phagocytic cells on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Phagocytes are

Phagocytes are

retrieved on November 28, 2008. Fro

''Physiology or Medicine 1901–1921'', Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1967. Mechnikov was awarded the 1908

Evolution of the innate immune system.

retrieved on March 20, 2009 Phagocytes of humans and other animals are called "professional" or "non-professional" depending on how effective they are at

Phagocytosis is the process of taking in particles such as bacteria, invasive

Phagocytosis is the process of taking in particles such as bacteria, invasive  A phagocyte has many types of receptors on its surface that are used to bind material. They include

A phagocyte has many types of receptors on its surface that are used to bind material. They include

The killing of microbes is a critical function of phagocytes that is performed either within the phagocyte (

The killing of microbes is a critical function of phagocytes that is performed either within the phagocyte (

Phagocytes can also kill microbes by oxygen-independent methods, but these are not as effective as the oxygen-dependent ones. There are four main types. The first uses electrically charged proteins that damage the bacterium's

Phagocytes can also kill microbes by oxygen-independent methods, but these are not as effective as the oxygen-dependent ones. There are four main types. The first uses electrically charged proteins that damage the bacterium's

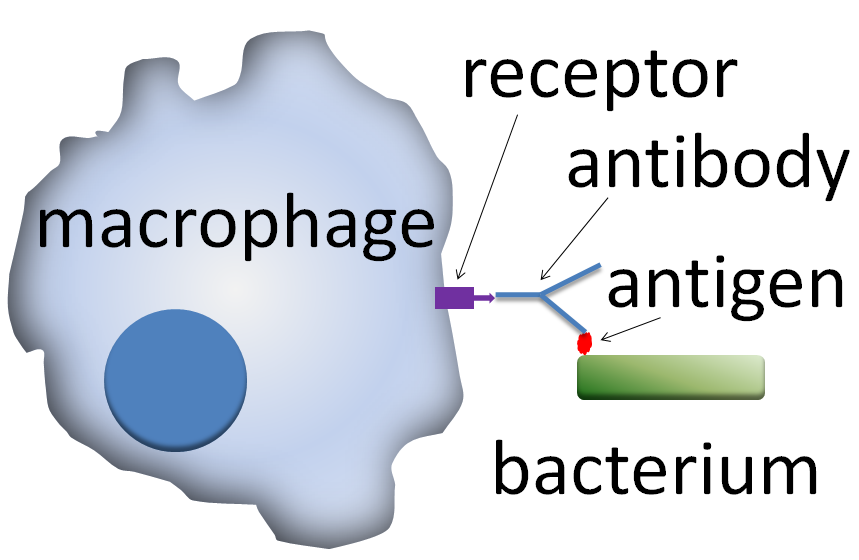

Antigen presentation is a process in which some phagocytes move parts of engulfed materials back to the surface of their cells and "present" them to other cells of the immune system. There are two "professional" antigen-presenting cells: macrophages and dendritic cells. After engulfment, foreign proteins (the

Antigen presentation is a process in which some phagocytes move parts of engulfed materials back to the surface of their cells and "present" them to other cells of the immune system. There are two "professional" antigen-presenting cells: macrophages and dendritic cells. After engulfment, foreign proteins (the

Phagocytes of humans and other jawed vertebrates are divided into "professional" and "non-professional" groups based on the efficiency with which they participate in phagocytosis. The professional phagocytes are the monocytes,

Phagocytes of humans and other jawed vertebrates are divided into "professional" and "non-professional" groups based on the efficiency with which they participate in phagocytosis. The professional phagocytes are the monocytes,

When an infection occurs, a chemical "SOS" signal is given off to attract phagocytes to the site. These chemical signals may include proteins from invading bacteria, clotting system

When an infection occurs, a chemical "SOS" signal is given off to attract phagocytes to the site. These chemical signals may include proteins from invading bacteria, clotting system

Induced innate responses to infection.

/ref> To reach the site of infection, phagocytes leave the bloodstream and enter the affected tissues. Signals from the infection cause the

Monocytes develop in the bone marrow and reach maturity in the blood. Mature monocytes have large, smooth, lobed nuclei and abundant

Monocytes develop in the bone marrow and reach maturity in the blood. Mature monocytes have large, smooth, lobed nuclei and abundant

This type of phagocyte does not have granules but contains many

This type of phagocyte does not have granules but contains many

Neutrophils are normally found in the

Neutrophils are normally found in the

Dendritic cells are specialized antigen-presenting cells that have long outgrowths called dendrites, that help to engulf microbes and other invaders. Dendritic cells are present in the tissues that are in contact with the external environment, mainly the skin, the inner lining of the nose, the lungs, the stomach, and the intestines. Once activated, they mature and migrate to the lymphoid tissues where they interact with

Dendritic cells are specialized antigen-presenting cells that have long outgrowths called dendrites, that help to engulf microbes and other invaders. Dendritic cells are present in the tissues that are in contact with the external environment, mainly the skin, the inner lining of the nose, the lungs, the stomach, and the intestines. Once activated, they mature and migrate to the lymphoid tissues where they interact with

A pathogen is only successful in infecting an organism if it can get past its defenses. Pathogenic bacteria and protozoa have developed a variety of methods to resist attacks by phagocytes, and many actually survive and replicate within phagocytic cells.

A pathogen is only successful in infecting an organism if it can get past its defenses. Pathogenic bacteria and protozoa have developed a variety of methods to resist attacks by phagocytes, and many actually survive and replicate within phagocytic cells.

Bacteria have developed ways to survive inside phagocytes, where they continue to evade the immune system. To get safely inside the phagocyte they express proteins called

Bacteria have developed ways to survive inside phagocytes, where they continue to evade the immune system. To get safely inside the phagocyte they express proteins called

Some survival strategies often involve disrupting cytokines and other methods of

Some survival strategies often involve disrupting cytokines and other methods of

Website

* * * *

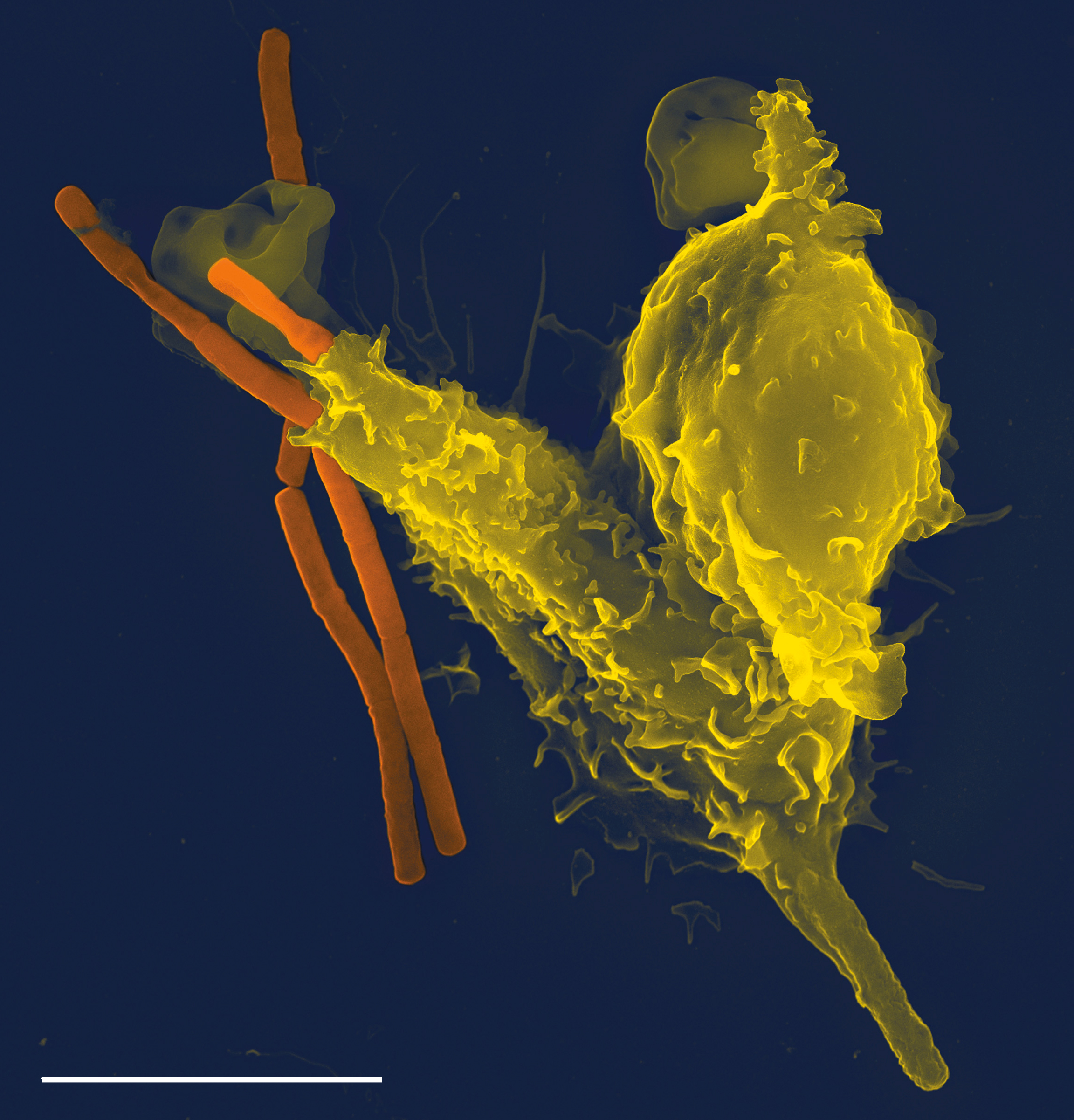

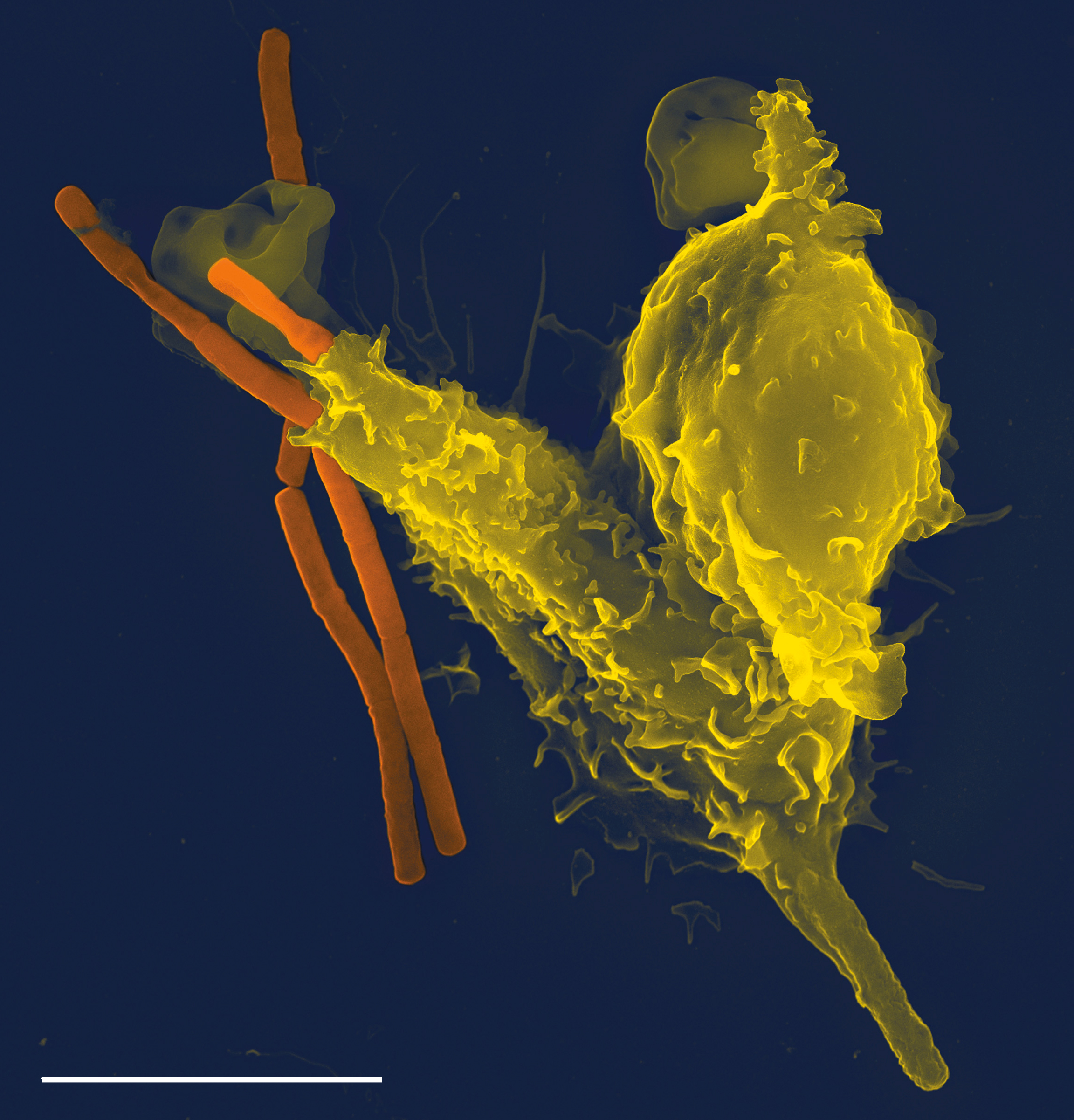

White blood cell engulfing bacteria

{{featured article Immune system Leukocytes

Phagocytes are

Phagocytes are cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery ...

s that protect the body by ingesting harmful foreign particles, bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

, and dead or dying

Dying is the final stage of life which will eventually lead to death. Diagnosing dying is a complex process of clinical decision-making, and most practice checklists facilitating this diagnosis are based on cancer diagnoses.

Signs of dying ...

cells. Their name comes from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

', "to eat" or "devour", and "-cyte", the suffix in biology denoting "cell", from the Greek ''kutos'', "hollow vessel". They are essential for fighting infections and for subsequent immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

. Phagocytes are important throughout the animal kingdom and are highly developed within vertebrates. One litre

The litre (international spelling) or liter (American English spelling) (SI symbols L and l, other symbol used: ℓ) is a metric unit of volume. It is equal to 1 cubic decimetre (dm3), 1000 cubic centimetres (cm3) or 0.001 cubic metre (m3). ...

of human blood contains about six billion phagocytes. They were discovered in 1882 by Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov

Ilya, Iliya, Ilia, Ilja, or Ilija (russian: Илья́, Il'ja, , or russian: Илия́, Ilija, ; uk, Ілля́, Illia, ; be, Ілья́, Iĺja ) is the East Slavic form of the male Hebrew name Eliyahu (Eliahu), meaning "My God is Yahu/ Jah ...

while he was studying starfish

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle stars or basket stars. Starfish ...

larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

The ...

e.Ilya Mechnikovretrieved on November 28, 2008. Fro

''Physiology or Medicine 1901–1921'', Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1967. Mechnikov was awarded the 1908

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accord ...

for his discovery. Phagocytes occur in many species; some amoebae

An amoeba (; less commonly spelled ameba or amœba; plural ''am(o)ebas'' or ''am(o)ebae'' ), often called an amoeboid, is a type of cell or unicellular organism with the ability to alter its shape, primarily by extending and retracting pseudopo ...

behave like macrophage phagocytes, which suggests that phagocytes appeared early in the evolution of life.Janeway, ChapterEvolution of the innate immune system.

retrieved on March 20, 2009 Phagocytes of humans and other animals are called "professional" or "non-professional" depending on how effective they are at

phagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis is ...

. The professional phagocytes include many types of white blood cell

White blood cells, also called leukocytes or leucocytes, are the cell (biology), cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign invaders. All white blood cells are produced and de ...

s (such as neutrophil

Neutrophils (also known as neutrocytes or heterophils) are the most abundant type of granulocytes and make up 40% to 70% of all white blood cells in humans. They form an essential part of the innate immune system, with their functions varying ...

s, monocyte

Monocytes are a type of leukocyte or white blood cell. They are the largest type of leukocyte in blood and can differentiate into macrophages and conventional dendritic cells. As a part of the vertebrate innate immune system monocytes also ...

s, macrophage

Macrophages (abbreviated as M φ, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακρός'' (') = large, ''φαγεῖν'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer cel ...

s, mast cell

A mast cell (also known as a mastocyte or a labrocyte) is a resident cell of connective tissue that contains many granules rich in histamine and heparin. Specifically, it is a type of granulocyte derived from the myeloid stem cell that is a par ...

s, and dendritic cells). and The main difference between professional and non-professional phagocytes is that the professional phagocytes have molecules called receptors

Receptor may refer to:

*Sensory receptor, in physiology, any structure which, on receiving environmental stimuli, produces an informative nerve impulse

*Receptor (biochemistry), in biochemistry, a protein molecule that receives and responds to a n ...

on their surfaces that can detect harmful objects, such as bacteria, that are not normally found in the body. Phagocytes are crucial in fighting infections, as well as in maintaining healthy tissues by removing dead and dying cells that have reached the end of their lifespan.

During an infection, chemical signals attract phagocytes to places where the pathogen has invaded the body. These chemicals may come from bacteria or from other phagocytes already present. The phagocytes move by a method called chemotaxis

Chemotaxis (from '' chemo-'' + ''taxis'') is the movement of an organism or entity in response to a chemical stimulus. Somatic cells, bacteria, and other single-cell or multicellular organisms direct their movements according to certain chemica ...

. When phagocytes come into contact with bacteria, the receptors on the phagocyte's surface will bind to them. This binding will lead to the engulfing of the bacteria by the phagocyte. Some phagocytes kill the ingested pathogen with oxidants

An oxidizing agent (also known as an oxidant, oxidizer, electron recipient, or electron acceptor) is a substance in a redox chemical reaction that gains or " accepts"/"receives" an electron from a (called the , , or ). In other words, an oxi ...

and nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes denoted by a dot in its che ...

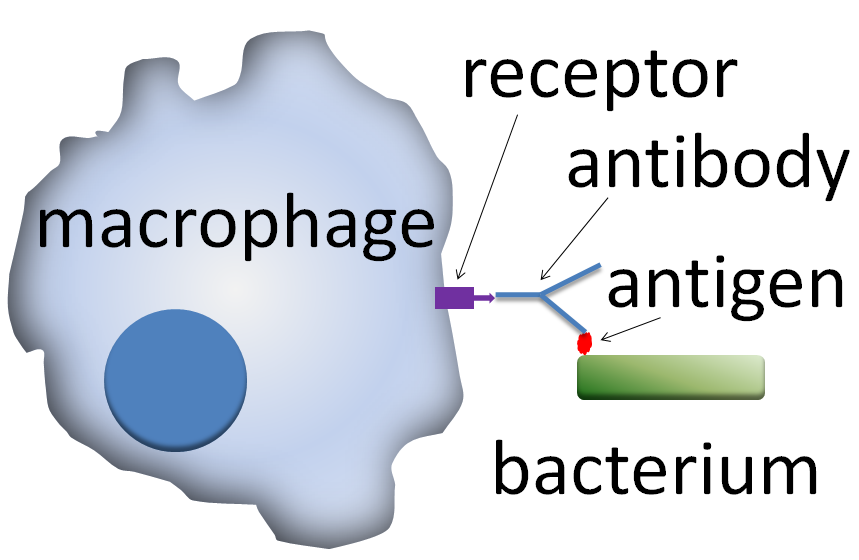

. After phagocytosis, macrophages and dendritic cells can also participate in antigen presentation

Antigen presentation is a vital immune process that is essential for T cell immune response triggering. Because T cells recognize only fragmented antigens displayed on cell surfaces, antigen processing must occur before the antigen fragment, n ...

, a process in which a phagocyte moves parts of the ingested material back to its surface. This material is then displayed to other cells of the immune system. Some phagocytes then travel to the body's lymph node

A lymph node, or lymph gland, is a kidney-shaped organ of the lymphatic system and the adaptive immune system. A large number of lymph nodes are linked throughout the body by the lymphatic vessels. They are major sites of lymphocytes that inclu ...

s and display the material to white blood cells called lymphocytes

A lymphocyte is a type of white blood cell (leukocyte) in the immune system of most vertebrates. Lymphocytes include natural killer cells (which function in cell-mediated, cytotoxic innate immunity), T cells (for cell-mediated, cytotoxic adap ...

. This process is important in building immunity, and many pathogens have evolved methods to evade attacks by phagocytes.

History

The Russian zoologistIlya Ilyich Mechnikov

Ilya, Iliya, Ilia, Ilja, or Ilija (russian: Илья́, Il'ja, , or russian: Илия́, Ilija, ; uk, Ілля́, Illia, ; be, Ілья́, Iĺja ) is the East Slavic form of the male Hebrew name Eliyahu (Eliahu), meaning "My God is Yahu/ Jah ...

(1845–1916) first recognized that specialized cells were involved in defense against microbial infections. In 1882, he studied motile

Motility is the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy.

Definitions

Motility, the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy, can be contrasted with sessility, the state of organisms th ...

(freely moving) cells in the larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

The ...

e of starfishes, believing they were important to the animals' immune defenses. To test his idea, he inserted small thorns from a tangerine

The tangerine is a type of citrus fruit that is orange in color. Its scientific name varies. It has been treated as a separate species under the name ''Citrus tangerina'' or ''Citrus'' × ''tangerina'', or treated as a variety of ''Citrus retic ...

tree into the larvae. After a few hours he noticed that the motile cells had surrounded the thorns. Mechnikov traveled to Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

and shared his ideas with Carl Friedrich Claus

Carl Friedrich Claus (born 9 November 1827 in Kassel; died 29 August 1900 in London) was a German chemist and inventor. He patented the Claus process.

Life

Claus studied chemistry at University of Marburg in Germany. He emigrated to England, ...

who suggested the name "phagocyte" (from the Greek words ', meaning "to eat or devour", and ', meaning "hollow vessel") for the cells that Mechnikov had observed.

A year later, Mechnikov studied a fresh water crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

called ''Daphnia

''Daphnia'' is a genus of small planktonic crustaceans, in length. ''Daphnia'' are members of the order Anomopoda, and are one of the several small aquatic crustaceans commonly called water fleas because their saltatory swimming style resembl ...

'', a tiny transparent animal that can be examined directly under a microscope. He discovered that fungal spores that attacked the animal were destroyed by phagocytes. He went on to extend his observations to the white blood cells of mammals and discovered that the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis

''Bacillus anthracis'' is a gram-positive and rod-shaped bacterium that causes anthrax, a deadly disease to livestock and, occasionally, to humans. It is the only permanent ( obligate) pathogen within the genus ''Bacillus''. Its infection is a ...

'' could be engulfed and killed by phagocytes, a process that he called phagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis is ...

. Mechnikov proposed that phagocytes were a primary defense against invading organisms.

In 1903, Almroth Wright

Sir Almroth Edward Wright (10 August 1861 – 30 April 1947) was a British bacteriologist and immunologist.

He is notable for developing a system of anti-typhoid fever inoculation, recognizing early on that antibiotics would create resistant ...

discovered that phagocytosis was reinforced by specific antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

that he called opsonin

Opsonins are extracellular proteins that, when bound to substances or cells, induce phagocytes to phagocytose the substances or cells with the opsonins bound. Thus, opsonins act as tags to label things in the body that should be phagocytosed (i.e. ...

s, from the Greek ''opson

''Opson'' ( el, ὄψον) is an important category in Ancient Greek foodways.

First and foremost ''opson'' refers to a major division of ancient Greek food: the 'relish' that complements the ''sitos'' (σίτος) the staple part of the meal, i ...

'', "a dressing or relish". Mechnikov was awarded (jointly with Paul Ehrlich

Paul Ehrlich (; 14 March 1854 – 20 August 1915) was a Nobel Prize-winning German physician and scientist who worked in the fields of hematology, immunology, and antimicrobial chemotherapy. Among his foremost achievements were finding a cure ...

) the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accord ...

for his work on phagocytes and phagocytosis.

Although the importance of these discoveries slowly gained acceptance during the early twentieth century, the intricate relationships between phagocytes and all the other components of the immune system were not known until the 1980s.

Phagocytosis

Phagocytosis is the process of taking in particles such as bacteria, invasive

Phagocytosis is the process of taking in particles such as bacteria, invasive fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

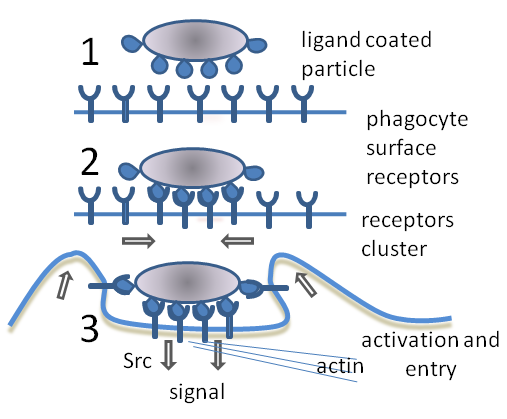

, parasites, dead host cells, and cellular and foreign debris by a cell. It involves a chain of molecular processes. Phagocytosis occurs after the foreign body, a bacterial cell, for example, has bound to molecules called "receptors" that are on the surface of the phagocyte. The phagocyte then stretches itself around the bacterium and engulfs it. Phagocytosis of bacteria by human neutrophils takes on average nine minutes. Once inside this phagocyte, the bacterium is trapped in a compartment called a phagosome

In cell biology, a phagosome is a vesicle formed around a particle engulfed by a phagocyte via phagocytosis. Professional phagocytes include macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (DCs).

A phagosome is formed by the fusion of the cell ...

. Within one minute the phagosome merges with either a lysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle found in many animal cells. They are spherical vesicles that contain hydrolytic enzymes that can break down many kinds of biomolecules. A lysosome has a specific composition, of both its membrane prot ...

or a granule to form a phagolysosome

In biology, a phagolysosome, or endolysosome, is a cytoplasmic body formed by the fusion of a phagosome with a lysosome in a process that occurs during phagocytosis. Formation of phagolysosomes is essential for the intracellular destruction of mic ...

. The bacterium is then subjected to an overwhelming array of killing mechanisms and is dead a few minutes later. Dendritic cells and macrophages are not so fast, and phagocytosis can take many hours in these cells. Macrophages are slow and untidy eaters; they engulf huge quantities of material and frequently release some undigested back into the tissues. This debris serves as a signal to recruit more phagocytes from the blood. Phagocytes have voracious appetites; scientists have even fed macrophages with iron filings and then used a small magnet to separate them from other cells.

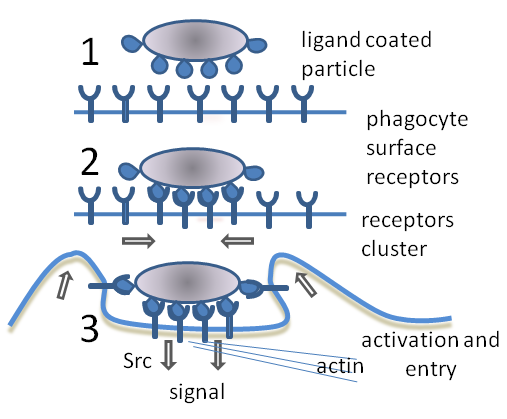

A phagocyte has many types of receptors on its surface that are used to bind material. They include

A phagocyte has many types of receptors on its surface that are used to bind material. They include opsonin

Opsonins are extracellular proteins that, when bound to substances or cells, induce phagocytes to phagocytose the substances or cells with the opsonins bound. Thus, opsonins act as tags to label things in the body that should be phagocytosed (i.e. ...

receptors, scavenger receptors, and Toll-like receptors

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a class of proteins that play a key role in the innate immune system. They are single-pass membrane-spanning receptors usually expressed on sentinel cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells, that recognize s ...

. Opsonin receptors increase the phagocytosis of bacteria that have been coated with immunoglobulin G

Immunoglobulin G (Ig G) is a type of antibody. Representing approximately 75% of serum antibodies in humans, IgG is the most common type of antibody found in blood circulation. IgG molecules are created and released by plasma B cells. Each IgG a ...

(IgG) antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

or with complement

A complement is something that completes something else.

Complement may refer specifically to:

The arts

* Complement (music), an interval that, when added to another, spans an octave

** Aggregate complementation, the separation of pitch-clas ...

. "Complement" is the name given to a complex series of protein molecules found in the blood that destroy cells or mark them for destruction. Scavenger receptors bind to a large range of molecules on the surface of bacterial cells, and Toll-like receptors—so called because of their similarity to well-studied receptors in fruit flies that are encoded by the Toll gene—bind to more specific molecules. Binding to Toll-like receptors increases phagocytosis and causes the phagocyte to release a group of hormones that cause inflammation

Inflammation (from la, wikt:en:inflammatio#Latin, inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or Irritation, irritants, and is a protective response involving im ...

.

Methods of killing

The killing of microbes is a critical function of phagocytes that is performed either within the phagocyte (

The killing of microbes is a critical function of phagocytes that is performed either within the phagocyte (intracellular

This glossary of biology terms is a list of definitions of fundamental terms and concepts used in biology, the study of life and of living organisms. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical definitions ...

killing) or outside of the phagocyte (extracellular

This glossary of biology terms is a list of definitions of fundamental terms and concepts used in biology, the study of life and of living organisms. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical definitions ...

killing).

Oxygen-dependent intracellular

When a phagocyte ingests bacteria (or any material), its oxygen consumption increases. The increase in oxygen consumption, called arespiratory burst

Respiratory burst (or oxidative burst) is the rapid release of the reactive oxygen species (ROS), superoxide anion () and hydrogen peroxide (), from different cell types.

This is usually utilised for mammalian immunological defence, but also play ...

, produces reactive oxygen-containing molecules that are anti-microbial. The oxygen compounds are toxic to both the invader and the cell itself, so they are kept in compartments inside the cell. This method of killing invading microbes by using the reactive oxygen-containing molecules is referred to as oxygen-dependent intracellular killing, of which there are two types.

The first type is the oxygen-dependent production of a superoxide

In chemistry, a superoxide is a compound that contains the superoxide ion, which has the chemical formula . The systematic name of the anion is dioxide(1−). The reactive oxygen ion superoxide is particularly important as the product of t ...

, which is an oxygen-rich bacteria-killing substance. The superoxide is converted to hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscous than water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usually as a dilute solution (3%� ...

and singlet oxygen

Singlet oxygen, systematically named dioxygen(singlet) and dioxidene, is a gaseous inorganic chemical with the formula O=O (also written as or ), which is in a quantum state where all electrons are spin paired. It is kinetically unstable at ambie ...

by an enzyme called superoxide dismutase. Superoxides also react with the hydrogen peroxide to produce hydroxyl radicals

The hydroxyl radical is the diatomic molecule . The hydroxyl radical is very stable as a dilute gas, but it decays very rapidly in the condensed phase. It is pervasive in some situations. Most notably the hydroxyl radicals are produced from the ...

, which assist in killing the invading microbe.

The second type involves the use of the enzyme myeloperoxidase

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is a peroxidase enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''MPO'' gene on chromosome 17. MPO is most abundantly expressed in neutrophil granulocytes (a subtype of white blood cells), and produces hypohalous acids to carry ou ...

from neutrophil granules. When granules fuse with a phagosome, myeloperoxidase is released into the phagolysosome, and this enzyme uses hydrogen peroxide and chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate betwee ...

to create hypochlorite

In chemistry, hypochlorite is an anion with the chemical formula ClO−. It combines with a number of cations to form hypochlorite salts. Common examples include sodium hypochlorite (household bleach) and calcium hypochlorite (a component of ble ...

, a substance used in domestic bleach

Bleach is the generic name for any chemical product that is used industrially or domestically to remove color (whitening) from a fabric or fiber or to clean or to remove stains in a process called bleaching. It often refers specifically, to ...

. Hypochlorite is extremely toxic to bacteria. Myeloperoxidase contains a heme

Heme, or haem (pronounced / hi:m/ ), is a precursor to hemoglobin, which is necessary to bind oxygen in the bloodstream. Heme is biosynthesized in both the bone marrow and the liver.

In biochemical terms, heme is a coordination complex "consis ...

pigment, which accounts for the green color of secretions rich in neutrophils, such as pus

Pus is an exudate, typically white-yellow, yellow, or yellow-brown, formed at the site of inflammation during bacterial or fungal infection. An accumulation of pus in an enclosed tissue space is known as an abscess, whereas a visible collection ...

and infected sputum.

Oxygen-independent intracellular

Phagocytes can also kill microbes by oxygen-independent methods, but these are not as effective as the oxygen-dependent ones. There are four main types. The first uses electrically charged proteins that damage the bacterium's

Phagocytes can also kill microbes by oxygen-independent methods, but these are not as effective as the oxygen-dependent ones. There are four main types. The first uses electrically charged proteins that damage the bacterium's membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. B ...

. The second type uses lysozymes; these enzymes break down the bacterial cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mech ...

. The third type uses lactoferrin

Lactoferrin (LF), also known as lactotransferrin (LTF), is a multifunctional protein of the transferrin family. Lactoferrin is a globular glycoprotein with a molecular mass of about 80 kDa that is widely represented in various secretory fluids, s ...

s, which are present in neutrophil granules and remove essential iron from bacteria. The fourth type uses proteases

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the for ...

and hydrolytic enzymes

Hydrolase is a class of enzyme that commonly perform as biochemical catalysts that use water to break a chemical bond, which typically results in dividing a larger molecule into smaller molecules. Some common examples of hydrolase enzymes are este ...

; these enzymes are used to digest the proteins of destroyed bacteria.

Extracellular

Interferon-gamma

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) is a dimerized soluble cytokine that is the only member of the type II class of interferons. The existence of this interferon, which early in its history was known as immune interferon, was described by E. F. Wheelock ...

—which was once called macrophage activating factor—stimulates macrophages to produce nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes denoted by a dot in its che ...

. The source of interferon-gamma can be CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, natural killer cells

Natural killer cells, also known as NK cells or large granular lymphocytes (LGL), are a type of cytotoxic lymphocyte critical to the innate immune system that belong to the rapidly expanding family of known innate lymphoid cells (ILC) and represen ...

, B cells

B cells, also known as B lymphocytes, are a type of white blood cell of the lymphocyte subtype. They function in the humoral immunity component of the adaptive immune system. B cells produce antibody molecules which may be either secreted or ...

, natural killer T cells, monocytes, macrophages, or dendritic cells. Nitric oxide is then released from the macrophage and, because of its toxicity, kills microbes near the macrophage. Activated macrophages produce and secrete tumor necrosis factor

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF, cachexin, or cachectin; formerly known as tumor necrosis factor alpha or TNF-α) is an adipokine and a cytokine. TNF is a member of the TNF superfamily, which consists of various transmembrane proteins with a homolog ...

. This cytokine

Cytokines are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling. Cytokines are peptides and cannot cross the lipid bilayer of cells to enter the cytoplasm. Cytokines have been shown to be involved in autocrin ...

—a class of signaling molecule—kills cancer cells and cells infected by viruses, and helps to activate the other cells of the immune system.

In some diseases, e.g., the rare chronic granulomatous disease

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), also known as Bridges–Good syndrome, chronic granulomatous disorder, and Quie syndrome, is a diverse group of hereditary diseases in which certain cells of the immune system have difficulty forming the reacti ...

, the efficiency of phagocytes is impaired, and recurrent bacterial infections are a problem. In this disease there is an abnormality affecting different elements of oxygen-dependent killing. Other rare congenital abnormalities, such as Chédiak–Higashi syndrome

Chédiak–Higashi syndrome (CHS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder that arises from a mutation of a lysosomal trafficking regulator protein, which leads to a decrease in phagocytosis. The decrease in phagocytosis results in recurrent pyogeni ...

, are also associated with defective killing of ingested microbes.

Viruses

Virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es can reproduce only inside cells, and they gain entry by using many of the receptors involved in immunity. Once inside the cell, viruses use the cell's biological machinery to their own advantage, forcing the cell to make hundreds of identical copies of themselves. Although phagocytes and other components of the innate immune system can, to a limited extent, control viruses, once a virus is inside a cell the adaptive immune responses, particularly the lymphocytes, are more important for defense. At the sites of viral infections, lymphocytes often vastly outnumber all the other cells of the immune system; this is common in viral meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or ...

. Virus-infected cells that have been killed by lymphocytes are cleared from the body by phagocytes.

Role in apoptosis

In an animal, cells are constantly dying. A balance betweencell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell (biology), cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukar ...

and cell death keeps the number of cells relatively constant in adults. There are two different ways a cell can die: by necrosis

Necrosis () is a form of cell injury which results in the premature death of cells in living tissue by autolysis. Necrosis is caused by factors external to the cell or tissue, such as infection, or trauma which result in the unregulated dige ...

or by apoptosis. In contrast to necrosis, which often results from disease or trauma, apoptosis—or programmed cell death

Programmed cell death (PCD; sometimes referred to as cellular suicide) is the death of a cell (biology), cell as a result of events inside of a cell, such as apoptosis or autophagy. PCD is carried out in a biological process, which usually confers ...

—is a normal healthy function of cells. The body has to rid itself of millions of dead or dying cells every day, and phagocytes play a crucial role in this process.

Dying cells that undergo the final stages of apoptosis

Apoptosis (from grc, ἀπόπτωσις, apóptōsis, 'falling off') is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms. Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (morphology) and death. These changes incl ...

display molecules, such as phosphatidylserine

Phosphatidylserine (abbreviated Ptd-L-Ser or PS) is a phospholipid and is a component of the cell membrane. It plays a key role in cell cycle signaling, specifically in relation to apoptosis. It is a key pathway for viruses to enter cells via ap ...

, on their cell surface to attract phagocytes. (Free registration required for online access) Phosphatidylserine is normally found on the cytosolic

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells (intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondrio ...

surface of the plasma membrane, but is redistributed during apoptosis to the extracellular surface by a protein known as scramblase

Scramblase is a protein responsible for the translocation of phospholipids between the two monolayers of a lipid bilayer of a cell membrane. In humans, phospholipid scramblases (PLSCRs) constitute a family of five homologous proteins tha ...

. (Free registration required for online access) These molecules mark the cell for phagocytosis by cells that possess the appropriate receptors, such as macrophages. The removal of dying cells by phagocytes occurs in an orderly manner without eliciting an inflammatory response

Inflammation (from la, inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants, and is a protective response involving immune cells, blood vessels, and molecu ...

and is an important function of phagocytes.

Interactions with other cells

Phagocytes are usually not bound to any particular organ but move through the body interacting with the other phagocytic and non-phagocytic cells of the immune system. They can communicate with other cells by producing chemicals calledcytokines

Cytokines are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling. Cytokines are peptides and cannot cross the lipid bilayer of cells to enter the cytoplasm. Cytokines have been shown to be involved in autocrin ...

, which recruit other phagocytes to the site of infections or stimulate dormant lymphocyte

A lymphocyte is a type of white blood cell (leukocyte) in the immune system of most vertebrates. Lymphocytes include natural killer cells (which function in cell-mediated, cytotoxic innate immunity), T cells (for cell-mediated, cytotoxic ad ...

s. Phagocytes form part of the innate immune system

The innate, or nonspecific, immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies (the other being the adaptive immune system) in vertebrates. The innate immune system is an older evolutionary defense strategy, relatively speaking, and is the ...

, which animals, including humans, are born with. Innate immunity is very effective but non-specific in that it does not discriminate between different sorts of invaders. On the other hand, the adaptive immune system

The adaptive immune system, also known as the acquired immune system, is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized, systemic cells and processes that eliminate pathogens or prevent their growth. The acquired immune system ...

of jawed vertebrates—the basis of acquired immunity—is highly specialized and can protect against almost any type of invader. The adaptive immune system is not dependent on phagocytes but lymphocytes, which produce protective proteins called antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

, which tag invaders for destruction and prevent viruses from infecting cells. Phagocytes, in particular dendritic cells and macrophages, stimulate lymphocytes to produce antibodies by an important process called antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

presentation.

Antigen presentation

antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

s) are broken down into peptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

A ...

s inside dendritic cells and macrophages. These peptides are then bound to the cell's major histocompatibility complex

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a large locus on vertebrate DNA containing a set of closely linked polymorphic genes that code for cell surface proteins essential for the adaptive immune system. These cell surface proteins are calle ...

(MHC) glycoproteins, which carry the peptides back to the phagocyte's surface where they can be "presented" to lymphocytes. Mature macrophages do not travel far from the site of infection, but dendritic cells can reach the body's lymph node

A lymph node, or lymph gland, is a kidney-shaped organ of the lymphatic system and the adaptive immune system. A large number of lymph nodes are linked throughout the body by the lymphatic vessels. They are major sites of lymphocytes that inclu ...

s, where there are millions of lymphocytes. This enhances immunity because the lymphocytes respond to the antigens presented by the dendritic cells just as they would at the site of the original infection. But dendritic cells can also destroy or pacify lymphocytes if they recognize components of the host body; this is necessary to prevent autoimmune reactions. This process is called tolerance.

Immunological tolerance

Dendritic cells also promote immunological tolerance, which stops the body from attacking itself. The first type of tolerance iscentral tolerance

In immunology, central tolerance (also known as negative selection) is the process of eliminating any ''developing'' T or B lymphocytes that are autoreactive, i.e. reactive to the body itself. Through elimination of autoreactive lymphocytes, to ...

, that occurs in the thymus. T cell

A T cell is a type of lymphocyte. T cells are one of the important white blood cells of the immune system and play a central role in the adaptive immune response. T cells can be distinguished from other lymphocytes by the presence of a T-cell r ...

s that bind (via their T cell receptor) to self antigen (presented by dendritic cells on MHC molecules) too strongly are induced to die. The second type of immunological tolerance is peripheral tolerance.

Some self reactive T cells escape the thymus for a number of reasons, mainly due to the lack of expression of some self antigens in the thymus. Another type of T cell; T regulatory cells can down regulate self reactive T cells in the periphery. When immunological tolerance fails, autoimmune disease

An autoimmune disease is a condition arising from an abnormal immune response to a functioning body part. At least 80 types of autoimmune diseases have been identified, with some evidence suggesting that there may be more than 100 types. Nearly a ...

s can follow.

Professional phagocytes

Phagocytes of humans and other jawed vertebrates are divided into "professional" and "non-professional" groups based on the efficiency with which they participate in phagocytosis. The professional phagocytes are the monocytes,

Phagocytes of humans and other jawed vertebrates are divided into "professional" and "non-professional" groups based on the efficiency with which they participate in phagocytosis. The professional phagocytes are the monocytes, macrophages

Macrophages (abbreviated as M φ, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακρός'' (') = large, ''φαγεῖν'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer ce ...

, neutrophils, tissue dendritic cells and mast cell

A mast cell (also known as a mastocyte or a labrocyte) is a resident cell of connective tissue that contains many granules rich in histamine and heparin. Specifically, it is a type of granulocyte derived from the myeloid stem cell that is a par ...

s. One litre

The litre (international spelling) or liter (American English spelling) (SI symbols L and l, other symbol used: ℓ) is a metric unit of volume. It is equal to 1 cubic decimetre (dm3), 1000 cubic centimetres (cm3) or 0.001 cubic metre (m3). ...

of human blood contains about six billion phagocytes.

Activation

All phagocytes, and especially macrophages, exist in degrees of readiness. Macrophages are usually relatively dormant in the tissues and proliferate slowly. In this semi-resting state, they clear away dead host cells and other non-infectious debris and rarely take part in antigen presentation. But, during an infection, they receive chemical signals—usuallyinterferon gamma

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) is a dimerized soluble cytokine that is the only member of the type II class of interferons. The existence of this interferon, which early in its history was known as immune interferon, was described by E. F. Wheeloc ...

—which increases their production of MHC II

MHC Class II molecules are a class of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules normally found only on professional antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells, mononuclear phagocytes, some endothelial cells, thymic epithelial cells, ...

molecules and which prepares them for presenting antigens. In this state, macrophages are good antigen presenters and killers. If they receive a signal directly from an invader, they become "hyperactivated", stop proliferating, and concentrate on killing. Their size and rate of phagocytosis increases—some become large enough to engulf invading protozoa

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris. Histo ...

.

In the blood, neutrophils are inactive but are swept along at high speed. When they receive signals from macrophages at the sites of inflammation, they slow down and leave the blood. In the tissues, they are activated by cytokines and arrive at the battle scene ready to kill.

Migration

peptides

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

A p ...

, complement

A complement is something that completes something else.

Complement may refer specifically to:

The arts

* Complement (music), an interval that, when added to another, spans an octave

** Aggregate complementation, the separation of pitch-clas ...

products, and cytokines that have been given off by macrophages located in the tissue near the infection site. Another group of chemical attractants are cytokines

Cytokines are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling. Cytokines are peptides and cannot cross the lipid bilayer of cells to enter the cytoplasm. Cytokines have been shown to be involved in autocrin ...

that recruit neutrophils and monocytes from the blood.Janeway, ChapterInduced innate responses to infection.

/ref> To reach the site of infection, phagocytes leave the bloodstream and enter the affected tissues. Signals from the infection cause the

endothelial

The endothelium is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the rest of the vessel ...

cells that line the blood vessels to make a protein called selectin

The selectins (cluster of differentiation 62 or CD62) are a family of cell adhesion molecules (or CAMs). All selectins are single-chain transmembrane glycoproteins that share similar properties to C-type lectins due to a related amino terminus a ...

, which neutrophils stick to on passing by. Other signals called vasodilators loosen the junctions connecting endothelial cells, allowing the phagocytes to pass through the wall. Chemotaxis

Chemotaxis (from '' chemo-'' + ''taxis'') is the movement of an organism or entity in response to a chemical stimulus. Somatic cells, bacteria, and other single-cell or multicellular organisms direct their movements according to certain chemica ...

is the process by which phagocytes follow the cytokine "scent" to the infected spot. Neutrophils travel across epithelial

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is one of the four basic types of animal tissue, along with connective tissue, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. It is a thin, continuous, protective layer of compactly packed cells with a little intercellula ...

cell-lined organs to sites of infection, and although this is an important component of fighting infection, the migration itself can result in disease-like symptoms. During an infection, millions of neutrophils are recruited from the blood, but they die after a few days.

Monocytes

Monocytes develop in the bone marrow and reach maturity in the blood. Mature monocytes have large, smooth, lobed nuclei and abundant

Monocytes develop in the bone marrow and reach maturity in the blood. Mature monocytes have large, smooth, lobed nuclei and abundant cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

that contains granules. Monocytes ingest foreign or dangerous substances and present antigens to other cells of the immune system. Monocytes form two groups: a circulating group and a marginal group that remain in other tissues (approximately 70% are in the marginal group). Most monocytes leave the blood stream after 20–40 hours to travel to tissues and organs and in doing so transform into macrophages or dendritic cells depending on the signals they receive. There are about 500 million monocytes in one litre of human blood.

Macrophages

Mature macrophages do not travel far but stand guard over those areas of the body that are exposed to the outside world. There they act as garbage collectors, antigen presenting cells, or ferocious killers, depending on the signals they receive. They derive from monocytes,granulocyte

Granulocytes are

cells in the innate immune system characterized by the presence of specific granules in their cytoplasm. Such granules distinguish them from the various agranulocytes. All myeloblastic granulocytes are polymorphonuclear. They ha ...

stem cells, or the cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell (biology), cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukar ...

of pre-existing macrophages. Human macrophages are about 21 micrometer Micrometer can mean:

* Micrometer (device), used for accurate measurements by means of a calibrated screw

* American spelling of micrometre

The micrometre ( international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; ...

s in diameter.

This type of phagocyte does not have granules but contains many

This type of phagocyte does not have granules but contains many lysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle found in many animal cells. They are spherical vesicles that contain hydrolytic enzymes that can break down many kinds of biomolecules. A lysosome has a specific composition, of both its membrane prot ...

s. Macrophages are found throughout the body in almost all tissues and organs (e.g., microglial cell

Microglia are a type of neuroglia (glial cell) located throughout the brain and spinal cord. Microglia account for about 7% of cells found within the brain. As the resident macrophage cells, they act as the first and main form of active immune d ...

s in the brain

A brain is an organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It is located in the head, usually close to the sensory organs for senses such as vision. It is the most complex organ in a v ...

and alveolar macrophages in the lungs

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of th ...

), where they silently lie in wait. A macrophage's location can determine its size and appearance. Macrophages cause inflammation through the production of interleukin-1

The Interleukin-1 family (IL-1 family) is a group of 11 cytokines that plays a central role in the regulation of immune and inflammatory responses to infections or sterile insults.

Discovery

Discovery of these cytokines began with studies on t ...

, interleukin-6

Interleukin 6 (IL-6) is an interleukin that acts as both a pro-inflammatory cytokine and an anti-inflammatory myokine. In humans, it is encoded by the ''IL6'' gene.

In addition, osteoblasts secrete IL-6 to stimulate osteoclast formation. Smoo ...

, and TNF-alpha

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF, cachexin, or cachectin; formerly known as tumor necrosis factor alpha or TNF-α) is an adipokine and a cytokine. TNF is a member of the TNF superfamily, which consists of various transmembrane proteins with a homolog ...

. Macrophages are usually only found in tissue and are rarely seen in blood circulation. The life-span of tissue macrophages has been estimated to range from four to fifteen days.

Macrophages can be activated to perform functions that a resting monocyte cannot. T helper cell

The T helper cells (Th cells), also known as CD4+ cells or CD4-positive cells, are a type of T cell that play an important role in the adaptive immune system. They aid the activity of other immune cells by releasing cytokines. They are consider ...

s (also known as effector T cells or Th cells), a sub-group of lymphocytes, are responsible for the activation of macrophages. Th1 cells activate macrophages by signaling with IFN-gamma

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) is a dimerized soluble cytokine that is the only member of the type II class of interferons. The existence of this interferon, which early in its history was known as immune interferon, was described by E. F. Wheelock ...

and displaying the protein CD40 ligand

CD154, also called CD40 ligand or CD40L, is a protein that is primarily expressed on activated T cells and is a member of the TNF superfamily of molecules. It binds to CD40 on antigen-presenting cells (APC), which leads to many effects depending ...

. Other signals include TNF-alpha and lipopolysaccharides

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are large molecules consisting of a lipid and a polysaccharide that are bacterial toxins. They are composed of an O-antigen, an outer core, and an inner core all joined by a covalent bond, and are found in the outer m ...

from bacteria. Th1 cells can recruit other phagocytes to the site of the infection in several ways. They secrete cytokines that act on the bone marrow

Bone marrow is a semi-solid tissue found within the spongy (also known as cancellous) portions of bones. In birds and mammals, bone marrow is the primary site of new blood cell production (or haematopoiesis). It is composed of hematopoietic ce ...

to stimulate the production of monocytes and neutrophils, and they secrete some of the cytokine

Cytokines are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling. Cytokines are peptides and cannot cross the lipid bilayer of cells to enter the cytoplasm. Cytokines have been shown to be involved in autocrin ...

s that are responsible for the migration of monocytes and neutrophils out of the bloodstream. Th1 cells come from the differentiation of CD4+ T cells once they have responded to antigen in the secondary lymphoid tissues. Activated macrophages play a potent role in tumor

A neoplasm () is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of tissue. The process that occurs to form or produce a neoplasm is called neoplasia. The growth of a neoplasm is uncoordinated with that of the normal surrounding tissue, and persists ...

destruction by producing TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, nitric oxide, reactive oxygen compounds, cation

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

ic proteins, and hydrolytic enzymes.

Neutrophils

Neutrophils are normally found in the

Neutrophils are normally found in the bloodstream

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

and are the most abundant type of phagocyte, constituting 50% to 60% of the total circulating white blood cells. One litre of human blood contains about five billion neutrophils, which are about 10 micrometers in diameter and live for only about five days. Once they have received the appropriate signals, it takes them about thirty minutes to leave the blood and reach the site of an infection. They are ferocious eaters and rapidly engulf invaders coated with antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

and complement

A complement is something that completes something else.

Complement may refer specifically to:

The arts

* Complement (music), an interval that, when added to another, spans an octave

** Aggregate complementation, the separation of pitch-clas ...

, and damaged cells or cellular debris. Neutrophils do not return to the blood; they turn into pus

Pus is an exudate, typically white-yellow, yellow, or yellow-brown, formed at the site of inflammation during bacterial or fungal infection. An accumulation of pus in an enclosed tissue space is known as an abscess, whereas a visible collection ...

cells and die. Mature neutrophils are smaller than monocytes and have a segmented nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

* Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucl ...

with several sections; each section is connected by chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important roles in r ...

filaments—neutrophils can have 2–5 segments. Neutrophils do not normally exit the bone marrow until maturity but during an infection neutrophil precursors called metamyelocyte

A metamyelocyte is a cell undergoing granulopoiesis, derived from a myelocyte, and leading to a band cell.

It is characterized by the appearance of a bent nucleus, cytoplasmic granules, and the absence of visible nucleoli. (If the nucleus is n ...

s, myelocytes and promyelocyte

A promyelocyte (or progranulocyte) is a granulocyte precursor, developing from the myeloblast and developing into the myelocyte. Promyelocytes measure 12-20 microns in diameter. The nucleus of a promyelocyte is approximately the same size as a mye ...

s are released.

The intra-cellular granules of the human neutrophil have long been recognized for their protein-destroying and bactericidal properties. Neutrophils can secrete products that stimulate monocytes and macrophages. Neutrophil secretions increase phagocytosis and the formation of reactive oxygen compounds involved in intracellular killing. Secretions from the primary granules of neutrophils stimulate the phagocytosis of IgG

Immunoglobulin G (Ig G) is a type of antibody. Representing approximately 75% of serum antibodies in humans, IgG is the most common type of antibody found in blood circulation. IgG molecules are created and released by plasma B cells. Each IgG ...

-antibody-coated bacteria. When encountering bacteria, fungi or activated platelets they produce web-like chromatin structures known as neutrophil extracellular traps

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are networks of extracellular fibers, primarily composed of DNA from neutrophils, which bind pathogens. Neutrophils are the immune system's first line of defense against infection and have conventionally be ...

(NETs). Composed mainly of DNA, NETs cause death by a process called netosis – after the pathogens are trapped in NETs they are killed by oxidative and non-oxidative mechanisms.

Dendritic cells

T cells

A T cell is a type of lymphocyte. T cells are one of the important white blood cells of the immune system and play a central role in the adaptive immune response. T cells can be distinguished from other lymphocytes by the presence of a T-cell re ...

and B cells

B cells, also known as B lymphocytes, are a type of white blood cell of the lymphocyte subtype. They function in the humoral immunity component of the adaptive immune system. B cells produce antibody molecules which may be either secreted or ...

to initiate and orchestrate the adaptive immune response.

Mature dendritic cells activate T helper cell

The T helper cells (Th cells), also known as CD4+ cells or CD4-positive cells, are a type of T cell that play an important role in the adaptive immune system. They aid the activity of other immune cells by releasing cytokines. They are consider ...

s and cytotoxic T cell

A cytotoxic T cell (also known as TC, cytotoxic T lymphocyte, CTL, T-killer cell, cytolytic T cell, CD8+ T-cell or killer T cell) is a T lymphocyte (a type of white blood cell) that kills cancer cells, cells that are infected by intracellular pa ...

s. The activated helper T cells interact with macrophages and B cells to activate them in turn. In addition, dendritic cells can influence the type of immune response produced; when they travel to the lymphoid areas where T cells are held they can activate T cells, which then differentiate into cytotoxic T cells or helper T cells.

Mast cells

Mast cells haveToll-like receptor

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a class of proteins that play a key role in the innate immune system. They are Bitopic protein, single-pass membrane-spanning Receptor (biochemistry), receptors usually expressed on sentinel cells such as macrophage ...

s and interact with dendritic cells, B cells, and T cells to help mediate adaptive immune functions. Mast cells express MHC class II

MHC Class II molecules are a class of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules normally found only on professional antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells, mononuclear phagocytes, some endothelial cells, thymic epithelial ce ...

molecules and can participate in antigen presentation; however, the mast cell's role in antigen presentation is not very well understood. Mast cells can consume and kill gram-negative bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wall ...

(e.g., salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of rod-shaped (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and ''Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' is the type species and is fur ...

), and process their antigens. They specialize in processing the fimbrial proteins on the surface of bacteria, which are involved in adhesion to tissues. In addition to these functions, mast cells produce cytokines that induce an inflammatory response. This is a vital part of the destruction of microbes because the cytokines attract more phagocytes to the site of infection.

Non-professional phagocytes

Dying cells and foreign organisms are consumed by cells other than the "professional" phagocytes. These cells include epithelial cells,endothelial cell

The endothelium is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the rest of the vessel ...

s, fibroblast

A fibroblast is a type of cell (biology), biological cell that synthesizes the extracellular matrix and collagen, produces the structural framework (Stroma (tissue), stroma) for animal Tissue (biology), tissues, and plays a critical role in wound ...

s, and mesenchymal cells. They are called non-professional phagocytes, to emphasize that, in contrast to professional phagocytes, phagocytosis is not their principal function. Fibroblasts, for example, which can phagocytose collagen in the process of remolding scars, will also make some attempt to ingest foreign particles.

Non-professional phagocytes are more limited than professional phagocytes in the type of particles they can take up. This is due to their lack of efficient phagocytic receptors, in particular opsonin

Opsonins are extracellular proteins that, when bound to substances or cells, induce phagocytes to phagocytose the substances or cells with the opsonins bound. Thus, opsonins act as tags to label things in the body that should be phagocytosed (i.e. ...

s—which are antibodies and complement attached to invaders by the immune system. Additionally, most non-professional phagocytes do not produce reactive oxygen-containing molecules in response to phagocytosis.

Pathogen evasion and resistance

A pathogen is only successful in infecting an organism if it can get past its defenses. Pathogenic bacteria and protozoa have developed a variety of methods to resist attacks by phagocytes, and many actually survive and replicate within phagocytic cells.

A pathogen is only successful in infecting an organism if it can get past its defenses. Pathogenic bacteria and protozoa have developed a variety of methods to resist attacks by phagocytes, and many actually survive and replicate within phagocytic cells.

Avoiding contact

There are several ways bacteria avoid contact with phagocytes. First, they can grow in sites that phagocytes are not capable of traveling to (e.g., the surface of unbroken skin). Second, bacteria can suppress theinflammatory response

Inflammation (from la, inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants, and is a protective response involving immune cells, blood vessels, and molecu ...

; without this response to infection phagocytes cannot respond adequately. Third, some species of bacteria can inhibit the ability of phagocytes to travel to the site of infection by interfering with chemotaxis. Fourth, some bacteria can avoid contact with phagocytes by tricking the immune system into "thinking" that the bacteria are "self". ''Treponema pallidum

''Treponema pallidum'', formerly known as ''Spirochaeta pallida'', is a spirochaete bacterium with various subspecies that cause the diseases syphilis, bejel (also known as endemic syphilis), and yaws. It is transmitted only among humans. It is ...

''—the bacterium that causes syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

—hides from phagocytes by coating its surface with fibronectin

Fibronectin is a high- molecular weight (~500-~600 kDa) glycoprotein of the extracellular matrix that binds to membrane-spanning receptor proteins called integrins. Fibronectin also binds to other extracellular matrix proteins such as collage ...

, which is produced naturally by the body and plays a crucial role in wound healing

Wound healing refers to a living organism's replacement of destroyed or damaged tissue by newly produced tissue.

In undamaged skin, the epidermis (surface, epithelial layer) and dermis (deeper, connective layer) form a protective barrier again ...

.

Avoiding engulfment

Bacteria often produce capsules made of proteins or sugars that coat their cells and interfere with phagocytosis. Some examples are the K5 capsule and O75O antigen

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are large molecules consisting of a lipid and a polysaccharide that are bacterial toxins. They are composed of an O-antigen, an outer core, and an inner core all joined by a covalent bond, and are found in the outer ...

found on the surface of ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escher ...

'', and the exopolysaccharide

Extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) are natural polymers of high molecular weight secreted by microorganisms into their environment. EPSs establish the functional and structural integrity of biofilms, and are considered the fundamental comp ...

capsules of ''Staphylococcus epidermidis

''Staphylococcus epidermidis'' is a Gram-positive bacterium, and one of over 40 species belonging to the genus '' Staphylococcus''. It is part of the normal human microbiota, typically the skin microbiota, and less commonly the mucosal microbio ...

''. ''Streptococcus pneumoniae

''Streptococcus pneumoniae'', or pneumococcus, is a Gram-positive, spherical bacteria, alpha-hemolytic (under aerobic conditions) or beta-hemolytic (under anaerobic conditions), aerotolerant anaerobic member of the genus Streptococcus. They ar ...

'' produces several types of capsule that provide different levels of protection, and group A streptococci

Group A streptococcal infections are a number of infections with ''Streptococcus pyogenes'' a group A streptococcus (GAS). ''S. pyogenes'' is a species of beta-hemolytic gram-positive bacteria that is responsible for a wide range of infections t ...

produce proteins such as M protein and fimbrial proteins to block engulfment. Some proteins hinder opsonin-related ingestion; ''Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often positive ...

'' produces Protein A

Protein A is a 42 kDa surface protein originally found in the cell wall of the bacteria ''Staphylococcus aureus''. It is encoded by the ''spa'' gene and its regulation is controlled by DNA topology, cellular osmolarity, and a two-component system ...

to block antibody receptors, which decreases the effectiveness of opsonins. Enteropathogenic species of the genus Yersinia

''Yersinia'' is a genus of bacteria in the family Yersiniaceae. ''Yersinia'' species are Gram-negative, coccobacilli bacteria, a few micrometers long and fractions of a micrometer in diameter, and are facultative anaerobes. Some members of ''Yer ...

bind with the use of the virulence factor YopH to receptors of phagocytes from which they influence the cells capability to exert phagocytosis.

Survival inside the phagocyte

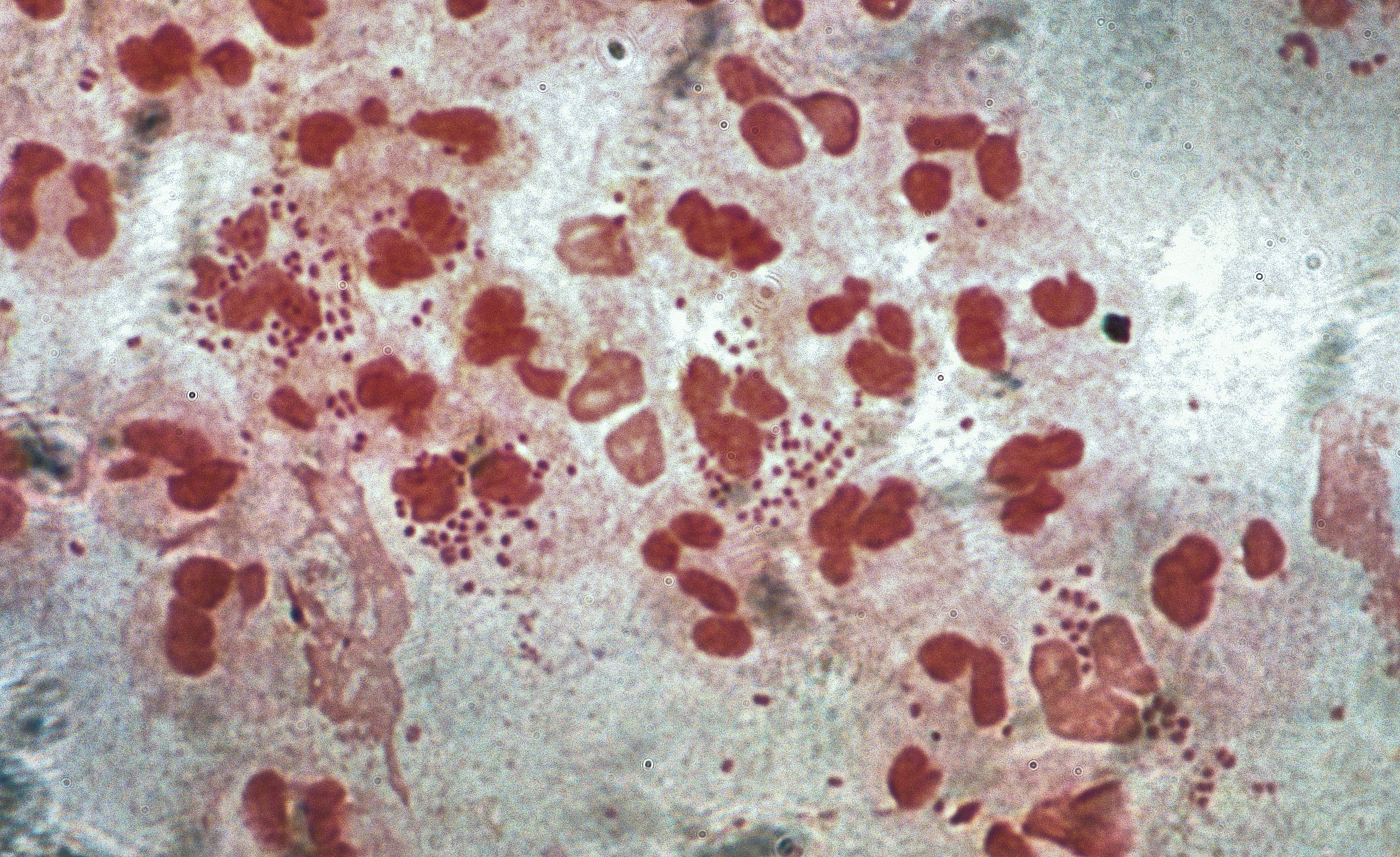

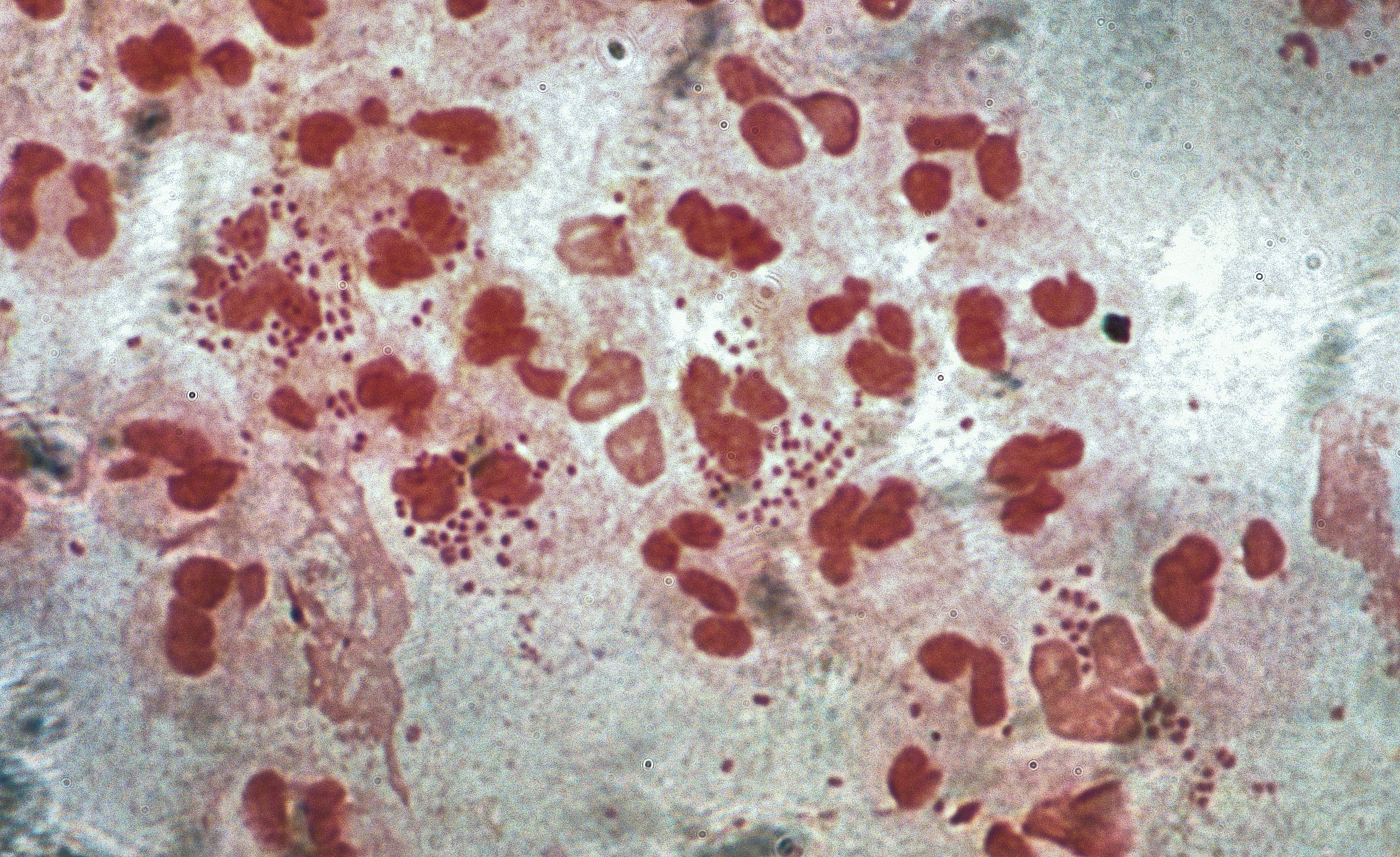

Bacteria have developed ways to survive inside phagocytes, where they continue to evade the immune system. To get safely inside the phagocyte they express proteins called

Bacteria have developed ways to survive inside phagocytes, where they continue to evade the immune system. To get safely inside the phagocyte they express proteins called invasin

Invasins are a class of proteins associated with the penetration of pathogens into host cells. Invasins play a role in promoting entry during the initial stage of infection.

In 2007, Als3 was identified as a fungal invasion allowing ''Candida alb ...

s. When inside the cell they remain in the cytoplasm and avoid toxic chemicals contained in the phagolysosomes. Some bacteria prevent the fusion of a phagosome and lysosome, to form the phagolysosome. Other pathogens, such as '' Leishmania'', create a highly modified vacuole

A vacuole () is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in plant and fungal cells and some protist, animal, and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water containing inorganic and organic mo ...

inside the phagocyte, which helps them persist and replicate. Some bacteria are capable of living inside of the phagolysosome. ''Staphylococcus aureus'', for example, produces the enzymes catalase and superoxide dismutase, which break down chemicals—such as hydrogen peroxide—produced by phagocytes to kill bacteria. Bacteria may escape from the phagosome before the formation of the phagolysosome: ''Listeria monocytogenes

''Listeria monocytogenes'' is the species of pathogenic bacteria that causes the infection listeriosis. It is a facultative anaerobic bacterium, capable of surviving in the presence or absence of oxygen. It can grow and reproduce inside the host' ...

'' can make a hole in the phagosome wall using enzymes called listeriolysin O

Listeriolysin O (LLO) is a hemolysin produced by the bacterium ''Listeria monocytogenes'', the pathogen responsible for causing listeriosis. The toxin may be considered a virulence factor, since it is crucial for the virulence of ''L. monocytogenes ...

and phospholipase C

Phospholipase C (PLC) is a class of membrane-associated enzymes that cleave phospholipids just before the phosphate group (see figure). It is most commonly taken to be synonymous with the human forms of this enzyme, which play an important role ...

.

Killing

Bacteria have developed several ways of killing phagocytes. These includecytolysin

Cytolysin refers to the substance secreted by microorganisms, plants or animals that is specifically toxic to individual cells, in many cases causing their dissolution through lysis. Cytolysins that have a specific action for certain cells are n ...

s, which form pores in the phagocyte's cell membranes, streptolysins and leukocidin

A leukocidin is a type of cytotoxin created by some types of bacteria (''Staphylococcus''). It is a type of pore-forming toxin. The model for pore formation is step-wise. First, the cytotoxin’s “S” subunit recognizes specific protein-containi ...

s, which cause neutrophils' granules to rupture and release toxic substances, and exotoxins