Head of State of Sudan from ...

.

Dissatisfaction culminated in a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

on 25 May 1969. The coup leader, Col. Gaafar Nimeiry

Gaafar Muhammad an-Nimeiry (otherwise spelled in English as Gaafar Nimeiry, Jaafar Nimeiry, or Ja'far Muhammad Numayri; ; 1 January 193030 May 2009) was a Sudanese military officer and politician who served as the fourth president of Sudan, hea ...

, became prime minister, and the new regime abolished parliament and outlawed all political parties. Disputes between Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

and non-Marxist elements within the ruling military coalition resulted in a briefly successful coup in July 1971, led by the Sudanese Communist Party

The Sudanese Communist Party ( abbr. SCP; ) is a communist party in Sudan. Founded in 1946, it was a major force in Sudanese politics in the early post-independence years, and was one of the two most influential communist parties in the Arab ...

. Several days later, anti-communist military elements restored Nimeiry to power.

In 1972, the Addis Ababa Agreement led to a cessation of the north–south civil war and a degree of self-rule. This led to ten years hiatus in the civil war but an end to American investment in the Jonglei Canal

The Jonglei Canal was a canal project started, but never completed, to divert water from the vast Sudd wetlands of South Sudan so as to deliver more water downstream to Sudan and Egypt for use in agriculture. Sir William Garstin proposed the ...

project. This had been considered absolutely essential to irrigate the Upper Nile region and to prevent an environmental catastrophe and wide-scale famine