Roman Fever (disease) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of malaria extendes from its prehistoric origin as a zoonotic disease in the primates of Africa through to the 21st century. A widespread and potentially lethal human infectious disease, at its peak malaria infested every continent except Antarctica. Its prevention and treatment have been targeted in science and medicine for hundreds of years. Since the discovery of the '' Plasmodium'' parasites which cause it, research attention has focused on their biology as well as that of the mosquitoes which transmit the parasites.

References to its unique, periodic fevers are found throughout recorded history, beginning in the first millennium BC in Greece and China.

For thousands of years, traditional herbal remedies have been used to treat malaria. The first effective treatment for malaria came from the bark of the cinchona tree, which contains quinine. After the link to mosquitos and their parasites was identified in the early twentieth century, mosquito control measures such as widespread use of the insecticide DDT, swamp drainage, covering or oiling the surface of open water sources, indoor residual spraying, and use of insecticide treated nets was initiated. Prophylactic quinine was prescribed in malaria endemic areas, and new therapeutic drugs, including chloroquine and artemisinins, were used to resist the scourge. Today, artemisinin is present in every remedy applied in the treatment of malaria. After introducing artemisinin as a cure administered together with other remedies, malaria mortality in Africa decreased by half, though it later partially rebounded.

Malaria researchers have won multiple Nobel Prizes for their achievements, although the disease continues to afflict some 200 million patients each year, killing more than 600,000.

Malaria was the most important health hazard encountered by U.S. troops in the South Pacific during World War II, where about 500,000 men were infected. According to Joseph Patrick Byrne, "Sixty thousand American soldiers died of malaria during the African and South Pacific campaigns."

At the close of the 20th century, malaria remained endemic in more than 100 countries throughout the tropical and subtropical zones, including large areas of Central and South America,

The first evidence of malaria parasites was found in mosquitoes preserved in amber from the Palaeogene period that are approximately 30 million years old. Malaria protozoa are diversified into primate, rodent, bird, and reptile host lineages. The DNA of ''

The first evidence of malaria parasites was found in mosquitoes preserved in amber from the Palaeogene period that are approximately 30 million years old. Malaria protozoa are diversified into primate, rodent, bird, and reptile host lineages. The DNA of ''

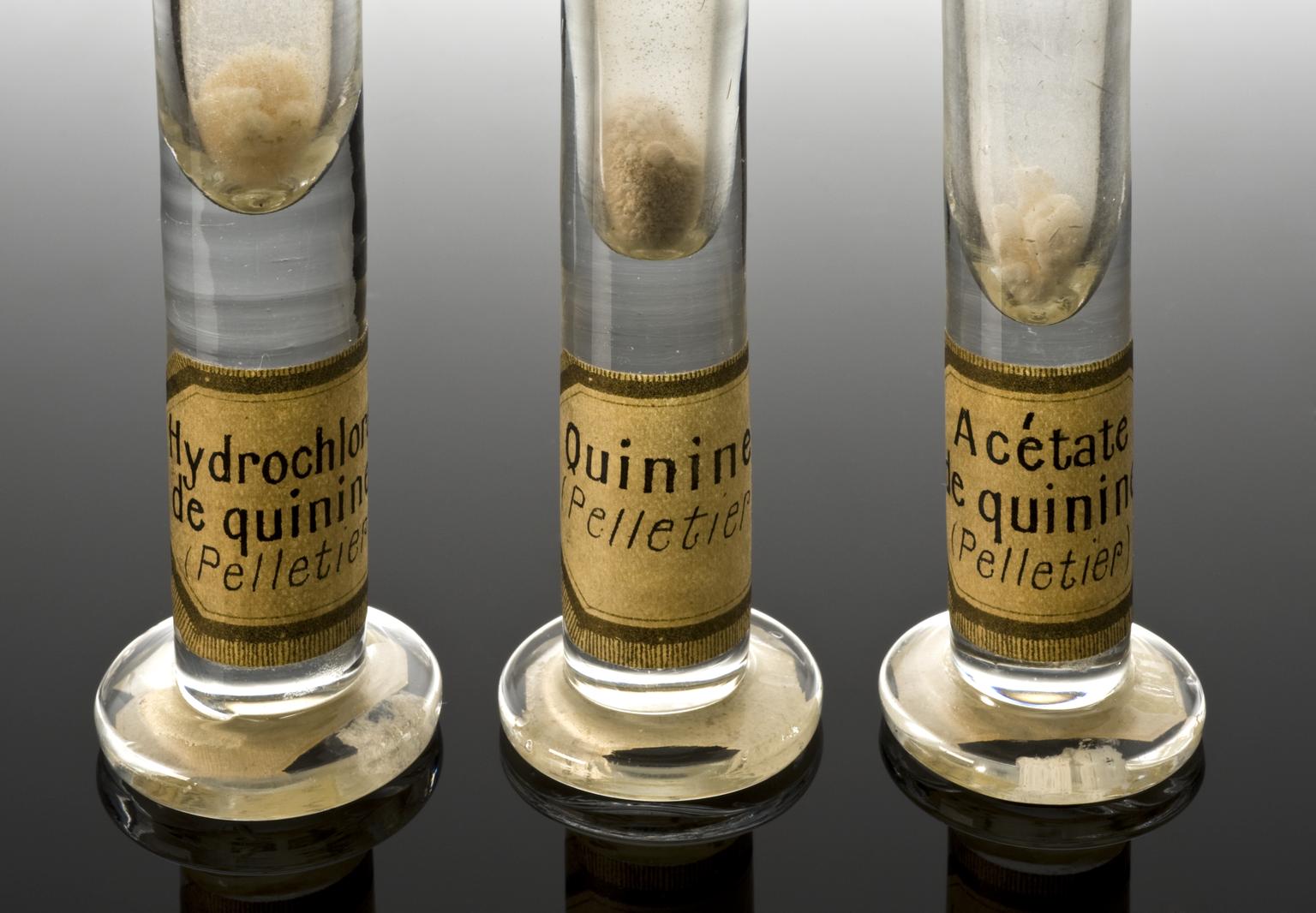

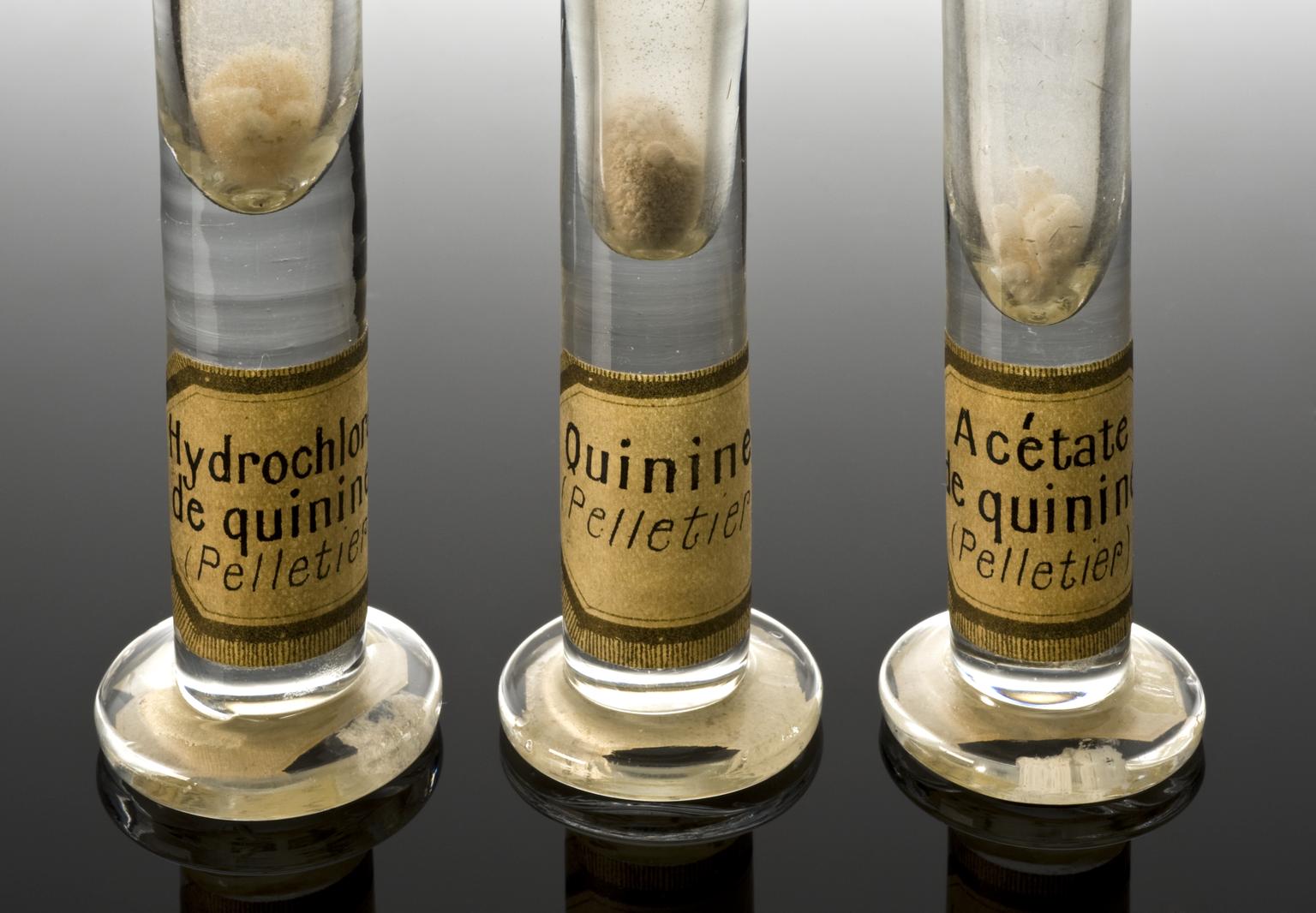

French chemist

French chemist

The establishment of the scientific method from about the mid-19th century on demanded testable hypotheses and verifiable phenomena for causation and transmission. Anecdotal reports, and the discovery in 1881 that mosquitoes were the vector of yellow fever, eventually led to the investigation of mosquitoes in connection with malaria.

An early effort at malaria prevention occurred in 1896 in Massachusetts. An Uxbridge outbreak prompted health officer Dr. Leonard White to write a report to the State Board of Health, which led to a study of mosquito-malaria links and the first efforts for malaria prevention. Massachusetts state pathologist, Theobald Smith, asked that White's son collect mosquito specimens for further analysis, and that citizens add

The establishment of the scientific method from about the mid-19th century on demanded testable hypotheses and verifiable phenomena for causation and transmission. Anecdotal reports, and the discovery in 1881 that mosquitoes were the vector of yellow fever, eventually led to the investigation of mosquitoes in connection with malaria.

An early effort at malaria prevention occurred in 1896 in Massachusetts. An Uxbridge outbreak prompted health officer Dr. Leonard White to write a report to the State Board of Health, which led to a study of mosquito-malaria links and the first efforts for malaria prevention. Massachusetts state pathologist, Theobald Smith, asked that White's son collect mosquito specimens for further analysis, and that citizens add

Hans Andersag, Johann "Hans" Andersag and colleagues synthesized and tested some 12,000 compounds, eventually producing Resochin as a substitute for quinine in the 1930s. It is chemically related to quinine through the possession of a quinoline nucleus and the dialkylaminoalkylamino side chain. Resochin (7-chloro-4- 4- (diethylamino) – 1 – methylbutyl amino quinoline) and a similar compound Sontochin (3-methyl Resochin) were synthesized in 1934. In March 1946, the drug was officially named Chloroquine. Chloroquine is an inhibitor of hemozoin production through

Hans Andersag, Johann "Hans" Andersag and colleagues synthesized and tested some 12,000 compounds, eventually producing Resochin as a substitute for quinine in the 1930s. It is chemically related to quinine through the possession of a quinoline nucleus and the dialkylaminoalkylamino side chain. Resochin (7-chloro-4- 4- (diethylamino) – 1 – methylbutyl amino quinoline) and a similar compound Sontochin (3-methyl Resochin) were synthesized in 1934. In March 1946, the drug was officially named Chloroquine. Chloroquine is an inhibitor of hemozoin production through

Artemisinin is a sesquiterpene lactone containing a peroxide group, which is believed to be essential for its anti-malarial activity. Its derivatives, artesunate and artemether, have been used in clinics since 1987 for the treatment of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive malaria, especially cerebral malaria. These drugs are characterized by fast action, high efficacy, and good tolerance. They kill the asexual forms of ''Plasmodium berghei, P. berghei'' and ''P. cynomolgi'' and have transmission-blocking activity. In 1985, Zhou Yiqing and his team combined artemether and lumefantrine into a single tablet, which was registered as a medicine in China in 1992. Later, it became known as Artemether/lumefantrine, "Coartem". Artemisinin combination treatments (ACTs) are now widely used to treat uncomplicated ''falciparum'' malaria, but access to ACTs is still limited in most malaria-endemic countries, and only a minority of the patients who need artemisinin-based combination treatments receive them.

In 2008, White predicted that improved agricultural practices, selection of high-yielding hybrids, Microorganism, microbial production, and the development of synthetic peroxides would lower prices.

Artemisinin is a sesquiterpene lactone containing a peroxide group, which is believed to be essential for its anti-malarial activity. Its derivatives, artesunate and artemether, have been used in clinics since 1987 for the treatment of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive malaria, especially cerebral malaria. These drugs are characterized by fast action, high efficacy, and good tolerance. They kill the asexual forms of ''Plasmodium berghei, P. berghei'' and ''P. cynomolgi'' and have transmission-blocking activity. In 1985, Zhou Yiqing and his team combined artemether and lumefantrine into a single tablet, which was registered as a medicine in China in 1992. Later, it became known as Artemether/lumefantrine, "Coartem". Artemisinin combination treatments (ACTs) are now widely used to treat uncomplicated ''falciparum'' malaria, but access to ACTs is still limited in most malaria-endemic countries, and only a minority of the patients who need artemisinin-based combination treatments receive them.

In 2008, White predicted that improved agricultural practices, selection of high-yielding hybrids, Microorganism, microbial production, and the development of synthetic peroxides would lower prices.

excerpt and text search

* [http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1948/muller-lecture.pdf Paul H Müller Nobel Lecture 1948: Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane and newer insecticides]

Ronald Ross Nobel Lecture

* [http://www.im.microbios.org/0901/0901069.pdf Grassi versus Ross: Who solved the riddle of malaria?]

Malaria and the Fall of Rome

Centers for Disease Control: History of Malaria

{{DEFAULTSORT:History of Malaria Malaria History of medicine, Malaria

Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

(Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

and the Dominican Republic), Africa, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and Oceania. Resistance of ''Plasmodium'' to anti-malaria drugs, as well as resistance of mosquitos to insecticide

Insecticides are substances used to kill insects. They include ovicides and larvicides used against insect eggs and larvae, respectively. Insecticides are used in agriculture, medicine, industry and by consumers. Insecticides are claimed to b ...

s and the discovery of zoonotic species of the parasite have complicated control measures.

Origin and prehistoric period

The first evidence of malaria parasites was found in mosquitoes preserved in amber from the Palaeogene period that are approximately 30 million years old. Malaria protozoa are diversified into primate, rodent, bird, and reptile host lineages. The DNA of ''

The first evidence of malaria parasites was found in mosquitoes preserved in amber from the Palaeogene period that are approximately 30 million years old. Malaria protozoa are diversified into primate, rodent, bird, and reptile host lineages. The DNA of ''Plasmodium falciparum

''Plasmodium falciparum'' is a Unicellular organism, unicellular protozoan parasite of humans, and the deadliest species of ''Plasmodium'' that causes malaria in humans. The parasite is transmitted through the bite of a female ''Anopheles'' mosqu ...

'' shows the same pattern of diversity as its human hosts, with greater diversity in Africa than in the rest of the world, showing that modern humans had had the disease before they left Africa. Humans may have originally caught ''P. falciparum'' from gorillas. '' P. vivax'', another malarial ''Plasmodium'' species among the six that infect humans, also likely originated in African gorillas and chimpanzees. Another malarial species recently discovered to be transmissible to humans, '' P. knowlesi'', originated in Asian macaque monkeys. While '' P. malariae'' is highly host specific to humans, there is some evidence that low level non-symptomatic infection persists among wild chimpanzees.

About 10,000 years ago, malaria started having a major impact on human survival, coinciding with the start of agriculture in the Neolithic revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, or the (First) Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an incre ...

. Consequences included natural selection for sickle-cell disease

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of blood disorders typically inherited from a person's parents. The most common type is known as sickle cell anaemia. It results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red blo ...

, thalassaemias

Thalassemias are inherited blood disorders characterized by decreased hemoglobin production. Symptoms depend on the type and can vary from none to severe. Often there is mild to severe anemia (low red blood cells or hemoglobin). Anemia can result ...

, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, Southeast Asian ovalocytosis, elliptocytosis and loss of the Gerbich antigen (glycophorin C

Glycophorin C (GYPC; CD236/CD236R; glycoprotein beta; glycoconnectin; PAS-2) plays a functionally important role in maintaining erythrocyte shape and regulating membrane material properties, possibly through its interaction with protein 4.1. Moreo ...

) and the Duffy antigen on the erythrocytes, because such blood disorders confer a selective advantage against malaria infection ( balancing selection). The three major types of inherited genetic resistance (sickle-cell disease, thalassaemias, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency) were present in the Mediterranean world by the time of the Roman Empire, about 2000 years ago.

Molecular methods have confirmed the high prevalence of ''P. falciparum

''Plasmodium falciparum'' is a Unicellular organism, unicellular protozoan parasite of humans, and the deadliest species of ''Plasmodium'' that causes malaria in humans. The parasite is transmitted through the bite of a female ''Anopheles'' mosqu ...

'' malaria in ancient Egypt. The Ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote that the builders of the Egyptian pyramids

A pyramid (from el, πυραμίς ') is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrilate ...

(–1700 BCE) were given large amounts of garlic

Garlic (''Allium sativum'') is a species of bulbous flowering plant in the genus ''Allium''. Its close relatives include the onion, shallot, leek, chive, Allium fistulosum, Welsh onion and Allium chinense, Chinese onion. It is native to South A ...

, probably to protect them against malaria. The Pharaoh Sneferu, the founder of the Fourth dynasty of Egypt, who reigned from around 2613–2589 BCE, used bed-nets as protection against mosquitoes. Cleopatra VII

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler.She was also a ...

, the last Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, similarly slept under a mosquito net. However, whether the mosquito nets were used for the purpose of malaria prevention, or for more mundane purpose of avoiding the discomfort of mosquito bites, is unknown. The presence of malaria in Egypt from circa 800 BCE onwards has been confirmed using DNA-based methods.

Classical period

Malaria became widely recognized in ancient Greece by the 4th century BC and is implicated in the decline of many city-state populations. The term ''μίασμα'' (Greek for miasma): "stain, pollution was coined by Hippocrates of Kos who used it to describe dangerous fumes from the ground that are transported by winds and can cause serious illnesses. Hippocrates (460–370 BC), the "father of medicine", related the presence of intermittentfevers

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a temperature above the normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature set point. There is not a single agreed-upon upper limit for normal temperature with sources using val ...

with climatic and environmental

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale f ...

conditions and classified the fever according to periodicity: Gk.:''tritaios pyretos'' / L.:''febris tertiana'' (fever every third day), and Gk.:''tetartaios pyretos'' / L.:''febris quartana'' (fever every fourth day).

The Chinese '' Huangdi Neijing'' (The Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor) dating from ~300 BC – 200 AD apparently refers to repeated paroxysmal fevers associated with enlarged spleens

The spleen is an organ (biology), organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

and a tendency to epidemic occurrence.

Around 168 BC, the herbal remedy ''Qing-hao'' ( 青蒿) (''Artemisia annua

''Artemisia annua'', also known as sweet wormwood, sweet annie, sweet sagewort, annual mugwort or annual wormwood (), is a common type of wormwood native to temperate Asia, but naturalized in many countries including scattered parts of North Am ...

'') came into use in China to treat female hemorrhoids ('' Wushi'er bingfang'' translated as "Recipes for 52 kinds of diseases" unearthed from the Mawangdui

Mawangdui () is an archaeological site located in Changsha, China. The site consists of two saddle-shaped hills and contained the tombs of three people from the Changsha Kingdom during the western Han dynasty (206 BC – 9 AD): the Chancellor Li ...

).

''Qing-hao'' was first recommended for acute intermittent fever episodes by Ge Hong

Ge Hong (; b. 283 – d. 343 or 364), courtesy name Zhichuan (稚川), was a Chinese linguist, Taoist practitioner, philosopher, physician, politician, and writer during the Eastern Jin dynasty. He was the author of '' Essays on Chinese Characte ...

as an effective medication in the 4th-century Chinese manuscript ''Zhou hou bei ji fang'', usually translated as "Emergency Prescriptions kept in one's Sleeve". His recommendation was to soak fresh plants of the artemisia

Artemisia may refer to:

People

* Artemisia I of Caria (fl. 480 BC), queen of Halicarnassus under the First Persian Empire, naval commander during the second Persian invasion of Greece

* Artemisia II of Caria (died 350 BC), queen of Caria under th ...

herb in cold water, wring them out, and ingest the expressed bitter juice in their raw state.

"Roman fever" refers to a particularly deadly strain of malaria that affected the Roman Campagna and the city of Rome throughout various epochs in history. An epidemic of Roman fever during the fifth century AD may have contributed to the fall of the Roman empire.The many remedies to reduce the spleen in Pedanius Dioscorides's '' De Materia Medica'' have been suggested to have been a response to chronic malaria in the Roman empire. Some so-called "vampire burial

A vampire burial or anti-vampire burial is a burial performed in a way which was believed to prevent the deceased from revenance in the form of a vampire or to prevent an "actual" vampire from revenance. Traditions, known from the medieval times ...

s" in late antiquity may have been performed in response to malaria epidemics. For example, some children who died of malaria were buried in the necropolis

A necropolis (plural necropolises, necropoles, necropoleis, necropoli) is a large, designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. The name stems from the Ancient Greek ''nekropolis'', literally meaning "city of the dead".

The term usually im ...

at Lugnano in Teverina

Lugnano in Teverina is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Terni in the Italy, Italian region Umbria, located about 60 km south of Perugia and about 25 km west of Terni.

Lugnano in Teverina borders the following municipalities ...

using rituals meant to prevent them from returning from the dead. Modern scholars hypothesize that communities feared that the dead would return and spread disease.

In 835, the celebration of Hallowmas (All Saints Day) was moved from May to November at the behest of Pope Gregory IV, on the "practical grounds that Rome in summer could not accommodate the great number of pilgrims who flocked to it", and perhaps because of public health considerations regarding Roman Fever, which claimed a number of lives of pilgrims during the sultry summers of the region.

Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, treatments for malaria (and other diseases) included blood-letting, inducing vomiting, limb amputations, and trepanning. Physicians and surgeons in the period used herbal medicines like belladonna to bring about pain relief in affected patients.European Renaissance

The name malaria is derived from ''mal aria'' ('bad air' inMedieval Italian

Italian (''italiano'' or ) is a Romance languages, Romance language of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family that evolved from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire. Together with Sardinian language, Sardinian, Italian i ...

). This idea came from the Ancient Romans, who thought that this disease came from pestilential fumes in the swamps. The word malaria has its roots in the miasma theory

The miasma theory (also called the miasmatic theory) is an obsolete medical theory that held that diseases—such as cholera, chlamydia, or the Black Death—were caused by a ''miasma'' (, Ancient Greek for 'pollution'), a noxious form of "bad ...

, as described by historian and chancellor of Florence Leonardo Bruni in his ''Historiarum Florentini populi libri XII'', which was the first major example of Renaissance historical writing:

The coastal plains of southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

fell from international prominence when malaria expanded in the sixteenth century. At roughly the same time, in the coastal marshes of England, mortality from "marsh fever" or "tertian ague" (''ague'': via French from medieval Latin ''acuta'' (''febris''), acute fever) was comparable to that in sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

today. William Shakespeare was born at the start of the especially cold period that climatologists call the "Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Ma ...

", yet he was aware enough of the ravages of the disease to mention it in eight of his plays. Malaria was commonplace in London and its marshes then and even into the mid-Victorian era.

Medical accounts and ancient autopsy reports state that tertian malarial fevers caused the death of four members of the prominent Medici family of Florence . These claims have been confirmed with more modern methodologies.

The Spread to the Americas

Malaria was not referenced in the "medical books" of the Mayans orAztecs

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those g ...

. Despite this, antibodies against malaria have been detected in some South American mummies, indicating that some malaria strains in the Americas might have a pre-Columbian origin. European settlers and the West Africans they enslaved likely brought malaria to the Americas in the 16th century.

In the book '' 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created'', the author Charles Mann cites sources that speculate that the reason African slaves were brought to the British Americas was because of their resistance to malaria. The colonies needed low-paid agricultural labor, and large numbers of poor British were ready to emigrate. North of the Mason–Dixon line, where malaria-transmitting mosquitoes did not fare well, British indentured servants proved more profitable, as they would work toward their freedom. However, as malaria spread to places such as the tidewater of Virginia and South Carolina, the owners of large plantations came to rely on the enslavement of more malaria-resistant West Africans, while white small landholders risked ruin whenever they got sick. The disease also helped weaken the Native American population and made them more susceptible to other diseases.

Malaria caused huge losses to British forces in the South during the Revolutionary War as well as to Union forces during the Civil War.

Cinchona tree

Spanishmissionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

found that fever was treated by Amerindians near Loxa ( Ecuador) with powder from Peruvian bark (later established to be from any of several trees of genus ''Cinchona

''Cinchona'' (pronounced or ) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Rubiaceae containing at least 23 species of trees and shrubs. All are native to the Tropical Andes, tropical Andean forests of western South America. A few species are ...

''). It was used by the Quechua Indians of Ecuador to reduce the shaking effects caused by severe chills. Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

Brother Agostino Salumbrino (1561–1642), who lived in Lima and was an apothecary by training, observed the Quechua using the bark of the cinchona

''Cinchona'' (pronounced or ) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Rubiaceae containing at least 23 species of trees and shrubs. All are native to the Tropical Andes, tropical Andean forests of western South America. A few species are ...

tree for that purpose. While its effect in treating malaria (and hence malaria-induced shivering) was unrelated to its effect in controlling shivering from cold, it was nevertheless effective for malaria. The use of the "fever tree" bark was introduced into European medicine by Jesuit missionaries ( Jesuit's bark). Jesuit Bernabé de Cobo (1582–1657), who explored Mexico and Peru, is credited with taking cinchona bark to Europe. He brought the bark from Lima to Spain, and then to Rome and other parts of Italy, in 1632. Francesco Torti

Francesco Torti (30 November 1658 – 15 February 1741) was an Italian physician.

Biography

Torti was born in Modena and studied at the University of Bologna, graduating in 1678. In 1670 he and Bernardino Ramazzini headed the department of medic ...

wrote in 1712 that only "intermittent fever" was amenable to the fever tree bark. This work finally established the specific nature of cinchona bark and brought about its general use in medicine.

It would be nearly 200 years before the active principles, quinine and other alkaloids, of cinchona bark were isolated. Quinine, a toxic plant alkaloid, is, in addition to its anti-malarial properties, moderately effective against nocturnal leg cramps.

Clinical indications

In 1717, the dark pigmentation of a postmortem spleen and brain was published by the epidemiologistGiovanni Maria Lancisi

Giovanni Maria Lancisi (26 October 1654 – 20 January 1720) was an Italian physician, epidemiologist and anatomist who made a correlation between the presence of mosquitoes and the prevalence of malaria. He was also known for his studies about c ...

in his malaria textbook ''De noxiis paludum effluviis eorumque remediis''. This was one of the earliest reports of the characteristic enlargement of the spleen and dark color of the spleen and brain, which are the most constant post-mortem indications of chronic malaria infection. He related the prevalence of malaria in swampy areas to the presence of flies and recommended swamp

A swamp is a forested wetland.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Swamps are considered to be transition zones because both land and water play a role in ...

drainage to prevent it.

19th century

In the nineteenth century, the first drugs were developed to treat malaria, and parasites were first identified as its source.Antimalarial drugs

Quinine

French chemist

French chemist Pierre Joseph Pelletier

Pierre-Joseph Pelletier (, , ; 22 March 1788 – 19 July 1842) was a French chemist and pharmacist who did notable research on vegetable alkaloids, and was the co-discoverer with Joseph Bienaimé Caventou of quinine, caffeine, and strychnine. ...

and French pharmacist Joseph Bienaimé Caventou

Joseph Bienaimé Caventou (30 June 1795 – 5 May 1877) was a French pharmacist. He was a professor at the École de Pharmacie (School of Pharmacy) in Paris. He collaborated with Pierre-Joseph Pelletier in a Parisian laboratory located behind an ...

separated in 1820 the alkaloids cinchonine

Cinchonine is an alkaloid found in '' Cinchona officinalis''. It is used in asymmetric synthesis in organic chemistry. It is a stereoisomer and pseudo- enantiomer of cinchonidine.

It is structurally similar to quinine, an antimalarial

Antima ...

and quinine from powdered fever tree bark, allowing for the creation of standardized doses of the active ingredients. Prior to 1820, the bark was simply dried, ground to a fine powder and mixed into a liquid (commonly wine) for drinking.

Manuel Incra Mamani spent four years collecting cinchona seeds in the Andes in Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

, highly prized for their quinine but whose export was prohibited. He provided them to an English trader, Charles Ledger

Charles Ledger (4 March 1818 – 19 May 1905)B. G. Andrews,, '' Australian Dictionary of Biography'', Volume 5, MUP, 1974, pp 73-74. Retrieved 9 Sep 2009

was an alpaca farmer noted for his work in connection with quinine, a treatment for malari ...

, who sent the seeds to his brother in England to sell. They sold them to the Dutch government, who cultivated 20,000 trees of the ''Cinchona ledgeriana

''Cinchona calisaya'' is a species of shrub or tree in the family Rubiaceae. It is native to the forests of the eastern slopes of the Andes, where they grow from in elevation in Peru and Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bo ...

'' in Java (Indonesia). By the end of the nineteenth century, the Dutch had established a world monopoly over its supply.

'Warburg's Tincture'

In 1834, inBritish Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies, which resides on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first European to encounter Guiana was S ...

, a German physician, Carl Warburg

Carl Warburg (c. 1805–1892), also known as Charles Warburg, was a physician and scientist. He was the inventor of 'Warburg's Tincture', a medicine well known in the 19th century for treating fevers, including malaria.Sparkes, Roland. Article ...

, invented an antipyretic medicine: 'Warburg's Tincture Warburg's tincture was a pharmaceutical drug, now obsolete. It was invented in 1834 by Dr. Carl Warburg.

Warburg's tincture was well known in the Victorian era as a medicine for fevers, especially tropical fevers, including malaria. It was conside ...

'. This secret, proprietary remedy contained quinine and other herbs

In general use, herbs are a widely distributed and widespread group of plants, excluding vegetables and other plants consumed for macronutrients, with savory or aromatic properties that are used for flavoring and garnishing food, for medicinal ...

. Trials were held in Europe in the 1840s and 1850s. It was officially adopted by the Austrian Empire in 1847. It was considered by many eminent medical professionals to be a more efficacious antimalarial than quinine. It was also more economical. The British government supplied Warburg's Tincture to troops in India and other colonies.

Methylene blue

In 1876,methylene blue

Methylthioninium chloride, commonly called methylene blue, is a salt used as a dye and as a medication. Methylene blue is a thiazine dye. As a medication, it is mainly used to treat methemoglobinemia by converting the ferric iron in hemoglobin ...

was synthesized by German chemist Heinrich Caro. Paul Ehrlich in 1880 described the use of "neutral" dyes—mixtures of acid

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a sequ ...

ic and basic

BASIC (Beginners' All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) is a family of general-purpose, high-level programming languages designed for ease of use. The original version was created by John G. Kemeny and Thomas E. Kurtz at Dartmouth College ...

dyes—for the differentiation of cells in peripheral blood smears. In 1891, Ernst Malachowski and Dmitri Leonidovich Romanowsky

Dmitri Leonidovich Romanowsky (sometimes spelled Dmitry and Romanowski, russian: Дмитрий Леонидович Романовский; 1861–1921) was a Russian physician who is best known for his invention of an eponymous histological stai ...

independently developed techniques using a mixture of Eosin Y and modified methylene blue (methylene azure) that produced a surprising hue unattributable to either staining component: a shade of purple. Malachowski used alkali-treated methylene blue solutions and Romanowsky used methylene blue solutions that were molded or aged. This new method differentiated blood cell

A blood cell, also called a hematopoietic cell, hemocyte, or hematocyte, is a cell produced through hematopoiesis and found mainly in the blood. Major types of blood cells include red blood cells (erythrocytes), white blood cells (leukocytes), ...

s and demonstrated the nuclei of malarial parasites. Malachowski's staining technique was one of the most significant technical advances in the history of malaria.

In 1891, Paul Guttmann

Paul Guttmann (9 September 1834 in Ratibor ( pl, Racibórz) – 24 May 1893 in Berlin) was a German pathologist.

He studied medicine in Berlin, Würzburg and Vienna, earning his doctorate in 1858. From 1859 he worked in Berlin, where he later be ...

and Ehrlich noted that methylene blue

Methylthioninium chloride, commonly called methylene blue, is a salt used as a dye and as a medication. Methylene blue is a thiazine dye. As a medication, it is mainly used to treat methemoglobinemia by converting the ferric iron in hemoglobin ...

had a high affinity for some tissues and that this dye had a slight antimalarial property. Methylene blue and its congeners may act by preventing the biocrystallization

Biocrystallization is the formation of crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice t ...

of heme.

Cause: Identification of ''Plasmodium'' and ''Anopheles''

In 1848, German anatomist Johann Heinrich Meckel recorded black-brown pigment granules in the blood and spleen of a patient who had died in a mental hospital. Meckel was thought to have been looking at malaria parasites without realizing it; he did not mention malaria in his report. He hypothesized that the pigment was melanin. The causal relationship of pigment to the parasite was established in 1880, when French physicianCharles Louis Alphonse Laveran

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran (18 June 1845 – 18 May 1922) was a French physician who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1907 for his discoveries of parasitic protozoans as causative agents of infectious diseases such as malaria ...

, working in the military hospital of Constantine, Algeria

Constantine ( ar, قسنطينة '), also spelled Qacentina or Kasantina, is the capital of Constantine Province in northeastern Algeria. During Roman Empire, Roman times it was called Cirta and was renamed "Constantina" in honor of emperor Const ...

, observed pigmented parasites inside the red blood cells of people with malaria. He witnessed the events of exflagellation and became convinced that the moving flagella

A flagellum (; ) is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are termed as flagellates.

A microorganism may have f ...

were parasitic microorganisms

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

. He noted that quinine removed the parasites from the blood. Laveran called this microscopic organism ''Oscillaria malariae'' and proposed that malaria was caused by this protozoa

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris. Histo ...

n. This discovery remained controversial until the development of the oil immersion

In light microscopy, oil immersion is a technique used to increase the resolving power of a microscope. This is achieved by immersing both the objective lens and the specimen in a transparent oil of high refractive index, thereby increasing the ...

lens in 1884 and of superior staining methods in 1890–1891.

In 1885, Ettore Marchiafava

Ettore Marchiafava (3 January 1847 – 22 October 1935) was an Italian physician, pathologist and neurologist. He spent most of his career as professor of medicine at the University of Rome (now Sapienza Università di Roma). His works on malar ...

, Angelo Celli

Angelo Celli (25 March 1857 – 2 November 1914) was an Italian physician, hygienist, parasitologist and philanthropist known for his pioneering work on the malarial parasite and control of malaria. He was Professor of Hygiene at the Universit ...

and Camillo Golgi

Camillo Golgi (; 7 July 184321 January 1926) was an Italian biologist and pathologist known for his works on the central nervous system. He studied medicine at the University of Pavia (where he later spent most of his professional career) betwee ...

studied the reproduction cycles in human blood (Golgi cycles). Golgi observed that all parasites present in the blood divided almost simultaneously at regular intervals and that division coincided with attacks of fever. In 1886 Golgi described the morphological differences that are still used to distinguish two malaria parasite species '' Plasmodium vivax'' and '' Plasmodium malariae''. Shortly after this Sakharov in 1889 and Marchiafava & Celli in 1890 independently identified ''Plasmodium falciparum

''Plasmodium falciparum'' is a Unicellular organism, unicellular protozoan parasite of humans, and the deadliest species of ''Plasmodium'' that causes malaria in humans. The parasite is transmitted through the bite of a female ''Anopheles'' mosqu ...

'' as a species distinct from ''P. vivax'' and ''P. malariae''. In 1890, Grassi and Feletti reviewed the available information and named both ''P. malariae'' and ''P. vivax'' (although within the genus ''Haemamoeba

''Haemamoeba'' is a subgenus of the genus ''Plasmodium'' — all of which are parasites. The subgenus was created in 1963 by created by Corradetti ''et al.''. Species in this subgenus infect birds.

__TOC__ Diagnostic features

Species in the su ...

''.) By 1890, Laveran's germ was generally accepted, but most of his initial ideas had been discarded in favor of the taxonomic work and clinical pathology of the Italian school. Marchiafava and Celli called the new microorganism '' Plasmodium''. ''H. vivax'' was soon renamed ''Plasmodium vivax''. In 1892, Marchiafava and Bignami proved that the multiple forms seen by Laveran were from a single species. This species was eventually named ''P. falciparum''. Laveran was awarded the 1907 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine "in recognition of his work on the role played by protozoa in causing diseases".

Dutch physician Pieter Pel first proposed a tissue stage of the malaria parasite in 1886, presaging its discovery by over 50 years. This suggestion was reiterated in 1893 when Golgi suggested that the parasites might have an undiscovered tissue phase (this time in endothelial cells). Golgi's latent phase theory was supported by Pel in 1896.

The establishment of the scientific method from about the mid-19th century on demanded testable hypotheses and verifiable phenomena for causation and transmission. Anecdotal reports, and the discovery in 1881 that mosquitoes were the vector of yellow fever, eventually led to the investigation of mosquitoes in connection with malaria.

An early effort at malaria prevention occurred in 1896 in Massachusetts. An Uxbridge outbreak prompted health officer Dr. Leonard White to write a report to the State Board of Health, which led to a study of mosquito-malaria links and the first efforts for malaria prevention. Massachusetts state pathologist, Theobald Smith, asked that White's son collect mosquito specimens for further analysis, and that citizens add

The establishment of the scientific method from about the mid-19th century on demanded testable hypotheses and verifiable phenomena for causation and transmission. Anecdotal reports, and the discovery in 1881 that mosquitoes were the vector of yellow fever, eventually led to the investigation of mosquitoes in connection with malaria.

An early effort at malaria prevention occurred in 1896 in Massachusetts. An Uxbridge outbreak prompted health officer Dr. Leonard White to write a report to the State Board of Health, which led to a study of mosquito-malaria links and the first efforts for malaria prevention. Massachusetts state pathologist, Theobald Smith, asked that White's son collect mosquito specimens for further analysis, and that citizens add screens

Screen or Screens may refer to:

Arts

* Screen printing (also called ''silkscreening''), a method of printing

* Big screen, a nickname associated with the motion picture industry

* Split screen (filmmaking), a film composition paradigm in which mul ...

to windows, and drain

Drain may refer to:

Objects and processes

* Drain (plumbing), a fixture that provides an exit-point for waste water or for water that is to be re-circulated on the side of a road

* Drain (surgery), a tube used to remove pus or other fluids from ...

collections of water.

Britain's Sir Ronald Ross, an army surgeon working in Secunderabad

Secunderabad, also spelled as Sikandarabad (, ), is a twin cities, twin city of Hyderabad and one of the six zones of the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) in the States and union territories of India, Indian state of Telangana. It ...

, India, proved in 1897 that malaria is transmitted by mosquitoes, an event now commemorated by World Mosquito Day

World Mosquito Day, observed annually on 20 August, is a commemoration of British doctor Sir Ronald Ross's discovery in 1897 that female anopheline mosquitoes transmit malaria between humans. Prior to the discovery of the transmitting organism, ...

. He was able to find pigmented malaria parasites in a mosquito that he artificially fed on a malaria patient who had crescents in his blood. He continued his research into malaria by showing that certain mosquito species ('' Culex fatigans'') transmit malaria to sparrows

Sparrow may refer to:

Birds

* Old World sparrows, family Passeridae

* New World sparrows, family Passerellidae

* two species in the Passerine family Estrildidae:

** Java sparrow

** Timor sparrow

* Hedge sparrow, also known as the dunnock or hed ...

and he isolated malaria parasites from the salivary glands of mosquitoes that had fed on infected birds. He reported this to the British Medical Association

The British Medical Association (BMA) is a registered trade union for doctors in the United Kingdom. The association does not regulate or certify doctors, a responsibility which lies with the General Medical Council. The association's headquar ...

in Edinburgh in 1898.

Giovanni Battista Grassi

Giovanni Battista Grassi (27 March 1854 – 4 May 1925) was an Italian physician and zoologist, best known for his pioneering works on parasitology, especially on malariology. He was Professor of Comparative Zoology at the University of Catania ...

, professor of Comparative Anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

at Rome University, showed that human malaria could only be transmitted by '' Anopheles'' (Greek ''anofelís'': good-for-nothing) mosquitoes. Grassi, along with coworkers Amico Bignami

Amico Bignami (15 April 1862 – 8 September 1929) was an Italian physician, pathologist, malariologist and sceptic. He was professor of pathology at Sapienza University of Rome. His most important scientific contribution was in the discovery of ...

, Giuseppe Bastianelli

Giuseppe Bastianelli (25 October 1862 – 30 March 1959) was an Italian physician and zoologist who worked on malaria and was the personal physician of Pope Benedict XV.

Born in Rome, Bastianelli was initially interested in chemistry, physiology ...

and Ettore Marchiafava, announced at the session of the Accademia dei Lincei

The Accademia dei Lincei (; literally the "Academy of the Lynx-Eyed", but anglicised as the Lincean Academy) is one of the oldest and most prestigious European scientific institutions, located at the Palazzo Corsini on the Via della Lungara in Rom ...

on 4 December 1898 that a healthy man in a non-malarial zone had contracted tertian malaria after being bitten by an experimentally infected ''Anopheles claviger'' specimen.

In 1898–1899, Bastianelli, Bignami and Grassi were the first to observe the complete transmission cycle of ''P. falciparum'', ''P. vivax'' and ''P. malaria'' from mosquito to human and back in ''A. claviger''.

A dispute broke out between the British and Italian schools of malariology over priority, but Ross received the 1902 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for "his work on malaria, by which he has shown how it enters the organism and thereby has laid the foundation for successful research on this disease and methods of combating it."

Synthesis of quinine

William Henry Perkin, a student of August Wilhelm von Hofmann at theRoyal College of Chemistry

The Royal College of Chemistry: the laboratories. Lithograph

The Royal College of Chemistry (RCC) was a college originally based on Oxford Street in central London, England. It operated between 1845 and 1872.

The original building was designed ...

in London, unsuccessfully tried in the 1850s to synthesize quinine in a commercial process. The idea was to take two equivalents of N-allyltoluidine () and three atoms of oxygen to produce quinine () and water. Instead, Perkin's mauve

Mauveine, also known as aniline purple and Perkin's mauve, was one of the first synthetic dyes. It was discovered serendipitously by William Henry Perkin in 1856 while he was attempting to synthesise the phytochemical quinine for the treatment of ...

was produced when attempting quinine total synthesis via the oxidation of N-allyltoluidine. Before Perkin's discovery, all dye

A dye is a colored substance that chemically bonds to the substrate to which it is being applied. This distinguishes dyes from pigments which do not chemically bind to the material they color. Dye is generally applied in an aqueous solution an ...

s and pigments were derived from roots, leaves, insects, or, in the case of Tyrian purple, molluscs.

Quinine wouldn't be successfully synthesized until 1918. Synthesis remains elaborate, expensive and low yield, with the additional problem of separation of the stereoisomers. Though quinine is not one of the major drugs used in treatment, modern production still relies on extraction from the cinchona tree.

20th century

Etiology: Plasmodium tissue stage and reproduction

Relapses were first noted in 1897 by William S. Thayer, who recounted the experiences of a physician who relapsed 21 months after leaving an endemic area. He proposed the existence of a tissue stage. Relapses were confirmed by Patrick Manson, who allowed infected ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes to feed on his eldest son. The younger Manson then described a relapse nine months after his apparent cure with quinine. Also, in 1900 Amico Bignami and Giuseppe Bastianelli found that they could not infect an individual with blood containing onlygametocyte

A gametocyte is a eukaryotic germ cell that divides by mitosis into other gametocytes or by meiosis into gametids during gametogenesis. Male gametocytes are called ''spermatocytes'', and female gametocytes are called ''oocytes''.

Development

...

s. The possibility of the existence of a chronic blood stage infection was proposed by Ronald Ross and David Thompson in 1910.

The existence of asexually-reproducing avian malaria parasites in cells of the internal organs was first demonstrated by Henrique de Beaurepaire Aragão in 1908.

Three possible mechanisms of relapse were proposed by Marchoux in 1926 (i) parthenogenesis of macrogametocyte

A gametocyte is a eukaryotic germ cell that divides by mitosis into other gametocytes or by meiosis into gametids during gametogenesis. Male gametocytes are called ''spermatocytes'', and female gametocytes are called ''oocytes''.

Development

...

s: (ii) persistence of schizonts in small numbers in the blood where immunity inhibits multiplication, but later disappears and/or (iii) reactivation of an encysted body in the blood. James in 1931 proposed that sporozoites are carried to internal organs, where they enter reticuloendothelial

In immunology, the mononuclear phagocyte system or mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS) also known as the reticuloendothelial system or macrophage system is a part of the immune system that consists of the phagocytic cells located in reticular co ...

cells and undergo a cycle of development, based on quinine's lack of activity on them. Huff and Bloom in 1935 demonstrated stages of avian malaria that transpire outside blood cells (exoerythrocytic). In 1945 Fairley ''et al.'' reported that inoculation of blood from a patient with ''P. vivax'' may fail to induce malaria, although the donor may subsequently exhibit the condition. Sporozoites disappeared from the blood stream within one hour and reappeared eight days later. This suggests the presence of forms that persist in tissues. Using mosquitoes rather than blood, in 1946 Shute described a similar phenomenon and proposed the existence of an 'x-body' or resting form. The following year Sapero proposed a link between relapse and a tissue stage not yet discovered. Garnham in 1947 described exoerythrocytic schizogony

Fission, in biology, is the division of a single entity into two or more parts and the regeneration of those parts to separate entities resembling the original. The object experiencing fission is usually a cell, but the term may also refer to how ...

in ''Hepatocystis

''Hepatocystis'' is a genus of parasites transmitted by midges of the genus ''Culicoides''. Hosts include Old World primates, bats, hippopotamus and squirrels. This genus is not found in the New World. The genus was erected by Levaditi and Schoe ...

(Plasmodium) kochi''. In the following year, Shortt and Garnham described the liver stages of ''P. cynomolgi'' in monkeys. In the same year, a human volunteer consented to receive a massive dose of infected sporozoites of '' P. vivax'' and undergo a liver biopsy three months later, thus allowing Shortt ''et al.'' to demonstrate the tissue stage. The tissue form of '' Plasmodium ovale'' was described in 1954 and that of ''P. malariae'' in 1960 in experimentally infected chimpanzees.

The latent or dormant liver form of the parasite ( hypnozoite), apparently responsible for the relapses characteristic of ''P. vivax'' and ''P. ovale'' infections, was first observed in the 1980s. The term ''hypnozoite'' was coined by Miles B. Markus while a student. In 1976, he speculated: "If sporozoites of '' Isospora'' can behave in this fashion, then those of related Sporozoa, like malaria parasites, may have the ability to survive in the tissues in a similar way." In 1982, Krotoski ''et al'' reported identification of ''P. vivax'' hypnozoites in liver cells of infected chimpanzees.

From 1980 onwards and until recently (even in 2022), recurrences of ''P. vivax'' malaria have been thought to be mostly hypnozoite-mediated. Between 2018 and 2021, however, it was reported that vast numbers of non-circulating, non-hypnozoite parasites occur unobtrusively in tissues of ''P. vivax''-infected people, with only a small proportion of the total parasite biomass present in the peripheral bloodstream. This finding supports an intellectually insightful paradigm-shifting viewpoint, which has prevailed since 2011 (albeit not believed between 2011 and 2018 or later by most malariologists), that an unknown percentage of ''P. vivax'' recurrences are recrudescences (having a non-circulating or sequestered merozoite origin), and not relapses (which have a hypnozoite source). The recent discoveries did not give rise to this new theory, which was pre-existing. They merely confirmed the validity thereof.

Malariotherapy

In the early twentieth century, before antibiotics, patients with tertiarysyphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

were intentionally infected with malaria to induce a fever; this was called malariotherapy. In 1917, Julius Wagner-Jauregg

Julius Wagner-Jauregg (; 7 March 1857 – 27 September 1940) was an Austrian physician, who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1927, and is the first psychiatrist to have done so. His Nobel award was "for his discovery of the therapeu ...

, a Viennese psychiatrist, began to treat neurosyphilitics with induced '' Plasmodium vivax'' malaria. Three or four bouts of fever were enough to kill the temperature-sensitive syphilis bacteria (''Spirochaeta pallida'' also known as ''Treponema pallidum''). ''P. vivax'' infections were then terminated by quinine. By accurately controlling the fever with quinine, the effects of both syphilis and malaria could be minimized. While about 15% of patients died from malaria, this was preferable to the almost-certain death from syphilis. Malaria therapy, Therapeutic malaria opened up a wide field of chemotherapeutic research and was practiced until 1950. Wagner-Jauregg was awarded the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of the therapeutic value of malaria inoculation in the treatment of dementia paralytica.

Henry Heimlich advocated malariotherapy as a treatment for AIDS, and some studies of malariotherapy for HIV infection have been performed in China. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does not recommend the use of malariotherapy for HIV.

Panama Canal and vector control

In 1881, Dr. Carlos Finlay, a Cuban-born physician of Scottish ancestry, theorized that yellow fever was transmitted by a specific mosquito, later designated ''Aedes aegypti''. The theory remained controversial for twenty years until it was confirmed in 1901 by Walter Reed. This was the first scientific proof of a disease being transmitted exclusively by an insect vector, and demonstrated that control of such diseases necessarily entailed control or eradication of their insect vector. Yellow fever and malaria among workers had seriously delayed construction of the Panama Canal. Mosquito control instituted by William C. Gorgas dramatically reduced this problem.Antimalarial drugs

Chloroquine

Hans Andersag, Johann "Hans" Andersag and colleagues synthesized and tested some 12,000 compounds, eventually producing Resochin as a substitute for quinine in the 1930s. It is chemically related to quinine through the possession of a quinoline nucleus and the dialkylaminoalkylamino side chain. Resochin (7-chloro-4- 4- (diethylamino) – 1 – methylbutyl amino quinoline) and a similar compound Sontochin (3-methyl Resochin) were synthesized in 1934. In March 1946, the drug was officially named Chloroquine. Chloroquine is an inhibitor of hemozoin production through

Hans Andersag, Johann "Hans" Andersag and colleagues synthesized and tested some 12,000 compounds, eventually producing Resochin as a substitute for quinine in the 1930s. It is chemically related to quinine through the possession of a quinoline nucleus and the dialkylaminoalkylamino side chain. Resochin (7-chloro-4- 4- (diethylamino) – 1 – methylbutyl amino quinoline) and a similar compound Sontochin (3-methyl Resochin) were synthesized in 1934. In March 1946, the drug was officially named Chloroquine. Chloroquine is an inhibitor of hemozoin production through biocrystallization

Biocrystallization is the formation of crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice t ...

. Quinine and chloroquine affect malarial parasites only at life stages when the parasites are forming hematin-pigment (hemozoin) as a byproduct of hemoglobin degradation.

Chloroquine-resistant forms of ''P. falciparum'' emerged only 19 years later. The first resistant strains were detected around the Cambodia‐Thailand border and in Colombia, in the 1950s. In 1989, chloroquine resistance in ''P. vivax'' was reported in Papua New Guinea. These resistant strains spread rapidly, producing a large mortality increase, particularly in Africa during the 1990s.

Artemisinins

Systematic screening of Chinese herbology, traditional Chinese medical herbs was carried out by Chinese research teams, consisting of hundreds of scientists in the 1960s and 1970s. Qinghaosu, later named artemisinin, was cold-extracted in a neutral milieu (pH 7.0) from the dried leaves of ''Artemisia annua

''Artemisia annua'', also known as sweet wormwood, sweet annie, sweet sagewort, annual mugwort or annual wormwood (), is a common type of wormwood native to temperate Asia, but naturalized in many countries including scattered parts of North Am ...

''.

Artemisinin was isolated by pharmacologist Tu Youyou (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 2015). Tu headed a team tasked by the Chinese government with finding a treatment for chloroquine-resistant malaria. Their work was known as Project 523, named after the date it was announced – 23 May 1967. The team investigated more than 2000 Chinese herb preparations and by 1971 had made 380 extracts from 200 herbs. An extract from qinghao (''Artemisia annua

''Artemisia annua'', also known as sweet wormwood, sweet annie, sweet sagewort, annual mugwort or annual wormwood (), is a common type of wormwood native to temperate Asia, but naturalized in many countries including scattered parts of North Am ...

'') was effective, but the results were variable. Tu reviewed the literature, including ''Zhou hou bei ji fang'' (A handbook of prescriptions for emergencies) written in 340 BC by Chinese physician Ge Hong. This book contained the only useful reference to the herb: "A handful of qinghao immersed in two litres of water, wring out the juice and drink it all." Tu's team subsequently isolated a nontoxic, neutral extract that was 100% effective against parasitemia in animals. The first successful trials of artemisinin were in 1979.

Artemisinin is a sesquiterpene lactone containing a peroxide group, which is believed to be essential for its anti-malarial activity. Its derivatives, artesunate and artemether, have been used in clinics since 1987 for the treatment of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive malaria, especially cerebral malaria. These drugs are characterized by fast action, high efficacy, and good tolerance. They kill the asexual forms of ''Plasmodium berghei, P. berghei'' and ''P. cynomolgi'' and have transmission-blocking activity. In 1985, Zhou Yiqing and his team combined artemether and lumefantrine into a single tablet, which was registered as a medicine in China in 1992. Later, it became known as Artemether/lumefantrine, "Coartem". Artemisinin combination treatments (ACTs) are now widely used to treat uncomplicated ''falciparum'' malaria, but access to ACTs is still limited in most malaria-endemic countries, and only a minority of the patients who need artemisinin-based combination treatments receive them.

In 2008, White predicted that improved agricultural practices, selection of high-yielding hybrids, Microorganism, microbial production, and the development of synthetic peroxides would lower prices.

Artemisinin is a sesquiterpene lactone containing a peroxide group, which is believed to be essential for its anti-malarial activity. Its derivatives, artesunate and artemether, have been used in clinics since 1987 for the treatment of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive malaria, especially cerebral malaria. These drugs are characterized by fast action, high efficacy, and good tolerance. They kill the asexual forms of ''Plasmodium berghei, P. berghei'' and ''P. cynomolgi'' and have transmission-blocking activity. In 1985, Zhou Yiqing and his team combined artemether and lumefantrine into a single tablet, which was registered as a medicine in China in 1992. Later, it became known as Artemether/lumefantrine, "Coartem". Artemisinin combination treatments (ACTs) are now widely used to treat uncomplicated ''falciparum'' malaria, but access to ACTs is still limited in most malaria-endemic countries, and only a minority of the patients who need artemisinin-based combination treatments receive them.

In 2008, White predicted that improved agricultural practices, selection of high-yielding hybrids, Microorganism, microbial production, and the development of synthetic peroxides would lower prices.

Insecticides

Efforts to control the spread of malaria had a major setback in 1930: Entomology, entomologist Raymond Corbett Shannon discovered imported disease-bearing ''Anopheles gambiae'' mosquitoes living in Brazil (DNA analysis later revealed the actual species to be ''A. arabiensis''). This species of mosquito is a particularly efficient vector for malaria and is native to Africa. In 1938, the introduction of this vector caused the greatest epidemic of malaria ever seen in the New World. However, complete eradication of ''A. gambiae'' from northeast Brazil and thus from the New World was achieved in 1940 by the systematic application of the arsenic-containing compound Paris green to breeding places, and of pyrethrum spray-killing to adult resting places.DDT

The Austrian chemist Othmar Zeidler is credited with the first synthesis of DDT (DichloroDiphenylTrichloroethane) in 1874. The insecticidal properties of DDT were identified in 1939 by chemist Paul Hermann Müller of Novartis, Geigy Pharmaceutical. For his discovery of DDT as a contact poison against several arthropods, he was awarded the 1948 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. In the fall of 1942, samples of the chemical were acquired by the United States, Britain and Germany. Laboratory tests demonstrated that it was highly effective against many insects. Rockefeller Foundation studies showed in Mexico that DDT remained effective for six to eight weeks if sprayed on the inside walls and ceilings of houses and other buildings. The first field test in which residual DDT was applied to the interior surfaces of all habitations and outbuildings was carried out in central Italy in the spring of 1944. The objective was to determine the residual effect of the spray on anopheline density in the absence of other control measures. Spraying began in Castel Volturno and, after a few months, in the delta of the Tiber. The unprecedented effectiveness of the chemical was confirmed: the newinsecticide

Insecticides are substances used to kill insects. They include ovicides and larvicides used against insect eggs and larvae, respectively. Insecticides are used in agriculture, medicine, industry and by consumers. Insecticides are claimed to b ...

was able to eradicate malaria by eradicating mosquitoes. At the end of World War II, a massive malaria control program based on DDT spraying was carried out in Italy. In Sardinia – the second largest island in the Mediterranean – between 1946 and 1951, the Rockefeller Foundation conducted a large-scale experiment to test the feasibility of the strategy of "species eradication" in an endemic malaria vector. Malaria was effectively eliminated in the United States by the use of DDT in the National Malaria Eradication Program (1947–52). The concept of eradication prevailed in 1955 in the Eighth World Health Assembly: DDT was adopted as a primary tool in the fight against malaria.

In 1953, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched an antimalarial program in parts of Liberia as a pilot project to determine the feasibility of malaria eradication in tropical Africa. However, these projects encountered difficulties that foreshadowed the general retreat from malaria eradication efforts across tropical Africa by the mid-1960s.

DDT was banned for agricultural uses in the US in 1972 (DDT has never been banned for non-agricultural uses such as malaria control) after the discussion opened in 1962 by ''Silent Spring'', written by American biologist Rachel Carson, which launched the Environmental science, environmental movement in the West. The book catalogued the environmental impacts of indiscriminate DDT spraying and suggested that DDT and other pesticides cause cancer and that their agricultural use was a threat to wildlife. The United States Agency for International Development, U.S. Agency for International Development supports Indoor residual spraying, indoor DDT spraying as a vital component of malaria control programs and has initiated DDT and other insecticide spraying programs in tropical countries.

Pyrethrum

Otherinsecticide

Insecticides are substances used to kill insects. They include ovicides and larvicides used against insect eggs and larvae, respectively. Insecticides are used in agriculture, medicine, industry and by consumers. Insecticides are claimed to b ...

s are available for mosquito control, as well as physical measures, such as draining the wetland breeding grounds and the provision of better sanitation. Pyrethrum (from the flowering plant ''Chrysanthemum'' [or ''Tanacetum''] ''cinerariaefolium'') is an economically important source of natural insecticide. Pyrethrins attack the nervous systems of all insects. A few minutes after application, the insect cannot move or fly, while female mosquitoes are inhibited from biting. The use of pyrethrum in insecticide preparations dates to about 400 Common Era, BCE. Pyrethrins are Biodegradation, biodegradable and break down easily on exposure to light. The majority of the world's supply of pyrethrin and ''Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium'' comes from Kenya. The flower was first introduced into Kenya and the highlands of East Africa, Eastern Africa during the late 1920s. The flowers of the plant are harvested shortly after blooming; they are either dried and powdered, or the oils within the flowers are extracted with solvents.

Research

Avian, mouse and monkey models

Until the 1950s, screening of anti-malarial drugs was carried out on avian malaria. Avian malaria species differ from those that infect humans. The discovery in 1948 of ''Plasmodium berghei'' in wild rodents in the Belgian Congo, Congo and later other rodent species that could infect laboratory rats transformed drug development. The short hepatic phase and life cycle of these parasites made them useful as animal models, a status they still retain. ''Plasmodium cynomolgi'' in rhesus monkeys (''Macaca mulatta'') was used in the 1960s to test drugs active against ''P. vivax''. Growth of the liver stages in animal-free systems was achieved in the 1980s when pre-erythrocytic ''P. berghei'' stages were grown in wI38, a human embryonic cell, embryonic lung cell line (cells cultured from one specimen). This was followed by their growth in the human hepatoma line HepG2. Both ''P. falciparum'' and ''P. vivax'' have been grown in human liver cells; partial development of ''P. ovale'' in human liver cells was achieved; and ''P. malariae'' was grown in chimpanzee and ''Night monkey, monkey'' liver cells. The first successful continuous malaria culture was established in 1976 by William Trager and James B. Jensen, which facilitated research into the molecular biology of the parasite and the development of new drugs. By using increasing volumes of culture medium, ''P.falciparum'' was grown to higher parasitemia levels (above 10%).Diagnostics

The use of antigen-based Malaria antigen detection tests, malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) emerged in the 1980s. In the twenty-first century, Giemsa stain, Giemsa microscopy and RDTs became the two preferred Medical diagnosis, diagnostic techniques. Malaria RDTs do not require special equipment and offer the potential to extend accurate malaria diagnosis to areas lacking microscopy services.A zoonotic malarial parasite

''Plasmodium knowlesi'' has been known since the 1930s in Asian macaque monkeys and as experimentally capable of infecting humans. In 1965, a natural human infection was reported in a U.S. soldier returning from the Pahang Jungle of the Malaysian peninsula.Notes

References

Further reading

* *excerpt and text search

External links

* [http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1948/muller-lecture.pdf Paul H Müller Nobel Lecture 1948: Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane and newer insecticides]

Ronald Ross Nobel Lecture

* [http://www.im.microbios.org/0901/0901069.pdf Grassi versus Ross: Who solved the riddle of malaria?]

Malaria and the Fall of Rome

Centers for Disease Control: History of Malaria

{{DEFAULTSORT:History of Malaria Malaria History of medicine, Malaria