Poland People's Republic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska

In the summer of 1944 the Polish Committee of National Liberation was established by Soviet-backed Polish communists to control territory retaken from Nazi Germany. On 1 January 1945 the committee was replaced by the

In the summer of 1944 the Polish Committee of National Liberation was established by Soviet-backed Polish communists to control territory retaken from Nazi Germany. On 1 January 1945 the committee was replaced by the  The official results of the election showed the Democratic Bloc with 80.1 percent of the vote. The Democratic Bloc was awarded 394 seats to only 28 for the PSL. Mikoإ‚ajczyk immediately resigned to protest this so-called 'implausible result' and fled to the United Kingdom in April rather than face arrest. Later, some historians announced that the official results were only obtained through massive fraud. Government officials didn't even count the real votes in many areas and simply filled in the relevant documents in accordance with instructions from the communists. In other areas, the ballot boxes were either destroyed or replaced with boxes containing prefilled ballots.

The 1947 election marked the beginning of undisguised communist rule in Poland, though it was not officially transformed into the Polish People's Republic until the adoption of the 1952 Constitution. However, Gomuإ‚ka never supported Stalin's control over the Polish communists and was soon replaced as party leader by the more pliable Bierut. In 1948, the communists consolidated their power, merging with Cyrankiewicz' faction of the PPS to form the Polish United Workers' Party (known in Poland as 'the Party'), which would monopolise political power in Poland until 1989. In 1949, Polish-born Soviet Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky became the Minister of National Defence, with the additional title Marshal of Poland, and in 1952 he became Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers (deputy premier).

Over the coming years, private industry was

The official results of the election showed the Democratic Bloc with 80.1 percent of the vote. The Democratic Bloc was awarded 394 seats to only 28 for the PSL. Mikoإ‚ajczyk immediately resigned to protest this so-called 'implausible result' and fled to the United Kingdom in April rather than face arrest. Later, some historians announced that the official results were only obtained through massive fraud. Government officials didn't even count the real votes in many areas and simply filled in the relevant documents in accordance with instructions from the communists. In other areas, the ballot boxes were either destroyed or replaced with boxes containing prefilled ballots.

The 1947 election marked the beginning of undisguised communist rule in Poland, though it was not officially transformed into the Polish People's Republic until the adoption of the 1952 Constitution. However, Gomuإ‚ka never supported Stalin's control over the Polish communists and was soon replaced as party leader by the more pliable Bierut. In 1948, the communists consolidated their power, merging with Cyrankiewicz' faction of the PPS to form the Polish United Workers' Party (known in Poland as 'the Party'), which would monopolise political power in Poland until 1989. In 1949, Polish-born Soviet Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky became the Minister of National Defence, with the additional title Marshal of Poland, and in 1952 he became Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers (deputy premier).

Over the coming years, private industry was

Stefan Wyszyإ„ski, (1901–1981).

Encyclopأ¦dia Britannica. Bierut died in March 1956, and was replaced with Edward Ochab, who held the position for seven months. In June, workers in the industrial city of Poznaإ„ went on strike, in what became known as

In 1970, Gomuإ‚ka's government had decided to adopt massive increases in the prices of basic goods, including food. The resulting widespread violent protests in December that same year resulted in a number of deaths. They also forced another major change in the government, as Gomuإ‚ka was replaced by Edward Gierek as the new First Secretary. Gierek's plan for recovery was centered on massive borrowing, mainly from the United States and West Germany, to re-equip and modernize Polish industry, and to import consumer goods to give the workers some incentive to work. While it boosted the Polish economy, and is still remembered as the "Golden Age" of socialist Poland, it left the country vulnerable to global economic fluctuations and western undermining, and the repercussions in the form of massive debt is still felt in Poland even today. This Golden Age came to an end after the

In 1970, Gomuإ‚ka's government had decided to adopt massive increases in the prices of basic goods, including food. The resulting widespread violent protests in December that same year resulted in a number of deaths. They also forced another major change in the government, as Gomuإ‚ka was replaced by Edward Gierek as the new First Secretary. Gierek's plan for recovery was centered on massive borrowing, mainly from the United States and West Germany, to re-equip and modernize Polish industry, and to import consumer goods to give the workers some incentive to work. While it boosted the Polish economy, and is still remembered as the "Golden Age" of socialist Poland, it left the country vulnerable to global economic fluctuations and western undermining, and the repercussions in the form of massive debt is still felt in Poland even today. This Golden Age came to an end after the  On 16 October 1978, the Archbishop of Krakأ³w,

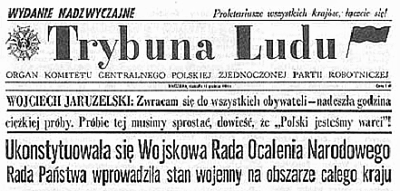

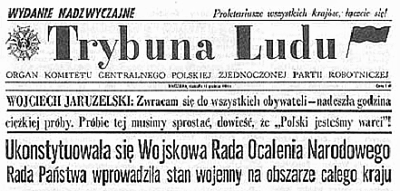

On 16 October 1978, the Archbishop of Krakأ³w,  On 13 December 1981, Jaruzelski proclaimed martial law, suspended Solidarity, and temporarily imprisoned most of its leaders. This sudden crackdown on Solidarity was reportedly out of fear of Soviet intervention (see

On 13 December 1981, Jaruzelski proclaimed martial law, suspended Solidarity, and temporarily imprisoned most of its leaders. This sudden crackdown on Solidarity was reportedly out of fear of Soviet intervention (see

The government and politics of the Polish People's Republic were governed by the Polish United Workers' Party (''Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR''). Despite the presence of two minor parties, the United People's Party and the

The government and politics of the Polish People's Republic were governed by the Polish United Workers' Party (''Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR''). Despite the presence of two minor parties, the United People's Party and the

During its existence, the Polish People's Republic maintained relations not only with the Soviet Union, but several communist states around the world. It also had friendly relations with the United States, United Kingdom, France, and the Western Bloc as well as the People's Republic of China. At the height of the

During its existence, the Polish People's Republic maintained relations not only with the Soviet Union, but several communist states around the world. It also had friendly relations with the United States, United Kingdom, France, and the Western Bloc as well as the People's Republic of China. At the height of the

Poland suffered tremendous economic losses during World War II. In 1939, Poland had 35.1 million inhabitants, but the census of 14 February 1946 showed only 23.9 million inhabitants. The difference was partially the result of the border revision. Losses in national resources and infrastructure amounted to approximately 38%. The implementation of the immense tasks involved with the reconstruction of the country was intertwined with the struggle of the new government for the stabilisation of power, made even more difficult by the fact that a considerable part of society was mistrustful of the communist government. The occupation of Poland by the Red Army and the support the Soviet Union had shown for the Polish communists was decisive in the communists gaining the upper hand in the new Polish government.

As control of the Polish territories passed from occupying forces of Nazi Germany to the subsequent occupying forces of the Soviet Union, and from the Soviet Union to the Soviet-imposed puppet satellite government, Poland's new

Poland suffered tremendous economic losses during World War II. In 1939, Poland had 35.1 million inhabitants, but the census of 14 February 1946 showed only 23.9 million inhabitants. The difference was partially the result of the border revision. Losses in national resources and infrastructure amounted to approximately 38%. The implementation of the immense tasks involved with the reconstruction of the country was intertwined with the struggle of the new government for the stabilisation of power, made even more difficult by the fact that a considerable part of society was mistrustful of the communist government. The occupation of Poland by the Red Army and the support the Soviet Union had shown for the Polish communists was decisive in the communists gaining the upper hand in the new Polish government.

As control of the Polish territories passed from occupying forces of Nazi Germany to the subsequent occupying forces of the Soviet Union, and from the Soviet Union to the Soviet-imposed puppet satellite government, Poland's new

Reforma Rolna

Encyklopedia.PWN.pl (Internet Archive)

Nacjonalizacja w Polsce

Encyklopedia.PWN.pl (Internet Archive) The Allied punishment of Germany for the war of destruction was intended to include large-scale reparations to Poland. However, those were truncated into insignificance by the break-up of Germany into East and West and the onset of the Cold War. Poland was then relegated to receive her share from the Soviet-controlled East Germany. However, even this was attenuated, as the Soviets pressured the Polish Government to cease receiving the reparations far ahead of schedule as a sign of 'friendship' between the two new communist neighbors and, therefore, now friends. Thus, without the reparations and without the massive Marshall Plan implemented in the West at that time, Poland's postwar recovery was much harder than it could have been.

During the Gierek era, Poland borrowed large sums from Western creditors in exchange for promise of social and economic reforms. None of these have been delivered due to resistance from the hardline communist leadership as any true reforms would require effectively abandoning the Marxian economy with central planning, state-owned enterprises and state-controlled prices and trade. After the West refused to grant Poland further loans, the living standards began to sharply fall again as the supply of imported goods dried up, and as Poland was forced to export everything it could, particularly food and coal, to service its massive debt, which would reach US$23 billion by 1980.

In 1981, Poland notified

During the Gierek era, Poland borrowed large sums from Western creditors in exchange for promise of social and economic reforms. None of these have been delivered due to resistance from the hardline communist leadership as any true reforms would require effectively abandoning the Marxian economy with central planning, state-owned enterprises and state-controlled prices and trade. After the West refused to grant Poland further loans, the living standards began to sharply fall again as the supply of imported goods dried up, and as Poland was forced to export everything it could, particularly food and coal, to service its massive debt, which would reach US$23 billion by 1980.

In 1981, Poland notified  In response to this situation, the government, which controlled all official foreign trade, continued to maintain a highly artificial

In response to this situation, the government, which controlled all official foreign trade, continued to maintain a highly artificial  In this desperate situation, all development and growth in the Polish economy slowed to a crawl. Most visibly, work on most of the major investment projects that had begun in the 1970s was stopped. As a result, most Polish cities acquired at least one infamous example of a large unfinished building languishing in a state of limbo. While some of these were eventually finished decades later, most, such as the

In this desperate situation, all development and growth in the Polish economy slowed to a crawl. Most visibly, work on most of the major investment projects that had begun in the 1970s was stopped. As a result, most Polish cities acquired at least one infamous example of a large unfinished building languishing in a state of limbo. While some of these were eventually finished decades later, most, such as the  After several years of the situation continuing to worsen, during which time the socialist government unsuccessfully tried various expedients to improve the performance of the economy—at one point resorting to placing military

After several years of the situation continuing to worsen, during which time the socialist government unsuccessfully tried various expedients to improve the performance of the economy—at one point resorting to placing military

Being produced in a then-socialist country, the shows did contain a socialist agenda, but with a more informal and comical tone; they concentrated on everyday life which was appealing to ordinary people. These include '' Czterdziestolatek'' (1975–1978), '' Alternatywy 4'' (1986–1987) and '' Zmiennicy'' (1987–1988). The wide range of topics covered featured petty disputes in the block of flats, work issues, human behaviour and interaction as well as comedy, sarcasm, drama and satire. Every televised show was censored if necessary and political content was erased. Ridiculing the communist government was illegal, though Poland remained the most liberal of the

Being produced in a then-socialist country, the shows did contain a socialist agenda, but with a more informal and comical tone; they concentrated on everyday life which was appealing to ordinary people. These include '' Czterdziestolatek'' (1975–1978), '' Alternatywy 4'' (1986–1987) and '' Zmiennicy'' (1987–1988). The wide range of topics covered featured petty disputes in the block of flats, work issues, human behaviour and interaction as well as comedy, sarcasm, drama and satire. Every televised show was censored if necessary and political content was erased. Ridiculing the communist government was illegal, though Poland remained the most liberal of the

The change in political climate in the 1950s gave rise to the

The change in political climate in the 1950s gave rise to the  ;Movies

*''

;Movies

*''

The architecture in Poland under the Polish People's Republic had three major phases – short-lived socialist realism, modernism and functionalism. Each of these styles or trends was either imposed by the government or communist doctrine.

Under

The architecture in Poland under the Polish People's Republic had three major phases – short-lived socialist realism, modernism and functionalism. Each of these styles or trends was either imposed by the government or communist doctrine.

Under  Following the Polish October in 1956, the concept of socialist realism was condemned. It was then that modernist architecture was promoted globally, with simplistic designs made of glass, steel and concrete. Due to previous extravagances, the idea of functionalism (serving for a purpose) was encouraged by Wإ‚adysإ‚aw Gomuإ‚ka.

Following the Polish October in 1956, the concept of socialist realism was condemned. It was then that modernist architecture was promoted globally, with simplistic designs made of glass, steel and concrete. Due to previous extravagances, the idea of functionalism (serving for a purpose) was encouraged by Wإ‚adysإ‚aw Gomuإ‚ka.

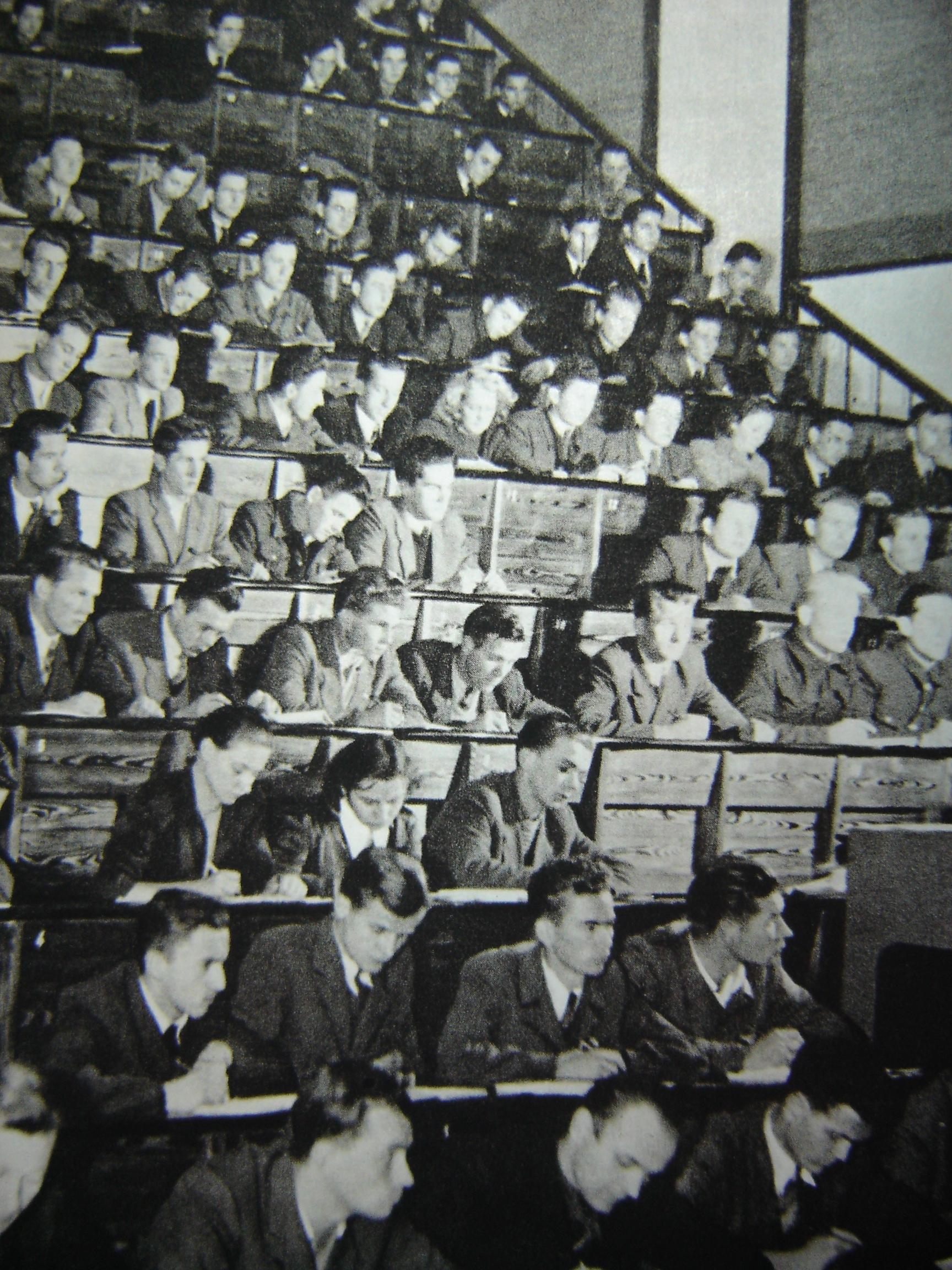

Communist authorities placed an emphasis on education since they considered it vital to create a new

Communist authorities placed an emphasis on education since they considered it vital to create a new

The experiences in and after World War II, wherein the large ethnic Polish population was decimated, its Jewish minority was annihilated by the Germans, the large German minority was forcibly expelled from the country at the end of the war, along with the loss of the eastern territories which had a significant population of Eastern Orthodox Belarusians and Ukrainians, led to Poland becoming more homogeneously Catholic than it had been.

The Polish anti-religious campaign was initiated by the communist government in Poland which, under the doctrine of Marxism, actively advocated for the disenfranchisement of religion and planned atheisation.Zdzislawa Walaszek. An Open Issue of Legitimacy: The State and the Church in Poland. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 483, Religion and the State: The Struggle for Legitimacy and Power (January 1986), pp. 118–134 The Catholic Church, as the religion of most

The experiences in and after World War II, wherein the large ethnic Polish population was decimated, its Jewish minority was annihilated by the Germans, the large German minority was forcibly expelled from the country at the end of the war, along with the loss of the eastern territories which had a significant population of Eastern Orthodox Belarusians and Ukrainians, led to Poland becoming more homogeneously Catholic than it had been.

The Polish anti-religious campaign was initiated by the communist government in Poland which, under the doctrine of Marxism, actively advocated for the disenfranchisement of religion and planned atheisation.Zdzislawa Walaszek. An Open Issue of Legitimacy: The State and the Church in Poland. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 483, Religion and the State: The Struggle for Legitimacy and Power (January 1986), pp. 118–134 The Catholic Church, as the religion of most

Before World War II, a third of Poland's population was composed of ethnic minorities. After the war, however, Poland's minorities were mostly gone, due to the 1945 revision of borders, and the Holocaust. Under the

Before World War II, a third of Poland's population was composed of ethnic minorities. After the war, however, Poland's minorities were mostly gone, due to the 1945 revision of borders, and the Holocaust. Under the  The population of Jews in Poland, which formed the largest Jewish community in pre-war Europe at about 3.3 million people, was all but destroyed by 1945. Approximately 3 million Jews died of starvation in ghettos and

The population of Jews in Poland, which formed the largest Jewish community in pre-war Europe at about 3.3 million people, was all but destroyed by 1945. Approximately 3 million Jews died of starvation in ghettos and

, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, ''The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe'', Yale University Press, 2005 According to the national census, which took place on 14 February 1946, population of Poland was 23.9 million, out of which 32% lived in cities and towns, and 68% lived in the countryside. The 1950 census (3 December 1950) showed the population rise to 25 million, and the 1960 census (6 December 1960) placed the population of Poland at 29.7 million. tatistical Yearbook of Poland, Warsaw, 1965/ref> In 1950, Warsaw was again the biggest city, with the population of 804,000 inhabitants. Second was إپأ³dإ؛ (pop. 620,000), then Krakأ³w (pop. 344,000), Poznaإ„ (pop. 321,000), and Wrocإ‚aw (pop. 309,000). Females were in the majority in the country. In 1931, there were 105.6 women for 100 men. In 1946, the difference grew to 118.5/100, but in subsequent years, number of males grew, and in 1960, the ratio was 106.7/100. Most Germans were expelled from Poland and the annexed east German territories at the end of the war, while many Ukrainians, Rusyns and

The Polish People's Army (LWP) was initially formed during World War II as the Polish 1st Tadeusz Koإ›ciuszko Infantry Division, but more commonly known as the

The Polish People's Army (LWP) was initially formed during World War II as the Polish 1st Tadeusz Koإ›ciuszko Infantry Division, but more commonly known as the

Geographically, the Polish People's Republic bordered the Baltic Sea to the North; the Soviet Union (via the Russian SFSR ( Kaliningrad Oblast),

Geographically, the Polish People's Republic bordered the Baltic Sea to the North; the Soviet Union (via the Russian SFSR ( Kaliningrad Oblast),

PRL

at Czas-PRL.pl

Internetowe Muzeum Polski Ludowej

at PolskaLudowa.com

Muzeum PRL

at MuzeumPRL.com

at Komunizm.eu

Propaganda komunistyczna

PRL Tube, a categorized collection of videos from the Polish Communist period

{{DEFAULTSORT:Poland, People's Republic Of Eastern Bloc Former socialist republics Communist states Communism in Poland Soviet satellite states 1947 establishments in Poland 1989 disestablishments in Poland States and territories established in 1947 States and territories disestablished in 1989

Rzeczpospolita

() is the official name of Poland and a traditional name for some of its predecessor states. It is a compound of "thing, matter" and "common", a calque of Latin ''rأ©s pأ؛blica'' ( "thing" + "public, common"), i.e. ''republic'', in Engli ...

Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

. With a population of approximately 37.9 million near the end of its existence, it was the second-most populous communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

and Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

country in Europe. It was also one of the main signatories of the Warsaw Pact alliance. The largest city and official capital since 1947 was Warsaw, followed by the industrial city of إپأ³dإ؛ and cultural city of Krakأ³w. The country was bordered by the Baltic Sea to the north, the Soviet Union to the east, Czechoslovakia to the south, and East Germany to the west.

The Polish People's Republic was a socialist one-party state, with a unitary

Unitary may refer to:

Mathematics

* Unitary divisor

* Unitary element

* Unitary group

* Unitary matrix

* Unitary morphism

* Unitary operator

* Unitary transformation

* Unitary representation

* Unitarity (physics)

* ''E''-unitary inverse semigroup ...

Marxist–Leninist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialect ...

government headed by the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR). The country's official name was the "Republic of Poland" (') between 1947 and 1952 in accordance with the transitional Small Constitution of 1947

The Small Constitution of 1947 ( pl, Maإ‚a Konstytucja z 1947) was a temporary constitution issued by the communist-dominated Sejm (Polish parliament) on 19 February 1947. It confirmed the practice of separation of powers and strengthened the Sejm ...

. The name "People's Republic" was introduced and defined by the Constitution of 1952. Like other Eastern Bloc countries ( East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Albania), Poland was regarded as a satellite state in the Soviet sphere of interest, but it was never a constituent republic of the Soviet Union.Rao, B. V. (2006), ''History of Modern Europe Ad 1789–2002: A.D. 1789–2002'', Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Despite this, some major achievements were established during the period of the Polish People's Republic, such as improved living conditions, rapid industrialization, urbanization, access to universal health care, and free education. The Polish People's Republic also implemented policies that eliminated homelessness

Homelessness or houselessness – also known as a state of being unhoused or unsheltered – is the condition of lacking stable, safe, and adequate housing. People can be categorized as homeless if they are:

* living on the streets, also kn ...

and established a job guarantee

A job guarantee is an economic policy proposal that aims to provide a sustainable solution to inflation and unemployment. Its aim is to create full employment and price stability by having the state promise to hire unemployed workers as an emplo ...

. As a result Poland's population almost doubled between 1947 and 1989.

The Polish People's Republic maintained a large standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or n ...

. It also hosted Soviet troops in its territory.Rao, B. V. (2006), ''History of Modern Europe Ad 1789–2002: A.D. 1789–2002'', Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. Its chief intelligence agencies was the UB, which was succeeded by the SB. The official police organization, Citizens' Militia (MO), was also responsible for peacekeeping.

History

1945–1956

In the summer of 1944 the Polish Committee of National Liberation was established by Soviet-backed Polish communists to control territory retaken from Nazi Germany. On 1 January 1945 the committee was replaced by the

In the summer of 1944 the Polish Committee of National Liberation was established by Soviet-backed Polish communists to control territory retaken from Nazi Germany. On 1 January 1945 the committee was replaced by the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland

The Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Rzؤ…d Tymczasowy Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, RTRP) was created by the State National Council () on the night of 31 December 1944. Davies, Norman, 1982 and several reprints. ''God's Playgr ...

, all the key posts of which were held by members of the communist Polish Workers' Party.

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Stalin was able to present his western allies, Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, with a ''fait accompli

Many words in the English vocabulary are of French origin, most coming from the Anglo-Norman spoken by the upper classes in England for several hundred years after the Norman Conquest, before the language settled into what became Modern Engli ...

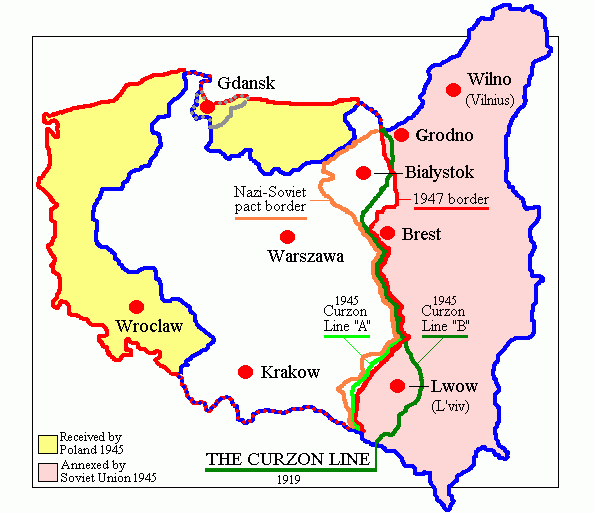

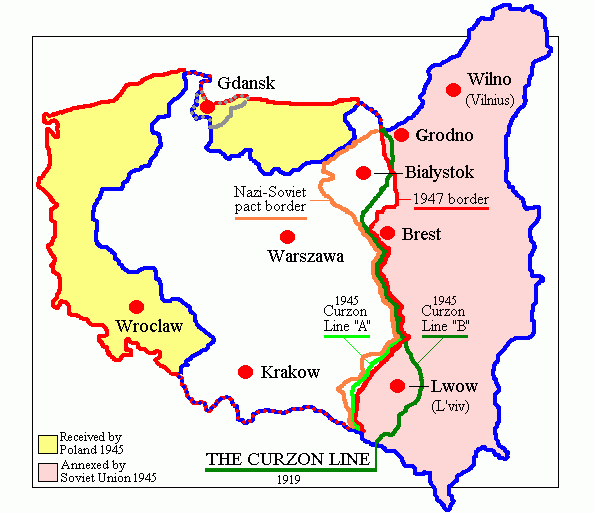

'' in Poland. His armed forces were in occupation of the country, and the communists were in control of its administration. The Soviet Union was in the process of reincorporating the lands to the east of the Curzon Line, which it had invaded and occupied between 1939 and 1941.

In compensation, Poland was granted German-populated territories in Pomerania, Silesia, and Brandenburg east of the Oder–Neisse line, including the southern half of East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreiأںen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytإ³ Prإ«sija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

. These were confirmed, pending a final peace conference with Germany, at the Tripartite Conference of Berlin, otherwise known as the Potsdam Conference in August 1945 after the end of the war in Europe. The Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement (german: Potsdamer Abkommen) was the agreement between three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union on 1 August 1945. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned th ...

also sanctioned the transfer of German population out of the acquired territories. Stalin was determined that Poland's new communist government would become his tool towards making Poland a satellite state like other countries in Central and Eastern Europe. He had severed relations with the Polish government-in-exile in London in 1943, but to appease Roosevelt and Churchill he agreed at Yalta that a coalition government would be formed. The Provisional Government of National Unity was established in June 1946 with the communists holding a majority of key posts, and with Soviet support they soon gained almost total control of the country.

In June 1946, the "Three Times Yes

The people's referendum ( pl, referendum ludowe) of 1946, also known as the Three Times Yes referendum (''Trzy razy tak'', often abbreviated as 3أ—TAK), was a referendum held in Poland on 30 June 1946 on the authority of the State National Council ...

" referendum was held on a number of issues—abolition of the Senate of Poland, land reform, and making the Oder–Neisse line Poland's western border. The communist-controlled Interior Ministry issued results showing that all three questions passed overwhelmingly. Years later, however, evidence was uncovered showing that the referendum had been tainted by large-scale fraud, and only the third question actually passed. Wإ‚adysإ‚aw Gomuإ‚ka then took advantage of a split in the Polish Socialist Party. One faction, which included Prime Minister Edward Osأ³bka-Morawski, wanted to join forces with the Peasant Party and form a united front against the communists. Another faction, led by Jأ³zef Cyrankiewicz, argued that the socialists should support the communists in carrying through a socialist program while opposing the imposition of one-party rule. Pre-war political hostilities continued to influence events, and Stanisإ‚aw Mikoإ‚ajczyk would not agree to form a united front with the socialists. The communists played on these divisions by dismissing Osأ³bka-Morawski and making Cyrankiewicz Prime Minister.

Between the referendum and the January 1947 general elections, the opposition was subjected to persecution. Only the candidates of the pro-government "Democratic Bloc" (the PPR, Cyrankiewicz' faction of the PPS, and the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

) were allowed to campaign completely unmolested. Meanwhile, several opposition candidates were prevented from campaigning at all. Mikoإ‚ajczyk's Polish People's Party (PSL) in particular suffered persecution; it had opposed the abolition of the Senate as a test of strength against the government. Although it supported the other two questions, the Communist-dominated government branded the PSL "traitors". This massive oppression was overseen by Gomuإ‚ka and the provisional president, Bolesإ‚aw Bierut.

The official results of the election showed the Democratic Bloc with 80.1 percent of the vote. The Democratic Bloc was awarded 394 seats to only 28 for the PSL. Mikoإ‚ajczyk immediately resigned to protest this so-called 'implausible result' and fled to the United Kingdom in April rather than face arrest. Later, some historians announced that the official results were only obtained through massive fraud. Government officials didn't even count the real votes in many areas and simply filled in the relevant documents in accordance with instructions from the communists. In other areas, the ballot boxes were either destroyed or replaced with boxes containing prefilled ballots.

The 1947 election marked the beginning of undisguised communist rule in Poland, though it was not officially transformed into the Polish People's Republic until the adoption of the 1952 Constitution. However, Gomuإ‚ka never supported Stalin's control over the Polish communists and was soon replaced as party leader by the more pliable Bierut. In 1948, the communists consolidated their power, merging with Cyrankiewicz' faction of the PPS to form the Polish United Workers' Party (known in Poland as 'the Party'), which would monopolise political power in Poland until 1989. In 1949, Polish-born Soviet Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky became the Minister of National Defence, with the additional title Marshal of Poland, and in 1952 he became Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers (deputy premier).

Over the coming years, private industry was

The official results of the election showed the Democratic Bloc with 80.1 percent of the vote. The Democratic Bloc was awarded 394 seats to only 28 for the PSL. Mikoإ‚ajczyk immediately resigned to protest this so-called 'implausible result' and fled to the United Kingdom in April rather than face arrest. Later, some historians announced that the official results were only obtained through massive fraud. Government officials didn't even count the real votes in many areas and simply filled in the relevant documents in accordance with instructions from the communists. In other areas, the ballot boxes were either destroyed or replaced with boxes containing prefilled ballots.

The 1947 election marked the beginning of undisguised communist rule in Poland, though it was not officially transformed into the Polish People's Republic until the adoption of the 1952 Constitution. However, Gomuإ‚ka never supported Stalin's control over the Polish communists and was soon replaced as party leader by the more pliable Bierut. In 1948, the communists consolidated their power, merging with Cyrankiewicz' faction of the PPS to form the Polish United Workers' Party (known in Poland as 'the Party'), which would monopolise political power in Poland until 1989. In 1949, Polish-born Soviet Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky became the Minister of National Defence, with the additional title Marshal of Poland, and in 1952 he became Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers (deputy premier).

Over the coming years, private industry was nationalised

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

, the land seized from the pre-war landowners and redistributed to the lower-class farmers, and millions of Poles were transferred from the lost eastern territories to the lands acquired from Germany. Poland was now to be brought into line with the Soviet model of a "people's democracy" and a centrally planned socialist economy. The government also embarked on the collectivisation of agriculture, although the pace was slower than in other satellites: Poland remained the only Eastern Bloc country where individual farmers dominated agriculture.

Through a careful balance of agreement, compromise and resistance — and having signed an agreement of coexistence with the communist regime — cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

primate Stefan Wyszyإ„ski maintained and even strengthened the Polish church through a series of failed government leaders. He was put under house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if all ...

from 1953 to 1956 for failing to punish priests who participated in anti-government activity.Britannica (10 April 2013)Stefan Wyszyإ„ski, (1901–1981).

Encyclopأ¦dia Britannica. Bierut died in March 1956, and was replaced with Edward Ochab, who held the position for seven months. In June, workers in the industrial city of Poznaإ„ went on strike, in what became known as

1956 Poznaإ„ protests

The 1956 Poznaإ„ protests, also known as Poznaإ„ June ( pl, Poznaإ„ski Czerwiec), were the first of several massive protests against the communist government of the Polish People's Republic. Demonstrations by workers demanding better working con ...

. Voices began to be raised in the Party and among the intellectuals calling for wider reforms of the Stalinist system. Eventually, power shifted towards Gomuإ‚ka, who replaced Ochab as party leader. Hardline Stalinists were removed from power and many Soviet officers serving in the Polish Army were dismissed. This marked the end of the Stalinist era.

1970s and 1980s

In 1970, Gomuإ‚ka's government had decided to adopt massive increases in the prices of basic goods, including food. The resulting widespread violent protests in December that same year resulted in a number of deaths. They also forced another major change in the government, as Gomuإ‚ka was replaced by Edward Gierek as the new First Secretary. Gierek's plan for recovery was centered on massive borrowing, mainly from the United States and West Germany, to re-equip and modernize Polish industry, and to import consumer goods to give the workers some incentive to work. While it boosted the Polish economy, and is still remembered as the "Golden Age" of socialist Poland, it left the country vulnerable to global economic fluctuations and western undermining, and the repercussions in the form of massive debt is still felt in Poland even today. This Golden Age came to an end after the

In 1970, Gomuإ‚ka's government had decided to adopt massive increases in the prices of basic goods, including food. The resulting widespread violent protests in December that same year resulted in a number of deaths. They also forced another major change in the government, as Gomuإ‚ka was replaced by Edward Gierek as the new First Secretary. Gierek's plan for recovery was centered on massive borrowing, mainly from the United States and West Germany, to re-equip and modernize Polish industry, and to import consumer goods to give the workers some incentive to work. While it boosted the Polish economy, and is still remembered as the "Golden Age" of socialist Poland, it left the country vulnerable to global economic fluctuations and western undermining, and the repercussions in the form of massive debt is still felt in Poland even today. This Golden Age came to an end after the 1973 energy crisis

The 1973 oil crisis or first oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by Saudi Arabia, proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations that had supp ...

. The failure of the Gierek government, both economically and politically, soon led to the creation of opposition in the form of trade unions, student groups, clandestine newspapers and publishers, imported books and newspapers, and even a "flying university."

On 16 October 1978, the Archbishop of Krakأ³w,

On 16 October 1978, the Archbishop of Krakأ³w, Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

Karol Wojtyإ‚a, was elected Pope, taking the name John Paul II. The election of a Polish Pope had an electrifying effect on what had been, even under communist rule, one of the most devoutly Catholic nations in Europe. Gierek is alleged to have said to his cabinet, "O God, what are we going to do now?" or, as occasionally reported, "Jesus and Mary, this is the end". When John Paul II made his first papal tour of Poland in June 1979, half a million people heard him speak in Warsaw; he did not call for rebellion, but instead encouraged the creation of an "alternative Poland" of social institutions independent of the government, so that when the next economic crisis came, the nation would present a united front.

A new wave of labour strikes undermined Gierek's government, and in September Gierek, who was in poor health, was finally removed from office and replaced as Party leader by Stanisإ‚aw Kania

Stanisإ‚aw Kania (; 8 March 1927 – 3 March 2020) was a Polish communist politician.

Life and career

Kania joined the Polish Workers' Party in April 1945 when the Germans were driven out by the Red Army and Polish Communists began to take contr ...

. However, Kania was unable to find an answer for the fast-eroding support of communism in Poland. Labour turmoil led to the formation of the independent trade union Solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictio ...

(''Solidarnoإ›ؤ‡'') in September 1980, originally led by Lech Waإ‚ؤ™sa. In fact, Solidarity became a broad anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

social movement ranging from people associated with the Catholic Church, to members of the anti-Stalinist left. By the end of 1981, Solidarity had nine million members—a quarter of Poland's population and three times as many as the PUWP had. Kania resigned under Soviet pressure in October and was succeeded by Wojciech Jaruzelski, who had been Defence minister since 1968 and Premier since February.

On 13 December 1981, Jaruzelski proclaimed martial law, suspended Solidarity, and temporarily imprisoned most of its leaders. This sudden crackdown on Solidarity was reportedly out of fear of Soviet intervention (see

On 13 December 1981, Jaruzelski proclaimed martial law, suspended Solidarity, and temporarily imprisoned most of its leaders. This sudden crackdown on Solidarity was reportedly out of fear of Soviet intervention (see Soviet reaction to the Polish crisis of 1980–1981

The Polish crisis of 1980–1981, associated with the emergence of the Solidarity mass movement in the Polish People's Republic, challenged the rule of the Polish United Workers' Party and Poland's alignment with the Soviet Union.

For the first t ...

). The government then disallowed Solidarity on 8 October 1982. Martial law was formally lifted in July 1983, though many heightened controls on civil liberties and political life, as well as food rationing, remained in place through the mid-to-late-1980s. Jaruzelski stepped down as prime minister in 1985 and became president (chairman of the Council of State).

This did not prevent Solidarity from gaining more support and power. Eventually it eroded the dominance of the PUWP, which in 1981 lost approximately 85,000 of its 3 million members. Throughout the mid-1980s, Solidarity persisted solely as an underground organization, but by the late 1980s was sufficiently strong to frustrate Jaruzelski's attempts at reform, and nationwide strikes in 1988 were one of the factors that forced the government to open a dialogue with Solidarity.

From 6 February to 15 April 1989, talks of 13 working groups in 94 sessions, which became known as the " Roundtable Talks" (''Rozmowy Okrؤ…gإ‚ego Stoإ‚u'') saw the PUWP abandon power and radically altered the shape of the country. In June, shortly after the Tiananmen Square protests

The Tiananmen Square protests, known in Chinese as the June Fourth Incident (), were student-led demonstrations held in Tiananmen Square, Beijing during 1989. In what is known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre, or in Chinese the June Fourth ...

in China, the 1989 Polish legislative election

Parliamentary elections were held in Poland in 1989 to elect members of the Sejm and the recreated Senate. The first round took place on 4 June, with a second round on 18 June. They were the first elections in the country since the Communist Polis ...

took place. Much to its own surprise, Solidarity took all contested (35%) seats in the Sejm, the Parliament's lower house, and all but one seat in the elected Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

.

Solidarity persuaded the communists' longtime allied parties, the United People's Party and Democratic Party, to throw their support to Solidarity. This all but forced Jaruzelski, who had been named president in July, to appoint a Solidarity member as prime minister. Finally, he appointed a Solidarity-led coalition government with Tadeusz Mazowiecki as the country's first non-communist prime minister since 1948.

On 10 December 1989, the statue

A statue is a free-standing sculpture in which the realistic, full-length figures of persons or animals are carved or cast in a durable material such as wood, metal or stone. Typical statues are life-sized or close to life-size; a sculpture t ...

of Vladimir Lenin was removed in Warsaw by the PRL authorities.

The Parliament amended the Constitution on 29 December 1989 to formally rescind the PUWP's constitutionally-guaranteed power and restore democracy and civil liberties. This began the Third Polish Republic

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1âپ„60 of a ''second'', or 1âپ„3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* Hig ...

, and served as a prelude to the democratic elections of 1991

File:1991 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Boris Yeltsin, elected as Russia's first president, waves the new flag of Russia after the 1991 Soviet coup d'أ©tat attempt, orchestrated by Soviet hardliners; Mount Pinatubo erupts in the Phil ...

— the fourth ever held in Poland.

The PZPR was disbanded on 30 January 1990, but Waإ‚ؤ™sa could be elected as president only eleven months later. The Warsaw Pact was dissolved on 1 July 1991 and the Soviet Union ceased to exist in December 1991. On 27 October 1991, the 1991 Polish parliamentary election

Parliamentary elections were held in Poland on 27 October 1991 to elect deputies to both houses of the National Assembly.Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stأ¶ver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p1491 The 1991 election was notable on severa ...

, the first democratic election since the 1920s. This completed Poland's transition from a communist party rule to a Western-style liberal democratic political system. The last post-Soviet troops left Poland on 18 September 1993. After ten years of democratic consolidation, Poland joined OECD in 1996, NATO in 1999 and the European Union in 2004.

Government and politics

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

, the country was generally reckoned by western nations as a ''de facto'' one-party state because these two parties were supposedly completely subservient to the Communists and had to accept the PZPR's "leading role" as a condition of their existence. It was politically influenced by the Soviet Union to the extent of being its satellite country, along with East Germany, Czechoslovakia and other Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

members.

From 1952, the highest law was the Constitution of the Polish People's Republic, and the Polish Council of State replaced the presidency of Poland. Elections were held on the single lists of the Front of National Unity. Despite these changes, Poland was one of the most liberal communist nations and was the only communist country in the world which did not have any communist symbols (red star

A red star, five-pointed and filled, is a symbol that has often historically been associated with communist ideology, particularly in combination with the hammer and sickle, but is also used as a purely socialist symbol in the 21st century. I ...

, stars, ears of wheat, or hammer and sickle

The hammer and sickle (Unicode: "âک") zh, s=锤هگه’Œé•°هˆ€, p=Chuأzi hأ© liأ،ndؤپo or zh, s=é•°هˆ€é”¤هگ, p=Liأ،ndؤپo chuأzi, labels=no is a symbol meant to represent proletarian solidarity, a union between agricultural and industri ...

) on its flag

A flag is a piece of fabric (most often rectangular or quadrilateral) with a distinctive design and colours. It is used as a symbol, a signalling device, or for decoration. The term ''flag'' is also used to refer to the graphic design empl ...

and coat of arms. The White Eagle White Eagle(s) may refer to:

History and politics

* Coat of arms of Poland, a white eagle

* Crusade of Romanianism, or White Eagles, a 1930s far-right movement in Romania

* Task Force White Eagle, a Polish military unit during the War in Afghanist ...

founded by Polish monarchs in the Middle Ages remained as Poland's national emblem; the only feature removed by the communists from the pre-war design was the crown, which was seen as imperialistic and monarchist.

The Polish People's Republic maintained a large standing army and hosted Soviet troops in its territory, as Poland was a Warsaw Pact signatory.Rao, B. V. (2006), ''History of Modern Europe Ad 1789–2002: A.D. 1789–2002'', Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. The UB and succeeding SB were the chief intelligence agencies that acted as secret police. The official police organization, which was also responsible for peacekeeping and suppression of protests, was renamed Citizens' Militia (MO). The Militia's elite ZOMO squads committed various serious crimes to maintain the communists in power, including the harsh treatment of protesters, arrest of opposition leaders and in some cases, murder. According to Rudolph J. Rummel, at least 22,000 people killed by the regime during its rule. As a result, Poland had a high imprisonment rate but one of the lowest crime rates in the world.

Foreign relations

During its existence, the Polish People's Republic maintained relations not only with the Soviet Union, but several communist states around the world. It also had friendly relations with the United States, United Kingdom, France, and the Western Bloc as well as the People's Republic of China. At the height of the

During its existence, the Polish People's Republic maintained relations not only with the Soviet Union, but several communist states around the world. It also had friendly relations with the United States, United Kingdom, France, and the Western Bloc as well as the People's Republic of China. At the height of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, Poland attempted to remain neutral to the conflict between the Soviets and the Americans. In particular, Edward Gierek sought to establish Poland as a mediator between the two powers in the 1970s. Both the U.S. presidents

The president of the United States is the head of state and head of government of the United States, indirectly elected to a four-year term

Term may refer to:

* Terminology, or term, a noun or compound word used in a specific context, in pa ...

and the Soviet general secretaries

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, Power (social and political), power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the orga ...

or leaders visited communist Poland.

Under pressure from the USSR, Poland participated in the invasion of Czechoslovakia

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia refers to the events of 20–21 August 1968, when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Rep ...

in 1968.

Poland's relations

Relation or relations may refer to:

General uses

*International relations, the study of interconnection of politics, economics, and law on a global level

*Interpersonal relationship, association or acquaintance between two or more people

*Public ...

with Israel were on a fair level following the aftermath of the Holocaust. In 1947, the PRL voted in favour of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, which led to Israel's recognition by the PRL on 19 May 1948. However, by the Six-Day War, it severed diplomatic relations with Israel in June 1967 and supported the Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, ظ…ظ†ط¸ظ…ط© ط§ظ„طھطط±ظٹط± ط§ظ„ظپظ„ط³ط·ظٹظ†ظٹط©, ') is a Palestinian nationalism, Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establ ...

which recognized the State of Palestine

Palestine ( ar, ظپظ„ط³ط·ظٹظ†, Filasل¹ؤ«n), Legal status of the State of Palestine, officially the State of Palestine ( ar, ط¯ظˆظ„ط© ظپظ„ط³ط·ظٹظ†, Dawlat Filasل¹ؤ«n, label=none), is a state (polity), state located in Western Asia. Officiall ...

on 14 December 1988. In 1989, PRL restored relations with Israel.

The PRL participated as a member of the UN, the World Trade Organization, the Warsaw Pact, Comecon, International Energy Agency

The International Energy Agency (IEA) is a Paris-based autonomous intergovernmental organisation, established in 1974, that provides policy recommendations, analysis and data on the entire global energy sector, with a recent focus on curbing carb ...

, Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; french: Conseil de l'Europe, ) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold European Convention on Human Rights, human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. ...

, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was established in 1957 ...

, and Interkosmos.

Economy

Early years

Poland suffered tremendous economic losses during World War II. In 1939, Poland had 35.1 million inhabitants, but the census of 14 February 1946 showed only 23.9 million inhabitants. The difference was partially the result of the border revision. Losses in national resources and infrastructure amounted to approximately 38%. The implementation of the immense tasks involved with the reconstruction of the country was intertwined with the struggle of the new government for the stabilisation of power, made even more difficult by the fact that a considerable part of society was mistrustful of the communist government. The occupation of Poland by the Red Army and the support the Soviet Union had shown for the Polish communists was decisive in the communists gaining the upper hand in the new Polish government.

As control of the Polish territories passed from occupying forces of Nazi Germany to the subsequent occupying forces of the Soviet Union, and from the Soviet Union to the Soviet-imposed puppet satellite government, Poland's new

Poland suffered tremendous economic losses during World War II. In 1939, Poland had 35.1 million inhabitants, but the census of 14 February 1946 showed only 23.9 million inhabitants. The difference was partially the result of the border revision. Losses in national resources and infrastructure amounted to approximately 38%. The implementation of the immense tasks involved with the reconstruction of the country was intertwined with the struggle of the new government for the stabilisation of power, made even more difficult by the fact that a considerable part of society was mistrustful of the communist government. The occupation of Poland by the Red Army and the support the Soviet Union had shown for the Polish communists was decisive in the communists gaining the upper hand in the new Polish government.

As control of the Polish territories passed from occupying forces of Nazi Germany to the subsequent occupying forces of the Soviet Union, and from the Soviet Union to the Soviet-imposed puppet satellite government, Poland's new economic system

An economic system, or economic order, is a system of Production (economics), production, resource allocation and Distribution (economics), distribution of goods and services within a society or a given geographic area. It includes the combinati ...

was forcibly imposed and began moving towards a radical, communist centrally planned economy. One of the first major steps in that direction involved the agricultural reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

issued by the Polish Committee of National Liberation government on 6 September 1944. All estates over 0.5 km2 in pre-war Polish territories and all over 1 km2 in former German territories were nationalised without compensation. In total, 31,000 km2 of land were nationalised in Poland and 5 million in the former German territories, out of which 12,000 km2 were redistributed to farmers and the rest remained in the hands of the government (Most of this was eventually used in the collectivization and creation of sovkhoz-like State Agricultural Farms "PGR"). However, the collectivization of Polish farming never reached the same extent as it did in the Soviet Union or other countries of the Eastern Bloc.Wojciech RoszkowskiReforma Rolna

Encyklopedia.PWN.pl (Internet Archive)

Nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

began in 1944, with the pro-Soviet government taking over industries in the newly acquired territories along with the rest of the country. As nationalization was unpopular, the communists delayed the nationalization reform until 1946, when after the 3xTAK

The people's referendum ( pl, referendum ludowe) of 1946, also known as the Three Times Yes referendum (''Trzy razy tak'', often abbreviated as 3أ—TAK), was a referendum held in Poland on 30 June 1946 on the authority of the State National Council ...

referendums they were fairly certain they had total control of the state and could deal a heavy blow to eventual public protests. Some semi-official nationalisation of various private enterprises had begun also in 1944. In 1946, all enterprises with over 50 employees were nationalised, with no compensation to Polish owners.Zbigniew LandauNacjonalizacja w Polsce

Encyklopedia.PWN.pl (Internet Archive) The Allied punishment of Germany for the war of destruction was intended to include large-scale reparations to Poland. However, those were truncated into insignificance by the break-up of Germany into East and West and the onset of the Cold War. Poland was then relegated to receive her share from the Soviet-controlled East Germany. However, even this was attenuated, as the Soviets pressured the Polish Government to cease receiving the reparations far ahead of schedule as a sign of 'friendship' between the two new communist neighbors and, therefore, now friends. Thus, without the reparations and without the massive Marshall Plan implemented in the West at that time, Poland's postwar recovery was much harder than it could have been.

Later years

During the Gierek era, Poland borrowed large sums from Western creditors in exchange for promise of social and economic reforms. None of these have been delivered due to resistance from the hardline communist leadership as any true reforms would require effectively abandoning the Marxian economy with central planning, state-owned enterprises and state-controlled prices and trade. After the West refused to grant Poland further loans, the living standards began to sharply fall again as the supply of imported goods dried up, and as Poland was forced to export everything it could, particularly food and coal, to service its massive debt, which would reach US$23 billion by 1980.

In 1981, Poland notified

During the Gierek era, Poland borrowed large sums from Western creditors in exchange for promise of social and economic reforms. None of these have been delivered due to resistance from the hardline communist leadership as any true reforms would require effectively abandoning the Marxian economy with central planning, state-owned enterprises and state-controlled prices and trade. After the West refused to grant Poland further loans, the living standards began to sharply fall again as the supply of imported goods dried up, and as Poland was forced to export everything it could, particularly food and coal, to service its massive debt, which would reach US$23 billion by 1980.

In 1981, Poland notified Club de Paris

The Paris Club (french: Club de Paris) is a group of officials from major creditor countries whose role is to find co-ordinated and sustainable solutions to the payment difficulties experienced by debtor countries. As debtor countries undertake ...

(a group of Western-European central banks) about its insolvency and a number of negotiations of repaying its foreign debt were completed between 1989 and 1991.

The party was forced to raise prices, which led to further large-scale social unrest and formation of the Solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictio ...

movement. During the Solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictio ...

years and the imposition of martial law, Poland entered a decade of economic crisis, officially acknowledged as such even by the regime. Rationing and queuing became a way of life, with ration cards (''Kartki'') necessary to buy even such basic consumer staples as milk and sugar. Access to Western luxury goods became even more restricted, as Western governments applied economic sanction

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they may ...

s to express their dissatisfaction with the government repression of the opposition, while at the same time the government had to use most of the foreign currency it could obtain to pay the crushing rates on its foreign debt.

In response to this situation, the government, which controlled all official foreign trade, continued to maintain a highly artificial

In response to this situation, the government, which controlled all official foreign trade, continued to maintain a highly artificial exchange rate

In finance, an exchange rate is the rate at which one currency will be exchanged for another currency. Currencies are most commonly national currencies, but may be sub-national as in the case of Hong Kong or supra-national as in the case of ...

with Western currencies. The exchange rate worsened distortions in the economy at all levels, resulting in a growing black market

A black market, underground economy, or shadow economy is a clandestine market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality or is characterized by noncompliance with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the se ...

and the development of a shortage economy. The only way for an individual to buy most Western goods was to use Western currencies, notably the U.S. dollar, which in effect became a parallel currency. However, it could not simply be exchanged at the official banks for zlotys, since the government exchange rate undervalued the dollar and placed heavy restrictions on the amount that could be exchanged, and so the only practical way to obtain it was from remittances

A remittance is a non-commercial transfer of money by a foreign worker, a member of a diaspora community, or a citizen with familial ties abroad, for household income in their home country or homeland. Money sent home by migrants competes with ...

or work outside the country. An entire illegal industry of street-corner money changers emerged as a result. The so-called ''Cinkciarze'' gave clients far better than official exchange rate and became wealthy from their opportunism albeit at the risk of punishment, usually diminished by the wide scale bribery of the Militia.

As Western currency came into the country from emigrant families and foreign workers, the government in turn attempted to gather it up by various means, most visibly by establishing a chain of state-run '' Pewex'' and ''Baltona'' stores in all Polish cities, where goods could only be bought with hard currency. It even introduced its own '' ersatz'' U.S. currency (''bony PeKaO'' in Polish). This paralleled the financial practices in East Germany running its own ration stamps at the same time. The trend led to an unhealthy state of affairs where the chief determinant of economic status was access to hard currency. This situation was incompatible with any remaining ideals of socialism, which were soon completely abandoned at the community level.

Szkieletor

Unity Tower, formerly known as the Skeletor ( pl, ) is a 102.5 metre high-rise building located in Krakأ³w, Poland. Unity Tower is located near the Mogilskie Roundabout (''Rondo Mogilskie'') and Cracow University of Economics. It is the tal ...

skyscraper

A skyscraper is a tall continuously habitable building having multiple floors. Modern sources currently define skyscrapers as being at least or in height, though there is no universally accepted definition. Skyscrapers are very tall high-ris ...

in Krakأ³w, were never finished at all, wasting the considerable resources devoted to their construction. Polish investment in economic infrastructure and technological development fell rapidly, ensuring that the country lost whatever ground it had gained relative to Western European economies in the 1970s. To escape the constant economic and political pressures during these years, and the general sense of hopelessness, many family income providers traveled for work in Western Europe, particularly West Germany (''Wyjazd na saksy''). During the era, hundreds of thousands of Poles left the country permanently and settled in the West, few of them returning to Poland even after the end of socialism in Poland. Tens of thousands of others went to work in countries that could offer them salaries in hard currency, notably Libya and Iraq.

After several years of the situation continuing to worsen, during which time the socialist government unsuccessfully tried various expedients to improve the performance of the economy—at one point resorting to placing military

After several years of the situation continuing to worsen, during which time the socialist government unsuccessfully tried various expedients to improve the performance of the economy—at one point resorting to placing military commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English transliteration of the Russian (''komissar''), which means 'commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the political commissars of Soviet and Eas ...

s to direct work in the factories — it grudgingly accepted pressures to liberalize the economy. The government introduced a series of small-scale reforms, such as allowing more small-scale private enterprises to function. However, the government also realized that it lacked the legitimacy to carry out any large-scale reforms, which would inevitably cause large-scale social dislocation and economic difficulties for most of the population, accustomed to the extensive social safety net that the socialist system had provided. For example, when the government proposed to close the Gdaإ„sk Shipyard

The Gdaإ„sk Shipyard ( pl, Stocznia Gdaإ„ska, formerly Lenin Shipyard) is a large Polish shipyard, located in the city of Gdaإ„sk. The yard gained international fame when Solidarity () was founded there in September 1980. It is situated on the w ...

, a decision in some ways justifiable from an economic point of view but also largely political, there was a wave of public outrage and the government was forced to back down.

The only way to carry out such changes without social upheaval would be to acquire at least some support from the opposition side. The government accepted the idea that some kind of a deal with the opposition would be necessary, and repeatedly attempted to find common ground throughout the 1980s. However, at this point the communists generally still believed that they should retain the reins of power for the near future, and only allowed the opposition limited, advisory participation in the running of the country. They believed that this would be essential to pacifying the Soviet Union, which they felt was not yet ready to accept a non-Communist Poland.

Culture

Television and media

The origins of Polish television date back to the late 1930s, however, the beginning of World War II interrupted further progress at establishing a regularly televised program. The first prime state television corporation, Telewizja Polska, was founded after the war in 1952 and was hailed as a great success by the communist authorities. The foundation date corresponds to the time of the very first regularly televised broadcast which occurred at 07:00 p.m CET on 25 October 1952. Initially, the auditions were broadcast to a limited number of viewers and at set dates, often a month apart. On 23 January 1953 regular shows began to appear on the first and only channel, TVP1. The second channel, TVP2, was launched in 1970 and coloured television was introduced in 1971. Most reliable sources of information in the 1950s were newspapers, most notably '' Trybuna Ludu'' (People's Tribune). The chief newscast under the Polish People's Republic for over 31 years was ''Dziennik Telewizyjny

''Dziennik Telewizyjny'' ( en, Television Journal; DT), commonly simplified to ''Dziennik'' (lit. Journal), was the chief news program of Telewizja Polska between 1958 and 1989, in the Polish People's Republic. It was Poland's second regularly te ...

'' (Television Journal). Commonly known to the viewers as ''Dziennik'', aired in the years 1958–1989 and was utilized by the Polish United Workers' Party as a propaganda tool to control the masses. Transmitted daily at 07:30 p.m CET since 1965, it was infamous for its manipulative techniques and emotive language as well as the controversial content. For instance, the ''Dziennik'' provided more information on world news, particularly bad events, war, corruption or scandals in the West. This method was intentionally used to minimize the effects of the issues that were occurring in communist Poland at the time. With its format, the show shared many similarities with the East German ''Aktuelle Kamera

Aktuelle Kamera (''"Current Camera")'' was the flagship television newscast of Deutscher Fernsehfunk, the state broadcaster of the German Democratic Republic (known as ''Fernsehen der DDR'' from 11 February 1972 to 11 March 1990). On air from 21 ...

''. Throughout the 1970s, ''Dziennik Telewizyjny'' was regularly watched by over 11 million viewers, approximately in every third household in the Polish People's Republic. The long legacy of communist television continues to this day; the older generation in contemporary Poland refers to every televised news program as "Dziennik" and the term also became synonymous with authoritarianism, propaganda, manipulation, lies, deception and disinformation.

Under martial law in Poland, from December 1981 ''Dziennik'' was presented by officers of the Polish Armed Forces or newsreaders in military uniforms and broadcast 24-hours a day. The running time has also been extended to 60 minutes. The program returned to its original form in 1983. The audience viewed this move as an attempt to militarize the country under a military junta. As a result, several newsreaders had difficulty in finding employment after the fall of communism in 1989.

Despite the political agenda of Telewizja Polska, the authorities did emphasize the need to provide entertainment for younger viewers without exposing the children to inappropriate content. Initially created in the 1950s, an evening cartoon block called ''Dobranocka'', which was targeted at young children, is still broadcast today under a different format. Among the most well-known animations of the 1970s and 1980s in Poland were '' Reksio'', '' Bolek and Lolek'', '' Krtek'' (Polish: Krecik) and '' The Moomins''.

Countless shows were made relating to Second World War history such as ''Four Tank-Men and a Dog

''Four Tank-Men and a Dog'' (Polish: ''Czterej pancerni i pies'', ) was a Polish black and white TV series based on the book by Janusz Przymanowski. Made between 1966 and 1970, the series is composed of 21 episodes of 55 minutes each, divided ...

'' (1966–1970) and '' Stakes Larger Than Life'' with Kapitan Kloss

Capitan and Kapitan are equivalents of the English Captain in other European languages.

Capitan, Capitano, and Kapitan may also refer to:

Places in the United States

* Capitan, Louisiana, an unincorporated community

*Capitan, New Mexico, a villa ...

(1967–1968), but were purely fictional and not based on real events. The horrors of war, Soviet invasion and the Holocaust were taboo topics, avoided and downplayed when possible. In most cases, producers and directors were encouraged to portray the Soviet Red Army as a friendly and victorious force which entirely liberated Poland from Nazism, Imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

or Capitalism. The goal was to strengthen the artificial Polish-Soviet friendship and eliminate any knowledge of the crimes or acts of terror committed by the Soviets during World War II, such as the Katyn massacre. Hence, the Polish audience were more lenient towards a TV series exclusively featuring Polish history from the times of the Kingdom of Poland or the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Being produced in a then-socialist country, the shows did contain a socialist agenda, but with a more informal and comical tone; they concentrated on everyday life which was appealing to ordinary people. These include '' Czterdziestolatek'' (1975–1978), '' Alternatywy 4'' (1986–1987) and '' Zmiennicy'' (1987–1988). The wide range of topics covered featured petty disputes in the block of flats, work issues, human behaviour and interaction as well as comedy, sarcasm, drama and satire. Every televised show was censored if necessary and political content was erased. Ridiculing the communist government was illegal, though Poland remained the most liberal of the

Being produced in a then-socialist country, the shows did contain a socialist agenda, but with a more informal and comical tone; they concentrated on everyday life which was appealing to ordinary people. These include '' Czterdziestolatek'' (1975–1978), '' Alternatywy 4'' (1986–1987) and '' Zmiennicy'' (1987–1988). The wide range of topics covered featured petty disputes in the block of flats, work issues, human behaviour and interaction as well as comedy, sarcasm, drama and satire. Every televised show was censored if necessary and political content was erased. Ridiculing the communist government was illegal, though Poland remained the most liberal of the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

members and censorship eventually lost its authority by the mid-1980s. The majority of the TV shows and serials made during the Polish People's Republic earned a cult

In modern English, ''cult'' is usually a pejorative term for a social group that is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or its common interest in a particular personality, object, or goal. This ...

status in Poland today, particularly due to their symbolism of a bygone era.

Cinema